Abstract

The utilization of appropriate technology (AT) has become the Indonesian government strategy to increase productivity of agricultural commodities due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. However, the current utilization of AT remains suboptimal mostly due to design deficiencies that insufficiently account for human factors and user experience. In response, the aim of this study is to establish comprehensive AT design guidelines for sustainable AT utilization, focused on agricultural processing machines. An intensive observation was initially conducted in a rural community in Indonesia, to summarize difficulties faced by AT users. Supported by an exhaustive review of literature, a total of 44 human factors related design criteria were defined. Subsequently, these criteria underwent rigorous validation through a questionnaire administered to 197 respondents, consisting of AT designers, experts, and users. Employing the framework of principal component analysis (PCA), novel dimensions of AT design criteria were suggested, encompassing safety and error prevention, functionality and economics, user-friendly, low physical effort, physical workspace compatibility, and perceptible information. To augment the insights gleaned from the PCA, a matrix of importance-performance analysis was created, affording a map of the relative significance and concurrent performance of the defined criteria. The implications of this study are further discussed.

1 Introduction

The concept of appropriate technology (AT) was introduced around 1973 with the term of “Intermediate Technology” [1]. AT refers to simple and low-cost technology designed to address the needs of low-income communities in developing countries, particularly for small-scale utilizations, with the aim of increasing productivity and reducing the reliance on manual work [2]. AT emphasizes the utilization of local materials and resources, capitalizing on the inherent strength of the local context [3]. Often, AT solutions are developed based on the skills and capacities within a community. Bakker [4] extends the concept by defining any technology that positively impacts meeting basic human needs as falling under the category of AT.

The potential benefits of AT have been acknowledged by the Indonesian government. As an agrarian country, Indonesia relies heavily on the agricultural sector, which plays a pivotal role in its economy. This sector not only provides employment opportunities for nearly half of the population but also contributes to around one-fifth of gross domestic product and serves as a substantial source of exports [5]. Due to limited technological availability, the development of AT emerges as a national strategy. AT is expected to reduce operating cost of agricultural processing machines that currently still constitute 30–40% of the total production expenses [6]

Paradoxically, the utilization of AT remains modest in Indonesia. While the governments have introduced various AT machines, practical challenges have hindered their seamless integration into agricultural practices. Based on our observation, there are significant design challenges that need to be addressed. The prevalent design of agricultural AT often prioritizes economic cost–benefit analyses, assuming that users will maximize the utilization of ATs regardless of their design quality, as mentioned by Syuaib et al. [7]. AT designers seem to emphasize technical aspects while sometimes overlooking usability issues [8]. Other studies have identified other factors contributing to the low effectiveness of AT, including the absence of practical and gender-friendly design, socio-cultural barriers [9], high operational cost [10], and a failure to incorporate considerations of operational risks inherent in the machine design [11].

Meanwhile, certain investigations have embraced a human-centered approach in designing AT machines, such as grain thresher [12], maize dehusker-sheller [13], sickles [14], and cookstove [15]. However, despite these efforts, comprehensive reports detailing specific design guidelines that served as the foundation for AT designs are largely absent from the literature. There is a further need for recognizing the necessity of human factors and user experience as the key to successful AT implementation, including the concept of user-centered design, emphasizing user attributes [16] and usability [17,18,19].

In the realm of AT, discussions surrounding AT design criteria for agricultural product processing are relatively scarce. Indonesia’s diverse AT users necessitate design criteria that are ergonomic, secure, user-friendly, and tailored to the distinctive characteristics of indigenous users. An integration of the concepts of user-centered design, usability, and universal design can be applied as the initial model of AT design principles, providing a foundation for contextually-relevant AT design.

Previous researchers have attempted to formulate criteria for designing and evaluating AT and agriculture. One such researcher is Sianipar et al. [20], who presented factors that need to be considered in the design of AT, including technical, economic, environmental, and social considerations. Moses et al. [8] specifically developed evaluation criteria for cookstoves. These criteria place a focus on usability aspects, including fuel convenience, cooking performance, operability, maintenance, comfort, and location-specific requirements. Other criteria were proposed by Valizadeh and Hayati [21], emphasizing sustainability aspects, such as social equity and well-being, durability, stability and compatibility, and productivity and efficiency.

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a method used to reduce the dimensions of a dataset. The main idea behind PCA is to reduce the dimensionality of a dataset consisting of many interconnected variables while preserving as much variation as possible [22]. Valizadeh and Hayati [21] used PCA to develop and validate an agricultural sustainability measurement index in Iran, while Andati et al. [23] employed PCA alongside a multivariate probit regression model to investigate the factors influencing the adoption of climate-smart agriculture among small-scale potato farmers in Kenya.

This research endeavors to fill the existing problem by delineating a comprehensive framework of AT design criteria that align seamlessly with the socio-cultural fabric, user experience, and the practical realities of the agricultural landscape in Indonesia. Through the synthesis of human factors and user experience, this study seeks to set forth a pioneering path toward increasing utilization of AT in the agricultural sector.

2 Methodology

This research is structured into three distinct stages: an evaluation of the current utilization of AT, the formulation of design principles, and the evaluation of AT design criteria. In the initial phase of the study, a preliminary examination was conducted to delineate the existing characteristics of AT machines in Indonesia and appraise their level of utilization. This preliminary study entailed field observations, a data collection methodology involving direct observation of on-site situations or events.

The second stage entails the formulation of design principles, tailored to the unique context of AT within Indonesia. PCA method serves as the basis of this developmental phase. Progressing to the third stage, the evaluation of AT design criteria is analyzed employing the robust methodology of Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA). By dissecting the dimensions of importance and performance, the IPA approach aids in identifying the optimal strategies for fostering substantial improvements in AT utilization.

2.1 Research development on AT

An intensive literature study was conducted on the Scopus database using the following keywords: AT, agricultural processing machine design, and ergonomics. The obtained documents were analyzed using VOSviewer software. As shown in Figure 1, there are five clusters, which include: (1) AT, product design, and ergonomic design; (2) humans, risk factors, and body posture; (3) musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), risk assessment, and occupational risks; (4) ergonomics; and (5) anthropometry. It is clear that ergonomic-related issues are relevant to the design of AT.

Keywords mapping on bibliometrics.

2.2 Field observation

The process of observation was executed through a combination of direct field observations and insightful interviews with users of AT machines, particularly those related to agricultural product processing. The focal point of these observations was a farming community located in Subang, West Java, Indonesia. In particular, the investigation centered around four distinct small-medium enterprises (SMEs), the profiles of which are meticulously outlined in Table 1.

Profile of SME respondents

| SME name | Year of establishment | Number of employees | Production capacity | Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enos | 2013 | 4 people | 15 kg dodol/day | Red beans dodol |

| Aitamie | 2018 | 2 people | 10 kg noodles/day | Corn flour noodles, corn flour chips |

| Mekar Sari | 1997 | 10 people | 200 kg pineapples/day | Pineapple dodol, pineapple crackers, pineapple wajit, pineapple jam, mushroom |

| Alam Sari | 1997 | 25 people | 20 tons pineapples/month | Pineapple dodol, pineapple crackers, pineapple chocolate, pineapple syrup, pineapple juice, mushroom |

2.3 Development of design criteria

The criteria for AT design consist of a set of principles for human–machine interaction that can serve as a guide in designing AT machines that have positive effects on usability, acceptability, and utility, leading to enhanced user productivity. Various concepts related to product design were comprehensively used, including user-centered design, universal design, safety, and usability. The initial factors in this study were identified based on the literature reviewed during the primary model-building stage. The initial factors are determined by combining and selecting reference model variables relevant to the AT problem.

The results of the previous literature study, which involved the establishment of the initial research factors, were then followed by the identification of model indicators. A total of 105 design indicators have been documented. Ultimately, after verification through field observations and interviews with 4 SMEs, a total of 44 design indicators were selected. Numerous AT design guideline indicators were gathered from previous articles [8,16,17,18,19,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

2.4 Questionnaire

This study utilized a questionnaire as a measurement tool to acquire the necessary data, supplementing the results of direct observations, to ascertain the relevance of design principles to the AT conditions in Indonesia. The initially prepared questionnaire underwent a pilot test with several respondents. The questionnaire encompassed 44 questions (based on the 44 design criteria) aimed at gauging user expectations and perceptions regarding AT design. Each factor was assessed using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, with assistance provided to participants as needed.

The collected questionnaire data underwent validity and reliability tests. The validity test employed a correlation analysis by comparing the calculated r-value against the total-Pearson correlation at a 95% confidence level, demonstrating the validity of all research indicators. The reliability test yielded a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.968 (above 0.60), affirming the reliability of all indicators.

Factor analysis was utilized to establish the dimensions of AT design, using the PCA method to recognize patterns within multidimensional data. The application of PCA is expected to result in new criteria for the dimensions of the design guideline. Subsequently, these new dimensions were incorporated into an IPA matrix. The IPA matrix serves as an evaluative tool to pinpoint attributes necessitating enhancement and corrective measures, and was used to determine the priority of improvements based on machine design indicators in order to increase users’ satisfaction. AT user satisfaction can be measured by comparing the performance of AT equipment expected by users compared to the actual performance of AT equipment in the field.

2.5 Respondents

A total of 197 respondents participated in the study, including AT operators, designers, SMEs, and farmers. The respondents were selected through purposive sampling from several regions in Indonesia, although the majority (81.09%) resided in West Java due to the rapid development of AT in that region. There were 89 male and 91 female respondents, with respondents aged between 36 and 45 years making up around 32.2% of all respondents and about 9.44% of respondents aged over 55 years. Most respondents had a college education background (Diploma-Postgraduate), around 69.44%, and only one was an elementary school graduate. When the survey was conducted, around 35.29% of respondents had used AT for 1–5 years, and around 20.00% had used AT for over 10 years. Table 2 shows the demographic data of the respondents.

Respondents’ demography profiles

| Criteria | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 97 | 49.24 |

| Female | 100 | 50.76 | |

| Age | 16–25 years | 68 | 34.52 |

| 26–35 years | 30 | 15.23 | |

| 36–45 years | 58 | 29.44 | |

| 46–55 years | 24 | 12.18 | |

| >55 years | 17 | 8.63 | |

| Education | Primary school | 1 | 0.51 |

| Juniors high school | 3 | 1.52 | |

| High school | 69 | 35.03 | |

| Diploma | 23 | 11.68 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 44 | 22.34 | |

| Postgraduate | 57 | 28.93 | |

| Use of AT | 0–1 year | 75 | 38.07 |

| 1–5 years | 60 | 30.46 | |

| 5–10 years | 28 | 14.72 | |

| >10 years | 33 | 16.75 |

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Summary of observation result

The outcomes of interviews and field observations conducted with AT users are outlined below.

3.1.1 Enos

In 2017, Enos received AT machines, including a coconut grater, peanut grinder, and dodol mixer (Figure 2), which almost doubled their production capacity. The machines are generally easy to use but cannot be repaired or modified if they are damaged. The design problems found include the short size/height of the coconut grater, which requires users to bend over, and the unprotected edges of the coconut grater that can cause hand injuries. Additionally, the inlet hole of the peanut grinder is too small, making it impractical.

Various AT machines at Enos.

3.1.2 Aitamie

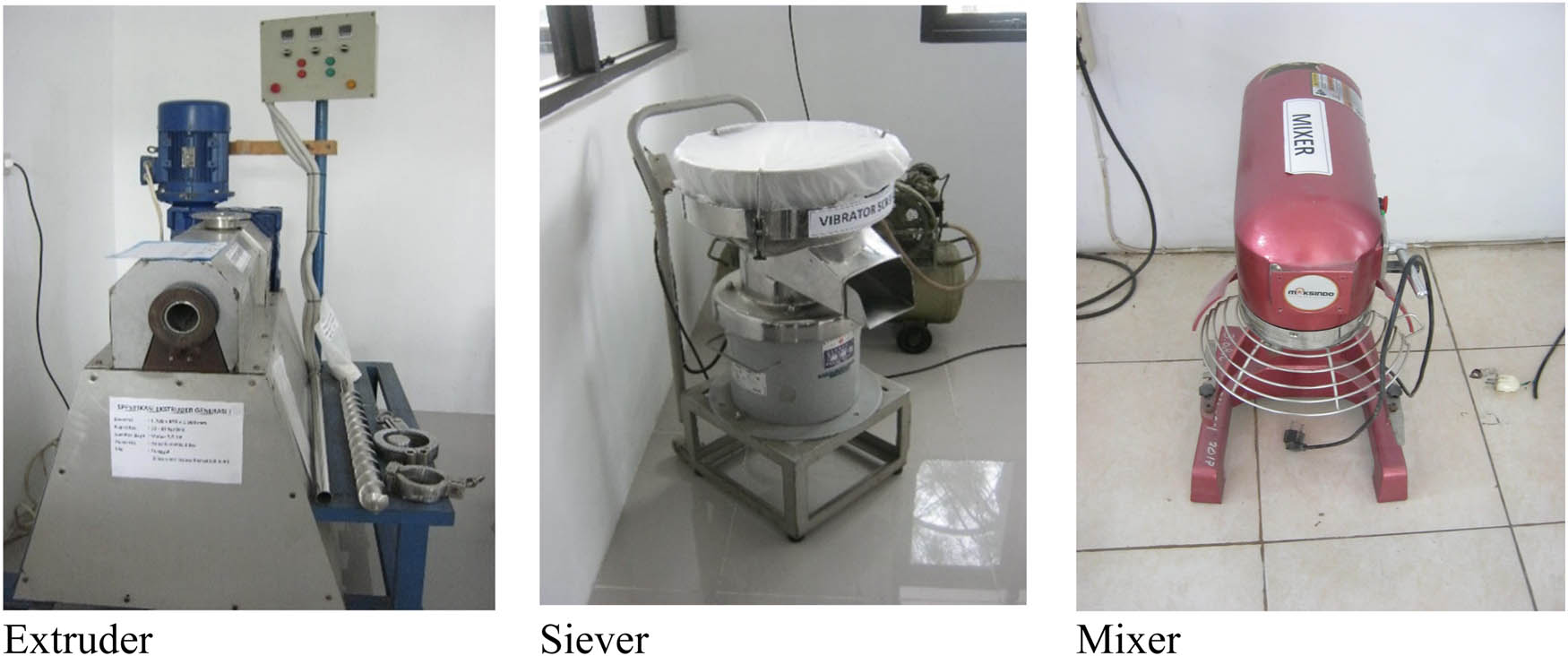

Aitamie, established in 2018, produces non-wheat noodles and pasta using AT machines, some of which are shown in Figure 3. The owners reported that the AT machines have benefits in maintaining production quality, but some machines require physical exertion and are uncomfortable, especially for women. Minor accidents have occurred, such as hands getting caught in the machines. Specific complaints were also mentioned, such as the lack of temperature control on the extruder, which results in easily cracked noodle products. The tool must be disassembled when cleaning, which is inconvenient, and the extruder intake hole is too high anthropometrically, requiring a ladder. Furthermore, the electric power consumption of the extruder is still too high, increasing production costs.

Various AT machines at Aitamie.

3.1.3 Mekar Sari

Mekar Sari has been utilizing AT machines for pineapple processing since 2019. It is worth noting that Subang is known for its pineapples. The owner is satisfied with the use of the AT machines (Figure 4), which have increased production capacity by around 50%. However, several machines are still semi-manual, and problems have arisen with their use, including complaints related to musculoskeletal pain, difficulties in repairing the machines, and the lack of safety measures. In addition, they have reported that using gas fuel for the dodol mixer is not cost-effective compared to traditional wood stoves since the temperature is not optimal, and the process takes longer.

Various AT machines at Mekar Sari.

3.1.4 Alam Sari

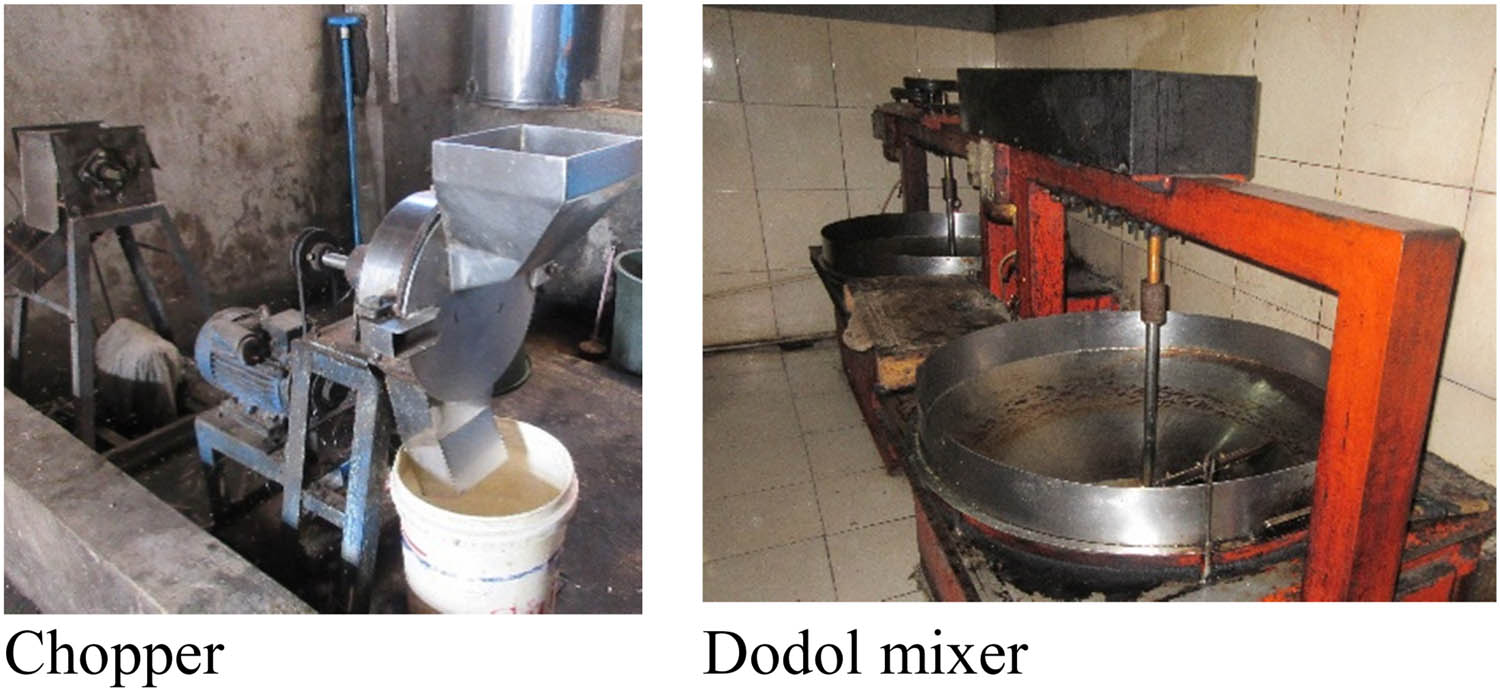

Alam Sari has been using AT machines for pineapple processing since 2005. The AT machines owned by Alam Sari include a chopper, dodol mixer, slicer, coconut grater, packer, extractor, mixing tank, cooking tank, and pulper (Figure 5). The owners have received benefits from using AT machines, including faster production times, larger production capacity, and cheaper production costs. In general, AT machines are easy to use, except for several tools that require special skills, such as automatic packaging tools. However, they have also revealed several design problems, such as:

Chopper (a tool for making pineapple pulp). The machine is often exposed by the pineapple pulp resulting in easy machine damage.

Dodol mixer does not have dispensing system. After completion of mixing process, users have to dissemble the machine and it seems to be a hassle for women.

Alam Sari has received assistance from the government with a set of machines such as cold storage and cooking tanks. However, the machines are no longer used since their capacities are too big and high electric power is required (10,000 W).

Several processes are still conducted manually such as using a knife to peel and cut pineapples. With a production capacity of around 500–600 kg of pineapples per day, the manual process takes a lot of time and effort.

Various AT machines at Alam Sari.

Based on field observations, some existing problems in using AT machines can be summarized as follows:

Functionality: Functionality refers to the ability of a machine to meet basic requirements and function properly [33]. Our observations showed that most AT machines function acceptably, but some require improvements in design to enhance performance, shorten processing time, and increase productivity.

Physical workload: The most common problem with current AT machine design is the lack of ergonomic aspects. The disproportionate height of machines requires workers to bend down every time they put in raw materials and take out processed products, leading to physical fatigue and the risk of musculoskeletal injury. Improving the design to be compatible with users’ needs can increase effectiveness, productivity, and prevent health problems [34].

Energy use: Users often complain about the cost of energy use during the cooking process. For example, the cooking time using a gas-fueled mixer was longer than that using a wood stove due to less optimal fire processes. Some AT machines still use diesel engines, which are less environmental-friendly and more expensive compared to electricity. Fuel type and heater design have been shown to affect fuel cost and cooking time in previous studies [35].

Safety and errors: The use of agricultural machinery has been reported to cause traumatic injury incidents to users, indicating that safety is often ignored in designing AT machines [12]. In case of errors, the handling procedure should have a clear standard operating or emergency procedure.

Maintenance and repairs: The existing design makes cleaning, maintaining, and repairing AT machines difficult. Therefore, machines must be easily disassembled to ease the cleaning process. The repair process of some AT machines can only be done by a technician, but the availability of repair workshops is limited, especially in rural areas.

User convenience: Ease of use of AT machines varied from very easy to rather difficult. Simple and manual machines are generally easier to use because users can apply them directly without learning or training. Ease of use is a key factor in using technology, as it is closely related to the usability of a product or design [33].

Dimension: The size of AT machines is also an important issue raised by SMEs. In rural areas, simple, light, and easy-to-move machines that require a small space to operate are very helpful. Developing a design with mobility advantages is one of the most effective, economical, and efficient solutions that can enhance the immediate post-harvest process.

3.2 Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics questionnaire measurement results are shown in Table 3. The design indicators in Table 3 were obtained from the combined results of literature studies and field observations. The literature study yielded 105 design criteria. After verification with the results of initial observations and interviews, 41 criteria were selected that were relevant to the conditions, use, and problems of AT in the field. Results showed that safe to use and environmental-friendly had the highest mean values (4.5 ± 0.63 and 4.5 ± 0.62, respectively) and usable by various groups had the lowest mean value (4.0 ± 0.86) (Table 3).

Min., max., mean values, and standard deviation (SD)

| Items | Min. value | Max. value | Mean value | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Consideration of socio-cultural factors of the local community | 3 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.67 |

| X2 | Usable by various groups | 1 | 5 | 4.0 | 0.86 |

| X3 | Understandable by various groups | 1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.71 |

| X4 | Ability to choose to use | 2 | 5 | 4.1 | 0.74 |

| X5 | Simple to use | 2 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.68 |

| X6 | Easy to set-up | 3 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.60 |

| X7 | Comfortable to use | 3 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.64 |

| X8 | Minimizes mental effort | 1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.74 |

| X9 | Easy to use | 3 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.61 |

| X10 | Grouped buttons and indicators for easy use | 3 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.63 |

| X11 | Provides a manual guide | 1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.73 |

| X12 | Manual guide available in different forms | 1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.70 |

| X13 | Important information is easy to be understood | 1 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.67 |

| X14 | Important information is easy to read and is clear | 1 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.65 |

| X15 | Has a cancellation feature | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.86 |

| X16 | Emergency controls can be identified | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.79 |

| X17 | Dangerous parts are protected | 2 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.76 |

| X18 | Has warnings of potential hazards | 1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.82 |

| X19 | Has prevent-errors features | 1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.78 |

| X20 | Has a safety and security guide | 1 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.80 |

| X21 | Does not cause pain or injury in the hands or feet | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.76 |

| X22 | Minimizes physical effort | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.73 |

| X23 | Long-term use without causing fatigue | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.79 |

| X24 | Long-term use without causing pain | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.84 |

| X25 | Long-term use without requiring a long rest period | 1 | 5 | 4.1 | 0.81 |

| X26 | Accessibility of all parts | 2 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.66 |

| X27 | Matching the user’s body size | 2 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.74 |

| X28 | Matching various characteristics of the user’s body | 2 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.73 |

| X29 | Can be operated in a comfortable standing or sitting position | 1 | 5 | 4.1 | 0.77 |

| X30 | Usable by users with a variety of hand sizes and palm grips | 2 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.64 |

| X31 | Safe to use | 3 | 5 | 4.5 | 0.63 |

| X32 | Environmentally friendly | 3 | 5 | 4.5 | 0.62 |

| X33 | Noise level below the threshold | 2 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.75 |

| X34 | Meets applicable standards | 1 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.74 |

| X35 | Has long enough durability | 2 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.69 |

| X36 | Affordable price | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.80 |

| X37 | Easy to maintain | 2 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.68 |

| X38 | Uses good quality materials | 2 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.66 |

| X39 | Attractive design | 2 | 5 | 4.1 | 0.80 |

| X40 | Simple construction | 2 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.75 |

| X41 | Easy to clean | 2 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.65 |

| X42 | Easy to repair | 2 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.68 |

| X43 | Has a modular design | 1 | 5 | 4.2 | 0.77 |

| X44 | Efficient energy use | 2 | 5 | 4.3 | 0.64 |

3.3 Results of factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the data using PCA with factor extraction and VARIMAX rotation. The questionnaire data underwent significance testing using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the sampling adequacy test using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test. The results of the tests indicate that the significance level is less than 0.05 (Sig. = 0.000), and the variables used can proceed to the next process. The KMO test also yielded a value of 0.927, indicating that the factor analysis process is feasible (Table 4).

KMO and Bartlett’s test

| KMO measure of sampling adequacy | 0.927 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approx. chi-square | 6676.560 |

| df | 946 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

The results of the factor analysis show that, based on the users’ opinions, six factors affect the optimum design of AT. The factor loadings, communalities, variance explained and eigen values are presented in Table 5. The six factors resulting from the interrelationships of each indicator are safety and error prevention, functionality and economics, user-friendliness, low physical effort, physical workspace compatibility, and perceptible information.

Factor analysis results (factor loadings > 0.4)

| Factor | Items | Factor loading | Communalities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety and error prevention | X15 | Has a cancellation feature | 0.607 | 0.714 |

| X16 | Emergency control can be identified | 0.713 | 0.772 | |

| X17 | Dangerous parts are protected | 0.755 | 0.763 | |

| X18 | Has warnings of potential hazards | 0.773 | 0.786 | |

| X19 | Has prevent-errors features | 0.714 | 0.655 | |

| X20 | Has a safety and security guide | 0.784 | 0.785 | |

| X31 | Safe to use | 0.516 | 0.674 | |

| X32 | Environmentally friendly | 0.567 | 0.690 | |

| X34 | Meets applicable standards | 0.661 | 0.669 | |

| Functionality and economics | X35 | Has long enough durability | 0.662 | 0.654 |

| X36 | Affordable price | 0.698 | 0.657 | |

| X37 | Easy to maintain | 0.701 | 0.731 | |

| X38 | Uses good quality materials | 0.636 | 0.642 | |

| X39 | Attractive design | 0.599 | 0.647 | |

| X40 | Simple construction | 0.472 | 0.662 | |

| X41 | Easy to clean | 0.573 | 0.721 | |

| X42 | Easy to repair | 0.671 | 0.730 | |

| X43 | Has a modular design | 0.689 | 0.642 | |

| X44 | Efficient energy use | 0.662 | 0.685 | |

| User-friendly | X5 | Simple use | 0.754 | 0.677 |

| X6 | Easy to set-up | 0.687 | 0.699 | |

| X7 | Comfortable to use | 0.567 | 0.637 | |

| X8 | Minimizes mental effort | 0.438 | 0.583 | |

| X9 | Easy to use | 0.710 | 0.699 | |

| X10 | Grouped buttons and indicators for easy use | 0.684 | 0.697 | |

| Physical workspace compatibility | X27 | Matching the user’s body size | 0.699 | 0.651 |

| X28 | Matching various characteristics of the user’s body | 0.791 | 0.769 | |

| X29 | Can be operated in a comfortable standing or sitting position | 0.695 | 0.753 | |

| X30 | Usable by users with a variety of hand sizes and palm grips | 0.754 | 0.715 | |

| Low physical effort | X21 | Does not cause pain or injury in the hands or feet | 0.790 | 0.815 |

| X22 | Minimizes physical effort | 0.634 | 0.665 | |

| X23 | Long-term use without causing fatigue | 0.679 | 0.726 | |

| X24 | Long-term use without causing pain | 0.684 | 0.732 | |

| X25 | Long-term use without requiring a long rest period | 0.694 | 0.700 | |

| X26 | Accessibility of all parts | 0.403 | 0.683 | |

| Perceptible information | X2 | Usable by various groups | 0.566 | 0.505 |

| X11 | Provides a manual guide | 0.668 | 0.714 | |

| X12 | Manual guide available in different forms | 0.704 | 0.795 | |

| X13 | Important information is easy to be understood | 0.557 | 0.651 | |

| X14 | Important information is easy to read and is clear | 0.685 | 0.748 | |

The percentage of variance shows that the first to sixth factors have variances ranging from 7.55 to 14.52% (Table 6). The cumulative variance of all the formed factors is 62.34% (>50%). The validity test and the reliability of each PCA showed that all factors were valid and reliable (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.6).

Extracted factors and their eigenvalue, percentage of eigenvalue’s variance, cumulative percentage, and Cronbach’s alpha

| Factors | Eigenvalue | Percentage of eigenvalue’s variance | Cumulative percentage | Cronbach’s alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1. | Safety and error prevention | 6.389 | 14.52 | 14.52 | 0.936 |

| F2. | Functionality and economics | 5.609 | 12.75 | 27.27 | 0.92 |

| F3. | User-friendly | 4.129 | 9.38 | 36.65 | 0.863 |

| F4. | Physical workspace compatibility | 4.018 | 9.13 | 45.78 | 0.88 |

| F5 | Low physical effort | 3.962 | 9.01 | 54.79 | 0.895 |

| F6. | Perceptible information | 3.322 | 7.55 | 62.34 | 0.853 |

The first factor is safety and error prevention. The safety and error prevention factor had 14.52% of total variance. This factor had the most significant effect. Based on the first factor, safety and error prevention, it is assumed that the AT design can minimize the dangers and negative consequences of accidents and unintentional actions. It should also provide warnings for potential hazards and errors, features that do not allow failure or safety even though they cannot work and prevent actions that are carried out unconsciously [17]. The design also needs to consider the safety and risks posed by AT machines.

The second factor is functionality and economics. This factor had 12.75% of total variance. According to the functionality and economic factor, someone will adopt technology when there is technical and physical support [36]. Currently, most AT machines are commercially oriented and mass-produced. Therefore, the economic and cost factors of AT machine will be important by considering the purchasing power of users in Indonesia and the functionality of the products. The design also allows the use of a modular system which makes it easy to move, clean, assemble, maintain, repair, and be adapted to the working environment conditions. AT machine is expected to use quality materials and energy sources that are cheap and available on site. The economic factors for AT machine are influenced by investment and operating costs, including energy and maintenance needs. Verma & Sinha [37] discovered that economic factors affect the acceptance of technology by farmers.

The third factor is user-friendly. This factor had 9.38% of total variance. The AT design needs to be practical, easy to understand, and easy to use. It is also necessary to consider local social conditions, culture, customs, perceptions, and behaviors for easy acceptance, adoption, use, and learning by people with various demographic backgrounds. According to Sonderegger and Sauer [38], socio-cultural background affects the usability assessment of a product. AT machines will be used by a great diverse of Indonesians who are socially and culturally different; therefore, developers need to consider these peculiarities when designing the machine.

The fourth factor is physical workspace compatibility. This factor had 9.13% of total variance. Based on the fourth factor, the AT design must accommodate various individual preferences and capabilities. This principle accommodates various circumstances and individual abilities to provide choices in the method of using a product, options for right or left-hand access, variations in hand sizes and grip sizes, and facilities for proper use.

The fifth factor is low physical effort. This factor had 9.01% of total variance. An AT design must be used efficiently and comfortably with a minimum physical fatigue, which allows users to maintain a neutral body position, use a reasonable mode of device operation, minimize repetitive actions, and reduce continuous physical effort. Based on our ergonomics assessment on the risk of MSDs of operating an AT machine, namely, the extruder, using the REBA method showed that the risk level is high. When operating the extruder, the farmers have to bend their body due to the extremely low position of the dough intake hole and product output. This could lead to complaints on the neck, shoulders, back, waist, and arms [39].

The sixth factor is perceptible information. This factor had 7.55% of total variance. The AT design needs to have a manual (manual book) on how to use the machine for easy understanding by various users to minimize errors and confusion. Therefore, the machine that is made must have the ability to effectively communicate the required information to the user without considering the surrounding conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. Information contained on AT machine can be in writing or non-verbal graphic symbols form. Non-verbal symbols are considered more effective than writing because they can easily be remembered and quickly communicate concepts and instructions. They also avoid problems due to impaired reading skills (children, elderly, and illiterate) or different languages [40].

The proposed six design principles have accommodated safety, functionality, economic value, physical workload, and user-friendly. Similar factors have been proposed by Beecher and Paquet [24]. Lin and Wu [27] mentioned aspects of functionality, social, commercial, and aesthetic. Our previous study has also included adaptability as additional factor [41]. The results of this research differ slightly from those of a study by Kuijt-Evers et al. [42], which identified six factors to consider in the design of hand tools: functionality, posture and muscles, pain in hand/finger, hand surface, handle characteristics, and aesthetics. These six factors primarily focus on user comfort. Some similarities with the results of this research include the factors of functionality. The results of this study are also different from those of Vaccari et al. [43], who formulated specific criteria for cooking technology for rural communities, namely, financial, health-related, environmental, and social in sub-Saharan Africa.

A design can be evaluated through four variables, namely, functional, usability, emotional, and aesthetic aspects [44]. Functionality entails meeting the fundamental design requirements, while usability pertains to the ease of use or operation. Aesthetics relates to the appearance of the product, while emotion encompasses the emotional benefits of a product in people’s interactions. According to PCA results, these variables are integrated into the design factors. Functionality and aesthetics are linked to the second factor (functionality and economics). Usability and emotion are correlated with the third factor (user-friendly). The first factor (safety and error prevention) pertains to safety. The fourth, fifth, and sixth factors (physical workspace compatibility, low physical effort, and perceptible information) are associated with comfort, cognitive aspects, and the human factor.

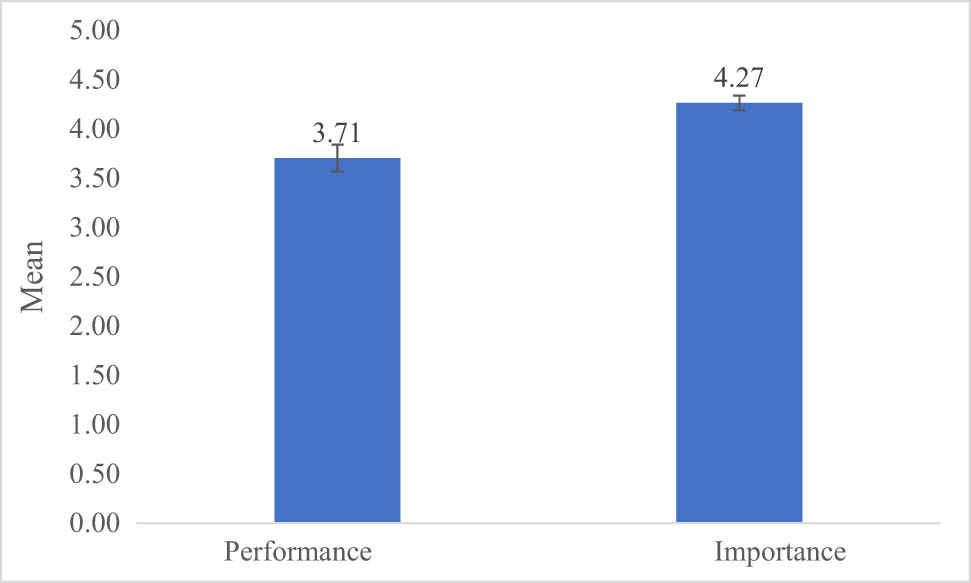

3.4 Results of IPA

The results of the analysis of 197 respondents showed that the average values for the importance and performance of the AT machine are 4.3 ± 0.08 and 3.7 ± 0.14, respectively. According to the perception of users, there is still a gap between the performance and importance of the AT machine (Figure 6).

Mean value of importance and performance of the existing AT machines.

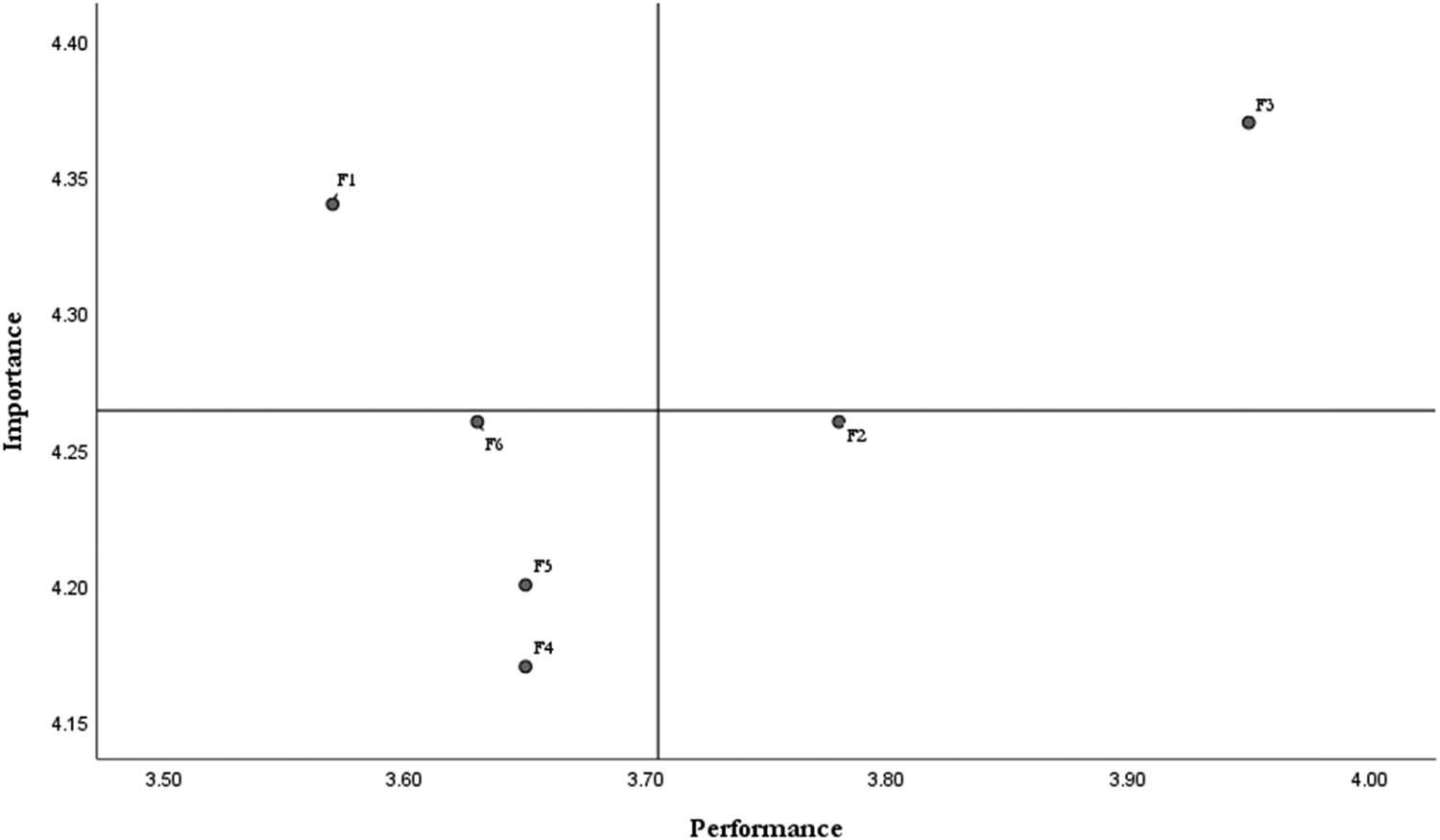

The measurement results of the perceived and expected use of AT machines are presented in an IPA, as shown in Figure 7, where each number indicates a factor code. In quadrant A, the users rate the AT design factor as very important but show low satisfaction. The AT design factors in quadrant B are rated as important and were satisfied with the existing performance. In quadrant C, the users are not satisfied with the existing performance and do not consider these factors important. The AT users in quadrant D are satisfied with the given performance but rate these factors as less important.

Importance-performance matrix.

Based on the outcomes of the IPA matrix, priority improvements for the design of AT machines should concentrate on one factor within quadrant A which is safety and error prevention. These attributes can be subdivided into two aspects. The first aspect involves the significance of AT machines with easily understandable usage guidelines and safety instructions. The second aspect pertains to the security of AT machines. Currently, many AT machines used in Indonesia lack manuals, primarily due to being manufactured by small to medium-scale workshops. Providing such guidelines aims to enable users to optimize machine functions and features, minimizing misuse and the risk of accidents.

Another significant priority for enhancing AT design pertains to machine safety. The AT machines were originally designed as simple manual machines to assist human labor, but several features and functions have been added later due to technological advancements and various needs. Not all AT machines in the community are equipped with security and safety features for users. Ensuring safety features is crucial for ongoing development and the application of active and passive safety features in the design of AT machines, both in the present and future.

In quadrant B, AT users assess crucial AT design indicators and express satisfaction with the provided performance, warranting maintenance. Indicators in this quadrant are regarded as important and are expected to bolster user contentment. This quadrant is deemed highly significant and gratifying. The design factors encompassed in quadrant B pertain to user-friendliness. Respondents find the AT machine relatively easy to operate, thereby emphasizing the need for its maintenance.

4 Conclusion

Design is one of the factors that must be considered in product development, including AT, to make it more ergonomic and effective. This research represents an initial step in the literature regarding design criteria for AT. Based on the factor analysis method, a total of 6 factors were produced with 41 design criteria. The results of the IPA matrix show that improvements to AT machines need to be prioritized in two aspects, including safety and user guide. For practitioners and designers, these results can assist in determining the design orientation of agricultural processing machines, taking into account human factors in addition to technical aspects, to enhance their effectiveness, especially for farmers and business actors. These results can also be of value to the industry, with the potential to enhance the competitiveness of agricultural product processing machines. Additionally, the research outcomes offer valuable insights to the government for the selection of agricultural processing machines to be disseminated to the public, thereby increasing their acceptance and sustainable utilization of AT. The research results have also been instrumental in developing a questionnaire for assessing and evaluating AT designs. Nevertheless, this research is subject to certain limitations as the sample of respondents is limited to Indonesian people. Future research could also explore methods for objectively evaluating the design of agricultural AT machines using experimental methods.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia.

-

Author contributions: T.R. contributed in designing research model, data collection, data analysis and wrote the paper. Y. and A.W. contributed in conceptualization, supervision, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Schumacher EF. Small is Beautiful. London: Blond & Briggs; 1973.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kaplinsky R. Schumacher meets schumpeter: Appropriate technology below the radar. Res Policy. 2011 Mar;40(2):193–203.10.1016/j.respol.2010.10.003Search in Google Scholar

[3] Tharakan J. Indigenous knowledge systems - a rich appropriate technology resource. Afr J Sci Technol Innov Dev. 2015;7(1):52–7.10.1080/20421338.2014.987987Search in Google Scholar

[4] Bakker H. The Gandhian approach to Swadeshi or appropriate technology: A conceptualization in terms of basic needs and equity*. J Agric Ethics. 1990;3(1):50–88.10.1007/BF02014480Search in Google Scholar

[5] Syuaib MF. Sustainable agriculture in Indonesia: Facts and challenges to keep growing in harmony with environment. Agric Eng Int CIGR J. 2016;18(2):170–84, http://www.cigrjournal.org.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zaynagabdinov R, Gabitov I, Bakiev I, Gafurov I, Kostarev K. Optimum planning use of equipment in agriculture. J Ind Eng Manag. 2020;13(3):514–28.10.3926/jiem.3185Search in Google Scholar

[7] Syuaib F, Moriizumi S, Shimizu H. Ergonomic study on the process of mastering tractor operations rotary tillage operation using walking type tractor. J Jpn Soc Agric Mach. 2002;64(4):61–7.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Moses ND, Pakravan MH, MacCarty NA. Development of a practical evaluation for cookstove usability. Energy Sustain Dev. 2019 Feb;48:154–63.10.1016/j.esd.2018.12.003Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kalungu JW, Leal, Filho W. Adoption of appropriate technologies among smallholder farmers in Kenya. Clim Dev. 2018 Jan;10(1):84–96.10.1080/17565529.2016.1182889Search in Google Scholar

[10] Mottaleb KA. Perception and adoption of a new agricultural technology: Evidence from a developing country. Technol Soc. 2018 Nov;55:126–35.10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.07.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Luo L, Qin L, Wang Y, Wang Q. Environmentally-friendly agricultural practices and their acceptance by smallholder farmers in China – A case study in Xinxiang County, Henan Province. Sci Total Environ. 2016 Nov;571:737–43.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.07.045Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Kumar A, Mohan D, Patel R, Varghese M. Development of grain threshers based on ergonomic design criteria. Appl Ergon. 2002;33:503–8.10.1016/S0003-6870(02)00029-7Search in Google Scholar

[13] Singh SP, Singh S, Singh P. Ergonomics in developing hand operated maize Dehusker-Sheller for farm women. Appl Ergon. 2012;43(4):792–8.10.1016/j.apergo.2011.11.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Singh SP. Physiological workload of farm women while evaluating sickles for paddy harvesting. Agric Eng Int CIGR J. 2012;14(1):82–7, http://www.cigrjournal.org.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Vaccari M, Vitali F, Mazzù A. Improved cookstove as an appropriate technology for the Logone Valley (Chad - Cameroon): Analysis of fuel and cost savings. Renew Energy. 2012 Nov;47:45–54.10.1016/j.renene.2012.04.008Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zhang F, Yang M, Liu W. Using integrated quality function deployment and theory of innovation problem solving approach for ergonomic product design. Comput Ind Eng. 2014;76(1):60–74.10.1016/j.cie.2014.07.019Search in Google Scholar

[17] Nielsen J. Enhancing the Explanatory of Usability Heuristic. In: Proceeding of Conference on Human Factors in Computing System. Boston: Massachusetts; 1994. p. 152–8.10.1145/259963.260333Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jou M, Tennyson RD, Wang J, Huang SY. A study on the usability of E-books and APP in engineering courses: A case study on mechanical drawing. Comput Educ. 2016 Jan;92–93:181–93.10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.004Search in Google Scholar

[19] François M, Crave P, Osiurak F, Fort A, Navarro J. Digital, analogue, or redundant speedometers for truck driving: Impact on visual distraction, efficiency and usability. Appl Ergon. 2017 Nov;65:12–22.10.1016/j.apergo.2017.05.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Sianipar CPM, Yudoko G, Dowaki K, Adhiutama A. Design methodology for appropriate technology: Engineering as if people mattered. Sustainability (Switz). 2013;5(8):3382–425.10.3390/su5083382Search in Google Scholar

[21] Valizadeh N, Hayati D. Development and validation of an index to measure agricultural sustainability. J Clean Prod. 2021;280:1–22.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123797Search in Google Scholar

[22] Jolliffe IT. Principal Component Analysis. 2nd edn. New York: Springer; 2002. p. 1–487.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Andati P, Majiwa E, Ngigi M, Mbeche R, Ateka J. Determinants of adoption of climate smart agricultural technologies among potato farmers in Kenya: Does entrepreneurial orientation play a role? Sustain Technol Entrep. 2022;1(2):1–11. 10.1016/j.stae.2022.100017Search in Google Scholar

[24] Beecher V, Paquet V. Survey instrument for the universal design of consumer products. Appl Ergon. 2005;36(3):363–72.10.1016/j.apergo.2004.10.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Lenker JA, Nasarwanji M, Paquet V, Feathers D. A tool for rapid assessment of product usability and universal design: Development and preliminary psychometric testing. Work. 2011;39(2):141–50.10.3233/WOR-2011-1160Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Plos O, Buisine S, Aoussat A, Mantelet F, Dumas C. A Universalist strategy for the design of Assistive Technology. Int J Ind Ergon. 2012 Nov;42(6):533–41.10.1016/j.ergon.2012.09.003Search in Google Scholar

[27] Lin KC, Wu CF. Practicing universal design to actual hand tool design process. Appl Ergon. 2015 Sep;50:8–18.10.1016/j.apergo.2014.12.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Story MF. Maximizing Usability: The principles of universal design. Assist Technol. 1998 Jun;10(1):4–12.10.1080/10400435.1998.10131955Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Huang PH, Chiu MC. Integrating user centered design, universal design and goal, operation, method and selection rules to improve the usability of DAISY player for persons with visual impairments. Appl Ergon. 2016 Jan;52:29–42.10.1016/j.apergo.2015.06.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Dixon J, Gullo LJ. Design for human factors integrated with system safety. In: Gullo LJ, Dixon J, editors. Design for Safety. 1st edn. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2018.10.1002/9781118974339Search in Google Scholar

[31] Yu J, Lee H, Ha I, Zo H. User acceptance of media tablets: An empirical examination of perceived value. Telemat Inform. 2017 Jul;34(4):206–23.10.1016/j.tele.2015.11.004Search in Google Scholar

[32] Maldonado A, García JL, Alvarado A, Balderrama CO. A hierarchical fuzzy axiomatic design methodology for ergonomic compatibility evaluation of advanced manufacturing technology. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2013 Apr;66(1–4):171–86.10.1007/s00170-012-4316-8Search in Google Scholar

[33] Singh R, Tandon P. User values based evaluation model to assess product universality. Int J Ind Ergon. 2016 Sep;55:46–59.10.1016/j.ergon.2016.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[34] Jafry T, O’neill DH. The application of ergonomics in rural development: a review. Appl Ergon. 2000;31:263–8.10.1016/S0003-6870(99)00051-4Search in Google Scholar

[35] Hanifah U, Andrianto M. Experimental study on fuel consumption and energy efficiency at soymilk cooking using a mini boiler and using a gas stove. In: 4th International Conference on Science and Technology. Yogyakarta: IEEE; 2018.10.1109/ICSTC.2018.8528681Search in Google Scholar

[36] Irjayanti M, Azis AM. Barrier factors and potential solutions for Indonesian SMEs. Procedia Econ Financ. 2012;4:3–12.10.1016/S2212-5671(12)00315-2Search in Google Scholar

[37] Verma P, Sinha N. Integrating perceived economic wellbeing to technology acceptance model: The case of mobile based agricultural extension service. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2018 Jan;126:207–16.10.1016/j.techfore.2017.08.013Search in Google Scholar

[38] Sonderegger A, Sauer J. The influence of socio-cultural background and product value in usability testing. Appl Ergon. 2013;44(3):341–9.10.1016/j.apergo.2012.09.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Indriati A, Mayasti NKI, Rahman T, Litaay C, Anggara CEW, Astro HM, et al. Risk analysis of Musculoskeletal Disorder (MSDs) on corn noodles production. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. London: IOP Publishing Ltd; 2022.10.1088/1755-1315/980/1/012048Search in Google Scholar

[40] Lesch MF. Comprehension and memory for warning symbols: Age-related differences and impact of training. J Saf Res. 2003;34(5):495–505.10.1016/j.jsr.2003.05.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Rahman T, Widyanti A, Yassierli. The development of universal design principles for appropriate technology in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). J Phys: Conf Ser. 2021;1858:012017.10.1088/1742-6596/1858/1/012017Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kuijt-Evers LFM, Groenesteijn L, De Looze MP, Vink P. Identifying factors of comfort in using hand tools. Appl Ergon. 2004;35(5):453–8.10.1016/j.apergo.2004.04.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Vaccari M, Vitali F, Tudor T. Multi-criteria assessment of the appropriateness of a cooking technology: A case study of the Logone Valley. Energy Policy. 2017;109:66–75.10.1016/j.enpol.2017.06.052Search in Google Scholar

[44] Kurosu M. Usability and culture as two of the value criteria for evaluating the artifact – a new perspective from the artifact development analysis (ADA). In: Katre D, Orngreen R, Yammiyavar P, Clemmensen T, editors. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. Pune, India: Springer; 2010. p. 67–75.10.1007/978-3-642-11762-6_6Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan

- Agronomic performance, seed chemical composition, and bioactive components of selected Indonesian soybean genotypes (Glycine max [L.] Merr.)

- The role of halal requirements, health-environmental factors, and domestic interest in food miles of apple fruit

- Subsidized fertilizer management in the rice production centers of South Sulawesi, Indonesia: Bridging the gap between policy and practice

- Factors affecting consumers’ loyalty and purchase decisions on honey products: An emerging market perspective

- Inclusive rice seed business: Performance and sustainability

- Design guidelines for sustainable utilization of agricultural appropriate technology: Enhancing human factors and user experience

- Effect of integrate water shortage and soil conditioners on water productivity, growth, and yield of Red Globe grapevines grown in sandy soil

- Synergic effect of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and potassium fertilizer improves biomass-related characteristics of cocoa seedlings to enhance their drought resilience and field survival

- Control measure of sweet potato weevil (Cylas formicarius Fab.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in endemic land of entisol type using mulch and entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana

- In vitro and in silico study for plant growth promotion potential of indigenous Ochrobactrum ciceri and Bacillus australimaris

- Effects of repeated replanting on yield, dry matter, starch, and protein content in different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes

- Review Articles

- Nutritional and chemical composition of black velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd) and its influence on animal production: A review

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum Lam) as a natural feed additive and source of beneficial nutrients and phytochemicals in chicken nutrition

- The long-crowing chickens in Indonesia: A review

- A transformative poultry feed system: The impact of insects as an alternative and transformative poultry-based diet in sub-Saharan Africa

- Short Communication

- Profiling of carbonyl compounds in fresh cabbage with chemometric analysis for the development of freshness assessment method

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part I

- Non-destructive evaluation of soluble solid content in fruits with various skin thicknesses using visible–shortwave near-infrared spectroscopy

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part I

- Traditional agri-food products and sustainability – A fruitful relationship for the development of rural areas in Portugal

- Consumers’ attitudes toward refrigerated ready-to-eat meat and dairy foods

- Breakfast habits and knowledge: Study involving participants from Brazil and Portugal

- Food determinants and motivation factors impact on consumer behavior in Lebanon

- Comparison of three wine routes’ realities in Central Portugal

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- Environmentally friendly bioameliorant to increase soil fertility and rice (Oryza sativa) production

- Enhancing the ability of rice to adapt and grow under saline stress using selected halotolerant rhizobacterial nitrogen fixer