Abstract

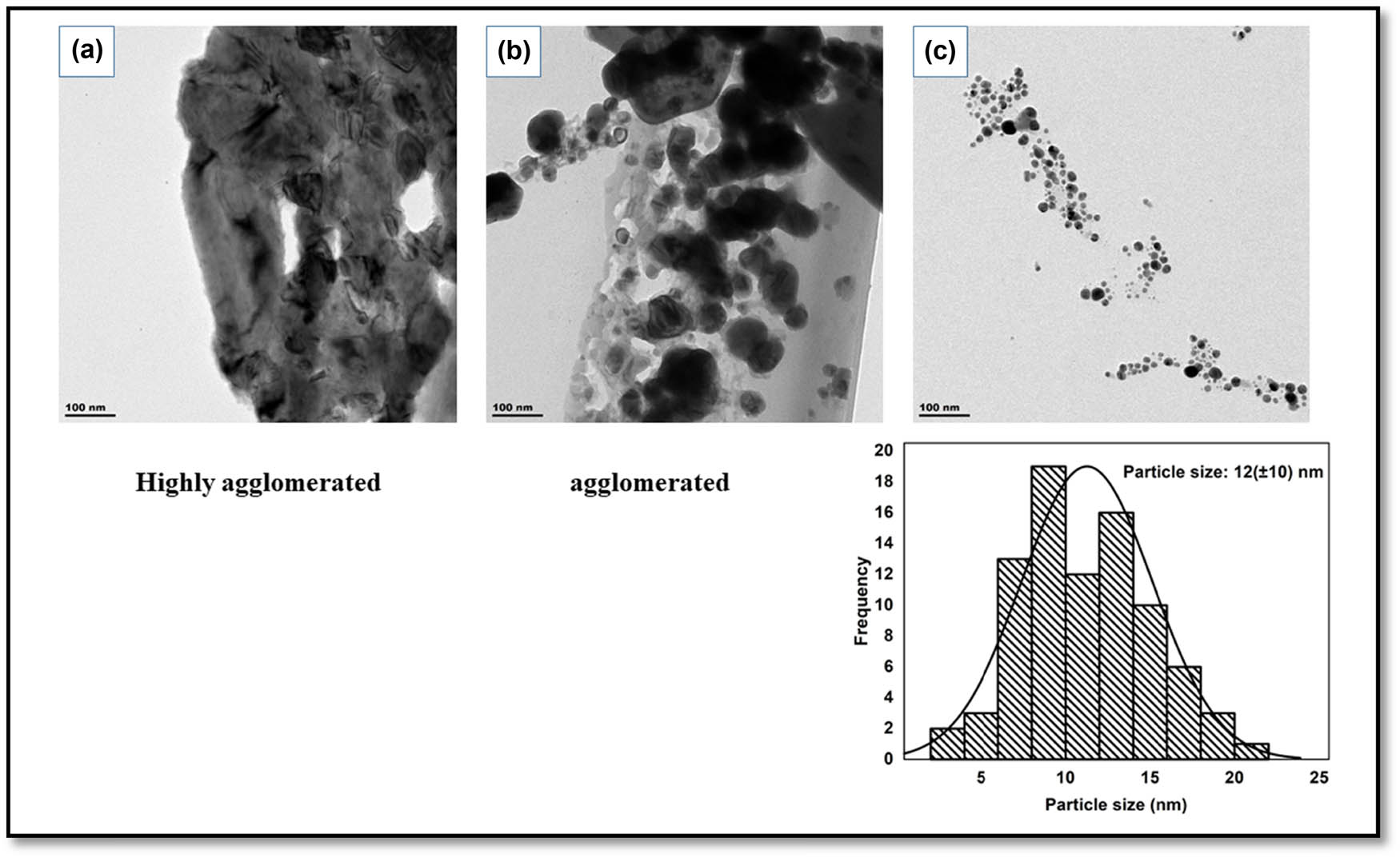

The resistance of microorganisms towards antibiotics remains a big challenge in medicine. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) received attention recently for their characteristic nanosized features and their ability to display antimicrobial activities. This work reports the synthesis of AgNPs using the Citrus sinensis peels extract in their aqueous, mild, and less hazardous conditions. The effect of concentration variation (1%, 2%, and 3%) of the plant extracts on the size and shape of the AgNPs was investigated. The antimicrobial activities were tested against gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae. Absorption spectra confirmed the synthesis by the surface Plasmon resonance peaks in the range 400–450 nm for all the AgNPs. FTIR spectra confirmed that Citrus sinensis peels extract acted as both reducing and surface passivating agent for the synthesized AgNPs. TEM revealed spherical AgNPs with average size of 12 nm for 3% concentration as compared to the agglomeration at 1% and 2%. All the AgNPs synthesized using Citrus sinensis peels extracts (1%, 2%, and 3%) exhibited antimicrobial activity against both gram-positive and negative bacteria. These results indicated a simple, fast, and inexpensive synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the Citrus sinensis peels extract that has promising antibacterial activity.

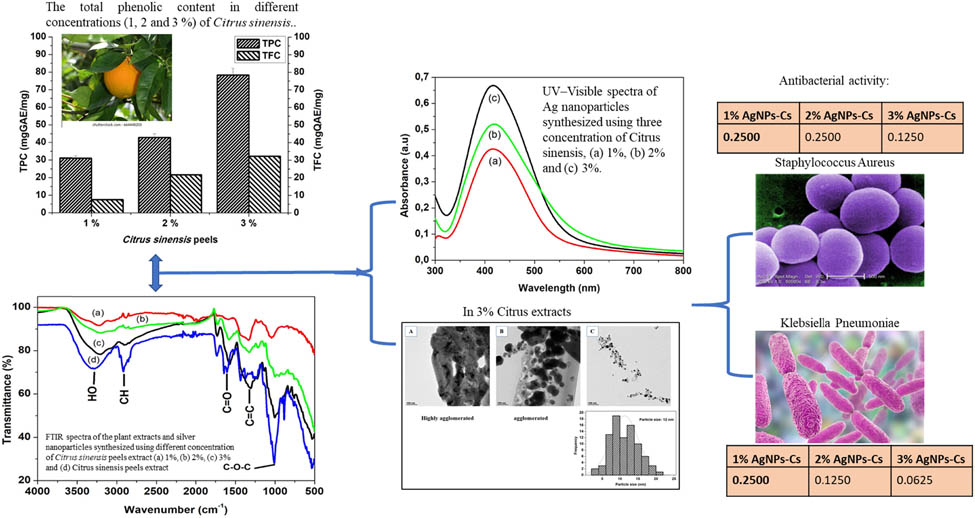

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The resistance of microorganisms towards commonly used antibiotics continues to pose a threat towards the public health. Insufficient sanitation and inadequate medical facilities are among many other factors that cause microorganism such as Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae to become resistant. Some metals in their nanoscale have been reported as promising solutions to overcome the problem of resistant microorganisms and this is due to their high antimicrobial efficiency [1,2].

The science that deals with the preparation of materials in their nanoscale (1–100 nm) is known as nanotechnology [3,4]. Decreasing the size of the material to its nanoscales improves its optical, electrical, and biological properties, thus justifies its use in different fields such as physics, medicine, organic, and inorganic chemistry. Metals such as silver, platinum, and gold in their nanoscale have been reported to have health benefits compared to their bulk material [1,5]. These materials are used in catalysis and sensor technology [6]. Silver nanoparticles, specifically, are extensively applied in many fields due to their unique properties such as thermal, electrical conductivity, and antimicrobial activities [7]. Different methods such as chemical reduction, electrochemical changes, and photochemical reductions can be used to prepare nanoparticles. The selection of the method of preparation of nanoparticles is of importance since factors such as the interaction between the metal ion and the reducing agent as well as the interaction between the nanoparticles and the stabilizing agent have an influence on the size, shape, stability, and the physicochemical properties of the nanoparticles formed [8,9]. Physical methods used to prepare nanoparticles such as milling are not cost-effective since they require high amount of energy; furthermore, chemical methods are not eco-friendly since they often require toxic chemicals as starting material and also release toxic or hazardous chemicals, leaving the environment devastated [10]

Green chemistry, on the other hand, focusses on the elimination or minimization of the usage of toxic chemicals. This method is based on the preparation of silver nanoparticles using plants, bacteria, and fungi. The usage of plants when synthesizing silver nanoparticles is considered advantageous since the plants are easily accessible. The method does not require any preparation of culture and any isolation technique. The method is thus considered cost-effective [11,12]. Approximately 140 million of the citrus fruits are produced annually worldwide, thus considered one of the important fruits. Citrus sinensis, commonly known as the orange fruit, accounts for about 70% of the produced citrus species. Citrus sinensis is often consumed as fresh fruits or used to make orange juice, and after consumption, the peels, which contribute to about 50% of the mass of the fruit, are discarded [13,14].

Orange peels also contain compounds such as phenolic and flavonoids that have been reported to have human health benefits such as antimicrobial and antioxidant activities [15]. The following compounds can also act as potential reducing and capping agents for the synthesis of stabilized silver nanoparticles [16,17]. Hence, the work is reporting on the antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using orange peels.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Chemicals and reagents

Silver nitrate, folin ciocalteu reagent, gallic acid, aluminium chloride, ammonia, quercetin, methanol, sodium carbonate, and sodium hydroxide were all purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Nutrient broth, Muller Hinton Agar, and the bacteria culture were acquired from the Biotechnology laboratories, Vaal University of technology, South Africa.

2.2 Plant extract preparation

The Citrus sinensis fruits were purchased from a local supermarket, Pick n Pay stores in South Africa, Gauteng province, Vanderbijlpark, during the 2019 winter season. After peeling the fruits, the Citrus sinensis peels were air dried, ground to fine powder using a grinder, and lastly the powder obtained after grinding was passed through the 350 μm sieve. Different concentrations (1%, 2%, and 3%) of the plant extracts were prepared by mixing 1, 2, and 3 g of the Citrus sinensis plant with 100 mL double distilled water and allowed to stir for 40 min under constant stirring at 50°C. The mixture was allowed to cool, filtered using the Whattman No 1 filter paper, and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min to remove the unwanted material. The supernatant was stored at 4°C until the experiments were conducted.

2.3 Determination of the total phenolic content

The total phenolic content in the Citrus sinensis peels was evaluated using the folin ciocalteu assay and gallic acid was used as a standard solution (between 30 and 210 ppm). Briefly, 0.5 mL of the plant extract was mixed with 0.5 mL folin ciocalteu reagent. This was followed by adding 8.5 mL distilled water. UV-Vis spectroscopy was used to measure the absorbance at 725 nm. The concentration of the total phenolic content in the plant extract was calculated from the standard curve (y = 0.1180x − 0.058, r 2 = 0.998). The total phenolic content was expressed as gallic acid equivalent [18].

2.4 Determination of the total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid in the increasing concentration (1%, 2%, and 3%) in the Citrus sinensis was determined using the aluminium chloride method calorimetric method. Briefly 0.5 mL of the extract was mixed with 10% aluminium chloride prepared in methanol and this was followed by addition of 0.1 mL of 1 M potassium acetate. The mixture was allowed to stand for 60 min and the absorbance was measured at 510 nm. Quercetin was used to prepare the calibration curve and the results were expressed as mg quercetin equivalent per g dry weight [19].

2.5 Synthesis of silver nanoparticles

A solution of 0.15 M AgNO3 was prepared in 20 mL ultra-pure water. The silver nitrate solution was transferred into a 250 mL three neck flask followed by the addition of 40 mL Citrus sinensis aqueous extract (1%). Ammonia solution was added drop-wise to adjust the pH to 10 to activate the hydroxyl groups. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, thereafter it was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 20 min. The synthesized silver nanoparticles were re-dispersed in methanol and centrifuged to remove impurities. Finally, silver nanoparticles were collected, dried at room temperature, and characterized. Silver nanoparticles capped with 2% and 3% Citrus sinensis were synthesized using the same method.

2.6 Characterization

Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer Lambda 25) was used to study the optical properties of the synthesized silver nanoparticles. Samples were analysed using double distilled water (1 mg·mL−1) transferred into a 1 cm path length cuvettes and scanned from 200 to 1,000 nm. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 400 FT-IR) was used with samples placed on the diamond sample holder and subjected to the infrared radiation measured in the region of 300–4,000 cm−1. JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope was used to study the morphology of the Ag nanoparticles. Samples were prepared by dispersing the Ag nanoparticles in distilled water, placed on a copper grid, and dried under the infrared lamp. X-ray diffraction (FEI TECNAI SPIRIT) secondary graphite monochromatic Co K alpha radiation (l = 1.7902 Å) was used to study the crystallinity nature of the powdered silver nanoparticles. The scattered radiation was detected in the range 2θ = 10–60° at a scan rate of 2°·min−1.

2.7 Antimicrobial activity: minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The antibacterial activity of the synthesized silver nanoparticles using different concentrations of Citrus sinensis (1%, 2%, and 3%) was tested against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, namely S. aureus and K. pneumoniae, respectively. MIC was carried out to evaluate the lowest concentration of the silver nanoparticles required to prevent visible growth of the microorganisms. Neomycin was used as positive control, while water extract was used as a negative control. Briefly, in this test, a multichannel pipette was used to pour 100 µL of the prepared Mueller Hinton broth into all the wells of the 96 well plate; this was followed by addition of 100 µL of the silver nanoparticles (1 mg·mL−1) into the first row of the 96 well plate. Serial dilution of the silver nanoparticles/neomycin was done by taking 100 µL of the solution in the first row and transferring it into the second row of the plate and taking the 100 µL of the solution in the second row and transferring it into the third row; this dilution was carried out until the last row of the 96 well plate to prepare decreasing concentration solution of the silver nanoparticles. 100 µL of the prepared microbial (S. aureus/K. pneumoniae) suspension (1 × 106 Cfu·mL−1) was added in all the wells of the 96 well plates. Lastly, 50 µL of the 0.2 mg·mL−1 of the p-iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (INT) was added also in all the wells of the plate as an indicator. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and activity was recorded as the blue colouration [16].

2.8 Statistical analysis

Methods 2.3, 2.4, and 2.5 were carried out in triplicates and the representative data are presented here expressed as means ± standard deviation.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Total phenolic and flavonoid content

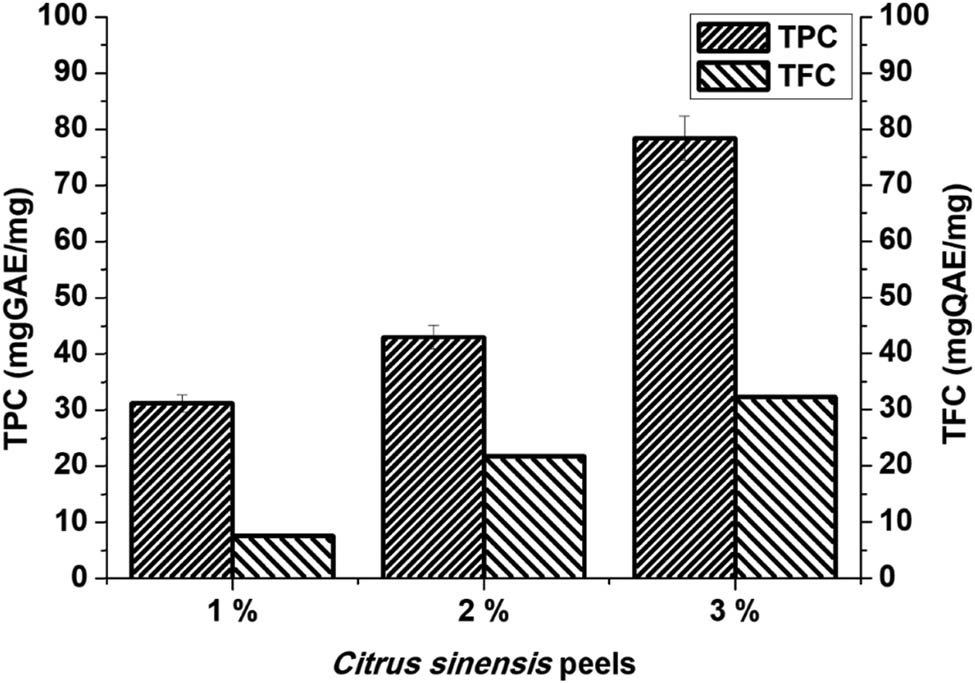

The total phenolic and flavonoid contents of Citrus sinensis extracts are shown in Figure 1. The total phenolic content ranged from 31 to 78 mg·GAE·mg−1 and the flavonoid content ranged between 7 and 32 mg·QAE·mg−1. The highest concentration for both phenols and flavonoids was 3% extract. Thus, the extract can be used both as reducing and stabilizing agent for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles compared to the 1% and 2%. Soto et al. [20] evaluated the total phenolic content in the orange peels extract with total phenolic content of 146.6 GAE per g and similar results were obtained in this study. Jridi et al. [21], furthermore, analysed both the total phenolic and flavonoid content in the dried orange peels extracts with the amounts 8.86 and 6.30 GAE per g, respectively. These results are different to the current study, and this can be attributed to several factors such as the climate, seasons, and geographical conditions of the locations [22].

The total phenolic content in different concentrations (1%, 2%, and 3%) of Citrus sinensis. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3).

3.2 UV-Visible spectral analysis

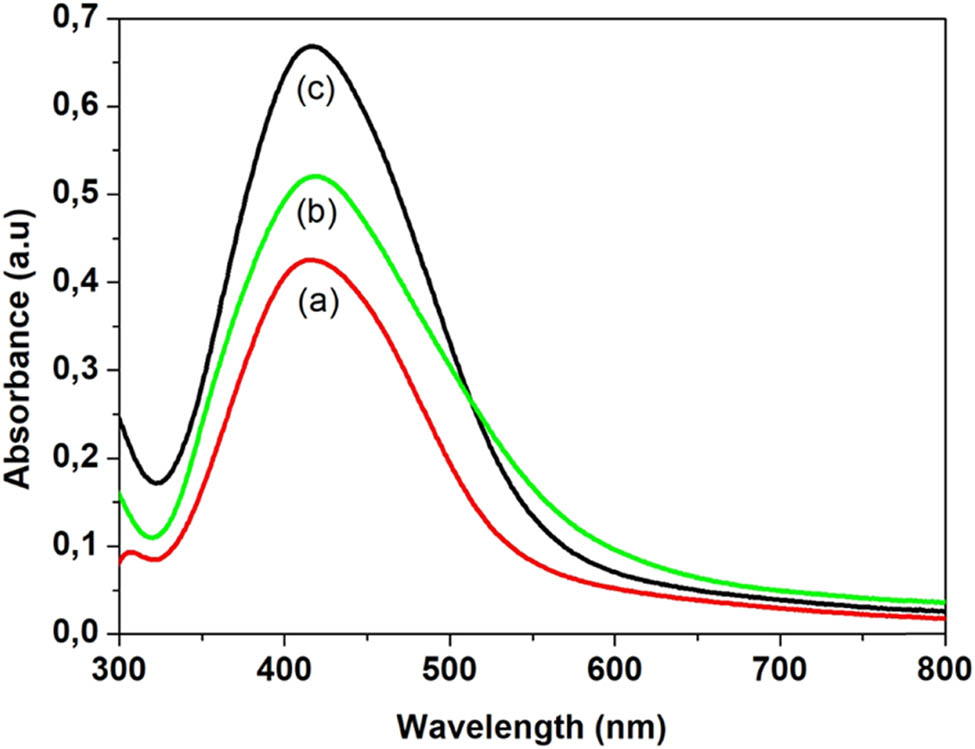

Figure 2 shows the UV-Vis spectra of silver nanoparticles synthesized using the increasing concentration (1%, 2%, and 3%) of Citrus sinensis extracts. A colour change of yellow to dark brown was observed at pH 10 when both the Citrus sinensis and the silver nitrate were mixed. This illustrates successful reduction of Ag+ ions to produce silver nanoparticles [6].

UV-Vis spectra of Ag nanoparticles synthesized using three concentrations of Citrus sinensis: (a) 1%, (b) 2%, and (c) 3%.

All the samples showed the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band which is a characteristic for all noble metals including silver [23]. The SPR peaks for the three concentrations occurred at the same wavelength of approximately 420 nm. The position of the SPR band gives more information about the shape and size of the synthesized silver nanoparticles, and according to the results, the SPR bands shifted to lower wavelengths compared to the bulk material which absorbs at a wavelength of 1,000, thus showing a decrease in particle size [24].

3.3 FT-IR spectroscopic analysis

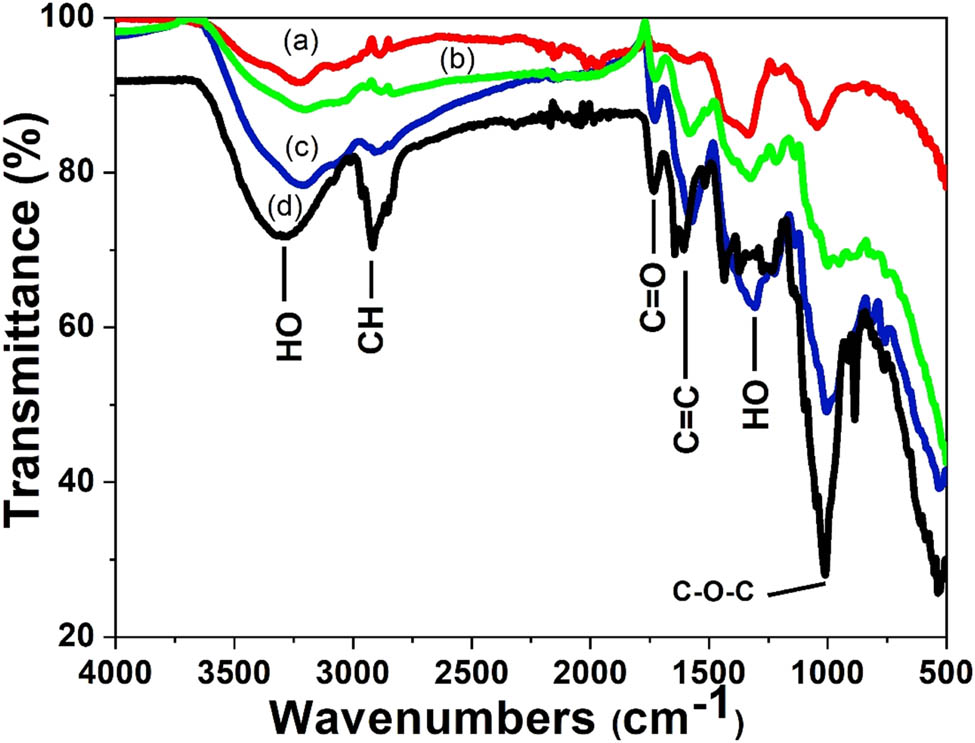

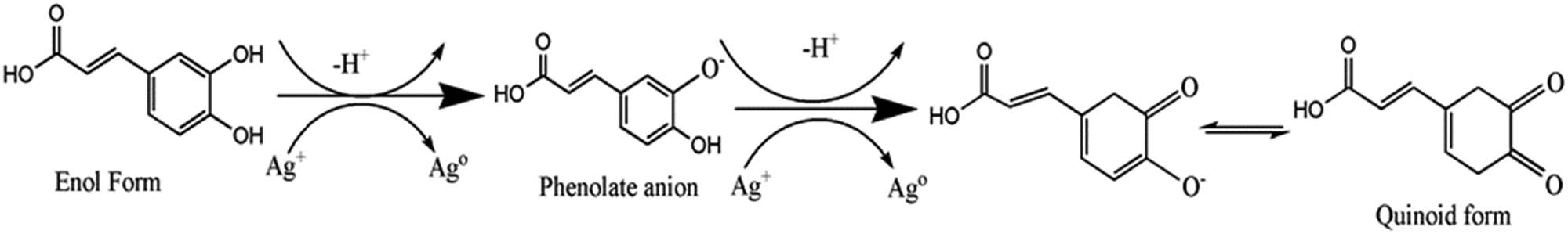

FTIR spectroscopy was also used to confirm the functional groups involved in both the reduction of the silver ion and the stabilization of the silver nanoparticles from the peels. Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of the aqueous extract of the Citrus sinensis peels and the synthesized nanoparticles using different concentrations of the aqueous extract. Table 1 shows “the summary of FTIR spectral data for the Citrus sinensis peels extract and the silver nanoparticles that were synthesized by varying concentration of the extracts”. The band at 3,400 cm−1 is due to the presence of OH band of the phenolic compounds and carbohydrates; the band at 2,900 cm−1 is due to the CH band of the stretching vibration of the aliphatic hydrocarbons chains, either from the methylene or methyl group from the lipids in the aqueous extract. The band at 1,700 cm−1 is due to the C═O stretch vibration of the phenolic compounds in the aqueous extracts such as aromatic alkenes. The band at 1,400 cm−1 is a characteristic of the aliphatic chains such as the –CH2 and –CH3. The strong peak at 1,010 cm−1 is due to the C–O stretching vibration and the band at 900 cm−1 is attributed to the OH bonding. The FTIR spectra of the three different concentrations of the Citrus sinensis peels extract with nanoparticles were similar to those of the free aqueous extract. However, the OH band in the nanoparticles synthesized using increasing concentration of the extract was found to have shifted to lower frequency with some distortion. This signifies the interaction between the OH group and the Ag+/Ag0. The peak at around 1,700 cm−1 which can be attributed to C═O was found to increase in intensity as the concentration of the extracts was increased from 1% to 3%. This was due to the enhanced availability of the carboxylate group, also shown in Figure 1, where 3% of the extract showed higher phenolic and flavonoid content and 1% showing the least [2]. The results described above suggests that the orange peels extracts contain biomolecules with functional groups such as the O–H and COOH [3]. These functional groups are responsible for the reduction of the Ag+ to Ag0; also, they act as stabilizing agents [9]. Scheme 1, given below, shows the proposed mechanism in which the silver ion (Ag+) interacts with the biomolecules. Briefly, the electron is released from an enol of a phenolic compound. The electron released during the breaking of the H from the –OH bond reduces the Ag+ to Ag0 which is the silver nanoparticle. The shift in –OH, which peaks in the FTIR spectra, confirms the proposed mechanism [7].

FTIR spectra of the plant extracts and silver nanoparticles synthesized using different concentrations of Citrus sinensis peels extract (a) 1%, (b) 2%, (c) 3%, and (d) Citrus sinensis peels extract.

The summary of FTIR spectral data for the Citrus sinensis peels extract and the silver nanoparticles that were synthesized by varying concentrations of the extracts

| Functional groups | Citrus sinensis peels extract wavenumber (cm−1) | 3% AgNPS-CSP wavenumber (cm−1) | 2% AgNPS-CSP wavenumber (cm−1) | 1% AgNPS-CSP wavenumber (cm−1) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH | 3,311 | 3,235 | 3,203 | 3,202 | [4] |

| CH | 2,926 | 2,919 | 2,913 | 2,897 | [5] |

| C═O | 1,740 | 1,732 | 1,726 | [4,6] | |

| C═C | 1,648 | 1,621 | 1,625 | 1,611 | [7] |

| –C–H or –CH3 | 1,440 | 1,427 | 1,422 | 1,415 | [8] |

| C–O–H or C–O–R | 1,010 | 990 | 1,011 | 1,066 | [9] |

Proposed mechanism for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the extract of Citrus sinensis peels.

3.4 Transmission electron microscopic analysis

The morphology of the synthesized nanoparticles was evaluated using the transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM images of the silver nanoparticles using the different concentrations of Citrus sinensis are presented in Figure 4. According to Figure 4a and b, the synthesized nanoparticles were agglomerated with those synthesized using 1% Citrus sinensis peel extract being the most agglomerated. The silver nanoparticles synthesized using 3% Citrus sinensis were found to be polydispersed and spherical (Figure 4c), with a particle size distribution from 5 to 25 nm and average diameter of 12 (±10.3) nm. Thus, as the concentration of the Citrus sinensis peels increased, the agglomeration decreased. The synthesized nanoparticles in this study were found to have smaller particle size compared to other similar studies [25] of synthesized silver nanoparticles using the Citrus unshiu, where the average particle size was found to be 20 nm. Majumdar et al. [26] reported the synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Citrus macroptera extract and their observed TEM images displayed particles with an average particle size of 16 (±2.96) nm.

TEM images of silver nanoparticles (a–c) synthesized using different concentrations of Citrus sinensis 1%, 2%, and 3%, respectively, and particle size distribution of silver nanoparticles synthesized using 3% Citrus sinensis.

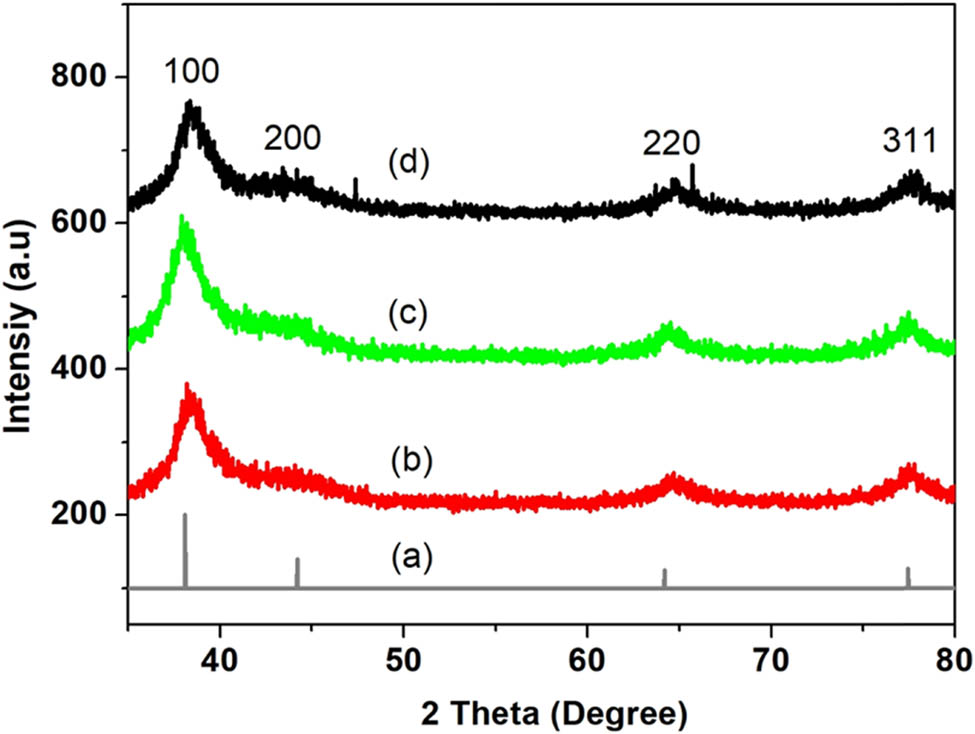

3.5 XRD analysis

XRD spectroscopy was used to study the crystallinity of the synthesized nanoparticles and their structures. Figure 5 shows the XRD patterns of the silver nanoparticles synthesized using the different concentrations of Citrus sinensis. According to the Figure 5, four diffraction peaks with 2θ values were observed at 38°, 44°, 64°, and 80°, respectively. The diffraction peaks can be indexed to 111, 200, 220, and 311 planes (JCPDS file No. 04-0788) which confirmed the formation of silver nanoparticles. Samrot et al. [27] and Konwarh et al. [28] reported similar characteristic peaks when they synthesized silver nanoparticles using edible fruits and most specifically Citrus sinensis peels extracts. The XRD patterns were used to confirm the average particle sizes of silver nanoparticles as 5.3, 5.1, and 4.9 nm for the respective 1%, 2%, and 3% concentrations used. This gave a slight decrease in size as the concentration is increased showing an influence on the extracts used to prepare nanoparticles. The calculated average particle size from the TEM images (Figure 4c) confirmed the presence of small particle size with an average of 5 nm, whereas the lower percentages generally displayed some degree of particle agglomeration.

XRD diffraction patterns of silver nanoparticles synthesized using different concentrations of Citrus sinensis (a) reference spectrum of silver (b) 1%, (c) 2%, and (d) 3% of AgNPs.

3.6 Antimicrobial activity of the synthesized nanoparticles

The antimicrobial activity of the synthesized nanoparticles was evaluated using MIC which is defined as the minimum concentration of the sample required to inhibit growth against the tested microorganisms. The synthesized nanoparticles (AgNPs 1%, 2%, and 3%) were tested against gram-negative K. pneumoniae and gram-positive S. aureus; neomycin was used as a positive control. Table 2 showed the results of antimicrobial activity from the percentages of silver nanoparticles used against the species, K. pneumoniae and S. aureus. This is due to silver nanoparticles’ ability to affect both the chemical and physical properties of the cell walls and cell membranes. This is achieved by the nanoparticles attaching themselves onto the cell which is negatively charged, and as a result, disturbs the important functions such as respiration and osmoregulation [3]. Further on, the synthesized nanoparticles cause damage within the bacteria cell wall by interacting with proteins and DNA after they permeate the bacteria cell wall [29].

Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using different concentrations of Citrus sinensis peels extract

| Test organisms | Silver nanoparticles (mg·mL−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% AgNPs-Cs | 2% AgNPs-Cs | 3% AgNPs-Cs | Neomycin | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0.2500 | 0.2500 | 0.1250 | 2.5000 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0.2500 | 0.1250 | 0.0625 | 0.6250 |

The synthesized nanoparticles and the neomycin which was used as a positive control were found to have higher antimicrobial activity against gram-negative K. pneumoniae compared to the gram-positive S. aureus. Logeswari et al. [7] also reported a similar trend when they synthesized silver nanoparticles using the Citrus sinensis peels extracts; their silver nanoparticles gave higher antimicrobial activity against gram-negative K. pneumoniae compared to the S. aureus. The high activity that was observed against the gram-negative bacteria was attributed to the cell wall. Gram-negative bacteria are known to have thinner walls as compared to the gram-positive bacteria, thus are easier to permeate [30,31]. On the other hand, silver nanoparticles cannot easily permeate and interact with gram-positive bacteria S. aureus due to the rigid structure that results from the thick peptidoglycan which consists of peptides cross-linked together giving linear and chains of polysaccharides [32]. The synthesized silver nanoparticles gave better activity compared to the neomycin that was used as a positive control. The difference in activity was caused by smaller size and high surface area of silver nanoparticles. Therefore, they have a higher adsorption capacity and thus are more likely to interact with biomolecules [3,10]. According to Table 1 above, 3% Ag nanoparticles gave the lowest MIC values of 0.06250 and 0.1250 mg·mL−1 against K. pneumoniae and S. Aureus, respectively. However, 1% Ag nanoparticles gave 0.2500 mg·mL−1 for both the K. pneumoniae and S. aureus. The high antimicrobial activity that was observed with 3% AgNPs was due to the small size of the silver nanoparticles as shown in the TEM images in Figure 4 compared to the other silver nanoparticles that were synthesized using 1% and 2% AgNPs and were found to be agglomerated [33]. Smaller nanoparticles are known to have high surface area and thus can easily interact with the cell, permeate, and destroy the cell [34]. The reported results by Logeswari et al. [7] obtained particles with an average size of 65 nm from the similar plant species based in a different environment than the peels used in this study. The extracts did not perform as well as compared to species, S. tricobatum and O. tenuiflorum. These produced highest antimicrobial activity of Ag nanoparticles from the S. tricobatum and O. tenuiflorum against S. aureus (30 mm) and E. coli (30 mm), respectively.

4 Conclusion

This study showed green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using increasing concentration of Citrus sinensis peels extract (1%, 2%, and 3%). The Citrus sinensis peels were found to contain significant amount of phenols and flavonoid content, which are phyto-constituents that are responsible for the reduction of Ag1+ to Ag0 and for capping and stabilizing silver nanoparticles. XRD indicated that the average crystallite sizes (about 5 nm) showed an insignificant decrease of 0.2 nm as the concentration of the peels extracts increased from 1% to 3%. The Citrus sinensis extract concentrations did not influence the crystallite size. UV-Vis spectroscopy showed that the synthesized AgNPs exhibited a surface Plasmon resonance which is a characteristic peak for AgNPs particles. FTIR showed the presence of biomolecules that might be responsible for the reduction of the silver ion and stabilizing of the silver nanoparticles during the synthesis of AgNPs. TEM showed that 3% Citrus sinensis gave non-agglomerated spherical-shaped silver nanoparticles with an average size of 12 nm and further showed that, as the concentration of the Citrus sinensis decreased from 3% to 1%, the particles became more agglomerated. All the synthesized AgNPs showed antimicrobial activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The synthesized AgNPs can be used as a potential antimicrobial agent even at lower concentration of extracts.

-

Funding information: This work was supported financially by the National Research Foundation (NRF) South Africa grant No: 120863.

-

Author contributions: Lebogang Mogole: writing – original draft, data – collection, writing – review and editing, methodology, formal analysis; Wesley Omwoyo: writing – original draft, formal analysis, assisted in project administration; Elvera Viljoen: provided support for the XRD analysis and reviewed the manuscript, purchased some of the reagents; Makwena Moloto: principal researcher, formulation of the research concept, provided budget and resources for research, assisted in data interpretation, reviewed the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All the necessary data have been provided in the manuscript, but any extra or additional information can be made available upon request.

References

[1] Magiorakos A, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–81.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Panáček A, Kvítek L, Smékalová M, Večeřová R, Kolář M, Röderová M, et al. Bacterial resistance to silver nanoparticles and how to overcome it. Nat Nanotechnol. 2018;13:65–71.10.1038/s41565-017-0013-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Sharma VK, Yngard RA, Lin Y. Silver nanoparticles: green synthesis and their antimicrobial activities. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;145(1–2):83–96.10.1016/j.cis.2008.09.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Yan-yu Ren, Hui Yang, Tao Wang, Chuang Wang. Green synthesis and antimicrobial activity of monodisperse silver nanoparticles synthesized using Ginkgo Biloba leaf extract. Phys Lett A. 2016;380(45):3773–7.10.1016/j.physleta.2016.09.029Search in Google Scholar

[5] Govindrao P, Ghule NW, Haque A, Kalaskar MG. Journal of drug delivery science and technology metal nanoparticles synthesis : an overview on methods of preparation, advantages and disadvantages, and applications. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2018;53:101174.10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101174Search in Google Scholar

[6] Thomas B, Mary S, Vithiya B, Arul TA. Science direct antioxidant and photo catalytic activity of aqueous leaf extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using passiflora edulis F. flavicarpa. Mater Today: Proc. 2019;14:239–47.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.04.143Search in Google Scholar

[7] Logeswari P, Silambarasan S, Abraham J. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plants extract and analysis of their antimicrobial property. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2015;19(3):311–7. 10.1016/j.jscs.2012.04.007.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Barberia-roque L, Gámez-espinosa E, Viera M, Bellotti N. International biodeterioration & biodegradation assessment of three plant extracts to obtain silver nanoparticles as alternative additives to control biodeterioration of coatings. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2017;141:52–61.10.1016/j.ibiod.2018.06.011Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ibrahim HMM. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using banana peel extract and their antimicrobial activity against representative microorganisms. J Radiat Res Appl Sci. 2015;8(3):265–75.10.1016/j.jrras.2015.01.007Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ren Y, Yang H, Wang T, Wang C. Bio-synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial activity. Mater Chem Phys. 2019;235:121746–84.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.121746Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bar H, Bhui DK, Sahoo GP, Sarkar P, De SP, Misra A. Aspects green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using latex of jatropha curcas, colloids and surfaces a: physicochemical and engineering. 2009;339:134–9.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.02.008Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ruíz-baltazar ÁDJ, Maya-cornejo J, Rodríguez-morales AL, Esparza R. Results in physics alcoholic extracts from paulownia tomentosa leaves for silver nanoparticles synthesis. Results Phys. 2018;12:1670–9.10.1016/j.rinp.2019.01.082Search in Google Scholar

[13] Abbate L, Tusa N, Fatta S, Bosco D, Strano T, Renda A, et al. Genetic improvement of Citrus fruits: new somatic hybrids from Citrus sinensis (L.) Osb. and Citrus limon (L.) Burm. F. FRIN. 2012;48(1):284–90.10.1016/j.foodres.2012.04.007Search in Google Scholar

[14] Balasundram N, Sundram K, Samman S. Phenolic compounds in plants and agri-industrial by-products: Antioxidant activity, occurrence, and potential uses. Food Chem. 2006;99(1):191–203.10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.07.042Search in Google Scholar

[15] Gorinstein S, Martı́n-Belloso O, Park YS, Haruenkit R, Lojek A, Ĉı́ž M, et al. Comparison of some biochemical characteristics of different citrus fruits. Food Chem. 2001;74(3):309–15.10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00157-1Search in Google Scholar

[16] Behravan M, Hossein A, Naghizadeh A, Ziaee M, Mahdavi R, Mirzapour A. International journal of biological macromolecules facile green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using berberis vulgaris leaf and root aqueous extract and its antibacterial activity. Int J Biol Macromolecules. 2019;124:148–54.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Tripathi D, Modi A, Narayan G, Pandey S. Materials science & engineering C green and cost effective synthesis of silver nanoparticles from endangered medicinal plant Withania coagulans and their potential biomedical properties. Mater Sci & Eng C. 2017;100:152–64.10.1016/j.msec.2019.02.113Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Cappellari L, del R, Santoro MV, Nievas F, Giordano W, Banchio E. Increase of secondary metabolite content in marigold by inoculation with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Appl Soil Ecol. 2013;70:16–22.10.1016/j.apsoil.2013.04.001Search in Google Scholar

[19] Khaleghnezhad V, Yousefi AR, Tavakoli A, Farajmand B. Interactive effects of abscisic acid and temperature on rosmarinic acid, total phenolic compounds, anthocyanin, carotenoid and flavonoid content of dragonhead (Dracocephalum moldavica L.). Sci Horticulturae. 2018;250:302–9.10.1016/j.scienta.2019.02.057Search in Google Scholar

[20] Soto KM, Quezada-Cervantes CT, Hernández-Iturriaga M, Luna-Bárcenas G, Vazquez-Duhalt R, Mendoza S. Fruit peels waste for the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogens. LWT. 2019;103:293–300.10.1016/j.lwt.2019.01.023Search in Google Scholar

[21] Jridi M, Boughriba S, Abdelhedi O, Nciri H, Nasri R, Kchaou H, et al. Investigation of physicochemical and antioxidant properties of gelatin edible film mixed with blood orange (Citrus sinensis) peel extract. Food Packaging Shelf Life. 2019;21:100342.10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.100342Search in Google Scholar

[22] Ahmed AF, Attia FAK, Liu Z, Li C, Wei J, Kang W. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of essential oils and extracts of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) plants. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2019;8(3):299–305.10.1016/j.fshw.2019.07.004Search in Google Scholar

[23] Bindhu MR, Umadevi M. Synthesis of monodispersed silver nanoparticles using Hibiscus cannabinus leaf extract and its antimicrobial activity. Spectrochim Acta - Part A: Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2013;101:184–90.10.1016/j.saa.2012.09.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Chahar V, Sharma B, Shukla G, Srivastava A, Bhatnagar A. Study of antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using green and chemical approach. Colloids Surf A. 2018;554:149–55.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.06.012Search in Google Scholar

[25] Basavegowda N, Rok Lee Y. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu) peel extract: A novel approach towards waste utilization. Mater Lett. 2013;109:31–3.10.1016/j.matlet.2013.07.039Search in Google Scholar

[26] Majumdar M, Khan SA, Biswas SC, Roy DN, Panja AS, Misra TK. In vitro and in silico investigation of anti-biofilm activity of Citrus macroptera fruit extract mediated silver nanoparticles. J Mol Liq. 2020;302:112586.10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112586Search in Google Scholar

[27] Samrot AV, Raji P, Jenifer Selvarani A, Nishanthini P. Antibacterial activity of some edible fruits and its green synthesized silver nanoparticles against uropathogen – Pseudomonas aeruginosa SU 18. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018;16:253–70.10.1016/j.bcab.2018.08.014Search in Google Scholar

[28] Konwarh R, Karak N, Sarwan EC, Baruah S, Mandal M. Effect of sonication and aging on the templating attribute of starch for “green” silver nanoparticles and their interactions at bio-interface. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;83(3):1245–52.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.09.031Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ahn E, Jin H, Park Y. Assessing the antioxidant, cytotoxic, apoptotic and wound healing properties of silver nanoparticles green-synthesized by plant extracts. Mater Sci Eng C. 2018;101:204–16.10.1016/j.msec.2019.03.095Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Dakshayani SS, Marulasiddeshwara MB, Kumar MNS, Ramesh G, Kumar PR, Devaraja S, et al. Antimicrobial, anticoagulant and antiplatelet activities of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Selaginella (Sanjeevini) plant extract. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;131:787–97.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.01.222Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Vigneshwaran N, Ashtaputre NM, Varadarajan PV, Nachane RP, Paralikar KM, Balasubramanya RH. Biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Aspergillus flavus. Mater Lett. 2007;61(6):1413–8.10.1016/j.matlet.2006.07.042Search in Google Scholar

[32] Rashid S, Azeem M, Ali S, Maroof M. Biointerfaces characterization and synergistic antibacterial potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using aqueous root extracts of important medicinal plants of Pakistan. Colloids Surf B. 2018;179:317–25.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.04.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Hernández-morales L, Espinoza-gómez H, Flores-lópez LZ, Sotelo-barrera EL, Núñez-rivera A, Cadena-nava RD, et al. Study of the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a natural extract of dark or white Salvia hispanica L seeds and their antibacterial application. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;489:952–61.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.06.031Search in Google Scholar

[34] Jemilugba OT, Hadji E, Sakho M, Parani S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Combretum erythrophyllum leaves and its antibacterial activities. Colloid Interface Sci Commun. 2019;31:100191.10.1016/j.colcom.2019.100191Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Lebogang Mogole et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis