Abstract

Phoxim is a significant insecticide, and its current synthesis method has some shortcomings such as the high risk of explosion and the trans structure (main impurity) is hard to control. Our work solved the above disadvantages by introducing macromolecular alcohol (benzyl alcohol, etc.) as the starting material and optimizing the intermediate reaction conditions. Compared with the current synthesis route, the synthetic method has the following advantages: (1) intermediate benzyl nitrite has a high boiling point and strong safety; (2) intermediate α-cyanobenzaldehyde oxime sodium are almost (≥99%) cis structure, and no further refinement was required, which greatly reduced the amount of waste water produced; and (3) The high yield of phoxim was maintained at 72.9%.

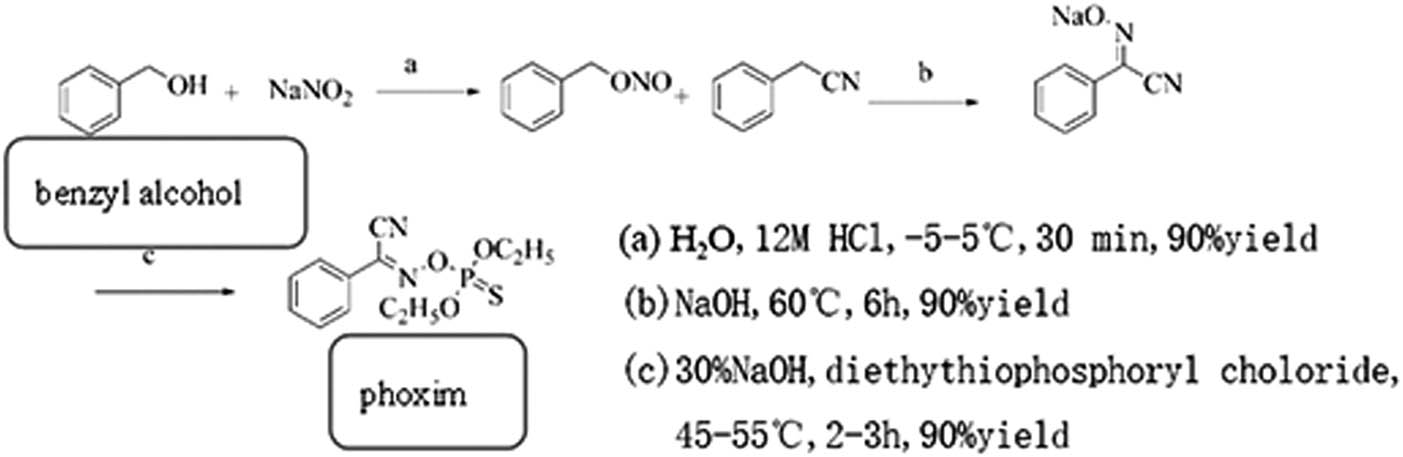

Graphical abstract

A new method to synthesize phoxim.

1 Introduction

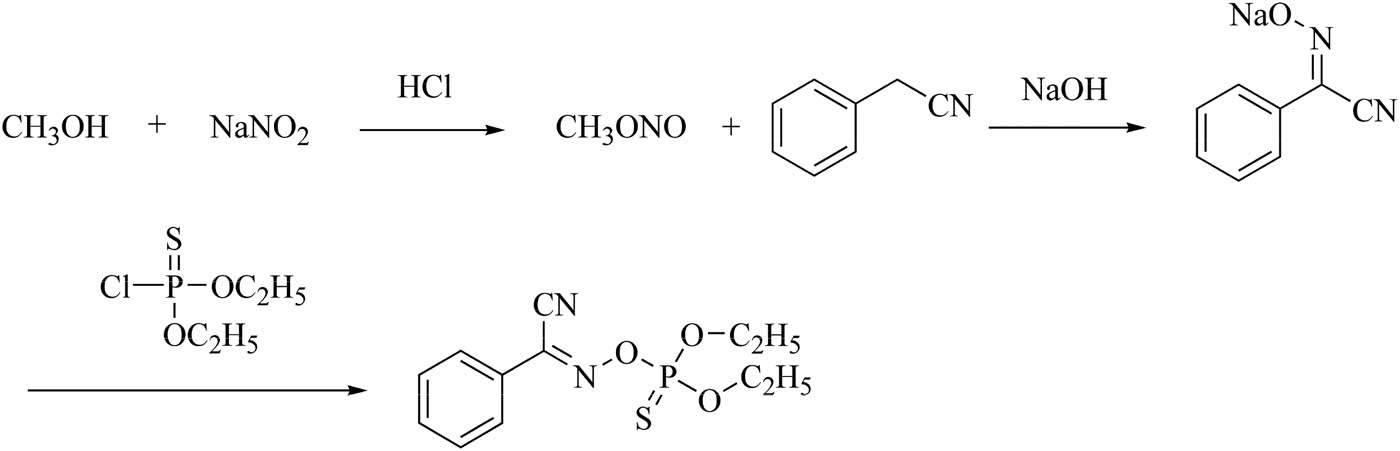

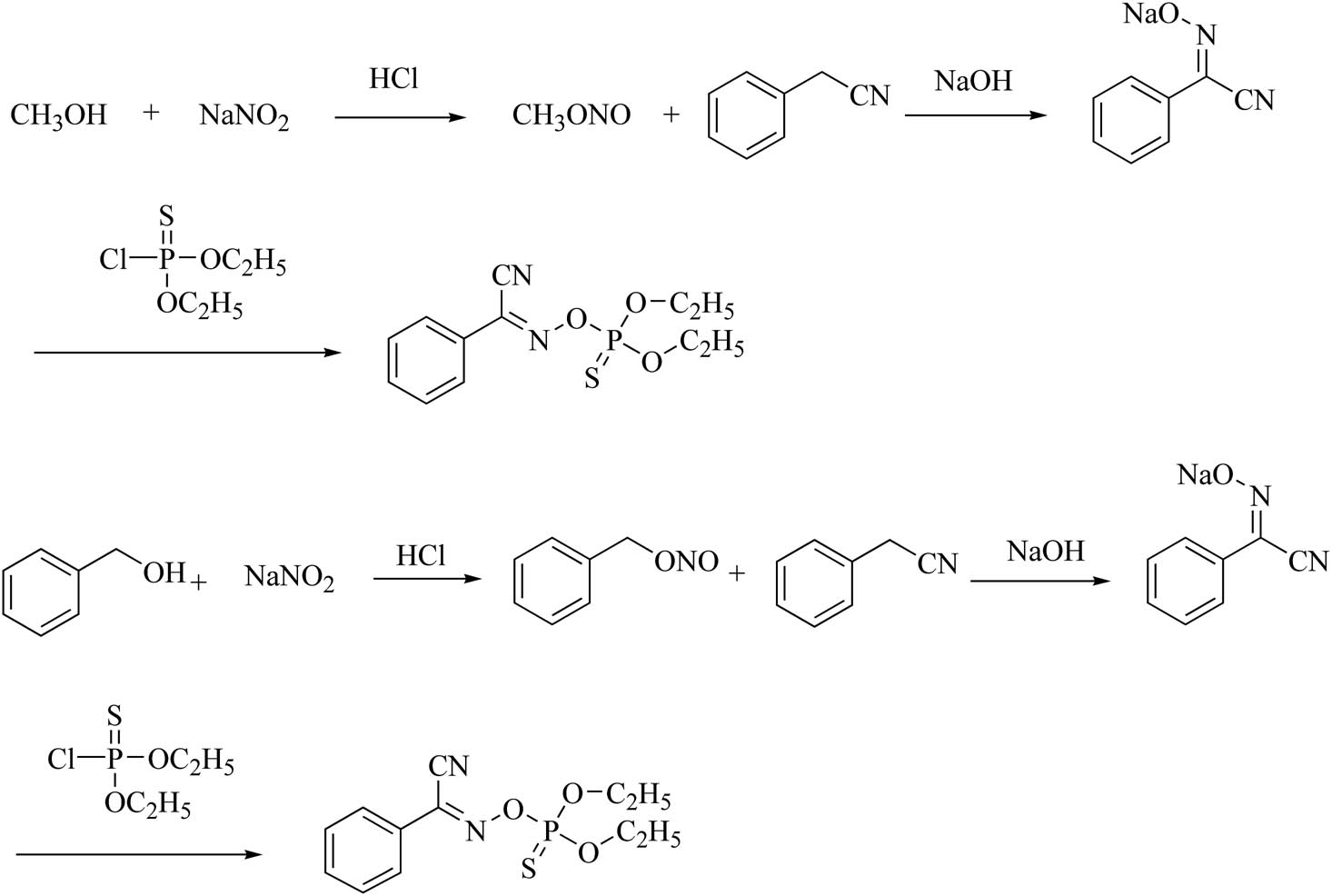

Phoxim, O,O-diethyl-α-cyano benzoxime phosphorothioate, is a broad-spectrum, highly efficient, and low-toxic organophosphorus insecticide, which had widely been used because of its strong application characteristics of unstable to light and short residual period in the field. Generally, the procedure of synthesizing phoxim was achieved using methanol or ethanol as the starting material to generate α-cyanobenzaldehyde oxime sodium (hereinafter also referred to as sodium oxime) [1,2,3,4], followed by further reaction with diethyl chlorothiophosphate to generate phoxim (see Scheme 1). Nevertheless, the method still has many shortages, for example, irrespective of the starting material used – methanol or ethanol – the boiling point [bp. from −11°C to −13°C (760 mm Hg) or bp. 16–18°C (760 mm Hg)] of the intermediate produced by their esterification is not high enough to keep safety; ethyl nitrite or methyl nitrite is easy to blow up, which is comparatively dangerous during the manufacturing operation. In addition, quiet a lot of trans structure (40%) is found in these sodium oximes, so that further refinement was required to adjust trans to cis structure, thus a large amount of waste water and waste acid produced increased the complexity of the experiment. Some researchers changed the treatment of waste water and waste acid, but they did not solve the safety problem of intermediates [5,6]. Other researchers [7,8,9,10,11] used isoamyl nitrite to react with phenylacetonitrile to generate sodium oxime, but it also generated lots of trans oxime sodium. After isopentanol was used to synthesize sodium oxime, further purification was required, which increased the complexity of the experiment.

Synthesis of phoxim from methanol.

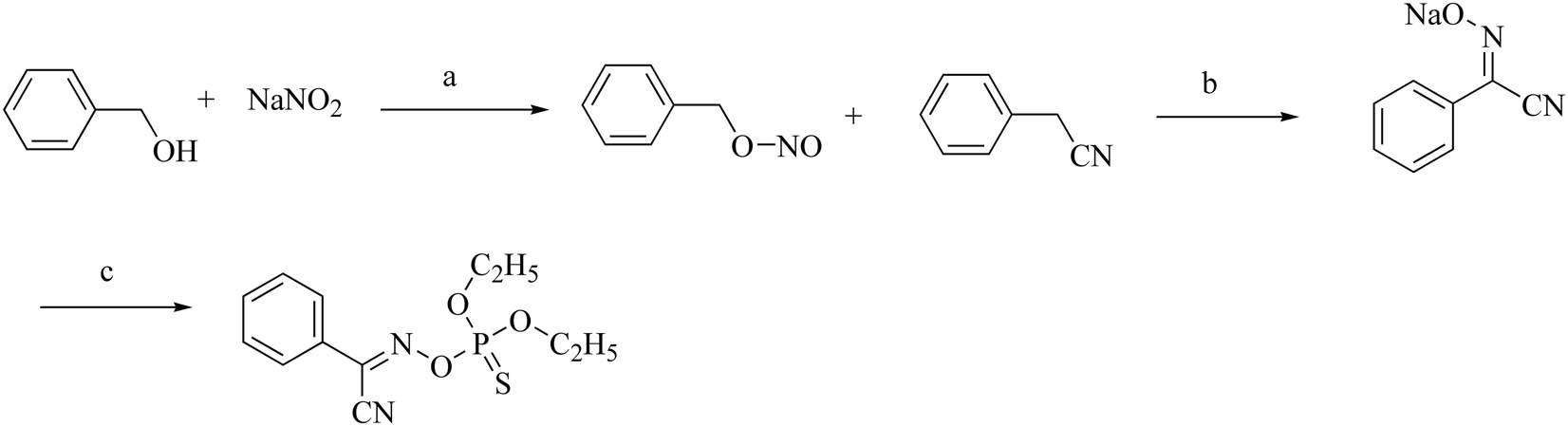

This article designed a new route (Scheme 2) for the synthesis of phoxim, and the route is characterized by the introduction of macromolecular alcohol (benzyl alcohol, etc.) to prepare the key intermediates benzyl nitrite and sodium oxime. Možina et al. [12], Aellig et al. [13], Sheng et al. [14], and other researchers used benzyl alcohol as the raw material to generate benzyl nitrite, which was considered a better selectivity for benzaldehyde but less for benzyl nitrite. The new method has several advantages, such as the intermediate benzyl nitrite has a great selectivity and high bp. of 70−72°C (760 mm Hg), so that the safety factor greatly improved compared with methyl nitrite and ethyl nitrite. It was found that the intermediate sodium oxime was almost cis structure (≥99%) without further refinement. At the same time, the reaction can maintain a good yield, 72.9% totally (consisting of three steps).

Synthesize of phoxim. Reagent and conditions: (a) H2O, 12 M HCl, from −5℃ to 5℃, 30 min, 90% yield; (b) NaOH, 60℃, 6 h, 90% yield; (c) 30% NaOH, diethylthiophosphoryl chloride, 45–55℃, 2–3 h, 90% yield.

2 Materials and methods

All the reagents and solvents used for the experiment were purchased from Macklin and used without further purification. The synthesized compound structure was confirmed by 1H NMR and IR. 1H NMR were recorded on Varian 400 MHz NMR spectrometer (DMSO or D2O is solvent); IR were recorded on Nexus 470 infrared spectrometer. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on precoated plates, and spots were visualized under ultraviolet light (254 nm).

2.1 Synthesis of benzyl nitrite

Sodium nitrite (0.5 mol) and benzyl alcohol (0.5 mol) were dissolved in 100 mL water, 0.925 mol hydrochloric acid (37%) was added dropwise, and the temperature of reaction system was maintained at less than 5°C. The reaction mixture is stirred for 0.5 h. TLC (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate = 3:1) detects whether the reaction was completed. Separate the organic layer and dry with anhydrous magnesium sulfate, 61.6 g yellow liquid benzyl nitrite was obtained, with a yield of 90%.

Benzyl nitrite: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.76 (s, 2H), 7.36 (s, 5H). IR (KBr) ν: 1,654, 1,400, 1,496, 1,560, 1,654, 669, 744, 787 cm−1.

2.2 Synthesis of α-cyanobenzaldehyde oxime sodium

Into the reaction system of 0.4 mol phenylacetonitrile and 0.4 mol sodium hydroxide, slowly add 0.52 mol benzyl nitrite dropwise and the temperature was maintained at below 60°C. After the completion of the dropwise addition, the temperature was maintained but with stirring for 2−3 h. TLC (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate = 2:1) detects whether the reaction is complete; 100 mL water was added and saved it for later use.

α-Cyanobenzaldehyde oxime sodium, yellow-brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.51 (s, 3H), 7.69 (s, 2H). IR (KBr) ν: 2,236, 1,498, 3,130, 1,685, 1,654, 1,617, 1,560, 1,498, 1,413, 1,282, 968, 765, 689 cm−1.

2.3 Synthesis of phoxim

The aqueous solution of sodium oxime obtained in the previous step (Section 2.2) was taken and the pH of the reaction system was adjusted to 10 or 11. Subsequently, 1 equivalent of O,O-diethylthiophosphoryl chloride was added dropwise to the reaction system to maintain the temperature below 55°C. Keeping the temperature constant for 2 h, then check whether the reaction is complete by TLC (petroleum ether:ethyl acetate = 1:1). Then the pH of the reaction solution was adjusted to 8−9 by 30% liquid alkali. Separating it by the separating funnel, the aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane and incorporated into the organic layer. Next 70% hot water (50°C) was added to the organic layer, the pH adjusted to 8−9 by NaOH (30%), and the organic layer was separated. Repeat the step mentioned above, but adjust the pH to 6 after the addition of hot water (50°C) to the organic layer. The organic layer was dehydrated and rotary evaporated to obtain the yellow transparent liquid, phoxim, with a yield of 90%.

Phoxim: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.20 (t, J = 6 Hz, 3H), 1.29 (t, J = 6 Hz, 3H), 3.55–3.60 (m, 2H), 3.88–3.95 (m, 2H), 7.56 (t, J = 8 Hz, 3H), 7.80 (d, J = 4 Hz, 2H). IR (KBr) ν: 3,135, 2,980, 2,238, 1,496, 1,447, 1,400, 1,321, 1,162, 1,000, 855, 820, 768, 697, 669 cm−1.

3 Results and discussion

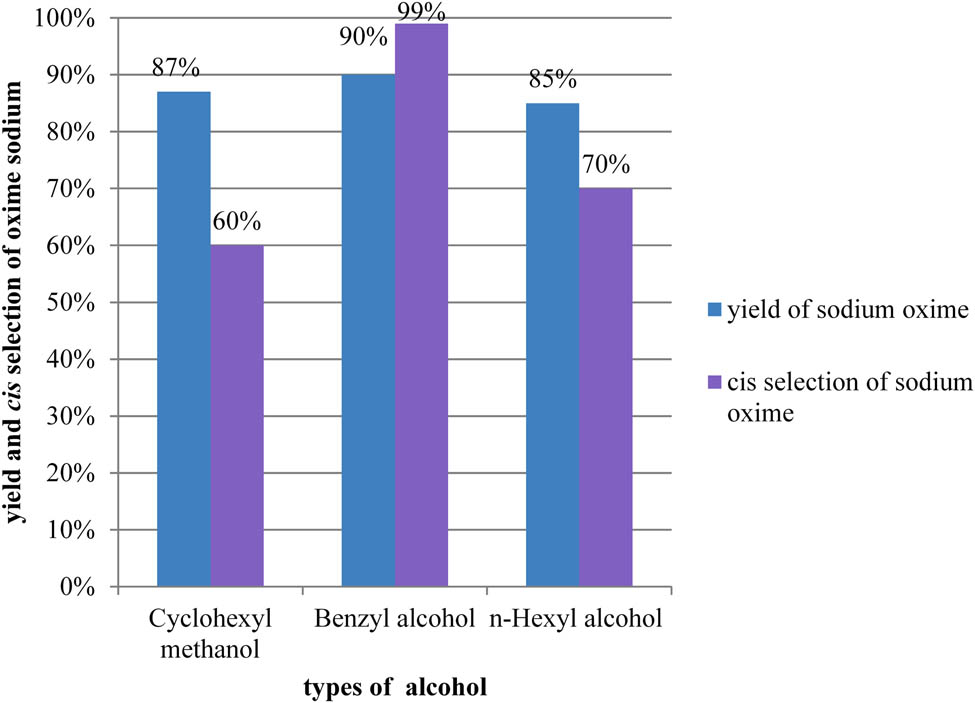

Figure 1 shows that the types of alcohol affect the yield and cis–trans ratio of sodium oxime. The cis–trans isomer ratio of sodium oxime after the reaction of cyclohexyl methyl nitrite produced by cyclohexyl methanol with phenylacetonitrile, resulting in sodium oxime, is 3:2, the reason may be that the cyclohexyl ring is a twisted hexagonal structure with less steric hindrance and increased formation of sodium transoxime. Similarly, the ratio of cis–trans isomers of n-hexyl alcohol is 7:3; the reason may be that linear alkanes are not planar structures, and hence each bond-forming atom can freely rotate around the bond axis. Using benzyl alcohol as the starting material to produce benzyl nitrite, followed by further reaction with phenylacetonitrile, the sodium oxime produced under the optimal conditions generated almost (≥99%) cis structure under the premise that the yield was maintained at a high level. The mechanism may be that the benzene ring has a stable rigid structure and a large steric hindrance, making the reaction easier to generate a cis structure. In other words, the α-C of benzyl cyanide attacking the benzyl nitrite is more inclined to cis at a relatively high temperature, which greatly saved the cost of adjusting cis–trans isomerization and the safety is also improved.

Effect of different alcohol on the yield of sodium oxime and proportion of cis-sodium oxime.

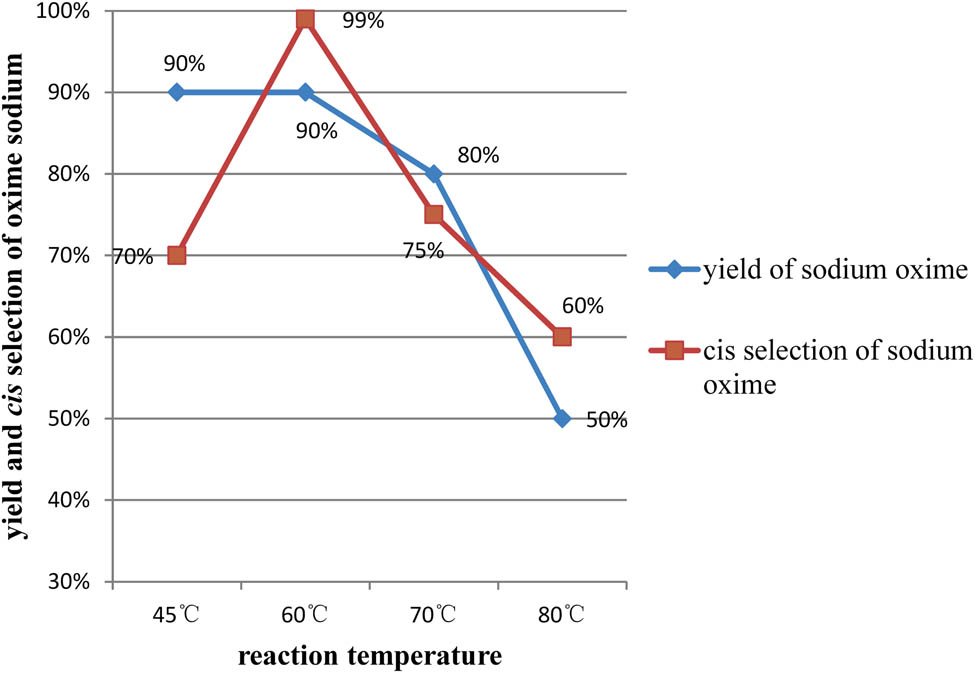

When the reaction temperature is 45°C, the maximum yield of 90% of sodium oxime is obtained in 8−10 h, so 60°C is the optimal condition (Figure 2). Temperature will affect not only the yield of sodium oxime but also its cis–trans. Experiments show that at 60°C, not only the yield of sodium oxime is the highest, but also the structure was required.

Effect of temperature on the yield of sodium oxime and proportion of cis-sodium oxime.

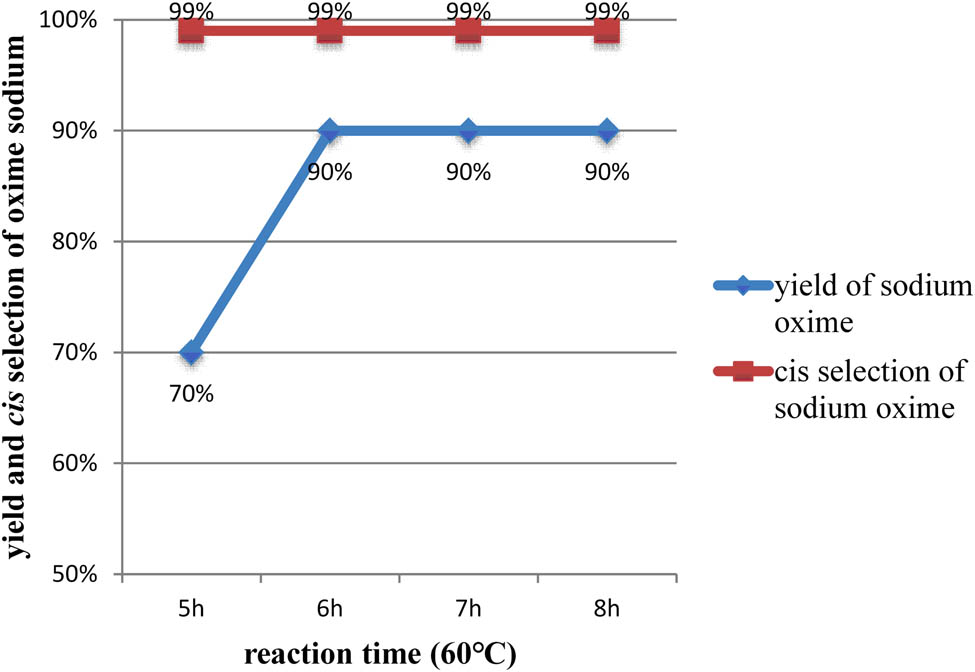

Figure 3 shows the best reaction condition is 6 h at 60°C, and extending the reaction time cannot have a more beneficial effect on the experiment.

Effect of reaction time on the yield of sodium oxime and proportion of cis-sodium oxime at 60℃.

After optimizing the experimental conditions, we know that the ratio of benzyl nitrite made in the first step to phenylacetonitrile is 1.3:1, the types of alkali has a great influence on the yield of sodium oxime, of which NaOH has the best effect, Na2CO3 has the poor effect and NaHCO3 cannot even make the reaction proceed. Sodium hydroxide was used as the reaction reagent, and benzyl nitrite was added dropwise to control the temperature of system, after that the temperature was maintained for 2−3 h. Finally, the highest yield of sodium oxime was 90% and almost (≥99) in cis form, with no further refinement.

4 Conclusion

This article for the first time introduced macromolecular alcohol (benzyl alcohol, etc.) as the starting material in the synthesis of phoxim, compared with the current industrialized process using small molecular alcohols (methanol and ethanol) as the starting materials (Scheme 3). The new synthetic method has high safety that benzyl alcohol is not easy to blow up; good selectivity that sodium oxime is almost in a cis product (≥99%); cost reduction that reduce the procedure of waste water and waste acid dealing, which means that generated sodium oxime did not require further refinement. Through optimization of reaction conditions, the yield of phoxim was maintained at a high level (72.9%). Overall, our work provides a practical, safe, efficient and green method of phoxim synthesis.

Comparison of current and new methods.

-

Funding information: This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation (No. 21773094).

-

Author contributions: Changzan Dong, Guang Qian, and Jie Zhu contributed to the conception of the study; Changzan Dong and Jinwen Qiao performed the experiment; Hongwei Zhu and Guang Qian contributed significantly to analysis and manuscript preparation; Yupeng He and Jie Zhu helped in performing the analysis with constructive discussions; Changzan Dong and Guang Qian performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Shi WG, Xu ZM, Huang QZ, Cui AN, Wang MY. Study on optimum technological conditions of phoxim synthesis. Hebei Chem Ind. 1997;3:1–2.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wu ZL, Hu XW. Process improvement of phoxim synthesis. Agrochemicals. 1996;5:19–20. 10.16820/j.cnki.1006-0413.1996.05.004.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Wang AB. Refined α-cyanobenzoxime and its preparation process. C.N. Patent 1353107; 2002 June.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zheng SF, Ji XH, Mu MR, Song SQ, Li DZ, Li LJ, et al. A production method of phoxim. C.N. Patent 1073445; 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Qi TL. Recycle of sodium oxime from phoxim synthesis wash water. Agrochemicals. 1994;2:11. 10.16820/j.cnki.1006-0413.1994.02.003.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Chen XR, Liu QD, Qi YF, Teng L. Synthetic process of phoxim technical. C.N. Patent 201610265200.9; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Cao GH. Review on the production process of phoxim. Agrochemicals. 1989;2:13–5. 10.16820/j.cnki.1006-0413.1989.02.007.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Liu K, Chen ZB, Zhang FL, qian C, Tao SW, Xu QM, et al. Cu-mediated stereoselective [4+2] annulation betweenn-hydroxybenzimidoyl cyanide and norbornene. J Org Chem. 2018;83:8457–63. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b01081.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Kang Z, Zhang J, Sun Q, Guan AY, Liang B, Li M, et al. Isothiazolopyrimidinone compound and its use. C.N. Patent 103288855; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kang Z, Zhang J, Sun Q, Li M, Wang JF, Guan AY, et al. Isothiazole compounds and their use as fungicides. C.N. Patent 103288771; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Tisdell FE, Johnson PL, Pechacek JT, Suhr RG, Devries DH, Denny CP, et al. 3-(substituted phenyl)-5-(substituted heterocycyl)-1,2,4-triazole compounds. US Pat 2000024739. 2000 July.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Možina Š, Stavber S, Iskra J. Dual catalysis for aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohols – nitric acid and fluorinated alcohol. Eur J Org Chem. 2017;3:448–52. 10.1002/ejoc.201601339.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Aellig C, Girard C, Hermans I. Aerobic alcohol oxidations mediated by nitric acid. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:12355–60. 10.1002/anie.201105620.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Sheng XB, Ma H, Chen C, Gao J, Yin GC, Jie Xu. Acid-assisted catalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol by NOx with dioxygen. Catal Commun. 2010;11:1189–92. 10.1016/j.catcom.2010.06.012.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Changzan Dong et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis