Abstract

Farmer regeneration in agribusiness sustainability originates from the innovation of knowledge co-creation among farmer generations and interaction between stakeholders within and outside local contexts. The present work aims at exploring knowledge co-creation in the context of different orientations between young and old farmers. It also seeks to characterize the orientation of the two farmer groups from the aspect of agriculture, processing, and marketing of coconut through knowledge co-creation interaction to further their agricultural activities. All data in this grounded theory research came from in-depth interviews; the data were further examined using an open, axial, and selective coding method. The transcription of the field note was analyzed using an ATLAS.ti version 9, a program for analyzing qualitative data. The sample of the study was 13 of young farmers (25 to 45 years old) and 17 of old farmers (45 to 65 years old). The results revealed that the old farmers focused on revitalizing coconut trees for long-term purposes. The knowledge co-creation process among this farmer group (with other stakeholders) put an emphasis on copra and cooking oil production. Young farmers, however, focused on coconut tree integration with annual plants for short-term purposes, especially on the virgin coconut oil and innovative products from foreign technology adaptation. In conclusion, coconut business sustainability is the byproduct of knowledge co-creation and engagement between old and young farmers. This condition results in the survivability of coconut farmers. The novelty of this study lies in the classification of the orientation of the two coconut farmer groups in terms of agricultural, processing, and marketing aspects, which results in knowledge co-creation and its relation to the sustainability of coconut agriculture.

1 Introduction

The model of the peasantry is known as the appearance of a new generation of farmers who continue to struggleautonomy, including coaching, maintenance, and courtesy resource-based with self-driven narratives of experience and knowledge [1]. It is worth noting that the term autonomy, in this concept, does not refer to production in a balanced situation. Rather, such a concept is depicted as an entrepreneurial process that results in distinctive, recognizable, and competitive products [2]. In the entrepreneurial decision by the new peasant generation, knowledge and its sources are essential factors that need to be discussed in the context of farmers’ interactions with various stakeholders [3].

Various studies have identified the relationship between knowledge and agricultural practice. Authors of ref. [4] assert that agricultural development is closely related to knowledge change, shared learning, and knowledge co-creation. Authors of refs [5,6] argue that the incorporation between the types of knowledge and shared learning resulting in new knowledge through multi-stakeholder interactions can change the behavior, practices, policies, and institutions. They further add that changes at the farmer level can improve the livelihood system. Authors of ref. [7] state that farmers contribute more to the social and independent learning system than the learning system accessed through a formal institution [7]. Still, it is worth noting that little is known regarding the correlation between knowledge development and knowledge co-creation in the farmer regeneration context. The context of farmer regeneration is of paramount importance in the study of knowledge co-creation due to differences in perceptions about employment in the agricultural sector between old farmers (who consider agriculture to be an occupation for low social strata) and young farmers (who perceive agricultural occupation as an opportunity, especially if they can take advantage of information) [8]. The present work is similar to previous studies in terms of the exploration of farmers’ interaction that creates knowledge co-creation. The difference between this research and the previous studies lies in the identification of behavior orientation between old farmers and young farmers and the sustainability of coconut farming due to the interrelation between the two farmer groups in the cultivation, process, and marketing of coconut products. This interrelation between the farmer groups leads to knowledge co-creation that is central to coconut farming sustainability. Determining the research participants (old farmers and young farmers) was challenging, especially in collecting data from the interview. The challenge was due to the disparity in knowledge and experience between the two farmer groups, resulting in the inability of the subjects to provide information relevant to the research theme. Furthermore, the restriction due to the covid-19 pandemic hindered the author from meeting the informants in person. As a result, phone interview sessions were performed, where all information was recorded and transcribed. Several key actors and facilitators involved in mentoring programs were also interviewed, including representatives from Central Bank of Indonesia Gorontalo Representative, the Agricultural Technology Assessment Agency (BPTP) of Gorontalo, and the National Support For Local Investment (NSLIC) program. Researchers from universities investigating coconut and other themes related to the theme of the present work were also involved as the informant.

In Indonesia, coconut farming is unique since the expansion of oil palm as a source of cooking oil does not affect the coconut business. Many have produced diversified products, such as virgin coconut oil. This condition confirms innovation through knowledge co-creation between coconut farmers, such as in Gorontalo, Indonesia. In this province, the coconut plantation area increased to 68.975 in 2020 from 67.495 in 2018 [9]. The production of coconut commodities also saw a rise to 57.974 in 2020 from 55.946 in 2018 [10]. This confirms that local communities in the province favor coconut. This condition resonates with the results of NSLIC [11] confirming that coconut is the primary commodity mostly grown by many farmers. Some grow coconut using a monoculture approach, while others incorporate other crops in the cultivation. NSLIC [11] estimates the population of coconut farmers in Gorontalo Province as 55,552 individuals; the majority of farmers are in Gorontalo regency and Pohuwato regency.

Knowledge co-creation, in this study, is defined as the interaction between scientific knowledge and public knowledge in which novelty emerges as a result of a shared evolutionary process [12,13]. Lying within this process is the interconnection between knowledge and decision-making [14]. Knowledge co-creation can also be defined as a repetitive and collaborative process involving expertise and actors in formulating specific knowledge for sustainable systems [15]. The process incorporates a mechanism of uniting ideas from different actors to come up with innovative solutions [16]. Knowledge co-creation between fellow farmers or between farmers and other parties occurs due to farmers’ interaction with technology developers, including experiments based on farmers’ experience [17–19].

This research discusses knowledge co-creation in the context of different orientations between new and old farmers. Further, this research also aims to characterize the orientation of the two farmer groups from agriculture, processing, and marketing of coconut. Knowledge co-creation among young farmers, old farmers, and both are also explored. Following the research method section below is the finding explaining the difference between the orientation of old farmers and young farmers, and the co-creation processes involving these two farmer groups.

Constructing field contexts and phenomena related to the research topic is a rigorous task, particularly in producing action-oriented categorizations and interactions between old farmers and young farmers in producing knowledge co-creation. This is because of the different characteristics of the two farmer groups, involving age, land area, farming experience, and cosmopolitan aspect. This difference becomes one of the research gaps that need to be addressed, i.e., whether the new knowledge co-creation resulted from the interaction and engagement of old farmers and young farmers or other external factors’ influence. On that ground, this study aims to address the gap in the literature by identifying and categorizing action orientations between old and young farmers in several aspects, such as cultivation, process, and marketing of coconut farming. The dynamics and structural factors in old farmers and young farmers are also contributing factors to knowledge co-creation.

2 Materials and methods

This qualitative research employed a grounded theory method. The reason for selecting this method is to formulate a general and abstract theory based on processes, actions, or interactions in social reality [20].

The sample involved coconut farmers with business scopes in cultivation, processing, and marketing. In categorizing the farmers, the present work applied a model by Statistics Indonesia: old farmers are aged 46–65 years and young farmers involve individuals aged 25–45 years. All samples were from nine districts in Gorontalo regency, i.e., Telaga Biru, Limboto, Limboto Barat, Tibawa, Pulubala, Bongomeme, Dungaleya, Tabongo, and Batudaa (Map 1) (Figure 1).

Research site map (source: http://www.disdukcapil-gorontalokab.web.id).

The data were analyzed using open, axial, and selective coding as Corbin and Strauss [20] proposed. Fragments from interviews related to the research focus were selected in the open coding. These fragments were coded based on the relevant concept. Following the open coding was the axial coding in producing a specific category. Bertolozzi-Caredio et al. [21] defined axial coding as a step of processing open coding outputs through deletion, purification, and integration of open coding outputs, resulting in more comprehensive and meaningful data. In axial coding, a category is linked with sub-categories and tested with data before building relationships between the categories [20]. The accuracy of the sub-categories is checked by locking the relevant statements with the sub-categories for the sample [22]. Selective coding was conducted by utilizing the output of axial coding. Further, the relationship between categories was built according to the focus of the research.

Observations and interviews were conducted from April to September 2021, involving 43 coconut farmers. Information from observations and unstructured interviews was then transcribed. Following the process was the coding phase to extract categories from the transcription of field note data. Axial coding was also performed to identify the relation between the category. The core categories were identified and described in the third phase, selective coding [23]. This process identified 30 farmers with statements relevant to the research topic. Field note data and transcripts of 30 farmers were examined through interviews to confirm information related to the problems and research objectives. As many as 17 old farmers and 13 young farmers involved in the cultivation, process, and marketing of coconut farming were interviewed. They were selected after the data were considered saturated, i.e., where no new information is obtained from the sample during the interview [24]. In the interview, open questions were asked before proceeding to structured questions as based on the research topic; the interview took 30–75 min. Furthermore, all answers from the participants were recorded and transcribed.

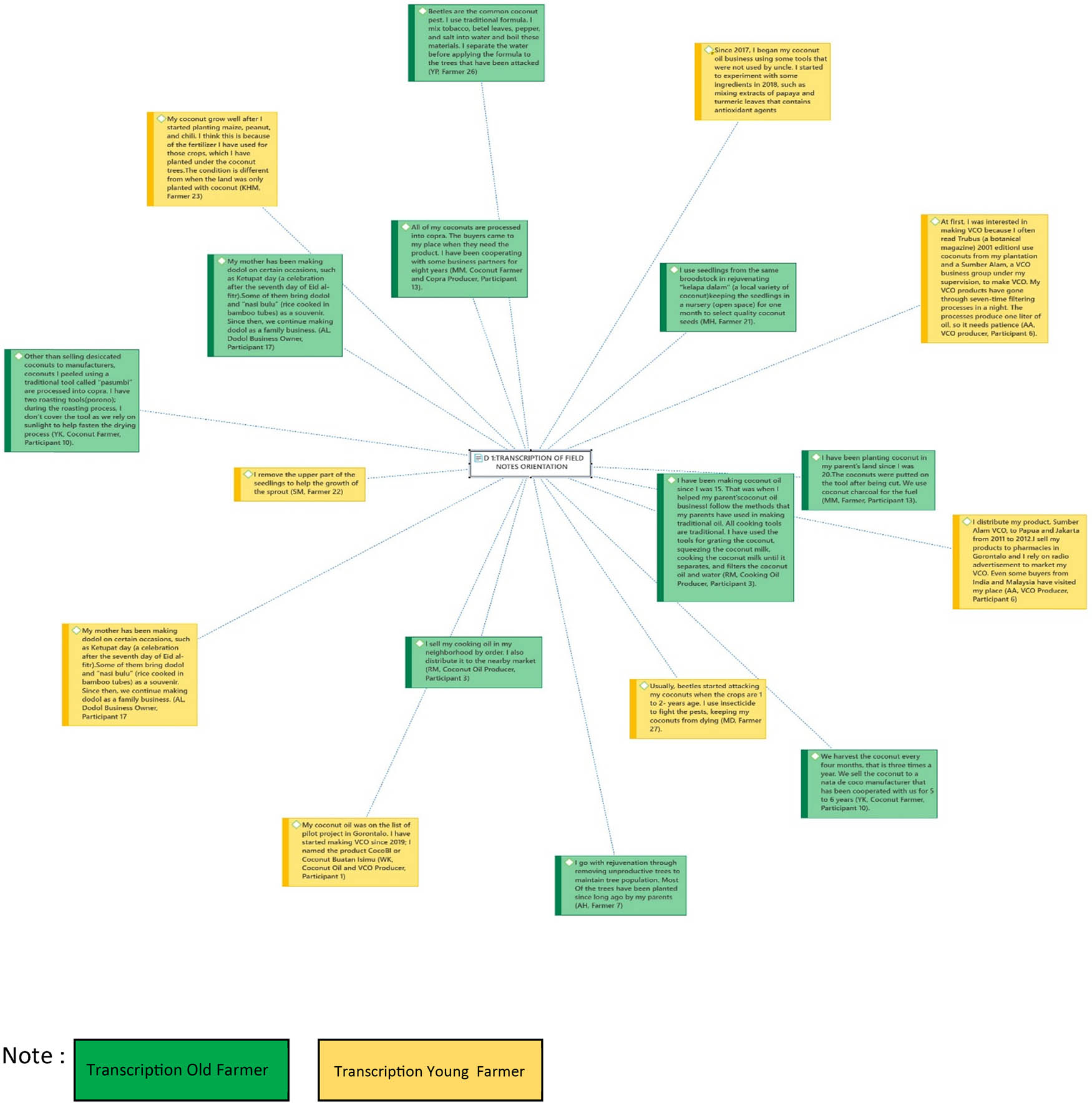

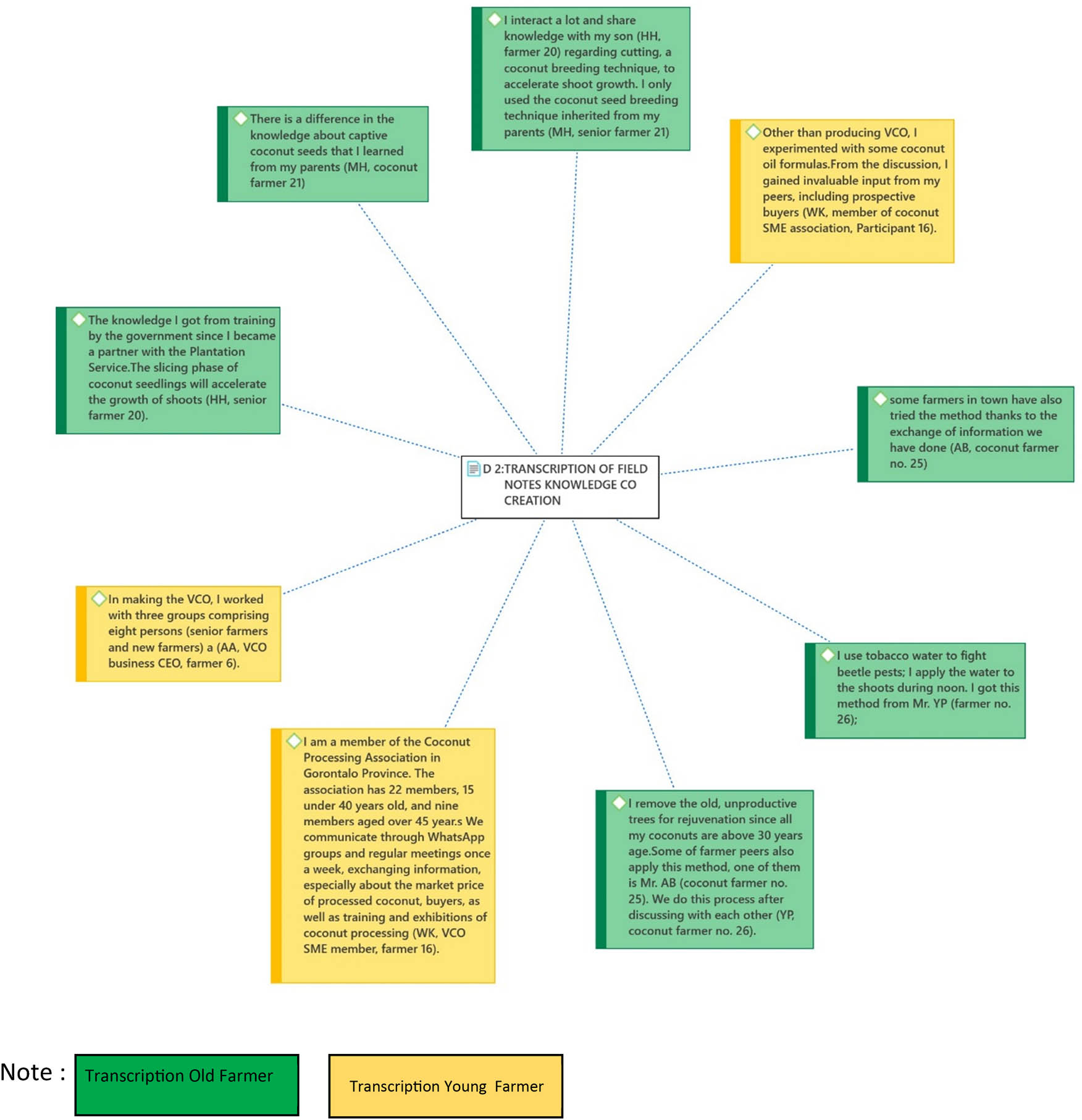

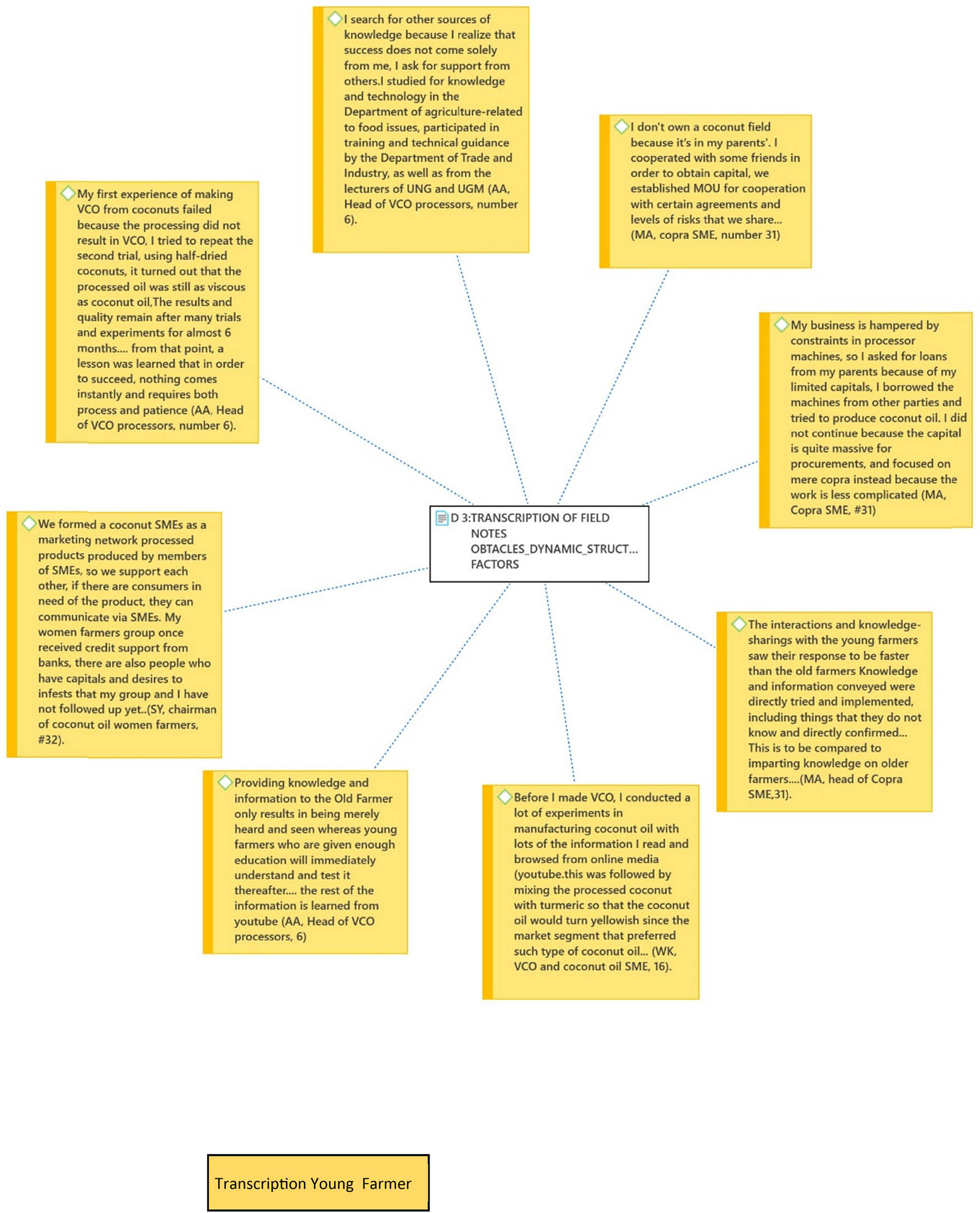

Interview data included transcripts of field notes, video recordings, audio, media news, expert statements, articles, and books. All data were processed using the ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software version 9. This application aims to help with the coding of the transcription of field notes [25].

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

3 Results

This study successfully identifies the difference in orientation between old farmers and young farmers in coconut agribusiness; the orientation covers three aspects, i.e., cultivation, product processing, and marketing. All characterizations of the orientation of the two farmer groups are displayed in Table 1.

Characteristics of orientation of old farmers and young farmers in coconut agribusiness

| Aspects of coconut Farming Management | Orientation Pattern | |

|---|---|---|

| Old farmer | Young farmer | |

| Coconut farming | Cutting and removal of old, senile, unproductive, and disease-advanced trees to maintain the tree population and crop productivity | In addition to cutting and removing the unproductive trees, other commodities were planted in between the coconut trees to earn additional income |

| The selection of quality seedlings is performed by putting down the seed-nut in a nursery | The selection of seedlings is performed by removing the upper part of the coconut seed to allow the sprout growth | |

| Pest control processes rely on local pesticides and traditional techniques | Pest control processes are performed by spraying insecticides | |

| Crop processing | Relying on mainstream crop processing (i.e., methods that have been passed from generation); the products involve conventional copra, shell charcoal, and coconut oil | Creating innovative product, e.g., virgin coconut oil (VCO), white copra, briquette, soap, traditional coconut oil (processed using advanced technology) |

| Product marketing | Relying on the existing copra market chain through distributing the product to the collecting traders in the village; the fresh coconut fruits are distributed to the manufacturers | Relying on multiple market chains through coconut small and medium enterprises (SMEs), selling products in coconut fairs, and exporting the coconut |

3.1 Orientation differences between old farmers and young farmers

3.1.1 Cultivation

Old farmers, in sustaining their coconut cultivation, apply the concept of long-term orientation, i.e., performing rejuvenation processes to 40–50-year old trees that are less productive. According to the interview, the farmers prefer to stick with maintaining their coconut tree population, in terms of the land area and the production. This is done through removing the old, unproductive tree, selecting coconut seedlings, and pest management; see interview excerpts below.

“I go with rejuvenation through removing unproductive trees to maintain tree population, because most of the trees have been planted since long ago by my parents.” AH, Farmer 7

“I use seedlings from the same broodstock in rejuvenating “kelapa dalam” (a local variety of coconut) and keeping the seedlings in a nursery (open space) for one month to select quality coconut seeds.” MH, Farmer 21

“Beetles are the common coconut pest. I use traditional formula. I mix tobacco, betel leaves, pepper, and salt into water and boil these materials. I separate the water before applying the formula to the trees that have been attacked.” YP, Farmer 26

Young farmers have different perspective in coconut cultivation compared to old farmers. They optimize their planting area by cultivating other commodities, such as maize, peanut, and chili, as intercrops (they plant it under coconut trees) to earn extra income. In cultivation aspects, young farmers opt to remove the upper part of coconut fruit to optimize the growth of the sprout. They prefer insecticide in combatting beetle; this is performed when the coconut is 1–2 years of age. Below are interview excerpts regarding the orientation of young farmers regarding coconut cultivation.

“My coconut grow well after I started planting maize, peanut, and chili. I think this is because of the fertilizer I have used for those crops, which I have planted under the coconut trees. The condition is different from when the land was only planted with coconut.” KHM, Farmer 23

“I remove the upper part of the seedlings to help the growth of the sprout.” SM, Farmer 22

“Usually, beetles started attacking my coconuts when the crops are 1 to 2-years age. I use insecticide to fight the pests, keeping my coconuts from dying.” MD, Farmer 27

3.1.2 Processing

The way young farmers process coconut products differs from that of the old farmers. In general, old farmers process coconuts into oil, copra, and charcoal using traditional methods. They prefer methods that have been passed from generation; see the excerpts below.

“I have been making coconut oil since I was 15. That was when I helped my parent’s coconut oil business. I follow the methods that my parents have used in making traditional oil. All cooking tools are traditional. I have used the tools for grating the coconut, squeezing the coconut milk, cooking the coconut milk until it separates, and filters the coconut oil and water.” RM, Coconut Cooking Oil Maker, Participant 3

“I have been planting coconut in my parent’s land since I was 20. The fruits are processed into copra using the traditional roasting tools called “porono” since 2010. The coconuts were putted on the tool after being cut. We use coconut charcoal for the fuel.” MM, Farmer, Participant 13

“Other than selling desiccated coconuts to manufacturers, coconuts I peeled using a traditional tool called “pasumbi” are processed into copra. I have two roasting tools (porono); during the roasting process, I don’t cover the tool as we rely on sunlight to help fasten the drying process.” YK, Coconut Farmer, Participant 10

Young farmers are more creative when it comes to meeting market demands. They process the coconuts into VCO, briquette, cookies, cooking oil, and “dodol” (a sweet toffee-like sugar palm-based confection) made of coconut milk. Based on the notion, it can be said that the young farmers are keen on the opportunity and prospects of coconut products. Interaction with coconut producer association is among the key to obtaining information regarding coconut product commodities in domestic and international markets. Such is evident from the interview transcript below.

“At first, I was interested in making VCO because I often read Trubus (a botanical magazine) 2001 edition. Then, I tried everything I have read, where the VCO product is better than local products. I use coconuts from my plantation and a Sumber Alam, a VCO business group under my supervision, to make VCO. My VCO products have gone through seven-time filtering processes in a night. The processes produce one liter of oil, so it needs patience.” AA, VCO producer, Participant 6

Young farmers tend to experiment with a lot of processes, such as adding antioxidant agents, e.g., papaya and turmeric leaves into cooking oils in order to fulfill market demands. This is based on the interview with several producers of cooking oil and VCO.

“Since 2017, I began my coconut oil business using some tools that were not used by uncle. I started to experiment with some ingredients in 2018, such as mixing extracts of papaya and turmeric leaves that contains antioxidant agents. My coconut oil was on the list of pilot project in Gorontalo. I have started making VCO since 2019; I named the product CocoBI or Coconut Buatan Isimu.” WK, Coconut Oil and VCO Producer, Participant 16

Some differences are noted in terms of the production aspect between young farmers and old farmers, despite the similarity shared between the two farmers, i.e., both run a family business. In this research, one example is adding coconut milk to “dodol” product as stated by AL, the owner of dodol business.

“My mother has been making dodol on certain occasions, such as Ketupat day (a celebration after the seventh day of Eid al-fitr). She made the snack for the guests, family, and relatives when they visited our house. Some of them bring dodol and “nasi bulu” (rice cooked in bamboo tubes) as a souvenir. Since then, we continue making dodol as a family business.” AL, Dodol Business Owner, Participant 17

3.1.3 Marketing

Young farmers and old farmers have differing perspectives in terms of marketing orientation. Old farmers tend to sell their coconut products in the form of copra, charcoal, traditional coconut oil, and coconut fruit to collecting traders in the town or manufacturers. This is based on the interview data.

“I sell my coconut cooking oil in my neighborhood by order. I also distribute it to the nearby market.” RM, Coconut Oil Producer, Participant 3

“All of my coconuts are processed into copra. The buyers came to my place when they need the product. I have been cooperating with some business partners for eight years.” MM, Coconut Farmer and Copra Producer, Participant 13

“We harvest the coconut every four months, that is three times a year. We sell the coconut to a nata de coco manufacturer that has been cooperated with us for 5 to 6 years.” YK, Coconut Farmer, Participant 10

Young generation of farmers create innovation in marketing their coconut products. They rely on radio advertisement, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), coconut partnership association, and coconut fairs (local and international) through business network they have built when participating in workshops or seminars. This finding is based on the interview transcript below.

“I distribute my VCO product to local market and Surabaya through SMEs association; we support each other in the association. The association offers wide range of coconut products, such as VCO, briquette, traditional coconut oil, soap, charcoal, and white copra. The distribution of the products is managed by the association members depending on the market demand. I also often participate in coconut fairs in Gorontalo, Jakarta, and Surabaya.” WK, VCO Producer, Participant 16

“I distribute my product, Sumber Alam VCO, to Papua and Jakarta from 2011 to 2012. In local markets, I sell my products to pharmacies in Gorontalo and I rely on radio advertisement to market my VCO. Even some buyers from India and Malaysia have visited my place.” AA, VCO Producer, Participant 6

Cultivation, process, and marketing aspects between the young and old generation of farmers differ from one another. Old farmers focus on coconut rejuvenation and coconut population sustainability to maintain their income. On the other hand, young farmers opt to earn income outside of coconuts by planting seasonal crops as intercrops, including corn, chilies and peanuts. Differences in the orientation of farmers’ actions can also be seen in the processing aspect. Old farmers rely on conventional tools that have been used from generation to generation, while young farmers are capable of adjusting themselves with technology advancement, which enables them to produce high economic value products according to market demands, including virgin coconut oil, white copra, coconut flour, coconut milk briquettes, coconut cooking oil, soap, and coconut shell charcoal. This condition occurs since young farmers do not have a choice in rejuvenating coconuts as many coconut plantations are owned by old farmers. The data by BPS Gorontalo Province [10] (not published) confirm the situation mentioned earlier, where old farmers owning coconut land and participating in a coconut rejuvenation program account for 56.49%, and young farmers participating in the program account for 43.15%. Another contributing factor is that the majority of agriculture land is dominated by maize farmers, where the total land area for this commodity is 284824.5 hectare, outnumbering the coconut plantation with just 449 hectare [9].

In marketing aspects, old farmers continue the existing market chain, selling their product to the returning consumers, e.g., collecting traders or manufacturers. Young farmers have multiple approaches in selling their products, relying on their access to the updated information in coconut market. This finding is in accordance with the peasantry model of van der Ploeg [1] regarding the existence of a new peasant generation that autonomously struggles and survives to manage natural resources (in this case coconut land). Similarly, the finding resonates with the results seen in ref. [2], reporting that the new peasant generation exercises autonomy in natural resource management through entrepreneurial which enables it to produce distinctive, recognizable, and competitive products in the market. Conclusion of authors of ref. [2] is in line with the finding seen in ref. [26] in which the orientation of old farmers in Thailand tends to be less innovative and less-productive in agricultural practices. It is due to their reluctance to invest in agriculture and inability to delegate family members to continue their business after retirement. On the other hand, the orientation of young farmers is emphasized more on innovative agricultural practices, involving the investment in capital and the use of technology, e.g., greenhouses with drip irrigation or hydroponic technology.

3.2 Knowledge co-creation between old farmers and young farmers

Processes of knowledge co-creation between two generations of farmers take place due to the interaction of ideas and knowledge, resulting in new knowledge. Other parties are also involved in the information exchange that encompasses agricultural, product process, and marketing aspects to come up with innovation in coconut farming. All ideas and information from the experience of a farmer are then implemented by other farmers. The present work explores the process of knowledge co-creation among old farmers, among young farmers, and between the two farmer generations. Provided in Table 2 is the category of knowledge co-creation process.

Knowledge co-creation between old farmers and young farmers in coconut agribusiness

| Generation category | Knowledge co-creation characteristics |

|---|---|

| Among old farmers | Knowledge co-creation is incorporated in removal of unproductive tree, seed planting, and pest management. |

| Among young farmers | Knowledge co-creation concepts are seen in the variants of coconut products and packaging |

| Inter-generation | Knowledge co-creation concepts are seen in seed breeding and product processing |

3.2.1 Knowledge co-creation among old farmers

Knowledge co-creation among old farmers revolve around their experience or everything they have learned from their parents. This interaction generates new ideas that they implement in their business. Following this process is the discussion of the implementation outcomes. Knowledge co-creation in cultivation aspect is seen from the interview excerpts below.

“I remove the old, unproductive trees for rejuvenation since all my coconuts are above 30 years age. I use “lima dobol” technique, that is replacing the old trees with the new ones, putting the trees between the unproductive trees to get optimum sunlight. Some of farmer peers also apply this method, one of them is Mr. AB (coconut farmer no. 25). We do this process after discussing with each other.” YP, coconut farmer no. 26

“I use tobacco water to fight beetle pests; I apply the water to the shoots during noon. I got this method from Mr. YP (farmer no. 26); some farmers in town have also tried the method thanks to the exchange of information we have done.” AB, coconut farmer no. 25

3.2.2 Knowledge co-creation among young farmers

Young farmers focus on production and marketing aspect in information exchange. Such interaction results in innovation of new products as seen in the transcript of interview with young farmers below This is seen in the following interview data.

“Other than making VCO, I experiment with some formula in making coconut oil. For example, I add papaya leaves and turmeric extracts into the oil as they contain antioxidant agents. I discuss my experiment in a coconut SME forum. From the discussion, I gain invaluable inputs from my peers, including information of prospective buyers.” WK, member of coconut SME association, Participant 16

3.2.3 Knowledge co-creation between old farmers and young farmers

Cultivation, process, and marketing aspects are the topics covered in knowledge co-creation between the young and old generation of farmers. The discussion takes place not only among business people who run a family business, but also those who are new to coconut business. This is based on the interview data as follows:

“I interact a lot and share knowledge with my son, (HH, farmer 20), regarding cutting, a coconut breeding technique, to accelerate shoot growth. I only used the coconut seed breeding technique inherited from my parents.” MH, old farmer 21

“There is a difference in the knowledge about captive coconut seeds that I learned from my parents (MH, coconut farmer 21) and the knowledge I got from trainings by the government since I became a partner with the Plantation Service. After learning the technique from my parent, the growth rate rose to 90% and even 95% from 70%. The slicing phase of coconut seedlings will accelerate the growth of shoots.” HH, old farmer 20

“In making the VCO, I worked with three groups comprising eight persons each group (old farmers and young farmers). Sumber Alam, our VCO products, are then processed, labelled, and marketed. We have marketed our VCO product to local markets, other provinces, such as Papua and Jakarta, and international markets, such as India and Malaysia.” AA, VCO business CEO, farmer 6

“I am a member of the Coconut Processing Association in Gorontalo Province. Currently, the association has 22 members consisting of 15 members aged under 40 years and 9 members aged over 45 years. This SME produces coconut products, such as VCO, boiled coconut oil, coconut shell charcoal, white copra, and soap. We communicate through WhatsApp groups and regular meetings once a week, exchanging information, especially about the market price of processed coconut, buyers, as well as training and exhibitions of coconut processing.” WK, VCO SME member, farmer 16

The aforementioned discussion explains the interaction between old farmers and young farmers in exchanging information of coconut processing in a community. Such activities help them produce quality coconut products with a high economic value. Advantages of interaction and knowledge sharing has been deemed impactful to the knowledge co-creation between two different groups in producing quality outputs or products [27]. The interrelation between old farmers and young farmers has been discussed in ref. [28] that reports on the necessity for facilitating the two farmer generations by using methods, tools, and technology, especially in the transfer and sharing of knowledge. One method is creating heterogeneous settings, such as joint interactions and laboratory based, home based, or community based. Establishing partnership between farmers is also needed in improving knowledge for sustainable agricultural development. Authors of ref. [29] provide two actual solutions with an interaction approach that contribute to different values in knowledge value creation: individual farmer–researcher–advisor interaction and interaction with farmer group advisors. The linkage of knowledge transfer in agricultural families has remained central to the agricultural knowledge transfer between generations due to the diversity and intensity of relationships that could establish kinships among farmers [3].

3.3 Barriers and structural factors of old and young farmers, farmer regeneration

Barriers and dynamics between old and young farmers in accessing knowledge are different. When old farmers receive new information on the innovation of coconut processed knowledge, they do not proceed to trials, as they are reluctant to face risks and seek information regarding these innovations through the media and other sources of knowledge. On the other hand, young farmers immediately respond when they receive new information on innovative coconut process by conducting repeated trials and experiments and seeking additional information from several resources, training, technical guidance, and digital media. This is based on the interview data as follows:

“Sharing knowledge and information to old farmers are difficult, they will only listen and observe, not put everything into practice Extension sessions in detail are something they need. Young farmers are quick learners, they do not require extensive training and education, they immediately understand and put everything into practice. They also learn from YouTube.” AA, VCO business leader, farmer 6

“When it comes to the interaction and knowledge sharing with young farmers, their response is faster compared to old farmers. Young farmers will apply the knowledge and information immediately, and ask me if there are something they do not understand. This is something I cannot see when sharing with old farmers.” MA, leader of burnt copra SME, farmer 31

“My first experience producing VCO from young coconuts was a failure because the processed product didn’t turn into VCO. I tried to repeat the second trial, using half-dried coconuts. It turned out that the processed oil was still thick like coconut oil, different from VCO. I tried again the third stage with dry coconut by filtering it for seven times using special cotton, filter cloth. The results were good. I could maintain the results and quality after trying and experimenting for almost six months. I learned success is not an instant process, it takes time and patience.” AA, Head of VCO Processing, farmer 6

“Before producing VCO, I did a lot of experiments in making cooking coconut oil; I read a lot of information and browsed from online media (YouTube). One example of my experiment is the addition of papaya leaves as an anti-oxidant, adding more values for my coconut oil. I also added lemon ash to speed up the smoking for the separation of oil and water. In addition, I tried mixing processed coconut with turmeric to have a yellowish color, considering a market segment that favor this type of cooking coconut oil.” WK, UKM VCO and traditional cooking oil, farmer 16

The interview data above show that the barriers and dynamics of access to knowledge between old farmers and young farmers occur due to several differences. Some of these include responses in accessing and responding to information and knowledge innovation, media access to knowledge sources, and motivation to conduct repeated experiments and trials. Failure to process coconuts does not dampen the enthusiasm of young farmers to innovate for the success of their farming practices. This notion corresponds to the result seen in a study by Milone and Ventura [2] that the success of young farmers, as entrepreneurs is due to their creativity, innovation, and ability to collaborate in establishing networks with stakeholders outside the agricultural sector and respond to demands and expectations of agriculture and food sectors. The motivation and enthusiasm of young farmers to carry out continuous experiments are in line with the findings seen in a study by Ingram [30], reporting that the knowledge of the English farmer correlates with years of trial and error.

Central to the knowledge adoption in old farmer and young farmers are structural factors: access to land, capital, technology, human resource skills, influential people, or institutions. This is based on the interview data as follows:.

“I don’t have coconut plantation as the land still belongs to my parents. Thus, I buy coconuts from farmers since cultivating coconut takes time. In terms of financial capital, I collaborate with some friends, signing MOU where the risks are distributed equally.” MA, UMK Coconut Copra, farmer 31

“I learn from more than one knowledge resource since I am aware that success is not about my achievement. It requires others’ support since relying on knowledge for my personal gain is insufficient. I studied knowledge and technology of agriculture and food. I also took part in training and technical guidance at the Ministry of Industry and Trade. I also learned from UNG and UGM lecturers.” AA, Head of VCO processing, farmer 6

“My business was hampered by problems with the processing machine. Due to limited financial condition, my parents lend me some money. I borrowed machineries from other people. I tried to make cooking coconut oil only because my money was only suffice for this business. I stopped my business and focused on copra because the process is not complicated.” MA, Copra business, farmer 31

“We established this coconut business as a marketing network for processed products by SME members to support each other. If there are consumers seeking for our products, we communicated it with SMEs. In terms of access to capital, my fellow women farmers received credit support from the bank. There were also people who wanted to invest in their shares me and my fellow farmers have not responded to the decision.” SY, Chair of the women farmers of refined coconut oil processing, farmer 32

Structural factors of access to knowledge between generations between old and young farmers have different farming orientations. For old farmers, aspects of land access focus on coconut intensification and rejuvenation. Meanwhile, young farmers prefer market-oriented product diversification and processed products with the support of online digital media. Such differing perspectives are underpinned by the fact that plantation areas are not the priority for young farmers. This farmer group does not own land and they claim that growing coconuts from scratch will take a long time. Authors of ref. [8] systematically describe the differences in perceptions of old and young farmers regarding access to land. For old farmers access to managing land for farming is the main thing, while young farmers prioritize access to information needs through digital media. Young farmers claim that land is something inherited from their parents, and it takes time to grow coconut plantation from the beginning. In terms of access to capital, skills, and technology, old farmers are more likely to take risks in accessing capital. They are less interested in taking initiative to improve skills and technological innovation. On the contrary, young farmers, despite limited capital access, focus on improving skills and business networks through technical training by government and private institutions and universities. According to Rajak [31], agriculture stakeholders should utilize technology in increasing production and individual capabilities. Modern agriculture development requires biotechnology, advanced irrigation systems, nanotechnology, the use of organic fertilizers, intensive tillage, monoculture, organic pest controls, and modification with enatic plants to boost productivity and profitability as a way of maintaining farmers’ livelihoods. Authors of ref. [2] found that the above conditions are relevant to the situation experienced by young farmers in Europe, who have limited capital and access to formal credit. Therefore, young farmers rely more on their labor, skills and knowledge, family support, and their social networks. The difference in orientation between old farmers and young farmers is due to the tendency of old farmers in participating in government programs for coconut rejuvenation. Another factor is the limited land for planting coconuts since most areas have been allocated for maize farming.

Differences in action orientation and variation in knowledge co-creation involving young and old farmers in coconut farming practices are one of the factors to preserve local coconut businesses in Gorontalo, preventing them from extinction due to the widespread growth of businesses of hybrid coconut, palm oil, and modern coconut oil in Indonesia. Many old farmers in Gorontalo still maintain their coconut plantation areas through replanting for long-term goals and a source of income. In contrast, young farmers maintain the existence of coconut farming by integrating seasonal crops, such as maize, peanuts, bananas, and chilies, into their coconut plantations. This intercropping system aims to earn additional income.

The above finding is in line with the result of ref. [32] confirming that the sustainability of coconut plantations with an intercropping system positively impacts land maintenance. Furthermore, fertilization on intercrops increases coconut nutrition and nitrogen in the soil resulting in easier harvesting. In addition, despite the differences in the orientation between the two generations in coconut farming, knowledge co-creation promotes sustainability of livelihood. This is because the diversity of knowledge co-creation encourages continuous interaction and distribution of knowledge between generations. This is in accordance with the argument by Ngulube and Stilwell [33] that in achieving a sustainable agriculture, communities must serve as the creator, distributor, and medium of knowledge sharing process.

Regeneration of farmers in the sustainability of coconut farming tends to be supported by two sources of innovation. The first source refers to innovation that comes from knowledge co-creation of the old farmers and the young farmers with local actors who interact with them. And the second source refers to external innovation. Scientific knowledge-based research has long been conducted for coconut modernization. Kallapur et al. [34], for instance, have developed a technique to identify variations of coconut aroma. Authors of ref. [35] have formulated indicators of sustainability assessment for coconut intensification. Authors of ref. [36] have examined the impact of extreme weather on coconut productivity which correlates with the result seen in ref. [37]. Their study finds that the impact of extreme weather corresponds to strategic plans to increase agricultural yields on commodities that depend on rainfall due to changes in rain and temperature. It is, therefore, necessary to formulate an adaptive strategy for sustainable crop production and a policy of agricultural crop production methods. Another solution has been proposed by Wayangkau et al. [38] by the application of Internet of Things in precision farming to increase production with an Arduino microcontroller-based automatic monitoring system. It is used to measure soil moisture and temperature as an effort of anticipating the impact of weather, temperature, and humidity for maintaining crop quality. Another solution was proposed by Handoyo et al. [39]. Their study has promoted coconut klappertaart as an ethnic food with good market prospects. This means that scientific knowledge-based research findings can enrich knowledge co-creation among coconut farmers to maintain the continuity of coconut farming. All of the studies mentioned above will further support the peasantry model developed by van der Ploeg [1] regarding the emergence of the new peasant generation. Based on the description above, the grounded theory scheme produced in this study is interrelated: farmer regeneration as a causal condition, where knowledge co-creation serves as an interaction and coconut farming sustainability as a consequence.

4 Discussion

This study finds significant differences in the orientation between old farmers and young farmers and its correlation to sharing knowledge and information in knowledge co-creation. On that ground, the present work recommends a policy to encourage the maintenance and development of coconut and cooking oil, which appears to be the income source for local people. The policy is a complement to the oil palm expansion and modern coconut oil factories as a profit source for financiers. Enhancing associations of coconut commodities are essential through the involvement of old farmers and young farmers. It should consider the types of coconut processing and partnership or network. For technical recommendation, technical guidance is essential in knowledge co-creation between young farmers and old farmers. This can be done by improving skills and establishing partnerships with institutions, including government and private institutions and universities.

5 Conclusion

Old farmers focused on the revitalization of coconut trees for long-term purposes. The knowledge co-creation process among this farmer group (with other stakeholders) emphasized the copra and cooking oil production; both products were businesses passed down from generation to generation. Young farmers, however, put their concern on coconut tree integration with annual plants (e.g., maize, peanut, and chili) for short-term purposes. Their collaboration with stakeholders focused on VCO and innovative products resulted from the adaptation of foreign technology. In conclusion, coconut business sustainability is the byproduct of knowledge co-creation between old farmers and young farmers. The condition mentioned previously impacts the sustainability of coconut oil business. In other words, the barriers and dynamics of access to knowledge between old farmers and young farmers occur due to several differences. Some of these include responses in accessing and responding to information and knowledge innovation, media access to knowledge sources, and motivation to conduct repeated experiments and trials. Failure to process coconuts does not dampen the enthusiasm of young farmers to innovate for the success of their farming practices. The dynamics and structural factors of young farmers identified in this study also contribute to the continuity of intergenerational knowledge co-creation for a sustainable coconut farming.

Further studies may look at the contribution of multiple actors to knowledge co-creation between farmer generations through interactions with other stakeholders, such as government research institutions, industry, NGOs, higher education research institutions, and journalists. This interaction may enable the acceleration and innovation between old farmers and young farmers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia for the financial support through the BPPDN Doctorate Program of 2019.

-

Funding information: The study was financed with sources of Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia as a part of the BPPDN Doctorate Program of 2019.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Questionnaire

A. Socio-economic characteristics of the informants

| Age: …………………………………………………………………………………………… |

| Formal Education: ……………………………………………………………………… |

| Non-formal Education: ………………………………………………………………… |

| Farming Experience (year): …………………………………………………………… |

| Income (hectare/growing season): ………………………………………………… |

| Land Area (hectare): ……………………………………………………………………… |

| Land Ownership: Owner/Farmer |

Main Knowledge Sources:

|

Orientation of old farmers and young farmers

What are your approaches in the cultivation, processing, and marketing of coconut farming?

What are the sources of knowledge in coconut cultivation, processing, and marketing of coconut farming?

Is there any use of technology in the cultivation, processing, and marketing of coconut farming? Mention the technology instruments?

Are there tools, ways, and methods of knowledge in cultivating, processing, and marketing coconut farming?

What is the motivation of farmers in adopting the use of cultivation technology, processing, and marketing of coconut farming?

What are the changes in knowledge and technology in the aspects of cultivation, processing, and marketing?

Have farmers received training on new technologies? Which training and what institution?

Is there a network or connection with other institutions for technology innovation?

Have you ever consulted on technology services and agricultural innovation when you have problems in coconut farming?

Is there interaction/communication in farming within the family?

In your family, who is the one frequently invited to communicate to share agricultural knowledge and technology? What types of communication?

B. Knowledge co-creation between old farmers and young farmers

What are knowledge and technology passed on to peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers?

What are methods and means of technology passed on to peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers?

What are methods and means of technology passed on to peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers?

What are the changes in the knowledge of peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers after the dissemination of technology support?

Do peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers share the knowledge and means of technology?

How do the peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers respond to the knowledge and means of technology?

Do the knowledge and means of technology impact the agricultural activity? Explain it.

Do the peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers immediately apply the knowledge and means of technology?

What are challenges peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers in applying knowledge and means of technology?

C. Barriers, access dynamics, and structural factors

How do peer farmers, old farmers, and younger farmers respond to information and new technology?

Have you ever failed in making processed coconut products? How do you cope with the failures?

What are the structural factors constraining access to land, technology, capital? How do you cope with those problems?

Appendix 2. Characteristics of the respondents

| No./farmer’s initial | Socio-economic characteristics | Interview duration (min) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer generation category | Land area (hectare) | Educational background | Work experience (year active) | Category of activity | |||||

| Young 20–45 years | Old 46–65 years | Commodity | Processing | Marketing purposes | |||||

| 1. SA | 42 | — | 3 | Bachelor | 20 | Coconut | Fresh fruit | Collectors | 75 |

| 2. AS | — | 50 | 3 | Junior high school | 30 | Coconut | Copra | Factory | 35 |

| 3. RM | — | 60 | 1 | Elementary school | Coconut | Traditional VCO producer | Market, neighbor | 30 | |

| 4. T | 43 | — | 17 | Master’s degree | 5 | Coconut | VCO, fresh fruit | Factory | 65 |

| 5. SZ | 57 | 4 | Elementary school | 27 | Coconut | Fresh fruit | Collector | 30 | |

| 6. AA | 44 | — | 3 | Bachelor | 18 | Coconut | VCO | Pharmacy, export | 40 |

| 7. AH | 50 | 10 | Junior high school | 15 | Coconut | Copra producer | Copra factory | 30 | |

| 8. YH | — | 59 | 2 | Junior high school | 29 | Coconut | Copra producer, fresh fruit | Copra factory | 30 |

| 9. KN | 45 | — | 1 | New high school | 10 | Coconut | VCO and coconut cake | Market, supermarket | 40 |

| 10.YK | — | 51 | 1.5 | Senior high school | 36 | Coconut | Copra, fresh fruit | Factory | 35 |

| 11. SM | — | 69 | 1 | Elementary school | 38 | Coconut | Copra, fresh fruit | Collector | 30 |

| 12. AB | — | 60 | 3 | Senior high school | 30 | Coconut | Copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 35 |

| 13. MM | — | 67 | 5 | Junior high school | 20 | Coconut | Copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 30 |

| 14. SU | 37 | — | 1 | Senior high school | 5 | Coconut | Coconut bonsai crafter | Exhibition | 40 |

| 15. TN | 47 | 1 | Senior high school | 20 | Coconut | Dodol (traditional snack) producer | Market, airport, export | 35 | |

| 16. WK | 25 | — | 3 | Bachelor | 4 | Coconut | Traditional cooking oil, VCO, white copra | Export, exhibition | 75 |

| 17. AL | 20 | 1 | Senior high school | 2 | Coconut | Dodol (traditional snack) producer | Export | 40 | |

| 18. OP | — | 51 | 3 | Senior high school | 19 | Coconut | Copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 35 |

| 19. LA | — | 48 | 2 | Senior high school | 15 | Coconut | Copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 35 |

| 20. HH | 29 | — | 3 | Bachelor | 8 | Coconut | Coconut seedlings | Farmer | 40 |

| 21. MH | — | 55 | 5 | Senior high school | 20 | Coconut | Copra, coconut seedlings, fresh fruit | Factory, collector, farmer | 30 |

| 22. SM | 44 | — | 2 | Bachelor | 5 | Coconut, lowland rice | Fresh fruit, VCO | Market, collector | 35 |

| 23. KH | 44 | — | 30 | Senior high school | 10 | Coconut, maize, chili, peanut | Copra, white copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 30 |

| 24. AH | 43 | — | 2 | Junior high school | 7 | Coconut, maize, peanut | Copra, fresh fruit | Collector | 35 |

| 25. AB | — | 70 | 2 | Elementary school | 40 | Coconut, maize | Copra, fresh fruit | Collector | 30 |

| 26. YP | — | 60 | 2 | Elementary school | 30 | Coconut, maize | Copra, fresh fruit | Collector | 30 |

| 27. MD | 29 | — | 1 | Bachelor | 5 | Coconut, maize | White copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 45 |

| 28. HG | — | 68 | 20 | Junior high school | 44 | Coconut, maize | Copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 30 |

| 29. RH | — | 40 | 4 | Senior high school | 5 | Coconut | Fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 40 |

| 30. RA | 31 | — | 1 | Bachelor | 6 | Coconut, maize | White copra, fresh fruit | Factory, collector | 45 |

Appendix 3. Data process results using the Atlas.ti

3.1 Action orientation of old and young farmers

3.2 Knowledge co creation of old and young farmers

3.3 Obstacles, dynamics and other structural access to knowledge

References

[1] van der Ploeg JD. The new peasantries rural development in times of globalization. 2nd edn. New York: Routledge; 2018.10.4324/9781315114712Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Milone P, Ventura F. New generation farmers: rediscovering the peasantry. J Rural Stud. 2019;65(May):43–52.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.009Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Wójcik M, Jeziorska-Biel P, Czapiewski K. Between words: a generational ussion about farming knowledge sources. J Rural Stud. 2019;67(February):130–41. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.02.024.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] van Ewijk E, Ros-Tonen MAF. The fruits of knowledge co-creation in agriculture and food-related multi-stakeholder platforms in sub-Saharan Africa – a systematic literature review. Agricultural systems. 2021;186:102949.10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102949Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Akpo E, Crane TA, Vissoh PV, Tossou RC. Co-production of knowledge in multi-stakeholder processes: analyzing joint experimentation as social learning. J Agric Educ Ext. 2015;21(4):369–88.10.1080/1389224X.2014.939201Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Struik PC, Klerkx L, van Huis A, Röling NG. Institutional change towards sustainable agriculture in West Africa. Int J Agric Sustain. 2014;12(3):203–13.10.1080/14735903.2014.909641Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Laforge JML, McLachlan SM. Learning communities and new farmer knowledge in Canada. Geoforum. 2018;96(December 2017):256–67. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.07.022.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Junais I, Samsuar, Daniel, Ali HM, Yusran, Syarif A, et al. Young farmers and parents’ perception for the future of agriculture: socio-spatial integration of coffee farmers in Jeneponto Regency. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2020;473(1).10.1088/1755-1315/473/1/012017Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Statistik BPPG. Gorontalo Dalam Angka 2020. 2020;3(2):54–67, http://repositorio.unan.edu.ni/2986/1/5624.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] BPS Gorontalo Province. Gorontalo Province in Figures 2020. 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] NSLIC. Kajian Ekonomi Komoditas Kelapa Provinsi Gorontalo by. 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Regeer BJ, Bunders JFG. Knowledge co-creation: interaction between science and society. The Netherlands: RMNO; 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Herrmann-Pillath C. The art of co-creation: an intervention in the philosophy of ecological economics. Ecol Econ. 2020;169:106526.10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106526Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Wyborn C. Co-productive governance: a relational framework for adaptive governance. Glob Environ Change. 2015;30:56–67.10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.009Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Norström AV, Cvitanovic C, Löf MF, West S, Wyborn C, Balvanera P, et al. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat Sustain. 2020;3(3):182–90.10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Turner JA, Horita A, Fielke S, Klerkx L, Blackett P, Bewsell D, et al. Revealing power dynamics and staging conflicts in agricultural system transitions: case studies of innovation platforms in New Zealand. J Rural Stud. 2020;76(February):152–62. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.022.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Douthwaite B, Keatinge JDH, Park JR. Why promising technologies fail: the neglected role of user innovation during adoption. Res Policy. 2001;30(5):819–36.10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00124-4Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Gielen PM, Hoeve A, Nieuwenhuis LFM. Learning entrepreneurs: learning and innovation in small companies. Eur Educ Res J. 2003;2(1):90–106.10.2304/eerj.2003.2.1.13Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Van Rijn F, Bulte E, Adekunle A. Social capital and agricultural innovation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agric Syst. 2012;108:112–22.10.1016/j.agsy.2011.12.003Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13(1):3–21.10.1007/BF00988593Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Bertolozzi-Caredio D, Bardaji I, Coopmans I, Soriano B, Garrido A. Key steps and dynamics of family farm succession in marginal extensive livestock farming. J Rural Stud. 2020;76(March):131–41. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.030.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Salman D, Kasim K, Ahmad A, Sirimorok N. Combination of bonding, bridging and linking social capital in a livelihood system: nomadic duck herders amid the covid-19 pandemic in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. For Soc. 2021;5(1):136–58.10.24259/fs.v5i1.11813Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Kasurinen J. Software organizations and test process development [Internet]. Adv Comput. 2012;85:1–63. Elsevier Inc. 10.1016/B978-0-12-396526-4.00001-1.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Cofré-Bravo G, Klerkx L, Engler A. Combinations of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital for farm innovation: how farmers configure different support networks. J Rural Stud. 2019 Jul 1;69:53–64.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.04.004Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Ö, Fawole B, Titiloye MA, Olutayo AO, et al. By slapping their laps, the patient will know that you truly care for her”: a qualitative study on social norms and acceptability of the mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria. SSM – Popul Health. 2016;2:640–55. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.07.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Cochetel C, Phiboon K, Faysse N. Young farmers in Thailand: small numbers, but diversified projects. Paris, France: AFD-MEAE; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Zhang Y, Zhang M, Luo N, Wang Y, Niu T. Understanding the formation mechanism of high-quality knowledge in social question and answer communities: a knowledge co-creation perspective. Int J Inf Manage. 2019;48(July 2018):72–84. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.01.022.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Anderson S, Fast J, Keating N, Eales J, Chivers S, Barnet D. Translating knowledge: promoting health through intergenerational community arts programming. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(1):15–25.10.1177/1524839915625037Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Triste L, Debruyne L, Vandenabeele J, Marchand F, Lauwers L. Communities of practice for knowledge co-creation on sustainable dairy farming: features for value creation for farmers. Sustain Sci. 2018;13(5):1427–42.10.1007/s11625-018-0554-5Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Ingram J. Technical and social dimensions of farmer learning: an analysis of the emergence of reduced tillage systems in England. J Sustain Agric. 2010;34(2):183–201.10.1080/10440040903482589Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Rajak ARA. Emerging technological methods for effective farming by cloud computing and IoT. Emerg Sci J. 2022;6(5):1017–31.10.28991/ESJ-2022-06-05-07Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Pabuayon IM, Medina SM, Medina CM, Manohar EC, Villegas JIP. Economic and environmental concerns in philippine upland coconut farms: an analysis of policy, farming systems and socio-economic issues; 2008. p. 10.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Ngulube P, Lwoga E. Knowledge management models and their utility to the effective management and integration of indigenous knowledge with other knowledge systems. IAJIKS. 2007;6(2):117–31, https://www.ajol.info/index.php/indilinga/issue/view/3544.10.4314/indilinga.v6i2.26421Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Kallapur S, Hegde M, Sanil AD, Pai R, Sneha NS. Identification of aromatic coconuts using image processing and machine learning techniques. Glob Transit Proc. 2021;2(2):441–7.10.1016/j.gltp.2021.08.037Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Rodrigues GS, Martins CR, de Barros I. Sustainability assessment of ecological intensification practices in coconut production. Agric Syst. 2018;165(June 2018):71–84. 10.1016/j.agsy.2018.06.001.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Pathmeswaran C, Lokupitiya E, Waidyarathne KP, Lokupitiya RS. Impact of extreme weather events on coconut productivity in three climatic zones of Sri Lanka. Eur J Agron. 2018;96(March):47–53. 10.1016/j.eja.2018.03.001.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Jabal ZK, Khayyun TS, Alwan IA. Impact of climate change on crops productivity using MODIS-NDVI time series. Civ Eng J. 2022;8(6):1136–56.10.28991/CEJ-2022-08-06-04Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Wayangkau IH, Mekiuw Y, Rachmat R, Suwarjono S, Hariyanto H. Utilization of IoT for soil moisture and temperature monitoring system for onion growth. Emerg Sci J. 2020;4(Special Issue):102–15.10.28991/esj-2021-SP1-07Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Handoyo CC, Claudia G, Firdayanti SA. Klappertaart: an Indonesian e Dutch influenced traditional food. J Ethnic Foods. 2017;5(December):1–6. 10.1016/j.jef.2017.12.002.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry