Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

-

Nilofar Mustafa

, Naveed Iqbal Raja

, Zia-ur-Rehman Mashwani

Abstract

The present study was carried out to investigate the beneficial and toxicological effect of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) on the morphophysiological attributes of wheat plants under salinity stress. The biogenesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles was accomplished by using the extract of Buddleja asiatica L. leaves followed by characterization through UV visible spectroscopy, SEM, FTIR, and EDX. NaCl salt was applied in two different concentrations after 21 days of germination followed by foliar applications of various concentrations of TiO2 NPs (20, 40, 60, 80 mg/L) to salinity-tolerant (Faisalabad-08) and salinity-susceptible (NARC-11) wheat varieties after 10–15 days of application of salt stress. Salinity stress showed remarkable decrease in morphophysiological attributes of selected wheat varieties. Magnificent improvement in plant height, dry and fresh weight of plants, shoot and root length, root and shoot fresh and dry weight, number of leaves per plant, RWC, MSI, chlorophyll a and b, and total chlorophyll contents has been observed when 40 mg/L of TiO2 NPs was used. However, the plant morphophysiological parameters decreased gradually at higher concentrations (60 and 80 mg/L) in both selected wheat varieties. Therefore, 40 mg/L concentration of TiO2 NPs was found most preferable to increase the growth agronomic and physiological attributes of selected wheat varieties under salinity.

Abbreviations

- TiO2

-

titanium dioxide

- NPs

-

nanoparticles

- SEM

-

scanning electron microscopy

- FTIR

-

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- EDX

-

energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- RWC

-

relative water content

- MSI

-

membrane stability index

- EC

-

electrical conductivity

1 Introduction

Quality agriculture implementations of an area improve mass production, reduce inflation, reduce food scarcity, and boost up the livelihood of all associated people particularly farmers. Weak agronomic practices such as selection of poor-quality crop varieties, unhealthy seeds, utilizing poor-quality fertilizers, weed killers, insecticides, and extreme surrounding situations significantly decrease the crops’ yield and production [1]. Wheat crop is considered as a vital source of carbohydrates worldwide and is categorized as the 3rd most dominant food providing crop after rice and corn. Wheat and its by-products are consumed globally, including, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, and India [2]. As a globally important food crop, wheat has the potential to contribute to overcoming food security challenges in many countries of the world. Keeping in view these food security concerns, wheat is considered among the extraordinarily concerned research crops. Various environmental problems such as salinity, drought, water logging, and low and high temperature impose detrimental consequences on production and quality of wheat crop. Among these, excessive salinity stress is an extremely important abiotic factor negatively affecting the developmental processes, physiological attributes, and biochemical profiling of wheat crop thus resulting in low yield [3]. Furthermore, salinity is regarded as a primary source to affect the grain quality and yield of crop which brings about agglomeration of life-threatening heavy metals into plants body, making them unsuitable for the human being and animals and causing severe health disorders. Additionally, soil salinity has devastating effects on morphophysiological and biochemical pathways of various crops [4]. Overaccumulation of salts consequently leads to create imbalance in plants’ cellular homeostasis, oxidative stress, retard growth, and nutrient deficiency, ultimately causing cell death. Furthermore, in previous studies it is reported that excess level of salinization adversely affects the plants’ cellular functioning, instability of membrane, and create hindrance in enzymatic activities [5]. The excessive accumulation of salts decreases uptake of vital nutrients (Fe, K, Ca, and P), thereby plants suffer greatly from membrane damage, nutritional imbalance, enzymatic inhibition, and low crop yield [6]. Additionally, extreme salinity-induced oxidative stress results in overproduction of reactive oxygen species which damages the essential proteins, nucleic acids, membrane lipids, and photosynthetic pigments [7,8].

To mitigate the deteriorated effects of abiotic and biotic stresses in wheat plants, various techniques including quantitative trait locus mapping, genetic engineering, selection based on molecular markers, and cross breeding practices are commonly in use [9]. These modern approaches are having some drawbacks that involve technical expertise and operation procedures which are expensive. The present situation demands a rational, feasible, and convenient approach having the capability to surpass these inadequacies. Nanotechnology has attained prominent position among these technological innovations, because of its wide spectrum implementations in the maintenance of agricultural ecosystem [10]. Furthermore, nano-biotechnology has attracted notable attention of nanotechnologists in agriculture because of excellent biocompatibility, high rate of penetration, and absorption of nanoparticles in the plants [3]. Moreover, extra small size structure and surface characteristics of nanoparticles (NPs) result in unique physicochemical properties [11]. Surprisingly, the foliar applications of nanoparticles are among the novel approach to ameliorate developmental processes of plants under salinity stress.

In this scenario, plants-mediated titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) have gained considerable attention because of their excellent biocompatibility, less toxicity, strong ability to scavenge the free radicals, and high bioavailability. It is anticipated that titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) lead to numerous significant consequences on biochemical and morphophysiological attributes of some plants [12]. It is also reported that titanium dioxide nanoparticles’ applications significantly improved the photosynthetic rate, activity of rubisco and antioxidant enzymes potential, and chlorophyll formation that significantly enhance crop yield [13]. However, another study reported positive influence of nano-TiO2 on plants growth, soluble sugars, antioxidative defense system, and proline contents in addition to a reduction in hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde contents in broad bean plants under salinity stress [14]. Furthermore, another study revealed the mitigation of salinity stress in tomato crop through exogenous applications of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by improving the antioxidant capacity, agronomic parameters, phenolics, chlorophyll contents, and yield [15]. However, unfortunately high dose of titanium dioxide nanoparticles induces release of reactive oxygen species at higher rate consequently declining chlorophyll contents, and toxicity at cell level. However, there is little data available on beneficial and toxicological role of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles on different wheat varieties under salinity stress. Thus, the current study was aimed to explore the beneficial and toxicological effects of various concentrations of plants-mediated nano-TiO2 on agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat plants.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of Buddleja asiatica leaves extract

TiO2 bulk material was purchased from Merk (Germany). Fresh and healthy leaves of Buddleja asiatica L. were collected from mother plant present in district Bagh Azad Kashmir. Leaves were collected and washed thoroughly with tap water consequently by distilled water to get rid of dirt and other impurities. Leaves were shade-dried and cut into small pieces followed by weighing of 30 g of leaves and then boiling in 250 mL distilled water ti1l color changes take place to light brown. The decoction was then filtered three times using Whattman no. 1 filter paper to get clear solution without any other particles, then it was refrigerated (4°C) in 300 mL media bottle to use further. Sterile conditions were maintained to avoid contamination and get effective and accurate results [1,16].

2.2 Biosynthesis of TiO2 utilizing Buddleja asiatica L. aqueous leaves extract

TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized using the method of ref. [17] with slight modifications. To prepare 3.5 mM TiO2 solutions, 0.27 g of TiO2 salt was dissolved in 1,000 mL of distilled water. Salt solution was transferred to 250 mL conical flasks followed by constant shaking for 2 h at 100 rpm on orbital shaker. 80 mL of salt solution was then transferred to 100 mL beaker and 20 mL plant extract was added gradually under continuous stirring condition. No color change was observed. Solution was kept on stirrer for 24 h. Color changes indicate the formation of TiO2 nanoparticles. After that, solution was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min and supernatant was thrown away. Pellet was washed with distilled water again by centrifugation. Pellet was then collected and used for other processes.

2.3 Characterization of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles

The characterization of plant-based titanium dioxide was done through different characterization techniques, i.e., ultraviolet visible (UV) spectrophotometer, FTIR, SEM, and EDX. The UV visible spectroscopy was done by using Systronics Halo DB-20, Dynamica Scientific Ltd to verify the preparation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by analyzing the wavelength of TiO2 NPs solution, keeping the range between 180 and 600 nm of the light wavelength. FTIR analysis is carried out between the range of 350 and 4,500 cm−1 by using Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer with a resolution of 0.15 cm−1 to recognize the functional groups that are accountable for stabilizing TiO2. Morphology of biosynthesized TiO2 NPs was examined by using SEM (SIGMA model, Zeiss, Germany) at 15 kV. SEM was done by preparing sample on copper grid followed by drying of sample in vacuum chamber before placing it in SEM holder. EDX XL-30 was used at 15–25 keV to perform EDX.

2.4 Collection of seeds, growth conditions, and locality description

Vigorous seeds of wheat varieties, viz., Faisalabad-09 (salt tolerant) and NARC-11(Salt-susceptible), were collected from NARC (National Agriculture Research Council, Islamabad). Ten percent of Sodium Hypochlorite solution was used for the sterilization of seeds [18]. Experiment was performed at glass house of Department of Botany Pir Mehar Ali Shah, University of Arid Agriculture Rawalpindi, in growing season of wheat crop from Nov 2018 to Feb 2019. Wheat was sown in particular pots of 24 cm width and 19 cm length, packed with soil (4.5 kg sandy loam) having sand 43.1%, silt 5.3%, and clay 51.6%; 6–8 seeds were planted in all pots. Analysis of soil for EC, PH, organic matter available phosphorous, potassium, and saturation was done. No fertilizers were used throughout experiment.

2.5 Experimental design and application of treatment

Both wheat varieties were organized into ten major groups as shown in Table 1, according to treatments as control (irrigation), salinity stress (100 mM NaCl) without NPs, salinity stress (150 mM NaCl) without NPs, salinity stress (100 mM NaCl) with exogenous application of 20 mg/L TiO2 NPs, salinity stress 150 mM NaCl with exogenous application of 20 mg/L TiO2, salinity stress (100 mM NaCl) with foliar application of 40 mg/L TiO2, salinity stress (150 mM NaCl) with exogenous application of 40 mg/L TiO2, salinity stress (100 mM NaCl) with exogenous application of 60 mg/L TiO2, salinity stress (150 mM NaCl) with exogenous application of 60 mg/L TiO2, salinity stress (100 mM NaCl) with exogenous application of 80 mg/L TiO2, and salinity stress (100 mM NaCl) with exogenous application of 80 mg/L TiO2. After 21 days of germination, two different concentrations (100 and 150 mM) of NaCl salt were applied till the end of experiment. Application of salt solution was repeated every third day. After every three treatments, water was applied for one time. After 10–15 days of application of salt stress, exogenous application of TiO2 nanoparticles of different concentrations was applied.

Different treatments on wheat varieties under salinity stress

| SR. no. | Treatment code | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | T0 | Control irrigation + 0 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 2 | T1 | Control irrigation + 20 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 3 | T2 | Control irrigation + 40 mg/Lof TiO2 NPs |

| 4 | T3 | Control irrigation + 60 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 5 | T4 | Control irrigation + 80 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 6 | T5 | Salinity stress (100 mM) + 0 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 7 | T6 | Salinity stress (150 mM) + 0 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 8 | T7 | Salinity stress (100 mM) + 20 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 9 | T8 | Salinity stress (150 mM) + 20 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 10 | T9 | Salinity stress (100 mM) + 40 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 11 | T10 | Salinity stress (150 mM) + 40 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 12 | T11 | Salinity stress (100 mM) + 60 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 13 | T12 | Salinity stress (150 mM) + 60 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 14 | T13 | Salinity stress (100 mM) + 80 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

| 15 | T14 | Salinity stress (150 mM) + 80 mg/L of TiO2 NPs |

2.6 Collection of data for morphophysiological parameters

During the experiment, PH and EC of soil were measured regularly. After 90–95 days, different agronomic attributes were analyzed through random sampling method. The agronomic parameters include the root and shoot length, height of plant, shoot and root dry and fresh weight, plant dry and fresh weight, and leaf numbers per plant. Physiological parameters include total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a and b, MSI, and RWC. Three plants were uprooted from each treatment.

2.7 Analysis of agronomic and physiological parameters

Three plants from each treatment were uprooted for analyzing plant length. The length of wheat plants was measured in centimeter through scale. To measure plant dry and fresh weight, 3–4 plants were uprooted and washed thoroughly, then fresh weight of each plant was measured separately and placed in dry oven at 65°C for 12 h. Three plants from each wheat varieties were collected and thoroughly washed with tap water followed by distilled water to count the number of leaves per plant.

2.8 Relative water contents

A flag leaf was taken from plant and its fresh weight was measured. Then the leaf was soaked in water for 24 h. After this, the leaves’ turgid weight was recorded. Then these leaves of each sample were placed in oven at 70°C for one week and after one week the dry weight was measured [19]. To find out relative water contents of leaves, following equation was used:

2.9 Membrane stability index (MSI)

To measure MSI, the method proposed in ref. [20] was applied. Leaf samples were taken and cut into tiny discs of 100 mg and subsequently cleaned carefully with deionized water. After washing, discs were placed in test tubes and kept in water bath at 40°C for 30 min. After this, EC meter was used to measure (C 1) electric conductivity. Then samples were kept again in water bath at 100°C for 10 min to measure electric conductivity (C 2). After taking these readings, MSI was calculated using given equation:

2.10 Leaf chlorophyll contents

Leaf chlorophyll contents were measured by using spectrophotometer following the process of ref. [21]. 0.2 g of leaves were grinded in acetone (10 mL). After complete grinding, filtrate was obtained in another set of test tubes and absorbance was observed at 645, 652, and 663 nm wavelength. Following equations were used to calculate chlorophyll contents [22,23,24,25,26]:

2.11 Comparative analysis

Analysis of variance (two-way) was used for measuring the difference between treatments and varieties via software statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS). Significant differences in resulting data were recognized at P < 0.05 level by using Duncan multiple range test.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphological and optical characterization of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles were prepared through an environmentally friendly technique by using Buddleja asiatica leaves’ liquid extract which is proved as an efficient extract for reduction of titanium dioxide anatase salt to nanoparticles. The decoction of Buddleja asiatica L. was added gradually in TiO2 solution while stirring, which results in pinkish brown color from off white after 24 h of stirring. Visual observation of color change is in-lined with results presented in ref. [27].

3.2 Spectrophotometric analysis of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles

The observed change in color of TiO2 solution was contemplated as an affirmation of the reduction of TiO2 salt into TiO2 NPs. The color change in the respective solution is the response of interaction TiO2 NPs using the wavelength of the light which is quantified in the SPR band through spectrometry. The spectral analysis was done between the range of 250–600 nm of light wavelength. The particular peaks were obtained between 390 and 400 nm (Figure 1a). The peak at 397 nm showed the formation of TiO2 NPs. Our results are in-lined with results of ref. [28] where similar results were reported.

Results of (a) ultraviolet visible spectroscopy and (b) scanning electron microscopy of titanium dioxide nanoparticles.

3.3 SEM analysis of TiO2 nanoparticles

The SEM analysis of nano-TiO2 showed that they are spherical in shape. Some of the TiO2 nanoparticles are fused and form tiny aggregations. Most of the nano-forms are found in the size ranging from 30 to 111 nm (Figure 1b). Our findings are similar with findings of ref. [27].

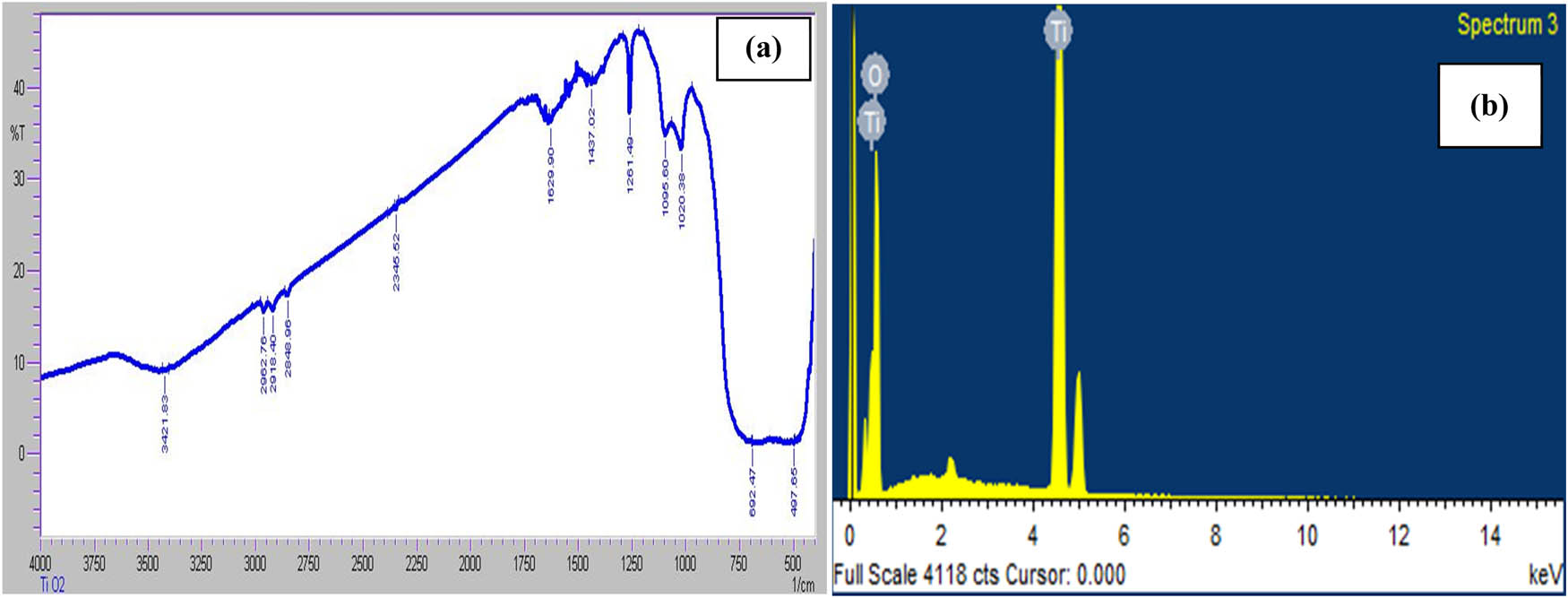

3.4 EDX spectroscopic analysis of TiO2 NPs

EDX provides the quantitative and qualitative details of the chemical elements that are possibly involve toward TiO2 NPs formation. Strong signals of atomic Ti and O at 4.4 and 1.0 showed the presence of TiO2 NPs, while the intensity of Ti is 44.93 and O 55.07% (Figure 2b).

Results of (a) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and (b) elemental dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.

3.5 FTIR spectroscopic analysis of TiO2 NPs

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was performed to find out the existence of prospective phytochemical groups that were accountable for preparation and constancy of TiO2 NPs. Figure 2a indicates the formation of crest at 3,200–3,200 cm−1 of wave number that showed the existence of O–H and N–H groups. Peaks between 2962.76, 2916.40, and 2848.90 showed the presence of C–H bonds and peaks at 2345.62 indicate the presence of carbonyl group. However, peaks at 1,639, 1,437, 1,261, 1,095, and 1,020 represent the presence of alkyl ketone, alkyl amines, carbonyl, and alkanes groups, respectively. Peaks in the region of 500 and 600 may be because of the halfway deteriation of amine or carboxyl group. Our findings of FTIR indicate that carbonyl and alkyl groups of Buddleja asiatica leaves extract may be responsible for reducing and stabilizing agents of TiO2 NPs (Figure 2b). Our results are in accordance with ref. [29] who reported C═C, C═O, and O–H groups as reducing and capping agents of TiO2 NPs.

3.6 Soil analysis

EC (1.03 dS/m), PH (7.64), organic matter (0.60%), available phosphorous (2.8 mg/kg), available potassium (86 mg/kg), and saturation (33%) of soil were analyzed before sowing. EC and PH of soil after salt application were also recorded.

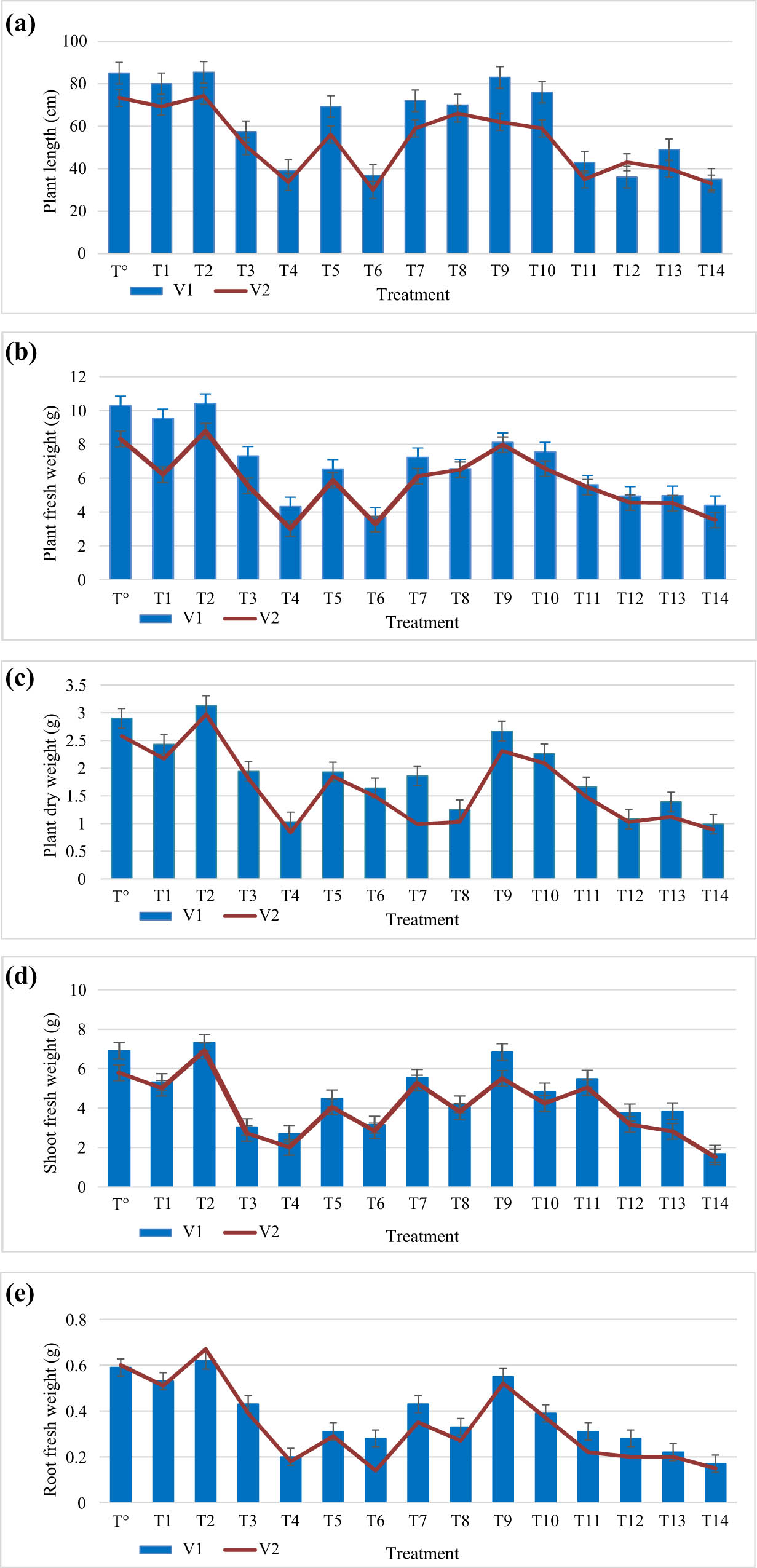

3.7 Effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on agronomic attributes of selected wheat varieties

In present study, different concentrations of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles were applied on two wheat varieties under salinity and control conditions. Effect of TiO2 NPs on the morphophysiological attributes of wheat varieties has been evaluated and characterized as length of shoot and root, plant height, roots, shoot and dry and fresh weight of plants, number of leaves per plant and total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a, b, RWC, and MSI. Application of 100 mM showed significant reduction in plant length (15.8%, 28.5%), plant fresh weight (13.2%, 21.4%), plant dry weight (14.8%, 20.7%), fresh weight of shoots (13.5%, 10.7%), dry weight of shoots (13.9%, 18.5%), fresh weight of roots (9.5%, 12.7%), dry weight of roots (15.5% and 21.2%), shoot length (14.2%, 12.1%), root length (14.7%, 13.1%), and leaves’ number per plant (3.5% and 6.9%) in both wheat varieties, respectively. However, 150 mM NaCl application reduces plant length (49.8%, 55.1%), plant fresh weight (25.5%, 30.9%), plant dry weight (22.4%, 29.5%), shoot fresh weight (23.5%, 30.7%), shoot dry weight (23.9%, 28.5%), root fresh weight (29.5%, 22.7%), root dry weight (17.5%, 22.2%), shoot length (44.3%, 54.1%) and root length (40.2%, 47.5%), and number of leaves (11.7%, 19.2%) in both wheat varieties, respectively. Our outcomes agree with results presented in ref. [30]. The saline conditions are imperative abiotic factor which can alter the plant physiological parameters that effect the plant morphology and have devastating effects on developmental growth of wheat plants [31,32,27,33].

However, application of plant-based TiO2 nanoparticles under salt stress conditions enhances growth of different parameters of wheat varieties. Plant-mediated titanium dioxide nanoparticles at 40 mg/L showed remarkable increase in plant length (11.2%, 10.5%), plant fresh weight (20%, 17%), plant dry weight (13%, 6%), plant shoot and root fresh weight (19.7%, 22.3%, and 15.5%, 19.9%, respectively), shoot and root dry weight (12.5%, 7.2% and 13.7%, 5.9%, respectively), shoot and root length (12.5%, 9.8% and 15.3%, 11.5%), and leaf number (10% and 40%) under 100 mM salt stress in both wheat varieties, respectively. Biogenic titanium dioxide nanoparticles at 40 mg/L showed significant increase in plant length (17.9% and 13%), plant fresh weight (22%, 19.4%), plant dry weight (6%, 30%), shoot and root fresh weight (13.7%, 12.3% and 10.5%, 9.9%, respectively), shoot and root dry weight (10.5%, 7.7% and 11.7%, 6.9%, respectively), shoot and root length (10.5%, 8.8% and 14.3%, 10.5%), and leaf number (30%, 20%) at 150 mM in both wheat varieties, respectively. In addition, considerable increase in plant length (5%, 7.7%), fresh weight plant (6.8%, 9%), dry weight of plant (11%, 7.2%), shoot and root fresh weight (10.3%, 12.2% and 9.7%, 10.2%, respectively), shoot and root dry weight (13.5%, 6.8% and 10.9%, 5.9%, respectively), shoot and root length (10.5%, 7.5% and 9.3%, 6.5%), and leaf number (9.5% and 13%), respectively, as compared to control. In present study, plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles are seemed to improve agronomic parameters of wheat varieties under salinity stress. Unfortunately, there is little work present on application of TiO2 nanoparticles on crop plants under stress conditions. In previous literature, AgNps are reported to ameliorate growth, dry and fresh weight of fenugreek, and Brassica juncea plants [34,35,30]. Our results are in accordance with [14] who reported the similar results in broad bean plant under saline conditions by using TiO2 NPs (Figure 3).

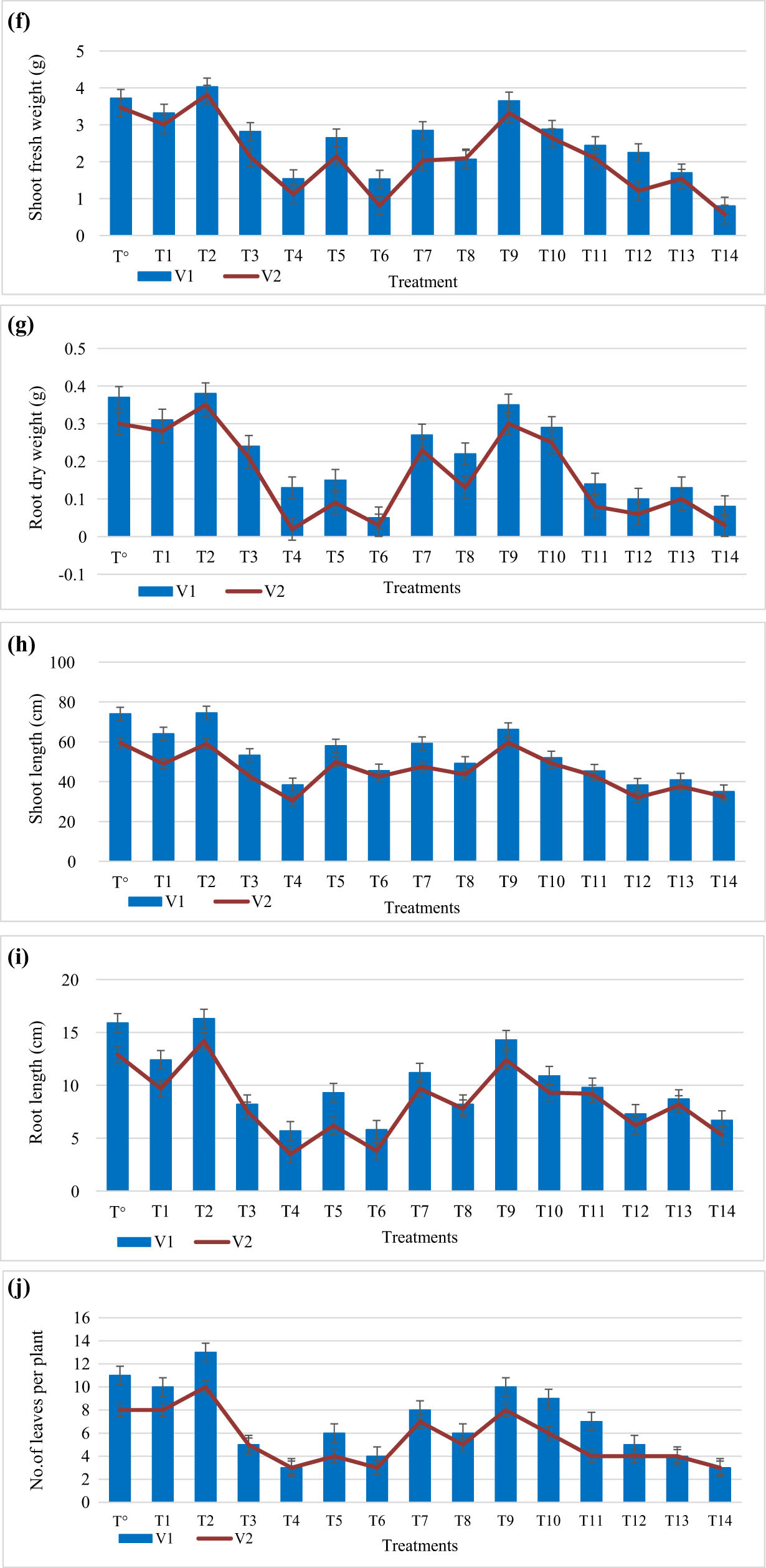

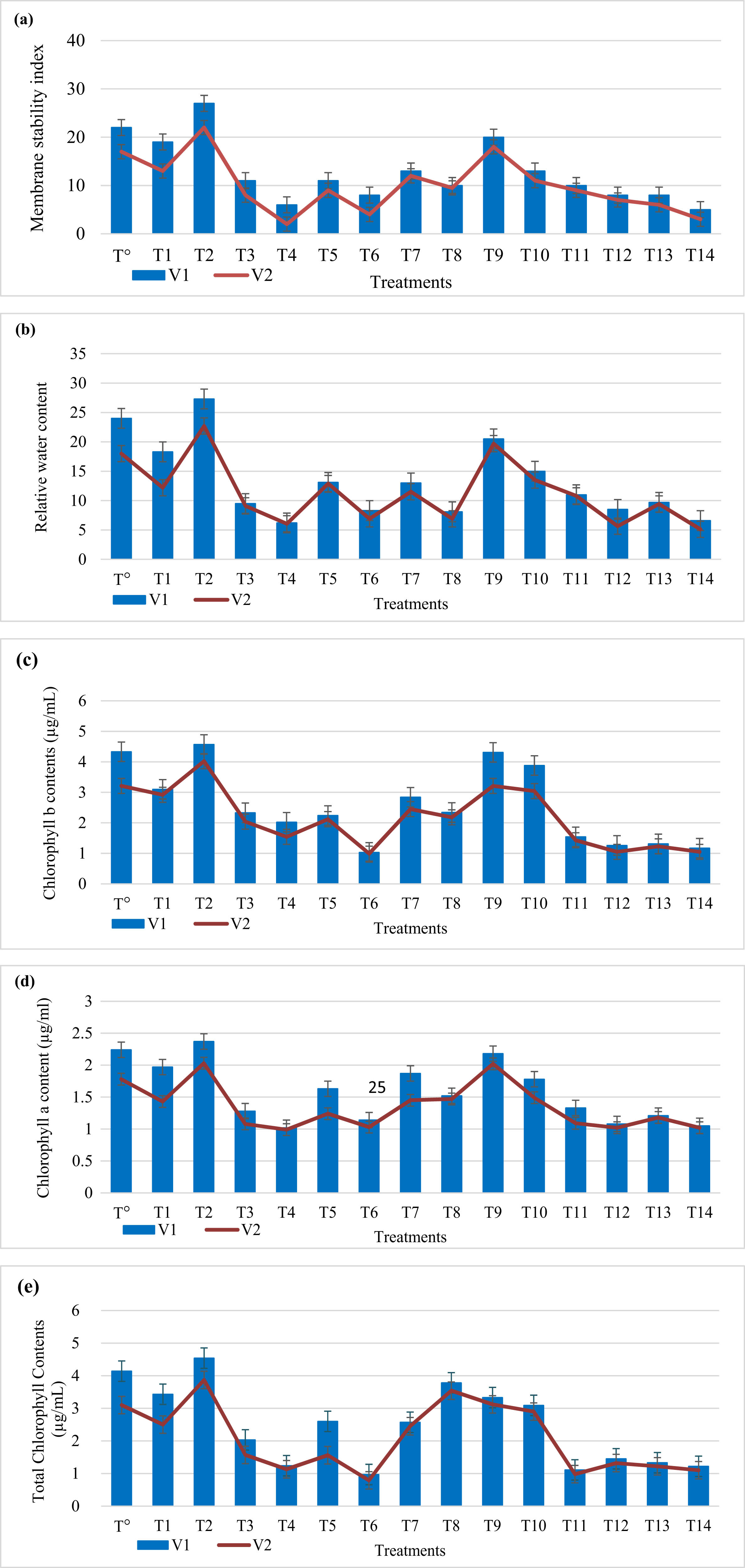

In contrast with control, physiological parameters of both wheat varieties are adversely affected by salinity. Application of salt stress 100 mM reduces MSI by 49.5% and 55.2%, RWC by 42.2% and 51.4%, chlorophyll a content by 34.8% and 40.7% and chlorophyll b content by 23.5% and 36.9%, and total chlorophyll contents by 29.8% and 35.4% in both wheat varieties, respectively. Application of salt stress 150 mM reduces MSI by 58.7% and 65.3%, RWC by 52.3% and 59.5%, chlorophyll a content by 44.4% and 50.9% and chlorophyll b content by 32.6% and 41.5%, and total chlorophyll contents by 40.2% and 49.2% in both wheat varieties, respectively.

However, plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles at 40 mg/L improved MSI (40.5% and 60.1%), RWC (21.4% and 44.6%), chlorophyll a content (50.3% and 43.1%), chlorophyll b content (21.5% and 66.2%), and total chlorophyll content (11.6% and 40.2%) at 100 mM salt in both wheat varieties, respectively. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles at 40 mg/L showed improved MSI (20.6% and 40.1%), RWC (41.2% and 17.2%), chlorophyll a content (24.5% and 20.2%), chlorophyll b content (50.1% and 46.7%), and total chlorophyll content (18.9% and 53.1%) at 150 mM in both wheat varieties, respectively. In addition, considerable increase in MSI (10.5% and 7.3%), RWC (4.2% and 3.5%), chlorophyll a content (7.9% and 5.2%), chlorophyll b content (3.1% and 2.4%), and total chlorophyll content (10.2% and 8.7%) as compared to control.

MSI is negatively affected by salinity. Salinity has harsh effects on plant membrane. Salinity reduces the plant water content because of osmotic reduction. Under salinity stress ABA produces which causes stomatal closure that reduces uptake of water by roots which effect transpiration pull resulting in low water content in cell [36,37]. Our results are in accordance with [38] who reported similar results by the application of 5-aminolevulinic acid on Brassica napus L. (Figure 4).

Effect of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles on membrane stability index (a), relative water content (b), chlorophyll a (c), chlorophyll b (d), and total chlorophyll contents (e) under salinity stress.

Leaf chlorophyll contents are significantly reduced in wheat under saline condition. This reduction might be due to inhibition of chlorophyll biosynthesis [39,40]. Ghassemi-Golezani et al. [7] reported that saline conditions increase the production of chlorophylase enzyme activity and decrease the nitrogen uptake, which might be responsible for loss of chlorophyll contents and their low production [41].

Present study showed remarkable increase in chlorophyll contents due to application of 40 ppm TiO2 NPs. Abdel Latef et al. [14] reported that Zn nanoparticles improve photosynthetic pigments in lupine (Lupines termis) plants under saline conditions. Similar results were also reported on basil (Osimum bascilum) plant by silica nanoparticles [42].

In the present study, titanium dioxide nanoparticles at 40 mg/L showed significant increase in agronomic and physiological parameters of wheat varieties both in control irrigation and salinity stress, while increasing concentrations of titanium dioxide nanoparticles showed gradual decrease in both agronomic and physiological parameters.

4 Conclusion

Salinity is a predominant environmental stress that is responsible to delimit the yield of crop globally. Ameliorating salinity tolerance and eradication of detrimental consequences of salinity are major research challenges. In present study, we reported foliar applications of different concentrations of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles utilizing Buddleja asiatica L. leaf decoction. The exogenous treatment of biofabricated TiO2 NPs induced tolerance in wheat plants against salinity stress. It was noticed that 40 mg/L of TiO2 NPs is potent to improve the morphophysiological attributes, i.e., length of shoot, root and whole plant, dry and fresh weight, number of leaves per plant, chlorophyll contents, MSI, and RWC of wheat varieties. However, higher concentration, i.e., 60 and 80 mg/L, showed negative effect on both wheat varieties. It is deduced that TiO2 NPs have potential in ameliorating salinity resistance through improving development, growth, and physiology of wheat facing harsh salinity conditions.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledged the efforts of Dr. Bilal Javed and Syeda Sadaf Zahra for their valuable contribution in data analyses.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Naveed Iqbal Raja and Zia-Ur-Rehman Mashwani devised the study. Nilofar Mustafa performed experiments and wrote the first draft. Muhammad Ikram edited, reviewed, and revised the manuscript. Noshin IIyas and Maria Ehsan assisted in the characterization of NP samples. All authors reviewed and endorsed the final version of the manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed and endorsed final version of manuscript for submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Ikram M, Raja NI, Javed B, Hussain M, Ehsan M, Akram A. Foliar applications of bio-fabricated selenium nanoparticles to improve the growth of wheat plants under drought stress. Green Process Synth. 2020;9(1):706–14.10.1515/gps-2020-0067Search in Google Scholar

[2] Caverzan A, Casassola A, Brammer SP. Antioxidant responses of wheat plants under stress. Genet Mol Biol. 2016;39(1):1–6.10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2015-0109Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Ikram M, Javed B, Raja NI, Mashwani ZUR. Biomedical potential of plant-based selenium nanoparticles: a comprehensive review on therapeutic and mechanistic aspects. Int J Nanomed. 2021;16:249.10.2147/IJN.S295053Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Tahjib-Ul-Arif M, Siddiqui MN, Sohag AAM, Sakil MA, Rahman MM, Polash MAS, et al. Salicylic acid-mediated enhancement of photosynthesis attributes and antioxidant capacity contributes to yield improvement of maize plants under salt stress. J Plant Growth Regul. 2018;37(4):1318–30.10.1007/s00344-018-9867-ySearch in Google Scholar

[5] Bami SS, Khavari-Nejad RA, Ahadi AM, Rezayatmand Z. TiO2 nanoparticles effects on morphology and physiology of Artemisia absinthium L. under salinity stress. Iran J Sci Technol Trans A Sci. 2020;45(1):27–40.10.1007/s40995-020-00999-wSearch in Google Scholar

[6] Parihar P, Singh S, Singh R, Singh VP, Prasad SM. Effect of salinity stress on plants and its tolerance strategies: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(6):4056–75.10.1007/s11356-014-3739-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Ghassemi-Golezani K, Taifeh-Noori M, Oustan SH, Moghaddam M, Rahmani SS. Physiological performance of soybean cultivars under salinity stress. J Plant Physiol Breed. 2011;1(1):1–7.10.5772/14741Search in Google Scholar

[8] Isayenkov SV, Maathuis FJM. Plant salinity stress: many unanswered questions remain. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1–11.10.3389/fpls.2019.00080Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Kumar U, Joshi AK, Kumari M, Paliwal R, Kumar S, Röder MS. Identification of QTLs for stay green trait in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in the ‘Chirya 3’ × ‘Sonalika’ population. Euphytica. 2010;174(3):437–45.10.1007/s10681-010-0155-6Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ditta A. How helpful is nanotechnology in agriculture?. Adv Nat Sci-Nanosci. 2012;3(3):033002.10.1088/2043-6262/3/3/033002Search in Google Scholar

[11] Duhan JS, Kumar R, Kumar N, Kaur P, Nehra K, Duhan S. Nanotechnology: the new perspective in precision agriculture. Biotechnol Rep. 2017;15:11–23.10.1016/j.btre.2017.03.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Satti SH, Raja NI, Javed B, Akram A, Mashwani ZUR, Ahmad MS, et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles elicited agro-morphological and physicochemical modifications in wheat plants to control Bipolaris sorokiniana. PLoS one. 2021;16(2):e0246880.10.1371/journal.pone.0246880Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Dağhan H. Effects of TiO2 nanoparticles on maize (Zea mays L.) growth, chlorophyll content and nutrient uptake. Appl Ecol Environ Res. 2018;16:6873–83.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Abdel Latef AAH, Srivastava AK, El‐Sadek MSA, Kordrostami M, Tran LSP. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles improve growth and enhance tolerance of broad bean plants under saline soil conditions. L Degrad Dev. 2018;29(4):1065–73.10.1002/ldr.2780Search in Google Scholar

[15] Khan MN. Nano-titanium dioxide (nano-TiO2) mitigates NaCl stress by enhancing antioxidative enzymes and accumulation of compatible solutes in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). J Plant Sci. 2018;11(1/3):1–11.10.3923/jps.2016.1.11Search in Google Scholar

[16] Javed B, Ikram M, Farooq F, Sultana T, Raja NI. Biogenesis of silver nanoparticles to treat cancer, diabetes, and microbial infections: a mechanistic overview. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105(6):2261–75.10.1007/s00253-021-11171-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] El‐Rady AAA, El‐Sadek MS, Breky MMES, Assaf FH. Characterization and photocatalytic efficiency of palladium doped‐TiO2 nanoparticles. Adv Nanopart. 2013;2:372–7.10.4236/anp.2013.24051Search in Google Scholar

[18] Iqbal M, Raja NI, Mashwani ZUR, Hussain M, Ejaz M, Yasmeen F. Effect of silver nanoparticles on growth of wheat under heat stress. Iran J Sci Technol Trans A Sci. 2019;43(2):387–95.10.1007/s40995-017-0417-4Search in Google Scholar

[19] Unyayer SY, Keles FOC. The antioxidant response of two tomato species with different tolerances as a result of drought and cadmium stress combination. Plant Soil Environ. 2005;51(2):57–64.10.17221/3556-PSESearch in Google Scholar

[20] Rizwan M, Ali S, Ibrahim M, Farid M, Adrees M, Bharwana SA, et al. Mechanisms of silicon-mediated alleviation of drought and salt stress in plants: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(20):15416–31.10.1007/s11356-015-5305-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Bruinsma. The quantitative analysis of chlorophyll a and b in plant extract. Photochem Photobiol. 1963;2:241–9.10.1111/j.1751-1097.1963.tb08220.xSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Ahmad U, Wali R, Ilyas N, Batool N, Gul R. Evaluation of compost with different NPK level on pea plant under drought stress. Pure Appl Biol. 2015;4(2):261.10.19045/bspab.2015.42016Search in Google Scholar

[23] Iqbal M, Asif S, Ilyas N, Raja NI, Hussain M, Ejaz M, et al. Smoke produced from plants waste material elicits growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by improving morphological, physiological and biochemical activity. Biotechnol Rep. 2018;17:35–44.10.1016/j.btre.2017.12.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Klinsukon C, Lumyong S, Kuyper TW, Boonlue S. Colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improves salinity tolerance of eucalyptus (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) seedlings. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–10.10.1038/s41598-021-84002-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Manzoor K, Ilyas N, Batool N, Ahmad B, Arshad M. Effect of salicylic acid on the growth and physiological characteristics of maize under stress conditions. J Chem Soc Pak. 2015;37:3.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Xu J, Li QQ, Zhou CW, Wang RZ, Du SS, Yang L, et al. Research on quick freezing technology of sword bean (Canavalia gladiate). Appl Mech Mater. 2012;140:421–5.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.140.421Search in Google Scholar

[27] Rajakumar G, Rahuman AA, Roopan SM, Chung IM, Anbarasan K, Karthikeyan V. Efficacy of larvicidal activity of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Mangifera indica extract against blood-feeding parasites. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(2):571–81.10.1007/s00436-014-4219-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Vijayalakshmi R, Rajendran V. Synthesis and characterization of nano-TiO2 via different methods. Arch Appl Sci Res. 2012;4(2):1183–90.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Thakur BK, Kumar A, Kumar D. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. South Afr J Botany. 2019;124:223–7.10.1016/j.sajb.2019.05.024Search in Google Scholar

[30] Mohamed AKS, Qayyum MF, Abdel-Hadi AM, Rehman RA, Ali S. Interactive effect of salinity and silver nanoparticles on photosynthetic and biochemical parameters of wheat. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2017;63(12):1736–47.10.1080/03650340.2017.1300256Search in Google Scholar

[31] Hussain S, Khaliq A, Tanveer M, Matloob A, Hussain HA. Aspirin priming circumvents the salinity-induced effects on wheat emergence and seedling growth by regulating starch metabolism and antioxidant enzyme activities. Acta Physiol Plant. 2018;40(4):68.10.1007/s11738-018-2644-5Search in Google Scholar

[32] Rehman S, Abbas G, Shahid M, Saqib M, Farooq ABU, Hussain M, et al. Effect of salinity on cadmium tolerance, ionic homeostasis and oxidative stress responses in conocarpus exposed to cadmium stress: Implications for phytoremediation. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;171:146–53.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.12.077Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Sairam RK. Effect of moisture stress on physiological activities of two contrasting wheat genotypes. Indian J Exp Biol. 1994;32:584–93.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Jasim B, Thomas R, Mathew J, Radhakrishnan EK. Plant growth and diosgenin enhancement effect of silver nanoparticles in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.). Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25(3):443–7.10.1016/j.jsps.2016.09.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Shafi M, Zhang G, Bakht J, Khan MA, Islam UE, Khan MD, et al. Effect of cadmium and salinity stresses on root morphology of wheat. Pak J Botany. 2010;42(4):2747–54.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Blatt MR, Armstrong F. K+ channels of stomatal guard cells: abscisic-acid-evoked control of the outward rectifier mediated by cytoplasmic pH. Planta. 1993;191(3):330–41.10.1007/BF00195690Search in Google Scholar

[37] Sharma R, Mishra M, Gupta B, Parsania C, Singla-Pareek SL, Pareek A. De novo assembly and characterization of stress transcriptome in a salinity-tolerant variety CS52 of Brassica juncea. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126783.10.1371/journal.pone.0126783Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Naeem MS, Warusawitharana H, Liu H, Liu D, Ahmad R, Waraich EA, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid alleviates the salinity-induced changes in Brassica napus as revealed by the ultrastructural study of chloroplast. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2012;57:84–92.10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.05.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Turkyilmaz B. Effects of salicylic and gibberellic acids on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under salinity stress. Bangladesh J Botany. 2012;41(1):29–34.10.3329/bjb.v41i1.11079Search in Google Scholar

[40] Tang W, Yueh SH, Fore AG, Hayashi A. Validation of Aquarius sea surface salinity with in situ measurements from Argo floats and moored buoys. J Geophys Res Ocean. 2014;119(9):6171–89.10.1002/2014JC010101Search in Google Scholar

[41] Kanwal S, Ilyas N, Shabir S, Saeed M, Gul R, Zahoor M, et al. Application of biochar in mitigation of negative effects of salinity stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J Plant Nutr. 2018;41(4):526–38.10.1080/01904167.2017.1392568Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kalteh M, Alipour ZT, Ashraf S, Marashi Aliabadi M, Falah Nosratabadi A. Effect of silica nanoparticles on basil (Ocimum basilicum) under salinity stress. J Chem Health Risks. 2018;4:3.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Nilofar Mustafa et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis