Abstract

The demand of high-performance filter media for the face masks is urgent nowadays due to the severe air pollution. Herein, a highly breathable and thermal comfort membrane that combines the asymmetrically superwettable skin layer with the nanofibrous membrane has been fabricated via successive electrospinning and electrospraying technologies. Thanks to high porosity, interconnected pore structure, and across-thickness wettability gradient, the composite membrane with a low basis weight of 3.0 g m−2 exhibits a good air permeability of 278 mm s−1, a comparable water vapor permeability difference of 3.61 kg m−2 d−1, a high filtration efficiency of 99.3%, a low pressure drop of 64 Pa, and a favorable quality factor of 0.1089 Pa−1, which are better than those of the commercial polypropylene. Moreover, the multilayer-structured membrane displays a modest infrared transmittance of 92.1% that can keep the human face cool and comfort. This composite fibrous medium is expected to protect humans from PM2.5 and keep them comfortable even in a hygrothermal environment.

1 Introduction

Severe air pollution is currently one of the global issues that threaten human beings, which is mainly due to the emissions from on-road vehicles, industrial production activities, and dust (1,2). Therefore, cost-effective strategies to remove PM2.5 (particle diameter <2.5 µm) from air are of special importance (3,4). Wearing a face mask is considered as one of the most direct and effective methods to protect the human body. The core filter media of the face masks are usually composed of various fibers due to their distinctive structures and good processability. However, the melt-blown fiber-based filter media cannot satisfy the requirements of a face mask, owing to their limited capture property toward ultrafine particle and slow moisture evaporation rate (5), thus causing human body to feel uncomfortable and even dangerous during respiration. Nanofibers supply a dramatic promotion in PM2.5 capture efficiency and provide a sharply decreased basis weight (6). Additionally, nanofiber-based filter medium could be easily functionalized to obtain special properties, such as antibacterial activities (7), dye scavenging (8), and easy cleaning performance (9).

Benefiting from the tunable nanofiber structure, interconnected open pore structure, and high porosity, the electrospun nanofibrous membrane (NFM) was considered as a suitable filter medium for cost-effectively capturing PM2.5 (10,11,12). Based on these, a variety of electrospun fibrous media for air filtration have purposely been developed, including polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and polylactic acid (13,14). In addition, inorganic SiO2 nanoparticles (SiO2 NPs) possess the properties of good charge storage ability and stable electric field as reported in a previous study (10). Electrospinning could integrate the electret process and fiber construction into one process. Thus, by combining the electrospinning of right type of polymer and SiO2 NPs, a desired composite membrane with a hierarchical structure and good performance could be fabricated. However, nearly no effort has been put to the study on the wearing comfortability of an electrospun composite membrane, especially on the relationship between the membrane structure and wearing comfortability. Therefore, the challenge remains in developing NFMs with high filtration performance and creditable wearing comfortability. Inspired by the features of moisture-wicking technologies and push–pull effect, NFMs with an across-thickness wettability gradient have been fabricated to study the effects of surface structure and wettability on the directional moisture transport process. Based on these, a composite NFM which possesses asymmetric wettability may be a promising candidate for meeting the demands of high-performance face masks.

In this study, a sequential electrospraying approach was demonstrated for the construction of an asymmetrically superwettable skin layer that was integrated with the electrospun PAN/polyetherimide (PEI) NFM substrate to obtain a multilayer-structured nanofiber membrane (SNFM) with high PM2.5 capture performance, desirable air permeability, and good radiative cooling properties. The morphology, pore structure, breathability, and water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) can be readily controlled by simply tailoring the polymer concentration and fiber basis weight. Notably, bi-functions of low air permeability resistance and smooth directional moisture transfer were observed for the composite membrane with an across-thickness wettability gradient. Moreover, the SNFM with an outstanding radiative cooling performance is expected to significantly improve the thermal radiative dissipation in extreme environmental conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

PAN powders (P823209, Mw = 85,000) were obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd, China. PEI (Ultem 1000, Mw = 10,00,000) was provided by General Electric Company, USA. Trimethoxy(heptadecafluorotetrahydrodecyl)triethoxysilane (FAS, C13H13F17O3Si, 97%) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, AR 99.7%) was supplied by Shanghai Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd, China. Nano-fumed silica (SiO2, hydrophilic-200, 7–40 nm) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Chemical Co., China. All chemical reagents were used as received without any further processing.

2.2 Preparation of solutions

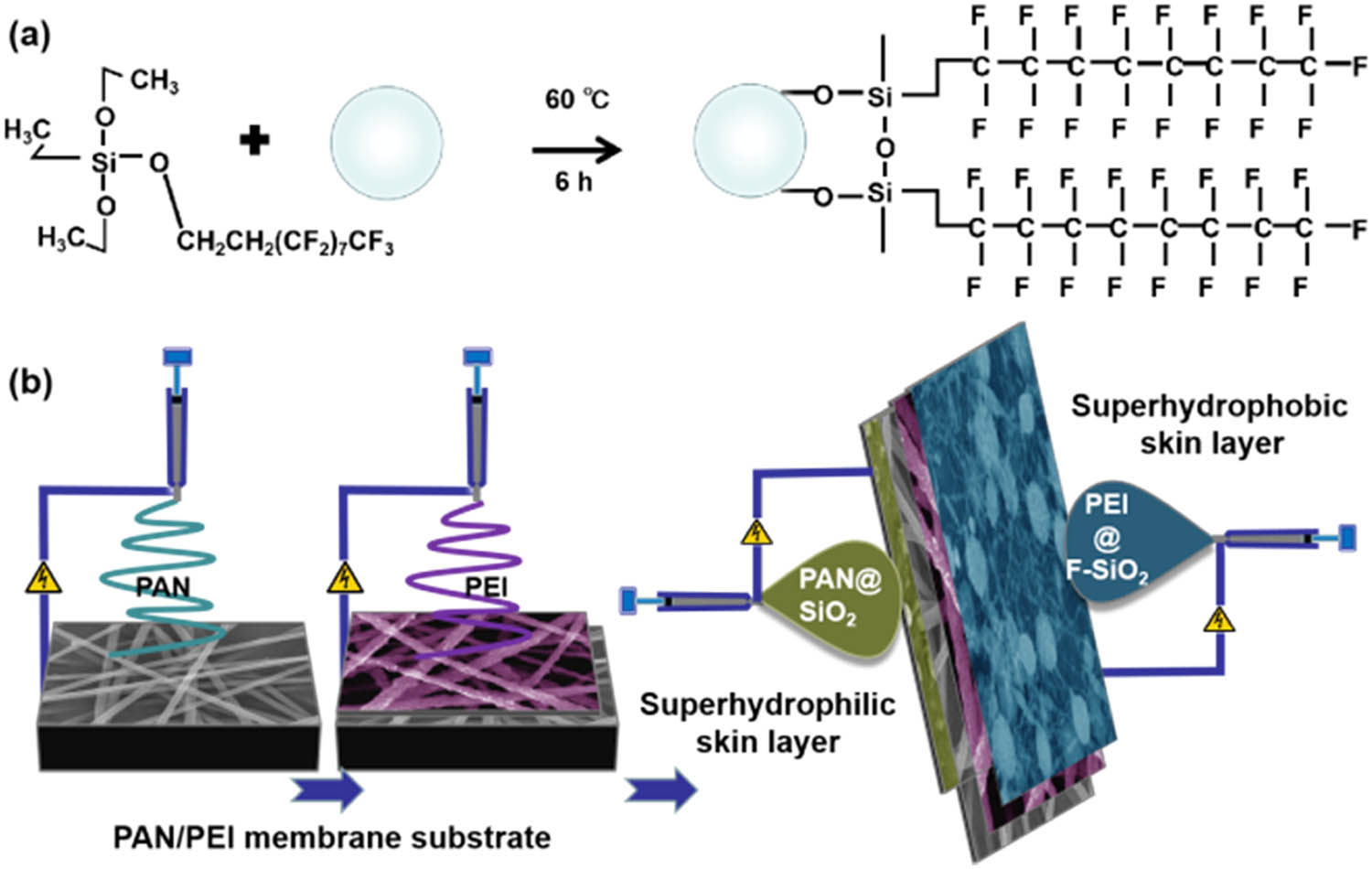

DMF was used as the solvent to prepare the PAN (10 wt%) and PEI solutions (12 wt%), which were constantly stirred for 10 h with a stirring rate of 800 ± 50 rpm at room temperature, separately. A PEI solution (6 wt%) containing 6 wt% superhydrophobic silica nanoparticles (SiO2 NPs) was obtained through the following procedure: first, 0.036 g of SiO2 NPs was uniformly dispersed in 9.4 g of DMF under continuous stirring with a rate of 800 ± 50 rpm at room temperature for 30 min, followed by sonication treatment for another 30 min, and then 0.072 g of FAS was added to the above mixture and stirred at 60°C for 6 h. The detailed preparation process of FAS-modified superhydrophobic SiO2 NPs (F-SiO2) is shown in Figure 1a. Finally, 0.6 g of PEI was injected into the prepared suspension followed by stirring for 8 h. A PAN solution (5 wt%) containing SiO2 NPs (4 wt%) was also obtained via the same method as that of the PEI solution containing F-SiO2 NPs.

(a) Schematic diagram of the preparation of superhydrophobic SiO2 NPs. (b) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of the PAN/PEI bilayer membranes and the asymmetric superwettability skin layers.

2.3 Fabrication of multilayered fibrous membranes

First, PAN and PEI fibers were separately fabricated via electrospinning with a feed rate of 2 mL h−1, and the obtained double-layered composite membranes were denoted as PAN/PEI NFMs. Additionally, the skin layer was prepared by electrospraying the resultant SiO2@PAN and F-SiO2@PEI solutions with the same feed rate of 0.3 mL h−1 and the generated fibers were continuously deposited on the electrospun PAN and PEI membranes. The parameters used during the fabrication process were as follows: the applied voltage was fixed at 25 kV, the tip-to-collector distance was fixed at 15 cm, the temperature was 25 ± 2°C, and the relative humidity was 45 ± 5%.

2.4 Characterization

The morphology and structure of the as-prepared fibers were characterized by a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Phenom ProX, Phenom World, USA). A bubble point method was applied to test the pore size distribution (PSD) of the membranes on a Pore Size Meter (PSM165; Topas GmbH, Dresden, Germany). A standard solution with a surface tension of 16 dynes/cm was used as the wetting liquid. The prepared membrane was immersed in this wetting liquid, and then the pore size was tested with the pressure ranging from 0 to 58 psi. The filtration performance was measured using an automated filter tester (Filter Media Test RIG AFC 131; Topas GmbH, Dresden, Germany). The tester could deliver charge-neutralized NaCl aerosol particles with a diameter of 300–500 nm. At a flow rate of 33 L/min, the NaCl aerosol particles entered pipe of the filter tester and passed through the filter medium with a diameter of 18 cm which was sandwiched between the upper and lower pipes of the filter tester before the test beginning. The air flow resistance was tested with two electronic pressure transducers by detecting the pressure through the filter medium under testing. The test was conducted at room temperature (22 ± 3°C) with a flow rate of 85 ± 3 L/min. The air permeability was measured by a Frazier Air Permeability Tester (FX3300; Textest AG, Switzerland) with an effective area of 20 cm2 and a pressure drop of 200 Pa. The water vapor transportation rate of the relevant membranes was investigated by the computer-type fabric moisture permeability testing apparatus (YG601H-Ⅱ; Ningbo Textile Instrument Factory, China) based on the GB/T 12704.2-2009 standard test method.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphology

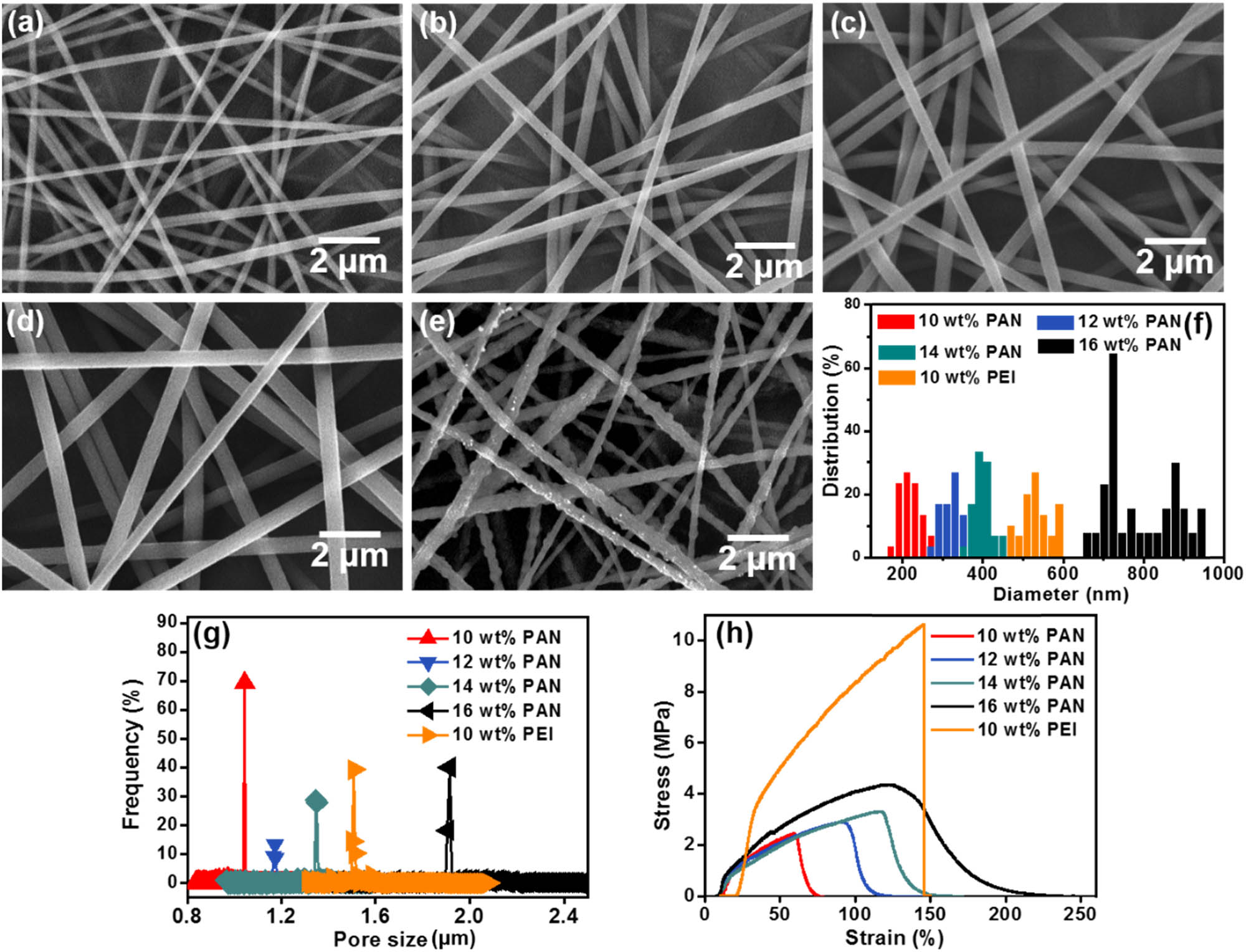

In order to obtain a high-performance filtration membrane with both good breathable and directional moisture transport properties for the face mask that has favorable wearing comfortability, an asymmetrically superwettable membrane with a surface wettability gradient was constructed by integrating superwettable skin layers with an open porous structured composite membrane. The basic composite fibrous membrane with nonwoven architecture was obtained by the versatile, readily accessible electrospinning technique. The representative SEM images of the PAN NFMs derived from various solution concentrations and the PEI NFMs shown in Figure 2a–e illustrate that the electrospun PAN and PEI NFMs were 3D nonwoven membranes assembled with randomly oriented nanofibers. The average diameter of PAN nanofibers increased gradually from 211 to 715 nm as the solution concentration increased from 10 to 16 wt%. This should be attributed to the enhanced viscosity and surface tension extensively studied in the previous studies (15,16,17). The open network porous structure changed accordingly as the fiber diameter varied. The PSD also exhibited the same increasing trend with the changes in the fiber diameter as displayed in Figure 2g. Besides, the mechanical robustness, an important parameter in practical face masks, is significantly affected by the solution concentration (18). The tensile stresses of PAN NFMs and PEI membranes are 2.47, 2.89, 3.36, 4.42, and 10.65 MPa, respectively. All the NFMs show a characteristic nonlinear elongation behavior until breakage, which is ascribed to the dynamic deformation and the alleged “pull-out” slipping of single fiber along the stress loading direction. The frictional entanglement resulting from the increase in the fiber diameter and the slipping resistance may be the main reasons for the incremental tensile stress (19,20).

SEM images of PAN membranes obtained from various concentrations (a)–(d) and PEI fibrous membrane (e). Fiber diameter distribution (f), PSD (g), and stress–strain curves (h) of the relevant membranes.

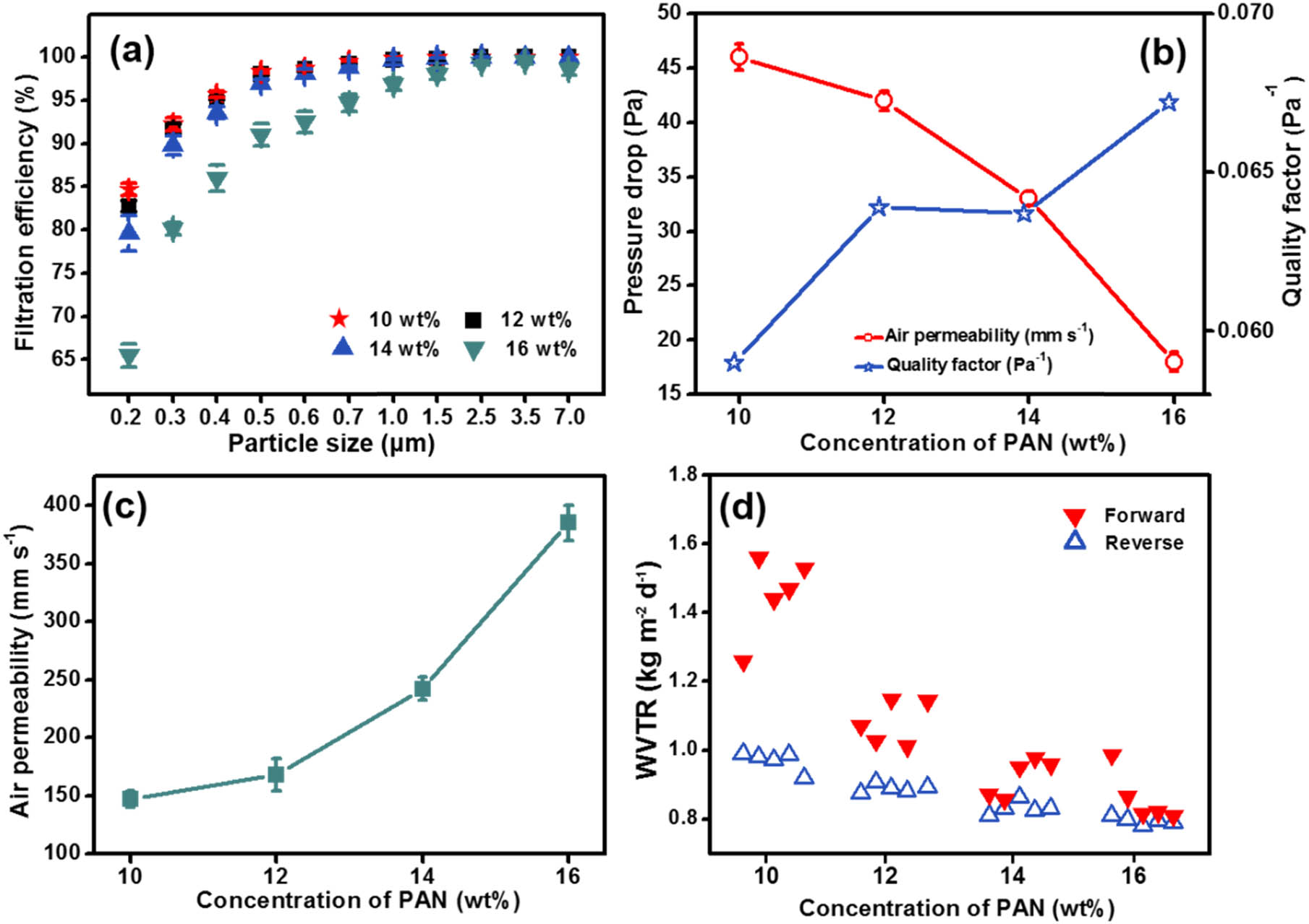

On the basis of the fact that the fiber diameter and pore structure would have a great influence on the capture process of PM2.5, the air filtration performance of the obtained PAN/PEI composite membranes with various microstructures was carefully studied. Figure 3a presents the dependence of the filtration efficiency of the PAN/PEI composite NFMs on the particle size in the range of 0.2–7 µm. The filtration efficiency of NFM10 (93.6%) is superior compared with that of NFM16 (80.6%) toward 0.3 µm particles at a basis weight of 0.6 g m−2. Meanwhile, the filtration efficiency of NFMs improved with the increase in the particle size, owing to the effective interception mechanism. Besides, the filtration performance strongly relies on the packing density (21). The low packing density of membrane would reduce the tortuous path for the air flow to travel through, thus reducing the pressure drop of NFM. Although the samples from NFM10 to NFM16 have the equivalent basis weight, they displayed different pressure drops resulting from the change in the packing density (Figure 3b). The trade-off parameter between the pressure drop and filtration efficiency, known as quality factor (QF), was used to evaluate the overall filtration performance (22,23). The QF was calculated by the formula as follows:

where η is the filtration efficiency (%) and DP is the pressure drop (Pa) of the relevant NFM. As shown in Figure 3b, the QF values are 0.059, 0.0639, 0.0637, and 0.0672 Pa−1 for the bilayer NFMs, respectively, indicating the benefit-to-cost roles of fiber and pore structure toward the construction of bilayer structure.

Filtration efficiency (a), pressure drop (b), air permeability and QF (c), and WVTR (d) of PAN/PEI composite membranes with varying PAN concentrations. The basis weight of the composite NFMs was 0.6 g m−2.

3.2 Performances of PAN/PEI membranes

According to the previous studies, air permeability and moisture transfer are two important indicators of the wear comfort behavior for human respiration (9). Figure 3c and d shows the variations in air permeability and WVTR with the solution concentration of PAN. The air permeability improved from 147 to 385 mm s−1 with the increase in the PAN concentration, and the values present positive correlation with pore size, as shown in Figure 3c. It is obvious that a forward WVTR of 1.56 kg m−2 d−1 and a ΔWVTR of 0.62 kg m−2 d−1 were achieved when the PAN concentration was 10 wt%, suggesting the good moisture transfer performance of the NFM10 was due to the relatively higher porosity.

3.3 Morphology of skin layers

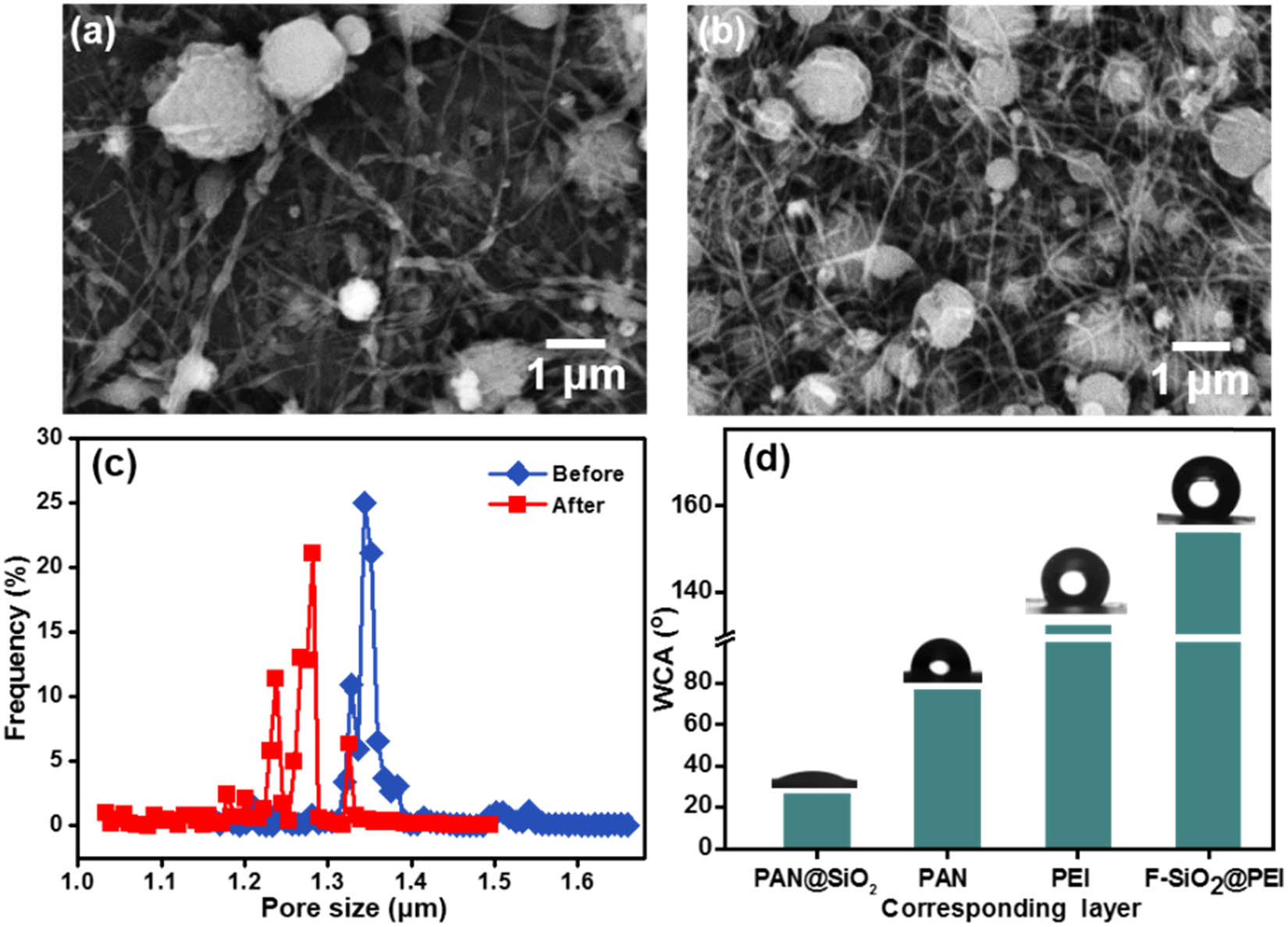

In order to improve the directional moisture transport ability, a functional skin layer with asymmetric superwettability was fabricated via a successive electrospraying method to obtain a surface energy gradient through the membrane. Figure 4a and b displays the typical SEM images of the optimal hydrophilic and superhydrophobic surfaces. It can be observed that all the microspheres with a diameter ranging from 0.2 to 1.8 μm hang together with the ultrathin fibers. The SiO2 NPs played a key role in constructing nanoscale roughness on the surfaces of microspheres and fibers, because the polymer droplets would shrink during the solvent evaporation process (24,25).

SEM images of PAN@SiO2 (a) and F-SiO2@PEI skin layers (b). PSD curves of the membranes with asymmetric superwettability (c). WCA of the corresponding layer of the membranes (d).

As can be seen in Figure 4c, an irregular pore structure is confirmed for the bilayer PAN/PEI NFM with a pore size in the range of 1.26–1.61 µm (average pore size: 1.44 µm), and this is due to the different diameters of PAN and PEI fibers. Nevertheless, after spraying the SiO2@PAN and F-SiO2@PEI solutions onto the NFM substrate, we observed the substantial decrease in the average pore size to 1.27 µm, which is attributed to the dense accumulation of microspheres-on-string-structured fibers.

Figure 4d shows the water contact angle (WCA) of the corresponding layer of the composite membrane, and the WCA values of PAN, PEI, SiO2@PAN, and F-SiO2@PEI are 76.6°, 132.1°, 26.3°, and 153.7°, respectively. The asymmetric wettability was obtained to investigate the effects of hydrophilic degree and surface roughness on the directional moisture transport process. Additionally, the skin layers strongly adhered to the bilayer PAN/PEI NFM substrate, resulting from the solvent that did not evaporate in time and the robust electrostatic forces produced in the electrospraying process.

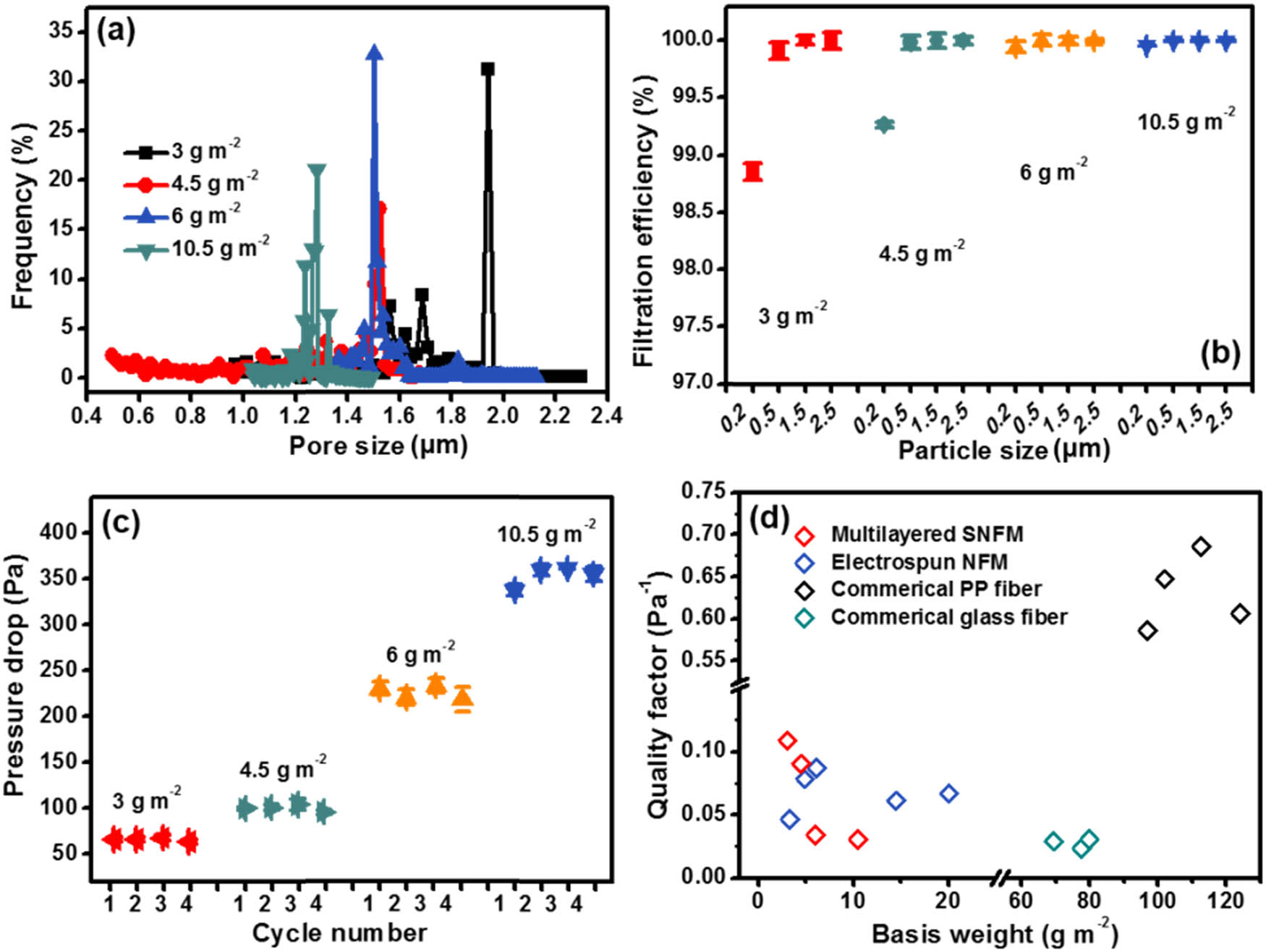

3.4 Filtration performances of multilayered composite membranes

The integration of skin layer endowed the membranes with a desirable surface roughness, small fiber diameter, and high effective surface area, which greatly reduced the pore size and fiber contact area, finally enhancing the filtration performance. The pore sizes of all samples ranged from 0.44 to 2.37 µm and sequentially declined from 1.92 to 1.25 µm with the increase in the fiber basis weight from 3 to 10.5 g m2 (Figure 5a). The pore size was inversely proportional to the fiber basis weight, owing to the gradual reduction in the tortuosity and pore interconnectivity of the fibrous membranes.

PSD (a), filtration efficiency (b), pressure drop (c), and QF values of SNFMs with various basis weights (d).

Figure 5b displays the dependence of the filtration efficiency of the SNFMs on the 0.2 to 2.5 µm particles. The results showed that the increased fiber mass was likely to result in the increase in the contact points in the fibrous media and the tortuous airflow channels, finally leading to the improved pressure drop (64–338 Pa) (Figure 5c). Interestingly, the particle capture efficiency of SNFMs at a small fiber basis weight was much lower than that of large particles (larger than 0.3 µm). This phenomenon can be explained by the straining of aerosols as well as the diffusion and interception mechanisms when the size of ultrafine particles is close to the fiber diameter (21,26).

Figure 5d displays the QF values of various fiber media as a function of basis weight. The commercial polypropylene (PP) melt-blown fibers possess a relatively high QF value of 0.5862 Pa−1, but have a large basis weight (>90 g m−2), which are not beneficial for breathing. The lightweight character of the electrospun fiber-based media (<10 g m−2) can not only promote the wearing comfort performance but also give more chance for the entire design of the protection masks. Besides, benefiting from the multivariate fiber structures and construction processes, the QF can be further increased, on account of the enhanced capture efficiency. A high QF value of 0.1089 Pa−1 was achieved for the SNFM fibrous media with a basis weight of 3 g m−2 (Figure 5d), much higher than that for the previously reported electrospun media (27).

3.5 Wearing comfortability

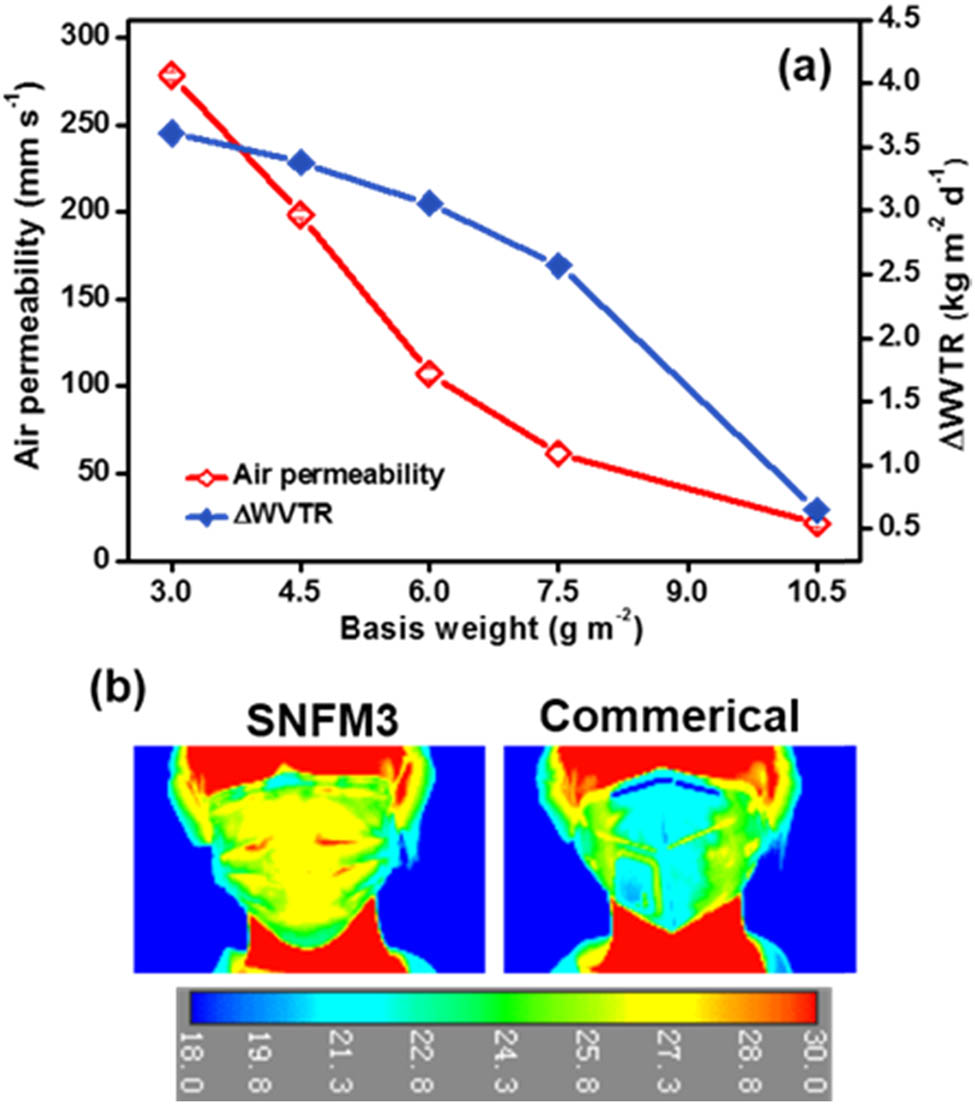

To evaluate the wearing comfortability of the as-prepared composite SNFMs, air permeability and moisture transfer performance were systematically investigated (28). The variations in air permeability and ΔWVTR with various fiber basis weights are illustrated in Figure 6a. Obviously, the air permeability value was significantly reduced from 278 to 21 mm s−1 with the increase in the fiber mass, which could be explained using the Fickian diffusion model. Specifically, the diffusion flux is positively correlated with the diffusion coefficient that is indirectly determined by the fiber basis weight (29). Interestingly, a ΔWVTR value of 3.61 kg m−2 d−1 was obtained when the fiber mass was fixed at 3 g m−2, demonstrating the excellent unidirectional moisture transport property of the sample of SNFM3. Based on this, a conclusion may be drawn that the wearing comfortability can be effectively regulated by controlling the fiber basis weight.

Air permeability and ΔWVTR of SNFMs with various basis weights (a) and thermal images of faces covered with SNFM3 (left) and the commercial face mask (right) (b).

In addition, there is an urgent need for the thermal comfort face masks that could greatly save the energy consumption of human body, especially in high-temperature and high-humidity environments (30,31). The thermal infrared transmittance of SNFM3 and the commercial PP membrane were 92.1 and 2.16%, which indicated that the as-prepared composite medium possessed a distinct radiative cooling property (Figure 6b). This result could be interpreted as almost all body radiation was transmitted by the ultralight mass and high porosity (32,33). The commercial face mask with a large pore size (>1 μm) and high basis weight (>90 g m−2) usually traps air and creates insulation inside the pores to block heat transfer, thus leading to low radiation capability. The relevant comparison of the relevant properties of the multilayer-structured SNFM3 and commercial PP membrane is displayed in Table A1.

4 Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated a feasible and facile strategy to develop nanofibrous filter media for the face masks with excellent properties. By tailoring the structures, pores, and wettability of the composite membranes, the filtration performance and wearing comfortability were greatly improved. It has been proved that the air and moisture permeability was linearly dependent on the porosity. Moreover, because of the ultralight basis weight and across-thickness wettability gradient, the SNFM3 exhibited a high filtration efficiency (99.3%), a low pressure drop (64 Pa), a good air permeability (278 mm s−1), and a desirable water vapor permeability difference (3.61 kg m−2 d−1), which are beneficial to the actual applications in personal protective devices. Importantly, the SNFM3 presented a stable radiative dissipation ability, capable of maintaining the face cool and comfortable in a hygrothermal environment. This work could provide a versatile method for designing multifunctional fibrous media for high-performance face masks. More significantly, how to promote the effective utilization in a high-moisture environment with wearing a face mask is still a challenge. Electrical stimulation motivated by moisture can not only obtain lots of electric charges to capture air pollutants but also achieve the antibacterial property; this will be an attractive development direction in air filtration.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51703103) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018M642609) and was conducted in Qingdao University.

Appendix

Comparison of the relevant properties of multilayer structured SNFM3 and commercial PP membranes

| Sample | Basis weight (g m−2) | Air permeability (mm s−1) | Comparable water vapor permeability (kg m−2 d−1) | Filtration efficiency (%) | Pressure drop (Pa) | FTIR transmittance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNFM3 | 3.0 | 278 | 3.61 | 99.3 | 64 | 92.1 |

| PP membrane | 90.2 | 203 | 0.48 | 99.7 | 132 | 2.16 |

References

(1) Singh VK, Ravi SK, Sun WX, Tan SC. Transparent nanofibrous mesh self-assembled from molecular legos for high efficiency air filtration with new functionalities. Small. 2017;13:1601924.10.1002/smll.201601924Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(2) Wang XX, Xiang HF, Song C, Zhu DY, Sui JX, Liu Q, et al. Highly efficient transparent air filter prepared by collecting-electrode-free bipolar electrospinning apparatus. J Hazard Mater. 2020;385:121535.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121535Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(3) Liu C, Hsu PC, Lee HW, Ye M, Zheng G, Liu N, et al. Transparent air filter for high-efficiency PM2.5 capture. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6205.10.1038/ncomms7205Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(4) Yang X, Liu S, Shao P, He J, Liang Y, Zhang B, et al. Effectively controlling hazardous airborne elements: insights from continuous hourly observations during the seasons with the most unfavorable meteorological conditions after the implementation of the APPCAP. J Hazard Mater. 2020;387:121710.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121710Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(5) Wang S, Zhao X, Yin X, Yu J, Ding B. Electret polyvinylidene fluoride nanofibers hybridized by polytetrafluoroethylene nanoparticles for high-efficiency air filtration. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:23985–94.10.1021/acsami.6b08262Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(6) Lv D, Zhu MM, Jiang ZC, Jiang SH, Zhang QL, Xiong RH, et al. Green Electrospun nanofibers and their application in air filtration. Macromol Mater Eng. 2018;303:1800336.10.1002/mame.201800336Search in Google Scholar

(7) Zhu MM, Xiong RH, Huang CB. Bio-based and photocrosslinked electrospun antibacterial nanofibrous membranes for air filtration. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;205:55–62.10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.075Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(8) Lv D, Wang RX, Tang GS, Mou ZP, Lei JD, Han JQ, et al. Ecofriendly electrospun membranes loaded with visible-light responding nanoparticles for multifunctional usages: highly efficient air filtration, dye scavenging, and bactericidal activity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:12880–9.10.1021/acsami.9b01508Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(9) Zhao LY, Duan GG, Zhang GY, Yang HQ, He SJ, Jiang SH. Electrospun functional materials toward food packaging applications: a review. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:150.10.3390/nano10010150Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(10) Hu M, Yin LH, Low N, Ji DH, Liu YS, Yao JF, et al. Zeolitic-imidazolate-framework filled hierarchical porous nanofiber membrane for air cleaning. J Membr Sci. 2020;594:117467.10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117467Search in Google Scholar

(11) Wu JJ, Akampumuza O, Liu PH, Quan ZZ, Zhang HN, Qin XH, et al. 3D structure design and simulation for efficient particles capture: the influence of nanofiber diameter and distribution. Mater Today Commun. 2020;23:100897.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.100897Search in Google Scholar

(12) Zhang J, Zhang F, Song J, Liu L, Si Y, Yu J, et al. Electrospun flexible nanofibrous membranes for oil/water separation. J Mater Chem A. 2019;7:20075–102.10.1039/C9TA07296ASearch in Google Scholar

(13) Zhang JF, Chen GJ, Bhat GS, Azari H, Pen HL. Electret characteristics of melt-blown polylactic acid fabrics for air filtration application. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137:48309.10.1002/app.48309Search in Google Scholar

(14) Huang JJ, Tian YX, Wang R, Tian M, Liao Y. Fabrication of bead-on-string polyacrylonitrile nanofibrous air filters with superior filtration efficiency and ultralow pressure drop. Sep Purif Technol. 2020;237:116377.10.1016/j.seppur.2019.116377Search in Google Scholar

(15) Wang N, Yang Y, Al-Deyab SS, El-Newehy M, Yue J, Ding B. Ultra-light 3D nanofibre-nets binary structured nylon 6-polyacrylonitrile membranes for efficient filtration of fine particulate matter. J Mater Chem A. 2015;3:23946–54.10.1039/C5TA06543GSearch in Google Scholar

(16) Lasprilla-Botero J, Álvarez-Láinez M, Lagaron JM. The influence of electrospinning parameters and solvent selection on the morphology and diameter of polyimide nanofibers. Mater Today Commun. 2018;14:1–9.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2017.12.003Search in Google Scholar

(17) Liu H, Cao CY, Huang JY, Chen Z, Chen GQ, Lai YK. Progress on particulate matter filtration technology: basic concepts, advanced materials, and performances. Nanoscale. 2020;12:437–53.10.1039/C9NR08851BSearch in Google Scholar

(18) Susanto H, Ulbricht M. Characteristics, performance and stability of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes prepared by phase separation method using different macromolecular additives. J Membr Sci. 2009;327:125–35.10.1016/j.memsci.2008.11.025Search in Google Scholar

(19) Wang N, Raza A, Si Y, Yu J, Sun G, Ding B. Tortuously structured polyvinyl chloride/polyurethane fibrous membranes for high-efficiency fine particulate filtration. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;398:240–6.10.1016/j.jcis.2013.02.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(20) Zhu Z, Liu Z, Zhong L, Song C, Shi W, Cui F, Wang W. Breathable and asymmetrically superwettable Janus membrane with robust oil-fouling resistance for durable membrane distillation. J Membr Sci. 2018;563:602–9.10.1016/j.memsci.2018.06.028Search in Google Scholar

(21) Kadam V, Kyratzis IL, Truong YB, Schutz J, Wang LJ, Padhye R. Electrospun bilayer nanomembrane with hierarchical placement of bead-on-string and fibers for low resistance respiratory air filtration. Sep Purif Technol. 2019;224:247–54.10.1016/j.seppur.2019.05.033Search in Google Scholar

(22) Rajak A, Hapidin DA, Iskandar F, Munir MM, Khairurrijal K. Electrospun nanofiber from various source of expanded polystyrene (EPS) waste and their characterization as potential air filter media. Waste Manage. 2020;103:76–86.10.1016/j.wasman.2019.12.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(23) Liu H, Zhang S, Liu L, Yu J, Ding B. A fluffy dual-network structured nanofiber/net filter enables high-efficiency air filtration. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29:1904108.10.1002/adfm.201904108Search in Google Scholar

(24) Al-Attabi R, Morsi Y, Kujawski W, Kong LX, Schutze JA, Dumee LF. Wrinkled silica doped electrospun nano-fiber membranes with engineered roughness for advanced aerosol air filtration. Sep Purif Technol. 2019;215:500507.10.1016/j.seppur.2019.01.049Search in Google Scholar

(25) Zhong LG, Wang T, Liu LY, Du WH, Wang S. Ultra-fine SiO2 nanofilament-based PMIA: a double network membrane for efficient filtration of PM particles. Sep Purif Technol. 2018;202:357–64.10.1016/j.seppur.2018.03.053Search in Google Scholar

(26) Gao X, Gou J, Zhang L, Duan S, Li C. A silk fibroin based green nano-filter for air filtration. RSC Adv. 2018;8:8181–9.10.1039/C7RA12879GSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(27) Wang Z, Zhao C, Pan Z. Porous bead-on-string poly(lactic acid) fibrous membranes for air filtration. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2015;441:121–9.10.1016/j.jcis.2014.11.041Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(28) Hegde M, Meenakshisundaram V, Chartrain N, Sekhar S, Tafti D, Williams CB, et al. 3D printing all-aromatic polyimides using mask-projection stereolithography: processing the nonprocessable. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1701240.10.1002/adma.201701240Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(29) Sheng J, Xu Y, Yu J, Ding B. Robust fluorine-free superhydrophobic aminosilicone oil/SiO2 modification of electrospun polyacrylonitrile membranes for waterproof-breathable application. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:15139–47.10.1021/acsami.7b02594Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(30) Kynaston JW, Smith T, Batt J. Cost awareness of disposable surgical equipment and strategies for improvement: cross sectional survey and literature review. J Perioper Pract. 2017;27:211–6.10.1177/175045891702701002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(31) Hsu PC, Liu X, Liu C, Xie X, Lee HR, Welch AJ, et al. Personal thermal management by metallic nanowire-coated textile. Nano Lett. 2015;15:365–71.10.1021/nl5036572Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(32) Yang A, Cai L, Zhang R, Wang J, Hsu PC, Wang H, et al. Thermal management in nanofiber-based face mask. Nano Lett. 2017;17:35063510.10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00579Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(33) Gao ZY, Lou Z, Chen S, Li L, Jiang K, Fu ZL, et al. Fiber gas sensor-integrated smart face mask for room-temperature distinguishing of target gases. Nano Res. 2018;11:511–9.10.1007/s12274-017-1661-9Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Yuyan Yang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The regulatory effects of the number of VP(N-vinylpyrrolidone) function groups on macrostructure and photochromic properties of polyoxometalates/copolymer hybrid films

- How the hindered amines affect the microstructure and mechanical properties of nitrile-butadiene rubber composites

- Novel benzimidazole-based conjugated polyelectrolytes: synthesis, solution photophysics and fluorescent sensing of metal ions

- Study on the variation of rock pore structure after polymer gel flooding

- Investigation on compatibility of PLA/PBAT blends modified by epoxy-terminated branched polymers through chemical micro-crosslinking

- Investigation on degradation mechanism of polymer blockages in unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs

- Investigation on the effect of active-polymers with different functional groups for EOR

- Fabrication and characterization of hexadecyl acrylate cross-linked phase change microspheres

- Surface-induced phase transitions in thin films of dendrimer block copolymers

- ZnO-assisted coating of tetracalcium phosphate/ gelatin on the polyethylene terephthalate woven nets by atomic layer deposition

- Animal fat and glycerol bioconversion to polyhydroxyalkanoate by produced water bacteria

- Effect of microstructure on the properties of polystyrene microporous foaming material

- Synthesis of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate) containing trityl ether acid cleavable junction group and its self-assembly into ordered nanoporous thin films

- On-demand optimize design of sound-absorbing porous material based on multi-population genetic algorithm

- Enhancement of mechanical, thermal and water uptake performance of TPU/jute fiber green composites via chemical treatments on fiber surface

- Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber–clay nanocomposites through incorporation of silanated organoclay into natural rubber latex

- Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material

- Preparation of novel amphoteric polyacrylamide and its synergistic retention with cationic polymers

- Effect of montmorillonite on PEBAX® 1074-based mixed matrix membranes to be used in humidifiers in proton exchange membrane fuel cells

- Insight on the effect of a piperonylic acid derivative on the crystallization process, melting behavior, thermal stability, optical and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactic acid)

- Lipase-catalyzed synthesis and post-polymerization modification of new fully bio-based poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate) and poly(hexamethylene γ-ketopimelate-co-hexamethylene adipate) copolyesters

- Dielectric, mechanical and thermal properties of all-organic PI/PSF composite films by in situ polymerization

- Morphological transition of amphiphilic block copolymer/PEGylated phospholipid complexes induced by the dynamic subtle balance interactions in the self-assembled aggregates

- Silica/polymer core–shell particles prepared via soap-free emulsion polymerization

- Antibacterial epoxy composites with addition of natural Artemisia annua waste

- Design and preparation of 3D printing intelligent poly N,N-dimethylacrylamide hydrogel actuators

- Multilayer-structured fibrous membrane with directional moisture transportability and thermal radiation for high-performance air filtration

- Reaction characteristics of polymer expansive jet impact on explosive reactive armour

- Synthesis of a novel modified chitosan as an intumescent flame retardant for epoxy resin

- Synthesis of aminated polystyrene and its self-assembly with nanoparticles at oil/water interface

- The synthesis and characterisation of porous and monodisperse, chemically modified hypercrosslinked poly(acrylonitrile)-based terpolymer as a sorbent for the adsorption of acidic pharmaceuticals

- Crystal transition and thermal behavior of Nylon 12

- All-optical non-conjugated multi-functionalized photorefractive polymers via ring-opening metathesis polymerization

- Fabrication of LDPE/PS interpolymer resin particles through a swelling suspension polymerization approach

- Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy

- Synthesis, electropolymerization, and electrochromic performances of two novel tetrathiafulvalene–thiophene assemblies

- Wetting behaviors of fluoroterpolymer fiber films

- Plugging mechanisms of polymer gel used for hydraulic fracture water shutoff

- Synthesis of flexible poly(l-lactide)-b-polyethylene glycol-b-poly(l-lactide) bioplastics by ring-opening polymerization in the presence of chain extender

- Sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) functionalized polysilsesquioxane hybrid membranes with enhanced proton conductivity

- Fmoc-diphenylalanine-based hydrogels as a potential carrier for drug delivery

- Effect of diacylhydrazine as chain extender on microphase separation and performance of energetic polyurethane elastomer

- Improved high-temperature damping performance of nitrile-butadiene rubber/phenolic resin composites by introducing different hindered amine molecules

- Rational synthesis of silicon into polyimide-derived hollow electrospun carbon nanofibers for enhanced lithium storage

- Synthesis, characterization and properties of phthalonitrile-etherified resole resin

- Highly thermally conductive boron nitride@UHMWPE composites with segregated structure

- Synthesis of high-temperature thermally expandable microcapsules and their effects on foaming quality and surface quality of foamed ABS materials

- Tribological and nanomechanical properties of a lignin-based biopolymer

- Hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites for selective laser sintering: Thermal and mechanical performances

- Synthesis of a phosphoramidate flame retardant and its flame retardancy on cotton fabrics

- Preparation and characterization of thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymers with enhanced hydrophilicity

- Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process

- Silver-loaded carbon nanofibers for ammonia sensing

- Polar migration behavior of phosphonate groups in phosphonate esterified acrylic grafted epoxy ester composites and their role in substrate protection

- Solubility and diffusion coefficient of supercritical CO2 in polystyrene dynamic melt

- Curcumin-loaded polyvinyl butyral film with antibacterial activity

- Experimental-numerical studies of the effect of cell structure on the mechanical properties of polypropylene foams

- Experimental investigation on the three-dimensional flow field from a meltblowing slot die

- Enhancing tribo-mechanical properties and thermal stability of nylon 6 by hexagonal boron nitride fillers

- Preparation and characterization of electrospun fibrous scaffolds of either PVA or PVP for fast release of sildenafil citrate

- Seawater degradation of PLA accelerated by water-soluble PVA

- Review Article

- Mechanical properties and application analysis of spider silk bionic material

- Additive manufacturing of PLA-based scaffolds intended for bone regeneration and strategies to improve their biological properties

- Structural design toward functional materials by electrospinning: A review

- Special Issue: XXXII National Congress of the Mexican Polymer Society

- Tailoring the morphology of poly(high internal phase emulsions) synthesized by using deep eutectic solvents

- Modification of Ceiba pentandra cellulose for drug release applications

- Redox initiation in semicontinuous polymerization to search for specific mechanical properties of copolymers

- pH-responsive polymer micelles for methotrexate delivery at tumor microenvironments

- Microwave-assisted synthesis of the lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone and ω-pentadecanolactone: Thermal and FTIR characterization

- Rapid Communications

- Pilot-scale production of polylactic acid nanofibers by melt electrospinning

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Synthesis and characterization of new macromolecule systems for colon-specific drug delivery