Abstract

Wine tourism (WT) is an important area of special-interest tourism in Portugal, and represents an increasingly significant component of regional development. In a more conservative approach, WT has been described as visiting vineyards, wineries, and engaging in wine-related activities. However, this perspective has been broadened, taking advantage of all the potential of the specific destination’s terroir (nature/landscape, tangible and intangible cultural heritage, etc.). Wine routes make the connection between wine and tourism in a specific region and intend to boost wine tourism by promoting collaboration between different stakeholders. Different routes present distinct approaches to WT, within diverse regional contexts, and different ways of collaboration within the wine route. This study compares three wine routes at different stages of development, located in a rural periphery – in the central region of Portugal – Bairrada, Dão, and Beira Interior, considering both context data and information collected in 113 interviews conducted with diverse wine tourism agents from these routes. Besides a brief characterization of the three routes, the main results indicate supplier’s preference for terroir routes instead of wine routes and show the importance of gender, age, and education level for the collaborative work between stakeholders. These aspects and their contribution to the development of WT routes are discussed. Some questions that additional studies may help answering are also reflected.

1 Introduction

Wine tourism (WT) is an important area of special interest in tourism [1]. In rural contexts, WT is a kind of rural tourism motivated not only by the wine product but also by the curiosity about wine-growing territories, their traditions, architecture, landscapes, and people [2]. In Portugal, WT is still a recent phenomenon (with a few decades); however, following the international trend, it has been the focus of increasing attention and investments, representing an increasingly significant and valued component of regional development in the country [3,4].

A privileged tool to promote the sustainable development of WT and respective rural territories are wine routes, due to their focus on local products and culture [5].

According to the legal framework for the wine route creation in Portugal, as referred by Novais and Antunes [6], a Portuguese wine route consists of a set of places, organized in a network, duly signposted, within a region producing quality wines, which may trigger tourist interest, including places whose offer includes certified wines, centers of interested wine industry, museums, and tourist enterprises. Wine routes make the connection between wine and tourism in a specific region and have the function of dynamizing wine tourism by associating and promoting collaboration between different stakeholders [4]. These may be conceptualized more restrictively as rather “wine/product-centered routes,” i.e., mainly focused on wine (e.g., wine producers) or broadly as “territory routes,” also including accommodation units, restaurants, tourism entertainment enterprises, among others.

The development of broader WT-based routes, especially territorial routes (in detriment to product-centered routes), represents a paradigm shift within wine tourism, particularly in “old wine regions” initially typically focused on the wine product and its sale [7], thus contributing to the broadening of the definition of WT itself. These routes, if well managed, can contribute to the development of a more sustainable destination, with opportunities for co-creative experiences, engaging and differentiated, increasing the organizational capacity and innovation of the entire regional tourist offer, strengthening an effective link to the market, and providing visitors with opportunities for a more intense immersion in the place, in its landscapes, cultural heritage, and experiences [8,9], such as harvest experiences, wine tasting experiences, culinary, and wine workshops.

In this sense, wine routes, in addition to the experiences related to wine, also provide connections with the natural landscape, the beauty of the wineries, the richness of the region’s historical, architectural, and cultural heritage, and the quality of its gastronomy [4]. According to Cruz-Ruiz et al. [5], both the wineries and the diverse heritage attractions and specific services provided to visitors are essential elements for the existence of the wine routes. Route visitors are, indeed, found to actually explore territories with multiple natural and cultural facets, rather than only focusing on wineries and wine tasting [8]. However, different routes present different approaches to WT and different configurations of wine route constitution. Furthermore, each wine route develops its activity with distinct organizational structures, showing different stages of development and growth [4]. Therefore, it is important to understand how aspects such as context (regional, demographic, development, tourism attractions, etc.), the professional structure of wine routes as well as the focus on rather the wine product or a broader terroir perspective, may contribute to distinct development and functioning of wine routes. Similar to other international research works [10,11,12], the present study analyses the structure of wine routes and perception of collaboration between players. More specifically, it contributes to understand these issues by analyzing and comparing three wine routes in the central region of Portugal at different stages of development and with distinct wine route perspectives, as well as route contexts – Bairrada (officially created in 1999), Dão (officially created in 1995), and Beira Interior (created only in 2019). The creation of these routes resulted from a joint effort of various public and private entities, including regional wine commissions, regional tourism entities, city councils, and wine producers [13].

For this purpose, routes are compared based on regional statistics, as well as information collected from 113 wine route members, interviewed concerning their views on route functioning.

2 Literature review

2.1 Wine tourism

The world wine industry is often divided into “Old World” vs “New World” wine producing countries. The “Old World” is represented by European countries (e.g., France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Austria, Hungary, and Germany), with secular involvement in wine production and frequently committed to maintaining, or at least proudly presenting as part of their history, traditional methods of wine production, while in the “New World” (e.g., United States of America, Australia, South Africa, Argentina, New Zealand, and China), wine production is more recent, relying on modern methods [14]. This distinction between “old” and “New World” wine producing countries, does not necessarily mean that the “old world wine producers” still work with only traditional methods, although some of them still do and are proud of it, while for others it is, mainly, a selling argument. Besides this, the point is the distinct approach and evolution between the wineries in these two types of countries, with “old world wine producers” mostly focusing on their wine, while “new wine producers” seem more open to an “experience approach” on wine, including wine tourism as strategically important. So, this distinction tends to be reflected in WT conceptualization, with the “Old World” tending to focus more on wine production, its tasting and sales, and WT emerging as a complement or a vehicle to promote wine selling. In the “New World,” WT and wine production have often developed simultaneously and a comprehensive tourist experience is offered, considering, in addition to wine, all territorial attributes, such as the rural landscape, tourist activities, and a more holistic experience of the territory, its culture and nature.

In this sense, among the possible definitions, WT can be understood in a more “Old World” perspective, as a visit to vineyards, wineries, festivals, and shows related to wine, of which wine tasting and/or contact with the attributes of a wine region are the main motivating factors for consumers [15]. Although a broader definition of WT, in a more “New World” perspective, has also been accepted, conceptualized in an ecosystemic logic [16], as “terroir tourism” or the wider exploration of wine-growing territories [17,18]. Correspondingly, WT may be conceptualized as travel with the objective of visiting, getting to know, and living experiences in wineries and wine regions, as well as exploring the region’s culture and local lifestyle, encompassing both the consumption of services and place experiences, and from the region’s perspective, a destination marketing opportunity [19]. Thus, WT is based both on the offer of wine tasting experiences of locally or regionally produced wines, and on the experience of lifestyles, landscapes, and culture, sometimes based on networks and territorial branding [9,20]. In this context, WT includes activities, such as tasting and buying wines in vineyards, farms, or wine cellars, as well as participation in unique experiences, such as grape harvesting, treading, courses related to wine, and different associations with gastronomy [21]. It also refers to the experiences of “cultural landscapes,” within or thematizing the vineyard landscape, and permitting immersion within a particular local/regional culture [17,22]. Independent of the considered approach (more conservative, wine-focused or more holistic, and terroir-focused), WT is at the intersection of the wine production and tourism sectors [23], associated with rural tourism and, more specifically, agrotourism [22,24]; as it allows contact with farms, vineyards, wineries, and other elements that characterize rural areas; and it is related to slow food tourism, contrasting with the culture of fast food, urban, global, and standardized food consumption [25].

In the last decades, WT has attracted increasing attention [26], with a trend of worldwide development (e.g., new vineyards, more and diverse wine tourism experiences) [27,28], especially observable in the “New World” countries [7]. Regardless of the approach to WT, the activity has the potential to revitalize rural wine-growing territories [24] through, on the one hand, tourism itself and, on the other, the sales of wines and other local products [19,29] that frequently gain recognition through the territorial brand associated with the wine. In this sense, wine tourism may contribute to achieve territorial marketing goals, and thereby enhancing the image of all relevant local products, especially if undertaken in a regionally articulated and consistent manner. Wine routes may help develop such an integrated territorial development approach, as discussed next.

2.2 Importance of wine routes

In developing wine tourism, a central role is clearly the focus on the territory of wine production (e.g., landscape, cultural heritage) and on the value-adding context (e.g., services, utilities, etc.) [30]. From this point of view, an adequate way to organize wine tourism in a region is to organize itineraries or integrated routes that pass through wine producing areas and offer the visitor the possibility of getting to know the natural and cultural resources of the visited territory associated with vineyards and wine [31] or even those not directly associated with the theme, but relevant for understanding and fully enjoying the region’s specificities, as most travelers seek a more holistic exploration of a territory [18]. Such routes may be considered a particular form of fostering the selling of wine and other agricultural products, catering services, and diverse tourist products located in a wine region, where family farms, together with other organizations and entrepreneurs, offer their products and services, mainly from their own production and based on local, endogenous resources [32].

Taking into consideration the scarce human, financial, and technical resources, typical to many rural areas [33,34], wine routes are developed in many countries as a strategy of (1) developing networks and stimulating collaboration amongst actors on a regional scale to overcome constraints of small scale enterprises and lack of resources, and improve innovative capacity [35,36,37]; (2) enhancing satisfaction of wine tourists’ expectations through articulated, innovative, and differentiated offerings [30,38,39]; (3) promoting the wine region and its territorial brand [19,40,41]; and (4) sustainable development of the territory and its rural community [30,42].

In fact, first their potential of fostering interaction between wine business and WT [43] explains the growing success of wine routes throughout the world, particularly given the increasing interest of tourists in engaging in diverse food and wine experiences [26,35,44]. Second, territories and their wines may benefit from substantial promotion [45], since wine routes operate as a means of brand identity [46,47], improving therefore wine notoriety and the territory’s reputation. Third, the wine routes provide a form of rural development, they are able to create synergies which not only value the culinary delights of the rural areas but manage to integrate all relevant players and resources in the same route chain [35,42,48], contributing therefore to rural development.

From this perspective, several institutions together with local communities, empowered by the entrepreneurial spirit and energy of the wine makers [30], associated with other stakeholders in the area (e.g. services of lodging, entertainment, information, etc.), are all vital to the success of the wine route. Thus, in an important wine producing country such as Portugal, it is crucial to understand the motivations of diverse WT players to integrate a wine route [49], and to know the strengths and weaknesses of wine routes, so as to improve and further develop the country’s wine tourism potential [30].

2.2.1 Wine routes around the world

If in some areas, wine tourism is considered to be only emergent [50], while in others it has become increasingly popular, because every new visitor is attracted to the rural space and its unique resources, such as those related with food, wine, and its culture [6,44,51].

Nevertheless, if formal links between tourism and wine have considerably expanded in recent years, particularly through the creation of wine routes, they (the links) have, indeed, existed since the first half of the last century [52]. For instance, wine trails have been a part of the German tourism industry since the 1920s [53], specifically in the slopes of the Rhine Valley with spectacular views over the vineyards and the wine-growing villages, bearing a wonderful medieval architecture [50]. Other examples followed, as in France (Alsace, Burgundy, and Champagne), and later in California (Napa Valley wine train), South Africa (Stellenbosch wine routes) or Australia (Tamar Valley wine route), and Italy (Valpolicella wine route) [50].

The popularity of wine routes has increased considerably after the 1970s in Western Europe and during the last decade in the Eastern European countries (after the implosion of the Soviet Union), when winemakers and winery owners recognized the benefits of opening their wineries to visitors and of collaborating with other regional stakeholders interested in the development of their businesses or regions [54,55].

In the case of Europe (considered “Old World,” due to its century-old traditions), the wine routes are boosted by the European Federation Iter Vitis (composed of 21 European countries), a non-profit association, which results from the International Association Iter Vitis established in 2007 in Sicily (Italy), with the aim of promoting and preserving the tangible and intangible European heritage of wine and viticulture [56].

The improvement of operational coordination of the network of cities, regions, and wine routes through tools for cooperation and the exchange of knowledge and technologies and through dissemination of better management and marketing processes, are among the main objectives outlined by the federation [56].

2.2.2 Wine routes in Portugal

Portugal has a long tradition of wine production and offers a large amount and diversity of wines, as well as wine producing areas, with great potential for wine tourism, leading to the emergence of new wine tourism infrastructures (e.g., wineries, hotels, restaurants, shops, and tourist entertainment services) [3]. One of the tools that Portugal uses to leverage the development of wine tourism is the creation of wine routes [4,35]. The beginning of the wine route projects took place in 1993, when Portugal, together with eight European regions (Languedoc-Roussillon, Bourgogne, Corsica, and Poitou Charentes in France; Andalusia and Catalonia in Spain; and the regions of Sicily and Lombardy in Italy), participated in the Dyonísios Interregional Cooperation Program promoted by the European Union [4].

This process of developing wine routes represents a new phase of Portuguese winemaking, which tries to reach those who have some interest in wine and are fascinated by the country’s natural and cultural heritage [4]. According to information available on the website of the organization Wine Routes of Portugal (http://rotadosvinhosdeportugal.pt/), there are currently 13 wine routes in Portugal (Vinho Verde, Douro and Porto, Dão, Beira Interior, Bairrada, Tejo, Lisbon, Bucelas Carcavelos and Colares, Península de Setubal, Alentejo, Algarve, Region of the Azores and Region of Madeira). Promoted mainly by the Regional Wine Commissions (CVR) and the Tourism Regions, most of these routes became operational between 1996 and 1998, with the aim of stimulating the tourism potential of each wine producing region, as the element of territorial wine tourism supply par excellence, with diverse organizational and functional structures, showing different stages of development [4,57].

The type of route adherents is diverse and their number has increased significantly in recent years amongst members of wine bottler associations, winegrowers associations, cooperative wineries, individual wineries, wine-producing farms, rural accommodation enterprises, restaurants, specialty stores, museums, and other entities of wine interest [6].

Applicants for membership are duly inspected and certified for this purpose [57]. However, the lack of common regulation that establishes the principles, organization, and basic content of all routes, has led to a certain lack of a common approach on route constitution [57], with inclusion criteria being defined by each association. For example, in the case of Associação Rota da Bairrada (Bairrada Route Association), the general criteria are seven and relate to location, compliance with certain legal norms, opening hours, functioning as an information point, accepting institutional promotion, collaborating with a tourism observatory, and having environmentally responsible conduct [58]. Still to exemplify, in accordance with the internal regulations of the Bairrada Route Association [58], registration fees vary actually between 250 and 500 euros (single entrance fee), while the annual fee is defined between 250 and 1,200 euros, varying according to the type of members (e.g., municipalities pay higher annual fees).

Members, in addition to the recognized potential for promoting their services/products, have the following membership benefits [58]: regular information on the initiatives of the Bairrada Wine Museum, the Association of the Bairrada Route and the Bairrada Wine Commission; participating in free promotional initiatives by the Bairrada Route; discounts offered on the initiatives of the Bairrada Route Association and marketed by it; discount on products and articles sold by the Bairrada Route; privileged conditions in accessing facilities provided by the Bairrada Route; and promotion of new wine brands approved by the Bairrada Wine Commission.

Despite their relatively short existence, there are several authors [4,36,59,60] who present the wine routes and wine producers in Portugal as a dynamic and high-quality activity sector. In fact, in the last decade, important investments were made in modern wine production techniques and processes, as well as in the internationalization of wine circuits throughout the country [61]. This development has made the Portuguese wine sector one of the most dynamic nationally, with a recognized impact on regional economic growth [60,61]. However, despite Portuguese wines being famous since centuries and their increasing visibility and recognition worldwide, mostly due to the modernization of wine making and the many international awards Portuguese wines have received in recent years, the country is far from being acknowledged as a top wine tourism destination. It is in this context that the national tourism entity Turismo de Portugal recently presented an action plan to make Portugal a “must-see wine tourism destination” for international tourist markets also [62].

3 The case study and methodological procedures

This study is part of a broader project, entitled Twine: co-creating sustainable tourism and wine experiences in rural areas, which aims to study the market for and issues involved in co-creating integral tourist experiences in rural wine destinations, based on a study of three contrasting wine routes: Bairrada, Dão, and Beira Interior. The project involves, apart from the coordinating university of Aveiro, the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu and the University of Beira Interior, as well as experts on sustainable rural tourism, wine tourism and regional development and focuses on tourist experiences as co-created, shared and impacting on tourists, local residents, agents of supply, and other stakeholders from the tourism and wine sectors.

3.1 The case study

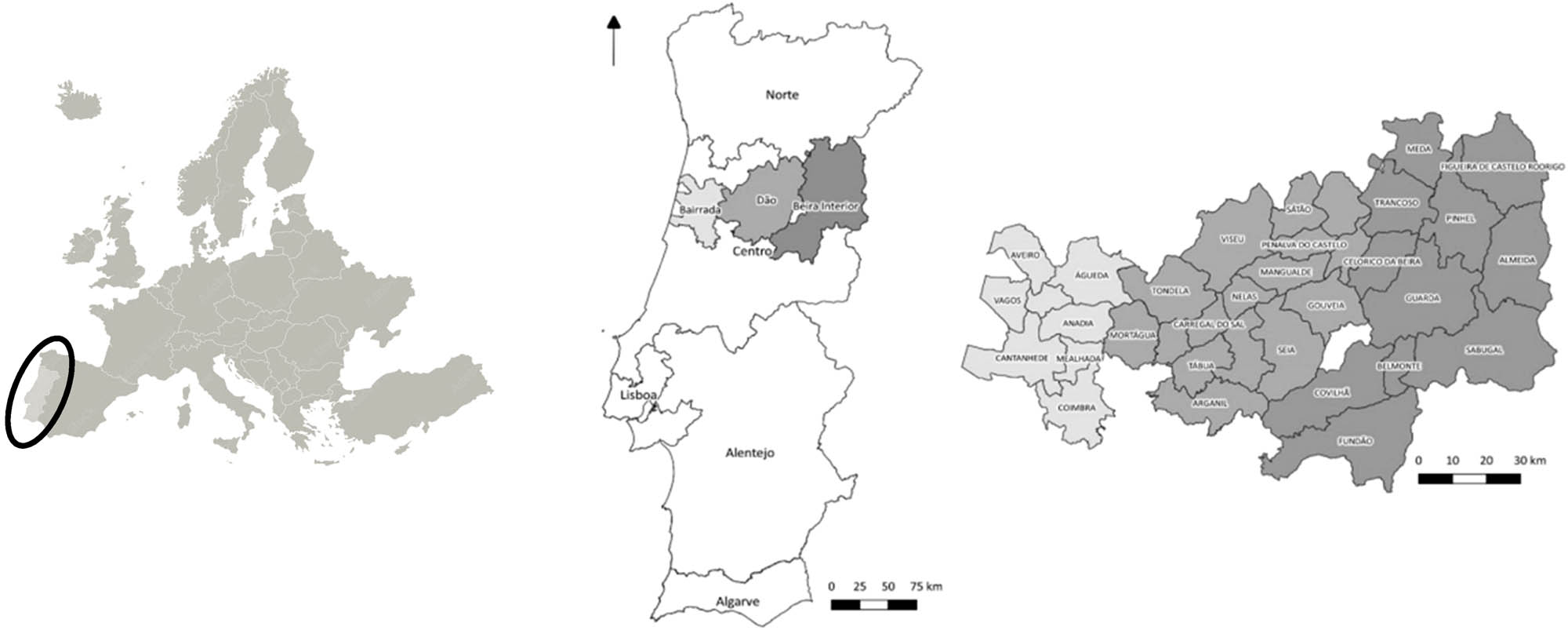

These routes present different degrees of development, with Bairrada being the most developed (with systematic wine tourism development integrating apart from wineries, municipalities, restaurants, hotels, and diverse tourism-related services, all integrating a network, supported since early stage by a professional technical structure), Dão the intermediate one (although older than Bairrada, with less dynamism in the early stages and mainly focused on wineries only), and Beira Interior, the less developed (also more recent route) (Figure 1).

The Bairrada, Dão, and Beira Litoral wine routes.

In fact, the three wine routes are distinguishable by their years of development, with the Bairrada Route presenting the first strategic networking and planning approach for a regional development based on wine and wine tourism since 1995, even before the official creation of the route in 1999. This networking integrated, since the beginning, the most important public regional stakeholders, namely, the four most important municipalities, the Bairrada wine commission, regional and national tourism entities, and the regional economic development agency. The route was launched in 1999 with all these entities and 28 wine producers, which have increased in the meantime to around a 100 of associates, from a broad range of sectors (wineries, museums, accommodation units, restaurants, thermal spas, and other attractions), revealing both the dynamism of the route and its terroir perspective yielding an integrated regional development.

The Dão region, although constituted officially in 1995, was launched only with the wine commission and 17 wineries, but lacked a broader terroir perspective, excluding businesses and agents that do not produce wine. It has also not gained as many adherents as the Bairrada region, being therefore here considered as relatively less developed and dynamic than the Bairrada Route, despite recent management and marketing improvements of the route. This wine route includes 16 municipalities and about 50 adherents, including vineyards, wineries, and wine producing cooperatives.

Last but not least, the Beira Interior Route is the most recent and less developed, encompassing 12 municipalities and more than 60 associated members amongst wineries, restaurants, and accommodation units. Although not all municipalities present wine production, they have something that justifies their inclusion in the route, such as monuments or hotels relevant for attracting and hosting wine tourists.

So, there is a combination of years of functioning together with dynamism of the route, number and variety of adherents as well as growth of the network, apart from a professional approach, based on qualified and dedicated staff.

3.2 Methodological procedures

The methodology used for data collection can be described in two phases:

a first phase of collecting statistical data on the routes’ websites and the national statistics website Pordata (https://www.pordata.pt/en/Portugal), in order to characterize the routes under study regarding their size and structure, visitation numbers, number of customers in the region’s accommodation units, amongst other factors.

A second phase of collecting qualitative data through in-depth interviews with wine tourism agents of the three routes, including not only actual wine route members, but also other wine tourism agents in the region (non-members being less than 5% of the sample). More specifically, the wine tourism agents interviewed for this study include wine producers, accommodation unit owners, restaurant managers, tour operators/agents, representatives from municipalities, and other associative or government entities. Independent of being accommodation providers, wine growers, or public entities, wine tourism creates a marketing and an important loyalty-generating and multiplier effect, which makes visitors interesting for the following reasons: cellar-door sales are more profitable (less transportation costs and commissions, and higher margins), creates loyalty (additional future demand), and strengthens brand image when visitors talk about their wine tourism experiences on social media (free advertising). The interviews lasted between 40 and 90 min each and were conducted online or via telephone (given the Covid pandemic). They contained several questions related to the objectives of the TWINE project, but in this study only data regarding the wine routes’ structure (entities that are part of the route), route conceptualization (wine vs terroir route), and functioning (collaboration amongst associates) are considered, more specifically the following questions: How do you evaluate the collaboration established with other tourism entities/stakeholders in the region? What are the benefits and difficulties? How do you evaluate the quality of the product, of the overall experience offered by the route? In your opinion, what actions can/should be developed to improve the route? What other companies/entities do you consider relevant to be part of the route and why? In total, 113 interviews were conducted, 44 in the Bairrada Route, 39 in the Dão Route, and 30 in the Beira Interior Route.

Data analysis was performed using NVivo 12. NVivo is a type of CAQDAS (acronym for computer assisted qualitative data analysis software), a tool for handling qualitative data that alleviates the workload in structuring and analyzing the information and improves the quality of the data analysis [63]. A content analysis was performed with data coded using both inductive and deductive approaches. Key concepts from the literature were used as initial codes, while new codes emerged during the codification process. Codes and sub-codes were frequently reviewed for consistency and recorded, when necessary, also discussing codes within the research team. The content analysis also followed an interpretive perspective, with overlapping content observable and the same comment possibly being coded into more than one category. NVivo provides the frequency of references of categories as well as “encoding matrix queries,” revealing relations between variables (e.g., frequency of categories by route). Additionally, SPSS 21 was used in order to complement results obtained with NVivo, namely, to calculate the statistical significance of differences between groups, performing chi-square tests.

4 Results

4.1 General characterization of the routes

The Dão Route covers the largest number of municipalities (n = 16) and the Bairrada Route the smallest number (n = 8). National statistics [64] regarding the number of residents per route for the municipalities that are part of the routes reveal that Bairrada has the highest number (n = 386,519), with relatively higher population density, as is typical of the Portuguese coastal areas, and Beira Interior the lowest number (n = 164,796) as well as lowest population density. It is also the Bairrada Route that has the highest number of rooms (n = 4,249) and Beira Interior has the lowest number (n = 1,616). International tourists are those who stay the longest, with the highest average overnight stays observable in the Dão route (M = 7.5). The Bairrada Route is the one that best represents the concept of a territory route with diverse associates, such as wine producers, restaurants, accommodation units, tour operators, among others. The Beira Interior Route, although in smaller numbers, probably due to its recent creation, also follows this terroir approach with very diverse types of associates. The Dão Route is the oldest and also the one that presents itself exclusively as a wine route (Table 1).

General characterization of the routes’ territory

| Bairrada | Dão | Beira interior | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipalities | 8 | 16 | 12 |

| Population | 386,519 | 257,742 | 164,796 |

| Average age | 42.97 | 45.56 | 46.13 |

| Tourist accommodation | 154 | 155 | 90 |

| Rooms | 4,249 | 2,413 | 1,616 |

| Overnight stays per 100 inhabitants (least and most) | 38.2 (Oliveira do Bairro) and 576.7 (Mealhada) | 24.4 (Sátão) and 795.3 (Mortágua) | 23.0 (Pinhel) and 447.2 (Mêda) |

| Average stay in tourist accommodation (higher average for international tourists in all regions) | Between 1.5 and 2.7 nights | Between 1.0 and 7.5 nights | Between 1.2 and 2.0 nights |

| Members | 93: 18 accommodation units + 38 wine producers + 27 restaurants + 3 suckling pig roasters + 4 tourism operators + 3 institutions (Comissão Vitivinícola da Bairrada; Turismo Centro de Portugal; museu do vinho) | 47: all wine producers, some with accommodation and others with a restaurant | 55: 36 wine producers, 5 beverage traders, 2 rural tourism, 1 beer producer, 1 restaurant, 1 combined agriculture and animal production, and 9 other activities |

Source: the route’s websites and national statistics.

4.2 The view of local agents/entities in the wine routes

4.2.1 Sample characterization

The three routes include more male associates, except for the Dão route, being more balanced in terms of gender. Members are mainly between 35 and 55 years old. However, there seems to be a tendency of members being younger in the Beira Interior Route and older in the Bairrada Route, with many missing values in the Dão route. In the three routes, the members mostly have a high level of education, that is, a graduation or higher. In both Bairrada and Dão, despite the first being a territory route and the second a wine-focused route, producers/winery/cellar door owners are the most frequent type of business owners present in this sample (Table 2).

Sample socio-demographics

| Bairrada (N = 44) | Dão (N = 39) | Beira interior (N = 30) | Total (N = 113) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 33 (75) | 20 (51.3) | 18 (60) | 71 (62.8) |

| Female | 11 (25) | 19 (48.7) | 12 (40) | 42 (37.2) |

| Age | ||||

| Missing values | 5 (11.4) | 20 (51.3) | 1 (3.3) | 26 (23) |

| <35 | 3 (6.8) | 6 (15.4) | 1 (3.3) | 10 (8.8) |

| 35–45 | 9 (20.5) | 6 (15.4) | 13 (43.3) | 28 (24.8) |

| 46–55 | 13 (29.5) | 3 (7.7) | 8 (26.7) | 24 (21.2) |

| 56–65 | 8 (18.2) | 2 (5.1) | 7 (23.3) | 17 (15) |

| >65 | 6 (13.6) | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 8 (7.1) |

| Education | ||||

| Missing values | 6 (13.6) | 7 (17.9) | 13 (43.3) | 26 (23) |

| At least a graduation | 35 (79.5) | 30 (76.9) | 12 (40) | 77 (68) |

| No graduation | 3 (6.8) | 2 (5.1) | 5 (16.7) | 10 (8.8) |

| Business | ||||

| Producer/winery/cellar door | 24 (54.5) | 23 (59) | 6 (20) | 53 (46.9) |

| Acommodation unit | 5 (11.4) | 4 (10.3) | 11 (36.7) | 20 (17.7) |

| Touristic operator | 4 (9.1) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (6.7) | 9 (8) |

| Restaurant | 5 (11.4) | 2 (5.1) | 10 (33.3) | 17 (15) |

| Municipality | 4 (9.1) | 3 (7.7) | 1 (3.3) | 8 (7.1) |

| Other entities | 2 (4.5) | 4 (10.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (5.3) |

Values in brackets show percentage values per column; most outstanding values are presented in bold.

4.2.2 Satisfaction, terroir, or product routes?

The wine tourism agents most satisfied with the operation of the route are those belonging to the Bairrada Route (27/44 = 61%), followed by Beira Interior (11/30 = 37%), with those from Dão being less satisfied (3/38 = 8%).

In fact, it is in the Bairrada Route that associates feel their involvement in the route is most rewarded, namely, in terms of sales and visibility promoted by the association.

“The biggest benefits (of integrating the route) are exactly that we are more sought after/have more customers” (Accommodation unit, Bairrada).

“The Bairrada Route helps a lot, especially in sales, but it also helps in some promotion” (Producer, Bairrada).

Although with a smaller expression, in the Dão Route, some producers also recognize similar results, regarding the promotion of quite profitable cellar-doors wine sales.

“We receive perhaps 30% of our visitors, more or less, who come here because they follow the Dão Wine Route” (Producer, Dão).

In general, the participants defend a territory route instead of a product route (“wine only”) approach. This narrative is especially evident in the Dão route, where this aspect appears in a critical tone when asked for suggestions to improve the development of the route itself (71.8%) (Table 3). This difference, according to chi-square test is statistically significative (χ 2 (2) = 9.23, p = 0.010; residuals = ±3). It was also verified that, among all the other variables analyzed in the SPSS (age, sex, education, type of business, etc.), only the type of business proved to be statistically significant regarding wine tourism agents’ preference for product vs terroir wine routes. In this sense, “other entities”, namely Comissão Vitivinícola da Bairrada (the wineries Commission), reveals a preference for product routes (χ 2 (5) = 23.10, p < 0.001; residuals = ±4.6). It should be noted that with regard to producers, from whom such a position could be expected, this did not happen.

Wine tourism agents’ preference for product vs terroir wine routes

| Bairrada (N = 44) | Dão (N = 39) | Beira interior (N = 30) | Total (N = 113) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||

| Product/wine | 3 (6.8) | 3 (7.7) | 1 (3.3) | 7 (6.2) |

| Terroir | 19 (43.2) | 28 (71.8) | 12 (40) | 59 (52.2) |

| Missing values | 22 (50) | 8 (20.5) | 17 (56.7) | 47 (41.6) |

Values in brackets show percentage values per column.

The Bairrada Route is the most developed and achieves greater satisfaction from the adherents regarding its structure and conceptualization.

“I think the Route of Bairrada is a very important entity that may boost wine tourism here in the region. Really some important things have been done in this sense” (Producer, Bairrada).

The Dão route is at an intermediate level of development, but a large part of the adherents are not satisfied and demand a route rather conceptualized as a terroir route instead of a “wine only” route.

“The route alone, in my view, does not work as a network. The route has its partners, its adherents, but then the process of getting people come to/stay in our farms, which is the ultimate goal of the route, I think, has still much to evolve” (Producer, Dão).

The Beira Interior Route, which is still at a very early stage, generates hope/positive expectations in those who know the project. There is, however, a part of the wine tourism agents who do not know the route.

“It’s so much still … at the beginning, (the route) is very incipient … we still do not have here much reflection of this wine route (in our operations), but it is a situation that I supported from the beginning and support without any kind of doubt. I think it is an excellent measure and it is a situation that will have to grow, when it has to be, as any other business, any other route … that is being well designed and that will be a success without a doubt” (Producer, Beira Interior).

Overall, the preference of a large majority of interviewees for a broader terroir route configuration is striking and reveals the strategic vision of most as to the benefits of regional collaboration in wine tourism for all involved.

4.2.3 Relationship between associates

In general, participants report the existence of partnerships and/or good relationships with associates and/or other entities (46.9%). Interestingly, it is in the most recent Beira Interior Route that there are more participants (70%) perceiving sound partnerships between wine tourism agents, followed by Bairrada (47.7%) and in contrast to Dão (28.2%) (χ 2 [2] = 11.91, p = 0.003; residuals = ±3). However, it is also in the Bairrada that a reasonable number considers partnerships weak or non-existent (27.2%), while it is particularly in the Dão route, where relatively more associates perceive partnerships to be weak due to the perception of rivalry (15.4%) (Table 4) (χ 2 [2] = 8.81, p = 0.012; residuals = ±2.9).

Relationship between associates

| Bairrada (N = 44) | Dão (N = 39) | Beira interior (N = 30) | Total (N = 113) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||

| There are partnerships and/or good relationships with associates and/or other entities | 21 (47.7) | 11 (28.2) | 21 (70) | 53 (46.9) |

| Partnerships are weak or non-existent (no explanation) | 12 (27.2) | 6 (15.4) | 4 (13.3) | 22 (19.5) |

| Partnerships are weak due to the perspective of potential partners as competitors or rivals | 1 (2.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (6.2) |

| Missing values | 10 (22.7%) | 16 (41.0) | 5 (16.7) | 31 (27.4) |

Values in brackets show percentage values per column.

The way associates view partnerships does not seem to differ much depending on the gender of the wine tourism agents (Table 5).

Relationship between associates considering gender

| Male (N = 71) | Female (N = 42) | Total (N = 113) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| There are partnerships and/or good relationships with associates and/or other entities | 35 (49.3) | 19 (45.2) | 54 (47.8) |

| Partnerships are weak or non-existent (no explanation) | 13 (18.3) | 9 (21.4) | 22 (19.5) |

| Partnerships are weak due to the perspective of potential partners as competitors or rivals | 3 (4.2) | 4 (9.5) | 7 (6.2) |

| Missing values | 20 (28.2) | 10 (23.8) | 30 (26.5) |

Values in brackets show percentage values per column.

As for education, there seems to be a relationship with the establishment of partnership relationships (Table 6). Amongst the less educated, the establishment of partnerships is more difficult (χ 2 [1] = 4.14, p = 0.042; residuals = ±2).

Relationship between associates considering education

| At least a graduation (N = 78) | No graduation (N = 10) | Total* (N = 88) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| There are partnerships and/or good relationships with associates and/or other entities | 35 (44.9) | 3 (30) | 38 (43.2) |

| Partnerships are weak or non-existent (no explanation) | 12 (15.4) | 5 (50) | 17 (19.3) |

| Partnerships are weak due to the perspective of potential partners as competitors or rivals | 6 (7.7) | 1 (10) | 7 (8.0) |

| Missing values | 25 (32.1) | 1 (10) | 26 (29.5) |

*25 missing values; values in brackets show percentage values per column.

With regard to age, partnerships seem to be less encouraged by older participants. Participants aged between 35 and 55 years seem to be the most proactive at this level (Table 7). Despite this trend in the descriptive data, differences are not statistically significant.

Relationship between associates considering age

| <35 (N = 10) | 35–45 (N = 28) | 46–55 (N = 25) | 56–65 (N = 17) | >65 (N = 8) | Total* (N = 88) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||||

| There are partnerships and/or good relationships with associates and/or other entities | 4 (40) | 16 (57.1) | 15 (60) | 6 (35.3) | 1 (12.5) | 42 (47.7) |

| Partnerships are weak or non-existent (no explanation) | 2 (20) | 5 (17.9) | 5 (20) | 5 (29.4) | 3 (37.5) | 20 (22.7) |

| Partnerships are weak due to the perspective of potential partners as competitors or rivals | 2 (20) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 6 (6.8) |

| Missing values | 2 (20) | 5 (17.9) | 4 (16) | 6 (35.3) | 3 (37.5) | 20 (22.7) |

*25 missing values; values in brackets show percentage values per column.

5 Discussion and conclusion

The present study shows that several factors influence the performance of the wine routes in Portugal, specifically the wine routes of the central region of the country. The degree of development of the routes and their conceptualization as a terroir vs a product route seem to contribute significantly to the degree of satisfaction of its adherents. In addition, among those who consider themselves satisfied with the integration in the route, the reasons given are above all the increase in visibility and customers brought by this network. In the Bairrada Route, the most developed among the three, adherents seem to be most satisfied, not only with regard to the work carried out by the route, but also with its structure and its terroir approach. Wine tourism agents seem to recognize that there is a marketing and important loyalty-generating and multiplier effect, which interests the visitors for several reasons: cellar-door sales are more profitable, create loyalty (thereby additional future demand), and strengthen brand image when visitors talk about their experiences on social media. The Dão route (at an intermediate level of development) presents higher levels of dissatisfaction amongst regional wine tourism agents, apparently as they would prefer a terroir route instead of a too narrow focus on wine, with also some rivalry amongst route members possibly undermining the potential of the network. Wine tourism agents from the Beira Interior Route, which is still at a very early stage, show hope/positive expectations regarding the route project. There are, however, some wine tourism agents who do not even know the route. In any case, here agents also seem to prefer terroir-focused approaches, that integrate a variety of regional features in the route visitor experience apart from those directly related to wine.

However, other contextual data are also relevant for a better understanding of the success of the routes. According to the data collected in this study, the best developed/established routes are located in municipalities with higher population density, lower average ages of residents, with greater capacity to accommodate visitors (number of rooms), and higher average number of overnight stays. With regards to sociodemographic aspects, namely, gender of wine tourism agents, we realize that although wine production and wine tourism are increasing activities, where women play an important role (including administrative positions), this study reveals a rather male wine tourism supplier universe. Interestingly and in a way even paradoxically, the route most focused on the wine product (Rota do Dão) is the one that presents the most balanced subsample in terms of gender. Still, gender does not seem to be relevant for how wine tourism agents position themselves in relation to collaboration with other associates. In fact, this aspect seems to be more conditioned by the institutional culture of the route and its degree of development that may foster (albeit unintentionally) rivalry between partners. For example, belonging to a well-established route, such as Bairrada, could reduce the effort placed on relationship-building, insofar as they may expect that these bridges will be made by the route itself. On the other hand, in more recent routes, such as Beira Interior, the recency and lack of knowledge about the route and its potential can lead to a more proactive attitude of wine tourism agents to create their own collaboration networks. Conversely, routes too focused on the product, such as the Dão route, could increase the fear that there is not enough demand for such a large and specific offer, fostering possible rivalries and non-collaborative attitudes among associates that all seem to fight for the same, quite specific market. The Beira Interior Route presents itself as the one where it seems to be easier to establish partnerships. This aspect may be due to the fact that Beira Interior is located in the sparsely populated rural hinterland, at the rural periphery, with several socio-economic fragilities, making collaboration a relevant strategy for overcoming obstacles [65]. Here people are known to culturally present a more mutual-help attitude, while additionally until recently there was no route that somehow facilitated networking, which may reinforce wine tourism agents to do this work autonomously.

Regarding age of agents interviewed, despite Beira Interior being the territory with the oldest population, it is this route that has the youngest wine tourism agents. This fact is probably a reflection of the development of the routes themselves. Younger wine tourism agents are those that may more easily adhere to an innovative approach within the wine sector, such as wine tourism experiences. They may also be more receptive to establishing partnerships with other associates, thus explaining the fact that in Beira Interior, respondents perceived partnerships as easier to establish.

Finally, in terms of education, most wine tourism agents have a high level of education in the three routes, with higher education apparently facilitating engagement in partnerships with other wine tourism agents, essential in a territory approach.

In fact, the case shows different types of approaches to wine routes, some too focused on wine, others more inclusive of other attractions. However, as several academic studies have shown to be vital [8], more than only a wine focus, a terroir-experience focus is needed, with wine routes constituted as “wine tourism ecosystems” including other actors with diverse attractions and services which require a type of collaboration between route members that extends beyond limits of specific sectors [66].

In fact, this study makes it possible to raise this and other questions, specifically regarding the factors that influence a more collaborative attitude amongst associates, an issue that would deserve more attention in the future, preferably through mixed approaches. As much as recent wine route development may engage particularly young, dynamic, well-educated, and enthusiastic local players striving for success through innovative, articulated efforts in a region that lacks a lot of other socio-economic resources making agents understand the urge of cooperation (such as in Beira Interior), more developed routes (such as the Bairrada Route), although showing some success and good level of partnerships, also seems to struggle with some less enthusiastic route members, revealing the challenge of not only creating an articulated, functioning network but also keeping it alive, dynamic, and continuously attracting, not only visitors but also local agents adherence and involvement in route initiatives. This result suggests the need to better understand the conditioning factors that may help (a) create, (b) maintain, and (c) enhance effective cooperation, success, and sustainability of networks in wine tourism.

This study has some limitations, namely, the fact that not all route members participated in the study, that several topics were analyzed, while wine tourism agents had sometimes limited time to develop some of their ideas, so that results should be considered exploratory. Also, extrapolation to other routes is not recommended, but similar studies in other regions may help validate our exploratory results, particularly regarding the challenges of wine route development. In this vein, the study contributes to a better understanding of some aspects that may contribute to the development of wine tourism routes, promoting the satisfaction of its members and a truly collaborative work, while raising some questions that additional studies may help answer.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by: 1) the Research Unit on Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policies (UIDB/04058/2020) + (UIDP/04058/2020), funded by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. 2) the project TWINE – PTDC/GES-GCE/32259/2017 –POCI-01-0145-FEDER-032259, funded by FEDER, through COMPETE 2020 – Operational Programme Competitiveness and Internationalization (POCI) and by national funds (OPTDC/GES-GCE/32259/2017-E), through FCT/MCTES.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Weiler B, Hall CM. Special interest tourism. UK: Belhaven Press; 1992.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Alant K, Bruwer J. Wine tourism behaviour in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J Wine Res. 2004;15(1):27–37.10.1080/0957126042000300308Search in Google Scholar

[3] Almeida MJ. Wine tourism in Portugal. In: Szolnoki RCL, editor. Sustainable and Innovative Wine Tourism Success models from all around the world. France: Cajamar Caja Rural; 2021. p. 241–54.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Correia L, Passos Ascenção MJ, Charters S. Wine routes in Portugal: A case study of the Bairrada Wine Route. J Wine Res. 2004 [cited 2021 Mar 25];15(1):15–25. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjwr20.10.1080/0957126042000300290Search in Google Scholar

[5] Cruz-Ruiz E, Zamarreño-Aramendia G, de la Cruz ERR. Key elements for the design of a wine route. The case of La Axarquía in Málaga (Spain). Sustainability. 2020;12(21):1–19.10.3390/su12219242Search in Google Scholar

[6] Novais C, Antunes J. O contributo do Enoturismo para o desenvolvimento regional: o caso das Rotas dos Vinhos. 1o Congr Desenvolv Reg Cabo Verde. 2009;1253–80.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Cunha D, Carneiro MJ, Kastenholz E. “Velho Mundo” versus “Novo Mundo”: Diferentes perfis e comportamento de viagem do enoturista?. Rev Tur Desenvolv. 2020;34:113–28. https://proa.ua.pt/index.php/rtd/article/view/22354.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kastenholz E, Cunha D, Eletxigerra A, Carvalho M, Silva I. Exploring wine terroir experiences: A social mediaanalysis. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies. Singapore: Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH; 2021 [cited 2021 Feb 22]. p. 401–20. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-33-4260-6_35.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kastenholz E, Lane B. Delivering appealing and competitive rural wine tourism experiences. In: Routledge handbook of the tourist experience. UK: Routledge; 2021. p. 508–20.10.4324/9781003219866-41Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bregoli I, Hingley M, Del Chiappa G, Sodano V. Challenges in Italian wine routes: managing stakeholder networks. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2016;19(2):204–24.10.1108/QMR-02-2016-0008Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bruwer J. South African wine routes: Some perspectives on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tour Manag. 2003 Aug 1;24(4):423–35.10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00105-XSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Hojman DE, Hunter-Jones P. Wine tourism: Chilean wine regions and routes. J Bus Res. 2012;65(1):13–21.10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.009Search in Google Scholar

[13] Carneiro MJ, Kastenholz E, Cunha D, Duarte P, Pato ML. Desafios e implicações para a cocriação de experiências enoturísticas rurais sustentáveis. In: Kastenholz E, Carneiro MJ, Cunha D, editors. Experiências de Enoturismo no Centro de Portugal: Oportunidades de Cocriação, Inovação e Desenvolvimento Sustentável nas Rotas da Bairrada, do Dão e da Beira Interior. Aveiro, Portugal: Universidade de Aveiro; 2022. p. 188–201.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Beverland M. Wine tourism: A tale of two conferences. Int J Wine Mark. 2000 Feb;12(2):63–74.10.1108/eb008710Search in Google Scholar

[15] Schiffman L, Bednall D, Cowley E, O’Cass A, Watson J, Kanuk L. Consumer Behaviour. Sydney: Prentice-Hall; 2001 [cited 2021 Jan 27]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235361637_Consumer_Behaviour_2nd_Edition.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Salvado J, Kastenholz E. Ecossistemas de enoturismo sustentáveis via Coopetição [Sustainable wine tourism eco-systems through co-opetition]. Rev Tur Desenvolv. 2017 [cited 2021 Jan 27];27/28:1917–31. https://web.a.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=16459261&AN=130521241&h=yplgZcDIrO3hMQGtOrRjnZrB%2FRQeeEKIZJ1ZLPOTeSzd6BrF6qFxCZGXXoatHVmKFF3VNqSvDJZjZ0%2FempjYFQ%3D%3D&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLoca.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Holland T, Smit B, Jones GV. Toward a conceptual framework of terroir tourism: A case study of the Prince Edward County, Ontario Wine Region. Tour Plan Dev. 2014;11(3):275–91.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kastenholz E, Cunha D, Eletxigerra A, Carvalho M, Silva I. Exploring wine terroir experiences: A social media analysis. Smart Innov Syst Technol. 2021;209:401–20.10.1007/978-981-33-4260-6_35Search in Google Scholar

[19] Getz D, Brown G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour Manag. 2006 Feb 1;27(1):146–58.10.1016/j.tourman.2004.08.002Search in Google Scholar

[20] Hashimoto A, Telfer DJ. Positioning an emerging wine route in the Niagara region. J Travel Tour Mark. 2003 Nov 18;14(3–4):61–76.10.1300/J073v14n03_04Search in Google Scholar

[21] Carvalho M, Kastenholz E, Carneiro MJ. Co-creative tourism experiences–a conceptual framework and its application to food & wine tourism. Tour Recreat Res. 2021;1:1–25. 10.1080/02508281.2021.1948719.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Carmichael BA. Understanding the wine tourism experience for winery visitors in the Niagara region, Ontario, Canada. Tour Geogr. 2005;7(2):185–204.10.1080/14616680500072414Search in Google Scholar

[23] Getz D. Explore wine tourism: management, development & destinations. New York: Cognizant Communication Corporation; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kastenholz E, Costa A. “O Enoturismo como factor de desenvolvimento das regiões mais desfavorecidas” Adriano Costa Equiparado a Professor Adjunto da Escola Superior de Turismo e Hotelaria do Instituto Politécnico da Guarda [Internet]; 2009 [cited 2021 Jan 27]. http://www.apdr.pt/congresso/2009/pdf/Sessão15/157A.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Sidali KL, Kastenholz E, Bianchi R. Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. J Sustain Tour. 2015;23(8–9):1179–97. 10.1080/09669582.2013.836210.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Charters S, Ali-Knight J. Who is the wine tourist? Tour Manag. 2002;23(3):311–9.10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00079-6Search in Google Scholar

[27] Massa C, Bédé S. A consumer value approach to a holistic understanding of the winery experience. Qual Mark Res. 2018;21(4):530–48.10.1108/QMR-01-2017-0031Search in Google Scholar

[28] O’Neill M, Charters S. Service quality at the cellar door: Implications for Western Australia’s developing wine tourism industry. Manag Serv Qual An Int J. 2000 Apr 1;10(2):112–22.10.1108/09604520010318308Search in Google Scholar

[29] Kastenholz E, Eusébio C, Carneiro MJ. Purchase of local products within the rural tourist experience context. Tour Econ. 2016;22(4):729–48.10.1177/1354816616654245Search in Google Scholar

[30] Festa G, Shams SMR, Metallo G, Cuomo MT. Opportunities and challenges in the contribution of wine routes to wine tourism in Italy – A stakeholders’ perspective of development. Tour Manag Perspect. 2020;33(January 2019):100585. 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100585.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Miranda Escolar B, Fernández Morueco R. Vino, turismo e innovación: las Rutas del Vino de España, una estrategia integrada de desarrollo rural Wine, Tourism and Innovation: the Wine Routes of Spain, an Integrated Strategy of Rural Development. [cited 2023 Feb 17]. www.revista-eea.net.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Vukojević D, Tomić N, Marković N, Mašić B, Banjanin T, Bodiroga R, et al. Exploring Wineries and Wine Tourism Potential in the Republic of Srpska, an Emerging Wine Region of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustain. 2022;14(5):2485.10.3390/su14052485Search in Google Scholar

[33] Lane B, Kastenholz E. Rural tourism: the evolution of practice and research approaches – towards a new generation concept? J Sustain Tour. 2015;23(8–9):1133–56. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsus20.10.1080/09669582.2015.1083997Search in Google Scholar

[34] Pato L, Kastenholz E. Marketing of rural tourism – a study based on rural tourism lodgings in Portugal. J Place Manag Dev. 2017;10(2):121–39.10.1108/JPMD-06-2016-0037Search in Google Scholar

[35] Kastenholz E, Marques CP, Carneiro MJ. Wine tourist experiences in rural areas. In: Agapito D, Ribeiro MA, KMW, editor. Handbook on the Tourist Experience: Design, Marketing and Management. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2022. p. 315–30.10.4337/9781839109393.00029Search in Google Scholar

[36] Brás JM, Costa C, Buhalis D. Network analysis and wine routes: the case of the Bairrada Wine Route. Serv Industries J. 2010 [cited 2022 Feb 4];30(10):1621–41. 101080/02642060903580706.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Meyer-Cech K. Regional co-operation in rural theme trails. In: Hall D, Kirkpatrick I, Mitchell M, editors. Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business. Ridge Summit: Channel View Publications; 2005, p. 137–48.10.21832/9781845410131-011Search in Google Scholar

[38] Galletto L. Tomo 50 • N° 1 •. Rev FCA UNCUYO 2018. 2018;50(1):157–70.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Lanfranchi M, Giannetto C, Dragulanescu I. A new economic model for Italian farms: The wine & food tourism. J Knowl Manag Econ Inf Technol. 2013;3(6):1–16.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Faraoni M, Pucci T, Rabino S, Zanni L. Does brand market value affect consumer perception of brand origin in the purchasing process? The case of Tuscan wines. Mercat E Compet. 2017 Apr 28 [cited 2023 Feb 17];1:51–78. https://usiena-air.unisi.it/handle/11365/1005883.10.3280/MC2017-001004Search in Google Scholar

[41] Pucci T, Pucci T, Faraoni M, Rabino S, Zanni L. Willingness to pay for a regional wine brand. Micro Macro Mark. 2016 Dec 30 [cited 2023 Feb 17];XXV(1/2016):39–54. 10.1431/82867.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Briedenhann J, Wickens E. Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas–vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tour Manag. 2004;25(1):71–9.10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00063-3Search in Google Scholar

[43] Lavandoski J, Vargas-Sánchez A, Pinto P, Silva JA. Causes and effects of wine tourism development in organizational context: The case of Alentejo, Portugal. Tour Hospitality Res. 2018 Jan;18(1):107–22.10.1177/1467358416634159Search in Google Scholar

[44] Ellis A, Park E, Kim S, Yeoman I. Progress in Tourism Management What is food tourism? Tour Manag. 2018 [cited 2023 Feb 17];68:250–63. 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.025.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Santos VR, Ramos P, Almeida N, Santos-Pavón E. Wine and wine tourism experience: a theoretical and conceptual review. Worldw Hosp Tour Themes. 2019;11(6):718–30.10.1108/WHATT-09-2019-0053Search in Google Scholar

[46] Alberdi Collantes JC. El prestigio de la marca y la promoción turistica, claves del éxito de la ruta del vino de la Rioja Alavesa. Lurralde Investig y Espac. 2018;41(41):5–32.10.52748/lurralde.2018.41.53Search in Google Scholar

[47] Lewis GK, Byrom J, Grimmer M. Collaborative marketing in a premium wine region: The role of horizontal networks. Int J Wine Bus Res. 2015 Aug 17;27(3):203–19.10.1108/IJWBR-06-2014-0028Search in Google Scholar

[48] Arfini F, Bertoli E, Donati M, Mancini MC. The wine routes: analysis of a rural development tool. In Système Agroalimentaire Localisés, Conference, Montpellier, France; 2003. p. 1–18.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Borges MC, Menezes DCde. Motivations for tourism adoption by vineyards worldwide: A literature review. BIO Web Conferences. vol. 12. 2019 [cited 2023 Feb 17]. p. 03005. https://www.bio-conferences.org/articles/bioconf/full_html/2019/01/bioconf-oiv2018_03005/bioconf-oiv2018_03005.html.10.1051/bioconf/20191203005Search in Google Scholar

[50] Trišić I, Štetić S, Privitera D, Nedelcu A. Wine routes in Vojvodina Province, Northern Serbia: A tool for sustainable tourism development. Sustain. 2020;12(1):1–14.10.3390/su12010082Search in Google Scholar

[51] Cunha D, Carneiro MJ, Kastenholz E. Journal of Tourism & Development. Rev Tur Desenvolv. 2020 Nov 19 [cited 2021 Jan 26];34:113–28. https://proa.ua.pt/index.php/rtd/article/view/22354.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Hall CM, Cambourne B, Macionis N, Johnson G. Wine tourism and network development in Australia and New Zealand: Review, establishment and prospects. Int J Wine Mark. 1997;9(2):5–31.10.1108/eb008668Search in Google Scholar

[53] Hall CM, Mitchell R. Wine tourism in the Mediterranean: A tool for restructuring and development - Hall - 2000 - Thunderbird International Business Review - Wiley Online Library. Thunderbird Int Bus Rev. 2000 [cited 2023 Feb 17];42(4):445–65. 10.1002/1520-6874%28200007/08%2942%3A4%3C445%3A%3AAID-TIE6%3E3.0.CO%3B2-H.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Montella MM, Cavicchi A, Santini C, Rosen MA. Wine Tourism and Sustainability: A Review. Sustainability. 2017;9(1):113. www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability.10.3390/su9010113Search in Google Scholar

[55] Sekulic D, Petrovic A, Dimitrijevic V. Who are wine tourists? An empirical investigation of segments in Serbian wine tourism. Ekon Poljopr. 2017;64(4):1571–82.10.5937/ekoPolj1704571SSearch in Google Scholar

[56] Itervitis. The European Federation Iter Vitis [Internet]. https://itervitis.eu/the-federation/.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Simões O. Enoturismo em Portugal: as Rotas de Vinho. PASOS Rev Tur y Patrim Cult. 2008;6(2):269–79.10.25145/j.pasos.2008.06.020Search in Google Scholar

[58] REGULAMENTO INTERNO DA ASSOCIAÇÃO ROTA DA BAIRRADA - PDF Free Download [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 12]. https://docplayer.com.br/75617714-Regulamento-interno-da-associacao-rota-da-bairrada.html.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Carvalho LC, Soutinho C, Paiva T, Leal S. Territorial intensive products as promoters of regional tourism. The case study of douro skincare. HOLOS. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Feb 18];4:122–36. https://www2.ifrn.edu.br/ojs/index.php/HOLOS/article/view/5243.10.15628/holos.2018.5243Search in Google Scholar

[60] Martins J, Gonçalves R, Branco F, Barbosa L, Melo M, Bessa M. A multisensory virtual experience model for thematic tourism: A Port wine tourism application proposal. J Destin Mark Manag. 2017;6(2):103–9. 10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.02.002.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Santos F, Vavdinos N, Martinez L. Progress and prospects for research of Wine Tourism in Portugal. Pasos Rev Tur Y Patrim Cult. 2020;18(1):159–70, www.pasosonline.org.10.25145/j.pasos.2020.18.010Search in Google Scholar

[62] Portuguese Wine Tourism - Programa de ação para o Enoturismo 2019-2021; 2019. p. 71. http://www.turismodeportugal.pt/SiteCollectionDocuments/estrategia/programa-acao-enoturismo-et2027-mar-2019.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Røddesnes S, Faber HC, Jensen MR. NVivo courses in the library: Working to create the library services of tomorrow. Nord J Inf Lit High Educ. 2019 Jun 25 [cited 2023 Feb 18];11(1):27–38, https://noril.uib.no/article/view/2762.10.15845/noril.v11i1.2762Search in Google Scholar

[64] PORDATA. https://www.pordata.pt/#AnchorCensos; 2022. https://www.pordata.pt/#AnchorCensos.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Eusébio C, Kastenholz E, Breda Z. Tourism and sustainable development of rural destinations: A stakeholders’ view. Rev Port Estud Reg. 2014;36(1):13–21.10.59072/rper.vi36.418Search in Google Scholar

[66] Holland T, Smit B, Jones GV. Toward a conceptual framework of terroir tourism: A case study of the Prince Edward County, Ontario Wine Region. Tour Plan Dev. 2014 [cited 2021 Jan 25];11(3):275–91. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rthp21.10.1080/21568316.2014.890125Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants