Abstract

The inherent brittleness and high ductile-to-brittle transition temperature of tungsten-based heavy alloys are primarily due to the poor cohesion of W grain boundaries and insufficient bonding strength at the W/γ phase interface, which limits their reliability and service life in related applications. This study prepared nano-size La2O3 and HfC particles reinforced W–(Fe, Co, Ni) alloys via microwave sintering, including the baseline sample S-A (95.5W–2.63Fe–1.12Co–0.75Ni, in wt%), single addition samples S-B (1La2O3), S-C (1HfC), and mix addition sample S-D (1La2O3–1HfC). The results show that S-C has the highest relative density of 99.2 ± 0.47 %; S-D has the highest Vickers hardness of 414 ± 13.5 HV and tensile strength of 744.1 MPa; S-B has the optimal strain of 5.1 %. La2O3 enhances the plasticity and fracture strain of the composites by grain boundary purification, grain refinement, and interface strengthening, inducing a transgranular fracture mode. HfC promotes the formation of composite carbides, achieving dispersion strengthening and dislocation pinning, primarily enhancing hardness and strength, but with limited improvement in toughness. In S-D, the synergistic effect of La2O3 and HfC effectively balances the grain boundary pinning and purification, minimizes microporosity, and optimizes phase interface bonding, thus achieving an excellent synergy between strength and toughness, extending the alloy’s application potential in extreme environments.

1 Introduction

Tungsten-based heavy alloys (WHAs) are a series of alloys with tungsten (content between 88 and 99 wt%) and small amounts of elements such as Fe, Co, Ni, etc., with a density of 16.5–19.0 g/cm3. It is a typical dual-phase alloy, mainly composed of the BCC structured W phase and the FCC structured γ phase (such as Ni–Fe) [1], 2]. It has many excellent properties, including high density, high strength and hardness, low thermal expansion coefficient, good electrical and thermal conductivity, strong radiation absorption capacity, oxidation resistance, and corrosion resistance [3], 4], and is widely used in rocket engine nozzles, turbines, combustion chambers, nuclear reactors, and kinetic energy penetrators [5], [6], [7]. However, the room temperature embrittlement and high ductile-to-brittle transition temperature of WHAs limit their reliability and service life [8].

The main cause of the above issues is the poor cohesion of W grain boundaries, and the interface bonding strength between the γ phase and W phase is often insufficient, making it prone to becoming a source of crack initiation and propagation under stress [9]. Currently, studies have reported that second-phase particles can alleviate the poor cohesion of W grain boundaries by refining grain size and introducing abundant grain boundary regions [10]. Common second-phase particles include La2O3 [11], Y2O3 [12], ZrO2 [13], Al2O3 [14], HfC [15], ZrC [16], etc. These dispersed particles primarily function through the following mechanisms. Firstly, second-phase particles can pin grain boundaries, effectively preventing grain coarsening during sintering and subsequent service, thereby increasing the material’s strength and hardness through the Hall–Petch effect [17]. Secondly, rare earth oxides (such as La2O3), in particular, tend to segregate at grain boundaries, not only purifying the grain boundaries (adsorbing impurities and improving boundary purity) but also enhancing the bonding strength between W–W grain boundaries and W/γ phase interfaces. They can effectively hinder grain boundary sliding and crack propagation along the grains, thus improving toughness and reducing the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature [10], 11]. Thirdly, hard particles such as carbides (HfC, ZrC) can effectively hinder dislocation motion and carry load during deformation, significantly enhancing the material’s strength at both room temperature and high temperatures [15], 16]. The interdiffusion of the Hf and W atoms during sintering produced a mixed carbide, which helps in developing a good interface joint with the adjacent W matrix [3], 5].

It has been proved that the heating mode has a significant impact on the microstructure and mechanical properties of tungsten alloys. Compared to the traditional sintering process, microwave sintering is an advanced technology capable of achieving rapid and relatively uniform sintering. The core advantage of microwave sintering lies in the direct interaction of microwave energy with individual particles inside the pressed compact, significantly improving heating efficiency and achieving bulk heating effects [18]. Microwave sintering can effectively suppress the coarsening of tungsten grains, resulting in a finer grain structure. In addition, due to the extremely fast heating rate of microwave sintering, the formation of intermediate metal compounds during the sintering process is avoided [19], thereby improving the consistency of the material’s performance. This efficient sintering mechanism provides a new approach for the preparation of high-performance tungsten alloys and other refractory materials.

In summary, this study uses microwave sintering technology to prepare WHAs with nano-size La2O3, HfC, and La2O3–HfC mixture as secondary reinforcing phases, aiming to comprehensively utilize rare earth oxides to purify grain boundaries, improve interface bonding, and the synergistic effect with refractory carbides to pin grain boundaries and bear loads, optimizing the mechanical properties of traditional WHAs. Through systematic microstructural characterization and mechanical performance testing, the effects of different reinforcing phases on the alloy’s microstructure evolution, grain boundary state, and interface characteristics were analyzed, and the relationship between these factors and the mechanical properties such as density, hardness, strength, and ductility were explored. This study aims to reveal the microscopic mechanism of synergistic enhancement by multiple second phases and provide new insights and experimental basis for the design of high-performance WHAs.

2 Experimental

2.1 Composites preparation

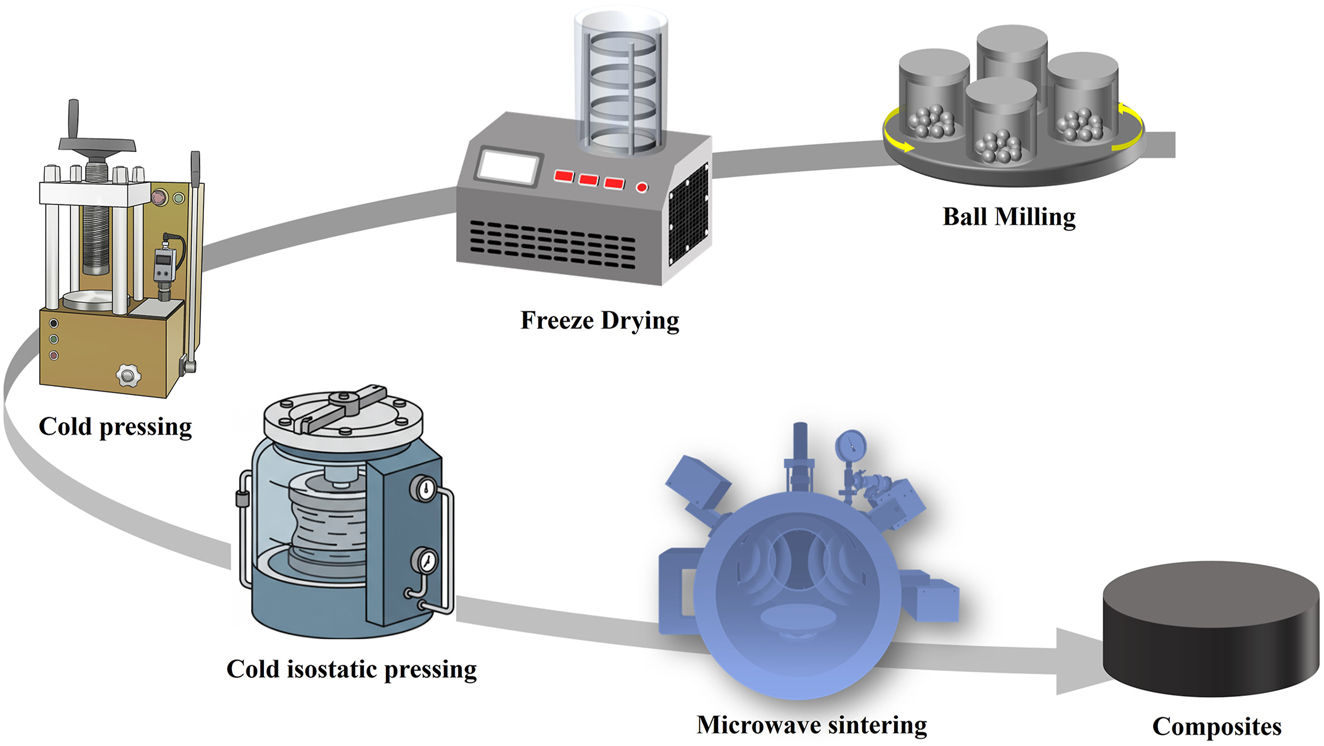

This study uses commercial powders as raw materials, with the ratio of γ bonding phase Fe, Co, and Ni kept constant at 7:3:2 in all samples. Four alloy compositions were designed, and the sample names and mass fractions are listed in Table 1. The corresponding powders were mixed via ball milling according to the composition ratio, using tungsten carbide milling balls, with a ball-to-powder ratio of 10:1, a speed of 300 r/min, and a ball milling time of 6 h. Anhydrous ethanol was added as a process control agent during ball milling to suppress powder cold welding, prevent agglomeration, and control the milling temperature from becoming too high. To further increase the material’s density, this study employs a combination of extrusion and cold isostatic pressing to consolidate the powders. The freeze-dried composite powders were first held under a 250 MPa uniaxial pressure for 5 min to produce green bodies with certain strength and density. The green bodies were then densified using cold isostatic pressing technology to further enhance their density, this process was carried out through staged pressurization: In the first stage, a pressure of 100 MPa is maintained for 1 min, then it is increased to 200 MPa and hold in 1 min, and the third stage hold a 290 MPa pressure for 1 min. After that, reverse the process and reduce the pressure in the opposite order of the previous three stages. Finally, the green bodies were placed in a fiber cotton insulated container and sintered in a microwave sintering furnace under vacuum: The temperature was first increased to 1,400 °C at a rate of 40 °C/min, then raised to 1,470 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, held for 30 min, and then cooled to room temperature with the furnace. The composite material was ultimately obtained. The preparation process is shown in Figure 1.

Composition of tungsten-based composite materials.

| Samples | W (wt%) | Fe (wt%) | Co (wt%) | Ni (wt%) | La2O3 (wt%) | HfC (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-A | 95.5 | 2.63 | 1.12 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 |

| S-B | 95.5 | 2.04 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 1 | 0 |

| S-C | 95.5 | 2.04 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 0 | 1 |

| S-D | 95.5 | 1.45 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 1 | 1 |

Schematic diagram of the preparation process of WHA composites.

2.2 Characterization and test

Optical microscopy (OM) was used to observe the metallographic structure of the alloy and determine the preliminary morphology of the tungsten-based composite material. The phase composition and microstructure of the tungsten-based composite material were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, ZEISS Sigma 300). The overall density of the tungsten-based composite material was measured using the Archimedes drainage method. Microhardness was measured using the HXD-100TM/LCD microhardness tester, with a fixed load of 10 kg and a holding time of 15 s. The mechanical properties were measured using the MTS E45.105 universal testing machine, with a loading rate of 0.00025 mm/s. The test specimens have a gauge length of 25 mm with the corresponding strain rate of 1 × 10−5 s−1, which represents a typical lower limit of the quasi-static range. Finally, SEM was used to analyze the tensile fracture surface of the material to determine its fracture mode. Three repeated tests were conducted for each measurement to obtain the average and standard deviation, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of the data.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phase analysis

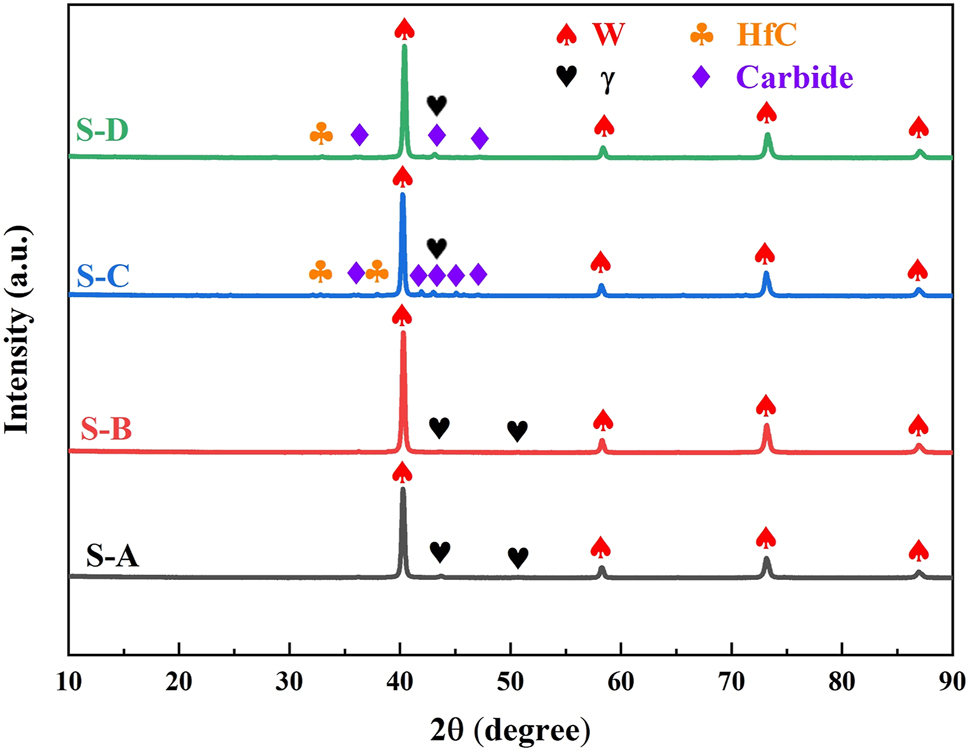

The XRD spectrum shown in Figure 2 indicates that the WHAs are composed of a BCC-W matrix and an FCC-γ bonding phase. After the addition of La2O3 alone, its characteristic peaks were not observed in the spectrum, possibly due to insufficient diffraction effects preventing the La2O3 peaks from appearing [20]. When HfC was added alone, clear diffraction peaks for HfC and W-rich carbides appeared in the spectrum, indicating that the HfC particles are relatively large and well-crystallized, capable of pinning grain boundaries and refining the structure. When La2O3 and HfC were introduced in combination, the intensity of the HfC diffraction peaks are weakened and La2O3 was still not detected due to insufficient diffraction effects, indicating that the rare earth elements suppressed carbide growth during sintering, causing the particle size to decrease further or partially dissolve into the matrix.

XRD images of WHA composites.

3.2 Microstructure analysis

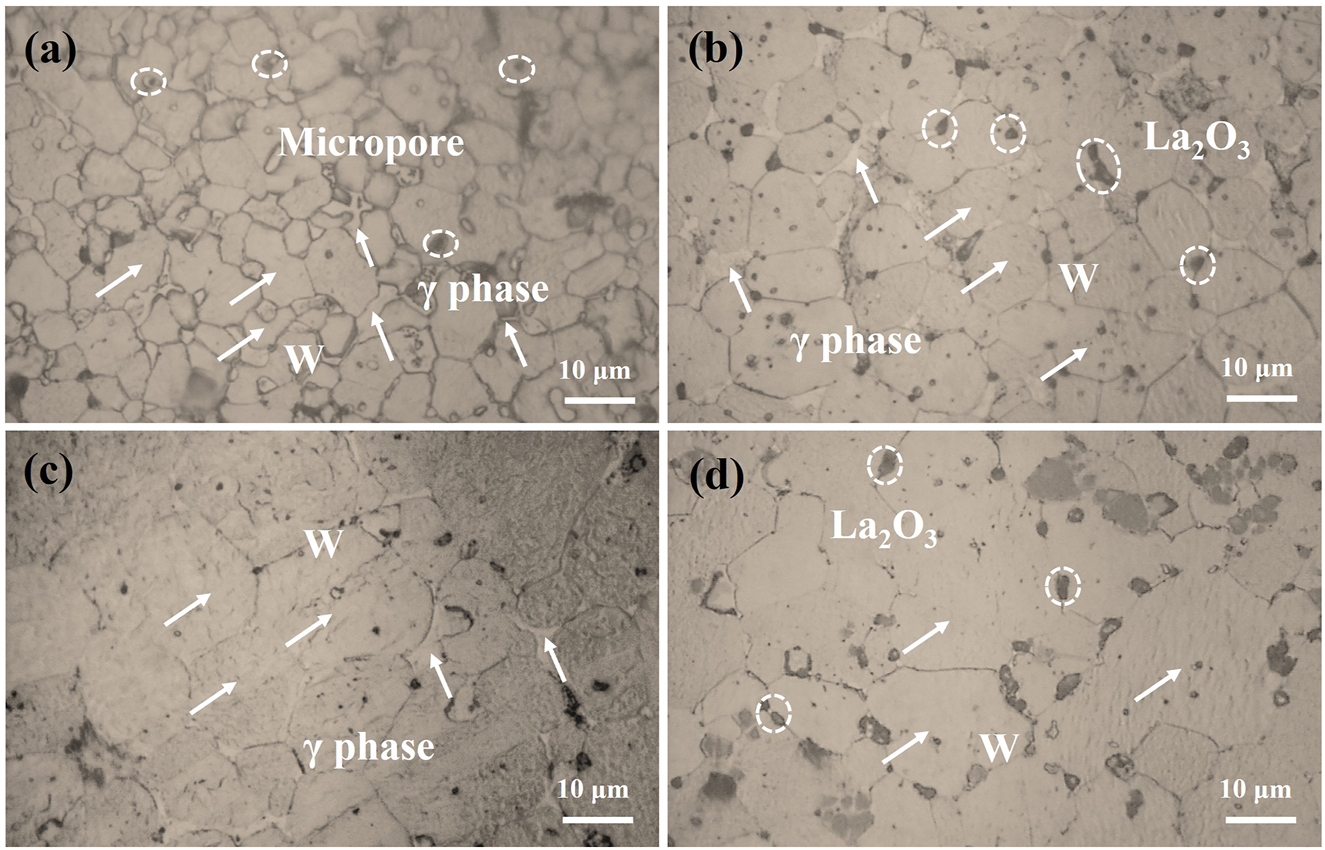

The effect of different second-phase reinforcing particles (La2O3, HfC) on the microstructure of WHA matrix composites was analyzed using OM, and the results are shown in Figure 3. Figure 3a shows typical tungsten particles (bright white polygonal shape) evenly distributed in the gray bonding phase matrix. The overall structure is clear and dense, but a small number of micro-voids are also visible, which is a typical feature of the base WHA [18]. Figure 3b shows the addition of La2O3 particles, which are dispersed as small dark spots in the bonding phase and at the particle boundaries. This effectively refines the tungsten grains and significantly reduces the number of voids, indicating that La2O3 promotes densification and improves microstructure uniformity during sintering. In Figure 3c, although no distinct HfC particles were directly observed, possibly due to the low contrast with the matrix or the particle size being close to the resolution limit, the microstructure shows a more uniform distribution of tungsten grains and bonding phase morphology, indicating that HfC may improve structural consistency by inhibiting grain growth or promoting sintering. In Figure 3d, both La2O3 and HfC were added, and the presence of La2O3 particles can be identified. The bonding between tungsten particles is tighter, the voids are further reduced, and the microstructure uniformity is significantly better than that with a single addition, demonstrating the synergistic effect of the second-phase composite reinforcement. Comparing the microstructure of these four samples, the average sizes of tungsten particles are 6.2 μm (S-A), 7.7 μm (S-B), 14.1 μm (S-C), and 13.8 μm (S-D), respectively. The increased particle size and reduced micro-voids can be attributed to the promoting effect of La2O3 and HfC on the sintering process [3], 17]. On the other hand, La2O3 and HfC particles can provide more nucleation sites for tungsten particle growth, thereby refining the grains of the tungsten matrix. Therefore, the introduction of both La2O3 and HfC optimizes the microstructure of the WHAs, but since HfC is difficult to identify under OM, SEM in BSE mode and EDS are needed for further compositional and distribution characterization to clarify its form and strengthening mechanism.

OM images of WHA composites. (a) S-A, (b) S-B, (c) S-C, and (d) S-D.

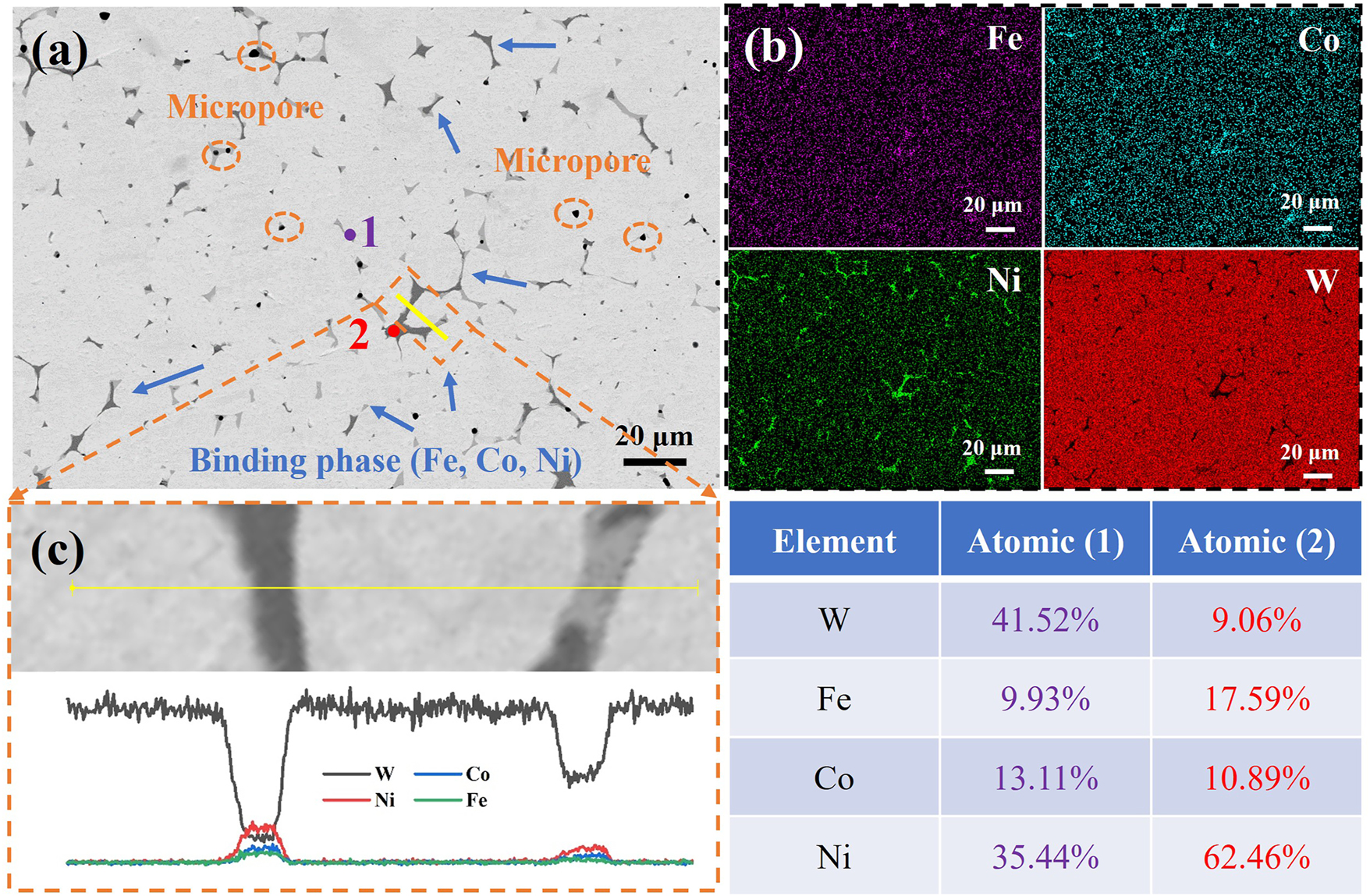

Figure 4a shows a SEM morphology of S-A in BSE mode, the bright white W particles are surrounded by a thin dark gray (Fe, Co, Ni) layer, but black micro-voids are still scattered at the three-phase boundaries, becoming the earliest stress concentration sources and crack initiation points under external forces [21]. The EDS surface scan in Figure 4b confirms that Fe, Co, and Ni form a continuous network in the gaps between W particles, ensuring complete alloying of the sintering neck. It both “welds” the hard phase and relaxes stress under load due to the high dislocation activity of the FCC structure. The point scan quantitative results in the table of Figure 4 show significant differences in the solubility of W in the bonding phase in different regions. The low W regions remain soft and ductile, which is beneficial for plastic deformation. The high W regions enhance lattice matching with W particles, increasing interface bonding strength, and the two complement each other, balancing both toughness and strength. The line scan in Figure 4c further reveals the W/bonding phase interface situation, where the W content rapidly decreases while Fe, Ni, and Co increase simultaneously. There are no hard and brittle intermetallic compounds at the interface, indicating that the bonding phase has fully wetted and tightly connected the W particles.

(a) SEM image of S-A, (b) element distribution, and (c) line scan.

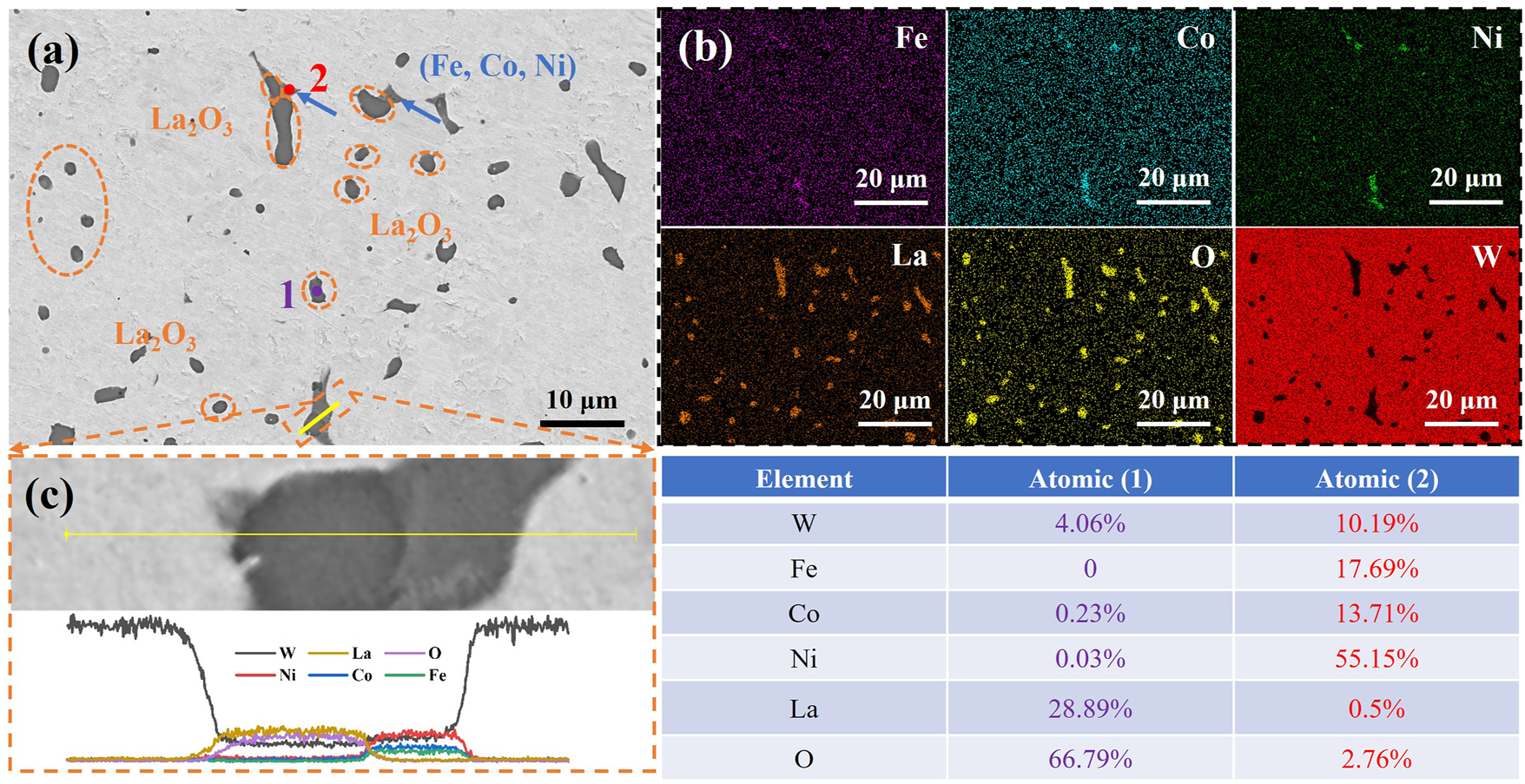

Figure 5 shows the microstructure of the S-B composite sample. Figure 5a shows that La2O3 particles preferentially distribute along the bonding layer, forming dispersed points that hinder dislocation motion and suppress grain boundary sliding during the later stages of sintering. This transforms the bonding phase from a “soft medium” into a “strong and tough framework,” providing the alloy with higher yield strength and fatigue resistance. The EDS mapping shown in Figure 5b confirms that La2O3 remains undecomposed, maintaining its complete crystal structure, and can exist stably for a long time, continuously purifying the grain boundaries and reducing the interface energy. The line scanning in Figure 5c further reveals that along the W-bonding phase-W path, the La peak only appears in the middle bonding region, with no La diffusion into the W matrix on either side. The interface transition is steep, and no brittle intermetallic compounds are formed. This indicates that La2O3 enhances the bonding phase strength and overall alloy toughness effectively through a dual mechanism of “pinning + purification” without affecting the interface bonding [22].

(a) SEM image of S-B, (b) element distribution, and (c) line scan.

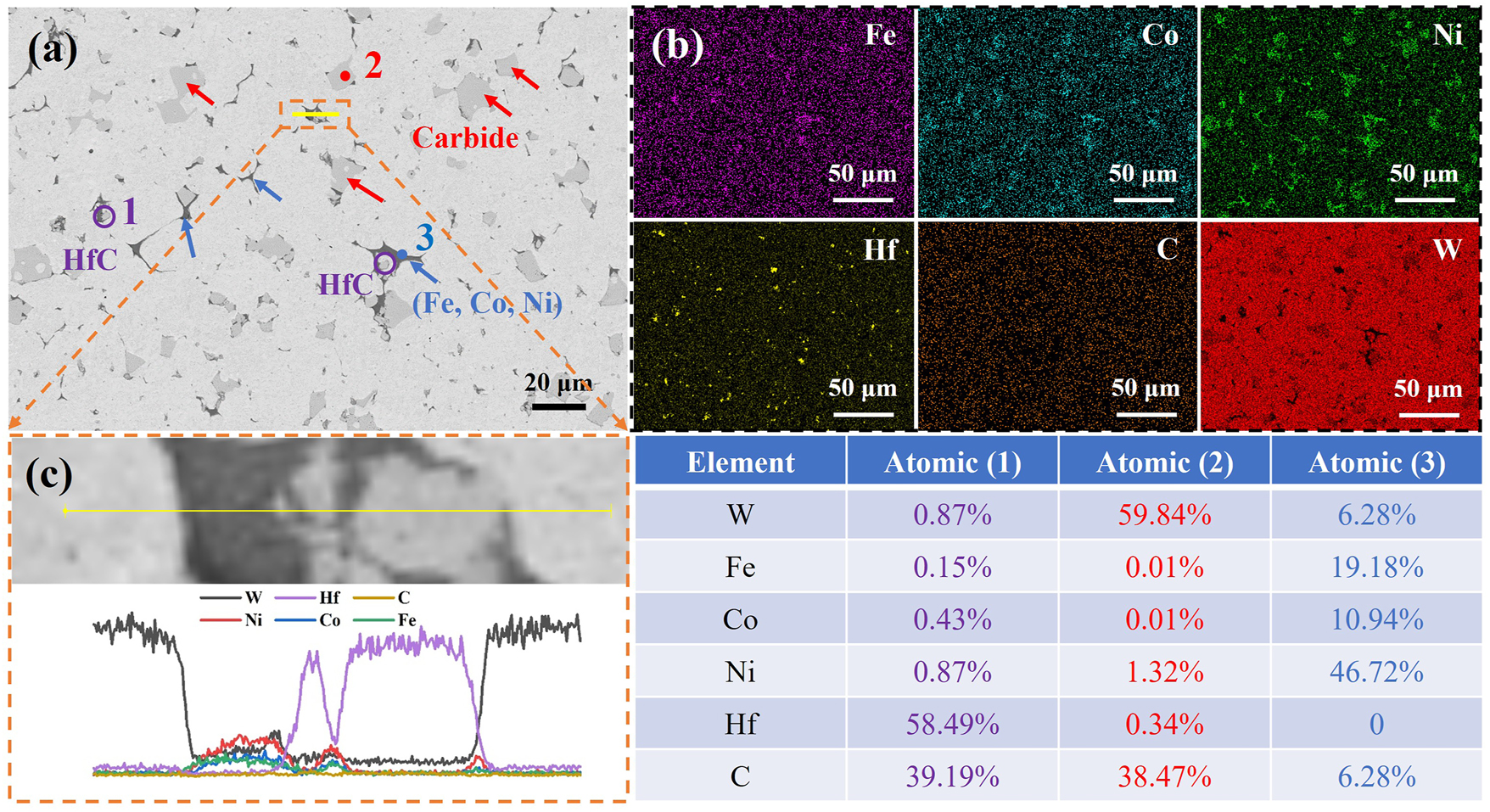

Figure 6 shows the SEM images in BSE mode of S-C (1 wt% HfC). The point scanning data in Figure 6a shows that the introduction of HfC promotes the formation of new carbides in the matrix. Combined with the EDS analysis in Figure 6b, it is inferred that these newly formed carbides are (Hf,W)C [23], which is also confirmed by the XRD analysis (Figure 2). This phenomenon is attributed to the localized high-temperature regions generated inside the powder during microwave sintering, which significantly increases the carbon diffusion coefficient, making it easier for carbon in HfC to release into the matrix. Although Fe, Co, and Ni are bonding elements, under high carbon activity and high-temperature conditions, they can combine with W and C to form composite carbides. The rapid heating characteristics of microwave heating suppress the formation of equilibrium phases, allowing these metastable carbides to be retained. The formation of these composite carbides helps to improve the hardness and wear resistance of the alloy. In addition, a small amount of HfC phase remains in the material. The line scan results in Figure 6c reveal that these HfC particles are primarily distributed around the bonding phase, that is, between the tungsten particles.

(a) SEM image of S-C, (b) element distribution, and (c) line scan.

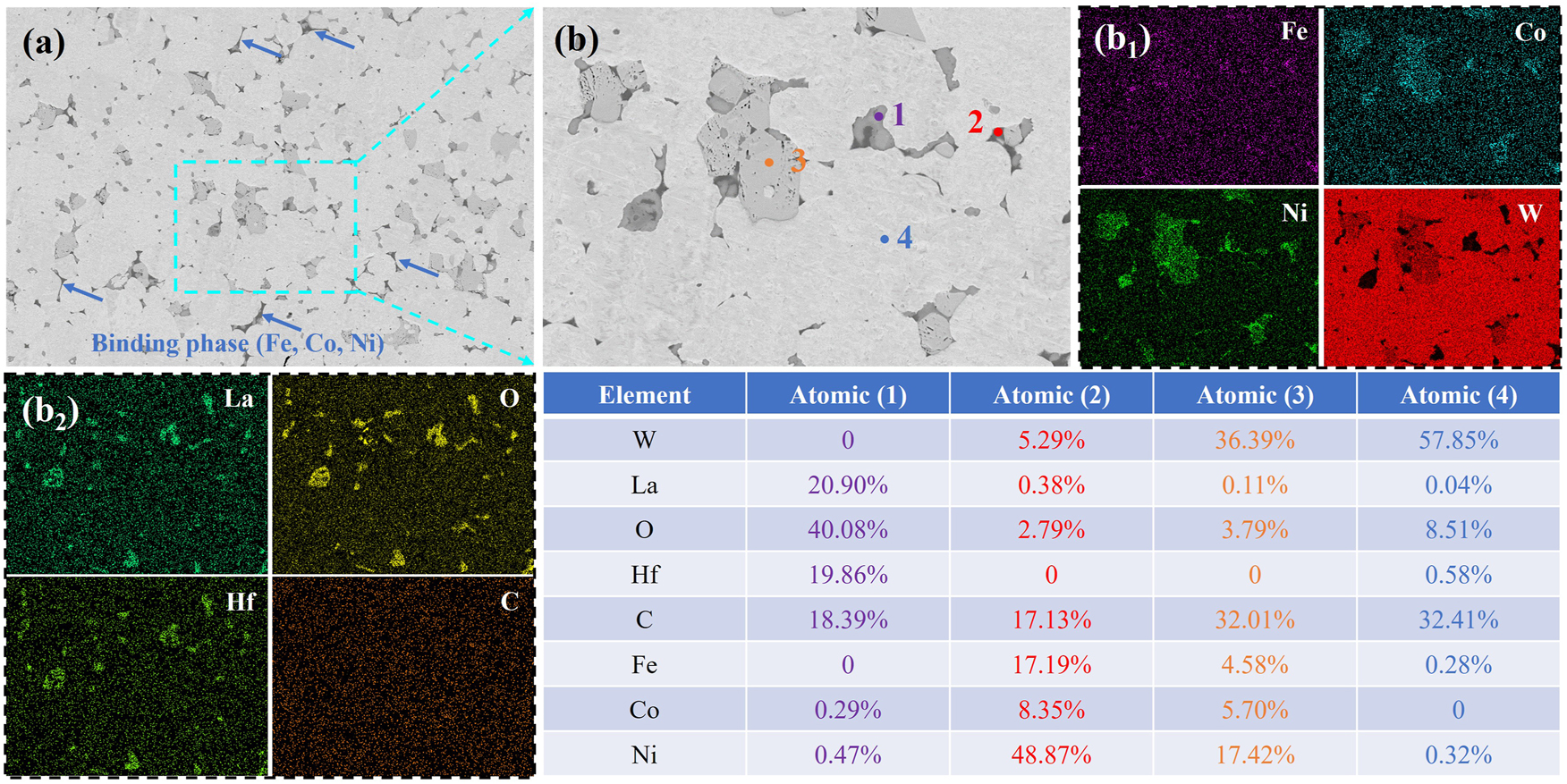

Figure 7 shows the SEM images of the sample after the addition of La2O3 and HfC (S-D). From Figure 7a, it can be observed that the composite carbides, similar to those in Figure 6, still exist, which is a result of the interaction between HfC and the matrix material. The point 3 elemental content analysis and XRD results in Figure 7b further confirm the existence of these composite carbides. In addition, the elemental content analysis of point 1 and the elemental distribution map in Figure 7b2 reveal that La2O3 and HfC tend to combine together and are mainly distributed in the bonding phase region. This distribution may be due to the interaction between La2O3 and HfC during the material preparation process, as well as their solubility and diffusion behavior in the bonding phase.

(a, b) SEM image of S-D, (b1, b2) element distribution.

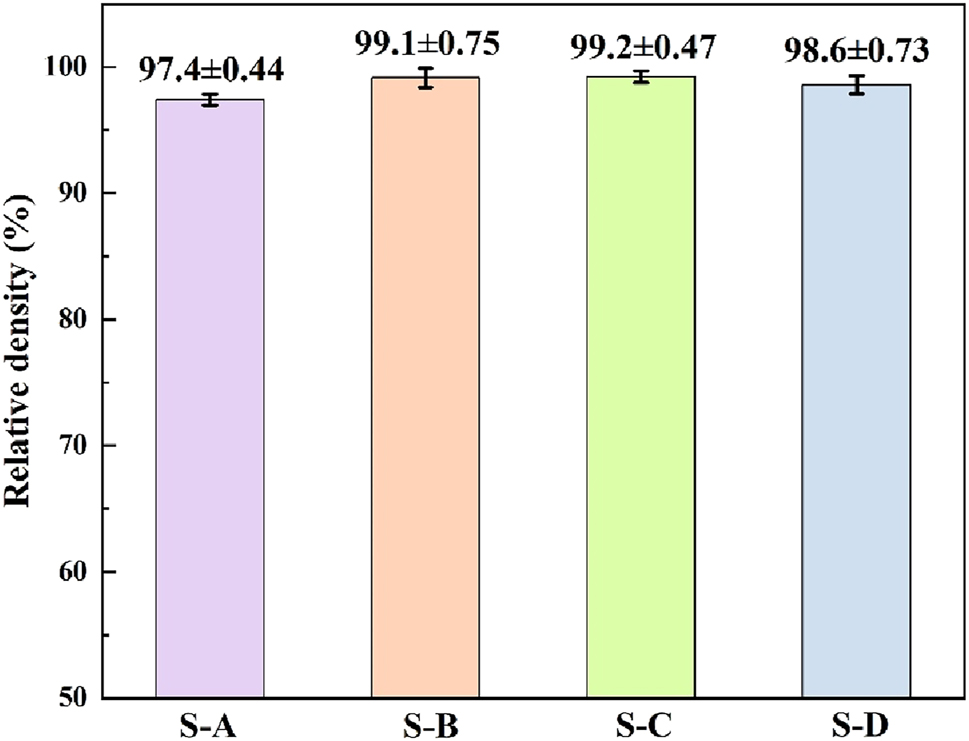

3.3 Relative density analysis

The effect of different second-phase reinforcing particles on the relative density of WHA matrix composites is analyzed, and the results are shown in Figure 8. The relative densities of all materials are at a high level, indicating that the sintering process achieved good densification. Specifically, the addition of La2O3 or HfC alone helps to further improve the material’s density, with relative densities of 99.1 ± 0.75 % and 99.2 ± 0.47 %, respectively. They are higher than the SPS prepared W–Ni–Fe–La2O3 composites (≤87.95 %) [24] and the 90W–7Ni–3Cu alloy prepared by conventional sintering [19]. This result suggests that La2O3 and HfC may effectively enhance the material’s sintering activity and densification through mechanisms such as inhibiting abnormal grain growth of tungsten, promoting diffusion mass transfer, or optimizing liquid phase distribution during sintering. It is worth noting that when La2O3 and HfC are added in combination, the relative density slightly decreases to 98.6 ± 0.73 %, but still remains at a high level. This phenomenon may be due to the interaction between the two reinforcing phases during sintering, such as local agglomeration between particles, interface hindrance of material migration, or differences in sintering kinetics, which slightly inhibit the final densification. Despite the slight decrease, the value remains within the error range, indicating that the overall densification ability of the composite addition system is still excellent.

The relative density of WHA composites.

3.4 Mechanical properties analysis

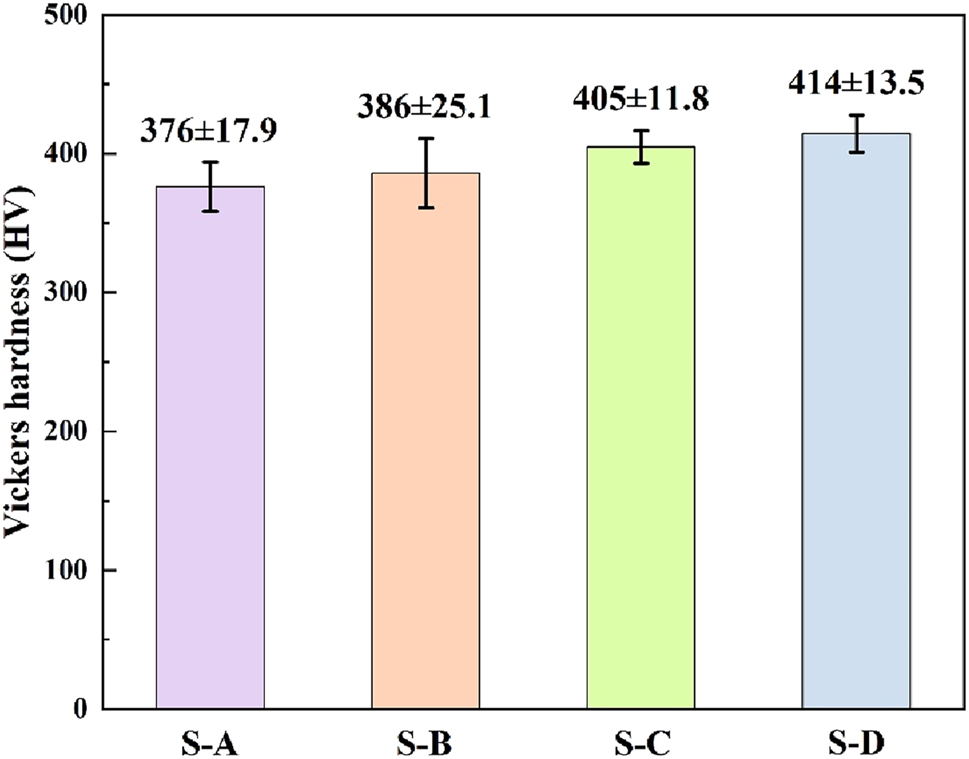

By analyzing the Vickers hardness test results, the influence of different second-phase reinforcing particles on the strengthening effect of WHAs can be clearly revealed (Figure 9). Compared to the unreinforced pure WHA matrix, the introduction of second-phase particles significantly improves the material’s hardness, although it is higher than some of the reported W–Ni–Fe–La2O3 composites [24]. The strengthening mechanisms and effects of various second-phase particles are different. La2O3 particles mainly function through grain refinement and dispersion strengthening mechanisms. Their small oxide particles purify and pin the grain boundaries, hindering dislocation motion, thus enhancing resistance to plastic deformation [25]. In Figure 6, it was found that HfC undergoes mutual dissolution and reaction with the tungsten matrix, forming composite carbide phases. The formation of this new phase helps to improve the material’s hardness. On one hand, the in situ generated composite carbide phase has a higher interface bonding strength with the tungsten matrix than the added second-phase particles, effectively pinning dislocations and hindering grain boundary sliding, thus contributing a considerable dispersion strengthening effect. On the other hand, the unreacted HfC, as a high-hardness carbide phase, can effectively hinder dislocation motion in the tungsten matrix, leading to an increase in hardness [25]. The most significant effect is observed in the sample with the composite addition of La2O3 and HfC, where the hardness value reaches the highest level among all groups. This is attributed to the excellent synergistic strengthening effect produced by the two reinforcing particles. La2O3 mainly acts on grain refinement and grain boundary strengthening, while HfC provides strong dispersion strengthening due to the in situ reaction. The two mechanisms work together to more effectively increase the resistance to dislocation motion, resulting in the composite material exhibiting the highest hardness at the macroscopic level.

The Vickers hardness of WHA composites.

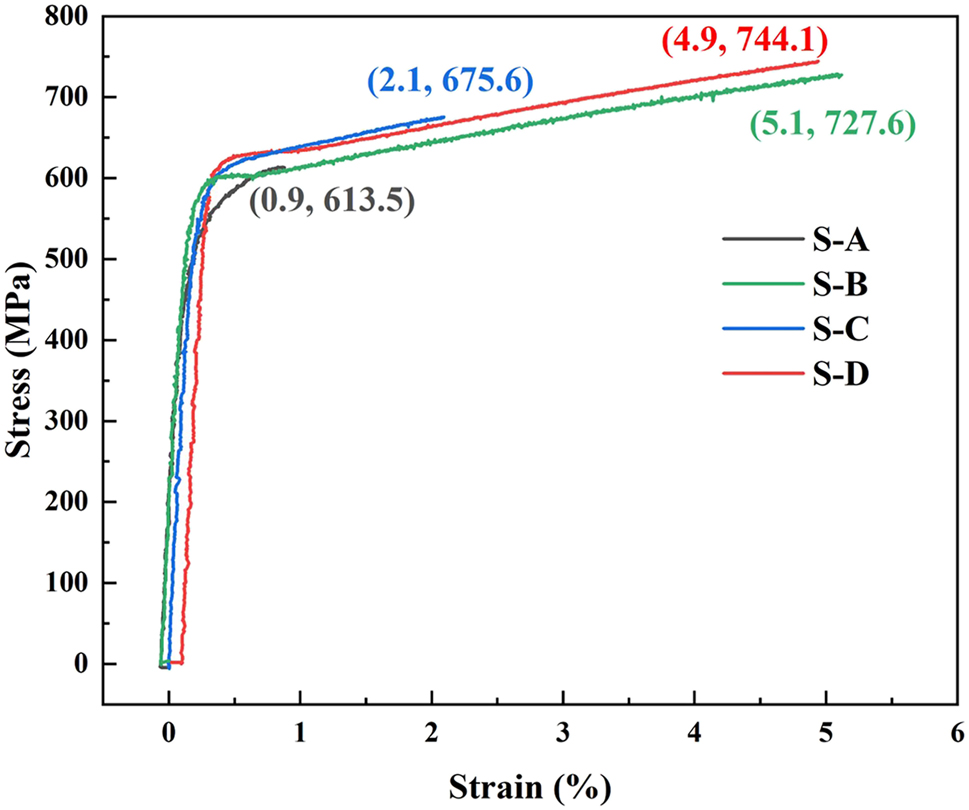

Based on the tensile stress–strain curve of the WHA matrix composites (Figure 10), the strengthening and toughening mechanisms and effects of different added phases can be clearly revealed. From the performance benchmark of the base alloy S-A (W+(Fe, Co, Ni)), its tensile stress is 613.5 MPa, and its strain is only 0.9 %, which is higher than some WHAs [24], but it still demonstrates the typical high-strength and low-toughness characteristics of traditional WHAs, with clear brittle fracture behavior. After replacing part of the bonding phase with La2O3 in sample S-B, the performance underwent a qualitative leap, with its stress increasing to 727.6 MPa and strain significantly rising to 5.1 %. This result is mainly attributed to the dispersion strengthening effect of La2O3 oxide and its optimization effect on the microstructure. La2O3 particles effectively hinder dislocation motion, while refining the grains, purifying, and strengthening the grain boundaries and phase interfaces, thereby significantly enhancing strength while greatly improving the material’s plastic deformation ability, achieving excellent strengthening and toughening. In contrast, after replacing with HfC in sample S-C, its stress increased to 675.6 MPa, and strain only slightly increased to 2.1 %. This indicates that HfC, as a hard second phase, mainly improves strength through second-phase strengthening mechanisms, but its inherent brittleness and metastable carbides somewhat limit further improvement in toughness, making its strengthening and toughening effect less significant than La2O3. In sample S-D, the simultaneous introduction of La2O3 and HfC resulted in synergistic optimization of performance, achieving high strength (744.1 MPa) and toughness (4.9 %). This indicates that the two additives played an ideal complementary role. HfC, as the main strengthening phase, provides the foundation for strength, while La2O3, while contributing to dispersion strengthening, more critically counteracts the brittleness risk that HfC may introduce through its toughening mechanism, together enhancing the overall performance of the material. In summary, the variation pattern of WHA samples reveals that La2O3 is an effective toughening agent in WHAs, while HfC is a reliable strengthening agent. Their combination can achieve a balance of performance. Therefore, through multiscale microstructure design, which synergistically utilizes different types of second phases to overcome the strength-toughness contradiction of WHA, a clear theoretical basis and practical path are provided. It is worth noting that the stress–strain curve shows a significant difference in slope before and after the inflection point (yield point), and the fundamental reason lies in the fundamental change in the dominant deformation mechanism of the material. Before the inflection point, reversible elastic deformation occurs due to the cooperative interaction of all atoms, showing a constant high slope (elastic modulus). After the inflection point, irreversible plastic deformation dominated by dislocation slip, proliferation, etc. begins, and its slope (work hardening rate) strongly depends on the ability of second-phase particles, grain boundaries, and other defects to hinder dislocation motion.

The tensile stress–strain curve of WHA composites.

3.5 Fracture analysis

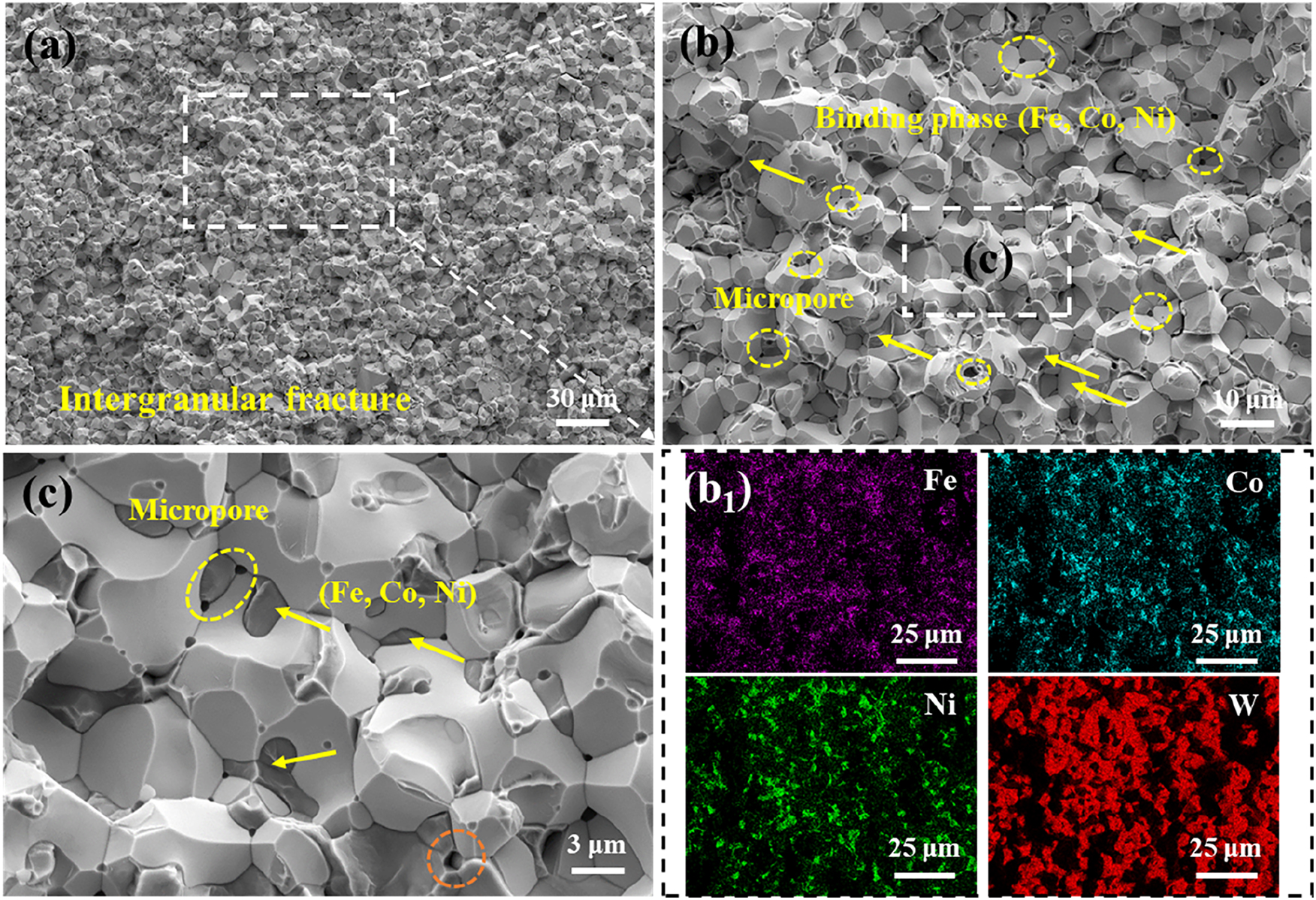

To analyze the strengthening mechanism, fracture surface characterization was performed on each composite. Figure 11a shows that the fracture mode of the WHA is intergranular fracture. From the magnified images in Figure 11b, 11b1, and 11c, it can be seen that the γ bonding phase is distributed between W grains, acting as a bridge, which helps to improve the alloy’s toughness. In addition, it can be seen that micropores are mainly distributed in the bonding phase, which may lead to premature failure of the bonding phase, preventing it from functioning effectively. Figure 11a indicates that the WHA primarily exhibits intergranular fracture. Figure 11b and 11b1 show that the γ bonding phase forms a continuous thin-film coating around the W grains. During crack propagation, it undergoes noticeable plastic deformation and forms bridging ligaments, effectively suppressing crack instability and improving alloy toughness. As seen in Figure 11c, the micropores are mainly distributed in the aggregated bonding phase, becoming the sites of initial failure. This occurs because the micropores preferentially nucleate, grow, and link within the bonding phase, leading to local stress concentration. When the void volume fraction reaches a critical value, the bonding phase fails prematurely, the bridging effect decreases sharply, and it becomes the limiting factor for toughness reduction.

(a, b, c) Fracture surface morphology of S-A, (b1) element distribution in b.

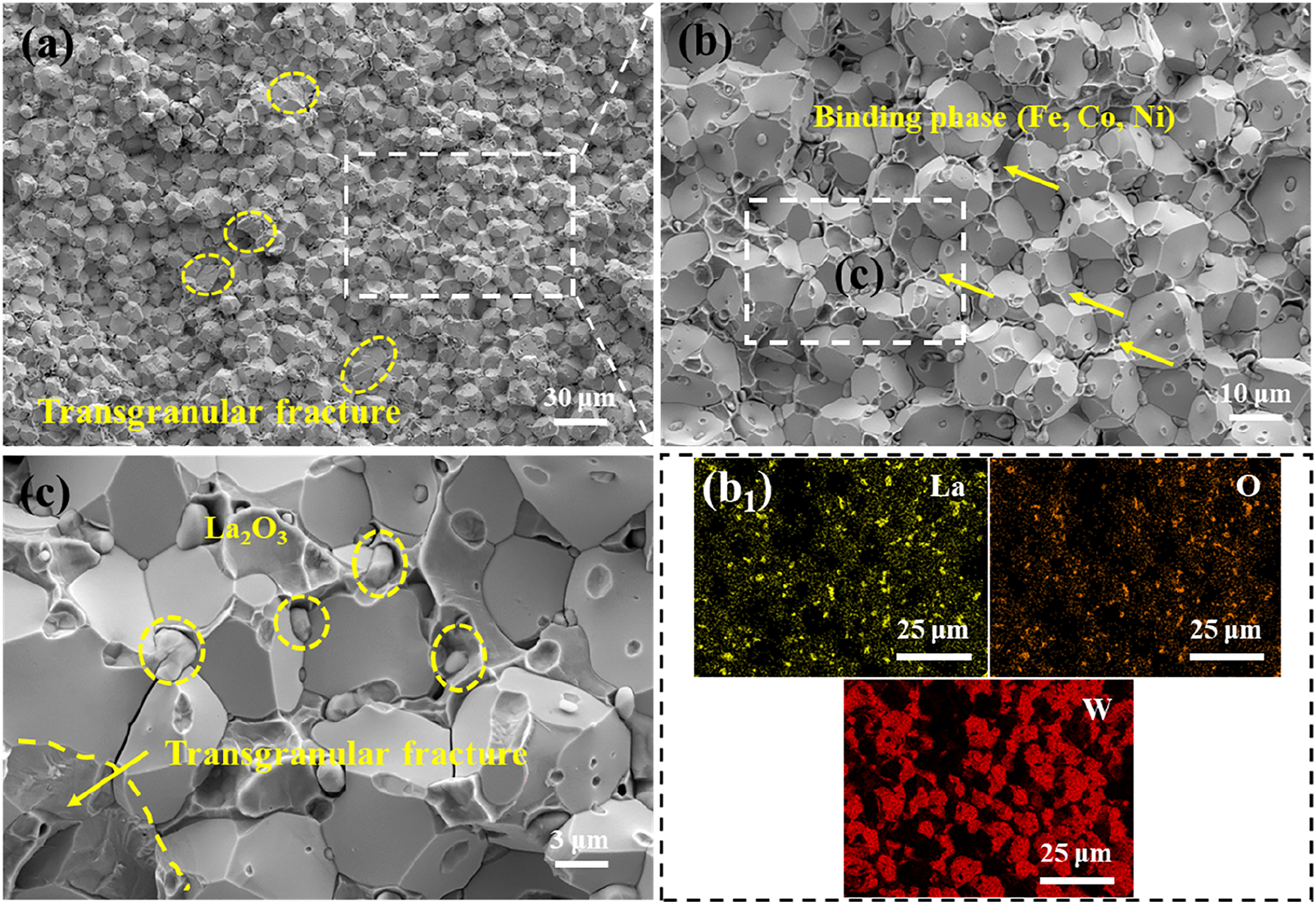

Figure 12 reveals the regulatory effect of La2O3 on the fracture behavior of WHAs. When La2O3 is not added, cracks rapidly propagate along the W grain boundaries, showing typical intergranular brittle fracture (Figure 11). After adding La2O3, the fracture mode shifts to transgranular fracture (Figure 12a), indicating that the cracks are forced to cut through the W grains. The appearance of transgranular fracture means that the bonding strength of the grain boundaries is greater than the intragranular strength. The grain boundaries no longer serve as crack propagation paths, and more energy is required to tear the grains, which macroscopically manifests as improved impact toughness and fracture toughness. Figure 12b and 12b1 show that La2O3 and the γ bonding phase are distributed between the W grain boundaries, which helps to improve the bonding strength between the W grain boundaries, thereby increasing the strength of the composite material. Therefore, the addition of La2O3 increases the bonding strength of the W grain boundaries, making it greater than the intragranular strength, causing the fracture mode to transition from intergranular to transgranular, which macroscopically results in increased toughness and strength. La in La2O3 has high activity and preferentially combines with harmful impurities such as O, S, and P enriched at the grain boundaries, eliminating impurity embrittlement. At the same time, La2O3 segregates at the grain boundaries, reducing interface energy and hindering W grain boundary diffusion, significantly improving the grain boundary bonding strength after sintering [26]. In addition, La2O3 precipitates uniformly within the γ bonding phase (Figure 12c), increasing the strength of the bonding phase. After the bonding phase hardens, it more effectively transfers the load to the W grains, indirectly enhancing the load-bearing capacity of the grain boundaries. When the external load exceeds the cohesive strength of the grains, cracks can only propagate transgranularly, eventually leaving a cleavage appearance on the fracture surface, achieving an improvement in strength and toughness. Furthermore, La2O3, as a second-phase particle, can improve the composite material’s performance through the typical Orowan strengthening mechanism.

(a, b, c) Fracture surface morphology of S-B, (b1) element distribution in b.

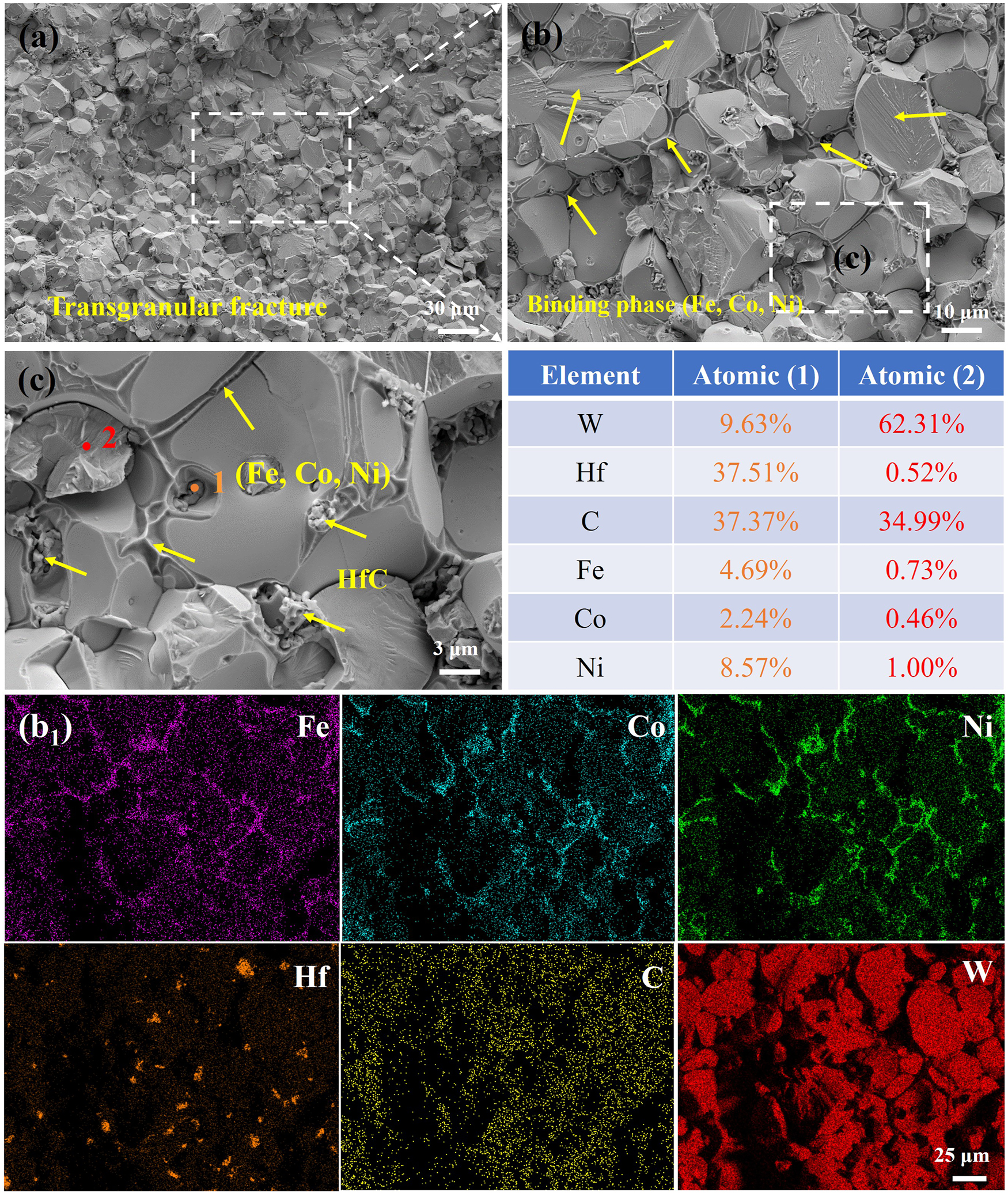

As shown in Figure 13, after the addition of HfC, the fracture morphology of the composite material is characterized primarily by transgranular fracture (Figure 13a). According to Figure 13b and the corresponding EDS analysis results (Figure 13b1), the γ bonding phase is still distributed between W grains, serving as a toughening connector and effectively alleviating stress concentration. HfC particles are dispersed within the γ phase, significantly enhancing the load-bearing capacity of the bonding phase, thereby increasing the overall strength of the material. Through point scan analysis in Figure 13c, it can be seen that the transgranular fracture surface is enriched with W carbides, which is due to the introduction of HfC promoting the formation of composite carbides. These carbides are thermodynamically in a metastable state and under external loading, they are prone to becoming preferred sites for crack initiation and propagation, leading the fracture path to traverse through the grain interiors, exhibiting a typical transgranular fracture mode [27]. In addition, HfC particles can effectively hinder the crack propagation path during crack expansion, consuming fracture energy through pinning or deflection mechanisms, thereby enhancing the material’s fracture toughness and high-temperature performance. In summary, the addition of HfC improves the mechanical behavior of the composite material by regulating the performance of the bonding phase and inducing second-phase strengthening.

(a, b, c) Fracture surface morphology of S-C, (b1) element distribution in b.

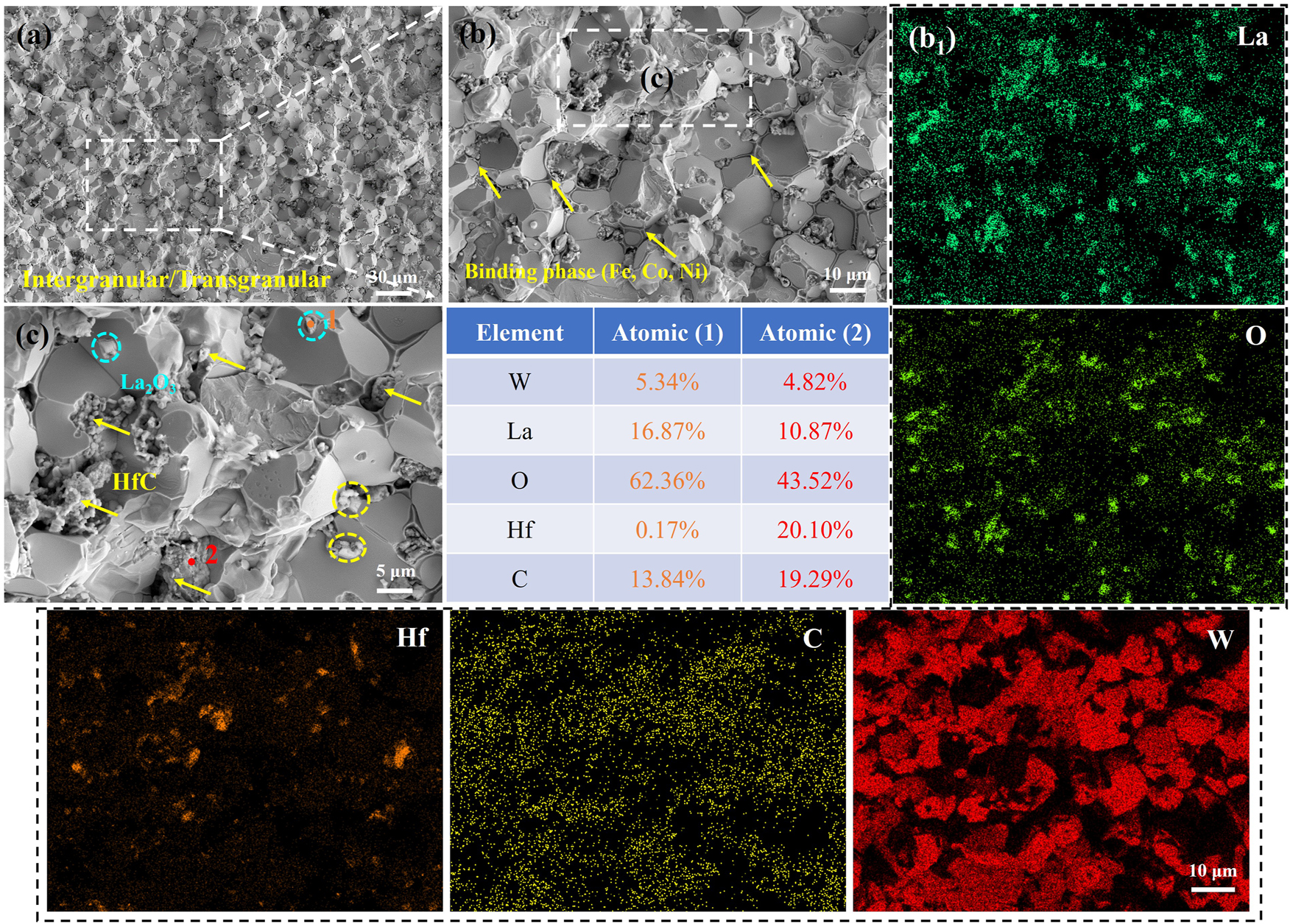

Figure 14 shows the SEM images of the WHA matrix composite synergistically reinforced by La2O3 and HfC. As seen in Figure 14a, the fracture mode of the composite material is a mixed pattern of transgranular and intergranular fracture. The γ bonding phase is uniformly distributed between the W particles, forming a continuous network structure that significantly enhances the material’s toughness. La2O3 and HfC are mainly distributed in the grain boundary regions (Figure 14c and 14b1), where they not only purify grain boundaries and suppress impurity segregation but also effectively strengthen the γ bonding phase. During crack propagation, they promote crack deflection, consuming more fracture energy and thereby enhancing the overall strength and toughness. The synergistic effect of the two phases significantly optimizes the microstructure and mechanical properties of the composite material.

(a, b, c) Fracture surface morphology of S-D, (b1) element distribution in b.

In summary, based on the microstructure and fracture analysis, S-A (W+(Fe, Co, Ni)) represents the traditional strengthening path, where the strength mainly comes from the deformation resistance of the tungsten grains themselves and the high density achieved through liquid-phase sintering. The solid solution strengthening effect provided by the bonding phase is limited. This mechanism, due to its coarse grains and weak W-bonding phase interface, results in both strength and toughness being at lower levels. The S-B sample, with La2O3 introduced, has its strengthening mechanism centered around dispersion strengthening and grain boundary engineering. La2O3 particles, as stable obstacles, pin dislocations through the Orowan mechanism, thereby increasing strength. More importantly, it greatly enhances the interface bonding strength by inhibiting grain boundary migration, refining grains, and purifying the grain boundaries [28]. The S-C sample (with added HfC) mainly reflects the typical second-phase strengthening. HfC, as a hard particle, also enhances strength by hindering dislocation movement. However, due to the metastable carbide formed with the matrix, it easily becomes a nucleation site for microcracks during deformation, making its strengthening path more focused on a single increase in strength, with limited contribution to improving toughness [29]. The final S-D sample (with both La2O3 and HfC added) demonstrates a multiscale synergistic strengthening approach. HfC, as the main load-bearing phase, provides the basic strength increment, while La2O3 optimizes the interface and passivates cracks, effectively offsetting the brittleness risk that HfC may introduce. The two phases collaborate at different scales, jointly creating a composite material system that efficiently resists deformation and effectively dissipates fracture energy, thus achieving a balance between strength and toughness.

4 Conclusions

This study uses microwave sintering technology to prepare WHAs by incorporating nano-size La2O3 and HfC as second-phase reinforcing particles into the W–Fe–Co–Ni matrix. The effects of the second-phases on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the four prepared samples were systematically analyzed, leading to the following conclusions:

The WHA grains were significantly refined with the introduction of La2O3 and HfC, and the samples show an increasement in compactness. La2O3 mainly accumulated at the grain boundaries and pinned the grain boundaries, while HfC was dispersed randomly.

The addition of La2O3 and HfC into the composites simultaneously improved the relative density and mechanical properties. S-D has the highest Vickers hardness of 414 ± 13.5 HV and tensile strength of 744.1 MPa. S-B and S-D show a synergistic improvement in strength and ductility.

The strengthening effect comes from La2O3’s grain boundary pinning and HfC’s dispersion strengthening and dislocation pinning. The two synergistically promote sintering densification and improve interface load transfer.

-

Funding information: This study was financially supported by the Defense Industrial Technology Development Program of China (NO: JCKY2022212C002) and the Young Scientist Project of National Key Research and Development Program of China (NO: 2024YFE03260100).

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Fan, JL, Gong, X, Huang, BY, Song, M, Liu, T, Tian, JM. Densification behavior of nanocrystalline W-Ni-Fe composite powders prepared by sol-spray drying and hydrogen reduction process. J Alloys Compd 2010;489:188–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.09.050.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Wu, Z, Zhang, Y, Yang, CM, Liu, QJ. Mechanical properties of tungsten heavy alloy and damage behaviors after hypervelocity impact. Rare Met 2014;33:414–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-014-0320-5.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Zou, JM, Xiao, Q, Chen, BQ, Li, YL, Han, SC, Jiao, YL, et al.. Effect of HfC addition on the microstructure and properties of W-4.9Ni-2.1Fe heavy alloys. J Alloys Compd 2021;872:159683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.159683.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Li, H, Zhang, X, Liu, QJ, Liu, YY, Liu, HF, Wang, XQ, et al.. First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy. Nanotechnol Rev 2019;8:258–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0024.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Li, YC, Zhang, W, Li, JF, Lin, XH, Gao, XQ, Wei, FZ, et al.. Microstructure and high temperature mechanical properties of advanced W–3Re alloy reinforced with HfC particles. Mater Sci Eng, A 2021;814:141198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2021.141198.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Zhang, T, Xie, ZM, Yang, JF, Hao, T, Liu, CS. The thermal stability of dispersion-strengthened tungsten as plasma-facing materials: a short review. Tungsten 2019;1:187–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42864-019-00022-9.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Cheng, C, Song, ZW, Wang, LF, Zhao, L, Wang, LS, Guo, LF, et al.. Effects of microalloying elements added by in situ synthesis on the microstructure of WCu composites. Nanotechnol Rev 2022;11:760–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0045.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Hu, P, Gong, X, Liu, H, Zhou, WY, Wang, JS. A novel dissolution-precipitation strategy to accelerate the sintering of yttrium oxide dispersion strengthened tungsten alloy with well-regulated structure. J Mater Sci Technol 2024;184:43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2023.11.004.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Ren, C, Fang, ZZ, Koopman, M, Butler, B, Paramore, J, Middlemas, S. Methods for improving ductility of tungsten – a review. Int J Refract Met H 2018;75:170–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.04.012.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Yang, JJ, Chen, Z, Yu, Y, Xu, HF, Jia, BR, Wu, HY, et al.. The effect of La2O3 content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of W-La2O3 alloys via pressureless sintering. Mater Charact 2025;227:115239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2025.115239.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Chen, PQ, Xu, X, Wei, BZ, Chen, JY, Qin, YQ, Cheng, JG. Enhanced mechanical properties and interface structure characterization of W–La2O3 alloy designed by an innovative combustion-based approach. Nucl Eng Technol 2021;53:1593–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2020.11.002.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Sun, HH, Wang, M, Zhou, JN, Xi, XL, Nie, ZR. Refinement of Al-containing particles and improvement in performance of W-Al-Y2O3 alloy fabricated by a two-step sintering process. Int J Refract Met H 2023;110:106028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2022.106028.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Zhao, YC, Xu, LJ, Li, Z, Guo, MY, Wang, CJ, Li, XQ, et al.. Effect of different crystal forms of ZrO2 on the microstructure and properties of tungsten alloys. Int J Refract Met H 2023;114:106258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2023.106258.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Wang, CJ, Huang, H, Wei, SZ, Zhang, LQ, Pan, KM, Dong, XN, et al.. Strengthening mechanism and effect of Al2O3 particle on high-temperature tensile properties and microstructure evolution of W–Al2O3 alloys. Mater Sci Eng, A 2022;835:142678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2022.142678.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Liu, M, Liu, XS, Liu, W, Zhao, XM, Li, R, Song, JP, et al.. Comparative study on microstructure and performance of sintered, forged and annealed W-3Re-HfC composites. Int J Refract Met H 2022;102:105716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2021.105716.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Liu, R, Xie, ZM, Yao, X, Zhang, T, Wang, XP, Hao, T, et al.. Effects of swaging and annealing on the microstructure and mechanical properties of ZrC dispersion-strengthened tungsten. Int J Refract Met H 2018;76:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.05.018.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Li, JF, Cheng, JG, Wei, BZ, Zhang, ML, Luo, LM, Wu, YC. Microstructure and properties of La2O3 doped W composites prepared by a wet chemical process. Int J Refract Met H 2017;66:226–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2017.04.004.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Ma, YZ, Zhang, JJ, Liu, WS, Zhao, YX. Transient liquid-phase sintering characteristic of W-Ni-Fe alloy via microwave-assisted heating. Rare Metal Mater Eng 2014;43:2108–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1875-5372(14)60158-2.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Mondal, A, Upadhyaya, A, Agrawal, D. Microwave and conventional sintering of 90W–7Ni–3Cu alloys with premixed and prealloyed binder phase. Mater Sci Eng, A 2010;527:6870–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2010.07.074.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Shakunt, NS, Gouthama, UA. Effect of La2O3 addition on microstructure and mechanical properties of W-Ni-Cu tungsten heavy alloy. Mater Chem Phys 2024;318:129227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2024.129227.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Reichel, B, Wagner, K, Janisch, DS, Lengauer, W. Alloyed W–(Co,Ni,Fe)–C phases for reaction sintering of hardmetals. Int J Refract Met H 2010;28:638–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2010.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Xu, D, Fu, K, Sang, CC, Chen, RZ, Chen, PQ, Lu, YW, et al.. Investigation of the high-temperature tensile properties and helium ion irradiation resistance of W-La2O3 composites prepared by hot rolling. Fusion Eng Des 2025;218:115199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2025.115199.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Lee, D, Umer, MA, Ryu, HJ, Hong, SH. The effect of HfC content on mechanical properties HfC–W composites. Int J Refract Met H 2014;44:49–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.01.012.Suche in Google Scholar

24. AyyappaRaj, M, Yadav, D, Agrawal, DK, Rajan, RAA. Microstructure and mechanical properties of spark plasma-sintered La2O3 dispersion-strengthened W–Ni–Fe alloy. Rare Met 2021;40:2230–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-020-01390-9.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Yao, Y, Guo, JW, Wei, SZ, Yang, JH, Li, Z, Geng, HG, et al.. Study on hot deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of ultrafine W-0.5wt%La2O3 alloy wire during processing. J Mater Res Technol 2025;34:716–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.12.095.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Ma, S, Dong, D, Gao, Y, Wu, ZZ, Wang, DZ. Unveiling tensile creep mechanisms of W-Re-HfC alloys at elevated temperatures. Int J Refract Met H 2025;133:107358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2025.107358.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Chen, Z, Yang, J, Zhang, L, Jia, BR, Qu, XH, Qin, ML. Effect of La2O3 content on the densification, microstructure and mechanical property of W-La2O3 alloy via pressureless sintering. Mater Charact 2021;175:111092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2021.111092.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Yang, T, Wang, H, Feng, F, Liu, X, Gong, XY, Lian, YY, et al.. Comparison of thermal shock resistance capabilities of the rotary swaged pure tungsten, potassium-doped tungsten, and W-La2O3 alloys. Tungsten 2024;6:759–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42864-024-00270-4.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Lang, ST, Yan, QZ, Sun, NB, Zhang, XX. Preparation of W–TiC alloys from core–shell structure powders synthesized by an improved wet chemical method. Rare Met 2023;42:1378–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-018-1066-2.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Artificial neural network-driven insights into nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials melting for heat storage optimization

- Optical, structural, and morphological characterization of hydrothermally synthesized zinc oxide nanorods: exploring their potential for environmental applications

- Structural, optical, and gas sensing properties of Ce, Nd, and Pr doped ZnS nanostructured thin films prepared by nebulizer spray pyrolysis method

- The influence of nano-size La2O3 and HfC on the microstructure and mechanical properties of tungsten alloys by microwave sintering

- Green fabrication of γ- Al2O3 bionanomaterials using Coriandrum sativum plant extract and its photocatalytic and antibacterial activity

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Special Issue on Emerging Nanotech. for Biomed. and Sust. Environ. Appl.

- Beyond science: ethical and societal considerations in the era of biogenic nanoparticles

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Artificial neural network-driven insights into nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials melting for heat storage optimization

- Optical, structural, and morphological characterization of hydrothermally synthesized zinc oxide nanorods: exploring their potential for environmental applications

- Structural, optical, and gas sensing properties of Ce, Nd, and Pr doped ZnS nanostructured thin films prepared by nebulizer spray pyrolysis method

- The influence of nano-size La2O3 and HfC on the microstructure and mechanical properties of tungsten alloys by microwave sintering

- Green fabrication of γ- Al2O3 bionanomaterials using Coriandrum sativum plant extract and its photocatalytic and antibacterial activity

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Special Issue on Emerging Nanotech. for Biomed. and Sust. Environ. Appl.

- Beyond science: ethical and societal considerations in the era of biogenic nanoparticles

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”