Abstract

This study examines the indirect and direct factors affecting the preference for distant travel of apple fruit (food miles or FMs) in Indonesia, a Muslim-majority country. This research employs a quantitative consumer survey of 522 respondents in Indonesia from January to February 2023. Data were collected online (i.e. via social media), and the respondents were chosen randomly. Data were then analysed using a partial least square-structural equation model to prove the proposed hypotheses using Rstudio. This investigation has some principal findings. First, domestic interest and health-environment benefits directly affect the preference for short food miles (SFMs). Second, the halal requirements do not directly affect the choice of SFMs but indirectly affect the preference for SFMs through health-environmental benefits. In sum, the choice for SFMs is affected by domestic interest (direct), health-environmental benefits (direct), and halal requirements (indirect). This study finally has a theoretical contribution to the interplay among green supply chain, halal food supply chain, and food security.

1 Introduction

Sustain Alliance introduced the food miles (FMs) or the length of food trips in their first report in 1994 in the UK that was republished in 2011 [1]. Proponents of FM reduction argue that reducing FMs contributes to a better life regarding the origin and destination of transported foods [1,2]. The recent studies of FMs highlight the importance of FM reduction. Because of the importance, some scholars are eager to compare local and imported foods. In Germany, it is found that locally grown apples have fewer primary energy requirements than apples imported from New Zealand [3]. In South Korea, consumers prefer domestic commodities to imported commodities when FM labels are provided [4]. A study on willingness to pay for short- and long-transported foods found that short-travelled foods are the most preferable [5]. Another study on consumer preference for two environmental labels (a label showing information on CO2 emission and a label showing information on the distance of travelled foods) found that consumers pay a higher price for products with CO2 labels than those with FM labels [6]. A product label showing FM information has better effects on consumer welfare than a product label showing CO2 emission [7].

A choice between longer food miles (LFM) and shorter food miles (SFM) is associated with the ability of a region to provide necessary foods for local people. A study found that the ability of local people to consume local foods varies; some regions can supply the foods for local people while others are unable [8]. The ability to provide sufficient food to local people is limited by distance and geographical coverage. Less than 28% of the global population can meet their demand for food within a radius of 100 km only [9]. It means that over 80% of the global population relies on food from long distances or importation. Thus, a debate on LFM and SFM is also related to the discourse of self-sufficiency (fulfilment of local demand with local foods) and food security (fulfilment of local demand with foods coming from anywhere, regardless of their country of origin) [10]. Food self-sufficiency was promoted by African countries in the Lagos Plan of Action in 1980 as their national development strategy to feed their citizens, even if the strategies were not seriously put into practice [10].

Because the previous studies on the consumer preference for FMs covered countries other than Indonesia, the study of FMs in the Indonesian context is promising. In this study, the apple fruit selected for studying consumer perception of FMs in Indonesia is for four reasons. First, apples are one of the world’s primarily grown fruits, contributing to food loss, waste (FLW), and emission along the supply chain [11,12,13]. Second, studies on the FMs of apples still need to be completed. For example, the previous study on the FMs of apple could have been more in-depth [14]. The study on the consumers’ willingness to pay for wine and apple fruit found a low demand for distantly transported commodities [5]. Third, Indonesia relies on imported apples [15]. Thus, studying the halal issue and FMs in Indonesia is crucial because the country is a Muslim majority and one of the largest halal food markets [16,17]. That is why Indonesia’s context differs from that of Muslim minority countries as a major locus of previous studies on FMs [2,3,4,5].

Fourth, apples are perishable and should be treated with chemical substances for preservation [18,19,20] along with long-distance transport and storage, so the halal status of the substances cannot be discovered. Using a non-halal chemical substance to treat the apples [18,19,20] is not allowed in Muslim society because it does not fulfil the halal requirements such as the wholesome/purity and safety principle (tayyib) [21,22]. The previous study on food safety and the halal–tayyib issue reveals that some halal agricultural commodities (e.g. chicken, fish and meat, fruits and vegetables, flavour, water, caviar, and cheese) are unable to be certified for halal because of non-wholesome (non-tayyib) and unsafe process [21]. In this perspective, the distance of the supply chain and the length of storage time of fruit certainly play a crucial role in maintaining the halal and tayyib condition of apples because the halal status of food can change from halal to non-halal along the end-to-end supply chain [23,24].

Based on the facts and argument above, this study aims to uncover the indirect and direct factors affecting the preference for FMs in the case of apple fruit. The preference for SFM is represented by the preference to purchase domestic food. The consumer preferences for foods from different sources determine the mileage of food travel to Indonesia’s consumption points.

Following the introductory importance of FMs of apple fruit, the article is structured: Section 2 discusses the literature review, Section 3 discusses materials and methods, Section 4 gives the results, Section 5 is a discussion, Section 6 discusses theoretical contribution, and Section 7 is the conclusion.

2 Literature review

FMs refer to the distance (in miles) that the foods travel from the point of origin (production) to the point of consumption, bearing some health, environmental, and economic burden [1]. All proponents of FMs agree that SFM is better for health, environment, society, and economy [1,6,7,8,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Thus, the concept of the FMs is different from supply chain segmentation, that is, the first mile, middle mile, and last mile [31].

Preferences for SFM are related to short food supply chains (SFSC) and local food preferences (LFPs). Many scholars have performed their studies on local food consumption, preferences, purchasing intention, and willingness to pay for local foods [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Other scholars prefer using the term SFSC, summarising that an SFSC means geographic and social proximity between producers and consumers [39].

Food localisation positively and negatively impacts a certain region. Some scholars identified a hundred positive and negative impacts of local dairy farming on the producing territories [40], and the impacts can be valid for local food growing in general and for apple farming in particular, as presented in Table 1.

Positive and negative impacts of locally growing foods on the territories

| Functions | Positive impacts | Negative impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Food supply |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Participation in rural vitality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

| Management of environmental quality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Preservation of cultural heritage and quality of life |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Previous study [40].

Given the different terms various scholars proposed, using local or domestic foods is preferable. The local or domestic term refers to “distance (in kilometres or miles),” “political boundaries,” or “emotional dimensions such as personal relationship with or within a region” [33]. Local or domestic foods are grown within political boundaries where consumers live [37]. Because the foods are produced in regions with the geographic proximity of consumers and producers, the food travel’s mileage falls. Preference to purchase domestic or local foods implies a preference for SFM. In the latter sections, this study exchangeably uses the terms preference for SFM and preference for purchasing domestic foods.

Whatever the terminology is used, people’s reliance on SFM depends on the ability of a region to supply food for the local community (the extent of self-sufficiency in a region) and LFP. Proponents of food self-sufficiency argue that domestic production is the only food source for domestic people and must be available nationally [10]. However, some countries have poor self-sufficiency ratios and highly rely on imports [9,41]. Under the failure of the self-sufficiency paradigm, food security becomes the relevant solution that stability of supply and better access to food to the national population are priorities that must be fulfilled by international market and aid [10,42], implying LFM. Under the food security paradigm, local demand can be fulfilled with foreign supply through international trade with the support of better logistics and supply chain management and better macroeconomic factors (e.g. exchange rate, energy price, financial market, and other macroeconomic factors) [42].

In addition, this study assumes that the choice of preference for LFM or SFM is determined by the consumers’ attitude regarding some factors, as presented in some of the following sub-sections.

2.1 Interest on the domestic economy

Preferences for SFM at least have two benefits for a domestic economy. First, SFM can empower local farmers and communities. A study found that belief or attachment to local communities (“local patriotism”) determines LFP in Norway; in contrast, empathy for the local food producers (“emphatic concern”) has an indirect effect on LFP [36]. Consumers buying artisan cheeses are associated with a willingness to help local communities [34]. Short-chained foods (SCF) have a higher proportion of price premiums than long-chained foods (LCF) [26]. The price premium was measured by the division of farm-gate price difference and the average price for farm gate to retail [26]. It implies that farmers benefit from the SFSC. A moral economy (measured with factors such as local farmers’ fair trade and support for a local farmer and economy) correlates with an SFSC [39].

Second, SFM contributes to the improved performance of the national economy. A study found that SCF has a higher chain value added than LCF [26]. An SFSC benefits local producers and promotes rural development through job creation [8]. The SFSC also promotes and gains from domestic trade [8]. The local food system development could encourage import substitution and economic development [43]. The domestic product consumption is tied to the patriotism of the domestic economy [44]. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

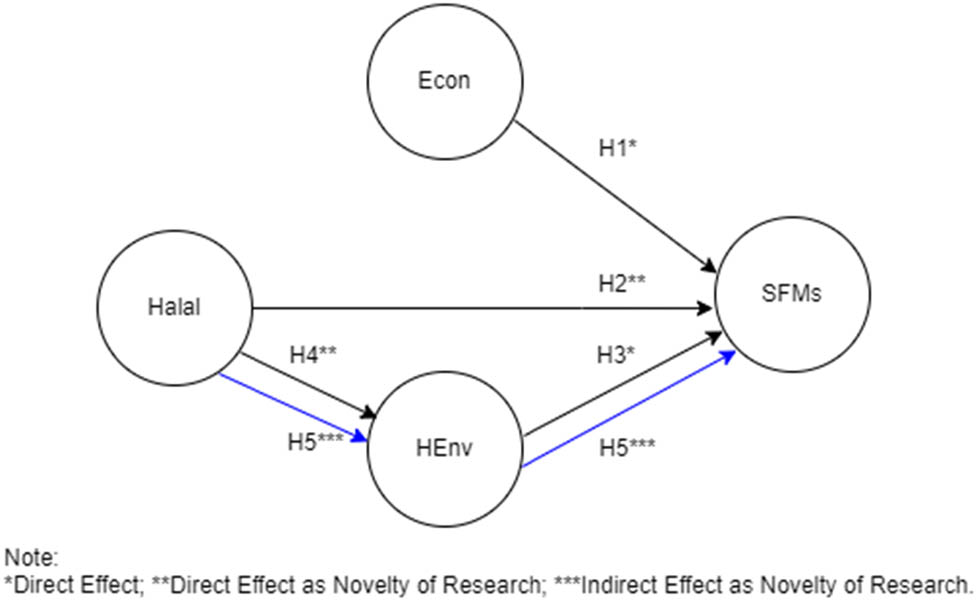

H1: Domestic-economy interest (Econ) has a direct effect on the preference for SFM.

2.2 Religious requirements in Muslim society as the societal element of the food system

Religious requirements are crucial in the food supply chain in a specific society. “Sustainable food value chain” operates in societal elements [45]. One of the variables of the societal elements is “informal sociocultural elements,” such as consumer preferences and religious requirements [45]. In Muslim society, keeping the halal integrity of the food supply chain from farm to fork is essential [23]. Regarding halal requirements, two variables are considered: the risk of non-halal contamination and the importance of halal certification.

The first indicator is the risk of non-halal contamination. The halal supply chain refers to three criteria: direct contact with non-allowed substances/materials (cross-contamination), risk of changing from halal to non-halal, and perception of Muslim consumers [46]. Apples risk non-halal contamination using chemical substances such as “1-methylcyclopropene, calcium chloride, melatonin, hydrogen sulphide, essential oils, lactic acid, and acetic acid” [19]. The other chemicals used in apples for preservation are materials-based shellac and carnauba-shellac, which are associated with a non-food grade for floor and car waxes [47]. According to Islamic law, the use of non-food grade is not wholesome or not tayyib (in the Arabic Language) because it does not meet the criteria of food safety and good quality [21,48]. Food safety refers to “all those hazards that may make the food injurious to the consumer’s health” [49]. Food additives are associated with health risks and halal issues [50]. Food quality is discussed in the next section.

The second indicator is the importance of mandatory halal certification. Muslims can only consume halal foods [51,52]. Some scholars emphasise the importance of maintaining halal integrity [23,53]. The availability of a halal logo determines purchasing intention [54]. Marketing factors, including the availability of halal certificates, affect consumer preference for meat products because the certificate shows the quality [55]. Consumers will consume food commodities when the certification is available, and the certificate implies food quality assurance [39]. From a halal perspective, a halal certificate shows the quality of the halal products and the enforcement of the quality [21,53]. Halal certification and standards guarantee food safety, sanitation, and hygiene regarding the production process [22]. In Nigeria, halal certification and quality affect the purchasing of halal products [56]. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Halal requirements (Halal) have a direct effect on the preference for SFM.

2.3 A benefit to the health and environment

FMs impact the health and environment. As described below, SFM can reduce the environmental problem through emission reduction, reduce FLW, and promote healthy foods. The first benefit is emission reduction. Most scholars concerning FMs discussed the environmental impact of LFM contributed by transport and cooling use [3,25,57,58]. A study compared CO2 emission from transport and cooling for domestically grown apples in Belgium and imported apples from Spain and New Zealand, finding that the imported apples produce more CO2 emission [58]. LCF has a higher share of producers’ carbon footprint than SCF, while SCF has a higher share of consumers’ footprint than LCF [26]. Local foods are environmentally sustainable because they require less packaging and transport, resulting in less greenhouse gas emission; however, expansion of farming for local consumption has negative impacts, such as high pesticide and fertiliser use and loss of biodiversity [8].

The second benefit is the reduction of FLW. Food loss refers to “the decrease in mass (dry matter quantity) or nutritional value (quality) of food that was originally intended for human consumption because of inefficient food supply chain, lack of technologies, the insufficient skill-knowledge-management capacity of supply chain actors, lack of market access, and natural disaster” [59]. Food waste refers to “food appropriate for human consumption being discarded because it is expired, left to spoil, or oversupply due to market, individual consumer, shopping/eating habits” [59]. The drivers of FLW in the food system are: the first is the agricultural production subsystems; the second is the food storage, transport, and trade subsystem; the third is the food retail and provision subsystem; the fourth is transformation and packaging process; and the fifth is consumer habit or handling by consumers [60].

The FLW occurs mainly in developed countries along the supply chain (e.g. production process, handling and storage, processing, distribution and market, and consumption) [61]. In Turkey, the fruit and vegetable sector is in the first place of FLW in the growing stage, the postharvest handling and storage stage, and the distribution stage [62]. In addition, fruit contributes to the largest share of food waste in the food service sector [62]. In the US, the FLW from vegetables is higher than from fruits and grains due to socio-economic improvement; thus, the strategies to reduce FLW are developed by adopting FM reduction and local food sourcing [63].

The third benefit is the promotion of healthy foods. The foods’ quality improves because SFM can minimise the FLW [59,60,64]. Food quality refers to foods meeting “all negative attributes (e.g. spoilage, contamination with filth, discolouration, and off-odours) and positive attributes (e.g. pure and origin, colour, flavour, texture, and processing method) that affect values of the products to the consumers” [49]. Some studies confirmed the importance of food quality. The nutritional content variable significantly affects the intention to purchase organic foods [65]. “Environmental consciousness” and “food quality” affect the purchasing intention of organic foods [66]. The perceived food quality is associated with the willingness to purchase domestic oysters in the Netherlands [67]. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Health-environmental benefits (HEnv) have a direct effect on the preference for SFM.

The previous studies on halal foods [21,48,50,56], local food and FMs [39,66], organic food [65], and FLW [49,64] have the concept in common. It is related to halal food safety (tayyib/wholesome) and healthy food. It is found that there is an implicit association among local food perception, SFMs, and characteristics of halal foods (e.g. wholesome, clean, no pesticides, organic and natural, quality and taste, fresh, transport distance quality of life, animal welfare, environmental concern, and health concern) [35]. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4: Halal requirements (Halal) have a direct effect on health-environmental benefits (HEnv).

H5: Halal requirements (Halal) have an indirect effect on the preference for SFMs through health-environmental benefits (HEnv).

Conceptual framework.

Based on the hypotheses, this study proposes the following research question: What factors affect consumer preferences for FMs of apple fruit (preference to purchase domestic apples) in Indonesia? The variables affecting the preference are presented in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Hypothetical factors that affect preference for SFM

| Construct | Variable | References |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic economy interest (Econ) | Local farmer empowerment (Econ_1) | [8,26,43,44] |

| National economy improvement (Econ_2) | [26,34,36,39] | |

| Halal requirements (Halal) | Possibility of non-halal chemical treatment of apples (Halal_1) | [19,21,46] |

| Mandatory Halal Certification (Halal_2) | [21,22,23,53] | |

| Health and environmental benefit (HEnv) | FLW Reduction (HEnv_1) | [59,61,63,64] |

| Reduction of fuel consumption, pollution, and emission (HEnv_2) | [8,26,58] | |

| Healthy Food (HEnv_3) | [35,49,65,67] |

3 Materials and methods

In the previous sections, research aims, hypotheses, and research questions were discussed. In this section, the research methods and data analysis to answer the hypotheses and research questions in the previous section are described. The relationship among research aims, hypotheses, research question, research methods, and data analysis is presented in Figure 2. In addition, the result, discussion, and conclusion are covered in the later sections.

Methodological procedure.

3.1 Research method

This article examines Indonesian consumers’ preferences for apple commodities with reduced FMs. This research employs a quantitative consumer survey, with data acquisition occurring in January–February 2023. Participants were chosen randomly, and data were collected online (i.e. via social media) to reach almost all parts of Indonesia. The selected respondents are those who consumed apples and are aware of the origin of the apples. The targeted respondents are assumed that they can share their experiences and reasons for purchasing apples by geographic origin. Five hundred twenty-two participants were duly sampled. The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and population in this study are presented in Table 3.

Descriptive of the sample (n = 522)

| Variables | Indonesia’s population (%) | Sample proportion (%) | Type of sample | Sample measurement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 49.5 | 45.0 | Categorical | Male (1) and female (2) |

| Male | 50.5 | 55.0 | |||

| Age | Age below 25 | 40.2 | 16.3 | Categorical | Less than 25 y.o. (1), 25–55 y.o. (2) over 55 y.o. (3) |

| Age 25–55 | 45.0 | 73.4 | |||

| Age above 55 | 15.8 | 10.3 | |||

| Religion | Muslim | 86.9 | 91.6 | Categorical | Muslim (1), non-Muslim (2), I do not want to mention (3) |

| Non-Muslim | 13.1 | 6.9 | |||

| I do not want to mention | — | 1.5 | |||

| Education | Senior High School or lower | 87.7 | 8 | Categorical | Senior high school or lower (1), College (2) |

| College | 12.3 | 92 | |||

| Income | <IDR 5 million | — | 28.9 | Categorical | <IDR 5 million (1), IDR 5–10 million (2), and >IDR 10 million (3) |

| IDR 5–10 million | — | 43.9 | |||

| >IDR 10 million | — | 27.2 | |||

Data in 2022: gender, age, and education; data in 2021: Religion; Education only covers the labour force even if some respondents are active students; Education category of samples is reclassified into two groups according to data availability in National Statistics. Source: Authors’ survey result [69,70].

The ratio of respondents in this study shows that most respondents are men (approximately 55%), which aligns with the population’s gender classification. In addition, most respondents fall between the ages of 25 and 55, which is also in line with the population’s age group. Most respondents – 90% – are Muslims, confirming Indonesia as a Muslim-majority country concerning halal issues. Most respondents – roughly 44% – are in the middle range for variable incomes and will pay for apple fruit from abroad [68]. On the educational side, most respondents have attained a bachelor’s degree or higher, contrasting with the proportion of the population’s education. It was found that education affects willingness to pay for apples [68]. It is assumed that educated people will consume apples.

The questionnaire in this work is divided into two sections: (1) basic information on the respondents; and (2) a scale for measuring the study variables. Also, the questionnaire consisted primarily of closed-ended queries utilising a five-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree; 5: strongly agree). The Likert scale of 1–5 was chosen because it allows responders to analyse each statement or question presented [71,72]. From now on, the respondent information includes gender, age, religion, education level, and income level, as stated in Table 4.

Type of data collected through survey

| No | Variable | Question/statement | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Domestic apple preference | I prefer to purchase domestic apples (Malang apples) | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

| 2 | Social-economic status: | ||

|

What is your income? | Less than IDR 5 million, IDR 5–10 million, and more than IDR 10 million | |

|

What is your education level? | Senior high school or lower, vocational education, undergraduate, master’s degree, and doctoral degree | |

|

What is your gender? | Male and female | |

|

What is your age? | Less than 25 y.o., 25–55 y.o., over 55 y.o. | |

|

What is your religion? | Muslim, non-Muslim, I do not want to mention | |

| 3 | Local farmer empowerment | If I consume domestic apples, I contribute to local farmer empowerment | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

| 4 | National economy improvement | If I consume domestic apples, I contribute to improving the national economy’s performance | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

| 5 | Environmental problem | If I consume domestic apples, I contribute to reducing fuel consumption, pollution, and carbon emission in the logistics sector because the distance between the apple plantations and the consumer points is not far away | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

| 6 | FLW | If I consume domestic apples, I contribute to reducing FLW because the distance between the apple plantations and the consumer points is close enough so that the apples do not decay and become waste during shipment and storage | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

| 7 | Healthy food | If I consume domestic apples, I am healthier because the distance between the apple plantations and the consumer points is not far away, so the food nutrition is not lost. The apples are not treated with chemical substances during shipment and storage | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

| 8 | Risk of non-halal contamination | Apples may be treated with chemical substances for preservatives, that the substances may be not halal or not certified for halal | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

| 9 | Mandatory halal certification | If apples are treated with chemical substances that are not halal or not certified for halal, the apples or the substances should be certified for halal | SD, D, N, A, or SA* |

*Strongly disagree (SD) = 1, disagree (D) = 2, neutral (N) = 3, agree (A) = 4, and strongly agree (SA) = 5.

As the consumers’ preferences and behaviour concerning domestic apple products and FMs were the main topics of the questionnaires, the following inquiry concerns variables influencing consumers’ preferences for apple commodities with SFMs were asked after the respondent information questions. The inventory of queries used in this investigation is explained in greater detail in Table 4.

-

Informed consent: The study used data from an online questionnaire that respondents used on their smartphones when they filled out the questionnaire. All participants gave their consent to fill out the questionnaire. Data that they gave are reported in the aggregate.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

3.2 Statistical analysis

The Rstudio was utilised in this work to create the partial least square-structural equation model (PLS-SEM) to perform a path model of factors affecting SFM. As PLS-SEM is favoured for studying path diagrams containing latent variables and various indicators, and it may have benefits over linear regression models [73]. Moreover, SEM also helps incorporate measured and theorised causal paths into model assessment [74]. By developing agents for construct suited for empirical analysis and exploratory study of multilevel structural equation models, PLS path modelling can aid in the solution of measurement error concerns [73,74].

An evaluation of the reflective and structural measurement models was adopted to perform the PLS-SEM, as suggested by some scholars [75]. A mediation analysis was run to obtain an indirect effect of the Halal construct on the SFM construct using a procedure suggested by some scholars [76,77]. The guidelines outlined in Table 5 were used to evaluate models and test the hypotheses. Moreover, a bootstrap method was run to assess the significance of path coefficients [77,78,79]. A bootstrap approach was used in the analytical paths to validate the importance of the path by utilising the number 1,000 as a sub-sample [77,78,79].

Evaluation of the measurement models and the structural model

| Criteria | Accepted value |

|---|---|

| Evaluation of the reflective measurement model: | |

| Reflective indicator loadings | Reliable ≥ 0.708 |

| Internal consistency reliability | Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (rhoC and rhoA): between the minimum (0.70) and maximum (0.95) value |

| Convergent validity | Average variance extracted (AVE) ≥ 0.50 |

| Discriminant validity: | |

| For conceptually similar constructs | Heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio < 0.90 |

| For conceptually different constructs | HTMT ratio < 0.85 |

| Evaluation of structural model: | |

| Multicollinearity test | Variance inflation factor (VIF) < 3 |

| Explanatory power: | |

| Coefficient of determination (R square value) | Substantial (0.75), moderate (0.50), weak (0.25), acceptable (0.10) |

| Mediation analysis: | |

| Complementary mediation | There are mediated and direct effects that the points are in the exact directions. |

| Competitive mediation | There are mediated and direct effects that the points are in opposite directions |

| Indirect-only mediation | There is a mediated effect but no direct effect |

| Direct-only nonmediation | There is a direct effect but no indirect effect |

| No-effect nonmediation | In- and direct effects do not exist |

| Hypothesis testing: | |

| t statistics’ confidence interval | 95% |

4 Results

This section covers the output of PLS-SEM. Table 6 presents some outputs of reflective measurement comprising reflective indicator loadings, internal consistency, reliability (i.e. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability), and convergent validity. The indicator loadings of all variables are acceptable (>0.708). Thus, the variables are reliable. The AVE values are satisfied for all constructs above 0.50 regarding convergent validity. Therefore, all constructs are valid under a convergent validity perspective.

Output of validity and reliability evaluation

| Construct | Variable | Loading | Cronbach’s alpha | rhoC | rhoA | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic-economy interest (Econ) | Econ_1 | 0.922 | 0.844 | 0.927 | 0.851 | 0.865 |

| Econ_2 | 0.938 | |||||

| Halal reason (Halal) | Halal_1 | 0.717 | 0.468 | 0.784 | 0.513 | 0.647 |

| Halal_2 | 0.883 | |||||

| Health and environmental benefit (HEnv) | HEnv_1 | 0.911 | 0.861 | 0.914 | 0.879 | 0.781 |

| HEnv_2 | 0.872 | |||||

| HEnv_3 | 0.867 |

Regarding internal consistency reliability, the results are mixed. The first is the values of Cronbach’s alpha that some constructs (i.e., interest in the domestic economy and health-environmental benefits) are satisfied (above 0.7). The value of Cronbach’s alpha for the halal construct is not satisfied because it falls below the minimum value (0.7). The second is rhoA as the measurement of composite reliability that only some constructs (i.e., interest in the domestic economy and health-environmental benefits) are acceptable, with a value between 0.70 and 0.95. The rhoA value for the halal construct is not satisfied because it falls below the minimum value of 0.70. The third is rhoC, as the measurement of composite reliability that all constructs are acceptable and that the values fall between 0.70 and 0.95. In this case, all the constructs were considered, even if halal constructs should be given serious attention. A clear portrayal of internal consistency reliability is presented in Table 6.

The HTMT ratio was used for discriminant validity, as presented in Table 7. The original estimation shows all constructs are acceptable because the HTMT ratio is under 0.85. The original ratio is consistent with the bootstrapped ratio of HTMT. The bootstrapped mean of the HTMT ratio is also under 0.85. Thus, the constructs are valid under the perspective of discriminant validity.

Bootstrapped HTMT ratio

| Original Est. | Bootstrap mean | Bootstrap SD | T stat. | 5% CI | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Econ → Halal | 0.493 | 0.497 | 0.087 | 5.642 | 0.354 | 0.643 |

| Econ → HEnv | 0.711 | 0.714 | 0.037 | 19.136 | 0.649 | 0.772 |

| Econ → SFMs | 0.292 | 0.296 | 0.045 | 6.530 | 0.219 | 0.368 |

| Halal → HEnv | 0.553 | 0.557 | 0.076 | 7.273 | 0.430 | 0.678 |

| Halal → SFMs | 0.151 | 0.160 | 0.069 | 2.178 | 0.050 | 0.278 |

| HEnv → SFMs | 0.293 | 0.295 | 0.044 | 6.689 | 0.223 | 0.364 |

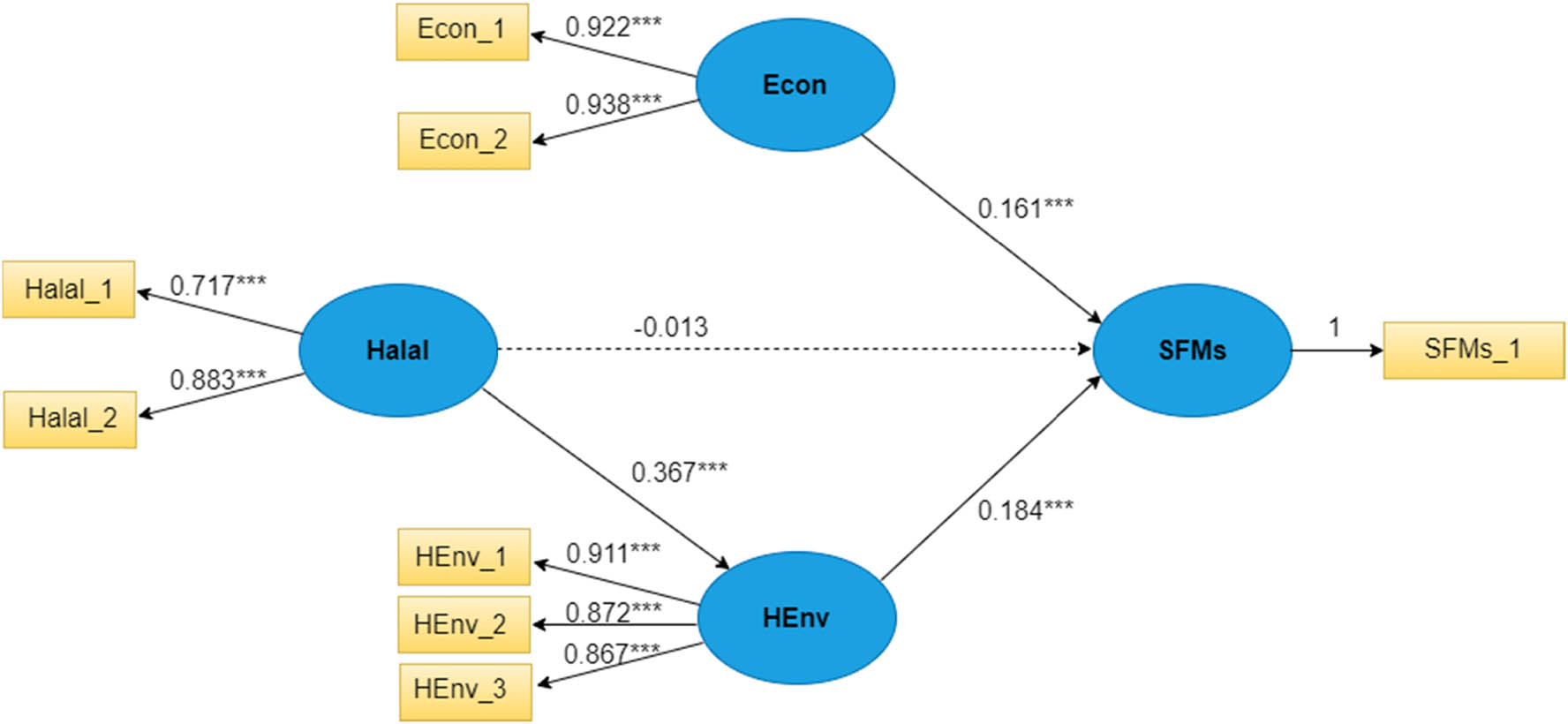

Besides evaluating reflective measurement, the structural model (comprising estimated coefficients of paths, multicollinearity test, and coefficient of determination) was evaluated. The first is estimated coefficients that all paths are significant under a 95% confidence level except for the path from halal to preference construct (Table 8). Thus, this study accepts hypothesis 1 (domestic-economy interest directly affects the preference for SFMs), hypothesis 3 (health-environmental benefits directly affect the preference for SFMs), and hypothesis 4 (halal requirements directly affect health-environmental benefits). However, this study rejects hypothesis 2 (halal requirements directly affect the preference for SFMs). The portrayal of the estimated coefficients of paths is presented in Figure 3.

Estimated coefficients of paths

| Original Est. | Bootstrap mean | Bootstrap SD | T stat. | 5% CI | 95% CI | Hypotheses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Econ → SFMs | 0.161*** | 0.165 | 0.050 | 3.190 | 0.062 | 0.265 | H1: Accepted |

| Halal → HEnv | 0.367*** | 0.370 | 0.047 | 7.753 | 0.272 | 0.458 | H4: Accepted |

| Halal → SFMs | −0.013 | −0.010 | 0.049 | −0.267 | −0.105 | 0.085 | H 2 : Rejected |

| HEnv → SFMs | 0.184*** | 0.183 | 0.052 | 3.576 | 0.080 | 0.287 | H3: Accepted |

***significant under α = 0.01, **significant under α = 0.05, and *significant under α = 0.10.

Estimated model of path. ***significant under α = 0.01, **significant under α = 0.05, and *significant under α = 0.10.

Regarding the indirect effect of the Halal construct on the SFM construct, the total and indirect effects are presented in Table 9. The total effect of Halal on SFMs (Path 1: Halal → HEnv, Path 2: HEnv → SFMs, and Path 3: Halal → SFMs) is 0.055. The total indirect effect of Halal on SFMs (Path 1 and Path 2) is 0.068 (t-statistics = 3.364; 95% CI (0.03, 0.107), meaning significant (non-zero confidence interval) under a 5% confidence level. Because the total indirect effect of Halal through HEnv on SFMs is significant (Path 1 and Path 2), but the direct effect of Halal on SFMs (Path 3) is not significant (as presented in Table 8), the type of mediation is indirect-only mediation (complete mediation). Thus, hypothesis 5 (halal requirements indirectly affect the preference for SFMs through HEnv benefits) is accepted.

Total and indirect effects

| Econ | Halal | HEnv | SFMs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | ||||

| Econ | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Halal | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.068 |

| HEnv | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SFMs | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Total effect | ||||

| Econ | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.161 |

| Halal | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.367 | 0.055 |

| HEnv | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.184 |

| SFMs | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

The last one is to examine whether the paths in Figure 3 have the problem of collinearity and explanatory power (i.e. the extent of coefficient determination). Table 10 presents the issues. The first is that VIF values are below 3; thus, it can be concluded that the collinearity issue does not exist. The second is coefficient determination. The R square for the SFM construct is 0.093 (not acceptable), meaning that three constructs (i.e. Halal, Econ, and HEnv construct) explain only 9.3% of the variance of the SFM construct. In addition, the R square for the HEnv construct is 0.134 (acceptable), meaning the Halal construct explains 13.4% of the variance of the SFM construct.

Multicollinearity issues and explanatory power

| SFMs | HEnv | |

|---|---|---|

| VIF for Econ | 1.613 | . |

| VIF for Halal | 1.172 | . |

| VIF for HEnv | 1.683 | . |

| R 2 | 0.093 | 0.134 |

| Adj R 2 | 0.088 | 0.133 |

5 Discussion

Finally, as found in this study, the significant and direct causes of preference for SFM of apple fruit (domestic apples) align with previous studies on the preference for domestic apple fruit among Indonesia consumers [80,81,82]. This research confirms the previous studies on the two reasons for the preference for SFM of apple fruit (measured with preference to purchase domestic apple fruit).

The first reason for the choice of SFM is the interest of the domestic economy. Economic interest can be the following regional multiplier effect of SFSC: first, job creation in farming, supply chain, and services, rural territories; second, generating landscape economy with access to nature; third, provision of activities (social, inclusive, labour, intensive industry), life, communication, identity, skills, incomes in remote areas, as argued by the previous study [40]. It means that Indonesians are concerned about the patriotism of the domestic economy. It also implies that economic patriotism in Indonesia is not only encouraged by the government through protectionism policies [83] but also by citizens through the consumption of domestically produced products/commodities [44]. The belief of interest in the domestic economy among Indonesians will benefit the economy in the future because economic patriotism in Indonesia is a widespread and increasing phenomenon [84,85]. The previous study of apple preference in Indonesia found that consumers prefer domestic apples because they support domestic apple farmers [82]. That is consistent with the findings from the present study.

Moreover, this study confirms the findings of previous studies on the promotion of SFM [57,86], even if the effectiveness of the FM program on food self-sufficiency and food security is still under big question [8]. The previous studies implicitly reported patriotism by providing local foods to local people in the UK, Germany, France, Sweden, Norway, and Fiji [34,36,57,86]. The previous study shows that the effective implementation of SFM for typical foods in Germany and France could not only supply foods for domestic people but also export foods to other countries [86] due to an excess of domestic supply. The Fijian case reduced LFM by producing more local foods and reducing dependence on imported foods [57]. The Fijian case shows patriotism among people from developing country to purchase and consume local foods for better local economy and environmental quality [57], which is strongly relevant to the present study.

However, the successful implementation of FMs may be only valid for certain foods, not for many other foods. Some countries will face food insecurity if they persist in promoting SFM for all food categories because they do not have the capabilities to supply all foods domestically. For example, a few global populations (between 11 and 28%) can meet their demand for foods within a radius of 100 km2, and a somewhat large proportion of the global population between 24 and 64% can meet their demand for foods within 1,000 km2 [9]. Some regions cannot grow typical foods because of geographic characteristics and climatic conditions [87]. The different productivity among regions also determines the ability to supply typical foods within regions. The Europeans exemplify that the failure of local livestock production was caused by the high production cost, leading to the high price of animal products [88].

In addition, losses can be faced by trading partners of the countries promoting SFMs. For example, some African countries (e.g. Malawi, South Africa, and Madagascar) face welfare losses due to FM promotion in the UK, Germany, and France [86]. The decline of imports from countries promoting FMs will cause more FLW in countries of origin, as food waste occurs before distribution [62,63]. It is because the market does not absorb oversupplied foods domestically, and nobody can consume them. As a result, the foods should be disposed of and become waste.

The second reason for the preference for SFM is environmental conservation and a healthy lifestyle. Indonesians are aware of the environmental issues contributed by the long food transport. As found by some scholars [89], CO2 emission in Indonesia, which is contributed by the energy sector and waste, will increase by 2050. As emphasised by another study, food waste due to LFMs contributes to emissions [90,91]. Preference for SFM among Indonesian consumers means Indonesians take the bottom-up initiative to reduce FLW. The bottom-up approach found in the present study differs from the top-down approach of waste reduction under a circular economy implemented by the Government of Turkey and the UK [62].

The findings in the present study confirm some previous studies about environmental consideration as the cause of preference for either LFM or SFM [8,26,28,40,43,57,58,61,63,64]. SFSC (including apple fruit) is expected to improve the following environmental qualities: first, quality and efficiency of the resource management that is favourable to biodiversity, carbon footprint, landscape, and soil fertility; second, closing the nutrient cycle and producing renewable energy; third, valorisation of non-arable, disadvantaged land; and fourth, fire prevention [40]. The present study’s findings also align with the previous study in Fiji that the action of SFM can reduce greenhouse gasses from transport (e.g. carbon dioxide, hydrocarbons, nitrogen oxide, and carbon monoxide) [57]. A study of local food in Indonesia found that LFP is to reduce emissions and raise “environmental awareness and social justice” [92].

The present study’s findings regarding the environmental reason for SFM preference do not align with previous studies, which found that SFM cannot reduce emissions; otherwise, LFM can produce fewer emissions depending on the adopted technologies, type of carried foods, and region [93]. In addition, this study also rejects the previous study, stating that SFM can produce a higher carbon footprint than LFM [26].

On the health side, some Indonesians are concerned about healthy foods and lifestyles. Even if some Indonesians have unhealthy consumption, as reported by UNICEF’s staff [94,95], this study found that LFP is one of Indonesia’s quests for healthy foods and lifestyle. The healthy food and lifestyle found in this study confirm some previous studies on the health reason as the cause of SFM preference [8,61,65,66,67]. SFM can minimise food loss [60,64,96,97] and increase food security [64,98,99,100]. In addition, local farming of foods shapes a sustainable food system. It can enhance access and sustainability of food supply as the pillar of food security to meet safe and nutritious food diet [99] as the prerequisites to prevent malnutrition [98].

The findings from this study argue that a halal diet contributes to a healthy lifestyle. It is true because halal requirements promote food safety [21,22] and less use of food additives minimising the negative effect of the additives [50]. In this situation, halal diets help fulfil healthy diets with safety and quality [21,22,98,99]. Previous studies in Indonesia found that Indonesians prefer buying domestic apples because of their freshness and safety [80,81,82]. It implies that domestic apples coming from SFSC are healthy food.

In addition, the present study found a new construct as the new cause of the SFM preference. This study found that halal requirements can only work indirectly, fully mediated by health-environmental factors. Fulfilment of a healthy diet can be done by consuming halal foods free from unsafe ingredients and additives, as argued by some halal scholars [21,22,101]. It is true because imported foods are possibly treated with a non-halal chemical substance for preservation [18,19,47], and using coatings with unknown halal status is suggested to reduce FLW during long shipment [63]. Using food additives affects the integrity of the halal food supply chain (HFSC) and halal certificate issuance [21,101] because the contaminated foods have negative impacts on human health and food safety [1,21,22,50].

Halal scholars indirectly promote adopting a halal diet as the antecedent of a healthy diet [21,22] and food security scholars [98,99] to achieve the goals of healthy diets. Even if Sun and his/her colleagues promote using coatings to reduce FLW, they also suggest a dietary change for consumers [63]. It means consumers can freely select a healthy diet for better health. In Muslim society, consumers should select a halal diet for better health. Moreover, halal diets indirectly affect the SFM through a healthy diet because domestically produced foods in Muslim countries are mostly assured of their halal status. Muslim majority of Indonesia and the Government of Indonesia require the production and distribution of halal foods within the nation [102].

The findings from the present study also imply that the halal factor determines the purchasing decision of foods transported for long distances among Indonesian consumers. For apple fruit, Indonesian consumers prefer pure apples free from contamination by non-halal chemical substances (non-halal food additives). The purity of the apples is related to the tayyib principle (wholesome) in halal foods certification and halal lifestyle [21]. Thus, using edible waxes for apples does not persuade Indonesian Muslim consumers to purchase foods traveling for long distances. The concern that should be given is to treat apples with edible halal chemical substances for significant gain from the big Muslim market.

6 Theoretical contribution

This research found a theoretical contribution to the literature on green supply chains (i.e. FMs), HFSC, food security, and self-sufficiency. This research suggests halal requirements are the new and indirect factor affecting the preference for SFMs. The construct of halal requirements is an effort to close the research gap from previous studies mentioned in the literature section [26,35,36,39,58,61,63,65]. Thus, the construct of halal requirements can equip other factors affecting SFM. Moreover, a study on FMs in Muslim countries suggests the different contexts of FM studies should be considered not only about the distance but also about the halal and tayyib (wholesome) issue as the concern of Muslim society [21,22,51,54,56].

In addition, this study contributes to the literature development on food security and self-insufficiency with special emphasis on SFSC and HFSC for healthy diet. The present study suggests the notion that successful SFSC can fulfil a healthy diet, including a halal diet, as the outcome of food security [10,21,98,99].

7 Conclusion

This study, focusing on Indonesia, investigates the indirect and direct factors influencing the desire for FMs of apple fruit (expressed by LFP of apples). This study made many vital discoveries: first, the demand for SFM is directly driven by interest in domestic economy and health-environmental benefits, confirmed by the acceptance of H1 and H3 results; second, a halal lifestyle is required for a healthy lifestyle, confirmed by the acceptance of H4; third, the non-significant H2 results show halal requirements do not directly influence food short-distance preferences; fourth, halal requirements were discovered to indirectly influence SFM preferences via health-environmental benefits (with complete mediation), which was shown by the significance of H5. Therefore, the new construct of halal requirements mostly prevails in Indonesia and other Muslim countries. From a consumer behaviour perspective, Indonesian consumers prefer pure apples free from contamination by non-halal chemical substances (food safety). Even if treated with edible coatings or waxes, it is important to use halal chemical substances (halal food additives) for health consumers and gain from the big Muslim market.

The present study contributes to developing the literature on supply chains (covering the green supply chain and HFSC) and the relationship between food security and self-sufficiency. This study gives an emphasis on some pillars of food security (e.g. food safety, sustainability, access, healthy diet, and preference), as studied by FAO [99]. In addition, this study has some scientific values added: first, this study can discover a new construct of halal as the factor affecting SFMs that the construct is never considered by some previous studies on halal and green supply chains; second, this study can associate halal and food security issues; third, this study successfully shows that SFSC will effectively work if it is supported by successful program self-sufficiency or local food development; fourth, this study successfully shows the willingness of bottom level to reduce LFM for better health, environment, and economy. The bottom-up approach is assumed to have more massive mobilisation and action than the top-down approach of the circular economy program, as studied by a previous study [62].

This study has practical implications for the government, food scientists, activists, and environmentalists. They should promote SFM to reap the benefits such as a better domestic economy, healthy lifestyle, and environmental conservation. For Muslim countries, promoting SFM aligns with religious requirements, contributing to a healthy lifestyle and environmental conservation. For food scientists and activists, the promotion of SFSC will benefit local people in terms of a healthy diet that should be accompanied by sufficient supply, better access, and sustainability of supply.

The findings and recommendations from this study apply to numerous countries since this study adds the repository of scientific studies on green HFSC and food security. It can apply to developed and developing countries, as previous studies on FMs were conducted in Western countries [86] and Eastern countries [57]. In addition, the findings from this study can be applied in Muslim majority and minority countries, considering the impact of LFM on FLW, healthy diet (including halal diet for Muslims), and environment. The large FLW production in Turkey (a Muslim country), as found in the previous study [62], can be reduced with the SFM program besides the current action on circular economy. Application of green and HFSC can improve and assure the integrity of halal food along the supply chain, as suggested by a previous study [23].

Even though this study generated many vital results, it has some limitations. First, the variables for the Halal and Econ construct are limited. Second, this study combines the health-environmental causes in one construct, which can be independent of various indicators. Third, this study has few constructs, so it cannot disclose other factors affecting SFM preference. Fourth, food security issues are not considered an independent construct; instead, it is partially and implicitly covered in the construct of health-environment.

Future research can consider the following areas of study. First, the factor of halal requirements and domestic economic interest with many indicators enhances the inadequate parameters of this study. Second, the future tasks are to investigate the direct effect of halal requirements on SFM as the halal requirements latent variable is the newly created construct. Third, future studies can consider the environmental factor construct independent of the health factor. Fourth, a study on the relationship among FMs, food security, and self-sufficiency is necessary because successful SFSC requires sufficient supplies from domestic production for a healthy diet. Fifth, a study on SFs in Indonesia should compare the positives and benefits of food sourcing in a specific region from neighbouring regions and other countries to capture more insight into the distance effect, as conducted in Fiji [57]. Sixth, in the context of Indonesia, some partial and in-depth studies on the positive and negative impacts of local food development on a territory, as suggested by some scholars [40], are necessary so that they can present a comprehensive view of the negative and positive impacts of SFSC in Indonesia.

Nomenclature

- AVE

-

average variance extracted

- FLW

-

food loss and waste

- FM(s)

-

food mile(s)

- HFSC

-

halal food supply chain

- HTMT

-

heterotrait-monotrait

- PLS-SEM

-

partial least square-structural equation model

- LFM(s)

-

long(er) food mile(s)

- LFP

-

local food preference

- SFSC

-

short(er) food supply chain

- SFM(s)

-

short(er) food mile(s)

- SCF

-

short chained foods

- VIF

-

variance inflation factor

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences – Godollo, Hungary, and Stipendium Hungaricum (Tempus Public Foundation) for their support. They also thank to all Indonesian colleagues for their help during data collection and analysis.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualisation, L.O.N., M.F.-F., and B.GY.; methodology, L.O.N., and W.S.N.; software, W.S.N. and L.O.N.; validation, H.M.N., E.L., M.F.-F., and B.GY.; formal analysis, L.O.N. and H.M.N.; investigation, L.O.N.; resources, L.O.N.; data curation, L.O.N., W.S.N., and H.M.N.; writing – original draft preparation, L.O.N.; writing – review and editing, L.O.N., W.S.N., H.M.N., E.L., M.F.-F., and B.G.Y.; visualisation, L.O.N., and W.S.N.; supervision, E.L., M.F.-F., and B.G.Y.; project administration, E.L., M.F.-F., and B.G.Y.; funding acquisition, E.L., M.F.-F., and B.G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data used for academic purposes should involve the main author.

References

[1] Paxton A. The Food Miles Report: The dangers of long-distance food transport. London, UK: SAFE and Sustain Alliance; 2011 (accessed on 5 January 2023). https://www.sustainweb.org/publications/the_food_miles_report/.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kemp K, Insch A, Holdsworth DK, Knight JG. Food miles: Do UK consumers actually care. Food Policy. 2010;35:504–13. 10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.05.011.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Blanke MM, Burdick B. Food (miles) for thought: energy balance for locally-grown versus imported apple fruit. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2005;12(3):125–7. 10.1065/espr2005.05.252.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Lee JY, Han DB, Nayga Jr RM, Yoon JM. Assessing Korean consumers’ valuation for domestic, Chinese, and US rice: Importance of country of origin and food miles information. China Agric Econ Rev. 2014;6(1):125–38. 10.1108/CAER-07-2012-0071.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Grebitus C, Lusk JL, Nayga Jr RM. Effect of distance of transportation on willingness to pay for food. Ecol Econ. 2013;88:67–75. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.01.006.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Caputo V, Nayga Jr RM, Scarpa R. Food miles or carbon emissions? Exploring labelling preference for food transport footprint with a stated choice study. Aus J Agric Resour Econ. 2013;57:465–82. 10.1111/1467-8489.12014.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Caputo V, Vassilopoulos A, Nayga Jr RMN, Canavari M. Welfare effects of food miles labels. J Consum Aff. 2013;47(2):311–27. 10.1111/joca.12009.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Stein AJ, Santini F. The sustainability of “local” food: a review for policy-makers. Rev Agric Food Environ Stud. 2022;103:77–89. 10.1007/s41130-021-00148-w.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kinnunen P, Guillaume JHA, Taka M, D’Odorico P, Siebert S, Puma MJ, et al. Local food crop production can fulfil demand for less than one-third of the population. Nat Food. 2020 Apr;1:229–37.10.1038/s43016-020-0060-7Search in Google Scholar

[10] Thomson A, Metz M. Implications of Economic Policy for Food Security: A Training Manual. Rome, Italy: Agricultural Policy Support Service Policy Assistance Division, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); 1998. (Training Materials for Agricultural Planning). Report No.: 40. https://www.fao.org/3/X3936E/X3936E00.htm.Search in Google Scholar

[11] FAO. Fruits ans Vegetable: Your Dietary Essentials. Rome: FAO; 2020. (Background paper). 10.4060/cb2395en.Search in Google Scholar

[12] CIRAD FAO. Fruit and vegetables: Opportunities and challenges for small-scale sustainable farming. Rome: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) & Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD); 2021. 10.4060/cb4173en.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Omoleye O Assessment of food losses and waste and related greenhouse gas emissions along a fresh apples value chain [Master Thesis]. [Uppsala]: Department of Energy and Technology - Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; 2020. https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/40027/1/Published-omeleye_o_201006.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Coley D, Howard M, Winter M. Food miles: time for a re-think? Br Food J. 2011;113(7):919–34. 10.1108/00070701111148432.Search in Google Scholar

[15] ITC Trade Map. Trade statistics for international business development. Trade Map: Trade statistics for international business development. 2023. https://www.trademap.org.Search in Google Scholar

[16] DinarStandard. State of the Global Islamic Economy: 2020/2021 Report. New York, NY, USA: DinarStandard, Dubai the Capital of Islamic Economy, and Salaam Gateway; 2020 (accessed on 21 December 2022). https://www.salaamgateway.com/specialcoverage/SGIE20-21.Search in Google Scholar

[17] DinarStandard. State of the Global Islamic Economy: 2022 Report. New York, NY, USA: DinarStandard, Dubai Economy and Toursim, and Salaam Gateway; 2022. https://www.salaamgateway.com/specialcoverage/SGIE22(accessed on 21 December 2022).Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jan N, Gani G, Sidiq H, Wani SM, Hussain SZ. Recent developments in harvest and postharvest management. In: Apples: preharvest and postharvest technology. USA: CRC Press: Taylor and Francis Group; 2023. p. 193–204. 10.1201/9781003239925-14.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Jin P. Latest advances in preservation technology for fresh fruit and vegetables. Foods. 2022;11(20):3236. 10.3390/foods11203236.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Pullman M, Wu Z. Food supply chain management: economic, social, and environmental perspectives. 1st edn. New York: Routledge Taylor-Francis; 2012.10.4324/9780203806043Search in Google Scholar

[21] Alzeer J, Rieder U, Hadeed KA. Rational and practical aspects of Halal and Tayyib in the context of food safety. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;71:264–7. 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.10.020.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Demirci MN, Soon JM, Wallace CA. Positioning food safety in Halal assurance. Food Control. 2016 Dec;70:257–70. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.05.059.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Soon JM, Chandia M, Regenstein JM. Halal integrity in the food supply chain. Br Food J. 2017;119(1):39–51. 10.1108/BFJ-04-2016-0150.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Tieman M, Vorst JGAJ, van derGhazali, MC. Principles in halal supply chain management. J Islamic Mark. 2012;3(3):217–43. 10.1108/17590831211259727.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Li M, Jia N, Lenzen M, Malik A, Wei L, Jin Y, et al. Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions. Nat Food. 2022;3:445–53. 10.1038/s43016-022-00531-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Malak-Rawlikowska A, Majewski E, Wąs A, Borgen SO, Csillag P, Donati M, et al. Measuring the economic, environmental, and social sustainability of short food supply chains. Sustainability. 2019;11(15):4004. 10.3390/su11154004.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Malandrin V, Dvortsin L Eating from the Farm: the social, environmental, and economic benefits of local food systems. Friends of the Earth Europe & Urgenci; 2016 May. https://www.foeeurope.org/sites/default/files/agriculture/2015/eating_from_the_farm.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[28] NRDC. Food miles: How far your food travels has serious consequences for your health and the climate. Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC); 2007 Nov. https://goodfoodworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/foodmiles.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Rothwell A, Ridoutt B, Page G, Bellotti W. Environmental performance of local food: Trade-offs and implications for climate resilience in a developed city. J Clean Prod. 2016;114:420–30. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.096.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Schnell SM. Food miles, local eating, and community supported agriculture: putting local food in its place. Agric Hum Values. 2013;30:615–28. 10.1007/s10460-013-9436-8.Search in Google Scholar

[31] ePowerTrucks. What does first, middle, & last mile delivery mean?. ePowerTrucks. 2021. https://www.epowertrucks.co.uk/news/what-does-first-middle-last-mile-delivery-mean/.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Fan X, Gómez MI, Coles PS. Willingness to pay, quality perception, and local foods: the case of broccoli. Agric Resour Econ Rev. 2019 Dec;48(3):414–32. 10.1017/age.2019.21.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Feldmann C, Hamm U. Consumers’ perceptions and preferences for local food: A review. Food Qual Prefer. 2015;40:152–64. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.09.014.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Nicolosi A, Laganà VR, Laven D, Marcianò C, Skoglund W. Consumer habits of local food: perspectives from Northern Sweden. Sustainability. 2019;11:1–25. 10.3390/su11236715.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Roininen K, Arvola A, Lahteenmaki L. Exploring consumers’ perceptions of local food with two different qualitative techniques: Laddering and word association. Food Qual Prefer. 2006;17:20–30. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.04.012.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Skallerud K, Wien AH. Preference for local food as a matter of helping behaviour: Insights from Norway. J Rural Stud. 2019;67:79–88. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.02.020.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Zepeda L, Li J. Who buys local food? J Food Distrib Res. 2006;37(856-2016-56238):1–11. 10.22004/ag.econ.7064.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Zhang T, Grunert KG, Zhou Y. A values–beliefs–attitude model of local food consumption: An empirical study in China and Denmark. Food Qual Prefer. 2020;83:1–11. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103916.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Wang M, Kumar V, Ruan X, Saad M, Garza-Reyes JA, Kumar A. Sustainability concerns on consumers’ attitude towards short food supply chains: an empirical investigation. Oper Manag Res volume. 2022;15:76–92. 10.1007/s12063-021-00188-x.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Perrot C, Ferguson HJ, Mulholland M, Brown A, Buckley C, Humphrey J, et al. Rendered services and dysservices of dairy farming to the territories: A bottom-up approach in European Atlantic Area. J Human Earth Future. 2022 Sep;3(3):396–402. 10. 28991/HEF-2022-03-03-010.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Puma MJ, Bose S, Chon SY, Cook BI. Assessing the evolving fragility of the global food system. Environ Res Lett. 2015;10(2):1–14.10.1088/1748-9326/10/2/024007Search in Google Scholar

[42] Grinberga-Zalite G, Pilvere I, Muska A, Kruzmetra Z. Resilience of Meat Supply Chains during and after COVID-19 Crisis. Emerg Sci J. 2021 Feb;5(1):57–66. 10.28991/esj-2021-01257.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Martinez S, Hand M, Pra MD, Pollack S, Ralston K, Smith T, et al. Local food systems: concepts, impacts, issues. 2010 May. Washington DC, USA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/46393/7054_err97_1_.pdf. Report No.: 97.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Bhagaskoro P, Pasopati RU, Syarifuddin M. Consumption and nationalism of indonesia: between culture and economy. In: Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2017. p. 211–3. 10.2991/icsps-17.2018.45.Search in Google Scholar

[45] FAO, Neven D. Developing sustainable food value chains – Guiding principles. Rome: FAO; 2014. https://www.fao.org/3/i3953e/i3953e.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Tieman M. The application of Halal in supply chain management: in‐depth interviews. J Islamic Mark. 2011;2(2):186–95. 10.1108/17590831111139893.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Alleyne V, Hagenmaier RD. Candelilla-shellac: An alternative formulation for coating apples. Hortscience. 2000;35(4):691–3. 10.21273/HORTSCI.35.4.691.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Sirajuddin MDBM, Mahaiyadin ohd H. Tayyib Perspect Qur’anic Thematic Analysis: Proposing Divine Insights Best Practice for Global Halal Industry. GJAT. 2022 Jun;UiTM ICIS JUNE 2022(Special Issue);108–18. 10.7187/GJATSI062022-11.Search in Google Scholar

[49] FAO, WHO. Assuring Food Safety and Quality: Guidelines for Strengthening National Food Control Systems. FAO and WHO. 2003(FAO Food and Nutrition Paper). Report No.: 76, https://www.fao.org/3/y8705e/y8705e.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Nazaruddin LO, Gyenge B, Fekete-Farkas M, Lakner Z. The future direction of halal food additive and ingredient research in economics and business: a bibliometric analysis. Sustainability. 2023;15(7):5680. 10.3390/su15075680.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Al‐Teinaz YR. What is Halal Food. In: The Halal Food Handbook. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2020. p. 9–26.10.1002/9781118823026.ch1Search in Google Scholar

[52] QDC Community. Quran (Muslims’ Holy Book). Quran.com. https://quran.com/search ? page = 1&q = naj&translations = 131 (accessed on 2 January 2023).Search in Google Scholar

[53] Zulfakar MH, Chan C, Jie F. Institutional forces on Australian halal meat supply chain (AHMSC) operations. J Islamic Mark. 2018;9(1):80–98. 10.1108/JIMA-01-2016-0005.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Bashir AM. Effect of halal awareness, halal logo and attitude on foreign consumers’ purchase intention. Br Food J. 2019;121(9):1998–2015. 10.1108/BFJ-01-2019-001.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Font-i-Furnols M, Guerrero L. Consumer preference, behavior and perception about meat and meat products: An overview. Meat Sci. 2014 Nov;98(3):361–71. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.06.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Jaiyeoba HB, Abdullah MA, Dzuljastri AR. Halal certification mark, brand quality, and awareness: Do they influence buying decisions of Nigerian consumers. J Islamic Mark. 2020;11(6):1657–70. 10.1108/JIMA-07-2019-0155.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Pratt S. Minimising food miles: issues and outcomes in an ecotourism venture in Fiji. J Sustain Tour. 2013;21(8):1148–65.10.1080/09669582.2013.776060Search in Google Scholar

[58] Passel SV. Food miles to assess sustainability: a revision. Sustain Dev. 2013;21:1–17. 10.1002/sd.485.Search in Google Scholar

[59] FAO. Toolkit - Reducing the Food Wastage Footprint. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2013. https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/341ec759-3d25-5e8d-b864-f9763a22f450/.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Glopan. https://www.glopan.org/foodwaste/.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Ishangulyyev R, Kim S, Lee SH. Understanding food loss and waste—why are we losing and wasting Food. Foods. 2019;8(8):297. 10.3390/foods8080297.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Grinberga-Zalite G, Zvirbule A. Analysis of waste minimization challenges to european food production enterprises. Emerg Sci J. 2022;6(3):530–43. 10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-03-08.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Sun H, Sun Y, Jin M, Ripp SA, Sayler GS, Zhuang J. Domestic plant food loss and waste in the United States: Environmental footprints and mitigation strategies. Waste Manag. 2022;150:202–7. 10.1016/j.wasman.2022.07.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] HLPE. Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food system. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2014. https://www.fao.org/3/i3901e/i3901e.pdf. Report No.: HLPE Report 8.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Lee HJ, Yun ZS. Consumers’ perceptions of organic food attributes and cognitive and affective attitudes as determinants of their purchase intentions toward organic food. Food Qual Prefer. 2015 Jan;39:259–67. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.06.002.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Wang J, Pham TL, Dang VT. Environmental consciousness and organic food purchase intention: a moderated mediation model of perceived food quality and price sensitivity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):850. 10.3390/ijerph17030850.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[67] Houcke J, van, Altintzoglou T, Altintzoglou T, Luten J. Quality perception, purchase intention, and the impact of information on the evaluation of refined Pacific cupped oysters (Crassostrea gigas) by Dutch consumers. J Sci Food Agric. 2018 Sep;98(12):4778–85. 10.1002/jsfa.9136.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] Ceschi S, Canavari M, Castellini A. Consumer’s preference and willingness to pay for apple attributes: A choice experiment in large retail outlets in Bologna (Italy). J Int Food Agribus Mark. 2018;30(4):305–22.10.1080/08974438.2017.1413614Search in Google Scholar

[69] Indonesia Statistical Agency. Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2023. Jakarta: Indonesia Statistical Agency; 2023.Search in Google Scholar

[70] ICR. Data of Indonesian population ny religion 2019-2021. DG for Indonesia Civil Registration (ICR), Ministry of Interior Affairs; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Jotform. Survey rating scales 1-5: Understand your audience better. Jotform Surveys. 2023. https://www.jotform.com/blog/survey-rating-scales/#:∼:text = Many%20people%20prefer%20the%201,how%20bad%20a%20problem%20is.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Trustmary. Introducing the Best Survey: 5 Point Scale. Trustmary Surveys. 2023. https://trustmary.com/surveys/introducing-best-5-point-scale-survey/.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Xie G, Huang L, Apostolidis C, Huang Z, Cai W, Li G. Assessing consumer preference for overpackaging solutions in e-commerce. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7951. 10.3390/ijerph18157951.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[74] Gefen D, Rigdon EE, Straub D. Editor’s Comments: An update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. MIS Q. 2011 Jun;35(2):iii–xiv. 10.2307/23044042.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). USA: Sage Publications; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q. Reconsidering baron and kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. 2010 Aug;37(2):197–206. 10.1086/651257.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using r: a workbook. Switzerland: Springer; 2021. 10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7. (Classroom Companion: Business).Search in Google Scholar

[78] Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Ray S, Danks N. SEMinR. Cran R Project: SEMinR. 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/seminr/vignettes/SEMinR.html#reporting-data-descriptive-statistics-and-construct-descriptive-statistics.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Isaskar R, Perwitasari H. Consumer preference for local apples malang and imported apples during the pandemic. In: IConARD Proceedings. EDP Sciences; 2021. 10.1051/e3sconf/202131601009.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Relawati R, Masyhuri M, Waluyati LR, Mulyo JH. The important attributes of local and imported apple: a factor analysis application. Agro Ekon. 2017;28(1):1–18. 10.22146/jae.22658.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Slamet AS, Nakayasu A. Exploring Indonesian consumers’ preferences on purchasing local and imported fruits. Acta Hortic. 2017 Nov 25;1179:1–8. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2017.1179.1.Search in Google Scholar

[83] Patunru AA. Rising economic nationalism Indonesia. J Southeast Asian Econ. 2018;35(3):335–54. 10.2307/26545317.Search in Google Scholar

[84] Guild J. Why economic nationalism is on the rise in Southeast Asia. The Diplomat. 2022 Dec 20; https://thediplomat.com/2022/12/why-economic-nationalism-is-on-the-rise-in-southeast-asia/.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Warburton E. Indonesia: Why economic nationalism is so popular. The Interpreter - The Lowy Institute; 2015. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesia-why-economic-nationalism-so-popular.Search in Google Scholar

[86] Ballingall J, Winchester N. Food miles: Starving the poor? World Econ. 2010;33:1201–17. 10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01270.x.Search in Google Scholar

[87] Efendi D. Temperate zone fruits production in Indonesia. Acta Hortic. 2014 Dec 11;1059:177–84. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2014.1059.22.Search in Google Scholar

[88] Deppermann A, Havlík P, Valin H, Boere E, Herrero M, Vervoort J, et al. The market impacts of shortening feed supply chains in Europe. Food Secur. 2018;10:1401–10.10.1007/s12571-018-0868-2Search in Google Scholar

[89] Cahyono WE, Parikesit, Joy B, Setyawati W, Mahdi R. Projection of CO2 emissions in Indonesia. Mater Today: Proc. 2022;63(1):S438–44. 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.04.091.Search in Google Scholar

[90] Parfitt J, Barthel M, Macnaughton S. Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:3065–81. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0126.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[91] Vera I, Bowman M, Mechielsen F. No Time To Waste. Rijswijk, the Netherlands: Feedback EU; 2022 Sep. https://feedbackglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Feedback-EU-2022-No-Time-To-Waste-report.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[92] Nurhasan M, Panggabean R How eating a local diet can help Indonesians live healthier and more sustainable lives. The Conversation. 2023. https://theconversation.com/how-eating-a-local-diet-can-help-indonesians-live-healthier-and-more-sustainable-lives-194076.Search in Google Scholar

[93] Avetisyan M, Hertel T, Sampson G. Is local food more environmentally friendly? ghg emiss impacts consuming import versus domestically produced food. Environ Resour Econ. 2014;58:415–62. 10.1007/s10640-013-9706-3.Search in Google Scholar

[94] Watson K. In search of healthy habits: In search of healthy habits in Indonesia. UNICEF. 2019. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/stories/search-healthy-habits-indonesia.Search in Google Scholar

[95] Watson K. Eating habits in Indonesia: Eating healthy, feeling fresh. UNICEF. 2019. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/stories/eating-healthy-feeling-fresh.Search in Google Scholar

[96] FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2013. https://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[97] Gustavsson J, Cederberg C, Sonesson U, van Otterdijk R, Meybeck A. Global food losses and food waste. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2011. https://www.fao.org/3/i2697e/i2697e.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[98] HLPE. Nutrition and food systems. Rome: FAO; 2017. (accessed on 26 February 2023). https://www.fao.org/3/i7846e/i7846e.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[99] HLPE. Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030. Rome: FAO; 2020. (accessed on 26 February 2023). https://www.fao.org/3/ca9731en/ca9731en.pdf. Report No.: HLPE Report 15.Search in Google Scholar

[100] Kuiper M, Cui HD. Using food loss reduction to reach food security and environmental objectives – A search for promising leverage points. Food Policy. 2021;98:1–2. 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101915.Search in Google Scholar

[101] Al-Teinaz YR. Halal ingredients in food processing and food additives. In: The Halal Food Handbook. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2020. p. 149–68.10.1002/9781118823026.ch10Search in Google Scholar

[102] GoI. PP No. 39 Tahun 2021 tentang Penyelenggaraan Bidang Jaminan Produk Halal. Jakarta, Indonesia: Government of Indonesia (GoI); 2021.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative