Abstract

Thermoanalysis was used in this research to produce a comparative study on the combustion and gasification characteristics of semi-coke prepared under pyrolytic atmospheres rich in CH4 and H2 at different proportions. Distinctions of different semi-coke in terms of carbon chemical structure, functional groups, and micropore structure were examined. The results indicated that adding some reducing gases during pyrolysis could inhibit semi-coke reactivity, the inhibitory effect of the composite gas of H2 and CH4 was the most observable, and the effect of H2 was higher than that of CH4; moreover, increasing the proportion of reducing gas increased its inhibitory effect. X-ray diffractometer and Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer results indicated that adding reducing gases in the atmosphere elevated the disordering degree of carbon microcrystalline structures, boosted the removal of hydroxyl- and oxygen-containing functional groups, decreased the unsaturated side chains, and improved condensation degree of macromolecular networks. The nitrogen adsorption experiment revealed that the types of pore structure of semi-coke are mainly micropore and mesopore, and the influence of pyrolytic atmosphere on micropores was not of strong regularity but could inhibit mesopore development. Aromatic lamellar stack height of semi-coke, specific surface area of mesopore, and pore volume had a favorable linear correlation with semi-coke reactivity indexes.

1 Introduction

Low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke is a solid product after removing a number of volatiles from low-rank coal under low-temperature pyrolysis (500–600°C) and tar is separated out [1,2]. Part of this product has been applied to fields like coal gasification, ferroalloy smelting, and calcium carbide production; however, there is still a large quantity of semi-coke resources that require market consumption. In the field of iron-making, pulverized coal injection (PCI) in blast furnace replaces expensive and highly deficient metallurgical coke with relatively low-priced coal to reduce the coke ratio in the blast furnace during iron-making process, and thereby reduce pig iron cost [3,4]. With the continuously increasing blast furnace injection ratio, iron and steel enterprises have an increasing demand for anthracite. Moreover, anthracite reserves only occupy 10.9% of coal reserves in China with unceasingly prominent scarcity, which is then accompanied by rising price. Therefore, under the background of an increase in PCI ratio in blast furnace, seeking for new low-cost and high-quality injecting fuels such as biochar [5] and waste plastics [6] has always been a research emphasis of metallurgists. Using low price semi-coke as PCI fuel to replace expensive anthracite has been an important research orientation for optimizing blast furnace fuel structures, and the reduced production cost has attracted attention from metallurgists [7,8,9,10,11]. Semi-coke is a potential excellent blast furnace fuel by virtue of favorable transport performance, high calorific value, and no explosiveness [7,10]. However, compared with anthracite, the nature difference of semi-coke is considerable because of its instable quality; moreover, the fluctuation of its combustion performance is remarkable and hinders its application and promotion in blast furnace injection, because during semi-coke production, pyrolysis conditions will influence the semi-coke composition and structure and cause changes in its reactivity. Even if the same coal category is used as a pyrolytic raw material, the reactivity of prepared semi-coke will be critically different, and high pyrolysis degree is adverse to follow-up combustion of semi-coke [11,12]. Factors, such as devolatilization behavior, pore structure, specific surface area, and ordering degree of carbon lattice structure, will result in substantial loss of semi-coke reactivity [13,14,15]. Combustion reactivity in later phase of semi-coke under high temperature is closely related to semi-coke nature before combustion [16].

The present industrialized pyrolytic processes generally use internal heating-type gas-carrier pyrolysis reactors. In such pyrolysis environments, the raw coal exists not in a pure N2 atmosphere but in mixed reducing gases such as CO, H2, and CH4. Moreover, pyrolysis atmosphere contents are different to a certain degree at various positions inside the furnace. The influences of pyrolysis conditions, such as pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, atmosphere pressure, and holding time, on semi-coke composition, structure, and reactivity [17,18,19] have been extensively studied; however, the effects of pyrolytic atmosphere on semi-coke reactivity remain controversial. Colette et al. [20,21] studied the influence of the coke-oven gas atmosphere on product distribution and semi-coke characteristics in fixed beds and found that semi-coke combustion characteristics were not eminently different under H2 and inert atmospheres. Liao et al. [22] indicated that the combustion reactivity of coal–coke-oven gas co-pyrolytic semi-coke is related to pyrolysis pressure and heating rate, and that low pyrolysis pressure and high heating rate contribute to semi-coke combustion reactivity. Zhong et al. [23] found that hydrogen-free radicals generated by H2 and CH4 could permeate semi-coke and influence its oxidizing reactivity. Thus, the influence of mixed atmospheres containing reducing gases on semi-coke nature and its reactivity requires further research.

During iron-making technology in blast furnace, PCI fuels experience processes, such as volatile extrusion and combustion and gasification of fixed carbon, within confined spaces in the tuyere and raceway region. Compared with the process of release and combustion of volatiles, char combustion and gasification are relatively slow (20 ms vs 1–4 s), and the time needed for a complete reaction of coal is primarily and jointly determined by char combustion and gasification time [24]. Combustion and gasification properties are highly important for the utilization ratio of fuels inside the furnace and the stable operation of the blast furnace because the combustion of atmosphere inside the hearth is gradually variational. In the front of the tuyere, generated coal gas components are different because of different combustion conditions at different positions along the hearth radius in front of the tuyere. O2 is sufficient in front of the tuyere and reacts with fuel combustion to generate a large quantity of CO2, O2 abruptly decreases and disappears, and CO2 rapidly rises to its maximum value. Therefore, the injected fuel first experiences atmospheric combustion with sufficient O2 and then experiences gasification under the atmosphere with a continuously rising CO2. However, many research on reactivity of PCI fuels only focuses on combustion reactivity [3,25,26] and neglects the importance of gasification reactivity on the consumption of unburned char; moreover, comparative studies on the two abovementioned subject matter are lacking.

In the present research, thermoanalysis was applied to comparatively study the combustion and gasification reactivity of semi-coke prepared under pyrolytic atmospheres containing different proportions of H2- and CH4-reducing gases. Moreover, the relationships between semi-coke composition/structure and combustion/gasification reactivity were obtained by analyzing the carbon chemical structures of different semi-coke, functional group analysis, and micropore structures to provide reference for further scientific and highly efficient application of semi-coke in PCI.

2 Experimental procedure

2.1 Experimental raw materials

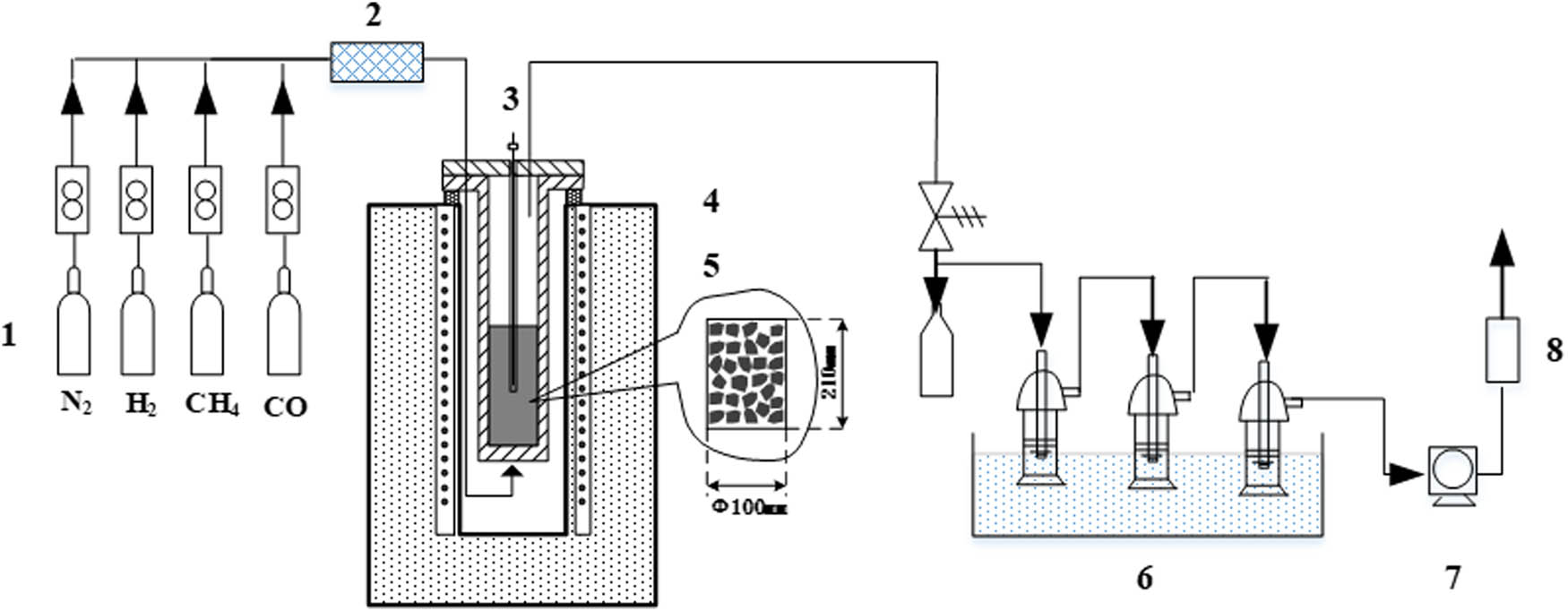

Coal samples used in the experiment were typical low-rank coals from Sunjiacha coal mine in Shenmu region of Northern Shaanxi. Proximate analysis and element analysis of coals are illustrated in Table 1. Vertical-type pyrolyzing furnace was used to prepare semi-coke samples, and the pyrolysis system is shown in Figure 1. A total of 250 g samples with granularity within 20–40 mm was placed in a furnace and suspended on an electronic scale. A total of six pyrolytic atmospheres (respectively being (1) pure N2; (2) 10% CH4 in N2; (3) 20% CH4 in N2; (4) 10% H2 in N2; (5) 20% H2 in N2; and (6) 10% H2, and 10% CH4 in N2) were pumped into the reaction jar at a 0.6 L/min flow rate. Samples were heated to 600°C at a rate of 5°C/min and heat was preserved for 30 min, then nitrogen was pumped in for cooling in room temperature. After pyrolysis, semi-coke samples were extracted, labeled char1–char6, and preserved in a drying vessel for further property analysis. The detailed properties of the samples are summarized in Table 1.

Proximate analysis and ultimate analysis of coal and chars

| Samples | Proximate analysis (wt%, ad) | Ultimate analysis (wt%, ad) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ad | A ad | V daf | FC | C | H | N | O | S | |

| Coal | 3.83 | 7.53 | 37.06 | 55.97 | 71.97 | 4.08 | 0.93 | 10.21 | 0.20 |

| char1 | 1.17 | 9.15 | 8.21 | 81.47 | 82.8 | 2.42 | 0.61 | 1.17 | 0.23 |

| char2 | 1.38 | 9.99 | 8.04 | 80.59 | 83.71 | 2.02 | 0.38 | 1.38 | 0.20 |

| char3 | 1.44 | 8.23 | 8.01 | 82.32 | 83.09 | 1.87 | 0.28 | 1.44 | 0.21 |

| char4 | 1.40 | 9.01 | 8.49 | 81.10 | 82.81 | 2.24 | 0.55 | 1.34 | 0.16 |

| char5 | 1.32 | 8.99 | 7.40 | 82.29 | 83.45 | 2.01 | 0.62 | 1.26 | 0.19 |

| char6 | 1.23 | 8.40 | 7.11 | 83.26 | 83.02 | 1.95 | 0.51 | 1.31 | 0.17 |

Pyrolysis device diagram. (1) Gas cylinder; (2) gas blending instrument; (3) sample temperature thermocouple; (4) temperature thermocouple inside furnace; (5) pyrolyzing furnace; (6) gas purification and tar collection; (7) pump; (8) gas analyzer.

2.2 Representation of semi-coke properties

Combustion and gasification reactivity of semi-coke with an experimental weight of 10 ± 0.1 mg was tested using STA449C thermal analyzer from German NESZCH company. Under atmosphere of air (combustion)/CO2 (gasification) and a flow rate of 50 mL/min, the temperature was elevated from room temperature to 1,000°C (combustion)/1,400°C (gasification) at a rate of 15°C/min, and weight change was synchronously recorded. For the quantitative comparison of semi-coke reactivity, the combustion reactivity index R c and gasification reactivity index R g were introduced [27,28]:

where V rate is the average reaction rate of semi-coke combustion, T ignition is the ignition point of semi-coke combustion determined through thermogravimetry-derivative thermogravimetry (TG–DTG) method [29], and t 0.5 is the time for carbon conversion rate α to reach 50%. α was determined using:

where

Carbon chemical constitution of semi-coke was measured through X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (X’Pert PROMPD) using Cu-Kα target at a scanning rate of 4°/min. Feature sizes of the microcrystalline structure of the semi-coke are represented by d 002, L a, and L c and were solved according to the Scherrer formula and Bragg equation [30]:

where d 002 is the distance between the single aromatic layers of the sample, L c is the microcrystal stack height perpendicular to the aromatic lamellas, θ 002 is the glancing angle, β 002 is the full width at half maximum of the diffraction peak, and λ is the wavelength at 0.15406 nm of the incident X-ray.

Functional group of semi-coke was detected through Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) (German Bruker, Vector 22). Semi-coke samples were prepared using the KBr squashing technique, and test spectral range was 400–4,000 cm−1 with a resolution ratio of 4 cm−1. The sample spectra were obtained through scanning after deducting the blank KBr background. Aromaticity was derived using the formulas by Brown and Ladller [31]:

where

Physicochemical absorber (US Micromeritics, ASAP 2020M+C) and N2 adsorption method were used to test the specific surface area and micropore structure of semi-coke, with a degasification temperature during the test at 200°C.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Combustion/gasification reactivity

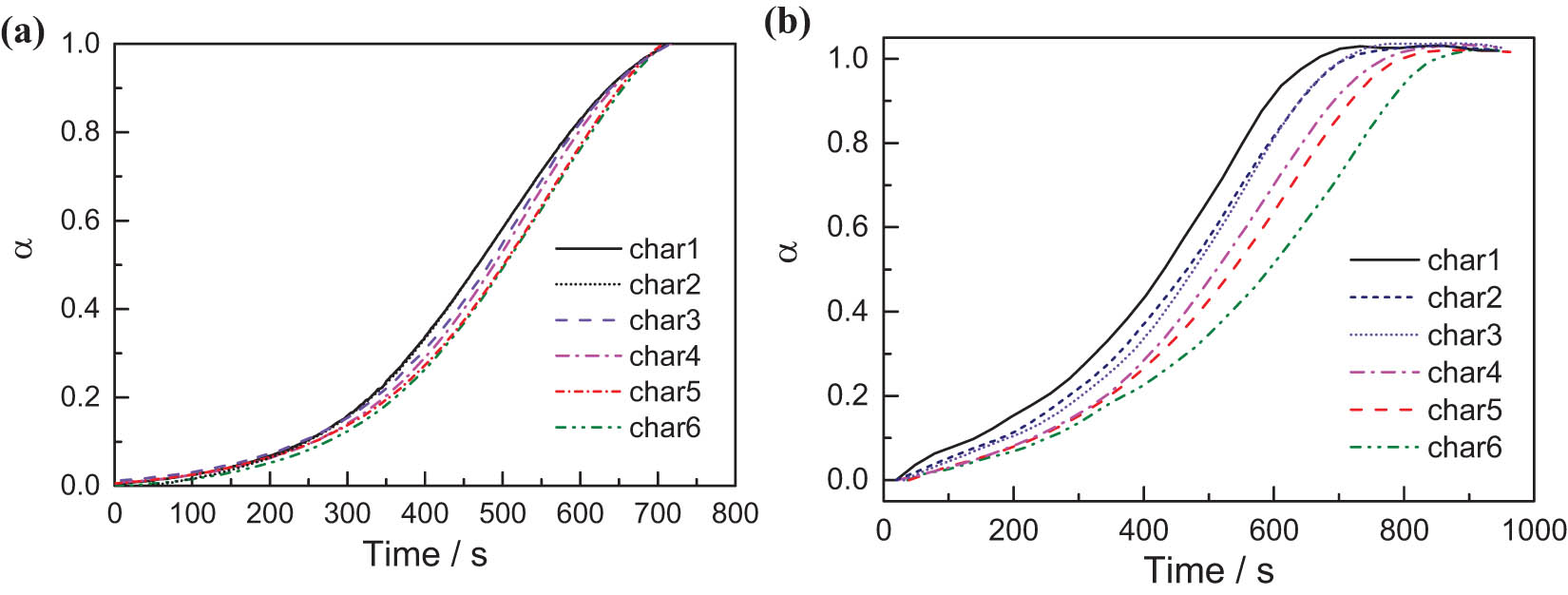

TG–DTG curves of combustion and gasification of semi-coke samples prepared under different pyrolytic atmospheres are shown in Figure 2, and semi-coke combustion and gasification characteristic parameters are presented in Table 2.

TG–DTG curves of combustion and gasification processes of semi-coke samples prepared under different pyrolytic atmospheres. (a) Air atmosphere; (b) CO2 atmosphere.

Characteristic parameters of semi-coke during combustion and gasification processes

| Samples | T max (°C) | V max (°C min−1) | T i (°C) | T f (°C) | R c (×103) | T 0.5 (°C) | R g (s−1 [×104]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| char1 | 510 | 0.9915 | 447 | 574 | 2.21812 | 1,007 | 11.65501 |

| char2 | 509 | 0.9396 | 454 | 567 | 2.0696 | 1,016 | 10.77586 |

| char3 | 512 | 0.8657 | 447 | 559 | 1.93669 | 1,020 | 10.5042 |

| char4 | 515 | 0.8468 | 448 | 572 | 1.89018 | 1,028 | 9.80392 |

| char5 | 505 | 0.8106 | 450 | 579 | 1.80133 | 1,034 | 9.27644 |

| char6 | 501 | 0.7875 | 455 | 570 | 1.73077 | 1,048 | 8.47458 |

As shown in Figure 2a, under air atmosphere, six semi-coke samples started losing weight under 368°C or higher, which indicated that volatiles in semi-coke have started to decompose. Subsequently, weight loss rate increased, which suggested that the fixed carbon experienced a rapid combustion reaction. Weight loss basically ended under 570°C or so, which indicated semi-coke after-combustion. In the initial phase of rapid combustion of six semi-coke samples, differences between TG and DTG curves were not evident. In the phase of maximum weight loss rate, the maximum combustion rates of different semi-coke were distinctive, with the reaction rate of char1 being the fastest, followed by char2; moreover, minor differences existed in the reaction rates of char3–char6. In the late combustion phase, DTG curves of semi-coke no. 2–6 slightly advanced. The range of ignition temperature of the six semi-coke samples was from 447°C to 455°C, which indicated that the differences in ignition temperature in the various semi-coke samples were poor. To compare the semi-coke combustion reactivity values, the six curves were analyzed through combustion reactivity indexes in Eq. 1. After calculation, semi-coke combustion reactivity indexes were sorted in descending order: char6 > char5 > char4 > char3 > char2 > char1, which indicated that compared with the pyrolysis atmosphere of N2, adding reducing gases CH4 and H2 in the pyrolysis process of raw coal will reduce the combustion reactivity and gasification reactivity of semi-coke.

Figure 2b indicates that under a CO2 atmosphere, the six semi-coke samples experienced a volatile and slow gasification phase before 870°C or so, and a rapid gasification reaction happened under 870°C or so; moreover, the finishing temperature of gasification reaction was from 1,050°C to 1,100°C. The six semi-coke samples had noticeable differences in TG and DTG curves compared with char1 prepared under a nitrogen atmosphere; furthermore, the TG and DTG curves of char2–char6 prepared after adding reducing gases experienced retroposition, and the maximum reaction rate and reaction finishing temperature escalated. The semi-coke gasification reactivity indexes were arranged in descending order: char6 > char5 > char4 > char3 > char2 > char1. The results indicated that the addition of reducing gases in the pyrolysis phase of raw coal resulted in a clear degradation of gasification reactivity and inhibition of composite gas of H2; in addition, CH4 was the most recognizable, the influence of H2 was stronger than that of CH4, and the increased concentration of reducing gases increased its inhibitory effect.

To compare the combustion and gasification reactivity of different semi-coke, time-dependent changes in carbon conversion rates of different semi-coke are illustrated in Figure 3. At the same combustion reaction time, the difference in combustion conversion rates of the different semi-coke was minimal. From Figure 3b, at the same gasification reaction time, different semi-coke had observable differences in gasification reactivity. The time required by char1 to complete combustion and gasification was 700 s or so, and that of char2–char6 continuously increased; thus, this phenomenon became increasingly apparent during gasification. This indicated that the pyrolytic atmosphere conditions influenced the gasification reactivity at a higher degree than that of combustion reactivity. The semi-coke has favorable combustion reactivity; therefore, the after-combustion temperature was lower than 600°C, and the chemical reaction itself could be the restrictive link of combustion. The semi-coke gasification reaction temperature was higher than that of the combustion reaction; moreover, the chemical reaction itself proceeded rapidly and the diffusion of reactants and products should be the restrictive link of this gasification process. Emphasis will be placed on the factors influencing semi-coke chemical reactions, such as carbon chemical structure, functional group distribution, and micropore structural characteristics that influence diffusion.

Time-dependent changes in carbon conversion rates of different semi-coke. (a) Air atmosphere; (b) CO2 atmosphere.

3.2 XRD analysis of chars

Figure 4 shows the XRD spectrums of the six semi-coke samples. The C(002) peaks of samples char1–char6 sharpened, which indicated that the carbon microcrystalline structures of semi-coke prepared by adding reducing gases in the atmosphere were likely to be of the graphite state. X’Pert highscore analysis software, together with Eq. 4 and 5, was used to obtain the position of C(002) peak, lamellar spacing

XRD spectrums of different semi-cokes.

Characteristic parameters of microcrystalline structure of semi-coke

| Samples | C(002) (°) | d 002 (10−10 m) | L c (10−10 m) | L c (d 002) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| char1 | 24.83 | 3.58 | 12.09 | 2.26 |

| char2 | 24.91 | 3.57 | 12.21 | 2.20 |

| char3 | 25.01 | 3.56 | 12.26 | 2.32 |

| char4 | 25.02 | 3.56 | 12.39 | 2.36 |

| char5 | 25.03 | 3.56 | 12.50 | 2.39 |

| char6 | 25.04 | 3.56 | 12.93 | 2.51 |

In Table 3, the differences in 2

Figure 5 shows the relationships of semi-coke L c with the combustion and gasification reactivity indexes. As shown in Figure 5, semi-coke carbon microcrystalline structure has identical influence rules on combustion reactivity and gasification reactivity, namely, with the enhanced ordering degree of carbon microcrystalline structure, decreased semi-coke reactivity indexes, and the certain linear relation of the two. In a study on the influence of heat treatment temperature and heating rate on coke reactivity, Lu et al. found [24] that from amorphous carbon, the carbon structure described by the aromaticity and crystallite size became highly systematized with the rise in heat treatment temperature and decline in heating rate, thus, semi-coke reactivity was degraded. With the increased proportion of reducing gases in the nitrogen atmosphere, the semi-coke carbon structure became highly ordered, which degraded semi-coke reactivity because when the size of the aromatic lamella increased, the ratio of the active marginal carbon atoms to the non-active carbon atoms in the cardinal plane will be reduced [32]. Moreover, when the arrangement of the aromatic lamellas became organized, the active carbon atoms bonded with the defects and the hetero atoms were reduced [21]. Both could degrade semi-coke combustion and gasification reactivity.

Relationships of semi-coke L c with combustion and gasification reactivity indexes. (a) L c vs R c; (b) L c vs R g.

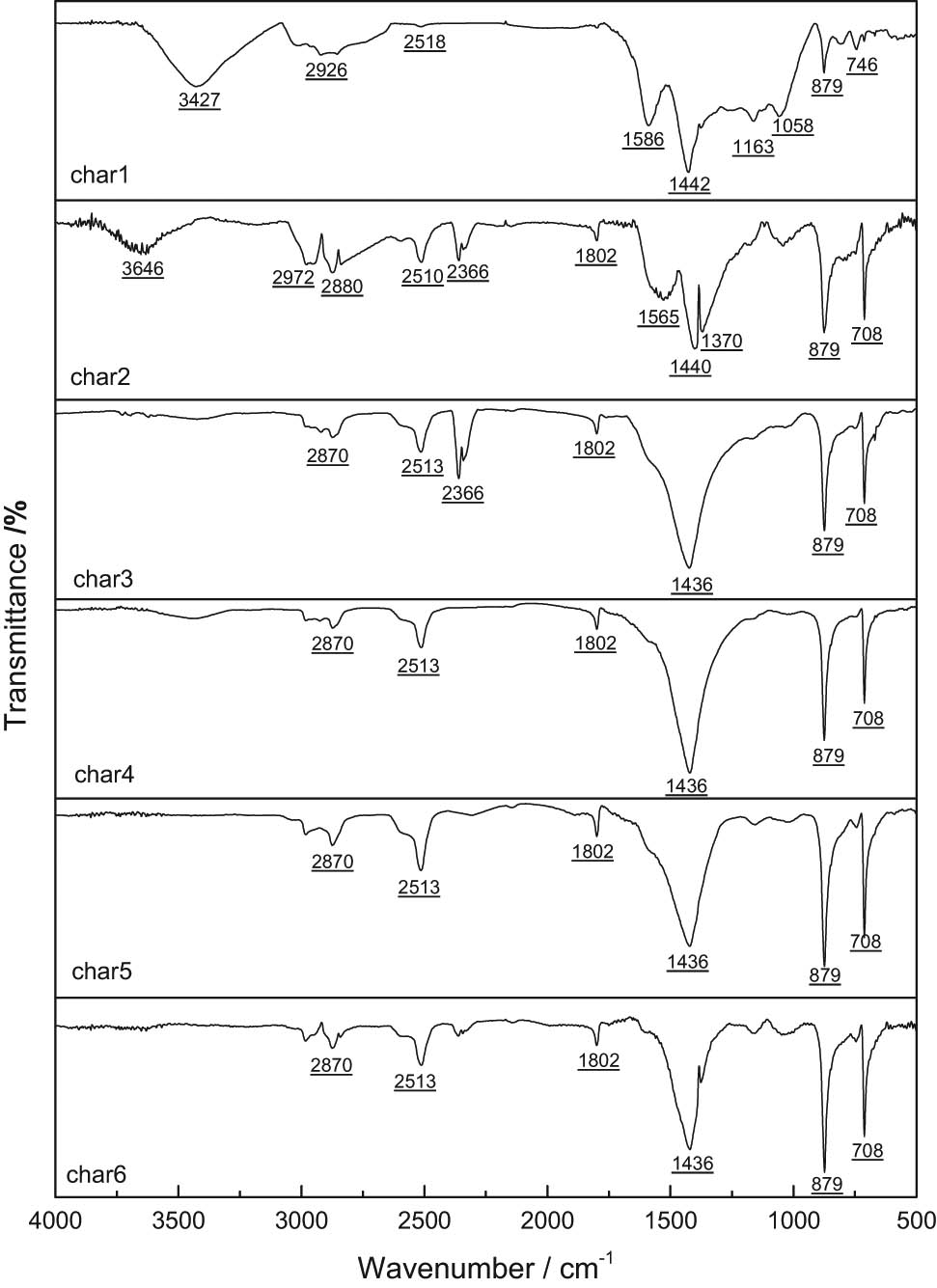

3.3 FTIR analysis of chars

Figure 6 shows the FTIR spectra of different semi-coke. To carry out specific analysis on the wave number region of semi-coke 4,000–400 cm−1, the entire infrared spectrum is divided into four parts [31] as follows: hydroxyl absorption peak (3,600–3,000 cm−1), aliphatic hydrocarbon absorption peak (3,000–2,700 cm−1), oxygen-containing functional group absorption peak (1,800–1,000 cm−1), and aromatic hydrocarbon absorption peak (900–700 cm−1). It can be seen from Figure 6 that the distribution of functional groups in different semi-coke samples is different. Compared with other semi-coke samples, there is an obvious hydroxyl absorption peak between char1 and char2, but char2 is mainly composed of free hydroxyl groups, char1 is mainly composed of phenol, alcohol, carboxylic acid, and hydroxyl in water, and there are obvious antisymmetric stretching vibrations of CH3 and CH2 in naphthenes or aliphatic groups. All the semi-coke samples had stretching vibration of S–H bond near 2,510 cm−1, but the vibration peak shape of char1 was not obvious. CH3 vibration peak exists in all samples near 1,440 cm−1, but obvious vibration peak exists in char1 and char2 near 1,590 cm−1. This is the vibration peak of aromatic C═C, and it is the skeleton vibration of benzene ring. char1–char6 have obvious characteristic peaks near 880 and 710 cm−1, but the peak intensity of char1 is significantly lower than that of other semi-focal points. char1 has obvious vibration peaks at 1,058 and 1,183 cm−1, which are stretching vibration peaks of Si–O–Si, Si═O, or Si–O–C. Oxygen-containing functional groups are obvious in char1. When the pyrolytic atmosphere contains H2 or CH4, removal of hydroxyls and oxygen-containing functional groups reduced content of unsaturated side chains, and elevated condensation degree of macromolecular network will be facilitated.

Semi-coke FTIR spectrums.

To further describe the differences in various semi-coke samples in the macromolecular structure, Eq. 6–8 were used to calculate and compare the aromaticity of semi-coke. Table 4 presents the obtained IR structural parameters. It can be seen from the table that when CH4 or H2 is added in the pyrolysis atmosphere, aliphatic hydrocarbons and carbon groups in the raw coal are more easily decomposed and precipitated, which is specifically reflected in the significant decrease in the contents of H al and H ar and the significant increase in f a of the samples. However, the influence of CH4 atmosphere and H2 atmosphere is different. Compared with H2 atmosphere, CH4 atmosphere has a more obvious effect on f a promotion.

Structure parameters deduced from FTIR for chars

| Samples | H al (%) | H al/H | C al/C | f a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| char1 | 0.789 | 0.326 | 0.05261 | 0.94739 |

| char2 | 0.559 | 0.277 | 0.04344 | 0.95656 |

| char3 | 0.497 | 0.266 | 0.04051 | 0.95949 |

| char4 | 0.412 | 0.184 | 0.04869 | 0.95131 |

| char5 | 0.37 | 0.184 | 0.04336 | 0.95664 |

| char6 | 0.359 | 0.184 | 0.04228 | 0.95772 |

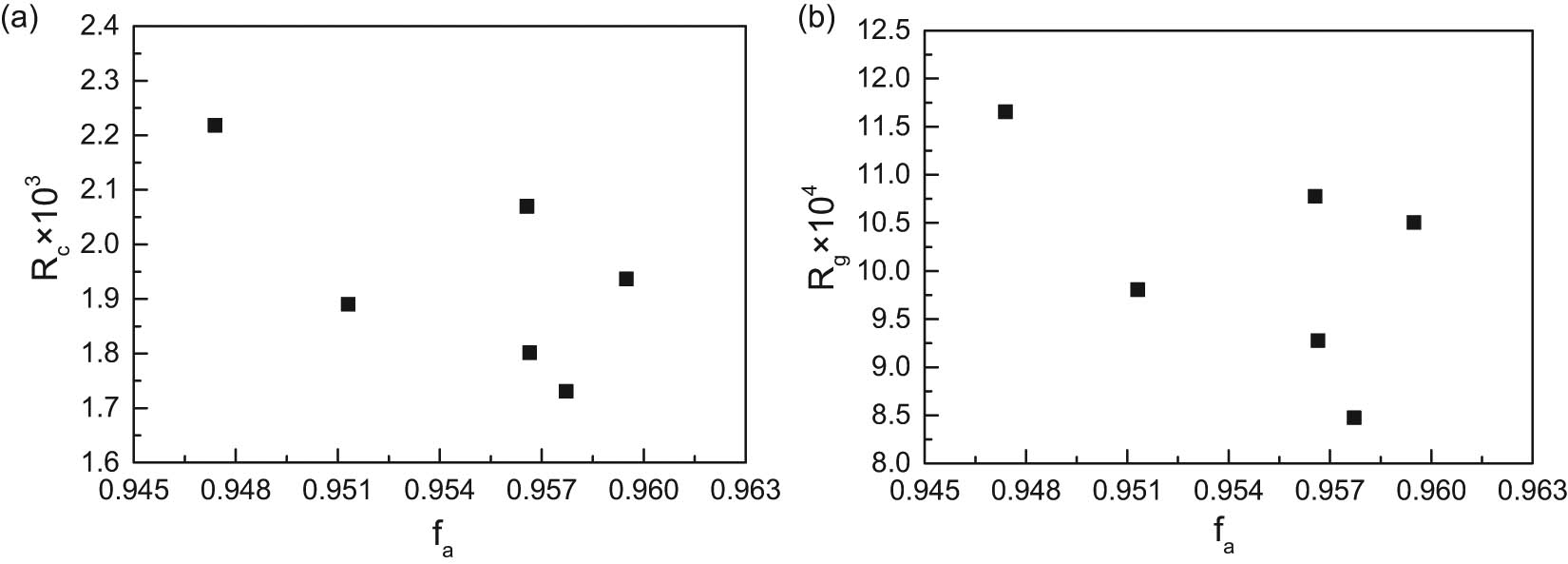

Relationships of semi-coke aromaticity with combustion and gasification reactions are shown in Figure 7. There is no obvious relationship between the aromaticity and combustion and gasification reaction index, but char1 gasification reactivity and combustion reactivity are best, its corresponding f a also minimum, shows that N2 pyrolysis atmosphere compared to add CH4 and H2, can maintain the sample in a certain amount of reactive strong aliphatic group, inhibit samples influence the reactivity of the increase of aromatic carbon.

Relationships of semi-coke f a with combustion and gasification reactivity indexes. (a) f a vs R c; (b) f a vs R g.

In summary, when CH4 or H2 is added in the pyrolysis atmosphere, aliphatic hydrocarbons and carbon groups in raw coal are more easily decomposed and precipitated, so as to improve the f a of semi-coke and reduce the reactivity of semi-coke. The influence of its functional groups is manifested in the fact that hydroxyl group, C═C, and oxygen-containing functional groups have a promoting effect on the improvement of reactivity, whereas the increase in S–H and aromatic hydrocarbon contributes to the improvement of aromaticity, thus reducing the reactivity of semi-coke.

3.4 Effects of pore structure of chars on reactivity

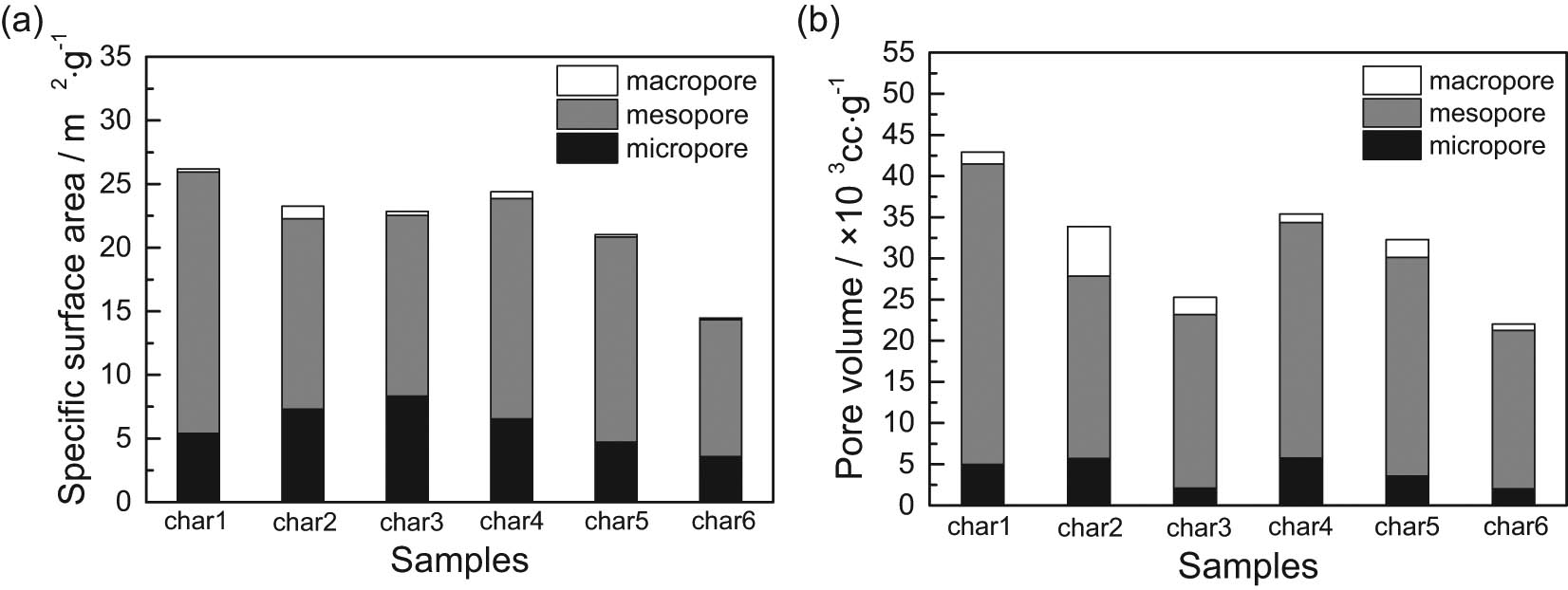

Figure 8 shows the pore structural distribution of the six semi-coke samples. Figure 8a shows that micropores below 2 nm and mesopores at 2–50 nm contributes to the main specific surface area. Independent addition of H2 or CH4 to the pyrolytic atmosphere increased the specific surface area of semi-coke micropores, and the micropore-specific surface areas of char2 and char3 added with CH4 gas were significantly enlarged. Differences in specific surface area between semi-coke mesopores were visible, and the independent addition of H2 or CH4 in pyrolytic atmosphere reduced the specific surface area of the semi-coke mesopores. Mesopore-specific surface areas of char3 and char4 added with H2 gas decreased more evidently than those of char2 and char3 added with CH4 gas, and the specific surface areas of mesopores added with both H2 and CH4 were mostly reduced. Mesopores contributed to the main pore volume and the order of pore volumes of the different semi-coke was consistent with rule of specific surface area. The difference between micropores in terms of pore volume was not obvious, and pore volumes 50 nm above pores were small. The above results showed that the main pore structural types of semi-coke were micropores and mesopores; moreover, the influence of the regularity of the pyrolytic atmosphere on micropores was not strong, but the pyrolytic atmosphere could reduce the quantity of mesopores. This is because, with an elevated pyrolysis degree, the generation of micropores, which dominated the semi-coke-specific surface area, was reduced. Moreover, the CH4 and H2 in the pyrolytic atmosphere reacted with macromolecular side chains in the coal during pyrolysis to improve the yield and precipitation rate of pyrolytic gases [33], which then further boosted the development and growth of micropores toward mesopores, as well as the cross-linking and combination of mesopores. As a result, the pore-specific surface area and pore volume were reduced.

Specific surface area and pore volume of semi-coke.

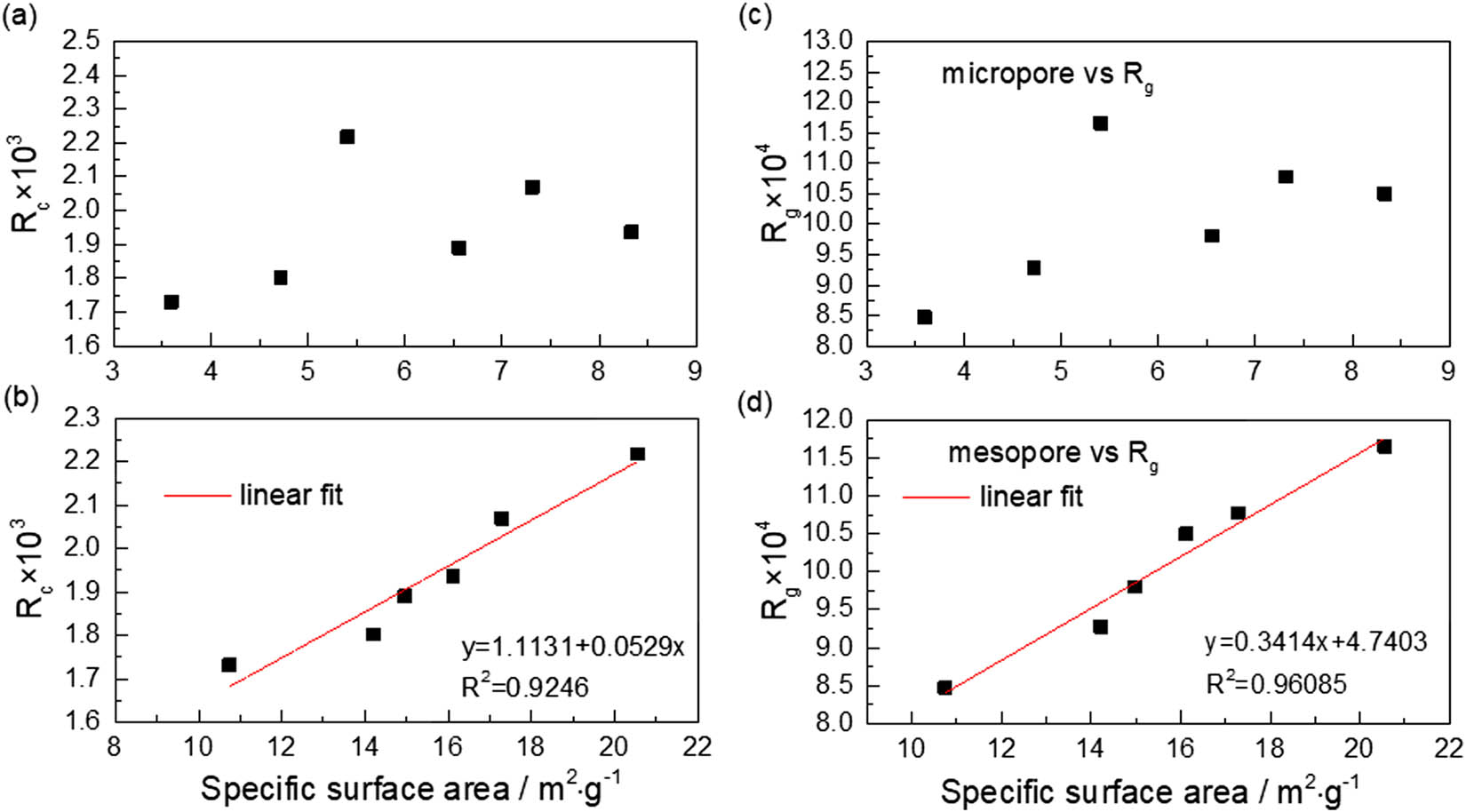

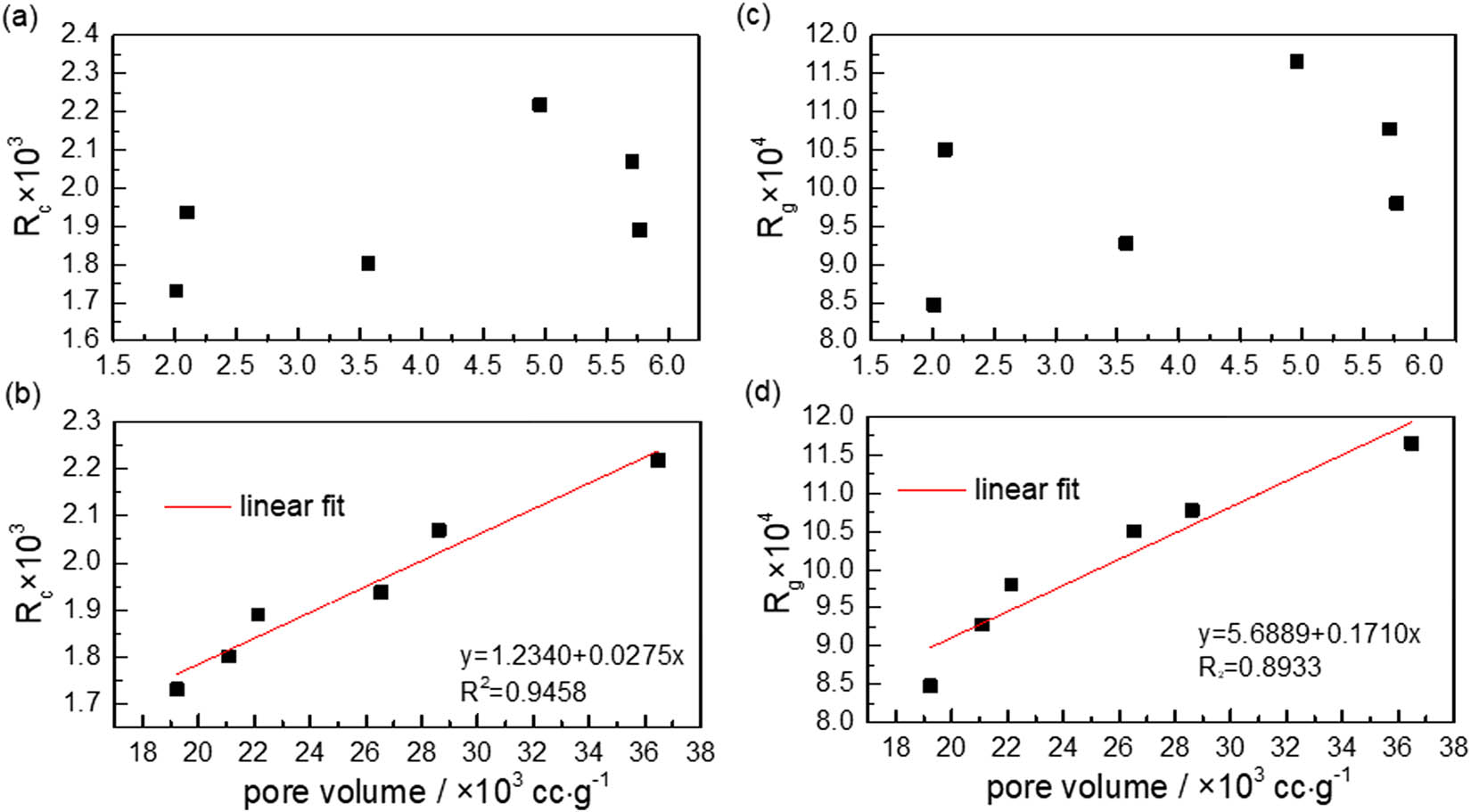

Figures 9 and 10 show the relationships between semi-coke-specific surface area and combustion and gasification reactivity indexes. Combustion and gasification reactivity indexes presented weak linear correlations with micropore-specific surface area and pore volume. However, they have a favorable linear correlation with mesopore volume (i.e., as mesopore-specific surface area and pore volume increased, the combustion and gasification reactivity were improved) because compared with homogeneous reaction, as heterogeneous reaction processes, the semi-coke combustion and gasification contained two important features, namely diffusion of reactant molecules and reaction interface conditions. Semi-coke pore structure not only provided a diffusion channel for oxygen/carbon dioxide molecules that is required by combustion and gasification but also provided a large specific surface area for gas analysis and solid contact during gas–solid heterogeneous reaction [28]. Therefore, the developed pore structure of semi-coke improved their combustion and gasification reactivity.

Relationships between semi-coke-specific surface area and reactivity indexes. (a) Micropore vs R c; (b) mesopore vs R c; (c) micropore vs R g; (d) mesopore vs R g.

Relationships between semi-coke pore volume and reactivity indexes. (a) Micropore vs R c; (b) mesopore vs R c; (c) micropore vs R g; (d) mesopore vs R g.

Semi-coke combustion and gasification reactivity were closely related to the ordering degree of carbon chemical structure and micropore structure; moreover, they had a certain relationship with the distribution of functional groups. For the convenience of semi-coke application in iron-making, the pyrolysis temperature, holding time, heating rate, and other conditional parameters during pyrolysis should be reasonably regulated to counterbalance the adverse effects of reducing gases in the pyrolytic atmosphere on the semi-coke reactivity, so that they meet blast furnace PCI requirements.

4 Conclusions

In this research, the combustion and gasification characteristics of semi-coke prepared under pyrolytic atmospheres rich in CH4 and H2 at different proportions were investigated, and the effect of carbon chemical structure, functional groups, and micropore structure of char on reactivity was also analyzed. The results showed that CH4 and H2 exhibited inhibiting effect on semi-coke reactivity. This inhibiting effect on gasification reactivity was stronger than that of combustion reactivity, and the influence of H2 was stronger than that of CH4. The reducing gases in the atmosphere enhanced the disordering degree of the carbon crystalline structure, boosted removal of hydroxyl and oxygen-containing functional groups, reduced content of unsaturated side chains, and elevated the condensation degree of the macromolecular network. The main semi-coke pore structural types were micropores and mesopores. Influence on the regularity of the pyrolytic atmosphere on micropores was not strong, but the pyrolytic atmosphere could inhibit mesopore development. Aromatic lamella stack height of the semi-coke, specific surface area of mesopore, and pore volume had favorable linear correlations with semi-coke reactivity indexes.

-

Research funding: The authors are grateful for the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51904223), the Natural Science Foundation Research Project of Shaanxi, China (No. 2020JQ-674), and the Science and Technology Plan of Yulin (No. Z20200396 and Z20200397).

-

Author contributions: Yuan She: writing – original draft, review and editing, methodology, formal analysis; Chong Zou: writing – review and editing, methodology; Shiwei Liu: formal analysis; Keng Wu: methodology, project administration; Hao Wu: visualization, formal analysis; Hongzhou Ma: project administration; Ruimeng Shi: resources.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Blesa MJ, Miranda JL, Moliner R, Lzquierdo MT, Palacios JM. Low-temperature co-pyrolysis of a low-rank coal and biomass to prepare smokeless fuel briquettes. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2003;70(2):665–77. 10.1016/S0165-2370(03)00047-0.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wan X, Xing G, Wang Y. Development analysis of low-temperature pyrolysis technology for low rank coal. Dry Technol Equip. 2015;13(2):1–6. 10.16575/j.cnki.issn1727-3080.2015.02.004.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gupta S, Sahajwalla V, Al-Omari Y, French D. Influence of carbon structure and mineral association of coals on their combustion characteristics for pulverized coal injection (PCI) application. Metall Mater Trans B. 2006;37(3):457–73. 10.1007/s11663-006-0030-y.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Osório E, Gomes MLI, Vilela ACF, Kalkreuth W, Almeida MA, Borrego AG, et al. Evaluation of petrology and reactivity of coal blends for use in pulverized coal injection (PCI). Int J Coal Geol. 2006;68(1–2):14–29. 10.1016/j.coal.2005.11.007.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wijayanta AT, Alam MS, Nakaso K, Fukai J, Kunitomo K, Shimizu M. Combustibility of biochar injected into the raceway of a blast furnace. Fuel Process Technol. 2014;117:53–9. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2013.01.012.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Gupta S, Sahajwalla V, Wood J. Simultaneous combustion of waste plastics with coal for pulverized coal injection application. Energy Fuels. 2006;20(6):2557–63. 10.1021/ef060271g.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang LG, Ren W, Liu DJ, Zhang W, Wang ZY, Deng W. Study on semi-coke used as pulverized coal for injection into blast furnace. Angang Technol. 2015;1:13–17.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Yang SP, Cai WM, Zheng HA, Liang JQ, Zhang SJ, Xue QC. Performance analysis of semi-coke for blast furnace injection. Chin J Process Eng. 2014;14(5):896–900.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Xu CY, Dong J, Li XT, Tang AJ. Experimental research on semi-coke used for blast furnace injection and metallurgical performance. J Iron Steel Res. 2016;44(4):17–9.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Yang SP, Guo SQ, Zhang PH, Zhou JF, Wang M. Influence of semi-coke on blending coal injection characteristics for blast furnace. J Iron Steel Res. 2017;29(3):201–7. 10.13228/j.boyuan.issn1001-0963.20160146.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Li PC, Zhang JL, Xu RS, Song TF. Representation of characteristics for modified coal, simi-coke and coke used in blast furnace injection. Energy Metall Ind. 2015;34(3):41–5.Search in Google Scholar

[12] He XM, Fu PR, Wang CX, Lin HT, Wu S, Cao SX. Combustion behavior of low rank coal char application in blast furnace injection. Iron Steel. 2014;49(9):92–6. 10.13228/j.boyuan.issn0449-749x.20140066.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Haykiri-Açma H, Ersoy-Meriçboyu A, Küçükbayrak S. Combustion reactivity of different rank coals. Energ Convers Manag. 2002;43(4):459–65. 10.1016/S0196-8904(01)00035-8.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Chen CH, Du SW, Yang TH. Volatile release and particle formation characteristics of injected pulverized coal in blast furnaces. Energ Convers Manag. 2007;48(7):2025–33. 10.1016/j.enconman.2007.01.001.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Yu JL, Lucas JA, Wall TF. Formation of the structure of chars during devolatilization of pulverized coal and its thermoproperties: a review. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2007;33(2):135–70. 10.1016/j.pecs.2006.07.003.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zou C, Wen LY, Zhang SF, Bai CG, Yin GL. Evaluation of catalytic combustion of pulverized coal for use in pulverized coal injection (PCI) and its influence on properties of unburnt chars. Fuel Process Technol. 2014;119:136–45. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2013.10.022.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Cai HY, Guell AJ, Chatzakis IN, Lim JY, Dugwell DR, Kandiyoti R. Combustion reactivity and morphological change in coal chars: Effect of pyrolysis temperature, heating rate and pressure. Fuel. 1996;75(1):15–24. 10.1016/0016-2361(94)00192-8.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hu JH, Chen YQ, Qian KZ, Yang ZX, Yang HP, Li Y, et al. Evolution of char structure during mengdong coal pyrolysis: influence of temperature and K2CO3. Fuel Process Technol. 2017;159:178–86. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2017.01.042.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Li Q, Wang ZH, He Y, Sun Q, Zhang YW, Kumar S, et al. Pyrolysis characteristic and evolution of char structure during pulverized coal pyrolysis in drop tube furnace: influence of temperature. Energy Fuel. 2017;31(5):4799–807. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b00002.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Colette BD, Cypres R, Fontana A, Hoegaerden M. Coal hydromethanolysis with coke-oven gas: 2. Influence of the coke-oven gas components on pyrolysis yields. Fuel. 1995;74(1):17–9. 10.1016/0016-2361(94)P4324-U.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Colette BD, Fontana A, Labani A, Laurent P. Coal hydromethanolysis with coke-oven gas: 3. Influence of the coke-oven gas components on the char characteristics. Fuel. 1996;75(11):1274–8. 10.1016/0016-2361(96)00108-1.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Liao HQ, Li BQ, Zhang BJ. Co-pyrolysis of coal with hydrogen-rich gases: 1. Coal pyrolysis under coke-oven gas and synthesis gas. Fuel. 1998;77(8):847–51. 10.1016/S0016-2361(97)00257-3.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Zhong M, Ma F. Analysis of product distribution and quality for continuous pyrolysis of coal in different atmospheres. J Fuel Chem Technol. 2013;41(12):1427–36.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Lu LM, Sahajwalla V, Harris D. Coal char reactivity and structural evolution during combustion-factors influencing blast furnace pulverized coal injection operation. Metall Mater Trans B. 2001;32(5):811–20. 10.1007/s11663-001-0068-9.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Dong XF, Pinson D, Zhang SJ, Yu AB, Zulli P. Gas-powder flow in blast furnace with different shapes of cohesive zone. Appl Math Model. 2006;30(11):1293–309. 10.1016/j.apm.2006.03.004.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Suzuki T, Smoot LD, Fletcher TH, Smith PJ. Prediction of high-intensity pulverized coal combustion. Combust Sci Technol. 1986;45(3-4):167–83. 10.1080/00102208608923848.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Gong XZ, Guo ZC, Wang Z. Reactivity of pulverized coals during combustion catalyzed by CeO2 and Fe2O3. Combust Flame. 2010;157(2):351–6. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2009.06.025.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Liang P, Wang ZF, Bi JC. Process characteristics investigation of simulated circulating fluidized bed combustion combined with coal pyrolysis. Fuel Process Technol. 2007;88(1):23–8. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2006.05.005.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Li XG, Ma BG, Xu L, Luo ZT, Wang K. Catalytic effect of metallic oxides on combustion behavior of high ash coal. Energy Fuel. 2007;21(5):2669–72. 10.1021/ef070054v.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Kevin AD, Robert HH, Nancy YCY, Thomas H. Evolution of char chemistry, crystallinity, and ultrafine structure during pulverized-coal combustion. Combust Flame. 1995;100(1–2):31–40. 10.1016/0010-2180(94)00062-W.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Li QZ, Lin BQ, Zhao CS, Wu WF. Chemical structure analysis of coal char surface based on Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer. Proc CSEE. 2011;31(32):46–52. 10.1007/s12583-011-0163-z.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Lu LM, Kong CH, Sahajwalla V, Harris D. Char structural ordering during pyrolysis and combustion and its influence on char reactivity. Fuel. 2002;81(9):1215–25. 10.1016/S0016-2361(02)00035-2.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Scaccia S, Calabrò A, Mecozzi R. Investigation of the evolved gases from Sulcis coal during pyrolysis under N2 and H2 atmospheres. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2012;98(11):45–50. 10.1016/j.jaap.2012.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Yuan She et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis