Abstract

All birds produce vocalizations as a form of tcommunication with other individuals. Different from songbirds, crowing is a singing vocalization produced by chickens that cannot be learned through imitation. Some genes are assumed to be responsible for this activity. The long-crowing chickens have a melodious and long sound, so they are categorized as singing chickens. They are part of the biodiversity in Indonesia, which has high economic and socio-cultural value. Reviews about long-crowing chickens, especially in Indonesia, are still very rare. This article aims to identify the uniqueness and the existence of long-crowing chickens, together with the conservation efforts needed to manage them. Information was collected from journal articles and other relevant documents. There are four local chickens in Indonesia classified as long-crowing chickens. They are developed in different areas of the community with different socio-cultural characteristics. The fundamental differences among the breeds that can be quantified are in crowing duration and the number of syllables. The government has acknowledged that long-crowing chickens are important genetic resources; however, the association and individual keepers or enthusiasts are vital actors in conservation efforts. The information about long-crowing chickens in Indonesia is incomplete. The research activities that need to be conducted include exploring the population number and distribution, as well as documentation of the local knowledge of chicken breeders and enthusiasts.

1 Introduction

Domestic animals, which contribute to agriculture and food production, are derived from about 40 domesticated livestock species. These animals are usually called domestic farm animals or animal genetic resources (AnGRs) [1]. Currently, about 8,800 breeds of 38 different species contribute to a variety of products and services [2]. Their contribution is important in providing food, and the resources play an important role in the livelihoods of millions of people [3] and are vital for future food assets [4]. The resources have an important socio-cultural function, reflect the historical identity, and have been integral parts of traditions in many societies [5]. As part of the world’s biodiversity, AnGRs contribute to regulating ecological functions, landscape management, and providing habitats [6]. The conservation of AnGR is a key step to resisting future unforeseen events such as climate change [7].

AnGRs can be classified into local and transboundary breeds. Local breeds occur only in one country and are characterized by low input and adaption to the harsh environment, while transboundary breeds are high-output commercial breeds for use on a large scale to produce single products [1]. Among AnGRs, chicken is one of the world’s most populated and widespread animals [1,5,8]. Most of them are characterized as transboundary breeds developed for specific products such as meat or eggs [9]. Selection efforts in poultry industries that focused on specific traits have generally shifted lower productivity chicken breeds which posed a threat to the survival of many local breeds [10]. It has been reported that local chicken breeds are highest at risk of extinction [1,3].

Chickens have been domesticated since ∼8,000 years ago [11]. Chickens have experienced intensive human-induced evolution resulting in breeds for several purposes including ritual ceremonies, traditional entertainment, and culinary purposes [12–14]. It was reported that chickens were first selected for fighting abilities and later for rituals [15]. Commercial chickens for meat and egg sources were only selected approximately 100 years ago [11]. The most likely wild ancestor of the domestic chicken is the genus Gallus [8], in particular the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) that is originally domesticated in some regions in Asia including Southeast Asia [16,17], South Asia, and Southwest China [18]. Rice farming practices may have facilitated the initiation of chicken domestication, and the distribution of chickens in the world started after the integration of chickens into human communities [19]. In Asia, the distribution of chickens was closely related to the distribution of the activity of cockfighting [13].

The fighting cocks are presumed to be the ancestors of the long-crowing chickens [20]. The rooster is evidence that people have developed the required characteristics of chickens for daily life, such as entertainment [12,13]. A long-crowing rooster has a longer crowing duration than a normal rooster. This type of chicken is commonly found in Asia, such as in Japan and Indonesia. In Indonesia, a country known as the world’s mega biodiversity, some long-crowing roosters have been discovered on the islands of Sumatera, Java, and Sulawesi [21]. The chickens contribute to the socio-economic of the keepers and become icons of the area they are developing. Scientific evidence regarding the development of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia requires comprehensive studies. In general, its development relates to the folklore in each region. The long-crowing cocks are widely regarded as the preferred animals of certain legendary figures. On the other hand, scholars presume that the long-crowing cocks are genetic variations of the junglefowl, such as red or green junglefowl that are commonly found in the islands of Indonesia. The community developed this junglefowl based on their preference characteristics that linked to their sociocultural values. The government acknowledged these chickens as an important genetic resource that needs to be conserved.

There are at least 31 chicken breeds in Indonesia [22]. The breeds consist of 11 breeds classified as egg producers, 12 breeds as ornamental chickens, 4 breeds as broilers, and 9 breeds that could not be categorized into specific categories [23]. The cluster of chickens in Indonesia is in the same cluster as the chickens in Thailand [17]. It is assumed that the chickens in Indonesia are a diversification of chickens in mainland Southeast Asia, such as Thailand [24]. However, it was claimed that Indonesia is one of the centers of chicken domestication in the world apart from China and India [21,23]. Red and Green junglefowl are presumed to be the ancestors of local chickens in Indonesia based on the diversity of D-loop mitochondrial DNA [21].

This article aims to provide information about the uniqueness of long-crowing chickens, the existence of the long-crowing chicken breeds in Indonesia, and the conservation activities required to manage the chickens sustainably. Appropriate research papers and other documents such as books were reviewed after being collected from Google Scholar. The keywords used to explore the information were crowing chickens and local chickens. Publications that were not written in English from reliable sources are included due to the limited information about long-crowing chickens in Indonesia.

2 Crowing production and crowing control genes

Birds produce sounds or vocalizations for many functions. The vocalization can be divided into calls and songs. In general, the call is one short sound, while the song is a long and complex pattern of sounds [25]. It is believed that male individuals of almost all bird species are capable of singing. The birds sing to show the territory of power (territory) to other male individuals and attract the attention of female individuals (courtship) [26]. The song of the chickens is known as crowing. Unlike songbirds such as canaries, chickens cannot learn their vocalizations through imitation. Thus, chickens are categorized as non-learners because they only produce innate vocalization [25,26]. Some chicken breeds have been developed for long-crowing chickens, such as Toutenkou, Koeyoshi, and Toumaru chickens in Japan [12,13] as well as Denizli fowl from Turkey [27].

2.1 Crowing of chickens

In vocal learner birds such as songbirds, parrots, and hummingbirds, there is a neural network called the song system specialized for vocal learning and production. The neural network is absent in non-learner birds such as chickens and pigeons; thus, the non-learners can only produce innate sounds [25]. Birds make sounds through expiration [28]. In birds, the sound is produced by the syrinx or voice box located at the junction between the trachea and the bronchi. In the syrinx is a pair of medial tympanic membranes, namely vibrating membranes that produce sound when air passes through during expiration [29]. Anatomical and physiological factors influenced the sound [30]. The scale of birds, age, and weight naturally affect sound production and characteristics [31].

In chickens, crowing is a testosterone-dependent activity [32], and hormone production increases when the bird is close to puberty [33]. Testosterone administration induces chicks to crow [34]. The rooster crowing symbolizes the break of dawn, and it is frequently observed in the morning. External stimuli such as light and crowing by other individuals, as well as the circadian clock, induce roosters’ crowing [35]. Crowing communicates a social hierarchy in the rooster group [36]. A dominant rooster is more frequent in crowing than subordinates [37] and crows first every morning [36]. The crowing sound of dominant individuals will restrain the subordinate males without direct contact [38].

2.2 Crowing control genes

All structures of the genomes in the chicken and songbird are similar. However, they have differences, for example in intrachromosomal rearrangements, and mechanisms of sex chromosome dosage compensation [39]. The unique crowing ability of birds is a qualitative trait that is generally influenced by a limited number of genes. Studies have characterized some genes that are involved in singing ability in birds and crowing in chickens, such as FOXP2, Zenk, dopamine receptor, and cholecystokinin B receptor (CCKBR).

FOXP2 is a gene that delivers instructions for producing protein forkhead box P2. This protein is essential for the critical learning of vocal communication in humans and birdsong [40–42] and is important for the connection process between neurons (synapses) to change and adapt to experience over time (synaptic plasticity) [43,44]. The FOXP2 gene maintains syllable sequencing in the adulthood of the songbird [45] and has a common function in vocal motor control [46–48]. The songbirds require FoxP2 to have normal auditory-guided vocal motor learning [41]. The mRNA and protein expression of FoxP2 was sexually dimorphic and possibly controlled the rooster crow [42]. A study identified polymorphisms in FOXP2 in crowing and non-crowing chickens and revealed identical exon seven sequences in both types of chickens [49].

ZENK is an immediate early gene that encodes a transcription factor protein [50–52]. The expression mRNA of the ZENK gene increases rapidly when songbirds receive the song of another individual or when they sing [50]. The expression level of ZENK was positively correlated with song duration in sparrows [53]. The level of ZENK mRNA in chicks increases significantly after being exposed to the acoustic imprinting paradigm [51]. The exposure to maternal call increased the levels of ZENK in day-old chickens and day-old quails [54].

Dopamine is a significant neuromodulator transmitter in the brain that acts on neural activity, gene expression, and behavior [55]. It regulates movement, reward, cognition, and emotion [56]. The dopamine receptor is likely involved in song development and social context-dependent behaviors [55]. The accuracy of the song in Zebrafinch correlated negatively with the expression level of the dopamine receptor, while the sequential match correlated positively [57]. The dopamine receptor genes, such as D4 genes, were explored in Japanese chicken breeds including Shamo, Naganakidori, and Chabo. The study showed that Shamo, a fighting cock, had a higher index of nucleotide differentiation value for dopamine receptor D4 compared to other chickens [20].

The gene encoding cholecystokinin (CCK) is widely expressed in the mammalian brain and is associated with the functions of regulating food intake, satiety, and modulating behaviors such as anxiety, learning, and memory [58]. The results of the study characterizing the expression of CCK in songbirds suggest a possible regulatory involvement of this gene in important aspects of bird song biology, such as perceptual processing, auditory memory, and/or vocal motor control of chirp (song) production [59]. CCK is a neurotransmitter that is abundantly expressed in different parts of the brain, and the highest expression levels are revealed in the hypothalamus of chickens [60].

The CCKBR is a regulatory gene involved in inducing crow sounds in roosters. An increased CCKBR gene expression in chicks induced by testosterone can make them crow [34]. CCKBR intracerebral system was activated by social pressure [61]. Social stress causes anxiety by increasing the CCKBR hormone, which can induce crows in chickens [62]. Social stressors such as unfamiliar individual crows could induce roosters to crow [35,36].

Polymorphism occurs in any trait and in any coding or noncoding fragment of DNA [63]. Functional polymorphism influences mRNA processing and translation, resulting in phenotypic variability [64]. Polymorphism is a major factor in phenotypic evolution and variability in humans [65]. This genetic mechanism is common in the traits of all organisms, including in birds. Genetic variation, caused by a mutation in the DNA segment of candidate genes involved in the singing and crowing abilities of birds, can influence their gene expression to create a level of an encoded protein.

3 The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia

Some local chickens categorized as long-crowing chickens are Pelung chicken from Cianjur, West Java Province, Kokok Balenggek from Solok, West Sumatra Province, Bekisar from Madura, East Java Province, and Gaga or Ketawa chicken from Sidrap, South Sulawesi Province [22,66]. Pelung, Kokok Balenggek, and Gaga chickens are categorized as natural chicken breeds, while Bekisar is categorized as a hybrid chicken [66]. Figure 1 illustrates the origin of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia.

The origin of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia.

Numerous studies have sought to unravel the origins, distribution, and kinship of chickens, including investigations into the Indonesian long-crowing variety. One such study examined the mitochondrial DNA diversity in the D-loop region to determine the kinship relationships and possible distribution of these chickens [21]. The findings revealed that the majority of Indonesian long-crowing chickens belong to haplogroups B, D, and E, with haplogroup D being the most dominant. These results suggest that long-crowing chickens in Indonesia have diverse maternal lineages originating from various regions, such as China, India, and Southeast Asia. These discoveries shed light on the complex ancestry and evolutionary history of these remarkable birds. Chickens in Southeast Asia are mostly categorized into Haplogroup D. In particular, the chickens in the Islands of Southeast Asia (including Indonesia) were a diversification of the chickens in mainland Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar) developing a divergent sub-haplogroup D1b [24]. As domestic birds, chickens were initially integrated into human societies in peninsular Southeast Asia, and then they rapidly spread into Island Southeast Asia and other adjacent areas [19].

3.1 Bekisar chickens

Bekisar chicken is the result of a cross between a male green junglefowl (Gallus varius) or a male red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) with a female local chicken (Gallus domesticus) [67]. A study about kinship relations using the diversity of the mitochondrial DNA D-loop region revealed that Bekisar is the ancestor of all crowing chickens in Indonesia [21]. There are two methods that can be applied to cross male junglefowl and female local chickens to produce Bekisar, namely traditional and artificial insemination [68]. Enthusiasts usually raise male Bekisar, as the chickens are fertile. Female Bekisar chickens are used for consumption since the chickens are infertile. This is a challenge in the development of Bekisar because to increase the population of Bekisar, breeders must use a greater number of male junglefowl [69].

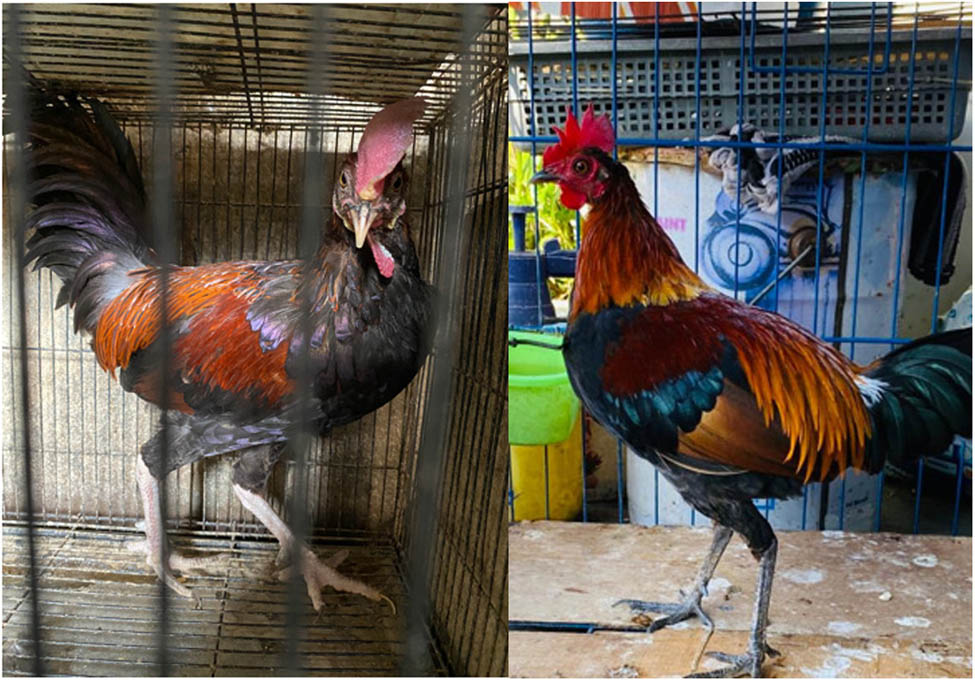

At first, Bekisar could only be found in Kangean, a small island to the east of Madura Island, including the Sumenep Regency area, East Java Province. Bekisar symbolizes the fauna of the East Java region, which was developed by the society to produce singing chickens with beautiful feathers [66,70]. A rooster has a shiny blackish-green plumage [66]. In general, a Bekisar has a long, rhythmic, and straight crow [71,72] which consists of two syllables [73]. The crowing of the chicken can be categorized as the front (first syllable) and back crowing (second syllable). The front sound is low, big, thick, long, and clean, while the back crow is high, thick, long, straight, and clean [68]. The duration of the Bekisar crowing is approximately 3 s [74,75] (Figure 2).

Bekisar roosters (source: Azis, 2023).

Besides its crowing sound, the beauty of the color of Bekisar plumage is frequently used as one of the criteria in the Bekisar competition [76]. The genetic diversity and haplotype distribution of Bekisar chickens were strongly influenced by breeding schemes to develop this breed [20]. For example, the color of Bekisar depends on the color of the female chicken used in crossing [67], while the body posture, character, and sound are very dependent on the male [76]. In the past, only red and black were appreciated by Bekisar enthusiasts. Currently, the color of Bekisar has been very diverse after many breeders bred male junglefowl with various female local chickens of various colors, such as Cemani [67]. For instance, a Bekicem is produced by crossing a female Cemani chicken (fibromelanosis phenotype) with a male green junglefowl, resulting in all-black-colored chickens [77]. Another variant of Bekisar is the Bekikuk, which is a result of crossing male Bekisar with female domestic chicken. This variant is categorized as a light Bekisar [21]. A Bekikuk has a similar appearance and crowing sound to Bekisar [77].

3.2 Kokok Balenggek chickens

Kokok Balenggek chicken is developed in Payung Sakaki sub-district, Solok Regency, West Sumatra. This chicken is designated as the mascot of Solok Regency [78]. Kokok Balenggek is produced through a natural cross between the Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus) and Kampung chicken, the most common local chicken in Indonesia [76]. According to the legend that developed in the community, the Kokok Balenggek chicken is a descendant of the chicken that lived in the days of the Minangkabau kingdom in West Sumatra. The chickens have a tiered rhythmic crowing sound that cannot be found anywhere else in the world [73]. Balenggek is a Minangkabau language, which in Indonesian means tiered. The rooster produces a long crowing rhythm and then ends with an intermittent sound.

In general, the crowing sounds of local chickens in Indonesia consist of four syllables, while Kokok Balenggek has a crowing sound of more than four syllables and generally ranges from 6 to 15 syllables or more (up to 24 syllables). The more crowing syllables, the longer the crowing sound and the higher the selling value of these chickens [71]. The crowing sound of the Balenggek cock is divided into three parts: the beginning, middle, and end. The crowing frequency of the Balenggek cocks ranges from 5 to 11 or an average of 6.57 times with the number of syllables 8–14. In the morning, this rooster can crow 9.59 times in 10 min [79]. The time may affect the crowing duration [80]. Roosters tend to sing longer in the mornings than in the afternoons and days. Balenggek crows for 2.08–4.43 s for an average of 3.02 s [72]. The average crowing duration of all types ranged from 2.87 ± 0.45 to 3.33 ± 0.28 s [81,82].

The phenotypic characteristics of Balenggek (Figure 3) are like other local chickens such as Kampung chickens [76]. However, based on their body shapes, the Balenggek chickens are divided into three variants, namely Yungkilok Gadang, Ratiah, and Batu. Yungkilok Gadang is sturdy, dashing, and beautiful and has a body weight of 2 kg for an adult rooster, while the female is 1.5 kg. Ratiah is smaller and slimmer, with a weight of 1.6 kg for an adult male and 0.8 kg for a female chicken. Batu chicken has short legs (3–4 cm) and weighs 1.8 kg for an adult rooster and 1 kg for a female [83].

Kokok Balenggek roosters (source: Rusfidra, 2021).

The Kokok Balenggek chicken is endemic because its distribution area is limited to the Solok area and is not found in other areas [76]. It was reported that there were 354 birds identified in 1997, which were prone to extinction due to many migrations [72]. The total population of Kokok Balenggek in the in situ area was 1,960 chickens, with an actual population of 610 chickens, an effective population of 600 chickens, and an inbreeding rate of 0.08%. Therefore, it is required to improve conservation strategies for this chicken [84].

3.3 Gaga or Ketawa chickens

Gaga chicken was developed by the people in Sidrap, Pinrang, Enrekang, Parepare, and Barru of South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. These areas are still the central population for Ketawa chickens. The chickens were initially reared by aristocrats in South Sulawesi for social status [85]. However, now, these chickens have been reared throughout Indonesia [86,87]. Many hobbyists outside Sidrap raise Gaga chickens individually or in groups due to the growing number of singing chicken contests and the difficulty of trading and transporting animals between regions. There are many people on Java Island who have developed Gaga chicken farms, such as in Jakarta, Bogor, Yogyakarta, and Bangkalan [87].

The crowing sound of Gaga chickens is like human laughter, so they were named Ketawa chickens [85,86,88,89]. Ketawa means laughter in the Indonesian language. The unique crowing of Gaga has a different sound duration and the number of crowing syllables from other long-crowing chickens, and the crowing is classified into slow and dangdut types. Dangdut types can be divided into long and short groups [85]. Bioacoustic analysis on Gaga chickens showed that slow and dangdut types had different syllables at the end of the crow. The slow type has a short and slow crowing, while the dangdut type has a long and fast crowing [86]. Chickens that are categorized as long dangdut type can reach 30 s in crowing with more than 140 syllables [85,90]. The slow dangdut type can crow for 4 s, while the slow type can crow for 3.65 s [90]. The number of syllables for slow dangdut ranged from 4 to 7 syllables [86] to more than 20 syllables [90]. The slow type produces 3–5 [86] to 8 syllables [90]. A study showed that the syrinx morphometrics of the dangdut type and the slow type were similar, while the trachea muscle morphometrics of the dangdut type were longer than the slow type [91]. Polymorphism analysis indicated that the dangdut and slow types are homozygotic [92].

The external performances of Gaga chickens (Figure 4) were not specific because they were almost like other local chickens [85,93]. The feather color combinations of Gaga chickens were black, whitish-black, brown, and blackish-brown. It was also found in other feather color combinations, which are usually discovered in other types of chickens, especially in roosters [93].

Ketawa roosters (source: Bugiwati, 2023; Asmara, 2023).

3.4 Pelung chickens

Pelung chickens were developed in Cianjur Regency, West Java. The long and melodious sound of the Pelung chicken has become an integral part of the culture of the agrarian society of Cianjur. It is believed that a religious leader in Cianjur was the first to develop Pelung chickens [94]. Pelung chickens were presumed to be a genetic variant of junglefowl in Java, in particular red junglefowl [16]. The birds have the same cluster as other local chickens such as Kampung, Sentul, and Black Kedu. However, Pelung has distant kinship with these local chickens [95]. Pelung chickens have a close kinship with Bekisar and the establishment of the Pelung chicken breed is second only to Bekisar [21].

The name Pelung comes from the Sundanese word “malewung” or “melung” which means that Pelung’s crowing can be heard from a distance [23]. “Melung” also refers to the characteristic of Pelung crowing, which is long, undulant, loud, and rhythmic. At first glance, Pelung crows like other local chickens but the roosters have longer crowing with a prolonged end [77,96]. The crowing of Pelung is divided into three syllables which consist of initial, mid, and end sounds. The crowing of a Pelung can last 11 s [97]. However, nowadays the duration of Pelung crowing is decreasing to an average of 8 s [72,98,99]. The crowing sound of Pelung can be classified based on its loudness including low (kukulir), medium (kukulur), loud (kukudur), and a combination of other kinds of loudness (tetelur). In addition, the crowing sounds can differ based on the sound melody including Balem, the sound produced by nose exhalation; Lunyu, the sound produced in a combination of nose and mouth exhalation; and the standard sound which is very loud [49]. Pelung enthusiasts believed that the crowing ability of Pelung chickens was hereditary [100]. It is reported that the crossbred Pelung and commercial broilers produced non-singer chickens [77].

In the beginning, Pelung was only reared by the community and religious leaders in Cianjur. Currently, Pelung has spread to various regions in West Java, as well as in almost all regions in Indonesia. One of the causes of the spread of Pelung is the proliferation of contests held both at the local and national levels. Pelung enthusiasts perceived chicken contests as a marketplace to find good breeds, and as a medium to increase their knowledge about the Pelung management system [101]. The winning roosters would have a high price and their fertile eggs and/or offspring would also be highly prized [102]. In the contest, Pelung roosters compete to win the singing and performance categories. A bird that has a longer crowing duration and distinct crowing characteristics would win contests. A rooster with a minimum body weight of 5,000 g and color uniformity of its plumage, beak, and shank would excel in the competition [102,103].

In general, adult male Pelung chickens (Figure 5) have a single comb with a combination of black and red plumage [103], while adult female Pelung chickens have black plumage [97,104]. Compared to other local chickens, Pelung chicken has a taller and bigger posture. They can reach 3,500 g in weight for an adult rooster, and 2,050 g in weight for an adult hen [97]. This characteristic can be used for meat production. It is reported that crossbred Pelung and Kampung chickens result in improved local chickens with better production performance [94,105,106,107].

Pelung roosters (source: Garnida, 2023).

4 The importance and conservation of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia

The existence of AnGRs is essential for food production and livelihood mainly in developing countries. They are also closely linked with the socio-cultural of particular communities [1,3]. The economic importance of long-crowing chickens is embedded in their capability of crowing. The singing contest, in particular a singing contest for Pelung chickens, has been a dominant factor that increases the economic value of long-crowing chickens. The winners of the contest together with their offspring would be priced higher than the non-winners [102]. However, a decreased genetic capacity of Pelung was reported [100,103].

The decline in the population including the decreased genetic capacity of AnGRs has occurred in the last few decades. A total of 17% of all breeds reported to the Food and Agriculture Organization are classified as being at risk and chicken breeds are the most at risk among avian species. Furthermore, the percentage of breeds classified as being of unknown risk status has increased [3]. The lack of data availability such as population data is the main issue in determining breed risk status, mainly in developing countries [1] including Indonesia [98]. Scholars presumed that the population of Indonesian local chickens is in decline [108–110], yet the support to prove this assumption is far from complete [102]. Attempts to determine the data population for crowing chickens have been conducted by limited researchers [84,111–113]. Also, some studies have indicated the decreasing genetic capacity of long-crowing chickens [98–100].

The breeds at risk require conservation actions [1]. The Indonesian Agriculture Ministry decree in 2011 declared that Pelung, Kokok Balenggek, and Gaga chickens were in the category of germplasm of Indonesia that need conservation. The common method applied in conservation is in situ and ex situ programs [1]. In situ conservation includes the production of breeds in their original production environment. Ex situ conservation maintains breeds outside their original environment including the preservation of live animals (in vivo) and cryopreservation of genetic material (in vitro). The implementation of the conservation method should reveal actual difficulties and challenges [114]. In situ conservation was found in countries that have higher proportions of breeds at risk [6]. In situ programs are less costly and consider the livelihoods of the keepers as well as the social and cultural values of the community [1,3]. This conservation might be put in the priority for the conservation of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia which are not separable from the local communities in which these chickens developed.

The government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) may act for the conservation of the breed at risk [1]. The NGO includes breeder associations, NGOs, universities, and research centers. In terms of long-crowing chickens, the breeder association, and the enthusiasts play important roles in preserving these breeds. For example, the distribution of Pelung chickens is inseparable from the role of the association of breeders who regularly organize contests both on a local and national scale. There was a need to provide incentives for the association and enthusiasts as conservation agents [102]. The incentives through payment would increase the benefits of maintaining local AnGRs through voluntary reward mechanisms [115]. A study to explore conservation participation for Pelung chickens showed that the keepers were open to financial incentives to designate maintaining the breeds into the future [102]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first on the reward mechanism for long-crowing chicken conservation in Indonesia.

The availability of data on long-crowing chickens in Indonesia is still limited. Population number and population distribution are important data. Information on population data is very essential to determine the extinction rate of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia. All the long-crowing chickens in Indonesia are classified as having unknown levels of risk of extinction [116]. If a breed is not at risk, active conservation is not necessary. The breed might need an improvement program to respond to, for instance, changing market conditions. If a breed is determined to be at risk, active conservation strategies must be implemented [1]. Hence, determining the risk of extinction of the long-crowing chickens in Indonesia is vital to define the appropriate approach to preserving these breeds. Surveys on population numbers and their dynamics, as well as the establishment of risk levels and applicable techniques for monitoring populations, are required.

Another important datum is local knowledge including keeping practices and local terms in raising these chickens. Generally, the rearing practices for local chickens in Indonesia can be divided into extensive, semi-intensive, and intensive systems [100]. These categories are developed based on the types and levels of inputs. These inputs include housing, feed, and health maintenance, as well as time provided by the keepers. For example, in a semi-intensive system, chickens are partly confined and fed by crop residues, grains, and kitchen waste. In this system, modern combined with ethno-veterinary treatments are common practices to maintain the health of the flocks. Semi-intensive systems dominated the rearing practices for Pelung chickens [102]. The breeders were reluctant to vaccinate their chickens and relied on ethnoveterinary medicine for preventing and curing chicken diseases [117]. There is a lack of information on rearing techniques to optimize the singing ability of long-crowing chickens; hence, studies on establishing standards of rearing practices for this type of chicken are needed.

AnGR breeds are selected based on the needs and conditions of the agro-climatic area and have been developed based on the interests, adaptation, and availability of resources in the area. These conditions form local practices that are in harmony with social and physical conditions and regional resources. These local practices are indispensable to the preservation of a breed of livestock [118]. Local knowledge in the preservation of AnGRs is generally related to breeding objectives and breeders’ preferences for certain traits as well as breeding and selection practices to obtain desired traits [119]. This knowledge is usually owned by certain people. For example, the information about the crowing and good Pelung characteristics is mastered by a limited number of people, such as the juries in the Pelung chicken contest and Pelung breeders. Local knowledge is generally not well documented and is passed down verbally from one generation to the next. In general, local knowledge has developed through years of experimentation in the daily lives of chicken breeders and enthusiasts, so it is very important to document it to align with a scientific approach to preserving long-crowing chickens.

All long-crowing chickens in Indonesia, in particular the Kokok Balenggek, Gaga, and Pelung chickens, have the same phenotypic characteristics. This is because they are presumed to have the same ancestry. The phenotypic characteristics of these chickens are frequently associated with Kampung chickens. Kampung chickens are local chickens that have a high population and are spread across villages (kampung) in Indonesia. Kampung chickens are classified as non-descript chickens considering their non-specific plumage color. The main difference between Kampung chickens and long-crowing chickens is their crowing. Information about the mechanism of selecting chickens with unique crowing is still unknown. However, it is argued that the purpose of breeding certain breeds is in harmony with the existing culture [119]. Therefore, the conservation of long-crowing chickens should consider the sociocultural values of the community.

The conservation of genetic resources needs justification from an economic view. The values of AnGR can be conceived through total economic value (TEV). The TEV is generally divided into use and non-use values that can account for the conservation of biodiversity [120]. Even though long-crowing chickens have direct value as protein sources, most keepers raise these chickens for non-direct value through their long-crowing sounds. Local breeds including long-crowing chickens have received much attention from scientists from both universities and research centers; however, the research mainly focuses on developing local breeds as protein sources (use-values). Since long-crowing chickens are a genetic pool, it is also important to study the non-use values of these chickens. People might value the existence of long-crowing chickens even though they never use them directly or future generations might benefit from these breeds. These values are significant to explore as justification for the conservation of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia.

The conservation plan for long-crowing chickens is generally still at a hypothetical level, as suggested by a few researchers in Indonesia. As their studies are limited to specific chickens in different areas, collaborative studies are needed among scholars to shed light on the importance of long-crowing chickens as part of biodiversity in Indonesia. Multidisciplinary approaches are also required to conserve these chickens for future generations and maintain the cultural value of the community. The government’s role is crucial in facilitating studies through, for example, providing funds and access to research facilities.

5 Conclusions

The crowing of the chickens cannot be learned through imitation. Crowing is a testosterone-dependent activity and some genes that are presumed to be responsible for this activity have been characterized. Long-crowing chickens in Indonesia shared the same ancestors and have similar phenotypic characteristics. However, they have different crowing characteristics due to their development in different regions in Indonesia. The rhythm and harmony of each crowing sound can only be enjoyed by chicken enthusiasts and breeder associations. However, the chickens can be distinguished through the quantitative characteristics of their crowing (Table 1). The existence of the breeds is closely related to the socio-cultural environment in which they developed. The government has declared that the breeds are genetic resource assets, yet the conservation action relies on the existence of the association and individual keepers. There are still a few researchers who are interested in conducting studies on long-crowing roosters. It is very important to explore the population number and its distribution, the economic values as well as the documentation of the local knowledge of chicken breeders and enthusiasts, as inputs for conservation.

Characteristics of long-crowing chickens in Indonesia

| Characteristics | Breed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bekisar | Kokok Balenggek | Gaga/Ketawa | Pelung | |

| Origin | East Java | West Sumatra | South Sulawesi | West Java |

| Crowing duration (s) | 3 [74] | 2.87 ± 0.45–3.33 ± 0.28* [81] | 3.68 ± 1.08; 4.20 ± 1.80; 30.83 ± 19.67* [85] | 8.56 ± 1.53 [98] 9.00 ± 1.80 [99] |

| Syllable numbers | 2 [68] | 6.30 ± 1.06–12.48 ± 3.58* [81] | 8.27 ± 2.58; 20.94 ± 9.52; 140.92 ± 90.22* [90] | 3 |

| External characteristics (plumage) | Blackish-green [66] | Not specific | Not specific | Not specific |

| Body weight | 1.5–2.5 kg** [121] | 1.6–2 kg (male); 0.8–1.5 kg (female) [83] | 1.6–1.8 kg (male) [86] | 3.5 kg (male); 2.05 kg (female) [97] |

*Depends on the type of chickens; **mixture between male and female chickens.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universitas Padjadjaran for granting the Hibah Riset Unpad (HRU) Grant.

-

Funding information: This study was funded by the Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia, through Hibah Riset Unpad (HRU).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization. The state of the world’s animal genetic resources for food and agriculture. Rome: FAO; 2007. p. 511.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Food and Agriculture Organization [Internet]. Rome: FAO; c2023 [cited 2023 May 20]. Domestic Animal Diversity Information System (DAD-IS): Key facts. https://www.fao.org/dad-is/en/.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Food and Agriculture Organization. The second report on the state of the world’s animal genetic resources for food and agriculture: in brief. Rome: FAO; 2015. p. 12.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Paiva SR, McManus CM, Blackburn H. Conservation of animal genetic resources–A new tact. Livest Sci. 2016;193:32–8. 10.1016/j.livsci.2016.09.010.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Food and Agriculture Organization. In vivo conservation of animal genetic resources. FAO animal production and health guidelines. No. 14. Rome: FAO; 2013. p. 242.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Cao J, Baumung R, Boettcher P, Scherf B, Besbes B, Leroy G. Monitoring and progress in the implementation of the global plan of action on animal genetic resources. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):775. 10.3390/su13020775.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Seré C, van der Zijpp A, Persley G, Rege E. Dynamics of livestock production systems, drivers of change and prospects for animal genetic resources. Anim Genet Resour Inf. 2008;42:3–24. 10.1017/S1014233900002510.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Liu YP, Wu GS, Yao YG, Miao YW, Luikart G, Baig M, et al. Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;38(1):12–9. 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Hoffmann I. Climate change and the characterization, breeding and conservation of animal genetic resources. Anim Genet. 2010;41:32–46. 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02043.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Semik E, Krawczyk J. The state of poultry genetic resources and genetic diversity of hen populations. Ann Anim Sci. 2011;11(2):181–91.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hata A, Nunome M, Suwanasopee T, Duengkae P, Chaiwatana S, Chamchumroon W, et al. Origin and evolutionary history of domestic chickens inferred from a large population study of Thai red junglefowl and indigenous chickens. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–15. 10.1038/s41598-021-81589-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Komiyama T, Ikeo K, Tateno Y, Gojobori T. Japanese domesticated chickens have been derived from Shamo traditional fighting cocks. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;33(1):16–21. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.04.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Komiyama T, Lin M, Ogura A. aCGH Analysis to estimate genetic variations among domesticated chickens. Biomed Res Int. 2016;1–8. 10.1155/2016/1794329.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Bortoluzzi C, Crooijmans RPMA, Bosse M, Hiemstra SJ, Groenen MAM, Megens H. The effects of recent changes in breeding preferences on maintaining traditional Dutch chicken genomic diversity. Heredity. 2018;121:564–78. 10.1038/s41437-018-0072-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Wood-Gush DGM. A history of the domestic chicken from antiquity to the 19th century. Poult Sci. 1959;38(2):321–6. 10.3382/ps.0380321.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Fumihito A, Miyake T, Sumi SI, Takada M, Ohno S, Kondo N. One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices as the matriarchic ancestor of all domestic breeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91(26):12505–9. 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12505.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Fumihito A, Miyake T, Takada M, Shingu R, Endo T, Gojobori T, et al. Monophyletic origin and unique dispersal patterns of domestic fowls. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93(13):6792–5. 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6792.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Miao YW, Peng MS, Wu GS, Ouyang YN, Yang ZY, Yu N, et al. Chicken domestication: an updated perspective based on mitochondrial genomes. Heredity. 2013;110(3):277–82. 10.1038/hdy.2012.83.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Peters J, Lebrasseur O, Irving-Pease EK, Paxinos PD, Best J, Smallman R, et al. The biocultural origins and dispersal of domestic chickens. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(24):e2121978119. 10.1073/pnas.2121978119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Komiyama T, Ikeo K, Gojobori T. The evolutionary origin of long-crowing chicken: its evolutionary relationship with fighting cocks disclosed by the mtDNA sequence analysis. Gene. 2004;333:91–9. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Ulfah M, Perwitasari D, Jakaria J, Muladno M, Farajallah A. Multiple maternal origins of Indonesian crowing chickens revealed by mitochondrial DNA analysis. Mitochondrial DNA A. 2017;28(2):254–62. 10.3109/19401736.2015.1118069.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Nataamijaya AG. The native chicken of Indonesia. BNP. 2000;6(1):1–6. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[23] Sulandari SRI, Zein MSA, Sartika T. Molecular characterization of Indonesian indigenous chickens based on mitochondrial DNA displacement (D)-loop sequences. HAYATI J Biosci. 2008;15(4):145–54. 10.4308/hjb.15.4.145.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Godinez CJP, Layos JKN, Yamamoto Y, Kunieda T, Duangjinda M, Liao LM, et al. Unveiling new perspective of phylogeography, genetic diversity, and population dynamics of Southeast Asian and Pacific chickens. Sci Rep. 2022;12:14609. 10.1038/s41598-022-18904-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Matsunaga E, Okanoya K. Evolution and diversity in avian vocal system: An Evo‐Devo model from the morphological and behavioral perspectives. Dev Growth Differ. 2009;51(3):355–67. 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2009.01091.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Brenowitz EA. Evolution of the vocal control system in the avian brain. Semin Neurosci. 1991;3(5):399–407.10.1016/1044-5765(91)90030-RSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Karaman M, Kirdag N. Mitochondrial DNA D-loop and 12S regions analysis of the long-crowing local breed Denizli fowl from Turkey. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg. 2012;18:191–6. 10.9775/kvfd.2011.5248.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Doupe AJ, Kuhl PK. Birdsong and human speech: Common themes and mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22(1):567–631. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.567.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Singh R, Lehana P, Singh G. Investigations of the phonemes in the calls of little owls using vector quantization. Int J Inf Technol Knowl Manag. 2009;2(2):337–42.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Wallschläger D. Correlation of song frequency and body weight in passerine birds. Experientia. 1980;36(4):412. 10.1007/BF01975119.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Brackenbury JH. Respiratory mechanics of sound production in chickens and geese. J Exp Biol. 1978;72(1):229–50. 10.1242/jeb.72.1.229.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Wada M. Circadian rhythms of testosterone-dependent behaviors, crowing and locomotor activity, in male Japanese quail. J Comp Physiol A. 1986;158(1):17–25. 10.1007/BF00614516.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Queiroz SA, Cromberg VU. Aggressive behavior in the genus Gallus sp. Brazilian. J Poult Sci. 2006;8(1):1–14. 10.1590/S1516-635X2006000100001.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Shimmura T, Tamura M, Ohashi S, Sasaki A, Yamanaka T, Nakao N, et al. Cholecystokinin induces crowing in chickens. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–7. 10.1038/s41598-019-40746-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Shimmura T, Yoshimura T. Circadian clock determines the timing of rooster crowing. Curr Biol. 2013;23(6):R231–3. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Shimmura T, Ohashi S, Yoshimura T. The highest-ranking rooster has priority to announce the break of dawn. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11683. 10.1038/srep11683.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Leonard ML, Horn AG. Crowing in relation to status in roosters. Anim Behav. 1995;49:1283–90. 10.1006/anbe.1995.0160.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Mench JA, Ottinger MA. Behavioral and hormonal correlates of social dominance in stable and disrupted groups of male domestic fowl. Horm Behav. 1991;25(1):112–22. 10.1016/0018-506X(91)90043-H.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Warren WC, Clayton DF, Ellegren H, Arnold AP, Hiller LW, Künstner A, et al. The genome of a songbird. Nature. 2010;464(7289):757–62. 10.1038/nature08819.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Haesler S, Wada K, Nshdejan A, Morrisey EE, Lints T, Jarvis ED, et al. FoxP2 expression in avian vocal learners and non-learners. J Neurosci. 2004;24(13):3164–75. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4369-03.2004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Haesler S, Rochefort C, Georgi B, Licznerski P, Osten P, Scharff C. Incomplete and inaccurate vocal imitation after knockdown of FoxP2 in songbird basal ganglia nucleus Area X. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(12):e321. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050321.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Wang X, Li H, Hamid MA, Zhao X. Differential expression of Forkhead box protein P2 between genders in chickens. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11(58):12153–7. 10.5897/AJB12.130.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Teramitsu I, Poopatanapong A, Torrisi S, White SA. Striatal FoxP2 is actively regulated during songbird sensorimotor learning. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8548. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008548.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Vicario A, Mendoza E, Abellán A, Scharff C, Medina L. Genoarchitecture of the extended amygdala in zebra finch, and expression of FoxP2 in cell corridors of different genetic profile. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:481–514. 10.1007/s00429-016-1229-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Xiao L, Merullo DP, Koch TMI, Cao M, Co M, Kulkarni A, et al. Expression of FoxP2 in the basal ganglia regulates vocal motor sequences in the adult songbird. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2617. 10.1038/s41467-021-22918-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Fisher SE, Scharff C. FOXP2 as a molecular window into speech and language. Trend Genet. 2009;25:166–77. 10.1016/j.tig.2009.03.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Enard W. FOXP2 and the role of cortico-basal ganglia circuit in speech and language evolution. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:415–24. 10.1016/j.conb.2011.04.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Wohlgemuth S, Adam I, Scharff C. FoxP2 in songbirds. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;28:86–93. 10.1016/j.conb.2014.06.009.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Daryono BS, Mushlih M, Perdamaian ABI. Vocalization characters and forkhead box P2 (FoxP2) polymorphism in Indonesian crowing-type chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus). Iran J Appl Anim Sci. 2020;10(1):131–40.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Mello CV, Ribeiro S. ZENK protein regulation by song in the brain of songbirds. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:426–38. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980420)393:4<426::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-2.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Thode C, Bock J, Braun K, Darlison MG. The chicken immediate-early gene zenk is expressed in the medio-rostral neostriatum/hyperstriatum ventrale, a brain region involved in acoustic imprinting, and is up-regulated after exposure to an auditory stimulus. Neuroscience. 2005;130:611–7. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.015.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Nordmann GC, Malkemper EP, Landler L, Ushakova L, Nimpf S, Heinen R, et al. A high sensitivity ZENK monoclonal antibody to map neuronal activity in Aves. Sci Rep. 2020;10:915. 10.1038/s41598-020-57757-6.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Liu WC, Nottebohm F. Variable rate of singing and variable song duration are associated with high immediate early gene expression in two anterior forebrain song nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(30):10725–9. 10.1073/pnas.0504677102.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Long KD, Kennedy G, Salbaum MJ, Balaban E. Auditory stimulus-induced changes in immediate-early gene expression related to an inborn perceptual predisposition. J Comp Physiol A. 2002;188:25–38. 10.1007/s00359-001-0276-4.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Kubikova L, Wada K, Jarvis ED. Dopamine receptors in a songbird brain. J Comp Neuro. 2010;518:741–69. 10.1002/cne.22255.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Robertson D, Biaggioni I, Burnstock G, Low PA, Paton JFR, editors. Primer on the autonomic nervous system. 3rd edn. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; 2012. 10.1016/C2010-0-65186-8.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Bosíková E, Košťál L, Cviková M, Bilčík B, Niederová-Kubíková L. Song-related dopamine receptor regulation in Area X of zebra finch male. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2012;31:291–8. 10.4149/gpb_2012_034.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Sekiguchi T. Cholecystokinin. In: Takei Y, Ando H, Tsutsui K, editors. Handbook of hormone comparative endocrinology for basic and clinical research. Oxford: Academic Press; 2016. p. 177–78.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Lovell PV, Mello CV. Brain expression and song regulation of the cholecystokinin gene in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). J Comp Neurol. 2011;519(2):211–37. 10.1002/cne.22513.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Wan Y, Deng Q, Zhou Z, Deng Y, Zhang J, Li J, et al. Cholecystokinin (CCK) and its receptors (CCK1R and CCK2R) in chickens: Functional analysis and tissue expression. Poult Sci. 2022;102(1):1–11. 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102273.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[61] Panksepp J, Burgdorf J, Beinfeld MC, Kroes RA, Moskal JR. Regional brain cholecystokinin changes as a function of friendly and aggressive social interactions in rats. Brain Res. 2004;1025(1–2):75–84. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Zwanzger P, Domschke K, Bradwejn J. Neuronal network of panic disorder: The role of the neuropeptide cholecystokinin. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(9):762–74. 10.1002/da.21919.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Singh RS, Kulathinal RJ. Polymorphism. In: Maloy S, Hughes K, editors. Brenner’s encyclopedia of genetics. 2nd edn. Oxford: Academic Press; 2013. 398–9.10.1016/B978-0-12-374984-0.01189-XSearch in Google Scholar

[64] Johnson AD, Wang D, Sadee W. Polymorphisms affecting gene regulation and mRNA processing: Broad implications for pharmacogenetics. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;106:19–38. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.11.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Pastinen T, Ge B, Hudson TJ. Influence of human genome polymorphism on gene expression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(1):R9–16. 10.1093/hmg/ddl044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Rusfidra, Arlina F. A review of “long crower chickens” as poultry genetic resources in Indonesia. Int J Poult Sci. 2014;13(11):665–9. 10.3923/ijps.2014.665.669.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Hadiwirawan E. Preservation of Junglefowl through the establishment of Bekisar chickens for fancy livestock. Prosiding Lokakarya Nasional Inovasi Teknologi Pengembangan Ayam Lokal. Semarang; 2004. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[68] Tarigan N, Hermanto S. Modern maintenance and breeding. Yogyakarta: Kanisius; 1991. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[69] Nataamijaya AG. Application of artificial insemination technique in ex-situ conservation of wild fowl. Bul Plasma Nutfah. 2000;6(2):7–9. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[70] Zein MSA, Sulandari S. Genetic population structure of green jungle fowls using D-loop hypervariable-1 of mitochondrial DNA. Biota. 2008;13(3):182–90. 10.24002/biota.v13i3.2573. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[71] Rusfidra. Development of bioacoustic research in Indonesia: Studies on Balenggek Crowing, Pelung and Bekisar Chickens. In Seminar Nasional MIPA. Yogyakarta: 2006. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[72] Rusfidra. Bioacoustics’ assessment of the Balenggek crow chicken “The Local Sing Fowl” from West Sumatera. In Seminar Nasional Teknologi Peternakan dan Veteriner. Bogor: 2007. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[73] Rusfidra. Characterization of phenotypic traits as an initial conservation strategy for Balenggek crowing cocks in West Sumatra. Dissertation. Bogor: Sekolah Pascasarjana IPB; 2004. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[74] Selvia. Acoustic characteristics of Bekisar, Bangkok, Kate, Kampung, and Green Jungle Fowl (Gallus varius). Final Report. Bogor: Institut Pertanian Bogor; 2016. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[75] NTD Indonesia. Bekisar chickens, the most expensive chickens in the world) [video file]; 2009 Dec 16 [cited 2023 June 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vKWp_KlGluQ. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[76] Sartika T, Iskandar S, Tiesnamurti B. Indonesian local chicken genetic resources and its development prospects. Jakarta: IAARD Press; 2016. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[77] Daryono BS, Muslih M, Perdamaian ABI. Crowing sound and inbreeding coefficient analysis of Pelung chicken (Gallus Gallus domesticus). Biodiversitas. 2021;22(5):2451–7. 10.13057/biodiv/d220501.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Arlina F, Ahmad D, Afriani T, Nadina L. Morphogenetic characteristics of Balenggek crowing chicken in Tigo District, Lurah District, Solok Regency. JPI. 2007;12(1):12–7. 10.25077/jpi.12.1.12-17.2007. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[79] Rusfidra, Tumatra YY, Abbas MH, Heryandi Y, Arlina F. Characterization of number of crow and qualitative marker of Kokok Balenggek song fowl inside a captive breeding farm in Solok regency, West Sumatera Province, Indonesia. Int J Poult Sci. 2014;13(6):343–6. 10.3923/ijps.2014.343.346.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Rusfidra, Tumatra YY, Abbas MH, Heryandi Y, Arlina F. Identification of bioacoustic markers for the crowing of the Balenggek crow in the “Agutalok” breeding cages, Solok regency. J Peternak Indonesia. 2012;14(1):303–7. 10.25077/jpi.14.1.303-307.2012. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[81] Arlina F, Rusfidra, Andriano D, Sumantri C. Short communication: The type and sound diversity of Kukuak Balenggek chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) reared in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2020;21(5):1914–9. 10.13057/biodiv/d210518.Search in Google Scholar

[82] IDX CHANNEL. (Unique, AKB’s Melodious Balenggek Chicken) [video file]; 2021 Maret 8 [cited 2023 June 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wV1QGQG20tE. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[83] Rukmana RH. Local chicken intensification and development tips. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius; 2003. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[84] Husmaini, Putra RA, Juliyarsi I, Edwin T, Suhartati L, Alianta AA, et al. Population structure of Kokok Balenggek chicken in in-situ area as indigenous chicken of Indonesia. Adv Anim Vet Sci. 2022;10(5):993–8. 10.17582/journal.aavs/2022/10.5.993.998.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Bugiwati SRA, Ashari F. Crowing sound analysis of Gaga’chicken: Local chicken from South Sulawesi Indonesia. Int J Plant Anim Environ Sci. 2013;3(2):163–8.Search in Google Scholar

[86] Abinawanto A, Effendi PS. Biodiversity of the Gaga chicken from Pinrang, South Sulawesi, Indonesia based on the bioacoustic analysis and morphometric study. Biodiversitas. 2017;18(4):1618–23. 10.13057/biodiv/d180440.Search in Google Scholar

[87] Abinawanto A, Zulistiana T, Lestari R, Dwiranti A, Bowolaksono A. The genetic diversity of ayam ketawa (Gallus gallus domesticus, Linneaus, 1758) in Bangkalan district, Madura Island, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2021;22(6):3145–55. 10.13057/biodiv/d220617.Search in Google Scholar

[88] Abinawanto A, Effendi PS. The bioacoustics analysis and the morphometrics study of the Gaga’s chicken (ayam ketawa) from Pinrang and Kebayoran Lama. In AIP Conference Proceedings 22 October 2018. No. 1, AIP Publishing LLC; 2023. p. 020137. 10.1063/1.5064134.Search in Google Scholar

[89] TRANS OFFICIAL. (Uniquely KETAWA CHICKEN Ornamental Chicken with a Melodious Voice) | RAGAM INDONESIA (26/06/20) [video file]. 2020 June 26 [cited 2023 June 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUtzL2An5o8. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[90] Bugiwati SRA, Dagong MIA, Tokunaga T. Crowing characteristics of native singing chicken breeds in Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 492, No. 1, 2020. p. 012100. 10.1088/1755-1315/492/1/012100.Search in Google Scholar

[91] Abinawanto A, Sophian A, Efendi PS, Siswantining T. Variation in vocal cord morphometric characters among dangdut type and the slow type Gaga Chicken. Biodiversitas. 2018;19(5):1902–5. 10.13057/biodiv/d190542.Search in Google Scholar

[92] Abinawanto A, Sophian A, Lestari R, Bowolaksono A, Efendi PS, Afnan R. Analysis of IGF-1 gene in ayam ketawa (Gallus gallus domesticus) with dangdut and slow type vocal characteristics. Biodiversitas. 2019;20(7):2004–10. 10.13057/biodiv/d200729.Search in Google Scholar

[93] Bugiwati SRA, Syakir A, Dagong MIA. Phenotype characteristics of Gaga chicken from Sidrap regency, South Sulawesi. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 492, No. 1, 2020. p. 012103. 10.1088/1755-1315/492/1/012103.Search in Google Scholar

[94] Iskandar S, Susanti T. The characteristics and the use of pelung chicken in Indonesia. Wartazoa. 2007;17(3):128–36. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[95] Sartika T, Iskandar S, Prasetyo LH, Takahashi H, Mitsuru M. Genetic relationship between Kampung, Pelung, Sentul and black Kedu chickens using microsatellite DNA markers: I. Mapping groups on macrochromosomes. JITV. 2004;9(2):81–6. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[96] Unpad. (Chancellor’s Trophy Pelung Chicken Contest) [video file]. 2015 Sept 11 [cited 2023 June 30]. www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_a79t_HLxA. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[97] Nataamijaya AG. Appearance characteristics of the color patterns of feathers, skin, shanks, and beaks of Pelung chickens in Garut and Sentul chickens in Ciamis. Bul Plasma Nutfah. 2005;11(1):1–5. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[98] Asmara IY, Garnida D, Partasasmita R. Duration and volume of crowing of Pelung chickens of West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2020;21(2):748–52. 10.13057/biodiv/d210242.Search in Google Scholar

[99] Asmara IY, Garnida D, Partasasmita R. Crowing characteristics of Pelung chickens at different age and body weight. Biodiversitas. 2020;21(9):4339–44. 10.13057/biodiv/d210953.Search in Google Scholar

[100] Muladno. Local chicken genetic resources and production systems in Indonesia. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[101] Asmara IY, Garnida D, Sulistyati M, Tejaningsih S, Partasasmita R. Knowledge and perception of Pelung keepers toward chicken contests in West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2018;19(6):2232–7. 10.13057/biodiv/d190631.Search in Google Scholar

[102] Asmara IY. Risk Status of Selected Indigenous Chicken Breeds in Java, Indonesia: Challenges and Opportunities for Conservation. Dissertation. Darwin (NT) Australia: Charles Darwin University; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[103] Asmara IY, Garnida D, Setiawan I, Partasasmita R. Short Communication: Phenotypic diversity of male Pelung chickens in West Java Province, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2019;20(8):2243–8. 10.13057/biodiv/d200819.Search in Google Scholar

[104] Asmara IY, Garnida D, Tanwiriah W, Prtasasmita R. Qualitative morphological diversity of female Pelung Chickens in West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2019;20(1):126–33. 10.13057/biodiv/d200115.Search in Google Scholar

[105] Iskandar S. Pelung–Kampung crossed chicken: protein level ration for meat production at 12 weeks of age. Wartazoa. 2006;16(2):65–71. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[106] Habiburahman R, Darwati S, Sumantri C. Growth pattern of Pelung Sentul broiler crossbreed chicken (IPB D-1) g4 aged 1-12 weeks. JIPTHP. 2018;6(3):81–9. (Indonesian).10.29244/jipthp.6.3.81-89Search in Google Scholar

[107] Mahardhika I, Daryono BS. Phenotypic performance of kambro crossbreeds of female broiler cobb 500 and male pelung blirik hitam. Bul Vet Udayana. 2020;11(2):188–202. 10.24843/bulvet.2019.v11.i02.p12.Search in Google Scholar

[108] Diwyanto K, Prijono SN. Genetic Resources Diversity of Local Chickens in Indonesia. Jakarta: LIPI Press; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[109] Susanti T, Sopiyana S, Kostaman T, Sartika T, Prasetyo LH, Iskandar S, et al. Inventory and preservation of poultry genetic resources in West Java. Balai Penelitian Ternak dan Dinas Peternakan Provinsi Jawa Barat. Bogor, Indonesia; 2007. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[110] Susanti T, Sopiyana S, Sartika T, Prasetyo LH, Iskandar S, Sartika D, et al. Inventory and preservation of poultry genetic resources in West Java, continue. Balai Penelitian Ternak dan Dinas Peternakan Provinsi Jawa Barat. Bogor, Indonesia; 2008. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

[111] Rusfidra, Marajo SDT, Heryandi Y, Octaveriza B. Estimation of Inbreeding Rate in Kokok Balenggek Chicken (KBC) population under ex-situ conservation. Int J Poult Sci. 2014;13(6):364–7. 10.3923/ijps.2014.364.367.Search in Google Scholar

[112] Rusfidra, Gusrin Y, Abbas MH, Husmaini, Arlina F, Subekti K, et al. Flock composition, effective population size and inbreeding rate of Kokok Balenggek chicken breed under in-situ conservation. Int J Poult Sci. 2015;14:117–9. 10.3923/ijps.2015.117.119.Search in Google Scholar

[113] Asmara IY, Garnida D, Indrijani H. The population number of Pelung chickens in West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2022;23(7):3373–8. 10.13057/biodiv/d230708.Search in Google Scholar

[114] Tomka J, Huba J, Pavlík I. The state of conservation of animal genetic resources in Slovakia. Genet Resour. 2022;3(6):49–63. 10.46265/genresj.XRHU9134.Search in Google Scholar

[115] Narloch U, Drucker AG, Pascual U. Payments for agrobiodiversity conservation services for sustained on-farm utilization of plant and animal genetic resources. Ecol Econ. 2011;70(11):1837–45. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.05.018.Search in Google Scholar

[116] Food and Agriculture Organization [Internet]. Rome: FAO; c2023 [cited 2023 May 20]. Domestic Animal Diversity Information System (DAD-IS): breed data set. https://www.fao.org/dad-is/browse-by-country-and-species/en/.Search in Google Scholar

[117] Asmara IY, Garnida D, Sulisytati M, Tejaningsih S, Partasasmita R. Ethnoveterinary medicine and health management of Pelung Chicken in West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2018;19(4):1502–8. 10.13057/biodiv/d190441.Search in Google Scholar

[118] Bulcha GG, Dewo OG, Desta MA, Nwogwugwu CP. Indigenous Knowledge of Farmers in Breeding Practice and Selection Criteria of Dairy Cows at Chora and Gechi Districts of Ethiopia: An Implication for Genetic Improvements. Vet Med Int. 2022;2022:1–5. 10.1155/2022/3763724.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[119] Köhler-Rollefson I, Sansthan LP. Indigenous breeds, local communities: documenting animal breeds and breeding from a community perspective. Sadri, India: LPPS; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

[120] Pearce D, Moran D. The economic value of biodiversity. London, UK: Earthscan Publications Ltd; 1994.Search in Google Scholar

[121] cybex.pertanian.go.id (internet). (Get to know Bekisar chickens); c2013 (cited 2023 June 29). http://cybex.pertanian.go.id/artikel/52163/mengenal-ayam-bekisar/. (Indonesian).Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil