Abstract

l-Cysteine is widely used in food, medicine, and cosmetics. In this study, a recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase was used to complete the biological transformation of l-serine to l-cysteine, and bioconversion of l-cysteine was investigated by tryptophan synthase. The biotransformation of l-cysteine was optimized by response surface methodology. The optimal conditions obtained are 0.13 mol·L−1 l-serine, 75 min, 130 W ultrasound operation, where the V max of tryptophan synthase is 25.27 ± 0.16 (mmol·h−1·(g-cells)−1). The V max of tryptophan synthase for the biosynthesis without ultrasound is 12.91 ± 0.34 (mmol·h−1·(g-cells)−1). Kinetic analysis of the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase also showed that under the ultrasound treatment, the K m values of l-cysteine biosynthesis increase from 1.342 ± 0.11 mM for the shaking biotransformation to 2.555 ± 0.13 mM for ultrasound operation. The yield of l-cysteine reached 91% after 75 min of treatment after 130 W ultrasound, which is 1.9-fold higher than no ultrasound.

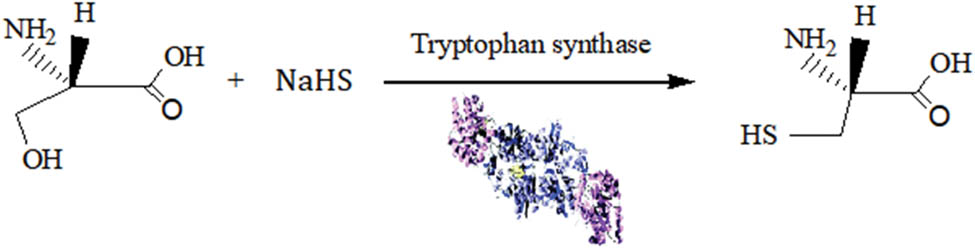

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

l-Cysteine is an amino acid that contains sulphydryl groups, and it is used in medicine, cosmetics, and food [1]. It is mainly derived from hydrolysed keratin in human and animal hair by hydrolysis and extraction. However, this preparation method leads to the unpleasant odour, and waste treatment of hydrolysed keratin is required [2]. Biocatalytic synthesis is environmentally friendly with little or no byproducts [3,4]. l-Cysteine is formed from l-serine in many microorganisms. O-Acetyl-l-serine is synthesized from acetyl-CoA and l-serine by l-serine O-acetyltransferase [5]. Enzymatic methods for producing l-cysteine include enzymatic synthesis [6]. Nakatani et al. reported that NrdH and Grx1 reduce SSC to l-cysteine. Expression of CysI and NrdH enhances l-cysteine yield [7]. Duan et al. reported the coinstantaneous cloning and expression of atcA and atcB for l-cysteine synthesis [8]. Joo et al. reported the synthesis of l-cysteine by Corynebacterium glutamicum with sulphur supplementation. These authors investigated the effect of combined expression of the transcriptional regulator CysR and CysE [9,10]. Enhancement by GlpE overexpression in E. coli for l-cysteine overproduction was successful [11]. The biosynthesis process of l-cysteine was investigated, and the microbial reactions were studied [12]. Wei et al. reported the engineering of a microorganism, Corynebacterium glutamicum, for the biosynthesis of l-cysteine [13]. Some microorganisms were used to synthesize l-cysteine, such as Lactococcus lactis [14], Pseudomonas putida [15], and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [16]. The productivity of l-cysteine synthesis by C. glutamicum was 290 mg−1 [17]. The results of a previous study show that ultrasound treatment can change the membrane permeability of microorganisms to improve the substrate reaction [18]. Zheng et al. reported that the biotransformation rate of water-soluble yeast β-glucan reached 36.2% under ultrasound [19]. Sharma et al. reported that sugar was synthesized by Aspergillus assiutensis VS34 under ultrasound [20]. Yao et al. observed greatly increased production of fumigaclavine C by Aspergillus fumigatus CY018 under ultrasound [21]. The biotransformation efficiency of astaxanthin was increased by Phaffia rhodozyma MTCC 7536 under ultrasonic treatment [22]. Tryptophan synthetase (EC 4.2.1.20) is a heterotetramer with an aaββ subunit structure in Escherichia coli. The enzyme can synthesize l-tryptophan with indole and l-serine as substrates [23]. The trp B and trp A genes (or trp BA genes) coexist in the tryptophan operon of the E. coli genome. The activities of both subunits increase upon complex formation and are further regulated by an intricate and well-studied allosteric mechanism. The function of a subunit is to decompose indole-3-glycerol phosphate into indole and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, while the function of the β subunit is to synthesize l-tryptophan. A direct evolution strategy was applied to engineer tryptophan synthase from E. coli to improve the efficiency of l-5-hydroxytryptophan synthesis [24]. The rate of l-cysteine formation from l-serine and sodium hydrosulphide with tryptophan synthase was 47%. The yield of l-cysteine synthesized by tryptophan synthase was low. The synthesis of l-cysteine by ultrasound-assisted tryptophan synthase was rare. Our innovations gave a high yield of l-cysteine with ultrasound-assisted tryptophan synthase. In the present study, tryptophan synthase (trpBA-trpA) was expressed in E. coli BL21. l-Cysteine was synthesized from l-serine and sodium bisulphide using tryptophan synthase by response surface methodology (RSM) under ultrasound treatment.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

Yeast powder, beef extract, and peptone were purchased from Alighting Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). l-Serine, l-cysteine, and sodium bisulphide were purchased from Sinopharma Co. Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Agarose, IPTG, and ampicillin were purchased from Nanjing Jitian Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Plasmid extraction kits and gel recovery kits were purchased from Aisjin Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Chemicals were analytical reagents.

2.2 Cloning and expression of tryptophan synthase

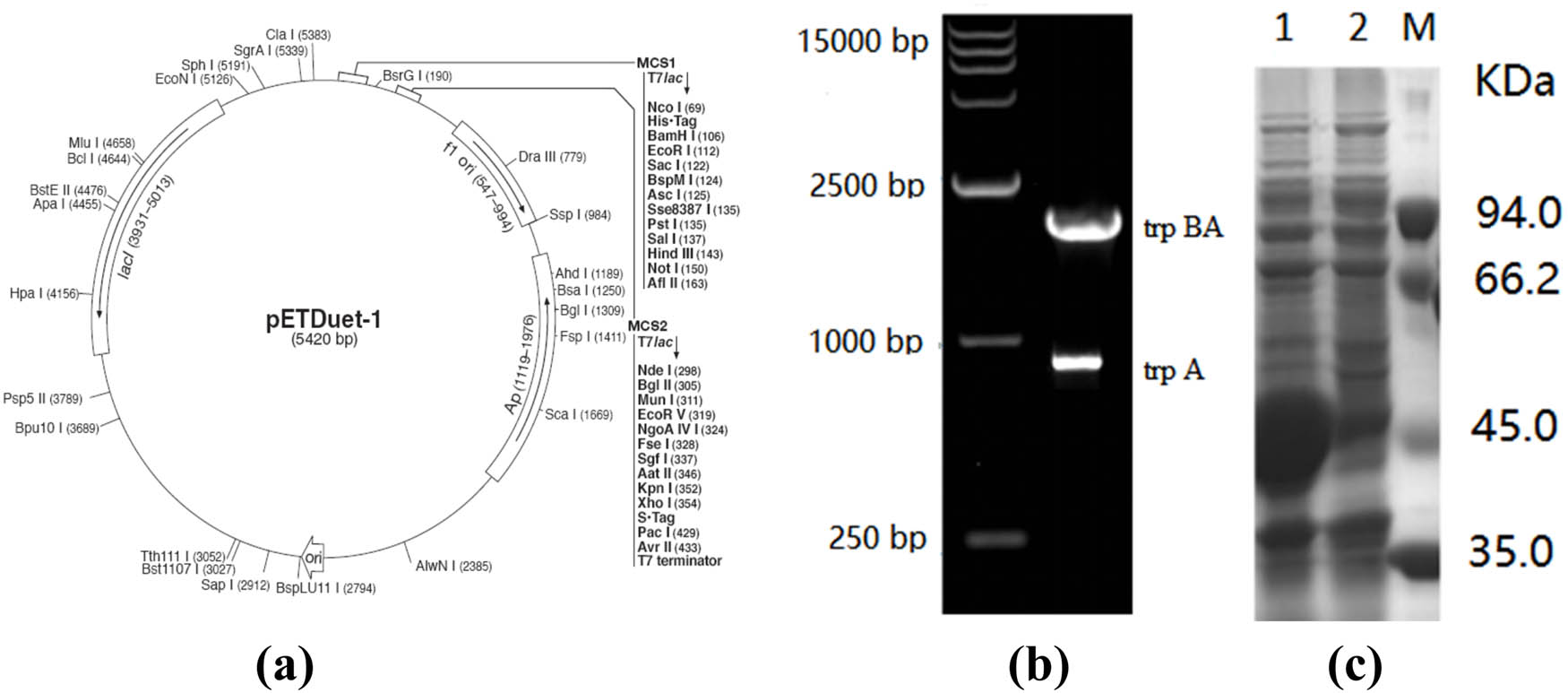

The tryptophan synthase gene from E. coli K-12 was obtained from the NCBI. trp BA, trp A were amplified using the primers P1(CCCCATATGACAACATTACTTAAC)/P2(CCCGAATTCTTAACTGCGCGTTT), P1(CCGCATATGATGGAACGCTAC)/P2(ATTCTCGAGTTAACTGCGCGT). The genes of tryptophan synthase were inserted into the pETDuet-1 plasmid to generate the pETDuet-trp BA-trp A plasmid (Figure 1a). trp BA and trp A genes were amplified by PCR and constructed with relevant plasmids. The amplified fragments were identified as trp BA and trp A genes and sequence determination. The constructed plasmids were identified by PCR to prove the correctness of the constructed genes. Then, the recombinant plasmid with the tryptophan synthase gene (trp BA-trp A) was transformed into E. coli BL21.

(a) Physical map of pETDuet-1. (b) Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of the trpBA and trp A genes. (c) SDS-PAGE analysis of tryptophan synthase (trpBA-trp A).

2.3 Bioconversion of l-serine to l-cysteine

To ensure that the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase has the ability to biosynthesize l-cysteine from l-serine, the whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase was centrifuged at 15,000×g for 15 min. The reaction mixture containing 0.1 mol·L−1 l-serine, 0.1 mol·L−1 NaHS, and 10 mg·mL−1 of the whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase was diluted using 0.1 M PBS buffer and incubated at 37°C, pH 8.0, under ultrasound treatment. All experiments with ultrasound and the control experiment without ultrasound treatment were performed with three replicates. After the reaction of the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase, the supernatant of the reaction mixture was obtained for analysis using an amino acid analyser (L-8900, Japan).

2.4 Analysis of l-serine and l-cysteine

The product of l-cysteine in the reaction mixture was analysed using an amino acid analyser (L-8900, Japan) with a separation column (4.6 mm × 60 mm, 50°C, sulphonate-type cationic resin). The injection volume was 20 µL.

2.5 Ultrasound operation of bioconversion

The effect of ultrasound on l-cysteine biosynthesis was investigated. The reaction of the recombinant E. coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase was executed in an ultrasonic tank with a power series ranging from 60 to 200 W (SB-120D, China). The recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase was added to 10 mL of the substrate containing 0.1 mol·L−1 l-serine, 0.1 mol·L−1 NaHS, and 10 mg·mL−1 whole cells at 37°C with ultrasound for different times.

2.6 Kinetic studies on ultrasound effects

To study the effects of l-cysteine from l-serine under ultrasound, the kinetic data of l-cysteine biosynthesis were obtained. The tryptophan synthase activity was determined under different concentrations (0.05–0.2 mol·L−1) of l-serine. The kinetic constants K and V of tryptophan synthase were calculated under different concentrations.

2.7 Optimization of l-cysteine biosynthesis

The bioconversion of l-cysteine was studied by response surface methodology. Factors such as l-serine, time, and ultrasound power were selected for analysis. The levels of the variables under ultrasonic power are shown in Table 1. The data of the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase were analysed via response surface methodology. All the experiments were done in triplicate. The results were presented as the mean ± SD (SPSS 22.0).

Variables and levels defined in the Box–Behnken design

| Factor | Variables | Low level (−1) | High level (+1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| X 1 | l-Serine | 0.05 | 0.2 |

| X 2 | Time | 30 | 120 |

| X 3 | Ultrasound power | 60 | 200 |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Expression of tryptophan synthase

The complete coding region of the trp BA and trp A genes from E. coli was obtained (Figure 1b). The reaction was carried out in a 50 µL volume, and the mixture containing 37.4 µL of water (nuclease-free), 5 µL of 10× Taq buffer (Mg2+ free), 3 µL of MgCl2 (25 mM), 1 µL of dNTP mixture (10 mM), 1 µL genomic DNA, 1 µL of each 3′ and 5′ primer, and 0.6 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U·mL−1). E. coli [pETDuet-trpBA-trpA/BL21(DE3)] were tested for tryptophan synthase overproduction with ampicillin (100 µg·mL−1). At 6 h after IPTG induction, cells were harvested and lysed, and intracellular proteins were analysed by SDS-PAGE. Recombinant tryptophan synthase (trp BA-trp A) appeared as two intense protein bands (45 and 30 kDa) (Figure 1c). Tryptophan synthase has found applications in many fields of synthetic chemistry, in particular, for the production of amino acids. An allosteric heterodimeric enzyme in the form of an αββα complex that catalyzes the biosynthesis of l-cysteine.

3.2 Ultrasound effect on l-cysteine bioconversion

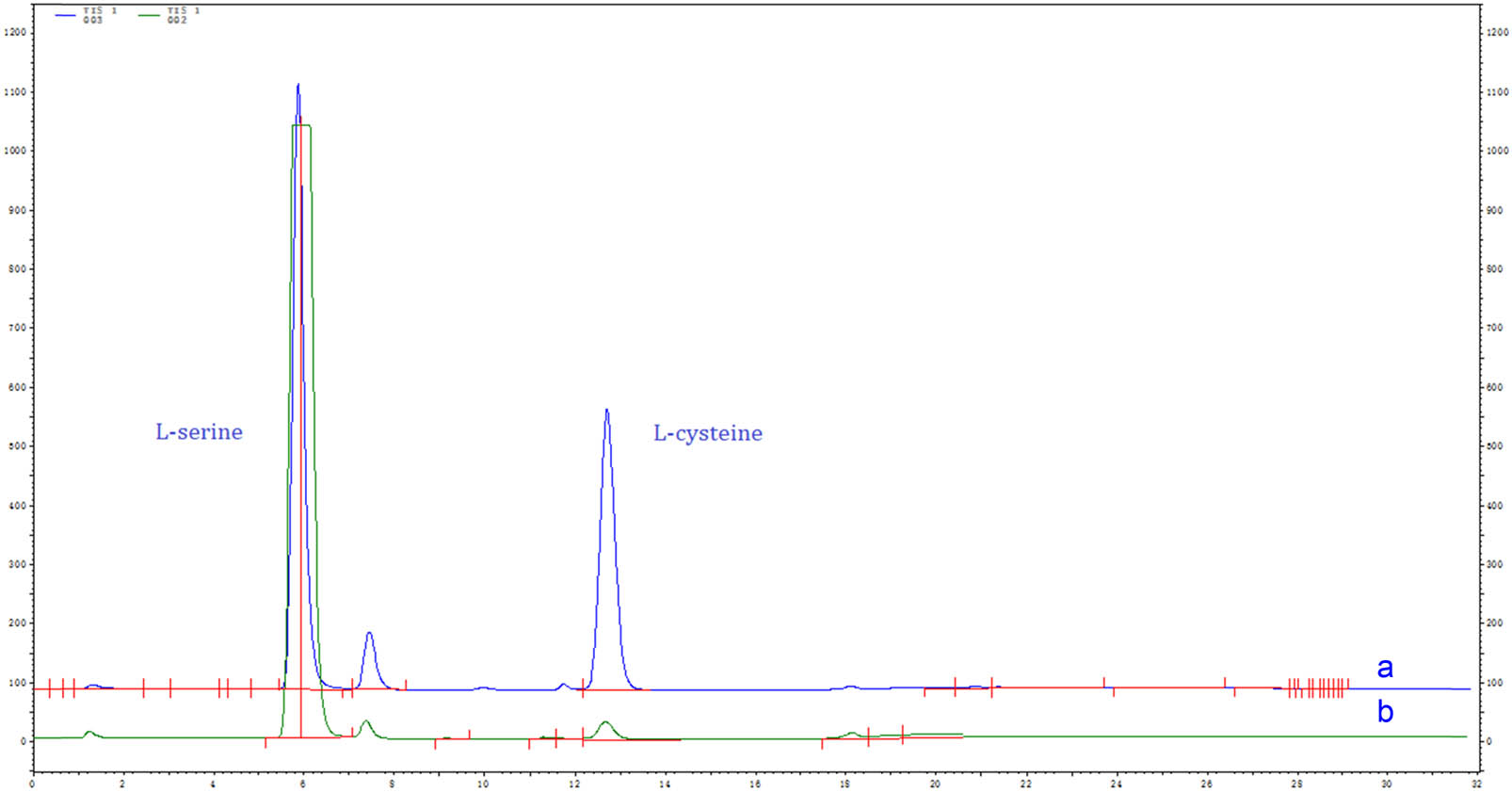

The rate of biotransformation is limited by the mass transfer of substrates or products, which is related to the properties of the reactants or products. Therefore, ultrasonic treatment can improve the efficiency of the ability of recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase to biotransform l-serine to l-cysteine. As shown in Figure 2a, the yield of l-cysteine reached 57.63% after 60 min of ultrasound treatment (100 W). However, the low yield of l-Cysteine from l-serine occurred within 60 min without ultrasonic treatment, and the yield of l-cysteine was only 13.46% after 60 min (Figure 2b). It is further suggested that ultrasonic treatment can improve the efficiency of the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase. Although bioconversion is the most feasible and specific method for production, the efficiency of the product conversion has some limitations, the mass transfer of the substrate through the cell membrane is among the main barrier for high bioconversion efficiency. Recently, ultrasound treatment has been widely used to enhance the efficiency of biocatalysis. It was interesting to find that a positive effect for bioconversion was observed when ultrasound operation was adopted. The acoustic energy with low-frequency ultrasound is beneficial for cell growth [25,26,27] and metabolite production [28,29,30]. Singh et al. reported that ultrasound has been used to enhance β-carotene production [31].

Analysis of the bioconversion of l-serine to l-cysteine by the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase. The products were analysed with an amino acid analyser (L-8900, Japan). (a) Ultrasound treatment; (b) no ultrasound treatment (100 W, 60 min, 0.10 mol·L−1 l-serine).

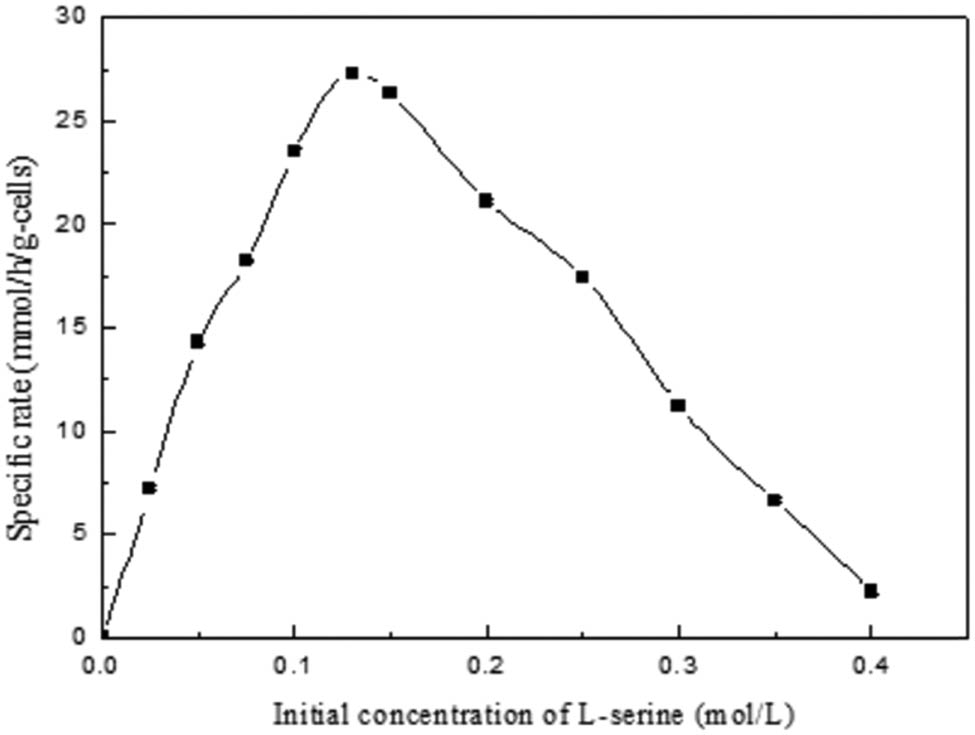

3.3 Catalytic kinetics of tryptophan synthase

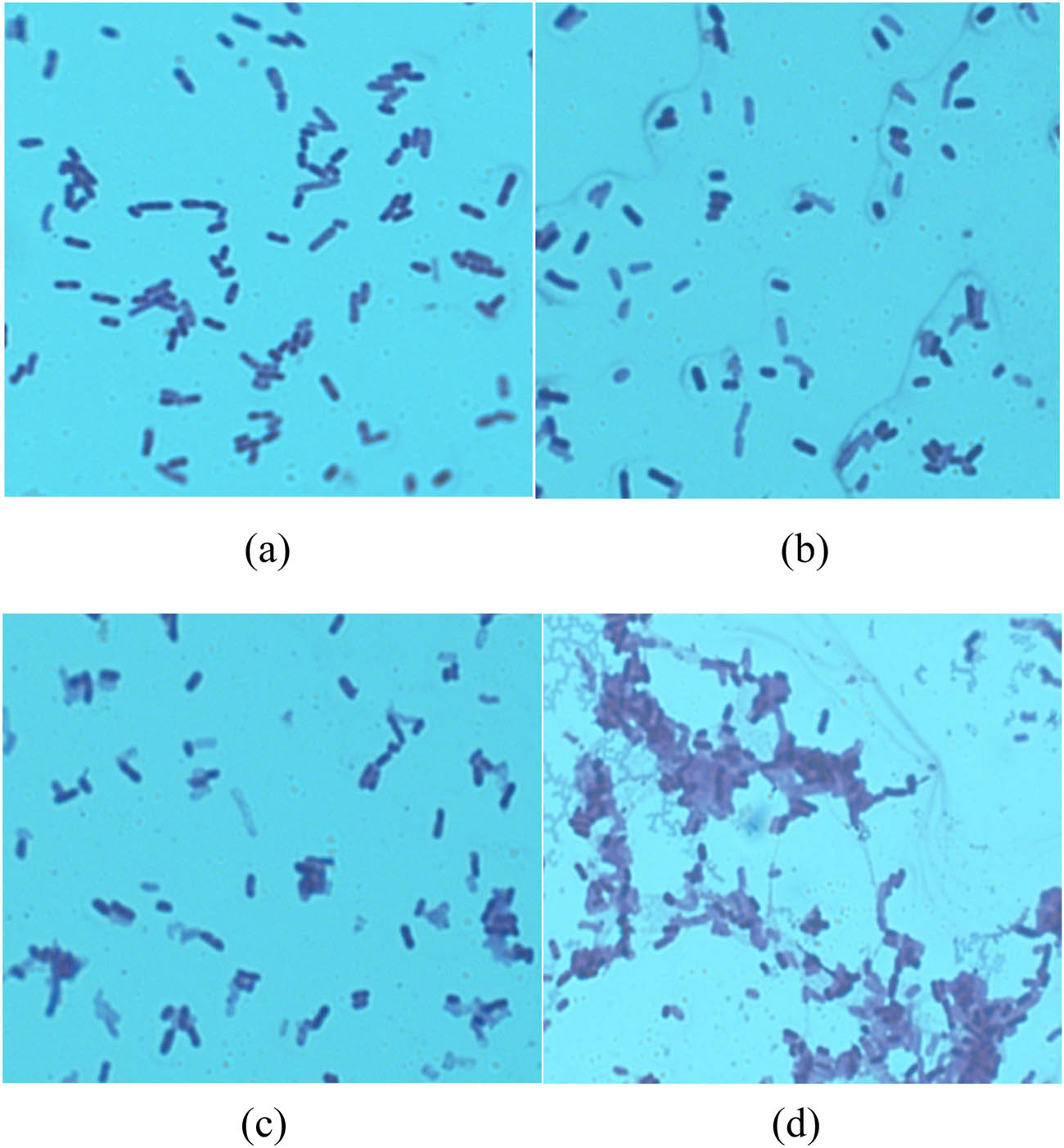

Ultrasound with 130 W was employed in the bioconversion of l-cysteine with different concentrations of l-serine, and the reaction rates of tryptophan synthase are shown in Figure 3. When the concentration of l-serine was lower than 0.13 mol·L−1, the reaction rate of tryptophan synthase increased sharply. The reaction rate of tryptophan synthase decreased when the concentration of l-serine was higher than 0.13 mol·L−1. The V max of tryptophan synthase was approximately 25.27 ± 0.16 (mmol·h−1·(g-cells)−1), whereas that of l-serine was approximately 0.13 mol·L−1. The effect curve shows that a high level of l-serine inhibits biotransformation. To research the ultrasound effect on tryptophan synthase, experiments under different ultrasound power values were conducted. Compared with previous research results, our experimental results significantly improved the yield of l-cysteine. Ultrasound enhanced the transport of l-serine and nutrients across the cell membrane with tryptophan synthase [32,33]. The cells of the recombinant E. coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase after the optimal ultrasound treatment were observed under a microscope. Microbe morphology remains intact at low ultrasonic power (0, 100, and 200 W; Figure 4a–c, respectively). However, the microbe morphology was destroyed under high ultrasonic power (300 W, Figure 4d).

Screening of l-cysteine bioconversion by the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase and ultrasound treatment.

Microbe morphology under different ultrasonic power: (a) 0 W, (b) 100 W, (c) 200 W, and (d) 300 W.

3.4 Experimental design

Parameters for the optimization study were concentration of l-serine, time and ultrasound power. The concentration of l-serine, time and ultrasound power affected the activity of tryptophan synthase. l-Serine (0.05–0.2 mol·L−1), time (30–120 min), and ultrasound power (60–200 W) were selected as the process variables (Table 1). All the experiments were done in triplicate. The Box–Behnken design for l-cysteine by the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase is listed in Table 2. A second-order polynomial equation of tryptophan synthase is as follows:

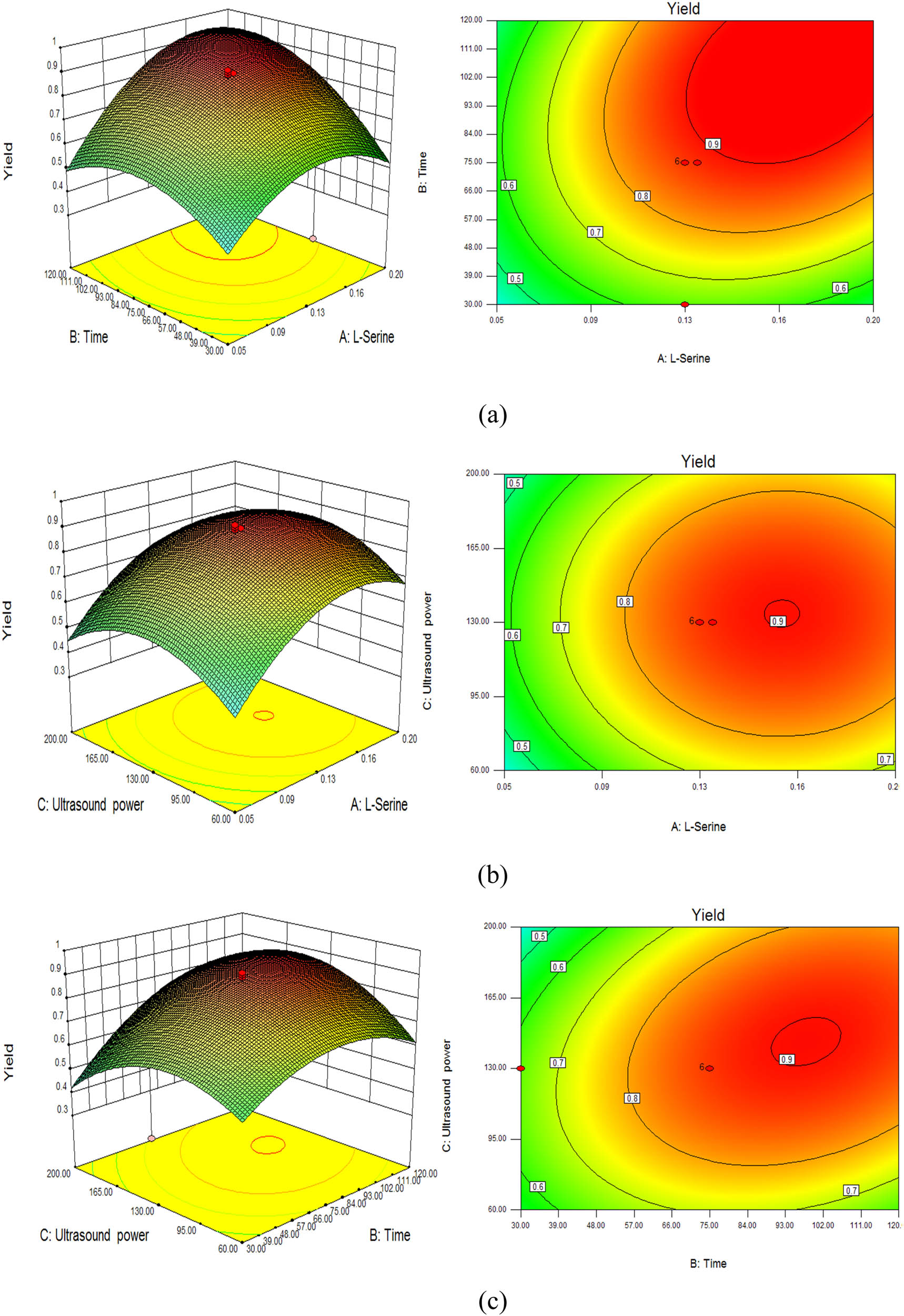

where Y is the yield of l-cysteine and X 1, X 2, and X 3 are l-serine (0.05–0.2 mol·L−1), time (30–120 min), and ultrasound power (60–200 W). The results showed that all factors (l-serine, time, and ultrasound power) had effects on the yield of l-cysteine (Table 2). To improve the biosynthesis of l-cysteine, the effects of different reaction conditions on l-cysteine production were investigated under different ultrasound power values. Among all the variables, l-serine concentration, time, and ultrasound power had effects on the biosynthesis of l-cysteine. Analysis of variance for the selected quadratic model is shown in Table 3. l-Cysteine biosynthesis was found to be affected by the ultrasound power, l-serine level, and the length of time (Figure 5). The effects of substrate concentration, time, and ultrasonic on product concentration were very significant and had similar significant effects. The product concentration increased first and then decreased with the increase of substrate concentration, time, and ultrasonic. The optimal bioconversion conditions for l-cysteine by tryptophan synthase were obtained. The optimal conditions obtained are 0.13 mol·L−1 l-serine, 75 min, and 130 W, where V max of tryptophan synthase is 25.27 ± 0.16 (mmol·h−1 per g-cells). The V max of tryptophan synthase for the biosynthesis without ultrasound is 12.91 ± 0.34 (mmol·h−1·(g-cells)−1) (Table 4). The predicted yield of l-cysteine reached 91.7% after 75 min of treatment after 130 W ultrasound. The real yield of l-cysteine reached 91% after 75 min of treatment after 130 W ultrasound, which is 1.9-fold higher than no ultrasound.

Box–Behnken design for l-cysteine by the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase

| No. | l-Serine (mol·L−1) | Time (min) | Ultrasound power (W) | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 60.00 | 0.34 |

| 2 | 0.13 | 120.68 | 130.00 | 0.81 |

| 3 | 0.20 | 120.00 | 200.00 | 0.77 |

| 4 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.89 |

| 5 | 0.20 | 120.00 | 60.00 | 0.65 |

| 6 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 247.73 | 0.57 |

| 7 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.91 |

| 8 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.89 |

| 9 | 0.20 | 30.00 | 60.00 | 0.53 |

| 10 | 0.13 | 30.00 | 130.00 | 0.34 |

| 11 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.9 |

| 12 | 0.05 | 120.00 | 60.00 | 0.23 |

| 13 | 0.20 | 30.00 | 200.00 | 0.34 |

| 14 | 0.05 | 30.00 | 60.00 | 0.44 |

| 15 | 0.05 | 120.00 | 200.00 | 0.34 |

| 16 | 0.25 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.65 |

| 17 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.91 |

| 18 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.91 |

| 19 | 0.13 | 75.00 | 130.00 | 0.9 |

| 20 | 0.05 | 30.00 | 200.00 | 0.23 |

Analysis of variance for the selected quadratic model

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F value | P-value Prob >F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1.12 | 9 | 0.12 | 8.00 | 0.0016 |

| A l-serine | 0.15 | 1 | 0.15 | 9.76 | 0.0108 |

| B Time | 0.14 | 1 | 0.14 | 8.89 | 0.0138 |

| C Ultrasound power | 3.44 × 10−3 | 1 | 3.442 × 10−3 | 0.22 | 0.0010 |

| AB | 0.053 | 1 | 0.053 | 3.40 | 0.0151 |

| AC | 1.125 × 10−4 | 1 | 1.125 × 10−4 | 7.238 × 10−3 | 0.0039 |

| BC | 0.050 | 1 | 0.050 | 3.19 | 0.0143 |

| A2 | 0.20 | 1 | 0.20 | 13.05 | 0.0048 |

| B2 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.14 | 8.78 | 0.0142 |

| C2 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.31 | 20.27 | 0.0011 |

| Residual | 0.16 | 10 | 0.016 | ||

| Lack of fit | 0.16 | 5 | 0.031 | 467.27 | <0.0001 |

| Pure error | 3.333 × 10−4 | 5 | 6.667 × 10−5 | ||

| Cor total | 1.27 | 19 |

R-Square = 0.9913; R-square adj = 0.9553; root mean square error = 1.4031.

Response surface curves of yield for l-Cysteine by the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase. (a) l-Serine and time, (b) l-serine and ultrasound power, and (c) time and ultrasound power.

Kinetics data for l-Cysteine bioconversion by the recombinant Escherichia coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase

| Operations | V max (mmol·h−1·(g-cells)−1 | K m (mM) |

|---|---|---|

| Shaking | 12.91 ± 0.34 | 1.342 ± 0.11 |

| Ultrasound (100 W) | 17.81 ± 0.24 | 1.843 ± 0.13 |

| Ultrasound (110 W) | 19.95 ± 0.16 | 2.041 ± 0.11 |

| Ultrasound (120 W) | 21.18 ± 0.31 | 2.202 ± 0.12 |

| Ultrasound (130 W) | 25.27 ± 0.16 | 2.555 ± 0.13 |

| Ultrasound (140 W) | 23.41 ± 0.12 | 2.435 ± 0.11 |

| Ultrasound (150 W) | 18.27 ± 0.18 | 1.855 ± 0.13 |

| Ultrasound (160 W) | 16.11 ± 0.16 | 1.655 ± 0.13 |

| Ultrasound (170 W) | 15.15 ± 0.11 | 1.584 ± 0.15 |

| Ultrasound (200 W) | 13.24 ± 0.51 | 1.334 ± 0.12 |

3.5 Preparation of l-cysteine

The reaction mixture (1 L) was centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 20 min to remove the bacterial cells. The supernatant was adjusted to pH 1.0 with 6 mol·L−1 hydrochloric acid. H2S was removed by heating. The reaction mixture was decolorized by activated carbon, and the filtrate was adjusted to pH 5.0 by NaOH (5 mol·L−1). l-Cysteine was oxidized through air in the filtrate and was washed with pure water. Then, the crude l-cystine was dried and decolorized by acid solution, crystallized, and washed. l-Cysteine was prepared by electrolytic reduction of l-cystine and dried to yield 14.26 g l-cysteine. The infrared spectrum of l-cysteine included the spectra of sulphydryl groups showing vibrational absorption (2,500–2,600 cm−1) (Figure 6b). The infrared spectrum of l-serine and l-cysteine included the spectra of amide groups showing vibrational absorption (1,500–1,800 cm−1) (Figure 6a and b).

FTIR spectra of (a) l-serine and (b) l-cysteine.

4 Conclusion

The effects of ultrasound treatment on the biosynthesis of l-cystine by a recombinant E. coli whole-cell system with tryptophan synthase were investigated for the first time. The optimal conditions obtained are 0.13 mol·L−1 l-serine, 75 min, and 130 W, where the V max of tryptophan synthase is 25.27 ± 0.16 (mmol·h−1·(g-cells)−1). The V max of tryptophan synthase for the biosynthesis without ultrasound is 12.91 ± 0.34 (mmol·h−1·(g-cells)−1). These results indicated that ultrasound treatment of the recombinant E. coli system with tryptophan synthase was useful for industrial l-cysteine biosynthesis.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Natural Science Research Project in Anhui Province (KJ2020A0729), the Project of Suzhou University (2018XJXS02, 2019XJSN05, 2019XJZY10), the Research Project in Suzhou University (2019ykf13, 2019YKF14), and the Cooperative Education Program of Ministry of Education (202002033001, 202002161034).

-

Author contributions: Lisheng Xu: writing-original draft; Furu Wu and Tingting Li: writing-review editing, methodology; Xingtao Zhang and Qiong Chen: formal analysis; Bianling Jiang: visualization; Qiuxia Xia: English corrections of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Kumar D, Subramanian K, Bisaria VS, Sreekrishnan TR, Gomes J. Effect of cysteine on methionine production by a regulatory mutant of Corynebacterium lilium. Bioresour Technol. 2005;96:287–94.10.1016/j.biortech.2004.04.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Kondoh M, Hirasawa T. l-Cysteine production by metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2019;103:2609–19.10.1007/s00253-019-09663-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Wen Z, Hu BC, Hu D, Liu YY, Zhang D, Zang J, et al. Efficient kinetic resolution of para-chlorostyrene oxide at elevated concentration by solanum lycopersicum epoxide hydrolase in the presence of Tween-20. Catal Commun. 2021;149:1–6.10.1016/j.catcom.2020.106180Search in Google Scholar

[4] Xue F, Liu ZQ, Wang YJ, Zhu HQ, Wan NW, Zheng YG. Efficient synthesis of (S)-epichlorohydrin in high yield by cascade biocatalysis with halohydrin dehalogenase and epoxide hydrolase mutants. Catal Commun. 2015;72:147–9.10.1016/j.catcom.2015.09.025Search in Google Scholar

[5] Takumi K, Ziyatdinov MK, Samsonov V, Nonaka G. Fermentative production of cysteine by Pantoea ananatis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:1–45.10.1128/AEM.02502-16Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Youn SH, Park HW, Shin CS. Enhanced dissolution of the substrate D,L-2-amino-Δ2-thiazoline-4-carboxylic acid and enzymatic production of l-Cysteine at high concentrations. Eng Life Sci. 2012;12:1–4.10.1002/elsc.201200002Search in Google Scholar

[7] Nakatani T, Ohtsu I, Nonaka G, Natthawut W, Morigasaki S, Takagi H. Enhancement of thioredoxin/glutaredoxin mediated l-Cysteine synthesis from S-sulfocysteine increases l-Cysteine production in Escherichia coli. Microbial Cell Factories. 2012;62:1–9.10.1186/1475-2859-11-62Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Duan JJ, Zhang Q, Zhao HZ, Du J, Bai F, Bai G. Cloning, expression, characterization and application of atcA, atcB and atcC from Pseudomonas sp. for the production of l-Cysteine. Biotechnol Lett. 2012;34:1101–6.10.1007/s10529-012-0878-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Joo YC, Hyeon JE, Han SO. Metabolic design of Corynebacterium glutamicum for production of l-Cysteine with consideration of sulfur-supplemented animal feed. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:4698–707.10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01061Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Kawano Y, Ohtsu I, Takumi K, Tamakoshi A, Nonaka G, Funahashi E, et al. Enhancement of l-Cysteine production by disruption of yciW in Escherichia coli. J Biosci Bioeng. 2015;119:176–9.10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.07.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Kawano Y, Onishi F, Shiroyama M, Miura M, Tanaka N, Oshiro S, et al. Improved fermentative l-Cysteine overproduction by enhancing a newly identified thiosulfate assimilation pathway in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:6879–89.10.1007/s00253-017-8420-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ma ML, Liu T, Wu HY, Yan FQ, Chen N, Xie XX. Enzymatic synthesis of l-Cysteine by Escherichia coli whole-cell biocatalyst. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering. 2018;444:469–78.10.1007/978-981-10-4801-2_48Search in Google Scholar

[13] Wei L, Wang H, Xu N, Zhou W, Ju JS, Liu J, et al. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for l-Cysteine production. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2019;103:1325–38.10.1007/s00253-018-9547-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Sperandio B, Polard P, Ehrlich DS, Renault P, Guédon E. Sulfur amino acid metabolism and its control in Lactococcus lactis IL1403. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3762–78.10.1128/JB.187.11.3762-3778.2005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Vermeji P, Kertesz MA. Pathways of assimilative sulfur metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5833–7.10.1128/JB.181.18.5833-5837.1999Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Wheeler PR, Coldham NG, Keating L, Gordon SV, Wooff EE, Parish T, et al. Functional demonstration of reverse transsulfuration in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex reveals that methionine is the preferred sulfur source for pathogenic Mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8069–78.10.1074/jbc.M412540200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Wada M, Awano N, Haisa K, Takagi H, Nakamori S. Purification, characterization and identification of cysteine desulfhydrase of Corynebacterium glutamicum, and its relationship to cysteine production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;217:103–7.10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11462.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Dai CH, Xiong F, He RH, Zhang WW, Ma HL. Effects of low-intensity ultrasound on the growth, cell membrane permeability and ethanol tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;36:191–7.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.11.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Zheng ZM, Huang QL, Luo XG, Xiao YD, Cai WF, Ma HY. Effects and mechanisms of ultrasound-and alkali-assisted enzymolysis on production of water-soluble yeast β-glucan. Bioresour Technol. 2019;273:394–403.10.1016/j.biortech.2018.11.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Sharma V, Nargotra P, Bajaj BK. Ultrasound and surfactant assisted ionic liquid pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse for enhancing saccharification using enzymes from an ionic liquid tolerant Aspergillus assiutensis VS34. Bioresour Technol. 2019;285:1–12.10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121319Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Yao LY, Zhu YX, Jiao RH, Lu YH, Tan RX. Enhanced production of fumigaclavine C by ultrasound stimulation in a two-stage culture of Aspergillus fumigatus CY018. Bioresour Technol. 2014;159:112–7.10.1016/j.biortech.2014.02.072Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Batghare AH, Singh N, Moholkar VS. Investigations in ultrasound-induced enhancement of astaxanthin production by wild strain Phaffia rhodozyma MTCC 7536. Bioresour Technol. 2018;254:166–73.10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.073Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Xu LS, Han FK, Dong Z, Wei ZJ. Engineering improves enzymatic synthesis of L-tryptophan by tryptophan synthase from Escherichia coli. Microorganisms. 2020;519(8):1–11.10.3390/microorganisms8040519Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Xu LS, Li TT, Huo ZY, Chen Q, Xia QX, Jiang BL. Directed evolution improves the enzymatic synthesis of L-5-hydroxytryptophan by an engineered tryptophan synthase. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;193:3407–17. 10.1007/s12010-021-03589-7 Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Chisti Y. Sonobioreactors: using ultrasound for enhanced microbial productivity. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:89–93.10.1016/S0167-7799(02)00033-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Liu R, Li W, Sun LY, Liu CZ. Improving root growth and cichoric acid derivatives production in hairy root culture of Echinacea purpurea by ultrasound treatment. Biochem Eng J. 2012;60:62–6.10.1016/j.bej.2011.10.001Search in Google Scholar

[27] Bar R. Ultrasound-enhanced bioprocesses: cholesterol oxidation by Rhodococcus erythropolis. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1988;32:655–63.10.1002/bit.260320510Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Francko DA, Al-Hamdani S, Joo GJ. Enhancement of nitrogen fixation in Anabaena flflos-aquae (Cyanobacteria) via low-dose ultrasonic treatment. J Appl Phycol. 1994;6:455–8.10.1007/BF02182398Search in Google Scholar

[29] Francko DA, Taylor SR, Thomas BJ, McIntosh D. Effect of low-dose ultrasonic treatment on physiological variables in Anabaena flos-aquae and Selenastrum capricornutum. Biotechnol Lett. 1990;12:219–24.10.1007/BF01026803Search in Google Scholar

[30] Pitt WG, Ross SA. Ultrasound increases the rate of bacterial cell growth. Biotechnol Prog. 2003;19:1038–44.10.1021/bp0340685Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Singh N, Roy K, Goyal A, Moholkar VS. Investigations in ultrasonic enhancement of β-carotene production by isolated microalgal strain Tetradesmus obliquus SGM19. Ultrason Sonochem. 2019;58:1–8.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104697Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Agarwal M, Dikshit PK, Bhasarkar JB, Borah AJ, Moholkar VS. Physical insight into ultrasound-assisted biodesulfurization using free and immobilized cells of Rhodococcus rhodochrous MTCC 3552. Chem Eng J. 2016;295:254–67.10.1016/j.cej.2016.03.042Search in Google Scholar

[33] Dikshit PK, Kharmawlong GJ, Moholkar VS. Investigations in sonication-induced intensifification of crude glycerol fermentation to dihydroxyacetone by free and immobilized Gluconobacter oxydans. Bioresour Technol. 2018;256:302–11.10.1016/j.biortech.2018.02.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Lisheng Xu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis