Abstract

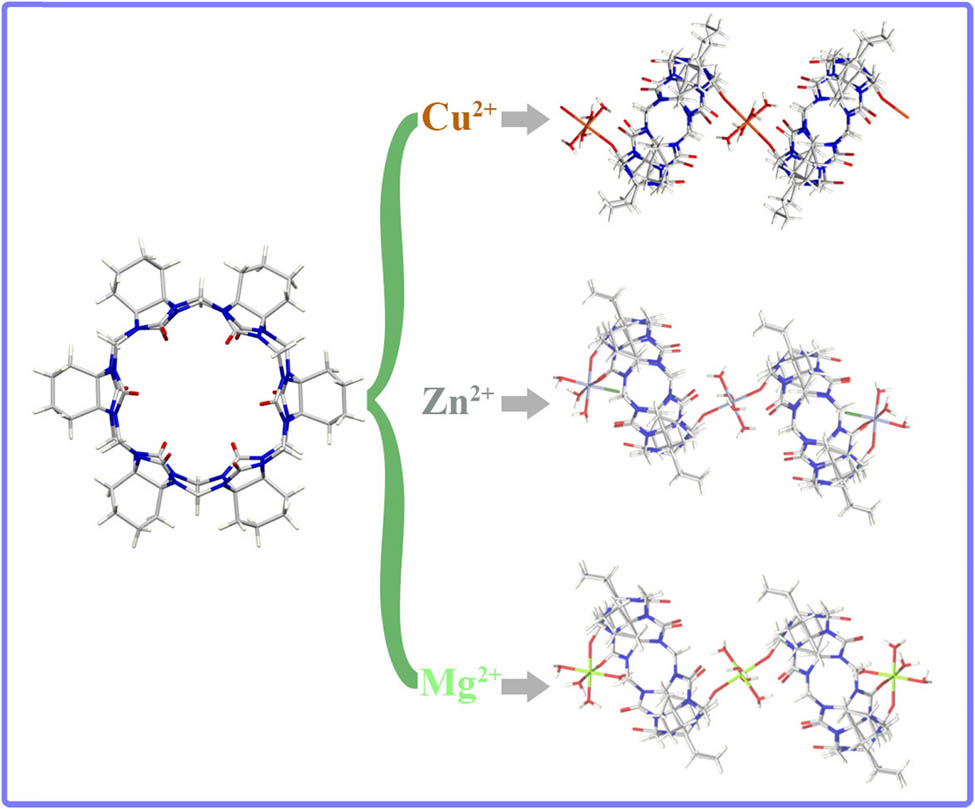

Herein, we report the supramolecular complexes of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril (CyH6Q[6]) with Cu(ClO4)2, Zn(ClO4)2, and Mg(ClO4)2 in formic acid solution. The crystal structure was determined using single crystal X-ray diffraction. The analysis results showed that CyH6Q [6] formed a one-dimensional supramolecular chain with Cu(ClO4)2 and formed a supramolecular assembly with a mixture ratio of 2:3 with Zn(ClO4)2 and Mg(ClO4)2. In this system,

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Cucurbit[n]uril [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] is the fourth generation of macrocyclic compounds after cyclodextrin, crown ether, and calixarene. In 1905, German chemists Behrend et al. obtained a white solid compound through the reaction of glycoluril and paraformaldehyde under acidic conditions [14]. However, because of the problem of solubility, it had not been further studied. It was not until 1981, when the Mock team determined its structure using single crystal X-ray diffraction, that the structure of substance was known [11]. It is a ring compound with a hydrophobic cavity having a neutral potential, two carbonyl ports with a negative potential, and an outer surface with a positive potential. Since then, various cucurbit[n]uril have been discovered one after another and are still being explored [15–18].

However, because the cucurbit[n]uril itself can dissolve only in solutions of formic acid, concentrated acid, and concentrated alkali, the development of cucurbit[n]uril is greatly limited. Through the efforts of some researchers, some modified cucurbit[n]urils such as methyl-, hydroxyl-, cyclopentyl-, and cyclohexyl-substituted cucurbit[n]urils have been reported [19–25]. In the presence of inducers, it is easy to form complexes with various metal ions due to the effect of the outer surface of cucurbit[n]uril [26]. Moreover, cyclohexyl alkyl groups have a stronger ability to bind metal ions due to their electron-pushing effects. Therefore, it leads to an increase in electron cloud density in the ports and an increase in electrostatic repulsion. This increases the cavity of the cucurbit[n]uril and has better performance than ordinary cucurbit[n]uril and the solubility is greatly improved. Therefore, cyclohexyl-substituted cucurbit[n]uril is a kind of cucurbit[n]uril with great generalizing significance. Kim’s research group, which was the first to introduce cyclohexyl into cucurbit[n]uril, reported a series of fully substituted cyclohexyl cucurbits. The experimental results show that fully substituted cyclohexyl cucurbit[5]uril and fully substituted cyclohexyl cucurbit[6]uril have good water solubility [27]. In the Key Laboratory of Macrocyclic and Supramolecular Chemistry of Guizhou Province, a series of Ln–CyH5Q[5] complexes formed by the interaction of fully substituted cyclohexyl cucurbit[5]uril with rare earth metal ions has been reported [28]. A series of Ln–CyH6Q[6] complexes formed by the interaction of fully substituted cyclohexyl cucurbit[6]uril with rare earth metal ions has been reported [29]. There are few studies on the supramolecular complexes constructed by CyH6Q[6] and metal perchlorates.

In this study, CyH6Q[6] (Figure 1) was used as the ligand with Cu(ClO4)2, Zn(ClO4)2, and Mg(ClO4)2 to construct three kinds of supramolecular complexes in formic acid solution. Finally, their structures were determined using single crystal X-ray diffraction.

![Figure 1

Crystal structure of CyH6Q[6]: (a) top view and (b) side view.](/document/doi/10.1515/gps-2021-0074/asset/graphic/j_gps-2021-0074_fig_001.jpg)

Crystal structure of CyH6Q[6]: (a) top view and (b) side view.

2 Experimental

2.1 General materials

All materials and reagents are analytically pure and purchased on the Aladdin platform, used without any further purification. The cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril (CyH6Q[6]) was prepared and purified in accordance with a literature method [24]. The synthesis process of CyH6Q[6] is shown in Scheme 1.

![Scheme 1

The synthesis process of CyH6Q[6].](/document/doi/10.1515/gps-2021-0074/asset/graphic/j_gps-2021-0074_fig_005.jpg)

The synthesis process of CyH6Q[6].

2.2 Preparation of complexes

A mixture of CyH6Q[6] (10 mg, 7.58 μmol) and Cu(ClO4)2·6H2O (5 mg, 13.49 μmol) in 3 mL of formic acid was heated until dissolution. The resultant solution was left to stand at room temperature. A week later, colorless prismatic crystals of complex 1 (C60H84Cl2CuN24O26) were obtained in 40% yield (based on CyH6Q[6]). The crystals of complex 2 (C40H56Cl2ZnN16O20) and complex 3 (C40H56Cl2MgN16O20) were obtained following the method described above for complex 1. The yield of complex 2 was about 50% and of complex 3 was about 46% based on CyH6Q[6].

2.2.1 Instrument characterization methods and test conditions

We selected crystals of an appropriate size and fixed them to a glass filament with Vaseline. Crystal data were collected using a Bruker D8 Venture X-ray single-crystal diffraction machine in scan mode using a graphite monochromatic Mo-K ray (λ = 0.71073 Å, μ = 0.828 mm−1) in ω-scan mode. Lorentz polarization and absorption corrections were applied. Structural solutions and full-matrix least-squares refinements based on F 2 were performed using the SHELXT-14 and SHELXL-14 program packages, respectively. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Analytical expressions for the neutral-atom scattering factors were used and anomalous dispersion corrections were incorporated. Most of the water molecules in the compounds were omitted using the SQUEEZE option in the PLATON program. The main crystal structure parameters are shown in Table 1.

Crystallographic parameters of complexes 1–3

| Complex | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C60H84Cl2CuN24O26 | C40H56Cl2ZnN16O20 | C40H56Cl2MgN16O20 |

| Formula weight | 1691.95 | 1217.27 | 1176.21 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Triclinic | Triclinic |

| Space group | P1̄ | P1̄ | P1̄ |

| a [Å] | 12.972(3) | 12.755(4) | 12.762(2) |

| b [Å] | 15.551(3) | 15.431(7) | 15.463(3) |

| c [Å] | 19.921(4) | 21.533(7) | 21.530(4) |

| α [°] | 98.692(6) | 91.857(16) | 91.961(6) |

| β [°] | 92.474(5) | 98.189(9) | 98.121(6) |

| γ [°] | 105.477(6) | 103.915(14) | 103.958(6) |

| V [Å3] | 3813.7(13) | 4062(3) | 4071.6(12) |

| Z | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| D calcd. [g‧cm−3] | 1.473 | 1.493 | 1.439 |

| T [K] | 273.15 | 273.15 | 273.15 |

| μ [mm−1] | 0.451 | 0.641 | 0.220 |

| Parameters | 1,031 | 1,073 | 1,075 |

| R int | 0.1037 | 0.0572 | 0.1069 |

| R [I > 2σ(I)]a | 0.0999 | 0.0814 | 0.1073 |

| wR [I > 2σ(I)]b | 0.2698 | 0.2424 | 0.3042 |

| R (all data) | 0.1493 | 0.0993 | 0.1565 |

| wR (all data) | 0.2980 | 0.2581 | 0.3417 |

| GOF on F 2 | 1.081 | 1.041 | 1.203 |

aConventional R on Fhkl: ∑||F o| − |F c||/∑|F o|; bWeighted R on |Fhkl|2: ∑[w(F o 2 − F c 2)2]/∑[w(F o 2)2]1/2.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Description of the crystal structure of complexes 1–3

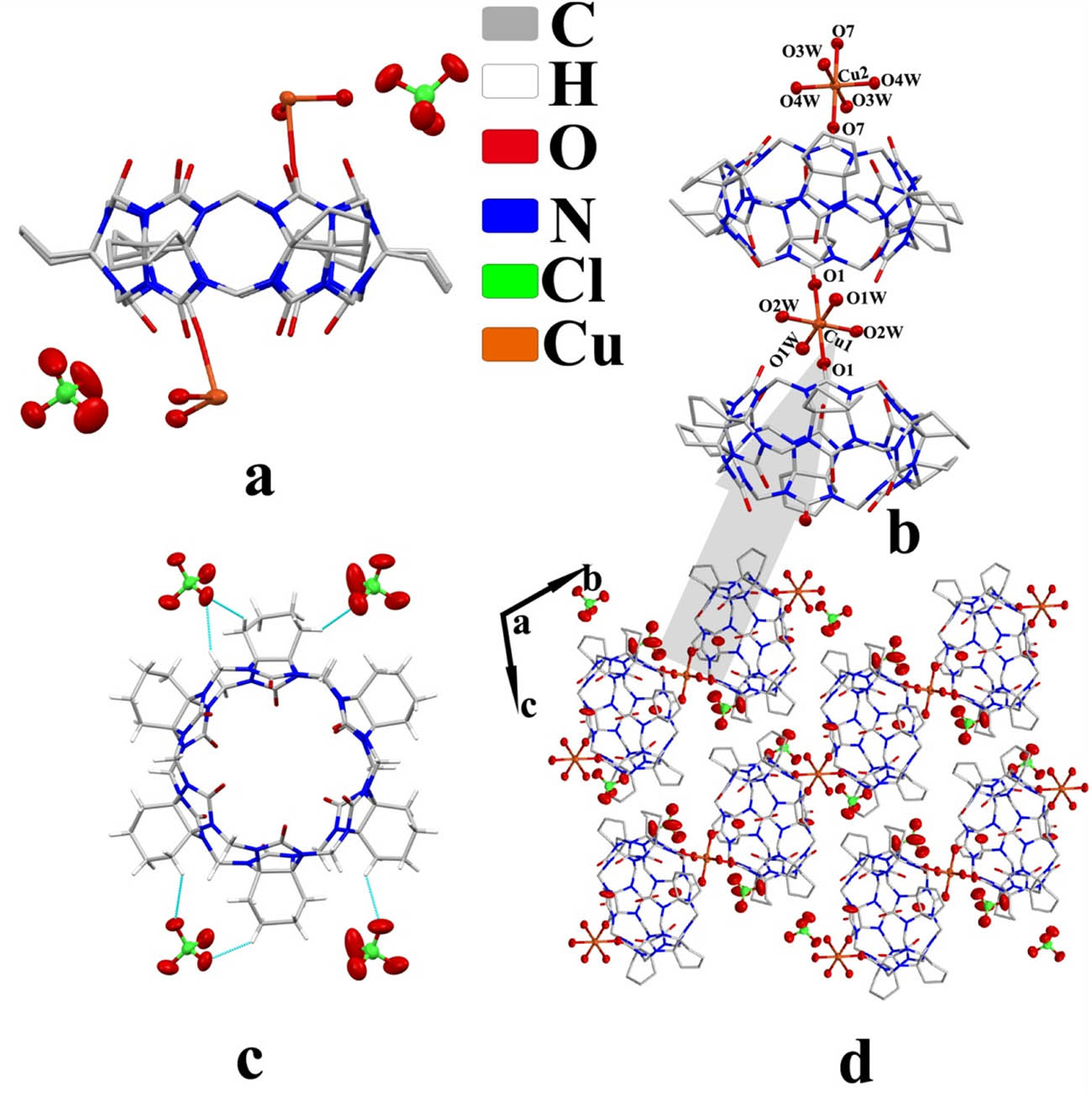

Complex 1 exhibited the triclinic P1̄ space group. The asymmetric unit structure contained one CyH6Q[6] molecule, two counter

Crystal structure of complex 1: (a) asymmetric unit, (b) coordinate bond, (c) ion–dipole interaction, and (d) two-dimensional structure viewed along the a-axis.

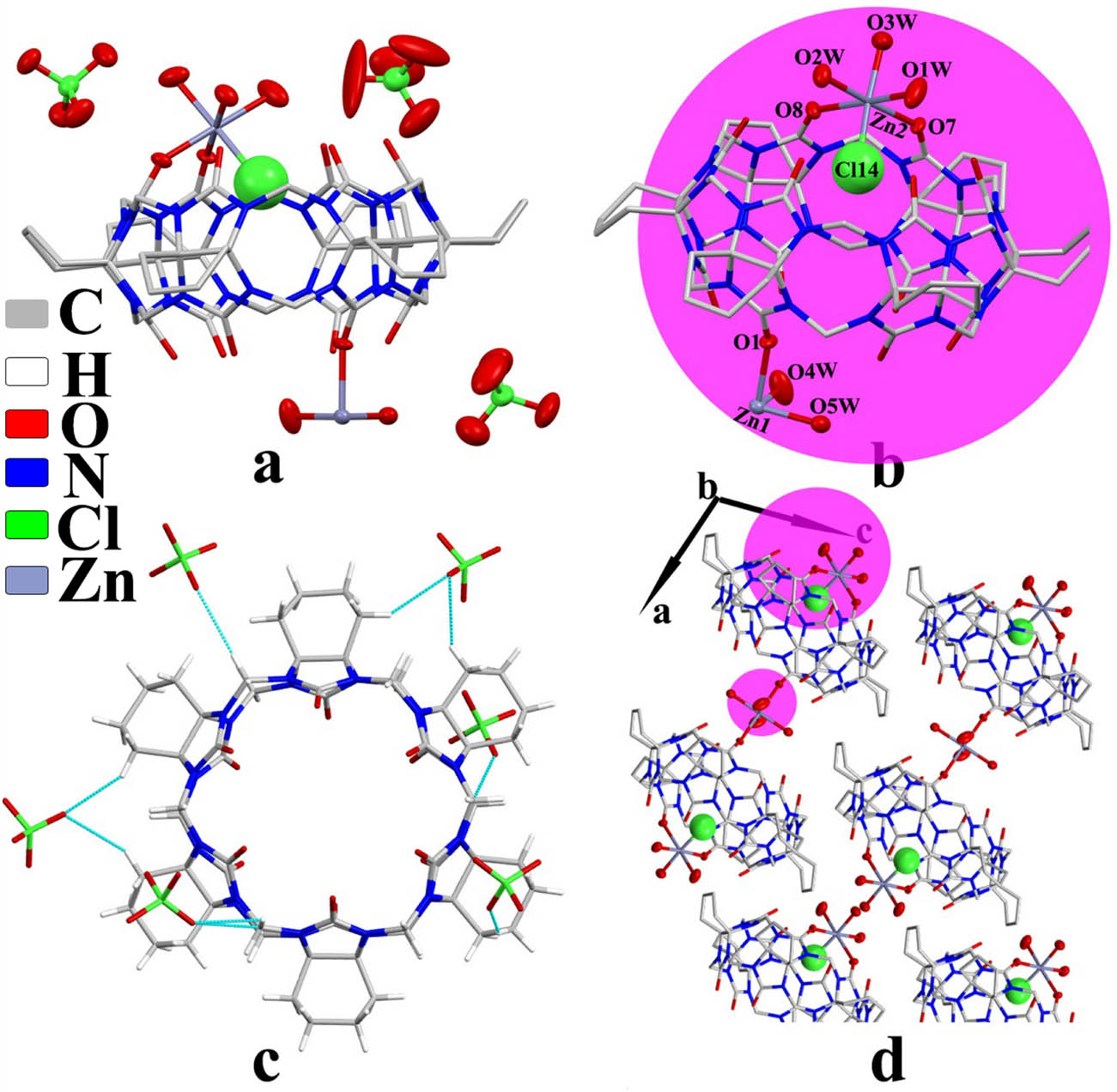

Complex 2 exhibited the triclinic P1̄ space group. The asymmetric unit structure contained one CyH6Q[6] molecule, three counter

Crystal structure of complex 2: (a) asymmetric unit, (b) coordinate bond, (c) ion–dipole interaction, and (d) two-dimensional structure viewed along the b-axis.

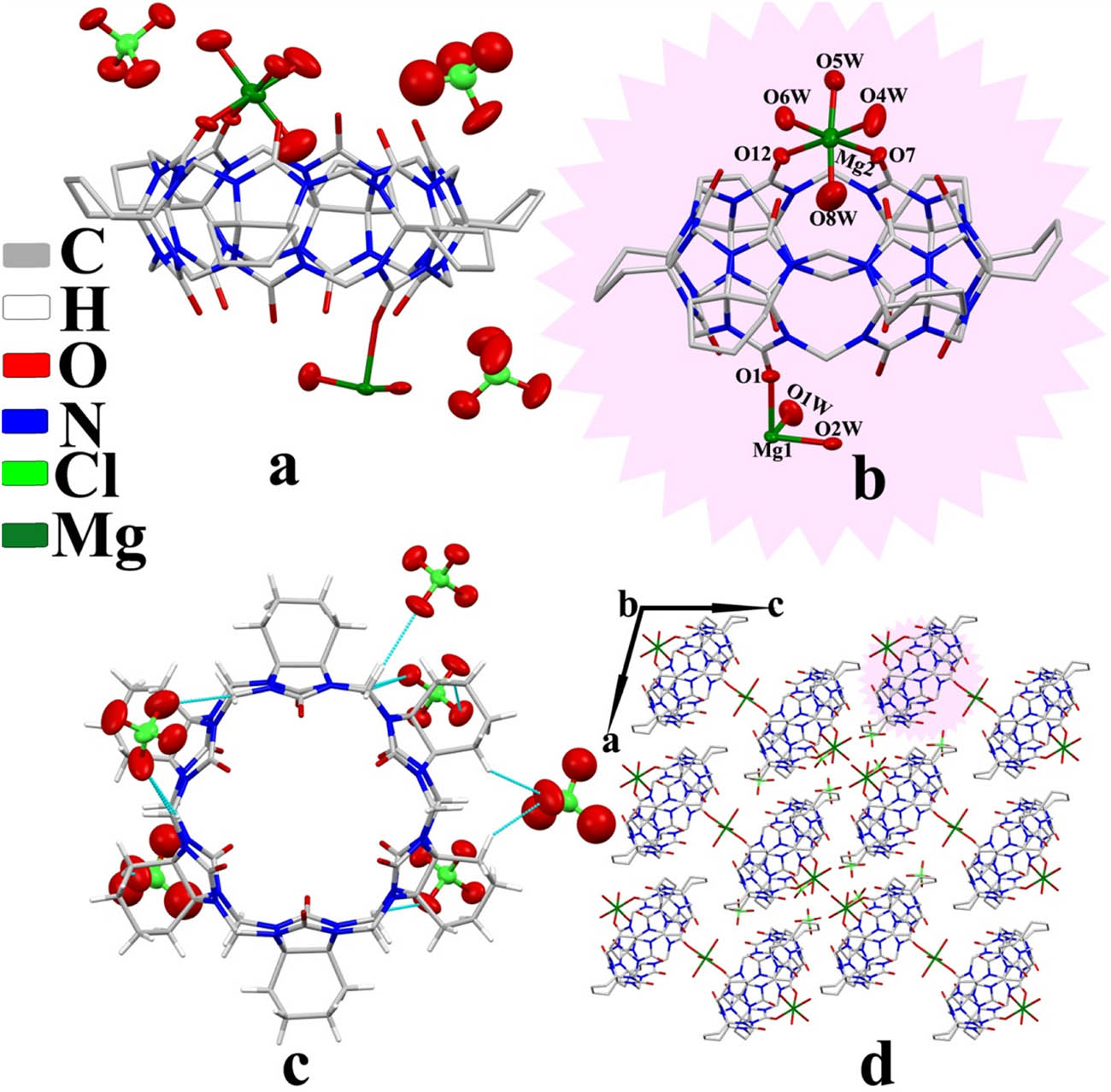

Complex 3 exhibited the triclinic P1̄ space group. The asymmetric unit structure contained one CyH6Q[6] molecule, three counter

Crystal structure of complex 3: (a) asymmetric unit, (b) coordinate bond, (c) ion–dipole interaction, and (d) two-dimensional structure viewed along the b-axis.

4 Conclusion

Complexes 1–3 were constructed using CyH6Q[6] and Cu(ClO4)2, Zn(ClO4)2, and Mg(ClO4)2, respectively, in formic acid aqueous solution. The experimental results showed that complex 1 formed a two-dimensional stacking model in the presence of coordination and ion–dipole interaction. The coordination configurations of complexes 3 and 2 were similar. The difference was that the central Mg2+ of complex 3 did not form coordination bonds with chloride ions, whereas the central Zn2+ of complex 2 formed coordination bonds with chloride ions. Complex 2 was different from complexes 1 and 3 in that it not only coordinated with carbonyl oxygen and water molecules but also with chloride ions. This study further helped to fill the research gap of CyH6Q[6]. At the same time, it provided a theoretical basis for cucurbit[n]urils in the fields of carrier catalyst, collection, precipitation, adsorption, enrichment, and recovery.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21762011), Guizhou Science and Technology Planning Project (Guizhou Science and Technology Cooperation Platform Talent [2017]5788) and the Guizhou Province Graduate Education Innovation Project (No. YJSCXJH [2020] 188).

-

Author contributions: Jun Zheng: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, formal analysis; Lin Zhang: writing – original draft, formal analysis; Xinan Yang: visualization, project administration; Yanmei Jin: resources, writing – review and editing, supervision, data curation; Jie Gao: resources, writing – review and editing, supervision, data curation; Peihua Ma: writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The X-ray crystallographic data for structures reported in this study have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center under accession numbers CCDC: 2055928 (1), 2055951 (2), and 2055947 (3). These data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk//data_request/cif.

References

[1] Lagona J, Mukhopadhyay P, Chakrabarti S, Isaacs L. The cucurbit[n]uril family. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2005;44:4844–70.10.1002/anie.200460675Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Lee JW, Samal S, Selvapalam N, Kim HJ, Kim K. Cucurbituril homologues and derivatives: new opportunities in supramolecular chemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:621–30.10.1021/ar020254kSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Gerasko OA, Samsonenko DG, Fedin VP. Supramolecular chemistry of cucurbiturils. Russ Chem Rev. 2002;71:741–60.10.1070/RC2002v071n09ABEH000748Search in Google Scholar

[4] Elemans JAAW, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. Self-assembled architectures from glycoluril. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2000;39:3419–28.10.1021/ie000079gSearch in Google Scholar

[5] Cintas P. Cucurbituril: supramolecular perspectives for an old ligand. J Incl Phenom Mol Recogn Chem. 1994;17:205–20.10.1007/BF00708781Search in Google Scholar

[6] Yang RY, Deng XY, Huang Y, Zhang YQ, Tao Z. Recognition of lanthanide metal cations by t-DSMI@alkyl-substituted cucurbit[6]uril probes. Chem. 2020;5:8649–55.10.1002/slct.202000021Search in Google Scholar

[7] Lin RL, Li R, Shi H, Zhang K, Meng D, Sun WQ, et al. Symmetrical-tetramethyl-cucurbit[6]uril-driven movement of cucurbit[7]uril gives rise to heterowheel [4]pseudorotaxanes. J Org Chem. 2020;85:3568–75.10.1021/acs.joc.9b03283Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Day A, Arnold AP, Blanch RJ, Snushall B. Controlling factors in the synthesis of cucurbituril and its homologues. J Org Chem. 2001;66:8094–100.10.1021/jo015897cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Jansen K, Buschmann HJ, Wego A, Dopp D, Mayer C, Drexler HJ, et al. Cucurbit[5]uril, decamethylcucurbit[5]uril and cucurbit[6]uril. synthesis, solubility and amine complex formation. J Incl Phenom Macro. 2001;39:357–63.10.1023/A:1011184725796Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kim J, Jung IS, Kim SY, Lee E, Kang JK, Sakamoto S, et al. New cucurbituril homologues: syntheses, isolation, characterization, and x-ray crystal structures of cucurbit[n]uril (n = 5, 7, and 8). J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:540–1.10.1021/ja993376pSearch in Google Scholar

[11] Freeman WA, Mock WL, Shih NY. Cucurbituril. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:7367–8.10.1021/ja00414a070Search in Google Scholar

[12] Xu HP, Lin D, Zhang B, Huo Y, Lin SF, Liu C, et al. Supramolecular self-assembly of a hybrid ‘hyalurosome’ for targeted photothermal therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Drug delivery. 2020;27:378–86.10.1080/10717544.2020.1730521Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Day AI, Blanch RJ, Arnold AP, Lorenzo S, Lewis GR, Dance I. A cucurbituril-based gyroscane: a new supramolecular form. Angew Chem Intedit. 2002;41:275–7.10.1002/1521-3757(20020118)114:2<285::AID-ANGE285>3.0.CO;2-6Search in Google Scholar

[14] Behrend R, Meyer F, Rusche F. Condensation products from glycoluril and formaldehyde. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1905;339:1–37.10.1002/jlac.19053390102Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zheng J, Zhao WW, Meng Y, Jin YM, Ma PH. Supramolecular self-assembly of cyclopentyl substituted cucurbit[n]uril with Fe3+, Fe2+, and HClO4 based on outer surface interaction. Cryst Res Technol. 2021;56:2000183.10.1002/crat.202000183Search in Google Scholar

[16] Liu SM, Ruspic C, Mukhopadhyay P, Chakrabarti S, Zavalij PY, Isaacs L. The cucurbit[n]uril family: prime components for self-sorting systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15959–67.10.1021/ja055013xSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Isaacs L, Park SK, Liu SM, Ko YH, Selvapalam N, Kim Y, et al. The inverted cucurbit[n]uril family. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:18000–1.10.1021/ja056988kSearch in Google Scholar

[18] Zhao YJ, Xue SF, Zhu QJ, Tao Z, Zhang JX, Wei ZB, et al. Synthesis of a symmetrical tetrasubstituted cucurbit[6]uril and its host-guest inclusion complex with 2,2′-bipyridine. Chin Sci Bull. 2004;49:1111–6.10.1360/04wb0031Search in Google Scholar

[19] Flinn A, Hough GC, Stoddart JF, Williams DJ. Decamethylcucurbit[5]uril. Angew Chem Int Edit. 1992;31:1475–7.10.1002/anie.199214751Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zhao JH, Kim HJ, Oh JH, Kim SY, Lee JW, Sakamoto S, et al. Cucurbit[n]uril derivatives soluble in water and organic solvents. Angew Chem. 2001;113:4363–5.10.1002/1521-3757(20011119)113:22<4363::AID-ANGE4363>3.0.CO;2-BSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Wu F, Wu LH, Xiao X, Zhang YQ, Xue SF, Tao Z, et al. Locating the cyclopentano cousins of the cucurbit[n]uril family. J Org Chem. 2012;77:606–11.10.1021/jo2021778Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Tian ZC, Ni XL, Xiao X, Wu F, Zhang YQ, Zhu QJ, et al. Interaction models of three alkyl substituted cucurbit[6]urils with a hydrochloride salt of 4,4′-dipyridyl guest. J Mol Struct. 2007;888:48–54.10.1016/j.molstruc.2007.11.029Search in Google Scholar

[23] Jon SY, Selvapalam N, Oh DH, Kang JK, Kim SY, Jeon YJ, et al. Facile synthesis of cucurbit[n]uril derivatives via direct functionalization: expanding utilization of cucurbit[n]uril. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10186–87.10.1021/ja036536cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Isobe H, Sato S, Nakamura E. Synthesis of disubstituted cucurbit[6]uril and its rotaxane derivative. Org Lett. 2002;4:1287–9.10.1021/ol025749oSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Jin YM, Huang TH, Zhao WW, Yang XN, Meng Y, Ma PH. A study on the self-assembly mode and supramolecular framework of complexes of cucurbit[6]urils and 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)piperazine. RSC Adv. 2020;10:37369–73.10.1039/D0RA07988JSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Chen K, Kang YS, Zhao Y, Yang JM, Lu Y, Sun WY. Cucurbit[6]uril-based supramolecular assemblies: possible application in radioactive cesium cation capture. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16744–7.10.1021/ja5098836Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Zhao J, Kim HJ, Oh J, Kim SY, Lee JW, Sakamoto S, et al. Cucurbit[n]uril derivatives soluble in water and organic solvents. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:4233–5.10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4233::AID-ANIE4233>3.0.CO;2-DSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Liu JX, Hu YF, Lin RL. Coordination complexes based on pentacyclo-hexano-cucurbit[5]uril and lanthanide(III) ions: lanthanide contraction effect induced structural variation. Cryst Eng Comm. 2012;14:6983–9.10.1039/c2ce25866hSearch in Google Scholar

[29] Qin X, Ni XL, Hu JX, Chen K, Zhang YQ, Redshaw C, et al. Macrocycle-based metal ion complexation: a study of lanthanide contraction effect towards hexacyclo-hexanocucurbit[6]uril. Cryst Eng Comm. 2013;15:738–44.10.1039/C2CE26225HSearch in Google Scholar

© 2021 Jun Zheng et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis