Abstract

The need for sheet metal forming using highly resistant materials such as titanium alloys and stainless steel has increased recently. These materials possess elevated mean flow stress values, which make them difficult to draw at room temperature. To achieve a homogeneous distribution of strain in the stretched component, reduce the load required for plastic deformation, and greatly improve material formability, hot forming is helpful. The goal of the current study is to conduct stretch-forming experiments to investigate the forming characteristics of Austenitic material Stainless Steel (ASS) 304 at Hot working temperatures. Stretch forming experiments have been conducted on the Servo electrical sheet press test machine at 650 and 800°C. The formability has been estimated by constructing a Fracture forming diagram (FFLD), limiting the height of the dome (LDH) and the distribution of the strain of stretched cups. It has been discovered that the limit of forming bounds rises with the temperature reaching 800°C, while the DSA effect causes the necking region – the area between the safe and fracture limits ‒ to decrease with additional temperature rise from 800 to 900°C. Within the experimental limitations, it has been considered that the Hot forming of ASS 304 at 650°C gives the highest strain forming limits with a uniform strain distribution in the stretched cups. From the Formability limit diagram, dome height, and strain distribution, it can be observed that ASS 304 has good limiting strain up to 800°C with lower load application.

1 Introduction

The most popular iron‒chromium‒nickel steels are the austenitic grades, also referred to as the 300 series. Because of their high concentration of chromium and nickel, austenitic stainless steels are the most resistant to corrosion of all stainless steels; they can even tolerate boiling seawater [1,2,3,4]. Even at lower temperatures, the austenitic alloy structure is incredibly resilient and ductile, and it maintains its strength even at high working temperatures. ASS 304 in particular is employed in the nuclear sector for radiation and structural containment due to its unique features [5,6,7,8]. One potential processing method to increase the ability to form alloys and metals is hot forming [9,10,11]. Improving the material flow and reducing the spring-back effect are the objectives of hot metal forming methods. While the process of hot forming (T > 0.5 Tm) reduces the yield stress and permits concurrent recrystallization thereby affecting the size of the grain’s improvement as well as the mechanical behavior of the material, cold working (T < 0.3 Tm) uses strain hardening to improve a material’s strength at the expense of higher forming forces [12,13,14]. Warm forming (0.3 Tm < T < 0.7 Tm) is employed as the intermediate step, which permits recovery but prevents recrystallization, to prevent large forces from friction and spring back. Making the most of the benefits that come with warm and cold forming is the goal of hot forming. The characteristics, precision, and movement of the substance during deformation are all impacted by the forming temperature.

Because the material’s yield flow stress is lower in hot forming than in cold forming, less force is needed, placing more strain on the forming equipment and tools. From a different angle, it is possible to attain higher part precision in terms of shape, size, and surface quality. There is always a trade-off when determining the ideal temperature for a certain hot forming procedure and formed material. Force, which can be generated by the forming arrangement and the material’s formability, determines its lower limit. Usually, the maximum is established by the maximum quantity of oxidation that may be endured [15,16,17].

One of two processes ‒ slip or twinning, the more prevalent of the two ‒ causes plastic deformation in metals. Dislocations are what cause slippage, and their mobility is a major factor in how easily deformation can occur. An applied tension is needed to overcome lattice friction as the dislocations travel across the lattice. The dislocations can overcome these strains with the help of thermal energy [18]. Temperature has a weak effect on Peierls-Nabarro stresses, which are the primary barrier in BCC metals; nevertheless, temperature has a considerable effect on FCC metals, such as aluminum and ASS. Room temperature deformation occurs through twinning on certain planes and slips on the basal planes; at hot working temperatures, twinning is less significant, and slip occurs in most of the planes. Plastic deformation happens considerably more readily at hot working temperatures [19].

Because the strain-hardening ability of these materials reduces at hot working temperatures, hot forming increases the formability of aluminum alloys [20]. The ferrous materials’ drawability at high working temperatures has demonstrated that an aluminum alloy sheet’s formability can be significantly increased by hot forming. More recently, Bandhu et al. [21,22,23] investigated non-isothermal cylindrical cup stretching forming at various temperature gradients and found that raising the temperature in certain areas of the sheet can enhance the formability of an Al–Mg alloy sheet.

Investigating the intricate interplay between mechanical and thermal impacts on formability is a problem for process designers in hot forming. Magnesium alloy non-isothermal stretch forming is investigated experimentally and verified by FE analysis [9]. The study determined the ideal process parameters and showed that factors such as forming temperature, lubricant, and sheet thickness all significantly affect the limiting drawing ratio. Combined thermo-mechanical finite element analysis for aluminum rectangular cup formation at high operating temperatures [24]. They determined component depth values at several die-punch temperature pairings and blank holder pressures, and they used thickness variations as a failure criterion. The findings implied that limiting strain increases with increasing forming temperature. Additionally, a greater temperature differential across the die and punch boosted the material’s formability.

In order to create a dependent-on-temperature anisotropy material framework for finite element modeling and its formability simulation, two automobile alloys of aluminum, AA5182-O, and AA5754-O, were hot-formed [25]. The model was effectively employed for the coupled thermo-mechanical finite element analysis pertaining to the hot shaping of aluminum products. The deformation behavior and failure position in the blank were precisely predicted by FE analysis using the established thermo-mechanical constitutive model, and the results compared well to the experimental findings for both materials. To effectively describe the Hot Forming process, they demonstrated the significance of utilizing both thermal investigation and a precise anisotropic temperature-dependent material model.

In the plastic regime, metal sheets exhibit anisotropic behavior, and at high operating temperatures, they exhibit temperature dependence on their strain rate sensitivity. It is anticipated that anisotropy changes very little during the formation process. Isotropic hardening and anisotropic yield functions are utilized under this supposition. There are certain restrictions to this method. Because of the existence of material anisotropy, characteristics of its plane-stress assumption that are ignored in isotropic analyses can have a significant impact on the computation’s accuracy and findings [26].

Characterizing the anisotropy nature of sheet metal has been the subject of numerous investigations. Elastoviscoplastic models based on microstructure can be created with cast aluminum alloys [27]. For anisotropic materials, a non-quadratic deformation criterion is presented, which is based on the Kelvin breakdown of the elasticity vector [28,29]. incorporated an anisotropic model into a finite element analysis that was implicit [30]. The impact of plastic anisotropy on the quasi-static loading characteristics of a rolling aluminum plate is investigated [31]. They discovered that a high-strength aluminum alloy’s notable anisotropic behavior may be adequately described by the anisotropy yield function [18,32,33]. The earring is the result of combining the yield stress directionalities and R-value contributions [19,34,35]. They demonstrated a novel analytical method that forecasts the profile of the earring and confirmed the outcomes for three distinct aluminum alloys. Using strain rate and temperature-dependent hardening principles, the hot-forming simulation of anisotropic elastoplastic hardening materials has been explored recently [36,37]. MIG and TIG welding processes are among the most common methods used to join dissimilar AISI 1040 and AISI 8620 cylindrical steel joints [41]. A slurry-pot wear tester to investigate the relationship between slurry concentration and slurry-erosion performance of DSS 2507/IN625 dissimilar weld joint (DWJ) [42,43]. Based on the literature review, ASS 304 has good formability in stretch drawing, but it needs higher forces and high-capacity presses to deform the metal sheet into the required shape. Under heated conditions, the forces can be reduced, and low-capacity presses can be used for deformation. This scope has motivated me to mainly focus on the formability of ASS 304 at hot working temperatures in stretch forming setup. No such related work is carried throughout the literature. Most of the work is only concentrated on tensile testing to 650°C and formability with deep drawing setup up to 250°C where it requires a large tonnage forming machine setup with very low formability. It also concerns the effect of DSA on the formability of ASS 304 in stretch forming, particularly on FLD, Limiting dome height (LDH), and strain distribution of the stretched cups. The above parameters indicate the importance of analyzing the problem, and efforts are made to improve the formability so that complex parts of nuclear, aerospace, and automotive applications can be produced in one setup [38–40].

Researchers are responsible for finding and establishing new methods to meet the demands of production and quality of manufacturers. In recent years, hot forming has been gaining more importance and attaining promising results in industrial applications. These issues motivate in applying such paradigms for analyzing and improving the formability of ASS 304 for enhancing the production of complex sheet metal components.

2 Materials and methods

The chemical composition of as-received ASS 304 sheets is listed in Table 1. The spectrometric analysis has been carried out at Jyothi Spectro Labs, Hyderabad.

Chemical composition of as-received ASS 304sheets

| Element | Fe | Cr | Ni | Mo | Si | Mn | Cu | Co | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition (wt%) | 67.69 | 6.6 | 0.8 | 2.42 | 1.28 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.018 |

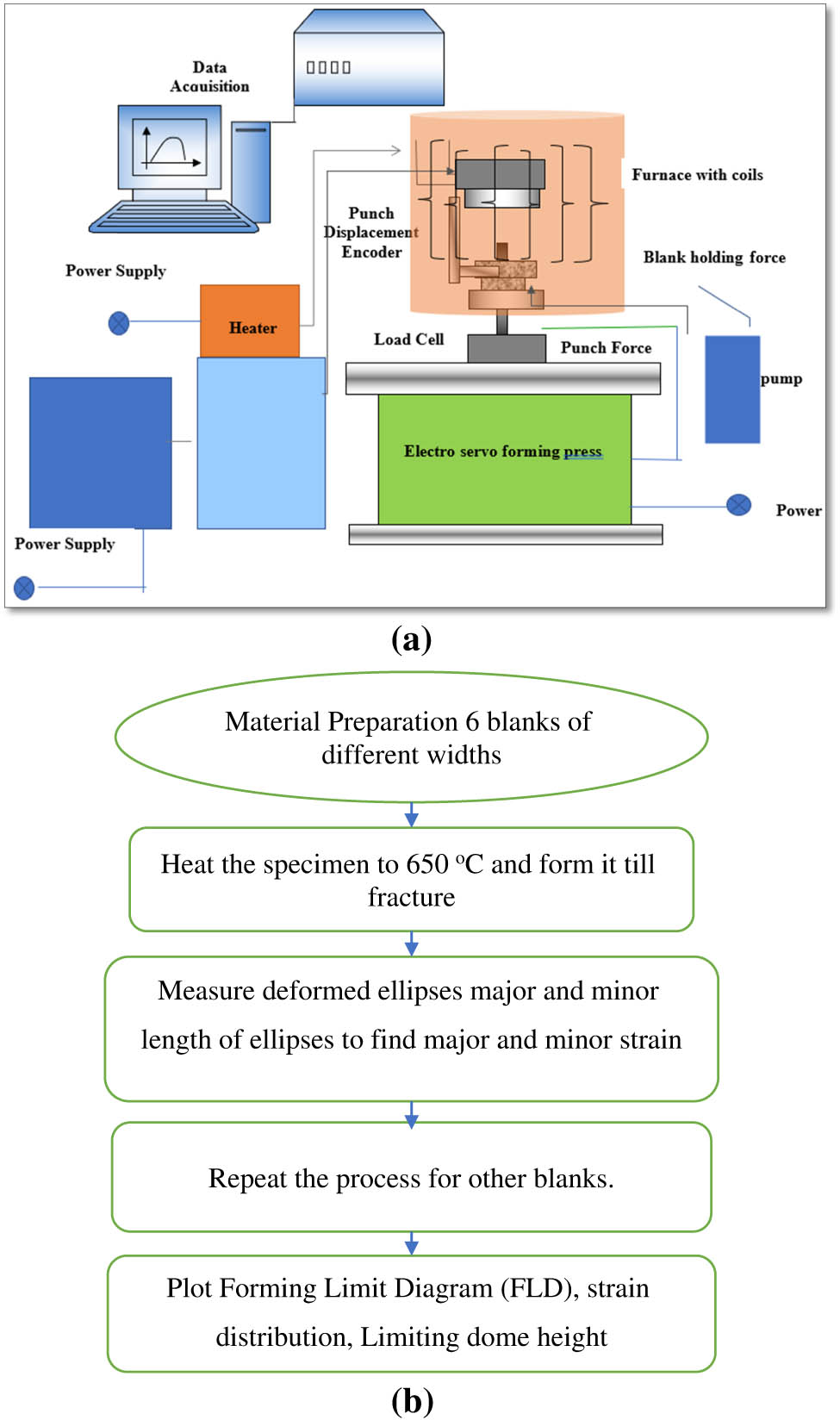

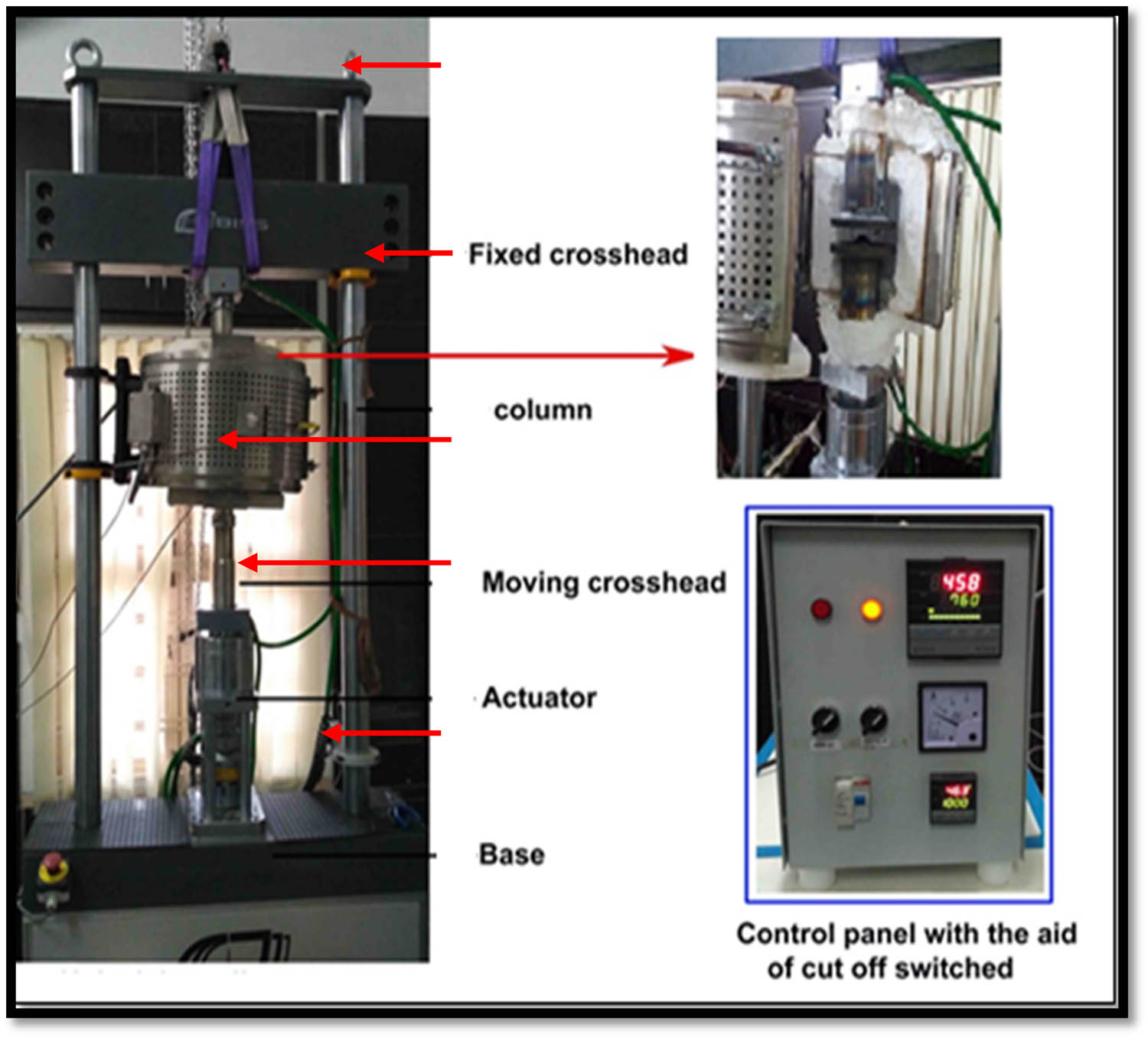

Stretch-forming procedures at high working temperatures are intended to be performed in the experimental setting. The major purpose of the experimental setup is to determine the effectiveness of hot stretch forming over a range of temperatures, which is achieved by assessing the formability at different Hot working temperatures. The schematic of the experimental setup for Hot stretch forming (Figure 1). consists of one furnace installed on a five-tonne Servo Electro press for heating both the die and blank as shown in Figure 2. Die heating is required to avoid thermal shocks on the heated-up blank. The temperatures are recorded with the help of a digital indicator on the heater which is connected to the furnace. The idea behind this is to measure the wavelength of radiation that the substance emits. Punch travel, load, and pressure are obtained by the press from a data-gathering system that is attached to it. These are entered into the computer, which immediately plots the results, such as the change in load against position and force. After lubricating the blank and positioning it on the lower die, the upper die is lowered to tighten the bolts on the upper head, fixing the blank in place. Once both the die and sheet were heated to the necessary temperature, an automatic controlled temperature cut-off switch was activated, which kept the setup temperature where the forming process was being carried out constant. Molykote has been employed as a lubricant to lessen friction between the punch assembly, die, and blank. It has a base material made of molybdenum, which works quite well at high temperatures. After heating the blank and positioning it atop the hot die, the punch was activated, and the stretching process was carried out. A cutoff switch in the heater’s control panel allowed the setup temperature to be managed and overheated to be avoided [41–43].

(a) Schematic of the experimental setup for Hot stretch forming; (b) flow chart representing the methodology of the hot forming process of the work.

Hot forming set up with Inconel Stretching dies in the closet.

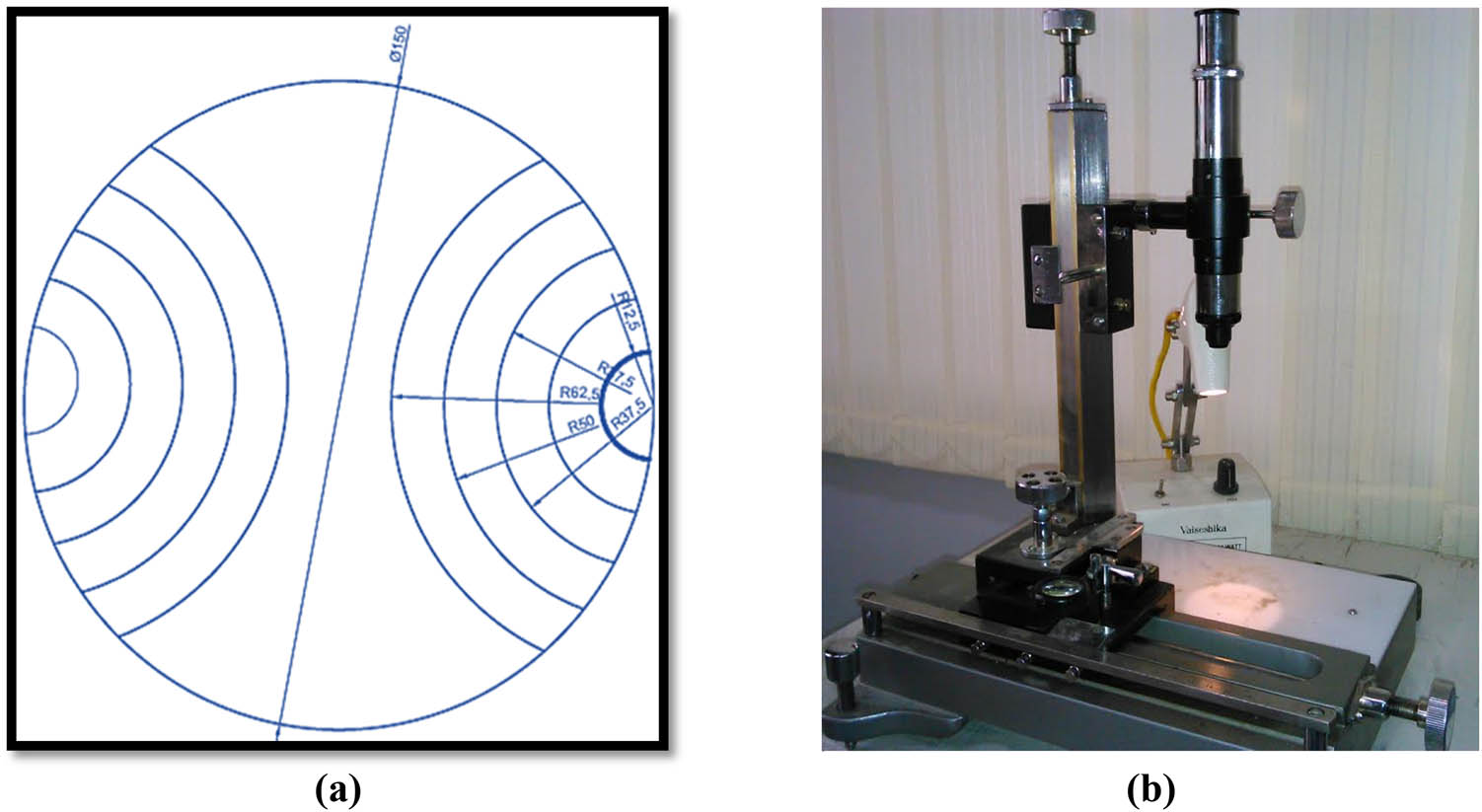

Due to the furnace capacity, the experimental setup has a limitation on the temperature to which the die and blank can be heated up. Dies can reach up to a maximum of 800°C. Therefore, the hot stretch forming experiments have been performed at 650 and 800°C on the Nakajima specimens shown in Figure 3 in mm of 1 thickness at variant diameters with increments of 150 × 25 mm to 150 mm diameter onward. At 600 and 800°C, experiments are conducted at two strain rates 10−2 s−1 and 10−3 s−1 irrespective of the orientation of the rolling direction is represented by a flow chart in Figure 1(b).

(a) Nakazima geometry of ASS304; (b) traveling microscope to measure deformed ellipses on the blanks after forming.

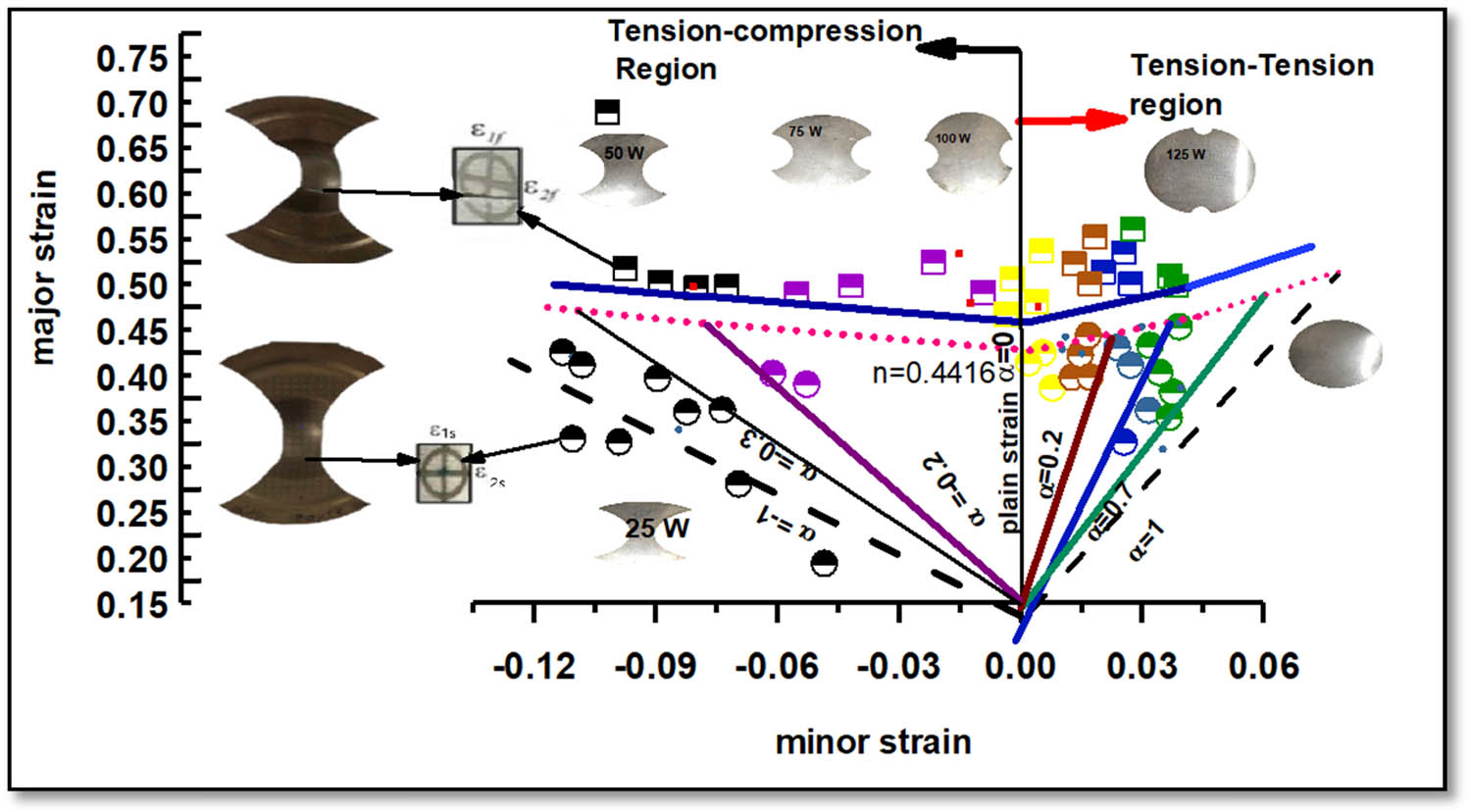

The experimental FLC curves were plotted after conducting hemispherical dome tests on different width specimens made of ASS 304 as shown in Figures 4 and 5. Experiments are conducted by placing the sheet specimens in such a way that circular etched marks prior to deformation are below the sheet. A series of blanks of different widths are deformed to a hemispherical dome until fracture. After forming these domes, etching marks are stretched at the outside of the dome and circles become ellipses of different sizes based on the deformation conditions. Dimensions of etched grids are measured near to the fracture and major and minor strains are calculated. The axes of the ellipse formed on the domes are measured to find relative strain in two primary directions, known as the major and minor, which correspond to the major and minor axes of the ellipse measured using a traveling microscope as shown in Figure 2(b). Various sheets have been stretched from Nakazima blank sizes of different widths at the hot working temperatures, and FLD has been evaluated experimentally by plotting values from the deformed ellipses etched on the specimens. A line is drawn covering all the points measured from safe, necking, and fracture ellipses indicating safe, necking, and fractured curves. This curve is indicated with the help of strain upper limit indicated by n, the higher the value of n higher the formability limits. For LDH measurement, a Vernier height gauge of least counts 0.02 mm is used to measure the dome height from the reference surface of the necked specimen cups. Analyzing a secure blank dimension at a warm working temperature that may be stretched without breaking is made possible by the research of strain distribution. Strain distribution is plotted by plotting distance vs major strain and minor strain of the deformed ellipses, which shows the uniform distribution of sheet thickness during forming.

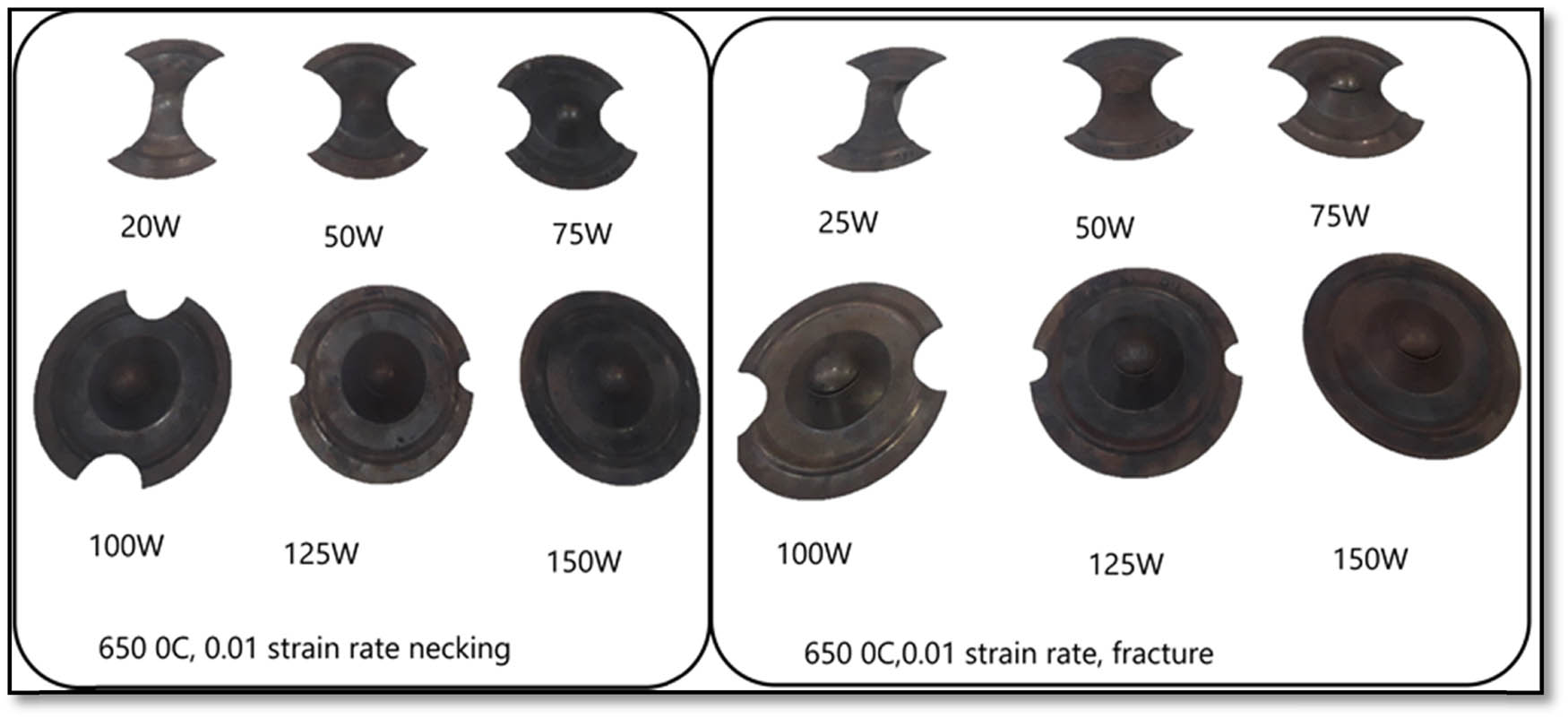

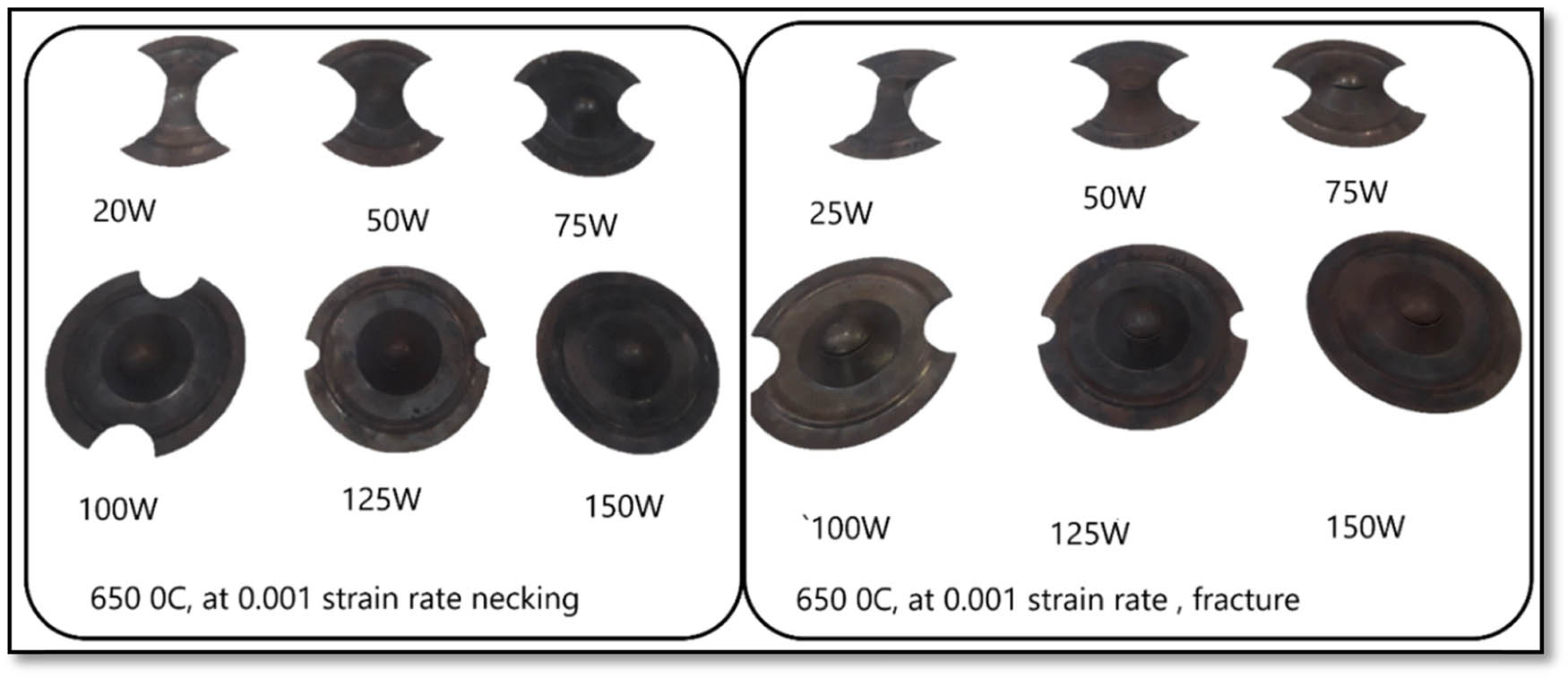

Experimentally stretched cups at 650°C from different size blanks at 0.01 s−1.

Experimentally stretched cups at 650°C from different size blanks at 0.001 s−1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Hot stretch forming at 650°C

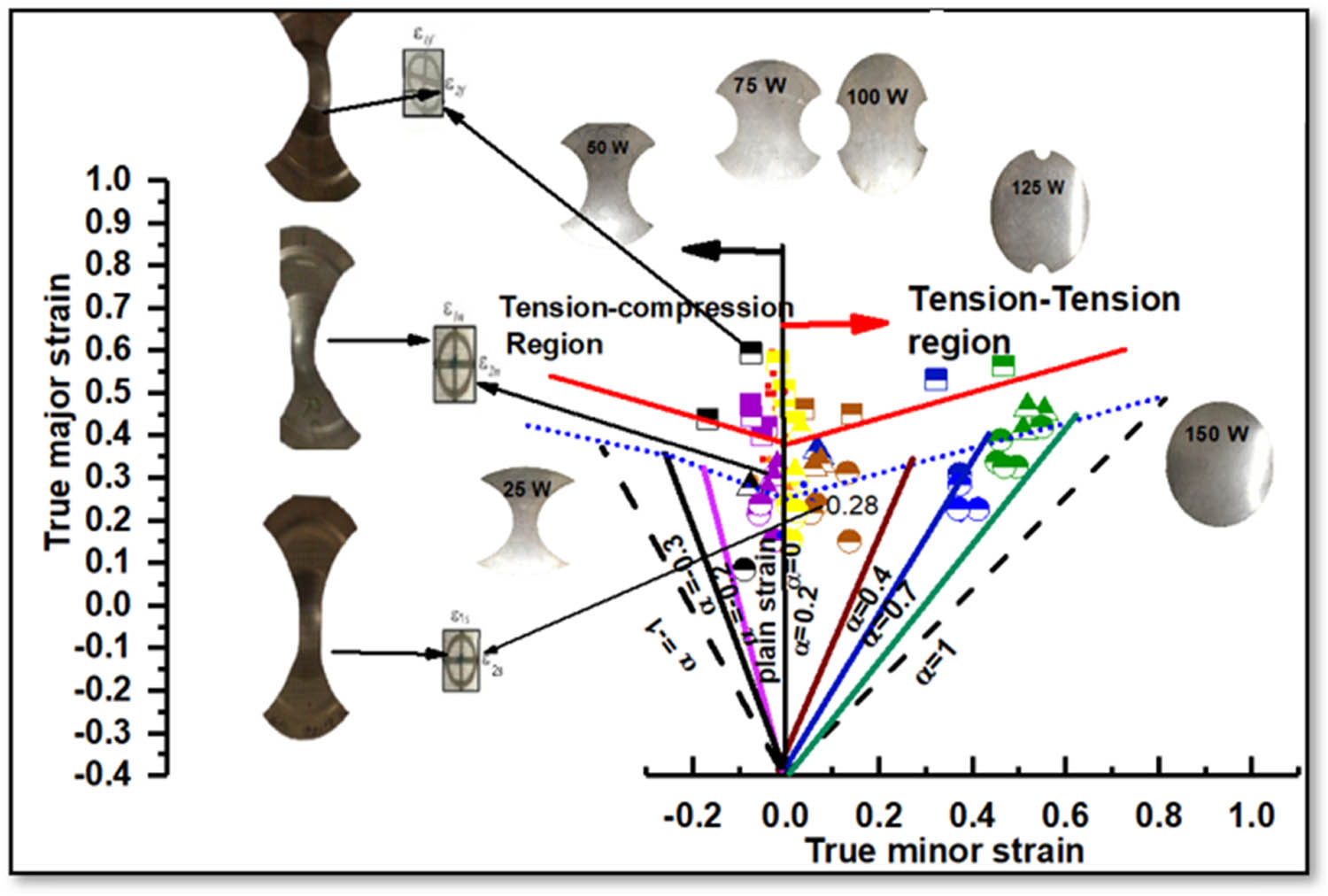

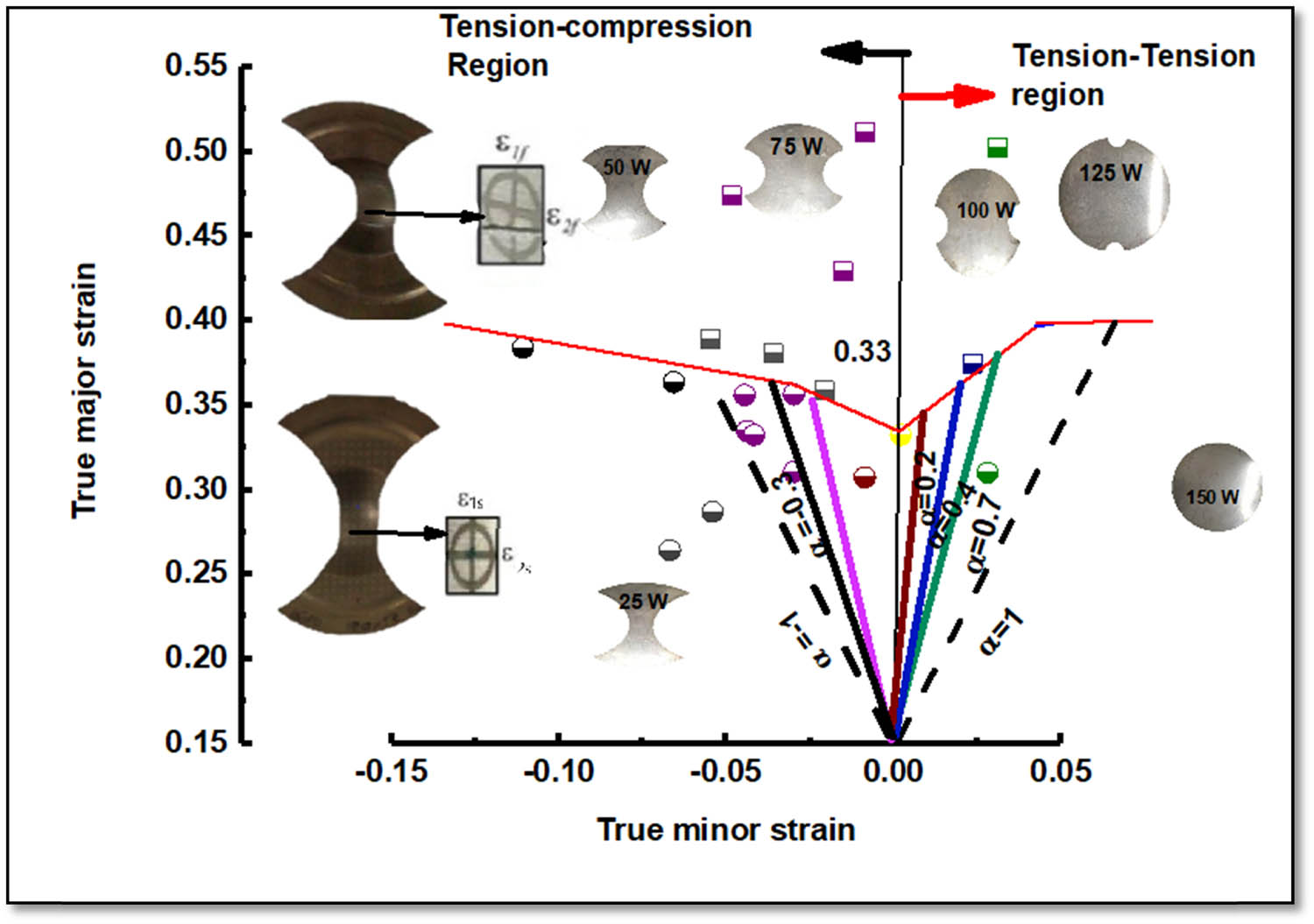

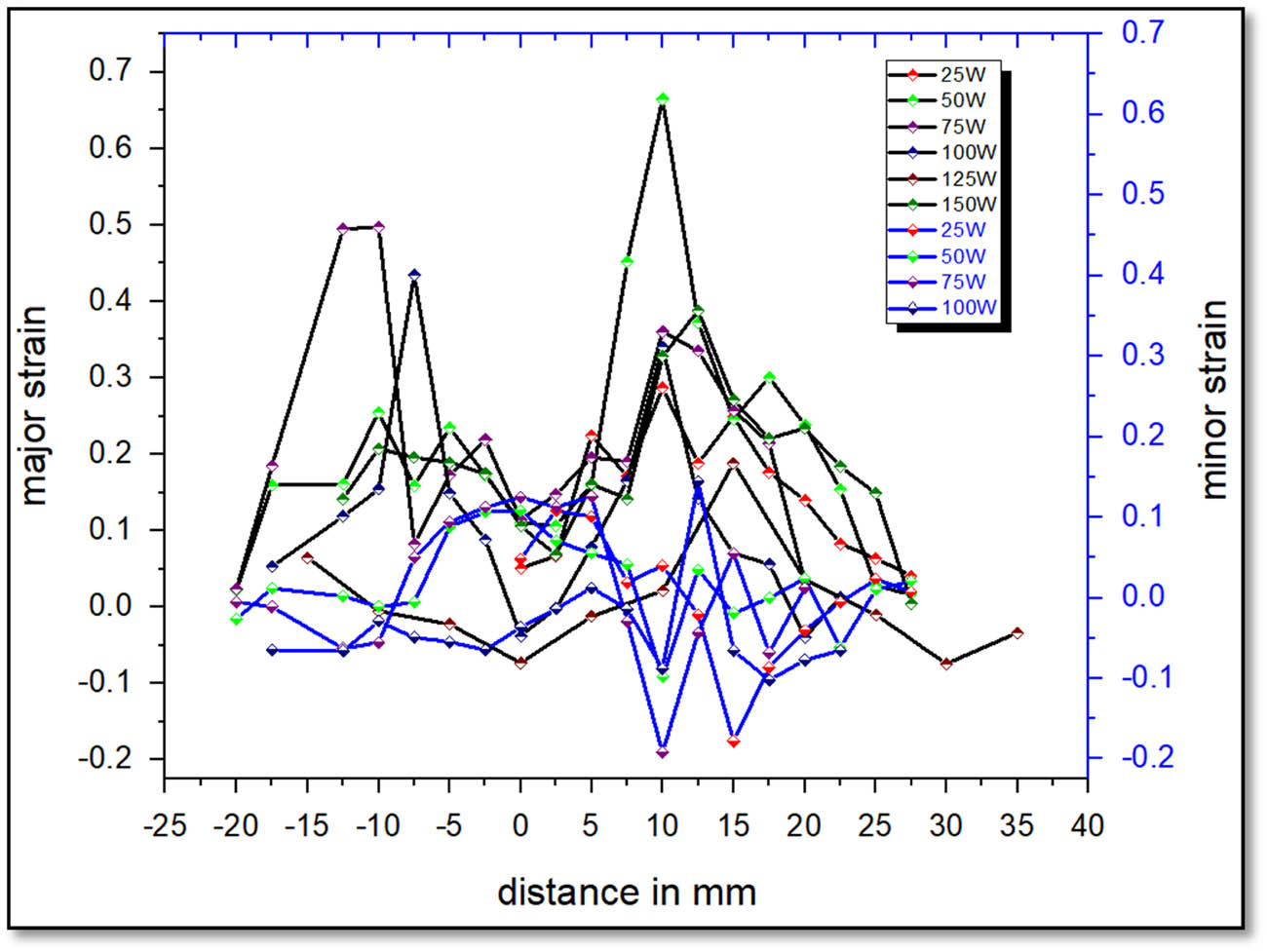

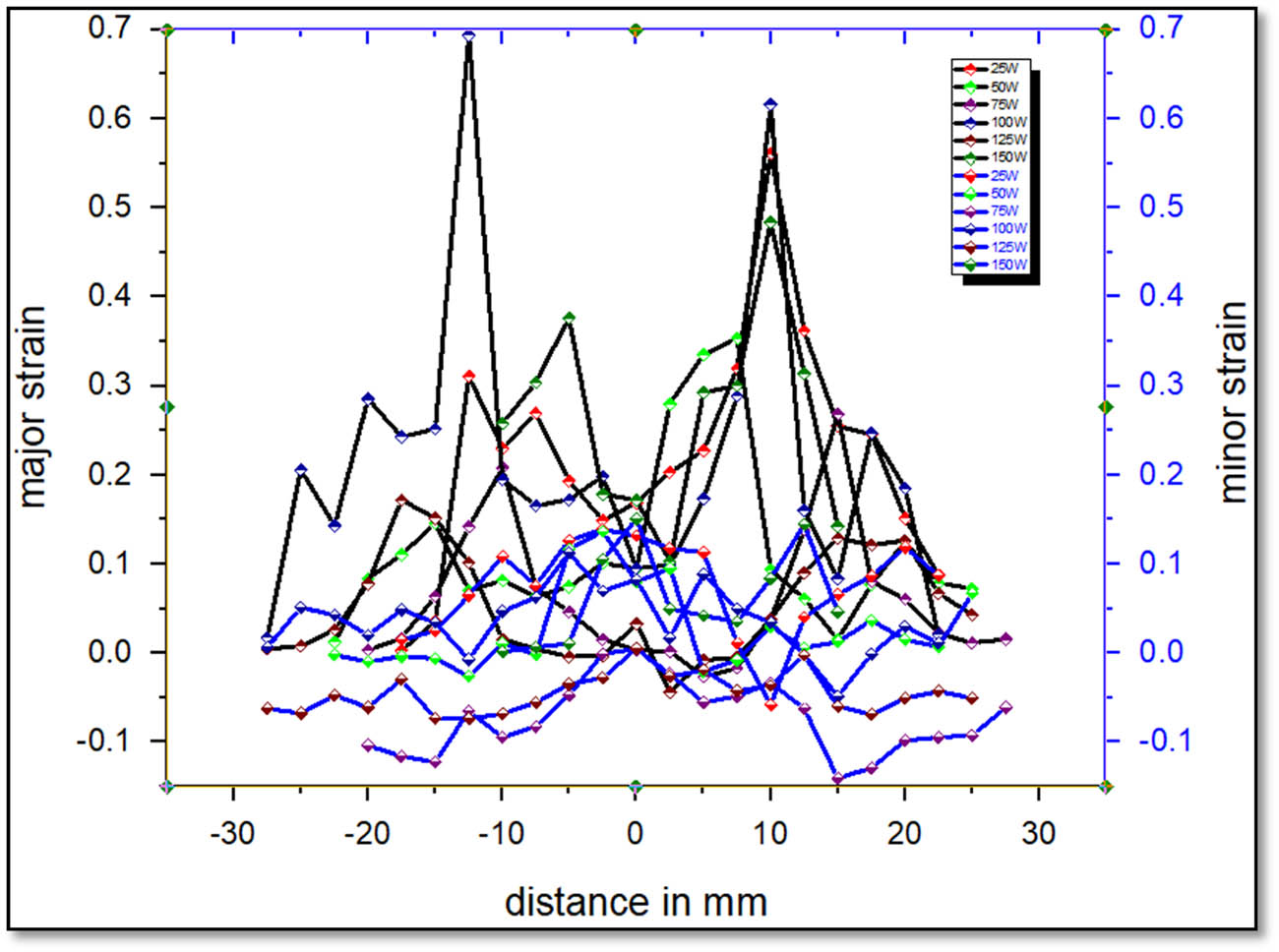

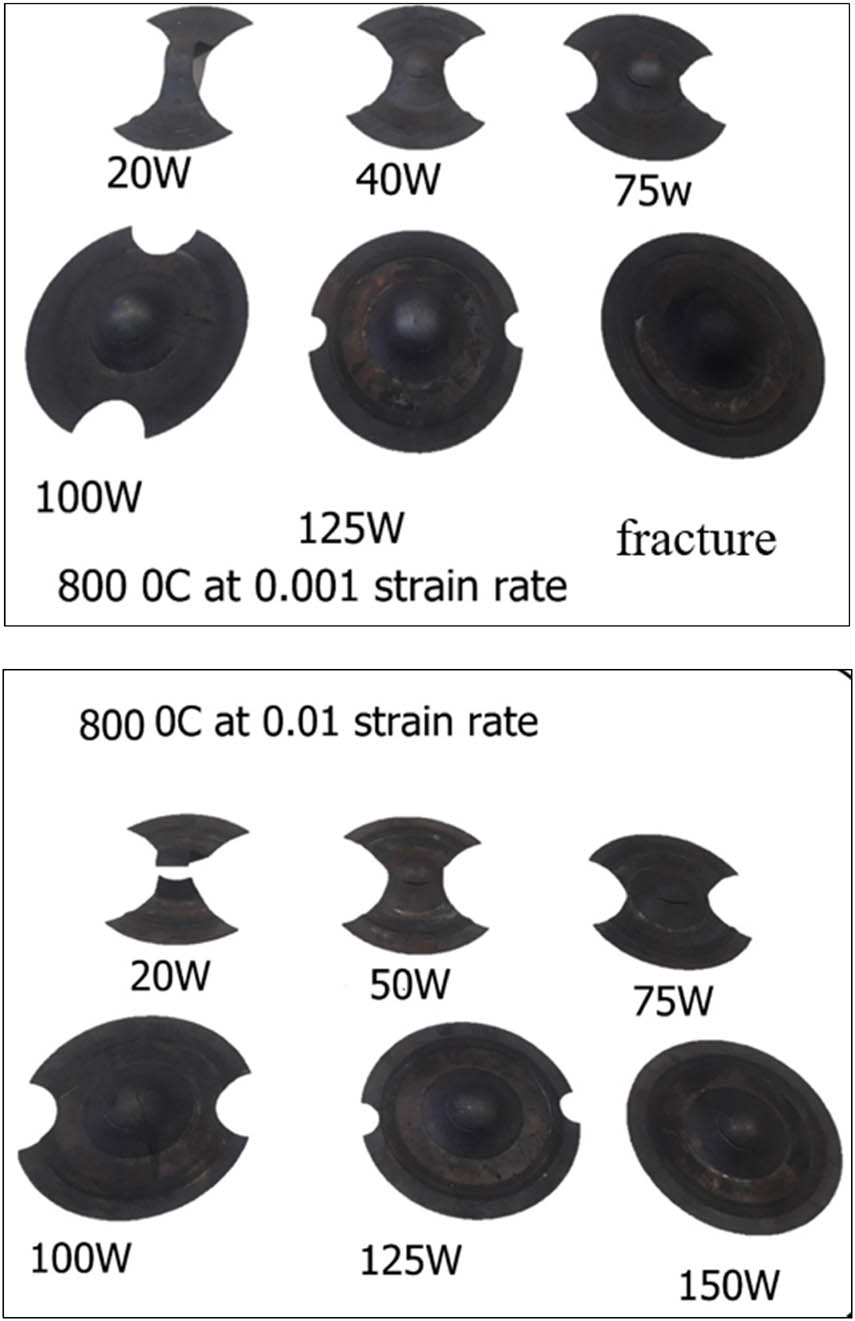

Different cups stretched from different diameter blanks at 650°C, at two different strain rates of 10−2 & 10−3 s−1, are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Here, all the specimens of different widths have been stretched and fractured, resulting in an increased straining limit FLD of n = 0.28 at 650°C, 10−2 s−1 as shown in Figure 6. Due to a decrease in the strain rate, the formability limits are increased to n = 0.33 with an increase in the formability safe limits as shown in Figure 7. The strain distribution of the cup along the radial line from the cup center is shown in Figures 8 and 9. Although the thickness reduction is not uniform in the lower size diameter blank, it is more uniform in larger diameter blanks. Peaks in a strain distribution graph of various width specimens indicate a strain distribution is consistent at a strain rate that is 10−3 s−1 and that ellipse deformation at punch radius is greater. Table 1 illustrates that the samples at lower strain rates (10−3 s−1) have a slightly greater limiting dome height than those at higher strain rates (10−2 s−1).

Experimental Fracture Forming Limit Curve (FFLD) of 650°C at 10−2 s−1.

Experimental Fracture Forming Limit Curve (FFLD) of 650°C at 10−3 s−1.

Strain distribution of cups stretched at 650°C from different sizes of the blanks at 10−2 s−1.

Strain distribution of cups stretched at 650°C from different sizes of the blanks at 10−3 s−1.

Bigger-sized blanks can be stretched deep without fracture at elevated temperatures. Blank widths greater than 100 W stretched deep into a die cavity are shown from the limiting dome height results (Table 2), while blank widths of 25, 50, and 75 W are drawn into the die cavity due to insufficient holding force. High variations in thickness lead to poor-quality cups. At higher temperatures in hot forming, although the thickness of the cup decreases more, it becomes more uniform. It was observed with these experiments that as the temperature rises, the material’s formability increases at low strain rates.

Simulation and experimental LDH values for punch-stretched ASS-304 steel blanks at 650°C temperature and strain rates of 10−3 s−1 and 10−2 s−1, respectively, for different sheet widths in three orientations

| 650°C | LDH at strain rate (10−2 s−1) in mm | LDH at strain rate (10−3 s−1) in mm |

|---|---|---|

| (150 × 25) W | 20.8 | 22.36 |

| (150 × 50) W | 20.4 | 22.8 |

| (150 × 75) W | 20.42 | 22.3 |

| (150 × 100) W | 21.3 | 22.6 |

| (150 × 125) W | 20.3 | 22.36 |

| (150 × 150) W | 20.1 | 22.06 |

3.2 Hot stretch forming at 800°C

Figure 10 shows various cups stretched from the different diameter blanks at 800°C. Here, in 150 × 20 mm blank, necking is not observed, rather it gets fractured. At this temperature, all other blank widths are properly deep stretched. This indicates that the material becomes more formable at 800°C than compared to material at 650°C, which might be due to the DSA phenomena occurring in the material. It had been investigated that at 800°C ASS 304 goes through strain hardening phenomenon. In this region, FLD has been found to have increased to n = 0.4416 at 10−2 s−1.

Experimentally stretched cups at a temperature of 800°C, strain rate 10−2 and 10−3 s−1.

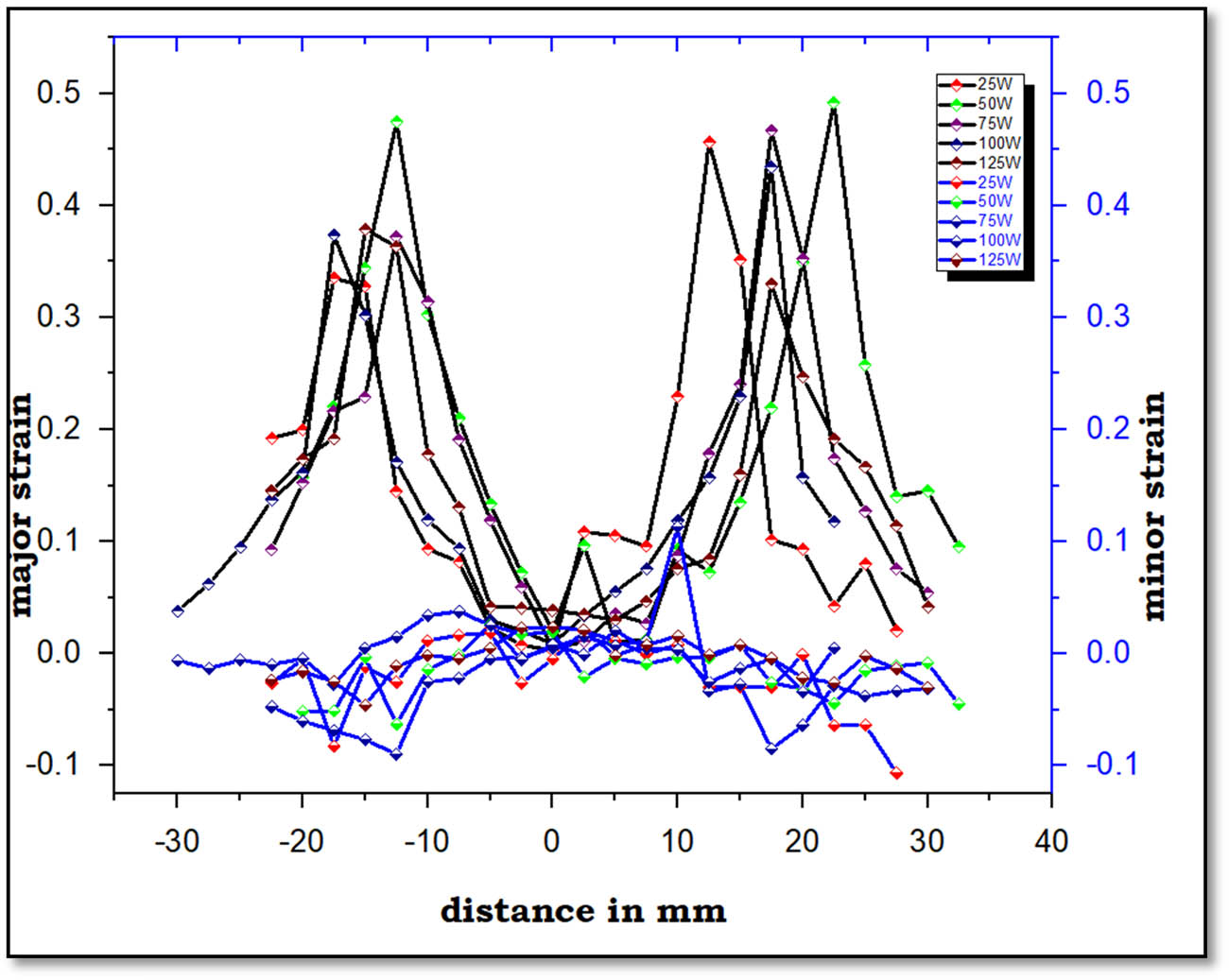

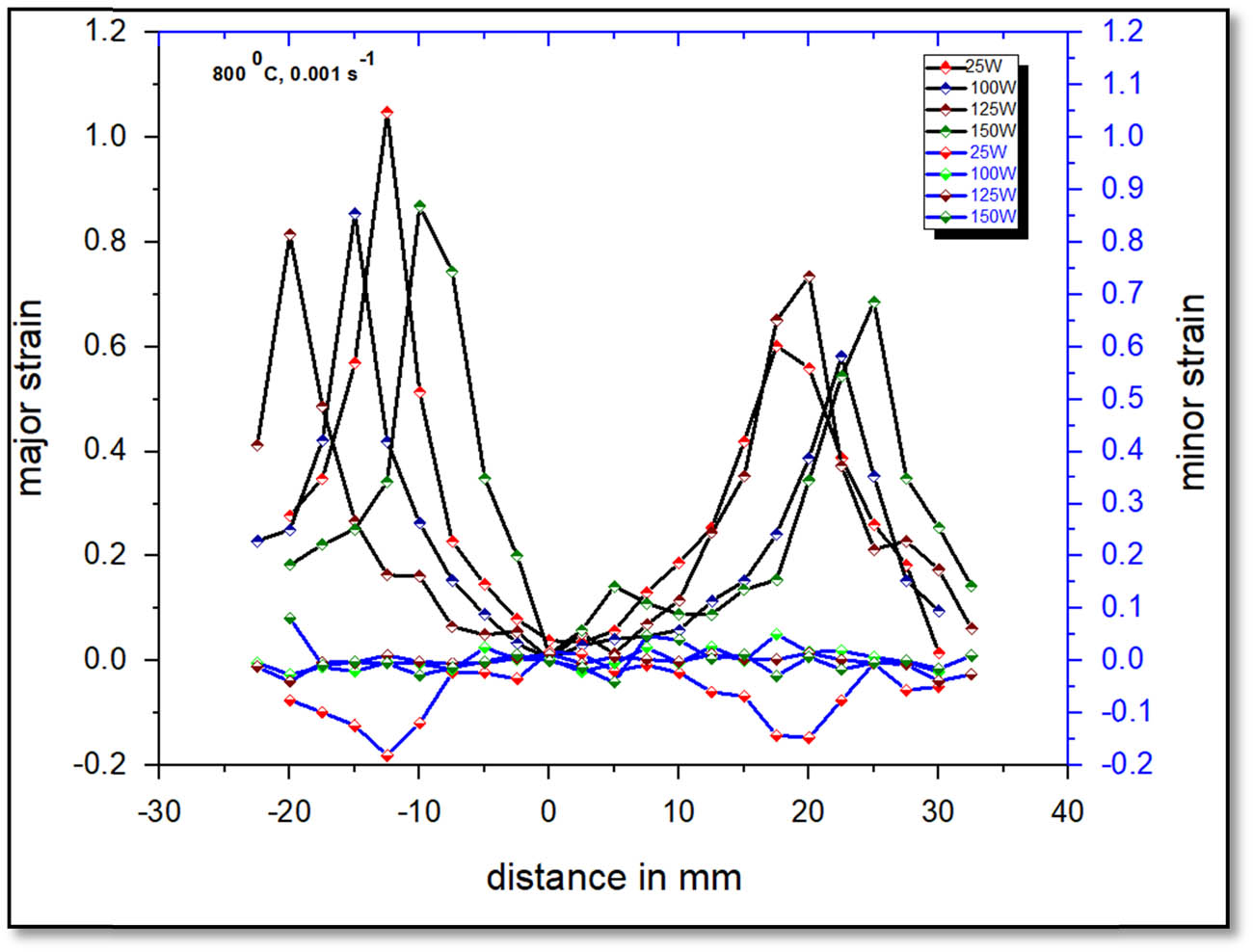

The strain distribution of the cup along the radial line from the cup center is shown in Figure 11 at a strain rate of 10−2 s−1 and strain rate of 10−3 s−1. Steep strain gradients imply a non-uniform distribution of strain. At lower strain rates, the strain distribution is more uniform compared to higher strain rates as shown in Figure 12. It is shown that at 10−2 s−1 the two blanks 25 and 100 W minor profiles are showing deviation compared to other distribution profiles which indicates lateral drawing of deformation whereas at 10−3 s−1 only 25 W blank profile is behaving differently compared to other profiles. The experimental fracture forming limit curve was plotted at two strain rates as shown in Figures 13 and 14. The curve shows that at a lower strain rate, there is an increase in the formability at a hot working temperature. From FFLDs at a strain rate of 10−3 s−1 the value of n = 0.8024 compared to the value at a strain rate of 10−2 s−1, n = 0.441. The bandwidth between the safe curve and fracture curve is very less showing a possibility of fracture when the load crosses the safe region.

Strain distribution of cups stretched at 800°C from different sizes of the blanks at 10−2 s−1.

Strain distribution of cups stretched at 800°C from different sizes of the blanks at 10−3 s−1.

Experimental Forming limit curve (FLD) of 800°C at 10−2 s−1.

Experimental Forming limit curve (FLD) of 800°C at 10−3 s−1.

Bigger-sized blanks can be stretched deep without fracture at elevated temperatures. Blank widths greater than 75 W stretched deep into a die cavity are shown from the limiting dome height results (Table 3), while blank widths of 25, 50, and 75 W are drawn into the die cavity due to insufficient holding force. High variations in thickness lead to poor-quality cups. At higher temperatures in hot forming, although the thickness of the cup decreases more, it becomes more uniform. It was observed with these experiments that as the temperature rises, the material’s formability increases at low strain rates.

Experimental LDH and simulation values of the punch-stretched blanks of ASS-304 steel at 800°C temperature and strain rate of 10−2 s−1, 10−3 s−1, for various blank widths in three orientations

| 800°C | LDH at strain rate (10−2 s−1) in mm | LDH at strain rate (10−3 s−1) in mm |

|---|---|---|

| (150 × 25) W | 22.36 | 26.10 |

| (150 × 50) W | 22.16 | 26.24 |

| (150 × 75) W | 22.10 | 26.06 |

| (150 × 100) W | 22.40 | 26.08 |

| (150 × 125) W | 22.08 | 26.28 |

| (150 × 150) W | 22.10 | 25.70 |

4 Conclusions

This research focused on studying the Enhanced formability behavior of ASS 304 at hot working temperatures. FLD has been developed for ASS 304 at 650 ˚C and 800˚C by Experimentation, these investigations bring out the following outcomes:

The temperature affects the formability parameters with a limitation. With the increase in temperature, the forming limits of ASS 304 are increasing but at 800°C the gap between the fracture limit diagram and the safe limit diagram is minimum so formability at 650°C is good and safe.

The strain rate has more effect on formability parameters. At low strain rates the forming limits are higher, better-limiting dome height of the cup, and uniform strain distribution is observed compared to the random strain distribution strain rates leading to the early failure of the cup.

As a result, when ASS 304 is hot formed, the sheet’s stretchability rises with temperatures up to 650°C, beyond which it has the opposite impact on drawability. Therefore, with minimal thickness variations in stretch-forming ASS 304 sheets, FLD can be regarded as being maximum at 650°C within realistic experimental bounds.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge GRIET, Hyderabad and MIT, MAHE Bengaluru Campus for their provision of facilities and financial support. The authors extend their appreciation for the helpful feedback and ideas given by the anonymous reviewers, guest editor, and editor-in-chief, which significantly improved the article's quality.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Din Bandhu, Rakesh Chandrashekar; methodology: Akkireddy Anitha Lakshmi, Ashish Kumar; investigation: Akkireddy Anitha Lakshmi, Ashish Kumar; DATA CURATION: Akkireddy Anitha Lakshmi, Ashish Kumar; formal analysis: Akkireddy Anitha Lakshmi, Ashish Kumar; resources: Din Bandhu, Rakesh Chandrashekar; software: Ashish Kumar, Rakesh Chandrashekhar; supervision: Din Bandhu, Rakesh Chandrashekar; validation: Akkireddy Anitha Lakshmi, Ashish Kumar; writing – original draft: Akkireddy Anitha Lakshmi; writing – review & editing: Din Bandhu.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Pardo, A., M. C. Merino, A. E. Coy, F. Viejo, R. Arrabal, and E. Matykina. Pitting corrosion behavior of austenitic stainless steels combining effects of Mn and Mo additions. Corrosion Science, Vol. 50, 2008, pp. 1796–1806.10.1016/j.corsci.2008.04.005Search in Google Scholar

[2] Rathod, V. P. and S. Tanveer. Pulsatile flow of couple stress fluid through a porous medium with periodic body acceleration and magnetic field. Bulletin of the Malaysian Mathematical Sciences Society, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2009, pp. 245–259.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Jisha, P. K., S. C. Prashantha, and H. Nagabhushana. Luminescent properties of Tb doped gadolinium aluminate nanophosphors for display and forensic applications. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2017, pp. 437–444.10.1016/j.jsamd.2017.10.001Search in Google Scholar

[4] Mohan, M. M., D. Bandhu, P. V. Mahesh, A. Thakur, U. Deka, A. Saxena, et al. Machining performance optimization of graphene carbon fiber hybrid composite using TOPSIS-Taguchi approach. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing, 2024.10.1007/s12008-024-01768-4Search in Google Scholar

[5] Barat, P., B. Raj, and D. K. Bhatracharya. A standardized procedure for eddy-current testing of stainless steel, thin-walled nuclear fuel element cladding tubes. NDT International, Vol. 15, 1982, pp. 251–255.10.1016/0308-9126(82)90034-7Search in Google Scholar

[6] Alrobei, H., M. K. Prashanth, C. R. Manjunatha, C. P. Kumar, C. P. Chitrabanu, P. D. Shivaramu, et al. Adsorption of anionic dye on eco-friendly synthesised reduced graphene oxide anchored with lanthanum aluminate: Isotherms, kinetics and statistical error analysis. Ceramics International, Vol. 47, No. 7, 2021, pp. 10322–10331.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.07.251Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kulandaivel, D., I. G. Rahamathullah, A. P. Sathiyagnanam, K. Gopal, and D. Damodharan. Effect of retarded injection timing and EGR on performance, combustion and emission characteristics of a CRDi diesel engine fueled with WHDPE oil/diesel blends. Fuel, Vol. 278, 2020, id. 118304.10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118304Search in Google Scholar

[8] Vinay, D. L., R. Keshavamurthy, S. Erannagari, A. Gajakosh, Y. D. Dwivedi, D. Bandhu, et al. Parametric analysis of processing variables for enhanced adhesion in metal-polymer composites fabricated by fused deposition modeling. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, Vol. 38, No. 3, 2024, pp. 331–354.10.1080/01694243.2023.2228496Search in Google Scholar

[9] Tugcu, P., P. D. Wu, and K. W. Neale. On the predictive capabilities of anisotropic yield criteria for metals undergoing shearing deformations. International Journal of Plasticity, Vol. 18, 2002, pp. 1219–1236.10.1016/S0749-6419(01)00068-7Search in Google Scholar

[10] Hora, S. K., R. Poongodan, R. P. De Prado, M. Wozniak, and P. B. Divakarachari. Long short-term memory network-based metaheuristic for effective electric energy consumption prediction. Applied Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 23, 2021, id. 11263.10.3390/app112311263Search in Google Scholar

[11] Thakar, H. H., M. D. Chaudhari, J. J. Vora, V. Patel, S. Das, D. Bandhu, et al. Performance optimization and investigation of metal-cored filler wires for high-strength steel during gas metal arc welding. High Temperature Materials and Processes, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2023, id. 20220305.10.1515/htmp-2022-0305Search in Google Scholar

[12] Paquet, D., P. Dondeti, and S. Gosh. Dual-stage nested homogenization for rate-dependent anisotropic elasto-plasticity model of dendritic cast aluminum alloys. International Journal of Plasticity. Vol. 27, No. 10, 2011, pp. 1677–170110.1016/j.ijplas.2011.02.002Search in Google Scholar

[13] Raj, T. V., P. A. Hoskeri, H. B. Muralidhara, C. R. Manjunatha, K. Y. Kumar, and M. S. Raghu. Facile synthesis of perovskite lanthanum aluminate and its green reduced graphene oxide composite for high performance supercapacitors. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, Vol. 858, 2020, id. 113830.10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.113830Search in Google Scholar

[14] Jayabal, R., S. Subramani, D. Dillikannan, Y. Devarajan, L. Thangavelu, M. Nedunchezhiyan, et al. Multi-objective optimization of performance and emission characteristics of a CRDI diesel engine fueled with sapota methyl ester/diesel blends. Energy, Vol. 250, 2022, id. 123709.10.1016/j.energy.2022.123709Search in Google Scholar

[15] Lakshmi, A. A., C. S. Rao, and T. Buddi. Prediction of superplasticity of austenitic stainless steel-304 at hot working temperatures. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 18, 2019, pp. 2814–2822.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.148Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ram, J. P., D. S. Pillai, A. M. Ghias, and N. Rajasekar. Performance enhancement of solar PV systems applying P&O assisted flower pollination algorithm (FPA). Solar Energy, Vol. 199, 2020, pp. 214–229.10.1016/j.solener.2020.02.019Search in Google Scholar

[17] Kumar, K. Y., H. Saini, D. Pandiarajan, M. K. Prashanth, L. Parashuram, and M. S. Raghu. Controllable synthesis of TiO2 chemically bonded graphene for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and dye degradation. Catalysis Today, Vol. 340, 2020, pp. 170–177.10.1016/j.cattod.2018.10.042Search in Google Scholar

[18] Yogananda, H. S., R. B. Basavaraj, G. P. Darshan, B. D. Prasad, R. Naik, S. C. Sharma, et al. New design of highly sensitive and selective MoO3: Eu3 + micro-rods: Probing of latent fingerprints visualization and anti-counterfeiting applications. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Vol. 528, 2018, pp. 443–456.10.1016/j.jcis.2018.04.104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Lakshmi, A. A., C. Rao, N. Kotkunde, R. Subbiah, and S. K. Singh. Forming limit diagram of AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel at elevated temperature: experimentation and modelling. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, Vol. 9, No. 12, 2018, pp. 403–407. http://www.iaeme.com/ijmet/issues.asp.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Reddy, B. M., R. M. Reddy, P. V. Reddy, N. N. A. Prashanth, and D. Bandhu. Effect of alkali treatment on mechanical properties and morphology of the Balanites aegyptiaca composite. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 2023; 09544062231217596.10.1177/09544062231217596Search in Google Scholar

[21] Bandhu, D., A. S. Barno, E. Ali, M. N. Fenjan, S. H. Hlail, and F. Naderian. Recycling of agro-industrial waste by fabricating laminated Al-metal matrix composites: a numerical simulation and experimental study. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing, 2024.10.1007/s12008-024-01759-5Search in Google Scholar

[22] Desmorat, R. and R. Marukk. Non-quadratic kelvin modes based plasticity for anisotropic materials. International Journal of Plasticity, Vol. 27, 2011, pp. 328–351.10.1016/j.ijplas.2010.06.003Search in Google Scholar

[23] Thomson, W. K. and L. Kelvin. Elements of a mathematical theory of elasticity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, Vol. 166, 1856, pp. 481–498.10.1098/rstl.1856.0022Search in Google Scholar

[24] Reddy, D. M., A. A. Lakshmi, and A. ul Haq. Experimental Taguchi approach and Gray–Taguchi optimization on mechanical properties of aluminum 8011 alloy sheet under uniaxial tensile loads. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 19, 2019, pp. 366–371.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.614Search in Google Scholar

[25] Lakshmi, A. A., C. S. Rao, M. Srikanth, K. Faisal, K. Fayaz, and S. K. Singh. Prediction of mechanical properties of ASS 304 in superplastic region using artificial neural networks. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2018, pp. 3704–3712.10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.622Search in Google Scholar

[26] Segurado, J., R. A. Lebensohn, J. Lorca, and C. N. Tome. Multi scale modeling of plasticity based on embedding the viscoplastic self-consistent formulation in implicit finite elements. International Journal of Plasticity, Vol. 28, 2012, pp. 124–140.10.1016/j.ijplas.2011.07.002Search in Google Scholar

[27] Fourmeau, M., T. Borvki, BenallalA, O. G. Lademo, and O. S. Hopperstad. On the plastic anisotropy of an aluminum alloy and its influence on constrained multi axial flow. International Journal of Plasticity, Vol. 27, 2011, pp. 2005–2025.10.1016/j.ijplas.2011.05.017Search in Google Scholar

[28] Barlat, F., H. Aretz, J. W. Yoon, M. E. Karabin, J. C. Brem, and R. E. Dick. Linear transformation-based anisotropic yield functions. International Journal of Plasticity, Vol. 21, 2005, pp. 1009–1039.10.1016/j.ijplas.2004.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[29] Yoon, J. W., R. E. Dick, and F. Barlat. A new analytical theory for earing generated from anisotropic plasticity. International Journal of Plasticity, Vol. 27, 2011, pp. 1165–1184.10.1016/j.ijplas.2011.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[30] Soarea, M. A. and W. A. Curtin. Single-mechanism rate theory for dynamic strain aging in FCC metal. Acta Materialia, Vol. 56, 2008, pp. 4091–4101.10.1016/j.actamat.2008.04.030Search in Google Scholar

[31] Lakshmi, A. A., C. S. Rao, J. Gangadhar, C. Srinivasu, and S. K. Singh. Review of processing maps and development of qualitative processing maps. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2017, pp. 946–956.10.1016/j.matpr.2017.01.106Search in Google Scholar

[32] Lakshmi, A., T. Buddi, C. Bandhavi, and R. Subbiah. Investigation of microstructure and mechanical properties of austenite stainless steel 304 during tempering and cryogenic heat treatment. In E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 184, EDP Sciences, 2020, p. 01006.10.1051/e3sconf/202018401006Search in Google Scholar

[33] Manne, P. K., N. S. Kumar, T. Buddi, A. A. Lakshmi, R. Subbiah. Powder metallurgy techniques for titanium alloys-A review. In E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 184, EDP Sciences, 2020, p. 01045.10.1051/e3sconf/202018401045Search in Google Scholar

[34] Harshini, D., A. ul Haq, T. Buddi, K. A. Kumar, and A. A. Lakshmi. Comparative study on mechanical behavior of ASS 316L for low and high temperature applications. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 19, 2019, pp. 767–771.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.08.127Search in Google Scholar

[35] Subbiah, R., A. Arun, A. Anitha Lakshmi, A. Naga Sai Harika, N. Ram, and N. Sateesh. Experimental study of wear behaviour on Al-2014 alloy coated with thermal spray HVOF (High Velocity Oxy-Fuel) and plasma spray process–A review. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 18, 2019, pp. 5151–5157.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.512Search in Google Scholar

[36] Dandekar, T. R., R. K. Khatirkar, A. Gupta, N. Bibhanshu, A. Bhadauria, and S. Suwas. Strain rate sensitivity behaviour of Fe–21Cr-1.5 Ni–5Mn alloy and its constitutive modelling. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 271, 2021, id. 124948.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2021.124948Search in Google Scholar

[37] Cottrell, A. H. and B. A. Bilby. Dislocation theory of yielding and strain aging of Iron. Proceedings of Physical Society A, Vol. 62, 1949, pp. 49–62.10.1088/0370-1298/62/1/308Search in Google Scholar

[38] Jayahari, L., P. V. Sasidhar, P. P. Reddy, B. BaluNaik, A. K. Gupta, and S. K. Singh. Formability studies of ASS 304 and evaluation of friction for Al in deep drawing setup at elevated temperatures using LS-DYNA. Journal of King Saud University-Engineering Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2014, pp. 21–31.10.1016/j.jksues.2012.12.006Search in Google Scholar

[39] Zhao, J., T. Wang, F. Jia, Z. Li, C. Zhou, Q. Huang, et al. Experimental investigation on micro deep drawing of stainless-steel foils with different microstructural characteristics. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 34, 2021, id. 40.10.1186/s10033-021-00556-5Search in Google Scholar

[40] Unnikrishnan, R., K. S. Idury, T. P. Ismail, A. Bhadauria, S. K. Shekhawat, R. K. Khatirkar, et al. Effect of heat input on the microstructure, residual stresses and corrosion resistance of 304L austenitic stainless steel weldments. Materials Characterization, Vol. 93, 2014, pp. 10–23.10.1016/j.matchar.2014.03.013Search in Google Scholar

[41] Adin, M. Ş. A parametric study on the mechanical properties of MIG and TIG welded dissimilar steel joints. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, Vol. 38, No. 1, 2024, pp. 115–138.10.1080/01694243.2023.2221391Search in Google Scholar

[42] Adin, M. Ş. and B. İşcan. Optimization of process parameters of medium carbon steel joints joined by MIG welding using Taguchi method. European Mechanical Science, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2022, pp. 17–26.10.26701/ems.989945Search in Google Scholar

[43] Maurya, A. K., W. N. Khan, A. Patnaik, M.Ş. Adin, R. Chhibber, and C. Pandey. Tribological performance of gas tungsten arc welded dissimilar joint of sDSS 2507/IN-625 for marine application. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2023, id. 23.10.1007/s43452-023-00832-2Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- De-chlorination of poly(vinyl) chloride using Fe2O3 and the improvement of chlorine fixing ratio in FeCl2 by SiO2 addition

- Reductive behavior of nickel and iron metallization in magnesian siliceous nickel laterite ores under the action of sulfur-bearing natural gas

- Study on properties of CaF2–CaO–Al2O3–MgO–B2O3 electroslag remelting slag for rack plate steel

- The origin of {113}<361> grains and their impact on secondary recrystallization in producing ultra-thin grain-oriented electrical steel

- Channel parameter optimization of one-strand slab induction heating tundish with double channels

- Effect of rare-earth Ce on the texture of non-oriented silicon steels

- Performance optimization of PERC solar cells based on laser ablation forming local contact on the rear

- Effect of ladle-lining materials on inclusion evolution in Al-killed steel during LF refining

- Analysis of metallurgical defects in enamel steel castings

- Effect of cooling rate and Nb synergistic strengthening on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-strength rebar

- Effect of grain size on fatigue strength of 304 stainless steel

- Analysis and control of surface cracks in a B-bearing continuous casting blooms

- Application of laser surface detection technology in blast furnace gas flow control and optimization

- Preparation of MoO3 powder by hydrothermal method

- The comparative study of Ti-bearing oxides introduced by different methods

- Application of MgO/ZrO2 coating on 309 stainless steel to increase resistance to corrosion at high temperatures and oxidation by an electrochemical method

- Effect of applying a full oxygen blast furnace on carbon emissions based on a carbon metabolism calculation model

- Characterization of low-damage cutting of alfalfa stalks by self-sharpening cutters made of gradient materials

- Thermo-mechanical effects and microstructural evolution-coupled numerical simulation on the hot forming processes of superalloy turbine disk

- Endpoint prediction of BOF steelmaking based on state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms

- Effect of calcium treatment on inclusions in 38CrMoAl high aluminum steel

- Effect of isothermal transformation temperature on the microstructure, precipitation behavior, and mechanical properties of anti-seismic rebar

- Evolution of residual stress and microstructure of 2205 duplex stainless steel welded joints during different post-weld heat treatment

- Effect of heating process on the corrosion resistance of zinc iron alloy coatings

- BOF steelmaking endpoint carbon content and temperature soft sensor model based on supervised weighted local structure preserving projection

- Innovative approaches to enhancing crack repair: Performance optimization of biopolymer-infused CXT

- Structural and electrochromic property control of WO3 films through fine-tuning of film-forming parameters

- Influence of non-linear thermal radiation on the dynamics of homogeneous and heterogeneous chemical reactions between the cone and the disk

- Thermodynamic modeling of stacking fault energy in Fe–Mn–C austenitic steels

- Research on the influence of cemented carbide micro-textured structure on tribological properties

- Performance evaluation of fly ash-lime-gypsum-quarry dust (FALGQ) bricks for sustainable construction

- First-principles study on the interfacial interactions between h-BN and Si3N4

- Analysis of carbon emission reduction capacity of hydrogen-rich oxygen blast furnace based on renewable energy hydrogen production

- Just-in-time updated DBN BOF steel-making soft sensor model based on dense connectivity of key features

- Effect of tempering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Q125 shale gas casing steel

- Review Articles

- A review of emerging trends in Laves phase research: Bibliometric analysis and visualization

- Effect of bottom stirring on bath mixing and transfer behavior during scrap melting in BOF steelmaking: A review

- High-temperature antioxidant silicate coating of low-density Nb–Ti–Al alloy: A review

- Communications

- Experimental investigation on the deterioration of the physical and mechanical properties of autoclaved aerated concrete at elevated temperatures

- Damage evaluation of the austenitic heat-resistance steel subjected to creep by using Kikuchi pattern parameters

- Topical Issue on Focus of Hot Deformation of Metaland High Entropy Alloys - Part II

- Synthesis of aluminium (Al) and alumina (Al2O3)-based graded material by gravity casting

- Experimental investigation into machining performance of magnesium alloy AZ91D under dry, minimum quantity lubrication, and nano minimum quantity lubrication environments

- Numerical simulation of temperature distribution and residual stress in TIG welding of stainless-steel single-pass flange butt joint using finite element analysis

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part I

- Electro-thermal performance evaluation of a prismatic battery pack for an electric vehicle

- Experimental analysis and optimization of machining parameters for Nitinol alloy: A Taguchi and multi-attribute decision-making approach

- Experimental and numerical analysis of temperature distributions in SA 387 pressure vessel steel during submerged arc welding

- Optimization of process parameters in plasma arc cutting of commercial-grade aluminium plate

- Multi-response optimization of friction stir welding using fuzzy-grey system

- Mechanical and micro-structural studies of pulsed and constant current TIG weldments of super duplex stainless steels and Austenitic stainless steels

- Stretch-forming characteristics of austenitic material stainless steel 304 at hot working temperatures

- Work hardening and X-ray diffraction studies on ASS 304 at high temperatures

- Study of phase equilibrium of refractory high-entropy alloys using the atomic size difference concept for turbine blade applications

- A novel intelligent tool wear monitoring system in ball end milling of Ti6Al4V alloy using artificial neural network

- A hybrid approach for the machinability analysis of Incoloy 825 using the entropy-MOORA method

- Special Issue on Recent Developments in 3D Printed Carbon Materials - Part II

- Innovations for sustainable chemical manufacturing and waste minimization through green production practices

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part I

- Characterization of Co–Ni–TiO2 coatings prepared by combined sol-enhanced and pulse current electrodeposition methods

- Hot deformation behaviors and microstructure characteristics of Cr–Mo–Ni–V steel with a banded structure

- Effects of normalizing and tempering temperature on the bainite microstructure and properties of low alloy fire-resistant steel bars

- Dynamic evolution of residual stress upon manufacturing Al-based diesel engine diaphragm

- Study on impact resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete after exposure to fire

- Bonding behaviour between steel fibre and concrete matrix after experiencing elevated temperature at various loading rates

- Diffusion law of sulfate ions in coral aggregate seawater concrete in the marine environment

- Microstructure evolution and grain refinement mechanism of 316LN steel

- Investigation of the interface and physical properties of a Kovar alloy/Cu composite wire processed by multi-pass drawing

- The investigation of peritectic solidification of high nitrogen stainless steels by in-situ observation

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of submerged arc welded medium-thickness Q690qE high-strength steel plate joints

- Experimental study on the effect of the riveting process on the bending resistance of beams composed of galvanized Q235 steel

- Density functional theory study of Mg–Ho intermetallic phases

- Investigation of electrical properties and PTCR effect in double-donor doping BaTiO3 lead-free ceramics

- Special Issue on Thermal Management and Heat Transfer

- On the thermal performance of a three-dimensional cross-ternary hybrid nanofluid over a wedge using a Bayesian regularization neural network approach

- Time dependent model to analyze the magnetic refrigeration performance of gadolinium near the room temperature

- Heat transfer characteristics in a non-Newtonian (Williamson) hybrid nanofluid with Hall and convective boundary effects

- Computational role of homogeneous–heterogeneous chemical reactions and a mixed convective ternary hybrid nanofluid in a vertical porous microchannel

- Thermal conductivity evaluation of magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluid and dusty particles with thermal radiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- De-chlorination of poly(vinyl) chloride using Fe2O3 and the improvement of chlorine fixing ratio in FeCl2 by SiO2 addition

- Reductive behavior of nickel and iron metallization in magnesian siliceous nickel laterite ores under the action of sulfur-bearing natural gas

- Study on properties of CaF2–CaO–Al2O3–MgO–B2O3 electroslag remelting slag for rack plate steel

- The origin of {113}<361> grains and their impact on secondary recrystallization in producing ultra-thin grain-oriented electrical steel

- Channel parameter optimization of one-strand slab induction heating tundish with double channels

- Effect of rare-earth Ce on the texture of non-oriented silicon steels

- Performance optimization of PERC solar cells based on laser ablation forming local contact on the rear

- Effect of ladle-lining materials on inclusion evolution in Al-killed steel during LF refining

- Analysis of metallurgical defects in enamel steel castings

- Effect of cooling rate and Nb synergistic strengthening on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-strength rebar

- Effect of grain size on fatigue strength of 304 stainless steel

- Analysis and control of surface cracks in a B-bearing continuous casting blooms

- Application of laser surface detection technology in blast furnace gas flow control and optimization

- Preparation of MoO3 powder by hydrothermal method

- The comparative study of Ti-bearing oxides introduced by different methods

- Application of MgO/ZrO2 coating on 309 stainless steel to increase resistance to corrosion at high temperatures and oxidation by an electrochemical method

- Effect of applying a full oxygen blast furnace on carbon emissions based on a carbon metabolism calculation model

- Characterization of low-damage cutting of alfalfa stalks by self-sharpening cutters made of gradient materials

- Thermo-mechanical effects and microstructural evolution-coupled numerical simulation on the hot forming processes of superalloy turbine disk

- Endpoint prediction of BOF steelmaking based on state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms

- Effect of calcium treatment on inclusions in 38CrMoAl high aluminum steel

- Effect of isothermal transformation temperature on the microstructure, precipitation behavior, and mechanical properties of anti-seismic rebar

- Evolution of residual stress and microstructure of 2205 duplex stainless steel welded joints during different post-weld heat treatment

- Effect of heating process on the corrosion resistance of zinc iron alloy coatings

- BOF steelmaking endpoint carbon content and temperature soft sensor model based on supervised weighted local structure preserving projection

- Innovative approaches to enhancing crack repair: Performance optimization of biopolymer-infused CXT

- Structural and electrochromic property control of WO3 films through fine-tuning of film-forming parameters

- Influence of non-linear thermal radiation on the dynamics of homogeneous and heterogeneous chemical reactions between the cone and the disk

- Thermodynamic modeling of stacking fault energy in Fe–Mn–C austenitic steels

- Research on the influence of cemented carbide micro-textured structure on tribological properties

- Performance evaluation of fly ash-lime-gypsum-quarry dust (FALGQ) bricks for sustainable construction

- First-principles study on the interfacial interactions between h-BN and Si3N4

- Analysis of carbon emission reduction capacity of hydrogen-rich oxygen blast furnace based on renewable energy hydrogen production

- Just-in-time updated DBN BOF steel-making soft sensor model based on dense connectivity of key features

- Effect of tempering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Q125 shale gas casing steel

- Review Articles

- A review of emerging trends in Laves phase research: Bibliometric analysis and visualization

- Effect of bottom stirring on bath mixing and transfer behavior during scrap melting in BOF steelmaking: A review

- High-temperature antioxidant silicate coating of low-density Nb–Ti–Al alloy: A review

- Communications

- Experimental investigation on the deterioration of the physical and mechanical properties of autoclaved aerated concrete at elevated temperatures

- Damage evaluation of the austenitic heat-resistance steel subjected to creep by using Kikuchi pattern parameters

- Topical Issue on Focus of Hot Deformation of Metaland High Entropy Alloys - Part II

- Synthesis of aluminium (Al) and alumina (Al2O3)-based graded material by gravity casting

- Experimental investigation into machining performance of magnesium alloy AZ91D under dry, minimum quantity lubrication, and nano minimum quantity lubrication environments

- Numerical simulation of temperature distribution and residual stress in TIG welding of stainless-steel single-pass flange butt joint using finite element analysis

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part I

- Electro-thermal performance evaluation of a prismatic battery pack for an electric vehicle

- Experimental analysis and optimization of machining parameters for Nitinol alloy: A Taguchi and multi-attribute decision-making approach

- Experimental and numerical analysis of temperature distributions in SA 387 pressure vessel steel during submerged arc welding

- Optimization of process parameters in plasma arc cutting of commercial-grade aluminium plate

- Multi-response optimization of friction stir welding using fuzzy-grey system

- Mechanical and micro-structural studies of pulsed and constant current TIG weldments of super duplex stainless steels and Austenitic stainless steels

- Stretch-forming characteristics of austenitic material stainless steel 304 at hot working temperatures

- Work hardening and X-ray diffraction studies on ASS 304 at high temperatures

- Study of phase equilibrium of refractory high-entropy alloys using the atomic size difference concept for turbine blade applications

- A novel intelligent tool wear monitoring system in ball end milling of Ti6Al4V alloy using artificial neural network

- A hybrid approach for the machinability analysis of Incoloy 825 using the entropy-MOORA method

- Special Issue on Recent Developments in 3D Printed Carbon Materials - Part II

- Innovations for sustainable chemical manufacturing and waste minimization through green production practices

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part I

- Characterization of Co–Ni–TiO2 coatings prepared by combined sol-enhanced and pulse current electrodeposition methods

- Hot deformation behaviors and microstructure characteristics of Cr–Mo–Ni–V steel with a banded structure

- Effects of normalizing and tempering temperature on the bainite microstructure and properties of low alloy fire-resistant steel bars

- Dynamic evolution of residual stress upon manufacturing Al-based diesel engine diaphragm

- Study on impact resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete after exposure to fire

- Bonding behaviour between steel fibre and concrete matrix after experiencing elevated temperature at various loading rates

- Diffusion law of sulfate ions in coral aggregate seawater concrete in the marine environment

- Microstructure evolution and grain refinement mechanism of 316LN steel

- Investigation of the interface and physical properties of a Kovar alloy/Cu composite wire processed by multi-pass drawing

- The investigation of peritectic solidification of high nitrogen stainless steels by in-situ observation

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of submerged arc welded medium-thickness Q690qE high-strength steel plate joints

- Experimental study on the effect of the riveting process on the bending resistance of beams composed of galvanized Q235 steel

- Density functional theory study of Mg–Ho intermetallic phases

- Investigation of electrical properties and PTCR effect in double-donor doping BaTiO3 lead-free ceramics

- Special Issue on Thermal Management and Heat Transfer

- On the thermal performance of a three-dimensional cross-ternary hybrid nanofluid over a wedge using a Bayesian regularization neural network approach

- Time dependent model to analyze the magnetic refrigeration performance of gadolinium near the room temperature

- Heat transfer characteristics in a non-Newtonian (Williamson) hybrid nanofluid with Hall and convective boundary effects

- Computational role of homogeneous–heterogeneous chemical reactions and a mixed convective ternary hybrid nanofluid in a vertical porous microchannel

- Thermal conductivity evaluation of magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluid and dusty particles with thermal radiation