Beyond science: ethical and societal considerations in the era of biogenic nanoparticles

-

Aditya Pratap Singh

, Mohammed Al-zharani

, Harshit Singh

Abstract

The era of biogenic nanoparticles (BNPs) marks a transformative period in nanotechnology, leveraging plants, bacteria, and fungi to synthesize nanoparticles. This green approach offers significant advantages, including enhanced biocompatibility, sustainability, and a wide range of diverse applications. The introduction of BNPs into ecosystems and their interactions with biological systems pose potential risks that demand rigorous testing and stringent regulatory oversight. Furthermore, in medical applications, the principle of informed consent is paramount, ensuring that patients are fully informed about the benefits and potential risks of BNP-based treatments. Environmental pollution and its impact is another critical area of concern. While BNPs are often promoted as environmentally friendly alternatives, their long-term effects on ecosystems remain insufficiently understood. The rapid advancement and integration of BNPs across sectors necessitate a comprehensive examination of the ethical and societal considerations to mitigate unforeseen consequences. From a societal perspective, it is crucial to ensure that the benefits of BNPs are universally accessible. Effective communication strategies are vital for establishing public trust and dispelling misconceptions, thereby promoting an informed and supportive societal response. Adaptive regulatory frameworks tailored to the unique challenges of BNPs are a must to ensure the responsible and sustainable benefits of BNPs.

1 Introduction

Nanomaterials, or nanoparticles, are being used in several fields, such as medical [1], [2], [3], diagnostic, material science, agriculture [4], 5], and food [6], [7], [8]. Current research is focusing on novel methods of nanoparticle synthesis, and the use of biological agents to produce biogenic nanoparticles has gained particular attention. In agriculture, the chemically synthesized nanoparticles (NPs) and biogenic nanoparticles (BNPs) are being tried and tested as nanofertilizers [9], nanofungicides [10], nanopesticides, nanoherbicides, nanocoatings, nanoemulsions, nanogels, and nanobiosensors [10], [11], [12], [13] and bioremediation [14]. BNPs have also been shown to enhance crop resilience to abiotic stressors, such as drought and salinity [9], 15], 16]. Comparative studies demonstrate that green-synthesized AgNPs exhibit higher antimicrobial and anticancer activities and lower cytotoxicity than their chemically synthesized counterparts, mainly due to the stabilizing biopolymer corona, which improves biocompatibility [17], [18], [19].

Biogenic synthesis utilizes biological agents, such as fungi, bacteria, and plants [20]. It is advantageous to use plants to produce nanoparticles because they are inexpensive, readily available, and scalable for large-scale production. Plants are endowed with a wide range of active ingredients, including vitamins, polysaccharides, alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, saponins, and tannins [21], 22]. Microorganisms and fungi secrete NADH-dependent reductases (e.g., nitrate reductase) and small biomolecules that can reduce metal ions such as Ag+, Au3+, and Zn2+ to their zero-valent states. In plants, phytochemicals like flavonoids, polyphenols, and terpenoids act as both reducing and capping agents, facilitating the conversion of metal salts into stable nanoparticles. Enzymes such as nitrate reductase mediate electron transfer from NADH to metal ions during synthesis. The resulting zero-valent metal atoms aggregate to form nanoparticles, which are stabilized by proteins, exopolysaccharides, and polyphenols possessing –SH or –OH groups that bind the nanoparticle surface.

Furthermore, microbes that can tolerate metals, such as bacteria, fungi, yeast, and actinomycetes, generally flourish in optimal environments (Table 1). Some microbes can withstand, accumulate, and transform metal into the corresponding metal ions [23]. For example, Bacillus subtilis was used to create the first bacterial gold nanoparticles [24]. Other bacteria have been used to develop nanoparticles made of silver, gold, copper, iron, zinc, platinum, and selenium [25]. The intracellular/extracellular route is commonly used in redox processes to reduce metals into metal ions (Figure 1).

Biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles (elements) from plant sources and their antimicrobial activity against various pathogens.

| Elements | Source | Microbes/Pathogens |

|---|---|---|

| Ti | Hibiscus rosa-sinensis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Vibrio cholerae |

| Pt | Taraxacum laevigatum | Bacillus subtilis and P. aeruginosa |

| Ni | Monsonia burkeana | Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa |

| Pd | Garcinia Pedunculata | Cronobacter sakazakii |

| Se | Emblica officinalis | S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, E. coli, A. flavus, and A. oryzae |

| Fe | Acacia nilotica | E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella spp. |

| Zn | Albizia lebbeck | B. cereus, S. aureus, and E. coli |

| Cu | Syzygium alternifolium | Alternaria solani, A. flavus, and A. niger |

| Au |

Ziziphus ziziphus

Ocimum sanctum |

E. coli

S. aureus and E. coli |

| Ag | Erythrina suberosa | B. subtilis P. aeruginosa and S. aureus |

![Figure 1:

General mechanism of biological nanoparticles [26] with three possible pathways: a) the apoptotic, b) protein/DNA interference, and c) Caspase-3.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0262/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0262_fig_001.jpg)

General mechanism of biological nanoparticles [26] with three possible pathways: a) the apoptotic, b) protein/DNA interference, and c) Caspase-3.

The metal is first trapped onto the surface of the bacterial cells, and then NADH and NADH-dependent nitrate reductase enzymes exclusively convert these trapped metals into metal ions [27]. During nanoparticle synthesis, these enzymes function as electron shuttle donors, as described in the synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bacillus licheniformis [28].

Since BNPs are synthesized using living organisms, ethical concerns are imperative. The rapid development and wide-ranging applications of BNPs have raised several ethical, societal, and regulatory concerns. As BNPs continue to gain prominence, it is essential to examine their ethical implications, particularly in sensitive areas such as healthcare and agriculture. The intersection of science, commerce, and public policy is crucial to ensuring that BNPs’ development benefits society while minimizing potential risks. We examine the ethical considerations, societal impacts, and regulatory frameworks associated with BNPs and nanotechnology as a whole, emphasizing the importance of responsible innovation in this rapidly evolving field.

Ethical concerns surrounding BNPs are multifaceted, encompassing privacy violations, potential dangers, and military applications, as well as issues related to toxicity, biocompatibility, and public trust. These concerns must be addressed through a robust ethical framework that guides the development, application, and regulation of BNPs. Additionally, the concept of informed consent in medical applications of BNPs is particularly crucial, as it ensures that patients are fully aware of the potential risks and benefits associated with their treatment.

From a societal perspective, the public’s perception and acceptance of BNPs are crucial for their widespread adoption. Misconceptions about the safety and efficacy of BNPs can hinder their development and deployment, underscoring the need for an open dialogue between scientists and the public. Furthermore, the socioeconomic implications of BNPs, particularly in bridging the gap between developed and developing nations, are significant. BNPs have the potential to enhance agricultural productivity, improve healthcare outcomes, and generate employment opportunities, thereby contributing to global sustainable development.

The regulatory landscape for BNPs is still evolving, with various countries and international organizations striving to establish guidelines that ensure their safe and effective use. The absence of a comprehensive global regulatory framework poses significant challenges, necessitating adaptive and stringent measures that can keep pace with technological advancements.

2 Ethical considerations

BNPs have become a material of wide importance within a very short period of time. The rapid rise in their applicability over such a short span has also raised serious concerns over their ethical use. Therefore, any scientific phenomenon must not only be valuable to the scientific community but must also have some economic value, must be safe, and most of all must be acceptable to the public at large. This public acceptance is largely achieved by identifying and effectively addressing ethical issues. The statutory and non-statutory regulation of BNPs will be dealt with later in this article.

Regarding the ethical framework surrounding BNPs, we first need to analyze the major ethical concerns that BNPs, in General, and Nanoparticles, in particular, have posed to the scientific community [29]. Therefore, it becomes essential for the scientific community and especially for the researchers to identify these ethical concerns well in advance and inform the public about their proper regulation [30]. Apart from the above, identifying ethical issues plays a major role in the decision-making process. Hence, it becomes increasingly crucial for regulators, policymakers, workers, and investors to be aware of the ethical issues [31] (Table 2).

Ethical issues in bionanotechnology products (BNPs) and the corresponding ethical framework.

| Ethical issues in BNPs | Ethical framework [31] |

|---|---|

| Violation of privacy | Identification and communication of issues |

| Application in the military | Acceptance by concerned parties, including workers, scientists, patients, and consumers. |

| Toxicity | Selection and implementation of controls |

| Biocompatibility and immunogenicity | Establishment of medical, economic, and social screening processes |

| Intellectual property concerns | Ensuring adequate investment in control research |

| Issues of transparency | |

| Public trust |

2.1 Informed consent in medical applications

Informed consent is an ethical principle primarily used in healthcare and medicine. In essence, the principle of informed consent dictates that every patient must have sufficient information and understanding to make an informed decision regarding their medical treatment. Relevant information should include the benefits and risks associated with that particular form of therapy, the patient’s role in the treatment, alternative treatment options available to the patient, and the patient’s right to refuse that specific line of treatment [32].

The idea of informed consent varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. While developed countries place great importance on it, in developing and underdeveloped countries, it is generally a matter of discretion. With the advancement of BNPs in medical treatment, it becomes essential that not only is the patient informed about the general concept of the treatment, but also that they are aware that nanomaterials are being administered. There are suggestions that a patient be informed that the procedure uses NPs/BNPs, and that the small size may cause unique effects in their body [33]. Challenges to informed consent can arise when BNP-based therapeutics are administered in critical or emergency where patient comprehension time is limited, or when formulations are derived from indigenous plant materials that require both individual and community consent under traditional knowledge frameworks.

2.2 Intellectual property rights and access to BNP technology

Intellectual property rights are a set of intangible rights provided to persons for the creations of their intellect [34]. These rights motivate scientists to conduct more research by enabling them to access economic incentives. IPRs also address the issue of copying and credit snatching. For society, IPRs facilitate the dissemination of more creative works to the public, and each research project lays the groundwork for future research. The primary objectives of the Intellectual Property rights paradigm are to protect the rights of innovators, their products, research sponsors, inventors, and ultimately, the public at large. It also ensures the eradication of improper exploitation, abuse, and any contravention of the project’s intellectual assets. The paradigm also ensures that the environment and encouragements for research are augmented and which shall lead to the creation of new information. It also ensures that the benefits accumulating from all innovations and developments are reasonably and justifiably disseminated. And most importantly, it promotes interindustry linkages and stimulates research through the adoption and growth of innovative technologies, thereby creating opportunities for commercialization.

Four main theories offer the justification for IPRs. They are as follows-

The Natural Rights theory – English philosopher John Locke (the father of liberalism) proposed this theory. This theory posits that every person has a natural right to their own ideas. Every individual is entitled to the creation of his mind in the same manner as he is entitled to the ownership of the creation of his labour. Therefore, the fruits of a person’s labor should be legally protected and recognized as their property, whether tangible or intangible [35].

Utilitarian theory – Jerome Bentham and John Stuart Mill proposed that the objective of any policy should be the achievement of the greatest good for the greatest number [36]. This theory examines the economic success associated with the IPR regime. One significant drawback of the utilitarian approach to IPR is that it advocates monopoly, which poses a significant ethical challenge to IPRs, as we shall see in the following paragraphs.

The Reward theory – This theory supports rewarding individuals not only for the creation of their own labour but also for the benefits humanity derives from it. This theory, therefore, justifies exclusive rights over IPRs, taking into account specific moral and ethical considerations. Exclusive rights, according to this theory, are an expression of appreciation to the creator for doing more than what they are obliged to do for society [37].

The Personhood theory – The leading advocates of this theory are Hegel and Kant [38]. According to them, if a person’s artistic expressions are tantamount to their own personality, then such expressions deserve protection similar to the safety granted to the physical self of that person, because these expressions are, in a sense, a part of that physical person. Hegel propounds that IPRs protect and permit the development of one’s character, which ultimately extends to material things. Similarly, according to him, a copier of someone’s intellectual property is a thief who offers someone else’s spirit to the public [39].

It is the interplay of all the above-mentioned theories that has led to the creation of the present-day IPR Paradigm. While the considerations for IPR date back to the early days of the Gutenberg press, it was an international exhibition in Vienna in 1873 that led to the creation of the first international legal document in this sphere, the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, in 1883. Thereafter, in 1893, the Bureaux for the Protection of Intellectual Property (BIPRI) were established. With the further advancement of the industrial and global world and the changes in the dynamics of the economy, various changes were desired in the international order governing IPRs. This was discussed by the world community at the Stockholm Convention of 1967, and as a result, the World Intellectual Property Organization was created to succeed BIPRI in 1970. WIPO today is the principal international organization dealing with IPRs. Its two main objectives are the promotion and protection of IPRs worldwide and ensuring organizational cooperation among the IPUs established by the accords administered by WIPO. The commercial aspect of IPRs is of utmost importance, and therefore, with the Inception of the World Trade Organization (WTO) after the agreement in Marrakesh, Morocco, in 1994, a need for a more holistic and sustainable international order regarding IPRs was recognized. This led to the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement in 1994 [40]. It is an international legal document binding upon all the member states of the WTO. The following IPRs are covered in the TRIPS Agreement-

Copyrights and related rights – These are a bundle of rights granted to the creators of literary, dramatic, and artistic works.

Geographical indicators – These are signs or symbols used to identify a product as having a particular geographical origin and significant market reputation.

Industrial design – It concerns the aesthetic and ornamental aspects of an article produced in any industry.

Trademarks – They are a combination of words, names, phrases, logos, symbols, designs, or images that are capable of ascertaining distinctiveness to the goods or services of one person from those of others.

Patent – It is an exclusive right granted for the invention of a product or a process which is novel, consists of an inventive step, and has industrial applicability.

Layout design of integrated circuits – These are the detailed plans used by manufacturers to fabricate integrated circuits.

Trade secrets – They are confidential information regarding a business that renders the enterprise a competitive edge over others.

The most critical IPRs concerning BNPs are patents. The main purpose of patenting is to promote innovation and scientific research, as it grants the patent holder exclusive economic rights [41]. To balance the interest, a person granted a patent must contribute to society’s further advancement in science and technology. This is achieved because he is required to publicly disclose the details of his invention and its intended use [42]. This scenario ultimately promotes competition and further research, which, in turn, benefits the scientific well-being of society [43]. For an invention to be granted a patent it has to meet the following five requirements: the subject matter of the invention must be patentable, the invention must have some utility, the invention must be novel, there must an inventive step or there should be no obviousness in the invention that is either the invention adds a feature to the already prevailing knowledge pool of practices or that a person who is skilled in that field must not find it to be obvious and that it should have the capability of being industrially applicable. The most important ethical question in patent law is what constitutes an invention. The following products or processes are widely regarded as not being inventions, and therefore they are not considered fit for Patent protection across the globe-

A frivolous invention.

An invention, the primary marketable use of which would be opposed to public order or ethics.

An invention that claims anything visibly conflicting with the well-recognized natural laws.

An invention the intended use of which will cause a serious threat or harm to humans, plants, animals, or the environment at large.

A mere discovery of a new form of a known material that does not result in the improvement of the usefulness of that known material.

A substance obtained by the mixing of other substances, resulting only in the accumulation of the properties of its components.

A method of agriculture.

A method of horticulture.

The mere arrangement or replication of known devices, each operating freely of the other in a well-established and known manner.

Any process for the curative, surgical, therapeutic, prophylactic, medicinal, diagnostic, or other treatment of human beings.

While at the outset, the IPR of a patent regarding BNPs may seem like a regular one, it poses some critical challenges. BNP novelties are always multidisciplinary in nature and function. These inventions encompass a broad range of disciplines, including chemistry, health, engineering, physics, biology, materials science, medicine, and various other scientific domains [44]. Therefore, a simple patent of a BNP requires a multidimensional approach so that its fruits can be enjoyed by society. Using rare or endangered organisms for nanoparticle synthesis may contravene biodiversity protection agreements, such as CITES. Ethical BNP research, therefore, requires sustainable sourcing, cultivation of microbial strains in controlled conditions, and compliance with conservation laws.

One of the significant ethical concerns regarding patents is the monopoly it grants to the patent holder for a specified period. While the scheme of the invention is publicly available, the patent holder can gain excessive economic advantage by licensing and authorising the use of the existing technology. This, in turn, may lead to a steep rise in the price of BNP, further restricting its affordability for a significant section of society. While BNPs in the field of cosmetics or other luxuries do not face this risk, BNPs in essential healthcare and agriculture certainly face a greater risk of social division in the event of extreme monopoly. It is therefore necessary that states regulate the Patenting of BNPs in a manner that ensures the poor section of society is not left behind. At the same time, the inventor and investor can reap the benefits of their labor and capital. This is done through the process of compulsory licensing, which ensures that the technology is available for the use of the public and that too at an affordable rate.

Although specific patent disputes on BNPs are scarce, comparable controversies exist in nanotechnology. For example, Arbutus Biopharma filed lawsuits against Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech over patented lipid nanoparticle technologies. Likewise, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Myriad Genetics (2013) ruling established that naturally occurring materials cannot be patented, a principle directly relevant to biologically derived nanoparticles [45].

3 Societal considerations

3.1 Public perception and acceptance of BNPs

BNPs have several advantages over chemically and physically generated nanoparticles. At the same time, the later ones tend to be more toxic, environmentally challenging, and unstable. They are, in most cases, inefficient in terms of energy and material use and require substantial capital investment [46]. BNPs, on the other hand, give a favourable option to these issues and are therefore considered superior [47].

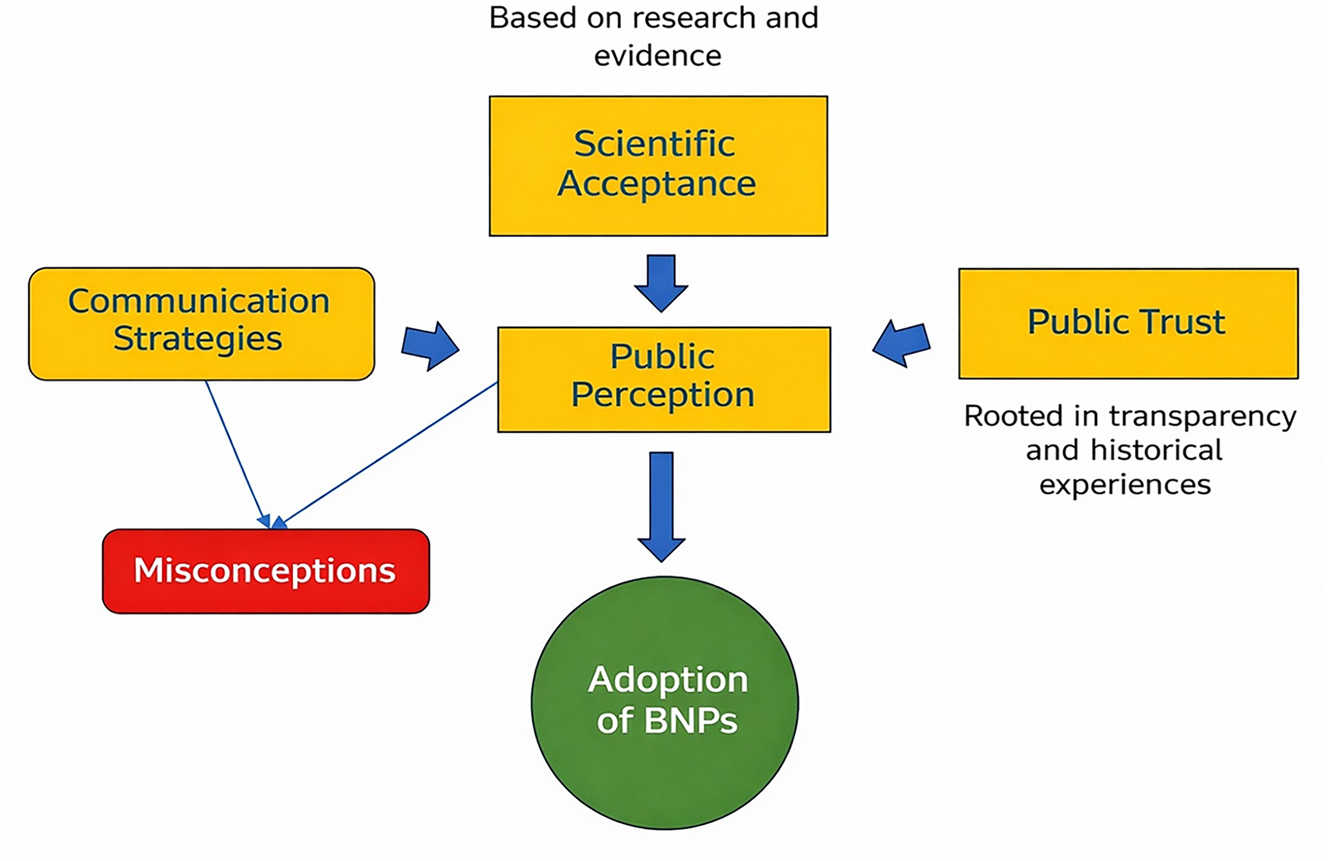

BNPs have established a significant presence within the nanotechnology community. However, various ethical concerns have arisen in the field of BNPs [48]. These moral concerns will be dealt with later in this article. At this juncture, it is essential to note that if these ethical concerns are not addressed, the general trend of accepting BNPs may face a significant challenge ahead. It is therefore necessary for the scientific community to address these public concerns. Apart from the above, certain misconceptions have also cropped up regarding BNPs and their use. Toxicity to the body, environmental harm, and disease caused by the use of BNPs in agriculture are among the critical misconceptions that need to be debunked. This can only be achieved if an efficient dialogue is established between the scientific community and the public at large, and the benefits of BNPs are efficiently advertised amongst the masses (Figure 2). The European Union mandates explicit nano-labeling in cosmetics and novel foods, requiring the term ‘(nano)’ after each ingredient name. In contrast, the U.S. FDA provides guidance encouraging detailed nanoparticle characterization but does not require consumer-level labeling. Other regions, such as Japan and China, follow similar advisory rather than mandatory disclosure approaches.

Public perception and acceptance model for biogenic nanoparticles (BNPs). Scientific acceptance directly affects the public’s perception of the issue. Public trust, influenced by transparency and historical experiences, also plays a crucial role. Effective communication strategies are pivotal in bridging gaps and mitigating misconceptions, ultimately leading to the successful adoption of BNPs.

Favourable public perception is of great importance to BNPs. Firstly, they are essential scientific tools, and their applicability benefits both humanity and the environment. Secondly, their development requires significant capital investment, and if these investments face commercial risk, further development of this field may be impeded.

3.2 Bridging the gap between developed and developing nations

Since the end of the Second World War, the entire globe has worked diligently to establish a universal commercial system, connecting countries through trade and the exchange of ideas. Globalization, therefore, is one of the most outstanding achievements of human civilization. Many international organisations have been established to ensure that this global commercial order operates smoothly and that every participant can express their concerns. The United Nations Organization, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization have played a vital role in this regard since their inception.

One of the key considerations of the global commercial order is that economic prosperity and development should not be restricted to the rich and developed nations. The development should be sustainable, and even the poorest countries must be assisted in their journey toward prosperity. The GATT and the WTO Agreement ensure that all members treat each other similarly and that domestic products and MFN products receive the same treatment.

There must be a constant sharing of technological knowledge between developed nations and their developing and underdeveloped counterparts, so that every human on this planet can witness the marvels that we, as a species, have achieved. As previously discussed, BNPs are a boon for the environment [47], and in the current era of global warming and climate change, we must employ every mitigating strategy to prevent or at least slow the rate of climate change. Environmental change is not a local phenomenon; it is a global issue. Pollution in one corner of the world has a dramatic effect on the climate in another part of the world, in the other hemisphere. Therefore, to ensure environmental restoration, developed countries must develop a plan to aid other countries in combating this scenario using BNPs.

3.3 Socioeconomic implications of BNPs

The advancement of technology is often linked with a reduction in employment numbers. However, BNPs paint a very different picture. They have, of late, been associated with job creation and prosperity. The entire BNP paradigm has created a demand for skilled technicians, researchers, scientists, managers, and investors. They have altogether made a new avenue for employment.

Additionally, BNPs have very far-reaching economic implications. The most significant of these can be observed in agriculture (Table 3). BNPs are now being utilized to enhance crop yield [49], improve disease and drought resistance [4], 50], and enable biofortification and nutrient enrichment. This is a bane for farmers and for populations deficient in nutrients.

Different biogenic nanoparticles and their beneficial effect on crops.

| Source | Residues | Nanoparticles | Beneficial effects | Treated plants | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catharanthus roseus | Leaves | ZnO | Affects higher seed germination and healthy seedling growth | Eleusine coracana | [51] |

| Triticum vulgare | Crop residues | Ag (coated with chitosan) | Higher seed germination and chlorophyll content | Triticum vulgare | [52] |

| Citrus aurantium | Peels | ZnO | Improved seed germination, increased fruit production. | Lycopersicon esculentum | [53] |

| Eucalyptus robusta | Leaves | Mn | Better seed germination and healthy seedling growth | Zea mays | [54] |

| Corymbia citriodora | Leaves | Mn | Cause higher seed germination and seedling growth | Zea mays | [55] |

| Olea europaea | Olive mill wastewater | MgS | Improved seed germination, healthy seedling growth, and antioxidant activity. | Pisum sativum | [56] |

| Lemna minor | Plant tissues | ZnO | Positive effects in vitro on biochemical traits, antioxidant activity | Olea | [57] |

| Punica granatum | Fruit pomace | Zn | Beneficial effects on physiological and biochemical traits, antioxidant activity | Zataria multiflora | [58] |

| Pistacia vera | Crop residues (shell) | Ag | Healthy plant growth and increases chlorophyll and carotenoid contents. | Solanum melongena | [59] |

| Lemna minor | Plant tissues | ZnO | Increased plant growth, photosynthetic pigments, and antioxidant activity | Zea mays | [60] |

| Cuminum cyminum | Seeds | TiO2 | Increase seed germination and seedling growth | Vigna radiata | [61] |

| Hypericum perforatum | Leaves | MnO2/perlite | Improvement in the physiological and metabolic responses of plant explants | Hypericum perforatum | [62] |

| Avicennia marina | Leaves | Cu | Increased seed germination and seedling growth, antioxidant activity, and chlorophyll content. | Triticum aestivum | [63] |

4 Regulatory frameworks

4.1 Current regulatory landscape for BNPs

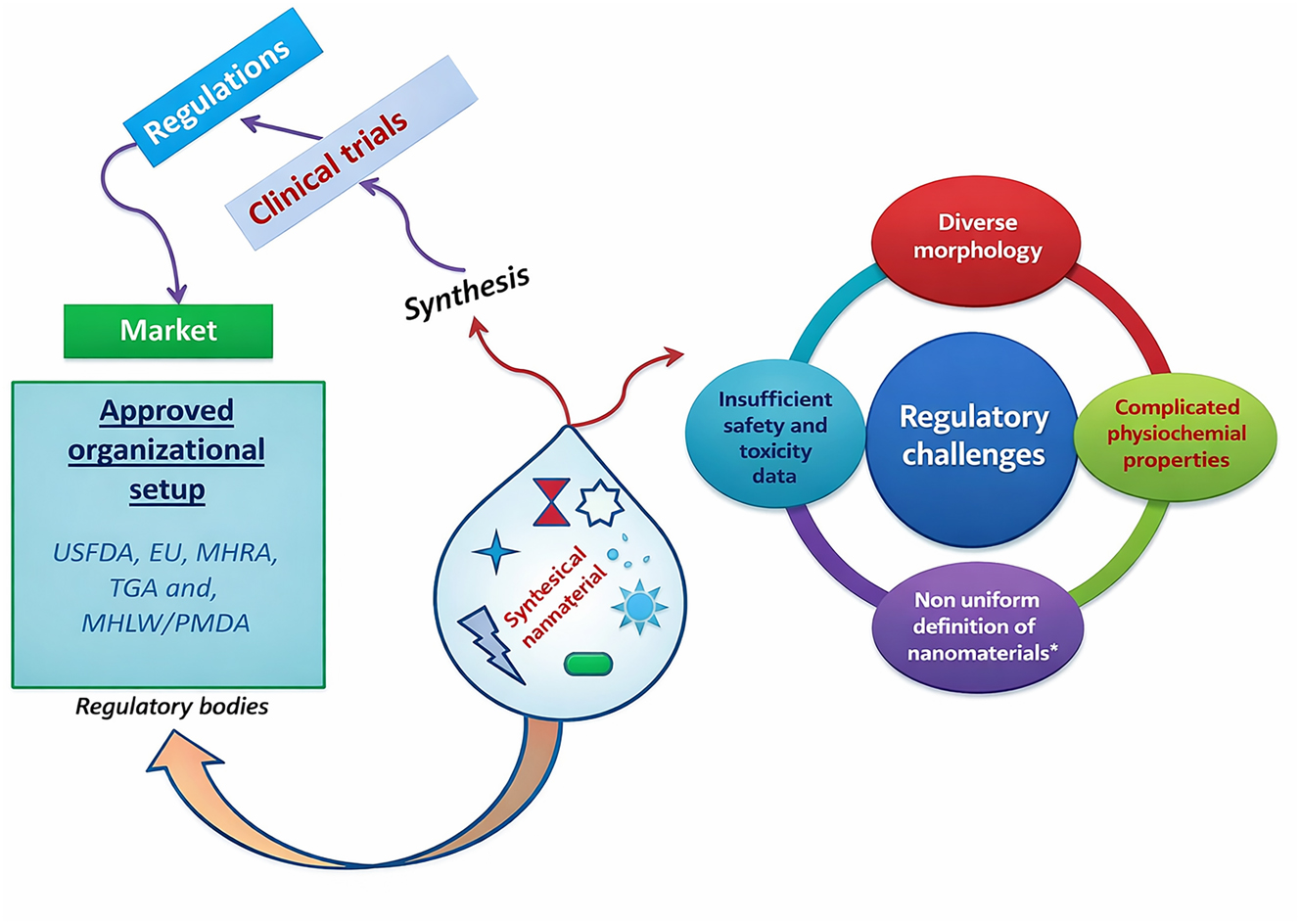

To understand the regulatory framework for BNPs, we must address the broader regulatory framework and marketing of Nanoparticles (Figure 3). Nanoparticles, as we know, have become an integral part of various industries, ranging from robotics and communication to agriculture and medicine. Therefore, they must be covered under an umbrella of regulations. Their economic importance makes their regulation a matter of utmost importance in the international context. It is pertinent to note that, at present, there is no holistic international framework (applicable to all countries alike) to regulate biogenic nanoparticles [63]. However, a few government bodies and groups have established rules and laws to define and regulate the use of nanoproducts [64]. We will provide a detailed examination of the regulatory frameworks for nanomaterials in various countries later in this article.

An overview of the paths of nanomaterial synthesis to its marketing.

4.2 Need for adaptive and stringent regulatory measures

Every citizen is considered to have a social contract with their state. For the smooth running of things, the state must fulfill its promise of general protection to its citizens and create a system of law and order, which in turn sends a signal of well-being to the masses. In modern times, with commerce having gone global, various states must come together to form an international system of law and order that can address specific issues uniformly worldwide. On this path, with the Inception of the United Nations, the international community has come together and worked hard to create a global order in which the fundamental human rights of each individual are protected. These Human rights can be personal, political, social, cultural, and economic. It is the duty of the United Nations and its members to uphold the definition of these rights and to protect their citizens from their violation. For this purpose, the UN has adopted various conventions to enumerate and define these rights. According to Article 13 of the UN Charter, “The contracting parties state their desire to promote: ‘economic and social advancement’ and ‘better standards of life’.” This forms the basis of the discussion surrounding the regulatory framework of newer technologies that impact the economy, development, health, and other aspects of our civilization. Articles 7 and 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) are also noteworthy in this regard [63].

Article 7 provides a deeper understanding of the denotation of the right to just and favourable working conditions, as discussed in other UN documents. “Favourable conditions of work” include terms of remuneration as well as “safe and healthy working conditions” [65]. Article 12 clearly and concisely addresses the issue of health. It is perhaps the strongest of all human rights instruments regarding the explicit right to protection against “occupational disease” and protection for “industrial hygiene.” The aforementioned international conventions and principles, therefore, impose a duty on states, both domestically and internationally, to formulate a robust regulatory framework for BNPs that is adaptable to emerging technological advancements. This is necessary because, over time, BNPs will not only affect individuals but also play a greater role in reshaping the economic and social paradigms of the world at large. There must be a mechanism to ensure that new technological advancements in BNPs are communicated globally efficiently and that both developed and developing nations do not fall behind in this regard.

4.3 Ethical considerations regarding the use of artificial intelligence in BNP development

The growth of Artificial intelligence has not been met by a proportional advancement in regulations and protocols, which poses a challenge regarding fairness in the development and deployment of BNPs as well [66]. The ethical and responsible deployment of advanced technologies, such as biogenic nanoparticles, necessitates a multidimensional approach that encompasses privacy protection, transparency, accountability, and robust governance structures. In the context of artificial intelligence (AI), privacy-preserving techniques, including differential privacy, federated learning, and homomorphic encryption, are crucial for safeguarding sensitive personal and health-related data throughout the research and application lifecycle [67]. Responsible deployment also necessitates transparency in methodological practices and decision-making processes, as well as active bias detection to ensure equity and mitigate risks to vulnerable populations. Inclusive stakeholder engagement, which involves experts, regulators, and the public, is crucial to building trust and promoting ethical oversight. The adoption of international regulatory standards, ethical codes of conduct, iterative risk assessments, and independent audits will ensure ongoing compliance with rapidly evolving policies and regulations. Integrating transparency, fairness, and privacy in AI development requires a comprehensive ethical framework that mitigates bias, promotes accountability, and respects data protection across global contexts. There is a need for routine audits, fairness-aware algorithms, clear documentation, diverse teams, and international collaboration to harmonize ethical AI standards for trustworthy and equitable AI systems [68].

4.4 Case studies of regulatory approaches in different regions

In this section, we will examine the various statutory and non-statutory measures taken by international organizations and multiple countries worldwide to establish a global framework for the regulation of Nanoparticles and their regulation in their respective territories [69].

4.4.1 Global level

Regulatory agencies

Technical Committee (TC) 113 of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC).

Technical Committee (TC) 229 of the International Standards Organization (ISO).

Key legislation or other instruments

ISO/TR 12885 (Technical Report): Health and safety practices in occupational settings relevant to nanotechnologies.

ISO/PRF TS 80004‐3 (Technical Specification): Nanotechnologies Part 3: Carbon nano‐objects.

ISO/TS27687 (Technical Specification): Terminology and definitions for nano‐objects: Nanoparticle, nanofiber, and nanoplates.

4.4.2 USA

Regulatory agencies

National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI).

National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

The Federal Nanotechnology Policy Coordination Group (NPCG).

National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST).

Key legislation or other instruments

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA).

Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA).

Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA).

Clean Air Act (CAA), Clean Water Act (CWA), Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA).

Significant new use rules (SNUR).

Nanomaterial Research Strategy (NRS), developed by the Office of Research and Development (ORD).

EPA issued SNUR for two nanoparticles (73 FR 65743).

Pre‐manufacturing notifications (PMN) for nanoscale materials.

Safe Chemical Act of 2010.

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA).

FDA Nanotechnology Task Force.

4.4.3 India

Regulatory agencies

Department of Science and Technology (DST).

National Nano Science and Technology Initiative (NSTI).

The Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS).

The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR).

Key legislation or other instruments

Notably, India has yet to develop any comprehensive statutory or regulatory instrument regarding nanoparticles.

4.4.4 European union

Regulatory agencies

European Chemicals Agency (ECHA).

European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (EGE).

Competent Authorities Sub Group on Nanomaterials (CASG Nano).

Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR).

Key legislation or other instruments

Regulation 1272/2008 of CLP.

2001/83/EC Directive.

Towards a European strategy for nanotechnology, COM (2004) 338.

First Implementation Report 2005–2007 of the Nano sciences and Nanotechnologies: An action plan for Europe 2005–2009.

COM (2005) 243: Nanotechnologies Action Plan.

Regulatory aspects of Nanomaterials, COM (2008).

4.4.5 UK

Regulatory agencies

National Nanotoxicology Research Centre.

Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

Council for Science and Technology (CST).

Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Nanotechnologies Leadership Group (NLG).

Key legislation or other instruments

The Second Government Research Report (December 2007) on Characterizing the potential risks posed by engineered nanoparticles.

Guidelines issued by the Health and Safety Executive on the safe handling of carbon nanotubes.

Supports EU initiatives; is encouraging a ‘case‐by‐case’ approach to evaluating the hazard and suitable use of discrete nanomaterials in food and food contact constituents.

An outline of the framework of current protocols affecting the growth and Advertising of Nanomaterials.

4.4.6 China

Regulatory agencies

National Steering Committee for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (NSCNN).

Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP).

State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA).

Key legislation or other instruments

Inventory of Existing Chemical Substances Manufactured or Imported in China (IECSC).

2003 regulations: Provision on the Environmental Administration of New Chemical Substances.

Measures on Environmental Management of New Chemical Substances.

From the above, it is amply clear that none of the regions currently has a specialized agency to deal with nanoparticles. Multiple agencies work in different areas, and it is through their internal coordination that nanoparticles are regulated. Even on the statutory front, legislatures worldwide have failed to devise a specific legal instrument in this regard. Nanoparticles are currently regulated primarily through amendments to existing statutes and administrative recommendations, and reports.

4.5 Recommendations for improving regulatory oversight

BNPs in particular and Nanotechnology in general are a novel phenomenon. As we saw earlier in this article, there is a lack of specific agencies and instruments, both globally and locally, to regulate nanoparticles. One of the main reasons is that nanoparticles have found roles in various aspects of human life, and it is impractical to develop a single framework that regulates all aspects of human civilization. Therefore, the current situation demands better coordination. The existing procedures for nanomaterials, such as REACH in the European Union, need to be integrated into existing frameworks [70]. Various standardization agencies need to develop a globally standardized testing protocol for nanomaterials and uniform guidelines to assess the environmental effects of nanoparticles and other safety concerns [71]. Safer principles need to be incorporated into the development of nanomaterials so that they can be engineered with lower toxicity without compromising functionality [72]. Additionally, stakeholders in the field of BNPs, including industrial leaders, regulators, and researchers, should participate in the decision-making process to promote transparency and foster consensus. Nevertheless, there is an excellent opportunity to integrate societal, legal, and ethical considerations into the regulatory framework, ensuring that the ethical and responsive governance of nanotechnology is addressed [73]. In India, a clear lack of a robust framework regulating BNPs is evident. To ensure optimal output, a regulatory framework for biogenic nanoparticles in India should involve a coordinated approach among key regulatory agencies. The Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) should develop technical standards addressing nanoparticle synthesis, quality control, and safety. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) must lead health risk assessments and safety evaluation protocols. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) should regulate the use of food and nutraceuticals, ensuring labelling and consumer protection. Stakeholder engagement, pilot regulatory testing, and legal enforcement mechanisms must be established to ensure compliance and address public health concerns [74]. International collaboration and alignment with global standards are crucial for robust governance and innovation.

5 Case study and real-world applications

In a recent study, Prakashkumar et al. [75] compared the efficacy of chemically synthesized (ZnO(A)) and biogenic (ZnO(B)) nanoparticles in terms of their antibacterial, antibiofilm, and anticancer activities. They reported statistically significant (p < 0.05) enhancement in antibacterial and anticancer activities of biogenic ZnO(B) compared with chemically synthesized ZnO(A). Chemical synthesis involved the co-precipitation method [76] using zinc nitrate precursor and sodium hydroxide (reducing agent). The precipitate obtained was washed with ethanol, dried, and then calcined for 2 h at 200 °C to obtain white-colored ZnO(A) NPs. Interestingly, the researchers opted to use termite mound extract to obtain ZnO(B) NPs. Firstly, they followed the cold extraction method. Partially ground termite mound soil, mixed with water in a 1:10 proportion, was shaker-incubated, followed by filtration and storage at 4 °C. Zn(NO3)2.6H2O was added to the extract, and the setup was stirred continuously to obtain the precipitate, which was further washed with ethanol and dried. The sample was then dried and calcinated as before.

Jakinala et al. [77] synthesized silver nanoparticles from insect wing extract and evaluated their antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. Kapadia et al. [78] reported effective synergistic action of nanoparticles combined with cefixime against Salmonella enteric typhi. Nayeri et al. [79] claimed that phyto-mediated silver nanoparticles prepared from Melissa officinalis aqueous and methanolic extracts are effective against infectious bacterial strains.

To substantiate the presence of ZnO and its crystalline structure, both types of NPs were subjected to an X-ray diffractometer. FTIR spectroscopy revealed the functional groups in the sample and extract. Furthermore, elemental analysis and morphological characterization were performed using dispersive X-ray spectroscopy equipped with scanning electron microscopy. The average particle size of NPs was determined using dynamic light scattering, and the active principle of the termite mound extract was identified using GC-MS analysis.

To test the inhibitory activities of synthesized NPs against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), the methodology outlined by Prakashkumar et al. [80] was followed. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction colorimetric assay was performed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of ZnO(A) and ZnO(B) NPs. The method outlined by Smith et al. [81] was followed to assess the apoptotic effects. Furthermore, Hoechst 33,342 staining [82] was performed to assess nuclear damage induced by apoptosis. All laboratory experiments were triplicated, and an ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple-range test was performed using SPSS.

The FTIR spectroscopy revealed the presence of metal oxides in ZnO(A) and ZnO(B) NP samples in accordance with previous reports of Khan et al. [83]. The hexagonal phase crystalline structure (wurtzite structure) of the NPs was revealed by X-ray diffraction analysis and corroborated with the findings of Gowdhami et al. [84]. Prakashkumar et al. [80] note that their biogenic NPs had drastically reduced size compared to ZnO(A). Both ZnO(A) and ZnO(B) had a rod shape, and the level of zinc (Zn) and oxygen (O) was higher in ZnO(B) NPs synthesized through the biogenic route. Furthermore, ZnO(B) was found to contain 14 volatile compounds, including D-limonene, which has been extensively studied for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and hypocholesterolemic effects [85].

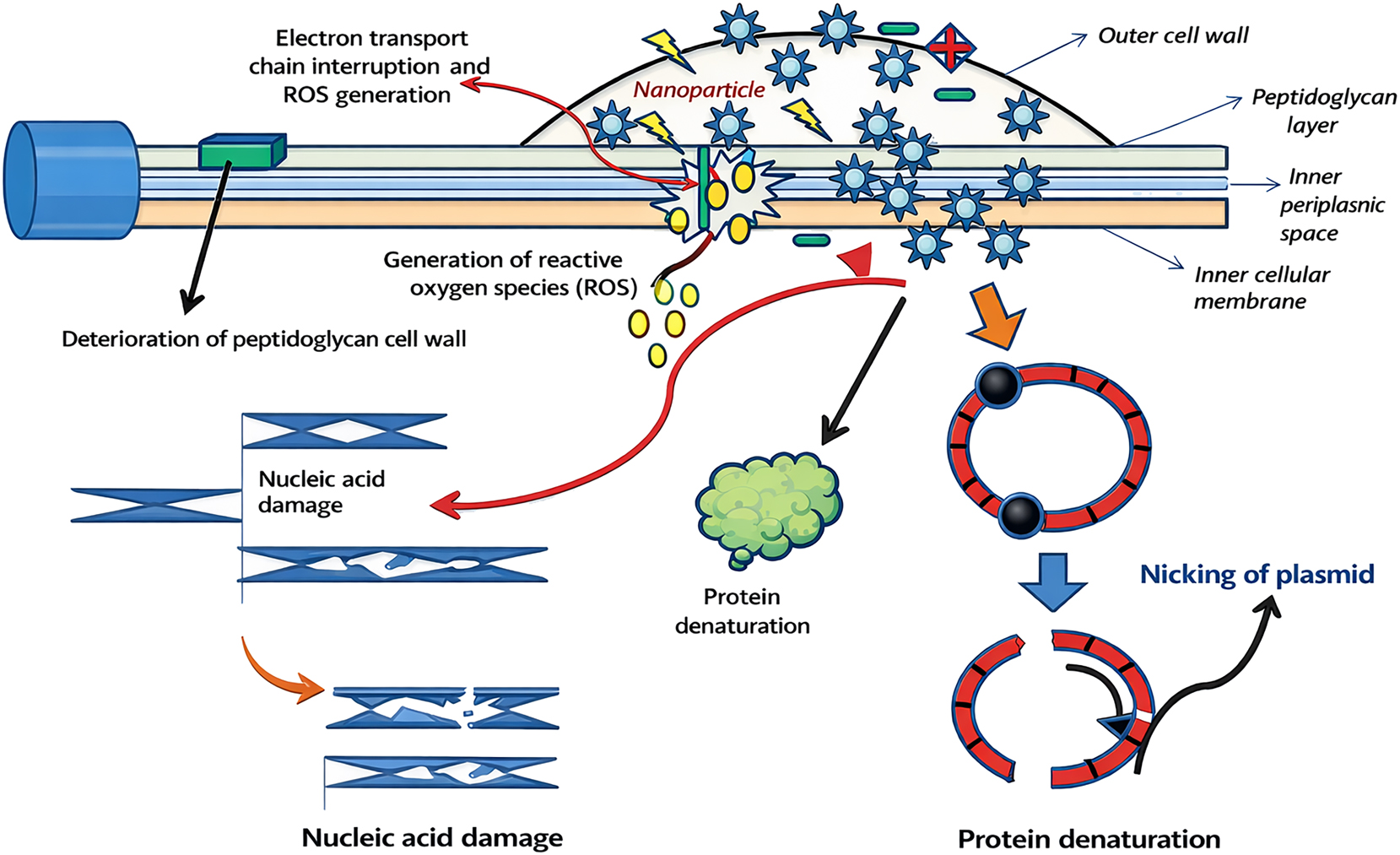

It is observed that biogenic nanoparticles exhibit antimicrobial activity in several cases (Figure 4). Compared with other biogenic nanoparticles, the antimicrobial activity of biogenic ZnO(B) was excellent against Gram-negative human pathogenic bacterial strains. This antimicrobial activity may be attributed to the release of Zn2+ or the generation of reactive oxygen species, leading to membrane damage and cell death. Importantly, ZnO(B) nanoparticles synthesized from termite mound extract showed the highest biofilm reduction, effectively eradicating ATCC MRSA 33591, with results significantly better than those of ZnO(A) nanoparticles synthesized by the NaOH-based method, as confirmed by light microscopy. Similarly, better results for ZnO(B) were observed in its cytotoxicity against A549 cells, and nanoparticles induced apoptosis-mediated cell death. Scaling this biosynthetic route presents challenges due to the limited and variable availability of termite-mound material. Sustainable alternatives, such as controlled microbial fermentation or plant cell cultures, may enable reproducible large-scale synthesis.

A graphical representation of biogenic nanoparticles showing antimicrobial activities.

In another recent study, Siddique et al. [86] reported that biogenic NPs could almost entirely decolorize dyes such as methanol blue and reactive black 5, and significantly reduce the chemical oxygen demand (COD), total dissolved solids (TDS), electrical conductivity, and pH of textile wastewaters. They envision BNPs as a potential green solution for treating dye-loaded textile wastewaters.

It is noteworthy that such research poses significant ethical and societal challenges, particularly regarding health and safety risks posed by the unpredictable behavior of nanoparticles in biological systems. The environmental impact of nanoparticle accumulation in ecosystems and the lack of comprehensive regulatory frameworks further complicate the safe development of these technologies. Researchers working in this field have an ethical responsibility to conduct thorough risk assessments and engage in transparent communication to address public concerns and ensure equitable access to the benefits of nanotechnology. Additionally, there is a need for interdisciplinary collaboration to navigate these challenges and integrate ethical considerations into the innovation process.

6 Future directions

As the field of biogenic nanoparticles (BNPs) continues to evolve, several critical areas require focused attention to ensure their responsible development and application. One of the most pressing needs is the establishment of comprehensive regulatory frameworks that can keep pace with the rapid advancements in BNP technology. These frameworks must be adaptive, allowing for the incorporation of new scientific insights as they emerge, and stringent enough to safeguard public health and the environment.

Moreover, interdisciplinary research must be encouraged, integrating nanotechnology, biology, ethics, and the social sciences. Such collaboration will enable a deeper understanding of the potential risks and benefits of BNPs, facilitating the development of guidelines that strike a balance between innovation and safety. In particular, further research is needed to assess the long-term environmental impacts of BNPs, ensuring that their integration across sectors does not lead to unintended ecological consequences.

Another critical direction is to enhance public engagement and education regarding BNPs. As public perception plays a crucial role in the acceptance and success of new technologies, transparent communication strategies are essential for their adoption. These strategies should focus on demystifying BNPs, addressing misconceptions, and building public trust by highlighting the benefits and addressing the ethical concerns associated with BNPs.

Finally, there is a need to bridge the gap between developed and developing nations in the field of BNPs. Efforts should be made to ensure that the advancements in BNP technology are accessible globally, particularly in regions that stand to benefit most from their applications in agriculture, healthcare, and environmental management. International cooperation and knowledge sharing will be key to achieving this goal, promoting sustainable development and global equity in the benefits of BNPs. Future research should address (i) long-term toxicological and ecotoxicological assessments of BNPs, (ii) development of standardized regulatory protocols, (iii) empirical analyses of public perception and ethics, and (iv) integration of BNP governance with sustainability frameworks.

7 Conclusions

The development and application of biogenic nanoparticles (BNPs) present both significant opportunities and challenges. Ethically, the scientific community must address concerns related to privacy, toxicity, biocompatibility, and public trust. Societally, ensuring that BNPs are accessible to all, including those in developing nations, is crucial for equitable advancement. BNPs contribute directly to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) through their roles in antimicrobial and anticancer therapies and indirectly to SDG 13 (Climate Action) by enabling cleaner production processes and environmental remediation technologies such as wastewater detoxification using biogenic catalysts.

The path forward involves a delicate balance between innovation and caution. By aligning the development of BNPs with societal values and ethical standards, we can harness their potential to drive progress in medicine, agriculture, and environmental conservation, while minimizing risks to human health and the environment. Harmonization of international standards for biogenic nanoparticles should be achieved by establishing a collaborative framework among agencies such as ISO, FDA, and ECHA. This can include developing unified risk assessment protocols, establishing baseline safety and quality standards, and facilitating mutual recognition of testing data. Regular updates, transparent data sharing, and alignment with global best practices could promote consistency. An overarching governing body or consortium should be established to oversee this process, ensuring flexibility for regional adaptations while maintaining core safety and environmental parameters. Such harmonization will reduce trade barriers, enhance safety, and accelerate innovation in Biogenic nanotechnology. Only by addressing these considerations can we ensure that the benefits of BNPs are realized in a manner that is both sustainable and just.

-

Funding information: This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

-

Author contributions: APS; Conceptualization, writing original draft, formal analysis, MA, FAN, and LMA; Writing-Review and editing, formal analysis and fund acquisition, HOS, AKS, SS, BPM, JB, and RS; review and editing, formal analysis and validation. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Murali, M, Gowtham, HG, Shilpa, N, Singh, BS, Mohammed, A, Sayyed, RZ, et al.. Zinc oxide nanoparticles prepared through microbial-mediated synthesis for therapeutic applications: a possible alternative for plants. Front Microbiol 2023;14:1227951. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1227951.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Alsulami, JA, Perveen, K, Alothman, MR, Al-Humaid, LA, Munshi, FM, Adawiyah, AR, et al.. Microwave-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by extracts of figure fruits and myrrh oleogum resin and their role in antibacterial activity. J King Saud Univ Sci 2023;35:102959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102959.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Daneshmand, S, Niazi, M, Fazeli-Nasab, B, Asili, J, Shiva, et al.. Solid lipid nanoparticles of Platycladus orientalis L. possessing 5-alpha reductase inhibiting activity for treating hair loss and hirsutism. J Med Plants By-prod 2024;1:233–46. https://doi.org/10.22034/jmpb.2023.364389.1634.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Shahbaz, M, Akram, A, Mehak, A, Haq, E, Fatima, N, Wareen, G, et al.. Evaluation of selenium nanoparticles in inducing disease resistance against spot blotch disease and promoting growth in wheat under biotic stress. Plants (Basel) 2023;12:761. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12040761.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Zaidi, N, Mir, MA, Chang, SK, Abdelli, N, Hasnain, SM, Ali Khan, MA, et al.. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products as emerging contaminants: environmental fate, detection, and mitigation strategies. Int J Environ Anal Chem 2025;1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2025.2484456.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Husain, S, Nandi, A, Simnani, FZ, Saha, U, Ghosh, A, Sinha, A, et al.. Emerging trends in advanced translational applications of silver nanoparticles: a progressing dawn of nanotechnology. J Funct Biomater 2023;14:47. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14010047.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Tasnim, A, Roy, A, Akash, SR, Ali, H, Habib, MR, Barasarathi, J, et al.. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: a green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential. Open Agric 2024;9:20220332. https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2022-0332.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Verma, C, Verma, DK, Berdimurodov, E, Barsoum, I, Alfantazi, A, Hussain, CM. Green magnetic nanoparticles: a comprehensive review of recent progress in biomedical and environmental applications. J Mater Sci 2024;59:325–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-023-09315-z.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Akhtar, N, Ilyas, N, Meraj, TA, Aboughadareh, AP, Sayyed, RZ, Mashwani, Z, et al.. Improvement of plant responses by nanobiofertilizer: a step towards sustainable agriculture. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2022;12:965. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12060965.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Sharma, S, Kumari, P, Shandilya, M, Thakur, S, Perveen, K, Sheikh, I, et al.. The combination of α-Fe2O3NP and Trichoderma sp. improves antifungal activity against Fusarium wilt. J Basic Microbiol 2025;65:e2400613. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.202400613.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Singh, RP, Handa, R, Manchanda, G. Nanoparticles in sustainable agriculture: an emerging opportunity. J Contr Release 2021;329:1234–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.051.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Francis, DV, Abdalla, AK, Mahakham, W, Sarmah, AK, Ahmed, ZF. Interaction of plants and metal nanoparticles: exploring its molecular mechanisms for sustainable agriculture and crop improvement. Environ Int 2024;179:108859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.108859.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Shati, AA, Al-dolaimy, F, Alfaifi, MY, Sayyed, RZ, Mansouri, S, Aminov, Z, et al.. Recent advances in using nanomaterials for portable biosensing platforms towards marine toxins application: up-to-date technology and future prospects. Microchem J 2023;195:109500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2023.109500.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Budamagunta, V, Shameem, N, Irusappan, S, Parray, JA, Thomas, M, Marimuthu, S, et al.. Microbial nanovesicles and extracellular polymeric substances mediate nickel tolerance and remediate heavy metal ions from soil. Environ Res 2022;219:114997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114997.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Zahedi, SM, Moharrami, F, Sarikhani, S, Padervand, M. Selenium and silica nanostructure-based recovery of strawberry plants subjected to drought stress. Sci Rep 2020;10:17672. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74273-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Seleiman, MF, Almutairi, KF, Alotaibi, M, Shami, A, Alhammad, BA, Battaglia, ML. Nano-fertilization as an emerging fertilization technique: why can modern agriculture benefit from its use? Plants (Basel) 2020;10:2. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10010002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Kummara, S, Patil, MB, Uriah, T. Synthesis, characterization, biocompatibility, and anticancer activity of green and chemically synthesized silver nanoparticles–a comparative study. Biomed Pharmacother 2016;84:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Wypij, M, Jędrzejewski, T, Trzcińska-Wencel, J, Ostrowski, M, Rai, M, Golińska, P. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles: antibacterial and anticancer activities, biocompatibility, and analyses of surface-attached proteins. Front Microbiol 2021;12:632505. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.632505.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Hosny, S, Gaber, GA, Ragab, MS, Ragheb, MA, Anter, M, Mohamed, LZ. A comprehensive review of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs): synthesis strategies, toxicity concerns, biomedical applications, AI-Driven advancements, challenges, and future perspectives. Arab J Sci Eng 2025:1–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09951-w.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Thakkar, KN, Mhatre, SS, Parikh, RY. Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2010;6:257–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2009.07.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Rao, B, Tang, RC. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial activities using aqueous Eriobotrya japonica leaf extract. Adv Nat Sci Nanosci Nanotechnol 2017;8:015014. https://doi.org/10.1088/2043-6254/aa5983.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Phanjom, P, Ahmed, G. Effect of different physicochemical conditions on the synthesis of silver nanoparticles using fungal cell filtrate of Aspergillus oryzae (MTCC No. 1846) and their antibacterial effect. Adv Nat Sci Nanosci Nanotechnol 2017;8:045016. https://doi.org/10.1088/2043-6254/aa9349.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Yin, K, Wang, Q, Lv, M, Chen, L. Microorganism remediation strategies towards heavy metals. Chem Eng J 2019;360:1553–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.10.226.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Srinath, BS, Namratha, K, Byrappa, KJAS. Eco-friendly synthesis of gold nanoparticles by Bacillus subtilis and their environmental applications. Adv Sci Lett 2018;24:5942–6. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2018.12219.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Tsekhmistrenko, SI, Bityutskyy, VS, Tsekhmistrenko, OS, Horalskyi, LP, Tymoshok, N, Spivak, MY. Bacterial synthesis of nanoparticles: a green approach. Biosyst Divers 2020;28:9–17. https://doi.org/10.15421/012002.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Patil, S, Chandrasekaran, R. Biogenic nanoparticles: a comprehensive perspective on synthesis, characterization, application, and its challenges. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 2020;18:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43141-020-00081-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Eming, SA, Martin, P, Tomic-Canic, M. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:265sr6. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Kalishwaralal, K, Deepak, V, Ramkumarpandian, S, Nellaiah, H, Sangiliyandi, G. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by the culture supernatant of Bacillus licheniformis. Mater Lett 2008;62:4411–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2008.06.051.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Sheikh, FA, Majeed, S, Beigh, MA, editors. Interaction of Nanomaterials with Living Cells. Singapore: Springer; 2023.10.1007/978-981-99-2119-5Suche in Google Scholar

30. Baran, A. Nanotechnology: legal and ethical issues. Eng Manag Prod Serv 2016;8:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1515/emj-2016-0024.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Schulte, PA, Salamanca-Buentello, F. Ethical and scientific issues of nanotechnology in the workplace. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2007;12:1319–32. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-81232007000500028.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. King, NM. Nanomedicine first-in-human research: challenges for informed consent. J Law Med Ethics 2012;40:823–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-720x.2012.00712.x.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Maynard, AD, Warheit, DB, Philbert, MA. The new toxicology of sophisticated materials: nanotoxicology and beyond. Toxicol Sci 2011;120:S109–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfq372.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Haugen, HM. Alternative IP theories. In: The Intellectual Property Rights Post-Pandemic World. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2023:75–94 pp.10.4337/9781803922744.00010Suche in Google Scholar

35. Gordon, WJ. A property right in self-expression: equality and individualism in the natural law of intellectual property. Yale Law J 1993;102:1533–609. https://doi.org/10.2307/796978.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Henricson, C. Morality and public policy. Bristol: Policy Press; 2016.10.46692/9781447323846Suche in Google Scholar

37. Shavell, S, Van Ypersele, T. Rewards versus intellectual property rights. J Law Econ 2001;44:525–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/323386.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Stengel, D. Intellectual property in philosophy. Archiv für Rechts- und Sozialphilos 2004;90:20–50.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Sunder, M. Property in personhood. UC Davis Leg Stud Res Paper 2004;6.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Helfer, LR. Regime shifting: the TRIPS agreement and new dynamics of international intellectual property lawmaking. Yale J Int Law 2004;29:1.10.2139/ssrn.459740Suche in Google Scholar

41. Chen, ZZJ, Zhang, J. Types of patents and driving forces behind the patent growth in China. Econ Modell 2019;80:294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.11.020.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Singh, KK. Legal issues in nanotechnology. In: Role of plant growth promoting microorganisms in sustainable agriculture and nanotechnology. Duxford, United Kingdom: Elsevier; 2019:107–20 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-817004-5.00007-5Suche in Google Scholar

43. Owoeye, O, Olatunji, O, Faturoti, B. Patents and the trans-Pacific partnership: how TPP-style intellectual property standards may exacerbate the access to medicines problem in the East African Community. Int Trade J 2017;33:197–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853908.2017.1352377.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Afri, RA. Nanotechnology industry scenario of intellectual property rights. In: Intellectual property issues in nanotechnology. London, UK: Taylor and Francis Group, LLC; 2021:345–58 pp.10.1201/9781003052104-23Suche in Google Scholar

45. Bakshi, AM. Gene patents at the supreme court: association for molecular pathology v. myriad genetics. J L Biosci 2014;1:183–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jlb/lsu012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Ingle, GA, Gade, A, Pierrat, S, Sonnichsen, C, Rai, M. Mycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Fusarium acuminatum and its activity against some human pathogenic bacteria. Curr Nanosci 2008;4:141–4. https://doi.org/10.2174/157341308784340804.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Rai, M, Gade, A, Yadav, A. Biogenic nanoparticles: an introduction to what they are, how they are synthesized, and their applications. In: Rai, M, Duran, N, editors. Metal Nanoparticles in Microbiology. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011:1–14 pp.10.1007/978-3-642-18312-6_1Suche in Google Scholar

48. Shajar, F, Saleem, S, Mushtaq, NU, Shah, WH, Rasool, A, Padder, SA, et al.. Regulatory and ethical issues raised by the utilization of nanomaterials. In: Interaction of nanomaterials with living cells. Singapore: Springer; 2023:899–924 pp.10.1007/978-981-99-2119-5_31Suche in Google Scholar

49. Faridvand, S, Amirnia, R, Tajbakhsh, M, Enshasy, HE, Sayyed, RZ. The effect of foliar application of magnetic water and nano, organic, and chemical fertilizers on phytochemical and yield characteristics of different landraces of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare mill). Horticulturae 2021;7:475. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110475.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Nasab, BF, Sayyed, RZ, Ahmad, RP, Rahmani, F. Biopriming and nanopriming: green revolution wings to increase plant yield, growth, and development under stress conditions and forward dimensions. In: Singh, HB, Anukool, V, Sayyed, RZ, editors. Nanofertilizers: sustainable agriculture. Singapore: Springer; 2021:623–55 pp.10.1007/978-981-16-1350-0_29Suche in Google Scholar

51. Mishra, D, Chitara, MK, Negi, S, Singh, JP, Kumar, R, Chaturvedi, P. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles via leaf extracts of Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don and their application in improving seed germination potential and seedling vigor of Eleusine coracana (L.) gaertn. Adv Agric 2023;2023:7412714–1. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/7412714.Suche in Google Scholar

52. Mondéjar-López, M, López-Jimenez, AJ, Ahrazem, O, Gómez-Gómez, L, Niza, E. Chitosan-coated biogenic silver nanoparticles from wheat residues as green antifungal and nanopriming agents in wheat seeds. Int J Biol Macromol 2023;225:964–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.11.139.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Punitha, VN, Vijayakumar, S, Alsalhi, MS, Devanesan, S, Nilavukkarasi, M, Vidhya, E, et al.. Biofabricated ZnO nanoparticles as vital components for agriculture revolutionization–a green approach. Appl Nanosci 2023;13:5821–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-023-02830-1.Suche in Google Scholar

54. Gonçalves, JPZ, Seraglio, J, Macuvele, DLP, Padoin, N, Soares, C, Riella, HG. Green synthesis of manganese-based nanoparticles mediated by Eucalyptus robusta and Corymbia citriodora for agricultural applications. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2022;636:128180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.128180.Suche in Google Scholar

55. Hamimed, S, Chamekh, A, Slimi, H, Chatti, A. How olive mill wastewater could turn into valuable bionanoparticles in improving germination and soil bacteria. Ind Crops Prod 2022;188:115682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115682.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Regni, L, Del Buono, D, Micheli, M, Facchin, SL, Tolisano, C, Proietti, P. Effects of biogenic ZnO nanoparticles on growth, physiological, biochemical traits, and antioxidants in the olive tree in vitro. Horticulturae 2022;8:161. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8020161.Suche in Google Scholar

57. Bahmanzadegan, A, Tavallali, H, Tavallali, V, Karimi, MA. Variations in biochemical characteristics of Zataria multiflora in response to foliar application of zinc nano complex formed on pomace extract of Punica granatum. Ind Crops Prod 2022;187:115369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115369.Suche in Google Scholar

58. Khan, M, Khan, AU, Moon, IS, Felimban, R, Alserihi, R, Alsanie, WF, et al.. Synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles from the seed coat waste of pistachio (Pistacia vera) and their effect on the growth of eggplant. Nanotechnol Rev 2021;10:1789–800. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2021-0112.Suche in Google Scholar

59. Del Buono, D, Di Michele, A, Costantino, F, Trevisan, M, Lucini, L. Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using a novel plant extract: application to enhance physiological and biochemical traits in maize. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2021;11:1270. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11051270.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Mathew, SS, Sunny, N, Shanmugam, V. Green synthesis of anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Cuminum cyminum seed extract; effect on mung bean (Vigna radiata) seed germination. Inorg Chem Commun 2021;126:108485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2021.108485.Suche in Google Scholar

61. Jafarirad, S, Kosari Nasab, M, Tavana, RM, Mahjouri, S, Ebadollahi, R. Impacts of manganese bio-based nanocomposites on phytochemical classification, growth, and physiological responses of Hypericum perforatum L. shoot cultures. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021;209:111841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111841.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Essa, HL, Abdelfattah, MS, Marzouk, AS, Shedeed, Z, Guirguis, HA, El-Sayed, MM. Biogenic copper nanoparticles from Avicennia marina leaves: impact on seed germination, detoxification enzymes, chlorophyll content, and uptake by wheat seedlings. PLoS One 2021;16:e0249764. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249764.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Chávez-Hernández, JA, Velarde-Salcedo, AJ, Navarro-Tovar, G, Gonzalez, C. Safe nanomaterials: from their use, application, and disposal to regulations. Nanoscale Adv 2024;6:339–53. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3na00632a.Suche in Google Scholar

64. Jain, AR. Nanomaterials in food and agriculture: an overview of their safety concerns and regulatory issues. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017;57:297–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2015.1060797.Suche in Google Scholar

65. Feitshans, IL. Global health impacts of nanotechnology law: a tool for stakeholder engagement. Boca Raton: Jenny Stanford Publishing; 2018.10.1201/9781351134477Suche in Google Scholar

66. Minhans, K, Sharma, S, Sheikh, I, Alhewairini, SS, Sayyed, R. Artificial intelligence and plant disease management: an agro-innovative approach. J Phytopathol 2025;173:e70084. https://doi.org/10.1111/jph.70084.Suche in Google Scholar

67. Radanliev, P, Santos, O, Brandon-Jones, A, Joinson, A. Ethics and responsible AI deployment. Front Artif Intell 2024;7:1356789. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2024.1356789.Suche in Google Scholar

68. Radanliev, P. AI ethics: integrating transparency, fairness, and privacy in AI development. Appl Artif Intell 2025;39:2343201. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2025.2463722.Suche in Google Scholar

69. Ali, F, Neha, K, Parveen, S. Current regulatory landscape of nanomaterials and nanomedicines: a global perspective. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2023;80:104118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2022.104118.Suche in Google Scholar

70. Isibor, PO, Devi, G, Enuneku, AA. Environmental nanotoxicology: combatting the minute contaminants. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2024.10.1007/978-3-031-54154-4Suche in Google Scholar

71. Rodríguez-Ibarra, C, Déciga-Alcaraz, A, Ispanixtlahuatl-Meráz, O, Medina-Reyes, EI, Delgado-Buenrostro, NL, Chirino, YI. International landscape of limits and recommendations for occupational exposure to engineered nanomaterials. Toxicol Lett 2020;322:1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2020.01.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

72. Eom, HJ, Choi, J. p38 MAPK activation, DNA damage, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis as mechanisms of toxicity of silver nanoparticles in Jurkat T cells. Environ Sci Technol 2010;44:8337–42. https://doi.org/10.1021/es1020668.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Thu, NT, Patra, S, Pranudta, A, Nguyen, TT, El-Moselhy, MM, Padungthon, S. Desalination of brackish groundwater using a self-regeneration hybrid ion exchange and reverse osmosis system (HSIX-RO). Desalination 2023;550:116378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2023.116378.Suche in Google Scholar

74. Singh, S. Nanomaterial toxicity and regulatory framework. Significances Bioeng Biosci 2025;7:119902.Suche in Google Scholar

75. Prakashkumar, N, Pugazhendhi, A, Brindhadevi, K, Garalleh, HA, Garaleh, M, Suganthy, N. Comparative study of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized through biogenic and chemical routes with reference to antibacterial, antibiofilm, and anticancer activities. Environ Res 2023;220:115136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.115136.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

76. Nejati, K, Rezvani, Z, Pakizevand, R. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and investigation of the ionic template effect on their size and shape. Int Nano Lett 2011;1:75–81. https://doi.org/10.53709/INL.2011.1.2.75.Suche in Google Scholar

77. Jakinala, P, Lingampally, N, Hameeda, B, Sayyed, RZ, Khan, MY, Elsayed, EA, et al.. Silver nanoparticles from insect wing extract: biosynthesis and evaluation for antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. PLoS One 2021;16:e0241729. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241729.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

78. Kapadia, C, Lokhandwala, F, Patel, N, Elesawy, BH, Sayyed, RZ, Alhazmi, A, et al.. Nanoparticles combined with cefixime as an effective synergistic strategy against Salmonella enterica typhi. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021;28:4164–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.05.032.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

79. Nayeri, FD, Mafakheri, S, Mirhosseini, M, Sayyed, R. Phyto-mediated silver nanoparticles via Melissa officinalis aqueous and methanolic extracts: synthesis, characterization, and biological properties against infectious bacterial strains. Int J Adv Biol Biomed Res 2021;9:270–85. Available from: http://www.ijabbr.com/article_245059.html.10.21203/rs.3.rs-24102/v1Suche in Google Scholar

80. Prakashkumar, N, Asik, RM, Kavitha, T, Archunan, G, Suganthy, N. Unveiling the anticancer and antibiofilm potential of catechin overlaid reduced graphene oxide/zinc oxide nanocomposites. J Cluster Sci 2022;33:2813–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-021-02196-8.Suche in Google Scholar

81. Smith, SM, Ribble, D, Goldstein, NB, Norris, DA, Shellman, YG. A simple technique for quantifying apoptosis in 96-well plates. Methods Cell Biol 2012;112:361–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-408143-7.00019-2.Suche in Google Scholar

82. Crowley, LC, Marfell, BJ, Waterhouse, NJ. Analyzing cell death by nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2016;2016. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot087205.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Khan, MF, Ansari, AH, Hameedullah, AE, Husain, FM, Zia, Q, Lim, YS, et al.. Sol-gel synthesis of thorn-like ZnO nanoparticles endorsing mechanical stirring effect and their antimicrobial activities: potential role as nano-antibiotics. Sci Rep 2016;6:20819. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20819.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84. Gowdhami, B, Jaabir, M, Archunan, G, Suganthy, N. Anticancer potential of zinc oxide nanoparticles against cervical carcinoma cells synthesized via biogenic route using aqueous extract of Gracilaria edulis. Mater Sci Eng C 2019;103:109840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.109840.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

85. Veena, R, Srimathi, K, Panigrahi, PN, Subramaniam, GA. Comparative approach for the synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles: green and chemical method. Int J Tech Res Appl 2016;38:27–31.Suche in Google Scholar

86. Siddique, K, Shahid, M, Shahzad, T, Mahmood, F, Nadeem, H, Rehman, MS, et al.. Comparative efficacy of biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by Pseudochrobactrum sp. C5 and chemically synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles for catalytic degradation of dyes and wastewater treatment. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021;28:28307–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-12576-9.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy