Abstract

Hemicellulose is a carbohydrate biopolymer second only to cellulose, which is rich and has a broad application prospect. The limitation of high-value utilization of hemicellulose has been a long-standing challenge due to its complex and diversified structure. The extraction and subsequent modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass represent a promising pathway toward this goal. Herein, the extraction processes including physical pretreatment, chemical pretreatment, and combined pretreatment for separating hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass were introduced, and the advantages and disadvantages of various extraction procedures were also described. The chemical modification of hemicellulose such as etherification, esterification, grafting, and cross-linking modification was reviewed in detail. The separation and modification of hemicellulose in the future are prospected based on the earlier studies.

1 Introduction

Fossil resources have been overexploited for a long time with the development of industries and the growth of population, leading to the continuous deterioration of the environment and the increasing shortage in energy. It has become a bottleneck restricting the sustainable development of human society. Therefore, it is extremely necessary to develop new nonpolluting energy with low price, safety, and sustainable utilization. Lignocellulosic biomass, with a reserve of about 1,800 billion tons, is the most abundant renewable resource on the earth. It is equivalent to 64 billion tons of petroleum and is considered a promising alternative to fossil resources [1]. The conversion of lignocellulosic biomass is essential to make it an available energy source. Different methods such as pretreatment and biorefinery [2] have been developed to improve biomass utilization efficiency [3,4].

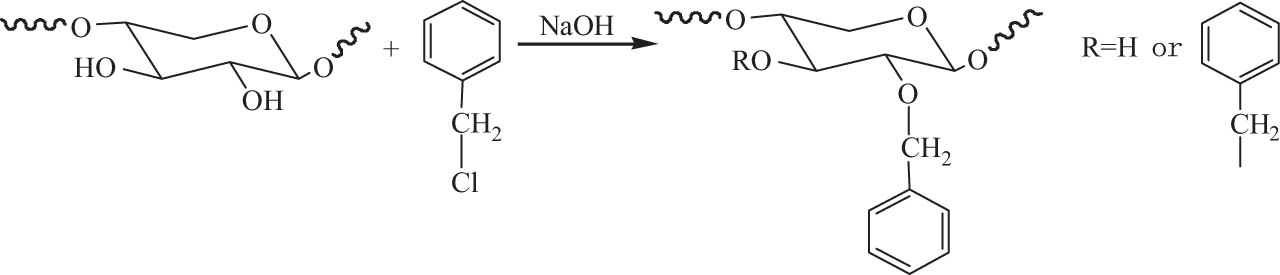

Cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin constitute the main part of plant cell walls of lignocellulosic biomass, among which hemicellulose is a natural carbohydrate biopolymer second only to cellulose, accounting for about 20–30 wt%. Hemicellulose is a complex branched heteropolymer composed of pentoses (β-d-xylose and α-l-arabinose), hexoses (β-d-mannose, β-d-glucose, and β-d-galactose), glucuronic acid, a small amount of l-rhamnose and l-fucose units, and the most abundant hemicellulosic polymers are xylans [5]. The content and structure of hemicellulose, the length and type of the main chain, and the distribution and type of side chains vary with the species of lignocellulose. The common sugar-based structures of hemicellulose are shown in Scheme 1 [6].

Hemicellulose and its several common sugar-based structures.

Hemicellulose is a renewable, biodegradable, and environmentally friendly biomass resource with special physical and chemical properties, including high molecular weight, nonionic, and nontoxic. It is expected to be widely applied in packaging, food, pharmaceutical, biomedicine, cosmetic, textile, and papermaking industries [7]. The application of hemicellulose has attracted increasing attention with the increasing scarcity of fossil resources. However, hemicellulose has strong hydrophilicity because of its complex structure and rich hydroxyl groups [8], which limits its application to a certain extent. The modification of hemicellulose is necessary to improve its properties and thus expand its utilization.

The pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass is usually performed before the modification since hemicellulose is closely bound to cellulose and lignin in plant cell walls. Chemical, physical, chemical–physical, and biological pretreatments have been developed to extract hemicellulose [9,10]. Hemicellulose with higher purity can be obtained after separation and purification, thus improving its reactivity and utilization efficiency. Generally, hemicelluloses directly extracted from lignocellulosic biomass have poor molecular chain flexibility and strong hydrogen bonds among molecules. Various procedures, including plasticization, blending, and chemical reaction, are helpful to obtain the ideal application performance of hemicellulose. There are a lot of hydroxyl groups in hemicellulose, allowing the modification of hemicellulose via etherification, esterification, and other reactions according to different bonding modes between hydroxyl groups and substituent groups. The modification of hemicellulose is helpful to improve its properties such as solubility, hydrophobicity, thermal stability, and thermoplastic performance, laying a good foundation for industrial utilization.

This review aims to present a comprehensive picture of the extraction of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass and the chemical modification procedures of hemicellulose. The research progress of the extraction and chemical modification of hemicellulose in recent years was summarized. The development trend and scientific research were also prospected to provide reference for a comprehensive utilization of hemicellulose.

2 Separation and extraction of hemicellulose

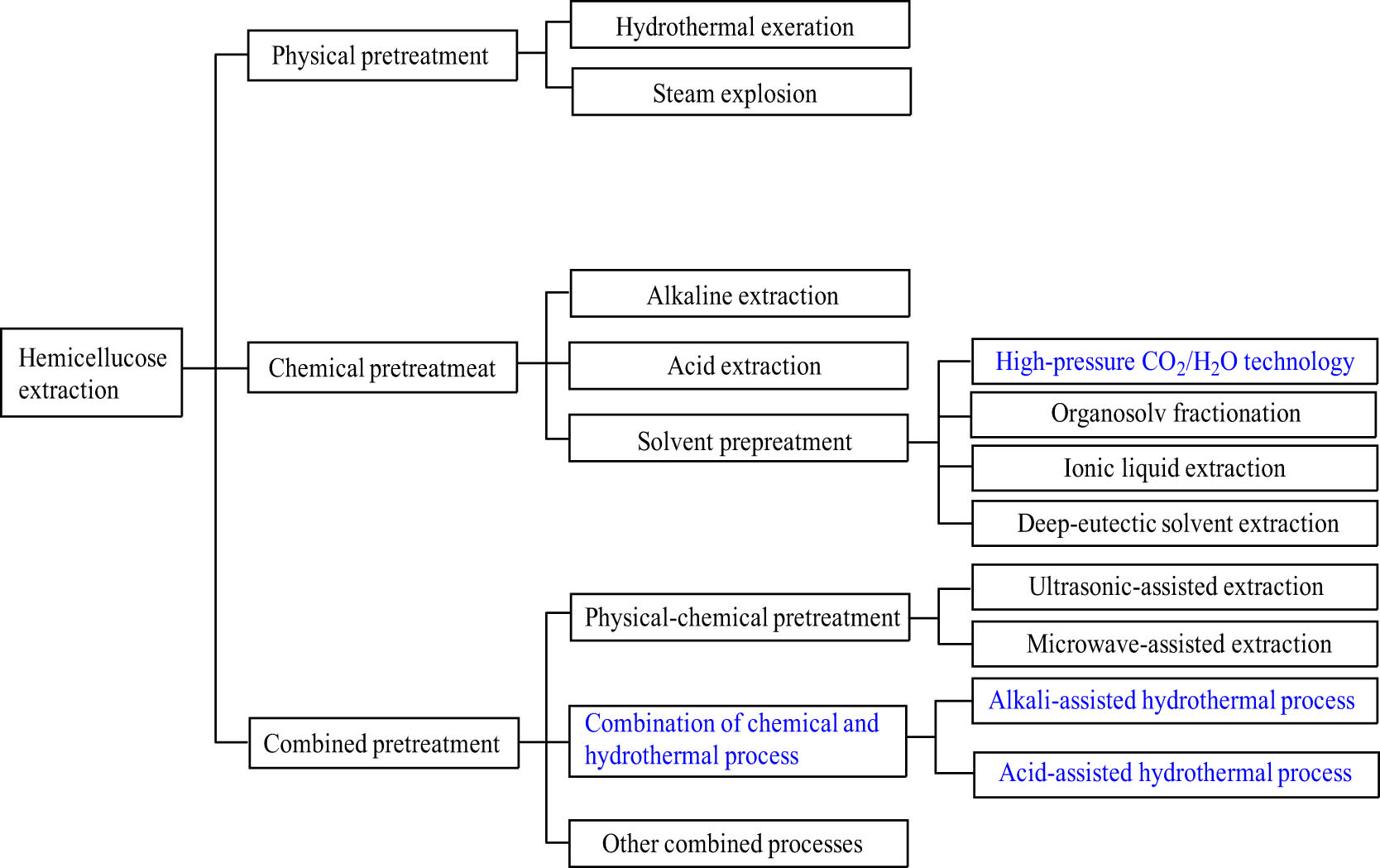

The separation and extraction of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass include hydrothermal extraction, steam explosion, acidic and alkaline pretreatments, solvent extraction, and ultrasonic-assisted and microwave-assisted processes (Figure 1) [11,12,13]. The components of the cell wall are separated by breaking the hydrogen bonds between hemicellulose and cellulose and the chemical bonds between hemicellulose and lignin. Generally, hemicellulose is partially or completely degraded during the pretreatment processes. In addition, there is almost no procedure that can extract hemicellulose completely without dissolving the other components [14].

The extraction process of hemicellulose.

2.1 Physical pretreatment

2.1.1 Hydrothermal extraction

The hydrothermal extraction (also named as autohydrolysis) is a promising technology for the pretreatment of lignocelluloses due to its advantages of short reaction time, high conversion, and relatively low reaction temperature, in which the aqueous solution is often used as a medium [15]. Almost no cellulose and lignin are dissolved during the hydrothermal extraction; thus hemicellulose is selectively separated via reduction in the solubility of other components.

Dordevic and Antov [16] reported the influence of hydrothermal pretreatment conditions on recovery and property of hemicellulose extracted from wheat chaff. The recovery and molecular weight of hemicellulose were successfully described by the combined severity factor and linear regression model. The recovery and the relative molecular weight, as well as some of bioactive and functional properties of hemicellulose, could be estimated, which determine its forthcoming application. The hydrothermal process was used for the selective solubilization of hemicelluloses from corn straw. The extent of xylan depolymerization depended on the severity of the autohydrolysis. A total of 72.1% of the original xylan was solubilized, and 63.2% of it was recovered as soluble saccharides including xylo-oligosaccharides (XOS), xylose, and arabinose in the liquor. The maximum yield at 53% of XOS and 3.78% of xylose (based on initial xylan content of corn stalk) was given. XOS and xylose were the main oligomeric components and monosaccharides, respectively [17].

The extraction of hemicelluloses from other lignocellulosic biomasses was also performed by autohydrolysis. Herein, 60% hemicelluloses from pine wood were extracted at 170°C for 60 min. The extracted hemicelluloses were primarily in an oligomeric form in the liquid phase, reaching a total concentration of 12.7 g·L−1 [18]. Hemicellulose was selectively extracted from Eucalyptus urograndis wood, giving 74.5% in the hydrolysate. Correspondingly, the glucan contents of the solid residue exceeded 90% [19]. Krogell et al. [20] investigated the hot-water extraction of acetylated water-soluble hemicellulose from spruce wood at 170°C with a batch extraction setup. About 30% of the wood was dissolved, and hemicellulose could be almost completely extracted. The yield of hemicellulose reached 23.47% from wheat straw via autohydrolysis [21]. The recovery value of the as-extracted hemicellulose reached 73.65%. Hemicelluloses of molecular weights >30 kDa together with the 1–5 kDa group were obtained, both as majority in the extracts [5]. The as-extracted hemicellulose with high molecular weight is generally obtained by autohydrolysis, which has a broad application prospect.

The composition, molecular weight, and properties of hemicellulose are affected by hydrothermal pretreatment conditions. Triploid of Populus tomentosa Carr. was treated using an organic alkaline solvent of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) during hydrothermal pretreatment. The influence of treatment conditions on the composition, structural characteristics, physical and chemical properties, and thermal performance of hemicellulose was investigated. The hemicellulosic fractions were mainly composed of (1 → 4)-linked α-d-glucan from amylose and (1 → 4)-linked β-d-xylan from minor amounts of branched sugars. A major amount of xylose (52.9%) was contained in the hot water-soluble hemicellulosic fraction. The addition of DMF favored the extraction of hemicelluloses with high molecular weights. The extraction with an increasing DMF concentration from 10% to 50% led M w to increase from 3,330 to 24,840 g·mol−1. Compared with branched hemicellulose, linear hemicellulose has higher thermal stability, and the values of molecular weights and branching of the hemicelluloses played important roles [22]. Yang et al. [21] investigated the extraction of hemicellulose from eucalyptus via hydrothermal pretreatment, and the extracted hemicellulose was mainly in the form of oligose. The pH value displayed a significant effect on the dissolution of lignocellulosic main components. The dissolution of hemicellulose was promoted while the dissolution of cellulose and lignin was inhibited with preadjustment at pH 4.0. Correspondingly, the highest hemicellulose extraction with minimal changes in the physicochemical structure was obtained.

Gallina et al. [23] investigated the extraction of hemicellulose from Eucalyptus grandis using a semicontinuous reactor, which has the advantage of separating the solid (easy to charge and keep inside a tubular reactor) and the liquid (moving through the bed created) easily. Solid residence times between 20 and 40 min were perfect for extracting hemicelluloses. It avoided solid pump transport and extreme grinding and thus greatly reducing the cost. This study established the basis of the scale-up of the semicontinuous hydrothermal reaction, making the semicontinuous reactor expected to be one of the best choices for biomass pretreatment in future industrial applications. The extraction of hemicellulose from catalpa wood was also performed by using a flow-through reactor with hot pressurized water, giving a hemicellulose yield of 38.8% on a lab scale at 170°C for 90 min, which raised to 41.7% in pilot scale under the identical conditions [24].

High-pressure liquid hot water is used for extraction and fractionation in subcritical water extraction (SWE) with environmental friendliness, high selectivity, high cleanliness, low cost, and saving of raw materials and energy. The extraction of hemicellulose from different wood species, namely stone pine, holm oak, and Norway spruce, was carried out using SWE. The composition, extraction rate and yield of hemicellulose, and lignin leaching were significantly depended on experimental parameters such as wood species and temperature. The composition of hemicelluloses varied not only between the hard wood holm oak and the soft woods but also between stone pine and Norway spruce. The fastest extraction of hemicellulose from stone pine was obtained at lower temperature, whereas high yield of hemicellulose from holm oak was obtained most rapidly at higher temperature. The main sugar in stone pine was determined to be mannose, followed by xylose and galactose, which together accounted for about 18% of the dry mass. In the case of holm oak, however, the main sugar was xylose, followed by glucose and galactose [25]. Leppänen et al. [26] used SWE to separate hemicellulose from Norway spruce saw meal. The solubility of hemicellulose was significantly enhanced via increasing temperature. Only a small amount of hemicellulose was extracted in the range from 120°C to 160°C while hemicellulose was almost completely dissolved (∼22%) and hydrolyzed into monosaccharides once the temperature over 220°C. In addition, the molecular weight of hemicellulose dropped with increase in temperature. Surprisingly, the extracted carbohydrates were still mainly in the form of polysaccharides even when the temperature was increased up to 240°C. The extraction of hemicellulose from oil palm leaves was also performed by SWE. The extraction rate of hemicellulose reached 69.6% with the condition of 190°C and 4.14 MPa [27].

The liquid phase with rich oligosaccharides derived from hemicellulose and the solid phase containing cellulose and lignin are well separated by hydrothermal extraction. However, high energy consumption is required as hydrothermal pretreatment is generally operated at high temperature. Moreover, the mechanism of hydrothermal extraction is similar to that of weak acid pretreatment [28], which degrades polysaccharides to monosaccharides. As a result, hemicelluloses with lower degree of polymerization (DP) are generally obtained.

2.1.2 Steam explosion

High temperature and pressure are used to pretreat lignocellulosic biomass during steam explosion, in which water vapor penetrates into the cell wall. As a result, the structure of the cell wall is destroyed, and the components are then separated.

Teng et al. [29] studied the production of XOS from corncob with DP in the range from 1.8 to 2.5 using steam explosion. The recovery rate of hemicellulose was 22.8% under the optimal conditions at 196°C for 5 min. A maximum XOS yield at 28.6% (based on the initial xylan content of corncob) was achieved. More than 90% of xylobiose and xylotriose were contained in the XOS syrup. Hemicellulose from banana rachis was extracted by steam explosion at three severity levels followed by fractionation via graded ethanol precipitation method. The extraction yield of hemicellulose increased with the severity level and treatment duration, and the maximum precipitation yield of hemicellulose at 81.4% was obtained in 60% ethanol [30]. Hemicellulose was extracted from corn cob using a tubular reactor, and the extraction rate reached up to 82%. Only a small amount of furfural was produced in the extraction process, overcoming the problem of easy degradation in the conventional steam pretreatment process [31].

Hydrothermal extraction and steam explosion are common physical pretreatment methods, in which chemicals are not used, thus reducing the cost and environmental pollution. However, high temperature and pressure are required, leading to high requirement for equipment and high energy consumption. In addition, the chemical connection between hemicellulose and lignin cannot be destroyed completely, so hemicellulose with low purity is usually obtained [32].

2.2 Chemical pretreatment

2.2.1 Alkaline extraction

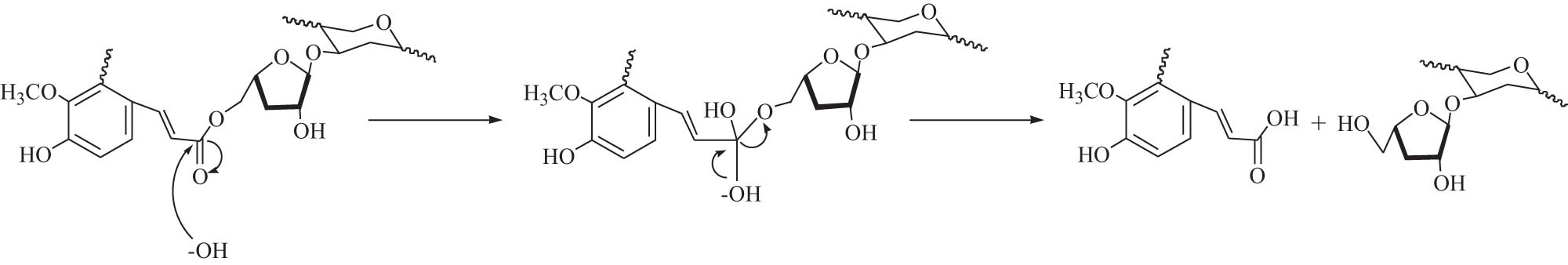

Alkaline extraction is a common process for separating and extracting hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass. The hydrogen bonds between hemicellulose and cellulose molecules and the chemical bonding between lignin and hemicellulose are destroyed. Therefore, the swelling of cellulose and the hydrolysis of hemicelluloses are promoted. Both of them enhance the dissolution of hemicellulose, thus extracting hemicellulose with high purity. The common mechanism for the alkaline extraction of hemicellulose from biomass is shown in Scheme 2, in which the ester bond between ferulic acid of lignin and the sugar residue of hemicellulose in the cell wall are cleaved [33].

The mechanism of alkaline extraction of hemicellulose.

Inorganic alkali solutions are usually used in alkaline procedures, and NaOH solution is the most common. Hemicelluloses were partially extracted from commercial bamboo chips with NaOH solution prior to kraft pulping. Around 50% of hemicellulose was achieved without degrading cellulose and lignin [34]. The process for extraction of crude xylan from sweet sorghum bagasse was optimized by the response surface methodology. A total of 79% xylose, 5.3% arabinose, and 1.7% glucose was contained in the crude xylan under the optimized conditions, in which extraction time of 3.91 h, extraction temperature of 86.1°C, and NaOH concentration (w/w) of 12.33% were used [35]. Geng et al. [36] studied the extraction of hemicellulose from six different biomasses under an alkaline condition. Both total lignin content in original materials and alkaline-stable lignin–carbohydrate complex linkages content affected xylan extractability negatively, and the former appears to be the main determining factor. The solubilization of xylan dropped with increase in lignin content. In 10% NaOH solution, the efficiency of solubilizing xylans from nonwoods and hardwoods was in the range from 80% to 91% and from 65% to 73%, respectively. Alkaline treatment was also used for extracting hemicellulose from fully bleached hardwood pulp and partially delignified switchgrass. Molecular weights of 49,200 and 64,300 g·mol−1 for switchgrass and bleached hardwood pulp were achieved in 10% NaOH solution. Almost no lignin was detected in hemicellulose with 89.5% content from bleached hardwood pulp, whereas 3–6% lignin in hemicellulose with 72–82% content from switchgrass, depending on the NaOH concentration used during the extraction (3–17% NaOH solution) [9].

Generally, hemicellulose with high yield as well as high purity was extracted using the NaOH solution. Zhang et al. [37] revealed the influence of the organizational difference of corn stalk on hemicellulose extraction. The extraction of hemicellulose from different parts such as leaf, bark, and pith of corn stalk was investigated in NaOH solution. Linearized xylan was obtained because native 4-O-methylglucuronic acid side groups were removed during the pulping process. The xylan recovery ratio of hemicellulose extracted from pith reached 91.03%, giving a high purity of 84.89%. Hemicelluloses were recovered from corncob, cotton waste, olive, apple tree pruning, and pepper and chilli wastes by direct alkaline extraction and raw material delignification. The extracted hemicellulose was brown thin film with molecular weight between 30,997 and 91,796 g·mol−1, and the lignin content was less than 4.46% [38]. NaOH and NH4OH were used as strong base and weak base together for extracting quality hemicellulose from sugarcane bagasse. The recovery of hemicellulose was enhanced by the synergistic effect (68 wt% xylose), which was 1.3 times of that obtained using the individual alkaline protocols. Additionally, the as-extracted hemicellulose predominantly contained the xylose in the form of xylan with less undesired residual biomass constituents such as lignin [39]. Kim et al. [40] obtained high purity xylan and glucomannan by using a two-stage alkaline extraction, in which kraft hardwood dissolving pulp was treated in 24 wt% KOH, 18 wt% NaOH and 4 wt% H3BO3 solutions effectively. The extraction yield of xylan at 76.4% was achieved.

H2O2 extraction is also a common alkaline process to separate hemicellulose from plants. Alkaline H2O2 is an effective agent for both delignification and solubilization of hemicelluloses. Azeredo et al. [41] used H2O2 solution to extract hemicellulose from wheat straw, and the purity of hemicellulose reached 88%. Pereira et al. [42] investigated the use of alkali H2O2 solution to extract hemicellulose from wheat straw, supplying high purity of 91.28%. Brienzo et al. [43] optimized the conditions for extracting hemicellulose from sugarcane bagasse in H2O2 solution. Hemicellulose with a high recovery rate of 86% and a low lignin content of 5.9% was obtained with 6% H2O2 at 20°C for 4 h. All the isolated hemicelluloses were mainly composed of xylose (73.1–82.6%) with small amounts of arabinose, glucose, and glucuronic acid.

Other alkaline sources were also used for hemicellulose extraction. Hutterer et al. [44] evaluated the extraction efficiency of hemicellulose from three economically interesting hardwood species: beech, birch, and eucalyptus using white liquor recovered from the cooking liquor as alkali source. Both the extraction efficiency and molar mass distribution of hemicellulose were significantly affected by variables of temperature and effective alkalinity, whereas the hemicellulose content of the initial pulps, the hardwood species, and the type of applied base played minor roles. The extractions are generally facilitated at temperatures more than 40°C due to lowered lye density. The extraction performance reaches a maximum at 120 g·L−1 effective alkalinity for treatments at 60°C and 80°C, resulting in a residual xylan concentration in the pulp of about 3 wt%. This behavior can be explained by swelling of the pulps, which improves the accessibility of hemicelluloses to the alkaline lye, facilitating their dissolution.

Imidazole is an efficient alternative solvent leading to extensive delignification of lignocellulosic biomass, even at moderate temperature. Imidazole has been used for starch dissolution [45] and pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass [46] as it is easy to handle and recycle. Pereira et al. [47] studied the pretreatment of the extracted residues from Cupressus lusitanica Mill. using the alkaline solvent of imidazole. Imidazole enables easy waste biomass pretreatment and allows fractionation of main polymeric fractions into cellulose-rich and hemicellulose-rich materials without noteworthy degradation of polysaccharides. It was found that the recovery of hemicellulose was highly dependent on pretreatment conditions. The hemicellulose recovery was as high as 79.5%, and 49.65% yield of xylose was obtained. Toscan et al. [48] treated elephant grass with imidazole, and 15.8 wt% extraction of initial hemicellulose was obtained at 110°C for 120 min.

Hemicelluloses extracted from lignocellulosic biomass using alkaline procedure possess high extraction rate, purity, and DP, which are beneficial to expand high-value utilization. Therefore, the as-extracted hemicellulose is highly expected to be applied in various fields. However, high pollution and cost are involved in the conventional alkaline process.

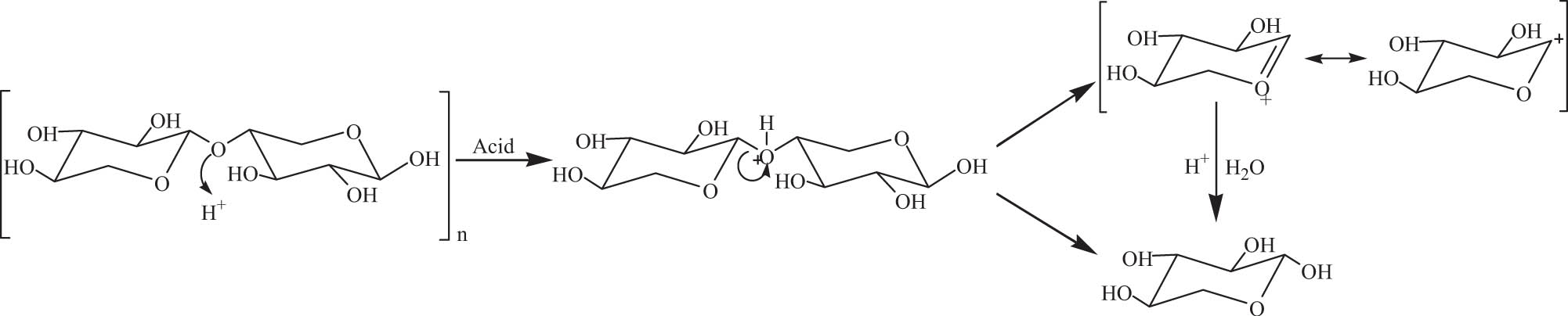

2.2.2 Acid extraction

In the presence of acid, the hydrogen bonds between hemicellulose and cellulose break and the hydrolysis of hemicellulose occurs [49]. As a result, the main components of lignocellulosic biomass could be separated. H2SO4, HCl, HF, and HNO3 are commonly used in acid extraction, as shown in Scheme 3 [50].

Acid extraction of hemicellulose.

A low-acid hydrothermal fractionation was developed to recover hemicellulosic sugar (mainly xylose) from Miscanthus sacchariflorus Goedae-Uksae 1. The maximum xylose yield of 74.75% was obtained with 0.3 wt% H2SO4 at 180°C for 10 min. The conversion of hemicellulose to monosaccharides with a degree of further decomposition is unavoidable, and 86.41% degradation rate of hemicellulose (mainly xylan) was observed. The low-acid hydrothermal fractionation was also efficient for the conversion of xylose in the hydrolyzate into furfural without further decomposition. Approximately, 50% of unrecovered xylose seemed to be converted to furfural [51]. Diluted H2SO4 was used as the catalyst to obtain xylan, mannan, and galactan from rapeseed straw. The removal of hemicellulose, the production of sugars (xylose, glucose, and arabinose) in the hydrolysate, and the formation of by-products (furfural, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, and acetic acid) were significantly affected by parameters such as acid concentration, temperature, and reaction time. The total sugar recovery reached 85.5% in 1.76 wt% H2SO4 solution at 152.6°C for 21 min. Among them, xylan, mannan, and galactan accounted for 78.9% [52]. The extraction of hemicelluloses and lignin for wood fractionation using acid hydrotrope of p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TsOH) under mild conditions was also developed by Wu et al. [53]. p-TsOH is widely used as hydrotrope as it is able to increase the water solubility of hydrophobic compounds. Hemicellulose and lignin were solubilized sequentially, enhancing the delignification and extraction of hemicelluloses. Hemicellulosic sugars were harvested as one of the main products from the stepwise deconstruction of biomass, and 55.1% xylan was recovered from wood at 120°C for 2 h.

Although acid hydrolysis allows the extraction of sugars with high quantities, the yield and molecular weight of the extracted hemicellulose are relatively low due to its easy hydrolysis under acidic conditions. Therefore, the product is mainly composed of monosaccharides rather than xylan. In addition, side reactions and strong corrosivity also involved in acid pretreatment.

2.2.3 Solvent pretreatment

2.2.3.1 Organosolv fractionation

Hemicellulose can be extracted by organic solvents including pure organic solvent and complex organic solvent systems composed of organic solvent with water, alkali, and acid. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 1,4-dioxane are the most common solvents. Snelders et al. [54] investigated the distribution of wheat straw components in different organosolv fractionations, and the results showed that the organic solvents based on acetic acid and formic acid could successfully separate wheat straw into its major components cellulose, lignin, and hemicelluloses. The hemicellulose-rich fraction was rich in sugars (58%) but also contained considerable amounts of minerals, proteins, and organic acids. Ebringerová and Heinze [55] found that DMSO and DMSO/water mixture were effective for extracting low-branching xylose without breaking acetyl groups and glycoside bonds. Hemicellulose with structural integrity was thus obtained, which is conducive to study the structure of native hemicellulose. Holocellulose was obtained by dewaxing and delignification of corn stalk, which was sequentially performed by benzene–alcohol extraction and sodium chlorite delignification treatment. Hemicellulose was further isolated from holocellulose via extraction using various solvent systems. Hemicellulose extracted from the solvent system composed of DMSO with dioxane hexyl-triethylamine possessed higher branching degree and with lower thermal stability than that extracted from the inorganic base system. The backbone chain of the hemicelluloses extracted by DMSO was β-d-xylose with acetyl group, and the branched chains contained l-Arabia sugar and 4-O-methyl glucose uronic acid [56].

Organosolv pretreatment was applied to generate useful coproducts and improve saccharification yield from Sitka spruce sawdust. Under the most efficient pretreatment conditions, a large part of hemicellulose sugars was converted to ethyl glycosides, and the saccharification yield reached up to 86%. The ethyl glycosides were more stable to dehydration than the parent pentoses, thus the conversion of pentoses to furfural was reduced [57]. Hemicelluloses were extracted from Caesalpina pulcherrima and Tamarindus indica, providing yields of 25% galactomannan and 20% xyloglucan, respectively. The former was carried out in 96 wt% ethanol at 70°C for 20 min, and the latter was boiled in distilled water for 50 min. Both of galactomannan and xyloglucan had a good thermal stability, and M w of 4.35 × 106 and 2.03 × 106 g·mol−1, respectively, was determined. The difference in the molecular weight distribution could be ascribed to different mannose/galactose ratios from C. pulcherrima and T. indica [58].

Organosolv extraction has the advantages of direct separation of hemicellulose without delignification. The functional groups acetyl groups in the cell walls of lignocellulosic biomass are not converted to acetic acid and then shed off, so the structure of hemicellulose is well preserved. Hemicellulose extracted by organosolv extraction possesses high purity, good activity, and similar structure to that of native hemicellulose, providing the possibility for further utilization. However, organic solvents are generally difficult to degrade, flammable, volatile, and/or toxic, leading to environmental pollution and thus limiting large-scale application.

2.2.3.2 Ionic liquid (IL) extraction

ILs are salts usually composed of a large organic cation and an organic or an inorganic anion with a low melting point (<100°C). The application of ILs in chemical reactions is considered a green method due to its low vapor pressure, high thermal and chemical stability, and easy separation from other substances [59]. ILs have attracted increasing attentions in the separation process as they can solubilize both organic and inorganic substances well. ILs are considered substitutes for volatile organic solvents and have been widely used in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass [60]. The intramolecular/intermolecular hydrogen bonds of cellulose and hemicellulose are destroyed by the hydrogen bond interaction between the hydroxyl group of polysaccharides and the anions of ILs, thus promoting the separation of polyxylose.

It is common to pretreat lignocellulose with ILs in the presence of a base. 1-Allyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([Amim]Cl) was used as a solvent to dissolve and fractionate bamboo. Hemicellulose was effectively separated using 0.5 M NaOH aqueous solution followed by 70% ethanol containing 1.0 M NaOH. The as-isolated hemicelluloses are mainly consisted of 4-O-methyl-α-d-glucurono-α-l-arabino-β-d-xylan. Alkaline extraction contributed much to the fractionation while [Amim]Cl treatment displayed limited influence. [Amim]Cl dissolution and regeneration reduced the total yield of fractionation but increased partially fractured side-chains of hemicellulose. Hemicellulose was slightly degraded, and its side-chains were partially cleaved [61]. A complete isolation of lignocellulosic compounds from oil palm empty fruit bunch using IL and alkaline treatment was investigated by Mohtar et al. [62]. Hemicellulose of 27.17% yield with smaller particle size was obtained, giving molecular weight of 1,736 g·mol−1 and degradation temperature of 236.25°C. A fully amorphous hemicellulose fraction could not be obtained by the proposed isolation technique, whereas IL could be recovered and reused with an overall recovery of 48 wt% after four cycles.

Anugwom et al. [63] developed the selective extraction of hemicelluloses from spruce wood using switchable ionic liquids (SILs). The hemicellulose content was reduced by 38 wt% using butanol SIL and by 29 wt% using hexanol-SIL for treating 5 days. Hemicellulose extracted from bamboo was selected as a model to investigate the dissolution of hemicellulose in 1-butyl-3-methyl imidazolium. The solubility of hemicellulose was greatly affected by temperature and the anion structure of ILs, reaching 4.02 g/100 g at 13°C. Almost no degradation of hemicellulose occurred during the dissolution process, so the backbone structure of hemicellulose kept well [64]. Lan et al. [65] studied the isolation of hemicellulose from bagasse using IL treatment followed by alkaline extraction. Hemicellulosic fraction of 26.04% yield was obtained and mainly was 4-O-methyl-d-glucuronoxylans with some R-l-arabinofuranosyl units substituted at C-2 and C-3. The fractionation of wheat straw into cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin-rich fractions using 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate was developed. It was found that higher temperature and longer time favored enhancing the purity of the fractionated lignocellulosic materials. The highest purity of hemicellulose at 96 wt% was obtained at 140°C for 6 h [66].

The separation and transformation of the main lignocellulosic biomass components within the biorefinery concept were also developed. Wheat straw hemicellulose was selectively and effectively hydrolyzed into xylose and arabinose in aqueous solution of acidic 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate. The yield and the recovery of pentoses from the reaction liquor reached 80.5 and 88.6%, respectively. Moreover, ILs could be recycled with a high yield of 92.6 wt% and reused without losing the performance on the selective hydrolysis of hemicellulose [67].

IL pretreatment has the advantages of good separation efficiency and solvent recycling without pollution. Although Chen et al. [68] reported that ILs are not necessarily expensive, the preparation process of ILs is often complicated and higher cost than common media such as organic solvents and H2O. Moreover, hemicellulose extracted by ILs tends to be with some impurities and slightly degraded, leading to partial breakage of side chains. Therefore, the further commercial application of ILs still remains difficult.

2.2.3.3 Deep-eutectic solvent (DES) extraction

In 2003, Abbott et al. [69] first discovered that urea and choline chloride (ChCl) could form a solvent, named as DES. It is a eutectic mixture composed of hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and hydrogen bond donor (HBD) with low melting point and vapor pressure, high solubility, and adjustable structure. DES exhibits the interactions of hydrogen bonds, electrostatic forces, and Van der Waals forces. The highest fraction of hydrogen bonds is generally formed between HBD and the anion of HBA [70]. The hydrogen bonds between DES molecules and solutes are responsible for the dissolution of solutes in DES [71]. DES has been researched and exploited extensively in the field of separation technology, including biomass deconstruction and processing, because of its flexible constituents and versatile nature [72]. Xylan can be dissolved well in DES due to hydrogen bonds between the DES molecule and the polysaccharide [71], which destroys the intermolecular hydrogen bond of the solute.

DES from ChCl:glycerol alone for pretreatment appeared to be ineffective unless severe conditions (150°C for 15 h) were applied to achieve a decent sugar yield. A total of 41 g fermentable sugars (27 g glucose and 14 g xylose) could be recovered from 100 g corncob, representing 76% of the initially available carbohydrates [73]. Surprisingly, xylose-rich liquor was obtained from switchgrass by fractionating in an acidified DES derived from ChCl and glycerol under mild conditions (120°C for 1 h). The solvent was recycled successfully and maintained its capability during four recycles [74]. Rice straw was treated by lactic acid/ChCl–water solution. Both HBA and HBD were responsible for the effective biomass fractionation possibly due to their synergistic effect on highly efficient breakage of the linkage between hemicellulose and lignin. More than 70% xylan was removed and fractionated into the liquid stream as forms of xylose, furfural, and humins. DES could be recovered with high yield, and 69% was recovered after five cycles at 90°C [75].

There are few studies focused on the mechanism of DES pretreatment. The pretreatment of rice straw in DES composed of ChCl and lactic acid was investigated by Hou et al. [76] DESs contained lots of hydroxyl or amino groups with a high intermolecular hydrogen-bond strength and exhibited weak biomass deconstruction abilities. The presence of strong electron-withdrawing groups in DES was helpful for removing xylan. In addition, a temperature-dependent negative relationship between xylan removal and pK a value of HBD was observed. DESs were prepared by the reaction of ChCl with five hemicellulose-derived acids. The as-prepared DESs were used to isolate hemicellulose from herbal residues of Akebia. Xylan almost dissolved completely and about 74.90% of xylose was in the form of an oligomer in the liquid [77].

Pure DES usually has high viscosity, which hinders its application. Therefore, the dissolution of hardwood xylan in DES aqueous solution was explored by Morais et al. [78]. Xylan solubilization of 328.23 g·L−1 was obtained using 66.7 wt% DES in water at 80°C. Furthermore, xylan could be recovered by precipitation from the DES aqueous media with above 90% yield. The solubility of xylan in DES/water solution containing 50% ChCl/urea was similar to that obtained by normal medium alkali water solution, confirming the potential of DES in the xylan isolation.

The DES extraction is environmentally friendly, easy to prepare and recycle. It is a new solvent system with 100% atomic economy and is considered an alternative for conventional solvents to extract polyxylose. Polyxylose with a high recovery rate and structure integrity is generally achieved in the dissolution/recovery process of DES. However, hemicellulose and lignin are usually dissolved synchronously. As a result, the extraction selectivity and the purity of components are less prominent. In addition, the influence of intermolecular hydrogen bond strength of DES on the structure and the mechanism of DES pretreatment were less investigated at present.

2.2.3.4 High-pressure CO2/H2O technology

High-pressure fluids have received an increasing attention as alternatives to common solvents. CO2 and H2O are the most promising high-pressure fluids in view of green chemistry principles since they are renewable and nonflammable [79]. The mixture of high-pressure CO2 and H2O has been considered a serious alternative to conventional acid-based technologies [80] for the valorization of lignocellulosic biomass to produce value-added chemicals [81]. CO2 dissolved in H2O promotes acid-catalyzed dissolution of biomass due to the formation of carbonic acid. Correspondingly, the dissolution and hydrolysis of hemicellulose into its corresponding sugars, including xylose monomers and oligomers with low DP, were also enhanced [82,83].

The effect of CO2 as a catalyst on the hydrothermal production of hemicellulose-derived sugars either as oligomers or as monomers was widely investigated. Zhang and Wu [84] reported the influence of subcritical CO2 pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse with 15% (w/v) solids on the yield of pentose. The maximum xylose yield was 15.78% based on raw materials, in which 45.15% of xylose could be recovered as XOS. High-pressure CO2/H2O technology was also used for the processing of wheat straw, in which wheat straw hemicellulose was effectively dissolved because the addition of CO2 to water-based processes. The in situ formation of carbonic acid leads to an increase in hydronium ion concentration and a decrease in pH value. High recovery of XOS with minimal coproduction of degradation products was obtained. XOS with 14.8 g·L−1 concentration was found to be the main products in the produced liquor, yielding 79.6 g XOS per 100 g initial xylan content. In addition, xylose was the main monosaccharide, and the concentration of released xylose corresponded to 9% of the initial xylan content under the best condition for XOS production [85]. A water-soluble fraction containing pentoses in oligomer and monomer forms could be extracted from wheat straw using the high-pressure CO2/H2O process. XOS and xylose were produced as the main products presented in the hydrolysates, highly depending on the operational conditions. About 81 mol% hemicellulose was converted to xylose and arabinose (mainly as oligomers) at 200°C and 50 bar of initial CO2 pressure, yielding 71.7 wt% XOS based on the initial xylan content [86]. Corn stover was pretreated by CO2 and liquid hot water, and the concentrations of xylose were found to be enhanced by the formation of carbonic acid. The recovery of XOS and/or xylose was obviously improved by using the high-pressure CO2/H2O technology compared to that of CO2-only or H2O-only pretreatment. Xylose concentration of 483.5 mg·L−1 was obtained at 210°C, whereas high xylan recovery occurred at a lower temperature of 180°C [87].

Compared to conventional hydrothermal treatments, no additional catalyst is required for the high-pressure CO2/H2O technology. Although it is similar to the pretreatment process catalyzed by a weak acid, the acidity of the medium does not constitute an environmental problem due to the removal of CO2 by depressurization. However, the generation of degradation products is usually considerable under high pressure and temperature.

2.3 Combined pretreatment

2.3.1 Physical–chemical pretreatment

2.3.1.1 Ultrasonic-assisted extraction

The ultrasonic technology has attracted increasing attention due to its important contribution to environmental sustainability, high efficiency, low-energy consumption, and mild conditions compared with other processes. It has been used for treating lignocellulosic biomass. During the ultrasonic-assisted extraction, ultrasonic waves generate high-frequency vibrations, which further produces acoustic cavitation effects between solute and solvent, causing tiny bubbles in the solution to burst suddenly, thereby destroying the cell wall structure and then separating the components.

Sun and Tomkinson [88] investigated the extraction of hemicellulose from wheat straw via ultrasonic assistance. Compared with conventional alkaline procedure, the yield of hemicellulose was increased by 1.8%. In addition, the obtained hemicellulose possessed higher purity and thermal stability but with a lower content of associated lignin. Hemicellulose was also extracted from depithed corn stover by using the ultrasonic-assisted process, and the extraction rate of hemicellulose was increased by 2.6 times [89].

The ultrasonic-assisted alkaline extraction was widely investigated. The extraction of hemicellulose from grape pomace was carried out using a low concentration KOH of 0.4 M and short extraction time of 2.6 h with ultrasonic assistance at a mild temperature of 20°C. The extraction yield of hemicellulosic polymer was significantly improved by using ultrasonic assistance, and ∼7.9% extraction yield of hemicellulose and its derived polysaccharides was achieved. The yields of xyloglucans, mannans, and xylans were increased by 16%, 21%, and 27%, respectively [90]. Xie et al. [91] investigated the extraction and structural properties of hemicellulose from sugarcane bagasse pith by using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline process. The total yield of hemicellulose was increased by 3.24%. A maximum total hemicellulose yield of 23.05% was obtained with KOH concentration of 3.7 wt% at 53°C for 28 min. However, the xylose content of the obtained hemicellulose was slightly decreased. Xylose was the dominant component in water-soluble hemicellulose (69.05%) and alkali-soluble hemicellulose (85.83%). In addition, the content of residual lignin was reduced by the response surface methodology optimization, thus improving the purity of hemicellulose. The yield of hemicellulose of 37.17% was obtained under the optimal extraction conditions with 7 wt% KOH at 58°C for 21 min via the ultrasonic-assisted alkaline process [92].

The application of ultrasonic assistance has been proved to be effective for the alkaline extraction of hemicellulose. Ultrasonic pretreatment causes the breakage of polysaccharide glycoside bond, which significantly improves the extraction of polysaccharide and the yield of the extracted hemicellulose with low temperature and short time. In addition, hemicellulose extracted by using the ultrasonic-assisted process has a smaller branching degree, less acidic groups, lower content of associated lignin, high molecular weight, and thermal stability.

2.3.1.2 Microwave-assisted extraction

Microwave heating is a clean and environmentally friendly technology under the action of electromagnetic radiation. The conversion of microwave energy into heat energy is usually facilitated by dipole polarization, ionic conduction, and interfacial polarization [93,94]. Microwave heating has been widely applied in the pretreatment of materials due to the advantages of uniform heating, high thermal efficiency, strong penetrability, mild reaction conditions, and so on. The microwave-assisted extraction is considered one of the least time-consuming methods in the hemicellulosic pretreatment. The heat transfer is more efficient as the heat is generated within the core of the material via the interaction of microwave with biomass [95]. The polar molecules in the biomass vaporize and/or expand with a very short time to reach the activation state.

The extraction of polymeric hemicellulose from spruce sawdust was investigated using the microwave-assisted extraction at atmospheric pressure by Chadni et al. [96]. High-molecular-weight hemicellulose chains from spruce wood with less depolymerization and degradation were extracted effectively. The microwave-assisted process promoted the extraction of arabinose and galactose compared with the conventional extraction, supplying a high solubilization of wood and a selective extraction of hemicellulose polymers. Hemicelluloses obtained from a neutral medium accounted for 24 and 19.50% of galactose and 10.50% and 5% of arabinose for microwave (573 W) and conventional extraction, respectively. The highest amount of the extracted hemicellulose from presoaked wood at 27.5 mg·g−1 (based on dry wood) was obtained after treating in 1 M NaOH solution using 573 W microwave assistance more than 1 h [96]. Hemicellulose was extracted from flax shives using the microwave-assisted water and/or aqueous ethanol. The total yields of hemicelluloses extracted were 18% and 40%, respectively. A reduction in hemicellulose yield was observed with increasing microwave irradiation time, probably due to the degradation of macromolecular xylan. Moreover, the yield of hemicellulose obtained by the microwave-assisted process was much lower than that obtained by pressurized low-polarity water (reached up to 90%), indicating that furthermore exploration is necessary for microwave assistance [97].

The microwave-assisted extraction has advantages of rapid, saving energy, and environmental friendliness. Compared with conversional heating processes, the microwave extraction inhibits the degradation and polymerization of hemicellulose and the loss of acetyl with mild conditions but also with lower recovery efficiency. In addition, the microwave assistance is more effective for the extraction of branched hemicellulose; thus the yield and molecular weight of the hemicellulose obtained by the microwave extraction are lower. So far, it is difficult to be applied in large-scale industrialization.

2.3.2 Combination of chemical and hydrothermal process

2.3.2.1 Alkali-assisted hydrothermal process

A combination of hydrothermal pretreatment and alkaline treatment has been used for the separation of hemicellulose. Hemicellulose was isolated from eucalyptus fiber using the hydrothermal process followed by the alkaline treatment. Both the composition and molecular weight of the extracted hemicellulose were significantly affected by temperature. Hemicelluloses isolated at a lower temperature in the range from 100°C to 160°C were rich in xylose and glucuronic acid while rich in xylose, glucose, and mannose at a higher temperature of 180°C. The amount of lignin in the isolated hemicellulose increased with increase in temperature. Obvious hydrolysis of the glycosidic linkages in the xylan backbone occurred during the hydrothermal pretreatment. Therefore, both the molecular weight and branched chain of hemicellulose dropped with increasing temperature [98]. Fu et al. [99] reported the extraction of hemicelluloses from Populus tomentosa Carr. via the delignification using NaClO2 and the hydrothermal process with ethanol solution at 160°C, successively. A higher ethanol concentration (45–80%) favored the isolation of hemicelluloses with more side chains and lower glucose contents. The molecular weight of the extracted hemicellulose was related to the ethanol concentration used for precipitation. Hemicelluloses with smaller molecular weights were precipitated in 30–60% ethanol, whereas higher molecular weights were obtained in 10% and 20% ethanol. The molecular weights of these polysaccharides ranged between 2,842 and 5,101 g·mol−1, and they are much lower than those reported by Mendes et al. [58]. This can be ascribed to the difference in pretreatment methods: the structure of hemicelluloses was retained well by organosolv process, whereas the degradation of hemicelluloses was easy to occur in the hydrothermal process.

The water-soluble process combined with the alkali-soluble process was used for extracting hemicellulose from corn stalks. The extraction yields of hemicelluloses at 32.21% and 40.18% were obtained by using simple hydrothermal process and alkaline process, respectively. Surprisingly, the total extraction yield of hemicellulose was enhanced to 67.7% after combining these two processes [100]. Unbleached eucalyptus sawdust was treated by using the alkali-mediated hydrothermal approach to extract high-purity hemicellulose. The isolated hemicellulose displayed a typical hardwood xylan composition and was mostly deacetylated with low-lignin contamination. It is believed to be of great significance for improving the process efficiency, recovering waste biomass resources, and an integrated forest biorefinery [101].

The extraction of bamboo hemicellulose using freeze–thaw-assisted alkaline treatment was studied. Hemicellulose with higher purity, higher molecular weight, and lower polydispersity was extracted, giving an extraction rate of 64.71% and providing a new green-efficient method for the extraction of hemicellulose [102]. Toscan et al. [103] combined imidazole with hydrothermal treatment to treat elephant grass. A liquor rich mainly in xylo- and glucooligosaccharides, as well as pentoses, was obtained by the hydrothermal pretreatment under nonisothermal conditions. The most severe reaction conditions permitted the complete solubilization of xylan and arabinan, giving 97.1 wt% of the hemicelluloses removal from the original biomass. The maximum total recovery of xylan at 57.1 wt% and arabinan at 47.3 wt% was obtained.

2.3.2.2 Acid-assisted hydrothermal process

The acid-assisted hydrothermal processes were also developed for the extraction of hemicellulose. Hemicellulose was isolated from birch sawdust using formic acid-aided hot-water extraction. Compared with conventional hydrothermal procedures, the addition of formic acid improved the extraction rate of hemicellulose. It reached ∼70 mol% by combining the yields of xylose and furfural at 170°C (based on the total original hemicellulose content in birch) with a low-lignin content, which was less than the detection limit in all cases. However, the addition of formic acid also promoted the conversion of hemicellulose to xylose and furfural [104]. Hemicellulose from ground spruce wood was extracted by hot-water extraction with different pH levels adjusted by phthalate buffers at 170°C. The extracted noncellulosic carbohydrates were predominantly composed of galactoglucomannans. Similar yields of noncellulosic carbohydrates were achieved by phthalate buffer solutions, whereas the hydrolysis of hemicellulose and deacetylation of galactoglucomannan was efficiently inhibited. Monosaccharides were reduced by 70%, and the hydrolysis of acetyl group was reduced by 40% [105].

2.4 Other combined process

Besides the above-mentioned procedures, other combined processes such as physical–physical, physical–chemical, and chemical–chemical methods have also been developed and applied in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass to improve the extraction of hemicellulose.

Instant controlled pressure drop technique is a type of hydrothermal process that includes self-expansion of material, in which the moisture in the material is self-vaporized by the influence of the sudden pressure release to vacuum, leading to expansion and texturization of the product. Hemicellulose from poppy stalk was extracted by combining instant controlled pressure drop with alkaline extraction; the extraction yield at 26.23% was obtained and increased by 49.7%. Fractural changes in the morphology of poppy stalks were observed using instant controlled pressure drop, which decreases the consumption of chemicals as well as processing time [106].

Steam explosion was combined with other processes such as chemical and organosolv extraction. A two-stage process combined by sulfuric acid-catalyzed steam explosion with alkali deresination was used to extract hemicellulose from slash pine sawdust, and 90% hemicellulose was recovered at 200°C for 5 min (on mass of dry wood) [107]. The extraction of hemicelluloses from bamboo shavings was performed by Huang et al. [108]. The yield of hemicelluloses at 2.05% (based on the dry dewaxed raw materials) was obtained, which was 5.7-fold higher than that of untreated sample. Two acetylated hemicelluloses, O-acetylated-arabinoxylan (M w of 12,800 g·mol−1) and O-acetylated-(4-O-methyl-glucurono)-arabinoxylan (M w of 11,300 g·mol−1), were achieved by purifying the extracted hemicelluloses. The combination of steam explosion and alkaline impregnation was also used to pretreat lignocelluloses. The extraction of hemicellulose from the alkali-impregnated sugarcane trash and aspen wood sawdust was conducted by using steam explosion, and the maximum yield of xylan reached up to 51%. The xylan extracts were retained in their polymeric and/or oligomeric forms; neither xylose nor furfural (degradation product derived from xylose) was observed in the extracted hemicellulose at the most severe condition of 204°C for 10 min. It can be ascribed to the alkaline impregnation of the raw materials in 5 wt% NaOH aqueous solution prior to its pretreatment with steam explosion. The formation of monomeric xylose and its degradation to furfural was effectively dampened by high alkali loading [109]. The separation of components from wheat straw was conducted by steam explosion followed with organosolv pretreatment. The main components of lignocellulosic biomass were effectively separated, especially for hemicellulose. The yield of hemicellulose reached 22.31% under optimized conditions with the liquor-to-raw ratio of 5.25 at 179°C for 13.6 min using ethanol as an organic solvent [110].

The hemicellulosic fractions were isolated from the mild ball-milled barley straw and maize stem by the combination of the organosolv and alkaline processes. Hemicellulose was extracted by using the sequential extraction with 90% neutral dioxane, 80% acidic dioxane, DMSO, and 8% KOH at 50°C for 4 h, avoiding the delignification step of the conventional isolation procedures. These four successive procedures resulted in dissolution of 94.6 and 96.4% of the original hemicelluloses from barley straw and maize stems, respectively. The composition of the extracted hemicelluloses depended on the solvent used. More branched and comprised arabinoxylan and β-glucan type polymers were obtained in neutral dioxane, whereas a structure composed of a main chain of (1 → 4)-linked β-d-xylopyranosyl residues with a low degree of substitution (DS) of l-arabinofuranosyl and 4-O-methyl-α-d-glucuronic acid linked as the side chains were obtained in acidic dioxane, DMSO, and KOH solutions. In addition, the hemicellulosic polymers contained small amounts of ferulic, p-coumaric acids, and lignin, revealing that the hemicelluloses removed are mostly unbound to the lignin in the cell walls of cereal straws [111].

Polymeric hemicellulose was extracted from a biomass feed consisted of the stem of rapeseed straw using the combination of autohydrolysis with alkaline extraction, giving higher yield of hemicellulose than autohydrolysis, but the molecular weights of the extracted hemicelluloses were similar. Fractions rich in galactoglucomannan by water extraction but primarily xylan by alkaline extraction was yielded. The composition of the extracted hemicellulose could be adjusted by alkaline concentration. Lower concentration of alkali yielded a comparatively high molecular weight mixture of arabinoxylan and galactoglucomannan in more equal proportions [14]. A two-step treatment composed of an autohydrolysis followed by a secondary acid hydrolysis was developed to extract hemicellulose from wood chip without detoxification. Compared with single acid hydrolysis, the extraction recovery of sugar decreased but the degradation of sugar was also inhibited [112].

Some special technology was used for the extraction of hemicellulose. Bokhary et al. [113] reported that the isolation of hemicellulose from the thermomechanical pulping process water and synthetic hydrolyzate using a novel liquid–liquid extraction. The highest extraction rate of 71.03% as well as the highest selectivity was obtained by using n-hexane as solvent. Hemicellulose selectivity coefficient of acidic and alkaline hydrolyzates was higher than the selectivity of the neutral hydrolyzate. The selectivity of the extraction process could be improved by operating in a multistage process to enhance the purity of hemicellulose.

2.5 Comparison in extraction method

Based on the above introduction of hemicellulose pretreatment, several common methods for hemicellulose extraction were compared. The advantages and disadvantages of various pretreatment methods were listed in Table 1. Among them, the alkali extraction is mainly suitable for the extraction of xylan from raw materials of broad-leaved wood and grass. It has the advantages of simple operation, low cost, and suitable for industrial production. Hemicelluloses obtained by organosolv process are generally with more complete structure, which is closer to the original structure of hemicellulose in organisms. It effectively makes up for the defects of alkali extraction. The ultrasonic-assisted and microwave-assisted extractions can improve the environmental pollution of alkali solution and organic solvent separation, as well as effectively shorten the extraction time. However, the ultrasonic-assisted and microwave-assisted extractions are limited to the large-scale industrial production to a certain extent. The most suitable separation and extraction procedure could be selected according to the application area of hemicelluloses.

Method for extracting hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass

| Extraction procedure | Characteristics | Extraction rate | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal extraction | Environmental friendliness, high selectivity and energy consumption, easy degradation of hemicellulose | 40–80% | [5,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] |

| Steam explosion | Green clean, short reaction time, high requirement for equipment, partial degradation, and damage in the structure of hemicellulose | 50–80% | [29,30,31] |

| Alkaline extraction | High extraction rate, purity and DP, and serious pollution | 50–90% | [9,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] |

| Acid extraction | High extraction and degradation rates, lots of by-products and strong corrosion | 70–85% | [51,52,53] |

| Organosolv fractionation | High molecular weight, structural integrity, environmental pollution | 20–97% | [54,55,56,57,58] |

| IL extraction | Environmental friendliness, high-recovery rate, easy recycle of solvent, complex process, and high cost | 20–80% | [61,62,63,64,65,66,67] |

| DES extraction | High extraction rate and structure integrity, low extraction selectivity and purity of hemicellulose, easy preparation and recycle of solvent, green clean | 40–70% | [73,74,75,76,77,78] |

| High-pressure CO2/H2O technology | Environmental friendliness, no requirement for additional catalyst, high temperature and pressure, easy degradation | 45–80% | [84,85,86,87] |

| Ultrasonic-assisted extraction | Mild conditions, high extraction rate and thermal stability, and less degradation and loss of acetyl group | 10–40% | [88,89,90,91,92] |

| Microwave-assisted extraction | Short time, low energy consumption, environmental friendliness, less degradation and loss of acetyl group, lower yield, and molecular weight | 20–40% | [96,97] |

Hemicelluloses with high purity, biodegradability, bioactivity, and biocompatibility extracted from lignocellulosic biomass using various procedures could be applied directly. The extracted hemicelluloses have been widely used to prepare film forming, coating, hydrogel, binder, additive, and functional biopolymer, promising their application in food and drug coating and biodegradable materials. Moreover, it is also possible to provide suitable raw materials for preparing high value-added products by biorefining.

3 Modification of hemicellulose

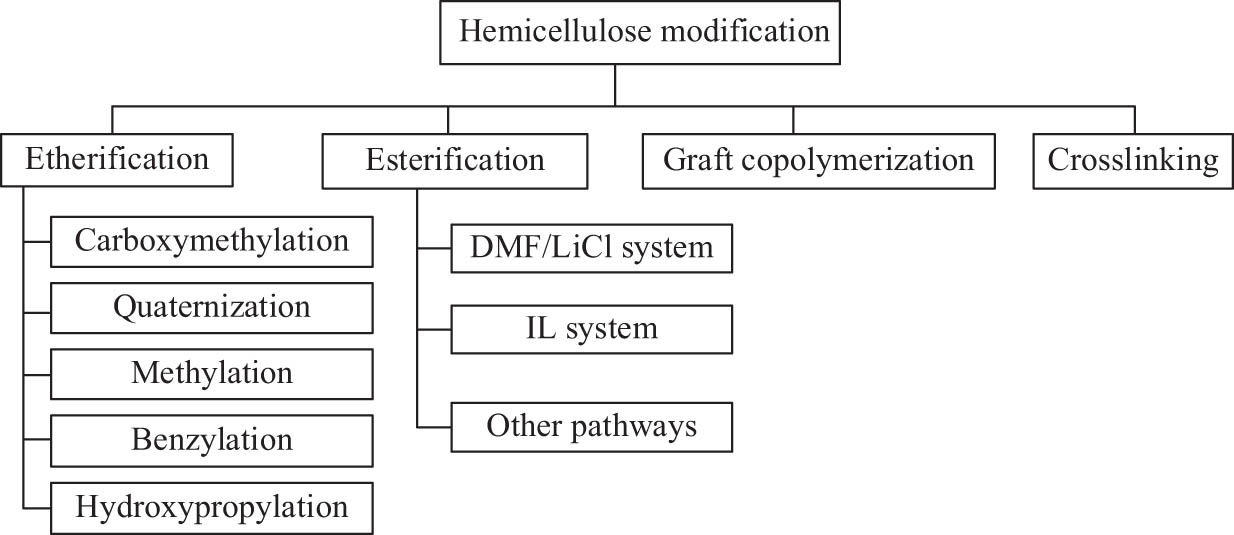

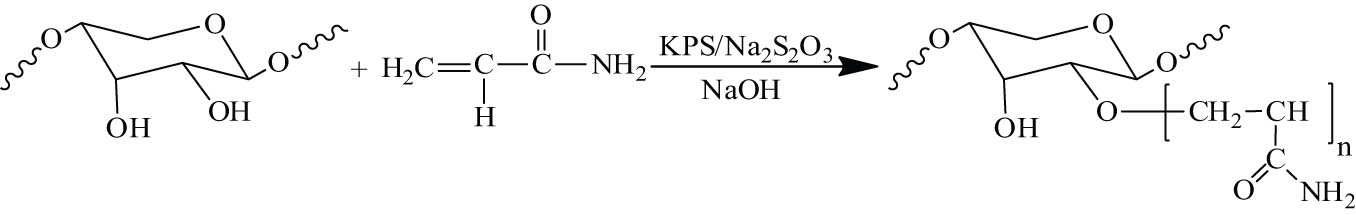

Hemicelluloses have diverse molecular structures with polar hydroxyl groups, resulting in good processability performance including easy hydrolysis and biodegradation and chemical modification. To improve the hydrophobization, solubility, thermal stability, and flexibility of hemicellulose, different functional groups are introduced by using the hydroxyl groups of hemicellulose as the reaction sites [114] via etherification, esterification, graft copolymerization, and cross-linking modification (Figure 2). Accordingly, special characteristics of the derivatives are given, and the application of hemicellulose can be expanded.

The modification of hemicellulose via various methods.

3.1 Etherification

The reaction of hydroxyl groups on the molecular chains of hemicellulose with alkylating reagents in the presence of alkali is defined as etherification of hemicellulose. Alkyl halides such as chloride, bromide and iodide, alkyl sulfonate, and epoxide are typical alkylating reagents [115]. Common etherification reactions include carboxymethylation, quaternization, methylation, benzylation, and hydroxypropylation, which are mainly used to adjust the solubility, enhance biodegradability, and application performance of hemicellulose.

3.1.1 Carboxymethylation

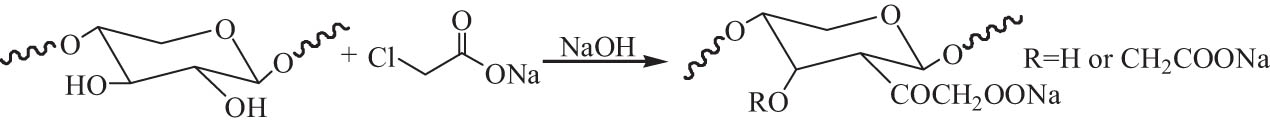

The carboxymethylation of hemicellulose is the reaction of the hydroxyl groups with sodium chloroacetate (ClCH2COONa) in water or water/organic solvent under alkaline conditions, as shown in Scheme 4 [116]. The water solubility of the modified hemicellulose is evidently improved via carboxymethylation.

The carboxymethylation of hemicellulose.

The carboxymethylation of hemicelluloses isolated from sugarcane bagasse was investigated in water/ethanol medium in the presence of ClCH2COONa and NaOH, and the maximum DS of 0.56 was obtained. Although a significant degradation of the polymers occurred during the carboxymethylation, the thermal stability of carboxymethyl hemicellulose was higher than that of the native hemicellulose. At 50% weight losses, the decomposition temperature occurred at 301°C and 324°C for native hemicelluloses and carboxymethyl hemicelluloses, respectively [117]. Hemicellulose isolated from poplar was also converted to carboxymethyl hemicellulose using ClCH2COONa and NaOH. It was found that DS was strongly depended on the dosage of ClCH2COONa and NaOH and temperature. The interaction between ClCH2COONa and NaOH was also confirmed. A higher reaction efficiency of 72% with the maximum DS at 1.08 was obtained in 90% tert-butyl alcohol/water medium at 85°C for 120 min [118]. Carboxymethyl xylan was synthesized in ethanol/toluene, ethanol, and 2-propanol via various procedures. The highest DS of 1.22 was achieved by dissolving birch xylan in 25% NaOH aqueous solution followed by the addition of 2-propanol [119].

The carboxymethylation of hemicellulose has the disadvantages of longer reaction time, high base consumption, and high reaction temperature in the conventional processes [108]. Khalilzadeh et al. [120] investigated a supported alkaline catalyst for the carboxymethylation of hemicellulose. A cheap solid catalyst was developed by supporting KOH on the surface of natural zeolite clinoptilolite. The supported catalyst displayed efficient catalytic performance for the carboxymethylation of hemicellulose. The maximum DS at 0.66 was obtained using 1.25 molar ratio of ClCH2COONa to hemicellulose and 1.5 molar ratio of catalyst to per sugar unit. The reaction efficiency was about two times greater than that of the standard KOH solution, even with shorter reaction time and lower temperature. Furthermore, less degradation of hemicellulose occurred in the presence of supported catalyst.

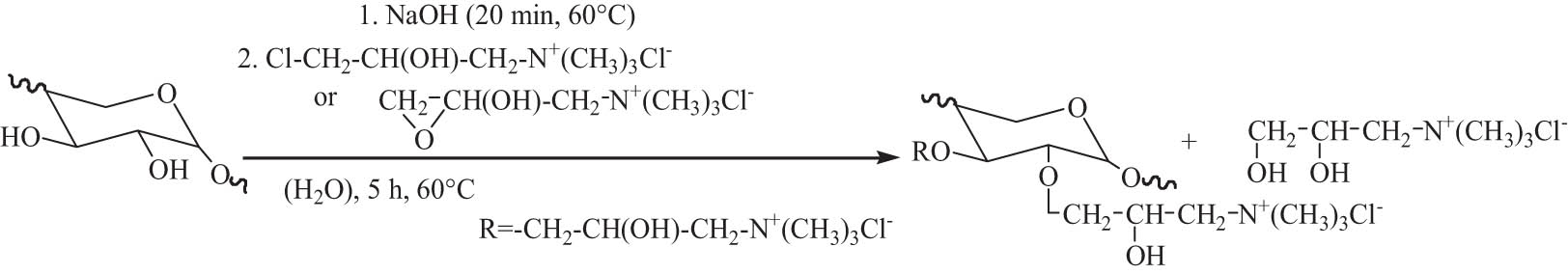

3.1.2 Quaternization

The reaction of hemicellulose with cationic reagent forms cationic polymer or amphoteric polymer, resulting in the quaternization of hemicellulose. Hemicellulose exacted from bamboo was modified by 2,3-epoxypropyltrimethylammonium chloride (ETA) under alkaline conditions. The quaternized hemicellulose was successfully synthesized via the introduction of cationic quaternary ammonium salt group into hemicellulose macromolecule. The as-modified hemicellulose displayed good film-forming performance to prepare organic–inorganic composite membranes [121]. The etherification of hemicellulose from sugarcane bagasse with ETA using NaOH as the catalyst in aqueous solution was investigated. It is confirmed that the alkaline activation was the key step. Etherified hemicellulose with low DS value between 0.14 and 0.33 was achieved by varying reaction conditions. The etherification and quaternization of hemicellulose mainly occurred at C-3 position. After chemical modification, the thermal stability of the modified hemicellulose decreased, and the weight–average molecular weight was lower than that of the native hemicellulose [122]. 2-Hydroxypropyltrimethylammonium chloride hemicellulose from sugarcane bagasse with low degree of functionalization was prepared by the etherification of hemicellulose with 3-chloro-2-hydroxypropyltrimethylammonium chloride or ETA in the presence of NaOH aqueous solution, as shown in Scheme 5. The alkaline activation of the native hemicellulose polymers with NaOH was confirmed to be the most important step. Significant degradation of hemicellulose occurred during the etherification under the alkaline conditions. Both the thermal stability and molecular weight of the etherified hemicelluloses were lower than those of the unmodified hemicellulose polymers. A two-step reaction procedure via the addition of NaOH twice was needed to reduce the degradation of the polymers and improve the efficiency of etherification, enhancing the yield, and DS of the products [123].

The etherification of hemicellulose with two etherifying agents.

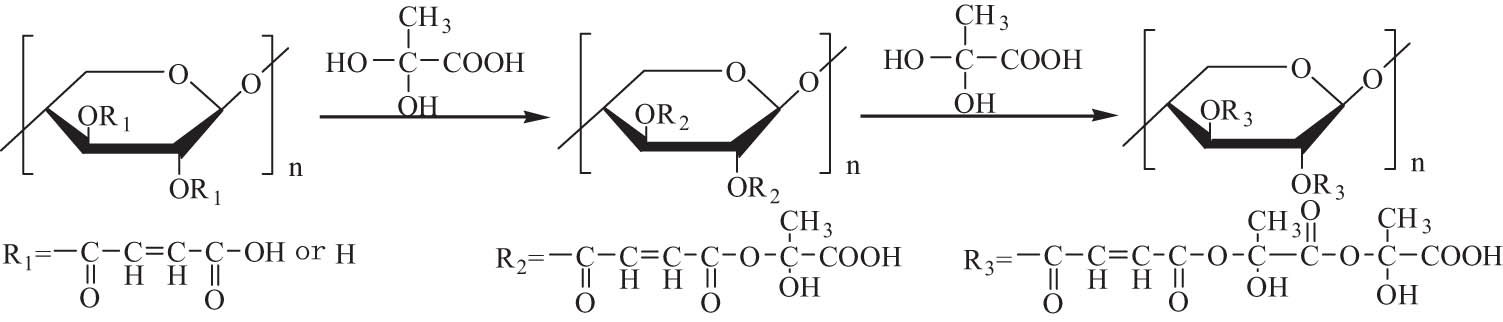

Compared with natural hemicellulose, amphoteric hemicellulose derivatives have lower thermal stabilities and average molecular weights, so they have potential application in the packaging field. Wang et al. [124] investigated amphoteric modification of sugarcane bagasse hemicellulose using cationic and anion modification, sequentially, thus introducing carboxyl and quaternary ammonium into hemicellulose. Better amphoteric-modified products were produced using cationization followed by anionic modification. The structure of the sugarcane bagasse hemicellulose changed, and the thermal stability declined by amphoteric modification. Amphoteric macromolecule was also synthesized by sequential incorporation of carboxymethyl and quaternary ammonium groups into the backbone of xylan-type hemicelluloses using microwave irradiation, as shown in Scheme 6. It was more efficient than conventional heating processes. Under the optimized reaction conditions, the maximum DS of carboxymethyl and quaternary ammonium groups was 0.90 and 0.52, respectively. Both the thermal stability and weight-average molecular weight of the amphoteric hemicellulosic derivatives decreased compared to the native hemicelluloses. The former was ascribed to more hydrogen bonds in the modified hemicellulose, and the latter was resulted from the degradation of hemicelluloses due to prolonging time, elevated temperature, and the action of microwave irradiation.

Reaction scheme of the quaternized carboxymethyl xylan-type hemicelluloses.

Generally, the quaternized hemicellulose has a high DS and solubility. The water solubility and cationic or amphoteric ionic property of hemicellulose increased obviously after quaternization, which favors to expand its application.

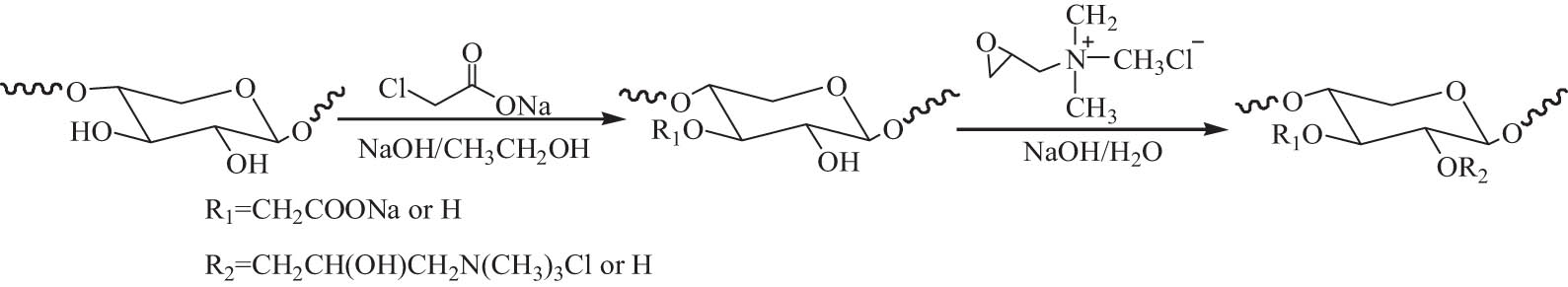

3.1.3 Methylation

The water solubility of hemicellulose could be significantly improved by the methylation. Three different highly value-added functional materials from lignocellulosic biomass were directly synthesized via methylation-triggered fractionation in the presence of tetrabutylammonium fluorid/DMSO without isolating components before modification. The methylated hemicellulose was separated from methylated cellulose and methylated lignin in a one-step reaction. The modified methylated hemicellulose was amphiphilic and possessed similar surface activity to that of industrially produced methylcellulose, indicating that highly value-added functional material of polysaccharide-based surfactant from hemicellulose is feasible [125]. Petzold et al. [126] studied the synthesis of methyl xylan using methyl chloride and methyl iodide as etherifying agents under homogeneous or heterogeneous conditions. The DS values were independent on the reaction system and the ratio of reactants. The maximum DS of 0.94 was achieved by the reaction of xylan with an excess of methyl chloride in 40% aqueous NaOH, whereas DS of about 0.5 was given by the conversion of xylan with methyl iodide in 25% aqueous NaOH.

Fang et al. [127] investigated the methylation of hemicellulose from wheat straw with potassium iodide using NaH as the catalyst, as shown in Scheme 7. The DS of the modified hemicellulose reached 1.7, and the thermal stability was significantly improved after modification.

The methylation of hemicellulose.

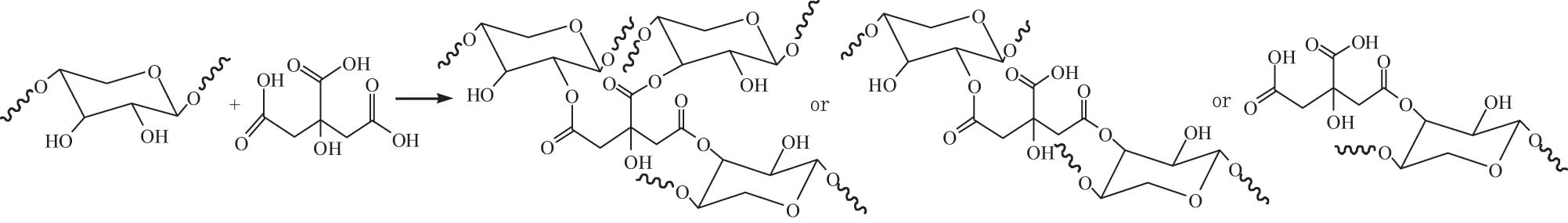

3.1.4 Benzylation

Benzylation is an important method to improve the water resistance of biopolymers, and benzyl chloride is the most common benzyl reagent. Hydrophobic hemicellulose was synthesized by the benzylation of wheat straw hemicellulose with benzyl chloride in an ethanol/distilled water system in the presence of NaOH. Benzyl was grafted onto the main chain of hemicellulose, as shown in Scheme 8. Benzylated hemicelluloses with low DS from 0.09 to 0.35 were obtained, and the thermal stability of benzylated hemicellulose was enhanced. The introduction of benzyl groups endows hemicellulose with hydrophobicity, making benzylated hemicelluloses to be potentially applied in plastic industry [122].

The benzyl reaction of hemicellulose.

3.1.5 Hydroxypropylation

Hydroxypropyl modification is widely used in the alkylation reaction of polysaccharides including hemicellulose, cellulose, and starch. Hemicelluloses were extracted from hardwood and softwood and then modified by 3-butoxy-2-hydroxypropylation via hydroxypropylatio, giving DS values in the range of 0.28–0.73 and 0.2–1.0, respectively. Tunable amphiphilicity of hardwood and softwood hemicelluloses, xylans, and galactoglucomannans was accomplished via controlled etherification [128]. Hemicellulose was etherified by using epoxy chloropropane as the alkylation reagent; the as-prepared hemicellulose was directly extracted and modified from poplar powder by using a one-step method to avoid the destruction of hemicellulose structure by secondary alkali-hydrolysis. The barrier property and thermal stability of etherified hemicellulose films were significantly improved. Moreover, epoxy chloropropane played the role of intermediate, grafting other polymers on the hemicellulose chains by the ring-opening reaction of the epoxy group [129].

3.2 Esterification

Esterification is the reaction of hydroxyl groups on the molecular chain of hemicellulose with acids and/or acid derivatives (e.g., anhydride and acyl chloride) [130]. Hemicellulose derivatives with various DS could be obtained by adjusting the reaction conditions such as material ratio, catalyst concentration, reaction time, temperature, and medium, leading to diverse properties of modified hemicellulose.

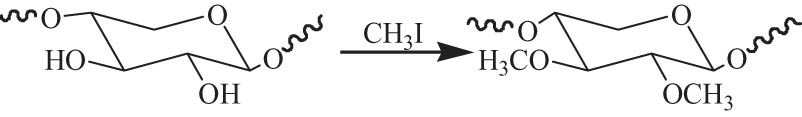

3.2.1 Esterification in DMF/LiCl

DMF/LiCl is the most common homogeneous system of esterification as shown in Scheme 9 [131]. Sun et al. [132] studied the synthesis of hemicellulose acetate by the reaction of native hemicellulose with acetic anhydride under homogeneous reaction conditions in DMF/LiCl using 4-dimethylaminopyridine as the catalyst. More than 80% of hydroxyl groups in the native hemicellulose were acetylated, giving DS in the range from 0.74 to 1.49. Esterification of hemicelluloses from rye straw, poplar chips, and wheat straw with various acyl chlorides was also performed in a homogeneous DMF/LiCl. The DS values of the acetylated hemicelluloses were related to the type of raw materials. The DS values in the range of 0.37–1.65, 0.32–1.51, and 0.38–1.75 were observed, respectively. No significant degradation and hydrolysis of the acetylated hemicellulose were observed during the acetylation. In addition, the thermal stability of the products increased, which is beneficial to expand the application of hemicellulose [133,134,135].

The esterification of hemicellulose.

Esterification of wheat straw hemicellulose with acyl chloride was carried out by microwave irradiation in DMF/LiCl using N-bromosuccinimide as the catalyst. The DS of the esterified hemicellulose reached 1.34 in a few minutes. The esterification reaction occurred preferentially at the C-2 and C-3 positions. Compared with conventional heating processes, microwave irradiation resulted in slight degradation and improvement in the reaction rate. The thermal stability decreased slightly, whereas there was negligible change in the chemical structure of the hemicellulose derivatives [136].

3.2.2 Esterification in IL

IL could be effectively recovered and reused after the reaction, which is of great significance for the development of environmentally friendly modification of hemicellulose. The esterification of hemicellulose in IL has been widely investigated, and 1-butyl-3-methylimidzolium chloride ([Bmim]Cl) was mostly used. Wheat straw hemicellulose was acetylated with acetic anhydride in [Bmim]Cl using iodine as the catalyst. Both the yield and DS of the acetylated hemicellulose depended on the reaction temperature and duration, the dosages of catalyst, and acetic anhydride. About 83% hydroxyl groups in the native hemicellulose were acetylated, giving yield of 90.8% and DS of 1.53, respectively. The thermal stability of the acetylated products increased upon chemical modification. The procedure has obvious advantages in that the reaction was more rapid and complete, and the reaction medium of IL can be recycled [137]. Hemicellulose extracted from switchgrass was acetylated by acetic anhydride in [Bmim]Cl with a complete homogeneous procedure without a catalyst. The derivatives of hemicellulose with high DP around 450 and tunable DS in the range from 0.03 to 1.25 were produced by varying reaction temperature and time. In addition, the thermal stability, hydrophobicity, and solubility were improved by acetylation [138]. The detailed reaction behavior of hemicellulose was investigated using homogeneous esterification of bagasse with phthalic anhydride in [Bmim]Cl. The phthalation degrees of the isolated hemicellulose ranged from 16.37% to 52.15%. The reaction priority on the main and side chains of hemicelluloses was revealed by the changes of monosaccharide contents upon phthalation. The side chains of hemicellulose were more easily phthalated than the main chains, and the phthalation of secondary hydroxyl groups on uronic acids was more difficult than that on neutral sugars. The reactivity of the secondary hydroxyls at C-2 and C-3 positions in anhydroxylose units was almost similar [139].

Homogeneous acetylation of hemicellulose from soy sauce residue in imidazolium-based IL was investigated. The DS values of the acetylated hemicelluloses varied in the range from 0.67 to 1.68. More than 90% hydroxyl groups in hemicellulose were acetylated, giving a 93.8% yield with short reaction time of 20 min. The thermal stability and the water-contact angle increased with increase in DS [140]. The homogeneous esterification of xylan-rich hemicellulose with maleic anhydride was carried out in [Bmim]Cl using LiOH as the catalyst. A functional biopolymer with carbon–carbon double bond, carboxyl group, and DS in the range from 0.095 to 0.75 was obtained. The thermal stability of the modified hemicellulose was lower than that of native xylan-rich hemicellulose [141].

3.2.3 Other esterification

The esterification of hemicellulose in other pathways has also been developed. Xylan isolated from corn cob by alkaline extraction was sulfated using chlorsulfonic acid-pyridine. The sulfated polysaccharide with an average molecular mass of 13,000 g·mol−1 and DS of 2.24 was achieved at 65°C for 6 h [125]. The esterification of hemicelluloses with vinyl benzoate was also investigated in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate to obtain different DS values and weight percent gain (WPG). Hemicellulose was converted into a crystal state with adjustable transition temperature, and the solubility of benzoated-functional hemicellulose increased, whereas the thermal stability decreased. The DS and WPG could be controlled well by stoichiometric method, obtaining a DS of 1.43 and WPG of 127.60% [120]. Mugwagwa and Chimphango [142] investigated the esterification of hemicelluloses isolated from wheat straw via an alkali-based organosolv pretreatment process in the presence of acetic anhydride and H2SO4. The acetylation performance of hemicellulose can be manipulated by controlling the hemicellulose composition and side group content.

3.3 Graft copolymerization

The polymerization is the reaction of the active hydroxyl groups at the end of the hemicellulose molecular chain with grafting monomers, such as acrylonitrile, methyl acrylate, and acrylamide, in the presence of initiator [71], in which new functional groups are introduced into the polysaccharide molecular chain to improve its performance [143].

Cerium ammonium nitrate is a common initiator for graft copolymerization of hemicellulose. The grafting polymerizations of acrylonitrile onto both a commercial larchwood hemicellulose and a purified-wheat straw hemicellulose were initiated by ceric ammonium nitrate. The resulting hemicellulose–g-polyacrylonitrile (PAN) copolymers with similar performance to a starch-based absorbent were fractionated by DMF and DMSO extraction at room temperature. The saponification of PAN component of hemicellulose–g-PAN gave a water-dispersible graft copolymer with good thickening properties for water systems [144]. The graft copolymerization of hemicellulose with acrylamide and methacryloyloxy ethyl trimethyl ammonium chloride in the alkaline peroxide mechanical pulping effluent was investigated by using the Fenton agent (FeSO4/H2O2) as initiator. The thermal resistance properties and molecular weight of the graft copolymer were increased, whereas the polydispersity value decreased by chemical modification of hemicellulose, implying that the graft copolymer was more homogeneous and had better application performance [145].