Green fabrication of γ- Al2O3 bionanomaterials using Coriandrum sativum plant extract and its photocatalytic and antibacterial activity

-

Awais Ahmad

, Muhammad Sufyan Javed

, Mariam Khan

, Ikram Ahmad

, Mohamed Sheikh

Abstract

Water contamination presents a pressing concern, particularly in emerging and struggling nations. Addressing this challenge, photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants emerges as a potent strategy for environmental preservation. This research introduces an innovative, environmentally benign synthesis method for green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles, harnessing Coriandrum sativum plant extract. Optical analysis through UV and visible absorbance unveils distinct Al3+ transitions, validating a 4.6 eV bandgap. Structural investigation via X-ray diffraction (XRD) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) reveals cubic crystalline structures with spherical morphology, while Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) elucidate nanoparticle-surface interactions and the aggregation of plant-derived molecules. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) explores aluminum valence states on oxygen surfaces, illuminating reaction mechanisms, bonding, and binding energies. Green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles exhibit robust efficacy against Gram-negative Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. Under UV irradiation, the nanoparticles effectively degrade malachite green (MG) dye, conforming to pseudo-first-order kinetics, accomplishing an impressive 94 % degradation efficiency for the toxic organic dye, facilitated by plant bio-molecule-induced light absorption and recombination of charged particles. This process influences catalytic potential, minimizing unwanted yield and promoting robust electron activity. The green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles exhibit outstanding antibacterial susceptibility and catalytic performance against industrial dye pollutants, might find their applications in sustainable practices and biological innovation, thereby holding significant promise for advancing environmental stewardship and technological progress.

1 Introduction

The introduction of poisonous and nonbiodegradable substances into the aquatic system has deteriorated the aquatic environment, which has led to the expansion of the human population, the substantial industrialization of the economy, and the enhancement of farming practices [1], 2]. The textile industry, which is one of the major consumers of water is responsible for producing effluents which are very colourful and quite intricate. About 100,000 different dyes may be purchased commercially, and over 7,105 tonnes of dyestuff are manufactured annually [3], 4]. Dye products can be broken down into a diverse collection of individual chemical structures. It is not ideal for discharging colourful effluents into water bodies because the degradation of dyes produces byproducts that are toxic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic [5], 6]. These dyes have a long shelf life in wastewater because of their stability. It is not possible to recycle them without proper processing [6]. Malachite green (MG) dye is exceedingly poisonous to diverse aquatic and terrestrial organisms. The textile, leather, cotton, wool, and paper industries are only some sectors that extensively use the essential dye known as MG [7]. It has a detrimental effect on the surrounding habitat. It poses a significant number of risks to the general population’s health, besides issues for the environment. MG is highly cytotoxic to mammalian cells and has the potential to cause cancer in a variety of animal tissues, including the thyroid and liver. It causes congenital disabilities in rats and mice and damage to the liver, growth and fertility rates, kidney, heart, eyes, and lungs. Furthermore, it is teratogenic [8]. Chemical oxidation, coagulation, ozonolysis, RO, UV treatment, adsorption, and photocatalysis are common techniques for eliminating dyes [8], [9], [10]. In recent years, photocatalytic degradation of organic molecules has emerged as the technology that is both the most effective and the most efficient in terms of cost when mitigating the detrimental environmental effects of toxic pollutants and hazardous wastes in aqueous media. Recovery of the adsorbent material, ease of operation, and reduced initial development expenses are among the key advantages of photocatalytic degradation in minimizing environmental damage caused by water pollution [11]. Many metal oxides, such as CuO, Co3O4, Fe2O3, G3N4, ZnO, Al2O3 and TiO2 are photocatalysts for wastewater treatment [6], 12]. Because of its applicability in a wide number of fields, such as composite materials, catalysts, surface protective coatings, and fire retardants, Al2O3 has garnered much attention among these metal oxides. The methods used in synthesizing metal oxide NPs are sol-gel, green synthesis, template assist, CVD, chemical precipitation, and electrochemical [13], 14]. Among them, green synthesis is in eco-friendly and cost-effective approach which facilitates the synthesis of many metal oxides. Some examples of these plant-based metal oxides include ZnO, TiO2, CuO, Fe2O3, V2O5 and Co3O4 etc. [15], [16], [17]. As a consequence of this, biogenic synthesis are recognized as an excellent and risk-free source for the production of nanoparticles composed of metal and metal oxide. In addition, plant leaf extract acts as both a reducing agent and stabilizing agent during the production of nanoparticles, making it a very useful ingredient. Coriandrum sativum, commonly referred to as coriander or cilantro, is an aromatic herb that falls under the botanical family Apiaceae. C. sativum has a long history of cultivation and utilization in the Mediterranean region due to its unique culinary, medicinal, and aromatic properties. The herbaceous plant under consideration is distinguished by its fragile green leaves, frequently employed as a decorative element in various culinary preparations. Additionally, its desiccated seeds impart a distinctive taste to numerous global cuisines. In addition to its usage in cooking, C. sativum is highly esteemed for its diverse range of bioactive constituents, encompassing flavonoids, phenolic compounds, terpenoids, and essential oils [18], 19]. C. sativum has garnered attention in both traditional medicine and modern scientific research due to its possession of antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and neuroprotective properties. The potential utilization of C. sativum as a bio-reducing and capping agent in nanoparticle synthesis is particularly intriguing. Numerous compounds found in the plant, including flavonoids, terpenoids, glycosides, tannins, phenolic substances, and alkaloids, have been shown in earlier research to have stabilising and reducing properties. The existence of these bioactive compounds facilitates the environmentally friendly production of nanoparticles with precise dimensions and configurations. The extract derived from C. sativum possesses inherent reducing properties that effectively enable the transformation of metal ions into nanoparticles. Additionally, this extract serves the purpose of stabilizing the structure of the nanoparticles, thereby presenting a viable and eco-friendly alternative to conventional methods employed for nanoparticle synthesis. Furthermore, the aforementioned plant is cheap and widely available [20], 21].

In current study, the plant extract of C. sativum is used to synthesize γ-Al2O3 for the photocatalytic degradation of MG dye and antibacterial activity of Escherichia coli, and as far as we are aware, Corriandrum sativum leaf extract has not yet been used in the synthesis of γ-Al2O3. Also, this article investigates the diverse characteristics of E. coli, examining its functional adaptability, complex molecular structure, and implications in clinical settings. The complex nature of E. coli, ranging from its fundamental genetic characteristics to the emerging concerns surrounding antimicrobial resistance, is explored in this study.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

Coriandrum sativum leaves and aluminium nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3. 9H2O = 99 % purity, Sigma-Aldrich) were used to synthesize the green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles. The organic dye pollutants of Malachite green dye were procured from Sigma Aldrich. All the chemicals were treated from double-distilled water, and no chemical modifications were attained for synthesizing Al2O3 nanoparticles.

2.2 Preparation of C. sativum leaf extract

The collected fresh C. sativum leaves (5 g) were washed, and impurities were removed by tap water. The cleaned fresh leaves are soaked in 50 mL double distilled water for 10 min, and after that, the leaves are crushed by mortar and pestle. The crushed leaf extract was filtered by white cotton cloth, and filtered thick leaf extract was diluted with 50 mL double distilled water for further use.

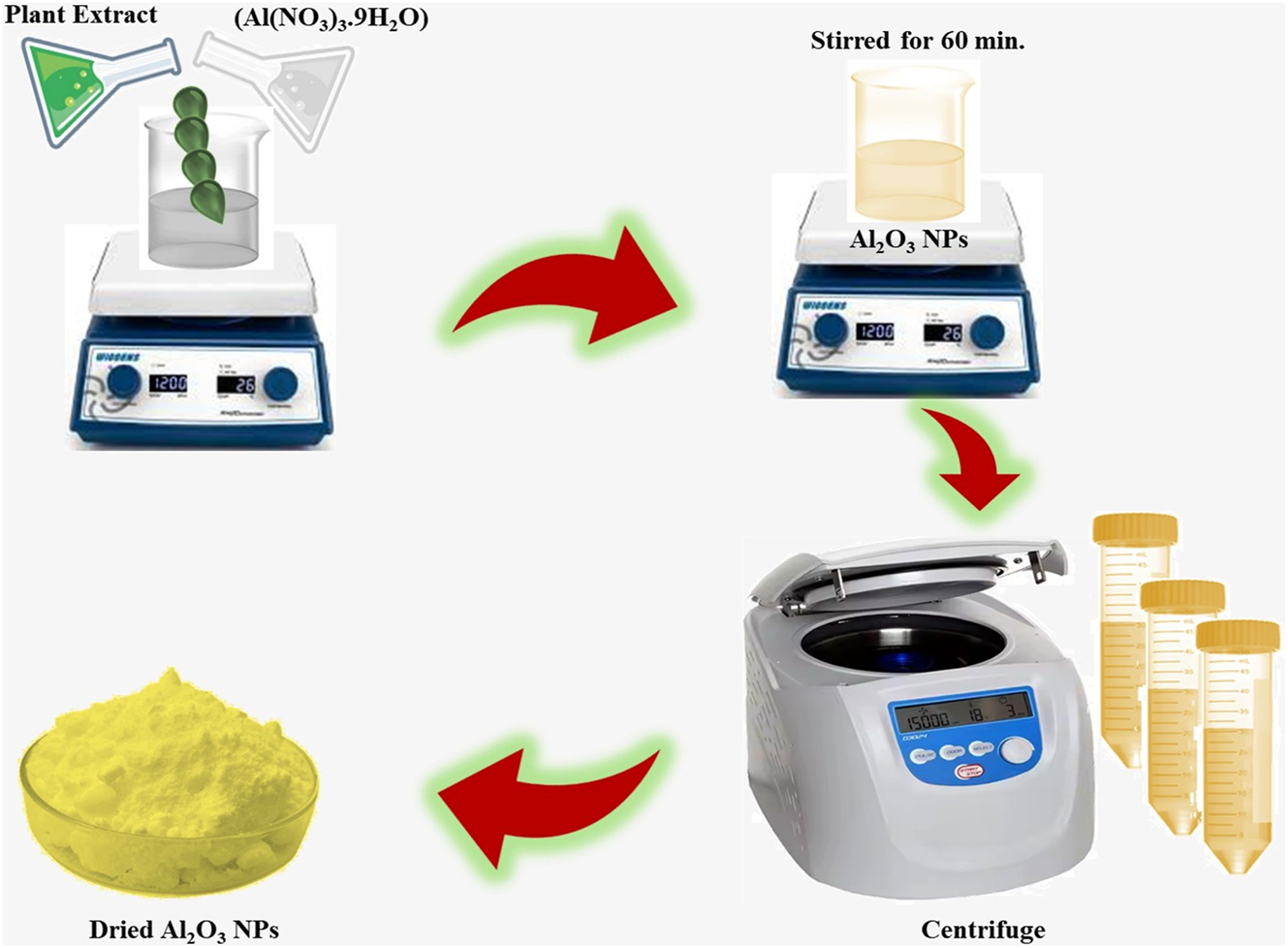

2.3 Synthesis of green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles

Aluminium nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3. 9H2O) and C. sativum leaves are involved in the process of green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles. 0.1 M aluminium nitrate nonahydrate was dissolved in 90 mL distilled water and combined with 10 mL C. sativum leaf extract for 60 min using a magnetic stirrer condition at 750 rpm. The resultant solution has shown the yellow colour, indicating the formation of aluminium nanoparticles. The solution was stored in dark conditions for 6 h. After 6 h, the combined solution was precipitated and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The same centrifugation process was triplicated to eliminate the foreign content from the aluminum oxide nanoparticles. These precipitates were washed with acetone and filtered using Whatman No.1 filter paper (Figure 1). The obtained precipitate was dried at 150 °C, and collected lite yellow powder was processed for further evaluation [22], 23].

Possible mechanism for the synthesis of Al2O3 nanoparticles using the Coriandrum sativum leaf extract.

2.4 Characterization of green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles

The synthesized materials’ optical and functional group information were analyzed from a UV-visible spectrometer (Simadzu-2700, Japan) and FTIR spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer). Structural and phase identity was measured from X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku-Japan). Surface entity and material compositions were demonstrated from field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM- Carl Zeiss, Germany), transmission electron microscopy (TEM-Titan, Germany) and energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX). Surface binding and valency of the synthesized materials were found from X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS-Physical electronics, USA).

2.5 Photocatalytic dye degradation of malachite green dye experiment

Photocatalytic dye degradation activity of Al2O3 nanoparticles was examined against malachite green dye (30 ppm) under UV-light irradiation. 10 mg of green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles were immersed in malachite dye solution using a magnetic stirrer, and it was placed in dark condition for 40 min to establish the adsorption–desorption state. UV-light irradiation is used as a light source of photocatalytic activity. The combined solution is positioned in a direct UV-light place without any hindrances. The UV-light irradiations help to degrade the dye’s benevolence and decrease the gap between the contact of electrons. The dye dissociation was evaluated by investigating the sample after every 10 min. The collected pollutants were centrifuged for 5,000 rpm to evacuate the catalyst from the dye solution, and it was measured by UV-visible spectroscopy. The dye degradation efficiency was calculated by the absorbance intensity of malachite green dye using eq. (1) [24].

2.6 Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles was inspected against E. coli (ATCC 8739-gram-negative). The good diffusion method was used to determine the bacterial resistivity of the green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles. The bacterial culture (106 CFU/mL) was introduced into the nutrient broth for one day of incubation. The sterilized petri plates were filled with Muller–Hinton agar medium and incubated overnight to attain the optimum growth surface of petri plates. After the developed bacterial culture was swabbed onto the sterilized Petri plates. The gel puncture method is used to create the well on the sterilized Muller–Hinton agar plates, and these cavities were loaded with different concentrations (10, 20, 50, and 100 μg/mL) of Al2O3 nanoparticles. Finally, the plates were incubated at a controlled temperature of 37 °C for 24 h. The cell defusing and demise was measured by the growth of the inhibition zone around the well, and it was assessed by millimeter scale [25].

3 Result and discussions

3.1 Growth mechanism of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles

The aluminium oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles were synthesized using the C. sativum leaf extract. The aluminium ions (Al3+) were separated from the nitrate molecules and reduced after adding C. sativum leaf extract. The C. sativum leaf extract contains rich phytochemicals, including phenols, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids and alkaloids. Gallic acid and quercetin are important phytocompounds in the C. sativum plants [26]. Therefore, the trivalent aluminium ions might be reduced to Al2O3 nanoparticles by gallic acid or quercetin compound by donating their electrons. The gallic acid and quercetin are involved as both reducing and stabilizing molecules in the synthesis of silver–selenium bimetallic nanoparticles [26], 27].

3.2 XRD analysis

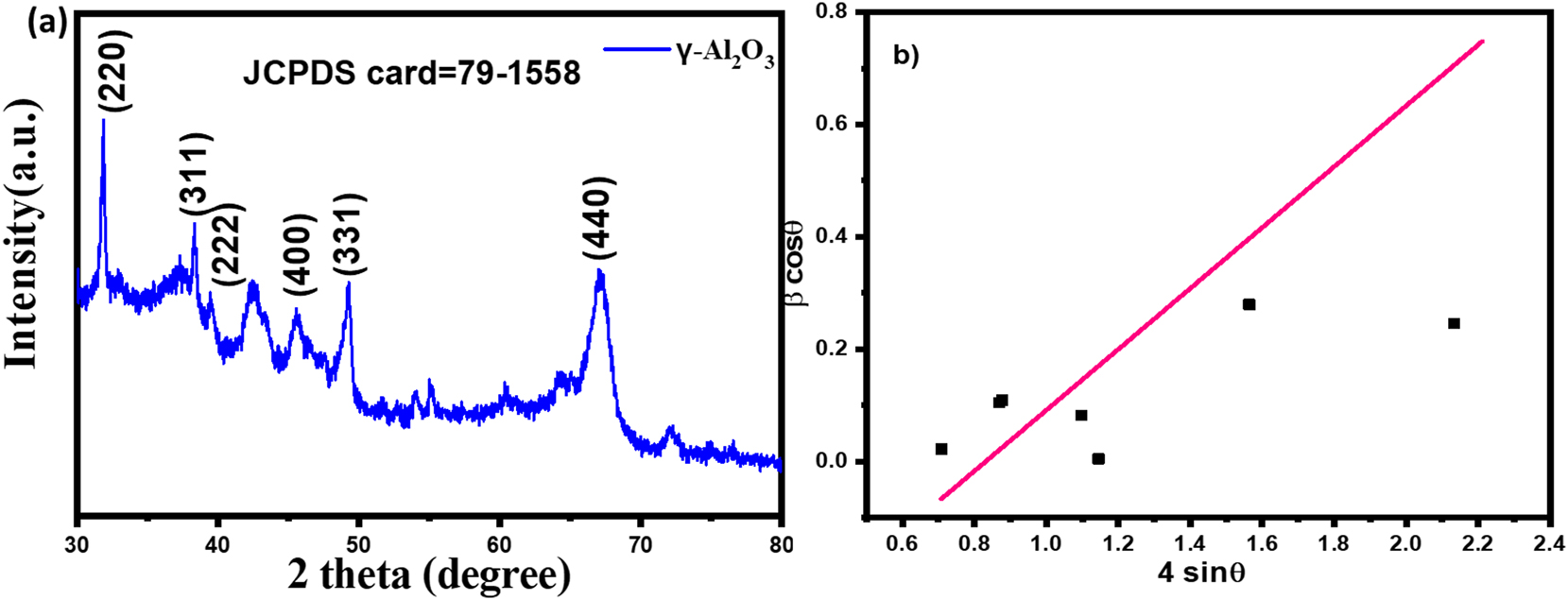

The x-ray diffractive pattern of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles is displayed in Figure 2(a). The different peaks in the γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles diffraction spectra are located at 31.91°, 38°, 39.45°, 45.49°, 49.68°, and 66.94°, respectively, and they perfectly line up with the (220), (311), (222), (400), (311), and (440) crystallographic planes. The peaks observed in the γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles diffraction pattern closely resemble the cubic crystal structure in the standard JCPDS card number (79–1,558) [28], 29]. The facilitation of nucleation sites involving both aluminium and oxygen was made easier by Coriandrum sativam molecules in contact with aluminium sources. The electron-donating properties of the plant molecules drove the attractive interactions between these molecules, resulting in the formation of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles. The peak at 66.94° indicates the crystalline nature and the intrinsic lattice strain of the γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles. Using the Debye–Scherrer formula eq. (2), the size of the crystalline structures was calculated. Here the λ = 0.154 nm and K = 0.9 for copper, β D is peak broadening [30], 31].

The size of γ-Al2O3 naoparticles was determined to be 26 nm. The microstrain of the particles was calculated by Williamson–Hall equation eq (3) by W–H plot is given in Figure 2(b) [32].

XRD Analysis of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles (a) X-ray diffraction pattern of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles, (b) Williamson–Hall plot.

The grain strain value obtained from slop of W–H plot is 0.0054. The specific surface area of as-synthesized sample was determined by the following equation.

Here, the ρ for is 3.65 g/cm3 [29]. The calculated specific surface area is 63.2 m2/g. This narrow crystallite size in cubic γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles and large specific surface area contribute to a more condensed range of crystallite sizes and is associated with a higher concentration of electrons accumulating on the surface of the nanoparticles. This decrease in crystallite size also equates to an increase in surface area, which improves the nanoparticles’ capacity to efficiently break down organic chemicals and dyes that are detrimental to the environment [33].

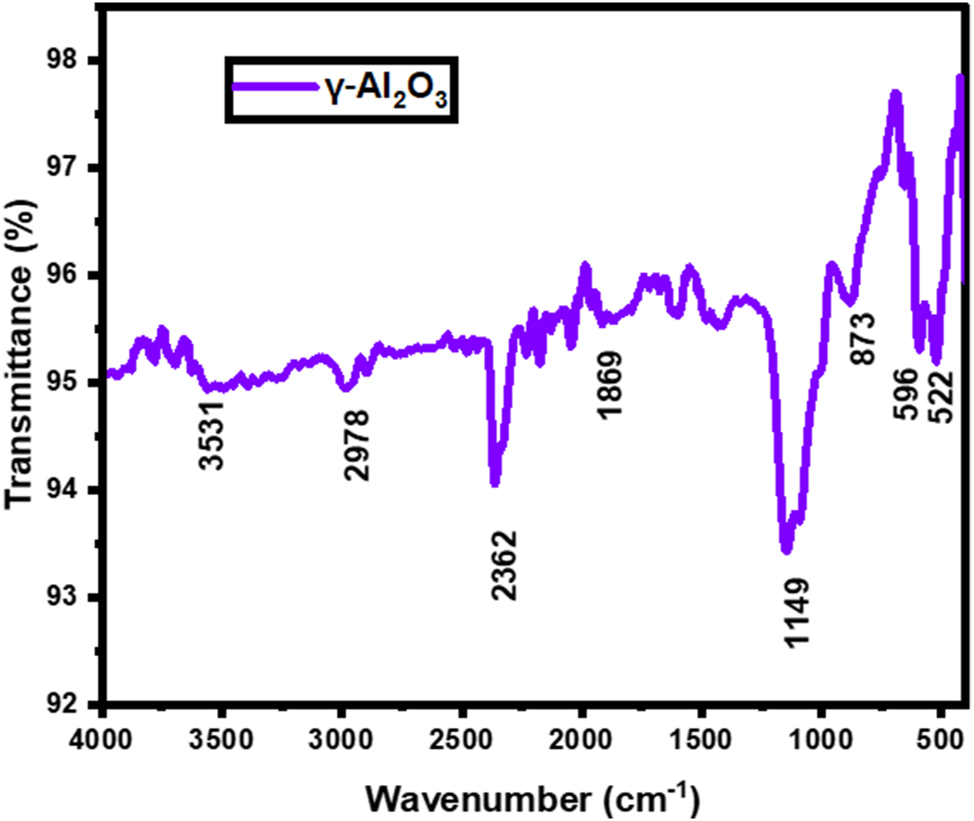

3.3 FTIR analysis

The qualitative and functional group analysis of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles were measured from FTIR spectroscopy, and their findings were demonstrated in Figure 3. The peaks at 3,531 and 1,869 cm−1 stretching vibration band of hydroxyl groups (OH) due to Al–OH and adsorped water molecules on the nanoparticle surfaces [34]. The peak of 2,978 cm−1 indicates the stretching vibration of C–H bonds, conceivably originating from organic contaminants or molecules adsorbed onto the nanoparticles. The strong peak of 2,362 cm−1 designates the carbon molecule’s existence on the nanoparticles, which may come from the plant extract or instrument.

FTIR spectra of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles.

The presence of Al–OH groups stretching vibrations on the nanoparticles was identified from the peak of 1,149 cm−1. Al–OH deformation vibrations or Al–O bonds in alumina structures correspond with the peak of 873 cm−1 [45]. Also, the peaks at 596 and 522 cm−1 might point to lattice vibrations within Al2O3 nanoparticles and Al–O bending vibrations, emphasizing their crystalline structure and confirming the presence of alumina components [35], 36]. Many chemical compounds in C. sativum, including phenols, flavonoids, and terpenes, have reducing properties. These organic compounds can aid the reduction of aluminium ions (Al3+) from aluminium nitrate by providing electron donors. Aluminium ions can interact with the functional groups found in C. sativum, such as the hydroxyl (OH) and carboxyl (COOH) groups. These functional groups might offer the aluminium species binding sites that facilitate their adsorption to the plant’s surface. The bands seen in FTIR spectrum, are listed in Table 1 along with their attributions.

Attribution of FTIR bands of Al2O3–MG.

| Band (cm−1) | Attributions |

|---|---|

| 3,531; 1,869 | OH stretching vibration (Al–OH, H2O) |

| 2,978 | C–H stretching vibrations |

| 2,362 | C–C stretching vibrations |

| 1,149 | Al–OH stretching vibrations |

| 873 | Al–O deformation vibrations |

| 596; 522 | Al–O bending vibrations |

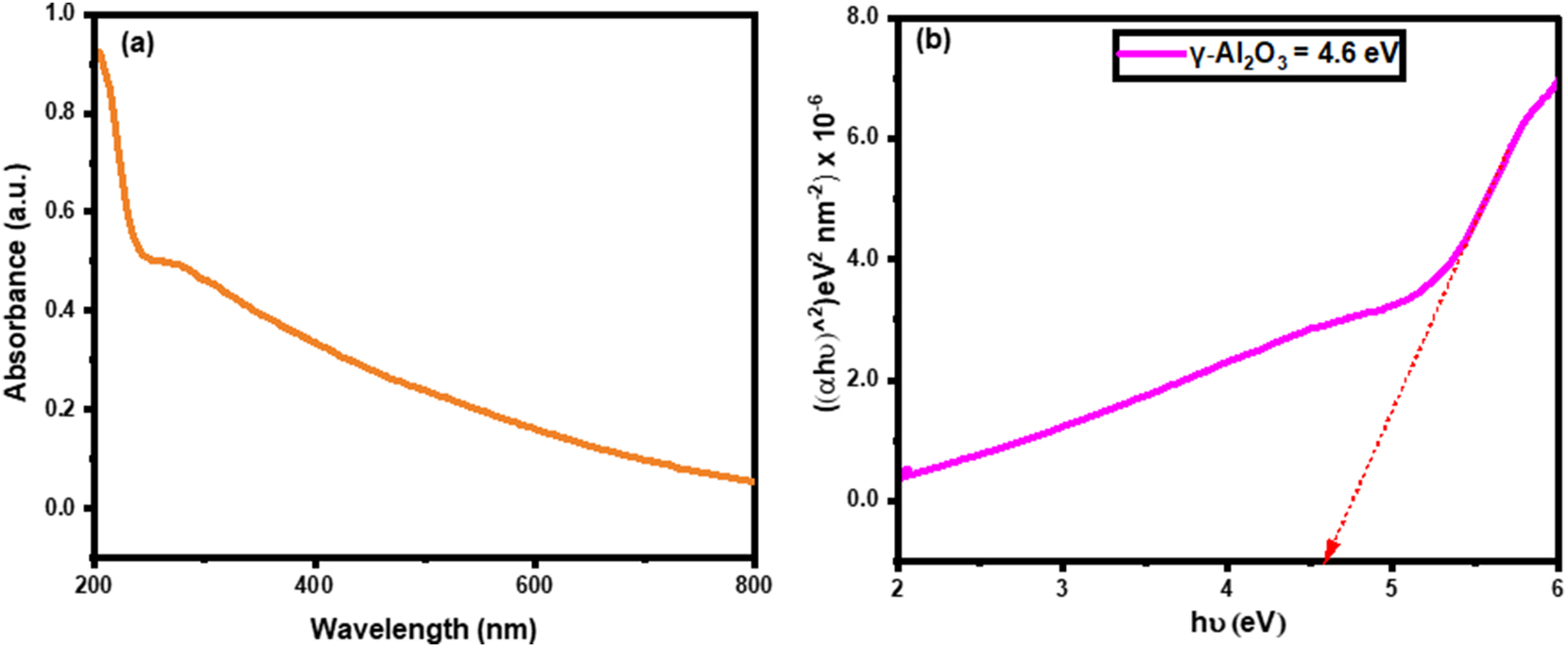

3.4 UV-DRS analysis

The optical properties of as-synthesized nanoparticles were evaluated from UV-DRS analysis. The absorbance spectrum of Al2O3 nanoparticles is presented in Figure 4(a). The green-fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles’ absorbance shows peak at 290 nm, demonstrating the electron transition from the valence band to the conduction band in the UV region. The absorbance spectrum of Al2O3 confirms the successful formation of the metal oxide from Al3+ to O2-. Moreover, oxygen existence over the surface improved the metal trapping and blue emission was occurred in UV region peak [36]. Metal oxide optical flaws were established from bandgap calculations derived from Kubelka–Munk equations [29]. The derived bandgap of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles is displayed in Figure 4(b). Generally, the UV region peak gives a wide bandgap of the materials. The bandgap of Al2O3 nanoparticles is 4.6 eV. The wide bandgap of Al2O3 nanoparticles produced a high quantity of superoxides due to their carrier production. The wide bandgap of Al2O3 nanoparticles increased the recombination time as well as induced radical scavengers. The bandgap of nanomaterials may decide the release of ions and degradation activity against target materials [36].

UV-DRS (a) absorbance spectrum of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles and (b) bandgap plot.

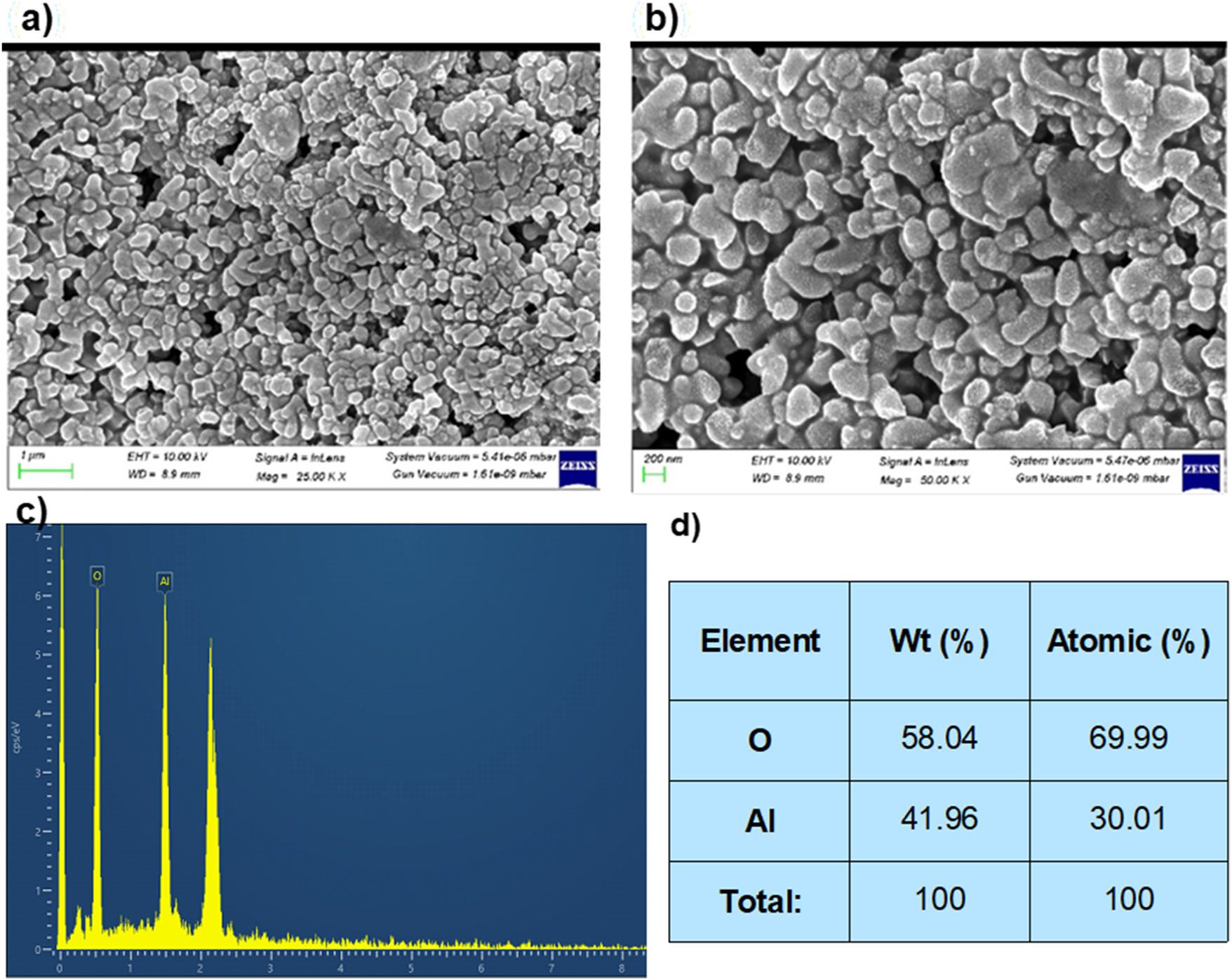

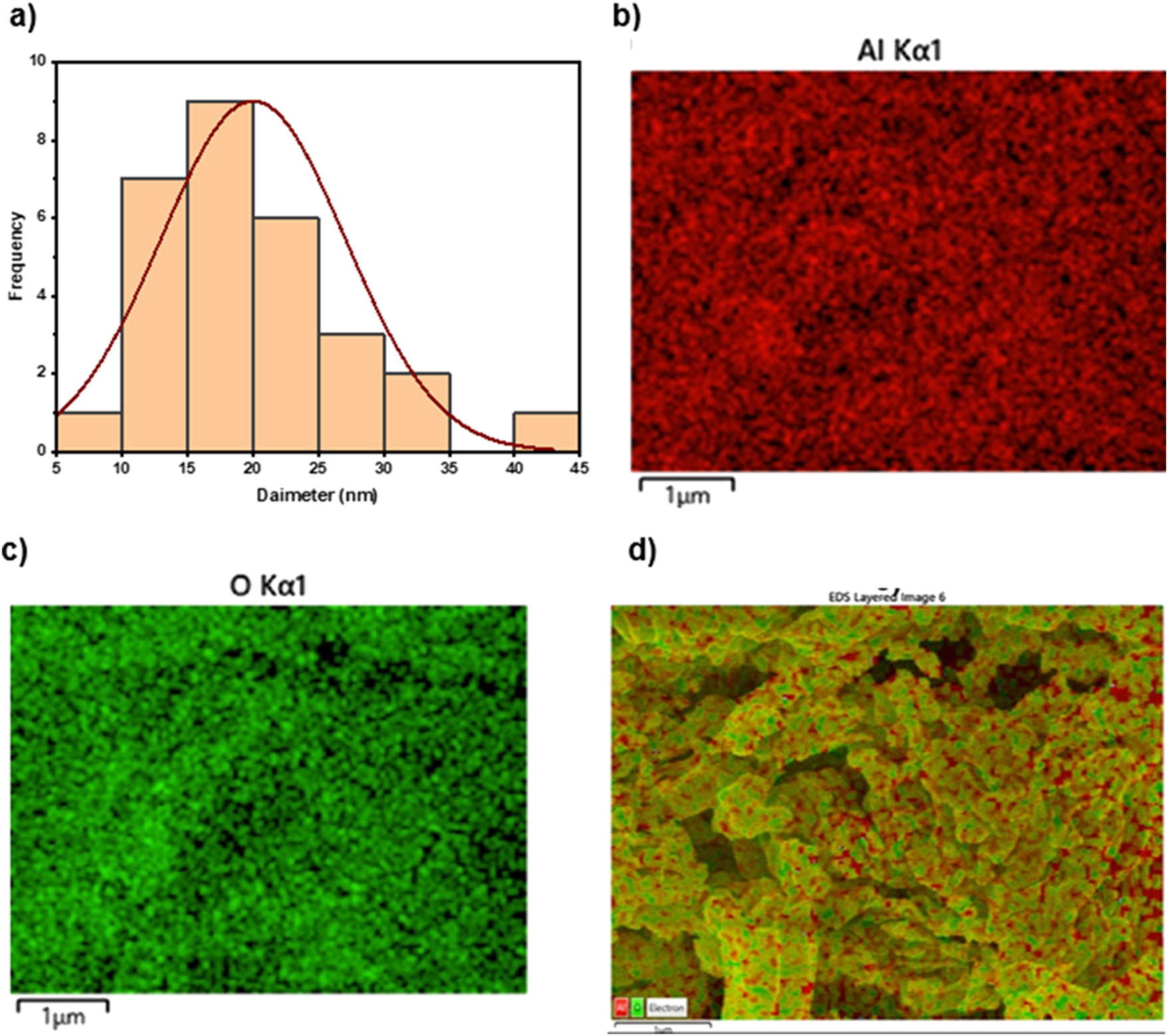

3.5 FESEM with EDX analysis

The green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles’ morphological and elemental properties are displayed in Figure 5(a and b) shows the sheet-like shape of green-fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles and other combined shapes with sheet structures. The sheet-like structure has occupied a higher surface area than other shapes of nanoparticles. Modified or improved surface area endorsed the catalytic degradation [37]. The large surface area of nanoparticles suppresses the recombination activity and can induce organic degradation. The rest of the combined sheet-like structure is derived from compounds present in plant extract to form green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles. Figure 6(a) represent the particle size distribution. The average particle size of nanoparticles is 18 nm which is quite in accordance with the particle size obtained by XRD analysis. Elemental properties and their possessions of green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles were demonstrated from EDX analysis shown in Figure 5(c and d). Aluminum contains 42 %, and oxygen has 58 % in green fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles. Al3+ is high, and their oxygen attachment produces a sheet-like structure. Their arrangement of atoms reduced the oxygen stability in green-fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles. The oxygen defects and metal orientation with lattice oxygen were evident from the EDX table in Figure 4(d) in green-fabricated Al2O3 nanoparticles.

FE-SEM images (a and b), EDX spectrum (c) and table (d) of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles.

EDX with mapping analysis. (a) Particle size distribution, (b–d) mapping analysis of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles.

Figure 6(b–d) shows the results of energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping, which reveals the atom arrangement within manufactured aluminium oxide nanoparticles. According to the mapping, aluminium and oxygen atoms are evenly distributed throughout the nanoparticle structure, with oxygen having a noticeably larger concentration. This finding highlights oxygen’s crucial function in forming the atomic structure of Al2O3 nanoparticles and sheds light on their stability and unique characteristics. The specific elemental mapping highlights the importance of oxygen in affecting reactivity, catalytic performance, and mechanical qualities. It also offers the potential for modifying nanoparticle properties and understanding their behaviour in different applications. Overall, the EDX study provides a detailed understanding of the complex atomic arrangement of Al2O3 nanoparticles, demonstrating their potential for application in various scientific and technical sectors.

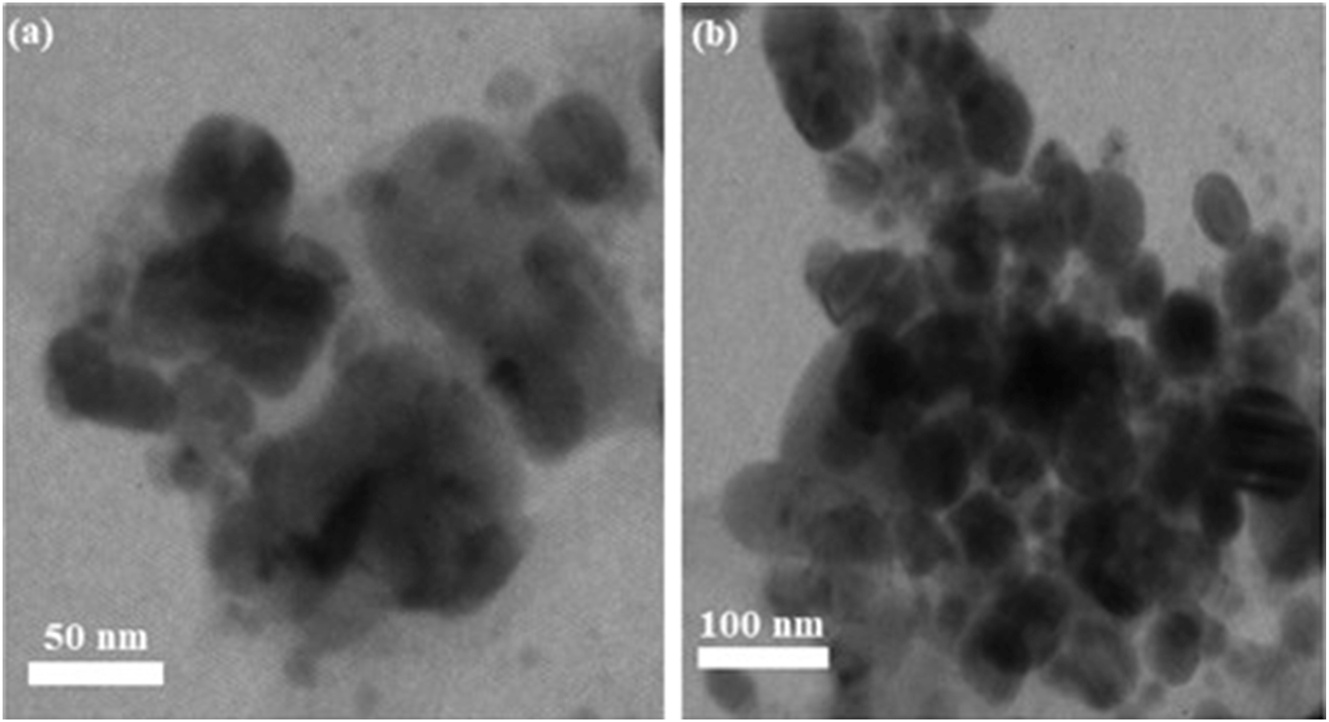

3.6 TEM analysis

The green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles TEM images are displayed in Figure 7(a and b) which depicts the sheet-like structure of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles with fewer agglomerated particles on the sheet surfaces. The agglomerated particles can be seen in Figure 7(b), and their agglomerations are attributed to plant’s bio-derivatives [38], 39]. Bio-compounds are potential candidates in engineering the structure of nanomaterials with various shapes and sizes [40]. The particle size of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles is 25 nm, well correlated with XRD crystallite size. The agglomerated particles and other condensed green products are also discussed with details by FTIR and XPS carbon analysis.

TEM images of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles at (a) 50 nm and (b) 100 nm.

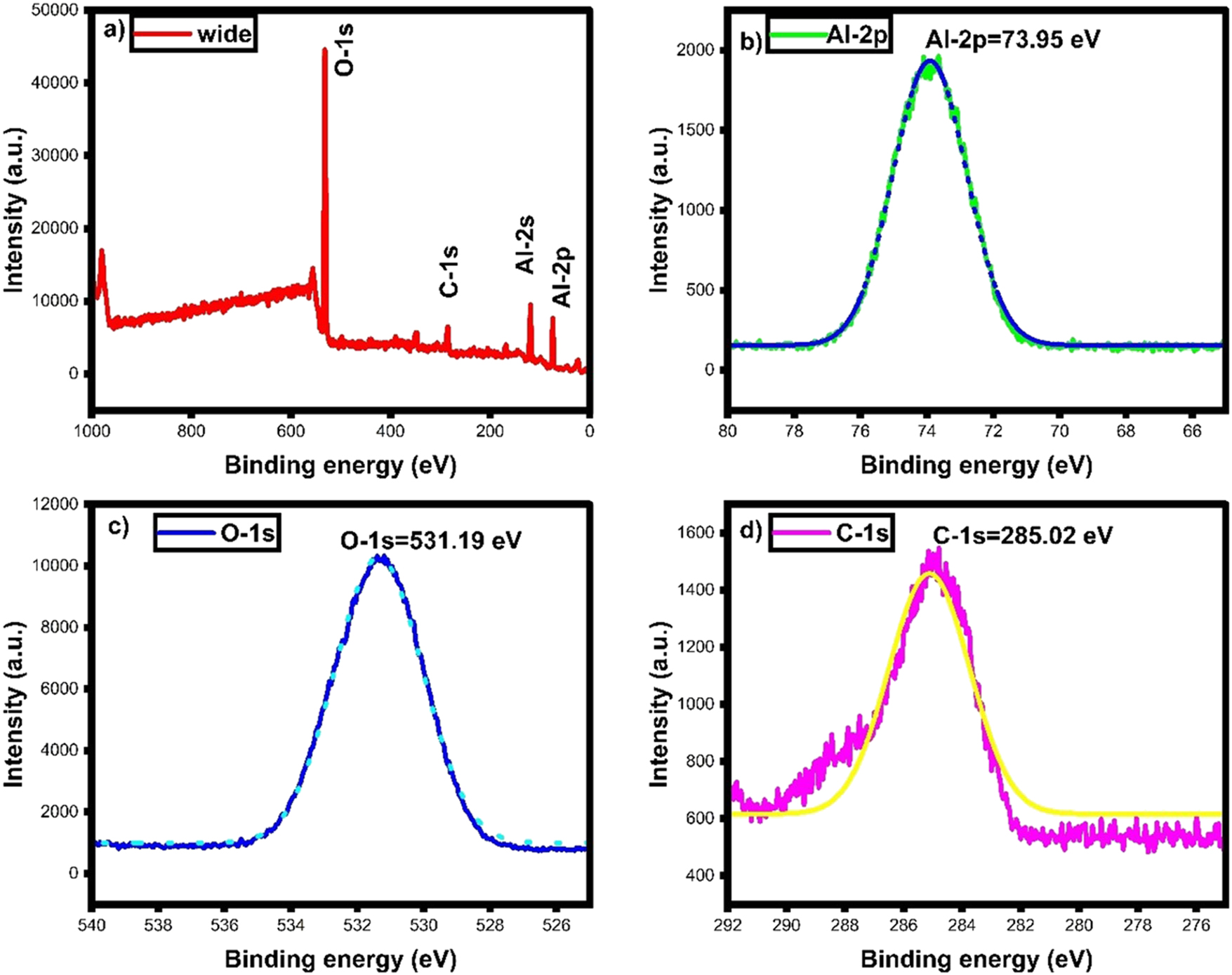

3.7 XPS analysis

The XPS spectras of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles are displayed in Figure 7. The wide spectrum (Figure 8a) indicates the elements of Al and O in green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticle. The deep scan spectra of Al, O and C are shown in Figure 8(b–d). The Al and O bond interface was generated by the stabilizing plant molecules. The lattice oxygen occupies the orbital vacancy. Al-2p interactions and accumulations were captured at 73.95 eV [41], 42]. The oxygen element attached with Al-2p state and their attachment displayed at 531.19 eV [42], 43]. The stabilization of lattice oxygen and Al core element was attained from the organic group of plant due to C–C, C=O, and C–O bonds as indicated by 285.02 eV. The plant bio-compounds are responsible for the valence-free atoms and oxygen stabilization with metal, which was well ensured by FTIR, UV and XRD analysis. Based on the XPS results, green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles further represent the phase purity, and their interactions over the plant functional groups were explained in detail.

XPS analysis. (a) XPS wide, (b) Al-2p, (c) O-1s and (d) C-1s spectra of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles.

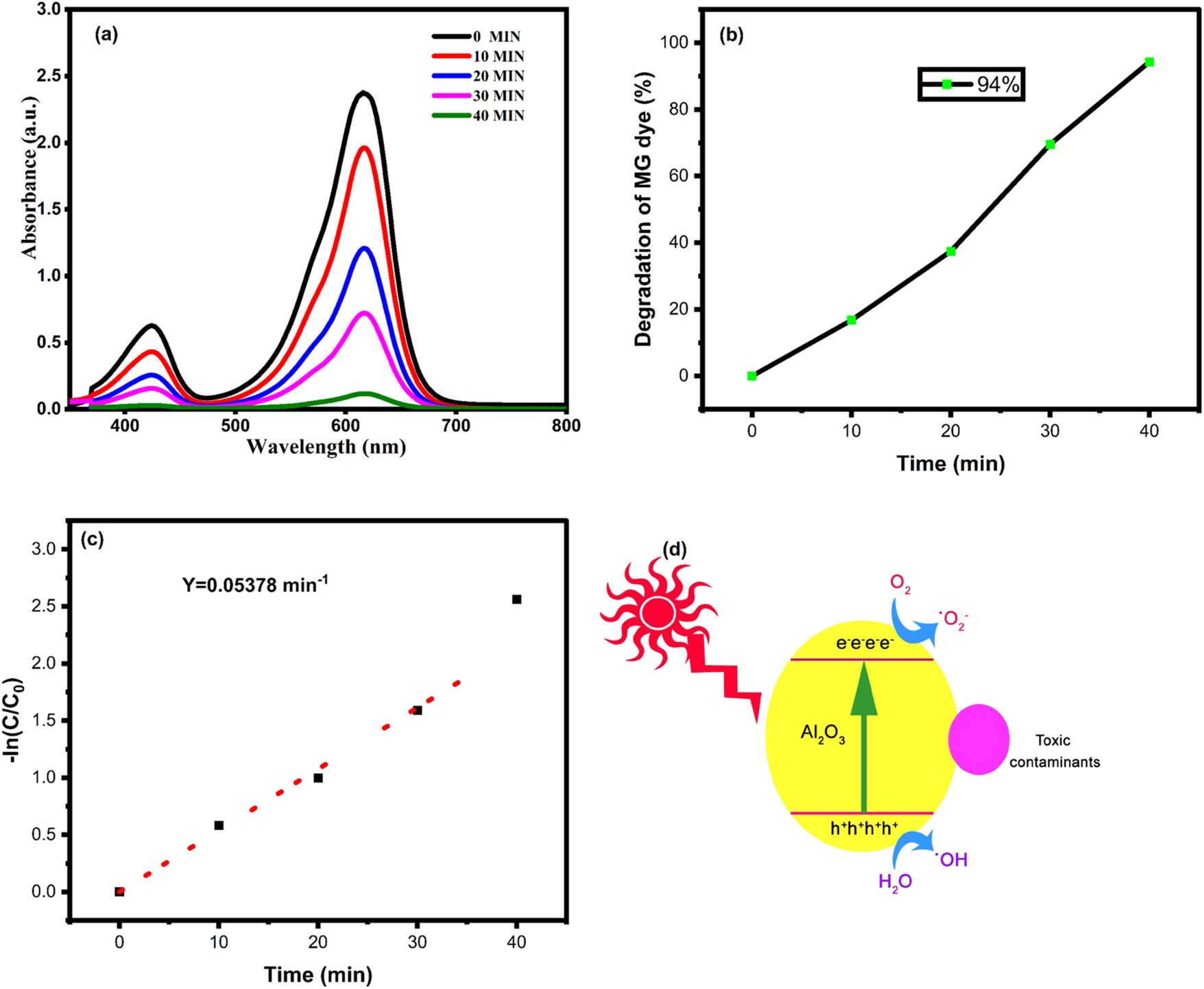

3.8 Photocatalytic dye degradation

Figure 9(a) represented the degradation of malachite green (MG) dye by green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles under UV light irradiation. The absorption spectrum of MG dye exhibited maximum absorbance at 614 nm, indicating the strong interactions between the dye molecules. Based on the relative strength of its UV–vis spectral peak, the degradation of MG was investigated. At the start of process, say (0 min) the absorption peak is maximum. Under UV light irradiation, the process of degradation unfolds, the molecules of dye start breaking down and the absorbance peak decreases accordingly. At longer irradiation times, the light driven degradation of the MG dye gradually increases, as seen by the UV-visible spectrum which presents the decrease of absorption peak at different time intervals spanning from 0 min to 40 min.

Catalytic studies. (a) Photocatalytic degradation absorbance spectrum, (b) degradation efficiency, (c) pseudo-first-order kinetic and (d) degradation mechanism of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles.

Kinetics: The kinetics of dye degradation cane be determined by the eq. (5) modeled with the modified form of Langmuir–Hinshelwood equation [34] expressed as:

Where Co initial concentration, Ct is concentration at time = t, k is rate constant, Kt is absorption coefficient and Kapp is apparent reaction rate constant [34]. The kinetics of MG degradation by Al2O3 seems to be pseudo first order with the correlation coefficient R2 = 0.99 (Figure 9c). The rate at which MG degrades is significantly accelerated by increased light intensity. Increase in intensity of radiation leads to the generation of more reactive entities in solution, which might subsequently react and break down the MG molecules [34], 44].

Mechanism: The ability of a photocatalytic activity of photocatalysts to degrade the dyes in aqeous solution could be determined by its potential to absorb light and effectiveness of electron sequence interactions. This ability promotes the growth of oxidizing hydroxide (OH•) molecules, which require a band gap value sufficient to the photons-intensity entering the system. The production of hydroxyl ions must be enhanced by the degree of charge carrier interaction. The light-irradiated green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles modified the electronic energy and promoted the migration of electrons into the conduction band. The electron mitigations and accumulations of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles are motivated by the electron trapping on the surfaces and extend the e-h pair lifetime [45], 46].

A number of steps are usually involved in photocatalytic degradation, such as 1) adsorption–desorption, 2) electron–hole pair formation, 3) recombination of e–h pairs, and 4) chemical reactions. Nevertheless, there are three main phases in the photocatalytic disintegration of MG molecules [1]: effective MG molecule adsorption [2]; significant absorption of photons of light; and [3] start of charge-transfer processes that produce reducing and oxidizing radicals [11]. The proposed mechanism for the photocatalytic breakdown of malachite green dye is depicted in Figure 7(d). The solar energy irradiates the surface of Al2O3 photocatalysts which excites the electrons (e−) in the metals’ valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), creating positive holes (h+) in the valence band (VB). Because of their high oxidative potential, the positive holes can either directly degrade molecules of dye to reactive intermediates or combine with molecules of water (H2O) to form hydroxyl radicals. Superoxide anion radicals (•O2 −) are produced when O2 molecules combine with the electrons in the metals’ conduction band. These extremely reactive radicals lead to the deterioration of dyes [44]. The following equations provide a summary of the significant potential reactions.

This photocatalytic reaction sequence highlights the effective degradation of malachite green dye using metal oxide nanoparticles under UV light irradiation. Different types of photocatalysts have been developed in order to increase photocatalysis’s effectiveness. Metal-oxide nanoparticles are particularly noteworthy among them because of their low ecological impact and ease of conversion to hydroxides or oxides. The bandgap of the material, which establishes the energy differential between the reduction and oxidation processes, is a crucial property.

The photocatalytic efficiency of nanomaterials is greatly influenced by their bandgap, where a smaller bandgap is associated with enhanced photocatalytic activity. A redshift and a boost in light absorption show that the photocatalyst is reliable as well as economical because it keeps working overtime [44].

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the degradation of MG dye under various metal-oxide nanoparticle settings in prior research work. Green synthesized Al2O3 can be regarded as a great adsorbent substitute for adsorption of MG dye and its disintegration since it demonstrated high removal percentage (94 %) with shorter time (40 min) for the removal of dye in comparison with other metal oxides in the literature evaluation. The wide bandgap, restricted e–-h pairs, nanomaterials shape, lowest crystallite size, high valency single-phase materials, surface interactions and electron trapping ability of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles to the dye molecules as well as split their bonds and lower down their energy making as a suitable candidate with superior degradation activity in removing MG dye from water bodies treatment and environment remediation [45], 46].

Comparative study of photocatalytic dye degradation of malachite dye.

| Green fabricated nanoparticles | Synthesis method | Light source | Percentage degradation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag–Mn-NPs | Wet chemical precipitation | UV light | 92 % in 100 min | [44] |

| ZnO/CuO | Hydrothermal method | UV lamp | 82 % in 240 min | [47] |

| Xanthan gum/SiO | Ultra-sonication with polymerization | Sunlight | 99.5 % in 480 min | [48] |

| Fe-doped Al2O3 | Green synthesis by Eichhornia crassipes leaf extract | – | 96.67 % in 60 min | [49] |

| ZnVFeO4 | Co-precipitation | UV light | 86 % in 180 min | [50] |

| GO-ZnO/Mn2O3) | Solvothermal route | Sunlight | 98.75 % in 30 min | [51] |

| LaFe2O3/Sb2O3 | Facile hydrothermal | Visible light | 98 % in 88 min | [52] |

| CuO | Green synthesis by Mangifera Indica leaves extract | Sunlight | 95.39 % | [53] |

| CoCr2O4/ZnO | Green synthesis by Basella alba L. leaves extract | Visible light | 90.91 % in 120 min | [54] |

| BiOBr/ZnFe2O4/CuO | Hydrothermal approach + co-precipitation | LED illumination | 98 % in 90 min | [55] |

| CH/Ce–ZnO s | Microwave assisted synthesis | Visible light | 87 %,in 90 min | [56] |

| Al 2 O 3 | Coriandrum sativum | UV illumination | 94 % in 40 min | Present work |

-

Bold value shows the work visibility and difference.

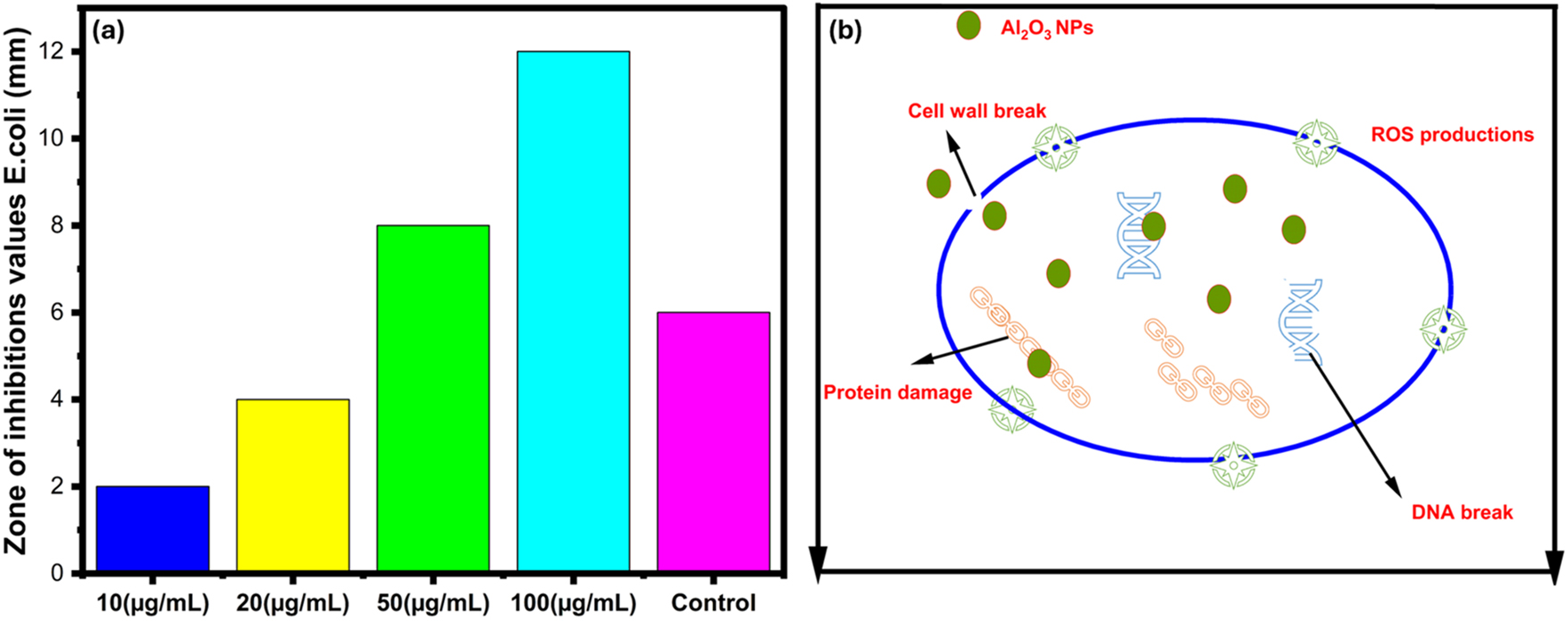

3.9 Antibacterial activity on E. coli

The antibacterial evaluations of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles were examined against E. coli. Different concentrations of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles were used to determine the activity against the pathogens and their bacterial inhibition values are listed in Table 3. The bacterial inhibition zone of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles is presented in Figure 10. The highest concentration of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles exposed the highest zone of inhibitions due to their concentration-dependent behaviour and solubility. The radical formation due to green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles effectively increases the cell death by ROS activity. Al3+ ions and dissolved oxygen molecules have suppressed the proliferation and modified the cell cultivation [57].

Antibacterial activity of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles with control Coriandrum sativum plant extract.

| Al2O3 nanoparticles concentrations (µg/mL) | Zone of inhibitions value of Escherichia coli (mm) | E. coli -C. sativum (mm) (control) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2 | 6 |

| 20 | 4 | |

| 50 | 8 | |

| 100 | 12 |

Antibacterial activity. (a) Antibacterial activity of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles at different concentrations (b) antibacterial activity mechanism of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles against E. coli.

Mechanism: The detailed antibacterial mechanism of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles is based on ROS formation, shown in Figure 10(b). The ξ–potential value of is responsible the electrostatic adherence of nanoparticles on bacterial membrane. The existence of high concentration of acidic phospholipids and low concentration of basic proteins in the outermost membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, create the negative charge of the bacterial surface [14]. The positively charged Al3+ ions interact with the cell surface and provoke cell wall destruction by electrostatic attraction. Their interactions on the cell’s outer surface break the outer shield and increase the membrane leakages. The dissolution of Al3+ ions developed ROS productivity and damaged the DNA structure and protein constructions. The entrance of nanoparticles to the bacterial system disturbs the enzymes and restricts metabolic activity. The cell demises improve cell wall leakages, membrane damage, and DNA and protein destructions [57]. The attained results of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles advocated the developed and enhanced antibacterial processes against E. coli pathogens. The antibacterial efficacy of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles describes its potential to use in bio-medical applications and microorganism removal from water bodies.

4 Conclusions

The bio-mediated synthesis of nanophase materials has attracted substantial attention across various industries because it is cost-effective, efficient, and has a low environmental impact. This study illuminates a novel strategy employing a plant extract from C. sativum to enable an in situ reduction of valence-free aluminium atoms, improving lattice oxygen stabilization for the formation of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles. The crystallinity and phase purity of green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles was confirmed by the X-ray analysis with an average crystallite size of 26 nm, contributing to an increased surface area 63.2 m2/g. The surface morphology was examined by the FESEM and TEM which presents the sheet-like shape morphologies. The confirmation of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles’ synthesis, was also confirmed by the FTIR and XPS analysis. Optical properties were determined by the DRS with the bandgap of 4.6 eV. Based on extensive optical and structural studies, it could be estimated that the oxygen vacancies cause the challenging Al3+ valency in green fabricated γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles. As-synthesized γ-Al2O3 was investigated for the photodegradation of malachite dye and antibacterial activity again gram-negative bacteria. The biogenic γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles exhibited an extraordinary degradation efficiency of 94 % with pseudo first order kinetics. This research highlights the promising potential applications of green synthesized γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles in various domains, particularly in biomedicine and wastewater treatment, and it motivates their ongoing development and enhanced usage in upcoming research and applications.

Acknowledgments

Awais Ahmad acknowledges ORIC Project (UOL.ORIC/UOS/MGP/01), University of Lahore, Pakistan. The author Awais Ahmad also acknowledges the Department of Chemistry, The University of Lahore for providing a well-organized lab at campus. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00344920). This work was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2025-603), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Funding information: Awais Ahmad acknowledges ORIC Project (UOL.ORIC/UOS/MGP/01), University of Lahore, Pakistan. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00344920). This work was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-2025-603), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contribution: Awais Ahmad, Muhammad Sufyan Javed, Mariam Khan: writing – original draft, methodology, investigation, data curation. Ikram Ahmad, Zainab M. Almarhoon: methodology, investigation, data curation. Mohamed Shelkh, Amir Muhammad Afzal: methodology, investigation. Arif Nazir: methodology, formal analysis. Sun Jea Park: writing – review and editing, conceptualization. Awais Ahmad: writing – review and editing, methodology, conceptualization. Awais Ahmad, Sun Jea Park, Dongwhi Choi: writing – review and editing, methodology, funding acquisition, conceptualization, supervision. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Noor, AE, Fatima, R, Aslam, S, Hussain, A, un Nisa, Z, Khan, M, et al.. Health risks assessment and source admeasurement of potentially dangerous heavy metals (Cu, Fe, and Ni) in rapidly growing urban settlement. Environ Res 2023:117736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.117736.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Sepahvand, S, Bahrami, M, Fallah, N. Photocatalytic degradation of 2, 4-DNT in simulated wastewater by magnetic CoFe2O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanoparticles. Environ Sci Pollut Control Ser 2022;29:6479–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13690-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Taghavi, FS, Moradnia, F, Yekke Zare, F, Heidarzadeh, S, Azad Majedi, M, Ramazani, A, et al.. Green synthesis and characterization of α-Mn2O3 nanoparticles for antibacterial activity and efficient visible-light photocatalysis. Sci Rep 2024;14:6755. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56666-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Slama, HB, Chenari Bouket, A, Pourhassan, Z, Alenezi, FN, Silini, A, Cherif-Silini, H, et al.. Diversity of synthetic dyes from textile industries, discharge impacts and treatment methods. Appl Sci 2021;11:6255. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146255.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Mani, S, Chowdhary, P, Bharagava, RN. Textile wastewater dyes: toxicity profile and treatment approaches. Emerg Eco-Friendly Approaches Waste Manag 2019:219–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8669-4-11.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Fardood, ST, Zare, FY, Moradnia, F, Ramazani, A. Preparation, characterization and photocatalysis performances of superparamagnetic MgFe2O4@ CeO2 nanocomposites: Synthesized via an easy and green sol–gel method. J Rare Earths 2024;43:736–42.10.1016/j.jre.2024.03.006Suche in Google Scholar

7. Zahid, K, Ara, B, Gul, K, Malik, S, Zia, TUH, Sohni, S. Adsorption and visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of malachite green and methylene blue dye in wastewater using magnetized copper metal organic framework. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 2024;238:1267–93. https://doi.org/10.1515/zpch-2023-0334.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Arsalani, N, Bazazi, S, Abuali, M, Jodeyri, S. A new method for preparing ZnO/CNT nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic degradation of malachite green under visible light. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 2020;389:112207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112207.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Kiani, MT, Ramazani, A, Rahmani, S, Taghavi Fardood, S. Green synthesis and characterisation of superparamagnetic Cu0. 25Zn0. 75Fe2O4 nanoparticles and investigation of their photocatalytic activity. Int J Environ Anal Chem 2022:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2022.2076219.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Ren, Q, Kong, C, Chen, Z, Zhou, J, Li, W, Li, D, et al.. Ultrasonic assisted electrochemical degradation of malachite green in wastewater. Microchem J 2021;164:106059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2021.106059.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Elkady, MF, Hassan, HS. Photocatalytic degradation of malachite green dye from aqueous solution using environmentally compatible Ag/ZnO polymeric nanofibers. Polymers 2021;13:2033. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13132033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Adedokun, O, Adedokun, OM, Bello, IT, Ajani, AS, Jubu, PR, Awodele, MK, et al.. Sol–gel synthesized lithium–cobalt co-doped titanium (IV) oxide nanocomposite as an efficient photocatalyst for environmental remediation. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 2024;239:803. https://doi.org/10.1515/zpch-2024-0835.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Roostaie, T, Abbaspour, M, Makarem, MA, Rahimpour, MR. Retracted article: synthesis and characterization of biotemplate γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles based on Morus alba leaves. Top Catal 2022:1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-022-01572-y.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Gudkov, SV, Burmistrov, DE, Smirnova, VV, Semenova, AA, Lisitsyn, AB. A mini review of antibacterial properties of Al2O3 nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022;12:2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12152635.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Akintelu, SA, Folorunso, AS, Folorunso, FA, Oyebamiji, AK. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for biomedical application and environmental remediation. Heliyon 2020;6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04508.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Soltys, L, Olkhovyy, O, Tatarchuk, T, Naushad, M. Green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: principles of green chemistry and raw materials. Magnetochemistry 2021;7:145. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry7110145.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Verma, V, Al-Dossari, M, Singh, J, Rawat, M, Kordy, MG, Shaban, M. A review on green synthesis of TiO2 NPs: photocatalysis and antimicrobial applications. Polymers 2022;14:1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14071444.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Silva, F, Domeño, C, Domingues, FC, Coriandrum sativum, L. Characterization, biological activities, and applications. In: Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention. Elsevier; 2020:497–519 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-818553-7.00035-8Suche in Google Scholar

19. Nouioura, G, El Fadili, M, El Hachlafi, N, Maache, S, Mssillou, I, Abuelizz, HA, et al.. Coriandrum sativum L., essential oil as a promising source of bioactive compounds with GC/MS, antioxidant, antimicrobial activities: in vitro and in silico predictions. Front Chem 2024;12:1369745. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2024.1369745.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Mandrekar, PP, D’Souza, A. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using coffee, Piper Nigrum, and Coriandrum sativum and its application in photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. Rasayan J Chem 2023;16. https://doi.org/10.31788/rjc.2023.1616889.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Basit, RA, Abbasi, Z, Hafeez, M, Ahmad, P, Khan, J, Khandaker, MU, et al.. Successive photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by ZnO, CuO and ZnO/CuO synthesized from coriandrum sativum plant extract via green synthesis technique. Crystals 2023;13:281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst13020281.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Parvathiraja, C, Shailajha, S. Bioproduction of CuO and Ag/CuO heterogeneous photocatalysis-photocatalytic dye degradation and biological activities. Appl Nanosci 2021;11:1411–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-021-01743-5.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Nachimuthu, S, Thangavel, S, Kannan, K, Selvakumar, V, Muthusamy, K, Siddiqui, MR, et al.. Lawsonia inermis mediated synthesis of ZnO/Fe2O3 nanorods for photocatalysis–biological treatment for the enhanced effluent treatment, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Chem Phys Lett 2022;804:139907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2022.139907.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Ahmad, A, Khan, M, Javed, MS, Hassan, AM, Choi, D, Khawar, MR, et al.. Eco-benign synthesis of α-Fe2O3 mediated trachyspermum ammi: a new insight to photocatalytic and bio-medical applications. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 2024;449:115423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2023.115423.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Gazwi, HS, Mahmoud, ME, Toson, EM. Analysis of the phytochemicals of Coriandrum sativum and Cichorium intybus aqueous extracts and their biological effects on broiler chickens. Sci Rep 2022;12:6399. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10329-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Preliminary study on phytochemical, phenolic content, flavonoids and antioxidant activity of Coriandrum Sativum l. Originating in Vietnam. In: Nhut, P, Quyen, N, Truc, T, Minh, L, An, T, Anh, N, editors. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing; 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Atrooz, O, Al-Nadaf, A, Uysal, H, Kutlu, HM, Sezer, CV. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Coriandrum sativum L. extract and evaluation of their antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities. South Afr J Bot 2023;157:219–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2023.04.001.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Sun, J, Wang, Y, Zou, H, Guo, X, Wang, Z-j. Ni catalysts supported on nanosheet and nanoplate γ-Al2O3 for carbon dioxide methanation. J Energy Chem 2019;29:3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2017.09.029.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Yu, C, Wang, S, Zhang, K, Li, M, Gao, H, Zhang, J, et al.. Visible-light-enhanced photocatalytic activity of BaTiO3/γ-Al2O3 composite photocatalysts for photodegradation of tetracycline hydrochloride. Opt Mater 2023;135:113364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2022.113364.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Fardood, ST, Moradnia, F, Forootan, R, Abbassi, R, Jalalifar, S, Ramazani, A, et al.. Facile green synthesis, characterization and visible light photocatalytic activity of MgFe2O4@ CoCr2O4 magnetic nanocomposite. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 2022;423:113621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2021.113621.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Khan, M, Janjua, NK, Khan, S, Qazi, I, Ali, S, Saad, AT. Electro-oxidation of ammonia at novel Ag2O− PrO2/γ-Al2O3 catalysts. Coatings 2021;11:257. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11020257.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Shashidharagowda, H, Mathad, SN. Effect of incorporation of copper on structural properties of spinel nickel manganites by co-precipitation method. Mater Sci Energy Technol 2020;3:201–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mset.2019.10.008.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Khan, S, Shah, SS, Janjua, NK, Yurtcan, AB, Nazir, MT, Katubi, KM, et al.. Alumina supported copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO/Al2O3) as high-performance electrocatalysts for hydrazine oxidation reaction. Chemosphere 2023;315:137659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137659.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Aazza, M, Moussout, H, Marzouk, R, Ahlafi, H. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies of malachite green adsorption on alumina. J Mater 2017;8:2694–703.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Rabu, R, Jewena, N, Das, S, Ji, K, Ahmed, F. Synthesis of metal-oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles by using autoclave for the efficient absorption of heavy metal ions. J Nanomater Mol Nanotechnol 9: 6. of. 2020;10:2.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Castro, L, Manriquez, M, Ortiz-Islas, E, Bahena-Gutierrez, G. Kinetic study of the photodegradation of ibuprofen using tertiary oxide ZnO–Al2O3–TiO2. React Kinet Mech Catal 2023;136:1705–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11144-023-02430-y.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Suppiah, DD, Julkapli, NM, Sagadevan, S, Johan, MR. Eco-friendly green synthesis approach and evaluation of environmental and biological applications of iron oxide nanoparticles. Inorg Chem Commun 2023;152:110700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2023.110700.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Matar, GH, Andac, M. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using brown Egyptian propolis extract for evaluation of their antibacterial activity and degradation of dyes. Inorg Chem Commun 2023;153:110889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2023.110889.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Vahini, M, Rakesh, SS, Subashini, R, Loganathan, S, Prakash, DG. In vitro biological assessment of green synthesized iron oxide nanoparticles using Anastatica hierochuntica (Rose of Jericho). Biomass Convers Biorefinery 2023:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04018-x.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Deng, K, Huang, S, Wang, X, Jiang, Q, Yin, H, Fan, J, et al.. Insight into the suppression mechanism of bulk traps in Al2O3 gate dielectric and its effect on threshold voltage instability in Al2O3/AlGaN/GaN metal-oxide-semiconductor high electron mobility transistors. Appl Surf Sci 2023;638:158000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.158000.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Song, Y, Hu, X, Chou, K. Effect of Al2O3 on viscosity and structure of CaO–SiO2–FeOt–(Al2O3)–BaO slag. Ironmak Steelmak 2023;50:1521–7.10.1080/03019233.2023.2194738Suche in Google Scholar

42. Silva Júnior, ME, Palm, MO, Duarte, DA, Catapan, RC. Catalytic Pt/Al2O3 monolithic foam for ethanol reforming fabricated by the competitive impregnation method. ACS Omega 2023;8:6507–14. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c06870.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Kim, J, Tahmasebi, A, Lee, JM, Lee, S, Jeon, C-H, Yu, J. Low-temperature catalytic hydrogen combustion over Pd-Cu/Al2O3: catalyst optimization and rate law determination. Kor J Chem Eng 2023;40:1317–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-023-1437-8.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Xu, Z, Zada, N, Habib, F, Ullah, H, Hussain, K, Ullah, N, et al.. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of malachite green dye using silver–manganese oxide nanoparticles. Molecules 2023;28:6241. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28176241.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Rajendran, S, Palani, G, Shanmugam, V, Trilaksanna, H, Kannan, K, Nykiel, M, et al.. A review of synthesis and applications of Al2O3 for organic dye degradation/adsorption. Molecules 2023;28:7922. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28237922.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Saito, D, Tamaki, Y, Ishitani, O. Photocatalysis of CO2 reduction by a Ru (II)–Ru (II) supramolecular catalyst adsorbed on Al2O3. ACS Catal 2023;13:4376–83. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.2c06247.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Madiha, B, Zahid, Q, Farwa, H, Nida, M. Biosynthesis of copper nanoparticles by using Aloe barbadensis leaf extracts. Inter Ped Dent Open Acc J 2018;1:000110. https://doi.org/10.32474/ipdoaj.2018.01.000110.Suche in Google Scholar

48. Elella, MHA, Goda, ES, Gamal, H, El-Bahy, SM, Nour, MA, Yoon, KR. Green antimicrobial adsorbent containing grafted xanthan gum/SiO2 nanocomposites for malachite green dye. Int J Biol Macromol 2021;191:385–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.040.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Thakur, A, Kaur, H, Aguedal, H, Singh, V, Singh, V, Goel, G. Biogenic synthesis of Fe-doped Al2O3 nanoparticles using Eichhornia crassipes for the remediation of toxicant malachite green dye: kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Inorg Chem Commun 2024:112340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112340.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Mostafa, EM, Amdeha, E. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of malachite green dye by highly stable visible-light-responsive Fe-based tri-composite photocatalysts. Environ Sci Pollut Control Ser 2022;29:69861–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20745-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Rout, DR, Chaurasia, S, Jena, HM. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of malachite green using manganese oxide doped graphene oxide/zinc oxide (GO-ZnO/Mn2O3) ternary composite under sunlight irradiation. J Environ Manag 2022;318:115449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115449.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Jabeen, S, Ganie, AS, Ahmad, N, Hijazi, S, Bala, S, Bano, D, et al.. Fabrication and studies of LaFe2O3/Sb2O3 heterojunction for enhanced degradation of malachite green dye under visible light irradiation. Inorg Chem Commun 2023;152:110729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2023.110729.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Dat, NM, Nam, NTH, An, H, Cong, CQ, Hai, ND, Phong, MT, et al.. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for photodegradation of malachite green and antibacterial properties under visible light. Opt Mater 2023;136:113489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2023.113489.Suche in Google Scholar

54. Fadhila, FR, Umar, A, Chandren, S, Apriandanu, DOB, Yulizar, Y. Biosynthesis of CoCr2O4/ZnO nanocomposites using Basella alba L. leaves extracts with enhanced photocatalytic degradation of malachite green in aqueous media. Chemosphere 2024;352:141215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141215.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Sabit, DA, Ebrahim, SE. Fabrication of magnetic BiOBr/ZnFe2O4/CuO heterojunction for improving the photocatalytic destruction of malachite green dye under LED irradiation: dual S-scheme mechanism. Mater Sci Semicond Process 2023;163:107559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2023.107559.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Saad, AM, Abukhadra, MR, Ahmed, SA-K, Elzanaty, AM, Mady, AH, Betiha, MA, et al.. Photocatalytic degradation of malachite green dye using chitosan supported ZnO and Ce–ZnO nano-flowers under visible light. J Environ Manag 2020;258:110043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.110043.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

57. He, X, Liu, B, Chen, Y, Liu, Y, Huang, Q. Modulating the bactericidal activity and corrosion resistance of Al2O3 porous ceramics through Cu and Fe co-introduction for membrane support application. Mater Today Commun 2023;35:105850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.105850.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Artificial neural network-driven insights into nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials melting for heat storage optimization

- Optical, structural, and morphological characterization of hydrothermally synthesized zinc oxide nanorods: exploring their potential for environmental applications

- Structural, optical, and gas sensing properties of Ce, Nd, and Pr doped ZnS nanostructured thin films prepared by nebulizer spray pyrolysis method

- The influence of nano-size La2O3 and HfC on the microstructure and mechanical properties of tungsten alloys by microwave sintering

- Green fabrication of γ- Al2O3 bionanomaterials using Coriandrum sativum plant extract and its photocatalytic and antibacterial activity

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Special Issue on Emerging Nanotech. for Biomed. and Sust. Environ. Appl.

- Beyond science: ethical and societal considerations in the era of biogenic nanoparticles

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity