Abstract

Epoxy resin is widely used in metal surface protection, because of corrosion resistance and adhesion. However, it’s water solubility, oxygen, and water impermeability are not enough. In this paper, linoleic acid (LOFA) and epoxy resin (E20) were used to synthesize epoxy ester (EL) and grafted with phosphonate esterified acrylic resin (AR-P) to prepare acrylic grafted epoxy ester (EL@AR-P). After modification, water solubility and film-forming property were improved, and the oxygen transmission rate (OTR) and water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) decreased. At the addition of PM-2 at 2%, the OTR, WVTR, and water-uptake rate decreased by 12.9%, 25.0%, and 12.1%, respectively. Subsequently, the modified material was subjected to electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. The low-frequency impedance of EL@AR-P2 is three times higher than EL@AR-P0. After 16 days of immersion, the low-frequency impedance of EL@AR-P2 is 20 times higher than EL@AR-P. Energy dispersive spectrometer and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy results showed that the P elements were concentrated on the substrate surface and found the presence of P–O–Fe bonds, demonstrating that the phosphonate groups were migrated to the substrate surface to form a chelate layer with the substrate and enhancing the coating adhesion and corrosion resistance. This paper modifies the molecular structure of epoxy resin, which is expected to be an excellent material for anti-corrosion coatings.

1 Introduction

The risks of metal corrosion are well known. Metal corrosion causes not only economic losses but also safety hazards and environmental pollution. Corrosion can negatively impact the life cycle, reliability of vehicles, and steel-based facilities. Metal corrosion can also lead to the accumulation of heavy metals in soil and water, thus posing a potential threat to human and animal health (1,2,3). The organic coating is considered one of the most effective ways to protect metals; it forms a dense film on the metal surface to prevent the penetration of corrosives (4,5,6). Epoxy resins have excellent bonding properties, corrosion resistance, and thermal and chemical stabilities, which are widely used in the coatings industry (7). However, the poor flexibility of cured epoxy resins and their susceptibility to brittle cracking and the environmental pollution problem is increasingly serious, which limits their use in coatings to some extent (8). Environmental concerns have prompted researchers to use environmentally friendly raw materials to produce materials that are not harmful to the environment (9,10). Under environmental demands, vegetable oils such as flaxseed oil, soybean oil, tung oil, and rubber seed oil are used to prepare epoxy resins (11). Vegetable oils and their derivatives can improve the coatings’ properties to reduce or eliminate the use of volatile organic solvents in coatings because they have low VOC, low solvent, high solid phase, and color retention. This approach offers an opportunity to reduce reliance on organic solvents and provides green solutions to the coatings industry. Due to the hydrophobic nature of the vegetable oil chain, the development of waterborne materials from vegetable oil is the most challenging task (12,13,14). Shah and Ahmad (15) presented a method for the preparation of waterborne epoxy resins from linseed oil. Waterborne vegetable oil epoxy (WBOE) was reacted with phthalic anhydride (PA), and its reaction product (WBOE-PA) was finally prepared from waterborne phenolic (PF) cured to obtain a water-based coating (WBOE-PA-PF). In synthetic or coating formulations, no toxic volatile organic solvents are used. The coatings have good scratches hardness, impact resistance, flexibility, and thermal stability. However, good water compatibility of the coating material is not achieved, which may be due to the hydrophobicity of the vegetable oil chain segments. Cao et al. (16) adopted waterborne epoxy to modify tung oil waterborne insulation varnish. Based on the D–A addition reaction of tung oil and maleic anhydride and the ring-opening esterification reaction of epoxy resin, the development of new epoxy-modified tung oil waterborne insulating varnish. The increase in epoxy resin content not only improved the thermal stability and insulation properties of the membrane but also decreased the water absorption of the membrane. Unfortunately, the study did not report the oxygen transmission rate (OTR) and water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) of the varnish, and the specific corrosion protection properties of the varnish.

To improve the water solubility of epoxy resin and enhance its film-forming properties, acrylate resin, rubber, polyurethane, or other thermoplastics have been used to modify epoxy resin to satisfy the application requirements of coating materials (17,18,19,20). Acrylic resin is an important film-forming material with excellent adhesive properties, film-forming properties, and it is widely used as a surface coating for walls, wood, and metals (21,22). Several methods have been used to prepare epoxy resin and polyacrylic acid (EP/PA) composites. Woo and Toman (23) synthesized waterborne epoxy-acrylic acid composite copolymers by adding hydrophilic groups to the epoxy resin of molecular chains to make them water-dispersible, but they still use organic solvents in the reaction process. Pan et al. (24) synthesized epoxy-acrylic acid composite emulsions using an emulsion polymerization method with monomer-emulsified epoxy resins. No organic solvent was used in the synthesis process. However, the epoxy chains were only mixed with polyacrylate in latex particles, which was not conducive to the compatibility of the two polymers. Tang et al. (25) designed a method to prepare epoxy-grafted polyacrylate composite emulsions with a high grafting ratio. The emulsions prepared by this method improved the adhesion and corrosion resistance of the coatings. Yao et al. (26) prepared a polyacrylic acid/epoxy composite emulsion with high polyacrylic acid content using a fine emulsion copolymerization method. The water resistance of the coatings was not described by Tang and Yao. To further improve the water resistance of the composites, better results can be obtained with minimal or without the use of surfactants.

In this work, the epoxy ester was modified with epoxy resin E20 and linoleic acid to improve the retention and fast drying rate of the epoxy ester. Then, hydroxypropyl acrylate (HPA) was used to etheric graft the epoxy ester. Acrylic monomers were added for graft copolymerization to obtain the modified material (EL@AR-P). The introduction of the phosphonate group improves the film formation and adhesion of EL@AR-P and thus the coating’s impermeability, while the chelation of the phosphonate group improves corrosion resistance. WVTR, OTR, and water resistance are used to characterize the coating’s impermeability. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and neutral salt spray (NSS) testing are performed to evaluate the corrosion resistance of coatings. Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were investigated to verify the migration of phosphonate groups. This paper aims to develop an anti-corrosion coating and reveals the mechanism of phosphonate in the coating.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Epoxy resin (E20) was obtained from Jining Huakai Resin Co., Ltd (Jining, China). Linoleic acid (LOFA) was purchased from Anhui Rifende Oil Deep Processing Co., Ltd (Langxi, China). HPA, methyl methacrylate (MMA), methacrylic acid (MAA), butyl acrylate (BA), and styrene (St) were purchased from Tianjin Hedong Hongyan Reagent Plant (Tianjin, China). The above monomers are chemically pure. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate phosphonate (PM-2) was supplied by Guangzhou Weber Technology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). dibenzoyl peroxide (BPO), tert-butyl peroxybenzoate (TBPO), and tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB) were purchased from Kingchemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Antifoaming agent (TEGO 810) and dispersing agent (TEGO 760 W) were purchased from Evonik Specialty Chemicals (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

2.2 Synthesis of waterborne phosphorylated acrylic resin (AR-P) composite modified epoxy esters (EL) composite emulsion (EL@AR-P)

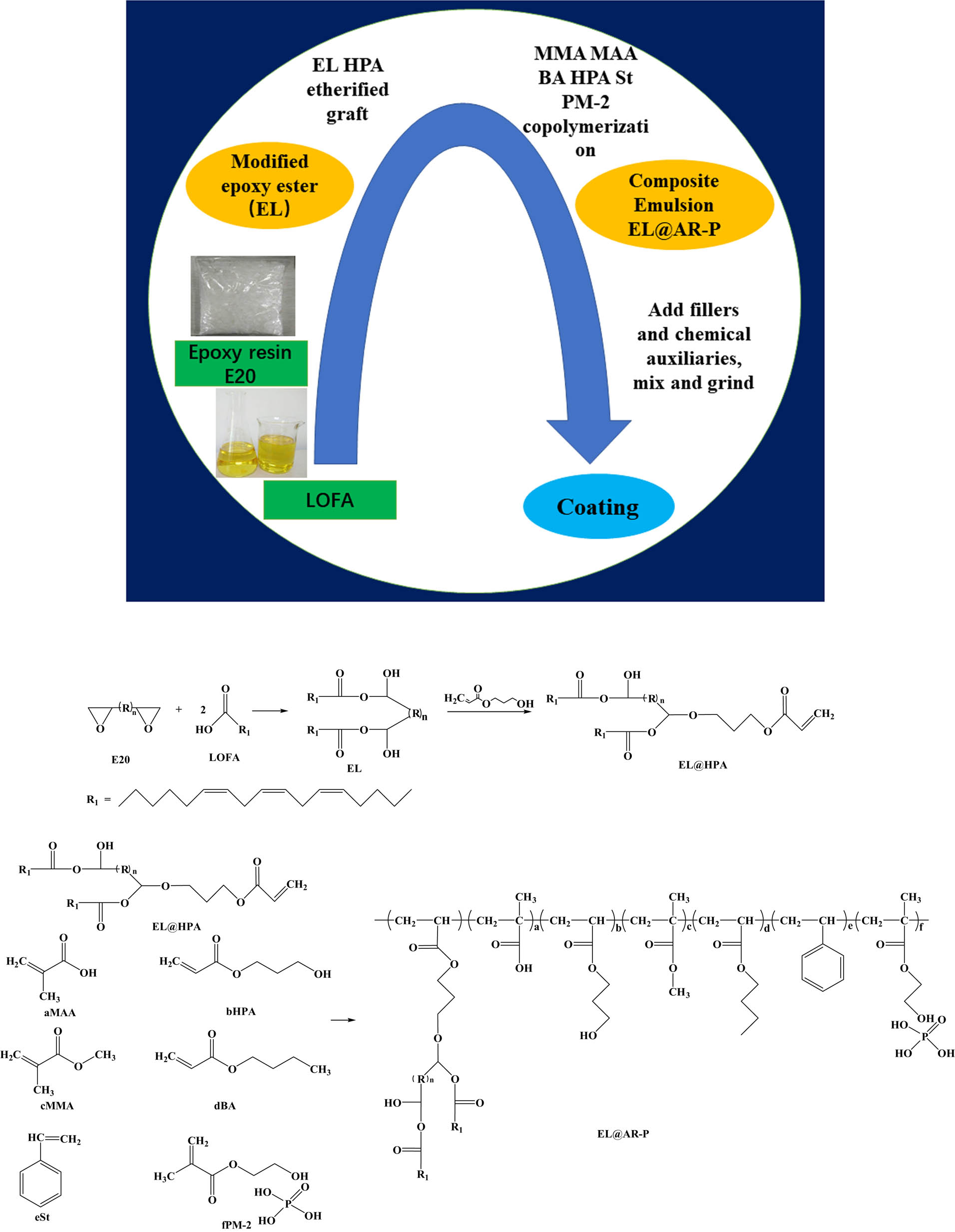

The EL was prepared by using E20 and LOFA. E20 (0.1 mol) was taken in a three-necked round bottom flask, TBAB was added as an initiator, and LOFA (0.2 mol) was added into the reaction flask with continuous stirring at 130°C for 4 h. Then, EL and HPA (0.1 mol) etherified graft (EL@ HPA) at 90°C, followed by the addition of MMA, HPA, MAA, BA, St, and PM-2 for graft copolymerization, and BPO was added as an initiator; the reaction time was 3 h at 80°C, and then the temperature was raised to 110°C, TBPO was added, and the reaction was stirred for 2 h. The modified materials (EL@AR-P) were neutralized to 0.8 in DMEA and emulsified with deionized water to produce an emulsion with a solid content of 40% for the preparation of latex films and coatings. The use of PM-2was changed to 0, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% of the total mass of the monomer while keeping the other conditions constant, and the prepared modified emulsions were labeled as EL@AR-P0, EL@AR-P1, EL@AR-P2, EL@AR-P3, and EL@AR-P4. The reaction process and reaction mechanism are shown in Figure 1.

The reaction process and reaction equation.

2.3 Preparation of latex film

The latex film was prepared as follows: 20 g of the composite emulsion was accurately weighed and poured into the PTFE template, left to stand for 7 days at room temperature, then allowed to dry naturally, and finally put into a vacuum drying oven at 60°C for 2 h, and the film was placed in a drier for characterization.

2.4 Fabrication of composite coatings

The general procedure for the preparation of composite coatings is as follows. The EL@AR-P emulsion was poured into a beaker and DI-water was added, dispersant, pigment filler (BaSO4, carbon black), defoamer, stirred with dispersing machine, and then the composite emulsion was mixed evenly, and finally coated on tinplate according to the existing Chinese std (GB/T 1727-1992) (27).

2.5 Characterization

The structural properties of EL, EL@AR, and EL@AR-P were characterized through Fourier-transform infrared spectra (FT-IR, VECTOR-22, Bruker) between 500 and 4,000 cm−1. The stability of the emulsion was tested by Stability Analyzer (Turbiscan Lab). The particle size of the composite emulsion was measured by laser particle scattering (Panalytical, Malvern). The test temperature was 25°C, the laser angle is 90°, and the test laser wavelength was 633 nm. The stability of the emulsion was measured by a stability tester, and the samples were tested using near-infrared light (λ = 880 nm) for 2 h.

WVTR measures of coatings were carried out through a water vapor permeability tester (WVTR-W6, Pubtester). All WVTR measures were performed at 25°C and 90% RH. The OTR of the coatings was obtained via an OTR tester (OTR-O1, Pubtester). All OTR tests were conducted at 25°C and 50% RH in 1 atm oxygen partial pressure condition. Atomic force microscopy (AFM, SPA-400, SEIKO) was applied to investigate the morphology of the coatings.

Electrochemical tests were conducted in a PARSTAT MC (Princeton) electrochemical workstation with a three-electrode system. A platinum foil was used as a counter electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode was set as a reference electrode, and all test samples were used as working electrodes with an exposed area of 1 cm−2 and the electrolyte was 3.5% NaCl solution. EIS measurement was conducted at a set frequency from 1,00,000 to 0.01 Hz, and the sinusoidal voltage signal amplitude was 10 mV. EIS results were fitted with ZsimpWin software to record corresponding corrosion parameters. Polarization curves were performed under the set potential range from −1.000 to +2.000 V with a scan rate of 0.01 V/s (28,29,30,31).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Spectral analysis of acrylate-epoxy emulsion

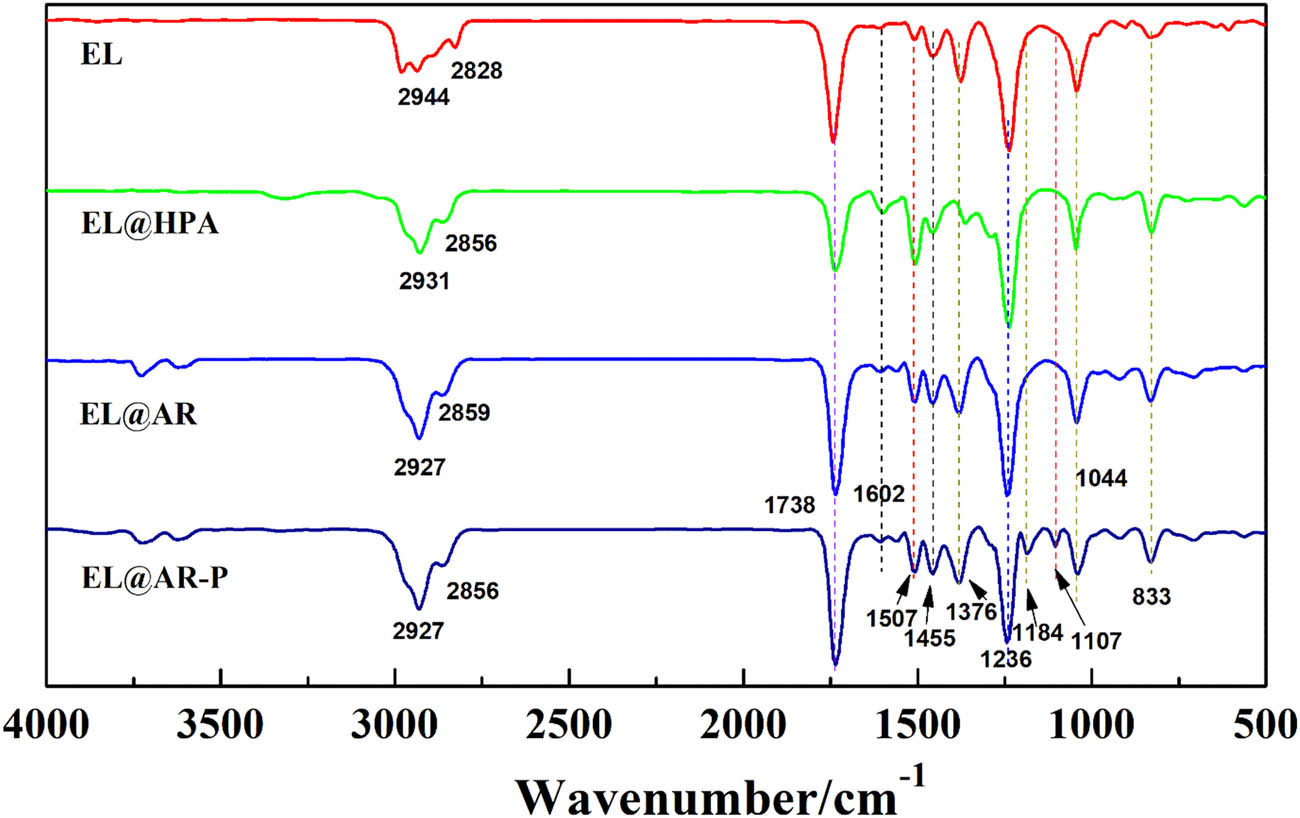

To investigate the chemical structure of the composite emulsion, we made a latex film of the composite emulsion and analyzed its structure using FTIR Spectrometer. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Infrared spectrum of EL, EL@HPA, EL@AR, EL@AR-P latex film.

From Figure 2, the stretching vibration peaks of the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in EL@AR-P are at 3,720 and 3,618 cm−1, respectively; the tensile vibration peaks of –CH3 and –CH2 are at 2,927 and 2,856 cm−1, respectively; and the tensile vibration peak of the carbonyl group (C═O) is at 1,738 cm−1. The skeleton vibration peaks of the benzene ring are at 1,507 and 1,455 cm−1, respectively, the bending vibration peak of –CH3 is at 1,376 cm−1, and the tensile vibration peak of the aromatic ether is at 1,236 cm−1. The characteristic absorption peaks P═O and C–O–P appear at 1,184 and 1,107 cm−1, respectively, and the unsaturated double bond peak is at 1,602 cm−1. Comparing the EL and EL@HPA IR spectra of Figure 2, EL@HPA has an unsaturated double-bonded peak of HPA at 1,602 cm−1. Comparing the EL@HPA and EL@HPA IR spectra of Figure 2, peaks of EL@AR at 3,720 and 3,618 cm−1 are the stretching vibration peaks for the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, respectively, and a weakly unsaturated double-bonded peak of LOFA at 1,602 cm−1. Demonstration of completed polymerization of acrylic monomers. Comparing the EL@AR and EL@AR-P spectra, EL@AR-P shows the characteristic absorption peaks P═O and C–O–P at 1,184 and 1,107 cm−1, respectively. This is a demonstration of the complete polymerization of phosphonate ester groups in acrylic resin.

3.2 Particle size and stability analysis

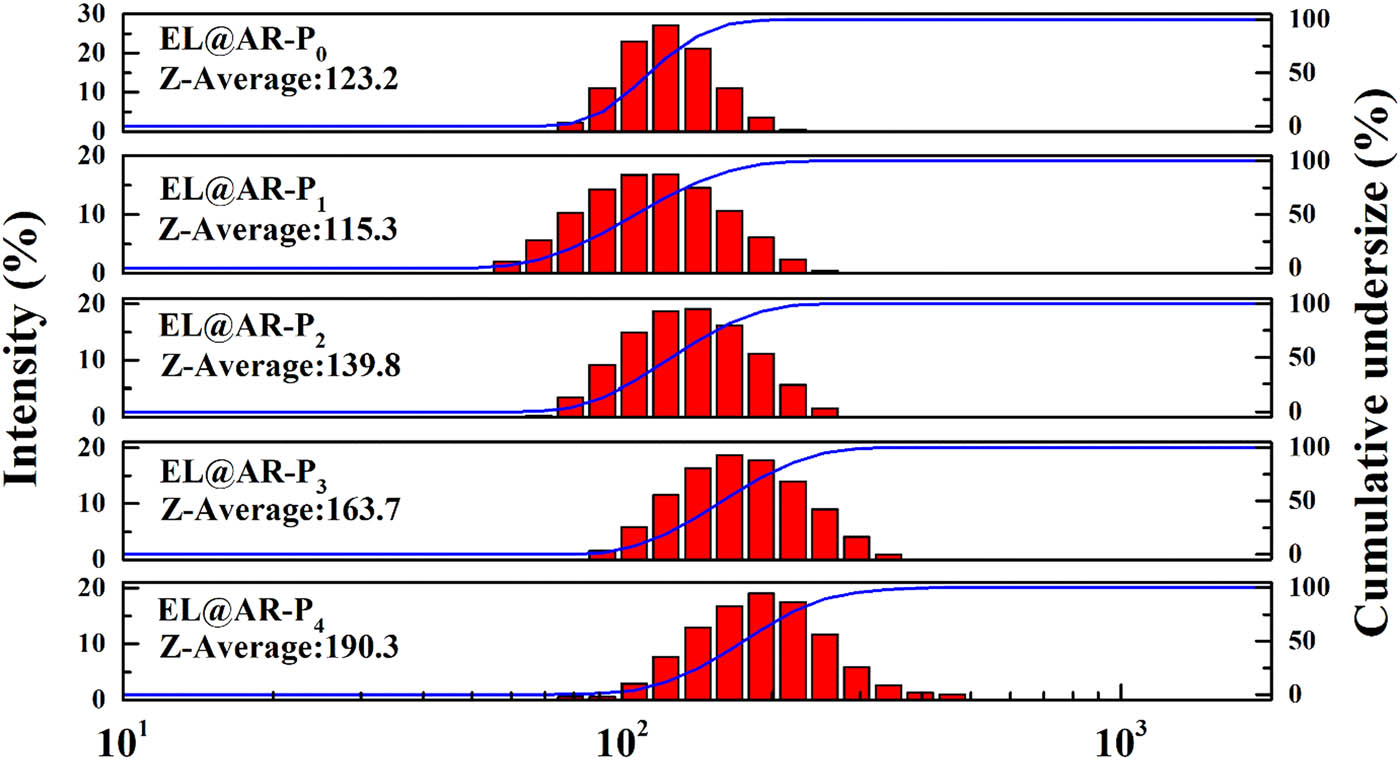

Figure 3 shows the particle size distribution of EL@AR-P emulsion, and Figure 4 shows the stability curve of EL@AR-P emulsion. As can be seen from Figure 3, with an increase in the use of PM-2, the average particle size of EL@AR-P0, EL@AR-P1, EL@AR-P2, EL@AR-P3, and EL@AR-P4 emulsions is 123.2, 115.3, 139.8, 163.7, and 190.3 nm, respectively, and the particle size distribution of the composite emulsions becomes wider and the particle size increases from 115.3 to 190.3 nm. When the PM-2 content reached 3%, the average particle size of the emulsion increased significantly, which was caused by the high phosphonate activity and the high-density crosslinking between the polymer chain segments. In the process of film formation, the smaller the particle size of the pellet, larger the capillary force and total surface area of the film, which is conducive to the interpenetration of polymer chain segments to promote film formation and improve the density of the film to prevent the penetration of water and small molecules and thus improve anti-corrosion properties (32).

Particle size distribution of EL@AR-P emulsions.

Stability of EL@AR-P emulsions.

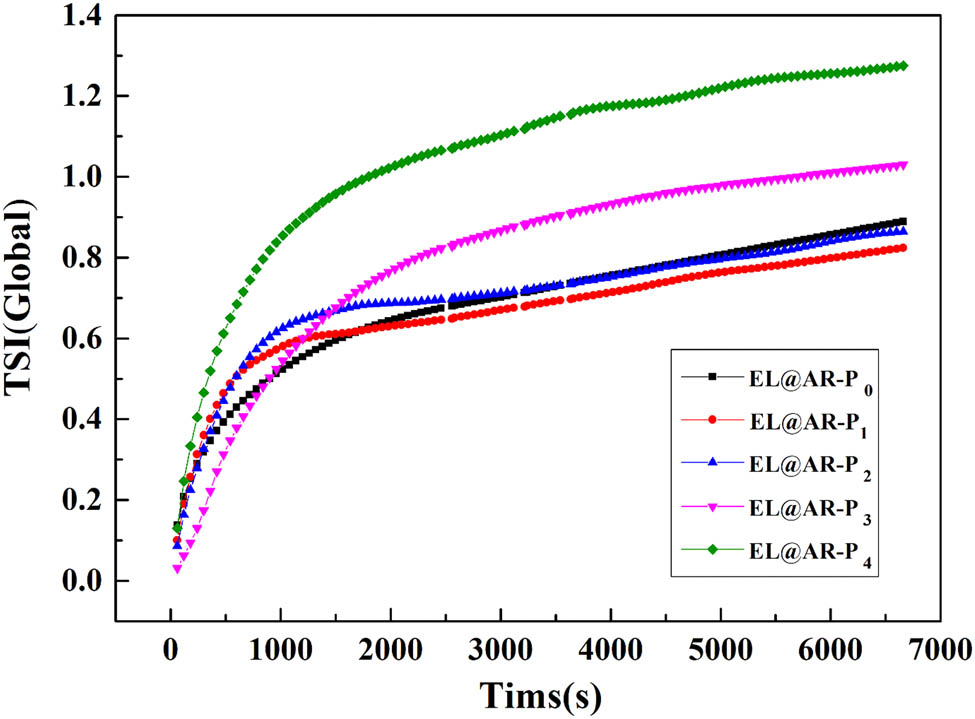

The emulsion dispersion stability index TSI curves can be used to characterize the effect of aging time on emulsion stability. The higher the number of TSI index in a certain time, the lower the emulsion stability (33). Figure 4 shows that as the test time increases, the TSI curves of all samples shown a tendency to sharp increase at first and then flatten out, indicating that the emulsion tends to stabilize after a certain aging time. During the 120 min test, the TSI index of the emulsion was EL@AR-P0 < EL@AR-P1 < EL@AR-P2 < EL@AR-P3 < EL@AR-P4; with increasing PM-2 content, there is a slight decrease in instability in emulsions. The TSI indices were all less than 1. EL@AR-P3 and EL@AR-P4 emulsions showed a significant increase over EL@AR-P0, EL@AR-P1, and EL@AR-P2 emulsions, which are consistent with the particle size test.

3.3 Effect of PM-2 content on the impermeability of EL@AR-P coatings

The impermeability of the coating plays an important role in its excellent corrosion resistance. Generally, higher resistance to permeation leads to better corrosion resistance of the metal (34,35). WVTR, OTR, and water-uptake rate are critical for anticorrosive coatings.

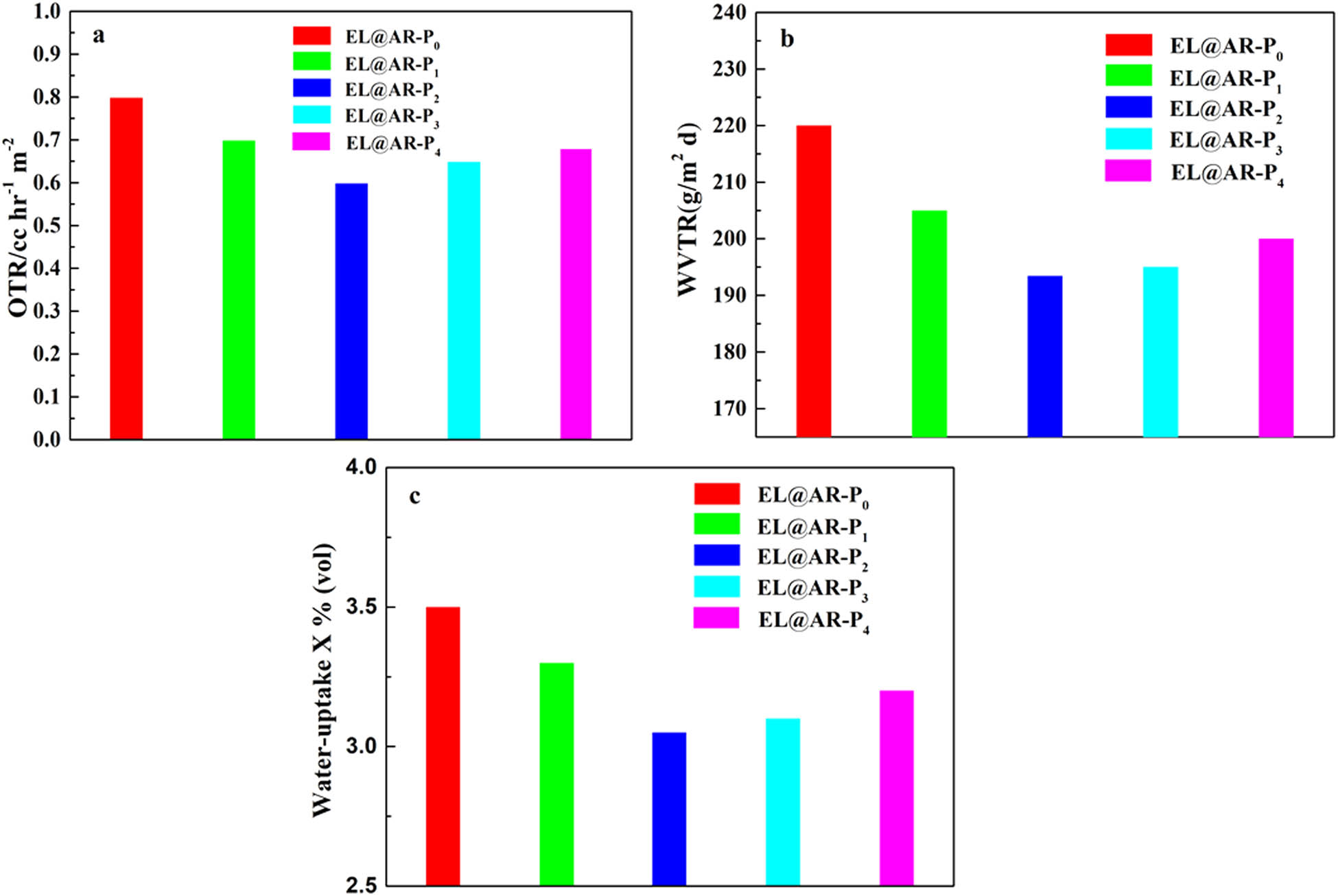

The water vapor, oxygen permeability, and water-uptake rates of EL@AR-P coatings with different PM-2 contents were shown in Figure 5. With an increase in the PM-2 content, the WVTR, OTR, and water-uptake rate of EL@AR-P2 coating showed a tendency to decrease at first and then increased. For EL@AR-P0 coating to EL@AR-P2 coating, the gradual increase in the denseness of the coating reduced the water and oxygen permeability, improved the coating’s resistance to penetration. With an increase in the PM-2 content, EL@AR-P3 coating and EL@AR-P4 coating resulted in excessive coating cross-linking, local defects of the curve, and the increase in water vapor, oxygen permeability, and water-uptake.

Oxygen (a) and water vapor (b) transmission rates of the EL@AR-P coatings, water-uptake rate of the EL@AR-P coatings (c).

3.4 EIS analysis

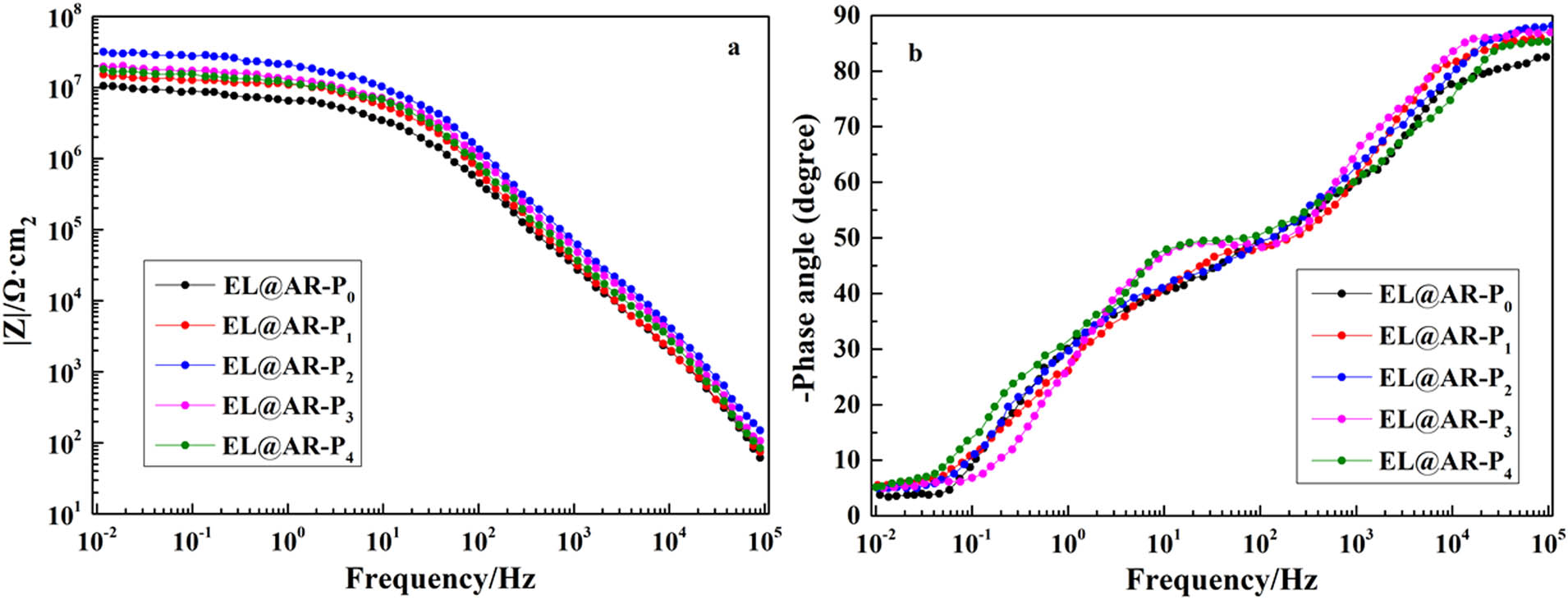

Figure 6a shows the Bode plot of EL@AR-P0, EL@AR-P1, EL@AR-P2, EL@AR-P3, and EL@AR-P4 coatings in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. The Bode plots derived from the EIS measurements with frequency ranging from 105 to 10−2 Hz were used to investigate the role of composite coatings on the protection for the tinplate (31,36). Usually, the peak appearing in the high-frequency region (105–103 Hz) of the Bode plot could be applied as an indicator of coatings responses, and the peak located at medium (103–102 Hz) and low frequency (102–10−2 Hz) corresponds to the responses of corrosion, reflecting the coating failure (37,38). Besides, the impedance module at low frequencies (|Z|0.01 Hz) is usually applied as a semiquantitative indicator of the protective properties for coatings (39). With the increasing usage of PM-2, there is an increasing trend of |Z|0.01 Hz (Figure 6a), indicating the enhanced effect of PM-2 on corrosion prevention. When the amount of PM-2 is 2%, |Z|0.01 Hz of EL@AR-P2 coating (3.17 × 107 Ω cm2) is EL@AR-P0 coating 3 times (1.05 × 107 Ω cm2) (Figure 6a), means the corrosion resistance strongly improved. Bode phase (Figure 6b) shows the phase angle (PA) changes for EL@AR-P samples immersed in 3.5 wt% NaCl (aq) as a function of frequency. Generally, an ideal PA value for a polymer coating is close to −90°, which indicates that the coating belongs to a pure nonconductive capacitor (31,40). This means that a PA value approaching −90° reveals the highly capacitive behavior of the coating. As can be observed from Figure 6b that the EL@AR-P0 coating (−82.56°) showed the lowest PA, the EL@AR-P2 coating (−88.53°) exhibited the highest capacitive response as well as the best corrosion resistance, while the other EL@AR-P coating samples displayed an intermediate PA.

Bode modulus plots (a), Bode phase plots (b).

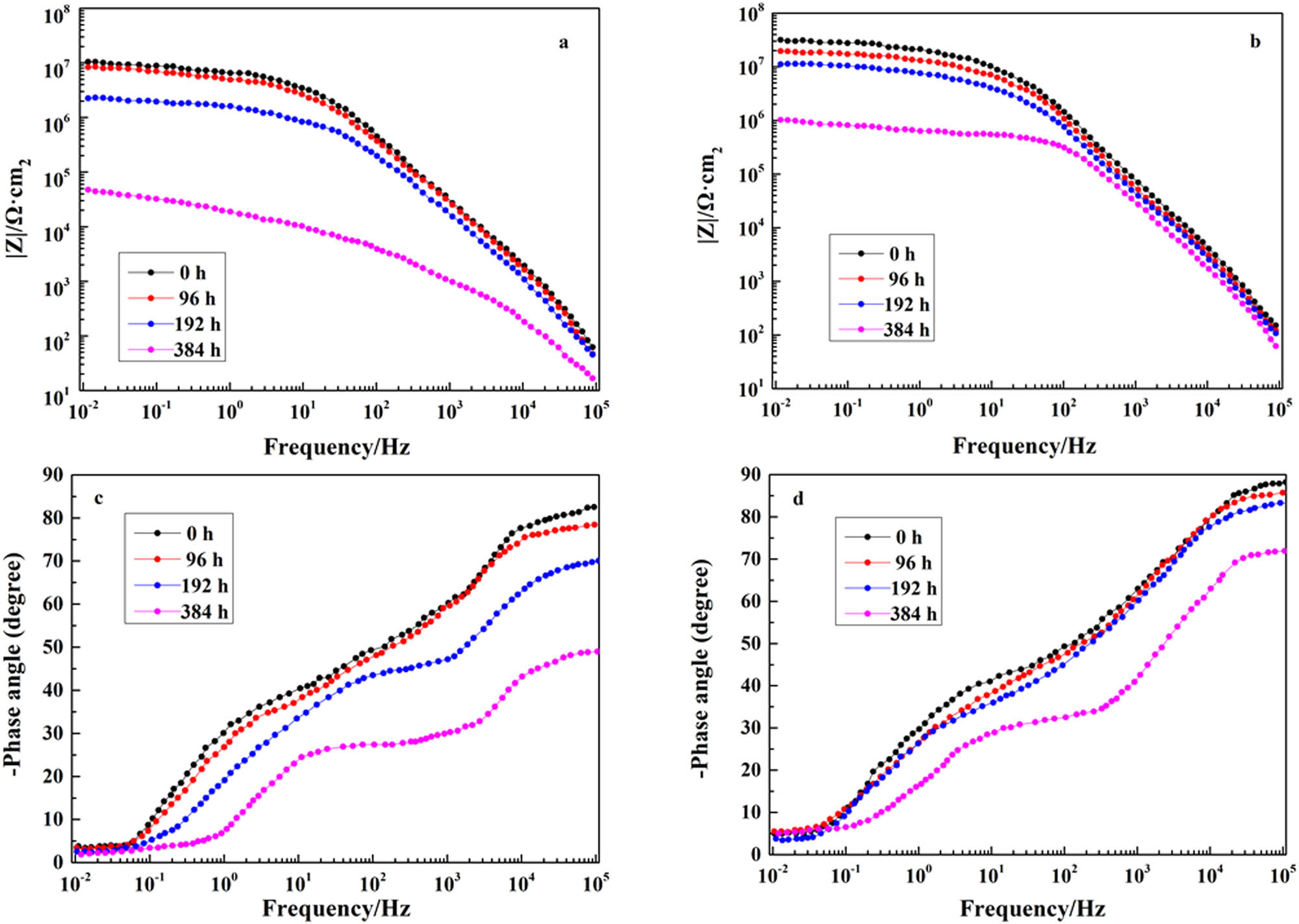

After the previous EIS test, EL@AR-P0 coating and EL@AR-P2 coating were selected to test the changes in EIS from immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl (aq). Figure 7 presents the Bode plots and the phase angle change of EL@AR-P0 coating and EL@AR-P2 coating at different exposure times in 3.5 wt% NaCl (aq). |Z|0.01 Hz for EL@AR-P0 decreases from 1.05 × 107 to 4.77 × 104 Ω cm2 (Figure 7a) and EL@AR-P2 (|Z|0.01 Hz) decreases from 3.17 × 107 to 1.02 × 106 Ω cm2 (Figure 7b) after 16 days of immersion, respectively. Figure 7a and b plots show that EL@AR-P2 coating decreased much more slowly than EL@AR-P0 coating with the extension of time. Especially after 8 days of immersing in 3.5 wt% NaCl (aq), EL@AR-P2 coating did not appear a second time constant until 16 days of immersion (Figure 7d), whereas EL@AR-P0 coating began to appear a second time constant as early as 8 days of immersion (Figure 7c). The results showed that the addition of PM-2 effectively improved the impermeability and corrosion resistance of the coating.

Bode modulus plots (a), Bode phase plots (c) of EL@AR-P0, Bode modulus plots (b), Bode phase plots (d) of EL@AR-P2.

3.5 Polarization curve (Tafel) analysis

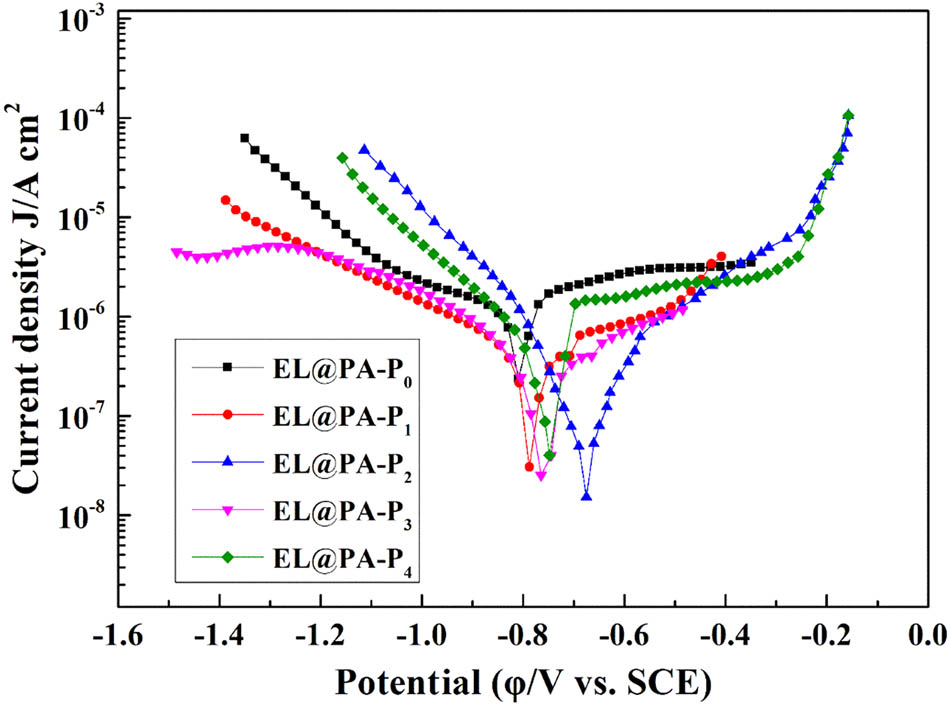

The potentiodynamic polarization plots of the tinplate coated with composite coatings in 3.5 wt% NaCl (aq) as a function of immersion time are shown in Figure 8. The corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (icorr) were fitted by electrochemical software. The inhibition efficiency (IE) was calculated through Eq. 1 (41):

where itin and icorr stand for the corrosion current density of bare tinplate and coated tinplate, respectively. The fitting electrochemical parameters are recorded in Table 1. icorr of EL@AR-P0 coating (2.34 × 10−7 A cm−2) is less than bare tinplate (9.86 × 10−6 A cm−2). The icorr further decreased from 2.34 × 10−7 to 1.51 × 10−8 A cm−2 as PM-2 increased from 0% to 2%. icorr increased to 4.02 × 10−8 A cm−2 when PM-2 is over 3%. The significant reduction in icorr demonstrated more effective corrosion protection and better resistance toward diffusive ions (41,42). Besides, the current densities of EL@AR-P2 coating are lower than the EL@AR-P0 coating, indicating the efficient suppression effect of EL@AR-P2 coating (43). Further, Ecorr of EL@AR-P coatings shift to the positive direction, and the EL@AR-P2 coating displays the most positive value (−0.512 V), suggesting better anticorrosive property than other samples, which are consistent with EIS results.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves.

Electrochemical test results of coatings with different PM-2 usages

| Sample | EL@AR-P0 | EL@AR-P1 | EL@AR-P2 | EL@AR-P3 | EL@AR-P4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecorr (V) | −0.801 | −0.786 | −0.675 | −0.763 | −0.750 |

| icorr (A cm2) | 2.34 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−8 | 1.51 × 10−8 | 2.60 × 10−8 | 4.02 × 10−8 |

| IE% | 97.63 | 99.68 | 99.85 | 99.74 | 99.59 |

3.6 Morphological analysis of corrosion area

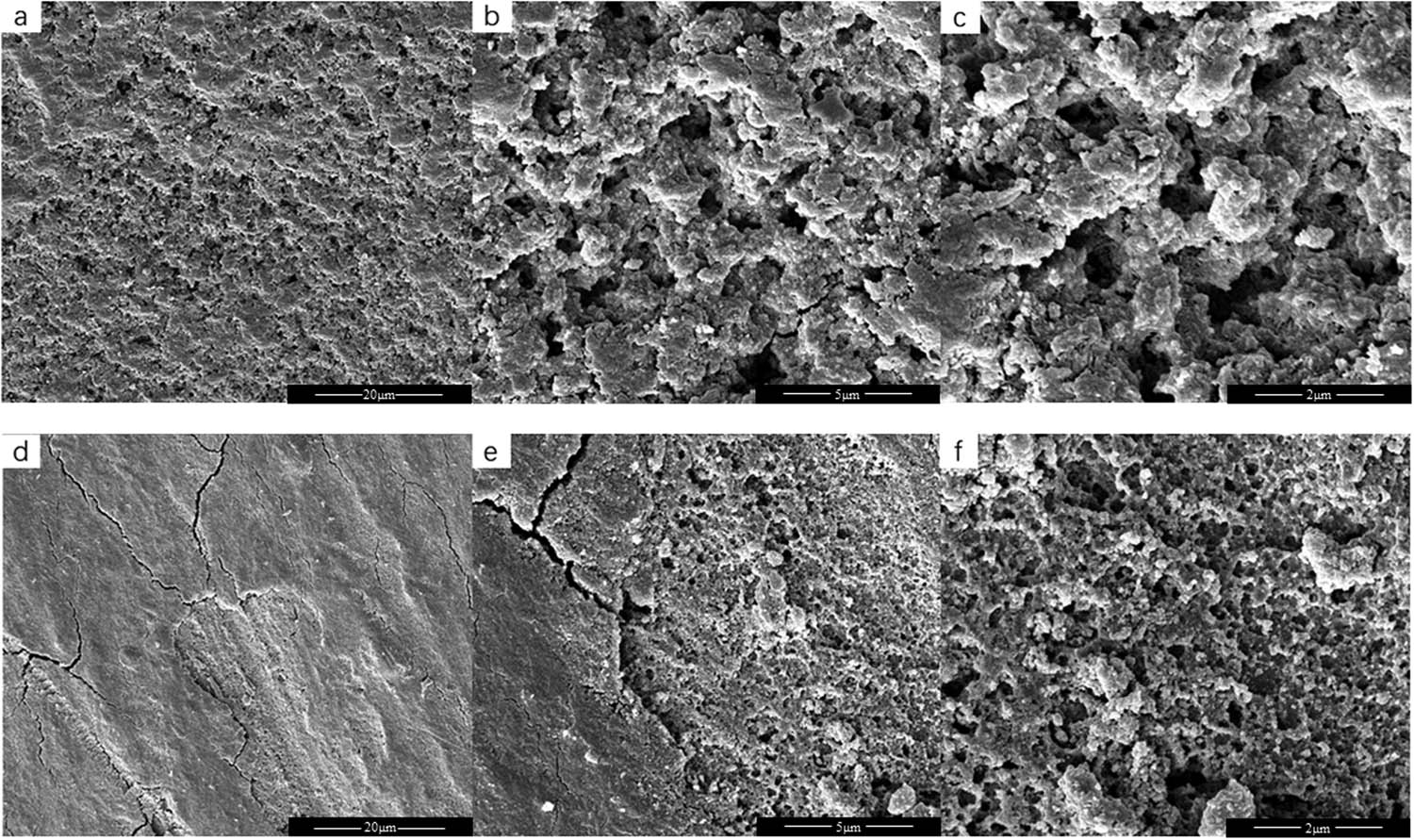

After the electrochemical measurements, EL@AR-P0 coating and EL@AR-P2 coating were peeled off from the tinplate surfaces. SEM observations for the tinplate surfaces were performed to confirm the electrochemical measurements. The surface chemical composition of the tinplate sample was also detected using EDS. The SEM morphologies of the tinplate are shown in Figure 9. The surface of the tinplate protected by the EL@AR-P0 coating suffered more serious corrosion, with a large and deep area of corrosion. While the tinplate protected by the EL@AR-P2 coating had a smoother surface, with a small and shallow area of corrosion, which indicates that the EL@AR-P2 coating has better corrosion resistance than EL@AR-P0 coating.

SEM images on coating-exfoliated steel surfaces after 16 days of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, (a–c) EL@AR-P0, (d–f) EL@AR-P2, (a and d) magnification level of 2,000×, (b and e) magnification level of 10,000×, (c and f) magnification level of 20,000×.

The EDS results are listed in Table 2. During immersion, corrosion products were mainly generated through the electrochemical reaction of tinplate with water molecules as well as oxygen in the electrolyte. The O and Fe are regarded as the two primary elements for chemical composition analysis on tinplate surfaces, whereas the C element was ignored (31). From Table 2, 53.13 wt% of the O element and 20.06 wt% of the Fe element and 44.30 wt% of the O element, and 29.95 wt% of the Fe element were detected on the tinplate surfaces coated by EL@AR-P0 coating and EL@AR-P2 coating. Therefore, it is easily concluded that the EL@AR-P2 coating possesses better corrosion resistance than EL@AR-P0 coating, which is consistent with the EIS results.

Surface chemical composition on tinplate surfaces coated by different coatings

| Element | C (%) | O (%) | Fe (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EL@AR-P0 | 21.82 | 53.12 | 20.06 |

| EL@AR-P2 | 25.75 | 44.30 | 29.95 |

3.7 NSS test results analysis

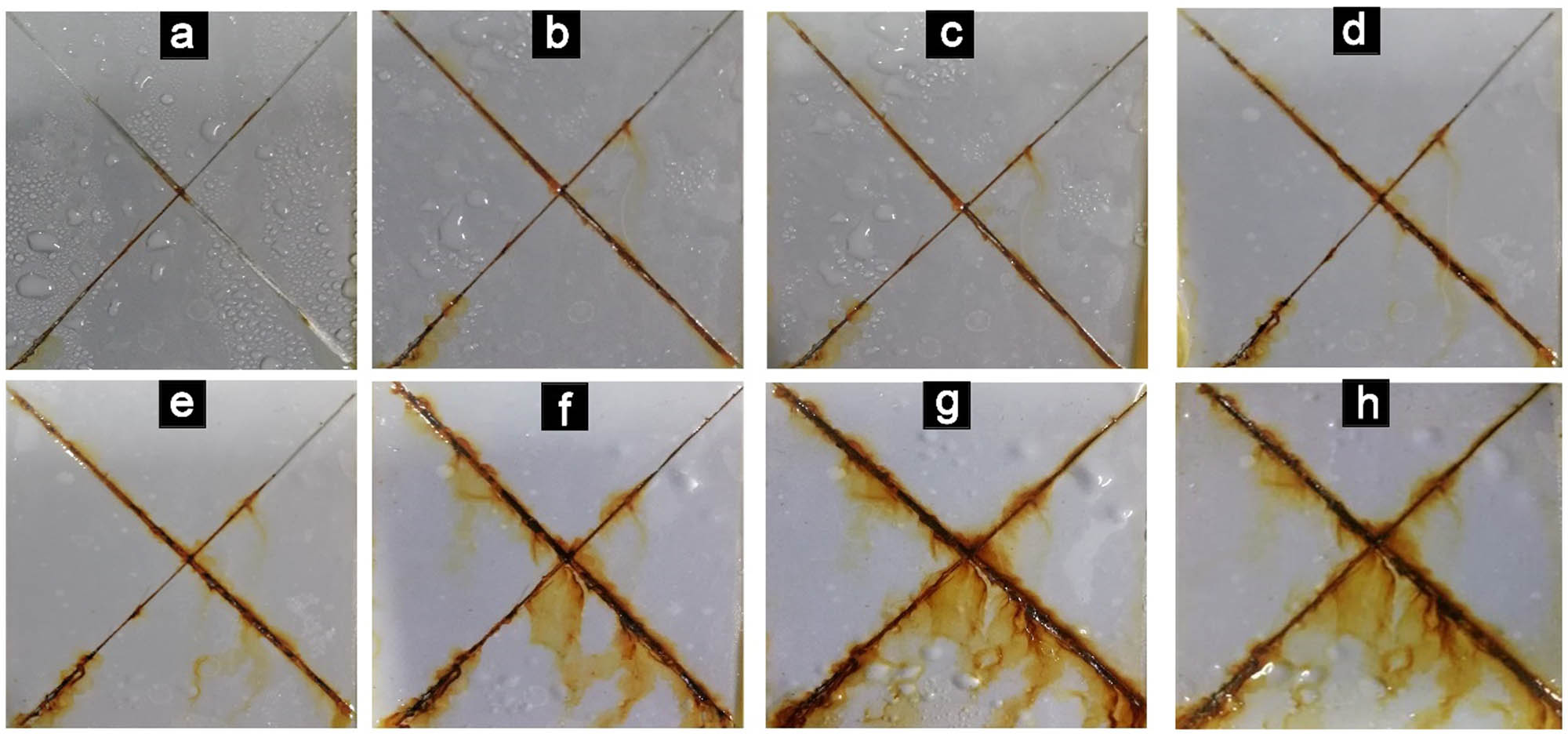

Salt spray test is the use of a salt spray tester to simulate environmental conditions to evaluate the corrosion resistance of the coating. The EL@AR-P0 coating and EL@AR-P2 coating were tested using a salt spray tester for 48, 96, 144, 192, 240, 288, 336, and 384 h NSS experiments. The results of the experiment are shown in Figures 10 and 11.

Salt spray test diagram of EL@AR-P0 film: 48 h (a), 96 h (b), 144 h (c), 192 h (d), 240 h (e), 288 h (f), 336 h (g), 384 h (h).

Salt spray test diagram of EL@AR-P2 film: 48 h (a), 96 h (b), 144 h (c), 192 h (d), 240 h (e), 288 h (f), 336 h (g), 384 h (h).

From Figures 10 and 11, EL@AR-P0 coating and EL@AR-P2 coating showed almost the same corrosion in 96 h. However, EL@AR-P2 coating showed significantly less corrosion. At 144–288 h, EL@AR-P0 coating (Figure 10c–f) corrosion area had significant spread and more corrosion products appeared. There is a small amount of bubbling at 192 h (Figure 10d). While in the same period, there is no significant expansion in the corrosion area and fewer corrosion products for EL@AR-P2 coating. And there is a small number of bubbles that appeared at 288 h (Figure 11f). At 288–384 h, the corrosion area of EL@AR-P0 coating (Figure 10g and h) continues to expand, while the corrosion area of the EL@AR-P2 coating (Figure 11g and h) did not expand significantly. Salt spray test results showed that EL@AR-P2 coating has better corrosion resistance than EL@AR-P0 coating. NSS result was consistent with EIS and SEM results.

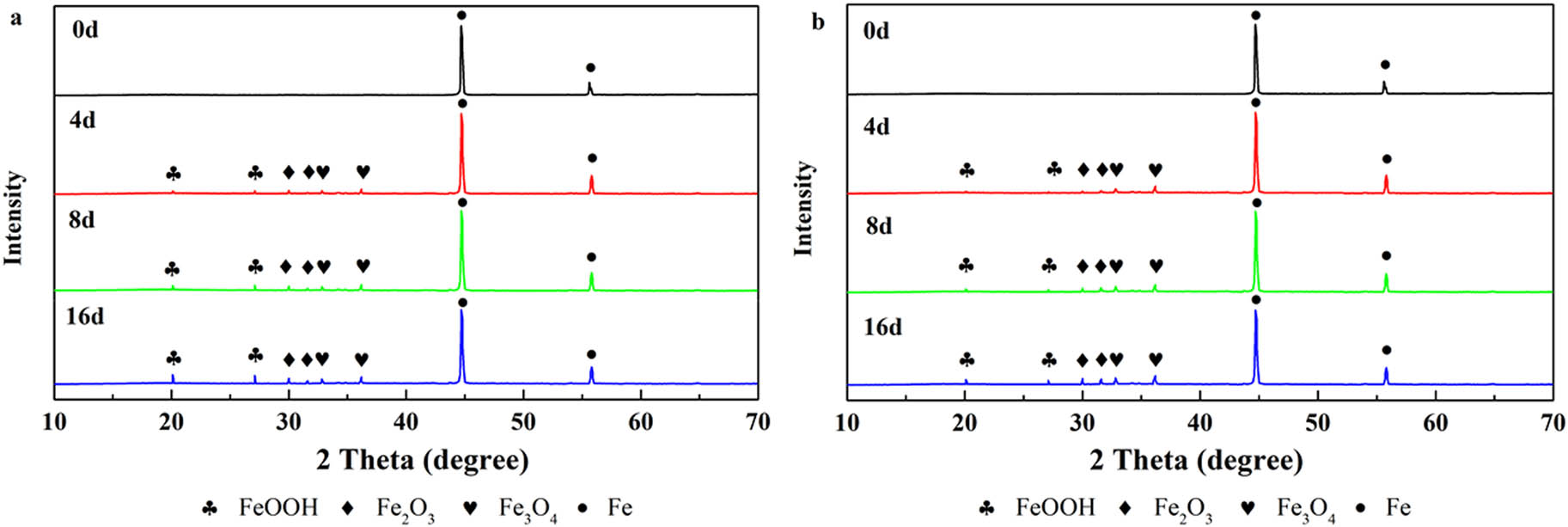

3.8 Characterization of corrosive products

For a further study of the effect of composite coatings on the tinplate beneath them, XRD was employed to evaluate the chemical composition of the tinplate surface for 16 days of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl (aq). The tinplate coated by EL@AR-P0 coating was applied as a control to contrast its corrosion condition with EL@AR-P2 coating. The EL@AR-P2 coating was selected due to its better corrosion resistance than other composite coatings and the worst protection performance among EL@AR-P0 coating according to the electrochemical results. The XRD patterns of EL@AR-P0 coating and EL@AR-P2 coating are shown in Figure 12.

XRD patterns of surface of tinplate samples coated by EL@AR-P0 (a) and EL@AR-P2 (b) during immersion time.

Permeating through the coating, corrosive electrolytes were produced by FeOOH, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4 composed of a corrosion layer (28,29,31). During immersion, the corrosion products consisted of FeOOH, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4. The corrosion products of EL@AR-P0 coating was mainly FeOOH, while those of the EL@AR-P2 coating were mainly FeOOH, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4. Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 are caused by the lack of oxygen on the surface of the tinplate. These results indicated that EL@AR-P2 formed a passive film consisting of Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 on the tinplate surface and assisted in prevent further corrosion of the substrate.

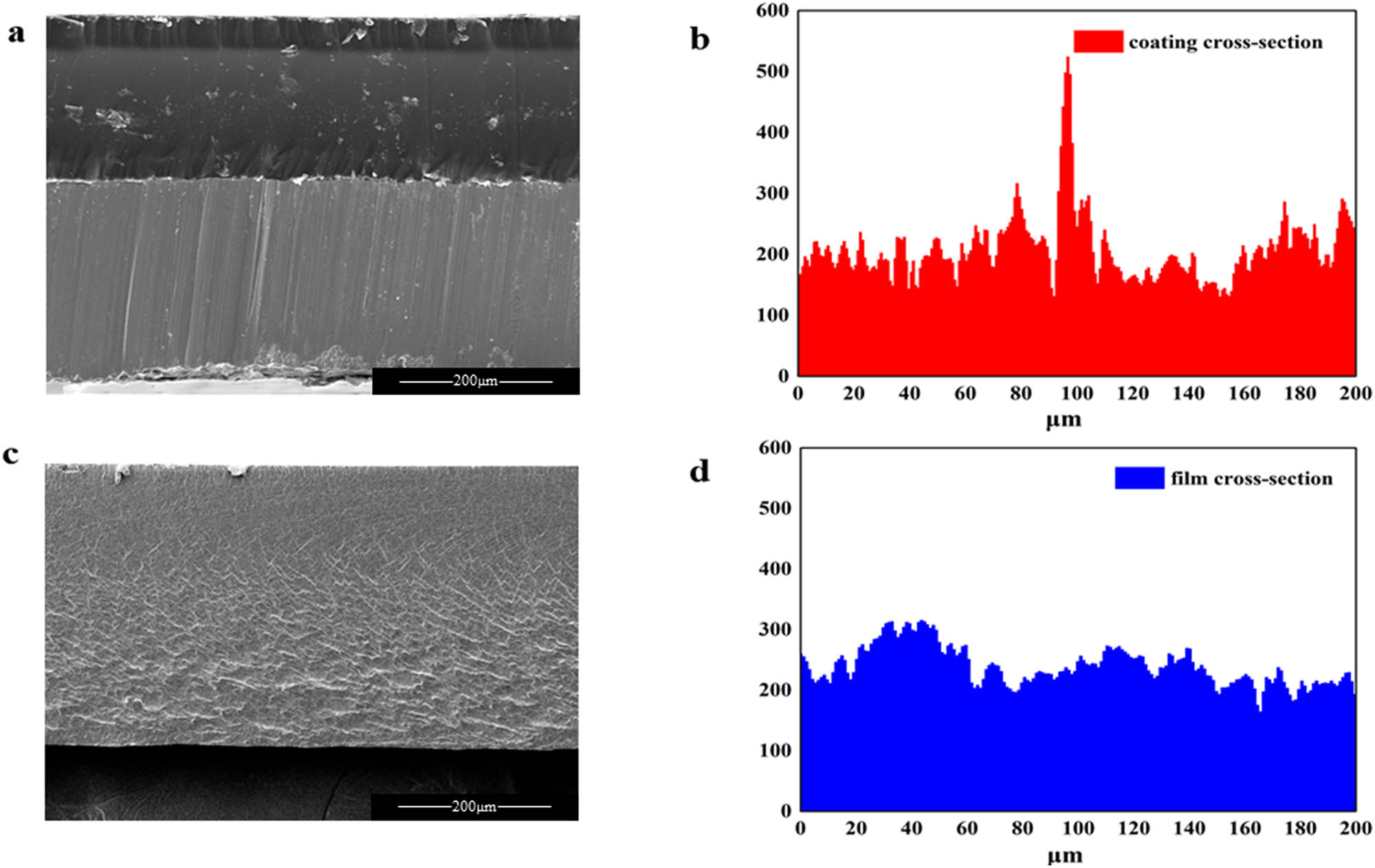

3.9 EDS and XPS analysis of cross-section

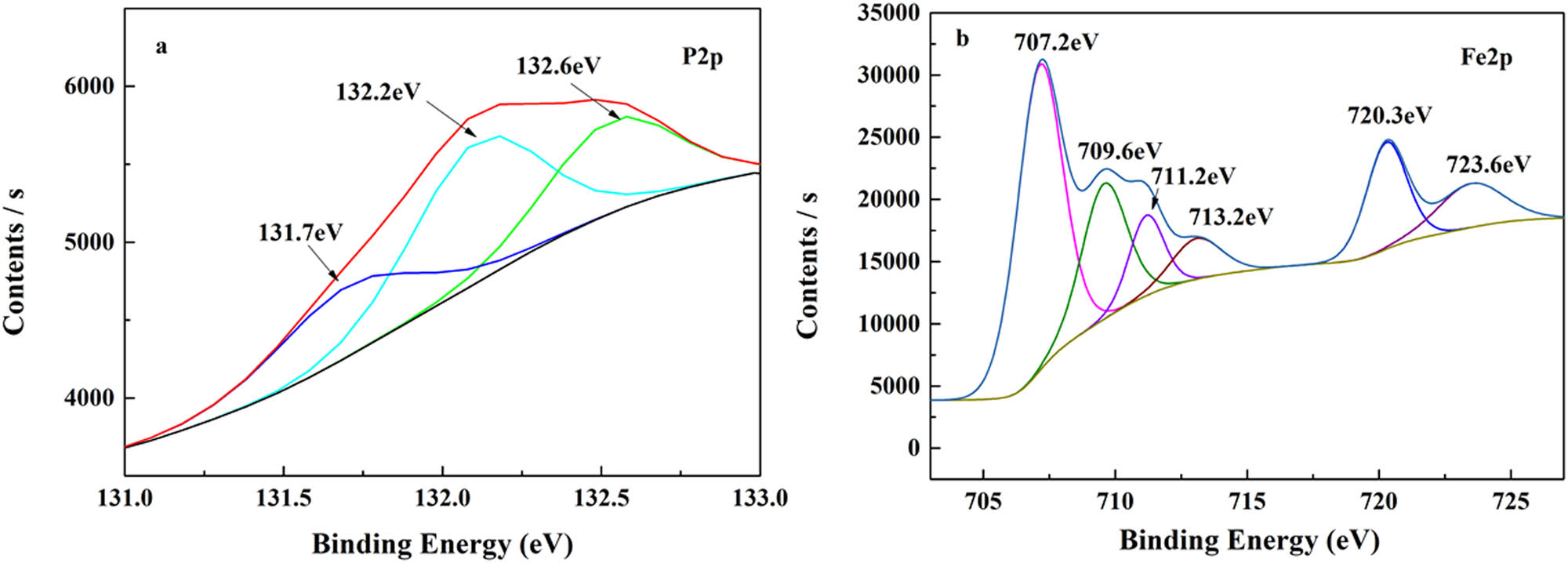

To further investigate the polar migration behavior of the phosphonate groups. The cross-section of EL@AR-P2 emulsion film formation on PTFE and the cross-section of EL@AR-P2 coating was carried out to EDC measurements that were taken to observe the distribution of P element. Figure 13a is the cross-section of coating and substrate, which shows that the distribution of P elements is more concentrated in the contact measurement part of coating and substrate, while Figure 13b is the cross-section of PTFE film formation, where the distribution of P elements is more uniform, which also shows that the phosphonate groups of EL@AR-P2 are distributed on the surface of the substrate during the process of film formation. To determine whether the phosphonate groups exhibit polar migration behavior and whether the phosphonate ester chelates with the substrate surface, XPS was used to characterize the cross-section of the EL@AR-P2 coating. Figure 14a proves that the P element is indeed present in the cross-section where the coating is in contact with the substrate. After treatment, the peak of the P element can be divided into three peaks, located at 131.7, 132.2, and 132.6 eV, respectively. The peaks at 131.7 and 132.2 eV belong to PO43−. The peak at 132.6 eV belongs to P–O–Fe (44,45) which is formed due to the chelation of the phosphonate group with the substrate surface. To confirm the above conclusion, an XPS fit analysis of the iron element was performed. As shown in Figure 14b, the peak was divided into six peaks. The peaks at 701.2 and 709.6 eV are attributed to Fe and FeO, respectively. 711.2 eV is the characteristic peak of Fe2O3. 723.6 eV is the characteristic peak of FeOOH (46). The remaining two peaks, 713.2 and 720.3 eV, are characteristic peaks of iron chelate phosphonate. EDS and XPS results demonstrated the existence of polar migration of phosphonate groups in the film-forming process.

(a) Coating cross-section, (b) EDS of coating cross-section, (c) cross-section of PTFE film formation, (d) EDS of film cross-section, (a and c) magnification level of 200×.

XPS spectra of cross-section of the EL@AR-P2 coating: (a) P, (b) Fe.

3.10 Anticorrosion mechanism of EL@AR-P coatings

The anticorrosion mechanism of the modified EL@AR-P coatings can be explained by the variations of electrochemical and chemical reactions occurring at the coating interface. For electrochemical reactions, anodic half-reaction Eq. 2 and cathodic half-reaction Eq. 3 are the two dominant half-reactions accounting for the corrosion at the interface. The final corrosion reaction can be expressed by Eq. 4, while the presence of chloride ions as a catalyst will accelerate the corrosion reactions Eq. 5 and 6. Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that the existence of the H2O, O2, as well as Cl− in the electrolyte was the critical factor impacting the entire corrosion process of a polymer coating system. The chemical reaction that occurs at the EL@AR-P coating interface is as follows Eq. 7.

For the EL@AR-P coating, it is usually regarded as an organic barrier layer to prevent corrosive electrolytes from permeating the coatings along with the defects. The corrosion reactions near the interface of the coating/tinplate will result in the pitting and delamination of the EL@AR-P coating from the tinplate substrate. Finally, the tinplate loses protection from the EL@AR-P coating (46). The EL@AR-P2 coating slows down the O2, H2O, and Cl− invasion when compared with the EL@AR-P0 coating. The EL/AR-P2 coating improves the film formation of the composite emulsion due to the introduction of the phosphonate group and the coating is also polarized due to the polar migration. Improves the ability of the coating to bond tightly to the substrate surface, reducing possible defects in the coating and increasing the impermeability of the coating, thereby slowing down the corrosion rate of the metal substrate. Moreover, the phosphonate group can chelate with Fe2+ to reduce further corrosion reactions, which is reduced in Eq. 4, 5, and 7.

4 Conclusion

Herein, EL@AR-P coatings were prepared by ring-opening esterification and grafting, which significantly improved the impermeability of WVTR, OTR, and water resistance. This is because the film formation and film density of the material was improved by the introduction of PM-2 and acrylic molecular chains. The corrosion resistance of the coating is evaluated by EIS, SEM, NSS, and XRD. EIS, XRD, SEM, and NSS results show that the introduction of PM-2 improves the corrosion resistance of the coating and EL@AR-P2 has the best corrosion resistance when compared with other coatings. Through EDS and XPS testing and analysis, it was found that P–O–Fe bonds existed on the contact surface of the coating and the substrate, and the P element distribution was concentrated on the substrate surface. The introduction of PM-2 into the polymer chain segment promotes film-forming properties and also makes the polymer chain segment more tightly bonded to the substrate after film formation. The phosphonate group also can chelate with Fe2+ to reduce further corrosion reactions. This work offers a strategy for the fabrication of eco-friendly and cost-effective waterborne coatings by the molecular-level design of epoxy resin, which opens up a new way to prepare high-performance waterborne coatings for industry.

References

(1) Zhang Y, Tian J, Zhong J, Shi X. Thin nacre-biomimetic coating with super-anticorrosion performance. ACS Nano. 2018;12:10189–200.10.1021/acsnano.8b05183Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(2) Shi X, Fay L, Yang Z, Nguyen TA, Liu Y. Corrosion of deicers to metals in transportation infrastructure: introduction and recent developments. Corros Rev. 2009;27:23.10.1515/CORRREV.2009.27.1-2.23Search in Google Scholar

(3) Ikechukwu EE, Pauline EO. Environmental impacts of corrosion on the physical properties of copper and aluminium: a case study of the surrounding water bodies in Port Harcourt. Open J Soc Sci. 2015;3:143.10.4236/jss.2015.32019Search in Google Scholar

(4) Chang C-H, Huang T-C, Peng C-W, Yeh T-C, Lu H-I, Hung W-I, et al. Novel anticorrosion coatings prepared from polyaniline/graphene composites. Carbon. 2012;50:5044–51.10.1016/j.carbon.2012.06.043Search in Google Scholar

(5) Pourhashem S, Vaezi MR, Rashidi A, Bagherzadeh MR. Exploring corrosion protection properties of solvent based epoxy-graphene oxide nanocomposite coatings on mild steel. Corros Sci. 2017;115:78–92.10.1016/j.corsci.2016.11.008Search in Google Scholar

(6) Xie Z-H, Shan SJ. Nanocontainers-enhanced self-healing Ni coating for corrosion protection of Mg alloy. J Mater Sci. 2018;53:3744–55.10.1007/s10853-017-1774-2Search in Google Scholar

(7) Chen C, Qiu S, Cui M, Qin S, Yan G, Zhao H, et al. Achieving high performance corrosion and wear resistant epoxy coatings via incorporation of noncovalent functionalized graphene. Carbon. 2017;114:356–66.10.1016/j.carbon.2016.12.044Search in Google Scholar

(8) Li S-X, Wang W-F, Liu L-M, Liu G-Y. Morphology and characterization of epoxy-acrylate composite particles. Polym Bull. 2008;61:749–757.10.1007/s00289-008-1000-0Search in Google Scholar

(9) Rad ER, Vahabi H, de Anda AR, Saeb MR, Thomas S. Bio-epoxy resins with inherent flame retardancy. Prog Org Coat. 2019;135:608–12.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.05.046Search in Google Scholar

(10) Fang F, Huo S, Shen H, Ran S, Wang H, Song P, et al. A bio-based ionic complex with different oxidation states of phosphorus for reducing flammability and smoke release of epoxy resins. Compos Commun. 2020;17:104–8.10.1016/j.coco.2019.11.011Search in Google Scholar

(11) Habib F, Bajpai M. Synthesis and characterization of acrylated epoxidized soybean oil for UV cured coatings. Chem Chem Technol. 2011;5(3):317–26.10.23939/chcht05.03.317Search in Google Scholar

(12) Athawale VD, Nimbalkar RV. Waterborne coatings based on renewable oil resources: an overview. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2011;88:159–85.10.1007/s11746-010-1668-9Search in Google Scholar

(13) Aigbodion A, Okieimen F, Obazee E, Bakare IJ. Utilisation of maleinized rubber seed oil and its alkyd resin as binders in water-borne coatings. Prog Org Coat. 2003;46:28–31.10.1016/S0300-9440(02)00181-9Search in Google Scholar

(14) Aigbodion A, Okieimen F, Ikhuoria E, Bakare I, Obazee EJ. Rubber seed oil modified with maleic anhydride and fumaric acid and their alkyd resins as binders in water-reducible coatings. J Appl Polym Sci. 2003;89:3256–9.10.1002/app.12446Search in Google Scholar

(15) Shah MY, Ahmad SJ. Waterborne vegetable oil epoxy coatings: Preparation and characterization. Prog Org Coat. 2012;75:248–52.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2012.05.001Search in Google Scholar

(16) Cao M, Wang H, Cai R, Ge Q, Jiang S, Zhai L, et al. Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified tung oil waterborne insulation varnish. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132:1–8.10.1002/app.42755Search in Google Scholar

(17) Deligöz H, Yalcınyuva T, Özgümüs SJ. A novel type of Si-containing poly (urethane-imide)s: synthesis, characterization and electrical properties. Polymer. 2005;41:771–81.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2004.11.007Search in Google Scholar

(18) Lauter U, Kantor SW, Schmidt-Rohr K, MacKnight W. Vinyl-substituted silphenylene siloxane copolymers: novel high-temperature elastomers. Macromolecules. 1999;32:3426–31.10.1021/ma981292fSearch in Google Scholar

(19) Wang G, Yang JJS, Technology C. Influences of binder on fire protection and anticorrosion properties of intumescent fire resistive coating for steel structure. Surf Coat Technol. 2010;204:1186–92.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2009.10.040Search in Google Scholar

(20) Bhuniya S, Adhikari BJ. Toughening of epoxy resins by hydroxy-terminated, silicon-modified polyurethane oligomers. J Appl Polym Sci. 2003;90:1497–506.10.1002/app.12666Search in Google Scholar

(21) Zhang JD, Yang MJ, Zhu YR, Yang HJ. Synthesis and characterization of crosslinkable latex with interpenetrating network structure based on polystyrene and polyacrylate. Poly Int. 2006;55:951–960.10.1002/pi.2056Search in Google Scholar

(22) Choi J-A, Kang Y, Shim H, Kim DW, Song H-K, Kim D-W. Effect of the cross-linking agent on cycling performances of lithium-ion polymer cells assembled by in situ chemical cross-linking with tris(2-(acryloyloxy)ethyl)phosphate. J Power Sources. 2009;189:809–13.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.07.048Search in Google Scholar

(23) Woo JT, Toman A. Water-based epoxy-acrylic graft copolymer. Prog Org Coat. 1993;21:371–85.10.1016/0033-0655(93)80051-BSearch in Google Scholar

(24) Pan G, Wu L, Zhang Z, Li D. Synthesis and characterization of epoxy-acrylate composite latex. J Appl Polym Sci. 2002;83:1736–43.10.1002/app.10100Search in Google Scholar

(25) Tang E, Bian F, Klein A, El-Aasser M, Liu S, Yuan M, et al. Fabrication of an epoxy graft poly(St-acrylate) composite latex and its functional properties as a steel coating. Prog Org Coat. 2014;77:1854–60.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2014.06.027Search in Google Scholar

(26) Yao M, Tang E, Guo C, Liu S, Tian H, Gao HJ. Synthesis of waterborne epoxy/polyacrylate composites via miniemulsion polymerization and corrosion resistance of coatings. Prog Org Coat. 2017;113:143–50.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.09.008Search in Google Scholar

(27) Fei G, Sun L, Wang H, Gohar F, Ma Y, Kang Y-M. Rational design of phosphorylated poly(vinyl alcohol) grafted polyaniline for waterborne bio-based alkyd nanocomposites with high performance. Prog Org Coat. 2020;140:105484.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.105484Search in Google Scholar

(28) Liu C, Du P, Zhao H, Wang LJ. Synthesis of l-histidine-attached graphene nanomaterials and their application for steel protection. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2018;1:1385–95.10.1021/acsanm.8b00149Search in Google Scholar

(29) Ding J, Zhao H, Xu B, Zhao X, Su S, Yu HJ. Engineering, superanticorrosive graphene nanosheets through π deposition of boron nitride nanodots. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2019;7:10900–11.10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b01796Search in Google Scholar

(30) Bertuoli PT, Baldissera AF, Zattera AJ, Ferreira CA, Alemán C, Armelin E. Polyaniline coated core-shell polyacrylates: control of film formation and coating application for corrosion protection. Prog Org Coat. 2019;128:40–51.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2018.12.007Search in Google Scholar

(31) Wu C, Huang X, Wu X, Qian R, Jiang PJ. Mechanically flexible and multifunctional polymer-based graphene foams for elastic conductors and oil-water separators. Adv Mater. 2013;25:5658–62.10.1002/adma.201302406Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(32) Tielemans M, Roose P, De Groote P, Vanovervelt J-C. Colloidal stability of surfactant-free radiation curable polyurethane dispersions. Prog Org Coat. 2006;55:128–36.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.08.010Search in Google Scholar

(33) Yang S, Feng X, Wang L, Tang K, Maier J, Müllen K. Graphene-based nanosheets with a sandwich structure. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:4795–9.10.1002/anie.201001634Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(34) Du Y, Guo S, Dong S, Wang E. An integrated sensing system for detection of DNA using new parallel-motif DNA triplex system and graphene–mesoporous silica–gold nanoparticle hybrids. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8584–92.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.091Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(35) Park YT, Qian Y, Chan C, Suh T, Nejhad MG, Macosko CW, et al. Epoxy toughening with low graphene loading. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:575–85.10.1002/adfm.201402553Search in Google Scholar

(36) Ma IW, Sh A, Ramesh K, Vengadaesvaran B, Ramesh S, Arof A. Anticorrosion properties of epoxy-nanochitosan nanocomposite coating. Prog Org Coat. 2017;113:74–81.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.08.014Search in Google Scholar

(37) Li Y, Tang L, Li J. Preparation and electrochemical performance for methanol oxidation of Pt/graphene nanocomposites. Electrochem Commun. 2009;11:846–849.10.1016/j.elecom.2009.02.009Search in Google Scholar

(38) Zhong J, Zhou G-X, He P-G, Yang Z-H, Jia D-C. 3D printing strong and conductive geo-polymer nanocomposite structures modified by graphene oxide. Carbon. 2017;117:421–6.10.1016/j.carbon.2017.02.102Search in Google Scholar

(39) Pourhashem S, Vaezi MR, Rashidi A, Bagherzadeh M. Exploring corrosion protection properties of solvent based epoxy-graphene oxide nanocomposite coatings on mild steel. Corros Sci. 2017;115:78–92.10.1016/j.corsci.2016.11.008Search in Google Scholar

(40) Ruhi G, Bhandari H, Dhawan S. Designing of corrosion resistant epoxy coatings embedded with polypyrrole/SiO2 composite. Prog Org Coat. 2014;77:1484–98.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2014.04.013Search in Google Scholar

(41) Gerengi H, Tascioglu C, Akcay C, Kurtay MJI, Research EC. Impact of copper chrome boron (CCB) wood preservative on the corrosion of St37 steel. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2014;53:19192–19198.10.1021/ie5033342Search in Google Scholar

(42) Zheng H, Shao Y, Wang Y, Meng G, Liu B. Reinforcing the corrosion protection property of epoxy coating by using graphene oxide–poly(urea-formaldehyde) composites. Corros Sci. 2017;123:267–77.10.1016/j.corsci.2017.04.019Search in Google Scholar

(43) Rotole JA, Sherwood P. Oxide-free phosphate surface films on metals studied by core and valence band X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Chem Mater. 2001;13:3933–42.10.1021/cm0009468Search in Google Scholar

(44) Jalili M, Rostami M, Ramezanzadeh B. An investigation of the electrochemical action of the epoxy zinc-rich coatings containing surface modified aluminum nanoparticle. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;328:95–108.10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.12.034Search in Google Scholar

(45) Gao X, Zhao C, Lu H, Gao F, Ma H. Influence of phytic acid on the corrosion behavior of iron under acidic and neutral conditions. Electrochim Acta. 2014;150:188–96.10.1016/j.electacta.2014.09.160Search in Google Scholar

(46) Gu L, Liu S, Zhao H, Yu H. Interfaces, facile preparation of water-dispersible graphene sheets stabilized by carboxylated oligoanilines and their anticorrosion coatings. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:17641–8.10.1021/acsami.5b05531Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2020 Xuyong Chen et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery