Abstract

Metal-free phthalocyanine (H2Pc) has been widely used as photosensitive semiconductors in the organic optoelectronics field because of its unique planar molecular structure and high photocarriers’ generation efficiency. Herein, this paper related to a new facile and efficient one-step method for preparing specific crystal form of H2Pc with high crystallinity through ball-milling process, in which α-H2Pc can be prepared directly by dry ball-milling, and β-H2Pc and X-H2Pc can be simply obtained through wet ball-milling in butanone solvent at different temperatures. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to characterize the crystal stability of α-H2Pc, β-H2Pc, and X-H2Pc, which revealed that all the three crystalline H2Pc prepared had excellent crystal stability under different mechanical conditions.

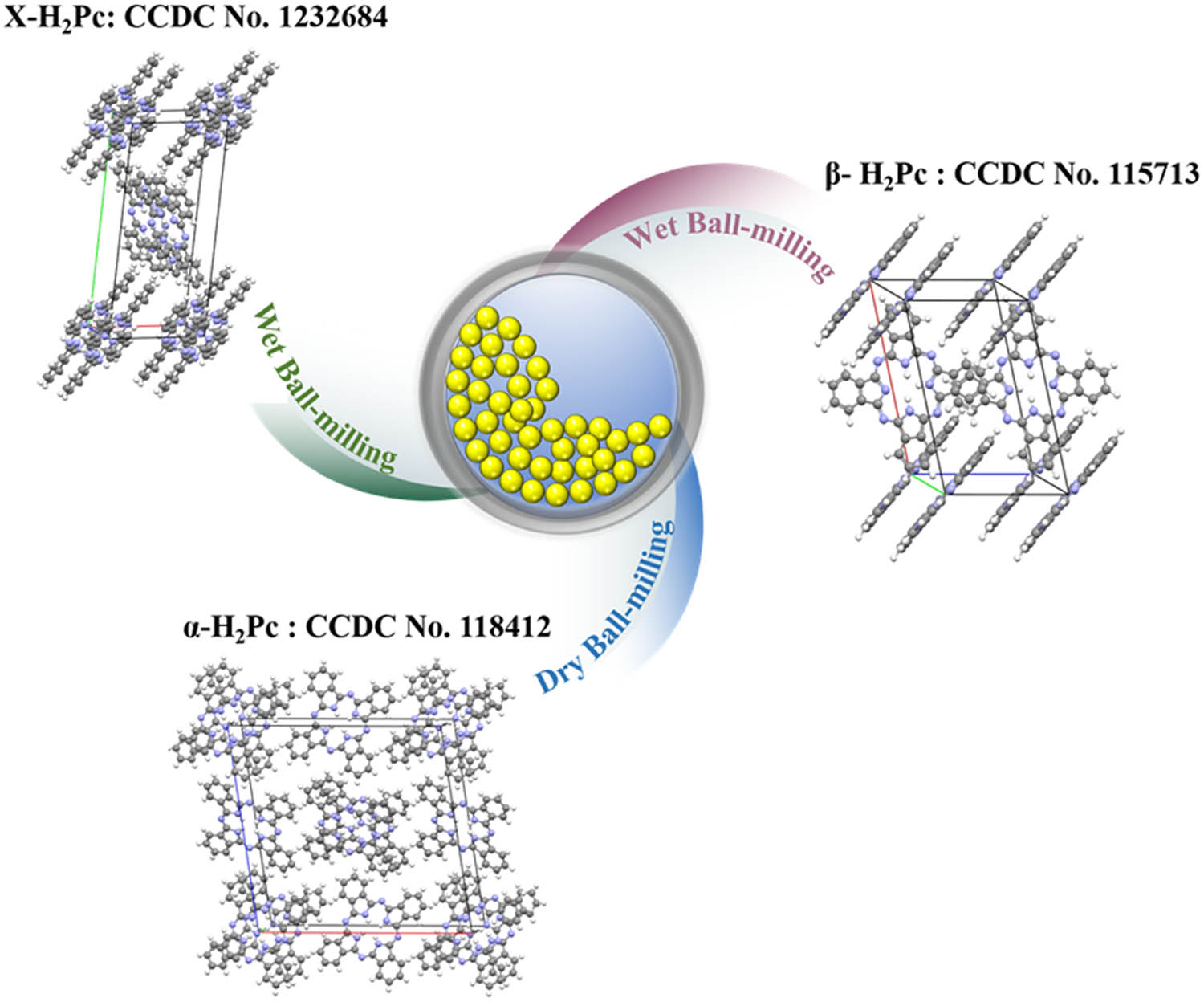

Graphical abstract

α-H2Pc, β-H2Pc, and X-H2Pc with excellent crystal stability can be simply prepared by dry/wet ball-milling process.

1 Introduction

As an important member of phthalocyanine (H2Pc) compounds, metal-free H2Pc has been widely used as photosensitive materials in the field of organic optoelectronics, such as organic photoconductor (OPC) [1], organic solar cells (OSCs) [2], photodynamic therapy (PDT) [3], and so on [4,5]. H2Pc has a nearly planar molecular structure containing a highly delocalized two-dimensional 18 π electron conjugation system composed of four isoindole units. This special molecular structure makes H2Pc have the advantages of low toxicity, high thermal-light stability, and excellent photosensitivity in the visible and near-infrared region [6]. The interaction between neighboring molecules in metal-free H2Pc crystal is very weak, and this weak interaction makes different molecular stacking modes have similar molecular interaction energy. The change of molecular packing mode makes metal-free H2Pc, like other semiconductor materials, also have crystal polymorphism phenomenon [7,8], for example, α-form, β-form, and X-form. Different crystal forms of H2Pc exhibit different photophysical and photochemical properties because of the different packing mode of molecules in the unit cell. X-H2Pc has the highest photosensitivity, followed by α-H2Pc and β-H2Pc [6].

Currently, the process methods for regulating the crystal form of H2Pc mainly include thermal-induced transformation [9], vacuum sublimation [10], and crystal seed-induced transformation [11,12]. Generally, such traditional process methods always require a large amount of energy consumption, extremely high vacuum equipment, and expensive crystal seeds. In addition, the vacuum sublimation method needs post-annealing treatment to prepare specific crystal forms, and the bath preparation yield is very low. Therefore, these traditional process methods are not cost-effective and cannot be mass-production oriented.

In this paper, we report a new facile and efficient one-step method for preparing α-H2Pc, β-H2Pc, and X-H2Pc through ball-milling process. The crystal form of H2Pc can be controlled by simply adjusting the time and temperature of ball-milling process. Moreover, all the three crystalline H2Pc prepared had excellent crystal stability under different mechanical conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis and purification of crude H2Pc

2.1.1 Synthesis

About 180 mL of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone was placed in a 500 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a reflux condenser, mechanical stirrer, thermometer, and gas inlet tube. A steady stream of argon is passed through the solution. Then 51.2 g of phthalonitrile, 16 mL of formamide, and 3.12 g of sodium methoxide were added to the flask. The mixture was stirred at 195°C for 6 h and then cooled down to 120°C. After hot filtration, the filter cake was washed with methanol and deionized water to obtain the crude H2Pc (42.7 g, 83%).

2.1.2 Purification

Twenty grams of crude H2Pc was added to 120 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid at about 3°C. After stirring for 2 h, the dark solution was slowly dropped into 600 mL of well-stirred ice water. The H2Pc particles precipitated immediately after allowing the mixture to stand for 30 min. The H2Pc were isolated through filtration. The filter cake was washed with deionized water and dried in a vacuum freeze dryer for several hours to obtain the purified H2Pc (18.6 g, 93%).

2.2 Preparation of α-H2Pc, β-H2Pc, and X-H2Pc

2.2.1 α-H2Pc

Twenty grams of the purified H2Pc was placed in a sealed glass jar half-filled with 400 g of zirconia balls (ϕ = 1 mm) and rotated at 60 rpm. α-H2Pc can be prepared when dry ball-milling time exceeds 1 h.

2.2.2 X-H2Pc

Twenty grams of the purified H2Pc and 200 mL of 2-butanone were placed in a sealed glass jar half-filled with 400 g of zirconia balls (ϕ = 1 mm). The sealed glass jar was rotated at 60 rpm at 20°C. X-H2Pc can be prepared when wet ball-milling time exceeds 1 h.

2.2.3 β-H2Pc

Twenty grams of the purified H2Pc and 200 mL of 2-butanone were placed in a sealed glass jar half-filled with 400 g of zirconia balls (ϕ = 1 mm). The sealed glass jar was rotated at 60 rpm at 30°C. β-H2Pc can be prepared when wet ball-milling time exceeds 9 h.

2.3 Crystal form stability

The crystal form stability of the prepared H2Pc was respectively studied by wet ball-milling and ultrasonic in 2-butanone under different time.

2.4 Solvent recovery

2-Butanone was used as a crystal form transformation regulating solvent in the transformation of X- and β-H2Pc. To save cost and reduce environmental pollution, the solvent recovery of 2-butanone was carried out, and the specific operation steps were as follows: the mixture after ball-milling was first filtered through a 100 mesh sieve to obtain the zirconia balls and butanone dispersion of H2Pc, and then the butanone dispersion of H2Pc was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm to obtain H2Pc solid and butanone mixture. Finally the 2-butanone mixture was distilled at 80°C to obtain a pure 2-butanone solution. The average recovery of 2-butanone was about 91.2% after repeated recovery calculation.

3 Results and discussion

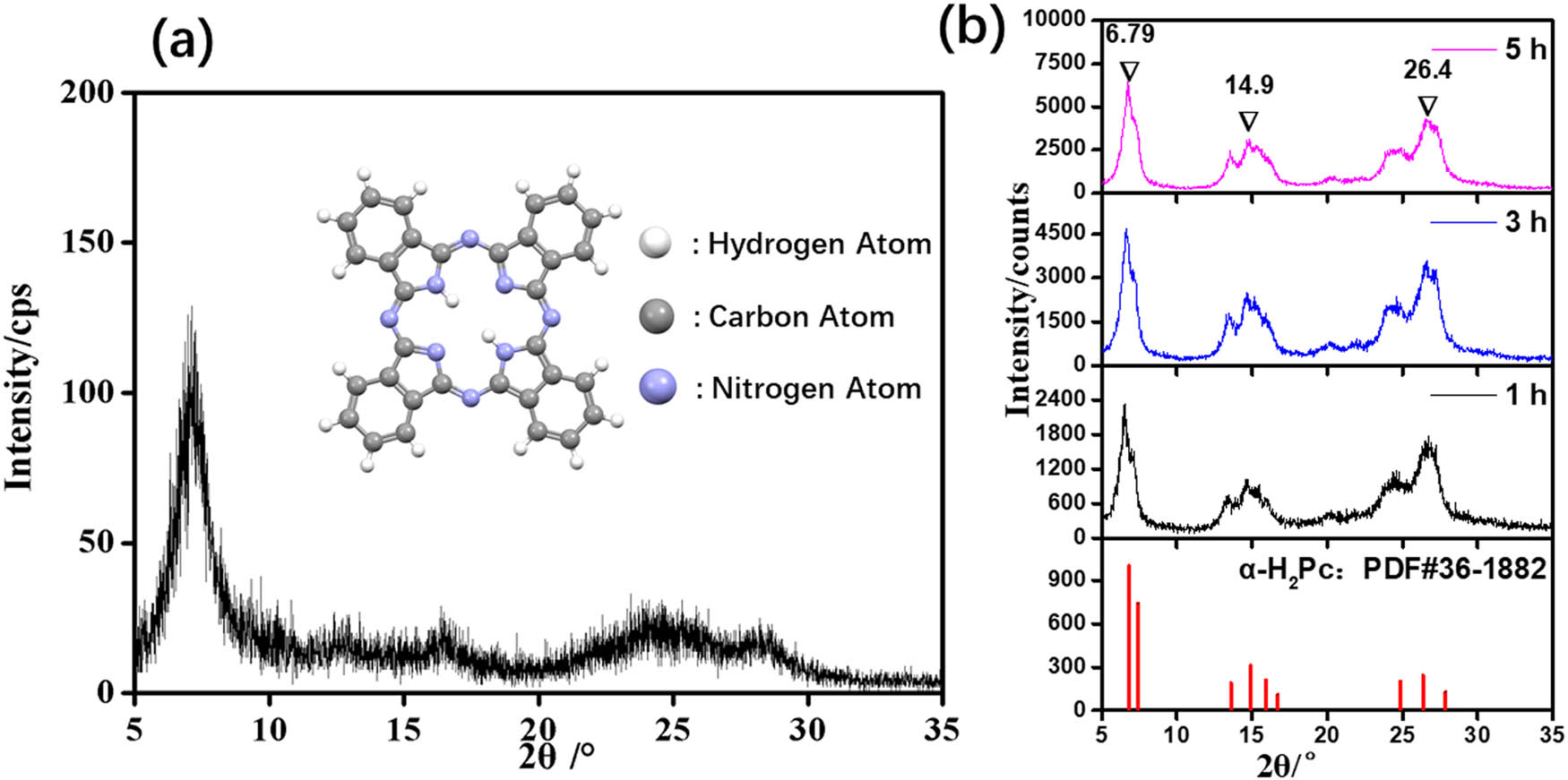

Figure 1a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the H2Pc after purification. As observed, the intensity of all diffraction peaks in this diffraction pattern is particularly weak, for instance, the intensity of the strongest diffraction peak at 7.2° is only 129 cps. This phenomenon indicates that the crystal form of the purified H2Pc is amorphous, which as the raw material is very beneficial to transform amorphous H2Pc into other target crystal forms. Figure 1b presents the XRD patterns of the purified H2Pc after dry ball-milling treatment at different time. It can be found that the longer the ball-milling time, the stronger the intensity of XRD diffraction peak. This suggests that the crystallinity of the purified H2Pc increases with the prolongation of dry ball-milling time. Meanwhile, the characteristic diffraction peaks of the XRD patterns obtained in this experiment are in good agreement with the standard JCPDS card No. 36-1882 of α-H2Pc. Furthermore, according to CCDC No. 118412, the detailed unit cell parameters of α-H2Pc are as follows: space group: C 2/n (15), cell: a = 26.121(4) Å, b = 3.7970(7) Å, c = 23.875(3) Å, α = 90°, β = 94.16(2)°, γ = 90° [13]. The very typical peaks at 6.8°, 14.9°, and 26.4° of the XRD patterns could be indexed to (200), (004), and (113) crystal planes of α-H2Pc, respectively. Therefore, α-H2Pc can be simply prepared by direct dry ball-milling of the purified H2Pc.

(a) XRD pattern of the purified H2Pc, the inset picture is a ball–stick model of H2Pc molecule; (b) XRD patterns of the H2Pc obtained from different dry ball-milling time.

Figure 2a shows XRD patterns of the H2Pc obtained from different wet ball-milling time at 20°C. The characteristic diffraction peaks of the XRD patterns are consistent with the standard JCPDS card No. 42-1889 of X-H2Pc. The intensity of obvious peaks indicates the prepared X-H2Pc with a high degree of crystallinity. Furthermore, according to CCDC No. 1232684, the detailed unit cell parameters of X-H2Pc are as follows: P21/a (14), cell: a = 10.63 Å, b = 23.15 Å, c = 4.89 Å, α = 90°, β = 95.98°, γ = 90° [14]. The characteristic peaks at 7.5°, 9.1°, 16.7°, 17.3°, 22.3°, and 28.5° could be indexed to (020), (110), (200), (140), (121), and (231) crystal planes of X-H2Pc, respectively. Therefore, X-H2Pc can be readily obtained by wet ball-milling at 20°C for only 1 h.

XRD patterns of the H2Pc obtained from different wet ball-milling time at 20°C (a) and 30°C (b).

Figure 2b presents the XRD patterns of the H2Pc obtained from wet ball-milling at 30°C. Clearly, the characteristic peaks of X-H2Pc at 7.5° and 16.7° decrease with the increase in wet ball-milling time, which proves that X-H2Pc gradually transforms into β-H2Pc. According to the standard JCPDS cards of X-H2Pc (PDF#42-1889) and β-H2Pc (PDF#37-1884), it is known that the strongest diffraction peak position is at 7.5° for X-H2Pc and 9.0° for β-H2Pc. Therefore, the relative abundances of X-H2Pc and β-H2Pc (

Relationship between

| Time (h) | I 7.5° (counts) | I 9.0° (counts) | I 7.5°/I 9.0° (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,486 | 10,726 | 51.1 | 51.1 |

| 3 | 5,060 | 15,413 | 32.8 | 32.8 |

| 5 | 2,233 | 12,893 | 17.3 | 17.3 |

| 7 | 1,253 | 10,386 | 12.1 | 12.1 |

| 9 | 326 | 9,506 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| 11 | 260 | 10,373 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

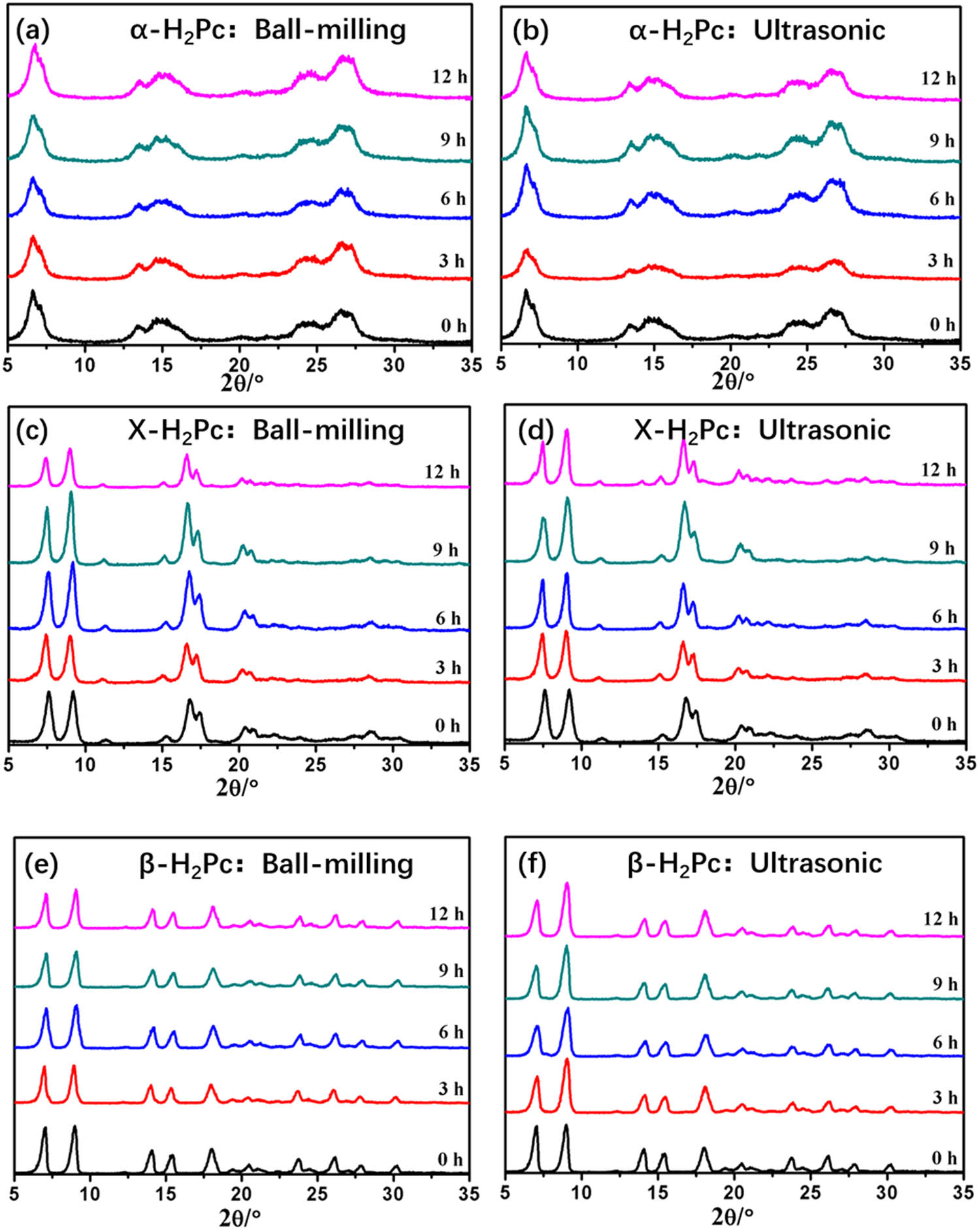

As we all know, H2Pc compounds have the crystal polymorphism phenomenon and are prone to crystal transformation under mechanical forces. Therefore, the common mechanical forces, such as ball-milling and ultrasonic, are used to investigate the crystal stability of the prepared α-, X- and β-H2Pc. As shown in Figure 3, none of the three crystal forms of H2Pc presents obvious change in the XRD patterns after ultrasonic or ball-milling treatment for 1–12 h. The characterization results indicate that the α-, X-, and β-H2Pc prepared by dry/wet ball-milling present excellent crystal stability.

XRD patterns of α-, X-, and β-H2Pc before and after ball-milling treatment (a, c, and e) and ultrasonic (b, d, and f) for 0–12 h, respectively.

4 Conclusions

In summary, we developed a new facile and efficient method for preparing α-, X-, and β-H2Pc through ball-milling process. α-H2Pc can be prepared directly by solvent-free dry ball-milling process. X-H2Pc and β-H2Pc can be simply obtained through wet ball-milling in butanone solvent at 20°C and 30°C, respectively. Both ball-milling and ultrasonic experiments proved that all the prepared α-, X-, and β-H2Pc had excellent crystal stability. We believe that this work will significantly promote the development of the crystalline transformation process of H2Pc with reduced preparation time and cost.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 22008147), Special Research Fund of Education Department of Shaanxi (No. 19JK0153), Provincial College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (No. S201910708037), and Scientific Research Foundation of Shaanxi University of Science and Technology (No. 2017BJ-17).

-

Author contributions: Xiaolong Li: writing – original draft and methodology; Yuxi Feng: writing – original draft; Chenyang Li: methodology and formal analysis; Huahui Han: methodology; Xueqing Hu: methodology; Yongning Ma: visualization; Yuhao Yang: writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Weiss DS, Abkowitz M. Advances in organic photoconductor technology. Chem Rev. 2010;110:479–526.10.1021/cr900173rSuche in Google Scholar

[2] Suzuki A, Okumura H, Yamasaki Y, Oku T. Fabrication and characterization of perovskite type solar cells using phthalocyanine complexes. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;488:586–92.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.05.305Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Alexeree SMI, Sliem MA, EL-Balshy RM, Amin RM, Harith MA. Exploiting biosynthetic gold nanoparticles for improving the aqueous solubility of metal-free phthalocyanine as biocompatible PDT agent. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2017;76:727–34.10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.129Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Lü XF, Hu NJ, Li J, Zhang ZQ, Tang W. Catalytic activity to lithium-thionylchloride battery of different transitional metal carboxylporphyrins. J Porphyr Phthalocyanines. 2014;18:290–6.10.1142/S1088424614500011Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Xu ZW, Li K, Wang RY, Duan XT, Liu QQ, Zhang RL, et al. Electrochemical effects of lithium-thionyl chloride battery by central metal ions of phthalocyanines-tetraacetamide complexes. J Electrochem Soc. 2017;164:A3628–32.10.1149/2.0651714jesSuche in Google Scholar

[6] Law KY. Organic photoconductive materials: recent trends and developments. Chem Rev. 1993;93:449–86.10.1021/cr00017a020Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Li XL, Xiao Y, Wang SR, Yang YH, Ma YN, Li XG. Polymorph-induced photosensitivity change in titanylphthalocyanine revealed by the charge transfer integral. Nanophotonics. 2019;8:787–97.10.1515/nanoph-2018-0223Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Xu ZW, Li K, Hu HL, Zhang QL, Cao LY, Li JY, et al. From bulk to nano metal phthalocyanine by recrystallization with enhanced nucleation. Dye Pigment. 2017;139:97–101.10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.12.008Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Pu BY, Li XG, Wang SR, Xiao Y, Li ZQ, Chen YF. A new solvent-free preparation approach for polymouphous metal-free phthalocyanine photoconductive materials and their performances. Chem Ind Eng. 2017;34:1–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Amar NM, Gould RD, Saleh AM. Structural and electrical properties of the α-form of metal-free phthalocyanine (α-H2Pc) semiconducting thin films. Curr Appl Phys. 2002;2:455.10.1016/S1567-1739(02)00156-6Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Radler Jr RW, Penfield NY. Method of converting alpha phthalocyanine to the X-form, U.S. Patent 3594163; 1971.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Brach PJ, Six HA. Method of converting alpha phthalocyanine to the X-form, U.S. Patent 3657272; 1971.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Janczak J. Discussion-comment on the polymorphic forms of metal-free phthalocyanine. Refinement of the crystal structure of α-H2Pc at 160 K. Pol J Chem. 2000;74:157.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Hammond RB, Roberts KJ, Docherty R, Edmondson M, Gairns R. X-form metal-free phthalocyanine: Crystal structure determination using a combination of high-resolution X-ray powder diffraction and molecular modelling techniques. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2. 1996;8:1527–8.10.1039/p29960001527Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Matsumoto S, Matsuhama K, Mizuguchi J. β metal-free phthalocyanine. Acta Cryst C. 1999;55:131–3.10.1107/S0108270198011020Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Xiaolong Li et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis