Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

-

Yusmani Prayogo

and Khojin Supriadi

Abstract

Sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius (Fab.) is the main obstacle for sweet potato production in various countries. Root damage caused by C. formicarius larvae reduced root yield up to 100%. The aim of this study is to test the measures using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana for controlling C. formicarius in endemic land of entisol type. The control measure tested was the use of straw mulch and plastic mulch as well as the application of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. The research was conducted at the experimental station at Indonesian Legumes and Tuber Crops Research Institute, Malang from July to December 2018. The results showed that the measure for controlling C. formicarius using straw or plastic mulch combined with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana produces root yields between 17 and 26 t/ha. Using plastic mulch as a cover for mounds with the application of the fungus B. bassiana is more effective and efficient in controlling C. formicarius than the insecticide deltamethrin. Plastic mulch can physically inhibit the process of laying eggs and the formation of C. formicarius larvae, while B. bassiana is toxic to eggs, larvae, and adults of C. formicarius. The efficacy of control measure using plastic mulch and the application of B. bassiana can reduce yield losses by up to 96.76%. Technological innovation using plastic mulch to cover the mound with the application of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana can be recommended to control C. formicarius on land endemic to the entisol type.

1 Introduction

Cylas formicarius is one of the major pests in sweet potato in various parts of sub-tropical and tropical areas including Indonesia. The larvae are the highly destructive phase that takes approximately 7 days after the eggs are laid (but the hatching period depends on temperature, moisture, and relative humidity) [1,2,3,4]. The phase of the C. formicarius insect that can cause root damage is the larval stage, formed from the egg phase that hatches after approximately 6 days after being laid. The larval phase of C. formicarius consists of three instars that last approximately 35 days in the root before the pupa stage is formed. The adult stage formed from the pupa immediately penetrates the root skin to the outside of the soil surface to find food sources and produce eggs. Measure for controlling C. formicarius pests has not yet been found because the destructive stages of C. formicarius are in the roots within the soil, making it difficult to obtain appropriate, effective, and efficient measure [5,6].

Synthetic insecticides are effective to the adults because the adults live above the soil surface. The application of synthetic insecticides is effective when it is coupled with the choice of type of active ingredient, concentration, and time and method of application is right on the target [7,8,9]. Meanwhile, the larval phase inside the roots is still able to survive and bore the roots in the soil until the food source runs out. Several researchers previously stated that soil conditions’ structure greatly influences root damage due to C. formicarius attacks, especially in endemic land. This condition is caused by soil structures that easily crack/break in the dry season, such as entisol, making it easier for the adult to penetrate the soil surface while laying their eggs. Apart from that, the higher ridge also affects the safety of the roots from borer attacks because the roots are not exposed openly as they are protected in the ground. This condition is caused by the movement of the C. formicarius insect, which is very active if there is a disturbance in its surroundings. Besides, the insect also has the ability to pretend to be dead or immobile in order to avoid threats that endanger its existence [10,11].

Control measure of C. formicarius on entisol land with alluvial structures is more difficult; this condition is due to the fact that the land cracks easily during the dry season so that gaps are formed, which can make it easier for the adult to reach the base of the stem to lay their eggs. Entisol soil conditions are generally poor in organic matter so that their water holding power and capacity is very low. Control technique that can be applied to overcome these land conditions is to add organic material and apply mulch to cover the plant mounds so that insects are prevented from reaching the base of the sweet potato stems [12]. Another report states that the use of mulch made from organic materials derived from straw, shallots, tobacco, and chilies can also protect roots from damage by C. formicarius attacks in the soil. This condition is caused as the organic materials used contain metabolite compounds and vegetable pesticides, which are able to repel adult insects from laying eggs at the base of the stem [13,14]. Apart from increasing plant fertility, mulch covering mounds can also inhibit weed growth and egg laying [15,16,17,18]. Black or silver plastic mulch is more effective as a soil cover to protect and defend roots from C. formicarius attacks than other types of mulch [19,20].

Meanwhile, other researchers reported that the application of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana through the soil surface with the right frequency will be more effective in controlling sweet potato weevil pests compared to other methods [21,22,23,24]. Furthermore, previous literature [25,26,27, 28,29] recommend that biological control measure for sweet potato weevil can be carried out in combination with the application of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana. Application of B. bassiana through the soil surface at the right frequency was more effective in controlling pests in the soil compared to other methods [30]. Due to the efficacy of plastic mulch and the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana in suppressing sweet potato damage due to borer attacks, these two measure components can be applied or tested in entisol fields.

The aim of this research is to study the technological components of mulch and the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana for controlling the sweet potato weevil pest C. formicarius on endemic land of the entisol type.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Description of the study sites

The research was conducted at the experimental station at Indonesian Legumes and Tuber Crops Research Institute (ILETRI), Kendalpayak, Malang, East Java, Indonesia, from July to December 2018. The entisol land used in this study was declared as a location that has endemic criteria for sweet potato weevil pest attacks. The condition of the land at the time the activity took place was during the dry season, so that the soil cracked easily, which made it easier for the adult female to penetrate the surface of the soil to lay their eggs at the base of the sweet potato plant stems.

2.2 Treatments and experimental design

The research was arranged using a randomized block design consisting of six treatments and each treatment was repeated four times. The treatments tested were T1 = mound covered with straw mulch; T2 = mound covered with plastic mulch; T3 = mound covered with straw mulch and given B. bassiana at planting time, 30, 45, 60, and 75 days after planting (DAP); T4 = mound covered with plastic mulch and given B. bassiana at planting time 30, 45, 60, and 75 HST; T5 = application of chemical insecticide (deltamethrin) at planting time 30, 45, 60, and 75 HST; and T6 = not treated. The type of plastic mulch used in this research was black silver plastic which was applied before planting time. Each treatment used two bunds and each bund was 20 m long. The straw mulch used was the rice paddy plants collected after rice was harvested. Straw mulch was applied before sweet potato planting time. The research implementation consisted of several activities as follows:

2.2.1 Land preparation

The land was cultivated by plowing twice because the type of soil used was an alluvial structure entisol. The soil was loosened and given 3 t/ha of organic fertilizer and 2 t/ha of calcium mixed at the time of loosening the soil, 1/3 of 400 kg/ha of inorganic fertilizer at a dose of 90 kg N/ha (200 kg Urea/ha), 25 kg P2O5/ha (50 kg TSP/ha), and 50 kg K2O/ha (100 kg KCl/ha) is given at the time of planting, while the remaining 2/3 of the dose is given at 30 DAP. The soil was formed into bunds with a height of 40 cm, the distance between the mounds was 100 cm, and then each bund was covered with straw mulch for treatments T1 and T3. The bunds in treatments T2 and T4 were covered with plastic mulch, while those in treatments T5 and T6 were not covered using mulch. Straw mulch given at about 2 t/ha before planting covered the entire soil surface, especially the top of the mounds in treatments T1 and T3,. The plastic mulch used to cover the entire surface of the mounds in the T2 and T4 treatments was given a hole at the top of the mound, which was used to stick the sweet potato cuttings to be planted according to the spacing between the cuttings of about 25 cm.

2.2.2 Sweet potato cuttings

Planting sweet potato cuttings in this research activity was carried out in the dry season, July 16 2018, so that the land conditions were in accordance with the planting process carried out by the local farmers. The sweet potato variety used was Cilembu, obtained from potato development farmers in Tumpang District, Malang Regency, East Java. Sweet potato cuttings used as planting material are from the plant’s top, measuring 25 cm. The entire leaf stalk was cut off from the cuttings obtained from the land, leaving only two stalks at the top of the cuttings to avoid excessive evaporation. Furthermore, the sweet potato cuttings were soaked in shallot extract (Allium cepa) for 60 s so that the cuttings are free from scab infection (Sphaceloma batatas). The cuttings were drained for 24 h before planting. The cuttings are planted by sticking the base of the stem into a mound about 10 cm deep into the soil.

2.2.3 Biopesticide fungus B. bassiana

The B. bassiana fungus was obtained from the corpse of the C. formicarius insect from a sweet potato trader in Tumpang, Malang (East Java) in 2015. The fungus was then isolated and identified by comparing the morphological and physiological characters of the B. bassiana strain Tumpang 1 fungus isolate (TMP1) with that reported by Becerra et al. [26], Coates et al. [27], Humber [28,29]. The identified B. bassiana fungus isolate, namely, strain TMP1, was then propagated on media supplemented with 10% chitin to increase conidia production and fungal virulence as an efficacy test material.

The efficacy test of the B. bassiana fungus isolate, which has the ability to kill insects with a mortality rate of up to 99%, has been carried out on all stages of the C. formicarius insect . The multiplication of the fungus on the growth media was maintained until it was approximately 21 days after incubation. Then, it was put in a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask to which sufficient amount of sterile water was added. Furthermore, the grading agent (Tween 80 as much as 2 mL/L) was added and then shaken using a shaker for approximately 60 min so that all the formed conidia had fallen off. The conidial suspension was filtered to obtain the conidial supernatant of B. bassiana and then counted using a hemocytometer to obtain a conidia density of around 107/mL. The first application of the B. bassiana fungus in the T3 and T4 treatments was carried out at planting time, as a cutting treatment, by immersing the cuttings in a suspension of B. bassiana conidia for about 60 min. Conidia suspension was sprayed at the base of the stem at a volume of 20 mL per plant or the equivalent of 600 L/ha for a population of 30,000 plants. Follow-up applications are carried out starting at 30, 45, 60, and 75 DAP, by spraying at the base of the stem. The application was carried out in the afternoon with the hope that there would be no influence from UV light so that the efficacy of the fungus could play a maximum role in suppressing the attack of the sweet potato weevil.

2.2.4 Application of synthetic insecticides

This type of synthetic insecticide with the active ingredient deltamethrin with the commercial name of Decis is used at a dose of 5 mL/L which was only applied to T5 treatment (farmer cultivation method). The application of the synthetic insecticide deltamethrin was carried out at planting time by soaking the cuttings in a synthetic insecticide solution for 30 minutes, then the next application was carried out at the ages of 30, 45, 60, and 75 HST. Treatment of sweet potato cuttings using chemical insecticides follows the method usually used by local farmers for cultivating sweet potatoes.

2.2.5 Plant maintenance

Plant maintenance was done by weeding, turning stems, watering, and hilling. Weeding activities were carried out at 30 and 60 DAP, especially in treatments T1, T3, T5, and T6, while treatments T2 and T4 were not weeded because the bunds were covered using plastic mulch. Stem turning was carried out at 45 DAP with the aim of preventing the stem from sticking out in various places and concentrating the formation of roots only at the base of the main stem. Stem turning activities were carried out, especially in treatments T1, T3, T5, and T6, because plastic mulch was not used, whereas for treatments T2 and T4, it was not carried out. Cultivation was carried out at the age of 60 DAP in treatments T1, T3, T5, and T6 to ensure the formed roots were better protected from the C. formicarius egg-laying process.

2.3 Data collection and measurement

The variables observed were: (1) the total number of roots per plant, (2) the weight of the roots per plant, (3) the average diameter of the roots on each plant, (4) the percentage of root damage observed destructively by splitting the indicated roots, attacked by borers after harvest, (5) number of C. formicarius eggs per plant, (6) number of C. formicarius larvae per plant, and (7) yield of root weight per hectare. All data were obtained from the average of ten sample plants in each treatment. Meanwhile, the results for root weight per hectare were obtained from the average root weight of ten sample plants and then converted to hectares.

Root damage due to infestation of C. formicarius larvae was observed and measured based on damage scores which were divided into five levels using the method suggested by Talekar [31]. Score 0 = without any sign of rattling on the roots (0%); score 1 = root damage caused by C. formicarius larvae between 1 and 25%; score 2 = root damage caused by C. formicarius larvae between 26 and 50%; score 3 = root damage by larvae of C. fromicarius between 51 and 75%; and score 4 = root damage by larvae of C. formicarius >76% (roots not suitable for consumption). Furthermore, the results of the root damage score on the sample plants were used to calculate the intensity of root damage caused by C. formicarius using a method that was developed and modified by Rees et al. [32,33].

where ID is the intensity of root damage (%), n is the number of roots that are drilled on the v scale, v is the root damage scale value, N is the total number of roots observed, and Z is the highest value of root damage scale.

2.4 Data analysis

All data obtained with a normal distribution were then analyzed using the MINITAB 14 program; If there are differences between treatments, then the multiple range test (Duncan’s Multiple Range Test) is continued at α = 0.05 level.

3 Results

3.1 Influence of control measure on the number of eggs per plant

Adults of sweet potato weevil pests usually lay the eggs at the base of the stem before the formation of roots or at the time of root formation. The number of eggs was observed destructively by slowly cleaning the base of the stem from the remnants of soil attached to the part between the base of the stem and the root. The results showed that the highest average number of eggs occurred in the control or without treatment (T6), which reached 39 eggs/plant (Figure 1). The number of eggs in the straw mulch treatment (T1) appeared much lower than that in the without treatment (T6). However, the number of eggs in the T1 treatment was not significantly different from the chemical insecticide treatment (T5). In the treatment of covering the mounds using straw combined with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana and applied six times (T3), the number of C. formicarius eggs found was slightly lower when compared to the chemical insecticide treatment (T5), which was 20 eggs/plant although both the treatments did not differ significantly. The application of straw mulch as a cover for the mounds in the T1 treatment physically prevented the adult from laying eggs at the base of the stem so that the number of eggs found did not differ significantly from the efficacy of chemical insecticides (T5).

The average number of C. formicarius eggs found in each Cilembu sweet potato plant with various control technologies.

The results of the research showed that the lowest average number of C. formicarius eggs occurred in T4 and T2, namely, the application of plastic mulch as a cover for the embankment combined with the application of B. bassiana fungus. By using plastic mulch in the treatment, T2 only found around 9.50 eggs/plant. Meanwhile, in treatment T4, if plastic mulch was combined with B. bassiana fungus, the number of eggs found was only 5.25 eggs/plant.

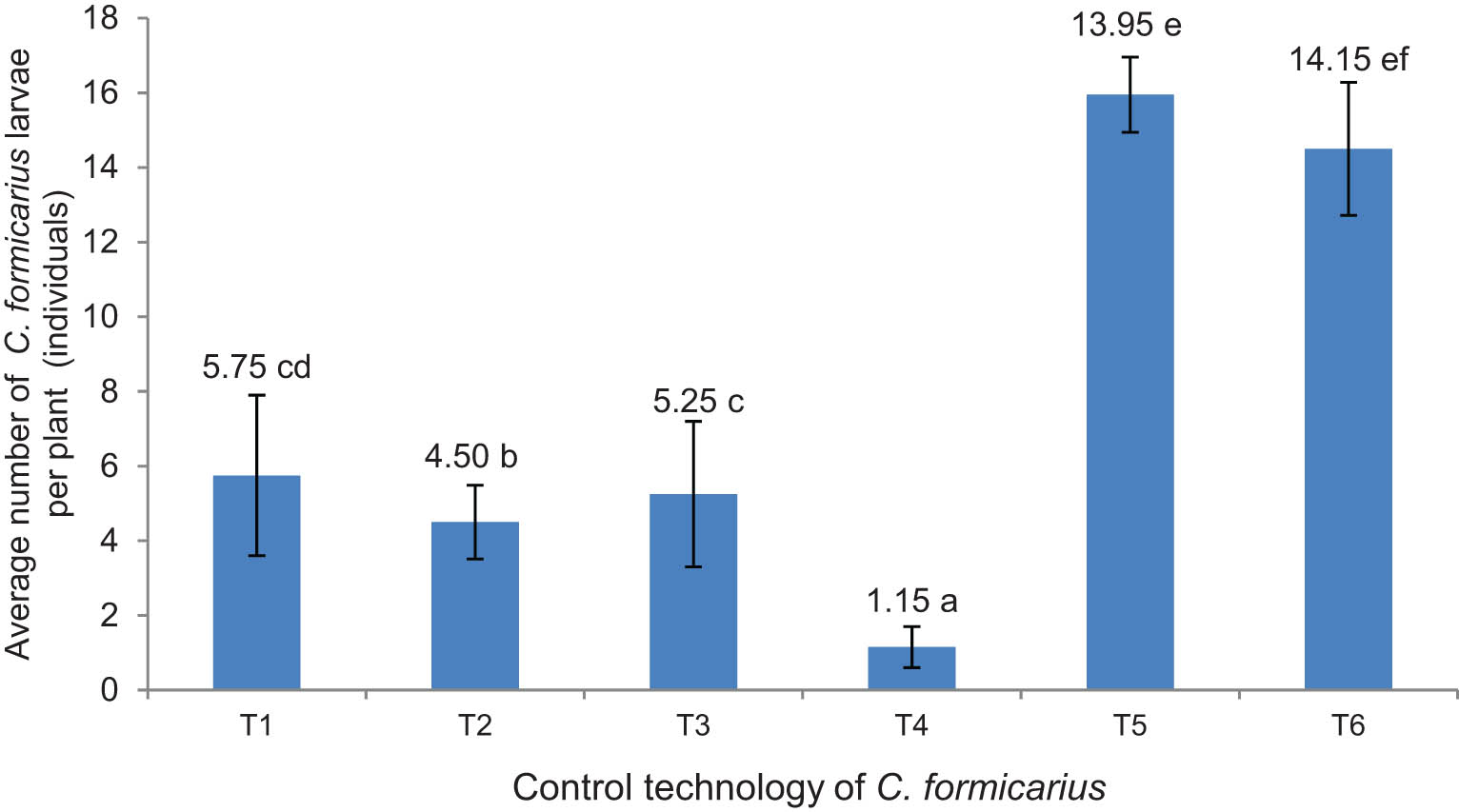

3.2 Effect of control measure on the number of C. formicarius larvae

The research results showed that the highest average number of larvae that bore roots on each plant was found in the chemical insecticide application treatment (T5), namely, up to 15 individuals/plant. The average number of larvae in T5 was greater when compared to that in without treatment (T6), namely, around 14 individuals/plant, although the two types of treatment were not significantly different (Figure 2). This condition is thought to be done incorrectly by applying the chemical insecticide compound to the target insect because the application is aimed at insects above the plant’s surface, so it is only possible to kill the adult if it is on the target. Meanwhile, insect activity is very active if disturbances are considered to threaten the existence of insects, such as spraying activities in the area. The more eggs laid at the base of the stem, the more chances the larvae will survive. This condition occurs because there are no chemical insecticide compounds that have the ability to kill the egg stage. Judging from the average number of eggs laid in the chemical insecticide treatment, it reached 21 per plant (Figure 1). Thus, the chance of survival for C. formicarius, which develops from the egg stage to larvae when treated with chemical insecticides (T5), reaches 71%.

Average number of C. formicarius larvae in roots using various control technologies.

The egg stage is the initial phase of insect development, after hatching, the insect will develop to form the larval stage. Meanwhile, all larval stages from instar 1 to 3 are able to burrow into the roots in the soil, causing damage to the formed roots. Therefore, the more eggs the adult lays at the base of the sweet potato stem, the more larvae will be formed and ultimately the level of damage caused will also be more severe.

3.3 Effect of control measure of C. formicarius on sweet potato roots

The research results showed that the number of roots obtained was around 3.3–4.8 roots/plant. The highest number of roots was obtained from the treatment of plastic mulch combined with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana which was applied five times (T4), namely, 4.8 roots/plant (Table 1). However, treatment T4 was not significantly different from the number of roots in treatment T3, namely, 4.60 roots/plant. The lowest number of roots occurred in the straw mulch treatment (T1), namely, only 3.30 roots/plant. However, T1 was not significantly different from the plastic mulch treatment (T2) and without treatment (T6), with 3.4 and 3.6 roots/plant, respectively. Meanwhile, after applying chemical insecticides using the active ingredient deltamethrin, 3.8 roots/plant were obtained. The number of roots obtained in the chemical insecticide treatment was indeed higher when compared to the T1, T2, and T6 treatments, but the efficacy of T5 was also determined by other supporting characters.

Average number, root weight, and root diameter of each plant on various control techniques of C. formicarius

| Treatment | Average number, weight, and diameter of roots | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number or roots | Root diameter (cm) | Root weight (g/plant) | |

| T1 | 3.30def | 3.9abc | 571.67bc |

| T2 | 3.40de | 4.5a | 666.34bc |

| T3 | 4.60ab | 4.4ab | 788.25b |

| T4 | 4.80a | 4.5a | 829.15a |

| T5 | 3.80c | 4.4ab | 598.76bc |

| T6 | 3.60cd | 3.9abc | 453.10d |

| DMRT 5% | 0.55 | 0.9 | 104.40 |

| CV (%) | 13.18 | 16.63 | 16.61 |

Column numbers followed by the same letter are not significantly different in the DMRT test at the 5% level.

The mean diameter of the roots ranged from 3.9 to 4.5 cm and the highest diameter was obtained from plastic mulch treatment alone or in combination with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana. Meanwhile, the lowest average root diameter was obtained from the straw mulch treatment and untreated control, namely, around 3.9 cm. The mean value of root diameter obtained from straw mulch combined with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana (T4) reached 4.5 cm/root (Table 1). However, the diameter of the roots in the T4 treatment was not significantly different from the single plastic mulch treatment (T2). The average root diameter obtained in treatment T4 was higher when compared with treatments T1 and T5. However, the average root diameter obtained was not significantly different from the five types of control measure tested. This condition was due to the fact that the average root diameter obtained from the five types of control measure was almost uniform and there were no significant differences.

The weight of the roots for each plant is obtained from all the roots formed and weighed at harvest time. The results showed that the weight of the roots obtained ranged from 453 to 829 g/plant (Table 1). The highest root weight was obtained from plastic mulch treatment combined with the fungus B. bassiana (T4), which reached 829.15 g/plant. The root weight in the treatment of straw mulch combined with the fungus B. bassiana was also relatively high, reaching 788.25 g/plant. However, root weight in T3 treatment was not significantly different from root weight in plastic mulch (666.34 g/plant), straw mulch (571.67 g/plant), and chemical insecticide applications (598.76 g/plant). Meanwhile, the lowest root weight was obtained in T6 (without treatment), namely, only 453.10 g/plant.

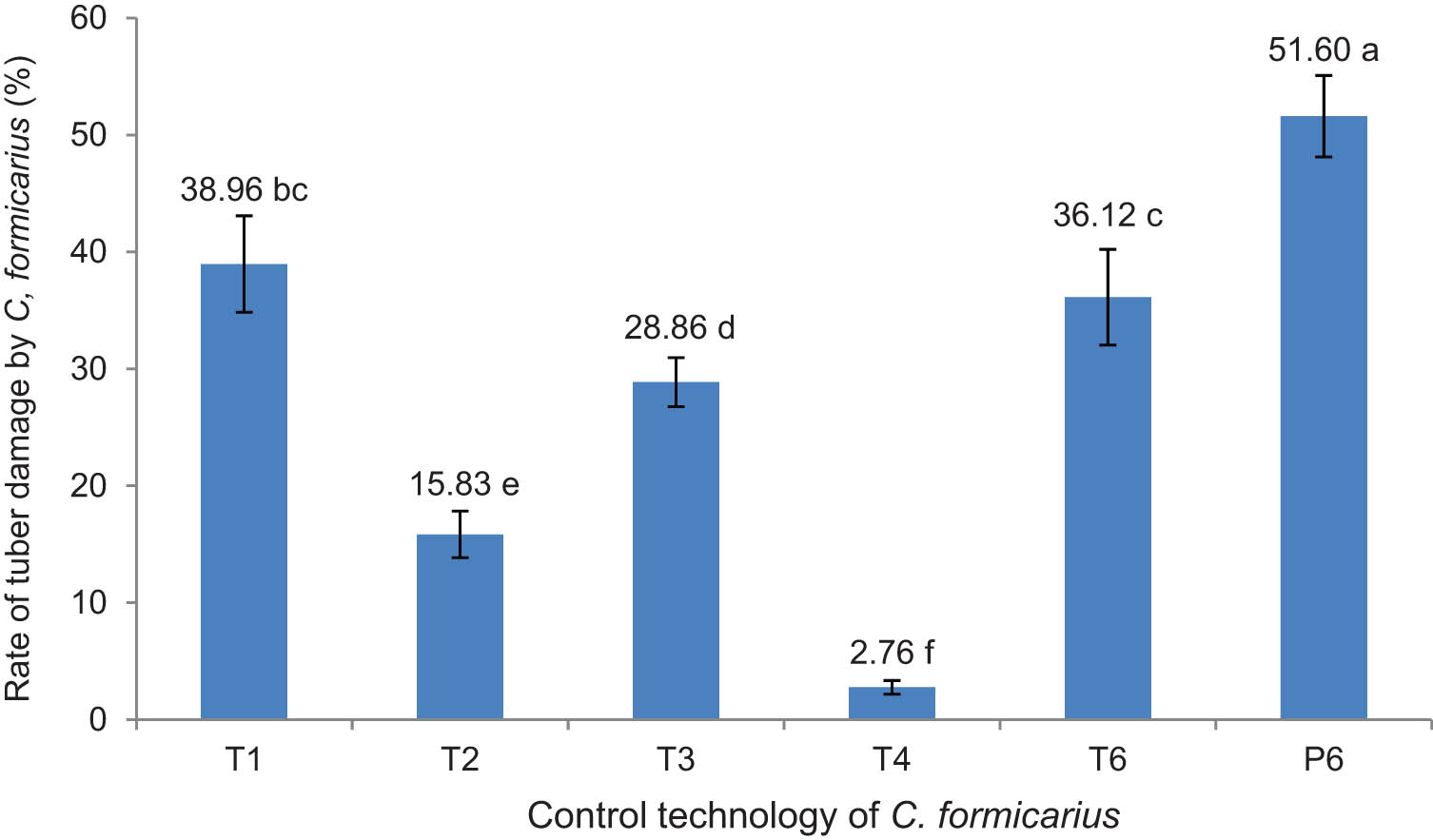

3.4 Effect of control measure on the level of root damage causedby C. formicarius

Root damage was calculated based on the number of roots ingested by C. formicarius larvae at various levels of damage using a modified score [34,35,36]. The study’s results showed that damage to roots ingested by C. formicarius larvae ranged from 2 to 51% (Figure 3). The highest level of damage, reaching 51.60%, occurred in the root without treatment (Figure 4). Root damage in the straw mulch treatment (T1) was quite high, namely, 38.96%, not significantly different from control measure using chemical insecticides, namely, 36.12%.

The average level of root damage by C. formicarius larvae under various control technologies.

Yield performance of Cilembu variety roots under various C. formicarius pest control techniques.

The straw mulch treatment, combined with the B. bassiana fungus, caused the control efficacy to increase, as evidenced by the level of root damage decreasing by 10%, namely, from 38.96 to 28.86%. Likewise, when the plastic mulch treatment was combined with the fungus B. bassiana, the control efficacy increased 13% from the infested roots by around 15% to just 2%.

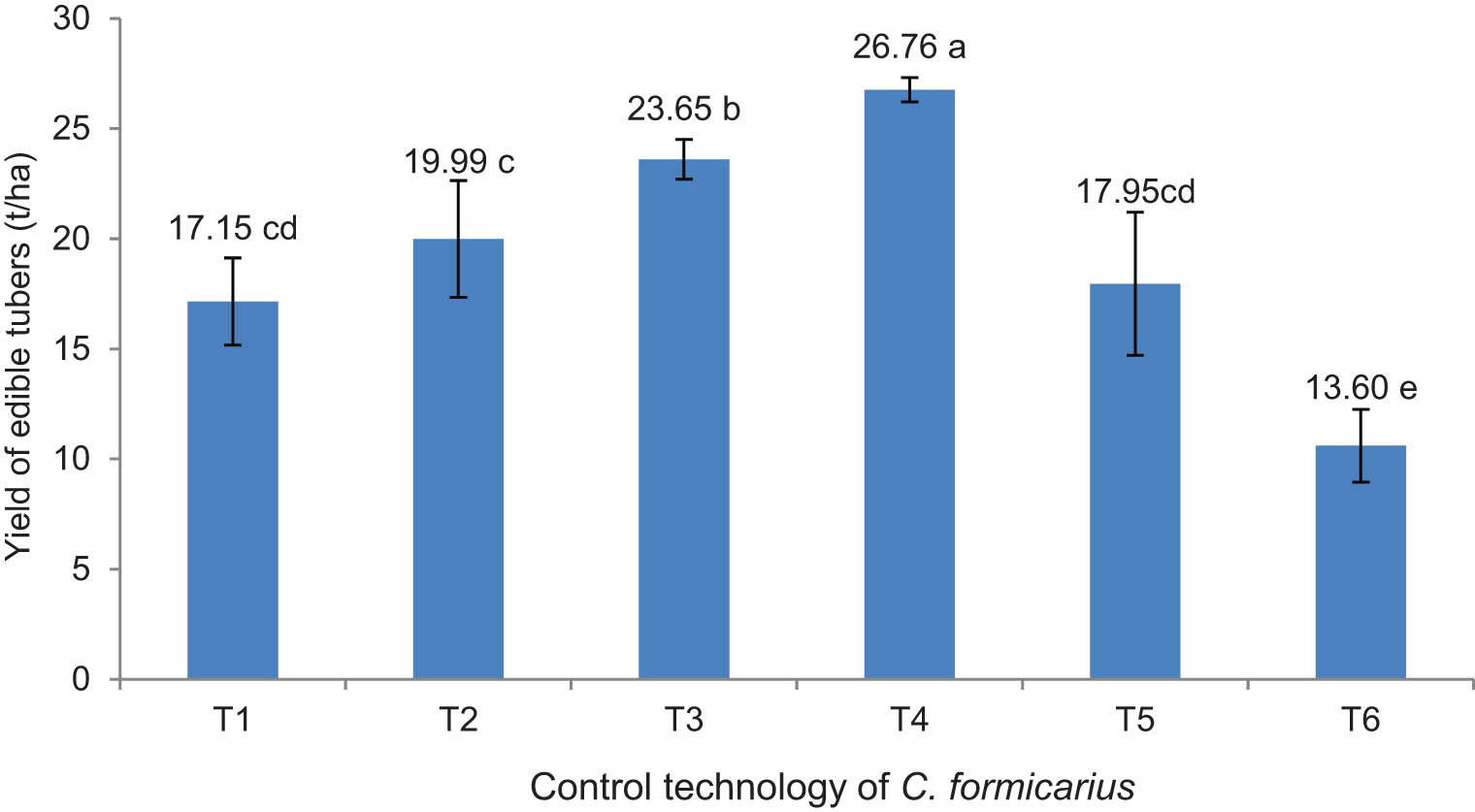

3.5 Root weight

The root weight yields obtained ranged from 13 to 26 t/ha with the highest yield achieved by the T4 treatment (26.76 t/ha) and significantly different from the other treatments. The T3 treatment yielded a relatively high root weight of around 23.65 t/ha and was higher than the straw mulch (T1), plastic mulch (T2), and chemical insecticide (T5) treatments with 17.15, 19. 99, and 17.95 t/ha, respectively (Figure 5).

The effect of various C. formicarius sweet potato weevil control technologies on the weight yield of edible roots.

4 Discussion

4.1 The influence of control measure on the number of eggs per plant

The number of eggs in the straw mulch treatment (T1) appeared much lower than in the uncontrolled treatment (T6). However, the number of eggs in the T1 treatment was not significantly different from the chemical insecticide treatment (T5). In the treatment of covering the mounds using straw combined with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana and applied six times (T3), the number of C. formicarius eggs found was slightly lower when compared to the chemical insecticide treatment (T5), which was 20 eggs/plant although both treatments did not differ significantly. According to [33], the use of various types of mulch from plant organs that contain metabolites has a positive effect on protecting roots from the attack by C. formicarius, especially on land that has a character that cracks easily during the dry season, by dispelling C. formicarius adult from laying eggs.

The application of straw mulch as a cover for the mounds in the T1 treatment physically prevented the adult from laying eggs at the base of the stem so that the number of eggs found did not differ significantly from the efficacy of chemical insecticides (T5). Suppose the straw mulch is combined with the application of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana six times, then the efficacy of the treatment (T3) becomes better than the efficacy of chemical insecticides because the number of eggs found is less. This condition is caused by the volatility of metabolite compounds produced by the fungus B. bassiana, which can affect insect behavior, one of which is the process of laying eggs [37,38].

Based on the number of eggs found on each plant in this study, it is clear that the plastic mulch treatment was more effective in suppressing C. formicarius from laying eggs when compared to the straw mulch or chemical insecticide treatment. This condition is caused by plastic mulch physically making it difficult for adult activity to reach the surface of the base of the plant stem. In addition, the volatile compounds from the toxins produced by the fungus B. bassiana can affect the egg-laying process because the insect is not interested in coming to the plant [39,40,41]. This fact is supported by research results [42,43], which indicate that the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana is able to inhibit the egg laying process of C. formicarius. Therefore, the number of eggs found in the application treatment using the B. bassiana fungus was very limited compared to the treatment not using the fungus.

4.2 Effect of control measure on the number of C. formicarius larvae

The number of larvae found in the straw mulch treatment combined with the B. bassiana fungus was relatively low when compared to the chemical insecticide treatments. Meanwhile, the plastic mulch treatment combined with the B. bassiana fungus was far more effective in suppressing the number of larvae found. Plastic mulch treatment can physically hinder the egg-laying process because the ovipositor has difficulty reaching the surface of the base of the stem. In addition, waves of UV light from plastic mulch can confuse adult, so they are not interested in laying their eggs on plants [44,45,46]. Plastic mulch can function as a physical factor that can inhibit the process of insect pest laying eggs in the soil so that the number of larvae that will develop is also limited [47].

The efficacy of the combination of plastic mulch with the fungus B. bassiana is because the conidia suspension of the fungus which is applied to the surface of the base of the plant stem can work more optimally. This condition is caused by increasing the soil moisture, especially at the base of the stem, which is covered with mulch so that eggs laid by adult females can become infected with fungi because fungi produce various types of toxins, which can cause eggs not to hatch to form larval stages. Toxins produced by B. bassiana, such as beauvericin, tenellin, beauverolides, and oosporein are ovicidal, so they are very toxic in thwarting the hatching of Tetranychus evansi eggs and various other types of pests [48,49,50]. The excess ovicidal properties of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana were also reported to be able to kill the order Diptera, Culicidae, and eggs of Tetranychus urticae [51,52,53]. The efficacy of the ovicidal properties of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana in preventing the hatching of the egg phase of C. formicarius has also been reported by Reddy et al. [54]. This phenomenon can prove that the efficacy of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana has an important role in determining the success of controlling sweet potato weevil pests. Thus, this entomopathogenic fungus can be recommended as a technological component to control the sweet potato weevil C. formicarius in an integrated pest control program because of the toxicity of the toxin it produces [55,56].

4.3 Effect of control measure on the level of root damage caused by C. formicarius

The straw mulch treatment, combined with the B. bassiana fungus, caused the control efficacy to increase, as evidenced by the level of root damage decreasing by 10%, namely, from 38.96 to 28.86%. Likewise, when the plastic mulch treatment was combined with the fungus B. bassiana, the control efficacy increased 13% from the infested roots by around 15% to just 2%. Roots that have been infested by C. formicarius larvae, even with a low level of damage, are declared unfit for consumption because the roots contain furan terpenes and coumarins, which can be toxic to consumers [57]. The results of the research showed that the application of plastic mulch which was used to cover the mounds and coupled with the application of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana could increase or protect root damage from borer attacks. The effectiveness of plastic mulch in maintaining the productivity of sweet potatoes obtained has also been reported in Papua New Guinea [58]. This condition is due to the fact that land humidity can be controlled, especially during the dry season, as well as being able to suppress the growth of existing weeds. Meanwhile, the efficacy of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana is able to protect roots from larval attacks, which are very limited in number [16].

4.4 Root weight

Controlling sweet potato weevil using chemical insecticides is considered less effective because it is only comparable to T1 and T2 as reported by Ownley et al. [59]. The disadvantage of controlling sweet potato weevil pests using chemicals besides being less effective is that the root products are exposed to chemical insecticide residues. Apart from that, applying chemical insecticides can kill natural enemies and cause poisoning or environmental pollution [60–62]. The results of the study by Prayogo and Bayu [63] indicated that the application of the fungus B. bassiana was more effective and more prospective in controlling C. formicarius in sweet potato weevil endemic fields in South Kalimantan when compared to the efficacy of the insecticide deltamethrin.

5 Conclusion

Straw and plastic mulch treatments can inhibit the egg-laying process and the formation of C. formicarius larvae at the base of the stem and its efficacy is comparable to the insecticide deltamethrin. The treatment of plastic mulch and the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana applied five times resulted in an yield of root edible for consumption reaching 26.76 t/ha, while the deltamethrin insecticide treatment was only 13.60 t/ha. The efficacy of measure to control the sweet potato weevil pest C. formicarius using plastic mulch with the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana has reached 96.76%, the root products obtained are also more organic, so the selling price is higher than conventional products. Therefore, plastic mulch measure with the application of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana five times starting at planting and then 30, 45, 60, and 75 DAP can be recommended as a technological innovation for controlling C. formicarius in endemic entisol type land.

Acknowledgments

The authors are highly grateful for the staff members of the ILETRI for their valuable support and the Indonesian Agency for Agricultural Research and Development for funding the field experiment work.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by the Indonesian Legumes and Tuber Crops Research Institute (ILETRI), the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia (Grant number 1807.202.006/APBN/2018).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Antiaobong EF, Bassae EE. Constraint and prospects of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) production in the humid environment of Southern Nigeria. Proceeding of the 2nd African Regional Conference on Sustainable Development, held at the governor’s office annex. Uyo, Nigeria; 2008. p. 68–72.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Okada Y, Kobayashi A, Tabuchi H, Kuranouchi T. Review of major sweetpotato pests in Japan, with information on resistance breeding programs. Breed Sci. 2017;67(1):73–82.10.1270/jsbbs.16145Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Kumari DA, Suresh V, Nayak HM, Anitha G, Hirur ME. Management of sweet potato weevils Cylas formicarius (Fab.). J Root Crops. 2018;44(2):61–7.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Prayogo Y, dan Bayu MSYI. Efficacy of biopesticide Be-Bas against sweet potato weevils (Cylas formicarius Fabricius) in Tidal Land. J Perlind Tanam Indones. 2019;23(1):6–15.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Capinera JL. Sweet potato weevil, Cylas formicarius (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae); 2012. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in154capinera/in154 [accessed March 24, 2021].Search in Google Scholar

[6] Devi M, Kumar KI, Niranjana RF. Biology of sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius on sweet potato. J Entomol Res Soc. 2014;38:53–7.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Mason LJ, Seal DR, Jansson RK. Respone of sweet potato weevil (Coleoptera:Apionidae) to selected insecticides. Florida Entomol. 1991;74(2):350–5.10.2307/3495317Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ondeto BM, Nyundo C, Kamau L, Muriu SM, Mwangangi JM, Njagi K, et al. Current status of insecticide resistance among malaria vectors in Kenya. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10(429):1–13. 10.1186/s13071-017-2361-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Himuro C, Kohama T, Matsuyama T, Sadoyama Y, Kawamura F, Honma A, et al. First case of successful eradication of the sweet potato weevil, Cylas formicarius (Fabricius), using the sterile insect technique. Plos One. 2022;12:1–17. 10.1371/journal.pon.0267728.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kuriwada T, Kumano N, Shiromoto K, Haraguchi D. Age-dependent in death feigining behavior in the sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius. Physiol Entomol. 2011;36(2):149–54.10.1111/j.1365-3032.2010.00777.xSearch in Google Scholar

[11] Myers RY, Sylva CD, Mello CL, Snook KA. Reduced emergence of Cylas formicarius elegantulus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) from sweet potato roots Heterorhabditiis indica. J Econ Entomol. 2020;113(3):1129–33.10.1093/jee/toaa054Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Tesfaye B. Development of management practice for sweet potato weevil, Cylas puncticollis (Boh) in South Ethiopia. (thesis) Alemaya University. (Au); 2003. p. 41.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Reddy GVP, Zhao Z, Richard AH. Laboratory and field efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi for the management of the sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius (Coleoptera: Brentidae). J Invertebr Pathol. 2014;122:10–5.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Mansaray A, Sundufu AJ, Nosoeray MT, Fomba SN. Sweet potato weevil (Cylas puncticollis) Behman infestation: Cultivar differences and effects on mulching. Open Entomol J. 2015;9:7–11.10.2174/1874407901509010007Search in Google Scholar

[15] Korada RR, Naskar SK, Palaniswami MS, Ray RC. Management of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius F.): An overview. J Root Crops. 2010;36(1):14–26.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Rehman M, Liu J, Johnson AC, Dada TE, Gurr GM. Organic mulches reduce crop attack by sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius). Sci Rep. 2019;9:14860. 10.1038/s41598-019-50521-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Döring TF, Brandt M, Heh J, Finckh MR, Saucke H. Effects of straw mulch on soil nitrate dynamics, weeds, yield and soil erosion in organically grown potatoes. Field Crops Res. 2005;94:238–49.10.1016/j.fcr.2005.01.006Search in Google Scholar

[18] Gunasekaran P, Shakila A. Effect of mulching on weed control and tuber yield of medicinal coleus (Coleus forskholli Briq.). Asian J Hortic. 2014;9(1):124–7.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Goitom T, Tsegay A, Asegu BA. Effect of organic mulching on soil moisture, yield and yield contributing components of sesame (Sesame indicum L.). Inter J Agron. 2017;6:1–6.10.1155/2017/4767509Search in Google Scholar

[20] Ossom EM, Pace PF, Rhykend RI, Rhykerd CL. Effect of mulch tuber weed infestation, soil temperature, antigen concentration and tuber yield in Ipomoea batatas in Papua New Guinea. Trop Agric. 2001;78:144–51.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Bucki P, Siwek P. Organic and non-organic mulces impact on environment, a review. J Environ Hortricult. 2019;25:239–49.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kyereko WT, Hongbo Z, Amoanima-Dede H, Meiwei D, Yeboah A. The major sweet potato weevils; management and control: a review. Entomol Ornithol Herpetol Curr Res. 2019;8(2):1–9.10.35248/2171-0983.8.218Search in Google Scholar

[23] Su CY. Field application of Beauveria bassiana for control of sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius. Chin J Entomol. 1991a;11:162–8.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Yasuda K. Auto-infection system for the sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) with entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana using a modified sex pheromone trap in the field. Appl Entomol Zool. 1999;34:501–5.10.1303/aez.34.501Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ondiaka S, Maniania NK, Nyamasyo GH, Nderitu JH. Virulence of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae to sweet potato weevil Cylas puncticollis and effects on fecundity and egg viability. Ann Appl Biol. 2008;153:41–8.10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00236.xSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Becerra VV, Paredes C, Rojo CM, France AL. RAPD e ITS detectan variación molecular en poblaciones chilenas de Beauveria bassiana. Agric Téc (Chile). 2007;67:115–25.10.4067/S0365-28072007000200001Search in Google Scholar

[27] Coates B, Hellmich R, Lewis L. Allelic variation of a Beauveria bassiana (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) minisatellite is independent of host range and geographic origin. Genome. 2002;45:125–32.10.1139/g01-132Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Humber R. Entomopathogenic fungal identification. USDA-ARS Plant Protection Research Unit US Plant, Soil & Nutrition Laboratory Tower Road Ithaca; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Humber R. Identification of entomopathogenic fungi. In: Lacey L, editor. Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology. 2nd edn. Academic Press; 2012.10.1016/B978-0-12-386899-2.00006-3Search in Google Scholar

[30] Ali A, Sermann H, Lerche S, Buttner C. Soil application of Beauveria bassiana to control Ceratitis capitata in semi field conditions. Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci. 2009;74:357–61.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Talekar NS. Characteristics of infestation of sweet potato by sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius (Coleoptera: Apionidae). Inter J Pest Manag. 2008;41(4):238–42.10.1080/09670879509371957Search in Google Scholar

[32] Rees D, Kapinga R, Munda K, Chilosa D. Effect of damage on market value and shelf life of sweet potato in urban markets of Tanzania. Trop Sci. 2021;41(3):142–50.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Stathlers T, Rees D, Kabi S, Mbilinyi D. Sweetpotato infestation by Cylas spp. in East Africa: I. Cultivar differences in field infestation and the role of plant factor. Inter J Pest Manag. 2003;49(2):131–40.10.1080/0967087021000043085Search in Google Scholar

[34] Muyinza H, Talwana HL, Mwanga ROM, Stevenson PC. Sweetpotato weevil (Cylas spp.) resistance in African sweetpotato germplasm. Inter J Pest Manag. 2012;58:73–81. 10.1080/09670874.2012.655701.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Stevenson PC, Muyinza H, Hall DR, Porter EA, Farman DI, Talwana H, et al. Chemical basis for resistance in sweetpotato Ipomoea batatas to the sweetpotato weevil Cylas puncticollis. Pure Appl Chem. 2009;81:141–51. 10.1351/PAC-CON-08-02-10.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Kagimbo F, Shimelis H, Sibiya J. Sweetpotato weevil damage, production constrains, and variety preferences in Western Tanzania: Farmers perception. J Crop Improv. 2018;32(1):107–23.10.1080/15427528.2017.1400485Search in Google Scholar

[37] Wang F, He Z. Effects of plastic mulch on potato growth. In: He Z, Larkin R, Honeycutt W, editors. Sustainable potato production: Global Case Studies. Berlin: Springer; 2012.10.1007/978-94-007-4104-1_21Search in Google Scholar

[38] Hlerema I, Laurie S, Eiasu B. Preliminary observations on use of Beauveria bassiana for the control of the sweet potato weevil (Cylas sp.) in South Africa. Open Agric. 2017;2:595–9.10.1515/opag-2017-0063Search in Google Scholar

[39] Leng PH, Reddy GVP. Bioactivity of selected eco-friendly pesticides against Cylas formicarius (Coleoptera: Brentidae). Florida Entomol. 2012;95(4):1040–9.10.1653/024.095.0433Search in Google Scholar

[40] Saputro TB, Prayogo Y, Rohman FL, Alami NH. The virulence improvement of Beauveria bassiana in infecting Cylas formicarius modulated by various chitin based compounds. Biol Biodiv. 2019;20(9):2486–93.10.13057/biodiv/d200909Search in Google Scholar

[41] Chen J. Evaluation of control tactics for management of sweetpotato weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Doctoral Dissertations. Lousiana State University; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Ramirez-Ordorica A, Contreras-Cornejo HA, Orduno-Cruz N, Luna-Cruz A, Winkler R, Macías-Rodríguez, L. Volatile release by Beauveria bassiana induce oviposition behavior in the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2022 10;98(10):fiac114. 10.1093/femsec/fiac114.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Shi WB, Feng MG, Liu SS. Sprays of emulsifiable Beauveria bassiana formulation are ovicidal towards Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) at various regimes of temperature and humidity. Exp Appl Acarol. 2008;46(104):247–57.10.1007/978-1-4020-9695-2_20Search in Google Scholar

[44] Amare G, Desta B. Coloured plastic mulches: impact on soil properties and crop productivity. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2021;8(4):1–9. 10.1186/s40538-020-00201-8.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Mulumba LN, Lal R. Mulching effect on selected soil physical properties. Soil Tilllage Res. 2008;98:106–11.10.1016/j.still.2007.10.011Search in Google Scholar

[46] Nithisha A, Bokado K, Charitha KS. Mulch: Their impact on the crop production. Pharma Innovation J. 2022;11(7):3597–603.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Nisha SM, Jebanesan A, Kumar CM. Ovicidal activity of entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae against Dengue Vector Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Insect Environ. 2013;19:195–6.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Lah EFC, Musa RNAR, Ming HT. Effect of germicidal UV-C light (254 nm) on eggs and adult of house dustmites, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farina (Astigmata: Pyroglyhidae). Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(9):679–83.10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60209-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Wekesa VW, Knapp M, Maniania NK, Boga H. Effects of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae on mortality, fecundity and egg fertility of Tetranychus evansi. J Appl Entomol. 2006;130(3):155–9.10.1111/j.1439-0418.2006.01043.xSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Al Khouri C, Guillot J, Nemer N. Lethal activity of beauvericin, a Beauveria bassiana mycotoxin, against the two-spotted spider mites, Tetranychus urticae Koch. J Appl Entomol. 2019;143(9):974–83.10.1111/jen.12684Search in Google Scholar

[51] Gao YP, Luo M, Wang XY, He XZ, Lu W, Zheng XL. Pathogenicity of Beauveria bassiana PfBb and immune responses of a non target host Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insects. 2022;13(10):914. mdpi.com/2075−4450/13/914 10.339/Insects13100914.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Krishna AR, Bhaskar H. Ovicidal and adulficidal effect of acaropathogenic fungi, neem oil and new acaricide molecules on Tetranychus urticae koch. Entomon. 2013;38:177–82.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Zhang L, Shi WB, Feng MG. Histopathological and molecular insights into the ovicidal activities of two entomopathogenic fungi against two-spotted spider mite. J Invertebr Pathol. 2014;117:73–8.10.1016/j.jip.2014.02.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Reddy GVP, Zhoo Z, Humber RA. Laboratory and field efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi for the management of the sweet potato weevil, Cylas formicarius (Coleoptera: Brentidae). J Invertebr Pathol. 2014;122:10–5.10.1016/j.jip.2014.07.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Valencia JWA, Bustamante ALG, Jimenez AV, Grosi-de-Sa MF. Cytotoxic activity of fungal metabolites from the pathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana: An intraspecific evaluation of Beauvericin production. Curr Microbiol. 2011;63:306–12.10.1007/s00284-011-9977-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Dara SK, Dara SR, Dara SS. Endophytic colonization and pest management potential of Beauveria bassiana in strawberries. J Berry Res. 2013;3:203–11.10.3233/JBR-130058Search in Google Scholar

[57] Uritani I, Saito T, Honda H, Kim WK. Induction of furano-terpenoids in sweet potato roots by the larval components of the sweet potato weevils. Agric Biol Chem. 1975;39(9):1857–62.10.1080/00021369.1975.10861857Search in Google Scholar

[58] Ossom EM, Pace PF, Rhykend RI, Rhykend CL. Effect of mulch tuber weed infestation, soil temperature, antigen concentration and tuber yield in Ipomoea batatas in Papus New Guinea. Trop Agric. 2001;78:144–51.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Ownley BH, Pereiera R, Klingeman WE, Quigley NB. Beauveria bassiana, a dual purpose biological control with actvity against insect pests and plant pathogens. In: Lartey RT, Caesar AJ, editors. Emerging Concepts in Plant Health. India: Research Signpost; 2004. p. 255–69.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Misra AK, Singh RS, Pandey SK. Relative efficacy of chemicals and botanical insecticide against sweet potato weevil, Cylas formicarius Fab. Entomol Ornithol Herpetol. 2001;8(2):1–9.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Bommarco R, Miranda F, Bylund H, Bjorkman C. Insecticides suppress natural enemies and increase pest damage in cabbage. J Econ Entomol. 2011;104(3):782–91.10.1603/EC10444Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Dad K, Zhao F, Hassan R, Javed K, Nawas H, Saleem UM, et al. Pesticides uses, impacts on environment and their possible remediation strategies – A review. Pak J Agric Res. 2022;35(2):274–582.10.17582/journal.pjar/2022/35.2.274.284Search in Google Scholar

[63] Prayogo Y, Bayu MSYI. Efficacy of Biopesticide Be-Bas against Sweet Potato Weevils (Cylas formicarius Fabricius) in Tidal Land. J Perlind Tanam Indones. 2019;23(1):6−15.10.22146/jpti.32752Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer