Study of phase equilibrium of refractory high-entropy alloys using the atomic size difference concept for turbine blade applications

-

Gokul Udayakumaran

and Basireddy Bhavani

Abstract

In the pursuit of advancing turbine blade materials, refractory high-entropy alloys (RHEAs) have emerged as promising candidates, offering superior performance at elevated temperatures compared to conventional superalloys. With the plateauing of melting temperatures in Ni-based superalloys, the demand for innovative material systems capable of substantial performance enhancements in turbines has increased. The expansive compositional space of high-entropy alloys (HEAs) presents a rich yet underexplored realm, particularly concerning the intricate phase equilibria pivotal for alloy stability at high temperatures. This research purpose is to elucidate the phase formation dynamics within the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEA system across varying atomic percentages of each constituent element. Employing two-dimensional mapping methodology for correlating atomic size difference and enthalpy mix parameters, enabling the differentiation between intermetallic (IM) phase and single-phase formations in the non-equimolar W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo system across numerous atomic percentages of each element. Major findings indicate distinct phase formations based on elemental compositions, with elevated nickel and rhenium percentages favouring single-phase solid solution (SPSS) structures, while diminished concentrations yield alternative configurations such as (IM + SPSS). Similarly, variations in tungsten and molybdenum concentrations influence phase stability. The ability to assess phases for diverse atomic percentages of elements in the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo system will facilitate to analyse HEA systems for high-temperature turbine blades.

1 Introduction

Advanced materials play a crucial role in the development and progress of technology across various industries. Advanced materials often exhibit superior mechanical, thermal, electrical, or optical properties compared to traditional materials. This enhanced performance allows for the development of more efficient and high-performance technologies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. As technology advances, there is a trend towards miniaturization of devices and components. Advanced materials with unique properties, such as nanomaterials or metamaterials, enable the design and manufacturing of smaller and more compact devices [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Advanced materials contribute to the development of energy-efficient technologies. Technology encompasses a wide range of industries, internet, and software plays a crucial role in enhancing efficiency, productivity, and innovation across these domains. The specific software needs in technology can vary based on the industry and application. The software needs in technology are dynamic and continually evolving as new technologies emerge. Depending on the specific requirements of a given industry or application, additional specialized software may be employed to address unique challenges and opportunities [2,18–23]. These software categories collectively form the technological ecosystem, enhancing various aspects of development, collaboration, security, and decision-making within the technology industry [4,24–28]. In the field of metallurgy, software tools like computational thermodynamics software are helpful in predicting phase transformations, equilibrium conditions, and properties of alloys at different temperatures and compositions.

The necessity for advanced materials exhibiting superior performance at elevated temperatures has become more imperative, given the increasingly intricate and harsh operating conditions in the realm of turbine blade applications, propelled by rapid advancements in technology. The escalating needs for high-temperature applications, the imperative for enhanced properties alloys capable of withstanding elevated temperature conditions in the context of the “space race,” the need for materials tailored for gas turbine blade applications, and relevant pursuits are steering the ongoing development of refractory-based high-entropy alloys (HEAs). The efficacy of energy production in industrial gas turbines is contingent upon the operating temperature, where efficiency experiences an upsurge with elevated temperatures. A constraining factor in achieving higher operating temperatures is the formidable environment that turbine blades endure, necessitating resilience against substantial stresses encountered at elevated temperatures [29–34].

There exist two primary material properties within the alloys of these blades that require enhancement to facilitate elevated operating temperatures of the turbine blades: (1) enhanced stability at high temperatures and (2) sustained strength at elevated temperatures. Presently, the prevalent utilization of nickel-based superalloys is evident [35–38]; however, this approach is nearing its limitations in improving the turbine disk’s operating temperature due to the approaching constraints of alloy composition in design. With the deceleration in the advancement of melting temperatures in nickel-based superalloys, there arises a demand for innovative material systems capable of manifesting substantial enhancements in turbine performance. Recently identified as a class of materials, refractory high-entropy alloys (RHEAs) demonstrate notable high-strength and high-toughness characteristics at elevated temperatures, thereby showcasing their potential for application in turbine blades [39–43].

Owing to variations in the size of atoms among these elements, HEAs tend to deviate from their optimal lattice positions, resulting in significant local lattice distortion. This phenomenon has the potential to hinder dislocation motion, thereby yielding high configurational entropy that escalates with temperature. Consequently, HEAs demonstrate elevated strength and reduced plasticity at increased temperatures [44–48]. RHEAs, characterized by their elevated melting points, can manifest superior strength at temperatures surpassing 800°C in comparison to widely employed superalloys. This characteristic positions RHEAs as highly promising alternatives for applications in elevated temperature environments, particularly in turbine blade applications, where they hold the prospect of outperforming Ni-based superalloys. Consequently, the exploration of RHEAs emerges not only as a pursuit with cutting-edge academic value but also as a venture with incalculable economic benefits and strategic significance, as they represent novel and promising candidates extending beyond the capabilities of conventional superalloys [49–54].

Due to the extensive compositional range within HEAs, the intricate phase equilibria governing the high-temperature stability of the alloy remain largely unexplored [55–58].

However, the challenge lies in pinpointing the ideal combination of constituent elements to achieve the desired properties. The conventional trial-and-error method, characterized by prolonged experimentation and limited comprehension of HEA’s intricate structural aspects, proves inefficient. Hence, there arises a pressing need for innovative alloy-design methodologies capable of predicting phases within W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo alloys, thereby streamlining the arduous experimental process. The novelty of this research lies in establishing a two-dimensional mapping (2DM) relationship between atomic size differences and enthalpy mix. This mapping endeavour aims to unveil the phases within non-equiatomic W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEAs across various atomic compositions of each element. Proficiency in discerning phase structures for diverse atomic compositions of elements within W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEAs holds significant potential for guiding the development of HEAs tailored for turbine blade applications. The commonly found alloying elements in HEAs include nickel (Ni), cobalt (Co), titanium (Ti), molybdenum (Mo), and vanadium (V). Numerous HEA systems, such as those based on the CrFeNi composition, have been documented in the literature [59–63]. However, CrFeNi-based HEA systems, while frequently employed for the development of new HEAs, may not possess superior properties that align with industrial requirements. The incorporation of Ni, Co, Mo, and W elements into HEA systems can significantly influence the formation of precipitates, thereby enhancing the mechanical properties [58,64–67].

The pursuit of studying metallurgical properties and advancing materials for industrial technological applications epitomizes a multifaceted endeavour characterized by meticulous inquiry and innovation. Delving into the intricate interplay between material composition and performance, this scholarly pursuit transcends mere exploration, embodying a commitment to pushing the boundaries of scientific understanding and practical utility. Through rigorous experimentation, sophisticated analytical techniques, and mathematical modelling, researchers strive to unravel the intricacies of material behaviour at atomic and macroscopic scales, discerning the fundamental principles governing their mechanical, thermal, and corrosion resistance properties [68–72]. This scholarly quest not only enriches our comprehension of materials science but also underpins the development of HEAs to meet the exacting demands of diverse industrial sectors, thereby fostering technological advancement and driving economic progress. Consequently, the primary aim of this research is to devise an innovative non-equimolar HEA (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) through varied compositions (5–40 at%) of each constituent element.

2 Materials and methods

Owing to its compositional versatility, non-equiatomic HEA systems represent a promising class of alloys, particularly in the context of emerging high-temperature materials. Determining the optimal combination of constituent elements necessary for desired properties poses a challenge. The conventional trial-and-error approach, marked by prolonged periodicity and a limited understanding of the intricate structural features of HEAs, is not recommended. Consequently, there is a need to devise innovative alloy-design methodologies that can predict the phases in W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo alloy, thereby circumventing the cumbersome experimental process. Thus, the principal objective of this research is to forge a 2DM correlation between enthalpy mix and atomic size differences to reveal the phases in non-equimolar W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEAs across varying atomic compositions of each element. Such an approach holds the promise of facilitating alloy design by evaluating phase structures at different atomic compositions within the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEA spectrum, thereby aiding in the attainment of desired properties crucial for high-temperature applications.

Central to this inquiry are key scientific questions concerning the circumstances under which solid solutions or intermetallic (IM) compounds arise in multi-component HEA alloys, addressing both the why and when of such occurrences.

2.1 Conditions for the formation of the single-phase solid solution (SPSS) and IM in HEAs

Criteria for the IM and single-phase formation in HEAs are detailed in Table 1. Both the calculated atomic size difference and enthalpy mix values must meet the requirements for solid solution phases. Merely satisfying the atomic size difference conditions is inadequate for determining the SPSS. Consequently, it is evident that establishing scientifically satisfactory conditions for the SPSS necessitates an understanding of the relationship between atomic size difference and enthalpy mix. From the perspective of HEA design, comprehending the correlation between atomic size difference and thermodynamic parameters requires the development of a 2DM correlating atomic size difference and enthalpy mix [47]. This map serves to distinguish between IM and single-phases in non-equiatomic [W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo] across various atomic percentages of each element. In this research, the prediction of phase types for various compositions of the [W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo] system is facilitated through the development of two-dimensional maps for the parameters atomic size difference (δ) and enthalpy mix (ΔH mix). Utilizing this mapping technique, the phase type can be anticipated for any unknown composition within W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEA systems for high-temperature turbine blades.

Conditions for the formation of the SPSS and IM in HEAs

| Equation number | Equations | Range for solid solution (SS) | Range for IM | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atomic size difference (δ) | δ < 6.5 | δ > 6.5 | [66] |

|

|

||||

| where,

|

||||

|

n is the number of component elements, C

i

and r

i

are compositions and atomic radii of ith element, and

|

||||

| 2 | Enthalpy of mixing (ΔH mix) | −20 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 kJ·mol−1 | ΔH mix < −20 and ΔH mix > 5 | [66] |

|

|

||||

| where

|

Table 2 shows a collection of non-equiatomic HEAs distinguished by diverse compositions within the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) system

Non-equiatomic high entropy alloys (HEA) varied compositions within the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) system

| HEA systems | S. No. | W | RE | NI | CO | MO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HE1 | 1 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 5 | 20 |

| HE2 | 2 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 10 | 20 |

| HE3 | 3 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 20 |

| HE4 | 4 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| HE5 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 25 | 20 |

| HE6 | 6 | 20 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 20 |

| HE7 | 7 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 35 | 20 |

| HE8 | 8 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 40 | 15 |

| HE9 | 9 | 25 | 25 | 5 | 20 | 25 |

| HE10 | 10 | 25 | 25 | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| HE11 | 11 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 20 | 20 |

| HE12 | 12 | 20 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 20 |

| HE13 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 20 | 20 |

| HE14 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 35 | 20 | 15 |

| HE15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 40 | 15 | 15 |

| HE16 | 16 | 25 | 5 | 20 | 25 | 25 |

| HE17 | 17 | 25 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 25 |

| HE18 | 18 | 25 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| HE19 | 19 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| HE20 | 20 | 15 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 15 |

| HE21 | 21 | 15 | 35 | 20 | 15 | 15 |

3 Results and discussion

Table 3 presents the calculated results obtained from the parameters enthalpy mix and atomic size difference, which are computed using equations (1) and (2).

Enthalpy mix and atomic size difference calculations

| HEA | Atomic size difference (δ) | Enthalpy (ΔH mix) kJ·mol−1 |

|---|---|---|

| HE1 | 2.40 | −23.62 |

| HE2 | 2.40 | −23.12 |

| HE3 | 2.40 | −21.48 |

| HE4 | 2.26 | −19.57 |

| HE5 | 2.26 | −17.99 |

| HE6 | 2.26 | −17.77 |

| HE7 | 2.11 | −16.15 |

| HE8 | 1.96 | −12.93 |

| HE9 | 2.40 | −21.45 |

| HE10 | 2.40 | −19.57 |

| HE11 | 2.40 | −21.03 |

| HE12 | 2.26 | −18.40 |

| HE13 | 2.26 | −18.59 |

| HE14 | 2.11 | −17.45 |

| HE15 | 1.96 | −13.53 |

| HE16 | 1.79 | −14.61 |

| HE17 | 1.96 | −16.36 |

| HE18 | 2.11 | −17.52 |

| HE19 | 2.40 | −19.70 |

| HE20 | 2.40 | −19.26 |

| HE21 | 2.53 | −20.61 |

| HE22 | 2.53 | −16.90 |

| HE23 | 2.40 | −15.88 |

| HE24 | 2.40 | −17.77 |

| HE25 | 2.40 | −19.70 |

| HE26 | 2.26 | −21.00 |

| HE27 | 2.26 | −22.82 |

| HE28 | 2.11 | −21.77 |

| HE29 | 1.96 | −22.58 |

| HE30 | 1.96 | −18.85 |

| HE31 | 2.11 | −20.22 |

| HE32 | 2.26 | −19.98 |

| HE33 | 2.40 | −19.31 |

| HE34 | 2.65 | −22.01 |

| HE35 | 2.65 | −20.89 |

| HE36 | 2.77 | −21.21 |

3.1 Impact of rhenium atomic percentage in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA

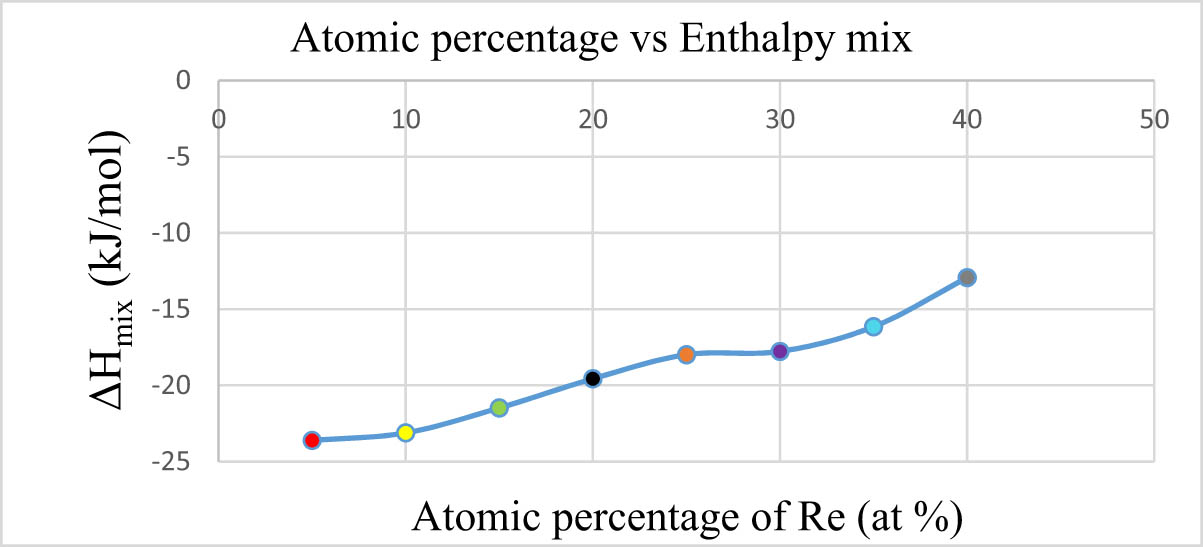

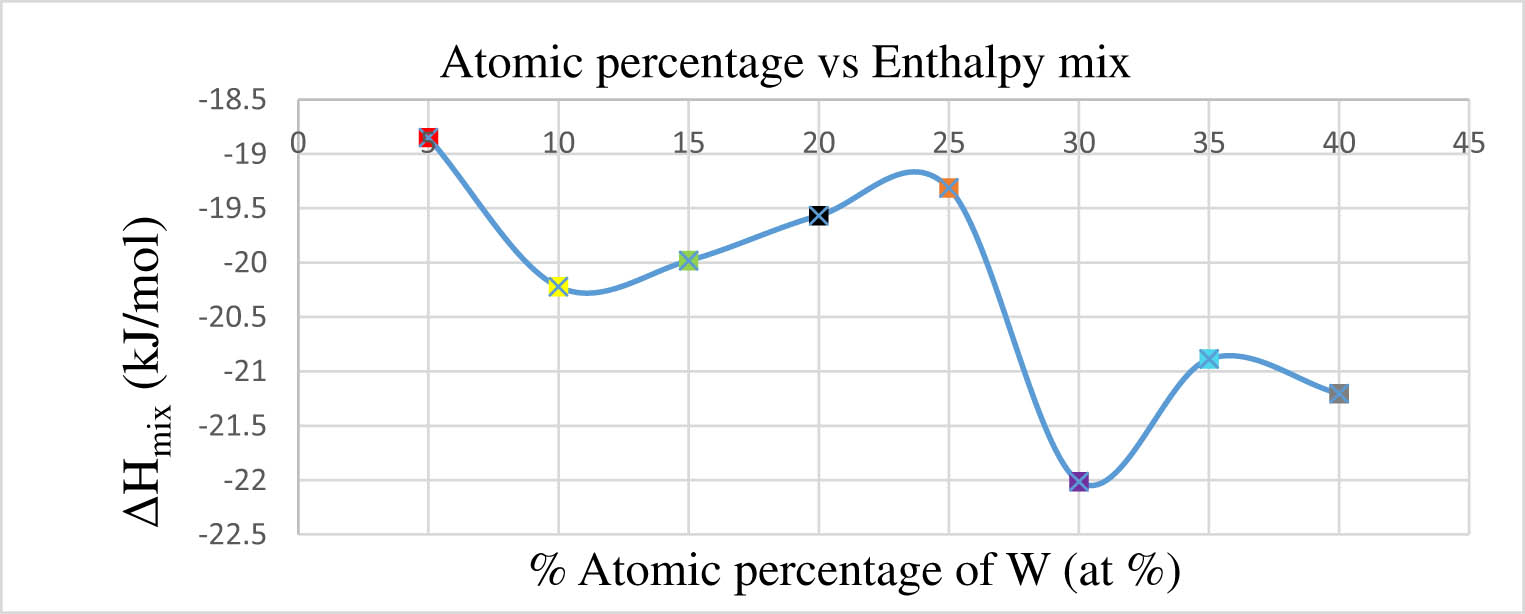

Table 4 displays the symbol values corresponding to Figure 1 for the HEA systems 1–8 series, illustrating the fluctuations in rhenium atomic percentages.

Rhenium atomic percentage fluctuations in HEA systems

| Symbol of HEAs | HEAs | W | Re | Co | Mo | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HE1 | 20 | 5 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

|

HE2 | 20 | 10 | 25 | 25 | 20 |

|

HE3 | 20 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 20 |

|

HE4 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

|

HE5 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 20 |

|

HE6 | 15 | 30 | 25 | 15 | 15 |

|

HE7 | 15 | 35 | 20 | 15 | 15 |

|

HE8 | 10 | 40 | 20 | 10 | 20 |

Impact of the rhenium atomic percentage on enthalpy mix.

Table 4 illustrates the variation in rhenium atomic percentages (5–40 at%) across the HEA series.

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of varying atomic percentages of rhenium on the enthalpy mix in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) alloy. As the rhenium atomic percentage ranges from 5 to 40 at%, there is an observable increase in the enthalpy mix values. At the elevated atomic percentage of rhenium, enthalpy mixing values satisfy the criteria (−20 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 kJ·mol−1) for the formation of an SPSS, whereas at lower rhenium atomic percentages, the enthalpy mixing values do not satisfy the criteria (−20 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 kJ·mol−1) for the attainment of an SPSS.

The strengthening of the Laves phase, which is an IM phase, contributes to the enhancement of the properties of HEAs [61]. This strengthening effect is particularly notable at higher atomic percentages of rhenium. The Laves phase reinforcement is known to improve the mechanical properties of the alloy, making it more durable and resistant to deformation. The less favourable enthalpy mix indicates a heightened bond among the alloying elements. This enhanced bonding is advantageous for designing IM compounds, which may exhibit unique and desirable properties. Understanding the enthalpy mixing of main components in HEAs is crucial for characterizing their chemical interactions [73], which ultimately influence the alloy’s properties and performance. In essence, how variations in rhenium content influence the enthalpy mixing values, which in turn impact the properties and performance of HEA systems. It also underscores the importance of considering these factors in the design and development of advanced alloy materials.

3.2 Influence of nickel atomic percentage in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo)

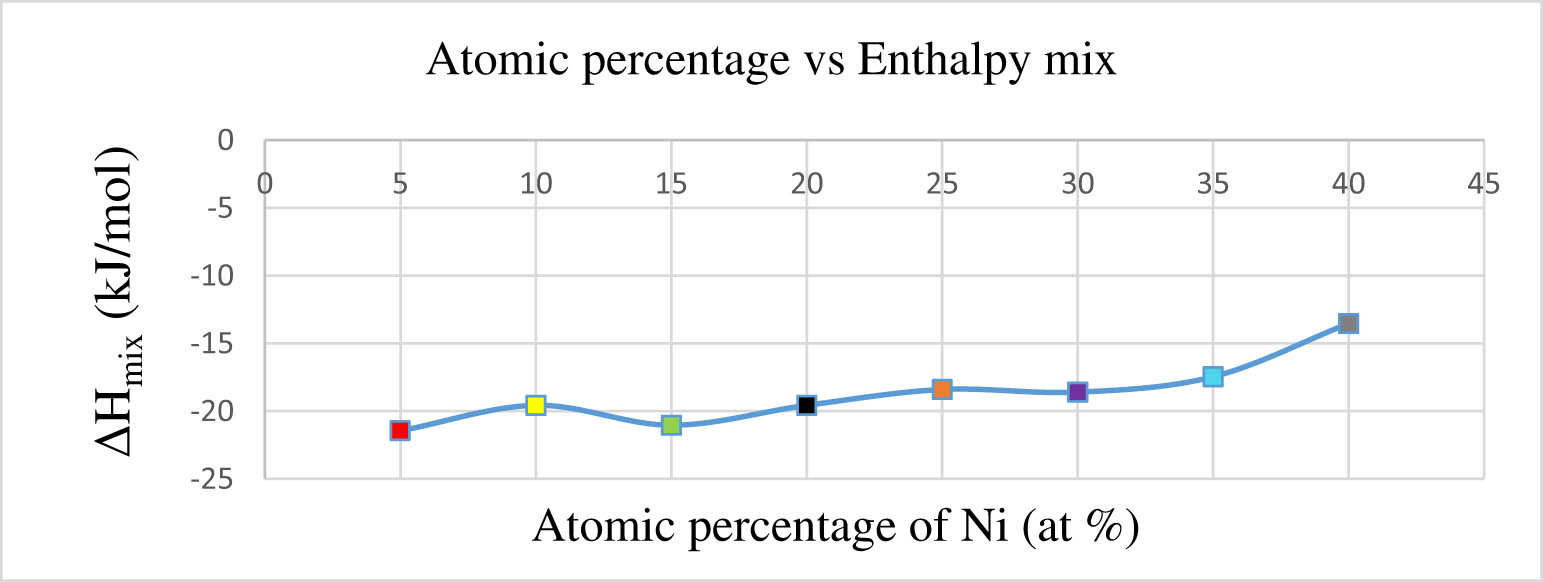

Table 5 displays the symbol values corresponding to Figure 2, indicating the fluctuation in nickel atomic percentages ranging from 5 to 40 at%.

Nickel atomic percentage fluctuations in HEA systems

| Symbols | HEA systems | Re | Ni | Co | Mo | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H9 | 25 | 5 | 25 | 25 | 20 |

|

H10 | 25 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 25 |

|

H11 | 20 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 20 |

|

H12 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 20 |

|

H13 | 15 | 30 | 25 | 15 | 15 |

|

H14 | 15 | 35 | 20 | 15 | 15 |

|

H15 | 20 | 40 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

Impact of varying nickel atomic percentage on the enthalpy mix.

Table 5 elucidates that within the HEA 9 to HEA 15 series, there is a discernible range in the atomic percentages of nickel, spanning from 5 to 40 at%.

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of nickel atomic percentage on the enthalpy mix in (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo). As the nickel atomic percentage varies from 5 to 40 at%, the enthalpy mix value demonstrates an increase. The maximum enthalpy mix value is observed at a 40 at% of nickel, meeting the criteria for SPSS. However, at minor nickel atomic percentages, specifically below 40 at%, the enthalpy mix values are measured at −21.45 kJ·mol−1, failing to meet the specified criteria (Table 1). Nickel has a tendency to segregate into dendritic areas, resulting in the emergence of Laves within the phases of the HEA. This precipitation of the Laves phase brings about substantial changes in the features of the HEA.

3.3 Influence of cobalt atomic percentage in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA

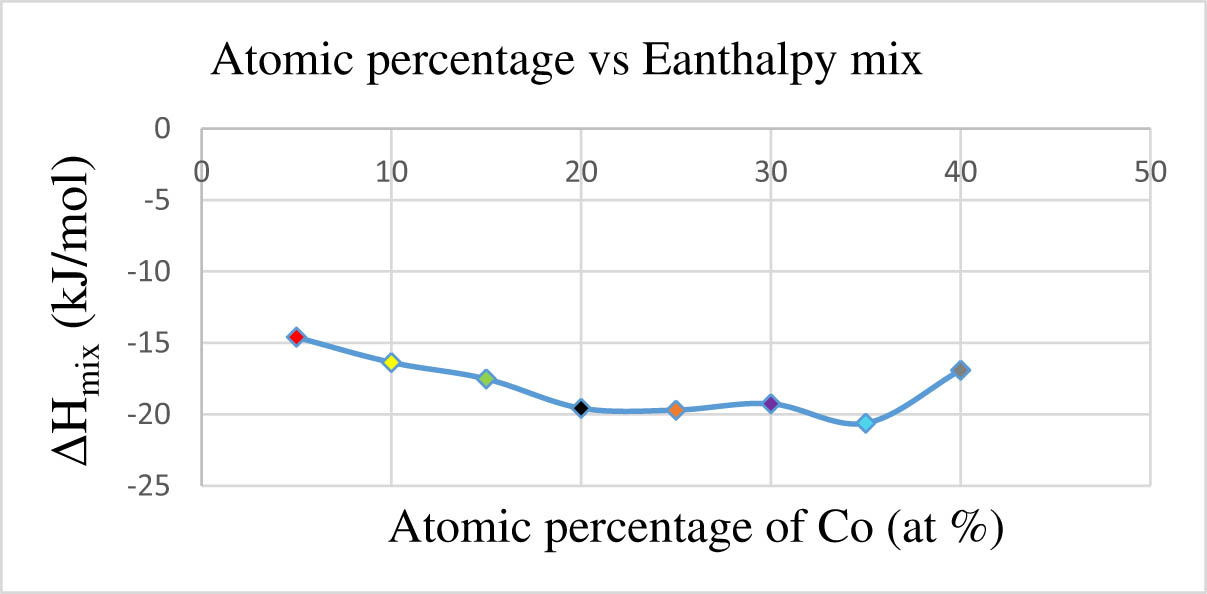

Table 6 displays the symbol values corresponding to Figure 3, illustrating fluctuation in atomic percentages of cobalt within the range of 5–40 at%.

Cobalt atomic percentage fluctuations in HEA systems

| Symbols | HEA | Re | Ni | Co | Mo | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H16 | 25 | 25 | 5 | 25 | 20 |

|

H17 | 25 | 20 | 10 | 25 | 20 |

|

H18 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 20 | 20 |

|

H19 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 20 |

|

H20 | 25 | 15 | 30 | 15 | 15 |

|

H21 | 20 | 15 | 35 | 15 | 15 |

|

H22 | 20 | 20 | 40 | 10 | 10 |

Influence of cobalt atomic percentage on ΔH mix.

Table 6 presents a detailed breakdown of the atomic percentages of cobalt across various compositions denoted by different symbols. The compositions are characterized by their atomic percentages of cobalt ranging from 5% to 40%, with the remaining percentages distributed among other elements such as HEA, Re, Ni, Mo, and W. It exhibits a systematic variation in atomic percentages of cobalt across different compositions, allowing for a thorough exploration of its impact on material properties. The compositions are arranged in ascending order of cobalt content, providing a clear progression for analysis. Concurrently, the enthalpy mix values corresponding to each composition are provided, elucidating the thermodynamic stability and energy characteristics associated with the different cobalt concentrations. The enthalpy mix values serve as crucial indicators of the material’s behaviour under specific conditions.

By examining the enthalpy mix values across the range of cobalt percentages, notable trends emerge. It becomes evident that variations in the atomic percentage of cobalt directly affect the enthalpy mix values, with higher cobalt concentrations generally resulting in lower enthalpy mix values. This suggests a significant influence of cobalt content on the overall energy landscape and stability of the material. Of particular interest is the observation that the highest enthalpy mix value occurs at 5 at% of cobalt. This underscores the intricate interplay between cobalt and other alloying elements, such as cobalt, in determining the material’s thermodynamic properties. Such insights are crucial for tailoring compositions to achieve desired performance characteristics.

The consistency of enthalpy mix values with the SPSS condition, as outlined in Table 1, underscores the reliability and relevance of this criterion in guiding material design and selection. This consistency across different cobalt percentages reaffirms the robustness of the SPSS criterion in predicting material behaviour like thermodynamic stability and energy characteristics of the materials, facilitating informed decision-making in material design and engineering applications. Moreover, referring to Figure 3, which presumably illustrates the relationship between atomic percentage of cobalt and enthalpy mix values, it is evident that the enthalpy mix values consistently adhere to the SPSS condition across all atomic percentage ranges of cobalt.

3.4 Influence of atomic percentage of molybdenum in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA

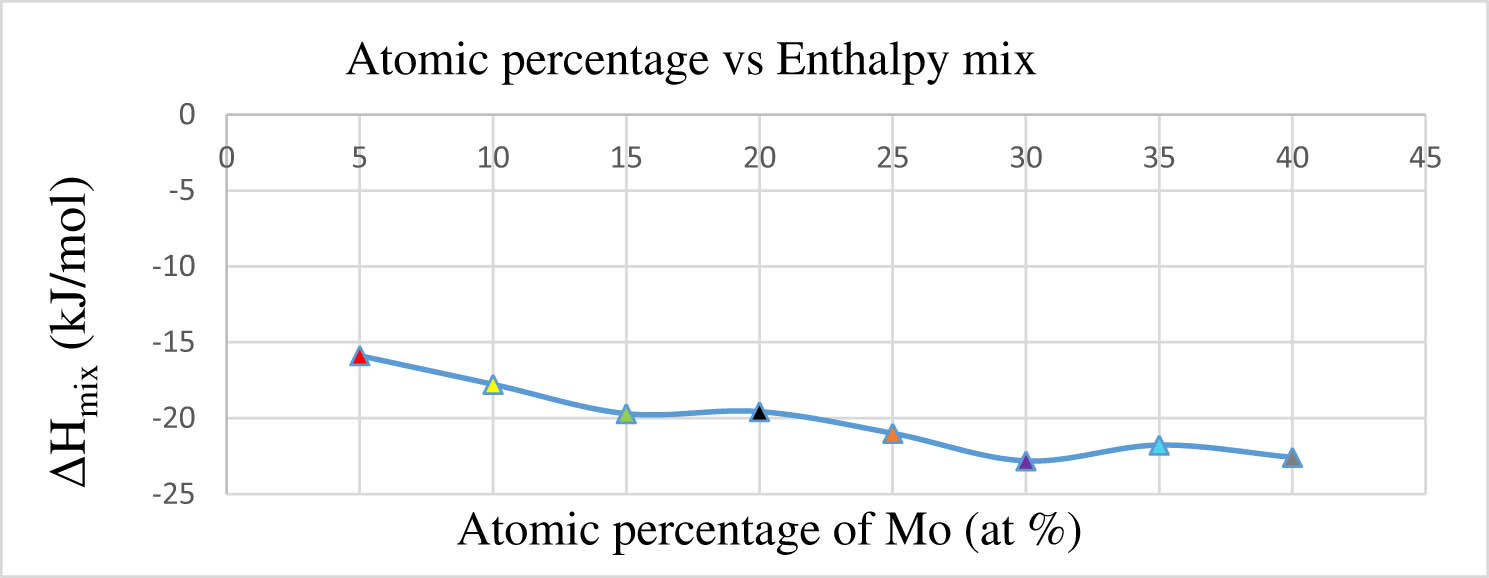

Table 7 elucidates the changes in atomic percentages of molybdenum, ranging from 5 to 40%.

Atomic percentage changes of molybdenum in HEA systems

| Symbols | HEA | Re | Ni | Co | Mo | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H23 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 5 | 20 |

|

H24 | 25 | 20 | 25 | 10 | 20 |

|

H25 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 20 |

|

H26 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 20 |

|

H27 | 15 | 15 | 25 | 30 | 15 |

|

H28 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 35 | 15 |

|

H29 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 40 | 10 |

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of the atomic percentage of molybdenum on the enthalpy mix in W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo alloy. As the atomic percentage of molybdenum fluctuates from 5 to 40 at%, there is a corresponding decrease in the enthalpy mix value.

Impact of atomic percentage of molybdenum on enthalpy mix.

The enthalpy mixing value shows a decline with higher atomic percentages of molybdenum, with similar results observed in experiments conducted by other researchers investigating HEAs [53].

The maximum enthalpy mix value is identified at 5 at% of molybdenum, aligning with the ΔH mix criterion specified for SPSS, as outlined in Table 1. The graphical representation in Figure 4 reveals that enthalpy mix values conform to the SPSS condition for the varied atomic percentages of molybdenum. However, at higher atomic percentages of molybdenum in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA, the enthalpy mix values fail to meet the condition, as indicated in Table 1. When there are increased atomic percentages of molybdenum in HEA, molybdenum tends to precipitate and leads to Laves formation in HEA. As depicted in Figure 4, it becomes evident that at lower atomic percentages of molybdenum, the enthalpy mix value is large. In contrast, Lave effects become apparent at large atomic percentages of molybdenum in HEA.

3.5 Influence of tungsten atomic percentage in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA

Table 8 displays the symbol values corresponding to Figure 5, illustrating the fluctuation in atomic percentages of tungsten within the range of 5–40 at%.

Tungsten atomic percentage fluctuations in HEA systems

| Symbols | HEA | Re | Ni | Co | Mo | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HE30 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 5 |

|

HE31 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 10 |

|

HE32 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 |

|

HE33 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 25 |

|

HE34 | 15 | 15 | 25 | 15 | 30 |

|

HE35 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 15 | 35 |

|

HE36 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 40 |

Impact of tungsten atomic percentage on enthalpy mix.

Table 8 illustrates the fluctuation in atomic percentages of tungsten (ranging from 5 to 40 at%).

From the data provided in Table 8, it is evident that there is a range of atomic percentages for tungsten across different compositions of the HEA, with values varying from 5 to 40% in W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo alloy. Furthermore, it is indicated that there is a fluctuation in the atomic percentages of tungsten in the alloy, and this fluctuation has an impact on the enthalpy mix of the alloy. This impact is elucidated in Figure 5, which illustrates how the atomic percentage of tungsten influences the enthalpy mix in the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo alloy. According to the description, the enthalpy mix values exhibit a decline as the atomic percentage of tungsten varies from 5 to 40%. The peak enthalpy mix value is observed at 5 at% of tungsten, meeting a specified criterion for the formation of a special solid solution (SPSS), as mentioned in Table 1. The enthalpy mixing value shows a decline with higher atomic percentages of tungsten, with similar results observed in experiments conducted by other researchers investigating HEAs [74].

Figure 5 provides a visual representation of this relationship, showing how the enthalpy mix values change with varying atomic percentages of tungsten. It demonstrates that the enthalpy mix values satisfy the SPSS condition for different atomic percentages of tungsten in the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEA. Additionally, the examination of Figure 5 indicates that at minor atomic percentages of tungsten within the HEA, the enthalpy mix values do not meet the specified condition, as outlined in Table 1. This suggests that certain compositions of the alloy may not exhibit the desired properties unless the atomic percentage of tungsten is within a certain range.

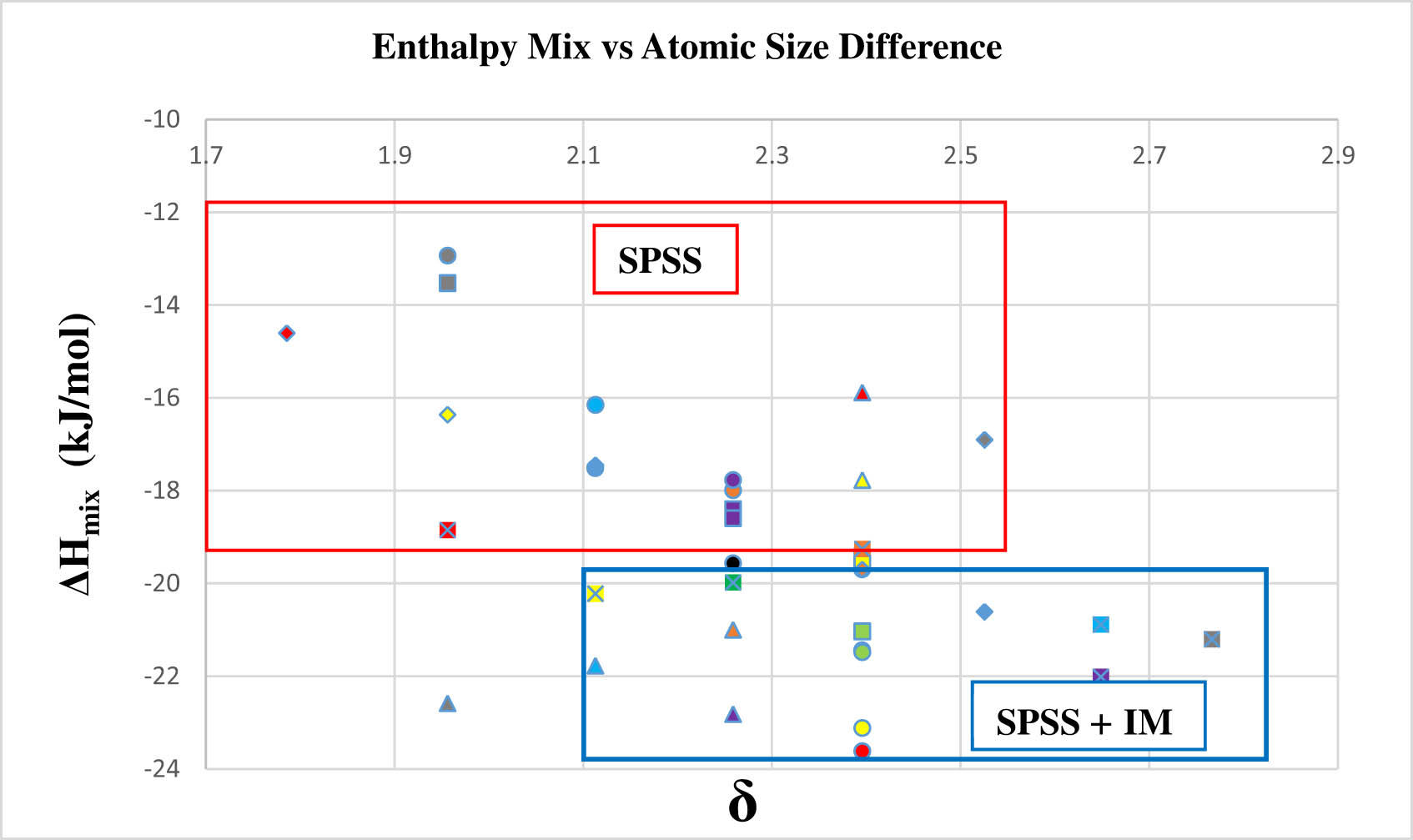

3.6 2DM for the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo alloy

The primary objective of the present research is to forecast the phases in an innovative non-equiatomic HEA comprising W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo across different compositions. A crucial metallurgical aspect of the non-equiatomic HEA lies in understanding the correlation between atomic size differences and the enthalpy mix, which aids in distinguishing the phases in the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo alloy. It is imperative to elucidate the association between atomic size differences and thermodynamic parameters. Developing a 2DM for associating atomic size differences and enthalpy mix is essential for distinguishing the phase formations in the [W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo] alloy across different atomic percentages of each element.

In this current research endeavour, the anticipation of phase types within the range of non-equiatomic [W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo] HEA compositions, considering varying atomic percentages for each element, involved the creation of 2DM for the specified parameters.

3.6.1 Enthalpy mix (ΔH mix) vs atomic size difference (δ)

By employing a 2DM of parameters, the prediction of phase types becomes possible for any unidentified composition within the W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEA systems. This capability holds significant promise for alloy design, facilitating the attainment of specific properties tailored to meet the requirements of industrial applications. The ability to assess phase structures in non-equiatomic systems of W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo HEA represents a valuable asset in optimizing alloy design for the realization of desired industrial properties.

3.6.2 2DM between enthalpy mix (ΔH mix) vs atomic size difference (δ)

The correlation between (ΔH mix) vs (δ) depicted in Figure 6, through a 2DM, furnishes extensive data for the classification and identification of stability regions within HEA systems. These regions are delineated as SPSS, SPSS + IM, or IM, offering a comprehensive understanding of the alloy’s stability characteristics.

2D mapping: enthalpy mix vs atomic size difference.

The criterion for SPSS formation is (δ) < 6.5, and the ΔH mix value should be between −20 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 kJ·mol−1. The requirement for SPSS + IM formation is (δ) < 6.5, and the ΔH mix value should be such that ΔH mix is less than −20. The criterion for IM formation: The atomic size disparity (δ) should exceed 6.5, and the enthalpy mixing condition must be such that ΔH mix is less than −20.

Therefore, the genesis of the SPSS or IM phase is contingent upon the disparity in atomic sizes (δ) and the prevailing conditions of enthalpy mixing. A perpetual rivalry exists between the atomic size differential and the enthalpy mixing, determining the ultimate establishment of either SPSS or IM. Consequently, the interplay between atomic size variance and enthalpy mixing governs the manifestation of IM or SPSS.

When the atomic size difference attains a considerable magnitude, it gives rise to a disproportionate strain energy. Simultaneously, an additional pronounced negative ΔH mix facilitates the IM compound formation.

Table 3 illustrates that the atomic size difference values meet the criterion (δ < 6.5) (refer to Table 1) across all atomic percentages within the HEA. This phenomenon is ascribed to the closely aligned atomic radii of W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo elements in HEA, resulting in a diminished atomic size difference. The reduced atomic-size difference consequently results in less strain energy within the crystal lattice, facilitating the interchangeability of elements and an equal likelihood of occupying lattice sites to form a (SPSS). It is crucial, however, to recognize that adherence to atomic size difference requirements alone does not suffice for determining the formation of (SPSS). Consideration must also be given to enthalpy mix effects, in conjunction with the impacts of atomic size difference, in the process of (SPSS) formation.

For varying atomic percentages ranging from 5 to 40% of nickel and rhenium in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA, the highest enthalpy mix values are observed at elevated atomic percentages. These values conform to the ΔH mix criterion (−20 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 kJ·mol−1) essential for the generation of the SPSS. Conversely, at lower atomic percentages of rhenium and nickel, the enthalpy mix values fail to meet the specified condition, primarily due to their notably more negative values, as illustrated in Table 1. The heightened negativity of the enthalpy mix imparts a more robust binding force among the elements, facilitating the formation of IM compounds in conjunction with the SPSS.

Across the diverse atomic percentages of nickel in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) alloy, the computed values for both enthalpy mix and atomic size difference consistently meet the specified conditions outlined in Table 1, facilitating the formation of SPSS.

For varying concentrations of molybdenum and tungsten in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA, the maximum enthalpy mix value is observed at lower atomic percentages. This alignment fulfils the ΔH mix criteria (−20 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 kJ·mol−1) necessary for the SPSS formation. Conversely, at large atomic percentages of molybdenum and tungsten in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA, the enthalpy mix values do not meet the specified condition due to their more negative values, as depicted in Table 1.

4 Conclusions

SPSS formation is contingent upon satisfying both the atomic size difference and ΔH mix criteria (Table 1).

In (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEAs, an elevated atomic percentage of nickel and rhenium leads to the fulfilment of conditions stipulated for the formation of SPSS, as observed in both enthalpy mix values and atomic size difference values.

For reduced atomic percentages of nickel and rhenium in (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) alloy, the atomic size difference adheres to the specified condition (δ < 6.5). Nevertheless, the ΔH mix results fail to encounter the criteria (−20 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 kJ·mol−1), leading to the emergence of an IM + SPSS configuration.

For diminished atomic percentages of tungsten and molybdenum within the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA, both the enthalpy mix values and the atomic size difference values conform to the prescribed conditions, facilitating the formation of SPSS.

With an increased atomic percentage of tungsten and molybdenum in the (W–Re–Ni–Co–Mo) HEA, the values of atomic size difference adhere to the specified condition (δ < 6.5).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to the Director of Manipal Institute of Technology Bengaluru, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) Bengaluru Campus for his unwavering support and financial assistance towards their research endeavors.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Gokul Udayakumaran, Thirugnanasambantham Krishnamoorthy Gandhi; Methodology: Gokul Udayakumaran, Ramesh Raju, Ram Bansal; Investigation: Gokul Udayakumaran Thirugnanasambantham Krishnamoorthy Gandhi, Ramesh Raju, Ram Bansal, Vidhya Barpha; Formal Analysis: Jyoti Kukade, Vidhya Barpha, Kuldeep Kumar Saxena, Soumyashree M. Panchal; Resources: Ramesh Raju, Ram Bansal, Kuldeep Kumar Saxena, Soumyashree M. Panchal, Basireddy Bhavani; Software: Jyoti Kukade, Vidhya Barpha; Validation: Basireddy Bhavani, Kuldeep Kumar Saxena, Soumyashree M. Panchal; Writing – Original Draft: Gokul Udayakumaran, Thirugnanasambantham Krishnamoorthy Gandhi, Vidhya Barpha; Writing – Review and Editing: Ramesh Raju, Ram Bansal, Jyoti Kukade, Soumyashree M. Panchal, Basireddy Bhavani.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] SudhirSastry, Y. B., P. R. Budarapu, N. Madhavi, and Y. Krishna. Buckling analysis of thin wall stiffened composite panels. Computational Materials Science, Vol. 96, 2015, pp. 459–471.10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.06.007Search in Google Scholar

[2] Sastry, Y. B. S., P. R. Budarapu, Y. Krishna, and S. Devaraj. Studies on ballistic impact of the composite panels. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 72, 2014, pp. 2–12.10.1016/j.tafmec.2014.07.010Search in Google Scholar

[3] Raji, A., J. I. E. T. Nesakumar, S. Mani, S. Perumal, V. Rajangam, S. Thirunavukkarasu, et al. Biowaste-originated heteroatom-doped porous carbonaceous material for electrochemical energy storage application. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, Vol. 98, 2021, pp. 308–317.10.1016/j.jiec.2021.03.037Search in Google Scholar

[4] Singh, B., I. Kumar, K. K. Saxena, K. A. Mohammed, M. I. Khan, S. B. Moussa, et al. A future prospects and current scenario of aluminium metal matrix composites characteristics. Alexandria Engineering Journal, Vol. 76, 2023, pp. 1–17.10.1016/j.aej.2023.06.028Search in Google Scholar

[5] Devi, M. D., A. V. Juliet, K. Hariprasad, V. Ganesh, H. E. Ali, H. Algarni, et al. Improved UV Photodetection of Terbium-doped NiO thin films prepared by cost-effective nebulizer spray technique. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, Vol. 127, 2021, id. 105673.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Basavapoornima, C., C. R. Kesavulu, T. Maheswari, W. Pecharapa, S. R. Depuru, and C. K. Jayasankar. Spectral characteristics of Pr3+ -doped lead based phosphate glasses for optical display device applications. Journal of Luminescence, Vol. 228, 2020, id. 117585.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Gupta, T. K., P. R. Budarapu, S. R. Chappidi, S. S. YB, M. Paggi, and S. P. Bordas. Advances in carbon based nanomaterials for bio-medical applications. Current Medicinal Chemistry, Vol. 26, No. 38, 2019, pp. 6851–6877.10.2174/0929867326666181126113605Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Numan, A., A. A. Gill, S. Rafique, M. Guduri, Y. Zhan, B. Maddiboyina, et al. Rationally engineered nanosensors: A novel strategy for the detection of heavy metal ions in the environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 409, 2021, id. 124493.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124493Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Vijayakumar, Y., P. Nagaraju, V. Yaragani, S. R. Parne, N. S. Awwad, and M. R. Reddy. Nanostructured Al and Fe co-doped ZnO thin films for enhanced ammonia detection. Physica B: Condensed Matter, Vol. 581, 2020, id. 411976.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Budarapu, P. R., S. S. Yb, B. Javvaji, and D. R. Mahapatra. Vibration analysis of multi-walled carbon nanotubes embedded in elastic medium. Frontiers of Structural and Civil Engineering, Vol. 8, 2014, pp. 151–159.10.1007/s11709-014-0247-9Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yue, L., M. Jayapal, X. Cheng, T. Zhang, J. Chen, X. Ma, et al. Highly dispersed ultra-small nano Sn-SnSb nanoparticles anchored on N-doped graphene sheets as high performance anode for sodium ion batteries. Applied Surface Science, Vol. 512, 2020, id. 145686.10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.145686Search in Google Scholar

[12] Goud, J. S., P. Srilatha, R. V. Kumar, K. T. Kumar, U. Khan, Z. Raizah, et al. Role of ternary hybrid nanofluid in the thermal distribution of a dovetail fin with the internal generation of heat. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, Vol. 35, 2022, id. 102113.10.1016/j.csite.2022.102113Search in Google Scholar

[13] Girish, K. M., S. C. Ramachandra Naik, H. Prashantha, H. P. Nagabhushana, K. S. Nagaswarupa, H. B. Anantha Raju, et al. Zn2TiO4: Eu3+ nanophosphor: self explosive route and its near UV excited photoluminescence properties for WLEDs. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, Vol. 138, 2015, pp. 857–865.10.1016/j.saa.2014.10.097Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Girish, K. M., S. C. Prashantha, H. Nagabhushana, C. R. Ravikumar, H. P. Nagaswarupa, R. Naik, et al. Multi-functional Zn2TiO4: Sm3+ nanopowders: excellent performance as an electrochemical sensor and an UV photocatalyst. Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices 3, Vol. 2, 2018, pp. 151–160.10.1016/j.jsamd.2018.02.001Search in Google Scholar

[15] Rathod, V. P. and S. Tanveer. Pulsatile flow of couple stress fluid through a porous medium with periodic body acceleration and magnetic field. Bulletin of the Malaysian Mathematical Sciences Society, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Alrobei, H., M. K. Prashanth, C. R. Manjunatha, C. B. Pradeep Kumar, C. P. Chitrabanu, P. D. Shivaramu, et al. Adsorption of anionic dye on eco-friendly synthesised reduced graphene oxide anchored with lanthanum aluminate: Isotherms, kinetics and statistical error analysis. Ceramics International, Vol. 47, No. 7, 2021, pp. 10322–10331.10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.07.251Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hora, S. K., P. Rachana, R. P. De Prado, M. Wozniak, and P. B. Divakarachari. Long short-term memory network-based metaheuristic for effective electric energy consumption prediction. Applied Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 23, 2021, id. 11263.10.3390/app112311263Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kota, V. R. and M. N. Bhukya. A novel global MPP tracking scheme based on shading pattern identification using artificial neural networks for photovoltaic power generation during partial shaded condition. IET Renewable Power Generation, Vol. 13, No. 10, 2019, pp. 1647–1659.10.1049/iet-rpg.2018.5142Search in Google Scholar

[19] Dhanalaxmi, B., G. A. Naidu, and K. Anuradha. Adaptive PSO based association rule mining technique for software defect classification using ANN. Procedia Computer Science, Vol. 46, 2015, pp. 432–442.10.1016/j.procs.2015.02.041Search in Google Scholar

[20] Reddy, K. S. P., Y. M. Roopa, K. R. LN, and N. S. Nandan. IoT based smart agriculture using machine learning. In 2020 Second International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), IEEE, 2020, July, pp. 130–134.10.1109/ICIRCA48905.2020.9183373Search in Google Scholar

[21] Sastry, M. N. P., K. Devaki Devi, and D. Bandhu. Characterization of Aegle Marmelos fiber reinforced composite. International Journal of Engineering Research, Vol. 5, No. SP 2, 2016, pp. 345–349.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Bhardwaj, A. R., A. M. Vaidya, P. D. Meshram, and D. Bandhu. Machining behavior investigation of aluminium metal matrix composite reinforced with TiC particulates. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), Vol. 64, 2023, No. 1/2, pp. 1–15.10.1007/s12008-023-01378-6Search in Google Scholar

[23] SudhirSastry, Y. B., Y. Krishna, and R. B. Pattabhi. Parametric studies on buckling of thin walled channel beams. Computational Materials Science, Vol. 96, 2015, pp. 416–424.10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.07.058Search in Google Scholar

[24] Lakshmi, L., M. P. Reddy, C. Santhaiah, and U. J. Reddy. Smart phishing detection in web pages using supervised deep learning classification and optimization technique adam. Wireless Personal Communications, Vol. 118, No. 4, 2021, pp. 3549–3564.10.1007/s11277-021-08196-7Search in Google Scholar

[25] Padmaja, B., V. R. Prasad, and K. V. N. Sunitha. A machine learning approach for stress detection using a wireless physical activity tracker. International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2018, pp. 33–38.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Reddy, P. V., B. V. Reddy, and P. S. Rao. A numerical study on tube hydroforming process to optimize the process parameters by Taguchi method. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 5, No. 11, 2018, pp. 25376–25381.10.1016/j.matpr.2018.10.341Search in Google Scholar

[27] Dhanalaxmi, B. and G. A. Naidu. A survey on design and analysis of robust IoT architecture. 2017 International Conference on Innovative Mechanisms for Industry Applications (ICIMIA), IEEE, 2017, February, pp. 375–378.10.1109/ICIMIA.2017.7975639Search in Google Scholar

[28] Vijayakumar, Y., P. Nagaraju, V. Yaragani, S. R. Parne, N. S. Awwad, and M. V. Ramana Reddy. Nanostructured Al and Fe co-doped ZnO thin films for enhanced ammonia detection. Physica B: Condensed Matter, Vol. 581, 2020, id. 411976.10.1016/j.physb.2019.411976Search in Google Scholar

[29] Alnaeli, M., M. Alnajideen, R. Navaratne, H. Shi, P. Czyzewski, P. Wang, et al. High-temperature materials for complex components in ammonia/hydrogen gas turbines: a critical review. Energies, Vol. 16, 2023, id. 6973.10.3390/en16196973Search in Google Scholar

[30] Bohidar, S. K., R. Dewangan, and K. Kaurase. Advanced materials used for different components of gas turbine. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), Vol. 1, No. 7, 2013, pp. 366–370.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ramprasad, P., C. Basavapoornima, S. R. Depuru, and C. K. Jayasankar. Spectral investigations of Nd3 +: Ba (PO3) 2 + La2O3 glasses for infrared laser gain media applications. Optical Materials, Vol. 129, 2022, id. 112482.10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112482Search in Google Scholar

[32] Parashuram, L., S. Sreenivasa, S. Akshatha, and V. Udayakumar. A non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor based on ZrO2: Cu (I) nanosphere modified carbon paste electrode for electro-catalytic oxidative detection of glucose in raw Citrus aurantium var. sinensis. Food Chemistry, Vol. 300, 2019, id. 125178.10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125178Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Kumari, S., B. Nakum, D. Bandhu, and K. Abhishek. Multi-attribute group decision making (MAGDM) using fuzzy linguistic modeling integrated with the VIKOR method for car purchasing model. International Journal of Decision Support System Technology (IJDSST), Vol. 14, No. 1, 2022, pp. 1–20.10.4018/IJDSST.286185Search in Google Scholar

[34] Dinbandhu, J. M., and K. Abhishek. Parametric optimization and evaluation of RMDTM welding performance for ASTM A387 grade 11 steel plates using TOPSIS-Taguchi approach. International Conference on Advances in Materials Processing & Manufacturing Applications, Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2020, pp. 215–227.10.1007/978-981-16-0909-1_22Search in Google Scholar

[35] Francis, A., K. G. Thirugnanasambantham, R. Ramesh, M. V. Roshan, and M. Kumar. High-temperature erosion and its mechanisms of IN-738 superalloy under hot air jet conditions. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), Vol. 497, 2022, No. 1–2, pp. 1–7.10.1007/s12008-022-01013-wSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Basavapoornima, C., C. R. Kesavulu, T. Maheswari, W. Pecharapa, S. Rani Depuru, and C. K. Jayasankar. Spectral characteristics of Pr3+ -doped lead based phosphate glasses for optical display device applications. Journal of Luminescence, Vol. 228, 2020, id. 117585.10.1016/j.jlumin.2020.117585Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kumari, S., D. Bandhu, A. Kumar, R. K. Yadav, and K. Vivekananda. Application of utility function approach aggregated with imperialist competitive algorithm for optimization of turning parameters of AISI D2 Steel. In Recent Advances in Mechanical Infrastructure: Proceedings of ICRAM 2019, Springer Singapore, 2020, pp. 49–57.10.1007/978-981-32-9971-9_6Search in Google Scholar

[38] Bhukya, M. N., V. Reddy Kota, and S. Rani Depuru. A simple, efficient, and novel standalone photovoltaic inverter configuration with reduced harmonic distortion. IEEE access, Vol. 7, 2019, pp. 43831–43845.10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2902979Search in Google Scholar

[39] Thirugnanasambantham, K. G., A. Francis, R. Ramesh, and M. K. Reddy. Investigation of erosion mechanisms on IN-718 based turbine blades under water jet conditions. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), Vol. 225, 2022, No. 1, pp. 1–6.10.1007/s12008-022-00910-4Search in Google Scholar

[40] Jiang, H., J. X. Dong, M. C. Zhang, and Z. Yao. Development of typical hard- to-deform nickel-base superalloy for turbine disk served above 800°C. Aeronautical Manufacturing Technology, Vol. 64, No. 1/2, 2021, pp. 62–73 (in Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[41] Ravikumar, J., S. Subramani, D. Dillikannan, Y. Devarajan, L. Thangavelu, M. Nedunchezhiyan, et al. Multi-objective optimization of performance and emission characteristics of a CRDI diesel engine fueled with sapota methyl ester/diesel blends. Energy, Vol. 250, 2022, id. 123709.10.1016/j.energy.2022.123709Search in Google Scholar

[42] Jaidass, N., C. Krishna Moorthi, A. Mohan Babu, and M. Reddi Babu. Luminescence properties of Dy3+ doped lithium zinc borosilicate glasses for photonic applications. Heliyon, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2018, pp. 184–190.10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00555Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Kumar, K. Y., H. Saini, D. Pandiarajan, M. K. Prashanth, L. Parashuram, and M. S. Raghu. Controllable synthesis of TiO2 chemically bonded graphene for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and dye degradation. Catalysis Today, Vol. 340, 2020, pp. 170–177.10.1016/j.cattod.2018.10.042Search in Google Scholar

[44] Sohn, S. S., A. K. D. Silva, Y. Ikeda, F. Körmann, W. Lu, W. S. Choi, et al. Ultrastrong medium-entropy single- phase alloys designed via severe lattice distortion. Advanced Materials, Vol. 31, 2019, id. 1807142.10.1002/adma.201807142Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Ma, E. Unusual dislocation behavior in high-entropy alloys. Scripta Materialia, Vol. 181, 2020, pp. 127–133.10.1016/j.scriptamat.2020.02.021Search in Google Scholar

[46] Naik, R., S. C. Prashantha, and H. Nagabhushana. Effect of Li+ codoping on structural and luminescent properties of Mg2SiO4: RE3+ (RE = Eu, Tb) nanophosphors for displays and eccrine latent fingerprint detection. Optical Materials, Vol. 72, 2017, pp. 295–304.10.1016/j.optmat.2017.06.021Search in Google Scholar

[47] Devi, M. D., A. Vimala Juliet, K. Hariprasad, V. Ganesh, H. Elhosiny Ali, H. Algarni, et al. Improved UV photodetection of terbium-doped NiO thin films prepared by cost-effective nebulizer spray technique. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, Vol. 127, 2021, id. 105673.10.1016/j.mssp.2021.105673Search in Google Scholar

[48] Ashish, T., D. Bandhu, D. R. Peshwe, Y. Y. Mahajan, K. K. Saxena, and S. M. Eldin. Appearance of reinforcement, interfacial product, heterogeneous nucleant and grain refiner of MgAl2O4 in aluminium metal matrix composites. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 26, 2023, pp. 267–302.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.07.121Search in Google Scholar

[49] Senkov, O. N., D. B. Miracle, K. J. Chaput, and J. P. Couzinie. Development and exploration of refractory high entropy alloys-A review. Journal of Materials Research, Vol. 33, 2018, pp. 3092–3128.10.1557/jmr.2018.153Search in Google Scholar

[50] Couzinié, J. P., O. N. Senkov, D. B. Miracle, and G. Dirras. Comprehensive data compilation on the mechanical properties of refractory high-entropy alloys. Data in Brief, Vol. 21, 2018, pp. 1622–1641.10.1016/j.dib.2018.10.071Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Senkov, O. N., S. Gorsse, and D. B. Miracle. High temperature strength of refractory complex concentrated alloys. Acta Materialia, Vol. 175, 2019, pp. 394–405.10.1016/j.actamat.2019.06.032Search in Google Scholar

[52] Prakash, S., G. Somiya, N. Elavarasan, K. Subashini, S. Kanaga, R. Dhandapani, et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel bioactive azo compounds fused with benzothiazole and their versatile biological applications. Journal of Molecular Structure, Vol. 1224, 2021, id. 129016.10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129016Search in Google Scholar

[53] Padmaja, B., V. V. Rama Prasad, and K. V. N. Sunitha. A machine learning approach for stress detection using a wireless physical activity tracker. International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2018, pp. 33–38.10.18178/ijmlc.2018.8.1.659Search in Google Scholar

[54] Vinay, D. L., R. Keshavamurthy, S. Erannagari, A. Gajakosh, Y. D. Dwivedi, D. Bandhu, et al. Parametric analysis of processing variables for enhanced adhesion in metal-polymer composites fabricated by fused deposition modeling. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, Vol. 38, No. 3, 2024, pp. 331–354.10.1080/01694243.2023.2228496Search in Google Scholar

[55] Thirugnanasambantham, K. G., S. S. Balaji, M. V. Roshan, T. Boddu, P. S. Reddy, R. V. Prakash, et al. Geometrical parameter (˄) design approach of single phase high-entropy alloy for turbine blades. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), Vol. 2023, 2023, pp. 1–11.10.1007/s12008-023-01247-2Search in Google Scholar

[56] Thirugnanasambantham, K. G., A. Singh, P. Jegannathan, A. Barathwaj, P. Vignesh, S. Vinayak, et al. A novel alloy design for non-equiatomic high-entropy alloy (Cr–Fe–Ni–Ti–Nb): predicting entropy mix and enthalpy mix. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), Vol. 132, 2023, pp. 1–11.10.1007/s12008-023-01206-xSearch in Google Scholar

[57] Fan, J. T., L. J. Zhang, P. F. Yu, M. D. Zhang, G. Li, P. K. Liaw, et al. A novel high-entropy alloy with a dendrite-composite microstructure and remarkable compression performance. Scripta Materialia, Vol. 159, 2019, pp. 18–23.10.1016/j.scriptamat.2018.09.008Search in Google Scholar

[58] Wang, W. R., W. L. Wang, S. C. Wang, Y. C. Tsai, C. H. Lai, and J. W. Yeh. Effects of Al addition on the microstructure and mechanical property of AlxCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics, Vol. 26, 2012, pp. 44–51.10.1016/j.intermet.2012.03.005Search in Google Scholar

[59] Sam, M. and N. Radhika. Effect of heat treatment on mechanical and tribological properties of centrifugally cast functionally graded Cu/Al2O3 composite. Journal of Tribology, Vol. 140, No. 2, 2018, id. 021606.10.1115/1.4037767Search in Google Scholar

[60] Krishna, A. R., A. Arun, D. Unnikrishnan, and K. V. Shankar. An investigation on the mechanical and tribological properties of alloy A356 on the addition of WC. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 5, No. 5, 2018, pp. 12349–12355.10.1016/j.matpr.2018.02.213Search in Google Scholar

[61] Kumar, G. V., R. Pramod, P. S. Gouda, and C. S. P. Rao. Artificial neural networks for the prediction of wear properties of Al6061-TiO2 composites. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 225, No. 1, IOP Publishing, 2017, p. 012046.10.1088/1757-899X/225/1/012046Search in Google Scholar

[62] Hsu, C. Y., T. S. Sheu, J. W. Yeh, and S. K. Chen. Effect of iron content on wear behavior of AlCoCrFexMo0. 5Ni high-entropy alloys. Wear, Vol. 268, No. 5–6, 2010, pp. 653–659.10.1016/j.wear.2009.10.013Search in Google Scholar

[63] Hsu, C. Y., W. R. Wang, W. Y. Tang, S. K. Chen, and J. W. Yeh. Microstructure and mechanical properties of new AlCoxCrFeMo0. 5Ni High‐Entropy Alloys. Advanced Engineering Materials, Vol. 12, No. 1–2, 2010, pp. 44–49.10.1002/adem.200900171Search in Google Scholar

[64] Chou, Y. L., Y. C. Wang, J. W. Yeh, and H. C. Shih. Pitting corrosion of the high-entropy alloy Co1. 5CrFeNi1. 5Ti0. 5Mo0. 1 in chloride-containing sulphate solutions. Corrosion Science, Vol. 52, No. 10, 2010, pp. 3481–3491.10.1016/j.corsci.2010.06.025Search in Google Scholar

[65] Ma, S. G., S. F. Zhang, M. C. Gao, P. K. Liaw, and Y. Zhang. A successful synthesis of the CoCrFeNiAl0. 3 single-crystal, high-entropy alloy by Bridgman solidification. JOM, Vol. 65, No. 12, 2013, pp. 1751–1758.10.1007/s11837-013-0733-xSearch in Google Scholar

[66] Chen, Z., W. Chen, B. Wu, X. Cao, L. Liu, and Z. Fu. Effects of Co and Ti on microstructure and mechanical behavior of Al0.75FeNiCrCo high entropy alloy prepared by mechanical alloying and spark plasma sintering. Mater Sci Eng A, Vol. 648, 2015, pp. 217–224.10.1016/j.msea.2015.08.056Search in Google Scholar

[67] Malatji, N., A. P. I. Popoola, T. Lengopeng, and S. Pityana. Effect of Nb addition on the microstructural, mechanical and electrochemical characteristics of AlCrFeNiCu highentropy alloy. Int J Miner Metall Mater, Vol. 27, 2020, pp. 1332–1340.10.1007/s12613-020-2178-xSearch in Google Scholar

[68] Yang, X. and Y. Zhang. Prediction of high-entropy stabilized solid-solution in multi-component alloys. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 132, No. 2–3, 2012, pp. 233–238.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.11.021Search in Google Scholar

[69] Polonsky, A. T., W. C. Lenthe, M. P. Echlin, V. Livescu, G. T. Gray III, and T. M. Pollock. Solidification-driven orientation gradients in additively manufactured stainless steel. Acta Materialia, Vol. 183, 2020, pp. 249–260.10.1016/j.actamat.2019.10.047Search in Google Scholar

[70] Sahu, S. K., N. D. Badgayan, and P. R. Sreekanth. Rheological Properties of HDPE based thermoplastic polymeric nanocomposite reinforced with multidimensional carbon-based nanofillers. Biointerface Res Appl Chem, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2022, pp. 5709–5715.10.33263/BRIAC124.57095715Search in Google Scholar

[71] Sahu, S. K. and P. R. Sreekanth. Evaluation of tensile properties of spherical shaped SiC inclusions inside recycled HDPE matrix using FEM based representative volume element approach. Heliyon, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2023, pp. 1–10.10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14034Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[72] Jiao, W., H. Jiang, D. Qiao, J. He, H. Zhao, Y. Lu, et al. Effects of Mo on microstructure and mechanical properties of Fe2Ni2CrMox eutectic high entropy alloys. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 260, 2021, id. 124175.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.124175Search in Google Scholar

[73] Yeh, A. C., Y. J. Chang, C. W. Tsai, Y. C. Wang, J. W. Yeh, and C. M. Kuo. On the solidification and phase stability of a Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-Ti high-entropy alloy. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2014, pp. 184–190.10.1007/s11661-013-2097-9Search in Google Scholar

[74] Soni, V. K., S. Sanyal, and S. K. Sinha. Influence of tungsten on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of selected novel FeCoCrMnWx high entropy alloys. Intermetallics, Vol. 132, 2021, id. 107161.10.1016/j.intermet.2021.107161Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- De-chlorination of poly(vinyl) chloride using Fe2O3 and the improvement of chlorine fixing ratio in FeCl2 by SiO2 addition

- Reductive behavior of nickel and iron metallization in magnesian siliceous nickel laterite ores under the action of sulfur-bearing natural gas

- Study on properties of CaF2–CaO–Al2O3–MgO–B2O3 electroslag remelting slag for rack plate steel

- The origin of {113}<361> grains and their impact on secondary recrystallization in producing ultra-thin grain-oriented electrical steel

- Channel parameter optimization of one-strand slab induction heating tundish with double channels

- Effect of rare-earth Ce on the texture of non-oriented silicon steels

- Performance optimization of PERC solar cells based on laser ablation forming local contact on the rear

- Effect of ladle-lining materials on inclusion evolution in Al-killed steel during LF refining

- Analysis of metallurgical defects in enamel steel castings

- Effect of cooling rate and Nb synergistic strengthening on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-strength rebar

- Effect of grain size on fatigue strength of 304 stainless steel

- Analysis and control of surface cracks in a B-bearing continuous casting blooms

- Application of laser surface detection technology in blast furnace gas flow control and optimization

- Preparation of MoO3 powder by hydrothermal method

- The comparative study of Ti-bearing oxides introduced by different methods

- Application of MgO/ZrO2 coating on 309 stainless steel to increase resistance to corrosion at high temperatures and oxidation by an electrochemical method

- Effect of applying a full oxygen blast furnace on carbon emissions based on a carbon metabolism calculation model

- Characterization of low-damage cutting of alfalfa stalks by self-sharpening cutters made of gradient materials

- Thermo-mechanical effects and microstructural evolution-coupled numerical simulation on the hot forming processes of superalloy turbine disk

- Endpoint prediction of BOF steelmaking based on state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms

- Effect of calcium treatment on inclusions in 38CrMoAl high aluminum steel

- Effect of isothermal transformation temperature on the microstructure, precipitation behavior, and mechanical properties of anti-seismic rebar

- Evolution of residual stress and microstructure of 2205 duplex stainless steel welded joints during different post-weld heat treatment

- Effect of heating process on the corrosion resistance of zinc iron alloy coatings

- BOF steelmaking endpoint carbon content and temperature soft sensor model based on supervised weighted local structure preserving projection

- Innovative approaches to enhancing crack repair: Performance optimization of biopolymer-infused CXT

- Structural and electrochromic property control of WO3 films through fine-tuning of film-forming parameters

- Influence of non-linear thermal radiation on the dynamics of homogeneous and heterogeneous chemical reactions between the cone and the disk

- Thermodynamic modeling of stacking fault energy in Fe–Mn–C austenitic steels

- Research on the influence of cemented carbide micro-textured structure on tribological properties

- Performance evaluation of fly ash-lime-gypsum-quarry dust (FALGQ) bricks for sustainable construction

- First-principles study on the interfacial interactions between h-BN and Si3N4

- Analysis of carbon emission reduction capacity of hydrogen-rich oxygen blast furnace based on renewable energy hydrogen production

- Just-in-time updated DBN BOF steel-making soft sensor model based on dense connectivity of key features

- Effect of tempering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Q125 shale gas casing steel

- Review Articles

- A review of emerging trends in Laves phase research: Bibliometric analysis and visualization

- Effect of bottom stirring on bath mixing and transfer behavior during scrap melting in BOF steelmaking: A review

- High-temperature antioxidant silicate coating of low-density Nb–Ti–Al alloy: A review

- Communications

- Experimental investigation on the deterioration of the physical and mechanical properties of autoclaved aerated concrete at elevated temperatures

- Damage evaluation of the austenitic heat-resistance steel subjected to creep by using Kikuchi pattern parameters

- Topical Issue on Focus of Hot Deformation of Metaland High Entropy Alloys - Part II

- Synthesis of aluminium (Al) and alumina (Al2O3)-based graded material by gravity casting

- Experimental investigation into machining performance of magnesium alloy AZ91D under dry, minimum quantity lubrication, and nano minimum quantity lubrication environments

- Numerical simulation of temperature distribution and residual stress in TIG welding of stainless-steel single-pass flange butt joint using finite element analysis

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part I

- Electro-thermal performance evaluation of a prismatic battery pack for an electric vehicle

- Experimental analysis and optimization of machining parameters for Nitinol alloy: A Taguchi and multi-attribute decision-making approach

- Experimental and numerical analysis of temperature distributions in SA 387 pressure vessel steel during submerged arc welding

- Optimization of process parameters in plasma arc cutting of commercial-grade aluminium plate

- Multi-response optimization of friction stir welding using fuzzy-grey system

- Mechanical and micro-structural studies of pulsed and constant current TIG weldments of super duplex stainless steels and Austenitic stainless steels

- Stretch-forming characteristics of austenitic material stainless steel 304 at hot working temperatures

- Work hardening and X-ray diffraction studies on ASS 304 at high temperatures

- Study of phase equilibrium of refractory high-entropy alloys using the atomic size difference concept for turbine blade applications

- A novel intelligent tool wear monitoring system in ball end milling of Ti6Al4V alloy using artificial neural network

- A hybrid approach for the machinability analysis of Incoloy 825 using the entropy-MOORA method

- Special Issue on Recent Developments in 3D Printed Carbon Materials - Part II

- Innovations for sustainable chemical manufacturing and waste minimization through green production practices

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part I

- Characterization of Co–Ni–TiO2 coatings prepared by combined sol-enhanced and pulse current electrodeposition methods

- Hot deformation behaviors and microstructure characteristics of Cr–Mo–Ni–V steel with a banded structure

- Effects of normalizing and tempering temperature on the bainite microstructure and properties of low alloy fire-resistant steel bars

- Dynamic evolution of residual stress upon manufacturing Al-based diesel engine diaphragm

- Study on impact resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete after exposure to fire

- Bonding behaviour between steel fibre and concrete matrix after experiencing elevated temperature at various loading rates

- Diffusion law of sulfate ions in coral aggregate seawater concrete in the marine environment

- Microstructure evolution and grain refinement mechanism of 316LN steel

- Investigation of the interface and physical properties of a Kovar alloy/Cu composite wire processed by multi-pass drawing

- The investigation of peritectic solidification of high nitrogen stainless steels by in-situ observation

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of submerged arc welded medium-thickness Q690qE high-strength steel plate joints

- Experimental study on the effect of the riveting process on the bending resistance of beams composed of galvanized Q235 steel

- Density functional theory study of Mg–Ho intermetallic phases

- Investigation of electrical properties and PTCR effect in double-donor doping BaTiO3 lead-free ceramics

- Special Issue on Thermal Management and Heat Transfer

- On the thermal performance of a three-dimensional cross-ternary hybrid nanofluid over a wedge using a Bayesian regularization neural network approach

- Time dependent model to analyze the magnetic refrigeration performance of gadolinium near the room temperature

- Heat transfer characteristics in a non-Newtonian (Williamson) hybrid nanofluid with Hall and convective boundary effects

- Computational role of homogeneous–heterogeneous chemical reactions and a mixed convective ternary hybrid nanofluid in a vertical porous microchannel

- Thermal conductivity evaluation of magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluid and dusty particles with thermal radiation

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- De-chlorination of poly(vinyl) chloride using Fe2O3 and the improvement of chlorine fixing ratio in FeCl2 by SiO2 addition

- Reductive behavior of nickel and iron metallization in magnesian siliceous nickel laterite ores under the action of sulfur-bearing natural gas

- Study on properties of CaF2–CaO–Al2O3–MgO–B2O3 electroslag remelting slag for rack plate steel

- The origin of {113}<361> grains and their impact on secondary recrystallization in producing ultra-thin grain-oriented electrical steel

- Channel parameter optimization of one-strand slab induction heating tundish with double channels

- Effect of rare-earth Ce on the texture of non-oriented silicon steels

- Performance optimization of PERC solar cells based on laser ablation forming local contact on the rear

- Effect of ladle-lining materials on inclusion evolution in Al-killed steel during LF refining

- Analysis of metallurgical defects in enamel steel castings

- Effect of cooling rate and Nb synergistic strengthening on microstructure and mechanical properties of high-strength rebar

- Effect of grain size on fatigue strength of 304 stainless steel

- Analysis and control of surface cracks in a B-bearing continuous casting blooms

- Application of laser surface detection technology in blast furnace gas flow control and optimization

- Preparation of MoO3 powder by hydrothermal method

- The comparative study of Ti-bearing oxides introduced by different methods

- Application of MgO/ZrO2 coating on 309 stainless steel to increase resistance to corrosion at high temperatures and oxidation by an electrochemical method

- Effect of applying a full oxygen blast furnace on carbon emissions based on a carbon metabolism calculation model

- Characterization of low-damage cutting of alfalfa stalks by self-sharpening cutters made of gradient materials

- Thermo-mechanical effects and microstructural evolution-coupled numerical simulation on the hot forming processes of superalloy turbine disk

- Endpoint prediction of BOF steelmaking based on state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms

- Effect of calcium treatment on inclusions in 38CrMoAl high aluminum steel

- Effect of isothermal transformation temperature on the microstructure, precipitation behavior, and mechanical properties of anti-seismic rebar

- Evolution of residual stress and microstructure of 2205 duplex stainless steel welded joints during different post-weld heat treatment

- Effect of heating process on the corrosion resistance of zinc iron alloy coatings

- BOF steelmaking endpoint carbon content and temperature soft sensor model based on supervised weighted local structure preserving projection

- Innovative approaches to enhancing crack repair: Performance optimization of biopolymer-infused CXT

- Structural and electrochromic property control of WO3 films through fine-tuning of film-forming parameters

- Influence of non-linear thermal radiation on the dynamics of homogeneous and heterogeneous chemical reactions between the cone and the disk

- Thermodynamic modeling of stacking fault energy in Fe–Mn–C austenitic steels

- Research on the influence of cemented carbide micro-textured structure on tribological properties

- Performance evaluation of fly ash-lime-gypsum-quarry dust (FALGQ) bricks for sustainable construction

- First-principles study on the interfacial interactions between h-BN and Si3N4

- Analysis of carbon emission reduction capacity of hydrogen-rich oxygen blast furnace based on renewable energy hydrogen production

- Just-in-time updated DBN BOF steel-making soft sensor model based on dense connectivity of key features

- Effect of tempering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Q125 shale gas casing steel

- Review Articles

- A review of emerging trends in Laves phase research: Bibliometric analysis and visualization

- Effect of bottom stirring on bath mixing and transfer behavior during scrap melting in BOF steelmaking: A review

- High-temperature antioxidant silicate coating of low-density Nb–Ti–Al alloy: A review

- Communications

- Experimental investigation on the deterioration of the physical and mechanical properties of autoclaved aerated concrete at elevated temperatures

- Damage evaluation of the austenitic heat-resistance steel subjected to creep by using Kikuchi pattern parameters

- Topical Issue on Focus of Hot Deformation of Metaland High Entropy Alloys - Part II

- Synthesis of aluminium (Al) and alumina (Al2O3)-based graded material by gravity casting

- Experimental investigation into machining performance of magnesium alloy AZ91D under dry, minimum quantity lubrication, and nano minimum quantity lubrication environments

- Numerical simulation of temperature distribution and residual stress in TIG welding of stainless-steel single-pass flange butt joint using finite element analysis

- Special Issue on A Deep Dive into Machining and Welding Advancements - Part I

- Electro-thermal performance evaluation of a prismatic battery pack for an electric vehicle

- Experimental analysis and optimization of machining parameters for Nitinol alloy: A Taguchi and multi-attribute decision-making approach

- Experimental and numerical analysis of temperature distributions in SA 387 pressure vessel steel during submerged arc welding

- Optimization of process parameters in plasma arc cutting of commercial-grade aluminium plate

- Multi-response optimization of friction stir welding using fuzzy-grey system

- Mechanical and micro-structural studies of pulsed and constant current TIG weldments of super duplex stainless steels and Austenitic stainless steels

- Stretch-forming characteristics of austenitic material stainless steel 304 at hot working temperatures

- Work hardening and X-ray diffraction studies on ASS 304 at high temperatures

- Study of phase equilibrium of refractory high-entropy alloys using the atomic size difference concept for turbine blade applications

- A novel intelligent tool wear monitoring system in ball end milling of Ti6Al4V alloy using artificial neural network

- A hybrid approach for the machinability analysis of Incoloy 825 using the entropy-MOORA method

- Special Issue on Recent Developments in 3D Printed Carbon Materials - Part II

- Innovations for sustainable chemical manufacturing and waste minimization through green production practices

- Topical Issue on Conference on Materials, Manufacturing Processes and Devices - Part I

- Characterization of Co–Ni–TiO2 coatings prepared by combined sol-enhanced and pulse current electrodeposition methods

- Hot deformation behaviors and microstructure characteristics of Cr–Mo–Ni–V steel with a banded structure

- Effects of normalizing and tempering temperature on the bainite microstructure and properties of low alloy fire-resistant steel bars

- Dynamic evolution of residual stress upon manufacturing Al-based diesel engine diaphragm

- Study on impact resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete after exposure to fire

- Bonding behaviour between steel fibre and concrete matrix after experiencing elevated temperature at various loading rates

- Diffusion law of sulfate ions in coral aggregate seawater concrete in the marine environment

- Microstructure evolution and grain refinement mechanism of 316LN steel

- Investigation of the interface and physical properties of a Kovar alloy/Cu composite wire processed by multi-pass drawing

- The investigation of peritectic solidification of high nitrogen stainless steels by in-situ observation

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of submerged arc welded medium-thickness Q690qE high-strength steel plate joints

- Experimental study on the effect of the riveting process on the bending resistance of beams composed of galvanized Q235 steel

- Density functional theory study of Mg–Ho intermetallic phases

- Investigation of electrical properties and PTCR effect in double-donor doping BaTiO3 lead-free ceramics

- Special Issue on Thermal Management and Heat Transfer

- On the thermal performance of a three-dimensional cross-ternary hybrid nanofluid over a wedge using a Bayesian regularization neural network approach

- Time dependent model to analyze the magnetic refrigeration performance of gadolinium near the room temperature

- Heat transfer characteristics in a non-Newtonian (Williamson) hybrid nanofluid with Hall and convective boundary effects

- Computational role of homogeneous–heterogeneous chemical reactions and a mixed convective ternary hybrid nanofluid in a vertical porous microchannel

- Thermal conductivity evaluation of magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluid and dusty particles with thermal radiation