Abstract

Blue mold caused by Penicillium species is a major fungal disease threatening the viticulture industry in Pakistan, responsible for deteriorating the quality of grapes during handling, transportation, and distribution. Identification-based approaches of Penicillium species provide a better strategy on accurate diagnosis and effective management. In this study, 13 isolates were recovered from symptomatic grape bunches at five main fruit markets of Rawalpindi district, Punjab province. Based on morphological data and multi-loci phylogenetic analysis, the isolates were identified as two distinct species viz. Penicillium expansum (eight isolates) and Penicillium crustosum (five isolates). Meanwhile, the pathogenicity test of Penicillium isolates presented by the inoculation of grape bunches showed various degrees of severity. For improving the fruit quality and eliminating the needs of synthetic fungicides, botanicals such as thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.), garlic (Allium sativum L.), ginger (Zingiber officinale L.), and carum (Carum capticum L.) essential oils (EOs) at concentrations of 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/mL were evaluated. In vitro studies indicated that thyme EO showed a highly significant reduction of fungal growth. Furthermore, the experiments related to reducing the decay development and average weight loss percentage of grapes revealed similar findings. Based on the results of this study, it is recommended that thyme EO can be used as an eco-friendly botanical fungicide against Penicillium spp. causing blue mold disease.

1 Introduction

Grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) are a widely cultivated fruit in Pakistan for fresh consumption, covering over an area of about 15,000 ha with an annual production of 57,000 tons [1]. Due to the nutritive and economic values, it was considered as the “queen of fruit” [2]. Despite being known for the most nutritious and medicinal values, grapes are one of the perishable fruits that have a short shelf life of about 2–3 days at ambient temperature. The susceptibility to Penicillium genus is the main cause towards reduced shelf life, deteriorating the berries and increasing market losses up to 50%. This pathogen not only is responsible for weight loss, colour changes, and softening of berries but also produces mycotoxins that may be harmful to human [3]. Penicillium is the most important genus of saprophytic fungi, with over 400 described species distributed worldwide [4]. Symptomology and morphological characterization are traditional approaches for species-level identification of Penicillium species; therefore, modern molecular techniques such as PCR amplification and sequence analysis have been successfully proved an effective tool for the diagnosis of this fungi with associated species [5]. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rDNA sequence is the commonly used universal sequenced marker for the identification of fungi up to the species level. Unfortunately, the ITS sequence diagnosis is not enough for Penicillium species distinguishing among all closely related species [6]. Because of the limitations associated with the ITS, several additional gene regions, including β-tubulin and calmodulin, have been used to distinguish closely related Penicillium species [7,8]. Previous literature indicated that the management of postharvest decaying pathogens is accomplished by several synthetic fungicides (chemical methods), which badly affect the physical structure of grape berries and pose serious health hazards in humans [9]. These synthetic fungicides on fruits cause two major problems: first, contamination of fruits with fungicidal residues, and second, they induce resistance in the pathogen populations. Food safety is one of the major concerns related to fresh fruits and vegetables. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Environment Program, it is estimated that millions of individuals associated with agriculture in developing countries suffered severe pesticide toxicity and approx. 18,000 die every year [10]. Researchers have successfully found some alternatives for the control of postharvest spoilage fungi in the form of botanicals such as plant essential oils (EOs) [11]. Plant EOs also known as secondary metabolites are natural, volatile, and aromatic liquid compounds that are non-toxic to humans, highly effective against postharvest pathogens, and can be further exploited to replace hazardous environment deteriorating artificial fungicides [12,13].

Keeping in view the aforementioned facts, the overarching goal of our work is to find a rapid, convenient, and accurate way to identify Penicillium species involved in blue mold and develop a novel strategy to control this pathogen infecting grapes employing plant EOs, which are environmentally sustainable, economical, and easy to access.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Cultural, morphological characterization, and mycotoxin detection

A survey was conducted in July 2016 in five different main fruit markets of Rawalpindi (33°38′19.2″N, 73°01′45.0″E) district. Infected samples of grapes cv. Perlette were collected based on symptoms as initially brown followed by lesion expansion and later on bluish mycelium spread on the surface of the whole bunch shown in Figure 1. For isolation, small portions of about 3–5 mm2 of symptomatic fruit samples were excised at the lesion margin. The segments were surface disinfected with 2% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, rinsed twice in distilled water, dried out on sterilized filter paper for 2 min to remove excess moisture, and placed on Petri dishes (4–5 segments per dish) containing potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium. The Petri dishes were incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 3 days and checked regularly for fungal colonization. After 3 days, the diameter of each colony was measured and identified based on cultural and morphological characteristics by using fungal taxonomic keys [14]. To obtain a preliminary analysis of mycotoxins (patulin and citrinin), the isolates were cultured in potato dextrose broth at 25°C for 7 days and extracted using an organic solvent extraction method [15]. A total of 20 mL of potato dextrose broth from growing cultures was extracted three times with 25 mL of ethyl acetate by shaking vigorously for 1 min each time. Then, the organic phases were combined. Five drops of glacial acetic acid were added to the combined organic phase solution, and the solution was evaporated to dryness in a 40°C water bath under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. The dried residue was immediately dissolved in 1 mL of acetic acid buffer solution. Acetate buffer was prepared by adding 0.45 mL of glacial acetic acid and 0.245 g of sodium acetate trihydrate to 40 mL of double-distilled water (ddH2O). The pH was adjusted to 4.0 with glacial acetic acid. The volume was then adjusted to 50 mL with ddH2O. The toxins in the extracted sample were subjected to thin layer chromatography [16].

Symptomology of blue mold disease associated with Penicillium spp.

2.2 Pathogenicity test

A pathogenicity test was conducted for the confirmation of highly virulent isolates. For this purpose, asymptomatic grape bunches were surface sterilized with running tap water. Injuries were made with the help of sterile needle to fruits up to 5 mm diameter and placed in a disc of fungal isolates, whereas control bunches were inoculated with distilled water. Bunches were placed in a sterile thermo-pole box (one bunch per box) and stored at 25°C for 3 days. Three replicates were used for each treatment [17]. The disease is scored with modification following [18] 0–5 disease rating scale, where 0 = berries without rot, 1 = 0–10%, 2 = 10–25%, 3 = 25–50%, 4 = 50–75%, and 5 = more than 75%.

2.3 Molecular characterization

DNA was extracted and purified by using Prepman DNA extraction kit (Thermo Fisher) and GeneJet purification kit, respectively. Each source culture was derived from a single conidium on PDA medium. Mycelium of each isolate was used for DNA extraction. Amplification of the extracted DNA was performed by using PCR. For molecular identification of Penicillium species, primers specific for ITS, benA, and CaM loci were selected for PCR amplification (Table 1) Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was carried out by using the programmable thermocycler Bio-Rad T100 as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR product was analysed on 1% agarose gel electrophoresis by staining with ethidium bromide as a staining agent. After positive band detection on a gel, all isolates were subjected to purification amplified DNA by using the GeneJet purification kit (KT-00701) by following the standard protocol of the manufacturer. After purification, the PCR products were sent to Macrogen Korea Inc. for sequencing in both directions through Sanger Sequencer. The sequences generated in this study were aligned and submitted to GenBank and accession numbers were obtained. Datasets of the ITS, ben A, and CaM genes were used for phylogenetic analysis. After confirmation of isolates, sequences were aligned by the MUSCLE (Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation) method [19], and the neighbour-joining method was performed in MEGA v. 7 for phylogenetic analysis [20].

Primers used for Penicillium species identification

| Gene | Primers | Sequences (5′→3′) | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | ITS 1F | CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA | ∼600 |

| ITS 4R | TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC | ||

| β-Tubulin (benA) | Bt2a | GGTAACCAAATCGGTGCTGCTTTC | ∼550 |

| Bt2b | ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC | ||

| Calmodulin (CaM) | CF1 | GCCGACTCTTTGACYGARGAR | ∼750 |

| CF4 | TTTYTGCATCATRAGYTGGAC |

2.4 Preparation of plant EOs

Matured leaves of thyme, seeds of fennel and carum, clove of garlic, and rhizome of ginger were obtained from Rawalpindi herbal store. These botanical materials were ground well in a grinder machine and subjected to the extraction process through Soxhlet apparatus by following ref. [21]. Finally, the extracted plant EOs are put in clean glass vials and stored in a refrigerator at 4°C until further tests.

2.5 In vitro screening of plant EOs

2.5.1 In vitro contact assay method

To find out the effect of different plant EOs on mycelial growth of Penicillium expansum and Penicillium crustosum, poisoned food technique was used. For this purpose, 50 mL of prepared PDA medium was kept in 100 mL conical flasks, sterilized for 20 min, and kept under the sterilized hood to cool up to 60°C, and then plant EOs were added to each flask and shook gently to prepare PDA medium with concentrations of 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/mL. PDA containing known concentrations of plant EOs was poured into 9 cm Petri plates. Then, 5 mm plugs of 7-day-old culture of Penicillium spp. were kept in the centre of each Petri plate, whereas in control sets PDA free of any EOs was used. After that Petri dishes were incubated at ±25°C for 3 days, and finally, mycelial growth inhibition percentage (I%) was recorded by using the following formula [22]:

where d c is the diameter of control and d t is the diameter of treatment. Analysis was replicated three times.

2.6 Qualitative phytochemical analysis of plant EOs

To find out the antifungal compounds such as phenolics, alkaloids, terpenoids [23], and saponins [24] in plant EOs various phytochemical tests were performed (Table 2).

Antifungal compounds, tests, and colour indications

| Anti-fungal compound | Tests | Colour indications |

|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Salkowski test | Dark blue |

| Alkaloids | Wagner reagent | Dark brownish to black |

| Phenols | Ferric chloride | Yellowish to green |

| Saponins | Saponin test | Foam-like appearance |

2.7 Comparison of the fungi toxicity of the selected plant EO with synthetic fungicides

The efficacy of the oils was compared with some fungicides, viz. benzimidazole, diphenylamine, phenylmercuric acetate, and zinc dimethyl dithiocarbamate, by the usual poisoned food technique.

2.8 Fungitoxic properties of the selected plant EO

The effect of increased inoculum density of the test fungus on fungitoxicity of the oil was studied by following ref. [25] at their respective mycelial inhibition concentration (MIC) values. The effect of storage and temperature on the fungitoxicity of the EO was evaluated according to ref. [26]. The range of fungitoxicity of the oil was determined at their respective toxic and hypertoxic concentrations by the poisoned food technique.

2.9 Physicochemical properties of the selected plant EO

The oils were standardized through physicochemical properties, viz. specific gravity, refractive index, acid number, saponification value, ester value, and phenolic content, which were estimated by following ref. [27].

2.10 Application of plant EO in grape bunches

After in vitro screening and phytochemical analysis, the selected plant EO is used to find out the efficacy against major both Penicillium spp. causing blue mold of grapes. For this purpose, bunches of grapes cv. Perlette are used, which are surface sterilized with distilled water, dipped for 2 min in the prepared plant EO, placed on the perforated thermo-pole box (one bunch/box), and finally the inoculum is sprayed with 40 µL of spore suspension.

2.10.1 Decaying incidence percentage (DIP) determination

Decaying percentage was calculated by using the following formula at 3 days of interval:

where A is the fungal infected berries in a bunch and B is the total berries in bunch examined. Three replicates were kept for treatment along with the control sets and scored with the decay rating scale, where 0 = no symptoms, 1 = up to 10%, 2 = 11–25%, 3 = 26–40%, 4 = 40–60%, and 5 = above 60%.

2.10.2 Measurement of average weight (AW) loss

The AW loss measured after 3 and 6 days of storage and calculated by using the following formula followed in ref. [28]. The layout of the experiment included three replications of each treatment along with the control set:

where A is the original fruit weight after storage and B is the final fruit weight.

2.11 Statistical analysis

The results were subjected to statistical analysis using Statistix ver. 8.1. The mean values were separated using Tukey’s HSD test at P ≤ 0.05 after analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant and non-significant interactions were explained based on ANOVA.

3 Results

3.1 Cultural and morphological identification, mycotoxin detection, and pathogenicity analysis

Thirteen isolates of Penicillium spp. causing blue mold of grapes were recovered from five different locations of main fruit markets in Rawalpindi district. Based on their morphology and diversity with respect to location from which the isolates were obtained, the isolate number, source, and morphological characteristics viz. colony colour, shape of conidiophore, length, width of conidia, and conidial shape are listed in Table 3. Using traditional means, the 13 isolates were identified tentatively as belonging to two different Penicillium species: Penicillium expansum (eight isolates: Pen 01, Pen 02, Pen 03, Pen 06, Pen 08, Pen 11, Pen 17, and Pen 18) and Penicillium crustosum (five isolates; Pen c 02, Pen c 03, Pen c 04, Pen c 05, and Pen c 05) shown in Figure 2.

Penicillium spp. isolate ID with morphological characteristics (under colony) heading: CC = colony colour and microscopic characterization (under conidiophore), S = shape (Conidia) heading, S = shape, L = length, B = breadth, and mycotoxin production of 13 Penicillium isolates; ± standard deviation calculated by number of readings = 30

| Colony | Conidiophore | Conidia | Mycotoxin detectiona | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. no. | Isolation ID | Location (source) | CC | S | S | L (µm) | B (µm) | Patulin | Citrinin | Pathogenicityb test |

| 1 | Pen 1 | Rawalpindi | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Ellipsoidal | 3.16 ± 0.14 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | + | + | 5 |

| 2 | Pen 2 | Gujar Khan | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Spherical | 3.17 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | + | − | 3 |

| 3 | Pen 3 | Rawat | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Ellipsoidal | 3.34 ± 1.15 | 2.4 ± 0.25 | + | + | 5 |

| 4 | Pen c 02 | Rawalpindi | White to greyish-green sporulation with white margins | Tetra-verticillate | Ellipsoidal | 3.3 ± 0.45 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | ± | ± | 4 |

| 5 | Pen c 03 | Islamabad | White to greyish-green sporulation with white margins | Tetra-verticillate | Spherical | 3.02 ± 0.04 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | − | − | 1 |

| 6 | Pen 6 | Texilla | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Subglobose | 3.17 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | − | + | 3 |

| 7 | Pen 8 | Gujar Khan | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Ellipsoidal | 4.18 ± 1.8 | 2.6 ± 0.89 | + | + | 5 |

| 8 | Pen 11 | Islamabad | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Spherical | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | ± | ± | 4 |

| 9 | Pen c 04 | Rawalpindi | White to greyish-green sporulation with white margins | Tetra-verticillate | Ellipsoidal | 3.6 ± 0.13 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | + | + | 5 |

| 10 | Pen 17 | Texilla | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Subglobose | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | + | − | 3 |

| 11 | Pen 18 | Rawat | White to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins | Mono-verticillate | Ellipsoidal | 3.34 ± 1.15 | 1.96 ± 1 | + | + | 5 |

| 12 | Pen c 05 | Islamabad | White to greyish-green sporulation with white margins | Tetra-verticillate | Spherical | 3.24 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | + | + | 5 |

| 13 | Pen c 06 | Rawalpindi | White to greyish-green sporulation with white margins | Tetra-verticillate | Ellipsoidal | 3.26 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | − | − | 2 |

- a

The mycotoxins patulin and citrinin were detected by organic solvent extraction followed by thin layer chromatography (TLC) separation and visualization under UV light at 365 nm wave length; ±: low level faint band on TLC plate and it is unclear whether the mycotoxin is produced or not; +: mycotoxin present; −: mycotoxin not detected

- b

Pathogenicity test = (0) no bunch rot, (1) 0–10%, (2) 10–25%, (3) 25–50%, (4) 50–75%, and (5) more than 75%.

(a–d) Morphological characteristics of Penicillium spp. (a and c) Bluish-green colony colour without white margins along with mono-verticillate conidiophore identified as Penicillium expansum. (b and d) Greyish green colony colour with white margins and tetra-verticillate conidiophore identified as Penicillium crustosum.

In preliminary mycotoxin analysis, P. expansum isolates (Pen 01, Pen 03, Pen 08, and Pen 18) produced both patulin and citrinin, whereas Pen 02 and Pen 17 produced only patulin. In the case of isolate Pen 11, low level of mycotoxins was detected. For P. crustosum, isolates Pen c 04 and Pen c 05 produced both mycotoxins, whereas Pen c 03 and Pen c 06 did not produce detectable mycotoxin (Table 3).

Pathogenicity test revealed that five isolates of both Penicillium spp. viz. Pen 01, Pen 03, Pen 08, Pen c 04, and Pen c 05 were highly virulent, causing more than 75% rotting on bunches and fall fifth in the disease rating scale (Table 3).

3.2 Sequence analysis of Penicillium spp. and phylogenetic analysis

Three sets of primers were chosen to amplify three marker genes (ITS, BenA, and CaM) from the 13 Penicillium isolates. Using these primers, amplified sequences were submitted to GenBank, and their accession numbers are listed in Table 4. The initial species identifications based on traditional criteria were largely confirmed by sequence analysis.

Accession numbers of amplified nucleotide sequences from Penicillium spp. isolates

| Penicillium spp. | Isolation ID | ITS | ben A | CaM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 01 | MT294660.1 | MT387276.1 | MT387286.1 |

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 02 | MT294661.1 | MT387277.1 | MT387287.1 |

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 03 | MT294662.1 | MT387278.1 | MT387288.1 |

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 06 | MT294663.1 | MT387279.1 | MT387289.1 |

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 08 | MT294664.1 | MT387280.1 | MT387290.1 |

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 11 | MT294665.1 | MT387281.1 | MT387291.1 |

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 17 | MT294666.1 | MT387284.1 | MT387294.1 |

| Penicillium expansum | Pen 18 | MT294667.1 | MT387285.1 | MT387295.1 |

| Penicillium crustosum | Pen c 02 | MT298909.1 | MT387257.1 | MT387267.1 |

| Penicillium crustosum | Pen c 03 | MT298910.1 | MT387258.1 | MT387268.1 |

| Penicillium crustosum | Pen c 04 | MT298911.1 | MT387259.1 | MT387269.1 |

| Penicillium crustosum | Pen c 05 | MT298912.1 | MT387260.1 | MT387270.1 |

| Penicillium crustosum | Pen c 06 | MT298913.1 | MT387261.1 | MT387271.1 |

Phylogenetic trees were made with each individual gene: ITS (Figure 3), benA (Figure 4), and CaM (Figure 5). In building the phylogenetic tree, MUSCLE alignment was made between 13 sequenced isolates of Penicillium spp. amplified with three marker genes along with previously identified reference sequences of Penicillium spp. available in the databases. For phylogenetic analysis of ITS, β-tubulin, and calmoduline regions of Penicillium spp. The reference sequences that were used are P. atrofulvum, P. anatolicum, P. bilaiae, P. adametzioides, P. sclerotiorum, P. adametzii, P. aurantioviolaceum, P. carneum, P. brunneoconidiatum, P. araracuarense, P. brasilianum, P. brefaldianum, P. caperatum, P. alfredii, P. brocae, P. atrovenetum, P. bovifimosum, P. atramentosum, P. glandicola, P. rabsamsonii, P. astrolabium, P. bialowiezens, P. canescens, P. abidjanum, P. allii-sativi, P. chrysogenum, P. cellarum, P. paneum, P. commune, and P. brevicompactum, respectively. Furthermore, Phytophthora parasitica was used as outgroup among all amplified regions during phylogenetic tree construction shown in Figures 3–5.

Phylogenetic tree based upon MUSCLE alignment of the ITS region of rDNA nucleotide sequences of Penicillium isolates causing blue mold disease of grapes. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour-joining method. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.995574 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 86 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 275 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. The tree is rooted with Phytophthora parasitica isolate (JQ446446.1).

Phylogenetic tree based upon MUSCLE alignment of the β-tubulin region nucleotide sequences of Penicillium isolates causing blue mold of grapes. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour-joining method. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 1.55153106 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 57 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 181 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. The tree is rooted with Phytophthora parasitica isolate (KR632886.1).

Phylogenetic tree based upon MUSCLE alignment of the calmodulin region nucleotide sequences of Penicillium isolates causing fruit rots of grapes. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour-joining method. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.99983118 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 67 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 181 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. The tree is rooted with Phytophthora parasitica isolate (XM_008910540.1).

3.3 In vitro evaluation of plant EOs against Penicillium spp.

3.3.1 In vitro contact assay method

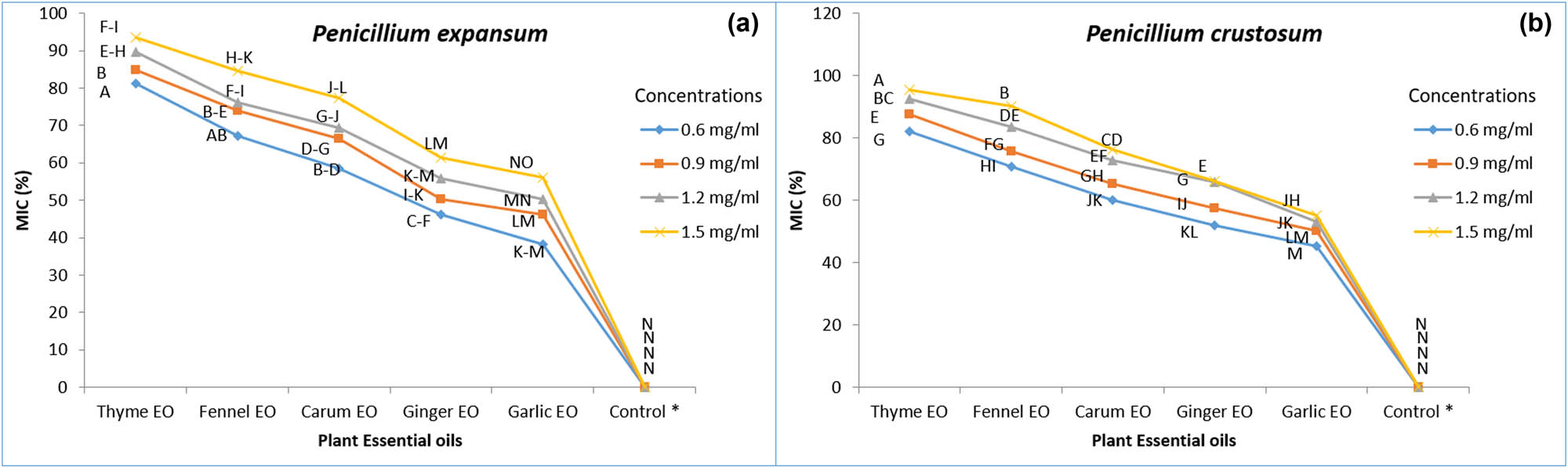

The effects of five plant EOs at four different concentrations viz. 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/mL were tested on mycelial growth of two Penicillium spp. (Penicillium expansum; isolate ID: Pen 3 and Penicillium crustosum; isolate ID: Pen c 04) under in vitro conditions.

3.3.1.1 Efficacy of plant EOs against Penicillium expansum

In vitro application of plant EOs revealed that from the five selected plant EOs, thyme EO showed maximum effectiveness to inhibit the growth of highly pathogenic isolate (Pen 03) of P. expansum (81.3%, 84.8%, 89.7%, and 93.6%) at all concentrations, i.e., 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/mL after 3 days of incubation (Figure 6) followed by fennel EO with reduced growth inhibition (67.2%, 74.0%, 76.2%, and 84.5%) in comparison to control in which none of the growth inhibition was observed. However, garlic EO was found least at all concentrations in the range of 30–60% during the third day of observation.

Effect of plant EOs at four concentrations (0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/mL) on growth inhibition of (a) Penicillium expansum and (b) Penicillium crustosum. Mean values in the columns separated by Tukey’s HSD test at P ≤ 0.05 followed by the same letters are not significantly different from each other; Control* (without application of plant EO).

3.3.1.2 Efficacy of plant EOs against Penicillium crustosum

Similar results were also achieved regarding thyme EO efficacy against Penicillium crustosum (Pen c 04), showing maximum inhibition of 82.1%, 87.5%, 92.4%, and 95.3% at four concentrations, i.e., 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/mL followed by fennel EO (70.9%, 75.8%, 83.6%, 90.3%), whereas garlic EO showed less inhibition effectiveness 45.2%, 50.3%, 53.2%, and 55.1% while none of the growth inhibition appeared under control conditions (Figure 6).

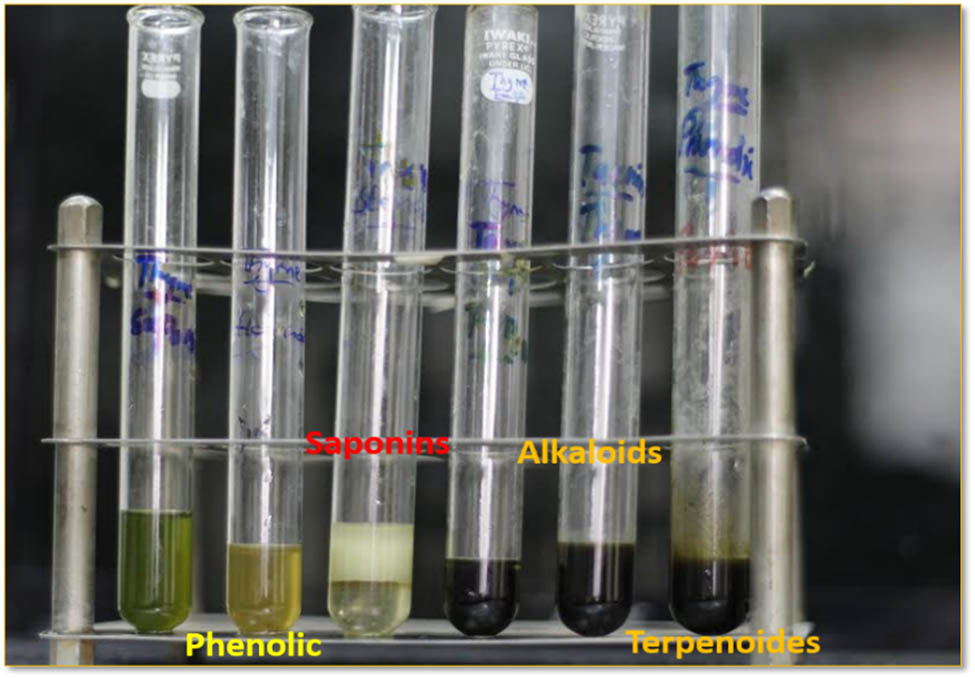

3.4 Qualitative phytochemical analysis of plant EOs

Results of qualitative phytochemical analysis showed that based on colour indication, thyme EO has all tested metabolites such as terpenes (dark blue), alkaloids (dark brownish to black), phenols (yellowish to green), and saponins (foam-like appearance) (Figure 7). Fennel and carum EOs have three anti-microbial compounds viz. alkaloids, terpenes, and phenolics. Ginger EO has two phenols and saponins, whereas garlic EO has one (phenolic) antimicrobial compound (Table 5).

Qualitative phytochemical analysis of plant EO containing anti-fungal compounds.

Detailed phytochemical analysis of plant EOs

| S. no. | Plant EOs | Phytochemical test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | Terpenoids | Phenolics | Saponins | ||

| Wagner reagent | Salkowski test | Ferric chloride | Foam test | ||

| 1 | Thyme EO | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | Carum | + | + | + | − |

| 3 | Ginger | − | − | + | + |

| 4 | Garlic | − | − | + | − |

| 5 | Fennel | + | + | + | − |

+: present; –: absent.

3.5 Comparative efficacy of the thyme EO with some prevalent synthetic fungicides

MIC of synthetic fungicides viz. benzimidazole, zinc dimethyldithiocarbamate, and phenyl mercuric acetate was found to be 7, 4, and 3 mg/mL against P. expansum, whereas 6.2, 4, and 2.8 mg/mL against P. crustosum which were higher than the most effective thyme oil at 1.5 mg/mL tested in this study (Table 6). Thus, this oil is more efficacious than the synthetic fungicides.

Comparative efficacy of the thyme EO with some prevalent synthetic fungicides, ± standard deviation calculated by number of readings = 6

| Penicillium expansum | Penicillium crustosum | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum inhibitory concentrations (mg/mL) | ||

| Fungicides | ||

| Benzimidazole | 7 ± 1.6 | 6.2 ± 1.32 |

| Zinc dimethyldithiocarbamate | 4 ± 0.6 | 4 ± 1.1 |

| Phenylmercuric acetate | 3 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| Plant EO | ||

| Thyme EO | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

3.6 Fungitoxic properties of the thyme EO

According to the results obtained, it was observed that thyme EO inhibited the mycelial growth of both Penicillium spp. The treatment sets containing 32 discs of the test fungi indicating the efficacy of the thyme oil to tolerate high inoculum density of test fungus are shown in Table 7. This is the potential of this oil to be exploited as botanical fumigant. It was found that thyme oil remained active for 20 months. The oils remained fungitoxic in nature at different temperatures between 10°C and 45°C, showing the thermostable nature of their fungitoxicity.

Effect of increased inoculum density on fungitoxicity of the thyme oil

| Penicillium expansum | Growth of P. expansum | Penicillium crustosum | Growth of P. crustosum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of fungal discs | Approx. number of spores | Treatment | Control | Approx. number of spores | Treatment | control |

| 2 | 1,564 × 103 | − | + | 1,590 × 103 | − | + |

| 4 | 3,128 × 103 | − | + | 3,180 × 103 | − | + |

| 8 | 6,256 × 103 | − | + | 6,360 × 103 | − | + |

| 16 | 12,502 × 103 | − | + | 12,720 × 103 | − | + |

| 32 | 25,004 × 103 | − | + | 25,440 × 103 | − | + |

(–) indicates no growth of test fungus, (+) indicates growth of test fungus.

3.7 Physicochemical properties of thyme EO

The yield of thyme oil was 0.6%. Furthermore, this EO was yellowish green in colour and pleasant in odour. The oil was found to be soluble in all the tested organic solvents. The specific gravity of thyme oil was found to be 0.92, and the phenolic content was also found in this oil during observations (Table 8).

Physiochemical properties of thyme EO

| Parameters | Thyme EOs |

|---|---|

| Colour | Yellowish green |

| Odour | Pleasant |

| Specific gravity | 0.92 |

| Optical rotation | (−) 16°C |

| Refractive index | 1.49 at 24°C |

| Solubility | |

| Acetone | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| Absolute alcohol | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| 90% alcohol | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| Ethyl acetate | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| Benzene | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| Chloroform | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| Hexane | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| Methanol | Soluble (1:1 conc.) |

| Phenolic content | Present |

3.8 Application of thyme oil on grapes against Penicillium spp.

3.8.1 Decay incidence percentage

Thyme EO coating was effective against Penicillium spp. at 1.5 mg/mL concentration. Results revealed that DIP of (thyme EO + Penicillium expansum inoculum)-treated bunches was 9.64% after the third day of storage at room temperature as compared to the control set (28.63%) in which only inoculum was applied. However, on the sixth day DIP was recorded to be 18.24% and ranked the second disease score in treatment (T1) (thyme EO + Penicillium expansum inoculum), whereas in the case of control (T0) DIP was 92.35% and ranked the fifth disease rating level (0–5 scale). Similar results found in the case of Penicillium crustosum revealed that DIP with application of 1.5 mg/mL of thyme EO on Perlette cultivar was calculated to be 8.1% after the third day in comparison with control which showed 26.23%. A 20.46% decay was recorded on Perlette bunches against Penicillium crustosum after the sixth day of storage as compared to 90.5% for control (Table 9).

Effect of thyme oil on DIP of Penicillium spp. after 3 and 6 days of storage

| Treatments | Storage days | DI* (%) | Decay rating scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium expansum | ||||

| T0 | Control* | 3 | 28.63b | 3 |

| 6 | 92.35d | 5 | ||

| T1 | Thyme oil 1.5 mg/mL + Penicillium expansum | 3 | 9.64a | 1 |

| 6 | 18.24c | 2 | ||

| Penicillium crustosum | ||||

| T0 | Control* | 3 | 26.23b | 3 |

| 6 | 90.5d | 5 | ||

| T1 | Thyme oil 1.5 mg/mL + Penicillium crustosum | 3 | 8.1a | 1 |

| 6 | 20.46c | 2 | ||

Decay rating scale: (0) no symptoms, (1) up to 10, (2) 11–25, (3) 26–40, (4) 40–60, and (5) above 60.

Control* (only Penicillium spp. as an inoculum applied) – DI* (decaying incidence) The mean values of decaying percentage of “Perlette variety” given in the columns are analysed by Tukey’s HSD test at P ≤ 0.05. The values are an average of three replicates. The data for statistical analysis included (two treatments, two-storage days, one concentration, and three replications).

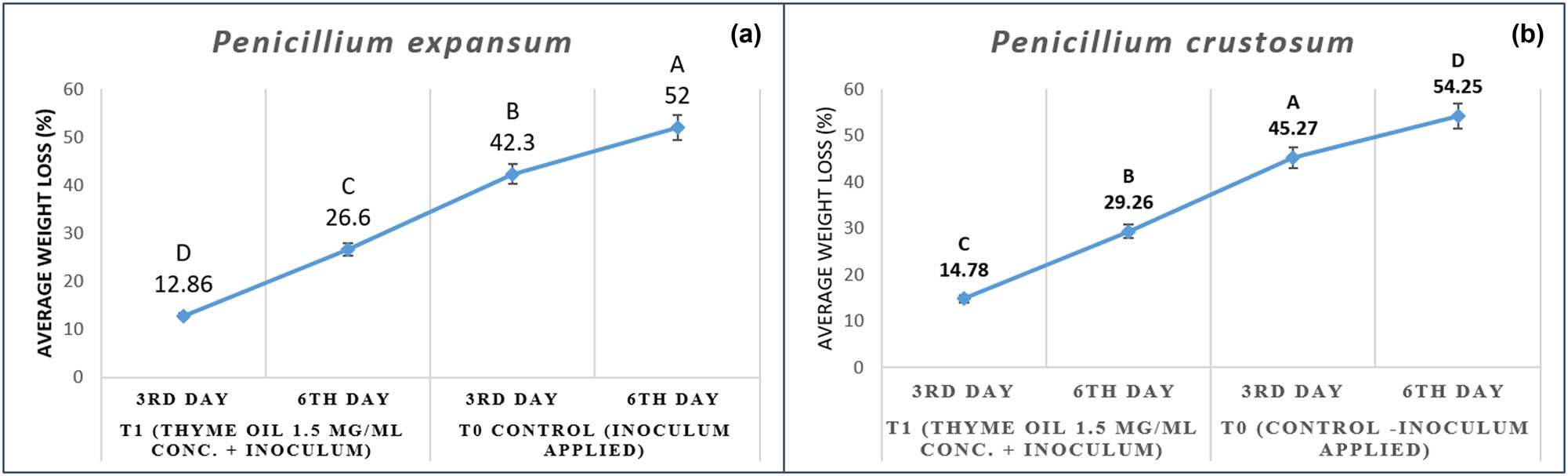

3.8.2 AW loss assessment

AW of 525 g Perlette bunches was calculated in an electrical balance before the application of thyme EO at 1.5 mg/mL concentration against Penicillium spp. (P. expansum isolate and P. crustosum). After the third day of application of treatment set T1 (thyme EO 1.5 mg/mL conc. + Penicillium spp. inoculum) on grape bunches, the minimum AW loss percentage was recorded as 12.8% and 14.7% against P. expansum and P. crustosum as compared to control (T0), and weight loss% increased up to 42.3% and 45.2% where only inoculums were applied. However, after the sixth day of storage AWL% of 26.6% and 29.2% was recorded in thyme oil treatment with inoculum (P. expansum and P. crustosum), whereas in control, this percentage increased to 52.4% and 54.2%, respectively (Figure 8).

(a and b) Average weight loss (AWL) assessment of thyme oil against Penicillium spp.

4 Discussion

In this study, morphological characteristics and multilocus phylogenetic analysis were used to identify 13 isolates on symptomatic fruit bunches located at five different locations of Rawalpindi district, Punjab province, Pakistan. The genus causing blue mold was classified into two distinct species viz. Penicillium expansum (eight strains, 61.4%) and Penicillium crustosum (five strains, 31.2%). Study revealed that the colony appearance of Penicillium expansum showed significant difference from Penicillium crustosum, which had dense white to bluish green sporulation lacking white margins, whereas colony colour of P. crustosum appeared white to greyish-green sporulation with white margins on PDA medium. Next, we examined other morphological characteristics such as conidiophore and conidia. The shapes of conidia were ellipsoidal, subglobose, and spherical but varied in size. In addition, the shape of conidiophore varied in both species, mono-verticillate type of conidiophore was observed in P. expansum isolates while conidiophore having tetra-verticillate shape was found in P. crustosum. These are consistent with the results of Hema and Prakasam (2013) who observed that P. expansum and P. crustosum appeared in different colony colours, i.e. bluish to green varying from species to species [29]. A similar study was also conducted by Pitt (2009) regarding morphological characteristics of Penicillium spp. having mono-verticillate conidiophore in P. expansum while tetra-verticillate conidiophore observed in P. crustosum [30]. Taken together, our results suggested that the morphological characteristics of P. expansum were different from P. crustosum to some extent, but still not accurate enough to classify the species within a species complex. Therefore, morphological characteristics and phylogenetic analysis were carried out to identify Penicillium species in this study. Phylogenetic analysis divided 13 isolates into P. expansum and P. crustosum, respectively. Capote et al. (2012) revealed that DNA analysis has become the most critical and precise method to characterize the fungal species and sketching the phylogenetic relationship between them [31]. The ITS region of DNA has been widely applied in phylogenetic studies of fungi due to highly conserved and can be easily investigated using PCR amplification [32]. However, the ITS sequence information alone cannot be used to place a fungus at the species level. In this study, we use the ITS with combination of β-tubulin and calmodulin an effective marker for species identification by following the research work which identified the other fungal genera such as Alternaria [33], Aspergillus [34], and Botrytis [35] by using the same marker genes. In future work with Penicillium species identification and genome sequencing, we are developing other more effective markers, with an emphasis on distinguishing the blue molds that cause postharvest decay. In our pathogenicity tests, both Penicillium species are pathogenic to grape bunches, suggesting that Penicillium spp. can be a huge potential threat to the viticulture industry in Pakistan during storage conditions. Therefore, this study is valuable for guiding the prevention and management of blue mold of grapes. Identification of Penicillium species and their pathogenicity on grapes help us to elucidate the relationship between Penicillium population and grape bunches in Pakistan. This research provided us a useful information for the control of blue mold and promote a sustainable and healthy development of Pakistan’s viticulture industry.

For the management of postharvest pathogens, previous studies illustrated that frequent use of chemical fungicides is the primary means of controlling the postharvest pathogens but have some limitations due to fungicidal resistance among fungal population and high development cost of these synthetic chemicals. Therefore, researchers have successfully introduced green revolution in the form of botanicals as the replacement of synthetic fungicides because of non-toxic residual effect, eco-friendly green synthesis, and public acceptance [36]. In this study, we examined the antimicrobial activities of thyme, fennel, carum, ginger, and garlic EOs against highly pathogenic isolates of Penicillium spp. viz. P. expansum and P. crustosum causing blue mold disease and found that thyme EO had considerable effect on the growth rate of tested fungus both under in vitro conditions and application on grape bunches. The results of this study confirmed a strong inhibitory potential of thyme EO against Penicillium spp. Thymus vulgaris is an effective fungitoxic agent previously studied by several scientists against fungal pathogens [37]. The mechanism of thyme EOs involved inhibition of hyphal growth, interruption in nutrient uptake, disruption of mitochondrial structure, and eventually disorganization of fungal pathogens [38]. Similarly, Pina et al. (2004) found that thymol is the major active component in thyme EO and has a fungicidal activity, resulting mainly in cell lysis and extensive damage to the cell wall and the cell membrane of postharvest fungal pathogens [39]. In the past, researchers Teixeira et al. (2013) have studied various chemical compounds present in the aerial part of Thymus vulgaris such as thymol 46.6%, linalool 3.8%, cymene 38.9%, camphene 1%, α-pinene 3.3%, and β-pinene 1.2%, which showed fungal toxicity against postharvest fungal pathogens [40]. Cakir et al. (2005) reported that phenols, terpenes, and alkaloids are biologically active compounds in thyme oil having anti-fungal properties to control the postharvest decay of fruits [41]. The present study investigated that on comparing the MIC of thyme oil with some synthetic fungicides, the oil was found more active with less concentration and thermostable in nature which is in agreement with the findings of Tripathi and Dubey (2004) concluded that antifungal potency of O. sanctum (200 ppm), P. persica (100 ppm), and Z. officinale (100 ppm) was found to be greater in comparison to some prevalent synthetic fungicides viz. benomyl (3,000 ppm), Ceresan (1,000 ppm), and Ziram (5,000 ppm), respectively [42]. Antunes and Cavaco (2010) explained some mechanism actions of thyme EO during the application on fruits against microbes such as those responsible to alter microbial cell permeability, strengthen the berries’ skin surface, disrupt the mycelial growth, and prevent the decay of fruits, respectively [43]. Previously other researchers such as Lopez et al. (2010) also checked the effect of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) oil on four cultivars of apples against Penicillium digitatum for the determination of DIP and found that thyme oil at 0.1% concentration showed maximum efficacy as compared to fennel and lavender EOs [44]. Our result is in agreement with the results of Shamloo et al. (2013) who stated that application of thyme EO on sweet cherries during the storage period acts as a physical barrier against moisture loss from fruit skin, prevent weight loss and fruit shrinkage, decrease respiration rate of fruits, and delay senescence [45].

5 Conclusions

This research provided a comprehensive factual picture of blue mold disease of grapes from Pakistan through proper morphomolecular identification of associated Penicillium spp. In conclusion, thyme oil with strong fungitoxicity, thermostable nature, long shelf life, fungicidal nature against the test fungus, lower MIC in comparison to synthetic fungicides and the efficacy to withstand high inoculum density has all the desired characteristics of an ideal fungicide. Meanwhile, could also be recommended as a botanical fungitoxicant. These natural compounds are highly degradable with no bioaccumulation in plant, can be effective against postharvest pathogens, and can be further exploited to replace hazardous environment deteriorating artificial fungicides. The results of this study can be served as a guide for the selection of EOs and their concentrations for further in vivo trials aimed at fungicide development.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their gratitude to Professor Dr. Mark L. Gleason, Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, Iowa State University (ISU) for his continued support, encouragement, and guidance during molecular identification of Penicillium spp. in ISU, USA.

-

Research funding: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Salman Ghuffar and Gulshan Irshad: methodology, data curation, writing – original draft; Muhammad Azam Khan and Farah Naz: writing – review and editing. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] GOP. Fruits, vegetables and condiments statistics of Pakistan. Government of Pakistan Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Livestock [Preprint]; 2019. [cited 2020 Sep 3]. Available from: http://www.mnfsr.gov.pk/pubDetails.aspxSuche in Google Scholar

[2] Ali KF, Maltese YH, Choi VR. Metabolic constituents of grapevine and grape-derived products. Phytochem Rev. 2010;9:357–78.10.1007/s11101-009-9158-0Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Palou LS, Smilanick JL, Crisosto CH, Mansour M, Plaza P. Ozone gas penetration and control of the sporulation of Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium italicum within commercial packages of oranges during cold storage. Crop Prot. 2003;22:1131–4.10.1016/S0261-2194(03)00145-5Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Visagie C, Houbraken J, Frisvad JC, Hong SB, Klaassen C, Perrone G, et al. Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium. Stud Mycol. 2014;78:343–71.10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Tiwari K, Jadhav S, Kumar A. Morphological and molecular study of different Penicillium species. Middle East J Sci Res. 2011;7:203–10.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Seifert KA, Samson RA, Houbraken J, Lévesque CA, Moncalvo JM, Louis Seize G, et al. Prospects for fungus identification using CO1 DNA barcodes, with Penicillium as a test case. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3901–6.10.1073/pnas.0611691104Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Seifert K, Louis Seize G. Phylogeny and species concepts in the Penicillium aurantiogriseum complex as inferred from partial beta tubulin gene DNA sequences. Integration of modern taxonomic methods for Penicillium and aspergillus classification. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2000. p. 189–98.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Houbraken J, Visagie CM, Meijer M, Frisvad JC, Busby PE, Pitt JI, et al. A taxonomic and phylogenetic revision of Penicillium section aspergilloides. Stud Mycol. 2014;78:373–451.10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Reimann S, Deising H. Fungicides: risks of resistance development and search for new targets. Arch Phytopathol Plant Prot. 2000;33:329–49.10.1080/03235400009383354Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Miller G. Sustaining the earth (vol 9). Pacific Grove, CA: Thompson Learning, Inc.; 2004. p. 211–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Diaz JA, Griffith RA, Reinert SE, Friedmann PD, Moulton AW. Patients’ use of the Internet for medical information. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:180–5.10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10603.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Mar RJ, Hassani A, Ghosta Y, Abdollahi A, Pirzad A, Sefidkon F. Control of Penicillium expansum and Botrytis cinerea on pear with Thymus kotschyanus, Ocimum basilicum and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils. J Med Plant Res. 2011;5:626–34.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Tas L, Karaca G. Effects of some essential oils on mycelial growth of Penicillium expansum link and blue mold severity on apple. Asian J Agric Food Sci. 2015;3:643–50.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Pitt JI. The genus Penicillium and its teleomorphic states eupenicillium and talaromyces. Mycologia. 1979;73:582–4.10.2307/3759616Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Gimeno A, Martins ML. Rapid thin layer chromatographic determination of patulin, citrinin, and aflatoxin in apples and pears, and their juices and jams. J Assoc Anal Chem. 1983;66:85–91.10.1093/jaoac/66.1.85Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Frisvad JC, Filtenborg O, Thrane U. Analysis and screening for mycotoxins and other secondary metabolites in fungal cultures by thin-layer chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography. Arch Env Contam Toxicol. 1989;18:331–5.10.1007/BF01062357Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Javed S, Javaid A, Anwar W, Majeed R, Akhtar R, Naqvi S. First report of botrytis bunch rot of grapes caused by Botrytis cinerea in Pakistan. Plant Dis. 2017;101:1036.10.1094/PDIS-05-16-0762-PDNSuche in Google Scholar

[18] Senthil R, Prabakar K, Rajendran L, Karthikeyan G. Efficacy of different biological control agents against major postharvest pathogens of grapes under room temperature storage conditions. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2011;50:55–65.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The Clustal-X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–82.10.1093/nar/25.24.4876Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.10.1093/molbev/msw054Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Sahin F, Karaman I, Gulluce M, Ogutcu H, Sengul M, Adıguzel A, et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial activities of Satureja hortensis L. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;87:61–5.10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00110-7Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Dauria F, Tecca M, Strippoli V, Salvatore G, Battinelli L, Mazzanti G. Antifungal activity of Lavandula angustifolia essential oil against Candida albicans yeast and mycelial form. Med Mycol. 2005;43:391–6.10.1080/13693780400004810Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Evans WC. Trease and evans phamacognosy. 14th ed. Singapore: Harcourt Brace and Company, Asia Pvt Ltd Singapore; 1997. p. 343.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Kokate CK. Practical pharmacognasy. 4th ed. New Dehli, India: Vallabh Parkashan Publications; 1999. p. 115.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Molyar V, Pattisapu N. Detoxification of essential oil components (Citral and menthol) by Aspergillus niger and Rhizopus stolonifer. J Sci Food Agric. 1987;39:239–46.10.1002/jsfa.2740390307Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Shahi SK, Shukla AC, Bajaj AK, Dikshit A. Broad spectrum antimycotic drug for the control of fungal infection in human beings. Curr Sci. 1999;76:836–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Chowdhury AR, Kapoor VP. Essential oil from fruit of Apium graveolens. J Med Aromat Plant Sci. 2000;22:621–3.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Asghari M, Khalili H, Rasmi Y, Mohammadzadeh A. Influence of postharvest nitric oxide and Aloe vera gel application on sweet cherry quality indices and storage life. Int J Plant Prod. 2013;4:2393–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Hema MT, Prakasam V. First report of Penicillium expansum causing bulb rot of lilium in India. Am Eurasian J Agric Env Sci. 2013;13:293–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Pitt JI, Hocking AD. Fungi and food spoilage (vol. 519). Heidelberg: Springer; 2009.10.1007/978-0-387-92207-2Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Capote N, Pastrana AM, Aguado A, Sánchez, Torres P. Molecular tools for detection of plant pathogenic fungi and fungicide resistance. Plant Pathol. 2012;5:151–202.10.5772/38011Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Gardes M, Bruns TD. Its primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes-application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol Ecol. 1993;2:113–8.10.1111/j.1365-294X.1993.tb00005.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Woudenberg J, Seidl M, Groenewald J, De VM, Stielow J, Thomma B, et al. Alternaria section Alternaria: species, formae speciales or pathotypes stud. Mycol. 2015;82:1–21.10.1016/j.simyco.2015.07.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Lee S, An C, Xu S, Lee S, Yamamoto N. High-throughput sequencing reveals unprecedented diversities of Aspergillus species in outdoor air. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2016;63:165–71.10.1111/lam.12608Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Diepeningen AD, Feng P, Ahmed S, Sudhadham M, Bunyaratavej S, Hoog GS. Spectrum of Fusarium infections in tropical dermatology evidenced by multilocus sequencing typing diagnostics. Mycoses. 2015;58:48–57.10.1111/myc.12273Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Seema MSS, Sreenivas ND, Devaki NS. In vitro studies of some plant extracts against Rhizoctonia solani Kuhn infecting FCV tobacco in Karnataka light soil, Karnataka. India J Agric Sci Technol. 2011;7:1321–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Siripornvisa S, Gamchawee KN. Utilization of herbal essential oils as biofumigant against fungal decay of tomato during storage. Proceedings 16th Asian agricultural symposium, Bangkok: Thailand; 2010. p. 655–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Patel RM, Jasrai YT. Evaluation of fungitoxic potency of medicinal plants volatile oils against plant pathogenic fungi. Pestic Res J. 2011;23:168–71.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Pina VC, Goncalves RA, Pinto E, Costa DOS, Tavares C, Salgueiro L, et al. Antifungal activity of thymus oils and their major compounds. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2004;18(1):73–8.10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00886.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Teixeira B, Marques A, Ramos C, Neng NR, Nogueira JM, Saraiva JA, et al. Chemical composition and antibacterial and antioxidant properties of commercial essential oils. Ind Crop Prod. 2013;43:587–95.10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.07.069Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Cakir A, Kordali S, Kilic H, Kaya E. Antifungal properties of essential oil and crude extracts of hypericum linarioides Bosse. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2005;33:245–56.10.1016/j.bse.2004.08.006Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Tripathi P, Dubey N. Exploitation of natural products as an alternative strategy to control postharvest fungal rotting of fruit and vegetables. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2004;32:235–45.10.1016/j.postharvbio.2003.11.005Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Antunes MDC, Cavaco AM. The use of essential oils for postharvest decay control. A review. Flavour Frag J. 2010;25:351–66.10.1002/ffj.1986Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Lopez RJG, Spadaro D, Gullino ML, Garibaldi A. Efficacy of plant essential oils on postharvest control of rot caused by fungi on four cultivars of apples in vivo. Flavour Frag J. 2010;25:171–7.10.1002/ffj.1989Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Shamloo M, Sharifani M, Garmakhany AD, Seifi E. Alternation of flavonoid compounds in valencia orange fruit (Citrus sinensis) peel as a function of storage period and edible covers. Minerva Biotecnol. 2013;25:191–7.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Salman Ghuffar et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis