Abstract

The amino acid arginine has been identified as a promising building block for the construction of functionalized nanosystems due to its unique chemical properties. Arginine-based peptides and polymers have been widely used in targeted drug delivery, gene therapy, and cancer therapy, as they can target specific cells and organs, thus increasing the efficiency and specificity of drug delivery. In addition, arginine-based nanosystems have shown potential in other applications such as imaging, regenerative medicine, environmental remediation, biosensing, gene editing, water treatment, and food safety. The synthetic methods for arginine-based nanosystems have been improved over the years, and new characterization techniques have been developed to properly evaluate the performance and properties of arginine-based nanosystems. However, several challenges need to be overcome to fully realize the potential of arginine-based nanosystems. These include scale-up and industrial production, biocompatibility and toxicity, and in vivo evaluation. In addition, the safety and toxicity of arginine-based nanosystems need to be carefully evaluated. This review covers recent progress in the field of arginine-based nanosystems, highlighting the advantages and limitations of arginine-based nanosystems as well as the current challenges and future perspectives in the field. It is an important source of information for researchers, scientists, and engineers working in the field of functionalized nanosystems, and it highlights the potential of arginine-based nanosystems in various applications and the challenges that need to be overcome to fully realize their potential.

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology is an emerging field that has the potential to revolutionize various industries, including medicine, agriculture, and environmental remediation. Functionalized nanosystems, such as nanoparticles, have attracted significant attention due to their ability to target specific cells and organs, thus increasing the efficiency and specificity of drug delivery [1]. Among the various building blocks used for the construction of functionalized nanosystems, the amino acid arginine has been identified as a promising one due to its unique chemical properties [2]. Arginine-based peptides and polymers have been widely used in targeted drug delivery, gene therapy, and cancer therapy [3,4,5]. In addition, arginine-based nanosystems have shown potential in other applications such as imaging, regenerative medicine, environmental remediation, biosensing, gene editing, water treatment, food safety, and many more [4,6–9].

However, several challenges need to be overcome to fully realize the potential of arginine-based nanosystems. These include the scale-up and industrial production of arginine-based nanosystems, the development of effective synthetic methods, the characterization of arginine-based nanosystems, and the in vitro and in vivo evaluation of their performance [6,9]. In addition, the safety and toxicity of arginine-based nanosystems need to be carefully evaluated [9].

Arginine-based nanosystems have several advantages over other types of functionalized nanosystems. For example, arginine is a natural amino acid that is biocompatible and biodegradable, making it a suitable building block for the construction of functionalized nanosystems [4,10]. In addition, arginine has a high charge density and a unique chemical structure that allows for the formation of stable peptide and polymer structures [11]. These properties have been exploited for the development of arginine-based nanosystems for various applications such as targeted drug delivery [6], gene therapy [3], cancer therapy [4], imaging [12], regenerative medicine [13], environmental remediation [14], biosensing [15], gene editing [3], water treatment [16], and food safety [17].

The development of technologies for multifunctional inactive ingredients, extensive use of innovative drug delivery systems, and rising demand for orphan pharmaceuticals are some of the factors contributing to the increased market growth for excipients in the businesses that produce medicines. According to a Markets & Markets analysis, the pharmaceutical excipients market generated $10.0 billion in sales in 2023 and is expected to reach $13.9 billion by 2025 [18]. According to Technavio’s market research, the global consumption of pharmaceutical excipients is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of more than 6% by 2021. Of these, organic chemicals manufacturing accounts for 80% of the market and is expected to increase at a CAGR of 7.8% through 2025 due to the use of oleochemicals [19]. Due to higher patient compliance and localized skin effects that are safer and faster compared to systemic drug delivery, the market for externally applied dosage forms comprising inactive chemicals is expected to develop at a pace of 7.4% annually during the projected period [20].

In recent years, the synthetic methods for arginine-based nanosystems have been improved, and new characterization techniques have been developed to properly evaluate the performance and properties of arginine-based nanosystems [9]. However, several challenges must be overcome to fully realize the potential of arginine-based nanosystems. These include the scale-up and industrial production of arginine-based nanosystems [21,22], the development of effective synthetic methods [23], the characterization of arginine-based nanosystems [24], and the in vitro and in vivo evaluation of their performance [11,25–28]. In addition, the safety and toxicity of arginine-based nanosystems need to be carefully evaluated [3,20].

This review will provide an overview of the different applications of arginine-based nanosystems, the synthetic methods used to prepare them, the characterization techniques used to evaluate their performance, and the in vitro and in vivo evaluation methods used. It will also cover the challenges and limitations of arginine-based nanosystems, as well as the current research trends and future perspectives in the field. In addition, the article will cover the toxicity and safety of arginine-based nanosystems and compare the performance of arginine-based nanosystems to other types of nanosystems in different applications.

2 Arginine as a building block for functionalized nanosystems

There are different types of arginine-based peptides and polymers that have been used in the construction of functionalized nanosystems. Peptides containing arginine, such as arginine-rich peptides, have been used to create functionalized nanoparticles that can interact with cells and tissues. Also, arginine-based polymers, such as polyarginine, have also been used to develop functionalized nanoparticles that can be used for drug delivery [4].

Recent progress in the field of arginine-based functionalized nanosystems has seen the development of nanoparticles for various biomedical applications, as illustrated by Figure 1. Arginine-based nanoparticles have been used for targeted drug delivery to cancer cells [29]. In addition, arginine-based nanoparticles have also been used as a delivery system for siRNA to silence specific genes in cancer cells [3].

Illustration of the diverse biomedical applications of arginine-based nanocarriers.

The use of arginine in the construction of functionalized nanosystems has some advantages. For example, arginine-based nanoparticles have been found to have high stability in biological environments [30]. In addition, arginine-based nanoparticles have been found to have a high ability to interact with cells and tissues, making them suitable for various biomedical applications [31]. However, there are also some limitations to using arginine in the construction of functionalized nanosystems. For example, arginine-based nanoparticles have been found to have a relatively low drug-loading capacity. In addition, arginine-based nanoparticles have been found to have a relatively low tumour targeting efficiency [32].

The use of arginine in the construction of functionalized nanosystems has a lot of potential for future developments. There is potential to use arginine-based nanoparticles for targeted delivery of drugs to specific organs or tissues. Moreover, there is potential to use arginine-based nanoparticles in combination with other functionalized nanosystems, such as liposomes, to improve their performance [33].

3 The function of arginine in the delivery of topical drugs

Arginine is a type of amino acid that is conditionally nonessential. Three hydrocarbon methyl groups are present, and a positively charged guanidium group surrounds them, giving it a high basicity and the highest isoelectric point of all amino acids (10.75). Arginine has a relatively low partition coefficient (approximately −4.08 ± 0.7) and low permeability. In animal cells, arginine serves as nitric oxide precursor and plays a key role in various critical physiological processes, such as cell proliferation and angiogenesis [34,35]. Nitric oxide and l-citrulline are produced from arginine with the aid of the enzyme nitric oxide synthase. Nitric oxide from endothelial cells causes the smooth muscles’ guanylyl cyclase enzyme to become active, which raises the level of cyclic guanylate monophosphate, which causes the muscles to relax [36].

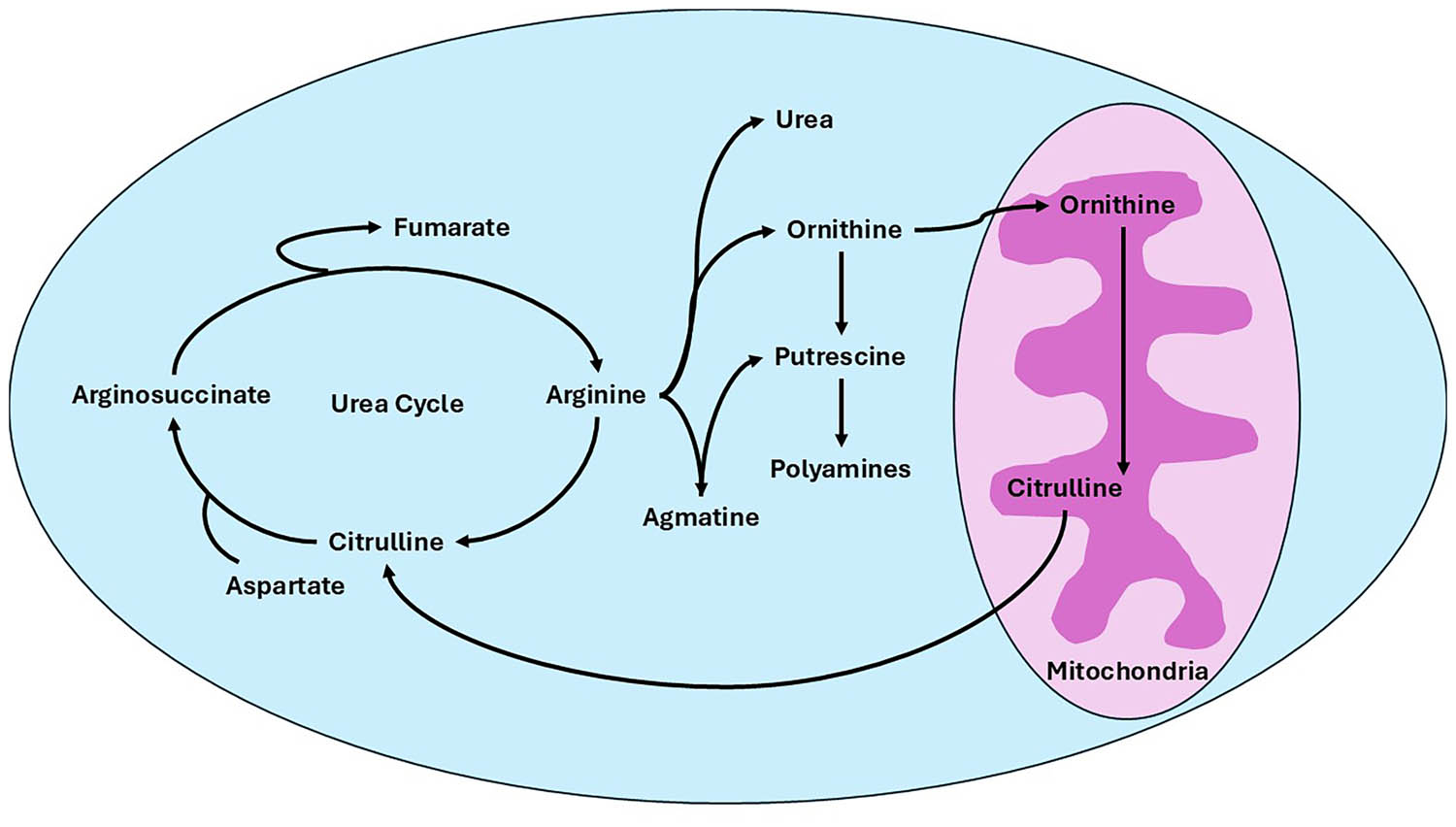

Nitric oxide plays a crucial function in things pertaining to hair growth. Vasodilatation and the potassium channels opening were also involved. Vasodilation increases blood flow to the area, which stimulates the development of hair. In addition, the urea cycle utilized by arginase-I enzyme in the liver converted into l-arginine into ornithine. Ornithine transforms into l-proline and then pyrroline-5-carboxylate. This is essential for the biosynthesis of several structural proteins, including collagen. Due to collagen metabolism and cell proliferation via the polyamine pathway, arginine supplementation in humans and animals is crucial for the healing of wounds [37,38]. According to the previously discussed methods, the arginine molecule has numerous uses as a potent medicinal component for both exterior and internal use. The overall metabolic process pertinent to the efficacy of the arginine molecule is depicted in Figure 2.

Representation of arginine metabolism within the urea cycle and polyamine biosynthesis pathway. Arginine has central metabolic roles as a precursor. Arginine is converted to urea and ornithine within the urea cycle, whereby either re-enters the cycle or serves as a source of substrate for the biosynthesis of polyamines through putrescine. In addition, arginine serves as a precursor for agmatine production and for polyamine synthesis. This diagram represents the mitochondrial and cytosolic compartments at which these processes take place, with arginine being an indispensable player in both nitrogen metabolism and cellular homeostasis.

Since amino acids are organic, renewable, and molecules biodegradable, any surfactants or other substances created from them are also safe for both humans and the environment. The green compounds are superior to conventional ones due to these advantages. Vegetable oils and amino acids, which are renewable resources and nontoxic, are used to create these eco-friendly chemicals.

Early in the twentieth century, experiments with the synthesis of arginine-based surfactants were conducted. In the past, these sorts of surfactants were employed in cosmeceuticals as preservatives; however, reports on the potential usage as potent inhibitors of pathogenic bacteria and viruses as well as effective surfactants or emulsifiers in pharmaceutical formulation began to circulate.

Takano et al. developed and patented the first arginine-based derivatives in the early nineteenth century. They demonstrated the N-acyl-arginine formation by C8-22 acyl condensation through arginine with the help of a base, following the prepared mid-product esterification with C12-22 alcohol in the acid existence [39]. However, these compounds could be used in shampoo, cosmetics, and external dose forms for medications. The following work included further patents and research activities that directed the production of arginine-derived surfactants. These publications discuss the use of cleaners, antimicrobials, conditioners, emulsifiers, and so on [40].

4 The formulation and characteristics of an arginine-based compound

4.1 Complexes derived from amino acids

Amphiphilic in nature, amino acids are a great option for researchers since the greener moiety can be used to create a variety of compounds, adhering to the 12 principles of green chemistry [41]. The initial source of amino acid-based surfactants is plant and animal food. The majority of 20 amino acids are recognized as proteogenic components, which support the production of proteins vital to all living things [42]. Among them, arginine, which may be delivered through both systemic and localized drug delivery systems, is extremely important for the biological operation of the body. Surfactants, co-excipients, diluents, and additives are examples of green excipients used in the pharmaceutical industry [20].

Surfactants have a wide range of uses, including in emulsifiers, oil industries, medications, laundry detergents, and other products. Surfactants are the excipients in pharmaceutical formulations that require the most attention, employing in large quantities and have a history of having negative impacts on the aquatic environment [43,44]. To lessen the negative effects and create synthetic excipients that are both effective and environmentally friendly, biosurfactants – which are safe for human use, biodegradable, and have great efficacy – come into play. Biosurfactants are generally understood to be molecular substances that are generated from microorganisms like bacteria, molds, yeast, and so on. In addition to synthetic molecules made from naturally occurring amphiphilic biochemicals such phospholipids, amino acids, and glucosides, green surfactants can also be generated from bacteria [45].

According to the literature, amino acid-based surfactants are categorized by their place of manufacture, how an aliphatic chain is substituted, how many hydrophobic tails there are, and what kind of polar head group they include [46,47].

4.2 Fundamental pathway for creating derivatives based on amino acids

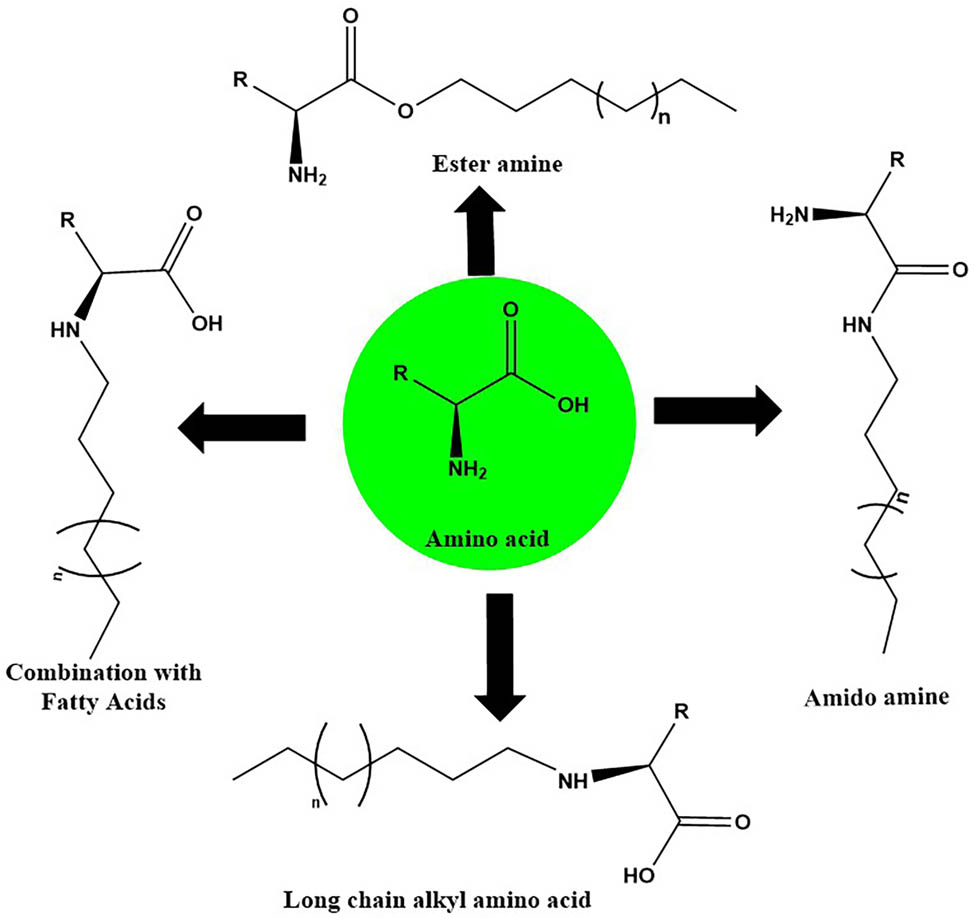

The location of the carboxylic group, the amine component, or the side chain of an amino acid is where the lipophilic group can be attached. Four synthetic approaches are possible for scientists to use, as shown in Figure 2, based on these options [48,49]. Synthesis route 1 showed that the esterification process produced an amphiphilic ester amine as the final product. To execute esterification, the amino acid is often mixed with fatty acid alcohol in an acidic catalyst and the dehydrating molecule presence is then refluxed for the required time amount. Amidoamine is produced via route 2 with more surface activity. Alkyl amine reacts chemically with an activated amino acid for the formation of an amide bond, which leads to the creation of this product. In route 3, the amine moiety of the amino acid and fatty acid are simply reacted to create an amino acid surfactant [20].

Synthetic route 4 produces long-chain alkyl amino acids as a byproduct, combining an alkyl-halogen with an amino acid from the amine group. Route 5 involves the moiety fusion of an amino acid’s side chain with a fatty acid alcohol. For instance, aspartic acid’s −COOH group reacted with a long-chain lipophilic alcohol for the formation of anhydride [20] (not represented in Figure 3).

Different routes and procedures for the synthesis of surfactants based on amino acids.

4.2.1 Surfactant synthesis using single-chain amino acids

According to Widmer, the t-butyl-esters were synthesized through the carboxylic acid reaction and 2-methyl-propane in the sulfuric acid presence or by an acid-chloride reaction with t-butyl alcohol [50]. Methyl-N-unprotected ester, a central moiety for chemical synthesis, is used in the manufacture of arginine ester. It is simple to make using Fisher-type esterification, involving esterifying arginine dissolved in methanol containing SOCl2, HCl, or trichloromethyl silane presence [51]. In addition, several strategies, including the Boc group, have been discovered for the nitrogen atom protection in the arginine. N-Boc amino acid is produced through N-Boc benzylamines oxidation, N-Boc amino acids, and N-Boc furfurylamines. Therefore, it is crucial to design a technology that can directly convert N-Boc amino acid toward methyl-N-unprotected amino ester exclusive of first N-Boc group deprotection in addition to the separation of intermediate of free amino acid [52].

4.2.2 Gemini amino acid/peptides surfactant synthesis

Two linear amino acids are linked through polar heads and a spacer to form Gemini surfactants. For the surfactants creation established on amino acids of the Gemini type, various synthesis strategies are known in the literature.

The Gemini surfactant, which is based on amino acids, was initially created in 1996 by Pérez et al. A derivative of N-α-acyl-arginine linear chain with 8, 10, and 12 carbon atoms was used to create a product cation known as (N-α-acyl-l-arginine) α-ω-polymethylene-diamide dihydrochloride salts, or bis (Args). These linear chains have amide covalent connections at the arginine-residue moiety of carboxylic acid with spacer chains of varying lengths of α-ω-diaminoalkane. This procedure used chemical catalysts, chemical protective groups, and organic solvents [53].

Further research was conducted by the introduction of the bis(Args) chemoenzymatic synthesis to replace the need for other compounds [54]. The derivatives of N-α-acyl-l-arginine alkyl-ester served as a main structural component of the finished product in this approach. The quantitative acylation of one amino group on the α, ω-diamino alkane-spacer was carried out using N-α-acyl-arginine carboxylic ester in a solvent-free environment. This process, which involves the melting point of the spacer, is considered the first step in the synthesis of these Gemini surfactants. The free aliphatic amino group and alkyl ester of N-α-acyl arginine of the intermediate product created in first-stage were combined in the second-step with the help of the papain catalyst. The solid-solid system produced the best yield (70%) of all [54]. By means of 1, 3-diamino-2-hydroxy-propane as spacers as well as 1, 3-diamino propane, supplementary analogues of bis (Args) with 8, 10, and 12 carbon atoms were created. The overall yields were between 51 and 65%. The industrial application of these Gemini surfactants led to a reduction in surfactant concentration when compared to conventional surfactants.

The 3, 6, and 9 carbon atom bis (Args) Gemini surfactants were created by Pérez et al. They determined that single-chain surfactants had the best qualities after comparing their surface tension behaviour and solution behaviour with those of surfactants of single-chain arginine [55].

4.2.3 Glycerolipid amino acid surfactant synthesis

The unique surfactants or lipoamino acids class was created based on the amino acid. They are made up of one or two aliphatic chains, glycerol backbones, one amino acid, and ester linkages that hold everything together.

Moran et al. used chemical and chemoenzymatic methods to create the derivatives of mono- and di-acylglyceride from arginine and N-α-acetyl-arginine. The synthesis of esters of mono- and di-acylglyceride–acetyl arginine was acted upon using the enzymatic approach (hydrolase enzyme), by acetyl arginyl glycerol creation as a polar head [56]. Lipase and protease were also discovered to be flexible catalysts for the same process. In addition, the glycerol-free hydroxyl group, acetylating with fatty acids with the help of lipase enzyme, is involved in the second phase. Moran et al. improved the original method for producing glycerolipid-based arginine surfactant by using 1, 3-selective lipases to carry out the mono- as well as di-acetylation of amino acid glyceryl ester. An impulsive intramolecular process of acyl migration is the consequence. Diacetylated product yield is determined by the migration rate of intramolecular acyl involving enzyme esterification of the monoacetylated molecule primary hydroxyl group. Solvents, buffer salts, the effectiveness of enzyme immobilization, and amino acid ester derivatives all have an impact on both processes. At the relevant fatty acid’s melting point and in a solvent-free medium, the ester derivatives are acylated [57].

Several mono- and di-lauroylated-glycerol derivatives of aspartic acid, acetyl-arginine, glutamic acid, and tyrosine have been created using the approach indicated earlier. Pérez et al. used a three-step procedure to chemically synthesise an amino acid based on arginine: (1) Using noron trifluoroetharate as a catalyst, the N-Cbz-l-arginine hydrochloride-COOH moiety is esterified containing the glycerol −OH group to produce the conforming 1-O-(N-Cbz-l-arginyl)-rac-glycerol monochloride (95% of yield). (2) The aforementioned resulting product is acylated for producing 1-acyl-3-O-(N-Cbz-arginyl)-rac-glycerol-HCl and its diacyl derivative. (3) Hydrogenation is used to remove the Z-protecting moiety [58].

It was also possible to create dilaurylated arginine glyceride conjugate using an enzymatic method with papain. It has also been shown to synthesise dilauroylated arginine glyceride conjugate enzymatically using papain. There have also been reports on the synthesis of acetylarginine-derived diacylglycerolipid conjugates and assessments of their physical and chemical characteristics [59–61].

4.2.4 Amphiphile bola-ring synthesis

The bola-amphiilic surfactants are made up of two different amino acids that are linked together with the assistance of a hydrophobic linker. Silva et al. utilized the arginine-capped bola-amphiphiles RFL4FR in their investigation of the self-assembled nature of the molecule when it was placed in water. When this amphiphilic peptide was used as a substrate to modify the hydrophilicity of solid surfaces for cell culture, it became clear that its surface was an ideal environment for the formation of human corneal stromal fibroblasts [62].

Edwards-Gayle et al. investigated the ability of two bola-amphiphilic surfactants based on arginine, RA9R and RA6R, to self-assemble and to be antimicrobially effective. They discovered that because the latter molecule is more hydrophobic than the former, it exhibits stronger self-aggregation properties and fewer antibacterial capabilities [63].

4.2.5 Double-chain arginine-surfactant synthesis

Four novel surfactants of arginine with two alkyl chains of various lengths were created by Pinazo et al. in 2016: N-α-lauroyl arginine decyl amide HCl, N-dodecyl arginine-O-dodecyl amide HCl, N-α-lauroyl arginine-O-myristoyl amide HCl, and N-α-lauroy. The N-α-lauroyl-arginine methyl-ester HCl is dispersed in appropriate fatty-amine up to the level of a fatty-amine melting-point temperature for 3 h, followed by cooling of mixture and crystallized repeatedly with acetonitrile/methanol to get a desired product. More than 90% of the products were discovered to be produced, and no form of activating agent is needed for the reaction [64].

4.3 Properties of surfactants

The significance of various surfactant properties in diverse scientific applications was demonstrated in Table 1. Recent years have seen an increase in the importance of developing and characterizing green or biocompatible substances for use in nanotechnology, drug delivery systems, and nanomedicines [65]. Molecular self-assembly and surface behaviour are two physicochemical characteristics of the compounds that are widely used in a variety of fields.

Outline of key properties of surfactants. Each property is defined to illustrate its significance in surfactant functionality and application in formulation

| Properties of surfactants | Importance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Critical micellar concentration (CMC) | The CMC is the concentration of surfactants during which micelles begin to form. This attribute is crucial since it determines the surfactant’s solubilization, lytic action, and penetration properties in the biological membrane | [66] |

| Kraft temperature and kraft point | Temperature plays a role on the surfactant’s solubility. As temperature rises above a certain degree (the Kraft point), the effect becomes more pronounced. Solubility decreases below the kraft threshold for non-associated surfactants and is most pronounced with anionic surfactants. It is possible to increase the solubility to the kraft point and beyond. In the process of formulating, this idea is implemented when a surfactant is added. Formulation above the kraft point of the surfactant is required for complete solubility | [67] |

| Water solubility | Due to its high-water solubility, the surfactant is both biodegradable and environmentally beneficial. Because of this, a smaller dose is effective against more bacteria | [68] |

| Surface tension | It grows as the hydrophobic chain length of the surfactant grows | [69] |

| Phase behaviour | This is a function of the surfactant concentration and represents a shift in the molecular association structure | [70,71] |

| Aggregation behavior | The aggregation behaviour of surfactants is typically studied using differential light scattering | [72] |

4.3.1 Surfactants derived from single-chain arginine

N-α-acyl arginine alkyl-esters, arginine-O-α-alkyl amides, and arginine-O-α-alkyl esters are three types of single-chain arginine surfactants. The positively charged guanidine group is in the first surfactant, while the positively charged guanidine group is in the second and third categories of surfactants (both on the guanidine group and main amine). Surface activities of single-chain derivatives are equivalent to that of traditional quaternary cationic surfactants. The value of CMC has been discovered to be between 1 and 30 mM. The γCMC was found to be between 30 and 37 mN/m. The hydrophobicity of the molecule affects CMC value. The CMC decreases as hydrophobicity increases [57,73]. I m is the air–water interface’s saturation adsorption value, and A min is the area/molecule determined by the Gibbs adsorption isotherm. While for acyl compounds, A m = 0.67–0.62 nm2; for amides and foresters, A m = 0.92–1.22 nm2 and 0.62–1.14 nm2, respectively. This suggests a tightly packed acyl arginine derivative at air–water interface. The behaviour of self-aggregation of the HCl-salt of N-α-lauryl-arginine methyl-ester was studied by Talmon’s research group. By using cryogenic transmission electron microscopy, they discovered the microstructure present in N-α-lauroyl-arginine methyl-ester (LAM) solutions. Cylindrical and spheroidal micelles appeared depending on the concentration of surfactant, according to the data [74]. Small-angle X-ray scattering and pulsed-gradient spin echo nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements were used by Pérez et al. in 2007 to further investigate the micellization process small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) [75]. For determining the co-efficient of self-diffusion of LAM at 25°C, the first approach was used [76].

By using polarized light microscopy, Solans demonstrated hexagonally (PAM, MAM, CAM, and LAM), cubically (MAM, and LAM, CAM), and lamellarly (PAM and MAM) structured crystals of lyotropic liquid. In multicomponent systems, the single-chain arginine-derived surfactants phase behaviour was found to be as liquid crystals, reverse micelles, and micelles. When there are hydrocarbon components present, these surfactants are crucial to the microemulsion dose form (toluene, squalene, and hexadecane) [73,77]. Kunieda et al. discovered that a formulation of microemulsion consisting of lecithin-LAM/squalene/water remained efficient in cosmetic and medicinal applications [78].

4.3.2 Gemini surfactants as Bis (Arg)

Gemini surfactants called Bis (Args) are generated from arginine. Gemini surfactants included C9(LA), C6(LA), C4(LA), and C3(LA)2. In the excessive salt presence, the bis (Args) surface area with spacer (C4-6) was determined as 0.6 nm2/molecule [79]. It was found that the power of CMC was two to three orders of magnitude lower comparison of LAM. The minimum CMC surface tension was not significantly different from that of the LAM [80]. The micelles generated during the aggregation, which takes place above the CMC, are not typical ones. The traditional micelles formed above the second higher CMC and influence solubilization, the interaction ability with counter ions, and the water presence. Adsorption was observed to be rather slow at concentrations below CMC1 and to accelerate at concentrations between CMC1 and CMC2. The observed data show that the foam stabilisers are more effective than LAM in stabilizing foam, and the foaming capabilities were similar to those of single-chain arginine surfactant [81]. Aggregation number: R mon(T) can be used to calculate it. Gemini surfactants demonstrated high aggregate formation rates (twice the LAM), which led to this conclusion. The spheroidal form of micellar structure at low concentration corresponds to the monomer size theoretical value, which is also a calculated value of LAM. These values were discovered to be different for Gemini surfactants because dimmers, trimers, and tiny aggregates formed at CMC1 as well as CMC2. This is because the micelle structure for Gemini surfactant was determined by SAXS and PGSE-NMR technologies to be thread-like ribbons, fat, or twisted [82].

As the concentration was raised, the Bis (Args) with short spacers developed spheroidal micelles that eventually took on thread- and disk-like shapes. Because of the spacer molecule’s extended shape, these geometries of micelles exist in lower quantities and are more hydrophobic. All of these micelles eventually developed into ribbon structures due to the surfactants’ chirality and increased spacer hydrogen bonding with the surrounding water molecules [83]. To test the effects of both the alkyl (10C and 12C atoms) and spacer chain length (carbon = 2–10) on their degradability and antibacterial effectiveness and their acute toxicity on Photobacterium phosphoreum and Daphnia magna, Perez in 2002 synthesized the Nα-Nω-bis(N-acyl-arginine), and α-ω-alkylendiamides. It was discovered that the aqueous toxicity of the spacer, which has six methylene groups, is less than that of ordinary monoquats and that it is quickly biodegradable.

These surfactants make up a brand-new family of low-toxic compounds with exceptional surface qualities and strong antibacterial activity. A detrimental structural factor for the bis (Args)’ behaviour in the environment is the rise in hydrophobicity [84].

Higher nonpolar tail alkyl chain lengths in Gemini surfactant, according to Mitjans et al.’s research, promote hemolysis. The hemolytic activities of cocoamidopropyl betain, n-lauroyl arginine ethyl ester, and decyl glucoside, increased by 1.5- and 1.1-folds, respectively, when the surfactant with 10 carbon atoms alkyl chain length was added, whereas the hemolytic activities of Gemini surfactant and the decyl glucoside mixture increased by fivefold. This knowledge will make it easier to use Gemini surfactants in medicinal and cosmetic applications [85]. Castillo et al. used Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus to compare the antibacterial effects of the bis(Nα-caproyl-l-arginine)-1,3-propane-diamine-dihydrochloride toward chlorhexidine-di HCl. As opposed to chlorhexidine dihydrochloride, they discovered that the suggested Gemini surfactant had superior antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria that bring about cell death [86].

According to Tavano et al., arginine-based surfactants with natural antibacterial activity can be formulated into vesicles as a substitute for other drug delivery systems. They combine single-chain and Gemini surfactants to create a stable colloidal composition. The additive types and concentrations (such as dilauroyl-phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol) introduced to the formulation have an impact on the size of micelles. The size of spacer chains and vesicles had a substantial impact on both hemolytic and antimicrobial action. The penetration is higher, the minimal inhibitory concentration is lower, and the HC50 value is lower the smaller the aggregates are. Long alkyl chain Gemini derivatives produced higher minimum inhibitory concentration and larger vesicles. The biological characteristics of these surfactants are also impacted by the addition of substances like cholesterol or dilinoleoyl phosphatidylcholine [87].

4.3.3 Lipoamino acid/glycerol based surfactants

Monoacyl-arginine glycerides (140R, 120R, and 100R): According to CMC, the values were 6, 1.3, and 0.2 nm, respectively. However, the values are lower than those associated with a standard surfactant of a 12-carbon straight-chain [88], and two orders of magnitude more than lysophosphatidylcholine with a similar alkyl-chain length [89]. Additionally, single-chain arginine surfactant CMC value was higher than that of glycerol-based surfactants [56].

Diacyl arginine glyceride surfactants 88R, 1010R, 1212R, and 1414R: According to electro-conductivity measurements, CMCs were 0.25 mM, 0.3 mM, 1.1 mM, and 5 mM [90]. For the same surfactants, CMC determined using the surface tension method produced lower values. In order to lower the CMC compared to N-α-acyl arginine, the glycerol group in monoacyl arginine glyceride increases the distance between α-carbon atom and ionic group of the hydrophobic group [88]. Compared to short-chain phospholipids with comparable alkyl-chain lengths, diacyl arginine glyceride surfactants have a greater CMC [91]. The CMC is reduced compared to monoacyl arginine glycerides by the addition of second alkyl chain.

With increasing surfactant content, the 1010R compound aggregates changed from vesicle to ribbon form, as demonstrated by static light scattering. At low levels, polydisperse vesicles emerge, and at millimolar concentrations, ribbons form. The size and shape of the aggregates determine which form appears first [92].

Dialyl-glycerides from acetyl-arginine 1414RAc and 1212RAc: Due to the two chains of hydrocarbon in these compounds, very low concentrations of aqueous solution cause them to aggregate. The value for both surfactants was closer to 0.1 mM when calculated using the electrical conductivity approach. They might show a change in phase from vesicles to ribbons [60,90]. Lozano et al. investigated 1414RAc’s toxicity, biodegradability, and antibacterial properties. The surfactant and the model membrane interacted on a binary surface. Under CMC, the dynamic surface tension of the 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine membrane; however, 1414RAc has been lowered to achieve its lowest value. The visco-elasticity of monolayer showed strong surfactant characteristics and nonideal mixing behaviour (caused by electrostatic contact) [93].

Dilauroyl-glycerol acetyl-arginine: 1,2-dilauroyl-rac-glycero-3-(N-α-acetyl l-arginine) (1212RAc), 1,3-dilauroyl-glycerol acetyl l-arginine) (12RAc12). However, the compounds have been seen as multilamellar stacks that are characteristic of liquid crystal smectic systems. Pérez et al. (2005) formulated 1, 2-diacyl-3-O-(l-arginyl)-rac-glycerol.2hydrochloride and 1-acyl -3-O-(l-arginyl)-rac-glycerol.2hydrochloride with C8–C14 alkyl-chain and examined the aquatic toxicity by application of the bioluminescent bacteria test as well as the Daphnia Magna test. It was discovered that the aforementioned surfactants were less hazardous and unsafe than typical quaternary ammonium-based chemicals [58]. 1,2-diacyl-3-O-(l-arginyl)-rac-glycerol with a moiety of alkyl-chain length C8–C14 was created by Benavides et al. in 2004. The potential for toxicity on red blood cells was compared to the uptake of neutral red (NRU) 24 h after dose on cell lines. They concluded that all surfactants had a cytotoxic effect when NRU decreased. IC50 value was found to range between 1 mol 1−1 (for HTAB) and 565 mol 1−1 (for 12,12-l-arginine) for concentrations that resulted in a 50% inhibition of NRU [28].

4.3.4 Bola-amphiphiles

Both the diblock complex F4R4 (where F = phenylalanine and R = arginine) and its bola-amphiphile counterpart R2F4R2 were explored by Mello et al. They discovered that the R4F4 molecule has strong melanoma tumour cell penetration and killing capacity, in contrast to the poorer less cytotoxicity and absorption displayed by the bola-amphiphile R2F4R2 [94].

To highlight its antibacterial effectiveness against the gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, Castelletto et al. studied the binding ability and self-assembling characteristic of the arginine-capped bola-amphiphile peptide RA3R (A = alanine and R = arginine) using the model membrane. Skin fibroblast cells tolerated this compound at concentrations between 0.01 and 0.25%, and it was found to be a powerful antibacterial [95]. Silva et al. showed how the self-assembly of the arginine-capped bola-amphiphile analogue RFL4RF in the form of a nanotube in the aqueous solution [62].

4.3.5 Surfactants based on double-chain arginine chains

Octadidecanoyl (LANHC18), myristoyl (LANHC14), and decyl (LANHC10). The critical aggregation concentration of the vesicles, which were created in the aqueous medium, is lower than that of a single-chain esterified arginine-derived surfactant [64].

5 Advancements in the use of compounds based on arginine

5.1 Transfection of DNA

Various cationic Gemini surfactants with arginine residues were discovered, displaying their capability to carry genetic material to cells [40].

5.2 Drug carriers and liposomes

Several authors have recently studied peptide vesicles and acyl amino acids. The functional liposome encapsulation efficiency covered with peptides was higher. Furthermore, the vesicle formation entrapment efficiency by means of long aliphatic chain N-α-acyl amino acid was found to be comparable to that of lecithin liposomes.

Cocoyl-arginine ethyl-ester was the first arginine-based cationic surfactant that was commercially available and came in the shape of a pyrrolidone-carboxylic acid salt. It has been used to make antistatic agents, disinfectants, hair conditioners, and antimicrobial agents. This surfactant quickly breaks down and is safe for the skin and eyes [96]. Another form of surfactant that is based on amino acids and can be found in products designed for hair care is called quaternary acyl protein [97].

5.3 Gene therapy

When single-chain cationic surfactants based on the amino acid arginine such as arginine lauryl-amide, lauryl arginine methyl-ester, and O-lauryl arginine-amide were included to water comprising anionic surfactants, they freely developed vesicles, i.e., hexosomes as well as cubosomes that contained DNA material. Hence, genetic drug delivery via biocompatible vehicles is a possibility [98].

6 The special characteristics of arginine-based biomaterials in gene delivery systems

6.1 Mechanisms of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) interaction with cellular membranes

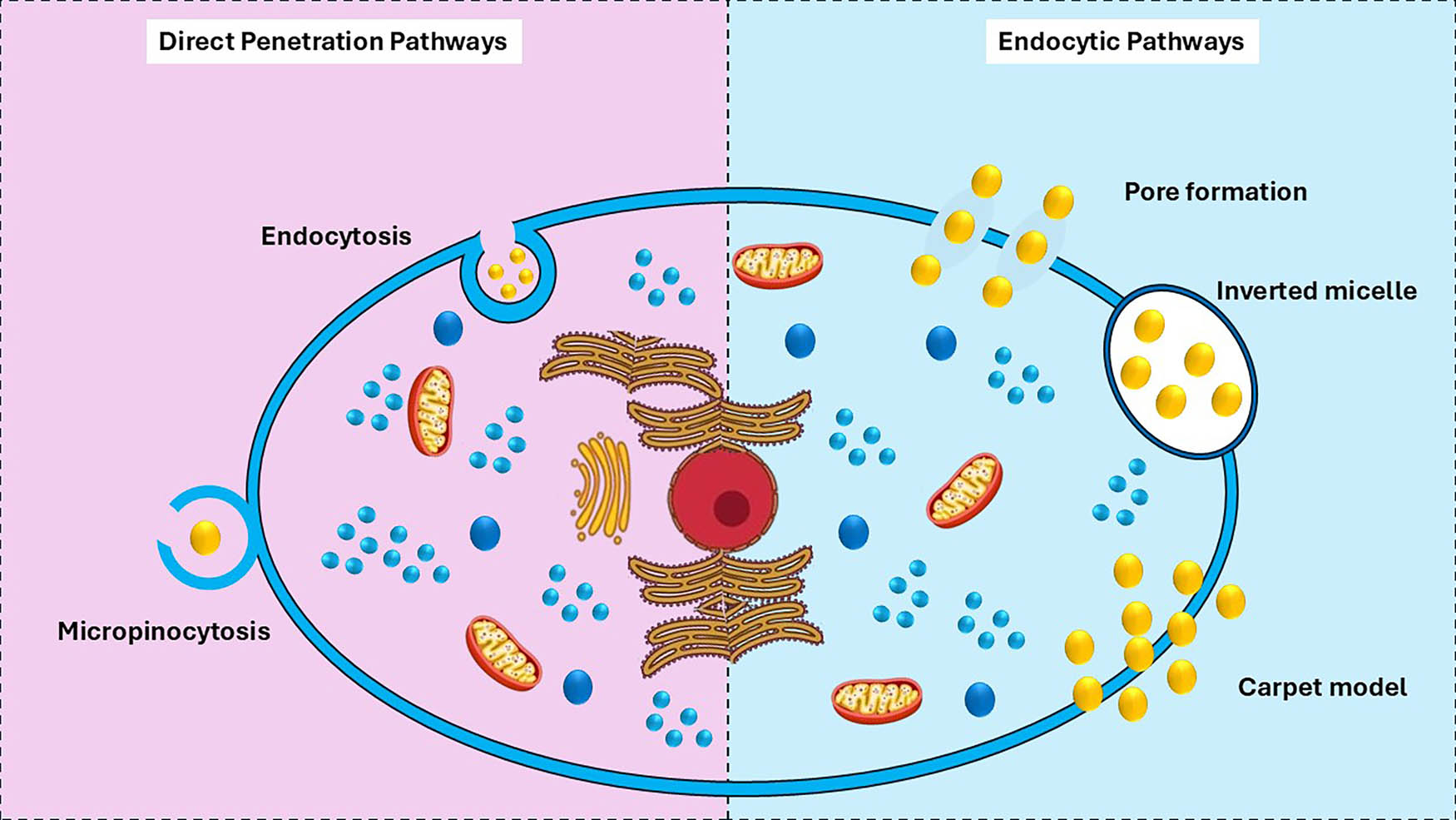

CPPs represent a versatile platform for cell delivery of diverse biomolecular cargos including nucleic acids, proteins, and small molecules. Their interaction with cellular membranes involves two principal pathways: involved in both direct translocation and endocytosis. Specific biochemical and biophysical processes ensure, and distinct advantages apply to each pathway, as illustrated in Figure 4.

The cellular uptake processes of CPPs and their conjugates are depicted via endocytic routes on the left and direct pathways on the right.

6.1.1 Direct translocation

Direct translocation is a nonvesicular process through which CPPs shuttle through the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. CPPs are usually typically enriched with positively charged residues, such arginine and lysine, to allow robust electrostatic interactions with the negative cell membrane components, associated with phospholipids and glycosaminoglycans [99]. Electrostatic binding is the first step in a process initiated by positively charged amino acid residues of CPPs forming strong electrostatic interactions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans of the cell surface, although numerous other interactions have been demonstrated [100]. Such interaction results in large lipid reorganization inside the bilayer, which destabilizes the membrane and favours transient pore formation [100]. These transient pores allow direct cytosolic translocation of CPPs, thus bypassing endosomal pathways and decreasing the degradation risks.

6.1.2 Endocytosis

This alternative pathway that CPPs exploit for intracellular delivery is called endocytosis. Depending on the type of CPP and the properties of the cargo, this vesicular transport route relies on several endocytic processes including macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and caveolin-dependent endocytosis [101]. CPPs bind to the cell membrane and internalize into endocytic vesicles through CPPs internalization. Thus, CPPs are then required to pass through the endosomal membrane and release their payload into the cytosol to deliver the associated cargo. Membrane destabilization and escape efficiency are often enhanced via specific structural or auxiliary agents in this crucial step [99,102].

Despite their potential, CPPs require rigorous tuning to ensure efficiency and safety. Improving endosomal escape, decreasing off-target effects, and balancing cytotoxicity are all important issues in CPP-based delivery systems [102]. To address these challenges, strategies like as peptide engineering and the introduction of endosomatic drugs are being intensively investigated.

7 Arginine-based polymer gene delivery system

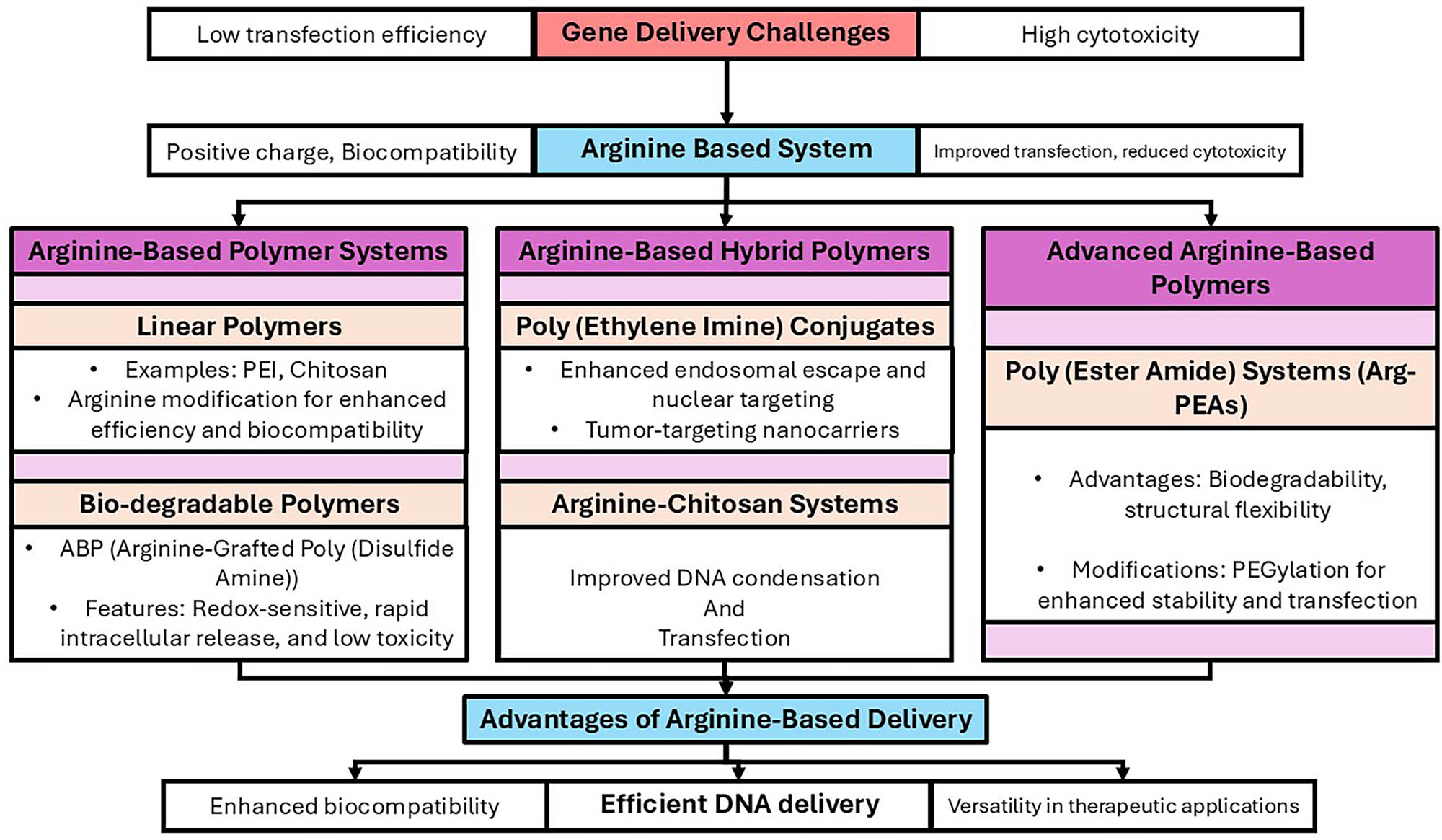

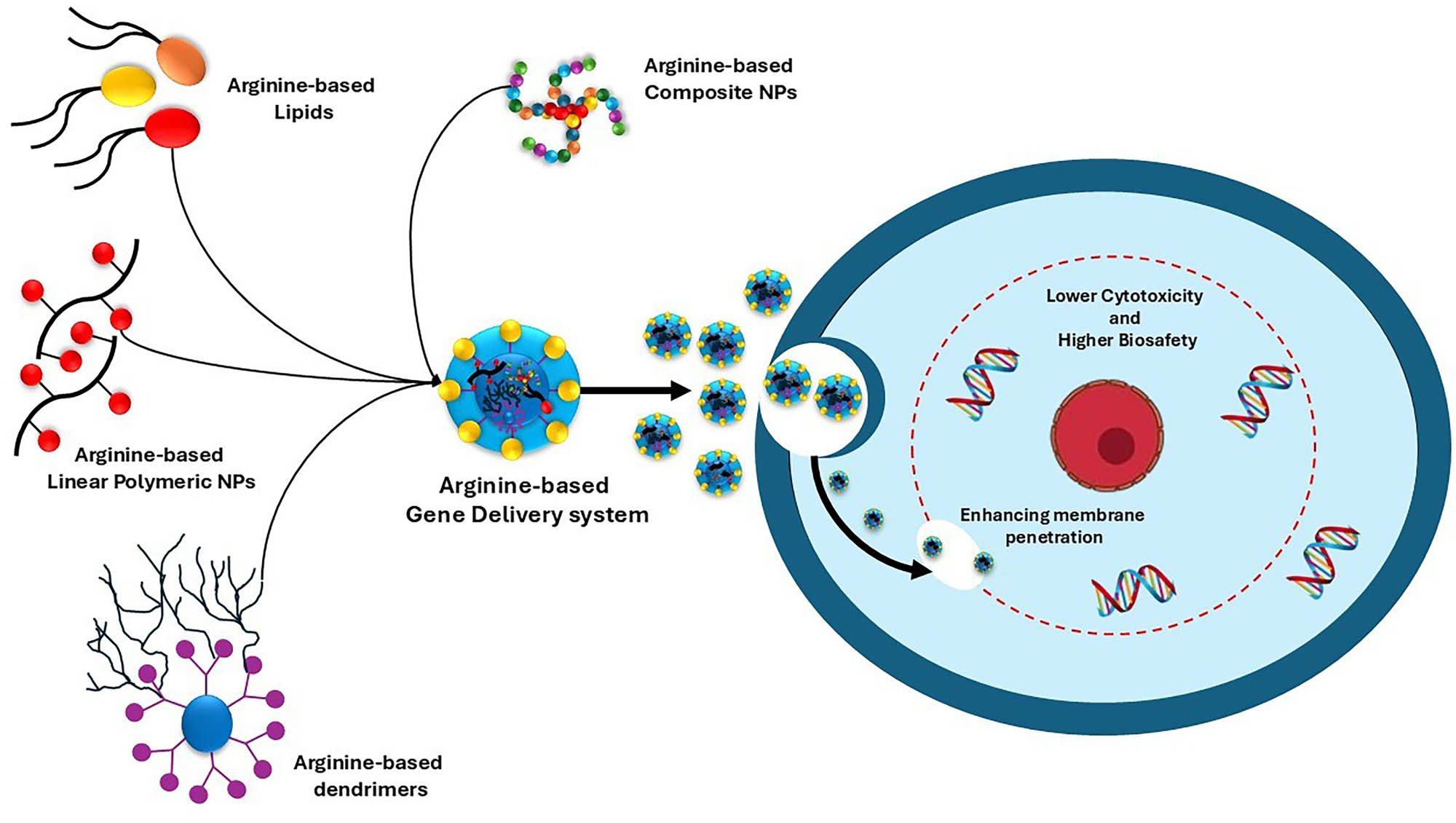

To overcome the restrictions that the standard gene delivery technology imposes in terms of transfection efficacy and biosafety, various arginine-based biomaterials were developed and produced, many of which were influenced by CPPs, as illustrated in Figure 5 and Table 2. The carboxyl and active amino groups in arginine allow it to promptly change biomaterials and its function as a monomer for the entry into the biomaterials backbone, giving designers of gene delivery systems a flexible tool.

A schematic illustration of the benefits and drawbacks of arginine-based gene delivery platforms. The flowchart describes the shift from the difficulties associated with gene transport (high cytotoxicity and low transfection effectiveness) to the creation of systems based on arginine. These systems are divided into three categories: advanced arginine-based polymers (poly (ester amide) systems), arginine-based hybrid polymers (PEI conjugates and arginine-chitosan systems), and arginine-based polymer systems (linear and biodegradable polymers). A summary is provided of the benefits of arginine-based administration, which include improved biocompatibility, effective DNA delivery, and adaptability in therapeutic applications.

7.1 Arginine-based linear polymer gene delivery system

The majority of linear cationic polymers used in transferring of gene, including gelatin and chitosan (Cs), poly(l-lysine), and poly (ethylene imine) (PEI), have positive charges that allow oligonucleotides to condense on them [103–106]. With the addition of arginine, several common gene delivery methods were further investigated to get over the limitations of their cytotoxicity from charged properties, as illustrated in Scheme 1.

Various arginine-based gene delivery systems with lower cytotoxicity and enhanced membrane penetration are depicted.

7.1.1 Arginine-modified PEI

Although PEI, which has a molecular weight of 25 kDa, has been used extensively and has long been considered the “gold standard.” Its use in clinical therapy is severely constrained by the homopolymer’s significant concentration-dependent toxicity [107]. Studies have shown that adding arginine in a different configuration improves transfection effectiveness and reduces PEI’s cytotoxicity. Morris and Sharma attempted to combine the PEI through arginine-functionalized oligo(-alkylaminosiloxane) ((PSiDAAr)n) for amalgamation of oligo(-alkylaminosiloxane)’s adsorptive endocytosis and biocompatibility, in addition to arginine’s capacity to penetrate membranes and localise to the nucleus. When cultivated with serum and 98% viable cells, the (PSiDAAr)5 group demonstrated approximately 1.5 times the effectiveness of PEI transfection when compared to the four various ratios of 15, 10, 5, and 1 of oligo(-alkylaminosiloxane) [108]. The nanosystem of (PSiDAAr)n was used to couple conjugates of poly(ethylene-glycol) folic acid for the capability of tumour targeting in the ensuing years. When compared to undecorated PEI, the resultant nanocarrier demonstrated higher transfection efficiency because the orientated arginine moiety was crucial in adjusting localization throughout the cells, including nucleus [109].

7.1.2 Arginine-modified chitosan (Cs)

Additional natural material for gene delivery systems is chitosan, which has a number of benefits including low cost, soft tissue compatibility, and stability, as well as the potential to form nanoparticles with DNA condensation, which would better shield DNA from being digested by enzymes like DNase [110]. In addition, positively charged chitosan has extremely less cytotoxicity than that of the majority of synthetic polymers that consist of PEI. On the other hand, chitosan encompassed two noticeable flaws. The first is that it disintegrates poorly in the aqueous solution because it has a lot of amino groups in its molecular structure, which at pH 7.4 are only slightly protonated. In addition, their poor transfection efficiency is a more difficult issue, and adding arginine may be able to overcome these obstacles. In comparison to Cs/DNA self-assemble nanoparticles (CSNs), alarginine-chitosan (Arg-Cs)/DNA self-assembled nanoparticles (ACSNs) had an advanced efficiency of transfection [11]. Since that time, gene delivery has given the ACSNs a lot of attention. To investigate multiple potential endocytic routes, Zhang et al. produced various inhibitors and treated fluorescent-assisted ACSNs and CSNs with A10 cells. The persistent involvement of caveolin-mediated endocytosis in ACSNs internalization was therefore revealed and verified from the findings. In contrast, groupings of CSNs including the caveolin-mediated and clathrin-mediated pathways comprise all internalization pathways [111]. In addition, poly-ethylenimine-conjugated chitosan (CS-PEI), a mixture of PEI and CS, was developed for improved performance. Contrarily, poly-ethylenimine-conjugated chitosan (CS-PEIArg) polymers with arginine modifications can effectively condense pDNA and produce complexes with nanoparticle diameters of about 170 nm. Particularly, CS-PEI-Arg gene delivery system showed decreased cellular toxicity compared to CS-PEI, and most significantly, CS-PEIArg (N/P = 50) demonstrated efficiency that was, respectively, 2.3 times increased than that of CS-PEI (N/P = 20) and 4.2 times greater in comparison to native PEI (N/P = 10) [112].

7.1.3 Arginine-grafted biodegradable poly (disulfide amine) (ABP)

There are a variety of selection strategies for stimuli-responsive arginine-based vectors, all of which aim to combine the distinctive responsive qualities of synthetic polymeric vectors and the arginine benefits. A ABP polymer was created by grafting arginine to poly(cystamine-bisacrylamide-diaminohexane) (poly(CBA-DAH)). This polymer was used as a process of liner redox-sensitive gene delivery. Following disulfide bond biodegradation in an environment of reducing cytoplasm, it is possible to stimulate ABP/DNA polyplexes to start releasing DNA. This novel sort of polymer is now more likely to penetration into membranes of the cell, delivering loads quickly in the intracellular environment according to Kim et al.’s initial study. ABP can achieve biodegradation of redox-responsive in the cytoplasm and has outstanding DNA condensation abilities even at a polymer/DNA weight ratio of 2. The ABP nanoparticle demonstrated stability in the serum environment, demonstrating its reliability as a nanocarrier. Compared to commercial PEI and native poly (CBA-DAH), attributes of low toxicity as well as improved transfection efficacy were confirmed in mammalian cell lines [113].

7.1.4 Arginine-based poly (ester amide) s (Arg-PEA)

Arginine has the power to alter biomaterials since it is a polymeric monomer and a part of the backbone of a linear polymer with an amide bond and an ester link, such as poly (ether-ester amide), poly (ether-ester urea), and poly (ether ester amide) (PEEA) [114]. These linear polymers often have positive charges, strong water solubility, and biodegradability, which gives them the potential to carry genes [115]. One of the most often used gene-transferring materials among them is arginine-based PEAs because it combines the benefits of polyamides and polyesters with great biodegradability and biocompatibility. The adaptable design of the molecular structure of arginine-based PEAs makes them a flexible platform for various therapeutic genes [116–118].

In cellular studies, Yamanouchi et al. revealed that the Arg-PEAs have the capability to carry targeting DNA throughout the entire cell by transfecting vascular smooth muscle cells of rat with an Arg-PEA/DNA composite [119]. Like this, Song et al. thoroughly investigated the synthesis processes and probable Arg-PEAs DNA transport and concluded that they are less dangerous than commercial transfection agents (PEI and Superfect). The 2-Arg-2-S/DNA proportion is 17/1 during gel-electrophoresis experiments, and PEA/DNA complexes have a DNA condensate content of nearly 100% [117,120]. Good DNA condensing also raises the controlled DNA release possibility being challenging, as a prior work found that Arg-PEAs/DNA cannot escape the lysosome. Due to the Arg-PEA structural flexibility, numerous changes might be made to overcome these obstacles. For instance, Wu and colleagues demonstrated that Arg-PEEA might result in improved biocompatibility transfection and effectiveness than that of the commercial transfection reagent, for instance, Lipofectamine-2000 by incorporating the polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains into the diol backbone. Accumulating the PEG chains markedly increased the flexibility of the polymer chain, allowing Arg-PEEAs to achieve higher efficiency of transfection than Arg-PEAs with more fixed structures [114]. Arg-PEA library in 2018 was formulated by altering the carbon chains of diacids, diols, and salt forms. In addition, they methodically calculated the relationship between PEA structure and charge density, hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity, and the relationship between the ability and structure of nucleic acid delivery/interaction, demonstrating that Arg-PEA performs a significant position among the vast array of arginine-based gene transporters [121].

A rapid overview of the main characteristics, benefits, and challenges of several arginine-modified nanosystems, as well as their uses and limitations

| Nanosystem | Key features | Advantages | Challenges | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arginine-modified PEI | Conjugation of arginine to PEI | Enhanced transfection efficiency; reduced cytotoxicity due to arginine functionalization | Residual toxicity at high N/P ratios; limited in vivo testing | [108,122] |

| Arginine-modified Chitosan (Arg-Cs) | Natural polymer modified with arginine | Improved DNA condensation; enhanced transfection efficiency; low cost | Poor solubility in aqueous solutions; limited scalability for large-scale applications | [3,123] |

| PEGylated Arg-PEA | Incorporation of PEG into arginine-based polyester amides | Reduced immune recognition; increased circulation time; pH-responsive release | High production cost; stability concerns in extreme conditions | [124,125] |

| CS-PEI-Arg | Hybrid polymer combining chitosan, PEI, and arginine | Improved biocompatibility; effective nanoparticle formation; reduced cellular toxicity | Complex synthesis protocols; limited mechanistic studies | [126,127] |

| ABP (arginine-based polymers) | Linear arginine-rich polymers | Effective for nucleus localization; versatile functionalization options | Requires advanced manufacturing techniques; varying results across cell lines | [128,129] |

8 Role of nanotechnology in enhancing arginine-based delivery systems

Incorporation of nanotechnology in arginine-based delivery systems has revolutionized the treatment of key limitations such as poor stability, suboptimal targeting efficiency, and ineffective intracellular delivery of therapeutic agents. Through nanoscale engineering, the functionality and applicability of arginine-based polymers have been improved in numerous biomedical applications.

8.1 Stabilization of arginine-based systems

The incorporation of nanoscale carriers significantly enhances the stability of arginine-based delivery systems due to encapsulation of therapeutic agents. In physiological environments, these nanocarriers protect the payload from premature release by enzymatic degradation. For instance, colloidal nanoparticles coated with biodegradable materials, such as PEGylation, reduce aggregation and enhance solubility as well as extend systemic circulation time [130,131]. Therapeutic agents are kept intact until they arrive at the site of action because of this enhanced stability [132,133]. Furthermore, hybrid nanostructures consisting of arginine-based polymers and lipids or inorganic materials extend stability and modify release kinetics of encapsulated drugs.

8.2 Targeting efficiency through surface engineering

Precise functionalization of arginine-based delivery systems can be accomplished using nanotechnology, leading to increased targeting efficiency. Researchers conjugated ligands, such as folic acid, transferrin, or antibodies, to the surface of arginine-based nanocarriers and have generated systems that rely on receptor-mediated endocytosis for targeted drug delivery [131]. For example, arginine nanoparticles modified with folic acid have been shown to exhibit superior uptake by cancer cells expressing folate receptors, resulting in improved therapeutic efficacy and a decrease in off target effects [134]. In addition, dual targeting strategies have been explored using receptor-specific ligands in combination with stimuli-responsive release systems (such as pH-sensitive release) to enhance precision in complex biological environments [135].

8.3 Improved intracellular delivery

The delivery of drugs into the intracellular space remains one of the biggest problems for modern drug delivery. The inherent cell-penetrating properties of arginine-rich polymers are due to their positive charge and ability to interact with negatively charged cell membranes. This capability is amplified in nanotechnology, wherein nanocarriers are designed to promote endosomal escape, some of which are enlisted in Table 3. Particulate polymers that include arginine are known to trigger a proton sponge effect; a release of therapeutic agents into the cytoplasm without lysosomal degradation [136].

A compilation of various nanosystems that have been functionalized with arginine, an amino acid known for its potential in enhancing the properties of nanomaterials

| Nano system type | Composition/materials | Size range | Functionalization with arginine | Key properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene oxide (GO) | GO functionalized with arginine | 100 nm–1.5 μm | Enhanced distribution, reduced agglomeration | Anticancer properties, improved cellular uptake | [138] |

| Arginine-functionalized graphene | Composite for supercapacitor applications | 200–500 nm | Utilizes arginine for synthesis | High-performance energy storage | [139] |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAPTb) nanoparticles | HAPTb nanoparticles modified with arginine | 50–200 nm | Improved uptake efficiency in endothelial cells | Enhanced biocompatibility and targeting | [140] |

| Magnetic nanoparticles (Mag-Arg) | Magnetic nanoparticles modified with arginine | 10–100 nm | Used as carriers for magnetic solid-phase extraction | Biocompatibility, non-toxicity | [141] |

| Methacrylic block copolymer nanoparticles | Arginine-functionalized methacrylic copolymers | 100–300 nm | pH-modulated drug release capabilities | Responsive to pH changes | [142] |

8.4 Multifunctional nanocarriers for theragnostic

Nanotechnology integration can lead to multifunctional arginine-based nanocarrier development for theranostic applications: the combination of therapy and diagnostics. Nanoparticles loaded with therapeutic agents and imaging probes (such as fluorescent dyes or magnetic particles) carrying arginine functionality can be used for real-time tracking and protection of treatment efficacy [131,137]. Such systems are highly beneficial in cancer therapy for precision medicine, which depends on simultaneous imaging and drug delivery.

Stimuli-responsive arginine-based nanocarriers that release their payload upon exposure to environmental triggers include pH, temperature, and redox conditions have emerged in recent years from nanotechnology. All these systems improve drug delivery specificity and efficacy. Although these innovations translate into clinical practice, challenges such as large-scale production, regulatory approval, and long-term safety need to be overcome.

9 Innovative drug delivery system composed of arginine and arginine-based compounds

The application of arginine and products based on arginine as drug delivery methods is becoming an increasingly popular topic of discussion in the modern day. Products based on arginine are used not only as drugs but also as media for the efficient dissemination of other drugs for a wide variety of applications. These applications include the treatment of diseases, the diagnosis of diseases, and the delivery of genes.

At present, gene therapy excels in any complex disease treatment. However, a few issues, such as biosafety and transfection capacity, among others, limit the effectiveness of the treatment. Many studies in this field demonstrate the arginine usage as a vehicle for drug delivery in method of linear polymers, lipids, dendrimers, and composite nanoparticles [3]. Gene therapy is thought to be a powerful and effective method for treating many difficult diseases quickly. Gene vectors are essential for efficient gene therapy because they decide whether the altered gene possibly will be loaded for delivery into target cells. Traditional gene vectors confront certain significant obstacles, particularly in terms of biosafety and trans-membrane effectiveness. Recent developments in gene delivery systems of arginine have been motivated by CPPs, which exhibit outstanding trans-membrane efficiency and biosafety. The arginine superiority and its mode of action in increasing membrane penetration are briefly discussed in this study. Then, a thorough discussion of the four different forms of arginine-based gene vectors – typical linear polymers, lipids, dendrimers, and gene vectors of arginine-based composite – and their uses follows. Finally, the present and potential problems associated with arginine-based gene delivery methods for the future are investigated [3]. In more recent times, the demonstration of the bone repair process has also been shown to involve the use of arginine-based gene delivery. According to a report, the presence of arginine-chitosan/plasmid DNA nanoparticles that code for the gene of BMP-2 encourages osteogenic differentiation [143]. Two cationic polymers that are efficient in terms of ability of transfection and decreased cytotoxicity were also used to create liposomes [27]. Human hepatoma cells (Huh7), human colon epithelial (COS-7) cells, human cervical carcinoma (HELa) cells, and human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) were used to investigate the effectiveness of poly-l-arginine coated liposomes and arginine-chitosan self-assembled DNA nanoparticles as gene-drug delivery systems [11,144]. There have also been other arginine-based composites used to treat cancer. For example, mesospheres designed specifically for lung cell cancer, arginine-albumin microspheres [145], and arginine-treated graphene [146]. A micellar formulation using arginine-modified diblock copolymer of poly (ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone), which increases the efficiency of endocytosis and is used to destroy tumour cells, was also created and evaluated [147].

One of the magnetic nanoparticles made from ferric chloride and ferrous oxide and protected by means of l-arginine was used in an immune magnetic assay because it forms a composite with anti-chloramphenicol monoclonal antibodies at room temperature exhibiting superparamagnetism [23,148]. The effectiveness of poly-arginine or arginine-rich CPPs for drug transfer from the nose to the brain was demonstrated in animal studies for the allergic rhinitis treatment and other central nervous system diseases [149]. l-arginine-capped gold nanoparticles have also demonstrated their critical significance in interacting with several biological molecules [150]. To test the thermal expansion, specific heat, dielectric constant, and other properties of l-arginine phosphate monohydrate as a function of temperature, one of its crystalline structures was created. This complex was then used as a diagnostic tool to generate harmonic frequencies for laser diffusion [151]. Lyotropic liquid crystals can be used as a perfect delivery system for drugs for a functional moiety of hydrophilic drug in an aqueous environment since they are made from a oleoyl-ethanolamide ternary mixture, arginine, and water [152,153].

A topical formulation of arginine designed as a cream with a urea basis was used as a medicinal agent, according to other literature, to treat xerosis [154], gel formulation for anal fissure [155], wound dressing consisting of chitosan nanofibers with an arginine surface modification that releases arginine over time [25], polypeptide arginine/lysine loaded microneedle patch, acetyl octapeptide, and additional biomolecules to combat early skin ageing [156], enhanced arginine molecules skin penetration that demonstrated active hair growth using a nanostructured lipid carrier [157]. A novel membrane made of arginine derivatives containing chitosan-hyaluronic acid and thiazolidine-4-one was created and successfully used to treat a burn wound rat model in vivo [26].

9.1 Strategies to enhance biocompatibility and mitigate toxicity in arginine-based nanosystems

Arginine-based nanosystems have transformed gene delivery technologies; however, there remain obstacles such as cytotoxicity and biocompatibility. However, several attempts have been made to address these issues using innovative strategies. Structural modifications, including PEGylation (or conjugating polyethylene glycol), reduce the surface charge and nonspecific interaction of the lectin with the cellular and serum proteins for better biocompatibility. Incorporation of pH-sensitive linkages also permits targeted release of cargo within acidic intracellular compartments, such as endosomes, to prevent off target effects [158]. Emerging biocompatibility screening methods have also helped improve the safety of these nanosystems. Cytotoxic effects, including mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, are rapidly evaluated with high-throughput in vitro assays. 3D cell culture models also better reflect in vivo environments than traditional 2D assays provide, providing deeper insights into biocompatibility [159].

Optimization of charge density, as excessive positive charges from arginine residues can disrupt cell membranes. This optimization will balance these charges to improve transfection efficiency, while the use of these charges is minimal in toxicity. Mitigating oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity is further facilitated by using auxiliary agents, such as antioxidants or hydrophilic polymers. Long-term safety, biodistribution, and immune functionality of the nanosystem are evaluated via advanced imaging techniques and immune response evaluations in vivo [160]. Moreover, nanosystem design optimization, as well as prediction of toxicities, is increasingly enabled by computational modelling and machine learning before synthesis. These approaches can smooth out the development process by streamlining the cycle of trial and error. Overall, these strategies can provide a comprehensive set of approaches to overcome biocompatibility and toxicity hurdles of arginine-based nanosystems and enable their clinical translation.

9.2 Future prospects

Arginine-based delivery systems are highly promising for future possibilities, including industrial-scale production and coupling to emerging biotechnologies. The key challenge is in scaling up arginine-based polymer production with cost efficiency and sustainability. Such issues can be addressed using advanced bioprocessing techniques, including microbial fermentation and green chemistry approaches, to conduct polymer synthesis from renewable resources and environmentally benign methods. Furthermore, arginine-based systems possess the modularity to tailor the systems for targeting specific therapeutic applications, providing great versatility in the design of next-generation delivery platforms. Arginine-based systems possess unique properties, including their biocompatibility, transfection efficiency, and low cytotoxicity, and emerging technologies including CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing are poised to greatly benefit from these unique properties. Gene editing therapies that these systems enable could provide improved precision and efficacy, benefiting their safety and clinical applicability. Also, nanotechnology and bioinformatics are likely to synergize with these systems by refining their delivery mechanisms as well as extending their medical use.

Delivery systems based on arginine also play a potentially major role in addressing global health challenges, including development of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics for rare genetic diseases. Potential for combination therapy, where simultaneous delivery of multiple therapeutic agents is realized, may revolutionize treatment modalities and improve patient outcome. In addition, the synthesis of arginine-based polymers involves the incorporation of biodegradable materials and renewable feedstocks, which fulfil the principles of green chemistry, and leads towards completing a pathway to industrial-scale production of such polymers. The incorporation of arginine-based delivery systems with emerging technologies and their scalability for industrial applications hold promise as transformative tools in therapeutic innovation. Nevertheless, more research and interactions in the field of their concentration will be needed to fully realize their potential and deal with the issues.

10 Conclusion

Polymer systems based on arginine top play a promising role in overcoming the problems related to gene delivery like low transfection efficiency and high cytotoxicity. Due to their unique physicochemical properties, such as positive charge, biocompatibility, and modifiability of their structure, they are excellent platforms for therapeutic gene delivery. Different categories of arginine-based systems were reviewed including linear polymers, bio-degradable polymers, hybrid systems, and advanced arginine-based polymers, which provide selective advantages for different therapeutic requirements. Recent studies on arginine-modified systems of PEI and chitosan-based systems revealed their capacity to improve transfection efficiency while avoiding cytotoxicity. Progress is also evident with the development of biodegradable polymers, like arginine grafted poly (disulfide amine), towards redox sensitivity and intracellular release. These systems include hybrid systems such as PEI conjugates and arginine chitosan complexes with advanced functionalities such as endosomal escape and tumour targeting. Poly (ester amide) (Arg-PEAs) are advanced systems, which are a huge advance with biodegradability, but combined with structural flexibility and structural stability due to PEGylation. This review points out the unique features of arginine-based delivery systems, including superior biocompatibility, more efficient DNA delivery, and their advantage in the therapeutic applications. These systems overcome shortfalls in traditional gene delivery systems and open up the potential for such systems in novel applications such as CRISPR-based genome editing. Arginine-based systems can be integrated with advanced technologies, such as nanotechnology and precision gene editing, to greatly advance the ways genetic and therapeutic interventions can be achieved. Further modification to increase specificity and efficiency and scaling up the production processes for industrial applications have been suggested as areas of future research. Arginine-based delivery platforms hold promises in emerging technologies, including CRISPR-Cas systems, to propel agriculture, medicine, and environmental biotechnology breakthroughs. Arginine-based systems help to address current challenges and leverage cutting-edge innovations, making them a critical part of the next generation of gene therapy and precision medicine, advancing human health and sustainable development.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: LN: data gathering and organization and writing initial manuscript; YL: critical review and revising the manuscript; JX: critical review and revising the manuscript; SL: supervision and guidance of the work and finalization of the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Puri A, Loomis K, Smith B, Lee J-H, Yavlovich A, Heldman E, et al. Lipid-based nanoparticles as pharmaceutical drug carriers: from concepts to clinic. Crit Reviews™ Ther Drug Carr Syst. 2009;26(6):523–80.10.1615/CritRevTherDrugCarrierSyst.v26.i6.10Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Wang S, Zhao Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Li L. Recent advances in amino acid-metal coordinated nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Chin J Chem Eng. 2021;38:30–42.10.1016/j.cjche.2021.03.013Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Zhou Y, Han S, Liang Z, Zhao M, Liu G, Wu J. Progress in arginine-based gene delivery systems. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(26):5564–77.10.1039/D0TB00498GSuche in Google Scholar

[4] Zhang RX, Wong HL, Xue HY, Eoh JY, Wu XY. Nanomedicine of synergistic drug combinations for cancer therapy–Strategies and perspectives. J Controlled Rel. 2016;240:489–503.10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Dreaden EC, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Structure–Activity relationships for Tumor-targeting gold nanoparticles. In handbook of nanobiomedical research: Fundamentals, applications and recent developments: Volume 1. Materials for nanomedicine. USA: World Scientific; 2014. p. 519–63.10.1142/9789814520652_0014Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Peng F, Zhang W, Qiu F. Self-assembling peptides in current nanomedicine: versatile nanomaterials for drug delivery. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27(29):4855–81.10.2174/0929867326666190712154021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Kuei B, Gomez ED. Chain conformations and phase behavior of conjugated polymers. Soft Matter. 2017;13(1):49–67.10.1039/C6SM00979DSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Sim S, Figueiras A, Veiga F. Modular hydrogels for drug delivery. Portugal: Scientific Research; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Lim SB, Banerjee A, Önyüksel H. Improvement of drug safety by the use of lipid-based nanocarriers. J Controlled Rel. 2012;163(1):34–45.10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.06.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Liu BR, Li J-F, Lu S-W, Lee H-J, Huang Y-W, Shannon KB, et al. Cellular internalization of quantum dots noncovalently conjugated with arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2010;10(10):6534–43.10.1166/jnn.2010.2637Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Gao Y, Xu Z, Chen S, Gu W, Chen L. and Li YJIjopArginine-chitosan/DNA self-assemble nanoparticles for gene delivery: In vitro characteristics and transfection efficiency. Int J Pharmaceutics. 2008;359(1–2):241–6.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.037Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Hsan N, Dutta PK, Kumar S, Koh J. Arginine containing chitosan-graphene oxide aerogels for highly efficient carbon capture and fixation. J CO2 Util. 2022;59:101958.10.1016/j.jcou.2022.101958Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Zhu K, Li J, Lai H, Yang C, Guo C, Wang C. Reprogramming fibroblasts to pluripotency using arginine-terminated polyamidoamine nanoparticles based non-viral gene delivery system. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9:5837.10.2147/IJN.S73961Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Bryan MC, Dunn PJ, Entwistle D, Gallou F, Koenig SG, Hayler JD, et al. Key Green Chemistry research areas from a pharmaceutical manufacturers’ perspective revisited. Green Chem. 2018;20(22):5082–103.10.1039/C8GC01276HSuche in Google Scholar

[15] Zern BJ, Chu H, Osunkoya AO, Gao J, Wang Y. A biocompatible arginine‐based polycation. Adv Funct Mater. 2011;21(3):434–40.10.1002/adfm.201000969Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Xu G, Liu X, Liu P, Pranantyo D, Neoh KG, Kang ET. Arginine-based polymer brush coatings with hydrolysis-triggered switchable functionalities from antimicrobial (Cationic) to antifouling (Zwitterionic). Langmuir. 2017;33(27):6925–36.10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01000Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Sandle T, Vijayakumar R, Saleh Al Aboody M, Saravanakumar S. In vitro fungicidal activity of biocides against pharmaceutical environmental fungal isolates. J Appl Microbiology. 2014;117(5):1267–73.10.1111/jam.12628Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Market PE. Pharmaceutical Excipients Market by Product (Organic (Oleochemicals, Carbohydrates) Inorganic (Calcium Carbonate), Functionality (Fillers, Binders, Lubricants, Diluents), Formulation (Oral, Parenteral), Application (Stablizers) & Region - Global Forecast to 2028. USA: Markets and Markets; 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Salih N, Salimon J. A review on eco-friendly green biolubricants from renewable and sustainable plant oil sources. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2021;11(5):13303–27.10.33263/BRIAC115.1330313327Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Patel DV, Patel MN, Dholakia MS, Suhagia BN. Green synthesis and properties of arginine derived complexes for assorted drug delivery systems: A review. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2021;21:100441.10.1016/j.scp.2021.100441Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Rahman KM. Food and high value products from microalgae: market opportunities and challenges. Microalgae biotechnology for food, health and high value products. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 3–27.10.1007/978-981-15-0169-2_1Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Silveira BM, Barcelos MC, Vespermann KA, Pelissari FM, Molina G. An overview of biotechnological processes in the food industry. Bioprocessing for biomolecules production. Wiley; 2019. p. 1–19.10.1002/9781119434436.ch1Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Wang Z, Zhu H, Wang X, Yang F, Yang XJN. One-pot green synthesis of biocompatible arginine-stabilized magnetic nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(46):465606.10.1088/0957-4484/20/46/465606Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Pang X, Wu J, Chu C-C, Chen X. Development of an arginine-based cationic hydrogel platform: synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(7):3098–107.10.1016/j.actbio.2014.04.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Hoseinpour Najar M, Minaiyan M, Taheri A. Preparation and in vivo evaluation of a novel gel-based wound dressing using arginine–alginate surface-modified chitosan nanofibers. J Biomater Appl. 2018;32(6):689–701.10.1177/0885328217739562Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Iacob A-T, Drăgan M, Ghețu N, Pieptu D, Vasile C, Buron F, et al. Preparation, characterization and wound healing effects of new membranes based on chitosan, hyaluronic acid and arginine derivatives. Polymers. 2018;10(6):607.10.3390/polym10060607Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Sarker SR, Aoshima Y, Hokama R, Inoue T, Sou K, Takeoka S. Arginine-based cationic liposomes for efficient in vitro plasmid DNA delivery with low cytotoxicity. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:1361–75.10.2147/IJN.S38903Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Benavides T, Mitjans M, Martı́nez V, Clapés P, Infante MR, Clothier R, et al. Assessment of primary eye and skin irritants by in vitro cytotoxicity and phototoxicity models: an in vitro approach of new arginine-based surfactant-induced irritation. Toxicology. 2004;197(3):229–37.10.1016/j.tox.2004.01.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Qin L, Gao H. The application of nitric oxide delivery in nanoparticle-based tumor targeting drug delivery and treatment. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2019;14(4):380–90.10.1016/j.ajps.2018.10.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Mudakavi RJ, Vanamali S, Chakravortty D, Raichur AM. Development of arginine based nanocarriers for targeting and treatment of intracellular Salmonella. RSC Adv. 2017;7(12):7022–32.10.1039/C6RA27868JSuche in Google Scholar

[31] Fan Y, Liu Y, Wu Y, Dai F, Yuan M, Wang F, et al. Natural polysaccharides based self-assembled nanoparticles for biomedical applications–A review. Int J Biol Macromolecules. 2021;192:1240–55.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.10.074Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Ma Y, Mou Q, Sun M, Yu C, Li J, Huang X, et al. Cancer theranostic nanoparticles self-assembled from amphiphilic small molecules with equilibrium shift-induced renal clearance. Theranostics. 2016;6(10):1703.10.7150/thno.15647Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Li T, Takeoka S. Smart liposomes for drug delivery, in Smart nanoparticles for biomedicine. Netherland: Elsevier; 2018. p. 31–47.10.1016/B978-0-12-814156-4.00003-3Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Durante WJ. Role of arginase in vessel wall remodeling. Front Immunol. 2013;4:111.10.3389/fimmu.2013.00111Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Shi HP, Most D, Efron DT, Witte MB, Barbul A. Supplemental L‐arginine enhances wound healing in diabetic rats. Wound Repair Regeneration. 2003;11(3):198–203.10.1046/j.1524-475X.2003.11308.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed