Abstract

Candida genus includes many hazardous and risky species that can develop resistance toward various antifungal types. Metals nanoparticles (NPs) possess powerful antimicrobial actions, but their potential human toxicity could limit their practices. The algal polysaccharide fucoidan (Fu) was extracted from the macro-brown algae, Cystoseira barbata, analyzed, and used for biosynthesizing nanoparticles of silver (Ag-NPs) and selenium (Se-NPs). The extracted Fu had elevated fucose levels (58.73% of total monosaccharides) and exhibited the main biochemical characteristic of customary Fu. The Fu biosynthesis of Ag-NPs and Se-NPs was achieved via facile direct protocol; Fu-synthesized NPs had 12.86 and 16.18 nm average diameters, respectively. The ultrastructure of Fu-synthesized NPs emphasized well-distributed and spherical particles that were embedded/capped in Fu as combined clusters. The Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs anticandidal assessments, against Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, and Candida parapsilosis, revealed that both NPs had powerful fungicidal actions against the examined pathogens. The ultrastructure imaging of subjected C. albicans and C. parapsilosis to NPs revealed that Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs triggered remarkable distortions, pore formation, and destructive lysis in cell surfaces within 10 h of exposure. The innovative usage of C. barbata Fu for Ag-NP and Se-NP synthesis and the application of their composites as powerful anticandidal agents, with minimized human toxicity, are concluded.

1 Introduction

Algal polysaccharides (including fucoidan [Fu], laminarin, and alginate from brown algae; agarose, carrageenans, and porphyran from red algae; and ulvan from green algae) significantly represent a precious group of bioactive compounds due to their bioactive physiochemical properties, which encourage their biomedical/therapeutic applications (e.g., antiviral, immunostimulants, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, and antimicrobial agents) [1,2].

Fu had attracted great attention as a valuable polysaccharide with treasurable bioactivities, which is mainly extracted from brown algae species [3]; it is from the main bases of seaweeds’ pharmacological effects. The Fu possessed elevated biosafety, biocompatibility, and numerous bioactivities (including its antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antiviral, antiallergic, hypotensive effects, and antimicrobial potentialities) [4,5,6,7,8]. The Fu anticancer potentiality is well documented and was attributed to apoptosis induction in cancer cells, inflammation suppression, and antioxidation properties [6,8,9].

Nanotechnology involved the methods for assembling or modifying the molecules and atoms to become in “nano” scales (with particles’ diameter of 1–100 nm of atoms and up to 1,000 nm for molecules) and the applications of these nanoparticles (NPs) that attained extraordinary and superior physiochemical/biochemical properties [10]. Nanomaterial applications attained great successfulness, particularly in biomedical, pharmaceutical, and healthcare researches. The NPs’ promising efficiency arises from their huge surface area, minute sizes, elevated strength, stability, conduction, and unique biochemical properties [11]. The biomedical applications of NPs included their usage in biosensors and nanomedicine (e.g., for constructing antimicrobial agents, treating diabetic wounds, wound dressing, drug carrying/delivery, and disorder diagnosis) [10,12].

The transformation of materials to nanoforms frequently used different procedures (e.g., biological, physical, and chemical). The physical approaches are highly expensive and energy consuming and require specialized equipment, whereas the chemical protocols frequently generate many toxic and hazardous residues [13,14]. However, the biological NP synthesis (green synthesis) was successfully used to transform various ions/compounds to nanostructures with elevated efficiency, safety, consistency, and bioactivity [15,16]. Many biological systems/derivatives were utilized directly for the biosynthesis of metal NPs, including microorganisms, plant extracts, phyto-constituents, algal extracts, biopolymers, and proteins [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The algal extracts (micro and macro species) and polysaccharides (Fu, carrageenan, alginate, laminaran, etc.) were capable of reducing/stabilizing various metals in nanoforms [12,19,20,22,23,24,25]; higher activities and augmented characteristics were exhibited from the phycosynthesized NPs.

Silver (Ag), the transitional metal with outstanding properties like conductivity and wide antimicrobial spectrum, can be used in numerous biomedical, environmental, and pharmaceutical, wounds and burns healing, food packaging, medical imaging, and hygienic textiles disciplines [26]. Both Ag ions and Ag nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) have forceful wide antimicrobial potentialities. The Ag-NPs are more powerful because of their higher surface area, smaller particle sizes, and great surface energy, which augment the adsorption of Ag-NPs onto microbial cells and interaction with them [12,16,18,27]. The anticandidal activities of Ag-NPs were proved and have attained great attention to fight pathogenic yeasts [13,17,28,29,30].

The biosynthesis of Ag-NPs was successfully achieved; the usage of biopolymers (especially marine polysaccharides) as reducing and stabilizing materials was reported to enhance bioactivity, biosafety, and compatibility of Ag-NPs [12,24,26,28].

The mineral, selenium (Se), is an essential trace element for preserving human health and functions of human body, with a recommended daily intake of 0–300 mg [31]. Selenium nanoparticles (Se-NPs), especially the biosynthesized NPs, were validated for having extraordinary attributes (e.g., antioxidant, anticancer, antibacterial, and antifungal activities) [15,21,32,33]. The biosynthesis of Se-NPs (using plants and algal extracts, biopolymers, and microorganisms) generated more stabilized and compatible NPs with elevated bioactivities [25,31,32,34]. Although numerous investigations reported nanometal biosynthesis using plant derivatives (phytosynthesis), inconsequential studies investigated the direct NP biosynthesis using biopolymers (e.g., Fu), especially with their potential usage as antifungal composites.

The Candida sp. (including ∼150 species) could have threatening health concerns because they possess endosymbiosis for humans and cause numerous infections, especially in immunosuppressed hosts. About 80% of Candida infections (candidiasis) are caused by Candida albicans, albeit the infections from non-Candida albicans (including Candida glabrata and Candida parapsilosis, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, and Candida auris) became more frequent [35]. The Candida sp. infections, either superficial (e.g., vaginal, oral, or mucocutaneous) or profound (e.g., septicemia or myocarditis), are currently serious challenges to humans; many Candida species could acquire multiple resistances to accustomed antifungal agents [36]. Many positive attempts were conducted for achieving effectual anticandidal agents from NP formulations/composites [13,32,37]; the main challenge for that is the cytotoxicity of metal NPs toward mammalian tissues [30], which could be minimized via conjugation/capping of these NPs within polymeric molecules [12,28,34].

Accordingly, our goals in this study were to extract Fu from the macro-brown algae, Cystoseira barbata, and to use the extracted Fu for innovative biosynthesis of Ag-NPs and Se-NPs. The anticandidal activities and action of Fu-synthesized NPs were also investigated toward many pathogenic Candida sp. strains.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and chemicals

All chemicals/reagents used in experiments, for example, Na2SeO3 (≥98%), AgNO3 (≥99.0%), NaOH, CaCl2, KOH, ethanol, HCl, methanol, and chloroform were of analytical grades and were purchased from the accredited supplier (Sigma Aldrich Inc., St Louis, MO).

2.2 Algae sampling and processing

The brown alga (C. barbata sp.) was collected from Abu-Qir Bay, Egypt (around 30.07°E and 32.34°N) in August 2020. Samples were identified and verified by phycology specialists in the National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Alexandria, Egypt, and then seaweed samples were thoroughly cleansed with deionized water (DW), drained for 60 min, dried at 43°C with hot air, and pulverized to a fine powder.

2.3 Fu extraction

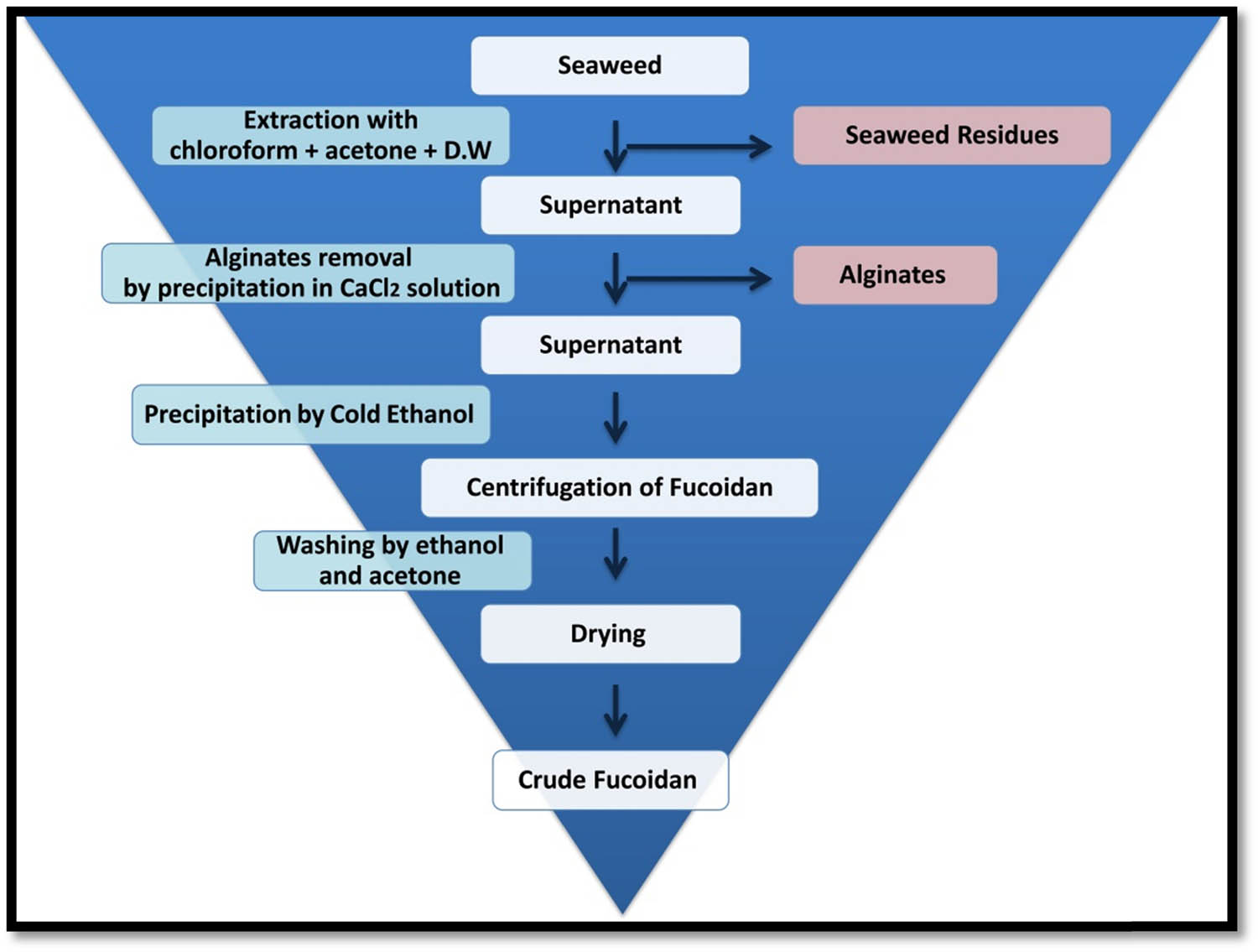

The Fu was extracted from C. barbata powder with hot water using slightly modified protocols [4,38]. Dried algae powder (10 g) was immersed in 100 mL of methanol–chloroform–DW (4:2:1) mixture and kept at 25 ± 2°C (room temperature; RT) overnight under occasional stirring to eliminate most of algal pigments, proteins, and lipids. After attaining the treated algae biomass by filtration and washing with DW, it was soaked in 500 mL of 0.1 M HCl at 85 ± 2°C for 125 min, then the supernatant was decanted, and the defatted biomass was washed by acetone and dried overnight. Subsequently, biomass was put in 500 mL of CaCl2 solution (1%, pH = 7) with mild stirring for 30 min, then at a constant state for 12 h at RT to precipitate alginate. The precipitated fraction was separated via centrifugation (Sigma 2–16 KL centrifuge; Sigma Lab. GmbH, Germany) at 8,500×g for 38 min at RT. The Fu in supernatant was precipitated by adding three volumes of ethanol (95%) and keeping at 4 ± 1°C overnight. Precipitated Fu was recovered via centrifugation (9,450×g) for 35 min, then Fu pellets were washed with ethanol and DW, frozen at −20°C, and lyophilized. A flowchart is illustrated (Figure A1 in Appendix) to display the step-by-step protocol used for Fu extraction.

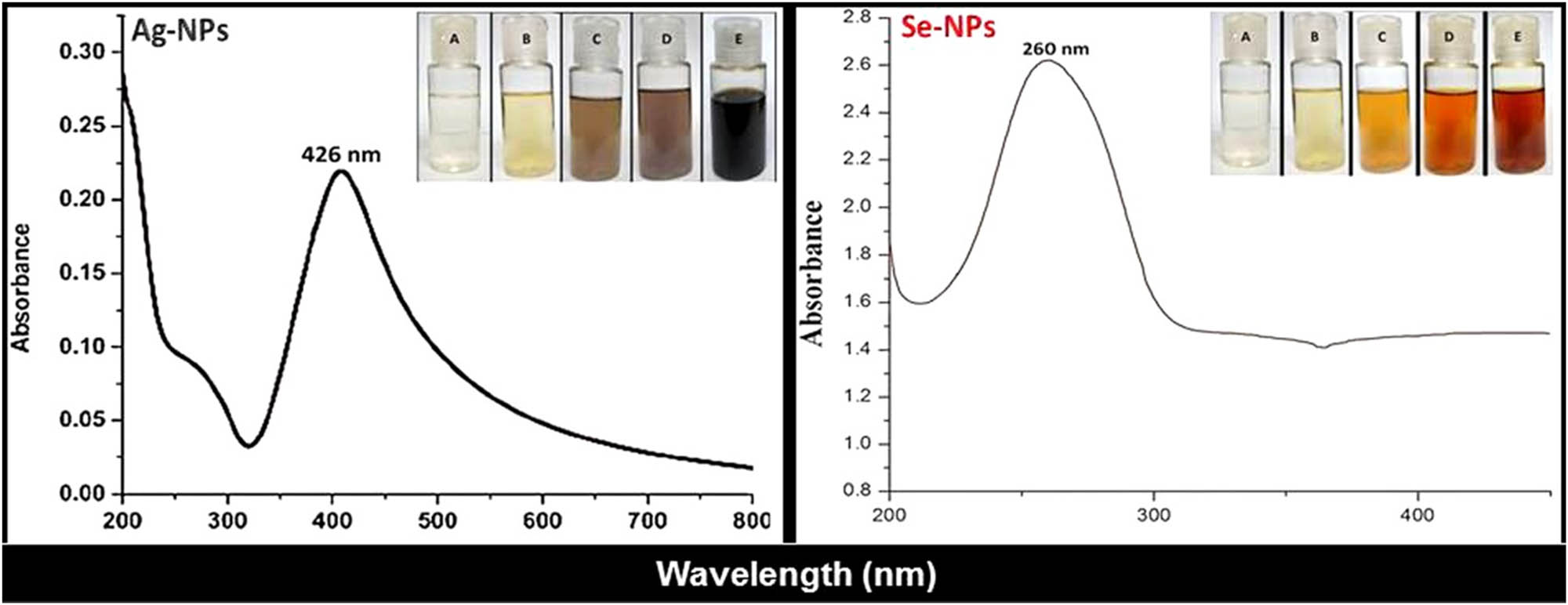

Visual appearance and UV-Vis spectra of Fu-synthesized Ag-NPs and Se-NPs. Photographs indicated NP solutions’ color after 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min of reaction for A, B, C, D, and E, respectively.

2.4 Fu compositional analysis

The Fu compositional analysis depended on numerous standardized methods to elucidate the proximate components in the produced biopolymer. The protein amount was measured by the Folin-phenol assay, operating bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard control [39]. The sulfate content of Fu was estimated using a standardized method [40], involving treatment of Fu solution with 1 M HCl solution, heating for 5 h at 110°C and then cooling. The mixture was treated with BaCl2-glutin reagent, and their adsorption was measured at 360 nm using a UV spectrophotometer. The uronic acid was calorimetrically assessed using a standard of galacturonic acid [41]. Total phenol/polyphenol contents were analyzed via Folin–Ciocalteu method, using a standard of gallic acid and absorbance measurement at 725 nm [42].

The monosaccharide contents/composition were determined via gas chromatography (Agilent 6890N, Agilent, USA) after complete hydrolyzation of samples (with trifluoroacetic acid) and conversion into aldononitrile-acetylated derivatives [43].

2.5 Synthesis and decoration of metal NPs of Ag-NPs and Se-NPs

For fabricating Ag-NPs and Se-NPs using Fu as a reducing/stabilizing agent, 10 mg of Fu was directly added and dissolved in 90 mL of 1 mM solution from AgNO3 [24], whereas for Se-NPs synthesis, 1% (w/v) of ascorbic acid, as a supplementary reducing agent, was dissolved in Na2SeO3 solution (1 mM) before adding Fu to this mixture [44]. The mixtures were stirred (430×g) for 33 min under heating (70 ± 2°C), with pH adjusted to 10–11 using KOH (0.1 M). The ion reductions to NPs were visually observed to inspect the color of solutions changing to blackish brown and reddish orange, respectively, for Ag-NP and Se-NP solutions. Subsequently, the NP-containing solutions were centrifuged (12,300×g for 25 min), and the harvested NP pellets were washed by DW, frozen overnight, and lyophilized.

2.6 Characterization of Ag-NPs and Se-NPs

The characterization of Ag-NPs and Se-NPs includes the following:

Applying UV-Vis spectroscopy (UV-2450 Shimadzu, Japan), the surface resonances of Fu-synthesized NPs (Se-NPs and Ag-NPs) were assessed at a wavelength range of 200–800 nm.

The structural and biochemical characteristics of extracted Fu and its composites with Ag-NPs and Se-NPs were screened using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; JASCO FTIR-360, Japan), at a wavenumber range of 450–4,000 cm−1, after the samples were mixed with KBr.

The distribution of NP size (Ps) and it’s zeta (ζ) potential was valued via dynamic light scattering (DLS; ZetaPlus, Brookhaven, USA).

NP ultrastructures were further screened via transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-100CX, JEOL Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) operated at accelerating of 80 kV.

2.7 Evaluation of NP anticandidal activity

The anticandidal potentialities of fabricated Fu-Ag NPs and Fu-Se NPs were evaluated toward different Candida sp. strains. Three yeast strains (i.e., C. albicans (ATCC 10231), C. glabrata (ATCC 90030), and C. parapsilosis (ATCC 201071)) were challenged in assessments; the yeasts were propagated and challenged using yeast-malt-dextrose-peptone (YM) agar and broth (HiMedia Lab., Mumbai, India) and incubated aerobically through experiments at 25 ± 2°C. The anticandidal assessments of NPs were conducted via different assays, mainly based on Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Standards [45]. Fluconazole (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Merck, Germany) was used as a positive standard antifungal agent, whereas DMSO solution was used as a negative control.

2.7.1 Inhibition zone (IZ) via disc diffusion (qualitative assay)

The appearance of free IZ from microbial growth, after challenging with assay discs carrying 30 µL of Fu-Ag NPs and Fu-Se NPs solutions (100 µg·mL−1 concentration), was used as qualitative assay, for example, disc diffusion method [46]. After streaking Candida sp. cells onto YM agar, sterile discs loaded with NPs were positioned on inoculants’ surfaces, and after incubation (18–24 h), the IZs appeared around discs were measured.

2.7.2 Determination of the minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) – quantitative assay

The microdilution technique (in 24-well microtiter plates, Sigma–Aldrich, MO) was applied for determining the anticandidal MFCs of Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs against examined Candida sp. [47]. The culture suspensions of Candida sp. (∼2 × 107 CFU·mL−1 of YM broth) were exposed to gradual concentrations from examined NP-lyophilized powders (at 0.1–100 µg·mL−1 concentration range). After incubation of microplates for 18–24 h, the less/nonturbid wells were treated with p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet (INT) chromogenic indicator (aqueous solution, 4% w/v), and then 100 µL from the nontransformed INT wells to reddish color was further plated onto YM agar plates and incubated. MFCs were quantified as least concentrations that prohibited the yeast growth in microtiter plates and on YM plates.

2.7.3 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging – morphological assay

For screening the apparent morphological alterations in Candida sp. cells, SEM imaging (JSM IT100, JEOL, Japan) was applied after exposure of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis cells to Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs in YM broth for gradual exposure duration (0, 5, and 10 h) [48]. Treated Candida cells were centrifuged (6,400×g for 25 min), washed with sterile NaCl solution (0.9%), dehydrated with gradual concentrations of ethanol, and coated with gold/palladium, and then SEM micrographs were taken to elucidate morphological alterations in yeast cells and their potential interactions with NPs.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Trials were triplicated; their means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated (Microsoft Excel 2010). Statistical significance calculation at p ≤ 0.05 was determined using one-way analysis of variance using MedCalc software V. 18.2.1 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium).

3 Results

3.1 Fu extraction from C. barbata

The chemical profile of C. barbata extract, used for Fu extraction, was first investigated to assess the suitability of this species for Fu production. The C. barbata extract’s components included high amounts of l-fucose, sulfates, and uronic acid (Table 1), which indicates the suitability of algal species and used extraction methods for Fu production.

Chemical profile of C. barbata extract used for Fu production

| Species | Extraction method | l-Fucose (mg·g−1) | Sulfate (mg·g−1) | Uronic acid (mg·g−1) | Protein (mg·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. barbata | Hot water | 64.2 ± 5.8 | 44.7 ± 4.4 | 78.2 ± 6.8 | 8.4 ± 1.3 |

3.2 Fu chemical characterization

The Fu yield and proximate monosaccharide contents are presented in Table 2. The yield of extracted Fu from C. barbata reached 55%. Additionally, the monosaccharides contained in C. barbata Fu included the highest levels of fucose, then galactose, xylose, mannose, and rhamnose, respectively.

Total yield, proximate composition, and monosaccharide composition of Fu isolated from C. barbata

| Sample | Proximate composition (%) | Monosaccharides (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (%) | Total sugar | Fucose | Galactose | Mannose | Rhamnose | Xylose | |

| Fu | 5.29 ± 0.48 | 55.04 ± 2.36 | 58.73 | 13.11 | 10.02 | 6.17 | 10.65 |

3.3 Characteristics of Fu-synthesized metal NPs

3.3.1 Optical analysis

The optical investigation of Fu-mediated NPs (Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs), via direct observation and UV-Vis spectrophotometric examination, confirms NP formation after Fu interactions (Figure 1). The direct observation of Fu/metal solutions indicated gradual transformation of color from clear appearance to deep blackish brown (for Fu/Ag-NPs) and reddish orange (for Fu/Se-NPs) within 30 min of reaction; no further color changes were observed after that. The highest NP-absorption peaks (λ max), via UV-vis analysis, were recorded at 260 and 426 nm for Fu/Se-NPs and Fu/Ag-NPs, respectively (Figure 1).

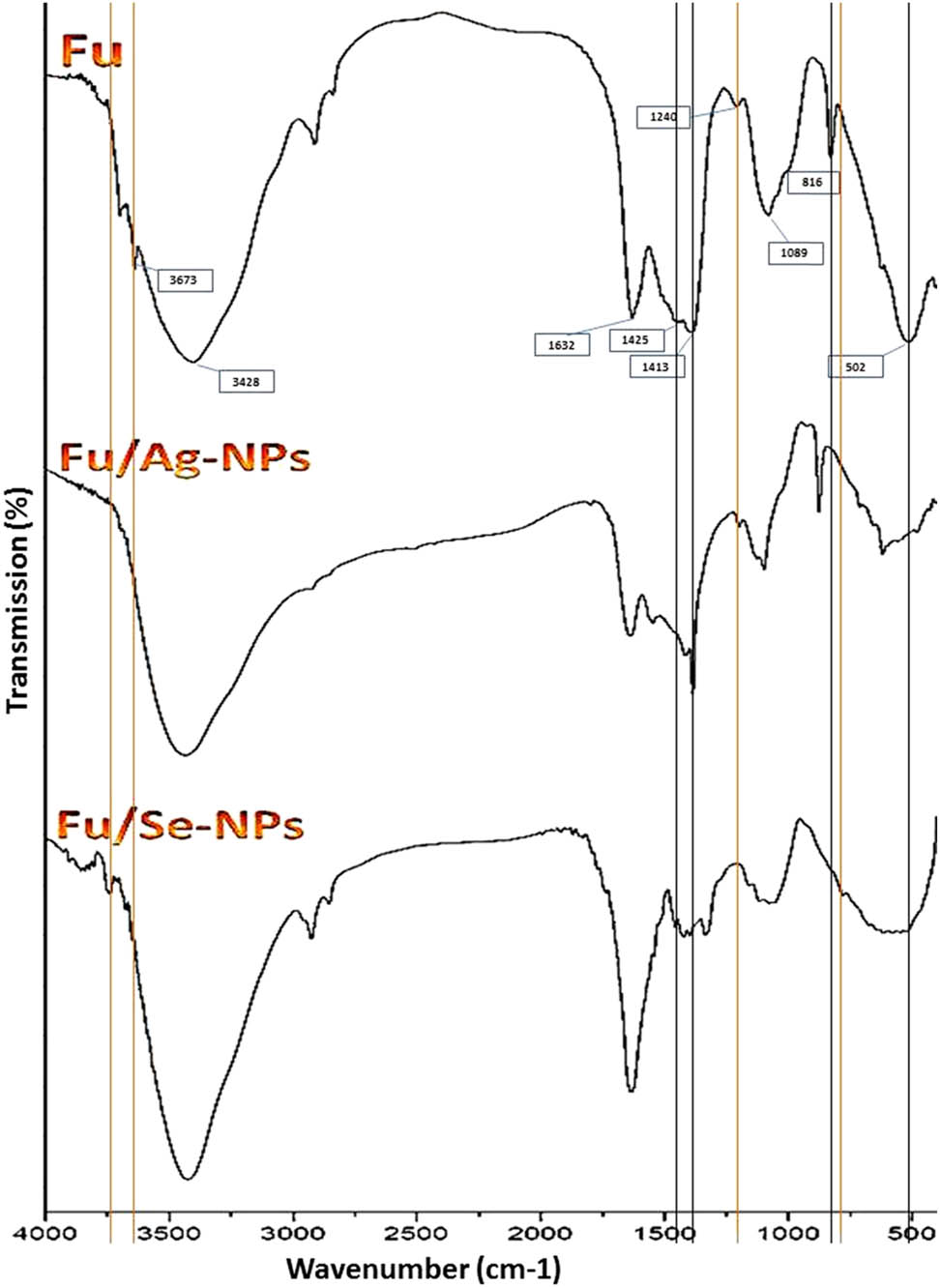

FTIR spectra of extracted Fu and polymer-decorated NPs of silver (Fu/Ag-NPs) and selenium (Fu/Se-NPs). The main influencing bands in Ag-NPs and Se-NPs synthesis are indicated by black and orange lines, respectively.

3.3.2 FTIR spectroscopy

The FTIR analysis of produced molecules (i.e., Fu and its composites with Ag-NPs and Se-NPs) was conducted to elucidate the molecular biochemical bonding and the interactions between composited agents and the potential Fu groups responsible for NP synthesis. The extracted Fu from C. barbata had the key characteristic features of accustomed Fu biopolymers, as proved from its detected biochemical bonding via FTIR analysis (Figure 2). The FTIR spectrum of Fu (Fu in Figure 2) designated the presence of functional sulfated groups/ponds in the Fu structure and their detectable levels.

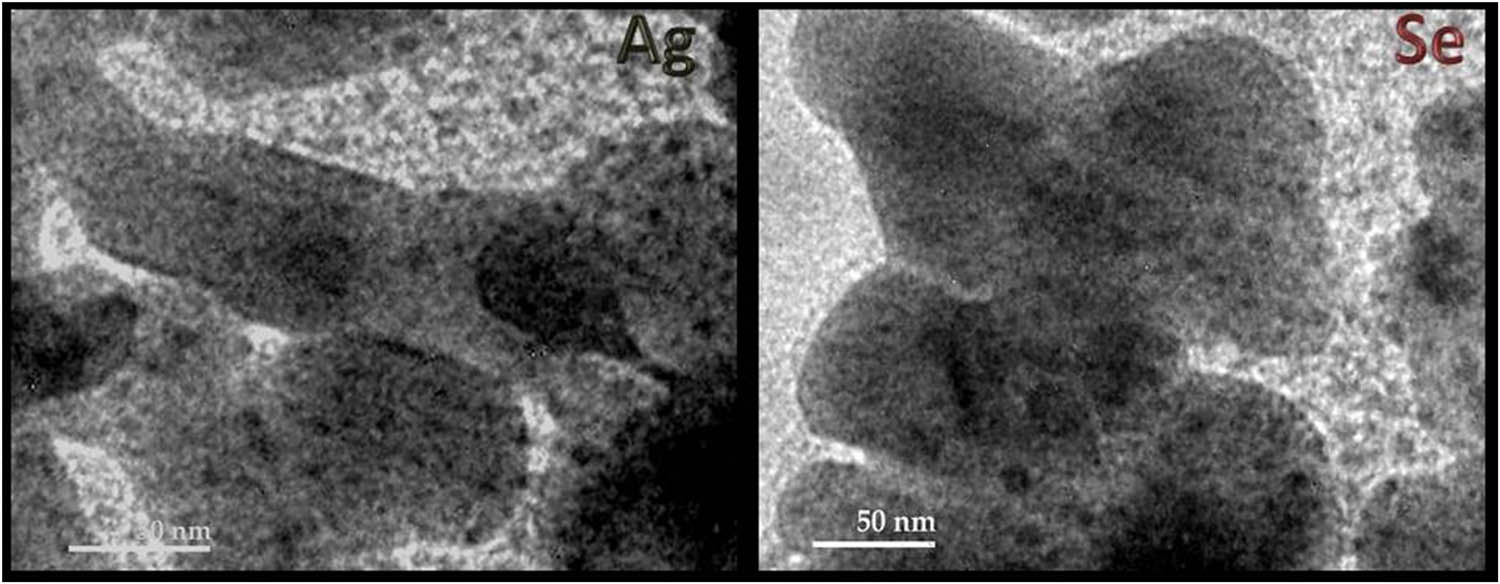

TEM imaging of Fu-synthesized Ag-NPs and Se-NPs.

For the Fu-synthesized Ag-NP spectrum (Fu/Ag-NPs in Figure 2), the composite had the main distinctive peaks of Fu. The varied peaks from the Fu spectrum could indicate the potential responsible bonds/groups for Ag-NP synthesis. Comparing to the Fu FTIR spectrum, the band at 1425.44 cm−1 was shifted to 1385.41 cm−1, which indicates the potential transformation of C–C stretching of aromatics to C–H alkenes stretching after compositing with Ag-NPs.

The FTIR spectrum of Fu-synthesized Se-NPs (Fu/Se-NPs in Figure 2) also had the main characteristic peaks of the Fu spectrum; the novel altered bands in the Fu spectrum due to Se-NPs synthesis/interaction were the new band at 3748.21 cm−1 that may designate the Se-NPs binding to –OH groups and other function groups of Fu.

3.3.3 Size and charge of NPs

The DLS of produced NPs (Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs) indicated that Fu could effectually reduce both metal ions to NPs form, with minute Ps ranges and means (Table 3). The Ps means of synthesized NPs were 12.86 and 16.18 nm for Ag-NPs and Se-NPs, respectively. The Fu-synthesized NPs exhibited persuasive negative ζ potentialities of −35.8 and −34.7 mV for Ag-NPs and Se-NPs, respectively.

Particle size (Ps) distribution and ζ potential of Fu-synthesized Ag-NPs and Se-NPs

| Nanoparticles | Ps range (nm) | Mean diameter (nm) | Median (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu/Ag-NPs | 3.82–36.44 | 12.86 | 12.04 | −35.8 |

| Fu/Se-NPs | 5.27–43.54 | 16.18 | 15.84 | −34.7 |

3.3.4 TEM imaging

The TEM imaging of Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs was used for inspecting the shapes, sizes, and surface morphologies of the composited nanocomposites. The TEM images (Figure 3) indicated that both Fu synthesized and decorated nanometals had mostly spherical shapes and good distribution within the biopolymer matrix. Many NPs were embedded in Fu as combined clusters; the estimated Ps average diameters were ∼12.13 nm for Ag-NPs and ∼15.54 nm for Se-NPs. These results matched the acquired data by DLS measurements of corresponding Ps distributions (Table 3).

Consequences of exposing Candida sp. (C. albicans and C. parapsilosis) to Fu/Se-NPs (S) and Fu/Ag-NPs (A) on morphological attributes of cells after exposure for 0, 5, and 10 h.

3.4 Anticandidal activity of Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs

The anticandidal assays of Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs were performed against C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. parapsilosis to designate the potentialities of NPs to inhibit Candida sp. (Table 4). Although the negative control (DMSO solution) did not exhibit any anticandidal activity, both NPs displayed potent antimycotic potentialities toward the entire challenged strains. The differences between the IZ results were nonsignificant either for the tested NP activities or between their individual activities toward each strain. Promisingly, no significant differences also were recorded between the standard antifungal (fluconazole) and any of screened NPs.

Anticandidal potentialities of Fu-synthesized NPs (Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs) against pathogenic Candida sp.

| Examined agent | Anticandidal activity* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | C. glabrata | C. parapsilosis | ||||

| IZ* (mm) | MFC (µg·mL−1) | IZ (mm) | MFC (µg·mL−1) | IZ (mm) | MFC (µg·mL−1) | |

| Fu/Ag-NPs | 13.5 ± 1.4 | 25.0 | 13.7 ± 1.5 | 25.0 | 15.6 ± 1.7 | 17.5 |

| Fu/Se-NPs | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 30.0 | 12.9 ± 1.1 | 27.5 | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 22.5 |

| Fluconazole | 14.5 ± 1.6 | 25.0 | 15.1 ± 1.7 | 22.5 | 16.2 ± 1.8 | 17.5 |

*IZs represent means of triplicates ± SD, including assay disc diameter (6 mm), which were loaded with 100 µg from NPs and 25 µg of standard drug.

In general, C. albicans showed the highest resistance among challenged strains, whereas C. parapsilosis was the most sensitive strain, regarding their IZs and MFC values.

The potential anticandidal actions of Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs toward Candida sp. (C. albicans and C. parapsilosis) were investigated via SEM imaging (Figure 4). In the beginning of exposure (S0 and A0 in Figure 4), both yeast cells appeared with smooth and healthy features, some NPs appeared in attachment with cell surfaces in this first stage. After exposure to NPs for 5 h (S5 and A5 in Figure 4), notable distortions appeared in cell morphology; the effects of Fu/Ag-NPs were more vigorous than Fu/Se-NPs to distort Candida cells. Noticeable bores were formed in cell surfaces after exposure to Ag-NPs, whereas the cells enlarged and buffed after Se-NP exposure. By extension the NP exposure up to 10 h (S10 and A10 in Figure 4), the yeast cells were mostly lysed/deformed and vigorously distorted, the bores clearly appeared in Se-NPs exposed cells, whereas the Ag-NP-exposed cells were utterly deformed and distorted. The NP effects were apparently more vigorous and evidenced in C. parapsilosis cells than in C. albicans cells.

4 Discussion

The Fu was extracted from C. barbata extract; the extract analysis results match a preceding investigation that recommended the usage of hot water extraction to attain the highest percentages from l-fucose and uronic acid, during Fu extraction, compared to salt extraction procedure [3]. The elevated contents of sulfated monosaccharide (e.g., fucose) in isolated Fu from brown algae species were documented, which are chiefly responsible for Fu bioactivities and interactions [5,8,49,50]. Moreover, the obtained percentages here of Fu monosaccharides and yield are comparable with extracted Fu from other algal species, including Ecklonia maxima, Laminaria pallida, Splachnidium rugosum, Padina tetrastromatica, Fucus vesiculosus, numerous Fucus sp., and Sargassum sp. [2,6,51].

The color changes of NP-containing solutions are principally correlated with the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) excitation of synthesized NPs, the deepness of solution color is indicative of size of the formed NPs [14,23]. The obtained λ max values for Fu/Se-NPs and Fu/Ag-NPs are in accordance with those of phycosynthesized Ag-NPs and Se-NPs with algal derivatives and the incorporated NPs with biopolymers and algal polysaccharides [16,23,24,25,31].

The main distinctive peaks in FTIR spectrum of Fu were detected at 501.89 cm−1 (sulfated C–O–S at C-4 of fucopyranose); 1088.97 cm−1 (O═S═O symmetric vibration in sulfate esters); 1240.42 cm−1 (CH3 in fucose and O-acetyls); 1425.44 and 1413.31 cm−1 (CH2 in galactose and xylose); 1632.42 cm−1 (stretched C–O vibration of O acetyl); and 3428.11 cm−1 (indicates stretched O–H group) [9,52,53,54]. The intense signal at ∼1,089 cm−1 indicated the strong stretched vibrations of sulfoxide (S═O), which evidences the significant amount of sulfate groups in the extracted Fu [55,56]. In the Fu-synthesized Ag-NP spectrum (Fu/Ag-NPs in Figure 2), the sulfate peak (at 816.23 cm−1) was also shifted to 873.15 cm−1 in the Fu/Ag-NPs, which is assumingly attributed to the sulfate group involvement in the Ag-NP synthesis [5,6]. Additionally, the differed bands from the Fu spectrum included the band at 501.89 cm−1 (C–O–S) that became less intense and shifted to 494.31 cm−1 and the band at 1413.31 cm−1 (CH2) that became sharper and has increased intensity. These changes are mostly due to Ag ion reduction into Ag-NPs and interactions with the formed NPs [24]. For the FTIR spectrum of Fu-synthesized Se-NPs (Fu/Se-NPs in Figure 2), the emerged/altered band from the Fu spectrum indicated the responsible groups/bonds for Se-NP synthesis. The Fu band at 1240.42 cm−1 (CH3) was disappeared and the band at 3673.21 cm−1 was vanished in Fu/Se-NPs spectrum, indicating Se-NPs interactions with Fu biochemical groups. A novel band at 771.48 cm−1 was also emerged in the Fu/Se-NPs spectrum, which is assumingly attributed to Se-NP conjugation with Se–O and/or –OH groups of Fu [57,58].

Compared to Ps of synthesized Ag-NPs using Fus of F. evanescens and Saccharina cichorioides (64 and 53 nm, respectively) [24], and from Spatoglossum asperum (20–46 nm) [22], the used Fu here from C. barbata exhibited a stronger reducing activity, which enabled the generation of lesser size Ag-NPs. Furthermore, the achieved miniature Ps of Fu-mediated Se-NPs, as innovative results, validated the high potentiality of C. barbata for reducing/decorating metal NPs [23].

The ζ potential can precisely indicate the surface charge of individual molecules and additionally can measure the formed electric dual layer by adjoining ions in solution; regularly, NPs with ζ values of ≥+30 mV or ≤−30 mV possess high stability due to electrostatic inter-particle repulsion [59]. The elevated ζ potentials of Fu-synthesized NPs indicate the capability of Fu biopolymer for stabilizing metal NPs. Harmonized results for ζ potential of Fu-synthesized Ag-NPs were reported with negativity up to −36 mV [26] and in −27 to −30 mV range [24].

The acquired results from TEM and DLS analysis of Fu-synthesized NPs validated the potentiality of Fu in reducing/stabilizing NPs. Recent studies indicated matched shapes and combinations of Fu-synthesized Ag-NPs [24]; the NPs had oval/spherical and good distribution attributes. As a main goal of this study was to achieve effectual nanometals with reduced toxicity to human cells, the decoration/embedding of synthesized NPs within the Fu matrix could assist to reach this target. The amalgamation of nanometals into biopolymers composites was significantly appointed to augment their stabilization, generate additional bioactivity via conjugation with biomolecules, enhance metal NPs biocompatibility, and accordingly diminish their humanoid cytotoxicity [16,23,60,61,62]. Accordingly, the synthesized/capped NPs with Fu are assumed to possess elevated biosafety and nontoxicity. Since no cytotoxicity assays were conducted in the present study, further biotoxicity examinations are recommended to confirm the expected biosafety of Fu-synthesized NPs.

The anticandidal activities of each NPs (Ag-NPs and Se-NPs) were formerly indicated from many investigations [13,28,30,33]. The anticandidal potentiality of Se-NPs was illustrated to correlate with Ps of NPs; the lesser sizes provided higher activity [32,37]. The Se-NPs (at 70–300 nm size range) that conjugated with biopolymers (e.g., chitosan and BSA) exhibited potent antimycotic activity against C. albicans, with an minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 25 µg·mL−1, which exceeded the anticandidal activity of plain Se-NPs that had an MIC of 400 µg·mL−1 [33]. Regarding Ag-NP anticandidal activity, the investigations indicated their powerful action to destroy yeast cells and hinder their metabolic activities, mainly due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, which influences the microbial cell activity [10,30].

The incorporation of NPs (Ag-NPs and Se-NPs) into biopolymer matrix/composite was reported to stimulate their anticandidal activities [28,33,34,61]; this was attributed to NPs stabilization and good distribution within the polymer matrix and the ability of a loaded polymer to adhere to yeast cells, which facilitates NP interaction with the cell membranes. Additionally, the reduced/stabilized Ag-NPs using Fu from F. vesiculosus, in microwave-assisted procedure, had strong antibacterial actions (mainly due to leakage of intracellular proteins and ROS oxidative stress), which were attributed to Fu/Ag-NP binding and interaction with microbial cells [12]. The antimicrobial activities (antibacterial and antimycotic) of Fu were also reported against oral pathogens [7], where they suggested that Fu antimicrobial properties are based on its structures, for example, sugar chains’ branching and sulfate groups number, the extraction procedure, and the capability of such sulfated polysaccharides to bind with proteins and further cellular molecules.

Accordingly, the conjugation/decoration of synthesized NPs within Fu matrix is strongly suggested to augment their combined anticandidal actions, as the Fu can effectually bind to surface of the cells and enable attachment/interaction of NPs with cell membranes and interior vital components.

The exposed Candida sp. (i.e., C. albicans and C. parapsilosis) were chosen for SEM analysis because they exhibited the most resistant and sensitive patterns, respectively, toward NPs in previous experiments (antimycotic assays). Thus, it was assumed from their analysis to provide potential mechanisms of NP anticandidal actions. The proposed antimicrobial actions of metal NPs were suggested to depend on their potentiality for ROS generation, their interactions with cells barriers (leading to deformation and disruption of cell walls), affecting the permeability of cell membranes, inhibition of DNA and protein synthesis, and suppression of metabolic regulation genes [10,11,63]. The generated ROS from metal NPs could additionally interfere/inhibit amino acid construction and DNA replication and could seriously lead to cell membrane damage [10]. The integration of Se-NPs with biopolymer matrix (e.g., chitosan) provided more forceful anticandidal action toward C. albicans, which triggered the formation of destructive bores in yeast membranes [28,34]. This action surpassed the plain Se-NPs anticandidal action [32], which supposed that NPs incorporation/stabilization with biopolymers (Fu in current study) can augment the bioactivity and action of the composite. The Ag-NPs were also reported to possess potent anticandidal actions via interference with Candida sp. membranes and interior components, and pore formation in such membranes, which led to lysis and death of mycotic cells [13].

As the forcefulness of NP antimicrobial potentiality is simultaneous and involves multiple mechanisms, even antimicrobial-resistant microbes could not acquire the resistances to such action mechanisms, which is considered as main advantages of NPs as microbicidal agents, contrary to customary antibiotics [33]. However, the conjugation of NPs with biopolymers, for example, Fu, could elevate their biosafety for practical applications in human practices, for example, pharmaceutical drugs, skin care, antiseptic wash, or topical formulations [62].

5 Conclusion

The Fu was extracted from C. barbata algae and was innovatively and effectually used for the green synthesis of metal NPs (Ag-NPs and Se-NPs) via the facile protocol. The synthesized Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs had favorable characteristics, for example, mean Ps of 12.86 and 16.18 nm, respectively, elevated ζ potential negativity, and good distribution within the Fu matrix. The anticandidal actions of Fu-synthesized NPs were proved against many Candida sp. via qualitative and quantitative assays and by ultrastructure imaging. The potentialities of Fu/Ag-NPs and Fu/Se-NPs as powerful anticandidal agents with minimized toxicity for human tissues could enable their future applications in practical formulations for controlling pathogenic Candida sp. Further investigations can be suggested for confirming the biosafety of generated nanocomposites and their activities against other pathogenic microbes.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deep gratitude for the mercy guidance and help from ALLAH. The appreciation is indebted to Central Lap for Aquatic Health and Safety – Kafrelsheikh University, for supporting and providing the essential facilities for the study.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Mousa Alghuthaymi: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, resources, formal analysis, and writing – original draft; Zainab El-Sersy: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, and writing – original draft; Ahmed Tayel: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing – original draft, writing – review and editing; Mohammed Alsieni: resources, visualization, and formal analysis; Ahmed Abd El Maksoud: conceptualization, supervision, investigation, validation, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Appendix

Schematic flowchart illustrated the step-by-step protocol used for Fu extraction from C. barbata.

References

[1] Cunha L, Grenha A. Sulfated seaweed polysaccharides as multifunctional materials in drug delivery applications. Mar Drugs. 2016;14(3):42. 10.3390/md14030042.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Zhang R, Zhang X, Tang Y, Mao J. Composition, isolation, purification and biological activities of Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharides: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;228:115381. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115381.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] January GG, Naidoo RK, Kirby-McCullough B, Bauer R. Assessing methodologies for fucoidan extraction from South African brown algae. Algal Res. 2019;40:101517. 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101517.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Lee JB, Hayashi K, Hashimoto M, Nakano T, Hayashi T. Novel antiviral fucoidan from sporophyll of Undaria pinnatifida (Mekabu). Chem Pharm Bull. 2004;52(9):1091–4. 10.1248/cpb.52.1091.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Palanisamy S, Vinosha M, Marudhupandi T, Rajasekar P, Prabhu NM. In vitro antioxidant and antibacterial activity of sulfated polysaccharides isolated from Spatoglossum asperum. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;44:296–304. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.085.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Palanisamy S, Vinosha M, Marudhupandi T, Rajasekar P, Prabhu NM. Isolation of fucoidan from Sargassum polycystum brown algae: structural characterization, in vitro antioxidant and anticancer activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;102:405–12. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.182.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Oka S, Okabe M, Tsubura S, Mikami M, Imai A. Properties of fucoidans beneficial to oral healthcare. Odontology. 2020;108(1):34–42. 10.1007/s10266-019-00437-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Pozharitskaya ON, Obluchinskaya ED, Shikov AN. Mechanisms of bioactivities of fucoidan from the brown seaweed Fucus vesiculosus L. of the Barents Sea. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(5):275. 10.3390/md18050275.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Somasundaram SN, Shanmugam S, Subramanian B, Jaganathan R. Cytotoxic effect of fucoidan extracted from Sargassum cinereum on colon cancer cell line HCT-15. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;91:1215–23. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.06.084.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Hemeg H. Nanomaterials for alternative antibacterial therapy. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:8211–25. 10.2147/IJN.S132163.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Eleraky NE, Allam A, Hassan SB, Omar MM. Nanomedicine fight against antibacterial resistance: an overview of the recent pharmaceutical innovations. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:142. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12020142.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Rao SS, Saptami K, Venkatesan J, Rekha PD. Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of silver nanoparticles using fucoidan: characterization with assessment of biocompatibility and antimicrobial activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163:745–55. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.230.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Jalal M, Ansari MA, Alzohairy MA, Ali SG, Khan HM, Almatroudi A, et al. Anticandidal activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles: effect on growth, cell morphology, and key virulence attributes of Candida species. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:4667–79. 10.2147/IJN.S210449.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Faramarzi S, Anzabi Y, Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H. Nanobiotechnology approach in intracellular selenium nanoparticle synthesis using Saccharomyces cerevisiae – fabrication and characterization. Arch Microbiol. 2020;202:1203–9. 10.1007/s00203-020-01831-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Al-Saggaf MS, Tayel AA, Ghobashy MOI, Alotaibi MA, Alghuthaymi MA, Moussa SH. Phytosynthesis of Selenium nanoparticles using costus extract for bactericidal application against foodborne pathogens. Green Process Synth. 2020;9:477–87. 10.1515/gps-2020-0038.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Elnagar SE, Tayel AA, Elguindy NM, Al-saggaf MS, Moussa SH. Innovative biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using yeast glucan nanopolymer and their potentiality as antibacterial composite. J Basic Microbiol. 2021;2021:1–9. 10.1002/jobm.202100195.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] El-Baz AF, El-Batal AI, Abomosalam FM, Tayel AA, Shetaia YM, Yang ST. Extracellular biosynthesis of anti-candida silver nanoparticles using Monascus purpureus. J Basic Microbiol. 2016;56:531–40. 10.1002/jobm.201500503.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Abeer Mohammed AB, Al-Saman MA, Tayel AA. Antibacterial activity of fusion from biosynthesized acidocin/silver nanoparticles and its application for eggshell decontamination. J Basic Microbiol. 2017;57(9):744–51. 10.1002/jobm.201700192.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Al-Saggaf MS, Tayel AA, Alghuthaymi MA, Moussa SH. Synergistic antimicrobial action of phyco-synthesized silver nanoparticles and nano-fungal chitosan composites against drug resistant bacterial pathogens. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2020;34:631–9. 10.1080/13102818.2020.1796787.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Alsaggaf MS, Diab AM, ElSaied BEF, Tayel AA, Moussa SH. Application of ZnO nanoparticles phycosynthesized with Ulva fasciata extract for preserving peeled shrimp quality. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:385. 10.3390/nano11020385.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Alghuthaymi M, Diab A, Elzahy A, Mazrou K, Tayel AA, Moussa SH. Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan. J Food Qual. 2021;2021:6670709-6. 10.1155/2021/6670709.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Ravichandran A, Subramanian P, Manoharan V, Muthu T, Periyannan R, Thangapandi M, et al. Phyto-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using fucoidan isolated from Spatoglossum asperum and assessment of antibacterial activities. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;185:117–25. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.05.031.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Khanna P, Kaur A, Goyal D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications. J Microbiol Methods. 2019;163:105656. 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.105656.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Yugay YA, Usoltseva RV, Silant'ev VE, Egorova AE, Karabtsov AA, Kumeiko VV, et al. Synthesis of bioactive silver nanoparticles using alginate, fucoidan and laminaran from brown algae as a reducing and stabilizing agent. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;245:116547. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116547.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] ElSaied BE, Diab AM, Tayel AA, Alghuthaymi MA, Moussa SH. Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract. Green Process Synth. 2021;10(1):49–60. 10.1515/gps-2021-0005.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Venkatesan J, Singh SK, Anil S, Kim SK, Shim MS. Preparation, characterization and biological applications of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles with chitosan-fucoidan coating. Molecules. 2018;23:1429–30. 10.1155/2015/829526.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Alwhibi MS, Soliman DA, Awad MA, Alangery AB, Al Dehaish H, Alwasel YA. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: characterization and its potential biomedical applications. Green Process Synth. 2021;10(1):412–20. 10.1515/gps-2021-0039.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Kulatunga DCM, Dananjaya SHS, Godahewa GI, Lee J, De Zoysa M. Chitosan silver nanocomposite (CAgNC) as an antifungal agent against Candida albicans. Med Mycol. 2017;55(2):213–22. 10.1093/mmy/myw053.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Muthamil S, Devi VA, Balasubramaniam B, Balamurugan K, Pandian SK. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles demonstrating enhanced in vitro and in vivo antibiofilm activity against Candida spp. J Basic Microbiol. 2018;58(4):343–57. 10.1002/jobm.201700529.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Khatoon N, Sharma Y, Sardar M, Manzoor N. Mode of action and anti-Candida activity of Artemisia annua mediated-synthesized silver nanoparticles. J Mycol Med. 2019;29(3):201–9. 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.07.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Shi XD, Tian YQ, Wu JL, Wang SY. Synthesis, characterization, and biological activity of selenium nanoparticles conjugated with polysaccharides. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;61:2225–36. 10.1080/10408398.2020.1774497.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Rasouli M. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using yeast Nematospora coryli and examination of their anti-candida and anti-oxidant activities. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2019;13(2):214–8. 10.1049/iet-nbt.2018.5187.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Filipović N, Ušjak D, Milenković MT, Zheng K, Liverani L, Boccaccini AR, et al. Comparative study of the antimicrobial activity of selenium nanoparticles with different surface chemistry and structure. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;8:1591. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.624621.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Lara HH, Guisbiers G, Mendoza J, Mimun LC, Vincent BA, Lopez-Ribot JL, et al. Synergistic antifungal effect of chitosan stabilized selenium nanoparticles synthesized by pulsed laser ablation in liquids against Candida albicans biofilms. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:2697–708. 10.2147/IJN.S151285.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Friedman DZP, Schwartz IS. Emerging fungal infections: new patients, new patterns, and new pathogens. J Fungi. 2019;5:67. 10.3390/jof5030067.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Ciurea CN, Kosovski IB, Mare AD, Toma F, Pintea-Simon IA, Man A. Candida and Candidiasis – Opportunism versus pathogenicity: a review of the virulence traits. Microorganisms. 2020;8(6):857. 10.3390/microorganisms8060857.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Shakibaei M, Salari Mohazab N, Ayatollahi Mousavi SA. Antifungal activity of selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Bacillus species Msh-1 against Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans’. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2015;8(9):e26381. 10.5812/jjm.26381.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Mak W, Hamid N, Liu T, Lu J, White WL. Fucoidan from New Zealand Undaria pinnatifida: monthly variations and determination of antioxidant activities. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;95(1):606–14. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.02.047.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Winters AL, Minchin FR. Modification of the Lowry assay to measure proteins and phenols in covalently bound complexes. Anal Biochem. 2005;346(1):43–8. 10.1016/j.ab.2005.07.041.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Dodgson KS, Price RG. A note on the determination of the ester sulphate content of sulphated polysaccharides. Biochem J. 1962;84(1):106–10. 10.1042/bj0840106.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Filisetti-Cozzi TMCC, Carpita NC. Measurement of uronic acids without interference from neutral sugars. Anal Biochem. 1991;197(1):157–62. 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90372-Z.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Chandler SF, Dodds JH. The effect of phosphate, nitrogen and sucrose on the production of phenolics and solasodine in callus cultures of Solanum laciniatum. Plant Cell Rep. 1983;2(4):205–8. 10.1007/BF00270105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Zha XQ, Lu CQ, Cui SH, Pan LH, Zhang HL, Wang JH, et al. Structural identification and immunostimulating activity of a Laminaria japonica polysaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;78:429–38. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.04.047.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Song C, Li X, Wang S, Meng Q. Enhanced conversion and stability of biosynthetic selenium nanoparticles using fetal bovine serum. RSC Adv. 2016;6(106):103948–54. 10.1039/C6RA22747C.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 29th edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2019. CLSI supplement M100.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Tayel AA, El-Tras WF, Moussa S, El-Baz AF, Mahrous H, Salem MF, et al. Antibacterial action of zinc oxide nanoparticles against foodborne pathogens. J Food Saf. 2011;31:211–8. 10.1111/j.1745-4565.2010.00287.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Tayel AA, Moussa S, Opwis K, Knittel D, Schollmeyer E, Nickisch-Hartfiel A. Inhibition of microbial pathogens by fungal chitosan. Int J Biol Macromol. 2010;47(1):10–4.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.04.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Marrie TJ, Costerton JW. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy of in situ bacterial colonization of intravenous and intraarterial catheters. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19(5):687–93. 10.1128/jcm.19.5.687-693.1984.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Serafini M, Peluso I, Raguzzini A. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69(3):273–8. 10.1007/s00011-009-0037-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Widjanarko SB, Soehono LA. Extraction optimization by response surface methodology and characterization of fucoidan from brown seaweed Sargassum polycystum. Int J Chemtech Res. 2014;6:195–205.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Kartik A, Akhil D, Lakshmi D, Gopinath KP, Arun J, Sivaramakrishnan R, et al. A critical review on production of biopolymers from algae biomass and their applications. Bioresour Technol. 2021;2021:124868. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Synytsya A, Kim WJ, Kim SM, Pohl R, Synytsya A, Kvasnička F, et al. Structure and antitumour activity of fucoidan isolated from sporophyll of Korean brown seaweed Undaria Pinnatifida. Carbohydr Polym. 2010;81:41–8. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.01.052.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Gomez-Ordonoz E, Ruperez P. FT–IR–ATR spectroscopy as a tool for polysaccharide identification in edible brown and red seaweed. Food Hydrocolloids. 2011;25:1514–20. 10.1016/J.FOODHYD.2011.02.009.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Immanuel G, Sivagnanavelmurugan M, Marudhupandi T, Radhakrishnan S, Palavesam A. The effect of fucoidan from brown seaweed Sargassum wightii on WSSV resistance and immune activity in shrimp Penaeus monodon (Fab). Fish Fishshell Immunol. 2012;32:551–64. 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.01.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Kim WJ, Koo YK, Jung KM, Moon RH, Kim SM, Synytsya A. Anticoagulating activities of low-molecular weight fuco-oligosaccharide prepared by enzymatic digestion of fucoidan from the sporophyll of Korean Undaria pinnatifida. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:125–31. 10.1007/s12272-010-2234-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Silverstein RM, Webster FX. Spectrometric identification of organic compounds. 6th edn. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] El-Batal AI, El-Sayyad GS, El-Ghamry A, Agaypi KM, Elsayed MA, Gobara M. Melanin-gamma rays assistants for bismuth oxide nanoparticles synthesis at room temperature for enhancing antimicrobial, and photocatalytic activity. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2017;173:120–39. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.05.030.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Ashour AH, El-Batal AI, Maksoud MIAA, El-Sayyad GS, Labib S, Abdeltwab E, et al. Antimicrobial activity of metal-substituted cobalt ferrite nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel technique. Particuology. 2018;40:141–51. 10.1016/j.partic.2017.12.001 Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Skoglund S, Hedberg J, Yunda E, Godymchuk A, Blomberg E, Odnevall Wallinder I. Difficulties and flaws in performing accurate determinations of zeta potentials of metal nanoparticles in complex solutions – four case studies. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181735. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181735.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] Saravanakumar G, Jo DG, Park JH. Polysaccharide-based nanoparticles: a versatile platform for drug delivery and biomedical imaging. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(19):3212–29. 10.2174/092986712800784658.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Zienkiewicz-Strzałka M, Deryło-Marczewska A. Small AgNP in the biopolymer nanocomposite system. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:9388. 10.3390/ijms21249388.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Długosz O, Szostak K, Staroń A, Pulit-Prociak J, Banach M. Methods for reducing the toxicity of metal and metal oxide NPs as biomedicine. Materials. 2020;13:279. 10.3390/ma13020279.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Wang L, Hu C, Shao L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:1227–49. 10.2147/IJN.S121956.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2021 Mousa A. Alghuthaymi et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis