Abstract

The aim of this study is to optimize fly ash utilization by combining lime, gypsum, and quarry dust in various proportions to develop fly ash lime gypsum quarry dust (FLGQ) bricks with dimensions of 230 mm × 110 mm × 70 mm, as a potential alternative to traditional bricks. The investigation analysed the compressive strength, split tensile strength, water absorption, density, and initial rate of absorption of FLGQ bricks across different mixes. Mix 9 (M9), comprising of 35% fly ash, 10% lime, 25% gypsum, and 30% quarry dust, exhibited a 15% higher compressive strength (7.2 MPa) and 12% higher split tensile strength (0.85 MPa) compared to the superior conventional brick. Water absorption for M9 was reduced by 18%, enhancing the durability. Prediction models for compressive and split tensile strengths were developed using regression analysis, achieving over 92% accuracy when compared to experimental data at 28 and 56 days. Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between the 14th, 28th, and 56th days results, reinforcing the reliability of predictions in brick compressive strength. These research findings indicate that M9 is superior and more sustainable alternative to traditional bricks, with significant improvements in key performance metrics.

1 Introduction

Clay bricks are widely used in construction across India, but their traditional manufacturing process presents significant environmental challenges, including soil erosion and the potential creation of wetlands. These environmental impacts highlight the need for more sustainable alternatives in building materials. One promising solution lies in utilizing industrial waste, such as fly ash and quarry dust, for brick production. The reuse of these materials not only helps address environmental concerns but also offers a sustainable alternative to conventional clay bricks. However, despite the large quantities of fly ash and quarry dust generated annually, their potential in brick manufacturing remains largely underutilized.

Fly ash, a byproduct of coal and lignite combustion in thermal power plants, represents a significant resource. A report on fly ash production and utilization for the year 2021–2022 revealed that only 259.86 million tonnes of fly ash were effectively utilized from the 270.82 million tonnes generated, with just 11.68% used in brick and tile production. Similarly, quarry dust, a waste material produced from stone quarrying, poses substantial environmental disposal problems and health hazards. Local sources indicate that quarry dust production in India increased by 12.17% in 2022. Given the environmental risks associated with these materials, their incorporation into brick production offers a viable solution for waste disposal and resource conservation.

Over the past four decades, research has led to the development of a wide range of novel building materials and cost-effective construction methods [1,2]. Sustainable building materials are now preferred over traditional materials that rely on finite natural resources. Conventional building materials contribute to pollution in water, land, and air [3], while the accumulation of unmanaged industrial waste products has raised serious environmental concerns [4]. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize innovative technologies that recycle waste materials into valuable resources [5].

Fly ash, combined with lime and gypsum, is widely used as a binding agent in the manufacturing of solid and hollow bricks [6]. Incorporating waste materials into brick production provides a feasible eco-friendly solution [7], addressing the prevailing disposal challenges associated with these materials [8,9]. Additionally, bricks made from industrial waste are energy-efficient, as the primary raw materials produce no emissions during production [10]. The addition of quarry dust to the mix has shown a positive impact on both density and compressive strength, as observed in previous studies.

Mookherjee et al. [11] conducted research on the use of pond ash in brick production, analyzing the behavior of industrial bricks made from pond ash at the microscopic level. Garg et al. [12] suggested incorporating various industrial wastes, such as rice husk ash, quarry dust, fly ash, and Ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS), into concrete. They explored how recycled aggregates influenced the durability, flexural strength, and compressive strength of the concrete.

Soharu et al. [13] developed eco-friendly fly ash bricks using discarded concrete materials and introduced self-healing bacteria (SHB) into the production process. Their study assessed the mechanical characteristics, microscopic structure, and visual properties of four distinct brick formulations, finding that bricks made from concrete waste with SHB exhibited strength comparable to conventional red clay bricks. Sithole et al. [14] introduced a method using two South African waste materials – fly ash and waste gypsum – for crafting eco-conscious construction materials aimed at reducing environmental pollution. Bernard et al. [8] examined how fly ash and GGBFS influenced the characteristics of autoclaved aerated concrete blocks. Their mechanical assessments focused on compressive strength, modulus of rupture, dry density, and water absorption.

Mukhtar et al. [15] proposed eco-friendly unburned coal ash (CA) bricks as substitutes for traditional fired clay bricks. These bricks, composed of cement, sand, quarry dust, coal ash, and lime, were subjected to a 28-day curing process and manufactured under high pressure. The tests revealed that unburned CA bricks exhibited lower water absorption, minimal efflorescence, and reduced weight per unit area compared to conventional clay bricks. The research also included a cost analysis comparing clay bricks with unburned CA bricks.

Waheed et al. [16,17] compared the mechanical and durability characteristics of unburned fly ash bricks with traditional fired clay bricks. Their study analysed the compressive strength and water absorption of small cylindrical compacts made from fly ash, cement, and sand using different aggregates and forming methods. They later manufactured full-sized unburned fly ash bricks and evaluated their mechanical and durability properties, concluding that unburned fly ash bricks exhibited similar performance to conventional fired clay bricks.

Premalatha et al. [18] studied the integration of Groundnut Shell Ash as a partial substitute for fly ash in unburned fly ash bricks. The research included several tests, such as energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, bulk density measurement, compressive strength testing, water absorption analysis, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. Sharma and Guleria [19] explored the potential use of waste materials such as fly ash and silty sand in brick production, incorporating gypsum and lime into the brick mix. Their method involved drying samples using the Hessian technique and measuring their unconfined compressive strength after 56 days of drying.

1.1 Significance of the study

The aim of this study is to explore the potential of fly ash-lime-gypsum-quarry dust (FLGQ) bricks as a sustainable alternative to conventional clay bricks. By utilizing industrial waste products such as fly ash and quarry dust, the research contributes to reducing environmental impacts and promoting sustainable construction practices. The development of FLGQ bricks aims to provide an eco-friendly, efficient solution for the construction industry with enhanced mechanical properties, such as compressive strength, density, and water absorption resistance. This research highlights the significance of using industrial byproducts to create environmentally sustainable building materials.

2 Objective of the study

This research focuses on exploring the optimal combination of FLGQ to produce bricks with targeted mechanical properties. These properties include compressive strength, density, initial rate of absorption (IRA), water absorption, split tensile strength, and efflorescence in FLGQ bricks. When water is added to the mix, fly ash, lime, and gypsum become reactive. Similar to concrete, the strength of fly ash bricks develops rapidly during the initial days of curing and gradually stabilizes. Gypsum exhibits stronger binding properties compared to lime, making it a crucial component in enhancing overall strength.

The lightweight nature of fly ash bricks reduces construction expenses related to dead weight and material handling. However, with an increase in fly ash content, water absorption tends to rise, while a higher brick density reduces water absorption rates. Fly ash bricks with an optimal amount of gypsum demonstrate improved resistance to sulphate conditions, and the curing temperature significantly influences the final hardness of the bricks. Incorporating quarry dust into the mix has shown a positive impact on both density and compressive strength. These bricks offer versatility, as they can be moulded into various shapes and sizes using machine moulding, without requiring highly skilled labour [11]. Table 1 outlines the chemical composition of fly ash, lime, gypsum, and quarry dust used in this study.

Chemical composition of constituent materials

| Constituents | Fly ash (%) | Lime (%) | Gypsum (%) | Quarry dust (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 73.36 | — | — | 93.86 |

| Al2O3 | — | — | — | 18.1 |

| Fe2O3 | — | — | — | — |

| MgO | — | 0.56 | — | — |

| CaO | 1.58 | 99.44 | 44.12 | 3.38 |

| K2O | 1.78 | — | — | 5.88 |

| TiO2 | 0.42 | — | — | 3.71 |

| Na2O | — | — | — | 3.99 |

| FeO | 0.251 | — | — | — |

| CaSO4 | 73.12 |

Previous studies indicate that the specific gravity and density of fly ash bricks typically range between 2.75 and 3.0, consistent with earlier findings. The materials used, including FLGQ conform to ASTM D 854-92 standards, and basic tests on quarry dust were conducted in accordance with IS 383-1987 guidelines.

3 Research methodology

The objective of this research is to investigate the strength and durability attributes of bricks produced using FLGQ and determine the most effective combination for achieving optimal brick characteristics. To fulfil this goal, a well-defined and succinct research methodology was devised, encompassing aspects such as research design, data collection methods, and analytical techniques.

3.1 Research design

To prepare the FLGQ bricks, different mix proportions of FLGQ were used. The bricks were sized at 230 mm × 110 mm × 70 mm, and the ratios in their composition were established by consulting prior literature and conducting preliminary experiments. The samples were prepared using a hydraulic press and then cured for 7 days before testing.

3.2 Data collection methods

The methods used for collecting data included – evaluation of compressive strength, water absorption, split tensile strength, initial rate of absorption, and density of the manufactured bricks. The compressive strength was determined using Universal Testing Machine complying ASTM standard C39. The split tensile strength assessment utilized a splitting tensile testing machine complying with ASTM standard C496. The water absorption evaluation adhered to ASTM standard C67, while the density analysis abides with ASTM standard C140.

3.3 Analysis techniques

The collected data were analysed to determine the most suitable mix proportion for the FLGQ bricks. The regression analysis was performed to statistically analyse and pinpoint significant differences among the various mix proportions. The results were interpreted based on the research objectives and the existing literature. SEM and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were carried out to assess the size and composition differences among the materials in the mix. SEM imaging was used to visualize the surface structure of FLGQ bricks, while XRD analysis helped to identify the mineral composition of the mix’s components.

The research methodology of the study was designed comprehensively to evaluate the strength and durability attributes of FLGQ bricks. Its design aimed to guarantee the reliability, validity, and robustness of the collected and analysed data. This research will play a role in advancing a sustainable and economically viable alternative for traditional bricks. The findings are anticipated to be valuable for the construction industry, particularly in areas with restricted access to conventional building materials.

4 Experimental procedure

4.1 Materials

The ingredients employed in manufacturing fly ash bricks include fly ash, lime, gypsum, quarry dust, and water. Class F fly ash, which adheres to IS 3812 (2003) (26), is utilized. Gypsum confirming to IS 1290, quarry dust which adheres to IS 1542 -Zone II, and shell lime adhering to IS 1540 were obtained either directly from local quarries or from nearby sources. Chemical compositions of each material are listed in Table 1.

4.1.1 Fly ash

Fly ash exhibits a specific gravity of 2.19. Table 1 provides the silica and calcium contents in the fly ash, with values of 73.3 and 1.5%, respectively. Figure 1 displays the SEM image of a fly ash particle.

SEM image of fly ash.

Figure 1 showcases the structures of both pure fly ash and lead fly ash as observed using SEM. Within the SEM image, several small hollow spherical particles, termed cenospheres are visible, ranging in diameter from 4 to 23 µm. The predominant constituents include amorphous silicon dioxide (SiO2), exhibiting a spherical and smooth form, and crystalline SiO2, characterized by sharp, pointed, and needle-like shapes. The spherical shape indicated that the material is pozzolanic in nature. Additionally, the materials consist mainly of aluminium oxide (Al2O3) and iron oxide (Fe2O3). Typically, fly ash is a heterogeneous mixture of glassy particles containing a variety of distinguishable crystalline phases, including quartz, mullite, and different iron oxides. A few agglomerate particles also visible in the SEM image of lead fly ash particles now have an elongated shape. This figure also depicts the potential for lead ultrafine particles to adhere to fly ash cenosphere surfaces.

The XRD pattern of fly ash, as shown in Figure 2, indicates that the chemical composition is alkaline. The major phases present in the fly ash samples consist of silicon (Si), oxygen (O), titanium (Ti), and aluminum (Al). XRD analysis reveals high quantities of silica, alumina, and iron oxides. The resulting mineral phases identified in the XRD peaks include crystalline phases of quartz, mullite, haematite, and calcium oxide. The peak mineral identified in the XRD analysis, as shown in Table 1, provides the chemical composition of fly ash, which matches the results of the PDF 01-089-1961 for the compounds SiO₂ and quartz.

XRD image of Fly ash.

4.1.2 Lime

The specific gravity of lime is found to be 2.7. The CaO in the powder form having particles lower than 600 microns is used.

The SEM images of lime in Figure 3 show that particles are irregular in shape. The surface morphology of lime appears rough, consisting of micro-pore and fibre likes structure. It is determined that there are vertical and transverse overlapping structure, and each layer had a surface area resembling a dense, fibre-like structure. Additionally, the surface structure was obtained to be multi-layered and rough elements of the raw power were detected through EDS including MgO and CaO. The small grain sizes likely provide greater surface area and increased reactivity. The particle size should correlate proportionally with the surface area.

SEM image of lime.

According to XRD data, lime, the natural mussel shell, mostly contains CaCO3, and is found in PDF01-070-5490. Crystalline structure of lime powder were determined by XRD analysis, the peak obtained from the XRD patterns represents the calcite phases and are shown in Figure 4. The most severe peaks seen in the XRD are calcite of CaCO3 at 2-tetra scale 350. The result of XRD also confirms the chemical composition of lime given in Table 1. Almost same results are seen in the other research journals.

XRD image of lime.

4.1.3 Gypsum

The CaO content in gypsum is found to be 44.12% and is given in Table 1 and the specific gravity of gypsum is 2.31.

Gypsum powder results as a by-product in the fertilizer industry. Gypsum can be used as a substitute for calcite. The SEM image of gypsum particles is irregular in shape and is shown in Figure 5, which illustrates the morphology of gypsum crystals. A bassanite type crystal structure was observed across all gypsum samples. These clusters appear in the structure of every gypsum type. The morphology varies slightly, with smooth surface aggregate and filament like particles being the dominant features. Traces of gypsum crystals can be identified on the surface using an SEM. The crystal clusters reach sizes as large as 20 microns. It is indicated that this material well bonded with other pozzolanic material.

SEM image of gypsum.

Gypsum is analysed by XRD method and confirmed the phase using PDF00-021-0816 CaSO4·2H2O, PDF01-072-7532 Apatite were identified from the result of XRD. There is a slight difference in the peak width of gypsum shown in Figure 6. Qualitatively, it can be observed that the peak corresponding to the lattice plane has a smaller value compared to the other peak in the sample containing format, while the other peaks show the same width in both samples. This can be explained by changes in the morphology of the gypsum crystals, which lead to variations in the size of the coherently scattering domains in different crystallographic directions. Peak broadening is related to the mean apparent crystallite sizes of the phases.

XRD image of gypsum.

4.1.4 Quarry dust

It serves as a filler substance and possesses a significant concentration of silica (SiO2). The specific gravity of quarry dust is found to be 2.57.

The mineral present in quarry dust is given in Table 1 and Figure 7 represents the morphology. The particles exhibit an angular shape with a coarse surface texture and are present in considerable quantities. Though particles are closely packed and a bonding exists, voids are also seen. The angular form of the quarry dust increases the friction thereby reducing the characteristic flow of the concrete. Nevertheless, the intertwining of the angles could enhance the strength properties of the concrete and brick.

SEM image of quarry dust.

The quarry dust is analysed using XRD method and the amorphous content was found to be 71% for CaCO3 PDF01-071-3699, SIO2 (Quartz) PDF 01-079-0910, Calcium magnesium carbonate (Dolomite) CaMg (CO3)2 PDF00-011-0078, iron oxide Fe2O3 PFD 01-076-4113 were identified in phase report in Figure 8. The crystalline structure of this material was identified as triclinic. The material showed peaks at 2θ values around 27° and 29°. Potassium aluminosilicates (sodium feldspar, albite) and calcium comprise a group of minerals called feldspars. Feldspars, together with quartz and mica, form the primary components of granitic rocks, which are believed to have originated from igneous processes [11].

XRD image of quarry dust.

5 Mix proportion

The proportion of constituent material is determined by preparing various trials in the laboratory. The details of mix M1–M13 are given in Table 2. The lime content used by Gourav and Venkatarama Reddy [20] and Kumar [21] is found to be 10%. Hence, the lime content in this study is limited to 10% to promote the maximum quantity of gypsum which is a locally available product. The binder content in fly ash brick suggested by Kumar [22] and Sumathi and Saravana Raja Mohan [23] is in the range of 20–60%. The present study uses the binder content, comprising lime and gypsum, ranging from 20 to 45%.

Material proportions

| Mix | Fly ash | Lime | Gypsum | Quarry dust |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 80 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| M2 | 75 | 10 | 15 | 0 |

| M3 | 70 | 10 | 20 | 0 |

| M4 | 65 | 10 | 25 | 0 |

| M5 | 60 | 10 | 30 | 0 |

| M6 | 50 | 10 | 35 | 5 |

| M7 | 55 | 10 | 25 | 10 |

| M8 | 45 | 10 | 25 | 20 |

| M9 | 35 | 10 | 25 | 30 |

| M10 | 25 | 10 | 25 | 40 |

| M11 | 15 | 10 | 25 | 50 |

| M12 | 40 | 10 | 25 | 25 |

| M13 | 30 | 10 | 25 | 35 |

The 7th day compressive strength was evaluated across different mix proportions, labelled from M1 to M6, encompassing various gypsum levels. The mix M4, featuring a lime-to-gypsum ratio of 10:25, exhibited the highest compressive strength on the 56th day. Consequently, this lime-to-gypsum ratio from M4 was maintained for all subsequent mixes. For determining the optimum amount of quarry dust, the fly ash content in the M4 is replaced with quarry dust suitably to get the specimen M7 to M13.

Quarry dust substituted fly ash and the compressive strength of the bricks was analysed on the 7th, 14th, 28th, and 56th days. Furthermore, measurements were taken for the split tensile strength, the initial rate of absorption, water absorption, density, and efflorescence of each brick sample. The split surface of the brick specimen is analysed by using an SEM.

5.1 Process operations

5.1.1 Preparation of specimen

The material’s components are bundled by weight, the binder’s combination of gypsum and lime. Ball mill is initially used to combine the lime and gypsum. The fly ash is added and properly mixed with the binder. These ingredients are prepared and then blended in a rotating motion with the quarry dust. A water-to-binder ratio of 0.2 was deemed suitable for the brick powder moulding procedure. The dry mix is poured into the concrete mixer along with water, and the mixing process is built. The mixture is depressed to create a homogenous, partially wet mix shown in Figure 9a, which is then moved to a mortar-driven moulding machine shown in Figure 9b, for compacting the loose material. This compresses the mixture within the mould. When the electric mortar rotates at a speed of 1,720 rpm, a pressure of 16 MPa is applied, simultaneously exerting a compressive force on the integrated mould to minutely compress the material inside. As a result, the dimensions of the fly ash brick are achieved at 230 mm × 110 mm × 70 mm. Subsequently, the formed fly ash brick samples are manually removed from the mould without any observed damage to the bricks during the extraction process. The freshly compacted brick was then dried for 24 h, afterwards the sample was cured for the remaining 6 days (3 times per day) as shown in Figure 9c. The specimen was examined for additional work after curing.

(a–d) Preparation of specimen, (a) mixing of materials, (b) preparation of brick, (c) curing, and (d) compressive testing machine.

5.1.2 Compressive strength

The compressive strength of brick specimen after curing for 7th , 14th, 28th, and 56th days are experimentally determined for an average of the six specimen as given in Table 3. The compressive strength is found to vary between 1 and 3.7 MPa for the 7th day and between 3.8 and 12 MPa for the 56th day. The increase in strength on the 58th day when compared to the 7th day is due to the pozzolanic reaction of the binder material in the brick specimens. The M4 is found to have a strength of 3.7 N·mm−2 on the 7th day which is greater than the minimum brick strength required for structural application as per IS 3495 (Part- 1):1976. The compressive strength of M4 is found to be higher among M1 to M6 specimens. Similarly, the compressive strength of M9 is found to be greater when compared to the other specimens for M7 to M13.

Compressive strength with age, density, water absorption, split tensile strength, and IRA variation with mix proportion

| Mix | Fly ash | Lime | Gypsum | Quarry dust | Compressive strength (MPa) | Density | Water absorption | Split tensile strength | IRA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7th day | 14th day | 28th day | 56th day | |||||||||

| M1 | 80 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 1,193 | 36.3 | 0.21 | 0.53 |

| M2 | 75 | 10 | 15 | 0 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 1,224 | 35.2 | 0.21 | 0.51 |

| M3 | 70 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 1.9 | 2 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 1,220 | 32.4 | 0.23 | 0.48 |

| M4 | 65 | 10 | 25 | 0 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 1,220 | 28.9 | 0.31 | 0.42 |

| M5 | 60 | 10 | 30 | 0 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 1,223 | 30 | 0.31 | 0.44 |

| M6 | 55 | 10 | 35 | 0 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 1,219 | 31.2 | 0.288 | 0.46 |

| M7 | 55 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 5.04 | 7.5 | 1,320 | 20.5 | 0.62 | 0.34 |

| M8 | 45 | 10 | 25 | 20 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 6.3 | 9.3 | 1,380 | 18.1 | 0.91 | 0.305 |

| M9 | 35 | 10 | 25 | 30 | 3.7 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 12 | 1,529 | 16.5 | 1.44 | 0.28 |

| M10 | 25 | 10 | 25 | 40 | 1.6 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 1,657 | 18.9 | 0.6 | 0.31 |

| M11 | 15 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 1,750 | 21.5 | 0.52 | 0.36 |

| M12 | 40 | 10 | 25 | 25 | 2.3 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 7.6 | 1,480 | 15.9 | 1.02 | 0.268 |

| M13 | 30 | 10 | 25 | 35 | 2.1 | 5.2 | 7.05 | 8.9 | 1,603 | 16 | 0.84 | 0.27 |

The particle packing and binding in specimen M9 is found to be greater which is indicated by the lower voids in the microstructure evaluation using SEM Figure 1. This is the reason for having greater strength for the M9 specimen when compared to other specimens.

The findings suggested that substituting fly ash with quarry dust is advantageous up to 35% level. The combination of quarry dust and binder significantly influences the overall strength of the brick specimen. The binder covers the inert quarry dust and bonds together and provides better stiffness to the matrix. If the quarry dust content is more, the coverage of the binder may not be sufficient to develop an effective bond inside the matrix. From the results, it is evident that with the increase in proportion of quarry dust content, the density and water absorption increases from the tolerance, but strength reduces. The maximum strength is found for M9, hence the proportion of constituent M9 is taken as the best proportion among the various mix from M1 to M13 from Figures 10 and 11.

(a)–(f) Void and crack pattern of fly ash brick without quarry dust content. (a) M1, (b) M2, (c) M3, (d) M4, (e) M5, and (f) M6.

Effect of fly ash and quarry dust on the IRA of FLGQ bricks.

The most important property of any brick is its compressive strength. A graph is prepared for a period of 56 days commencing with results on the 7th, 14th, 28th, and 56th day, respectively, for 13 specimens. The results of testing the FLGQ brick after 7, 14, 28, and 56 days are shown in Table 3. For the 7th day, the value of compressive strength varies from 1.3 to 3.1 MPa. For the 14th day, the value of CS varies from 1.7 to 5.2 MPa. The corresponding value ranges between 2.1 and 7.05 MPa for the 28th-day observation and is between 3.2 and 12.0 MPa for the 56th day. Thus, M9 is selected as an ideal specimen with a maximum 56th day compressive strength as 12 MPa.

From the graph in Figure 12, an addition of quarry dust percentage up to 30% in FLGQ brick resulted in first an increase in compressive strength and then a slight decrease in compressive strength was observed.

Variation in 7th, 14th, 28th, and 56th day compressive strengths for various quarry dust content.

The observed strength improvement can be attributed to the filling of gaps among quarry dust particles with binding material, resulting in a denser and better-connected structure known as the filler effect. The finer texture of quarry dust powder offers a larger specific surface area, causing water added to the mix to surround the particles, reducing workability as the concentration of quarry dust powder increases. This reduced workability during casting contributes to the lower compressive strength seen in mixes containing more than 30% quarry dust and fly ash. The sudden decline in strength might be mainly due to increased bonding between loose particles resulting from the addition of quarry dust. As the amount of quarry dust powder increases, the workability of the concrete decreases, leading to insufficient compactness [18]. The compactness of the concrete is inversely related to the brick’s porosity, and an increase in porosity can reduce the compressive strength.

5.1.3 Density

The average density of the saturated surface brick specimens is determined. The density of the brick specimen is found to vary between 1,193 and 1,224 kg·m−3 for specimens M1 to M7 as shown in Figure 13. The highest density is found for the specimen M4. The water absorption of brick is an indication of voids connected to the surface. The water gets filled in the voids when immersed for 24 h. The water absorption is found to be lower for brick specimen M4 when compared to specimens designated by M1 to M6. This is because the voids in the M4 specimen is relatively lower and is also observed in the SEM image Figure 10d. Similarly, specimen M9 is found to have lower water absorption when compared to specimens M7 to M13. This indicated that the surface-connected pores are lower in M9, and it corroborates with the SEM results given in Figure 14c.

Effect of fly ash and quarry dust on the density of FALGQ bricks.

(a–g) Void and crack pattern of fly ash brick with quarry dust content. (a) M7, (a) M8, (c) M9, (d) M10, (e) M11, (f) M12, and (g) M13.

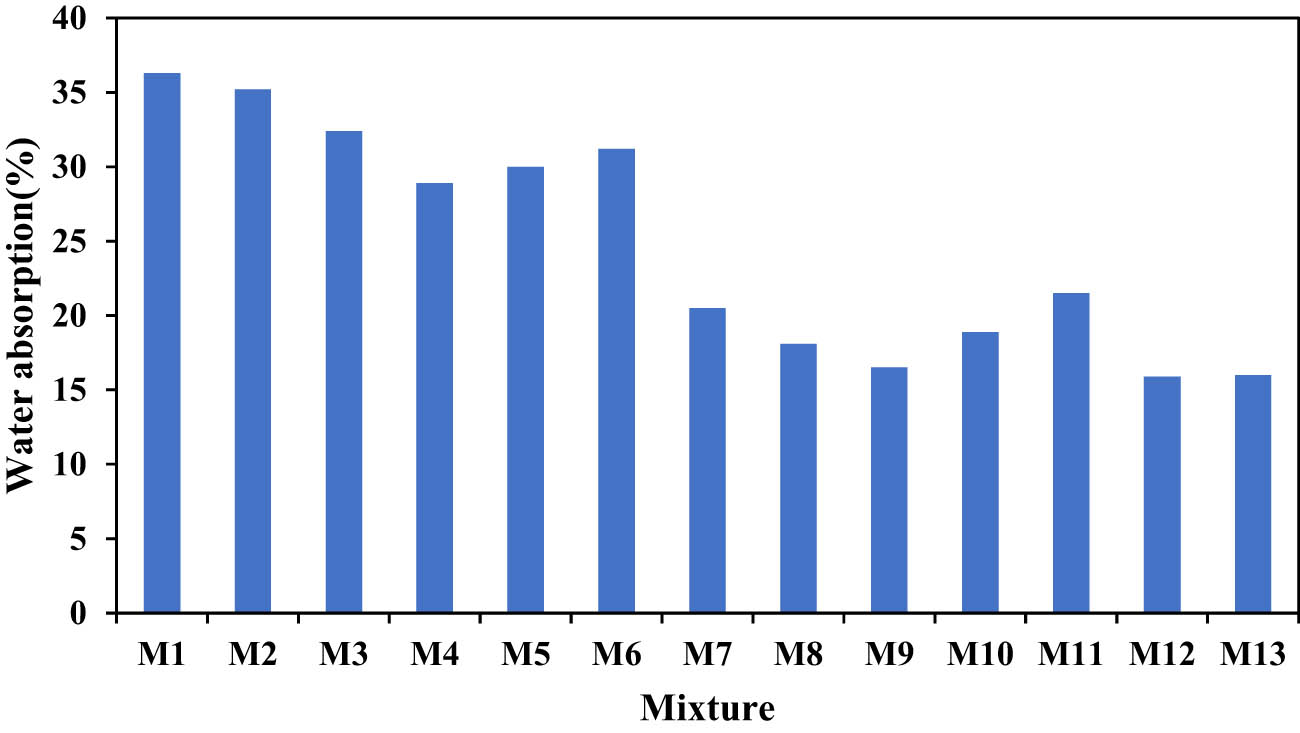

5.1.4 Water absorption

Brick seldom encounters water exposure when utilized for internal purposes, like forming wall elements within a structure. The water absorption of brick holds little significance in this context since the material remains unaffected by freeze-thaw cycles. However, when brick is employed as an external component, as seen in locations like pedestrian pathways, it comes in direct contact with water. In such cases, water absorption becomes crucial due to the adverse effects of freeze-thaw phenomena. Despite the absence of a specified limit for water absorption capacity in the EN 771-1 code, certain countries, including Brazil, have established regulations. According to the Brazilian standard NBR 6480 [25], the water absorption value must not surpass 22%, as illustrated in Figure 15.

Effect of fly ash and quarry dust on the water absorption of FALGQ bricks.

The graph depicts the outcomes of a water absorption test conducted on specimens over 56th day. As the percentage addition of quarry dust increases, the rate of water absorption also increases (15.9–20.5%).

5.1.5 Efflorescence

Effloresce is the indication of leaching out salty crystalline in bricks. These crystals are leached out in the presence of moisture and left deposited at the surface resulting in patches at the surface. The percentage of the surface covered by crystalline deposits was determined based on visual observation. The presence of more patches indicates the presence of more salt crystals. The specimens M1 to M13 showed no effloresce at the surface, which indicates that the brick does not contain salty crystalline.

5.1.6 Split tensile strength

The tensile strength of a brick when subjected to splitting is a critical factor in evaluating the overall tensile resilience of masonry structures under different stress conditions. Split tensile strength of brick measures the resistance against tension, which is essential to ensure that it can withstand crack/failure forces under load. The brick is compressed between two steel bars which causes splitting of the brick that ranges between 0.21 and 1.44 MPa, Figure 16. The specimen M4 exhibits a higher split tensile strength compared to specimens M1 to M6. This indicates that M4 is having less defects in it. Similarly, specimen M9 is found to have higher split tensile strength among specimens M7 to M13. This is due to the fact that the M9 has fewer voids which is confirmed in the SEM image given in Figure 14m.

Effect of fly ash and quarry dust on the split tensile strength of FALGQ bricks.

5.1.7 Initial rate of absorption

The significance of brick absorption lies in its impact on water availability for the effective hydration of cement mortar. When brick exhibits high initial absorption, it adversely influences the water supply for hydration. In Figure 11, the initial absorption rates for brick specimens M4 and M9 are 0.42 and 0.28 gm·cm−2·min−1, respectively. These brick specimens demonstrate a low initial absorption rate, ensuring that internal water in the mortar remains retained, preventing its loss to brick absorption. Consequently, the bond between the brick and mortar is expected to be quite robust following the cement’s hydration in the mortar.

6 Result and discussion

The brick specimen’s physical characteristics, such as density, water absorption, efflorescence, and initial absorption rate, are assessed. Furthermore, measurements are taken for the compressive strength and split tensile strength. The microstructure of the brick samples is investigated through an analysis of SEM images capturing the fractured or cracked surfaces.

6.1 Microstructure of brick specimen

The SEM is utilized to analyse the microstructure of FLGQ bricks. Figures 10 and 14 display voids on the fractured surface of the specimens, corresponding to brick specimens M1 to M13. SEM images reveal voids ranging from 0.67 to 4.99 µm in size. Additionally, several large and micro-cracks are visible, particularly in specimens M1 to M6. These significant pores and cracks, remnants of the material in the bricks, likely played a role in the poor performance of the samples. These areas represent potential weaknesses identified during the mechanical testing of the brick specimens [26], M4 is found to have relatively lesser internal imperfections. The presence of these minor cracks likely played a role in enhancing the structural effectiveness of the brick specimen. This means that the mix M7 to M13 had relatively lesser void in the brick specimen than M4 and among these M9 is found to have the lowest voids.

6.2 Mechanical properties of bricks

6.2.1 Compressive strength

The findings of the compressive strength test for the FLGQ brick are showcased in Table 3. The maximum 56th day compressive strength of FLGQ brick obtained is 9.3 kN·mm−2. This indicates that the brick exhibits commendable compressive strength and meets the criteria outlined in the reference [27].

The incorporation of quarry dust powder notably affects the compressive strength of FLGQ brick to some extent, primarily by filling inner voids. From the graph, it is clear that compressive strength is directly proportional to quarry dust content up to 30%. Among the various proportions of FLGQ bricks, only M9 exhibited a 7th-day compressive strength greater than 3.5 MPa [28,29]. Since the minimum compressive strength of brick used in construction purpose is 3.5 MPa, M9 can be used as a substitute for country-burnt clay bricks and hollow bricks. The superior strength values seen in the M9 mix might be attributed to the fine texture and grading characteristics of quarry dust, gypsum, lime, and fly ash powder.

Bricks serving as an in-fill material do not require the strength of engineering bricks. Therefore, various mix ratios identified in this study can be effectively used as an infill material. Compressive strength of traditional cement bricks that are already on the market is 5–8 MPa whereas that of the proposed FLGQ brick is 12 MPa. Therefore, FLGQ brick is a green alternative to locally available cement brick where compressive strength is a prime concern. Previous research references selected for this study are included in Table 4, and the results from the 56th test are shown in Figure 17.

Parameter reported by author

| Parameter considered | References |

|---|---|

| Compressive strength with the mix proportion | Kumar [21] |

| Kumar [22] | |

| Gourav and Venkatarama Reddy [20] | |

| Sumathi and Saravana Raja Mohan [23] | |

| Değirmenci [30] | |

| Shen et al. [31] | |

| Split tensile strength | Humphery and Mary [32] |

| Sinkhonde et al. [33] | |

| Mahdi et al. [34] | |

| Elahi et al. [35] | |

| Sharma et al. [36] | |

| Chakradhara Rao [26] | |

| Younis et al. [24] |

Effect of fly ash and quarry dust on the 56th-day compressive strength of FALGQ bricks.

6.2.2 Split tensile strength

Table 3 indicates the results of split tensile strength assessment conducted on the FLGQ brick. At 56th day, the brick exhibited a superior split tensile strength of 1.44 kN·mm−2. The tensile strength observed in this study surpassed the average tensile strength of burnt clay and other materials examined in the existing literature and confirmed with IS 5816 [37].

6.3 Mechanical properties of bricks

6.3.1 Density of the bricks

Table 3 and Figure 13 displayed the average wet density of different proportions of FLGQ brick. The density of FLGQ bricks found in this study are relatively higher than that of fly ash bricks suggested by other researchers. The density of the proposed FLGQ brick (M9) is measured to be 1,529 kg/m3, which is sufficient to compare with the density of standard burnt clay bricks.

6.4 Durability property of the brick

6.4.1 Water absorption

The durability of the brick underwent assessment through the analysis of its water absorption and initial absorption rate. Table 3 and Figure 15 depict the water absorption findings, demonstrating conformity to the IS 3495-2 standard, which specifies 20% less water absorption requirement for the burnt bricks. This confirms the acceptability of the current brick’s water absorption, meeting the necessary benchmarks for structural purposes.

The results detailing water absorption in FLGQ bricks are presented in this document. The minimum water absorption of FLGQ brick with 0% quarry dust is 30% and the minimum water absorption of FLGQ brick (M9) with 30% quarry dust is 16.5%. Therefore, water absorption of FLGQ brick (M9) conforms to the guidelines of IS 3495 – Part 2 [11,17], which specify that burnt bricks should have a water absorption rate of less than 20%.

6.4.2 Initial rate of absorption

Table 3 and Figure 11 shows the initial absorption rate of the brick. The bricks absorption coefficient at 56 days is 0.28 gm·cm−2, which is within the acceptable range as per the ASTM C – 67, suggesting that its resistance to absorption is considered acceptable and exhibits lesser shrinkage as well as stronger bond when compared to burnt clay brick.

6.4.3 Efflorescence

No remarkable indication of efflorescence was detected and all the FLGQ bricks were conforming to IS specification. Hence, the bricks can be used for all types of constructions.

6.5 Covariance strength result experimental vs predicted

Figure 19 shows the experimental vs the predicted strength of covariance. The covariance provides insight into how two variables are related to one another more precisely. Covariance refers to the measures of how two variables in a dataset will change together. As per the mathematical correlation result, a positive correlation was observed from 14th, 28th, and 56th day. After cross referring with previous author journal article, most of the current findings show strong alignment. A more detailed description of these results is provided in Table 5.

Comparison of predicted strength of existing research and present study

| Sl. no. | Author (country) | Mix proportion and material used | No. of specimen | Strength MPa@days | % Variation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 14 | 21 | 24 | 28 | 48 | 56 | 72 | 90 | 96 | |||||

| 1 | Present (India) | F: 35 | 296 | 12 | 81% | 81% | 89% | 96% | ||||||

| L: 10 | ||||||||||||||

| G-25 | ||||||||||||||

| Q-40 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | Kumar [21] (India) | F: 20–80 | 240 | 1.98–5.5 | 73% | 78% | 78% | 65% | ||||||

| L: 10–60 | ||||||||||||||

| CP: 10–40 | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | Kumar [22] (India) | F: 60–90 | 432 | 2.2–5 | 75% | 44% | 42% | |||||||

| L: 5–30 | ||||||||||||||

| CP: 5–30 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | Sumathi and Saravana Raja Mohan [23] (India) | F: 5–50 | 81 | 5.04–7.91 | 34% | 61% | 91% | |||||||

| L: 5–30 | ||||||||||||||

| G: 2 | ||||||||||||||

| QD: 23–53 | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Kannan Rajkumar et al. [38] (India) | F: 40–75 | 48 | 8.3–9.8 | 42% | 77% | 90% | |||||||

| L: 15–30 | ||||||||||||||

| G: 10 | ||||||||||||||

| QD: 15–35 | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | Shen et al. (China) [31] | F: 65–74 | 30 | 1.4–9.8 | 81% | 89% | ||||||||

| PG: 18–23 | ||||||||||||||

| L: 8–12 | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | Garg et al. [39] (India) | F: 40 | 24 | 2.9–8.5 | 24% | 95% | 95% | |||||||

| CP: 40 | ||||||||||||||

| L-20 | ||||||||||||||

F: fly ash, PG: Phosphogypsum, L: Lime, QD: Quarry dust, CP: Calcined phosphogypsum.

6.6 Predication model

6.6.1 Regression analysis using prediction model for compressive strength

The relation between the variable can be estimated using regression analysis. The technique is mainly based on the modelling and the variables in this study, independent variables are fly ash percentage, quarry dust percentage, and age in days and dependent variable is compressive strength at 7th, 14th, 28th, and 56th days.

Predicted model compressive strength of brick

where C s is the compressive strength, F a is the percentage proportion of fly ash, Q d is the percentage proportion of quarry dust, G y is the percentage proportion of quarry dust, and A g is the age in days.

Based on these findings, it is evident that the suggested model closely aligns with the experimental data, effectively forecasting the compressive strength of FLGQ Bricks. To facilitate easy comparison, both the experimental and predicted results have been graphically represented in Figure 18. Significantly, the proposed method produces results that show impressive consistency with the experimental findings gathered on the 28th and 56th days.

Comparison chart of experimental and predicted 7th, 14th, 28th, and 56th day compressive strength results of various mixes of M1 to M13.

6.6.2 Predicted split tensile strength

where S t is the split tensile strength, F a is the percentage proportion of fly ash, Q d is the percentage proportion of quarry dust, and G y is the percentage proportion of gypsum.

The proposed prediction equation can effectively determine the 56th day split tensile strength with an accuracy of 96.5%. It is evident that the split tensile strength value obtained for FLGQ brick maintains a consistent ratio with the compressive strength. This has been confirmed by the findings of previous authors, as shown in Table 6.

Data from experiment published in the literature on split tensile strength

| Sl. no. | Author | Country of origin | Material used | No. of specimen used | Split tensile strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Present | India | Fly ash, lime gypsum, and quarry dust | 13 | 1.44 |

| 2 | Humphery and Mary [32] | Ghana | Burnt clay | 4 | 1.5–2.88 |

| 3 | Sinkhonde et al. [33] | Concrete cubes | 1 | 2.1–2.9 | |

| 4 | Mahdi et.al [34] | India | Paving block | 3 | 3 |

| 5 | Elahi et al. [35] | Bangladesh | Fired clay brick, cement, and fly ash | 270 | 0.2–0.79 |

| 6 | Sharma et al. [36] | India | Brick dust, marble dust, and ceramic dust | 21 | 2.975–3.759 |

| 7 | Chakradhara Rao [26] | India | Brick and stone dust, recycled fine aggregate, recycled aggregate, and natural aggregate concrete | 8 | 2.4–3.4 |

| 8 | Younis [24] | Crushed brick, dolomite, and crushed brick | 14 | 2.6–4.21 | |

| Total | 334 | 0.2–4.21 (avg. range) | |||

7 Conclusion

The present study investigated the strength characteristics of FLGQ bricks as a sustainable alternative to conventional bricks. It explored the correlation between the constituents (fly ash, lime, gypsum, and quarry dust) and the key outcomes, including compressive strength, water absorption, split tensile strength, and density.

Among the various combinations tested, the experimental blend consisting of 35% fly ash, 10% lime, 25% gypsum, and 30% quarry dust yielded the most favourable results. The compressive strength of the M9 specimen was measured at 12 kN·mm−2, which aligns with the class designation recommended by IS 12894:2002. Furthermore, a predictive model was developed to estimate the compressive strength based on the fly ash percentage, quarry dust percentage, and the age of the specimen. The split tensile strength of the M9 specimen on the 56th day was found to be 1.44 kN·mm−2, with a prediction model achieving an accuracy rate of 96%.

The density of the proposed FLGQ brick was recorded at 1,529 kN·m−³, within the acceptable range for burnt clay bricks. The water absorption rate of the FLGQ brick was 16.5%, conforming to the standards set by IS 3495:2. The IRA of the FLGQ brick was 0.28 g·cm−²·min−1, meeting the specifications outlined in ASTM 67. Overall, the study highlights the potential of FLGQ bricks as a sustainable substitute for traditional bricks.

The research underscores how the combination of fly ash, lime, gypsum, and quarry dust impacts the overall strength of these bricks, demonstrating that the accuracy of the predictive equations improves significantly after the 14th, 28th, and 56th days, leading to more precise results. Additionally, the study reveals a positive correlation between the constituents and strength development beyond the 7th day, as illustrated in Figure 19 and Table 6. These findings contribute to the understanding of environmentally friendly brick production, emphasizing the importance of optimized mix proportions. Further studies may focus on practical applications and long-term performance to promote the widespread adoption of FLGQ bricks in the construction industry.

Covariance data of experimental vs predicted strength.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to professors and parents for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout this research.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Pramod Sankar – responsible for the conceptualization of the study, conducting the investigation, and writing the original draft of the manuscript; Muthuswamy Saraswathi Ravi Kumar – provided supervision throughout the study, performed the formal analysis, and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data will be made available on request.

References

[1] Sufian, M., S. Ullah, K. A. Ostrowski, A. Ahmad, A. Zia, K. Śliwa-Wieczorek, et al. An experimental and empirical study on the use of waste marble powder in construction material. Materials, Vol. 14, No. 14, 2021, id. 3829.10.3390/ma14143829Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Thejas, H. K. and N. Hossiney. A short review on environmental impacts and application of iron ore tailings in the development of sustainable eco-friendly bricks. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 61, 2021, pp. 327–331.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.09.522Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Khan, Z., A. Gul, S. A. A. Shah, S. Qazi, N. Wahab, E. Badshah, et al. Utilization of marble wastes in clay bricks: a step towards lightweight energy-efficient construction materials. Civil Engineering Journal, Vol. 7, No. 9, 2021, pp. 1488–1500.10.28991/cej-2021-03091738Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Mohan, H. T., K. Jayanarayanan, and K. M. Mini. A sustainable approach for the utilization of PPE biomedical waste in the construction sector. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, Vol. 32, 2022, id. 101060.10.1016/j.jestch.2021.09.006Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Micheal, A. and R. R. Moussa. Investigating the economic and environmental effect of integrating sugarcane bagasse (SCB) fibres in cement bricks. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2021, pp. 3297–3303.10.1016/j.asej.2020.12.012Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Sidhu, B. S., A. S. Dhaliwal, K. S. Kahlon, and S. Singh. On the use of flyash-lime-gypsum (FaLG) bricks in the storage facilities for low-level nuclear waste. Nuclear Engineering and Technology, Vol. 54, No. 2, 2022, pp. 674–680.10.1016/j.net.2021.08.006Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Dutta, R. K., J. S. Yadav, V. N. Khatri, and G. Venkataraman. A study on the suitability of fly ash–lime–alccofine mixtures in the construction of road pavement. Transportation Infrastructure Geotechnology, Vol. 9, 2021, pp. 1–27.10.1007/s40515-021-00200-8Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Bernard, V. A. R., S. M. Renuka, S. Avudaiappan, C. Umarani, M. Amran, P. Guindos, et al. Performance investigation of the incorporation of ground granulated blast furnace slag with fly ash in autoclaved aerated concrete. Crystals, Vol. 12, No. 8, 2022, id. 1024.10.3390/cryst12081024Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Simão, F. V., H. Chambart, L. Vandemeulebroeke, P. Nielsen, L. R. Adrianto, S. Pfister, et al. Mine waste is a sustainable resource for facing bricks. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 368, 2022, id. 133118.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133118Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Khitab, A., M. S. Riaz, A. Jalil, R. B. N. Khan, W. Anwar, R. A. Khan, et al. Manufacturing of clayey bricks by the synergistic use of waste brick and ceramic powders as partial replacement of clay. Sustainability, Vol. 13, No. 18, 2021, id. 10214.10.3390/su131810214Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Mookherjee, M., D. Mainprice, K. Maheshwari, O. Heinonen, D. Patel, and A. Hariharan. Pressure induced elastic softening in framework aluminosilicate - albite (NaAlSi3O8). Scientific Reports, Vol. 6, 2016, id. 34815.10.1038/srep34815Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Garg, N. K., K. Vaishnav, and R. Negi. Investigation of concrete by using fly ash, GGBFS, quarry dust and recycle aggregate: a review. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering, Technology, and Science, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2021, pp. 929–941.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Soharu, A., N. BP, and A. Sil. Fly ash bricks development using concrete waste debris and self-healing bacteria. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2022, pp. 1037–1046.10.1007/s10163-022-01378-wSuche in Google Scholar

[14] Sithole, T., T. Mashifana, D. Mahlangu, and L. Tchadjié. Effect of binary combination of waste gypsum and fly ash to produce building bricks. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, Vol. 31, 2023, id. 100913.10.1016/j.scp.2022.100913Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Mukhtar, A., A. U. Qazi, Q. S. Khan, M. J. Munir, S. M. S. Kazmi, and A. Hameed. Feasibility of using coal ash for the production of sustainable bricks. Sustainability, Vol. 14, No. 11, 2022, id. 6692.10.3390/su14116692Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Waheed, A., R. Azam, M. R. Riaz, and M. Zawam. Mechanical and durability properties of fly-ash cement sand composite bricks: An alternative to conventional burnt clay bricks. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, Vol. 7, 2022, pp. 1–12.10.1007/s41062-021-00630-wSuche in Google Scholar

[17] Philip, S., A. Ajin, F. Shahul, L. Babu, and J. Tina. Fabrication and performance evaluation of lightweight eco-friendly construction bricks made with fly ash and bentonite. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, Vol. 8, No. 6, 2019, pp. 2090–2096.10.35940/ijeat.F8478.088619Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Premalatha, P. V., S. S. Kumar, C. S. Murali, and K. V. Aadithiya. Profound probing of Groundnut Shell Ash (GSA) as pozzolanic material in making innovative sustainable construction material. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 49, 2022, pp. 1275–1280.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.06.367Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Sharma, R. and H. Guleria. To study the basic geotechnical characteristics of fly ash lime gypsum composite with silty sand. International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, Vol. 11, No. 6, 2020, pp. 903–912.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Gourav, K. and B. V. Venkatarama Reddy. Characteristics of compacted fly ash brick masonry. Journal of Structural Engineering, Vol. 41, No. 2, June–July 2014, pp. 144–157.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Kumar, S. Fly ash-lime-phosphogypsum hollow blocks for walls and partitions. Building and Environment, Vol. 38, 2003, pp. 291–295.10.1016/S0360-1323(02)00068-9Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Kumar, S. A preservative study on fly ash-lime-gypsum bricks and hollow blocks for low-cost housing development. Construction and Building Material, Vol. 16, 2002, pp. 519–525.10.1016/S0950-0618(02)00034-XSuche in Google Scholar

[23] Sumathi, A. and K. Saravana Raja Mohan. Compressive strength of fly ash brick with the addition of lime, gypsum and quarry dust. International Journal of ChemTech Research , Vol. 7, No. 1, 2014–2015, pp. 28–36, CODEN (USA): IJCRGG ISSN:0974-4290.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Younis, M. O., M. Amin, and A. M. Tahwia. Durability and mechanical characteristics of sustainable self-curing concrete utilizing crushed ceramic and brick wastes. Case study in Construction Materials, Vol. 17, Dec 2022, id. e01251.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01251Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Shilar, F. A. and S. S. Quadri. Performance evaluation of interlocking bricks using granite waste powder. International Journal of Engineering Applied Sciences and Technology, Vol. 4, 2019, pp. 82–87.10.33564/IJEAST.2019.v04i02.014Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Chakradhara Rao, M. Influence of brick dust, stone dust and recycled fine dust on properties of natural and recycled aggregate concrete. Structural Concrete, Vol. 22, 2020, pp. 1–16suco.202000103.10.1002/suco.202000103Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Determination of compressive strength, water absorption, efflorescence, IS 3495-1 to 4, Bureau of Indian standards, New Delhi, 1992.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Bureau of Indian standard (IS 12894: 2002) pulverized fuel ash lime brick specifications.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Marinkovic, S. and A. Kostic-Pulek. Examination of the system fly ash-lime-calcined gypsum-water. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of solids p68, Vol. 68, 2007, pp. 1121–1125.10.1016/j.jpcs.2007.02.039Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Değirmenci, N. Utilization of phosphogypsum as raw and calcined material in manufacturing of building products. Construction and building material, Vol. 22, 2008, pp. 1857–1862.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.04.024Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Shen, W., M. Zhou, and Q. Zhao. Study on lime-fly ash-phosphogypsum binder. Construction and building material, Vol. 21, 2007, pp. 1480–1485.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.07.010Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Humphery, D. and A. Mary. Assessment of the quality of burnt bricks produced in Ghana: The case of Ashanti region. Case studies in construction material, Vol. 15, 2021, id. e00708.10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00708Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Sinkhonde, D., R. O. Onchiri, W. O. Oyawa, and J. N. Mwero. The behaviour of rubberized concrete with waste clay brick powder under varying curing conditions. Heliyon, Vol. 9, 2023, id. e13372.10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13372Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Mahdi, S. N., N. Hossiney, and M. M. A. B. Abdullah. Strength and durability property of Geopolymer paver blocks made with fly ash and brick kiln rice husk ash. Case studies in construction material, Vol. 16, 2022, id. e00800.10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00800Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Elahi, T. E., A. R. Shahriar, and M. S. Islam. Engineering characteristics of compressed earth blocks stabilised with cement and flyash. Construction and building material, Vol. 277, 2021, id. 122367.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122367Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Sharma, U., N. Gupta, and K. K. Saxena. Comparative study on the effect of industrial by-products as a replacement of cement in concrete. Materials Today: Online, Vol. 44, 2021, pp. 45–51.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.06.211Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Bureau of Indian standard (IS 5816: 1999) Splitting Tensile strength of concrete – Method of test.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Kannan Rajkumar, P. R., K. Divya Krishnan, C. Sudha, P. T. Ravichandran, and T. D. Vigneshwaran. Study on the use of industrial waste in preparation of green bricks. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 9, No. 5, Feb 2016.10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i5/87261Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Garg, M., M. Singh, and R. Kumar. Some aspects of the durability of a phosphogypsum-lime-fly ash binder. Construction of Building Material, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1996, pp. 274–279.10.1016/0950-0618(95)00085-2Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- De-chlorination of poly(vinyl) chloride using Fe2O3 and the improvement of chlorine fixing ratio in FeCl2 by SiO2 addition

- Reductive behavior of nickel and iron metallization in magnesian siliceous nickel laterite ores under the action of sulfur-bearing natural gas

- Study on properties of CaF2–CaO–Al2O3–MgO–B2O3 electroslag remelting slag for rack plate steel

- The origin of {113}<361> grains and their impact on secondary recrystallization in producing ultra-thin grain-oriented electrical steel

- Channel parameter optimization of one-strand slab induction heating tundish with double channels

- Effect of rare-earth Ce on the texture of non-oriented silicon steels

- Performance optimization of PERC solar cells based on laser ablation forming local contact on the rear

- Effect of ladle-lining materials on inclusion evolution in Al-killed steel during LF refining

- Analysis of metallurgical defects in enamel steel castings

- Effect of cooling rate and Nb synergistic strengthening on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-strength rebar

- Effect of grain size on fatigue strength of 304 stainless steel

- Analysis and control of surface cracks in a B-bearing continuous casting blooms

- Application of laser surface detection technology in blast furnace gas flow control and optimization

- Preparation of MoO3 powder by hydrothermal method

- The comparative study of Ti-bearing oxides introduced by different methods

- Application of MgO/ZrO2 coating on 309 stainless steel to increase resistance to corrosion at high temperatures and oxidation by an electrochemical method

- Effect of applying a full oxygen blast furnace on carbon emissions based on a carbon metabolism calculation model

- Characterization of low-damage cutting of alfalfa stalks by self-sharpening cutters made of gradient materials

- Thermo-mechanical effects and microstructural evolution-coupled numerical simulation on the hot forming processes of superalloy turbine disk

- Endpoint prediction of BOF steelmaking based on state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms

- Effect of calcium treatment on inclusions in 38CrMoAl high aluminum steel

- Effect of isothermal transformation temperature on the microstructure, precipitation behavior, and mechanical properties of anti-seismic rebar

- Evolution of residual stress and microstructure of 2205 duplex stainless steel welded joints during different post-weld heat treatment

- Effect of heating process on the corrosion resistance of zinc iron alloy coatings

- BOF steelmaking endpoint carbon content and temperature soft sensor model based on supervised weighted local structure preserving projection

- Innovative approaches to enhancing crack repair: Performance optimization of biopolymer-infused CXT

- Structural and electrochromic property control of WO3 films through fine-tuning of film-forming parameters

- Influence of non-linear thermal radiation on the dynamics of homogeneous and heterogeneous chemical reactions between the cone and the disk

- Thermodynamic modeling of stacking fault energy in Fe–Mn–C austenitic steels

- Research on the influence of cemented carbide micro-textured structure on tribological properties

- Performance evaluation of fly ash-lime-gypsum-quarry dust (FALGQ) bricks for sustainable construction

- First-principles study on the interfacial interactions between h-BN and Si3N4

- Analysis of carbon emission reduction capacity of hydrogen-rich oxygen blast furnace based on renewable energy hydrogen production

- Just-in-time updated DBN BOF steel-making soft sensor model based on dense connectivity of key features

- Effect of tempering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Q125 shale gas casing steel

- Review Articles

- A review of emerging trends in Laves phase research: Bibliometric analysis and visualization

- Effect of bottom stirring on bath mixing and transfer behavior during scrap melting in BOF steelmaking: A review

- High-temperature antioxidant silicate coating of low-density Nb–Ti–Al alloy: A review

- Communications

- Experimental investigation on the deterioration of the physical and mechanical properties of autoclaved aerated concrete at elevated temperatures

- Damage evaluation of the austenitic heat-resistance steel subjected to creep by using Kikuchi pattern parameters

- Topical Issue on Focus of Hot Deformation of Metaland High Entropy Alloys - Part II

- Synthesis of aluminium (Al) and alumina (Al2O3)-based graded material by gravity casting

- Experimental investigation into machining performance of magnesium alloy AZ91D under dry, minimum quantity lubrication, and nano minimum quantity lubrication environments

- Numerical simulation of temperature distribution and residual stress in TIG welding of stainless-steel single-pass flange butt joint using finite element analysis

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part I

- Electro-thermal performance evaluation of a prismatic battery pack for an electric vehicle

- Experimental analysis and optimization of machining parameters for Nitinol alloy: A Taguchi and multi-attribute decision-making approach

- Experimental and numerical analysis of temperature distributions in SA 387 pressure vessel steel during submerged arc welding

- Optimization of process parameters in plasma arc cutting of commercial-grade aluminium plate

- Multi-response optimization of friction stir welding using fuzzy-grey system

- Mechanical and micro-structural studies of pulsed and constant current TIG weldments of super duplex stainless steels and Austenitic stainless steels

- Stretch-forming characteristics of austenitic material stainless steel 304 at hot working temperatures

- Work hardening and X-ray diffraction studies on ASS 304 at high temperatures

- Study of phase equilibrium of refractory high-entropy alloys using the atomic size difference concept for turbine blade applications

- A novel intelligent tool wear monitoring system in ball end milling of Ti6Al4V alloy using artificial neural network

- A hybrid approach for the machinability analysis of Incoloy 825 using the entropy-MOORA method

- Special Issue on Recent Developments in 3D Printed Carbon Materials - Part II

- Innovations for sustainable chemical manufacturing and waste minimization through green production practices

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part I

- Characterization of Co–Ni–TiO2 coatings prepared by combined sol-enhanced and pulse current electrodeposition methods

- Hot deformation behaviors and microstructure characteristics of Cr–Mo–Ni–V steel with a banded structure

- Effects of normalizing and tempering temperature on the bainite microstructure and properties of low alloy fire-resistant steel bars

- Dynamic evolution of residual stress upon manufacturing Al-based diesel engine diaphragm

- Study on impact resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete after exposure to fire

- Bonding behaviour between steel fibre and concrete matrix after experiencing elevated temperature at various loading rates

- Diffusion law of sulfate ions in coral aggregate seawater concrete in the marine environment

- Microstructure evolution and grain refinement mechanism of 316LN steel

- Investigation of the interface and physical properties of a Kovar alloy/Cu composite wire processed by multi-pass drawing

- The investigation of peritectic solidification of high nitrogen stainless steels by in-situ observation

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of submerged arc welded medium-thickness Q690qE high-strength steel plate joints

- Experimental study on the effect of the riveting process on the bending resistance of beams composed of galvanized Q235 steel

- Density functional theory study of Mg–Ho intermetallic phases

- Investigation of electrical properties and PTCR effect in double-donor doping BaTiO3 lead-free ceramics

- Special Issue on Thermal Management and Heat Transfer

- On the thermal performance of a three-dimensional cross-ternary hybrid nanofluid over a wedge using a Bayesian regularization neural network approach

- Time dependent model to analyze the magnetic refrigeration performance of gadolinium near the room temperature

- Heat transfer characteristics in a non-Newtonian (Williamson) hybrid nanofluid with Hall and convective boundary effects

- Computational role of homogeneous–heterogeneous chemical reactions and a mixed convective ternary hybrid nanofluid in a vertical porous microchannel

- Thermal conductivity evaluation of magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluid and dusty particles with thermal radiation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- De-chlorination of poly(vinyl) chloride using Fe2O3 and the improvement of chlorine fixing ratio in FeCl2 by SiO2 addition

- Reductive behavior of nickel and iron metallization in magnesian siliceous nickel laterite ores under the action of sulfur-bearing natural gas

- Study on properties of CaF2–CaO–Al2O3–MgO–B2O3 electroslag remelting slag for rack plate steel

- The origin of {113}<361> grains and their impact on secondary recrystallization in producing ultra-thin grain-oriented electrical steel

- Channel parameter optimization of one-strand slab induction heating tundish with double channels

- Effect of rare-earth Ce on the texture of non-oriented silicon steels

- Performance optimization of PERC solar cells based on laser ablation forming local contact on the rear

- Effect of ladle-lining materials on inclusion evolution in Al-killed steel during LF refining

- Analysis of metallurgical defects in enamel steel castings

- Effect of cooling rate and Nb synergistic strengthening on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-strength rebar

- Effect of grain size on fatigue strength of 304 stainless steel

- Analysis and control of surface cracks in a B-bearing continuous casting blooms

- Application of laser surface detection technology in blast furnace gas flow control and optimization

- Preparation of MoO3 powder by hydrothermal method

- The comparative study of Ti-bearing oxides introduced by different methods

- Application of MgO/ZrO2 coating on 309 stainless steel to increase resistance to corrosion at high temperatures and oxidation by an electrochemical method

- Effect of applying a full oxygen blast furnace on carbon emissions based on a carbon metabolism calculation model

- Characterization of low-damage cutting of alfalfa stalks by self-sharpening cutters made of gradient materials

- Thermo-mechanical effects and microstructural evolution-coupled numerical simulation on the hot forming processes of superalloy turbine disk

- Endpoint prediction of BOF steelmaking based on state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms

- Effect of calcium treatment on inclusions in 38CrMoAl high aluminum steel

- Effect of isothermal transformation temperature on the microstructure, precipitation behavior, and mechanical properties of anti-seismic rebar

- Evolution of residual stress and microstructure of 2205 duplex stainless steel welded joints during different post-weld heat treatment

- Effect of heating process on the corrosion resistance of zinc iron alloy coatings

- BOF steelmaking endpoint carbon content and temperature soft sensor model based on supervised weighted local structure preserving projection

- Innovative approaches to enhancing crack repair: Performance optimization of biopolymer-infused CXT

- Structural and electrochromic property control of WO3 films through fine-tuning of film-forming parameters

- Influence of non-linear thermal radiation on the dynamics of homogeneous and heterogeneous chemical reactions between the cone and the disk

- Thermodynamic modeling of stacking fault energy in Fe–Mn–C austenitic steels

- Research on the influence of cemented carbide micro-textured structure on tribological properties

- Performance evaluation of fly ash-lime-gypsum-quarry dust (FALGQ) bricks for sustainable construction

- First-principles study on the interfacial interactions between h-BN and Si3N4

- Analysis of carbon emission reduction capacity of hydrogen-rich oxygen blast furnace based on renewable energy hydrogen production

- Just-in-time updated DBN BOF steel-making soft sensor model based on dense connectivity of key features

- Effect of tempering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Q125 shale gas casing steel

- Review Articles

- A review of emerging trends in Laves phase research: Bibliometric analysis and visualization

- Effect of bottom stirring on bath mixing and transfer behavior during scrap melting in BOF steelmaking: A review

- High-temperature antioxidant silicate coating of low-density Nb–Ti–Al alloy: A review

- Communications

- Experimental investigation on the deterioration of the physical and mechanical properties of autoclaved aerated concrete at elevated temperatures

- Damage evaluation of the austenitic heat-resistance steel subjected to creep by using Kikuchi pattern parameters

- Topical Issue on Focus of Hot Deformation of Metaland High Entropy Alloys - Part II

- Synthesis of aluminium (Al) and alumina (Al2O3)-based graded material by gravity casting

- Experimental investigation into machining performance of magnesium alloy AZ91D under dry, minimum quantity lubrication, and nano minimum quantity lubrication environments

- Numerical simulation of temperature distribution and residual stress in TIG welding of stainless-steel single-pass flange butt joint using finite element analysis

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part I

- Electro-thermal performance evaluation of a prismatic battery pack for an electric vehicle

- Experimental analysis and optimization of machining parameters for Nitinol alloy: A Taguchi and multi-attribute decision-making approach

- Experimental and numerical analysis of temperature distributions in SA 387 pressure vessel steel during submerged arc welding

- Optimization of process parameters in plasma arc cutting of commercial-grade aluminium plate

- Multi-response optimization of friction stir welding using fuzzy-grey system

- Mechanical and micro-structural studies of pulsed and constant current TIG weldments of super duplex stainless steels and Austenitic stainless steels

- Stretch-forming characteristics of austenitic material stainless steel 304 at hot working temperatures

- Work hardening and X-ray diffraction studies on ASS 304 at high temperatures

- Study of phase equilibrium of refractory high-entropy alloys using the atomic size difference concept for turbine blade applications

- A novel intelligent tool wear monitoring system in ball end milling of Ti6Al4V alloy using artificial neural network

- A hybrid approach for the machinability analysis of Incoloy 825 using the entropy-MOORA method

- Special Issue on Recent Developments in 3D Printed Carbon Materials - Part II

- Innovations for sustainable chemical manufacturing and waste minimization through green production practices

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part I

- Characterization of Co–Ni–TiO2 coatings prepared by combined sol-enhanced and pulse current electrodeposition methods

- Hot deformation behaviors and microstructure characteristics of Cr–Mo–Ni–V steel with a banded structure

- Effects of normalizing and tempering temperature on the bainite microstructure and properties of low alloy fire-resistant steel bars

- Dynamic evolution of residual stress upon manufacturing Al-based diesel engine diaphragm

- Study on impact resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete after exposure to fire

- Bonding behaviour between steel fibre and concrete matrix after experiencing elevated temperature at various loading rates

- Diffusion law of sulfate ions in coral aggregate seawater concrete in the marine environment

- Microstructure evolution and grain refinement mechanism of 316LN steel

- Investigation of the interface and physical properties of a Kovar alloy/Cu composite wire processed by multi-pass drawing

- The investigation of peritectic solidification of high nitrogen stainless steels by in-situ observation

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of submerged arc welded medium-thickness Q690qE high-strength steel plate joints

- Experimental study on the effect of the riveting process on the bending resistance of beams composed of galvanized Q235 steel

- Density functional theory study of Mg–Ho intermetallic phases

- Investigation of electrical properties and PTCR effect in double-donor doping BaTiO3 lead-free ceramics

- Special Issue on Thermal Management and Heat Transfer

- On the thermal performance of a three-dimensional cross-ternary hybrid nanofluid over a wedge using a Bayesian regularization neural network approach

- Time dependent model to analyze the magnetic refrigeration performance of gadolinium near the room temperature

- Heat transfer characteristics in a non-Newtonian (Williamson) hybrid nanofluid with Hall and convective boundary effects

- Computational role of homogeneous–heterogeneous chemical reactions and a mixed convective ternary hybrid nanofluid in a vertical porous microchannel

- Thermal conductivity evaluation of magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluid and dusty particles with thermal radiation