Abstract

Identity has become a fascinating object of exploration in various aspects of life and work, including farming. Many studies have examined the extent to which farmers reconstruct their identities, and only a limited number have evaluated the forms of negotiation from a communication perspective. Therefore, herein, we addressed this gap by analysing the identity challenges experienced by farmers in the agricultural era 4.0. A comprehensive farmer identity negotiation model was developed by conducting a multi-case study involving millennial and Generation X farmers from different regions in Indonesia. Data were collected through in-depth interviews with 16 farmers who have embraced Agriculture 4.0 across five regencies in Indonesia. The results showed that farmer identity is maintained and built through various processes, including education, outreach, affiliation, and social networking. Farmer identity negotiation also involves self-preparedness, such as developing communication competence and receiving environmental support through social connections, media, and access to information. The process of farmer identity negotiation ultimately leads to the affirmation of identity, manifesting in changes in social roles, lifestyle changes, and improved farming quality. The advent of Agriculture Revolution 4.0 has necessitated the availability of innovative information, provided access to information and communication technology, and spaces for farmer communities to improve their farming competence.

1 Introduction

As a vital food supplier for communities, the world of agriculture is undergoing a transformative phase that is leading to a decline in the number of farmers who serve as the main actors. Darnhofer et al. [1] highlighted two perspectives to explain this decline, namely ecological factors and the changing roles of farmers within the social structure of local communities. Ecologically, factors such as environmental degradation, unpredictable weather patterns, market uncertainties, and global interconnections have created a sense of uncertainty among farmers. In the ecological dimension, Wilson [2] stated that agriculture underwent a transition from a productivist regime by prioritizing productivity through the use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers. This is in addition to a post-productivist regime that emphasized food quality, environmental considerations, and a shift away from state-supported production. Aside from ecological challenges, farmers also face dynamic shifts in preferences driven by new technologies, marketing channels, social networks, and global market connections.

Numerous studies have highlighted the global decline in farmers, pointing to the uncertainty prevailing in the agricultural sector. Darnhofer et al. [1] conducted a study in Europe and observed a 20% decrease in agricultural ownership between 2003 and 2010. Similarly, Liu and Wang [3] found a decrease in the proportion of agricultural employment in underdeveloped and developing countries. Indonesia, an agricultural country, also experienced a decrease in the number of farming households, from 31.2 million in 2003 to 26.1 million in 2003 [4]. The country is also facing the issue of an ageing farming population, with 67.72% of farmers aged 45 and above, while those under 25 accounts for only 0.69%. The elevated share of labors limit the allowance into modern entities. This condition results in the obstruction of agricultural development and transformation [3]. One factor contributing to this challenge is the decreasing interest in agricultural work due to its negative reputation [5,6]. Moreover, the limited technological skills among farmers hinder their ability to adapt to the rapid technological advancements of the Industrial Revolution 4.0, exacerbating the competition faced by agricultural businesses [7]. These factors collectively present significant problems and challenges for Indonesian agriculture.

The Industrial Revolution 4.0 has also made a significant impact on the agricultural sector. In line with the shift towards a post-productivist regime and changes in the workforce structure, agriculture is undergoing a new technological revolution, which is supported by policymakers globally. This has led to the emergence of smart farming, where intelligent technologies play a crucial role in enhancing productivity and achieving greater environmental efficiency. The utilization of information technology (IT), which enables precision in agriculture, agro automation, and farm management information systems, is at the heart of smart farming. The development of IT has facilitated the integration of the Internet of Things (IoT) to become a part of the agricultural process [8]. The utilization of IoT in precision agriculture is particularly important in enhancing crop production [9]. According to Wolfert et al. [10], although technological innovation is not a new concept in agriculture, emerging technologies like the IoT, cloud computing, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to bring about transformative changes in agriculture, leading to the emergence of Agriculture 4.0.

The agricultural technology revolution brought about by Agriculture 4.0 has transformative effects on all levels of the agricultural system, ranging from traditional small-scale farming to broader modern agricultural sectors. Smart farming, incorporating drones, AI, machine learning, automation, sensors, the IoT, and other data- and science-based information technologies, will cause a cultural shift [11,12]. The advent of smart farming in Agriculture 4.0 will foster the emergence of a community of smart farmers and resources that are open to the global community, accelerating digital agricultural innovation. According to Bollini et al. [11], farmers in the era of Agriculture 4.0 are expected to be smart and adaptive. This implies that cultural changes among farmers in this era stem from improvements in technological infrastructure and the challenges they face within two interconnected ecosystems, namely digital and agricultural ecosystems. Darnhofer et al. [1] stated that farmers must confront and overcome ecological dynamics to survive. Therefore, the question arises as to who and what kind of farmers can successfully build their identity as farmers in the era of Agriculture 4.0.

Numerous studies have examined the process of identity reconstruction among farmers. However, most studies on farmer identity focus on farming identity in the forms of farm physical appearance, crops, production capacity measured by yields [13], and land management methods [14]. Xie [15] also conducted a study on the construction of farmer identities in post-productivism. Additionally, O’Callaghan and Warburton [16] conducted a narrative study that explored the challenges faced by farmers in Australia as they strive to maintain their identity within a changing cultural environment.

In Indonesia, many studies have explored the topic of farmer identity. For instance, Rahman [17] highlighted the role of technology utilization, innovations generated, and entrepreneurial practices in shaping farmer identity. Radjab [18] identified various factors that contribute to the construction of seaweed farmer identity, including internet networking and strong networks of capital and marketing established by wholesalers. However, none of these studies have specifically examined farmer identity negotiation from a communication perspective.

In terms of theory, many studies on farmer identity have employed identity theory and social identity theory as their theoretical frameworks. Shortall [19] examined how men and women in agriculture construct gender and occupational identities using the identity theory approach of Peter Burke. Groth and Curtis [14] also used an identity theory approach to examine farmer identity in relation to land tenure. Stenholm and Hytti [20] analysed the identity differences between producer and entrepreneur farmers, drawing on identity theory. Furthermore, McGuire et al. [21] investigated the role of farmer identity using a social identity theory approach. They explored how farmers’ social identities influenced their attitudes and behaviours within the agricultural context. Another theoretical approach employed in the farmer identity study is the diffusion of innovation theory by Rogers. Gray and Gibson [22] used this theoretical framework to examine the decision-making processes, networks, and identity of farmers in Kansas. Meanwhile, Riley [23] and Rahman [17] used the theory of action proposed by Bourdieu to explore how farmers negotiate their position as successful people.

In contrast to previous studies that have employed identity theory and social identity theory, this study takes a different theoretical approach by utilizing the communication theory of identity (CTI) developed by Michael Hecht. CTI is a new theory that seeks to extend identity beyond individual and social constructs by considering interactions and complementing social identity views that lie in roles and its theory with identity as relational [24]. The CTI conceptualizes identity within four frameworks: personal identity, enactment identity, relational identity, and communal identity. From the literature review, no study of farmer identity using the CTI approach was found. Therefore, by employing the CTI framework, this study aims to conduct a more comprehensive examination of the role of communication in the process of negotiating farmer identity.

Methodologically, preliminary studies tended to rely on single-case study designs. These studies primarily focused on investigating the identity of farmers within specific contexts, such as the adoption of innovative technology, entrepreneurial endeavours, or engagement in environmentalist practices. For example, Radjab [18] examined the transformation of fishermen into seaweed farmers. Rahman [17] explored the transformation process of horticultural farmers adopting commercial crops, also utilizing a single case study approach. Additionally, Gray and Gibson [22] explored the identity of farmers who embraced technology and examined their involvement in networking within the agricultural industry, employing a single case study methodology. Unlike previous studies, this study explored the negotiation of identity among distinct groups of farmers, specifically millennial and Generation X farmers. This approach allows for a comparative analysis of identity negotiation processes among farmers from different generations.

In 2020, Widiyanti et al. [25] conducted a study that drew on the CTI approach proposed by Hecht et al. [26] and the concept of self-verification by Swann Jr. and Bosson [27]. This study focused on how young farmers negotiate their identities within the context of the farmer regeneration crisis. Widiyanti et al. [25] uncovered several significant findings related to the identity negotiation process of young farmers, differences from the previous generations of farmers Y displaying different self-appearances. Widiyanti et al. [25] also compared their findings with a narrative study of identity constructed by O’Callaghan and Warburton [16].

This study provided a comprehensive exposition and discussion of the study by Widiyanti et al. [25] on the negotiation of farmer identities in the Agriculture 4.0 era. It conducted an in-depth analysis of farmer identities by exploring the narratives and experiences of two distinct generations. The first group consisted of young farmers (millennials), as partially disclosed in the findings by Widiyanti et al. [25], while the second group comprised older generation farmers who had successfully navigated their identities in the 4.0 era.

A unique perspective was adopted by considering two generations of farmers, namely millennials and older-generation farmers. The departure from previous debates about the future of agriculture is crucial, as it addresses the dynamics between young farmers, who have ambitious aspirations in the agricultural sector but lack access to essential resources like land and management held by older generation farmers [28–33]. Meanwhile, Chazali [31] stated that older farmers also possess high aspirations for enhancing their farming performance, necessitating access to technology. The result found that farmers from these two generations succeeded in negotiating their identities in the 4.0 revolution.

Based on the problem of the decrease in the number of farmers in Indonesia and the changes in the agricultural environment, this study analysed the identity gap experienced by farmers in the process of building their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0, comprehensively examined the negotiation process carried out by both young farmers and older generation farmers, and determined the interrelationships between the two generations to produce a negotiation model for farmer identity. Using a communication perspective, a negotiation model for farmer identities in the Agriculture 4.0 era was presented to determine the farmers new to the era. Theoretically, by presenting the concept and discovering how these identities are built, this study can make a practical contribution to parties interested in the changes.

This article is organized into several sections. Section 1 discusses the study background and literary review. Section 2 describes the methods, design, participants, data collection methods, and analysis. Section 3 presents the results among both young and old-generation farmers. Section 4 provides a comprehensive discussion of the results, and Section 5 gives the conclusion.

2 Materials and methods

A constructivist-interpretivist paradigm and a multiple-case study approach were employed in this investigation. The constructivist paradigm is viewed as socially constructed and shaped by individual or group experiences. It is contextually specific and varies depending on the perspectives of those involved [34]. Constructivism emphasizes subjective meanings from experiences formed through interactions with the objects of study (social constructivism) alongside historical and social norms applicable to daily activities [35]. Identity development is a complex process that involves various elements, such as positive and negative emotions, a sense of belonging, connectedness, and self-confidence. These concepts are continually evolving and hold significant importance in qualitative studies [36].

2.1 Study design

This study serves as a continuation and in-depth analysis of the investigation conducted by Widiyanti et al. [25] on young farmer identity negotiations. It incorporates narratives from older generations of farmers, which were thoroughly examined in a comprehensive multiple-case dissertation. The main focus of this study is to explain how farmers from different generations and with varying communication behaviours were able to develop their identities in the context of the Agriculture 4.0 era. This was achieved by carefully selecting multiple case studies. The present study specifically examined the forms of identity negotiation in two different generational groups of farmers. This includes millennial and Gen X farmers; these individuals belong to the younger and older generations, respectively. Millennials are a digital generation, have a strong affinity for the internet, and are skilled in multitasking and processing information rapidly. According to Venter [37], generation X prefers face-to-face communication.

It was conducted in Central Java, a region where a significant number of farmers have embraced the Agriculture 4.0 farming system. The study sites were selected by carefully considering the demographic, social, economic, and farming characteristics of the farmers. Based on these criteria, the study was conducted in five regencies in Central Java, namely Sukoharjo, Wonogiri, Karanganyar, Magelang, and Boyolali. Central Java was selected as the study location because it served as a pilot area for agricultural mechanization and digitization initiated by the Ministry of Agriculture. Similar initiatives were also implemented in other provinces, including East Java, Southeast Sulawesi, South Kalimantan, and South Sumatra [38].

2.2 Participants

The participants are categorized into two groups, namely millennial and Gen X farmers, who have embraced Agriculture 4.0. The maximum variation sampling was used to intentionally select individuals, groups, or settings that exhibit diverse characteristics. According to Creswell [35], this sampling approach allows for the inclusion of multiple perspectives and captures the complexity of the phenomenon under investigation. Benoot et al. [39] stated that maximum variation sampling can be used to develop a holistic understanding of a phenomenon by synthesizing studies that differ with respect to their design on several dimensions.

The sampling strategy employed capitalized on the inherent strength of heterogeneity by deliberately incorporating significant variations that are particularly valuable for comprehending the core aspects of the phenomenon [40]. The diverse samples were selected to gain a comprehensive understanding of the forms of farmer identity negotiation, taking into account various factors such as farming type, education level, and land area, which could potentially influence the entire process. This study involved a total of 16 participants consisting of 10 millennial and 6 Gen X farmers with various educational backgrounds, land areas, and adoption levels of the Agriculture 4.0 approach (Table 1).

Study participant table

| Participant | Education | Farm area | Adopted technology of Agriculture 4.0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Millennial Farmers | |||

| AW | Bachelor | >1 ha | Screenhouse, smart irrigation, drone, online marketing, plant tissue isolation method |

| ZR | Senior High School | <0.5 ha | Electric milking processing |

| EM | Senior High School | <0.5 ha | Organic farming, post-harvest technology (Ozonization), online marketing applications |

| AH | Bachelor | <0.5 ha | Hydroponic farming in a greenhouse, digital room temperature controller, online marketing |

| WK | Senior High School | <0.5 ha | Online marketing through social media |

| JS | Senior High School | <0.5 ha | Online marketing |

| BD | Senior High School | <0.5 ha | Organic farming, online marketing |

| ITN | Bachelor | >1 ha | Agricultural machine tool service application (smart mobile), IoT-based nutrient content test |

| RD | Bachelor | >1 ha | Online marketing |

| DS | Bachelor | >1 ha | Integrated farming, agro-tourism, online marketing |

| Gen X Farmers | |||

| HS | Bachelor | >10 ha | Integrated farming |

| PM | Senior High School | <1 ha | Manufacture of machines compatible with farmers |

| SY | Junior High School | <1 ha | Quality potato seedling |

| SR | Junior High School | <1 ha | Online marketing |

| AG | Junior High School | <1 ha | Organic farming, online marketing |

| HA | Senior High School | >1 ha | Organic farming, integrated farming, agro-tourism |

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

2.3 Data collection and analysis

The data were collected using in-depth interviews to examine the personal, enactment, relational, and communal identities of both millennial and Gen X farmers. These interviews also focused on exploring the problems or inconsistencies perceived by the participants and how they validated their identity as farmers through communication. The interviews were conducted from July 2019 to November 2020, with a duration of 75–90 min. In order to ensure data validity, each participant was interviewed three to four times.

Furthermore, in-depth interviews were conducted to thoroughly examine the personal, enactment, relational, and communal identities of participants. The data collected for personal identity included factors such as the reasons for selecting a career in farming, perceptions of agricultural work, the core values associated with being a farmer, their expectations, motivations, and views on Agriculture 4.0. Regarding enactment identity, the data collected encompassed how these individuals portrayed themselves, both personal and farming identities. This included aspects such as the adoption of technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship, as well as the challenges encountered in embracing their identities as farmers. Enacted identity refers to the validation of identity exhibited by the way the farmers express themselves, both personally (through the following attributes clothing, vehicles, houses, etc.) and within the farming domain (through technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship). Relational identity data include information on social roles, interactions, and problems in the context of adopting Agriculture 4.0. Communal identity data explored the involvement of the participants in farmer groups, associations, or other collective organizations, as well as the problems encountered.

In addition to the in-depth interview technique, data for this study were also collected by documenting the social media activities of the farmers on Instagram. The data collected on Instagram included motivations, values, and expectations of farmers, as conveyed through the captions under the images shared by the millennials, specifically those related to farming activities. The data from Instagram were collected between August 2019 and November 2020.

Data validation was carried out using two approaches, namely the triangulation method and member checking. The triangulation of data sources was performed by obtaining information from a particular informant, analysing the actual conditions, passive observation of the activities engaged in by the participants, or reviewing existing documentation such as farming records, training certificates, and awards. This approach helped ensure the reliability and accuracy of the data. The second validation method employed was member checking. This involved sharing conclusions from preliminary studies with selected participants and seeking their feedback and approval. By involving the participants in the validation process, the present study aimed to enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of its findings.

Several qualitative reliability procedures were performed to ensure the findings were reliable and consistent. Yin [41] stated the importance of documenting case study procedures and conducting study protocols and databases in a careful manner, enabling subsequent studies to follow these procedures. This study also used practical guidelines, such as interviews and passive observation guides, to facilitate data collection in a structured and consistent manner.

The analysis technique used is an explanatory approach, which involves analysing the case study data to provide explanations for the phenomenon under investigation. This process entails establishing interrelationships to understand the phenomenon and presenting the findings in a narrative form. The stages of analysis carried out are based on the five stages proposed by Yin [41], namely data compilation, disassembling, reassembling, interpretation, and conclusion (Figure 1).

![Figure 1

Data analysis stages. Source: Yin [41].](/document/doi/10.1515/opag-2022-0219/asset/graphic/j_opag-2022-0219_fig_001.jpg)

Data analysis stages. Source: Yin [41].

3 Results

The findings revealed that both millennial and Generation X farmers are well aware of the inefficiency of their family farms, leading to limited income and poor welfare. In the era of Agriculture 4.0, these two groups encountered challenges at various levels, including individual conflicts within the family, communal conflicts with other farmers, and public conflicts with stakeholders, such as consumers, authors, and other parties interested in agricultural development.

The two groups try to portray their identities by effectively managing the dynamics of interpersonal communication, whether through face-to-face communication or through various internet media. During this process, they engage in meaningful exchanges, sharing resources, and participating in social interactions. Burke and Stets [42] defined resources as all elements that support individuals and interactions.

3.1 Identity gap

An identity gap is a form of a divergent situation where farmers enforce their identity in social interaction, which leads to conflicts with other forces. Berger and Heath [43] stated that this conflict is a form of divergence, whereas Hecht conceptualizes it as an identity gap.

3.1.1 Conflict with family

Both millennial and Gen X farmers face challenges within their families, as they heavily rely on family members who act as labourers and play active roles in the farming businesses. This increased involvement of family members, including spouses and children, can sometimes lead to tension due to uncertainties surrounding farming outcomes. According to Pitts et al. [44], low profitability in farming further exacerbates succession issues in family farming. For millennial farmers, the main concern revolves around making the most out of the limited land resources. As EM, BD, and DS mentioned in their statement, “what can we do with less than a quarter hectare of land?” Some millennial farmers, such as DS and BD, express doubts about their farmer identity, feeling that they had not reaped the benefits from their farming activities and lacked trust in managing the family farms. Widiyanti et al. [25] stated that these are attributed to delays in agricultural succession. Similarly, Gen X farmers experience tensions within their families due to uncertainties and low yields. AG and PM reported that conflicts arise from waiting for uncertain yields when experimenting with new crops or farming techniques. According to one of the participants, AG:

[…]When my corn shelling business was on the brink of bankruptcy, I thought my family would be the first to be affected. This compelled me to mentally prepare myself for the challenges ahead. However, I also had to brainstorm new ways to generate income. In such difficult times, I believed that maintaining optimism was crucial not only for myself but also to inspire enthusiasm in others. (AG, 5 June 2020)

The conflicts in families over low profits are not only solely caused by financial difficulties but also by the increasing demands placed on farmers in the era of Agriculture 4.0. From this perspective, the need for internet access has become essential for farmers in this era, further widening the gap between income and expenses. Meeting these technological requirements has added to the financial strain experienced by farmers.

3.1.2 Conflict with consumer demands

Farming is an agricultural activity that requires collaboration with various parties to ensure its continuity. These parties include the input providers and the output recipients involved in the farming processes. When engaging with the market, such as traders and direct consumers, farmers face the motives and expectations of their partners, who seek product consistency, quality, quantity, and timely information. Satisfaction and convenience in obtaining agricultural products are also consumer motives. However, due to the limitations in terms of quality, quantity, and consistency resulting from small-scale operations, farmers often struggle to meet market demands. For instance, millennial farmer AW must meet specific standards in terms of potato quality and quantity to sell to food companies. Gen X farmer HA faces the challenge of meeting strict organic rice standards to access larger markets.

Xie [15] conducted a study on the new generation of farmers in China and discovered that they were aware of the need to adapt to changing consumer behaviours, which is closely associated with health and environmental issues in food production. The farmers in the study conducted by Xie [15] were also aware of the need to maintain good relationships with their consumers to sustain their businesses. In this study, one of the challenges faced by farmers is the demand for fast information services for consumers. While millennial farmers, who are proficient in digital communication, can meet this demand, it poses a problem for Gen X. Farmers SY and SR expressed concerns about consumer expectations regarding mobile phone ownership and the use of WhatsApp social media. In the digital era, particularly in online marketing, the study stated that issues with consumers go beyond product quality, quantity, and continuity. The connection of farmers with internet-based communication media is vital for creating networks that bring them closer to consumers.

3.1.3 Relationship gap with researchers

The agricultural sector, being crucial in supplying food to the community, attracts various stakeholders. The studies conducted by universities and companies actively contribute to its development by validating technology and innovation. Additionally, universities depend on farmers and their surroundings to provide practical learning opportunities for students, such as field-based programs like Student Community Service (KKN) activities, internships, and study initiatives.

The presence of universities and companies in the agricultural sector brings about new relationships and also gives rise to identity gaps, particularly concerning the limited technology proficiency of Gen X farmers. This situation necessitates farmers to navigate and negotiate their identities. For example, farmer SR was approached by the university research department with an offer to collaborate with them on creating processed flour from vegetables. A similar incident occurred with farmer SY, who was invited by the same department to participate in studies on plant-cutting development.

The first time I used WhatsApp was at the request of a professor. They wanted me to download the app so that we could easily exchange photos of crop development… And it turns out that eventually, I realized I also have to send photos of my harvest to the traders. It became a way for me to showcase our products to potential buyers and traders. (SY, 21 June 2020)

Millennial farmers, such as DS and AW, were also invited by the seed and drone companies to participate in study activities. These invitations required these individuals to be proficient in new farming technologies and information. However, millennial farmers face certain challenges due to their limited land area. This obstacle is overcome by establishing networks and collaborating with other farmers to access additional land for study purposes.

3.1.4 Conflict among farmers

Gen X farmers faced conflicts with their colleagues due to differences in IT and innovation adoption. Farmer SY encountered skepticism from other farmers regarding his successful potato harvest. According to SY, “When we planted potatoes with good seeds, other farmers commented that successful potato farming could only be realized by skilled farmers” (SY, June 21, 2020). Additionally, social jealousy emerged among farmers, specifically when SY partnered with universities and seed companies. SY stated that “When other farmers were asked to cooperate, they were reluctant. and after they were informed of how I got some facilities like the screen house, they became noisy…” (SY July 20, 2020).

Burke and Running [45] conducted a study on the influence of collective identity on the environmental attitudes and behaviours of farmers. Their findings revealed a significant presence of distrust and competition among these individuals and farmer groups, particularly in the pursuit of identity recognition. It was noted that conflicts of interest arising from resource exploitation, such as water, contribute to the prevailing sense of mutual distrust.

3.1.5 The view of society towards the farmer profession

The most challenging identity gap that millennial farmers face is the negative view towards this occupation. This negative perception leads to tensions in their relationships within the community and differential treatment when accessing public services. Farmer ITN encountered this problem when applying for a capital loan at a financial institution, as the profession was deemed unreliable for financing. According to ITN, “Yesterday, I applied for a loan, and it was rejected because I am only a farmer, and the nominal amount was quite large. I needed to purchase a 4-wheeled tractor” (ITN, 6 August 2020). This negative perception extends beyond financial institutions and affects personal relationships as well. ITN stated that people often judge the credibility of an individual based on income, further exacerbating the low social status associated with being a farmer. The desire to challenge and change the perception of farmers' low social status is a common sentiment among beginner farmers, as stated in the study by Xie [15] conducted in China. The work of farmers in China is often marginalized, with low social status attributed to their limited income.

3.2 Farmer identity negotiations

In this study, it was discovered that millennial and Gen X farmers employed different forms of negotiation to address the identity gaps they encountered with various parties (negotiation partners).

3.2.1 Education, socialization, and affiliation

Both millennial and Gen X farmers are taking proactive steps to address conflicts with their families stemming from limitations in their farming businesses. One approach employed was improving their farming skills through education, outreach, and affiliations. Millennial farmers improved their farming skills through two educational channels, namely formal agricultural education as practiced by AW, AH, DS, and ITN, and non-formal education realized through training, apprenticeships, and seminars. Meanwhile, Gen X farmers participate more in non-formal agricultural education, such as training activities held by various parties like the Agriculture Office and Plantations Service, agricultural companies, and academics from tertiary institutions which organize outreach activities in their villages. Five of the six Gen X farmers, namely PM, SY, SR, AG, and HA, actively participated in the non-formal education. Meanwhile, HS being highly digitally literate, does not actively engage in extension activities. Rodriguez-Lizano et al. [46] and Tolinggi et al. [47] reported that non-formal education plays a crucial role in the succession of family farming businesses. Both millennial and Gen X farmers establish associations or affiliations aligned with their agricultural goals, seeking support and guidance from professional farmer groups. Widiyanti et al. [25] stated that it is referred to as finding the right environment. The 16 millennial and Gen X farmers joined various professional farmer groups to find solutions to overcome their problems. Participant ZR, for instance, shared how they were introduced to these farmer groups by their parents, marking the beginning of his farming journey.

Initially, my father introduced me to livestock associations and farmer groups, where I learned a lot from my friends. One notable experience was attending a training program on animal feed production organized by the livestock association in Lembang. Presently, I have actively participated in three different farmer groups, namely at the village-level associations, inter-subdistrict collaborations, and a group facilitated by Bank Indonesia. (ZR, July 20, 2019)

Millennial farmers AW and WK, as well as AH, EM, and BD, are actively involved in business incubators to foster the development of their farming businesses. They become members of the millennial farmer community and the business learning community. Similarly, Gen X farmers also adopted similar strategies. For instance, farmer SY is part of a company-assisted farmer association, while PM and HA participated in organic farming study groups. They have also taken the initiative to establish study groups, as shared by SR.

Those interested in online marketing finally gathered to study together… from flipping through their cellphones and the internet to becoming a study group… In fact, presently, we are like a family and tend to support each other. (SR, July 21, 2019)

3.2.2 Collaboration and partnership for technology, innovation, and added value

The presence of smart farming in Agriculture 4.0 has brought new opportunities for millennial farmers, shedding light on the potential changes it can bring to their farming businesses. These farmers have realized that smart farming technologies can simplify their work, save energy, and increase productivity, allowing the allocation of more time to hobbies and personal interests. Additionally, the expanding reach of social networks has opened up numerous business prospects for millennial farmers in the agricultural sector. Radjab [18] and Rahman [17] also reported that social networks play a significant role in the transformation process of farmers. According to Radjab [18], social networks, including acquaintances, family connections, non-governmental organizations, and communication platforms, positively impact capital and marketing networks with similar results obtained in this study. By leveraging these social networks, farmers can actively participate in the agricultural business value chain, breaking away from the limitations of focusing solely on their farmland. This allows them to explore alternative income streams within the agricultural sector and move closer to achieving prosperity. In order to overcome limitations and build trust in their farming businesses, millennial farmers have been forming partnerships and collaborations while embracing the concepts of Agriculture 4.0. They leverage these alliances to access capital, collaborate with entrepreneurs for creative ideas, and partner with companies that can facilitate the implementation of desired technologies. For instance, AW had to cooperate in terms of obtaining capital for their farming businesses, while ITN and their team collaborated on designing digital technology for nutrient detection equipment.

I have partnered with a personal agent who is a billionaire… This partnership is particularly beneficial for my nursery business as it grants me access to a substantial amount of capital. (AW, 27 January 2020)

In the beginning, the venture was purely embarked on for enjoyment. We harboured a strong desire and shared it with BI, and to our delight, they expressed their interest and willingness to collaborate. As a result, we assembled a team of five individuals with expertise in their respective fields to undertake the project. (ITN, 6 February 2020)

Gen X farmers, like participant SY, are seizing opportunities to collaborate with investors, furthering their agricultural ventures and achieving success in their endeavours. Gen X farmers also collaborated with investors. According to participant SY.

I the experience of work with investors from Jogja. One day, four young men aged 27 years approached me and proposed a partnership system, which I gladly accepted. (SY, 20 July 2019)

Many millennial and Gen X farmers are actively involved in enhancing the value of their agricultural products, alongside collaborating with stakeholders to obtain capital and technology. One notable example is participant EM and their group, who have made organic farming and effective packaging their focal points. By prioritizing these aspects, they are able to successfully enter the modern market with their vegetable products.

Taking the lead in this endeavour, my friends and I proactively approached the farmers and presented our proposition. Recognizing the significance of motivation, we emphasized the benefits of organic farming and assured them of our commitment to market their crops… Through extensive discussions and consultations, we collectively identified the potential commodities in the local agricultural sector, explored ways to enhance farming practices, and sought to empower conventional farmers by adding value to their produce. Finally, we formed the Mutiara Organik farmer group. (EM, July 21, 2019)

I am currently engaged in a project focused on vegetable flour, working alongside students and lecturers from Tidar University, ma’am… It all began when they were conducting their field community service here. I challenged them to work on this project, aiming to provide additional value to vegetable farmers like myself. (SR, July 21, 2019)

The adoption of Agriculture 4.0 by millennial farmers is marked by distinct characteristics. These include implementing modern farming practices, fostering institutional and marketing innovations, prioritizing product quality and added value, and embracing farming diversification as a means of managing risks. The decision of millennial and Gen X farmers to farm organically is a form of farming quality improvement and climate change mitigation. This finding aligns with Līcīte [48] that organic land management is a form of climate change mitigation and appropriate future land management practices aimed at enhancing soil nutrient availability [49–51]. It differs from the study conducted by Xie [15] that organic production and the establishment of direct relationships with consumers are two essential characteristics that distinguish new farmers in China from conventional ones from previous generations. Another different finding was reported by McGuire et al. [52], who found that farmers made efforts to build their identity through intensive agricultural management practices with a strong focus on business strategies to maximize yields and efficiency.

3.2.3 Learning communication technology to enter Interface 4.0

In order to overcome the hurdles posed by communication technology stuttering, Gen X farmers must familiarize themselves with Android devices and learn to utilize communication technologies effectively. Mastering mobile phone communication, particularly through platforms like WhatsApp, becomes essential for farmers to expand their farming businesses. By using WhatsApp, they can engage in seamless communication with their relatives and partners, exchanging product images and implementing various visual marketing strategies through the sharing of photos and videos. Engaging in social media platforms also plays a significant role in enhancing farmers’ identities and strengthening their connections. For example, farmer SY struggled to understand how to communicate through WhatsApp. However, with perseverance, SY gradually grasped the workings of WhatsApp communication and successfully established meaningful relationships with both relatives and partners. Similarly, farmer SR benefited from social media platforms as responses were received from individuals with greater expertise or knowledge while also gaining recognition and appreciation for the crops cultivated. The following accounts highlighted the experiences of Gen X farmers as they embarked on the learning journey of using social media.

Through interactions with students who interned at my farm, I gained valuable knowledge on capturing photos and videos of plants and uploading them to my WA status… (SY, 21 June 2020)

I learned about online marketing from the youngsters at Eight Indonesia, ma’am… Then I became interested in buying an android… Now I am addicted… (SR, 21 July 2019)

3.2.4 Playing social role

In response to negative views about agricultural work, both millennial and Gen X farmers feel compelled to showcase their distinctiveness. AW, a millennial farmer, stands out by demonstrating modern farming practices and positioning not just as a farmer but also as an entrepreneur (agropreneur). Moreover, AW assumes the role of a village influencer, mobilizing fellow youths to contribute to the development of the community. This farmer is also a sociopreneur who actively engages as a resource person in various forums. This transformation of identity was not unique to AW but was also observed among other millennial farmers, such as WK, JS, and ITN, who gradually redefined themselves within the agricultural landscape. According to millennial farmer AW.

I combined sociopreneur with agriculture. My focus is not solely limited to farming but rather on using agriculture as a tool that is beneficial to others. When organizing workshops for friends, I passionately share insights on how individuals can become sociopreneurs in their respective fields, emphasizing the importance of creating positive impacts and contributing to the betterment of others. (AW, July 21, 2019)

Gen X farmers also undergo significant identity transformations as they navigate the agricultural realm. For example, they play a number of social roles in overcoming conflicts with fellow farmers due to gaps in access to technology. These farmers also act as mediators and self-help extension agents for their colleagues. Farmer PM is perceived as a self-supporting extension worker for other farmers, specifically in agricultural mechanization. HS and SY perceive themselves as agents of change, actively transferring knowledge to other farmers, specifically in the aspect of integrated farming. Additionally, HA fulfils the role of an organic farming instructor. This individual provides further insight into their social role and its significance within the farming community.

Actually, I am a motivator who shares the inspiring stories of successful farmers. I am an open-minded person who has an insatiable thirst for knowledge. I derive immense joy in welcoming people from all walks of life to share their wisdom and experiences… Because we still have much to do to improve our farming methods for the advancement of agriculture. (HS, 1 December 2019)

This study highlights the multifaceted nature of the social roles played by farmers, which not only aim to combat negative views and improve their social standing but also serve as a means to resolve conflicts within the community. Bourdie, as cited in Riley [23], stated that the social contacts, networks, skills, and knowledge of farmers are perceived as their social and cultural capital. Bourdie stated that, in constructing their identity, farmers not only focus on economic but also on social (derived from and reinforced by social contacts and networks) and cultural capitals (skills, knowledge, and dispositions acquired through education and social interactions). This argument aligns with the statement made by Shortall [19] that the identity of farmers is influenced by their social relations and interactions.

3.2.5 Changing appearance

This study examined how Millennial and Gen X farmers differentiated themselves from traditional farmers through their unique self-presentation. A notable aspect of the millennial farmers is their deliberate selection of distinct attire when working on their lands, such as clothing resembling workshop wear, mountain hats, and boots. Gen X farmers SY, HA, and HS also embraced this dress code when heading to the fields. In addition to their attire, these farmers use personal symbols such as branded items like watches, cellphones, and clothing to further enhance their self-presentation. Xie [15] stated that even in China, new farmers differentiated themselves from their traditional counterparts by embracing a specific lifestyle, thereby constructing an elite discourse around their identity.

3.2.6 Improving self-image through social media

In an effort to dispel the perception that farmers are confined to working on the land and dealing with mud, numerous millennial farmers use social media platforms to establish their distinct identities. They craft detailed biographies on their social media accounts, providing glimpses into their lives that showcase how they differ from the conventional farmer. These posts feature a range of photographs capturing their activities on the land, participation in training sessions, seminars, and workshops, as well as their achievements and personal milestones. Moreover, they frequently upload videos that exhibit their work in the fields, the process of harvesting crops, and their adeptness in operating agricultural machinery. By accompanying these visual elements with captions that reflect their self-concepts, such as their life motivations, farming aspirations, and desire to make a positive impact on society, they assert themselves as millennial farmers who embrace uniqueness. Through the medium of social media, individuals like farmer AW aim to demonstrate their divergence from the norm, while farmer ITN strives to present the positive aspects of the farming profession to a wider audience.

I always record every progress of my potato plants, from seeding to harvesting. I upload every stage of its growth through stories on Instagram and WhatsApp. So when I go to the field, I always remember to bring my cell phone… By showing my farming methods on Instagram stories, I want to show the general media that I am a farmer and that my farming method is different from others because I have used innovations. Besides that, I also do this to brand my Agrolestari Merbabu in a modern way… (AW, 3 January 2020)

Farming is a learning process. It’s learning God’s language, the weather conditions, and the crops suitable for the conditions of the land… In farming, we manage our own time. We have more time to worship and gather with family. Farming is about a better life, starting with what we plant. (ITN Instagram, 25 July 2020)

Gen X farmers are following in the footsteps of their millennial counterparts by using social media to shape their self-image. Farmer HS showcases a multitude of groundbreaking endeavours in integrated farming. Meanwhile, farmer SY focuses on sharing the outcomes of his potato nursery, employing various crossbreeding techniques. Farmer PM exhibits cost-effective modifications made to agricultural machinery, ensuring accessibility for fellow farmers. The works showcased on their social media accounts serve as a medium to convey messages pertaining to their intellectual growth. The following excerpt is the social media experience of SY.

At first, I was just scrolling through WhatsApp status, then I encouraged myself to upload my potato plants, I also made comments, and apparently, my comments were replied to. It turns out that WhatsApp can be used to greet each other and share information. When I posted about my last harvest, many people commented on it and wanted to learn from me. (SY, 21 July 2020)

In their study on female farmers, Daigle and Heiss [53] discovered that social media plays a pivotal role in the construction of the identities of farmers by enabling them to share their accomplishments. The study highlighted that female farmers, in addition to engaging with consumers, gathering agricultural information, and maintaining emotional connections with their peers, also leverage social media platforms to enhance their media literacy and effectively promote their success in the field of agriculture.

3.3 Communication competence and environmental support

The negotiations conducted by millennial and Gen X farmers demonstrate their possession of effective communication competencies that empower them in agriculture. These competencies include (a) Possessing a strong drive to bring about improvements in their agricultural practices. (b) Actively gathering and analysing relevant information, enabling them to identify the challenges and potential opportunities associated with agriculture in their farming operations 4.0. (c) Having identity flexibility in the form of exhibiting openness to new experiences. (d) Showing courage and confidence in establishing new relationships. (e) Demonstrating emotional sensitivity and empathy in dealing with conflicts or tension in their relationships., and (f) Proficiency in IT tools, empowering them to process and interpret the messages and data they receive efficiently.

In the identity negotiation process, environmental support is also present. This support includes (a) social support in the form of farmer communities or groups, joint study groups, and opportunities provided by formal and non-formal educational institutions to acquire knowledge, skills, and access to agricultural technology and innovation; (b) media support encompasses the availability and accessibility of information and communication media technology; and (c) information support in the form of information about existing technologies an\d innovations.

3.4 Negotiation output

The identity negotiations among farmers in the two-generation group cases yielded several notable similarities, namely, (a) both generations experienced an enhanced sense of identity through the assumption of multiple social roles. (b) The improved welfare and comfort in their work led to lifestyle modifications for the farmers. (c) Technological advancements and innovative practices contributed to improvements in farming quality, productivity, efficiency, and added value. (d) Collaborative efforts and partnerships were pursued to diversify and enhance the quality of their farming businesses. In the context of the CTI, the farmers underwent changes in their personal layer. This included shifts in their mindset towards economic, social, and ecological agriculture. Consequently, they embraced technology, innovation, and agricultural diversification, thereby altering the presentation of their farming identity. Their relational layer flourished, motivating them to establish extensive networks. Collectively, they identified themselves as agropreneurs, sociopreneurs, influencers, opinion leaders, and agents of change within their community.

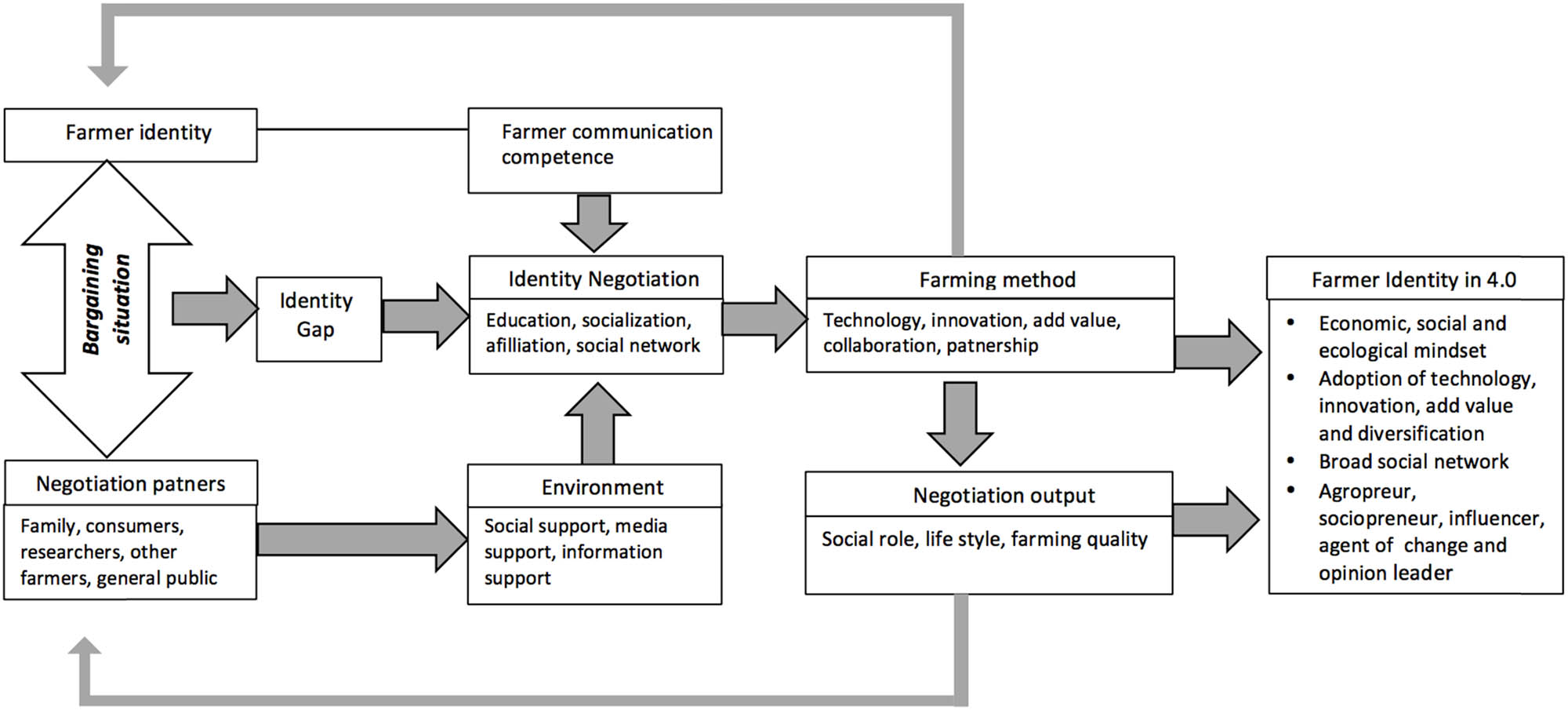

3.5 Farmer identity negotiation model

In the process of undergoing identity shifts, farmers encounter situations and external forces that either attract or clash with their farmer identity, necessitating the negotiation of their identity. The two groups of farmer generations effectively navigate these conflicts through diverse negotiation efforts, leading to the emergence of new forms of identity. Therefore, the following statements outline a model of farmer identity negotiation in the era of Agriculture 4.0:

Farmer identity negotiation is a dynamic process that addresses identity gaps arising from inconsistencies between personal identities, enactment identities, relational identities, and communal identities, or conflicts with other forces incongruent with the identity embraced by farmers.

In the process of farmer identity negotiation, identity is nurtured and constructed through social interactions with others, such as through education, outreach, affiliation, and social networking.

Farmer identity negotiation in the Agriculture 4.0 era involves both self-preparedness in the form of communication competencies and environmental support in the form of social, media, and information support.

Farmer identity negotiation strengthens their sense of identity through the adoption of new social roles, lifestyle adjustments aligned with improved welfare and societal roles, and advancements in farming methods that enhance quality. The incorporation of various social roles, lifestyles, and farming practices reinforces the identities of millennial and Gen X farmers and distinguishes them from traditional farmers (Figure 2).

An intergenerational farmer identity negotiation model in the era of Agriculture 4.0 revealed in this study.

4 Discussion

The implementation of agricultural 4.0 practices in Indonesia, promoted by the government in 2015, led to the emergence of adaptive millennial and Gen X farmers. This study demonstrates that farmer identity has undergone transformations through the negotiation process within the Agriculture 4.0 era. The study presents a communication-based perspective on farmer identity negotiation using the CTI framework. Based on the study findings, four propositions regarding farmer identity negotiation can be inferred. First, farmer identity negotiation is a crucial process aimed at bridging identity gaps that arise when identities collide with incongruent external forces. Additionally, the study reveals instances of interpenetration between different layers of farmer identity. For instance, farmers overcome limitations in farming scale (enactment layer), knowledge, and skills (personal layer) by establishing social networks (relational layer) to enhance agricultural literacy (personal layer). They also engage in collaborations and partnerships to access technology and pursue business diversification (enactment layer). In instances of conflicts within their families or communities (relational layer), farmers address them by improving farming performance (enactment layer) and showcasing their identity as members of specific groups (communal layer). These actions allow farmers to overcome family conflicts and establish distinct boundaries that set them apart from traditional farming groups in terms of social roles, lifestyle, and farming qualities.

Second, farmers maintain and develop their identity through social interactions during educational, outreach, affiliation, and social networking activities, in order to achieve a balanced sense of identity. Third, the process of negotiating farmer identity involves the preparedness of farmers in terms of their communication competencies. It is essential to connect them with knowledge and technology resources, emphasizing the importance of providing social, media, and information support. Social support can come in the form of opportunities for knowledge acquisition, skill development, and access to agricultural technology and innovation, facilitated by formal and non-formal educational institutions (such as training programs, apprenticeships, and business incubators), farmer communities, and study groups [54–57]. Media support includes ensuring the availability and accessibility of information and communication technology (ICT) [58], particularly in this digital era. Widiyanti et al. [59,60] reported that internet infrastructure plays a crucial role in connecting farmers with online communities and diverse sources of knowledge. Information support entails providing farmers with relevant information about compatible technologies, innovations, and other resources they need.

Fourth, the negotiation of farmer identity strengthens their sense of self through various means, including assuming social roles, adapting their lifestyle to improved welfare and social responsibilities, and enhancing the quality of their farming practices. Widiyanti et al. [61] stated that the adoption of agricultural technology serves as a means for farmers to increase their income and social status. According to Akimowicz et al. [62], applying agricultural technology is an effort to increase income and social status. Akimowicz et al. reported that these identity negotiations involve balancing work quality and personal sacrifices as farmers navigate changes in their lifestyles. In the context of Agriculture 4.0, the reinforcement of farmer identity signifies the development of several competencies, such as understanding agriculture as a system, organizational skills, the ability to analyse farming and market dynamics, problem-solving abilities, creativity in seizing opportunities, proficiency in building partnerships and collaborations, and effective communication skills. These competencies encompass openness, courage, confidence, motivation, flexibility, optimism, empathy, and mastery of ICT.

In addition to identifying similarities in the negotiation processes, this study also aimed to identify differences in the negotiation processes in order to formulate a comprehensive negotiation model for the two cases. The main variations lie in the contexts or situations where the identities of farmers need to be negotiated. Millennial farmers predominantly negotiate their identities with their consumers and close friends at the public level, whereas Gen X farmers negotiate their identities more with university scholars or researchers from agricultural companies. At the communal level, this study found that Gen X farmers negotiate their identities within farmer groups and among fellow farmers. This disparity arises from information gaps among Gen X farmers, leading to varying levels of identity construction. In contrast, millennial farmers do not engage in negotiation at the communal level as they identify themselves with broader groups. Millennial farmers exhibit a high mastery of ICT, eliminating any information gaps. This highlights the crucial role of access to IT in the identity construction process for farmers.

This study presents distinct findings from the research by Xie [15] on the formation of new farmer identities in China as well as O’Callaghan and Warburton [16] on identity construction among older-generation farmers in Australia. A previous study has emphasized the formation of farmer identities through human factors such as attitudes, perceptions, values, experiences, and behaviours. These factors contribute to developing farmer identities aligned with a more sustainable and healthy food-producing system [15]. In contrast to the findings of Xie [15], this study reveals that millennial and Gen X farmers, in addition to pursuing a healthy and sustainable food system, are progressive, and strive to optimize their farming businesses by enhancing productivity, efficiency, and diversification of agricultural enterprises. The formation of the identities of millennial farmers involves efforts to challenge negative stereotypes associated with farmers and foster positive perceptions instead.

This study also reported a shift in the communal identities of farmers. It is worth noting that some experts often regard communal and social identities as closely intertwined concepts [63]. This awareness has encouraged farmers to change their self-concept, farming practices, and lifestyle. Developing networks is a strategic approach Gen X farmers employ to overcome negative self-concepts. This phenomenon indicates a shift in the social identity of farmers. Initially, the identity of the farmer was primarily shaped by certain factors such as land ownership, physical strength, and the time spent working on the land [16]. The current emphasis lies on their social networks and roles within society. Contemporary farmers derive greater pride from being recognized as experts in specific fields. For example, participant HS is known as an integrated farmer, while SY derives joy in being known as an expert in potato nurseries. This shift highlights the increasing significance of mastery as a motivational factor for individuals pursuing a career in farming.

The transformation in the identity of Gen X farmers has led to a shift in their investment strategies. Instead of solely focusing on expanding their farms by investing in land assets, farmers are prioritizing social investments, such as developing strong social networks and investing in innovative technologies to maximize their endeavours. Several factors contributed to this change in the communal identity among Gen X farmers. One key factor is the evolving knowledge systems within the farming community, in which changes have influenced social interactions among fellow farmers and the millennial generation. Additionally, the presence of new media platforms has played a significant role in shaping the perspectives of farmers. Finally, the agricultural system has undergone transformations due to the Industrial Revolution 4.0, further prompting farmers to adapt their investment strategies accordingly.

Other findings on communal identity show that the area of land owned does not affect the adoption of agriculture 4.0 practices. In order to overcome the limitations posed by smaller land areas, farmers have employed various strategies. These included collaborating with fellow farmers, actively seeking opportunities to enhance value, and using their communication skills and extensive networks to establish partnerships with diverse stakeholders. These findings challenge the prevailing notion put forth by Rogers [64] that higher income levels and larger land areas typically characterize innovations. It highlights the importance of competencies such as the ability to effectively process information from multiple sources instead of solely relying on income or land size in driving innovation and adoption within the farming community.

In addition to introducing new findings, this study supports several existing investigations on farmer identity. One significant trend observed among millennial and Gen X farmers is their intentional focus on enhancing the visual aspects of their farming businesses to strengthen their identities. Such a phenomenon was also found in the study by Riley [23], where the visual appearance of farmers is one of the key factors influencing the construction of farmer identity. The present study revealed some nuanced differences in terms of compromises made in relation to agricultural machinery skills. While the study by Riley primarily highlighted that older farmers were more likely to make compromises in this regard, the current one reported that many millennial farmers also make compromises in terms of their proficiency with agricultural machinery.

The results of this study are in line with the findings of McGuire et al. [21], who identified a feedback loop between desirable farmer roles, social identity, and behavioural changes towards conservation management. In a similar vein, this study uncovered a feedback loop between the importance of agriculture, social identity, and behavioural changes observed among millennial and Gen X farmers towards adopting innovative agricultural practices aimed at optimizing yields and promoting environmental sustainability.

This study supports the findings of Xie [15] regarding new farmer identity in the post-productivism era. It reported that these individuals are actively engaged in reinforcing their identities by establishing new boundaries to distinguish themselves from the stereotypes associated with traditional farming while promoting discourses of being elite farmers. In the present study, farmers accomplished this differentiation by assuming various social roles, such as sociopreneurs, agropreneurs, and influencers. This finding also complements the observations made by Xie [15] regarding the new generation of farmers, who perceive themselves as versatile individuals referred to as jacks of all trades. Similarly, the millennial farmers in this study also embrace this multifaceted self-perception, as evidenced by their adoption of multiple identities.

This study has identified both limitations and opportunities for future investigations. Although it sheds light on the transformation of farmer identity, it should be noted that the role of stakeholders who interact with farmers and contribute to these identity changes has not been extensively examined. While this study delves into the personal and social identity shifts experienced by farmers, particularly in their work identity as they transition from conventional and traditional agriculture to Agriculture 4.0, there are still avenues for future exploration. Specifically, future studies could investigate the impact of stakeholders on the changes in farmer identity. This would involve examining how external factors and interactions shape and influence the evolution of farmer identity. Exploring the broader implications of these identity changes, such as the potential shifts in the social class of farmers following the implementation of Agriculture 4.0, presents an intriguing avenue for further investigation.

The importance of communication competence highlights the necessity for further studies exploring the competitive nature of farmers in other aspects. These should encompass the broader spectrum of managing farming as a business within the context of the agricultural ecosystem 4.0. Additionally, the identification of farmer competencies in the present study serves as a foundation for a future investigation aimed at modelling the enhancement of these attributes and developing non-formal education curricula that could effectively improve the skills of farmers, enabling them to become more adaptive and professional in their agricultural practices.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, being a consistent farmer in the era of Agriculture 4.0 poses significant challenges because the concept of farming is no longer static but adaptable to the prevailing context. Farmers encounter numerous obstacles in maintaining their identity, both internally, such as identity conflicts, and externally, in their interactions with other stakeholders in the agricultural system. These challenges encompass heightened consumer awareness of food quality, evolving internet-based communication systems, and establishing new relationships with other interested parties in agriculture. Consequently, farmers find themselves in a constant struggle, negotiating their identities amidst these challenges. This study finds the correlation between farmers and knowledge and technology sources in the process of maintaining and enhancing their identity. The connectedness of farmers with these sources of knowledge and technology leads to the adoption of various social roles and the development of social networks that impact their identity changes. Therefore, it is crucial to provide farmers with support in terms of information communication technology, access to IT, and innovative agricultural practices. This study offered practical implications concerning farmers’ competence in the era of Agriculture 4.0. These implications underscore the organizational skills, problem-solving abilities, creative thinking skills, partnership building, collaboration, and effective communication of farmers. They are encouraged to be open, courageous, confident, highly motivated, flexible, optimistic, empathetic, and proficient in mastering ICT. To address these needs, agricultural programs should prioritize farmer capacity building through training, apprenticeships, and the promotion of learning communities. Additionally, expanding farmer extension services and support through social media platforms is essential for disseminating information and assisting farmers in adapting to the evolving agricultural landscape in the digital era.

Nomenclature

- Bargaining situation

-

a tug-of-war situation when an identity is raised or enforced

- Farming quality

-

a more quality way of farming seen from its productivity, level of efficiency and pro-environmental

- Identity gap

-

a clash between the identities that are enforced

- Information support

-

support in the form of the availability of information on agricultural technology, innovation, markets, capital, and other information needed by farmers.

- Media support

-

support in the form of information and communication media accessibility

- Millennial farmers

-

the generation of millennial farmers born around 1980–1995

- Identity negotiation

-

efforts made to find a balance of identity or efforts to overcome identity issues.

- Negotiation partners

-

other parties who conflict or are not in line with the farmer’s identity.

- Gen X farmer

-

the older generation of farmers born between 1965 and1976.

- Social support

-

support that comes from the primary (family) and secondary (community) environment

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the young farmer participants and all those who assisted with this project.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Emi Widiyanti: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. Ravik Karsidi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Mahendra Wijaya: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Prahastiwi Utari: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Darnhofer I, Lamine C, Strauss A, Navarrete M. The resilience of family farms: Towards a relational approach. J Rural Stud. 2016 Apr;44:111–22.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.01.013Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Wilson GA. The Australian Landcare movement: towards ‘post- productivist rural governance?. J Rural Stud. 2004 Oct 1;20(4):461–84. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2004.03.002Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Liu S, Wang B. The decline in agricultural share and agricultural industrialization—some stylized facts and theoretical explanations. China Agric Econ Rev. 2022 Aug;14(3):469–93.10.1108/CAER-12-2021-0254Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Syahyuti nFN. Relevansi Konsep dan Gerakan Pertanian Keluarga (Family Farming) Serta Karakteristiknya di Indonesia. Forum Penelit Agro Ekon. 2016;34(2):87–101.10.21082/fae.v34n2.2016.87-101Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Page C, Witt B. A leap of faith: Regenerative agriculture as a contested worldview rather than as a practice change issue. Sustainability. 2022 Nov;14(22):14803 [cited 2023 Jan 8]. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/22/14803/htm.10.3390/su142214803Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Firman A, Budimulati L, Paturochman M, Munandar M. Succession models on smallholder dairy farms in Indonesia. Livest Res Rural Dev. 2018;30(10):176.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Putri Febrianti V, Alya Permata T, Humairoh M, Mulyana Putri O, Amelia L, Fatimah S, et al. Analisis pengaruh perkembangan teknologi pertanian di era revolusi industri 4.0 terhadap hasil produksi padi. J Pengolah Pangan. 2021 Dec;6(2):54–60 [cited 2023 Jun 25]. https://www.pengolahanpangan.jurnalpertanianunisapalu.com/index.php/pangan/article/view/50.10.31970/pangan.v6i2.50Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Rajak ARA. Emerging technological methods for effective farming by cloud computing and IoT. Emerg Sci J. 2022 Aug;6(5):1017–31 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. https://www.ijournalse.org/index.php/ESJ/article/view/1174.10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-05-07Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Wayangkau IH, Mekiuw Y, Rachmat R, Suwarjono S, Hariyanto H. Utilization of IoT for soil moisture and temperature monitoring system for onion growth. Emerg Sci J. 2021 Oct;4:102–15 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. https://www.ijournalse.org/index.php/ESJ/article/view/695.10.28991/esj-2021-SP1-07Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Wolfert S, Ge L, Verdouw C, Bogaardt MJ. Big data in smart farming – A review. Agric Syst. 2017 May;153:69–80.10.1016/j.agsy.2017.01.023Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Bollini L, Caccamo A, Martino C. Interfaces of the agriculture 4.0. In WEBIST 2019: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies; 2019. p. 273–80 [cited 2023 Jan 8]. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2045-6385.10.5220/0008164800002366Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Javaid M, Haleem A, Singh RP, Suman R. Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. Int J Intell Netw. 2022 Jan;3:150–64.10.1016/j.ijin.2022.09.004Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Fischer H, Burton RJF. Understanding farm succession as socially constructed endogenous cycles. Sociol Ruralis. 2014 Oct;54(4):417–38 [cited 2023 Jan 8]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/soru.12055.10.1111/soru.12055Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Groth TM, Curtis A. Mapping farmer identity: Why, how, and what does it tell us? 2017 Jul;48(3):365–83 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. 101080/0004918220161265881. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00049182.2016.1265881.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Xie X. New farmer identity: The emergence of a post-productivist agricultural regime in China. Sociol Ruralis. 2021 Jan;61(1):52–73 [cited 2023 Jan 8]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/soru.12322.10.1111/soru.12322Suche in Google Scholar

[16] O’Callaghan Z, Warburton J. No one to fill my shoes: Narrative practices of three ageing Australian male farmers. Ageing Soc. 2017 Mar;37(3):441–61 [cited 2023 Jan 8]. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ageing-and-society/article/abs/no-one-to-fill-my-shoes-narrative-practices-of-three-ageing-australian-male-farmers/9FC023182998B2E5668ABCA84B5555B0.10.1017/S0144686X1500118XSuche in Google Scholar

[17] Rahman F. Potret transformasi masyarakat pegunungan jawa studi kasus: Sipetung Kabupaten Pekalongan Jawa Tengah. J Antropol Isu-Isu Sos Budaya. 2015;17(2):97–105 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. http://jurnalantropologi.fisip.unand.ac.id/index.php/jantro/article/view/43.10.25077/jantro.v17i2.43Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Radjab M. Analisis model tindakan rasional pada proses transformasi komunitas petani rumput laut di kelurahan Pabiringa kabupaten Jeneponto. Socius J Sosiol. 2014;16–28 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. https://journal.unhas.ac.id/index.php/socius/article/view/559.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Shortall S. Farming, identity and well-being: Managing changing gender roles within Western European farm families. Anthropol Noteb. 2014;20(3):67–81 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. http://notebooks.drustvo-antropologov.si/Notebooks/article/view/184.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Stenholm P, Hytti U. In search of legitimacy under institutional pressures: A case study of producer and entrepreneur farmer identities. J Rural Stud. 2014 Jul;35:133–42.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.05.001Suche in Google Scholar

[21] McGuire J, Morton LW, Cast AD. Reconstructing the good farmer identity: Shifts in farmer identities and farm management practices to improve water quality. Agric Hum Values. 2013 Mar;30(1):57–69 [cited 2023 Jan 8] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10460-012-9381-y.10.1007/s10460-012-9381-ySuche in Google Scholar

[22] Gray BJ, Gibson JW. Actor–networks, farmer decisions, and identity. Cult Agric Food Environ. 2013 Dec 1;35(2):82–101 [cited 2023 Apr 1]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cuag.12013.10.1111/cuag.12013Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Riley M. Still being the ‘Good Farmer’: (Non-)retirement and the preservation of farming identities in older age. Sociol Ruralis. 2016 Jan;56(1):96–115 [cited 2023 Jan 8]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/soru.12063.10.1111/soru.12063Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Hecht ML. 2002—a research odyssey: Toward the development of a communication theory of identity. 2009 Mar;60(1):76–82 [cited 2023 Jan 8]. 101080/03637759309376297. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03637759309376297.Suche in Google Scholar