Abstract

Farmers are accessing seeds from different sources with different quality standards. Studies on the assessment of seed systems (sources) in relation to seed quality are scarce. This study was carried out to assess the different seed qualities (physical purity, physiological quality, and seed health) of bread wheat seed accessed through the existing seed sources (formal and informal seed sources) in Baso Liben district of the Amhara region, northwest Ethiopia. In addition, this study assessed the experience of farmers in seed production and management. Data were collected from 108 respondents using a semi-structured questionnaire and from farmers and local experts using focus group discussions. Seed samples were collected from 58 farmers (30 farmers who sourced seed from the informal system and 28 from the formal system) for laboratory testing. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and t-test (pairwise comparison) using SPSS v23.0. Results showed that about 32.4% of the respondents have experience in quality bread wheat seed production under contractual seed production arrangements with public seed enterprises. Results also revealed significant differences between formal and informal seed sources for various seed quality parameters. Seeds accessed from the formal sources have better physical purity, physiological quality, and 1,000 seed weight than seeds accessed from informal sources. Seed samples collected from the informal source were highly infected with Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium spp., and Fusarium spp., and seeds from the formal seed source were infected with Alternata spp. and Penicillium spp. Seed quality is a major concern for the seeds accessed from both formal and informal sources. Therefore, the seed quality control mechanisms of various stakeholders, including national and regional seed regulatory bodies, government organizations, research institutes, and seed producers/companies, should be given much attention at each stage of the seed value chain.

1 Introduction

Ethiopia is the main wheat (Triticum spp.)-producing country in sub-Saharan Africa, with an annual production of about 4.7 million tons from more than 1.7 million ha of land [1]. Wheat is also the fourth largest cereal crop produced by nearly 35% of smallholder farmers in Ethiopia, following tef (Eragrostis tef), maize (Zea mays), and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) [1,2]. Besides, it is one of the most important staple food crops in Ethiopia.

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the seven wheat spp. represented in Ethiopia. The productivity of wheat in Ethiopia is low, with a yield of 2.76 ton/ha [1]. Many production constraints are responsible for low productivity. One of the determinant factors is the scarcity of high-quality seed [3]. Crop productivity can be increased by using modern agricultural inputs, including seeds of improved varieties, fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation facilities, coupled with appropriate agronomic practices. Quality seeds are the most economical and efficient input to agricultural development [4]. Quality seeds can directly contribute up to 45% of the total production [5]. The contributions of all other production factors are highly dependent on the seed quality. The ultimate productivity of other inputs, which build the environments that enable the plant to perform well, is determined by seed quality. The use of seeds of improved varieties is crucial to the future of food security in Ethiopia as it could contribute to an increase in production and productivity.

Discussions of agriculture and rural economic development in Ethiopia inevitably lead to the subject of good-quality seeds [4,6]. The quality of seeds encompasses genetic purity, physical purity, germination rate, seed vigor, and seed health [7,8]. Through a combination of modern science and modest changes in farmers’ cultivation practices, quality seed could result in a remarkably abundant yield for small-scale farmers in Ethiopia, which could potentially increase production in the agricultural sector [9,10]. Thus, it contributes to food security and poverty reduction in the country [6,11].

Despite the importance of high-quality seeds in increasing crop productivity, their availability in sufficient quantities and at the right time remains a challenge in Ethiopia [12]. The limited availability of certified seeds of improved varieties at the right place and time, coupled with poor promotion strategies, has contributed to low agricultural productivity [13]. Farmers are accessing seeds from different sources with different quality standards [14]. For example, they access the seeds through different seed systems, including formal, informal, and intermediate seed systems [6,15,16]. Most of the previous studies focused on the various seed sources, how farmers access seeds, and the mechanisms by which these seed systems address the needs of farmers [17]. Studies assessing the seed systems (sources) in relation to the seed quality are scarce [18]. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the quality of seeds that are supplied through different seed sources and to understand the constraints that inhibit farmers from using certified seeds of improved varieties. This study is designed to fill this research gap. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to assess the experience of farmers in seed production and management and to assess the different seed quality parameters in relation to the existing bread wheat seed sources in northwest Ethiopia.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data collection

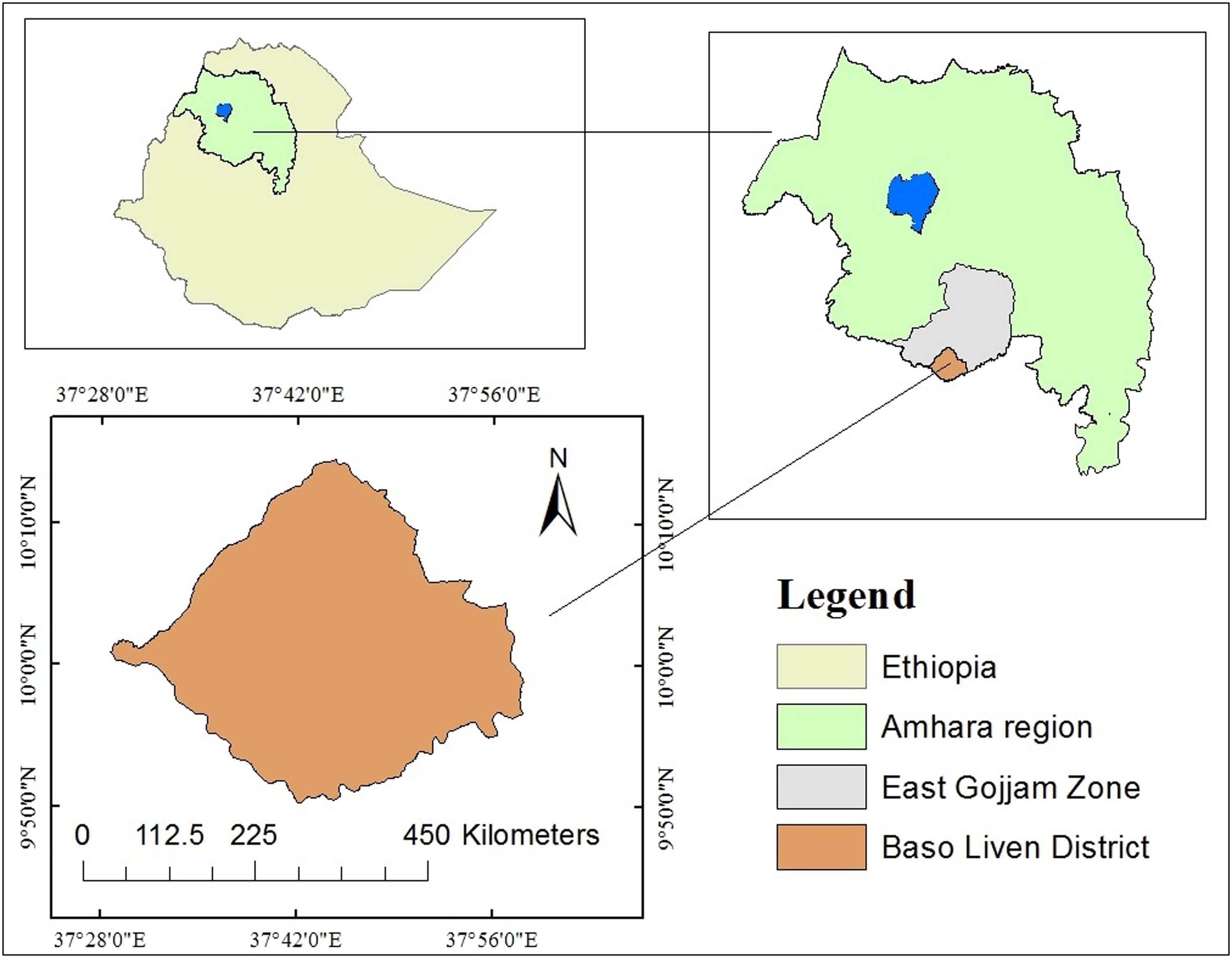

This study was conducted in Baso Liben district, Amhara region, Ethiopia, during the 2017/18 main cropping season (Figure 1). The data were collected in two steps. First, data were collected from sample farmers to understand farmers’ bread wheat seed production and management experiences. Multistage sampling procedures were used to select the sample villages (peasant associations) and individual respondents. Six villages were purposely selected based on their potential for wheat production and their representation in the district regarding production potential. A random sampling technique was used to select the respondents from the villages. A total of 108 farmers (92 males and 16 females) were interviewed. There were more males than females represented in this study. This is primarily due to the small number of female-headed households in the study area. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to gather the required information from respondents. Besides, two focus group discussions (FGDs) were carried out with local experts and farmers to collect further information. Second, data were gathered for laboratory tests on the seed samples collected from 58 farmers (48 males and 10 females). Of the 58 farmers, 30 accessed seeds from informal sources and 28 from formal sources. The seed samples were drawn from the seed lots prepared for the following planting season. About 400 g seeds was collected from each of the 58 farmers and immediately taken to the laboratory for seed quality analysis. The samples were subjected to testing for various seed quality parameters, including physical purity, physiological quality, and seed health. The analysis was conducted at the Bahir Dar and Debre Markos seed testing laboratories. The detailed procedures are described below.

Map of the study area.

Physical purity: The seeds collected from farmers were separated based on their sources. The samples collected from each farmer were reduced to a working sample of 120 g using a mechanical seed divider. The seed samples were thereafter purified, and the different components were separated (pure seed, other crop seed, weed seed, and inert matter). Each component was weighed using an analytical scale and analyzed based on the weight of each component, following the International Seed Testing Agency (ISTA) standard [19].

Thousand seed weight (TSW): TSW was determined by weighting 1,000 seeds from the pure seed component of each of the samples collected according to the ISTA standard [19].

Moisture content: Moisture content was determined using the oven-drying method. About 5 g seeds was taken from each sample, finely ground, and put in containers of less than 8 cm in diameter and covered by aluminum foil for pre-dry measurement. The samples were then dried in an oven adjusted at 130°C ± 1°C for 2 hours. At the end of 2 h, the containers were placed in desiccators to cool off for 30 min. Then, the containers were weighed with their covers and contents, and the moisture content was determined following the standard formula [19]:

where, M 1 is the weight of the container and its cover in grams; M 2 is the weight of the container, its cover, and its contents before drying in grams; and M 3 is the weight of the container, its cover, and its contents after drying in grams.

The physiological seed quality test is the vigor of the seed, which determines the germination and subsequent seedling emergence and crop establishment in the field as well as the storage potential of the seed lot.

Germination: A germination test was conducted according to the ISTA rules by taking 100 seeds from the pure seed components of each seed sample collected [8]. The seeds were planted on a sterilized sand substratum and placed at room temperature using light transparent germination dish for 8 days. On the eighth day, the germinated seeds were categorized into normal and abnormal seedlings, while ungerminated seeds were classified as dead seeds as specified by Fairey and Hampton [20]. The percentage of each component was calculated following the ISTA procedures [19]:

Seedling shoot and root lengths: Seedling shoot length and seedling root length were assessed after the final count in the standard germination tests. Ten normal seedlings were randomly selected from each of the samples. The shoot length was measured from the point of attachment to the cotyledon to the tip of the seedling, while the root length was measured (i.e., in cm) from the point of attachment to the cotyledon to the tip of the root. The average shoot or root length was calculated by dividing the total shoot length or root length by the total number of normal seedlings measured [21].

Seedling dry weight: Seedling dry weight was measured after the final count in the standard germination test. Ten seedlings were randomly selected from each sample, cut free from their cotyledons, placed in the envelopes, and dried in an oven at 80 ± 1°C for 24 h. The dried seedlings were weighed in grams, and the average seedling dry weight was calculated [22].

Vigor index: For each of the two seed sources (formal and informal), two vigor indices (VIG1 and VIG2) were calculated. VIG1 was calculated by multiplying the standard germination percentage with the average sum of seedling shoot and root lengths at the final day of the germination test, and VIG2 was calculated by multiplying the standard germination percentage with the mean seedling dry weight [22].

VIG1 = (G%) × (L), where G% is the standard germination percentage and L is the seedling length in (cm).

VIG2 = (G%) × (DW), where G% is the standard germination percentage and DW is the seedling dry weight in (g).

Speed of germination: The standard germination tests only distinguish between normal and abnormal seedlings. However, variation in seedling size and vigor is likely to occur within the category of “normal seedling.” To distinguish the variation among normal seedlings, the speed of germination was measured by taking 100 seeds from each sample and planting them independently on a germination paper. The seeds were kept at room temperature until no further germination took place. Starting from the fourth day up to the eighth day of planting, normal seedlings were counted and removed each day, and the speed of germination was calculated by dividing the number of normal seedlings counted each day by the number of days during which they were counted [23].

where n is the number of normal seedlings counted each day and Dn is the number of days during which seedlings were counted.

Seed health: Seed samples were tested to check for the presence of seed-borne pathogens associated with bread wheat seed sources. Identification of different seed-borne pathogens was conducted by the agar plate method using potato dextrose agar according to the ISTA standard [24]. The seeds were washed with tap water, surface-sterilized by soaking them in 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 2 minutes, and then washed in distilled water. Twenty-five seeds from each sample were planted at equal distance on the Petri dishes and incubated at 25°C for 8 days with an agar plate that had an alternating light and dark period of 12 h near ultraviolet light. At the end of the incubation period, slides were prepared, and colonies of fungi were identified based on the morphological characteristics of the pathogens (colony characteristics, shape, and septation of conidia) in comparison with appropriate reference materials (laboratory manuals, colored images, and literature). Finally, the percentage of infected seeds produced by fungi was recorded.

2.2 Data analysis

The data collected through individual interviews were analyzed using descriptive statistics, such as minimum, maximum, and percentage values. For laboratory analysis, the samples were divided into two groups, representing the formal and informal sources. The percentage of seed quality parameters related to physical quality, physiological quality, and seed health was computed using a t-test (pairwise comparison) between formal and informal sources. SPSS v23.0 was used to analyze the collected data.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Farmers’ experience in bread wheat seed production

About 32.4% of the respondents have experience in quality bread wheat seed production. The remaining 67.6% of the respondents said that they do not have experience in bread wheat seed production. The experience of farmers is mainly based on contractual seed production schemes with public seed enterprises. In other words, their role is limited as outgrowers for enterprises. They have 1 to 3 years (on average, 2 years) of experience in such seed production arrangements.

A contractual seed production arrangement is usually based on cluster farmlands, in which farmers who have land in the selected cluster have a chance to participate in seed production. Farmers who do not have their own land in selected clusters cannot participate in seed production unless they rent land from other farmers within the cluster. During FGDs, participants said that contractual seed production started in the district a few years ago in some villages, and the coverage has increased to most of the villages of the district. As mentioned by the respondents, most farmers do want or are willing to participate in contractual seed production for several reasons, including market security (market guarantee) and access to certified seed of improved varieties from the contracting party to overcome the problem of seed shortage (seed security) [6]. This arrangement, as explained by local experts during FGDs, is a legally binding agreement between the seed enterprise (contracting party) and the farmers (outgrowers). FGD participants said that the additional premium price motivates farmers to engage in contractual seed production, though they were not happy sometimes due to the presence of better alternative markets in the areas. However, compared with farmers engaging in contractual hybrid maize seed production, the premium price is not attractive.

3.2 Farmers’ practices of post-harvest seed management

The various farmers’ post-harvest seed management practices are presented in Table 1. All farmers use the manual or traditional threshing method on a cemented floor plastered with cow dung. About 77% of the farmers used the same threshing floors for all crops, while 19% prepared separate threshing floor for different varieties, and only 1% had experience preparing a new floor for each of the crops they threshed. Using the same floor for all crops or varieties during threshing could cause the mixing up of crops and varieties, which eventually leads to low purity.

Farmers’ post-harvest seed management experience

| Post-harvest seed management | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Threshing condition | ||

| Prepare new floor for each crop | 1 | 0.9 |

| Use the same floor for all crops | 86 | 79.6 |

| Separate floor for different varieties | 21 | 19.4 |

| Seed treatment practice | ||

| Clean the seed manually using hand winnowing | 56 | 51.8 |

| Treat seed before planting with ash, cow dung, and malathion | 6 | 5.6 |

| Separate seed during threshing and keep for next cropping season | 46 | 42.6 |

| Seed storage structure | ||

| Traditional storage facilities “Gotera/gota” | 65 | 60.2 |

| Sack/bags | 43 | 39.8 |

Regarding farmers’ experiences with various seed management practices, nearly half (51.8%) of the respondents clean the seeds manually by hand winnowing (Table 1). In most parts of Ethiopia, seed cleaning is usually carried out before the commencement of sowing, as farmers traditionally stored seeds until planting time. About 42.6% of the respondents explained their experience in separating the seed during threshing and storing the cleaned seeds in advance for the following cropping season. Only 5.6% of respondents practiced seed treatment before planting, particularly using cow dung, ash, and malathion, and then stored the seeds in separate bags to protect the seeds from insects such as weevils. In some wheat-producing areas of Ethiopia, farmers do have experience treating the seeds with chemicals to protect them from insect infestation [25]. Regarding storage structure, 60% of the respondents used traditional storage structure, namely “Gotera or Gota,” which is found to be the most common storage structure in Ethiopia. Farmers usually plaster the “Gotera or Gota” with cow dung to prevent storage pests from attacking the stored seeds. About 39.8% of the respondents used sacks for storing seeds. Although “Gotera or Gota” is the common storage structure for most farmers in Ethiopia, as cited by the FGDs’ participants, there is a shift toward replacing it with sacks and other modern storage structures. Farmers used local seed management practices, such as seed selection, cleaning, treatment, and better storage facilities, to maintain the seed quality [18].

3.3 Farmers’ perceptions about seed quality

The perception of the respondents toward their understanding of seed quality is displayed in Figure 2. Interviewed farmers were asked to mention the most important criterion for determining quality seeds, though farmers have various insights toward seed quality. Most of the respondents (61%) perceived that quality seeds should be free from weeds as an important criterion, whereas about 23% of the respondents believed that quality seeds must be free from any deformities (shriveled). The remaining 13 and 3% of the respondents pointed out that quality seeds should be free from diseases and insect damage and have good uniformity in the field. Most farmers consider physical purity to be an important characteristic of quality seed. The possible reason may be that the seed, which is physically pure, has a good physical appearance in the field and may attract the attention of farmers. This may not necessarily be the only important perception to be considered. There are other attributes such as being free from diseases or insect damage (seed health) and having uniformity in the field (genetic quality), as was explained by experts during FGDs. These attributes mainly determine the germination, establishment, and true-to-type of a given variety. Physical purity, uniformity, and freedom from insects, diseases, and weeds are the most important seed quality-measuring parameters perceived by farmers in the previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [26,27].

Farmers’ perception on quality seed criteria.

3.4 Physical quality

The differences between the seed accessed through formal and informal seed sources regarding the various physical quality parameters are presented in Table 2. Highly significant (P = 0.000) differences were observed between formal and informal seed sources for pure seed, other crop seed, weed seed, and inert materials. The mean percentages of pure seed were 98 and 94.3% for the seed obtained through formal and informal seed sources, respectively. Earlier studies show that certified seed of improved wheat varieties from the formal sector had the highest analytical purity but was not significantly different from other seed sources [18]. Participants during FGDs explained that seeds collected from informal seed sources are usually subject to seed mixtures due to poor handling mechanisms and other abiotic factors.

Comparison of wheat physical purity attributes between formal and informal seed sources

| Variable | Seed systems | Two-sample t-test results | Effect size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FORM (n = 28) Mean (SD) | INFORM (n = 30) Mean (SD) | t (df = 56) | P value | ||

| Seed purity (%) | 98.0(0.32) | 94.3(0.65) | 27.084 | 0.000 | 3.70 |

| Other crops seed (%) | 0.00(0.00) | 1.03(0.45) | −12.010 | 0.000 | 1.03 |

| Weed seed (%) | 0.00(0.00) | 0.23(3.00) | −12.438 | 0.000 | 0.23 |

| Inert materials (%) | 2.00(0.32) | 4.40(0.49) | −4.087 | 0.000 | 2.40 |

| TSW (g) | 38.55(0.73) | 36.56(0.81) | −21.917 | 0.000 | 1.99 |

| Moisture content (%) | 12.74(0.40) | 12.24(0.63) | 9.843 | 0.001 | 0.5 |

n – number of farmers. FORM – formal; INFORM – informal.

The presence of weed seeds and other crop seeds was not observed in the samples accessed from the formal seed source, indicating good care during seed production in the field, processing, storage, and transportation. On the other hand, weed seeds and other crop seeds were observed in 43 and 90%, respectively, of the samples accessed from the informal seed sources. Previous studies found significant differences in the purity of bread wheat seed samples collected from different sources in Ethiopia [28]. This might be attributed to the different ways that farmers used to produce, select, save, and acquire wheat seeds. Poor-quality seeds have a significant impact on market value [30].

3.5 TSW

There was a highly significant (P = 0.000) difference between the formal and informal seed sources for TSW (Table 2). The mean percentages of TSW were 38.55 and 36.56 g for samples collected from the formal and informal seed sources, respectively. Seed with a higher TSW has better milling quality and ensures better emergence [30,31]. Previous studies in Ethiopia showed significant differences in TSW among wheat varieties collected from formal seed sources and farmers [32]. A grand mean TSW value of 35.34 g, with minimum (25.08 g) and maximum (49.87 g) values, has already been reported from wheat seed samples collected from different wheat-producing areas of Ethiopia [28].

3.6 Seed moisture content

The moisture content (MC) of seed samples collected from formal and informal seed sources differed significantly (P = 0.001) (Table 2). On average, 12.74% of the MC was recorded from formal sources and 12.24% from informal sources. The values obtained from the formal and informal seed sources were in the acceptable range of MC (13%) for the wheat seed quality specification set by ethiopian standards authority (ESA) [28]. The high MC could result from poor pre-harvest seed management practices and post-harvest handling during processing and particularly during storage conditions. It has been reported that changes in seed MC of common bean are associated with the management practice [33].

3.7 Standard germination

Table 3 presents the average values of germination percentage, abnormal seedlings, and dead seeds. Highly significant (P = 0.000) differences were observed between the two sources in the proportion of normal, abnormal seedlings, and dead seedlings. The mean percentages of germination (normal seedlings) were 90.07 and 82.13% for seed obtained from formal and informal seed sources, respectively. This indicates that the formal sources contain higher-quality seed than the informal sources. High-quality seed germinates earlier and thus produces larger roots and shoots than low-quality seed [34].

Comparison of standard germination variables between formal and informal seed sources

| Variable | Seed system | Two-sample t-test results | Effect size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FORM (n = 28) Mean (SD) | INFORM (n = 30) Mean (SD) | t (df = 56) | P value | ||

| Standard germination | |||||

| Normal seedlings (%) | 90.07(2.16) | 82.13(4.82) | 3.466 | 0.000 | 7.94 |

| Abnormal seedlings (%) | 7.39(1.62) | 11.47(2.62) | 7.996 | 0.000 | 4.08 |

| Dead seeds (%) | 2.53(1.62) | 6.40(3.11) | −7.059 | 0.000 | 3.87 |

n – number of farmers. FORM – formal; INFORM – informal.

In terms of abnormal seedlings, the highest mean percentage (11.47%) was recorded from informal sources and lowest (7.39%) from the formal sources. Similarly, the highest mean percentage (6.43%) of dead seed was recorded from an informal source, while the lowest mean (2.53%) was recorded from a formal source. These are important variables that greatly contribute to the germination capacity of a given seed [33].

3.8 Seedling vigor test

To assess the vigor of bread wheat seed collected from the two seed sources, physiological tests such as speed of germination, seedling shoot length, seedling root length, seedling dry weight, VIG1, and VIG2 were performed (Table 4). Highly significant (P = 0.000) differences were observed between the two groups for seedling shoot length, speed of germination, VIG1, and VIG2, and significant differences (P < 0.05) for seedling root length and seedling dry weight. The highest seedling dry weight (0.27 g) was observed on the seed samples collected from the formal seed sources.

Comparison of seed vigor tests between formal and informal seed sources

| Variable | Seed system | Two-sample t-test results | Effect size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FORM (n = 28) Mean (SD) | INFORM (n = 30) Mean (SD) | t (df = 56) | P value | ||

| Vigor test | |||||

| Seedling shoot length (cm) | 11.09(0.59) | 9.74(0.52) | −5.864 | 0.000 | 1.35 |

| Seedling root length (cm) | 13.03(0.79) | 12.59(0.62) | 9.279 | 0.017 | 0.44 |

| Seedling dry weight (g) | 0.27(0.53) | 0.24(0.52) | 2.459 | 0.044 | 0.03 |

| Speed of germination (%) | 18.96(0.61) | 16.64(1.12) | 2.062 | 0.000 | 2.32 |

| VIG1 (%) | 2174.41(105.69) | 1833.97(129.16) | 9.068 | 0.000 | 340.44 |

| VIG2 (%) | 24.96(4.63) | 20.38(4.61) | 10.940 | 0.000 | 4.58 |

n – number of farmers. FORM – formal; INFORM – informal; VIG1 – vigor index1; VIG2 – vigor index 2.

Speed of germination was conducted to distinguish the variation in seedling size and vigor within the category of “normal seedlings.” The presence of highly significant (P = 0.000) variation for speed of germination between the two groups indicates that the seed samples accessed from the formal seed sources have higher germination rates and more vigor than the seed samples obtained from the informal sources. This is supported by the fact that “speed of germination” is the rate at which the seed germinates, and seedlings with a higher index or higher on first count are expected to show faster germination and seedling emergence, as well as to escape adverse field conditions than seedlings with a lower index [28]. The samples collected from the informal seed sources have shown low vigor, which is in line with the findings of the previous studies [29]. Seed with a low germination rate can have a negative effect on the performance of the crop as it is apparent that the seed will not germinate properly [29]. Both VIG1 and VIG2 also showed a highly significant (P = 0.000) difference between the formal and informal seed sources. Similar results were reported from sorghum. The difference in physiological quality of sorghum seed from different sources may be attributed to differences in storage age and temperatures, seed moisture content in storage, and growers’ level of awareness of seed production and handling [35].

3.9 Phytosanitary test

The study identified the presence of seed-borne fungi pathogens in wheat seed samples collected from both formal and informal sources (Table 5). These include Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium spp. (Chaetomium funicola, Chaetomium globosum), Alternaria alternata, Penicillium spp. (Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium verrucosum), and Fusarium spp. (Fusarium culmorum, Fusarium graminearum). The differences between the formal and informal seed sources were significant for Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium spp. and Fusarium spp., and the differences were non-significant for Alternaria alternata and Penicillium spp. Seed samples collected from formal sources were highly affected by Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium spp., and Alternaria alternata, whereas seed samples collected from informal sources were highly affected by Penicillium and Fusarium. In terms of magnitude of effect, Aspergillus flavus has the highest effect, followed by Fusarium and Aspergillus niger. Previous studies identified different Fusarium spp. and several saprophytic fungi (Alternaria spp., Aspergillus spp., Cladosporium spp., Curvularia spp., Mucor spp., Nigrospora spp., Penicillium spp., and Trichothecium spp.) from wheat seed samples collected from farmers in the major bread wheat-growing areas of Ethiopia [36]. The higher incidence and association of fungal species with bread wheat seed samples agree with the results of recent studies on common bean and other grain crops [27]. For example, a study conducted on the quality assessment of common bean seed from formal and informal sources in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia indicated that Fusarium oxysporum and Aspergillus spp. were the two most common fungal diseases associated with seed retained by farmers from local markets and cooperative unions [37]. The presence of these important fungi species is primarily due to the management conditions in both seed sources. These conditions include the proper management of critical agronomic practices and post-harvest management such as seed drying mechanisms, threshing, and storage facilities.

Comparison of seed health quality attributes between formal and informal seed sources

| Variable | Seed system | Two-sample t-test results | Effect size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FORM (n = 28) Mean (SD) | INFORM (n = 30) Mean (SD) | t (df = 56) | P value | ||

| Seed health | |||||

| Aspergillus flavus (%) | 20(10.61) | 30.8(12.96) | −3.46 | 0.001 | 10.8 |

| Aspergillus niger (%) | 5(7.19) | 12.4(12.18) | −2.79 | 0.007 | 7.4 |

| Chaetomium spp. (%) | 4.71(5.11) | 8.80(5.29) | −2.99 | 0.004 | 4.09 |

| Alternata spp. (%) | 12.43(13.30) | 11.60 (10.20) | 0.267 | 0.790 | 0.83 |

| Penicillium spp. (%) | 5(7.02) | 4.77(7.28) | 0.177 | 0.860 | 0.33 |

| Fusarium spp. (%) | 8.14(6.66) | 15.73(15.07) | −2.48 | 0.017 | 7.59 |

n – number of farmers. FORM – formal; INFORM – informal.

4 Conclusion

This study showed that a large number of farmers in the study area have experience in quality bread wheat seed production through contractual seed production arrangements with public seed enterprises. This study confirms that there are significant differences between informal and formal seed sources for various seed quality parameters. Seed accessed from formal sources has better physical purity, physiological quality, and TSW than seed accessed from informal sources. For most of the wheat seed quality standards, the samples of seed collected from informal sources have not fulfilled the minimum standard requirements set by ESA. For moisture content, however, the samples obtained from the informal source have fulfilled the Ethiopian wheat seed quality standards.

This study also identifies the various seed-borne fungi pathogens found in bread wheat seed from both formal and informal seed sources. These are Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium spp., Alternata spp., Penicillium spp., and Fusarium spp. Seed collected from informal seed sources is highly affected by Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Chaetomium, and Fusarium. Seed collected from formal seed sources is highly affected by Alternata and Penicillium. Seed quality is a major concern for the seeds accessed from both the formal and informal mechanisms. Appropriate pest management mechanisms such as timely harvesting, proper drying, an appropriate threshing field, and good storage facilities should be in place to control seed-borne diseases in both the formal and informal seed sources. Moreover, seed quality control mechanisms from government entities and seed producers or companies should be given much attention at each stage of the seed value chain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the respondents for their participation and providing the information during individual interview and FGD.

-

Funding information: This research was financially supported by Ethiopian Ministry of Education as part of the MSc study of the first author.

-

Author contributions: YAY identified the research problem, involved in data collection and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. DTS identified the research problem, designed tools for data collection and analysis, and significant contribution in write-up of the manuscript. DA made a significant contribution in problem identification and write-up of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the first author on a reasonable request.

References

[1] CSA (Central Statistical Agency). Agricultural sample survey (2018/19). Report on area and production of major crops for private peasant holdings, Meher season. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Menna A, Semoka J, Amuri N, Mamo T. Wheat response to applied nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorous in three representative areas of the central highlands of Ethiopia. Int J Plant Soil Sci. 2015;8(5):1–11. 10.9734/IJPSS/2015/20055.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Hei N, Hussein SA, Laing M. Appraisal of farmers’ wheat production constraints and breeding priorities in in rust prone agro-ecologies of Ethiopia. Afr J Agric Res. 2017;12(12):944–52. 10.5897/AJAR2016.11518.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Alemu D. The political economy of Ethiopian cereal seed systems: state control, market liberalization and decentralization. Future Agricultures, Working Paper 017; 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Abebe G, Alemu A. Role of improved seeds towards improving livelihood and food security. Int J Res-Granthaalayah. 2017;5(2):338–56. 10.5281/zenodo.376076.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Sisay DT, Verhees FJHM, van Trijp HCM. Seed producer cooperatives in the Ethiopian seed sector and their role in seed supply improvement. J Crop Improv. 2017;31(3):323–55. 10.1080/15427528.2017.1303800.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). Seed in emergencies: a technical handbook-plant production and protection paper 202. FAO, Rome, Italy; 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] ISTA (International Seed Testing Association). International rules for seed testing 2004. Zürich, Switzerland; 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Eneyew A. Access to improved seeds and its effect on food security of poor farmers. Int J Dev Res. 2017;7(7):13655–63.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Gadisa A. Review on the effect of seed source and size on grain yield of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J Ecol Nat Resour. 2019;3(1):1–8. 10.23880/jenr-16000155.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Alemu D, Spielman DT. The Ethiopian seed system, regulations, institutions and stakeholders. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington D.C, USA and the Ethiopian Development Research Institute; 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Thijssen M, Bishaw Z, Beshir A, de Boef WS, editors. Farmers, seeds and varieties: supporting informal seed supply in Ethiopia. Wageningen, The Netherlands; 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Atilaw A, Korbu L. Recent development in seed systems of Ethiopia. In: Alemu D, Kiyoshi S, Kiurb A, editors. Improving Farmers’ access to seed empowering farmers’ innovation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: JICA; 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Louwaars NP, de Boef WS. Integrated seed sector development in Africa: A conceptual framework for creating coherence between practices, programs, and policies. J Crop Improv. 2012;26(1):39–59. 10.1080/15427528.2011.611277.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Hassena M, Dessalegn L. Assessment of Ethiopian seed sector. Integrated Seed Sector Development in Africa Workshop, Kampala, Uganda; 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Hirpa A, Meuwissen MPM, Tesfaye A, Lommen WJM, Oude Lansink AGJM, Tsegaye A, et al. Analysis of seed potato systems in Ethiopia. Am J Potato Re. 2010;87:537–52. 10.13140/RG.2.1.4337.8408.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Bishaw Z, Alemu D. Farmers’ perception of improved bread wheat varieties and formal seed supply in Ethiopia. Int J Plant Prod. 2017;11(1):117–30.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Bishaw Z, Struik P, van Gastel AJG. Farmers’ seed sources and seed quality: 1. physical and physiological quality. J Crop Improv. 2012;26:655–92. 10.1080/15427528.2012.670695.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] ISTA (International Seed Testing Association). International rules for seed testing 1996. Zürich, Switzerland; 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Fairey DT, Hampton JG. Forage seed production, Volume 1: Temperate Species. London, UK: CABI Publishing; 1998.10.1079/9780851991900.0000Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Khare JW, Bhale RD. Seed science and technology. New Delhi, Bombay: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co.; 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Fiala F. Hand book of vigor test methods. USA: ISTA Publications; 1987.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Maguire J. Speed of germination, an aid in selection and evaluation for seedling emergence and vigor. Crop Sci. 1962;2:176–7. 10.2135/cropsci1962.0011183X000200020033x.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] ISTA (International Seed Testing Association). International rules for seed testing 1993. Zürich, Switzerland; 1993.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Gemeda A, Aboma G, Hugo V, Wilfred M. Farmers’ maize seed systems in Western Oromia, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and Ethiopian Agricultural Research Organization (EARO); 2001.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Gemechu B. Formal and informal seed systems of maize in Eastern Wollega. MSc Thesis. Ethiopia: Haramaya University; 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Oshone K, Gebeyehu S, Kesfaye T. Assessment of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) seed quality produced under different cropping systems by smallholder farmers in Eastern Ethiopia. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2014;14(1):8567–84.10.18697/ajfand.61.13170Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Bishaw Z. Wheat and barley seed systems in Ethiopia and Syria. PhD Thesis. The Netherlands: Wageningen University; 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Nicholas M, Melinda S, Carl E, Thomas J, Jennifer K, Daniela H, et al. Seed development programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of experiences. Washington, DC, USA: Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division; 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Cordazzo CV. Effect of seed mass on germination and growth in three dominant species in Southern Brazilian Coastal Dunes. Braz J Biol. 2002;62(3):427–35.10.1590/S1519-69842002000300005Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Dariusz D, Laskowski J. Wheat kernel physical properties and milling process. Acta Agroph. 2005;6(1):59–71.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Ensermu E, Mwangi W, Verkuijl H, Hassena M, Alemayehu Z. Farmers’ wheat seed sources and seed management in Chilalo Awraja, Ethiopia. CIMMYT, Mexico and IAR, Ethiopia; 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Nahar K, Ali MH, Ruhul Amin AKM, Hasanuzzaman M. Moisture content and germination of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under different storage conditions. Acad J Plant Sci. 2009;2(4):237–41.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] McGrath JM, Derrico CA, Morales M, Copeland LO, Christertenson DR. Germination of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L) seed submerged in hydrogen peroxide and water as a means to discriminate cultivar and seed lot vigor. Seed Sci Technol. 2000;28:607–20.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Ochieng LA, Mathenge PW, Muasya R. An assessment of the physiological quality of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L moench) seeds planted by farmers in Bomet district of Kenya. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2012;12(5):6385–96.10.18697/ajfand.53.10215Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Bishaw Z, Sahilu Y, Simane B. The status of the Ethiopian seed industry. In: Thijssen MH, Bishaw Z, Beshir A, de Boef WS, editors. Farmers seed and varieties: supporting informal seed supply in Ethiopia. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Wageningen International; 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Wakessa T. Assessment of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) seed quality of different seed sources in central rift valley, Ethiopia. MSc Thesis. Ethiopia: Haramaya University; 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer