Abstract

Electrospinning as one of the most versatile technologies have attracted a lot of scientists’ interests in past decades due to its great diversity of fabricating nanofibers featuring high aspect ratio, large specific surface area, flexibility, structural abundance, and surface functionality. Remarkable progress has been made in terms of the versatile structures of electrospun fibers and great functionalities to enable a broad spectrum of applications. In this article, the electrospun fibers with different structures and their applications are reviewed. First, several kinds of electrospun fibers with different structures are presented. Then the applications of various structural electrospun fibers in different fields, including catalysis, drug release, batteries, and supercapacitors, are reviewed. Finally, the application prospect and main challenges of electrospun fibers are discussed. We hope that this review will provide readers with a comprehensive understanding of the structural design and applications of electrospun fibers in different fields.

1 Introduction

Many techniques are used to fabricate fibers, including drawing (1), electrospinning (2,3,4), template synthesis (5,6), hydrothermal (7), in situ polymerization (8), self-assembly (9), mechanical method (10,11), melt spinning (12,13), etc. Among them, electrospinning has superior advantages of its simple operation, variety of materials capable of electrospinning, and short fabrication cycle (14,15,16). Electrospinning has become one of the main ways to fabricate successive micro- and nanofibers owing to the advantages of many types of spinnable materials, low spinning cost, and high controllability of process parameters (2,4,17). Electrospun fibers hold many advantages of their tiny fiber diameters, large specific areas, abundant pores, good mechanical properties, tunable structures, various adjustable properties, and low costs (18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25). By structural design with modifications on spinnerets and collectors, functional electrospun fibers with special structures Janus, core–shell, hollow, porous, helical, etc., are comprehensively investigated. Such functional electrospun fibers have been widely used in different fields, such as masks (26,27), stimuli-responsive materials and actuators (28,29,30,31), separation and filtration (32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39), reinforcements (40,41,42,43,44,45), wearable electronics (46,47,48,49,50), sponges/aerogels (51,52,53,54,55,56), tissue engineering (57,58), detection metal ions (59,60,61), energy storage (62,63,64,65,66), catalysts (67,68,69,70,71,72), drug release (73,74), food packaging (75,76,77), functional surfaces (78,79,80), biomedical and tissue engineering (81,82,83), sensors (84,85,86,87), and so on.

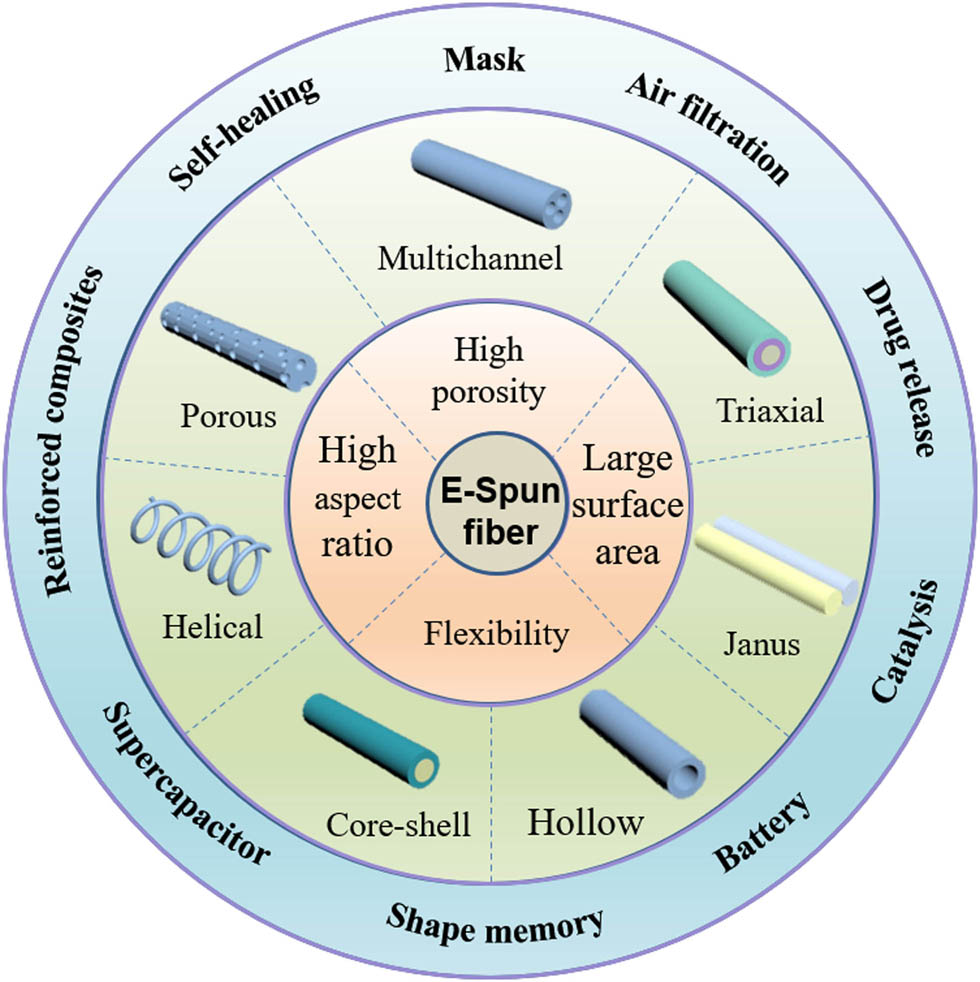

Although many reports are available on the preparation and application of electrospun fibers with special structures, the summary of the relations between the different structures and applications of electrospun fibers has not been reported. In this review article, Section 2 is about several kinds of electrospun fibers with different structures, including normal electrospun fibers, multichannel fibers, fibers with Janus, core–shell, hollow and triaxial structures; spiral/spring electrospun fibers, and porous electrospun fibers; and Section 3 discusses their applications in different fields, such as mask, air filtration, drug release, catalysis, battery, shape memory materials, supercapacitor, reinforcements, self-healing, etc., which are summarized as shown in Figure 1. Finally, Section 4 is on conclusion and perspectives of the current outcomes and challenges in this field.

The characteristics, structures, and applications of electrospun fibers with different structural design.

2 Different structures by electrospinning

Electrospinning is a universal technology for the preparation of continuous fibers with simple operation process. However, an urgent problem about electrospinning fiber is how to endow the electrospun fibers a great function just by tailoring to the structure of fibers. Therefore, in order to expand the application range of electrospun fibers, the researchers optimized and improved the electrospinning and obtained some electrospun fiber materials with different morphologies.

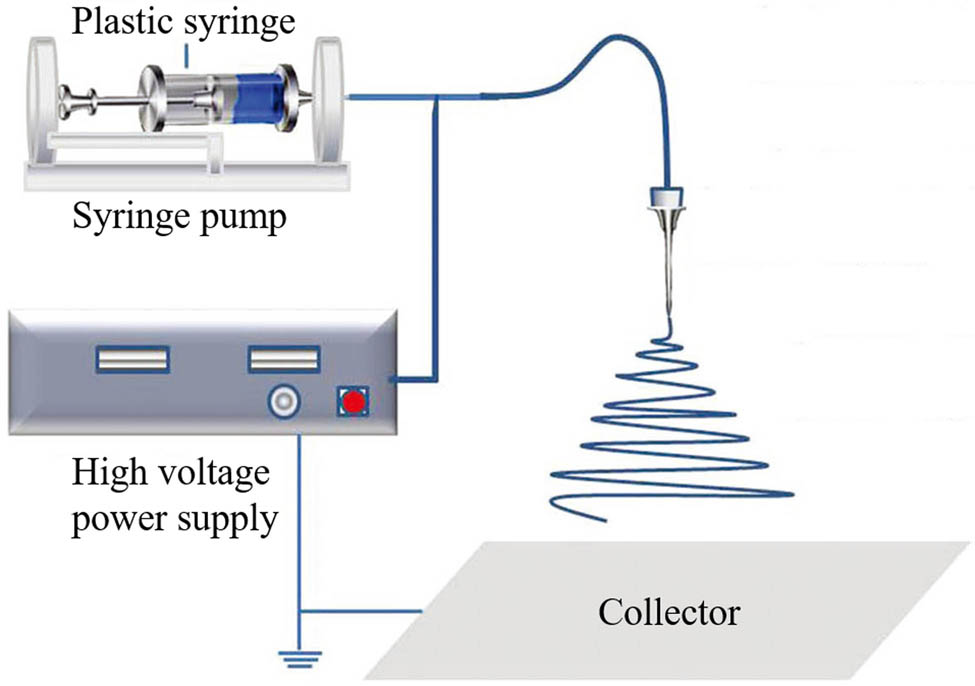

2.1 Normal electrospun fibers

Electrospinning can easily produce continuous fibers with diameters ranging from tens of nanometers to several microns. The traditional electrospinning device includes four main components including high-voltage power supply, syringe pump, plastic syringe, and collector with ground wires, as shown in Figure 2. Normal electrospun fibers can be obtained by different electrospinning. In 2001, electrospun fibers with uniaxial orientation were designed and reported (88,89). Martuzevicius’s group prepared a new polymer poly(ether-block-amide) fiber by melt electrospinning and solution electrospinning (90). In the past few decades, traditional electrospinning made significant progress and improvements, resulting in high productivity, desired structure, and appearances, which has prompted many companies to manufacture electrospun fibers with different functions for different fields.

Traditional electrospinning setup (91) (© 2016 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim).

The electrospun fiber materials with single function are generally obtained by using uniaxial electrospinning (92,93,94). Under the background that the single-function electrospun fiber material cannot meet people’s demand, the multifunction electrospun fiber material comes into being gradually (95,96,97). Chase et al. (98) fabricated ZnO/Al2O3 composite nanofibers with a diameter of 60–150 nm. Compared with the pure ZnO nanofibers, the ultraviolet absorption edge of composite nanofibers moved to a higher wavelength by doping Al2O3; while the absorption edge of composite nanofibers moved to a lower wavelength when the amount of Al is further increased. Furthermore, Guo et al. (99) successfully prepared water-soluble polyfluorene/Fe3O4/poly(vinyl alcohol) composite nanofibers with luminescent–electrical–magnetic properties. The composite nanofibers emit bright blue fluorescence under the excitation of ultraviolet light and exhibit excellent superparamagnetic properties. It is reported that the fluorescence properties of luminescent materials are seriously affected when they are mixed with dark substance. On this basis, Li et al. (100) prepared a double-layer composite fiber membrane. The design of the double-layer structure avoids the adverse effects of conductive and magnetic substances on luminescent substances. However, with the deepening of research, we realize that when magnetic substances are mixed with conductive substances, the magnetic particles will affect the continuity of conductive molecular chains of conductive polymers (101,102,103), thus affecting the conductivity of materials. How to design a special structure to avoid the adverse effects when different substances are mixed has become one of the hot spots, which will also be discussed in the following parts.

2.2 Spring/helical electrospun fibers

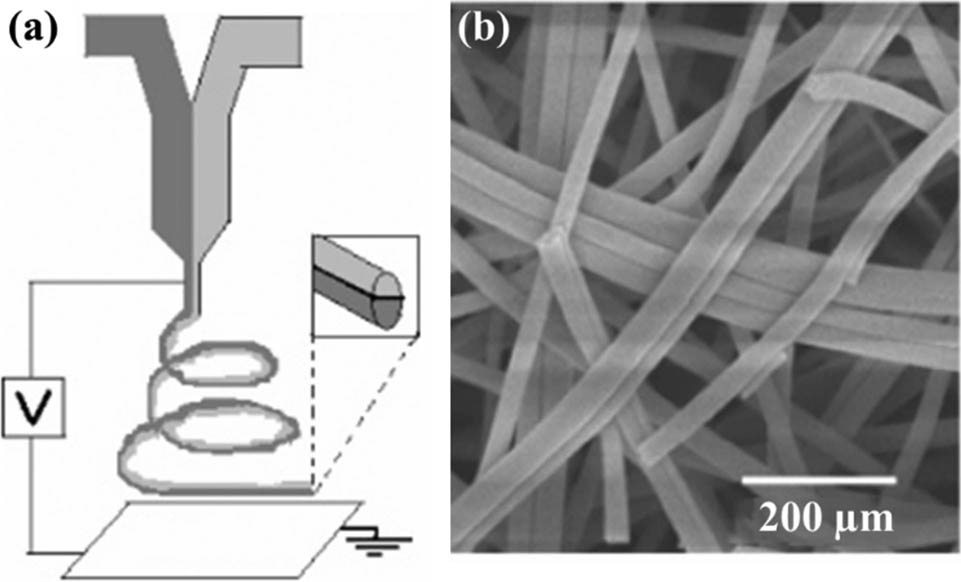

Compared to the normal electrospun fibers, the helical structures generally exist at the micro and macro levels. For example, the double-helical DNA structure ensures the most effective packaging, availability, and fidelity of information stored in macromolecules (104). The tendrils of climbers are attached to the surrounding objects, which can not only help the plants grow upward but also provide them with a support to adapt to changing weather conditions (105). These natural spiral structures have inspired researchers. A large number of different types of artificial spiral structures have been reported for use in tissue engineering (106), bionic materials (107), sensors (108), shape memory materials (109) and other fields. Kessick and Tepper (110) prepared spiral electrospun fiber composite on a conductive substrate using a conductive and a nonconductive polymer. They found that the positive charge carried by the conductive phase in the fiber was neutralized by negative charge carried by the substrate, thus causing the conductive phase to contract and form helical fiber. Wang et al. (111) prepared unidirectional helix fibers with non-conductive polymers and believed that the physical forces, due to the bending instability of the jet, played an important role in the formation of helix fibers. Xin et al. (112) prepared a composite spiral structure composed of two kinds of polymers. They claimed that the viscosity and electrical conductivity of electrospun fibers, as well as its operating voltage, were the main factors affecting the spring electrospun fibers. Godinho et al. summarized the mechanism of spring electrospun fiber formation and pointed out that the electrospinning fiber or jet impinges on the substrate surface, causing mechanical instability that drives the electrospun fiber along the fiber path as it falls onto the substrate, thus leading to the formation of the spring fiber (105).

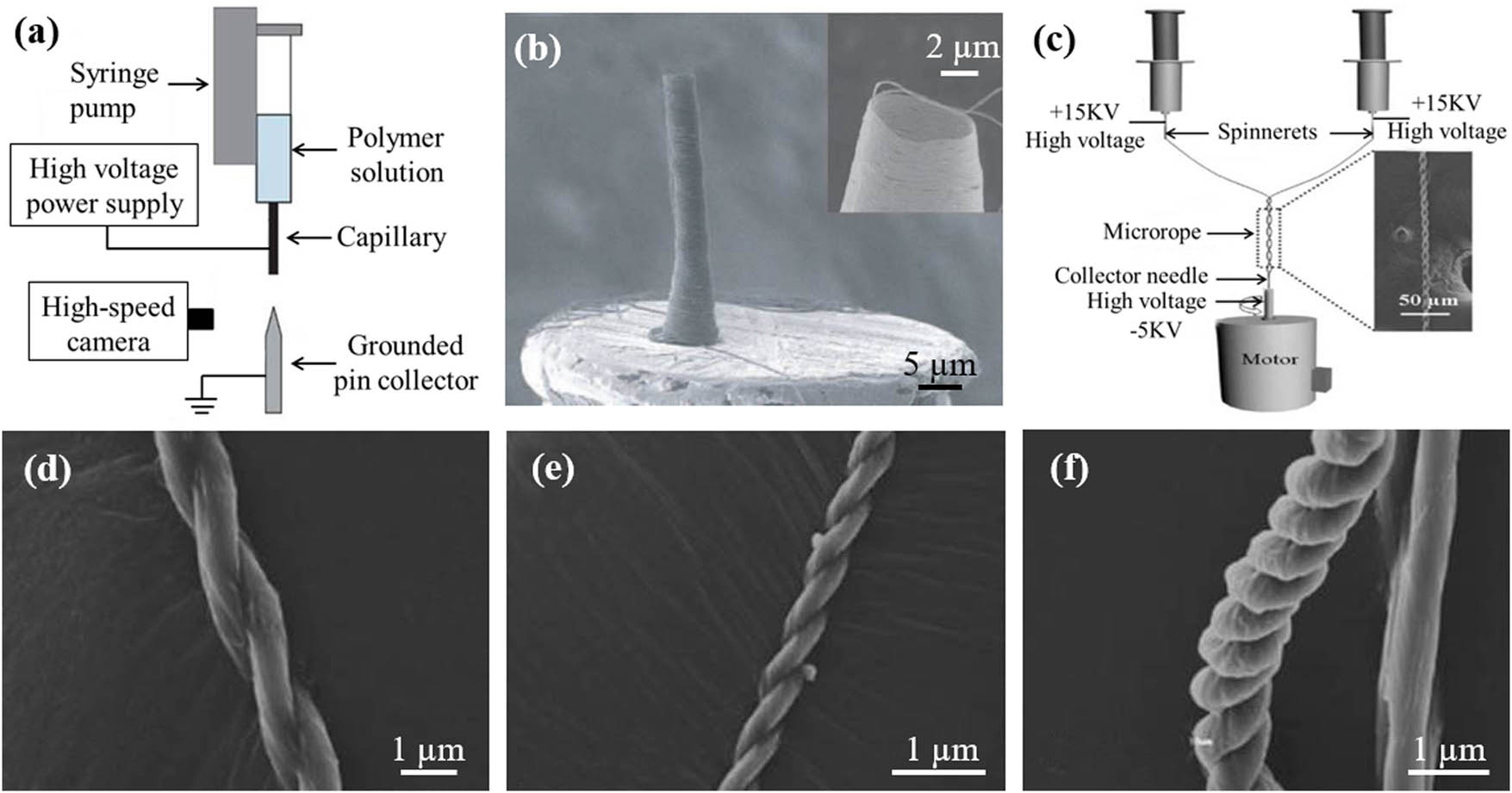

Currently, with the improvement in electrospinning, the methods for constructing spiral electrospun fibers are mainly divided into the following three types: (1) forming a spiral structure by hitting the collector (113,114), (2) mechanically twisting the electrospun fiber to obtain a helical structure (115,116), and (3) using electrospun jet, spinning solution, or electrospun, the nature of the electrospun fiber itself obtains a spiral structure (117,118,119).

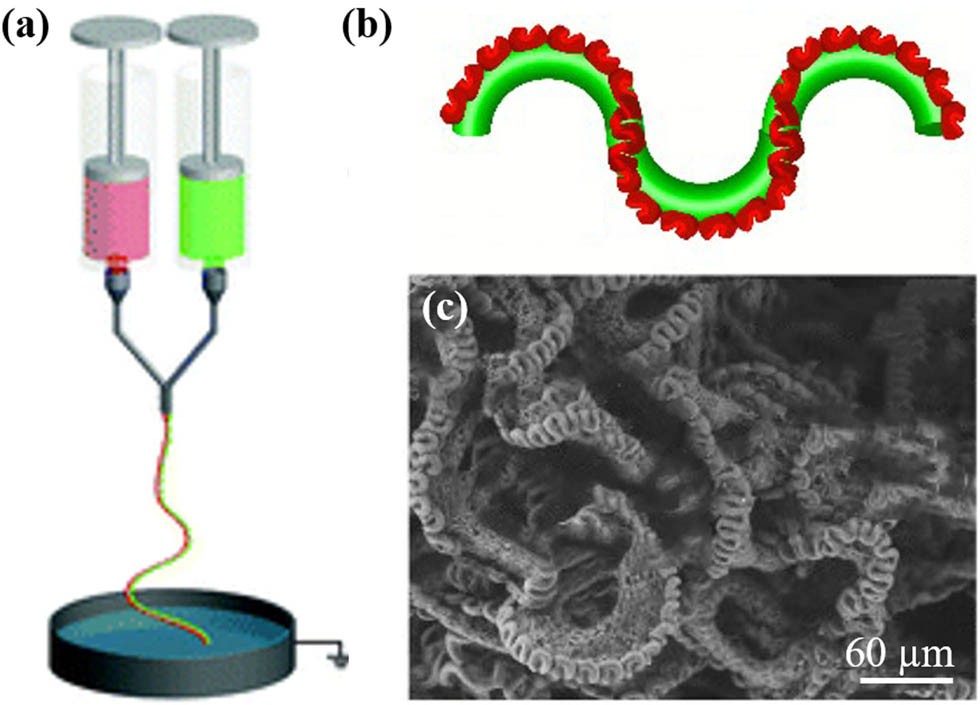

Kim et al. (114) designed a different strategy, using a strong focusing field to fold and stack fibers on a regular cylindrical spool at the top of the metal tip, as shown in Figure 3a. The jet is already solid and can be modeled as a thin elastic filament when the polymer drops to the grounded tip. The obtained fibers had typical diameters of 200 nm and coil radius ranging from 1 to 8 µm. Chang et al. (116) prepared a double-helical micro-rope by using bi-electrospinning, as shown in Figure 3c. Two high-voltage power supplies for providing positive high voltage are connected with two spinnerets, and a copper needle fixed upright on a motor serves as a receiver. The spiral structure is formed mainly from the traction during the rotation of the collecting device. Additionally, the spiral degree of micron rope can be controlled by adjusting the distance between the two spinneret heads, as shown in Figure 3d–f.

Su et al. (120) prepared polyethene oxide/polylactic acid (PEO/PCL) helical electrospun fibers with Janus structure and controllable morphology by using parallel-axis wet electrospinning, as shown in Figure 4a. Figure 4b shows a schematic diagram of a fiber with a spiral structure, and the helical structure can be clearly seen in Figure 4c. The electrospun fibers have potential applications prospects in the field of bionic materials. The helical structure can support the adhesion and growth of endothelial cells on PCL micro-disk side and realize Janus cell pattern. Compared with normal electrospun PEO/PCL fiber, helical PEO/PCL electrospun fibers demonstrate good mechanical properties, porosity, and rapid water absorption capacity. The potential of this multispiral twisted tendril involves a biomaterial of 3D-Janus cell model.

(a) Electrospinning device, (b) the morphology of multihelix-perversion microfiber, and (c) SEM image of PEO/PCL fibers (120) (© The Royal Society of Chemistry 2020).

In recent years, micro/nano devices with helical structure have developed rapidly (105). Although there are many reported preparation methods and formation mechanisms for spring micro/nano structures directly prepared by electrospinning, there are only few related reports on the functionalization of spiral micro/nano structures directly from electrospinning (112). Therefore, this kind of electrospun fiber still deserves to be explored because of its unique structure and mechanical properties.

2.3 Porous electrospun fibers

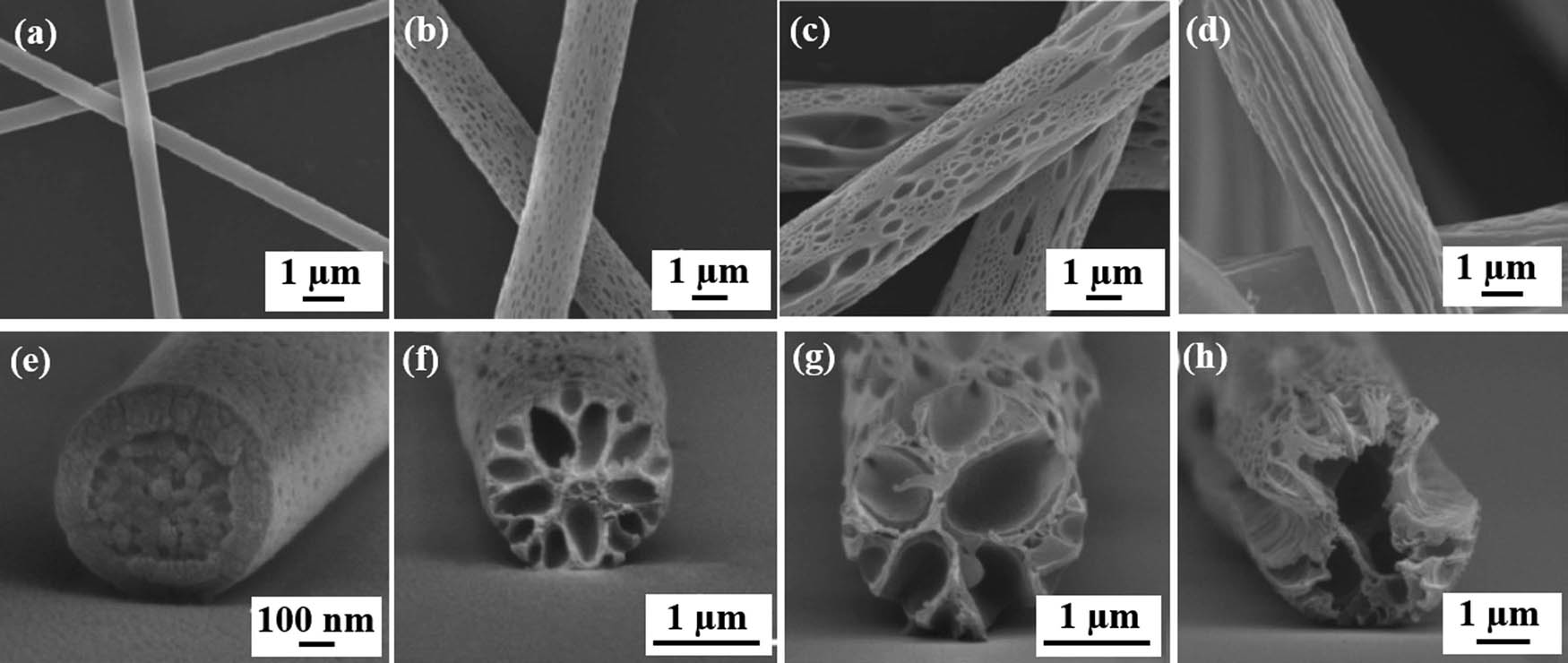

Electrospun fiber materials have been widely used in biomedicine, flexible electronic devices, electronic skin, etc., due to its great versatility. In spite of this, higher requirements are put forward for the application of electrospun fibers materials, regarding how to obtain better performance and higher specific surface area. Porous fiber came into being under this requirement. Although spring electrospun fibers have high porosity, the electrospinning process of spring electrospun fibers is not easily controlled. Besides, compared with the normal electrospun fiber, porous electrospun fiber can also be regarded as the optimization of and improvement in the conventional electrospun fiber. The porous electrospun fiber possesses higher porosity and specific surface area, which broadens the application of the fiber material in various fields. The preparation methods of porous fibers mainly include solvent/hydrothermal method, sol–gel method, template method, electrospinning, etc. Among them, one-step and multistep electrospinning are usually applied for the preparation of micro- andnanoporous electrospun fibers. One-step electrospinning often requires polymers dissolving in high-volatile solvent. During the electrospinning process, the rapid volatilization of the solvent results in phase separation, and the solvent enrichment phase and polymer enrichment phase are formed. The polymer enrichment phase is cured in the air and finally the fiber skeleton is formed; while in the solvent enrichment phase, the channel of the fiber is formed. By controlling the solubility of polymers in a mixture solvent, the pore structures can be tailored by one-step electrospinning. For example, Chen et al. (121) dissolved polystyrene (PS) in a mixed solution composed of excellent solvent chlorobenzene and nonsolvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and successfully prepared nonsolvent-induced PS fibers with ultrahigh oil absorption capacity by one-step electrospinning using uniaxial spinneret. A highly porous structure is produced during drying due to the separation of low-volatile nonsolvent phases in the fiber. In addition, the effect of the nonsolvent DMSO on the porosity of fiber was discussed. The results show that with an increase in the DMSO content, the pore size increased, indicating that nonsolvent played an important role in the formation of pores, as displayed in Figure 5.

The SEM images of the surfaces and the cross sections of PS fibers fabricated from solutions with varying DMSO content: (a and e) 0%, (b and f) 20%, (c and g) 30%, and (d and h) 40% (121) (© American Chemical Society 2017).

Analogously, the combination of electrospinning and calcining method can also obtain porous fiber materials. First, different precursor fibers can be produced by electrospinning and then the precursor fibers are carbonized, which is usually accompanied by the release of large amounts of gases (such as CO2, H2O, NOx, etc.) that porous structures inside the carbon fibers were formed. Wang et al. (122) successfully prepared porous carbon nanofibers (CNFs) embedded with CO2O3 nanoparticles (NPs) using coaxial electrospinning. With polyacrylonitrile (PAN) as the carbon-based material, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O/N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) as the core layer, and cobalt nitrate/DMF as the shell layer, the precursor electrospun fiber was prepared under the conditions of adjusting voltage of 17 kV, spinning distance of 20 cm, and flow rate of 26 L min−1. Then the precursor fiber was preoxidized under air condition and carbonized under N2. During carbonization, zinc precursor evaporates from the inside out to form a stable pore frame structure inside the carbon fiber. Finally, the porous CNFs are washed with hydrochloric acid and deionized water. Simultaneously, the porosity of the fiber can be controlled by changing the amount of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, as illustrated in Figure 6. The obtained porous CNFs possessed hierarchical porous structures and high specific surface area (123).

(a) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of porous carbon nanofibers, (b) SEM image, and (c) pore size distribution curves of porous fibers (122) (© 2017 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved).

2.4 Core–shell electrospun fibers

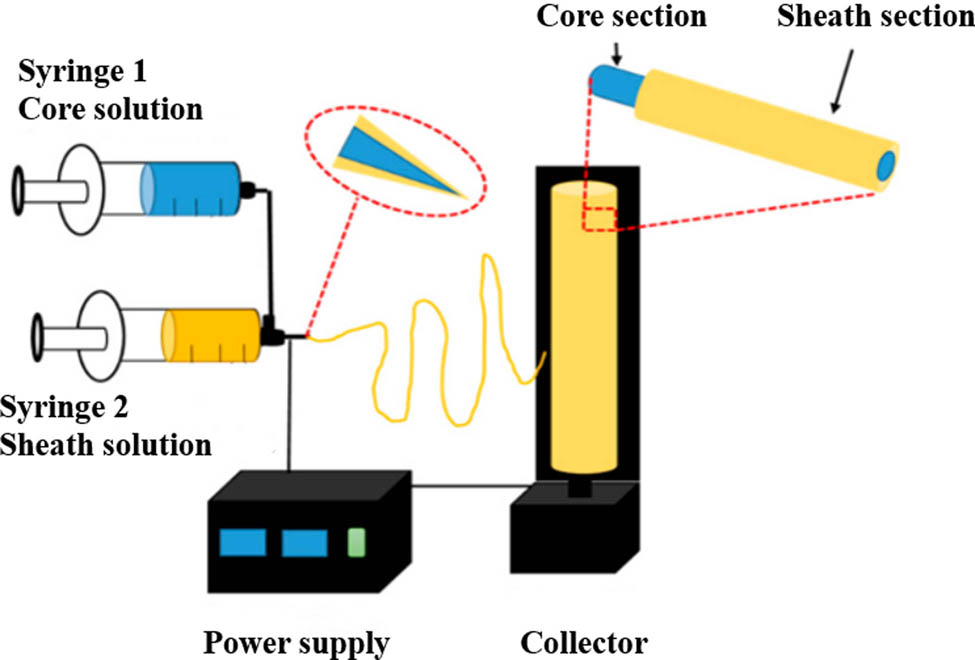

Compared with normal electrospun fibers, core–shell nanofibers allow many nonspinnable polymers to be used as electrospinnable materials. Meanwhile, the core–shell electrospun fiber can effectively solve the problem of mutual adverse effects caused by the mixing of different energy-supplying materials. Electrospun fiber with core–shell structure can be prepared by a variety of methods, such as multistep template synthesis, chemical deposition, and coaxial electrospinning. In 2007, Bazilevsky et al. (124) prepared the core–shell polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)/polyacrylonitrile (PAN) fibers with an outer diameter of 0.5–5.0 µm by combining uniaxial electrospinning and coating deposition, which have core–shell structure similar to the ones obtained from coaxial electrospinning. Although the core–shell structure is created by general electrospinning followed by post-processing, the thickness of the resulting fibers is difficult to be controlled. Fortunately, coaxial electrospinning offers a facile way to fabricate core–shell nanofibers with a controlled shell thickness just by tuning the feeding rate. It can not only provide fiber materials with coaxial structure more quickly and conveniently but also achieve the transformation of nanofibers from a single component to a complex multilayer structure (125). Generally, during the fabrication of coaxial electrospun fibers, a coaxial spinneret is applied, through which two different kinds of functional solutions form the core and shell parts, respectively. It allows the coaxial electrospun fibers to wrap the functional agents in the core, maintaining its activity while keeping a close contact with the shell without weakening the core function. Therefore, coaxial electrospinning has been considered as one of the most important methods to fabricate continuous nanofibers with core–shell structure, as shown in Figure 7 (126). In addition, Zhang et al. successfully prepared coaxial electrospinning fibers by emulsion electrospinning, and this method provides a new idea for the preparation of core–shell electrospun fibers (127).

Schematic diagram of coaxial electrospinning (126) (Open access).

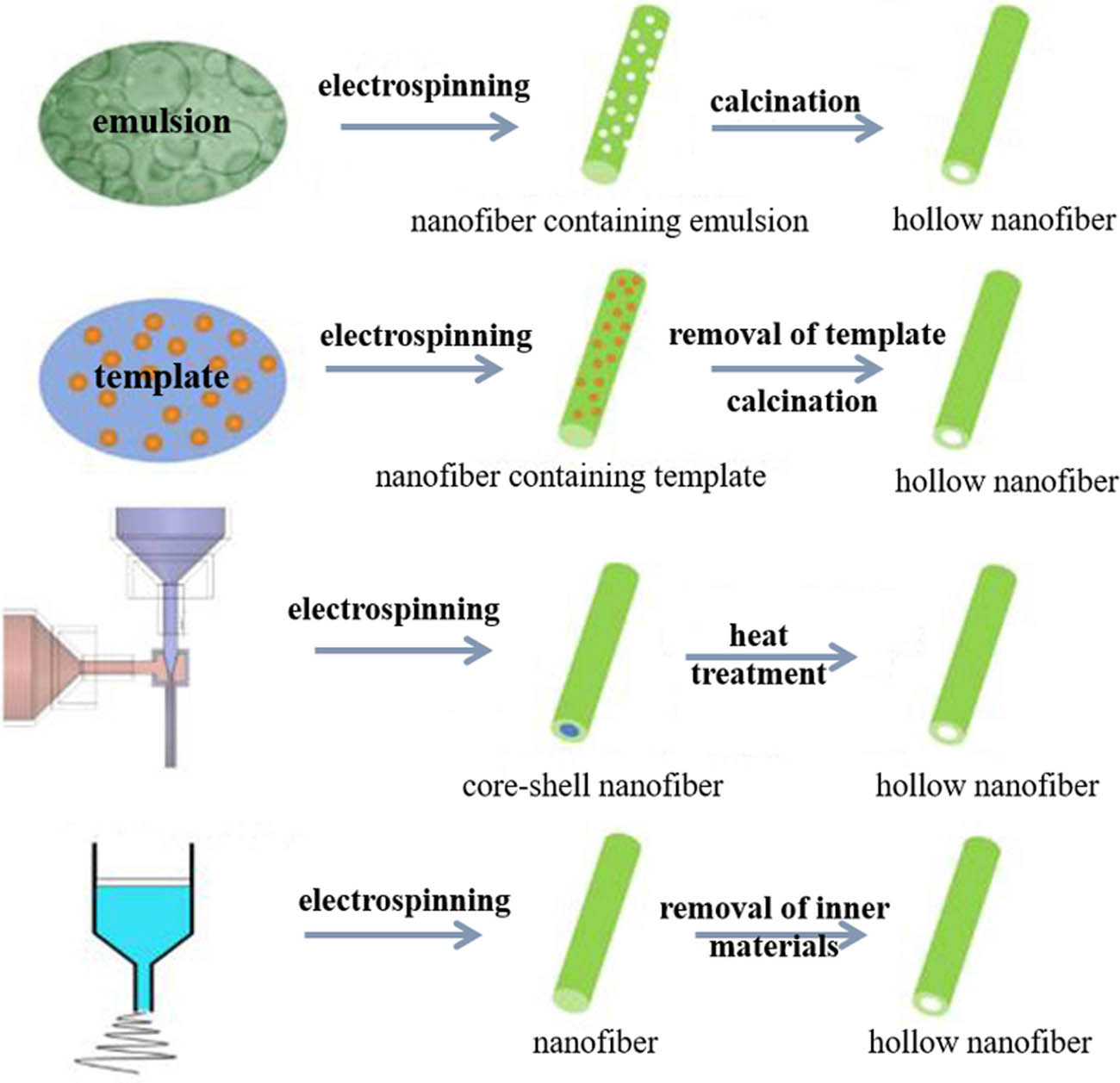

2.5 Hollow electrospun fibers

Hollow fibers have attracted extensive attention from academia and industry due to their large specific surface area, high porosity and strong permeability. They have some similarities with core–shell electrospun fiber in structure and can be regarded as core–shell electrospun fiber with core removed. Therefore, coaxial electrospinning has been considered to be one of the most popular methods for fabricating hollow electrospun fiber, which can selectively remove the core component. Nanofibers with core–shell structure can be prepared by using special coaxial spinneret with different precursor solutions in inner and outer layers. Four main methods are involved in preparing hollow electrospun fiber, as shown in Figure 8. The first method is the emulsion electrospinning (127,128). The second method consists of introducing a hard template into the spinning solution to obtain hollow electrospun fibers (129). Inspired by the spawning process of toads, Yin et al. (129) introduced spherical SiO2 with a diameter of about 180 nm into PAN spinning solution. Then the electrospun fibers are preoxidized and carbonized, followed by the removal of the silicon template with hydrofluoric acid to obtain carbon fibers with a large number of hollow spherical holes.

Four common methods for preparing hollow nanofibers (130) (Copyright © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved).

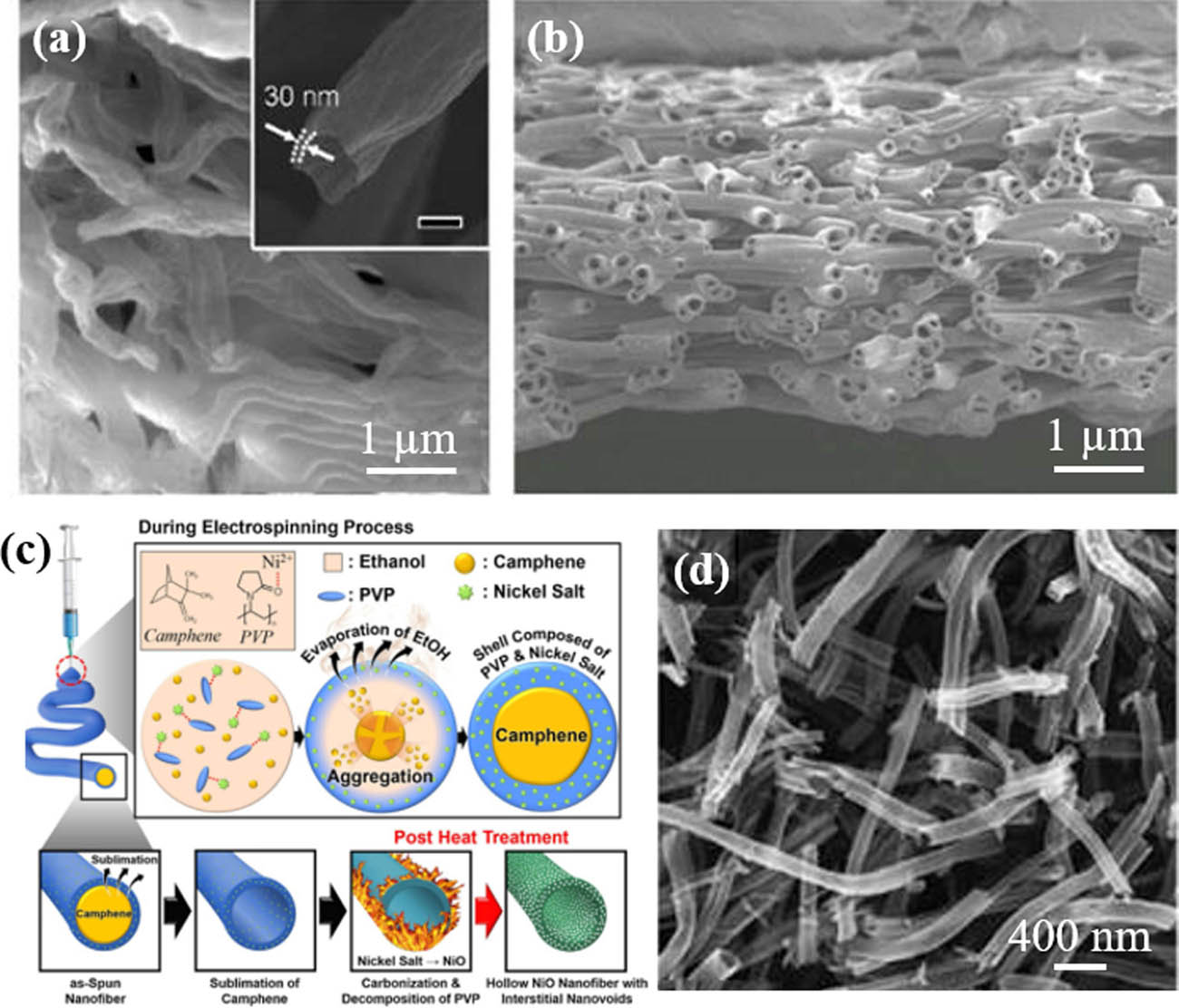

The third method is to use coaxial electrospinning to prepare electrospun fiber precursor with core–shell structure and then the precursor electrospun fibers were calcined at high temperature, which can also result in the hollow structure fiber (131). Dai et al. (132) reported a one-pot direct electrospinning, using coaxial electrospinning to prepare hollow nanofibers. During spinning, hollow Taylor cones are formed at the bottom of plastic nozzles to obtain hollow electrospinning fibers. The morphology and size (diameter, inner diameter, wall thickness, etc.) of hollow electrospun fibers can be controlled by changing the electrospinning parameters and subsequent treatments such as calcination and cladding. The size varies from tens of nanometers to hundreds of nanometers. The obvious hollow structure is obtained when the calcining temperature reaches 900°C, as shown in Figure 9a, and the wall thickness of hollow structure is about 30 nm. Meanwhile, the size of the fiber increases from about 40 to about 440 nm with an increase in the calcination temperature. The cross-section morphology of polyurethane (PU) hollow nanofibers is presented by SEM image, as shown in Figure 9b. Besides, Tie et al. (133) used NPs as materials, assembled the Pr-doped double Fe2O3 hollow nanofibers by electrospinning and calcination, modified them with ions, and improved the structure of hollow nanofibers. The Pr-doped BiFeO3 hollow nanofibers have uniform tubular structure, whose surface area and pore diameter are, respectively, 63.53 m2 g−1 and 38.17 nm. Oh et al. (134) prepared NiO hollow nanofibers by calcination of precursor fibers. The formation mechanism and SEM image of NiO hollow nanofibers are, respectively, shown in Figure 9c and d. NiO nanofibers with hollow structure have high structural stability, shortened the diffusion path of Li+ ions in the cycling process, and good Li+ ion storage performance. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) of hollow NiO nanofibers is 61 m2 g−1. In general, the difficulty of this preparation method lies in the fact that it is necessary to control the viscosity and flow rate of two spinning fluids simultaneously in order to obtain a large number of high-quality coaxial fibers by coaxial electrospinning.

The SEM images of composite nanofibers calcined at (a) 900°C for 2 h in air and (b) cross-sectional SEM image of PU hollow nanofibers (132) (© American Chemical Society 2017); (c) the formation mechanism and (d) SEM image of NiO hollow nanofibers (134) (Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved).

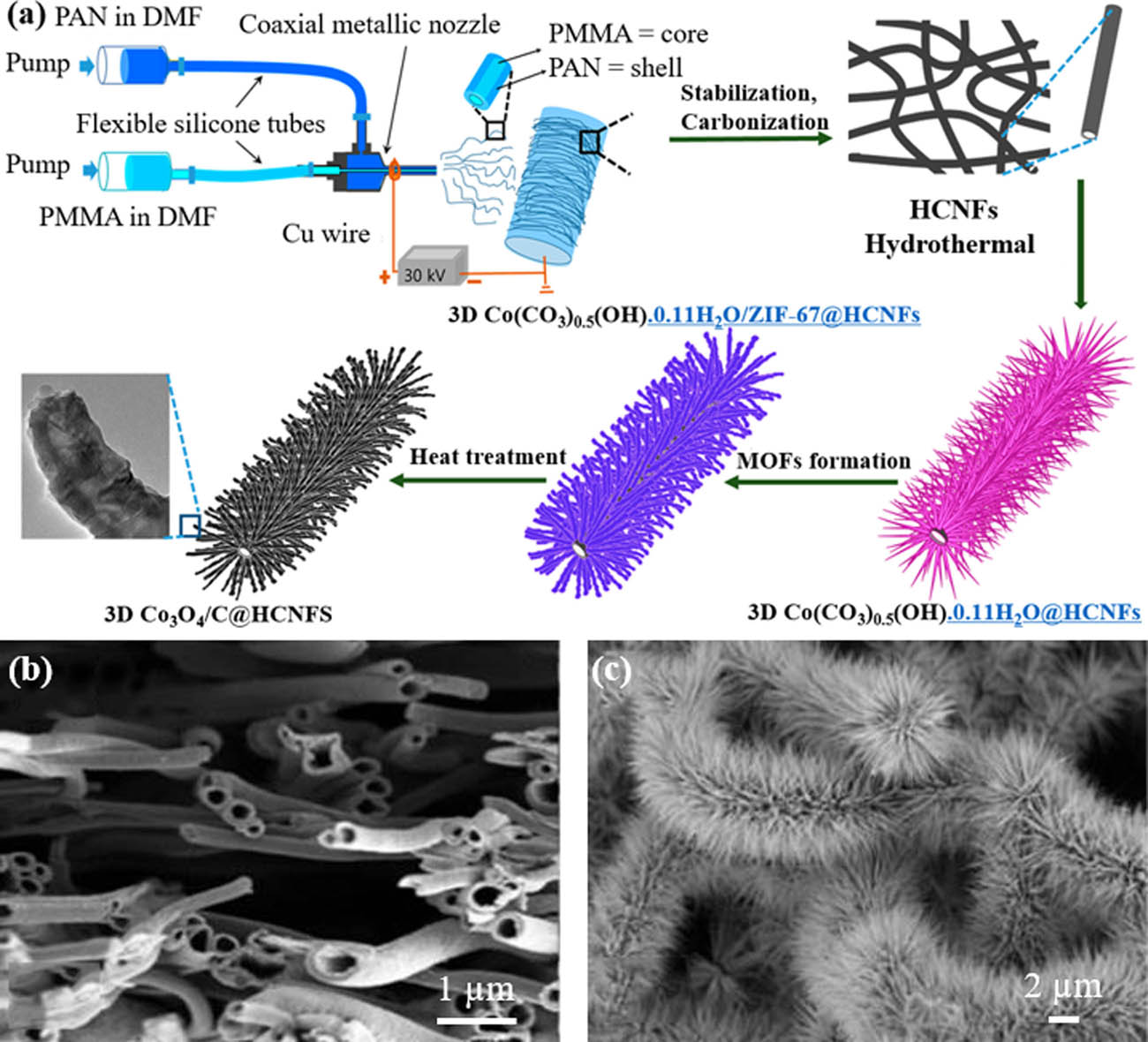

Another interesting work for the functional hollow electrospun composite fibers was reported by Mukhiya et al. (131). They used coaxial electrospinning and hydrothermal methods to prepare hollow Co3O4 with three-dimensional (3D) structure (Figure 10). PMMA and PAN were used as template agents for core layer and shell layer, respectively. After the one-step carbonization, hollow CNFs were formed and then Co3O4 was grown on the surface by hydrothermal method. Finally, 3D CO3O4 with special structure was obtained by heat treatment (Figure 10a). The obtained 3D CO3O4/C@HCNFS possesseds good hollow structure and porosity, with a high specific surface area (Figure 10b and c).

(a) Diagram of electrospinning apparatus for preparing 3D Co3O4/C@HCNFS hollow fiber and SEM images of (b) 3D Co3O4/C@HCNFS and (c) 3D Co(CO3)0.5(OH)·0.11H2O@HCNFs (134) (© American Chemical Society 2020).

The last one is to prepare precursor electrospinning fibers by traditional single-axis electrospinning and then obtain hollow fibers after calcination at high temperature. Li et al. (135) reported Y2O3:Yb3+/Er3+ hollow nanofibers by calcining composite nanofibers. During calcination process, the polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) chain was broken and volatilized. With the increase in calcination temperature, nitrates were decomposed and oxidized to NO2; Y3+, Yb3+, and Er3+ were oxidized to form Y2O3:Yb3+/Er3+ crystallites and then hollow Y2O3:Yb3+/Er3+ nanofibers were obtained.

2.6 Janus electrospun fibers

Janus structural materials are favored by researchers because of their special structure. In fact, a large number of studies have reported Janus structural system of materials; the preparation of Janus structure methods mainly include self-assembly, phase separation, electrospinning (136,137), etc. The reported materials of Janus structure mainly include Janus particles, snow-shaped Janus materials, dumbbell-shaped Janus materials, Janus nanowires, Janus nanocages, Janus fibers (136,137,138,139), etc.

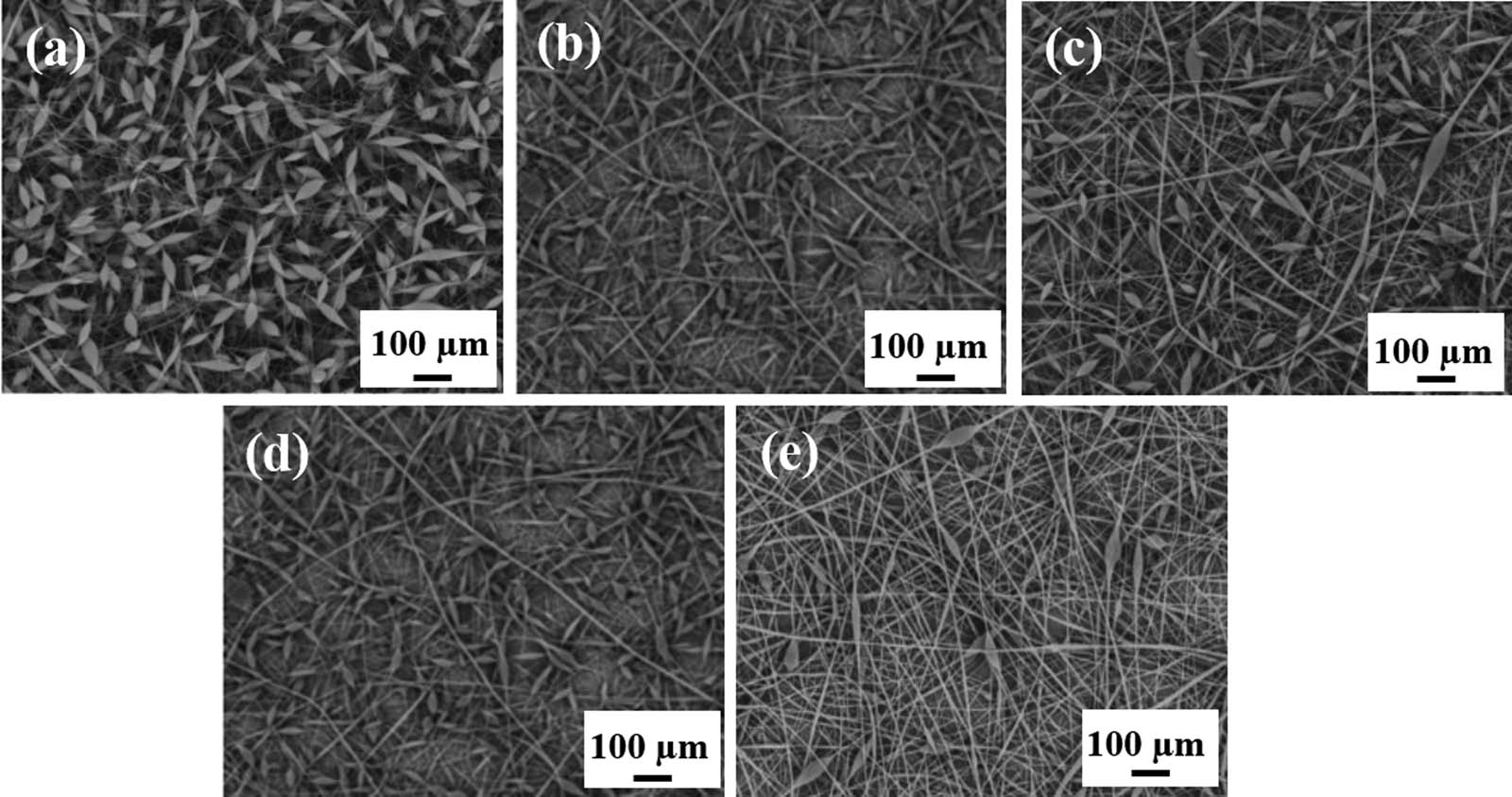

Inspired by Janus structure, Liu et al. (140) successfully prepared bicomponent TiO2/SnO2 nanofiber photocatalyst by combining parallel electrospinning with side-by-side double spinneret and high-temperature calcination. The electrospinning device of Janus electrospun fiber and SEM image of TiO2/SnO2 nanofiber is displayed in Figure 11. On the surface of the fiber, TiO2 and SnO2 of Janus structure were exposed simultaneously. Janus structure enables both photoelectron and holes to participate in the whole photocatalytic reaction system and improves the catalytic efficiency of photocatalyst. In addition, researchers use electrospinning solutions with different functions to obtain the materials with different functions. Pan’s group used parallel spinneret to prepare Janus nanofibers and endowed them with luminescence–magnetism bifunction (141).

(a) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup used for electrospinning bicomponent nanofibers with side-by-side dual spinnerets and (b) SEM images of TiO2/SnO2 nanofibers calcined at 500°C (140) (© American Chemical Society 2007).

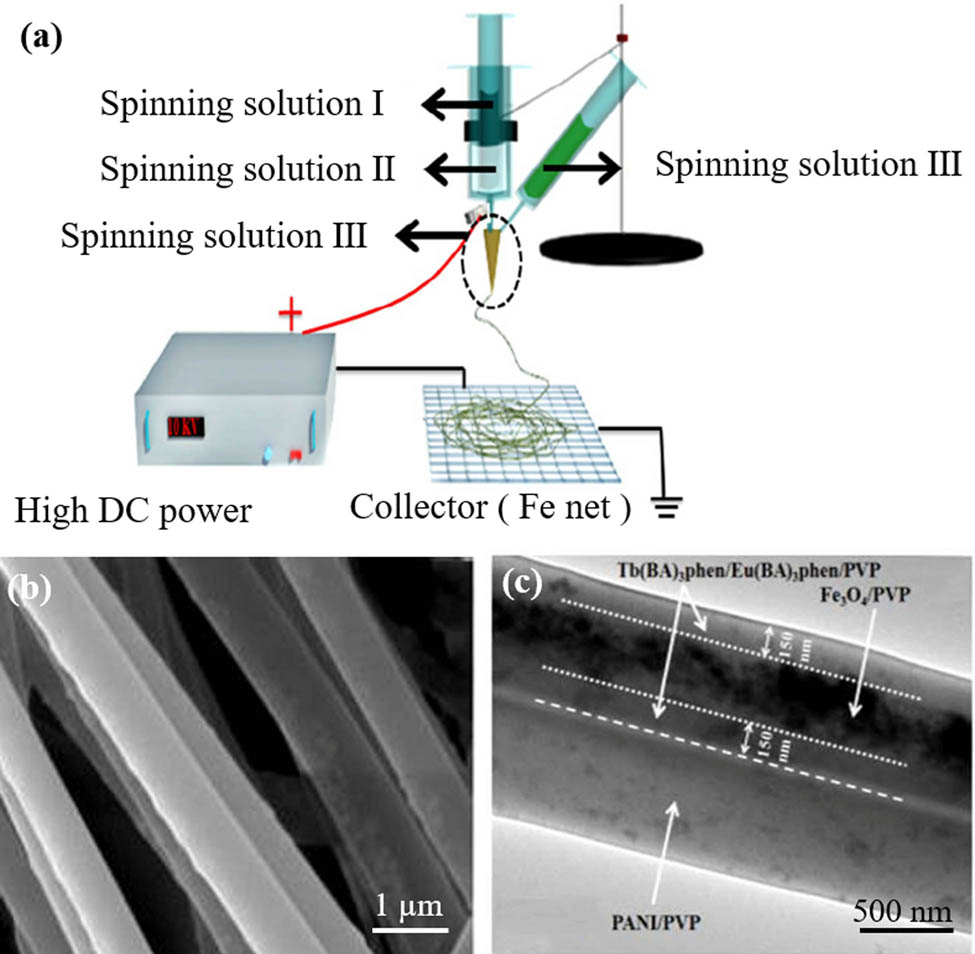

In addition, Xi et al. (142) improved the parallel electrospinning and successfully prepared Janus nanofiber with coaxial nanofiber/nanofiber structure by using the self-assembly coaxial/uniaxial spinneret, as manifested in Figure 12. This special Janus nanofiber is used as building unit to solve the problem of the adverse effects due to the mixing of substances of different functions.

(a) Electrospinning apparatus for preparing special Janus nanofibers, (b) SEM, and (c) TEM images of Janus nanofiber with coaxial/nanofiber structure (142) (© Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 2018).

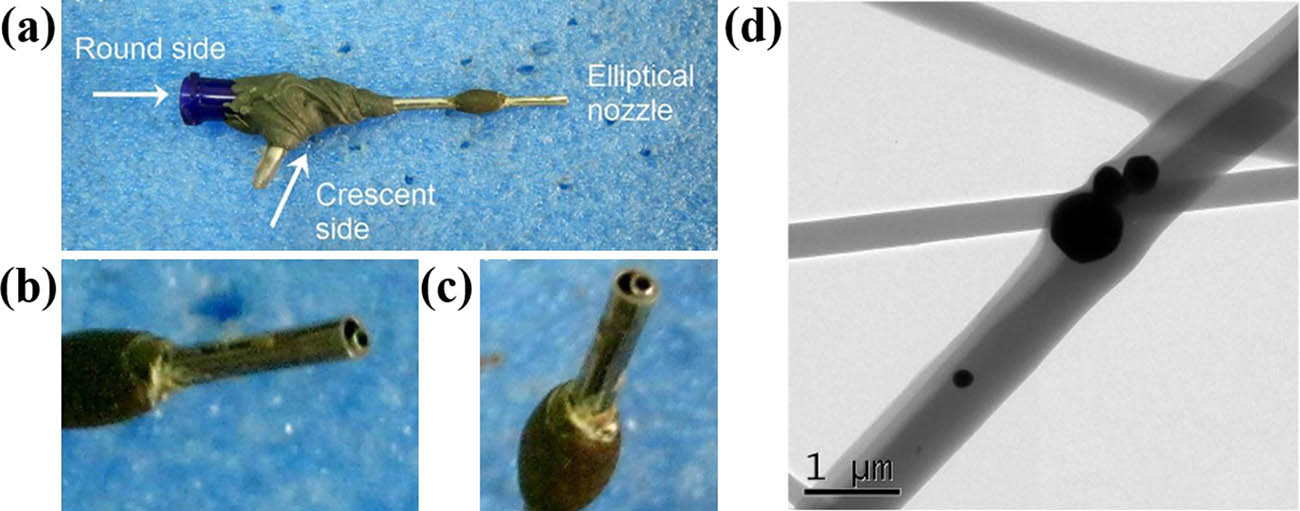

In another very recent report, Yang et al. (143) reported the successful preparation of PVP-ciprofloxacin (CIP)/ethyl cellulose (EC)-silver nanoparticles (AGNPs) composite Janus fiber window dressing with uniform structure by parallel electrospinning using a self-assembly acentric spinneret and structured spinnerets, respectively (Figure 13a–d), and Janus nanofiber was applied in vitro experiments (143). In addition, the prepared Janus fibers, loaded with ciprofloxacin, have stronger antibacterial properties against the growth of both Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative E. coli, compared to other fiber materials, due to their rapid drug release profile that 90% of ciprofloxacin in the first 30 min (143).

A digital picture of the acentric side-by-side spinneret: (a–c) was taken from different angles; (d) TEM image of the Janus fibers co-loaded with CIP and AgNPs (143) (© 2020 Elsevier B.V.).

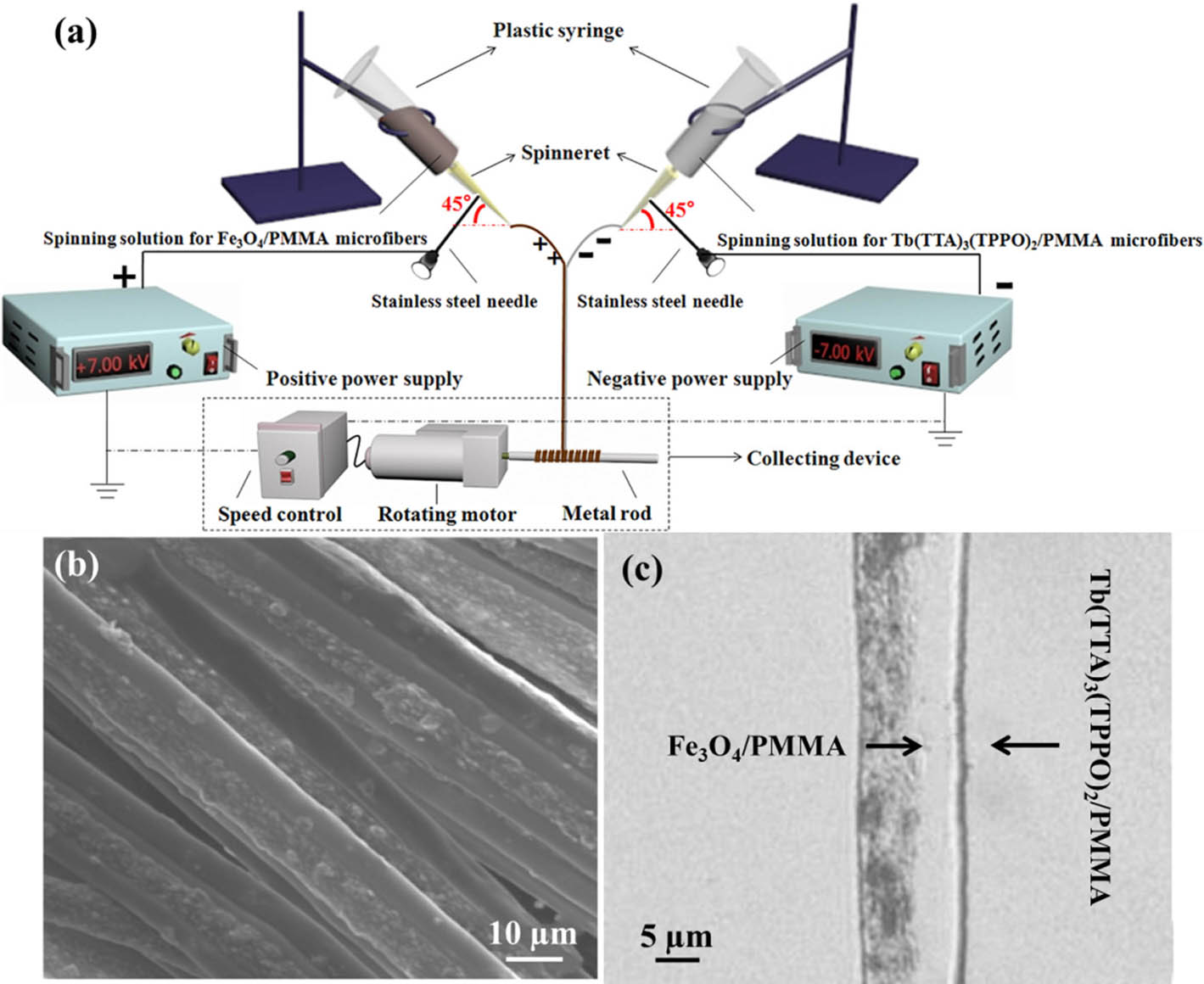

Janus fibers can be prepared not only by parallel electrospinning but also by conjugated electrospinning. Tian et al. (144) used conjugated electrospinning to prepare Janus microfiber and also used parallel electrospinning to prepare Janus micron fiber with three functions of fluorescence, conduction and magnetism (Figure 14). Simultaneously, the differences between conjugated electrospinning and parallel electrospinning in the preparation of Janus fiber materials are compared as well (144). By comparison, it is found that the parallel rate of Janus nanofibers obtained by using conjugated electrospinning is higher than that of parallel electrospinning, and the mixing of materials with different functions is completely avoided in the preparation process, thus fundamentally solving the adverse effects caused by the mixing of materials with different functions.

(a) Conjugated electrospinning apparatus for preparing Janus microfiber, (b) SEM image, and (c) optical microscope photograph of Janus microfiber (144) (Open access).

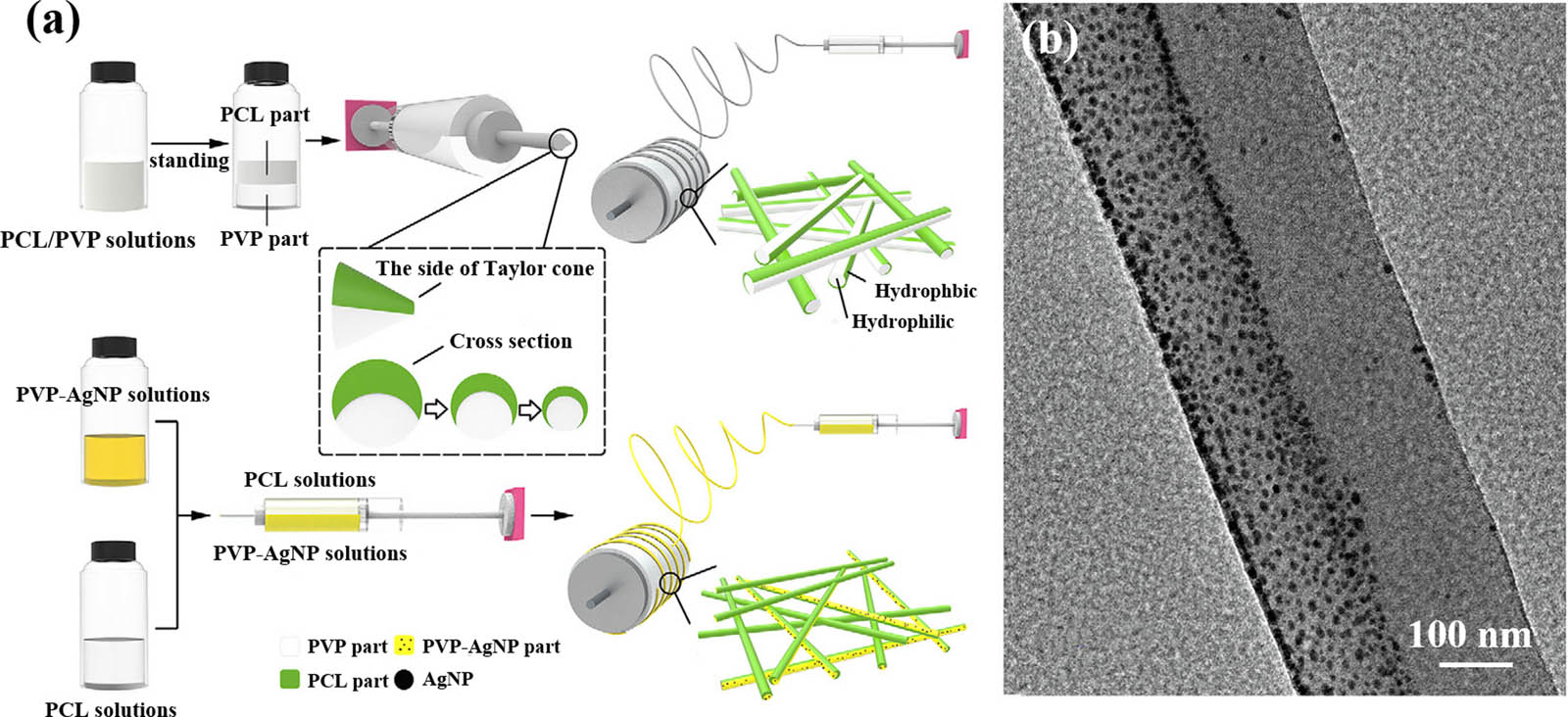

Yu et al. (145) prepared high-quality PVP/shellac Janus nanofibers using a three-fluid electrospinning technique with structured spinnerets with two eccentric needles in a third metal capillary. The design of this particular Janus electrospun fiber provides a better contact area between two different polymer solutions and indirectly reduces the repulsive force between the two fluids, resulting in high-quality Janus nanofibers. The above two electrospinning techniques are a well-known method for preparing Janus nanofibers. Recently, Li et al. (146) reported that PCL/PVP-AgNP Janus nanofibers with hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity were successfully prepared by uniaxial electrospinning using phase separation in solution. The schematic diagram of the preparation of PCL/PVP-AgNP Janus nanofibers is revealed in Figure 15a. When the mass ratio of PCL and PVP is 1:1, the morphology of the obtained Janus fibers is optimal. Obvious Janus structures can be observed from Figure 15b. This provides a new technique for the preparation of Janus fiber materials.

(a) Schematic diagram of preparation process and (b) SEM image of PCL/PVP-AgNP Janus nanofibers (146) (© 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved).

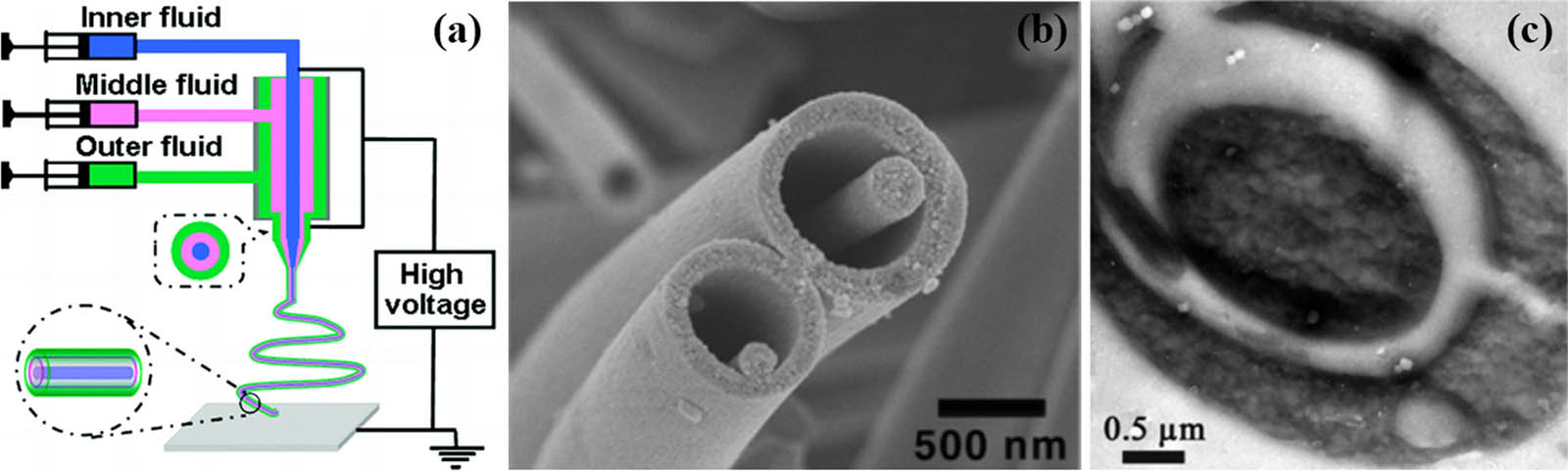

2.7 Triaxial electrospun fibers

Triaxial electrospinning can be considered as a further optimization of coaxial electrospinning. Currently, two main types of spinnerets used for three-axis electrospinning are the following: (I) three-component spinnerets and (II) concentric spinnerets using three independent syringes. Three independent channels of nanofibers can be obtained from the former spinneret, and core–shell–shell nanofibers can be obtained from the latter. Schematic diagram of triaxial electrospinning is displayed in Figure 16a (147). With the removal of the middle component, a fiber in-tube structure could be obtained by triaxial electrospinning (Figure 16b) (147). In another report, Jiang et al. applied triaxial electrospinning to prepare polystyrene (PS)/thermoplastic PU (TPU)/PS triaxial fiber with great enhancement of mechanical properties of PS, especially the toughness (148). The trilayer structure from components of PS and TPU could be clearly observed in the TEM image (Figure 16c).

2.8 Others

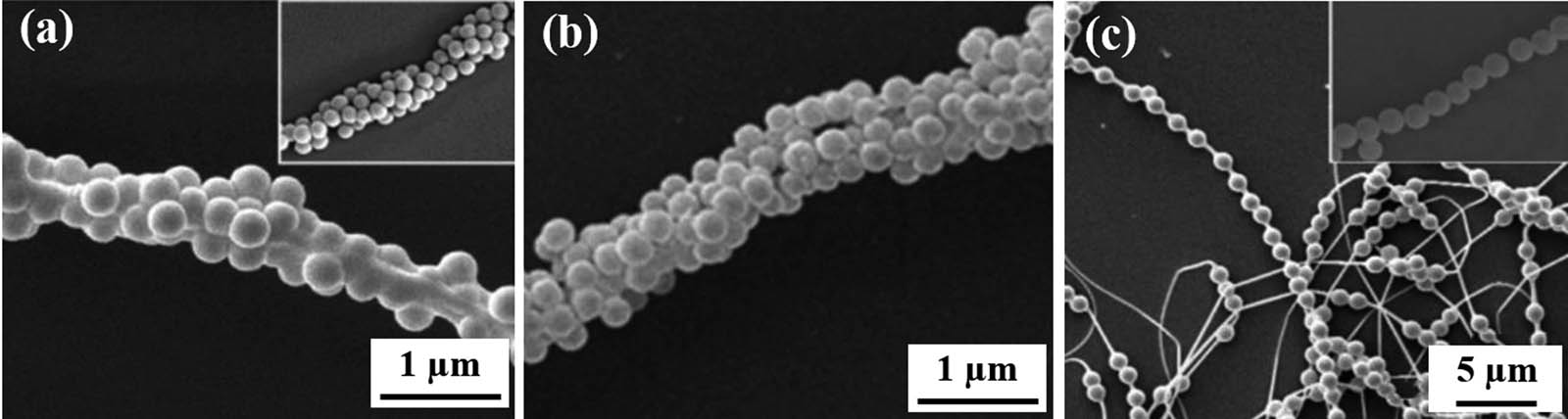

Some other structural materials obtained by electrospinning, such as bead-on-string nanofibers (149), thorn-like fibers (150), pearl-necklace structure fibers (151), etc., are reported. Wire bead nanofibers are potential carriers for drug delivery and tissue engineering in recent years. In this structure, due to the special cross distribution between the nanofibers and the microspheres, the sufficient encapsulation and slow release of the drug particles can be satisfied. Therefore, this special fiber structure has attracted extensive attention of researchers. In 2004, Lim et al. (151) dispersed silicon particles among different polymers (PAN, PEO, polyacrylamide (PAM), etc.) to obtain a pearl necklace-type electrospun fiber assembled with a 1D gel, as illustrated in Figure 17.

The SEM images of electrospun fibers of (a) PEO, (b) PAN, and (c) PAM (151) (©American Chemical Society 2006).

By adjusting the surface tension and viscosity of the electrospinning liquid and the charge density carried by the jet, the beaded nanofibers can be formed. Ordinarily, lower viscosity and surface charge density are conducive to the formation of bead-like nanofibers; while the decrease in surface tension makes the bead like nanofibers gradually disappear. Generally speaking, microbeads and nanofibers are made of the same materials (149). By combining other strategies, beads made from materials other than nanofibers could also be produced, mimicking the structure of a spider’s naturally captured silk. In this study, low-viscosity spray-able external liquid and high-viscosity spinnable internal liquid were separated by coaxial electrospinning, and hydrophilic beads were imprinted on hydrophobic thin lines (150). The key to the formation of beaded nanofibers is the use of external fluids with high surface energy to prevent adhesion of sheath components to core components and spontaneous Rayleigh cracking of external fluids in jets under the action of electric fields. Microbead nanofibers can also be prepared by emulsion electrospinning. For example, PS beads can be generated on PVA nanofibers by electrospinning water-coated oil emulsions containing PS and PVA. Similarly, alginate microspheres can also be formed on PLA nanofibers by electrospinning. The microspheres were formed due to the insufficient jet stretch and phase separation of two components in the emulsion during jet solidification. A colloidal suspension consisting of a polymer and microbeads is also used to produce pearl-like nanofibers. As shown in Figure 18, the number of tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) particles significantly influenced the formation of bead-on-string fibers (152).

The SEM images of tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) encapsulated bead-on-string nanofiber with different drug loading rates: (a) 0%, (b) 1%, (c) 2%, (d) 5%, and (e) 10% (152) (© Informa UK Limited 2019).

3 Functional applications of structural electrospun fibers

Functional electrospun fiber is considered as one of the most promising materials due to its high porosity, air permeability, washable, and designability. These advantages have attracted extensive attention from various research groups. There are many methods to prepare functional nanofibers, such as self-assembly, melt blowing, template, solution blowing, electrospinning, etc. Of all the nanofiberpreparation methods, electrospinning is considered to be a very effective method and has been widely used in academia and industry. Electrospun fibers have many advantages, such as small diameter, large specific surface area, rich pores, adjustable structure, simple chemical modification and low cost, and have wide application prospects in many fields. At present, functional electrospun fibers have been applied in the fields of catalysis, drug release, environmental protection battery energy, and so on.

3.1 Drug release

Electrospun fibers are drawing increasing interest due to their remarkable simplicity, versatility, and potential application in drug release fields. Huang et al. (153) elaborated on the development of electrospinning. Notable applications to date include filtration (154), nanosensors (155), wound dressings (156), drug release (157), enzyme immobilization (158), and tissue engineering scaffolds (159). Electrospun fiber can realize the burst release, stable release, pulsating release, delayed release, and two-phase release of drugs mainly because of its strong carrying capacity, high packaging efficiency, strong expansibility, simple preparation, and low cost (160).

Qin et al. (161) dissolved aspirin in chitin/pullulan spinning solution and obtained fast dissolving oral films (FDOFs) by electrospinning. Within 60 s, the FDOFs fully dissolve in water, thereby rapidly releasing the template drug aspirin and successfully demonstrating its potential in the oral mucosal release system. However, when the drug is simply mixed with the matrix, the release of the drug is unstable and prone to sudden release, which is not conducive to sustained release. Pores on the surface of fibers can enhance the burst release to improve the immediacy of the drugs. Meanwhile, the inner pores facilitate the slow release of the drug. Hou et al. (162) introduced α-NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ NCs into the spinning fluid to form the precursor nanofibers. After roasting at 550°C, the α-NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+@silica fiber could prepare the composite nanofibers with up-conversion luminescence properties. When the fiber is loaded with ibuprofen, the up-conversion luminescence intensity is reduced to a certain extent. With the release of ibuprofen, the intensity of up-conversion luminescence increases linearly. This unique property can be used for the detection of drug release.

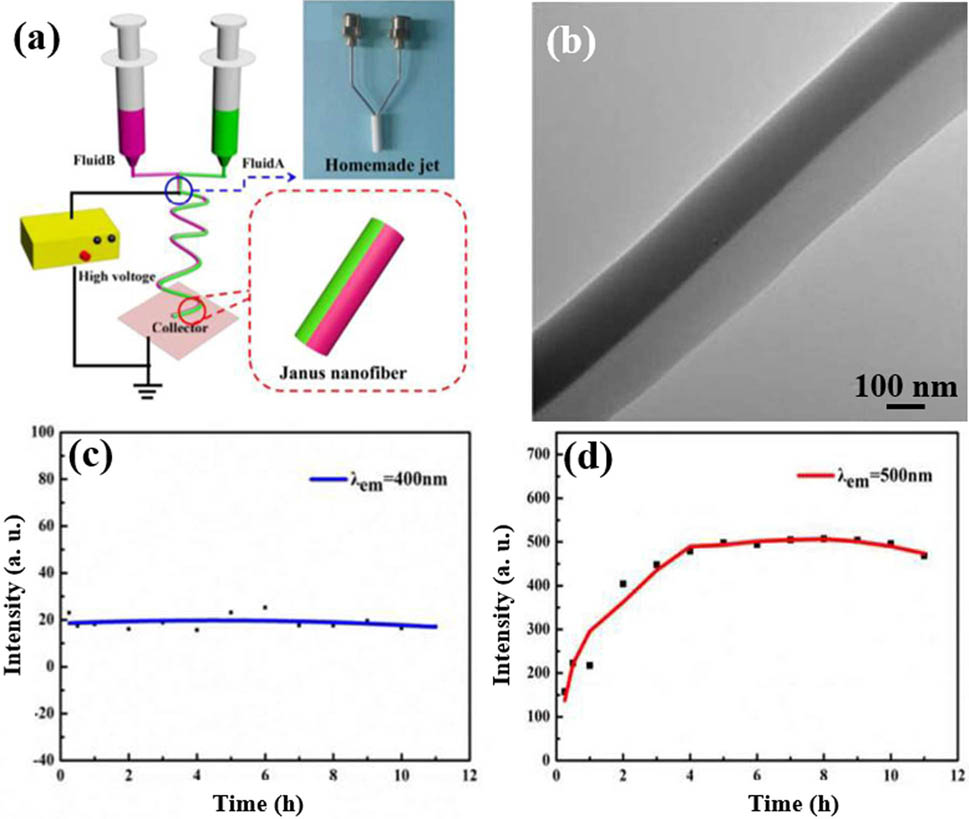

Besides, Janus structure has more functional partitions, and both sides of Janus fiber can be in direct contact with the external environment, so it has unique advantages in drug loading system. On the basis of the functions of common drug load and release, the material can be endowed with special abilities such as drug release detection ability, self-supporting property, and dual efficacy. Geng et al. (163) designed and constructed PAN/PVP ultrafine fiber membrane by side-by-side electrospinning, as shown in Figure 19a. Figure 19b shows TEM image of the PAN/PVP Janus fibers. Janus structured electrospun fibers consist of a water-soluble PVP and a water-insoluble PAN, i.e., two different polymers mixed with the drug dexamethasone of the same quality. It was found that the drug was released quickly and then slowly, and the ultrafine fiber membrane remained self-sustaining after being immersed in water for a period of time, as manifested in Figure 19c and d. Yang et al. (164) prepared PVP/EC Janus nanofibers for wound dressings using self-made eccentric spinneret. The antibiotic drug ciprofloxacin (CIP) and silver NPs were introduced into the PVP side and the EC side of Janus fiber, respectively. CIP is amorphously distributed in the fiber because of the good chemical compatibility between CIP and PVP. The drug release experiment shows that the CIP drug release can reach 90% in 30 min. The antibacterial experiment shows that PVP-CIP/EC-Ag NPs Janus fibers have satisfactory effect on inhibiting the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. CIP on the PVP-CIP side can be quickly released and has a strong bactericidal effect in the initial stage. Also, Ag NPs on the EC-Ag NPs side can maintain a long-term bacteriostatic effect.

(a) Diagram of the side-by-side electrospinning, (b) TEM image of the PAN/PVP Janus fibers, photoluminescence intensity of the dissolution at (c) 400, and (d) 500 nm with release time (163) (© The Royal Society of Chemistry 2017).

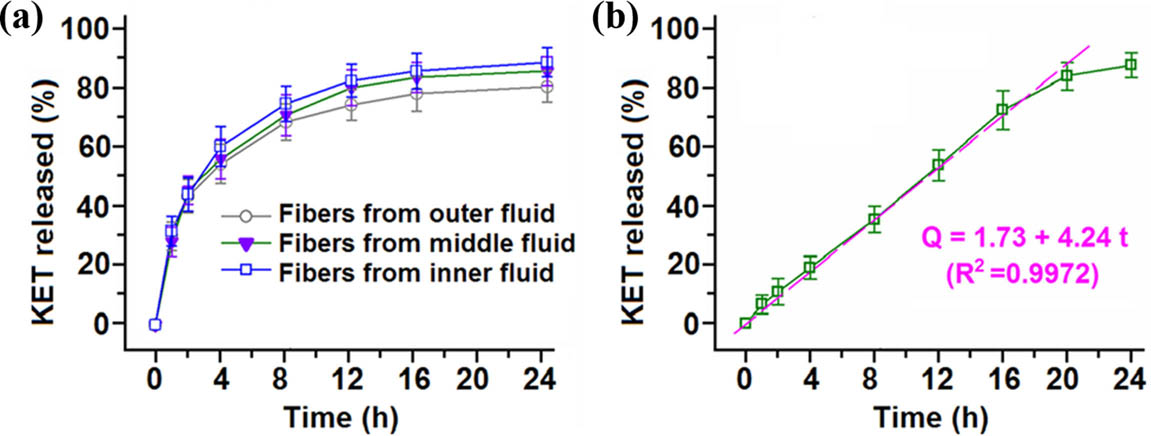

In biomedical applications, coaxial nanofibers are superior to uniaxial nanofibers in terms of drug loading and releasing (165). The biggest characteristic of core–shell structure is that the release process of drugs can be better controlled to prevent drugs from being released prematurely, and the existence of core–shell structure can avoid the destruction of physical and chemical properties of drugs in the core layer by the external environment. Santos et al. (166) constructed chitosan/PVA-TCH nanofibers with coaxial electrospinning. The hydrophilicity, swelling rate, and degradation rate of the nonwoven fibers reduced but the mechanical properties of the nonwoven fibers improved by using genipin–alcohol solution. The cross-linked nonwoven fiber membrane can release TH stably for more than 14 days, and the cross-linked nonwovens containing TH have strong antibacterial activity against periodontitis bacteria. He et al. (167) used coaxial electrospinning to prepare fiber mats with dual-load drug release for the treatment of chronic periodontal inflammatory diseases. The fiber has obvious core/shell structure, i.e., the outer diameter is 1.5–1.7 μm and the inner diameter is less than 1.0 μm. Naringin in the inner layer can be released slowly for a long time to guide tissue regeneration. The outer layer consists of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid/metronidazole (MNA), which can be released in a short time to inhibit the bacterial growth. Recently, Park’s group reviewed in detail the application of coaxial nanofibers in drug delivery (126). In addition, on the basis of coaxial electrospinning, the researchers developed the three-axis electrospinning and prepared electrospun fiber with obvious three-layer structure (168). In this kind of fiber, each layer possesses ethyl cellulose of the same concentration; and in each layer, the ketoprofen (KET) concentration gradually increases from the outer layer to the inner layer. In vitro dissolution tests shows that the nanofibers could release KET linearly within 20 h, as illustrated in Figure 20a and b. Yu’s group also improved the triaxial electrospinning (169). The gliadin/ferulic acid core–shell electrospun fiber coated with ethyl cellulose was prepared by using the nonspinning solution of acetic acid and acetone in the outer layer, the non-spinning ethyl cellulose in the middle layer, and the spinnable gliadin/ferulic acid in the inner layer. In the electrospinning process, the outer solvent ensures the uniform distribution of charge on the surface of the electrospinning jet. The presence of intermediate ethyl cellulose avoids the explosive release of inner drugs and makes the release process conform to the zero-order release principle. The inner spinnable layer plays a guiding role in the formation of nanofibers.

In vitro dissolution test results for (a) the monolithic and (b) the trilayer nanofibers (168) (© American Chemical Society 2015).

At present, researchers have developed a large number of load–release systems with different structures and functions for electrospinning fiber drugs, but they also face many challenges. In order to obtain a more ideal drug-carrying material, more experiments must be carried out with different parameters. For example, although the outer organic solvent mentioned above can protect and promote the internal fiber forming, a small amount of organic solvent is still left after the formation of electrospinning fiber, which may cause damage to the body. In addition, most of the loading and releasing experiments of drug-loading materials are confined to in vitro studies, so more in vivo studies and clinical treatment studies should be carried out to realize the practical applications.

3.2 Catalysis

Electrospun nanofibers with porous, core–shell, hollow and Janus structure have been widely used in the field of catalysis (170). Porous fibers not only provide a larger oxygen uptake area but also capture more photons. In addition, electrospun fibers with porous structure can make the reactant molecules to have more contact ways with the catalyst, thus improving the catalytic efficiency of the catalyst. Kumar et al. (171) reported a kind of catalytic active porous and hollow TiO2 nanofiber coated with gold NPs by sol–gel chemistry and coaxial electrospinning. The resultant Au@TiO2 porous hollow nanofibers show good catalytic activity and recyclability. Zhan et al. (172) prepared hollow TiO2 nanofibers with mesoporous walls by coaxial electrospinning and introducing pluronic (P123) as a pore-making agent. The BET surface area of nanofibers is between 200 and 208 m2 g−1. As expected, fiber decomposition of methylene blue (MB) and rhodamine B (RhB) has high photocatalytic activity. The study of electrospinning TiO2 fiber as photodegradation catalyst shows that the degradation efficiency of porous fiber to such dyes as MB and RhB was higher than that of nonporous fiber. Zhang et al. (173) successfully prepared ZnIn2S4/In2O3 nanofiber photocatalyst with layered structure through the combination of electrospinning–calcination and low-temperature solvothermal method. As illustrated in Figure 21a and b, 2D ZnIn2S4 nanometers are grown on the surface of 1D In2O3 nanofibers to form a core–shell structure, which enables ZnIn2S4/In2O3 nanofiber photocatalyst to have better energy band matching, widens the visible light absorption range of the interface, increases the specific surface area, and accelerates the separation and migration of photoelectrons and holes. Under visible light irradiation, the reaction rate constant of photocatalytic Cr(vi) reduction of nanofibers under visible light irradiation is 5.59, as illustrated in Figure 21c. ZnIn2S4/In2O3 nanofibers can completely reduce the toxicity of Cr(VI) within 90 min, and its reduction performance is better than that of pure ZnIn2S4 and In2O3, as shown in Figure 21d.

The SEM images of ZnIn2S4/In2O3 nanofiber photocatalyst at (a) low and (b) high magnification, (c) photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) over different prepared samples under visible light irradiation, and (d) the photocatalytic Cr(VI) reduction efficiency (173) (© 2020 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved).

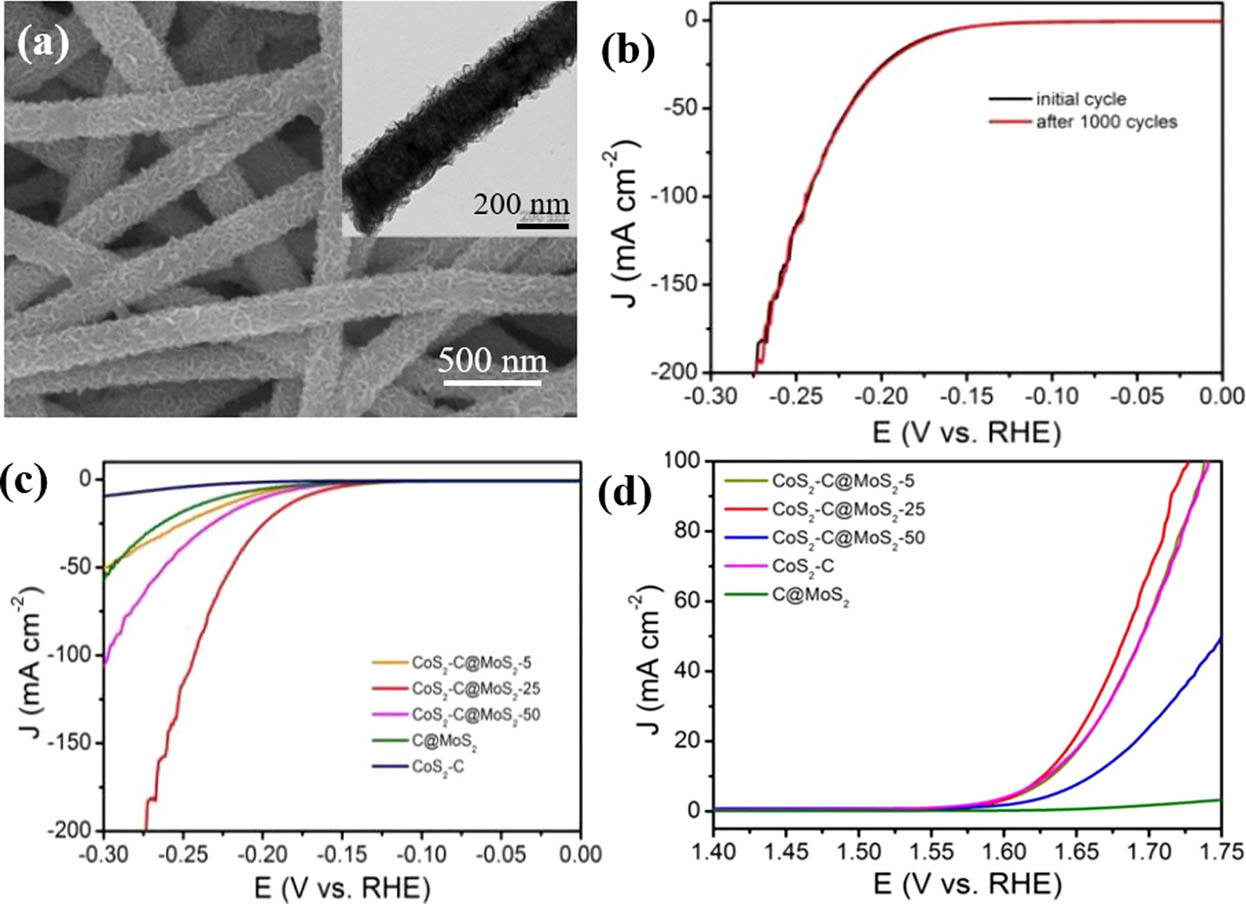

In addition, Lu et al. (174) reported a method for the synthesis of CoS2-C@MoS2 core–shell nanofibers using electrospinning Co-CNFs as templates through one-step hydrothermal reaction and vulcanization process. The synthesized CoS2-C-MoS2 core–shell nanofibers possess excellent electrocatalytic activity and stability for hydrogen-evolution reaction (HER), mainly due to the unique structure and the synergistic effect among various components, as manifested in Figure 22a. The overpotential is about 173 mV at 10 mA cm−2, and the current density almost does not change after 1,000 cycles, as displayed in Figure 22b. In addition, CoS2-C@MoS2 core–shell nanofibers also show excellent oxygen-evolution reaction (OER) catalytic activity and HER, making them an effective candidate for bifunctional hydrolytic catalysts, as shown in Figure 22c and d.

(a) The SEM and corresponding inset TEM images of CoS2-C@MoS2 core–shell nanofibers, (b) LSV curves of CoS2-C@MoS2-25 as working electrode initially and after 1,000 CV cycles; electrochemical analysis of (c) hydrogen-evolution reaction, and (d) oxygen-evolution reaction (174) (© American Chemical Society 2019).

However, the low utilization rate of light still exists in the catalytic process. In order to realize better utilization of sunlight, it is a very desirable choice to develop catalysts with low cost and high efficiency without precious metals. The fibers of Janus structure have asymmetric structure, including shape, electronic structure, physical, and chemical properties of the surface asymmetry, which can provide selectivity, diversity, and controllability for the design of catalysts. Janus structure can realize the effective separation of photoelectrons and holes. Sun et al. (175) successfully prepared a novel carbon-based Janus nanofiber heterojunction photocatalyst by using conjugated electrospinning. On one side of Janus nanofiber is TiO2/C nanofiber responding to ultraviolet light, and on the other side is Bi2WO6/C nanofiber responding to visible light. This special structure can effectively utilize sunlight and realize the effective separation of photoelectron and holes. Under the condition of ultraviolet and visible light and without precious metal as co-catalyst, the photocatalytic hydrogen production efficiency of Janus nanofiber photocatalyst is 11.58 and 16.32 mmol h−1 g−1, and the degradation of MB and RhB reached 93.3% and 97.9% at 160 and 140 min, respectively. Compared with the photocatalyst of independent TiO2/C nanofiber or Bi2WO6/C nanofiber, the photocatalyst has dual functional characteristics simultaneously, and the photocatalytic performance is better than that of two separate photocatalysts. The two photocatalytic properties are successfully concentrated in Janus fibers, thus improving the utilization rate of light.

3.3 Reinforced composites

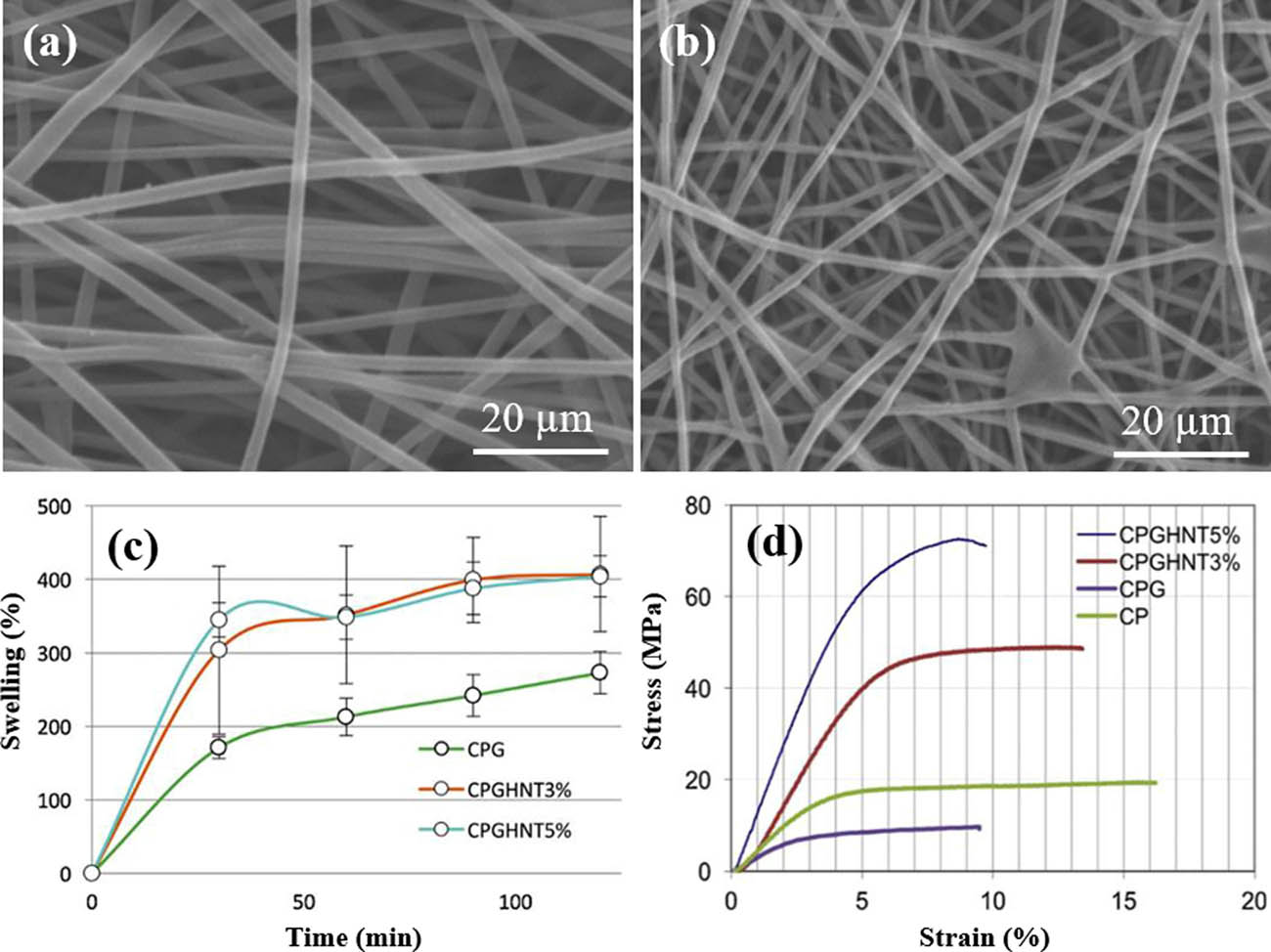

Fiber-reinforced composite is a new type of advanced functional material with excellent properties such as high strength, high stiffness, high modulus, light weight, and corrosion resistance (176). As products of two or more constituent materials of fiber/matrix or fiber/matrix/filler, they have synergistic effects to achieve a wide range of different properties such as mechanical integrity, electrical conductivity, optical sensitivity, and electromagnetic interference shielding. The inherent flexibility of composite materials makes them play an important role in a wide range of applications such as aerospace, marine, automotive, civil construction, and sports industry (177,178,179). The high specific surface area of electrospun fiber is favorable for interface interaction, making it an ideal reinforcement. At present, electrospun nanofiber–reinforced composites can be used in various fields, such as tissue engineering scaffolds, aerospace materials, dental prosthetics, and fuel cell materials. In 2003, Huang et al. (176) published the first review of electrospun nanofiber–reinforced polymer composites. Subsequently, Zucchelli’s group also published a detailed review of the structural properties of electrospun nanofiber-reinforced composites (180). Ayutsede dissolved the regenerated silk in the formic acid carbon nanotube dispersion and electrospun the mulberry silk and single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT) composite fibers (181). Transmission electron microscope observation of the reinforced fibers show that SWNTs were embedded in the fibers. Compared with unreinforced directional fibers, the mechanical properties of SWNT-reinforced fibers show an increase of up to 460% in Young’s modulus. To further enhance the mechanical properties of the material, Kai et al. (178) prepared nanofiber hydrogels by adding the electrospun PCL/gelatin “blends” or “coaxial” nanofibers to the gelatin hydrogels. The Young’s modulus of composite hydrogel increased from 3.29 ± 1.02 kPa to 20.30 ± 1.79 kPa, and the fracture strain decreased from 66.0 ± 1.1% to 52.0 ± 3.0% with the addition of nanofibers. Subsequently, Koosha et al. (182) prepared in glyoxal cross-linked chitosan-/PVA-reinforced hydrogel nanofibers by one-step electrospinning. Figure 23a and b shows SEM images of CPGHNT (C: Chitosan; P: Polyvinyl Alcohol; G: Glyoxal; HNT: Halloysite nanotubes) with different contents. Although the cross-linked nanofibers were insoluble in water, due to the hydrophilicity of halloysite nanotubes, the swelling degree of the cross-linked chitosan/PVA nanofibers increased from 272% to about 400%, as displayed in Figure 23c. Compared with chitosan/PVA nanofibers, the tensile strength of cross-linked nanocomposite fibers increases 2.4 and 3.5 times by adding 3% and 5% HNT, as revealed in Figure 23d, respectively.

The SEM images of nanocomposite nanofibers (a) CPGHNT3% and (b) CPGHNT5%, (c) compressive swelling behavior of nanofibers in distilled water, and (d) compressive stress–strain curves of the nanofiber mats (182) (© 2019 Elsevier B.V.).

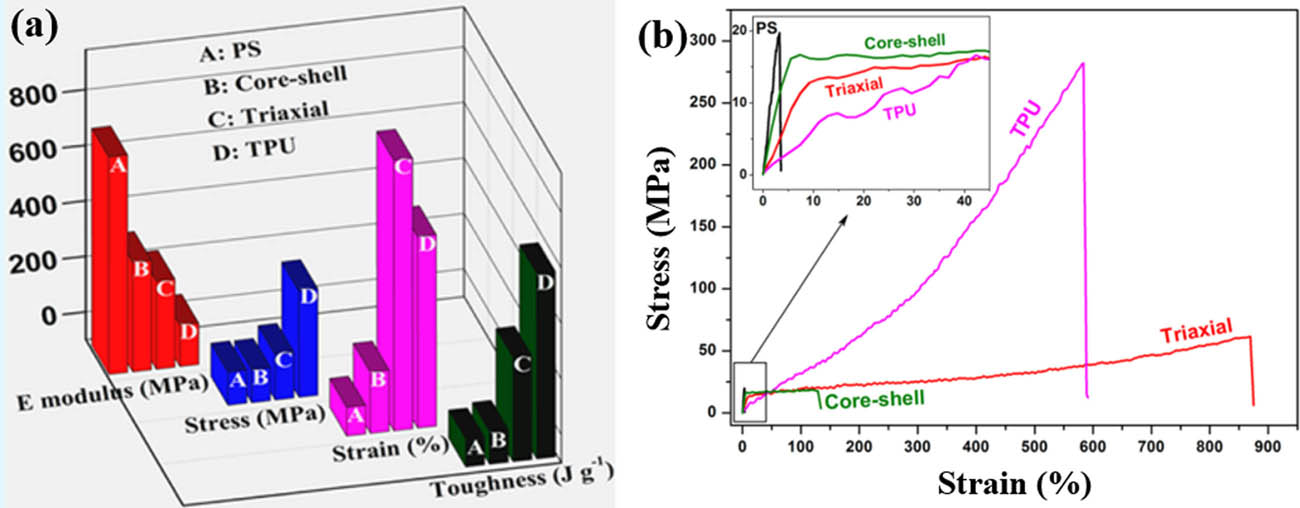

Yu et al. (183) reported a simple preparation method using electrospinning and in situ polymerization to prepare Polyaniline (PANI)/Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) nanofibers with high tensile and conductive properties. Compared with ordinary PANI/PVDF nonwoven fabrics, the strain sensor of PANI/PVDF nanofiber felt with graphic structure prepared can detect up to 110% strain, 2.6 times that of the ordinary PANI/PVDF nonwoven fabrics, and much higher than the previously reported value (usually less than 15%). When the applied strain force is within a wide range of 0–85%, the conductivity of the graph strain sensor shows a linear response and has good tensile resistance. In addition, the PANI/PVDF strain sensor has shown good durability in over 10,000-fold unfolding tests and has been used to detect finger movement. In addition, coaxial/triaxial electrospinning has been shown to improve the mechanical properties of electrospinning fibers effectively. Han et al. (184) conducted coaxial electrospinning with PU as the core and PC as the shell and found that 8% wt% PU of the fiber had the best enhancement effect on the fiber membrane. PEO core and PEO/multiwalled carbon nanotube (MWNT) shell fibers were also prepared by coaxial electrospinning and only a small amount of MWNT fibers was added into the sheath to obtain significant fiber reinforcement effect. Nguyen et al. (185) used coaxial electrospinning method to strengthen chitosan with PLA as the core material. Jiang’s research group found that the tensile strength, elongation at break, and toughness of PS fibers with three different structures significantly improved by adding 30 wt% TPU. This enhancement mainly comes from the two layers of PS TPU. Therefore, coaxial and triaxial electrospinning provide more options for the preparation of high-performance electrospinning-reinforced fibers (186), as shown in Figure 24. Recently, Jiang et al. (187) reviewed the electrospinning nanofiber-reinforced composites in detail and introduced the properties of electrospinning nanofiber and the preparation method of the reinforced composites. The electrospinning nanofiber–reinforced composites with different kinds of high-performance polymer nanofibers are discussed. It can be also seen that more and more attention has been paid to the study of electrospinning fiber in reinforced composites.

(a) Improved mechanical properties and (b) stress–strain curves of single electrospun fibers in tensile load (186) (© American Chemical Society 2014).

3.4 Electrodes for supercapacitor

The application of electrospun fibers in clean energy and capacity storage materials has also been widely concerned (188,189). The energy density and capacitance (5 W h kg−1, 80–100 F g−1) of supercapacitor are 20–200 times higher than that of traditional capacitor. It is considered as a good energy storage device due to the advantages of small volume, large capacity, high power density, long life cycle, fast charging speed, wide working temperature limit, green environment protection, and high safety and reliability. As we all know, electrode material is the core of supercapacitor, and it is an important part of supercapacitor to realize charge storage and directly affects the performance of capacitor. Its conductivity and specific surface area are important parameters. Larger specific surface area can adsorb more electrolyte ions and store or release more charges.

In order to obtain high capacitor performance, different structures have been prepared, such as solid, porous, core–shell, and hollow structures. For porous electrospun fiber materials, porous nanostructures can increase the contact area between the electrodes and the electrolyte, short the transmission path of ion, and the total charge–discharge process can well adapt to the volume change caused by the strain. As active electrode materials, CNFs can increase the surface area and produce suitable pores, promote the diffusion and absorption of electrolyte ions, and allow high charge discharge rate (190,191). Porous carbon fiber materials are usually obtained by calcining precursors of polymer electrospun fibers (PVP, PANI, PVDF, PAN, PEO, etc.). The carbonization of electrospun polymer blends also controls the pore structure of CNFs. When cellulose acetate (CA) was added into PAN solution, a controllable microporous structure was formed, with no activation process. Compared with pure PAN-derived CNFs, the BET surface area of PAN/cellulose (15 wt%)-derived CNFs increased from 740 to 1,160 m2 g−1, the micropore surface area was 919 m2 g−1, and the mesopore surface area was 241 m2 g−1.

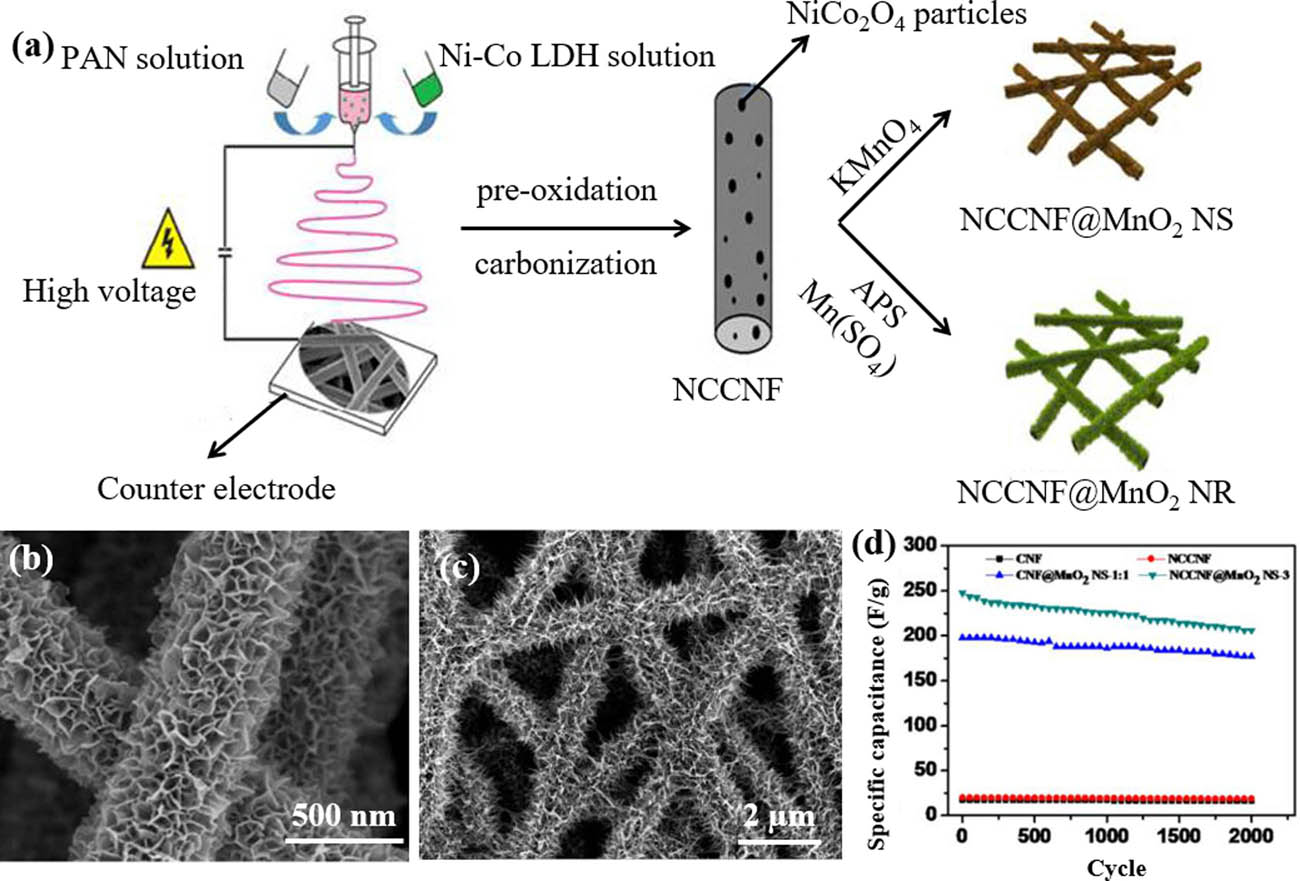

Core–shell structure can effectively solve the problem of volume expansion caused during charging and discharging due to its large porosity and high specific surface area. Meanwhile, the core–shell structure effectively avoids the addition of adhesives and ensures good specific capacity and cycling stability under high current load. Lai et al. (192) reported a core–shell structured carbon fiber growing MnO2 nanosheets or MnO2 nanorods on NiCo2O4-doped carbon fibers (marked as NCCF@MnO2 NS and NCCF@MnO2 NR, respectively) by redox deposition method to obtain composite fiber materials with core–shell structure and used them as electrode materials for flexible supercapacitors. Schematic diagram for the preparation of NCCNF@MnO2 NS and NCCNF@MnO2 NR is shown in Figure 25a. The SEM images of NCCNF@MnO2 NS and NCCNF@MnO2 NR are separately shown in Figure 25b and c. It can be concluded that NCCNF@MnO2 NS and NCCNF@MnO2 NR have high porosity. The capacitances of NCCF@MnO2 NS and NCCF@MnO2 NR are, respectively, 918 F g−1 and 827 F g−1 (based on the active materials) at a scan rate of 2 mV s−1, and good cycling ability with 83.3% and 87.6% retention after 2,000 cycles, as illustrated in Figure 25d. A summary of structural electrospun nanofibers for supercapacitor application is shown in Table 1.

(a) Schematic diagram for the preparation of NCCNF@MnO2 NS and NCCNF@MnO2 NR, the SEM images of (b) NCCNF@MnO2 NR and (c) NCCNF@MnO2 NS, cycling stability of (d) NCCNF@MnO2 NS and at a current density of 10 A g−1 (192) (© American Chemical Society 2015).

Electrospun electrodes materials for supercapacitors

| Published | Structure of nanofiber | Raw materials | Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Porous | RuCl3 | 104 F g−1 in 1 M H2SO4, 12.8% loss after 20,000 cycles | (193) |

| 2012 | Porous | VO(acac)3 | For bulky paper/V2O5 HEC, 135 F g−1 at 30 mA g−1 in 1 M LiPF6 containing EC and DMC, maximum energy and power densities of 18 W h kg−1 and 315 W kg−1 | (194) |

| 2013 | Porous | Fe(acac)3 | 348 F g−1 at 5 A g−1 in 1 M LiOH, 18–20% loss after 3,000 cycles | (195) |

| 2013 | Porous | (CH3COO)2Ni·4H2O | 248 F g−1 at 1.0 A g−1 in 6 M KOH, 1.8% loss after 5,000 cycles | (196) |

| 2015 | Hollow | (CH3COO)2Ni·4H2O | 336 F g−1 at 5 mA cm−2 in 6 M KOH, 17% loss after 1,000 cycles | (197) |

| 2015 | Porous and Hollow | Co(CH3COO)2, PAN | 586 F g−1 capacitance at 1 A g−1, 26% loss after 2,000 cycles at 2 A g−1 | (198) |

| 2015 | Porous | Mn(CH3COO)2.4H2O | 210 F g−1 at 0.3 A g−1 in 1 M KCl, almost 0% loss after 500 cycles, energy density of 23 W h kg−1 at the power density of 120 W kg−1 | (199) |

| 2016 | Coaxial-line | Mn(CH3COO)2·4H2O, PVP | 216 F g−1 at 0.5 A g−1 in 6 M KOH, 7% loss after 1,000 cycles | (200) |

| 2018 | Porous worm-like | NiMoO4/carbon | Specific capacitance (1088.5 F g−1 at 1 A g−1), good rate capability (860.3 F g−1 at 20 A g−1) a capacitance retention of 73.9% after 5,000 cycles | (201) |

| 2019 | Core–shell | NiCo2O4, PAN, PVP | 1,586 F g−1 at 1 A g−1, 92.5% capacitance retention after 5,000 cycles at 10 A g−1 | (202) |

| 2019 | Porous | SiO2 NPs, PAN | 248 F g−1 at 1 A g−1, only 1.1% loss after 2,000 cycles | (203) |

| 2019 | Cross-linked and porous | PAN | 323 F g−1 at 0.5 A g−1, energy density of 14.3 W h kg−1 at a power density of 162.5 W kg−1 | (204) |

| 2020 | Porous | PAN | Capacitance retention of 94% after 10,000 cycles | (205) |

| 2020 | Porous | Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O, PAN, PVA | 216.7 F g−1 at 0.5 A g−1 in 1 M H2SO4, capacitance retention of 98.8% after 100,000 cycles at 10 A g−1 | (206) |

| 2020 | Hollow | graphene nanosheets, PMMA, PVP, PAN | Capacitance of 249 F g−1 at 1 A g−1, capacitance retention of 99% after 5,000 cycles | (207) |

3.5 Electrodes for battery

With the rapid growth of the demand for electronic devices and electric vehicles, the development of next-generation batteries with long life and high energy density has become a top priority (89,208,209,210,211,212). At present, the biggest problems of energy storage system are structural instability, slow redox dynamics, short life cycle, and low energy density. For example, the large-capacity anode material changes in volume up to 400% during the cycling process, resulting in structural instability and electron ion transport degradation (213,214). In another example, the main problem of lithium batteries is sulfur cathode, which is not conductive and dissolves polysulfide in the cycle process, resulting in low capacity and short life cycle (215,216). The problem is exacerbated by an 80% change in sulfur volume during the cycle. The performance of the battery depends largely on the characteristics of electrode. Fiber is an ideal electrode material with high aspect ratio, 3D cross-linking network structure, larger specific surface area, and higher porosity obtained by subsequent treatment (217,218), which can increase the contact area between electrode material and electrolyte, shorten the ion transmission distance, and promote electron transport.

For the sodium ion batteries (SIBs), the reversible charge and discharge are realized by Na+ ion shuttle between the cathode and anode materials (216,219). However, the sodium ions are larger and heavier than lithium ions, which usually results in slow SIB reaction kinetics. In addition, the process of sodiumization often leads to large-volume changes in electrode materials and even irreversible structural failure, which worsens the cycling stability of the battery. In order to solve the above problems, different morphological structures (181,182) (such as porous structures, hollow structures, and core–shell structures) were designed, and the electrochemical properties of the materials were improved. To further ensure the migration of sodium ions in the electrolyte, Niu et al. (220) designed graphene-coated Na6.24Fe4.88(P2O7)4 (named as NFPO@C@RGO) electrospinning composite nanofibers, and the SEM and TEM images of NFPO@C@RGO is separately revealed in Figure 26a and b. Compared with the original NFPO@C composite material, the NFPO@C@RGO composite fiber with 3D network structure shows significantly improved specific capacity. At 1,280 mA h g−1, its specific capacity is 55.3 mA h g−1, as displayed in Figure 26c. At 40 mA h g−1, the specific capacity is 99 mA h g−1 after 320 cycles, as shown in Figure 26d.

(a) SEM, (b) TEM images, and (c,d) electrochemical performances of NFPO@C@RGO (220) (© The Royal Society of Chemistry 2017).

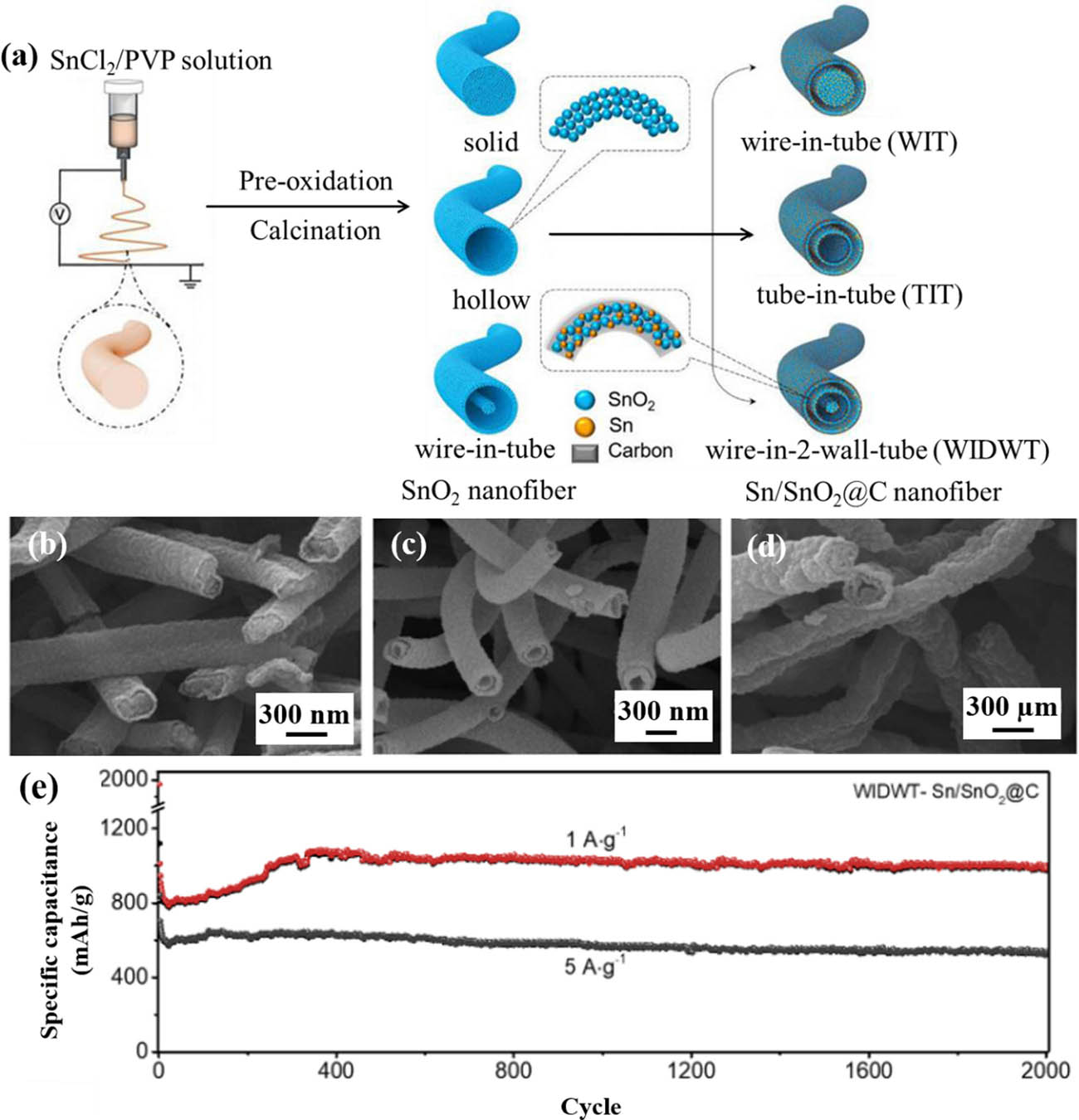

According to the research report, the volume expansion occurs during the charging and discharging processes. The porous structure makes it easier for the electrolyte to penetrate into the fiber, increasing the number of contact and electrochemical reaction sites between the electrolyte and the active material. In addition, the cavities in the porous fibers effectively adapt to the volume expansion during the process of nitrification and denitrification. Additionally, the problem of volume expansion during charging and discharging can be alleviated by porous structure. For example, when Sn4P3 is used as the positive electrode material of SIB, Sn4P3 expands greatly in the cycling process, which will lead to the disintegration of electrode and poor cycling performance. Ran et al. (221) encapsulated Sn4P3 nanodots as porous, independent CNFs using a combination of electrospinning and heat treatment. Due to its unique fiber structure and ultra-small Sn4P3 particle size (8 nm), good capacity and long-term stability can be obtained. After 200 cycles, the reversible capacity reaches 712 mA h g−1. A 3D self-supporting flexible electrode NiCo2S4@N-HCNFs was obtained by loading bimetallic sulfide onto hollow carbon nanotubes by Zhang et al. (222) The electrochemical performance test results show that its capacity was 263.7 mA h g−1 after 200 cycles at a current density of 100 mA g−1. At 3,200 mA g−1, it can keep good stability of 134.3 mA h g−1 after 600 cycles. In addition, the hollow carbon nanotube structure effectively alleviates the sulfur shuttle phenomenon due to its large specific surface area and high porosity. Gao et al. (223) prepared a graded multiwall hollow-core Sn/SnO2@C nanofiber (WIDWT Sn/SnO2@C) by electrospinning, coating, and annealing reduction. Figure 27a demonstrates the preparation process of WIDWT Sn/SnO2@C and intermediates, and the SEM images of corresponding samples are, respectively, shown in Figure 27b–d. The wall thickness of hollow nanofiber can be adjusted by controlling the coating thickness of polypyrrole. This special double-tube inner layer keeps enough but not excessive gap between the inner core and the shell, which effectively alleviates the volume expansion and ensures good transport kinetics of Li+-ions and electrons during charging and discharging. The cooperation of multistructure and composition optimization contributes to the excellent rate capability (812.1 mA h g−1 at 1 A g−1 and 566.5 mA h g−1 at 5 A g−1, as shown in Figure 27e) and remarkable cycling performance (986.3 mA h g−1 at a current of 1 A g−1 and 508.2 mA h g−1 at 5 A g−1 after 2,000 cycles) as the anode materials of lithium ion batteries. In addition, we also summarized the electrospun fibers with special structure used as battery electrode materials and their electrochemical properties, as shown in Table 2.

(a) Fabrication scheme of multiwall Sn/SnO2@C hollow nanofibers, (b–d) SEM images of WIT, TIT, and WIDWT Sn/SnO2@C hollow nanofibers, and (e) electrochemical performances of Sn/SnO2@C nanofiber (223) (© 2019 Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim).

Electrospun fibers with special structure electrodes materials for battery

| Published | Structure | Raw materials | Electrochemical properties | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Hollow | Si NPs, tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane, PAN | The capacity after 50 cycles is 72.6% of the theoretical capacity and the capacity of 500 mA h g−1 at 5 A g−1 | (213) |

| 2014 | Hollow and porous | Ni(Ac)2·4H2O, PAN, PMMA | The reversible capacity remains 700 mA h g−1 at 1 C after 100 cycles and 430 mA h g−1 at 5 C after 200 cycles | (224) |

| 2014 | Normal fiber | Multi-walled CNTs, Si NPs, PAN | The remaining capacity of 1,250 mA h g−1 in the last cycle at C/2 | (225) |

| 2014 | Porous | PAN, F127 | 266 mA h g−1 after 100 cycles at 0.2 C (1 C = 250 mA h g−1) | (226) |

| 2015 | Porous | NaH2PO4,NH4VO3, PVP | 106.8 A h g−1 at 0.2 C and 103 mA h g−1 at 2 C, the cycling performance is 107.2 mA h g−1 after 125 cycles | (227) |

| 2017 | Porous | Zn(Ac)2, 2H2O, Co(Ac)2, 4H2O, PAN | Reversible capacities up to 346 mA h g−1 at 0.2 A g−1, life cycle of over 10,000 cycles | (228) |

| 2018 | Porous | SiO2@PB/SiO2, PAN, tetraethylorthosilicate | Capacity retention of 82.8% after 500 cycles at 1 C | (229) |

| 2018 | Porous | CeCl3, PVA, PTFE | The capacity of 1284.6 mA h g−1 at 0.5 C to 1038.6 mA h g−1 at 1 C and 819.3 mA h g−1 at 2 C | (230) |

| 2018 | Hollow | PAN, PS | 336.22 mA h g−1 at 0.05 A g−1, 132 mA h g−1 at 10 A g−1 | (231) |

| 2019 | Hollow | PMMA, aniline | Reversible charge capacity of 326 mA h g−1 at 20 mA h g−1, capacity retention of 70% even after 5,000 cycles at 1.6 A g−1 | (232) |

| 2020 | Hollow | Pyrrole, FeCl3, FeSO4·7H2O | Capacity of 210 mA h g−1 after 1,000 cycles at 0.1 A g−1 | (233) |

| 2020 | Porous | Fe(CH3COO)2, PVA, | Capacity of 360 mA h g−1 at 1 C after 1,000 cycles for sodium-ion batteries, 430 mA h g−1 at 6 C after 1,000 cycles for lithium-ion batteries | (234) |

| 2020 | Porous | SnCl4·5H2O, PVA, PS | Capacity retention of 92% even after a 30% strain | (235) |

3.6 Other applications

In addition to the above applications, electrospun fibers are used in self-repairing materials, shape memory materials, 3D printing, oil–water separation, air filtration, nanogenerators, flexible electronics skin, food packaging, tissue engineering, self-cleaning materials, and other fields. For example, the nonwoven mat based on electrospun nanofibers is superior in air permeability, flexibility, and self-support. They can be used to prevent pollution in medical equipment and produce protective clothing. By controlling the surface structure and chemical composition of nanofibers, the wettability of felt can be manipulated to realize self-cleaning ability and further realize oil–water separation. Shape memory polymer combines intelligent polymer and deformable structure and has potential applications in many fields, including aerospace, robotics, and biomedical science. Zhang et al. (236) obtained precursor fibers by electrospinning and then obtained PLA/PPy microfiber felt with coaxial structure by in situ polymerization on its surface. Under the stimulation of 30 V, it can completely recover its shape within 2 s. Wu et al. (237) reported a novel ultrathin self-healing composite carbon fiber/epoxy composite prepared by electrospinning. Liquid dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) was used as self-healing agent, which was wrapped in PAN to form core–shell type DCPD/PAN nanofibers. Three-point bending test was used to evaluate the self-healing effect of core–shell nanofibers on flexural stiffness of composite laminates after pre-damage and failure. The experimental results show that the self-repair between nanofiber layers can completely restore the bending stiffness of the composite after pre-damage. Simultaneously, these kinds of self-healing materials also have potential advantages in shape memory materials and supercapacitors. In addition, a porous electrospun fiber with self-sealing property is also reported (238). A detailed review about the application of self-healing/self-repairing fiber composites in reinforcing composites was reported by Cohades (239). As for water purification, the presence of hollow structure in Fe(OH)3@cellulose hollow nanofibers gives the material a very high water flux (11,200 L m−2 H−1 bar−1) (239). They can effectively remove a variety of pollutants in water, including phosphate, heavy metal ions, and organic dyes, with good reuse. In summary, fiber materials with special structures prepared by electrospinning have been widely used in various fields. How to combine the structural advantages with the properties of materials will be a major research in the future.

4 Conclusions and future perspectives

Electrospun fibers, owing to their well-known advantages of large specific surface area, high porosity, high aspect ratio, and tunable surface functionality, have emerged as one of the most active fields and applied in a broad spectrum of applications. Interestingly, recent progress in the field of structure tailoring of electrospun fibers shows that it has a great potential in the function tunability by creating innovative structures at nanoscale, just like spring/helical morphology, porous, hollow structure, core–shell, Janus, and triaxial configurations. Compared with other methods, electrospinning offers a facile way of generating continuous nanofibers with various desirable structures at nano- or microscale. In spite of such a wide range of applications in biomedical, catalysis, composites, and energy, many challenges and problems are yet to be solved:

Electrospun fiber with special structure cannot be produced on a large scale.

Although the preparation of porous or hollow fibers improves the specific surface area of fiber, but further research is still needed.

The inorganic electrospun fibers are usually prepared by calcination due to the solubility of many inorganic salt substances, but the mechanical properties and flexibility of electrospun fibers still need to be improved.

Organic solvents are involved in the preparation of electrospun fibers, which may cause pollution problems when applied in the environmental, biological medicine field, and battery energy.

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51903043, 51903123 and 51903235), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20190760), the Initial Research Funds for Young Teachers of Donghua University, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2232020D-18).

References

(1) Gelder D. The stability of fiber drawing processes. Ind Eng Chem Fundamentals. 1971;10:534–5.10.1021/i160039a032Search in Google Scholar

(2) Liao X, Dulle M, de Souza e Silva JM, Wehrspohn RB, Agarwal S, Förster S, et al. High strength in combination with high toughness in robust and sustainable polymeric materials. Science. 2019;366:1376–9.10.1126/science.aay9033Search in Google Scholar

(3) Ding B. Electrospinning, fibers and textiles: A new driving force for global development. e-Polymers. 2017;17:209–10.10.1515/epoly-2016-0299Search in Google Scholar

(4) Greiner A, Wendorff JH. Electrospinning: A fascinating method for the preparation of ultrathin fibers. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:5670–703.10.1002/anie.200604646Search in Google Scholar

(5) Nikmaram N, Roohinejad S, Hashemi S, Koubaa M, Barba FJ, Abbaspourrad A, et al. Emulsion-based systems for fabrication of electrospun nanofibers: food, pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 2017;7:28951–64.10.1039/C7RA00179GSearch in Google Scholar

(6) Lou Z, Wang W, Yuan C, Zhang Y, Li Y, Yang L. Fabrication of Fe/C Composites as effective electromagnetic wave absorber by carbonization of Pre-magnetized natural wood fibers. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2019;4:43–50.10.21967/jbb.v4i1.185Search in Google Scholar

(7) Sugama T, Kukacka LE, Carciello N, Galen B. Oxidation of carbon fiber surfaces for improvement in fiber-cement interfacial bond at a hydrothermal temperature of 300°C. Cem Concr Res. 1988;18:290–300.10.1016/0008-8846(88)90013-0Search in Google Scholar

(8) Xu Q, Li Y, Feng W, Yuan X. Fabrication and electrochemical properties of polyvinyl alcohol/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) ultrafine fibers via electrospinning of EDOT monomers with subsequent in situ polymerization. Synth Met. 2010;160:88–93.10.1016/j.synthmet.2009.10.010Search in Google Scholar

(9) Sargeant TD, Guler MO, Oppenheimer SM, Mata A, Satcher RL, Dunand DC, et al. Hybrid bone implants: Self-assembly of peptide amphiphile nanofibers within porous titanium. Biomaterials. 2008;29:161–71.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(10) Jiang X, Bai Y, Chen X, Liu W. A review on raw materials, commercial production and properties of lyocell fiber. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2020;5:16–25.10.1016/j.jobab.2020.03.002Search in Google Scholar

(11) Tang Q, Fang L, Guo W. Effects of bamboo fiber length and loading on mechanical. Therm Pulverization Prop Phenolic Foam Compos J Bioresour Bioprod. 2019;4:51–9.10.21967/jbb.v4i1.184Search in Google Scholar

(12) Daenicke J, Lämmlein M, Steinhübl F, Schubert DW. Revealing key parameters to minimize the diameter of polypropylene fibers produced in the melt electrospinning process. e-Polymers. 2019;19:330–40.10.1515/epoly-2019-0034Search in Google Scholar

(13) Sun G, Sun X, Wang X. Study on uniformity of a melt-blown fibrous web based on an image analysis technique. e-Polymers. 2017;17:211–4.10.1515/epoly-2016-0053Search in Google Scholar

(14) Li Dan XY. Fabrication of titania nanofibers by electrospinning. Nano Lett. 2003;3:555–60.10.1021/nl034039oSearch in Google Scholar

(15) Yang X, Shao C, Liu Y, Mu R, Guan H. Nanofibers of CeO2 via an electrospinning technique. Thin Solid Films. 2005;478:228–31.10.1016/j.tsf.2004.11.102Search in Google Scholar

(16) Teo WE, Ramakrishna S. A review on electrospinning design and nanofibre assemblies. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:R89–106.10.1088/0957-4484/17/14/R01Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(17) Chronakis IS, Grapenson S, Jakob A. Conductive polypyrrole nanofibers via electrospinning: Electrical and morphological properties. Polymer. 2006;47:1597–603.10.1016/j.polymer.2006.01.032Search in Google Scholar

(18) Xue J, Xie J, Liu W, Xia Y. Electrospun nanofibers: New concepts, materials, and applications. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:1976–87.10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00218Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(19) Ding J, Zhang J, Li J, Li D, Xiao C, Xiao H, et al. Electrospun polymer biomaterials. Prog Polym Sci. 2019;90:1–34.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.01.002Search in Google Scholar

(20) Xu H, Jiang S, Ding C, Zhu Y, Li J, Hou H. High strength and high breaking load of single electrospun polyimide microfiber from water soluble precursor. Mater Lett. 2017;201:82–4.10.1016/j.matlet.2017.05.019Search in Google Scholar

(21) Zhou S, Zhou G, Jiang S, Fan P, Hou H. Flexible and refractory tantalum carbide-carbon electrospun nanofibers with high modulus and electric conductivity. Mater Lett. 2017;200:97–100.10.1016/j.matlet.2017.04.115Search in Google Scholar

(22) Jiang S, Uch B, Agarwal S, Greiner A. Ultralight, thermally insulating, compressible polyimide fiber assembled sponges. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:32308–15.10.1021/acsami.7b11045Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(23) Zhu J, Jiang S, Hou H, Agarwal S, Greiner A. Low density, thermally stable, and intrinsic flame retardant poly(bis(benzimidazo)benzophenanthroline-dione) sponge. Macromol Mater Eng. 2018;303:1700615.10.1002/mame.201700615Search in Google Scholar

(24) Jiang S, Cheong JY, Nam JS, Kim I-D, Agarwal S, Greiner A. High-density fibrous polyimide sponges with superior mechanical and thermal properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:19006–14.10.1021/acsami.0c02004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(25) Wu Y, Jiang Y, Shi J, Gu L, Yu Y. Multichannel porous TiO2 hollow nanofibers with rich oxygen vacancies and high grain boundary density enabling superior sodium storage performance. Small. 2017;13:1700129.10.1002/smll.201700129Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(26) Tebyetekerwa M, Xu Z, Yang S, Ramakrishna S. Electrospun nanofibers-based face masks. advanced fiber. Materials. 2020;2:161–6.10.1007/s42765-020-00049-5Search in Google Scholar

(27) Purwar R, Goutham KS, Srivastava CM. Electrospun sericin/PVA/clay nanofibrous mats for antimicrobial air filtration mask. Fibers Polym. 2016;17:1206–16.10.1007/s12221-016-6345-7Search in Google Scholar

(28) Molnar K, Jedlovszky-Hajdu A, Zrinyi M, Jiang S, Agarwal S. Poly(amino acid)-based gel fibers with pH Responsivity by coaxial reactive electrospinning. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2017;38:1700147.10.1002/marc.201700147Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(29) Jiang S, Helfricht N, Papastavrou G, Greiner A, Agarwal S. Low‐density self‐assembled poly(N‐isopropyl acrylamide) sponges with ultrahigh and extremely fast water uptake and release. Macromol rapid Commun. 2018;39:1700838.10.1002/marc.201700838Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(30) Agarwal S, Jiang S, Chen Y. Progress in the field of water‐and/or temperature‐triggered polymer actuators. Macromol Mater Eng. 2019;304:1800548.10.1002/mame.201800548Search in Google Scholar

(31) Gao J, Yuan Y, Yu Q, Yan B, Qian Y, Wen J, et al. Bio-inspired antibacterial cellulose paper–poly(amidoxime) composite hydrogel for highly efficient uranium(vi) capture from seawater. Chem Commun. 2020;56:3935–38.10.1039/C9CC09936KSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

(32) Lv D, Zhu M, Jiang Z, Jiang S, Zhang Q, Xiong R, et al. Green electrospun nanofibers and their application in air filtration. Macromol Mater Eng. 2018;303:1800336.10.1002/mame.201800336Search in Google Scholar

(33) Liang Y, Kim S, Yang E, Choi H. Omni-directional protected nanofiber membranes by surface segregation of PDMS-terminated triblock copolymer for high-efficiency oil/water emulsion separation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:25324–33.10.1021/acsami.0c05559Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(34) Kim J, Chan Hong S, Bae GN, Jung JH. Electrospun magnetic nanoparticle-decorated nanofiber filter and its applications to high-efficiency air filtration. Env Sci Technol. 2017;51:11967–75.10.1021/acs.est.7b02884Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(35) Zhang M, Ma W, Cui J, Wu S, Han J, Zou Y, et al. Hydrothermal synthesized UV-resistance and transparent coating composited superoloephilic electrospun membrane for high efficiency oily wastewater treatment. J Hazard Mater. 2020;383:121152.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121152Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(36) Ma W, Zhang M, Liu Z, Kang M, Huang C, Fu G. Fabrication of highly durable and robust superhydrophobic-superoleophilic nanofibrous membranes based on a fluorine-free system for efficient oil/water separation. J Membr Sci. 2019;570:303–13.10.1016/j.memsci.2018.10.035Search in Google Scholar