Abstract

Indonesia has a dry land area of 79.69%, with low soil productivity (physical, chemical, and biological), as well as uneven and unpredictable rainfall. The dryland potential is optimally utilized using biofertilizers that can produce microbes to increase soil fertility. This research aims to determine the effects of biofertilizers on dryland improvement and crop production. The study was conducted from February to May 2021 in Central Java, Indonesia. Using a randomized block design in peanut cultivation. Six biofertilizers (Controlled, Agrimeth, BioNutrient, Gliocompost, Agrimeth + BioNutrient, Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost) were applied with four replications. The performance of each biofertilizer was assessed based on chemical soil parameters, soil microbe population, plant growth, and yields. The soil in the study area belonged to the Inceptisols group and exhibited moderately acidic pH, low organic carbon content, and low nitrogen levels. However, it had high potential and available phosphorus, as well as moderate potential and high available potassium. BioNutrient and Gliocompost increased available phosphate by 12 and 19%, respectively, due to the presence of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Aspergillus sp. Agrimeth influenced the population of Azospirillum (45–63%) and enhanced phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost promoted the growth of the Azospirillum and Trichoderma populations (17–18%), resulting in a 45.04% increase in profits. Biofertilizer inoculation positively affected peanut development, root nodule formation, and yield. This novelty showed the potential of biofertilizers in improving dryland conditions, increasing crop productivity, and contributing to sustainable agriculture in the long term.

1 Introduction

The program to increase food production still relies heavily on the potential of lowland fields, while the opportunities and potential of dryland are yet to be optimally utilized. In general, dryland has lower productivity. Most of the dryland in Indonesia is in less than optimal (sub-optimal) conditions. Sub-optimal land is defined as land that naturally has low productivity due to internal (physical, chemical, and biological soil conditions) and external (such as rainfall and temperature) limiting factors [1].

Sub-optimal land use will be the foundation of hope for the future, but it requires technological innovation to overcome the obstacles according to the characteristics and typology of the land. Due to the limited reserves of fields, it must immediately change the orientation by preparing alternatives to increase production on dryland to meet national food needs.

Dryland in Indonesia was about 79.69% of the existing land area, while lowland fields are only 20.31% [2]. Central Java province has 712,111 ha of dryland and 18,546 ha of lowland fields [3]. The sub-optimal land was identified as an acidic sub-optimal dryland of 34.3% and a dry sub-optimal climate of around 19.8% in Central Java [1]. Sub-optimal dryland in Central Java is generally dominated by food crop development such as upland rice, corn, peanuts, soybeans, and cassava with varying cropping patterns, monoculture, and intercropping [4].

As one of the sub-optimal lands, dryland productivity can be increased through adaptive technological innovations supported by appropriate land management technology [5]. The main constraints on dryland revolve around the problems of moderate to high acidity levels, low availability of macronutrients, organic C content, cation exchange capacity, and base saturation [6]. In addition, the elements of Al and Fe are also usually high. These element factors inhibited nutrient availability and can be concentrated in the root, so it has the potential to inhibit the availability of essential elements to poison plants [7,8,9]. These conditions encourage the need for research on adaptive agricultural technology to increase sub-optimal dryland productivity.

Land enhancement technology should be prioritized to reduce the effect of low soil fertility using ameliorant materials such as dolomite, organic matter, biochar, and biofertilizers [10,11]. Biofertilizers are non-pathogenic microbial-based fertilizers that increase soil fertility and health through several activities produced by these microbes, including fixing nitrogen, dissolving phosphates, and producing phytohormones [12].

Soil fertility determines plant growth and productivity. Land improvement with biological fertilizers is a technological innovation for increasing dryland productivity. Biological fertilizers such as Agrimeth and BioNutrient and Gliocompost have been reported to contain several microbes, including Methylobacterium sp., Azotobacter sp., Bacillus sp., Rizhobium sp., and Bradyrhizobium japonicum [13,14].

Agrimeth contains nitrogen-fixing and phosphate-solvent microbes. BioNutrient contains Alcaligenes, Azospirillum sp., and Bacillus sp. microbes. Furthermore, Gliocompost contains Azotobacter sp., Azospirillum sp., Bacillus sp., and Pseudomonas fluorescens [7].

The microbes have enzymatic activity as well as phytohormones. They have a positive effect on macro and micronutrient uptake in the soil, promoting growth, flowering, seed ripening, breaking dormancy, increasing seed vigor and viability, efficient absorption of inorganic compound fertilizers, and crop productivity.

Methylobacterium inoculation can induce plant resistance to diseases caused by pathogens [15,16]. Biofertilizers containing Azospirillum sp. and Azotobacter sp. [17] significantly increased rice growth variables and compound fertilizer uptake. Arbuscular mycorrhizae and rhizobium interaction with their host plants increased nitrogen and phosphorus uptake, resulting in the highest dry weight and seed yield [18].

Biofertilizers are expected to be an alternative technology that can help improve nutrient balance in the soil. It can sustainably increase land and plant productivity [10,19]. This research aims to determine the effect of biofertilizers on land improvement and crop production.

2 Materials and methods

The study employed a randomized block design in peanut cultivation, with the experimental plots set up in sub-optimal dryland in Watangrejo, Pracimantoro, Wonogiri, Central Java, Indonesia (−8.097180 S, 110.800758 E). The study period lasted from February to May 2021.

The design involved six treatments and four replications, resulting in a total of 24 experimental plots. The treatments included a control group (P1) and five different biofertilizer treatments: Agrimeth (P2), BioNutrient (P3), Gliocompost (P4), Agrimeth + BioNutrient combination (P5), and Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost combination (P6). Biofertilizers were applied through seed treatment, with any remaining solution sprinkled onto the land according to each treatment.

The study involved multiple observations and analyses. Chemical soil parameters, such as pH, organic carbon, total nitrogen (N), potential phosphorus (P), potential potassium (K), available P, and available K, were assessed. The population of soil microbes, including Azotobacter sp., Rhizobium sp., Azospirillum sp., Trichoderma sp., and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, was measured at the beginning and end of the study.

Soil samples and microbes were collected and analyzed in Chemistry Laboratory at the Assessment Institute for Agricultural Technology of Central Java. Agrometeorological data, necessary for assessing the study’s supporting data on the climatic conditions, were obtained from the Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resource (POWER) Data Access Viewer [20].

Plant growth parameters, such as plant height, canopy diameter, number of branches, and number of root nodules, were recorded. Plant yields, including stover, unpeeled peanut, seed weight, and overall yield, were also determined.

The data on plant growth and yields were analyzed both descriptively and statistically. Descriptive analysis involved summarizing and presenting the data using appropriate statistical measures. The Duncan Multiple Range Test was applied to compare the means among different treatments. This test helps identify significant differences between treatment groups [39].

In terms of economic feasibility, the analysis uses a simple benefits analysis and Marginal Benefit Cost Ratio (MBCR) approach. Benefits analysis was focused on considering only the differences in main inputs and yields [21], while MBCR determined the feasibility of new technology (NT). This analysis aims to assess the economic feasibility of changing treatment compared to farmers’ practices. MBCR was calculated as added returns by shifting to NT from farmer technology/additional costs incurred by shifting to NT. The use of NT was considered feasible if the increase in the value of profits was MBCR >2 [22].

3 Results

3.1 Soil characteristics

The site land has chemical characteristics that were relatively less optimal for plant growth, such as moderately acidic soil pH and low content of soil organic C and N. The potential P and available P elements were in high status, whereas the content of potential K was moderate and available K was high. This condition indicates an imbalance of nutrients in the soil, causing land productivity to be less than optimal. The potassium content in the soil was seen to decrease descriptively but did not change the status of the category, which was very high. The decline that occurred descriptively in all treatments was thought to be due to environmental factors, and very high rainfall throughout the study, because of which there was leaching of potassium elements. The average potassium after biofertilizer treatment was still higher than the control (Table 1).

Soil chemical properties before and after the study

| Detail | pH_H2O | pH_KCl | C Org | Total N (Kjeldahl) | P2O5_HCl | K2O_HCl | P2O5 (Olsen) | Available K (Morgan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 5.89 | 5.00 | 1.24 | 0.19 | 56.79 | 19.64 | 20.71 | 232.84 |

| Moderately acid | Acid | Low | Low | High | Moderate | Very high | Very high | |

| P1 | 5.70 | 4.79 | 1.14 | 0.18 | 30.33 | 27.24 | 19.34 | 146.73 |

| P2 | 5.78 | 4.81 | 1.23 | 0.18 | 31.14 | 27.31 | 18.36 | 154.68 |

| P3 | 5.82 | 4.80 | 1.11 | 0.18 | 32.86 | 28.10 | 23.25 | 156.31 |

| P4 | 5.77 | 4.75 | 1.18 | 0.18 | 34.38 | 19.10 | 24.68 | 223.58 |

| P5 | 5.79 | 4.80 | 1.08 | 0.17 | 34.96 | 21.31 | 21.24 | 199.87 |

| P6 | 5.74 | 4.78 | 1.14 | 0.18 | 38.16 | 24.46 | 22.57 | 211.76 |

| Moderately acid | Acid | Low | Low | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high |

3.2 Climate condition

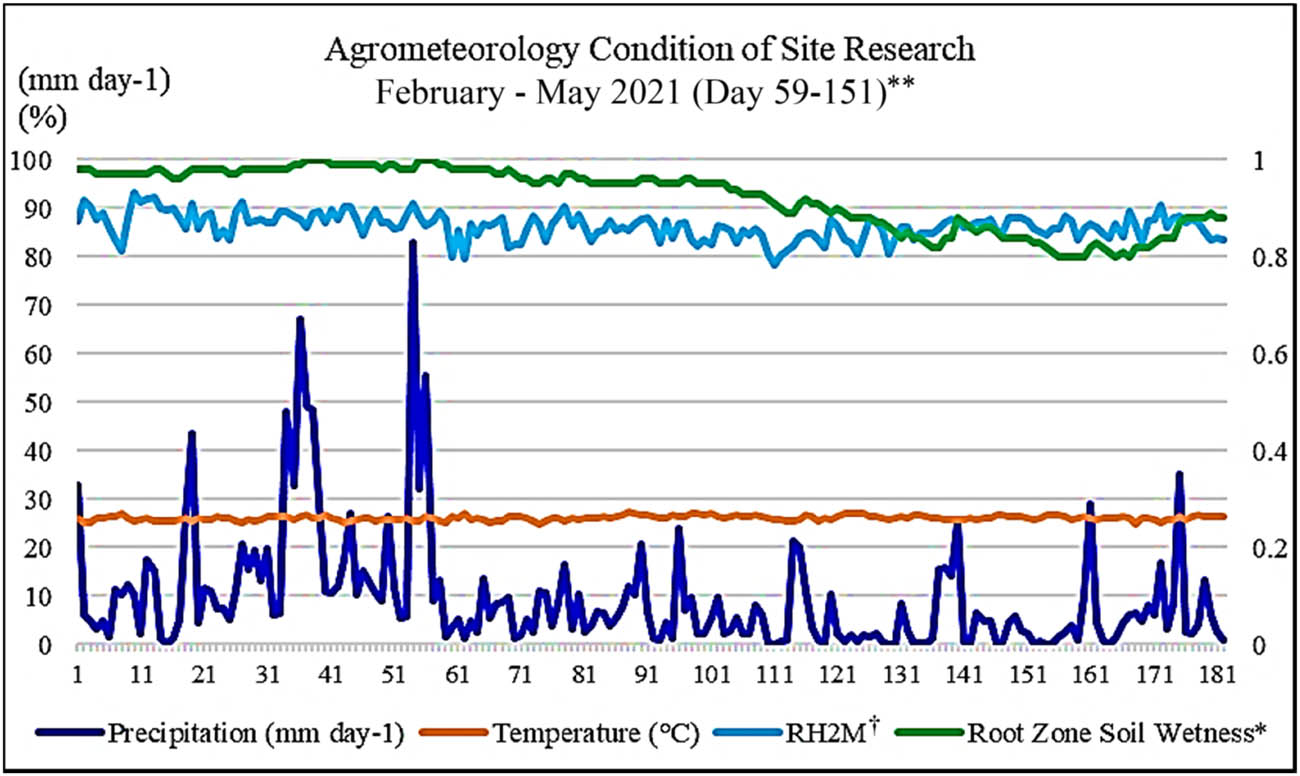

In addition to limiting issues induced by soil characteristics, sub-optimal drylands are also confronted with environmental limits, particularly unpredictable rainfall, and temperature. The research location was dryland with a humid climate with an uneven distribution pattern of rainfall throughout the year. The average rainfall under normal conditions was around 1,400 mm/year, with a dry month range (<60 mm/month) of 6 months [23]. The climatic conditions during the research period (February–May 2021) are shown in Figure 1.

Climate condition. *The root zone wettability percentage value of 0 indicates that the soil was completely free of water and a value of 1 indicates the soil was completely saturated, where the root zone was the layer from the surface 0 to 100 cm below the soil. †RH2M is the relative humidity (%) at 2 m. **Source of data: NASA POWER Data Access Viewer-Prediction of worldwide energy resource-agro climatology location of latitude −8.0972, longitude 110.8008, 2021. https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/.

The rainfall data during the research period (from day 59 to 151 in 2021) were far beyond normal conditions, reaching about 520 mm/3 months or about 170 mm/month, with an average air temperature of around 26°C at the soil surface. The soil moisture in the root zone was at a level of 0.9. Soil moisture at level 0.9 indicates that the soil was almost always saturated with water, almost 90% of the entire soil pore space (Figure 1).

3.3 Soil microbiology

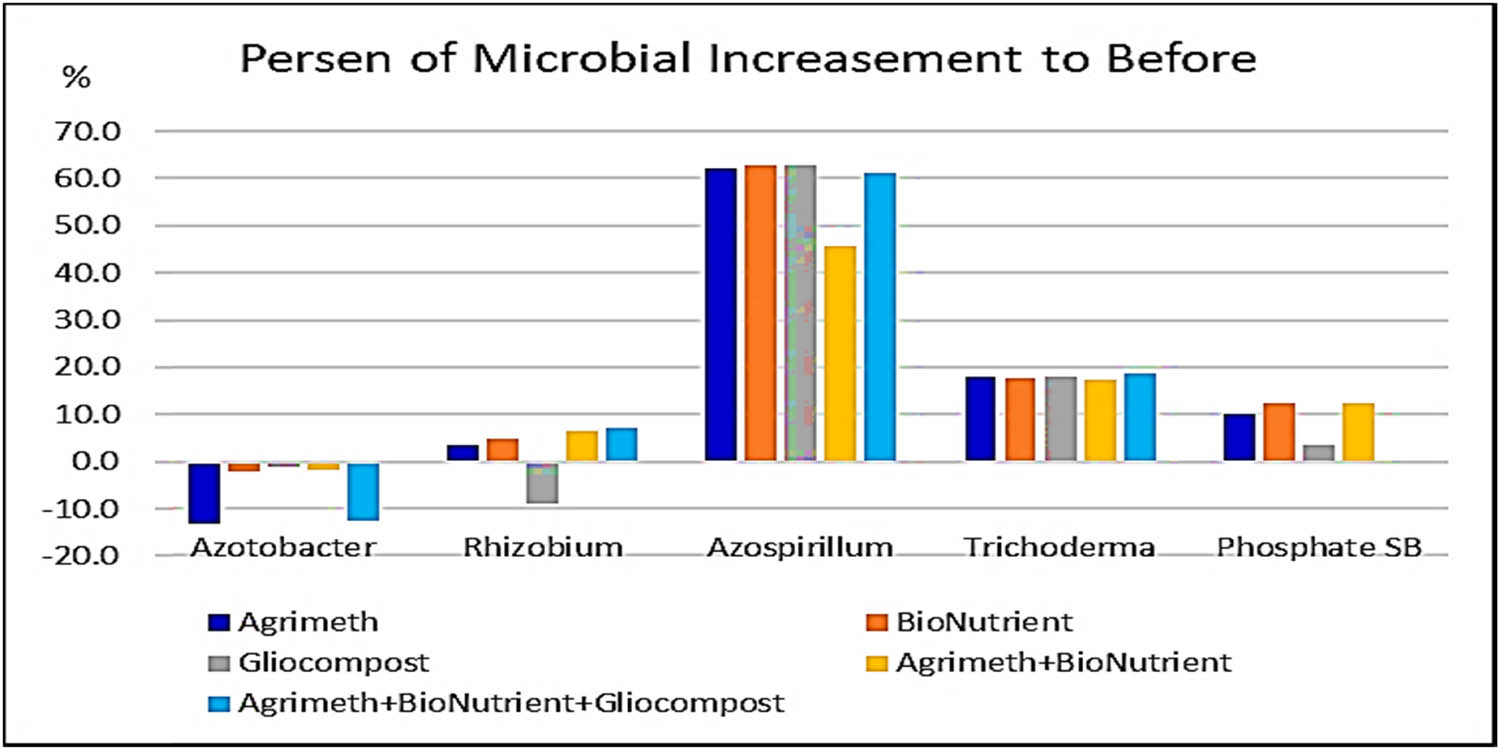

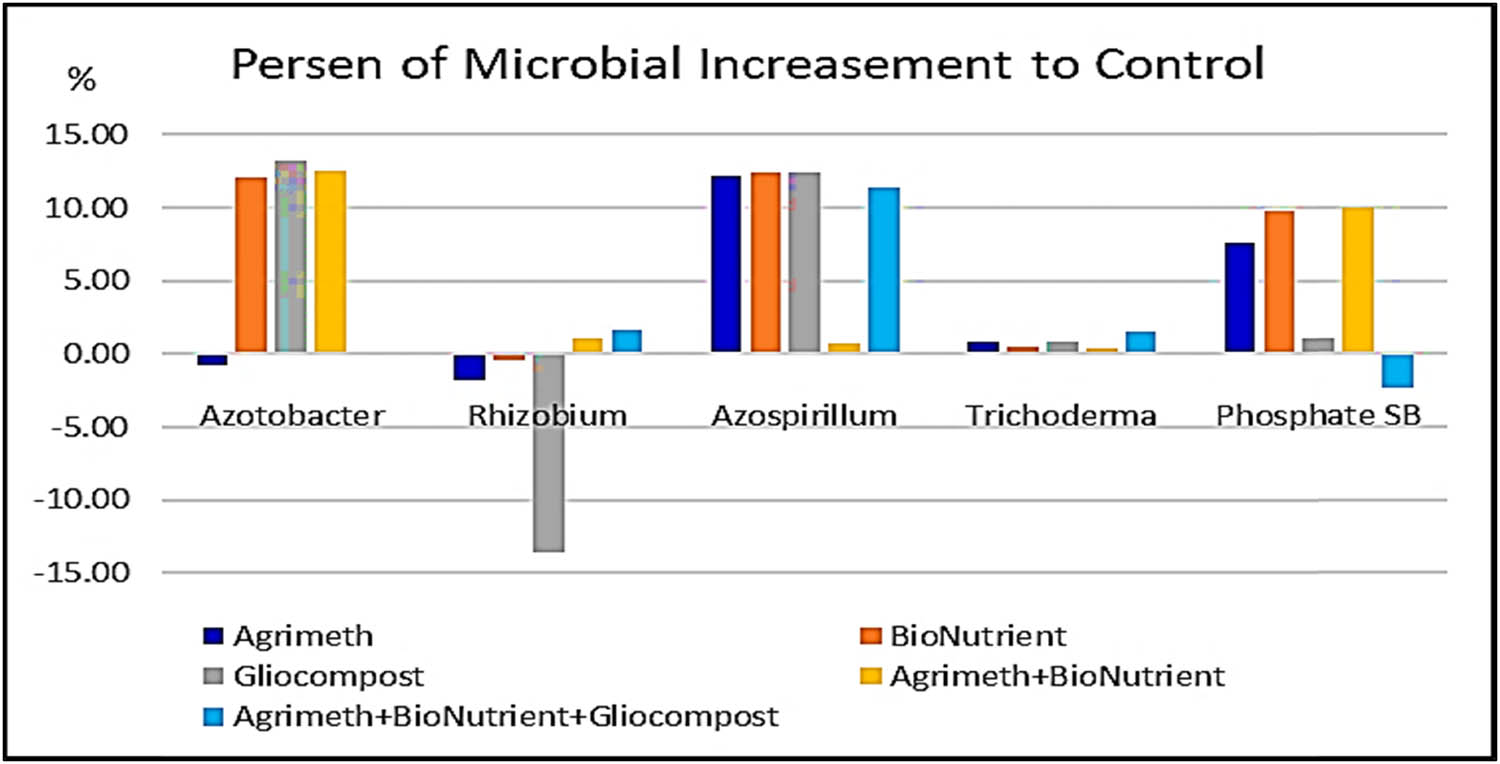

Land improvement using biological fertilizers affects the soil’s microbial population before and after the study. The Azospirillum population increased significantly in the range of 45–63% compared to that before the study and increased by 0.6–13% from the control without biological fertilizers. The combination of Gliocompost + BioNutrient + Agrimeth increases the Azospirillum population. Meanwhile, the combined application of Agrimeth + BioNutrient increased the Azospirillum population, which was lower than the single application but still higher than the control. The Trichoderma population increased by 17–18% from before the study but was not significantly different from the control, with an average increase of 0.36–1.48%. The combination Gliocompost + BioNutrient + Agrimeth also intensifies the Trichoderma population (Figures 2–4, Table 2).

Soil microbial populations before and after biofertilizer application.

Percentage increase in microbial in biofertilizer application from before treatment.

Percentage increase in microbial in biofertilizer application compared to control.

Soil microbial characteristics before and after the study

| Microbial population (cfu/g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Azotobacter sp. | Rhizobium sp. | Azospirillum sp. | Trichoderma sp. | Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria | |

| Before | P01 | 3.4 × 108 | 4.0 × 107 | 3.2 × 104 | 1.9 × 106 | 3.8 × 108 |

| P02 | 6.8 × 108 | 3.2 × 108 | 3.7 × 105 | 3.2 × 106 | 5.0 × 108 | |

| After | P1 | 4.0 × 107 | 5.0 × 108 | 4.7 × 107 | 3.1 × 107 | 7.0 × 108 |

| P2 | 3.5 × 107 | 3.5 × 108 | 4.0 × 108 | 3.6 × 107 | 3.3 × 109 | |

| P3 | 3.3 × 108 | 4.6 × 108 | 4.2 × 108 | 3.4 × 107 | 5.1 × 109 | |

| P4 | 4.0 × 108 | 3.3 × 107 | 4.2 × 108 | 3.6 × 107 | 8.7 × 108 | |

| P5 | 3.6 × 108 | 6.2 × 108 | 5.3 × 107 | 3.3 × 107 | 5.3 × 109 | |

| P6 | 4.1 × 107 | 7.0 × 108 | 3.5 × 108 | 4.0 × 107 | 4.3 × 108 | |

3.4 Plant growth

Research on the effect of biofertilizers on the growth and production of peanuts was carried out during one growing season. The average value of the peanut plant growth variable in biological fertilizer treatments is presented in Table 3.

Peanuts growth variables

| Treatment | Plant high 38 DAP** (cm) | Plant high 92 DAP** (cm) | Plant canopy diameter 38 (cm) | Plant canopy diameter 66 (cm) | Branch number 38 DAP | Branch number 66 DAP** | Root nodule number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 24.9a* | 50.5a* | 26.0a* | 44.2a* | 6a* | 6a* | 45a* |

| P2 | 24.6a | 51.2a | 25.3a | 46.0a | 6a | 7a | 65ab |

| P3 | 23.7a | 52.9a | 26.2a | 47.3a | 6a | 7a | 74abc |

| P4 | 24.2a | 46.4a | 26.9a | 48.0a | 7a | 7a | 76bcd |

| P5 | 23.2a | 52.1a | 27.7a | 46.4a | 6a | 7a | 105d |

| P6 | 24.6a | 52.9a | 26.7a | 44.5a | 6a | 7a | 97cd |

*The same letter in the same column was not significantly different based on DMRT 5%. **DAP – days after planting.

The application of biological fertilizers did not significantly affect the peanut’s growth component, due to very high rainfall during the study, which was 170 mm/month. Meanwhile, peanut plants require ideal growing conditions such as 800–1,300 mm/year rainfall or equivalent to 100–200 mm/month wet or about 3–7 mm/day; 28–30°C air temperature; humidity 65–75%; and slightly moist soil with good drainage (Table 3).

3.5 Yield

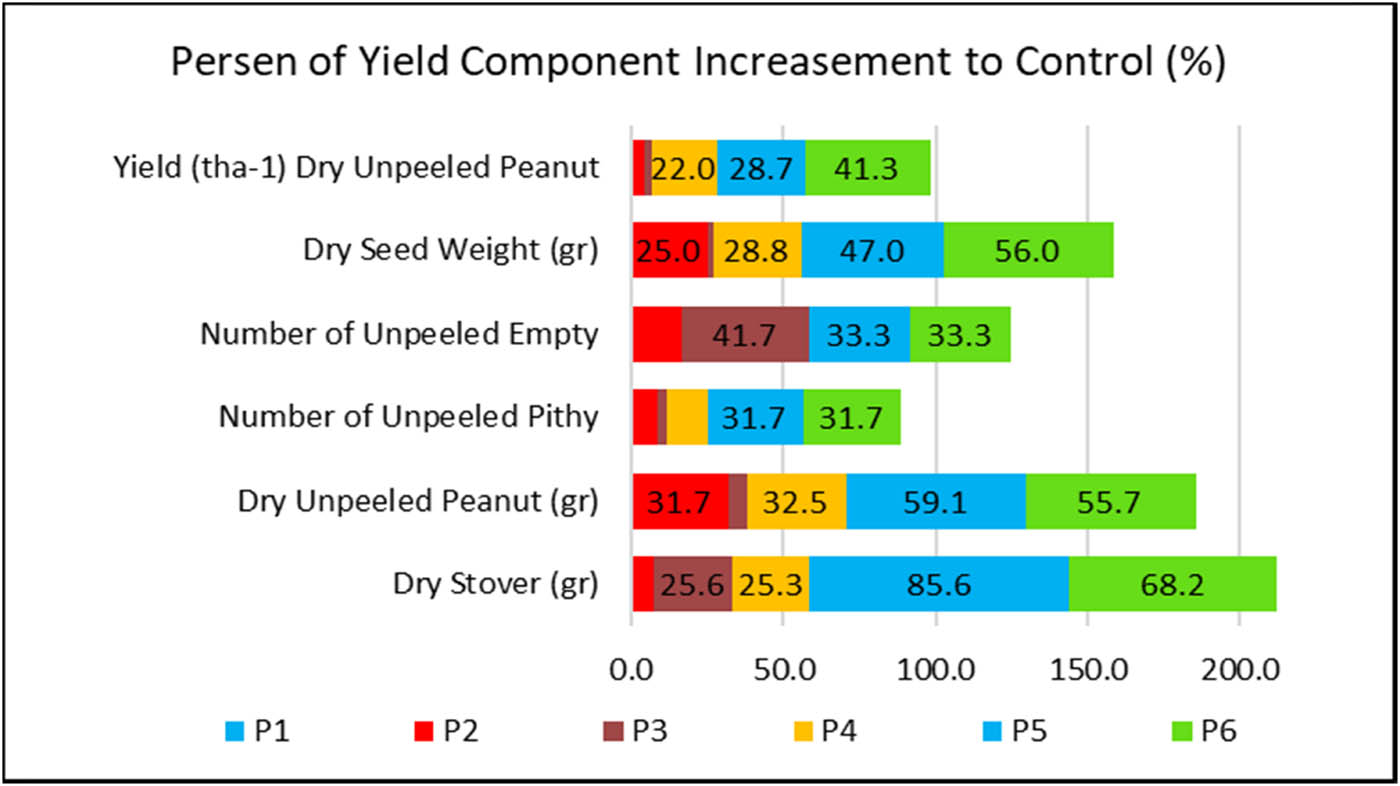

The study on land improvement using biological fertilizers was also carried out to see its effect on peanut crop yields. The use of biological fertilizers for land improvement is yet to show a significant effect on peanut yields. The resultant yields show a positive tendency to increase in one growing season, with relatively abnormal weather conditions. Data on the components and yield of peanuts in several biofertilizer treatments are presented in Table 4 and Figure 5.

Peanut yield components

| Treatment | Fresh stover (g) | Dry stover (g) | Fresh unpeeled peanut (g) | Dry unpeeled peanut (DUP) (g) | Unpeeled pithy | Unpeeled empty | Dry seed weight (g) | Yield (t/ha) DUP** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 61.13a* | 18.32a* | 24.13a* | 16.32a* | 20a* | 4a* | 12.98a* | 2.85a* |

| P2 | 65.89a | 19.72a | 30.21abc | 21.50ab | 22a | 5a | 16.23ab | 2.98a |

| P3 | 76.51ab | 23.01ab | 25.58ab | 17.38a | 21a | 6a | 13.22a | 2.91a |

| P4 | 77.65ab | 22.95ab | 34.81abc | 21.62ab | 23a | 4a | 16.72ab | 3.48a |

| P5 | 114.23c | 33.99c | 37.78c | 25.96b | 26a | 5a | 19.08b | 3.67a |

| P6 | 102.44bc | 30.81bc | 36.70bc | 25.41b | 26a | 5a | 20.25b | 4.03a |

*The same letter in the same column was not significantly different based on DMRT 5%. **DUP – Dry Unpeeled Peanut.

Peanut yield components on biofertilizers application.

3.6 Benefit analysis

The MBCR calculation was derived from total production costs (seeds, fertilizer, labor) that change due to the new implementations of soil amelioration using a biofertilizer and revenue from the sales of peanuts. MBCR can be determined by the difference between profits and costs that can be achieved by implementing introduced innovations. The highest increase in benefit was achieved by applying a combination of three types of biofertilizers (Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost), with an increase in the yield of 45.04% (Table 5).

Benefit analysis in the assessment of soil amelioration

| Treatment | Total Cost (IDR/ha) | Yield (t/ha) | Revenue (IDR/ha) | Benefit (IDR/ha) | Increase | MBCR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Revenue | ||||||||

| IDR/ha | % | IDR/ha | % | ||||||

| P1 | 3,590,000 | 2.85 | 22,804,480 | 19,214,480 | − | − | − | − | − |

| P2 | 4,024,000 | 2.98 | 23,827,200 | 19,803,200 | 434,000 | 1.21 | 588,720 | 3.06 | 1.36 |

| P3 | 3,850,000 | 2.91 | 23,283,200 | 19,433,200 | 260,000 | 0.07 | 218,720 | 1.14 | 0.84 |

| P4 | 3,674,000 | 3.48 | 27,831,040 | 24,157,040 | 84,000 | 0.02 | 4,942,560 | 25.72 | 58.84 |

| P5 | 4,284,000 | 3.67 | 29,354,240 | 25,070,240 | 694,000 | 0.19 | 5,855,760 | 30.48 | 8.44 |

| P6 | 4,368,000 | 4.03 | 32,237,440 | 27,869,440 | 778,000 | 0.22 | 8,654,960 | 45.04 | 11.12 |

4 Discussion

4.1 Soil characteristics

The research was conducted in a dryland area with Inceptisols (Typic Dystrudepts) soil, which has a loamy clay texture. The limitations of this soil type resulted in conditions that were less than optimal. To determine the effect of using biofertilizers on land improvement, the chemical and biological properties of the soil before and after the treatment were studied. Some of the soil chemical characteristics included pH, organic C content, total and available N, total and available P, and total and available K. The biological characteristics of the soil observed included the populations of Azotobacter sp., Rhizobium sp., Azospirillum sp., Trichoderma sp., and solubilizing phosphate bacteria.

Biofertilizer is expected to be an alternative technology that can help improve soil nutrient balance, increase land productivity, and increase plant growth in the long run [10,19,21]. Land improvement using biofertilizers did not show changes in soil chemical properties from before the study. The available nitrogen content (

The influence of the activities of symbiotic and non-symbiotic bacteria contained in biofertilizers, such as Azotobacter, Azospirillum, Bacillus sp., Rhizobium sp., Pseudomonas fluorescent, and Bradyrhizobium, the available P2O5 content remained very high before and after the assessment, there was a tendency that rose descriptively in some biofertilizer treatments.

In the treatment of BioNutrient (P3) and Gliocompost (P4), there was an increase in the content of available P by 12 and 19% compared to before research, and 20 and 27% higher than the control. The increased availability of phosphate elements were thought to be one of the effects of using biological fertilizers containing Pseudomonas fluorescens and Aspergillus sp.

This increase in the availability of elemental content was the results of previous studies, that the application of biofertilizers containing N-fixing bacteria and phosphate solubilizing microbes + 50% N, P, and K increase soil phosphorus availability [9]. Applying organic and inorganic fertilizers, and biofertilizer packages significantly affect the parameters of organic C and soil available P [24].

4.2 Climate condition

Soil quality and climate conditions were indicators for evaluating increased crop production. Climate change mitigation was needed in managing agriculture based on nutrient-rich soil research. The pattern of suboptimal land management also needs to be driven by policy support [40].

Rainfall that exceeded normal during the study impacted the optimization of land improvement processes and plant productivity by applying biofertilizers. The effectiveness of commercial biofertilizers was incredibly reliant on seasonal and site-specific environmental factors [25]. Flowers would be challenging to pollinate and fall out due to excessive rains. It affects rising soil water content and air moisture, causing poor plant growth and the rotting of some roots and pods [26].

Uncertainty of rainfall intensity and distribution was a major constraint and limiting agriculture factor in dryland. Therefore, in the long run, it was necessary to identify and delineate dryland areas with several main weather factors that often occur to obtain accurate information regarding land potential and alternative technological innovations to be implemented.

An integrated approach of two methodologies, Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index data, has been used to estimate the long-term changes in agricultural development areas. Three independent variables (rainfall, temperature, and agricultural area) were used in the multiple regression analysis to understand the impact of the main drivers affecting the crop production indicating an increasing trend in crop production. Correlation analysis indicated that crop production was significantly related to annual rainfall but less sensitive to temperature [27].

4.3 Soil microbiology

The application of biofertilizers seems to increase the population of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, especially the Agrimeth + BioNutrient combination, by 10–12% before the study. The combination of Agrimeth + BioNutrient also significantly increases the population of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria compared to the control (7–9%).

The use of Gliocompost only caused a slight increase in the population. Even when Gliocompost was combined with Agrimeth and BioNutrient, the phosphate-solubilizing bacteria population decreased slightly. This fact indicates the need for further research on mixing biofertilizers with phosphate-solubilizing bacteria populations. Adding bio-fertilizer changed the organization of the soil microbial population, backing up this theory. They found that adding biofertilizers had a more significant impact, notably in soil treated with bio sludge and bio sludge + Azotobacter [28].

The descriptive explanation confirms the prior knowledge that each biofertilizer tends to change specific microbial populations in suboptimal land. Agrimeth tends to increase the population of Azospirillum and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria positively. BioNutrient affects an increase in the populations of Azotobacter, Azospirillum, and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Meanwhile, Gliocompost tends to increase the population of Azotobacter and Azospirillum.

The combination of Agrimeth affected the population of Azotobacter and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Meanwhile, combining the three biofertilizers only increased the Azospirillum population. Continuous application of biofertilizers allows the microbial population to persist and grow in the soils, assisting in soil fertility maintenance and contributing to sustainable agriculture [29].

4.4 Plant growth

Applied biofertilizers tend to increase peanut growth by increasing plant height, plant crown diameter, and several branches. This performance was consistent with the findings of the present study, inoculation of Bacillus subtilis QST713 resulted in enhanced plant growth and total phosphorus content in cucumber plants and P total. [19,30]. Meanwhile, based on the development of peanuts, Gliocompost biofertilizer significantly influenced the rise in root nodules but was not significantly different from the biofertilizers Agrimeth + BioNutrient.

The use of Agrimeth + BioNutrient has proven to increase the number of nodules, but not statistically significantly different from the control. The combination of Agrimeth + BioNutrient produced the highest increase in root nodules. The number of nodules increased in the Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost combinations. This increase supports the findings of other studies [31,32], which concur that the presence of Bradyrhizobium in the soil promotes the formation of root nodules in peanuts and nitrogen fixation.

The application of biofertilizers significantly increases the growth of shoots and roots in green beans, cowpeas, and soybeans compared to controls. Biofertilizers were very effective on plant growth, nodulation, nitrogen fixation, nitrogen uptake, phosphorus, potassium, and yield of green bean and soybean seeds from N application [33].

Furthermore, biofertilizers Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Bradyrhizobium elkanii, and Streptomyces griseoflavus significantly increased plant growth, nodulation, nitrogen fixation, nutrient uptake, and soybean yields. Overall, the effectiveness of biofertilizers and the efficiency of soybean varieties have an important role in plant growth, nodule formation, nitrogen fixation, and higher yields [34].

4.5 Yield

The combination of biofertilizer Agrimeth + BioNutrient produced the highest dry weight compared to other treatments, with an increase of 85% than the control. Furthermore, the Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost increased dry weight by 68%. The combinations of Agrimeth + BioNutrient (P5) and Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost (P6) also significantly affect the quantitative parameters of dry unpeeled peanuts. Both treatments increased by 59 and 56% compared to the control, respectively.

The treatment of Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost resulted in the highest dry seed weight but produced a dry seed weight 56% heavier than the control. Furthermore, the high dry seed weight was obtained in the combination of Agrimeth + BioNutrient, with an increase of approximately 47% over the control.

Demonstrated that biofertilizer inoculation increased peanut development and yield components [32]. The use of biofertilizer 500 g Agrimeth/ha plus fertilizers (50 kg Urea + 150 kg Phonska)/ha also increases plant growth and yield by 0.25–0.70 t/ha or 15.15–33.33% compared to planting without biofertilizer [41].

The biofertilizer application has not significantly affected peanuts’ growth and yield components. The same was also seen in the average achievement of peanut yields, as presented in Table 4. The biofertilizers, independently or in combination, did not show statistically significant differences between controls and treatments. However, the yield of peanuts achieved by all treatments using biological fertilizers was relatively higher than when not using them. The 41.3% increase in yield was achieved in the combination treatment of Agrimeth + BioNutrient + Gliocompost (P6). Then, successive increases were shown in the treatment of P5 (28.7%), P4 (22.0%), P2 (4.5%), and P3 (2.2%).

Gliocompost biofertilizer contains a Pseudomonas microbe, which positively increases peanut yield. Pseudomonas-based biofertilizers could be an appropriate alternative to increase sweet potato yields, saving 50% of the currently recommended mineral fertilizers, and making them more environmentally friendly to support efficient and productive sustainable agriculture [35]. Furthermore, the application of biofertilizers such as Gliocompost, Probio, and Starmix were combined with 50% NPK recommended giving the increased yield, which means biofertilizers can make fertilizers efficient [42].

This phenomenon indicated that biofertilizers in a synergistic and integrated conditions have a better yield than the independent and partial applications. This study also gives hope that, in the long term, biofertilizers have positive prospects for field improvement and increased crop productivity.

The results indicated the application of biofertilizers proved to be able to increase the available P content, population of soil microbes (Azospirillum, Trichoderma, Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria), and peanut yield, although still at small level. This points that land improvement and crop productivity using biofertilizers needs to be carried out continuously but still must prioritize the ease and cheapness of the application. Therefore, the application of this innovation needs to be combined with more efficient technology.

Automation systems through the Internet of Things and cloud computing was one of the alternatives offered by two technologies that contribute to the development of smart technology by replacing traditional agricultural practices [36]. These smart devices monitor the needs of the plant health through sensors that can monitor temperature, soil moisture, sunlight intensity, soil air quality values, vibration, and humidity in the environment surrounding the plants. The network of sensors ensures that the plants will continue to be healthy and function in the right way. Follow-up research on dryland crop yields can be conducted to determine carbohydrates, protein, moisture, ash, fat, and fiber contents [43].

4.6 Benefit analysis

Benefit and MBCR analysis were presented in the use of innovative soil improvement technologies using a combination of three types of biofertilizers (Agrimeth-BioNutrient-Gliocompost) proved effective in increasing the yields and profits compared to the existing ones. The highest increase in profit was achieved by applying a combination of three types of biofertilizers together, with an increase in yield of 45.04%.

The second increase in profit occurred in Agrimeth and BioNutrient biofertilizers simultaneously. Meanwhile, Gliocompost biofertilizer proved to be the most effective in increasing yields and profits in biofertilizers independently, with a profit increase of 25.72% compared to the existing ones.

Application of technology using single or combinations of biological fertilizers in treatments P4, P5, and P6 was economically feasible and can be recommended to farmers [22]. Increasing benefits and reducing costs occurring in the application of this technology not only plays an important role in sustainably improving land but is also a solution for small farmers on marginal lands who want cheap inputs [37,38].

5 Conclusion

Biofertilizers application could improve agricultural sub-optimum and increase crop productivity. This study demonstrates the potential of biofertilizers to contribute to long-term sustainable agriculture. Biofertilizers (BioNutrient, Gliocompost, and Agrimeth) were shown to increase the beneficial microbe population (Azospirillum and Trichoderma), which play an essential role in nutrient availability and plant growth. The result indicated that biofertilizers effectively improve nutrient balance in the soil and available phosphorus, through the activities of microorganisms such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and Aspergillus sp. This study contributes to new knowledge by highlighting the importance of biofertilizers in improving sub-optimal drylands and increasing crop productivity. The findings emphasize the importance of adopting innovative approaches, such as biofertilizers, to harness the potential of drylands, assist in soil fertility maintenance, and achieve sustainable agriculture. The limitations of this study were abnormal weather conditions, so it was highly recommended that future research addresses these limitations and consider long-term studies to validate the findings. In addition, further research could explore the effects of different combinations and doses of biofertilizers on various crops in other dryland regions. The science community was encouraged to engage by exploring the possibility of biofertilizers in addressing sub-optimal dryland challenges and developing adaptive agricultural technologies. By doing so, we can promote sustainable agricultural development and meet the growing demand for food.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Center for the Study of Agricultural Technology in Central Java, the Agricultural Research and Development Agency, SEARCA, and the National Research and Innovation Agency for their support.

-

Funding information: This article was compiled from the results of research funded by the Agricultural Research and Development Agency, Ministry of Agriculture.

-

Author contributions: S – the main contributor, fully responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing; S.M. – the main contributor, contributed to investigation, data curation of soil chemical data, and writing – original draft; S.J. – the main contributor, contributed to investigation, formal analysis of climate data, and writing – review and editing; S.B. – the main contributor, contributed to validation, and writing – review and editing; A.S. – the main contributor, contributed to formal analysis of growth and yield data, and writing – review and editing; E.N., the main contributor, contributed to validation, and writing – review and editing; Y.H. – the main contributor, contributed to investigation, formal analysis of soil microbial data, and writing – review and editing; A.S. – the main contributor, contributed to methodology, and writing – review and editing; V.E.A. – the main contributor, contributed to conceptualization, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. All authors have read the manuscript and accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript to be published.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Rahmasary AN, Fawzi NI, Qurani IZ. Suboptimal land series: an introduction to sustainable agriculture practice on suboptimal land. TJF Brief; 2020. https://tayjuhanafoundation.org/resources/.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Aristya VE, Samijan. Rice breeding breakthrough for rainfed fields. Rainfed Rice Field Management, Technology, and Institutional. Surakarta: UNS Press; 2021. p. 245–65.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] BPS Provinsi Jawa Tengah. Jawa Tengah Dalam Angka; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Minardi. Optimalisasi pengelolaan lahan kering untuk pengembangan pertanian tanaman pangan. Naskah pidato pengukuhan Guru Besar Bidang Ilmu Tanah (Pengelolaan Tanah) Fakultas Pertanian, Universitas Sebelas Maret; 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Rejekiningrum P, Apriyana Y, Estiningtyas W, Sosiawan H, Susilawati HL, Hervani A, et al. Optimizing water management in drylands to increase crop productivity and anticipate climate change in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2022;14(11672):1–24. 10.3390/su141811672.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Lone BA, Nazir A, Fayaz A, Hassan B, Abidi I. Constrain and remedial measures in dryland agriculture. Frontiers in Crop Improv. 2022;9:2054–60.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Nurlaily R, Samijan, Aristya VE, Lestari F. Effect of biofertilizer application on the population of nitrogen-fixing bacteria and yields of chili pepper at Temanggung, Central Java. Proceeding of the International Workshop and Seminar Innovation of Environmental-Friendly Agricultural Technology Supporting Sustainable Food Self-Sufficiency; 2019. p. 346–54. 10.5281/zenodo.3345272.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Vejan P, Abdullah R, Khadiran T, Ismail S, Boyce AS. Role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in agricultural sustainability—a review. Molecules. 2016;21(573):1–17. 10.3390/molecules21050573.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Fitriatin BN, Dewi VF, Yuniarti A. The impact of biofertilizers and NPK fertilizers on soil phosphorus availability and upland rice yield in a tropic dry land. E3S Web of Conf. 2021;232. 10.1051/e3sconf/202123203012.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Herawati A, Syamsiyah J, Mujiyo, Rochmadtulloh M, Susila AA, Romadhon MR. Mycorrhizae and a soil ameliorant on improving the characteristics of sandy soil. Sains Tanah. 2021;12(2):73–80. 10.20961/STJSSA.V18I1.43697.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Haryati U. Application of mulch and soil ameliorant for increasing soil productivity and its financial analysis on shallots farming in the upland. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Envi. Sci. Vol. 648. Issue 1; 2021. 10.1088/1755-1315/648/1/012155.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Zuo Y, Zhang F. Soil and crop management strategies to prevent iron deficiency in crops. Plant Soil. 2011;339(1–2):83–95. 10.1007/s11104-010-0566-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Balittanah. Produk pupuk hayati, pupuk organik dan pupuk hayati. Balai Penelitian Tanah, Balai Besar Litbang Sumberdaya Lahan Pertanian; 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Mng’ong’o M, Munishi KL, Blake W, Comber S, Hutchinson TH, Ndakidemi PA. Soil fertility and land sustainability in Usangu Basin-Tanzania. Heliyon. 2021;7(8):e07745. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07745.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Madhaiyan M. Growth promotion and induction of systemic resistance in rice cultivar Co-47 (Oryza sativa L.) by Methylobacterium spp. Bot Bull Acad Sin. 2004;45(4):315–24. 10.7016/BBAS.200410.0315.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Ardonav P, Sessitsch A, Haggman H, Kozyrovska N, Pirttila AM. Methylobacterium-induced endophyte community changes correspond with the protection of plants against pathogen attack. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46802. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046802.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Marlina N, Gofar N, Subakti AHPK, Rahim AM. Improvement of rice growth and productivity through balance application of inorganic fertilizer and biofertilizer in inceptisol soil of lowland swamp area. Agrivita. 2014;36(1):48–56. 10.17503/agrivita-2014-36-1-p048-056.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Dobo B. Effect of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) and Rhizobium inoculation on growth and yield of Glycine max l. varieties. Int J Agron. 2022;2022:1–10. 10.1155/2022/9520091.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] García-López AM, Delgado A. Effect of Bacillus subtilis on phosphorus uptake by cucumber as affected by iron oxides and the solubility of the phosphorus source. Agric Food Sci. 2016;25(3):216–24. 10.23986/afsci.56862.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] POWER Data Access Viewer. Prediction of worldwide energy resource-agro climatology location of latitude -8.0972 longitude 110.8008; 2021. https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] IPNI Profit analysis based on fertilizer application. International Plant Nutrition Institute. Singapore: ESEAP Program; 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Gupta PC, O’Toole JC. Upland Rice - A Global Perspective. Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 1986.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Distan Wonogiri. Laporan tahunan Dinas Pertanian dan Kehutanan Kabupaten Wonogiri; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Vandani Y, Kusmiyarti TB, Susila KD. Pengaruh paket pupuk organik, anorganik dan pupuk hayati terhadap sifat tanah dan hasil tanaman kangkung darat (Ipomea reptana Poir) pada tanah vertisol. Agrotrop J Agric Sci. 2020;10(2):153–64. 10.24843/ajoas.2020.v10.i02.p05.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Rose MT, Phuong TL, Nhan DK, Cong PT, Hien NT, Kennedy IR. Up to 52% N fertilizer replaced by biofertilizer in lowland rice via farmer participatory research. Agron Sustain Dev. 2014;34(4):857–68. 10.1007/s13593-014-0210-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Schütz L, Gattinger A, Meier M, Müller A, Boller T, Mäder P, et al. Improving crop yield and nutrient use efficiency via biofertilization-a global meta-analysis. Front Plant Sci. 2018;8:2204. 10.3389/fpls.2017.02204.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Jabal ZK, Khayyun TS, Alwan IA. Impact of climate change on crop productivity using MODIS-NDVI Time Series. Civ Eng J. 2022;8(6):1136–56. 10.28991/CEJ-2022-08-06-04.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Javoreková S, Maková J, Medo J, Kovácsová S, Charousová I, Horák J. Effect of bio-fertilizers application on microbial diversity and physiological profiling of microorganisms in arable soil. Eurasian J Soil Sci. 2015;4(1):54–61. 10.18393/ejss.07093.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Masso C, Ochieng J, Awuor O. Worldwide contrast in the application of bio-fertilizers for sustainable agriculture: lessons for Sub-Saharan. Africa J Biol Agric Healthc. 2015;5(12):34–50. https://core.ac.uk/reader/234661445.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Rahmianna AA, Pratiwi H, Harnowo D. Budidaya Kacang Tanah Monogr Balitkabi no. 13; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Badawi FSF, Biomy AMM, Desoky AH. Peanut plant growth and yield as influenced by co-inoculation with Bradyrhizobium and some rhizome microorganisms under sandy loam soil conditions. Ann Agric Sci. 2011;56(1):17–25. 10.1016/j.aoas.2011.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Neelipally RTKR, Anoruo AO, Nelson S. Effect of co-inoculation of Bradyrhizobium and Trichoderma on growth, development, and yield of Arachis hypogaea L. (Peanut). Agronomy. 2020;10(9):1–12. 10.3390/agronomy10091415.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Htwe AZ, Moh SM, Soe KM, Moe K, Yamakawa T. Effects of biofertilizer produced from Bradyrhizobium and Streptomyces griseoflavus on plant growth, nodulation, nitrogen fixation, nutrient uptake, and seed yield of mung bean, cowpea, and soybean. Agronomy. 2019;9(2):77. 10.3390/agronomy9020077.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Htwe AZ, Moh SM, Moe K, Yamakawa T. Biofertilizer production for agronomic application and evaluation of its symbiotic effectiveness in soybeans. Agronomy. 2019;9(4):1–16. 10.3390/agronomy9040162.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Santana-Fernández A, Beovides-García Y, Simó-González JE, Pérez-Peñaranda MC, López-Torres J, Rayas-Cabrera A, et al. Effect of a Pseudomonas fluorescens-based biofertilizer on sweet potato yield components. Asian J Appl Sci. 2021;9(2):105–13. 10.24203/ajas.v9i2.6607.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Rajak ARA. Emerging technological methods for effective farming by cloud computing and IoT. Emerg Sci J. 2022;6(5):1017–31. 10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-05-07.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Sharma B, Yadav L, Pandey M, Shrestha J. Application of biofertilizers in crop production: A review. Peruvian J Agronomy. 2020;6(1):13–31. 10.21704/pja.v6i1.1864.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Aristya VE, Trisyono YA, Mulyo JH. Participatory varietal selection for promising rice lines. Sustainability. 2021;13:6856. 10.3390/su13126856.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Aristya VE, Taryono, Wulandari RA. Genetic variability, standardized multiple linear regression, and principal component analysis to determine some important sesame yield components. Agrivita. 2017;39(1):83–90. 10.17503/agrivita.v39i1.843.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Līcīte L, Popluga D, Rivža P, Lazdiņš A, Meļņiks R. Nutrient-rich organic soil management patterns in light of climate change policy. Civil Eng J. 2022;8(10):2290–304. 10.28991/CEJ-2022-08-10-017.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Jumakir Endrizal, Abdullah T. The response of biofertilizer on improving soybean productivity in tidal swamps land. J Pangan. 2021;30(1):23–30.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Supriyo A, Minarsih S, Prayudi B. Efectivitas pemberian pupuk hayati terhadap pertumbuhan dan hasil padi gogo di lahan kering. J Agritech. 2014;16(1):1–12.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Usman Pato U, Ayu DF, Riftyan E, Restuhadi F, Pawenang WT, Firdaus R, et al. Cellulose microfiber encapsulated probiotic: viability, acid and bile tolerance during storage at different temperatures. Emerg Sci J. 2022;6(1):106–17. 10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-01-08.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer