Abstract

This comprehensive review and scientometric analysis address the critical need for sustainable construction practices by examining the utilization of granite waste in concrete. The study responds to mounting environmental challenges in construction waste management, particularly addressing granite processing waste which comprises 50–60% of production [Indian Bureau of Mines. ariMinerals yearbook 2021 (Part-III: Mineral reviews), 60th edn, Granite (Advance Release), Indian Bureau of Mines, Ministry of Mines, Government of India, Nagpur, 2021.]. Through rigorous analysis of 585 publications from 2008 to 2024, the study reveals optimal granite waste replacement levels of 20–25% for sand and 10–15% for cement, yielding enhanced mechanical properties with compressive strengths up to 66 and 72 MPa, respectively. The research emphasizes the crucial role of moisture correction based on saturated surface dry conditions for consistent performance. Key findings demonstrate that granite waste can effectively replace up to 25% of sand and 15% of cement, contributing to reduced landfill use and lower CO2 emissions. The study identifies research gaps, including limited long-term durability studies and the need for standardization. Future directions propose investigating synergies with other supplementary cementitious materials and applications in emerging concrete technologies. This work provides a framework for optimizing granite waste in concrete, balancing environmental benefits with improved mechanical properties, and offering valuable insights for developing sustainable concrete solutions that potentially reduce environmental impact while enhancing performance.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background: The need for sustainable construction practices

The global construction sector’s exponential growth has created a need for sustainable practices, particularly in waste management and resource conservation. Recent studies by Rashid et al. [1] highlight how cross-sector waste recycling can create significant environmental and economic opportunities in construction. This is especially critical given that cement production, a key component of concrete, contributes approximately 8% to global CO2 emissions, making it a major contributor to climate change [2]. Comprehensive research done by Singh et al. [3] demonstrates that incorporating industrial by-products in concrete production not only addresses waste management challenges but also potentially enhances material properties.

The integration of waste materials into concrete has shown remarkable promise, with studies indicating improvements in both environmental sustainability and performance characteristics [4]. Particularly noteworthy is the research [5] on granite and marble waste as recycled aggregates, which demonstrated enhanced durability and mechanical properties in concrete applications. This finding is further supported by Thakur et al.’s [6] investigations into fine aggregates from industrial waste, which validated their structural viability while promoting sustainable construction practices.

The focus on granite waste utilization is especially pertinent in the Indian context, where the country’s position as one of the world’s leading granite producers generates substantial waste volumes. With granite processing generating 20–30% waste during cutting and polishing operations, the environmental implications are significant. This waste not only poses disposal challenges but also presents an opportunity for sustainable resource utilization in construction. Understanding and harnessing this potential could simultaneously address waste management issues and meet the growing demand for sustainable construction materials. Recent advances in sustainable construction materials have employed sophisticated analytical techniques to understand material behavior at multiple scales. Wang and Du [7] investigated microscopic interface deterioration mechanisms in high-toughness recycled aggregate concrete using 4D in situ computed tomography experiments, revealing critical insights into material degradation patterns. Complementary research utilizing mesoscopic 3D simulation techniques [8] has enhanced our understanding of mechanical behavior in sustainable concrete materials. Studies exploring the role of recycled aggregates in engineered geopolymer composites [9] have demonstrated the importance of particle size effects and content optimization. Advanced investigations into cyclic loading effects [10] and mesoscopic mechanical behavior [11] have further established the complex relationships between material composition and structural performance. These sophisticated analytical approaches have yet to be fully applied to granite waste concrete, presenting an opportunity for advancing our understanding of this sustainable material.

As we transition to examining the current state of research on granite waste in concrete, it becomes evident that this focus aligns with broader sustainability goals while addressing specific regional challenges in waste management and construction material needs. The following sections will delve deeper into how granite waste can be effectively utilized to create more sustainable concrete solutions while maintaining or enhancing performance characteristics.

1.2 Granite waste: A growing environmental concern

In the context of industrial waste utilization, granite waste presents a particularly compelling case for sustainable concrete development. India’s position as a leading granite producer, with reserves exceeding 46,320 million cubic meters and annual production reaching 6.56 million cubic meters in 2020–21, generates substantial waste volumes – approximately 50–60% of total production [5]. This significant waste generation creates both environmental challenges and opportunities for sustainable resource utilization.

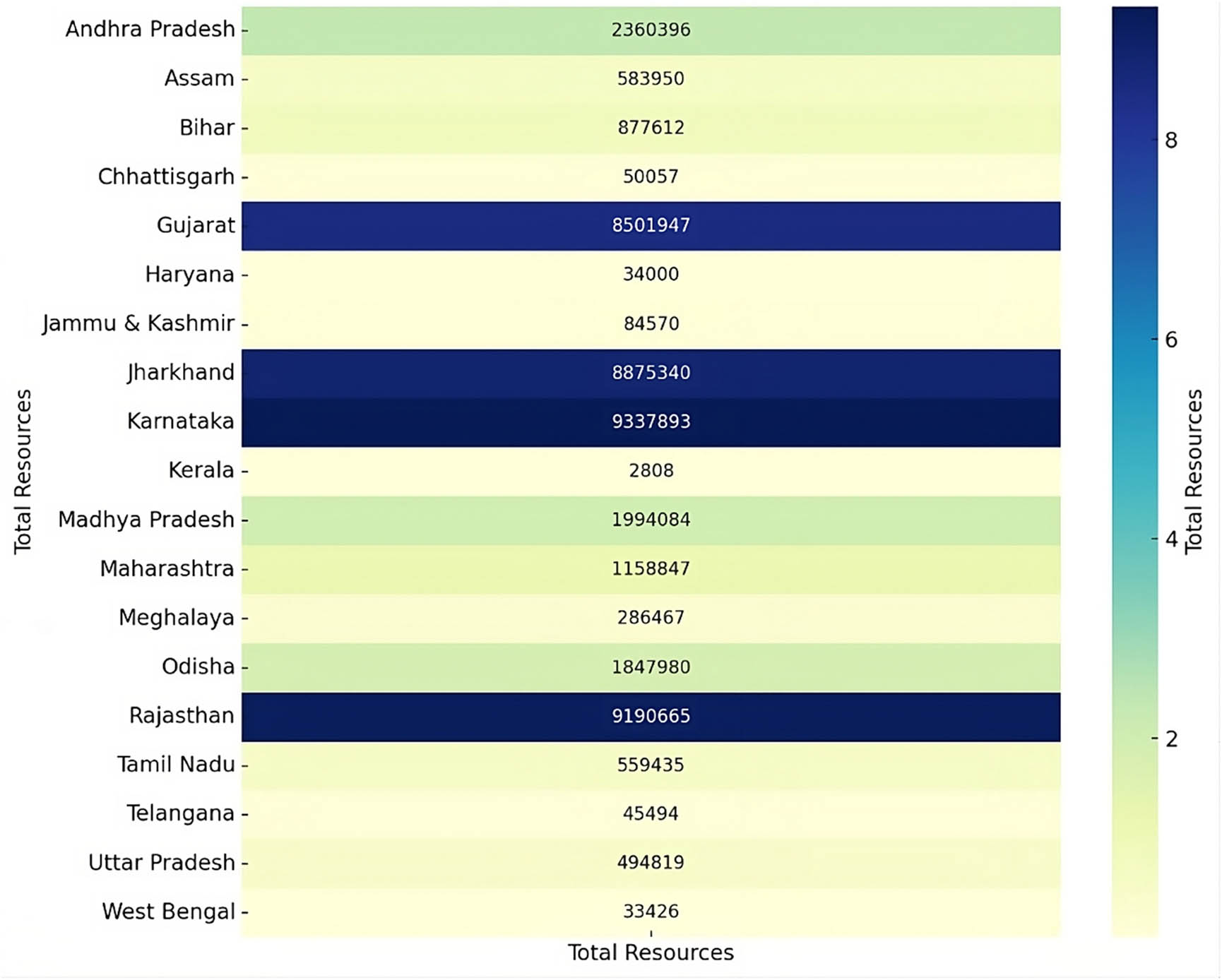

As illustrated in Figure 1, India’s granite resources demonstrate significant regional concentration, with states like Gujarat, Karnataka, Jharkhand, and Rajasthan containing the highest deposits. This distribution pattern directly influences waste generation patterns and potential utilization opportunities. The processing of granite generates various forms of waste, including powder, sludge, and slurry, each presenting unique environmental challenges and potential applications in the construction materials.

Heatmap of granite resources in Indian states.

The environmental implications of improper granite waste disposal extend beyond immediate visual impact. Fine particle emissions contribute to air pollution, while water contamination and soil degradation pose serious risks to both ecosystems and human health [12]. These environmental concerns, coupled with increasing landfill costs and regulatory pressures, necessitate innovative solutions for granite waste utilization.

1.3 Current state of research on granite waste in concrete

Recent research has demonstrated promising results in incorporating granite waste into concrete mixtures. Studies have shown improvements in mechanical properties, durability, and workability when granite waste partially replaces conventional concrete components [3]. For instance, research by Abukersh and Fairfield [13] achieved enhanced mechanical properties and surface finish in concrete mixtures containing up to 30% red granite dust (GD) as cement replacement.

Complementary research in sustainable concrete development has revealed synergistic possibilities when combining different waste materials. Saxena et al. [14] investigated microfiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete incorporating various waste mineral admixtures, demonstrating improved mechanical properties and reduced permeability. Similarly, Alharbi et al. [15] explored smart cement paste modified with waste steel slag, showcasing potential enhancements in both structural and functional properties.

However, despite these encouraging findings, widespread adoption of granite waste in concrete production remains limited. This hesitation stems from several factors, including inconsistent research findings, inadequate understanding of long-term behavior, and the absence of comprehensive performance assessments across various parameters. Most existing studies focus on specific aspects of granite waste concrete without providing a holistic view of its performance characteristics.

1.4 Research gaps and innovation of the present study

1.4.1 Critical analysis of existing literature reveals several significant research gaps

The absence of comprehensive studies examining granite waste as both sand and cement replacement in concrete, particularly regarding combined effects on mechanical properties and durability, represents a significant knowledge gap. Current understanding of optimal replacement levels for different applications remains limited, especially considering the variability in granite waste properties across sources. Recent advances in material characterization techniques [7–11] highlight additional gaps in understanding interface mechanisms, mesoscopic behavior, and dynamic performance under varying conditions. Systematic studies on moisture correction techniques, crucial for achieving consistent and predictable performance in granite waste concrete, are notably scarce. The current literature lacks thorough synthesis providing clear direction for future research and practical applications. Additionally, limited exploration of sustainability aspects, including carbon footprint reduction potential, indicates an area requiring further investigation. This study addresses these gaps through a comprehensive scientometric analysis and critical review of existing literature on granite waste utilization in concrete. The innovation lies in our systematic approach to synthesizing and analyzing scattered information through

Comprehensive scientometric analysis of 585 publications spanning 2008–2024.

Systematic synthesis of performance data across different applications.

Statistical validation of optimal replacement thresholds.

Development of practical implementation guidelines incorporating moisture correction protocols.

This innovative approach provides a robust framework for understanding granite waste concrete behavior while establishing clear pathways for practical implementation. The study addresses these gaps through a comprehensive scientometric analysis and critical review of existing literature on granite waste utilization in concrete. The innovation lies in the systematic approach to synthesizing and analyzing scattered information, providing a holistic view of current research status, and identifying future directions for sustainable concrete development.

1.5 Significance and objectives of the study

The significance of this research extends beyond academic contribution, offering practical implications for sustainable construction practices. The significance of this research extends beyond academic contribution, offering practical implications for sustainable construction practices. This comprehensive review addresses critical industry challenges as follows: First, it provides essential guidance for the granite industry, where waste generation (50–60% of total production [16]) poses significant environmental and economic challenges. The findings offer scientifically validated approaches for transforming this waste into valuable construction material, potentially saving millions in disposal costs while reducing environmental impact. Second, for the construction industry, this study establishes clear optimization thresholds for granite waste utilization (20–25% for sand and 10–15% for cement replacement), supported by extensive statistical analysis of mechanical properties. This practical guidance enables immediate implementation while ensuring reliable performance. Third, from an environmental perspective, the study demonstrates how optimal granite waste incorporation can reduce CO2 emissions associated with cement production, which currently contributes approximately 8% to global CO2 emissions [2]. The findings support industry efforts to meet increasingly stringent environmental regulations. Fourth, the research provides crucial insights for regulatory bodies and policymakers by establishing evidence-based frameworks for sustainable construction practices. The comprehensive analysis of moisture correction protocols and quality control measures supports the development of standardized guidelines for granite waste utilization. These contributions are particularly timely given increasing global emphasis on sustainable construction practices and circular economy principles in the built environment.

By conducting a comprehensive review and analysis of granite waste utilization in concrete, this study aims to:

Provide a critical assessment of current knowledge regarding granite waste concrete, encompassing fresh properties, mechanical strength, and durability characteristics.

Analyze and synthesize data on optimal replacement levels for both fine aggregate and cement applications across various studies.

Evaluate the effectiveness of moisture correction techniques and their impact on concrete properties.

Identify key research trends, knowledge gaps, and future research directions.

Develop recommendations for effective granite waste utilization in concrete production, considering both technical and sustainability aspects.

Assess granite waste concrete’s potential contribution to sustainable construction practices and environmental impact reduction.

These objectives align with broader goals of promoting circular economy principles in construction while reducing the sector’s environmental footprint.

1.6 Methodology and approach

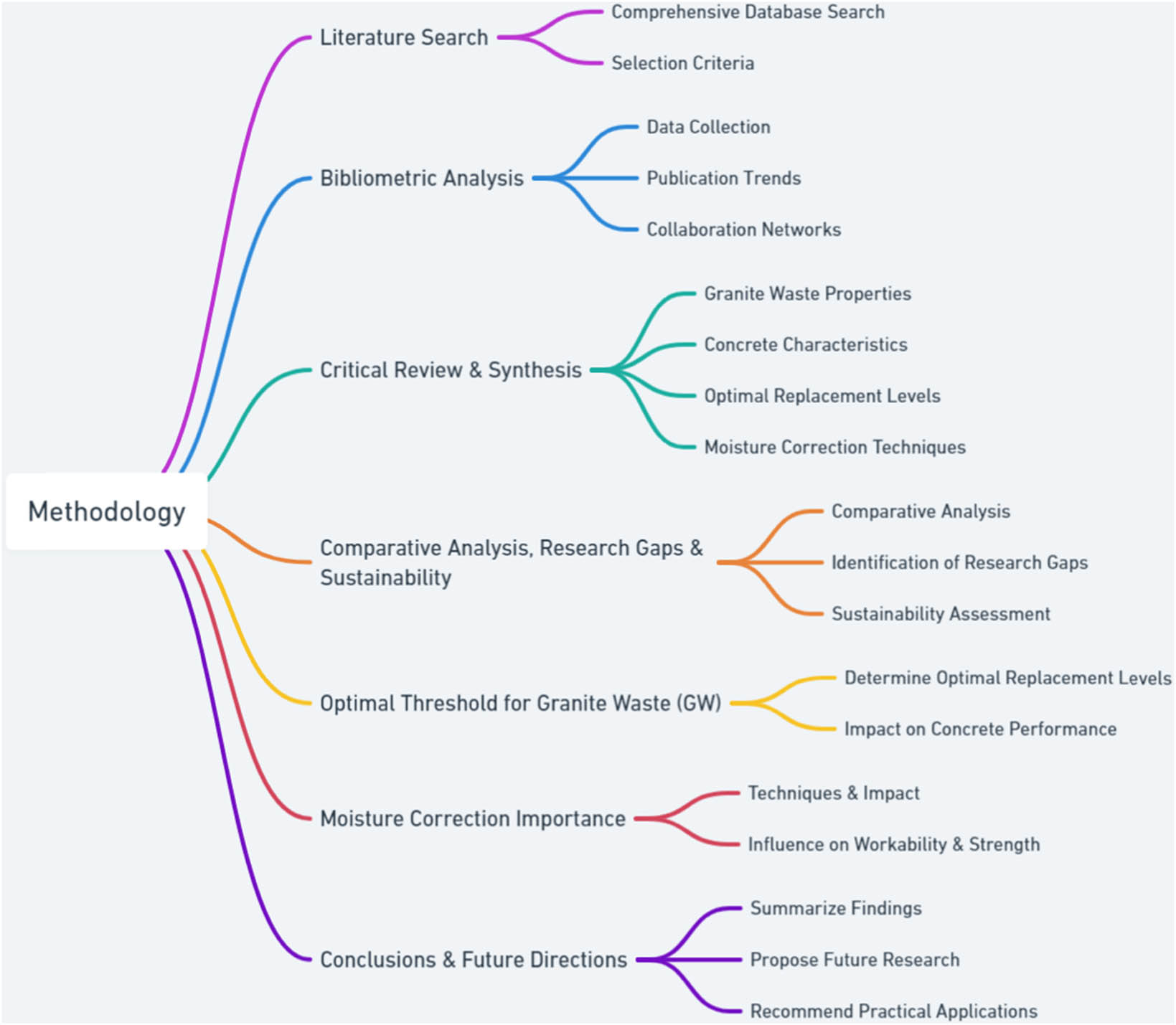

To achieve these objectives, this study employs a rigorous methodology combining scientometric analysis and critical literature review, as illustrated in Figure 2. This systematic approach ensures comprehensive coverage of existing research while identifying critical patterns and relationships in granite waste concrete development. The methodology enables detailed examination of material properties, performance characteristics, and sustainability implications, providing a robust foundation for future research and practical applications in sustainable construction materials.

Study analysis workflow.

The structured approach facilitates systematic analysis of research trends, optimization strategies, and performance parameters, supporting evidence-based recommendations for granite waste utilization in concrete.

2 Scientometric analysis and applications of granite waste in concrete

2.1 Research trends and application framework

The systematic scientometric analysis conducted on 585 publications from Web of Science (2008–2024) provides crucial insights for both academic research advancement and industrial implementation. During this period, research focus evolved from basic utilization studies to comprehensive performance analysis, with a significant increase from 44 publications in 2008 to 552 publications in 2024, indicating growing interest in sustainable construction practices. Building upon the research gaps identified in Section 1.4, particularly regarding combined replacement effects and moisture correction techniques, the methodology employed a comprehensive search query combining terms related to granite waste and concrete applications, enabling identification of key trends and practical applications [17].

This analytical approach was specifically chosen to address critical research gaps through systematic evidence synthesis. The methodology enables (a) comprehensive assessment of cement and sand replacement effects through multi-parameter analysis, (b) identification of optimal replacement levels across different applications through cross-study comparison, (c) evaluation of moisture correction techniques through systematic review, (d) integration of sustainability metrics through environmental impact analysis, and (e) development of standardization frameworks through best practice synthesis. These methodological components directly align with the research objectives outlined in Section 1.4, providing a comprehensive, data-driven understanding of global research trends and their practical implications in granite waste utilization.

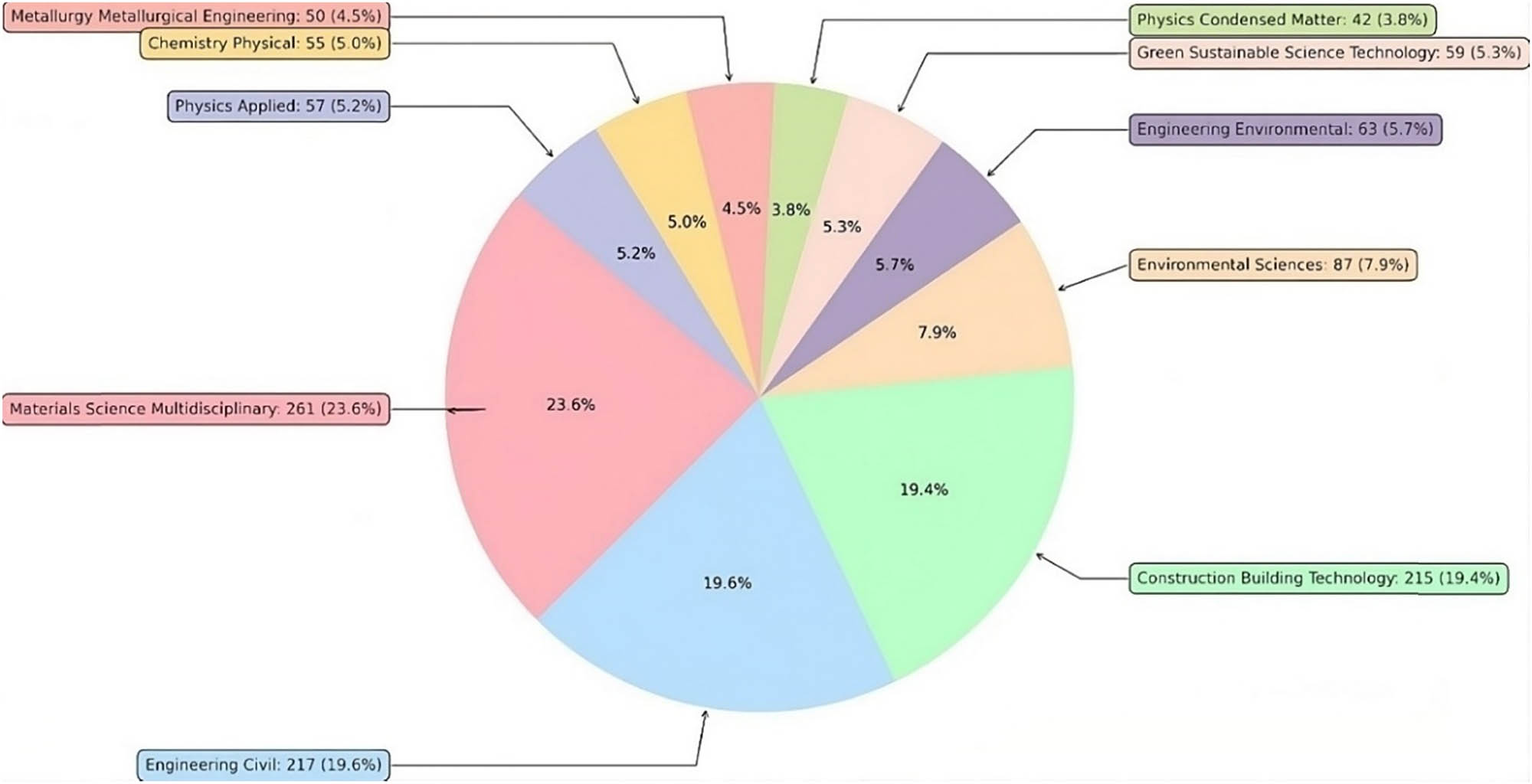

Subject area analysis, depicted in Figure 3, demonstrates a strong integration of research and practical applications. Engineering Civil and Construction Building Technology jointly contribute 39% of publications (19.6 and 19.4%, respectively), while Materials Science Multidisciplinary leads with 23.6% of research output [12]. This distribution has shifted over the study period, with an increasing focus on environmental aspects in recent years, significantly benefiting industry practitioners by establishing validated implementation strategies and optimal replacement levels, while offering academics clear pathways for identifying research gaps and emerging trends [14].

Web of Science search results by subject area.

Environmental Sciences research (7.9% of publications) reveals substantial benefits beyond waste management. Analysis of publication patterns reveals limited comprehensive studies combining sand and cement replacement effects (represented by only 12% of publications), insufficient standardization of moisture correction techniques (addressed in 8% of studies), and sparse long-term durability investigations (15% of publications). These identified gaps align directly with the research objectives outlined in Section 1.4, forming the basis for this systematic review. Studies demonstrate that incorporating granite waste can effectively reduce concrete’s carbon footprint through partial replacement of energy-intensive components [18], directly impacting both industry sustainability practices and academic research directions in eco-friendly construction materials [19].

2.2 Knowledge network analysis and research clusters

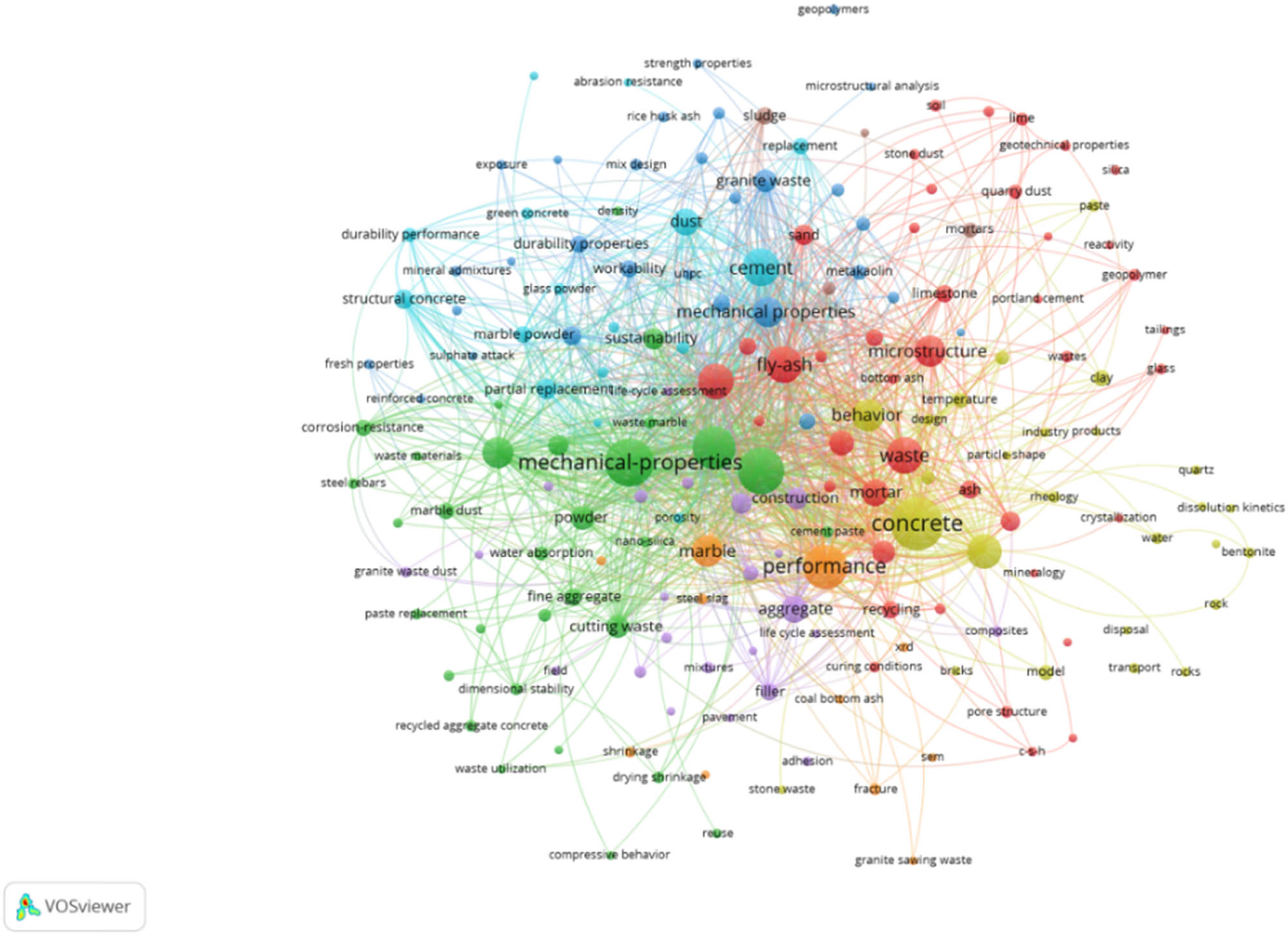

Building upon the subject area analysis, keyword co-occurrence analysis, visualized in Figure 4, identifies five interconnected research themes: mechanical properties and durability (red cluster), sustainable development practices (green cluster), aggregate replacement studies (blue cluster), microstructural investigations (yellow cluster), and specialized concretes with recycled materials (purple cluster). This network mapping not only illustrates research evolution over time but also provides academics with emerging research directions while helping industry practitioners identify proven applications [20].

Keyword network analysis in concrete research: Visualizing core topics and relationships.

The analysis reveals strong connections between fundamental material science and practical engineering applications, demonstrating how theoretical research translates into implementable solutions. Industry benefits include benchmarking performance standards and identifying optimal replacement ratios, while academics gain insights into knowledge gaps and potential research directions [21]. The clustering pattern demonstrates the multifaceted nature of granite waste research, encompassing both theoretical foundations and practical implementations, which directly informs the property analysis presented in Section 3.

2.3 Global research distribution and knowledge transfer

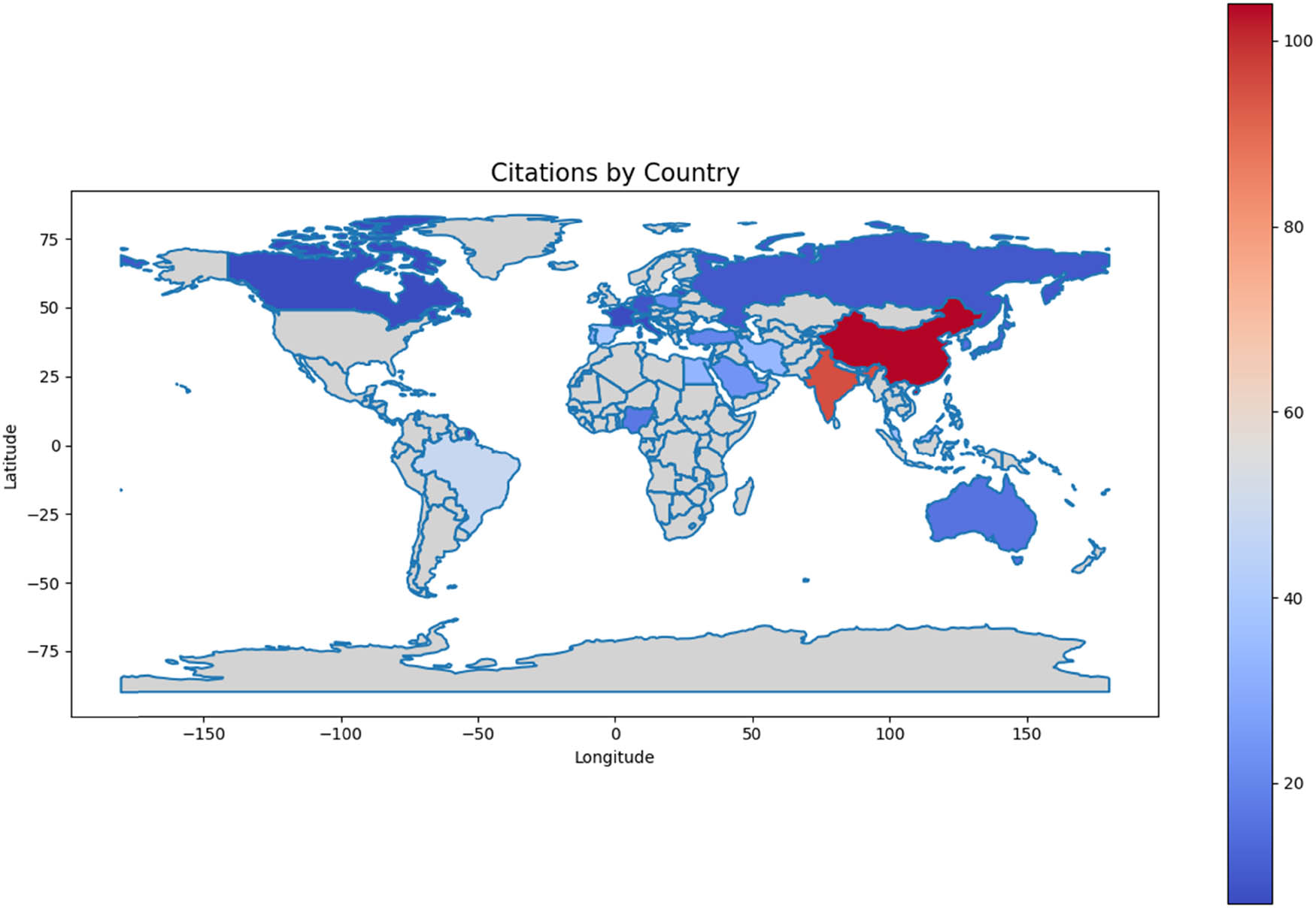

The geographical distribution analysis, illustrated in Figure 5, reveals China, India, and European countries as leaders in granite waste utilization research, with these regions collectively contributing over 65% of total publications. This concentration reflects multiple factors including granite waste availability, construction industry scale, and national sustainability priorities [22]. The distribution pattern presents significant opportunities for knowledge transfer and collaborative research between high-output regions and areas showing lower engagement, particularly in Africa and Southeast Asia, where granite waste management remains a growing concern [20].

Global distribution of concrete research publications: Comparative analysis by country.

For industry stakeholders, this distribution provides valuable insights into regional implementation strategies and best practices that can be adapted across different geographical contexts. Academic researchers benefit from identifying potential international collaboration opportunities and understanding regional research focuses [23]. While the keyword analysis reveals thematic research clusters, understanding their geographical distribution provides crucial context for knowledge transfer and implementation. The concentration of research in certain regions presents opportunities for global knowledge dissemination and adaptation of successful practices, particularly relevant for the material properties and applications discussed in Section 3.

The scientometric analysis establishes a comprehensive understanding of granite waste utilization in concrete, bridging the gap between research and practical implementation. This understanding forms the foundation for detailed examination of granite waste properties and characteristics, which is crucial for its effective utilization in concrete applications. The transition from global research patterns to specific material properties enables detailed understanding of how granite waste characteristics influence concrete performance, as examined in Section 3. This connection between research trends and material properties provides a robust framework for addressing the identified research gaps and advancing sustainable construction practices.

3 Granite waste

3.1 Sources and types of granite waste

The granite processing industry generates substantial volumes of waste materials through various production stages, creating both environmental challenges and opportunities for sustainable construction. During cutting and polishing operations, approximately 20–30% of the granite block transforms into waste material [16]. This significant waste generation occurs primarily in three stages: quarrying, processing, and polishing [24]. The waste manifests in two primary forms, each with distinct characteristics affecting their potential applications in concrete. The first form comprises granite powder (GP) or GD, generated during cutting and sizing operations, with particle sizes comparable to natural sand [16]. The second form emerges as granite slurry, produced when GD combines with cooling and lubrication water used in cutting operations. As observed by Alyamaç and Ince [25], this slurry, initially a colloidal waste, settles near processing units. Upon water evaporation, it forms substantial deposits of non-biodegradable fine GP waste, presenting both disposal challenges and potential resource opportunities.

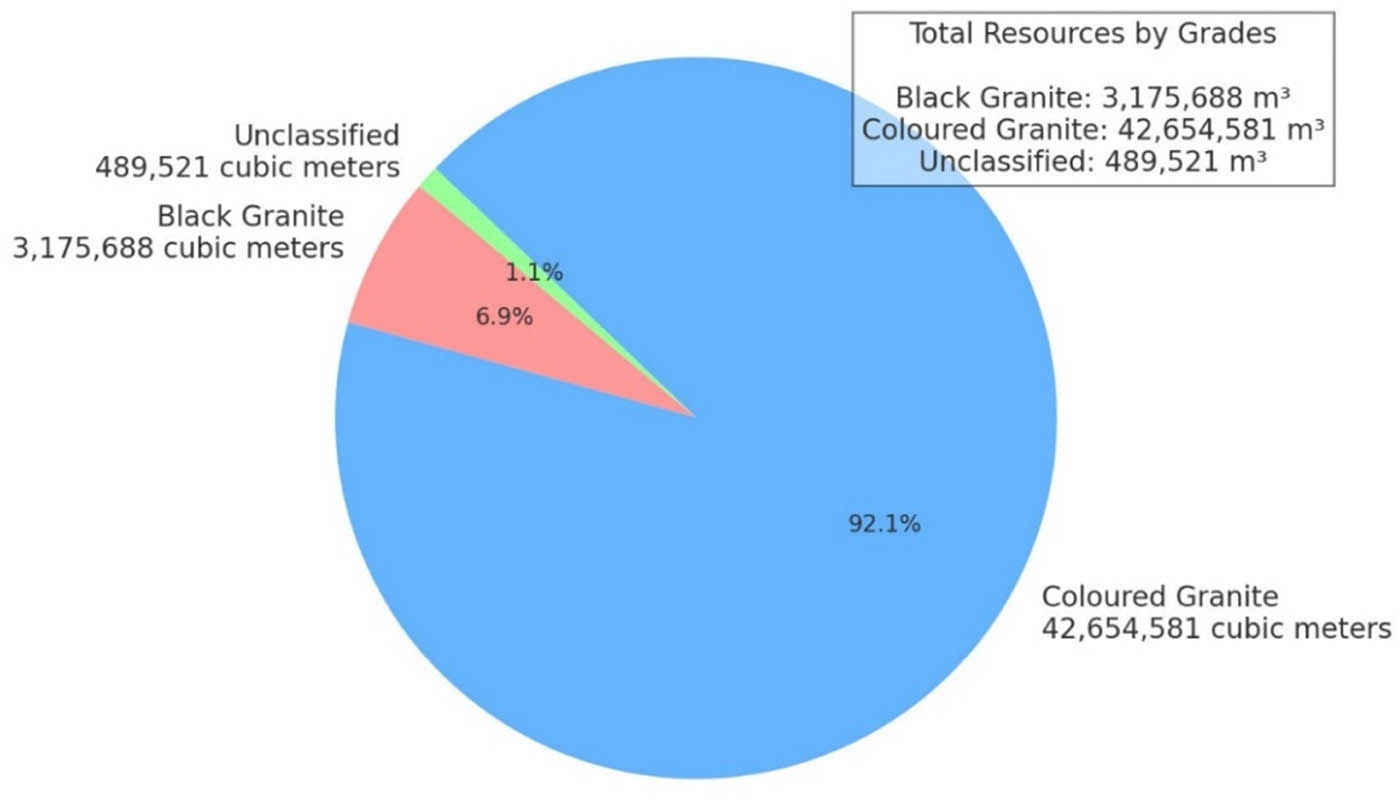

India’s granite resources showcase remarkable diversity, featuring over 200 distinct granite shades. Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of these resources by grade, revealing that Colored Granite dominates the composition at 92.1% (42,654,581 m3), followed by Black Granite at 6.9% (3,175,688 m3), with unclassified granite comprising the remaining 1.1% (489,521 m3) [5]. This abundance and variety of granite resources directly influence the volume and characteristics of generated waste. The geographical distribution of India’s granite resources, totaling 46,320 million cubic meters, shows significant concentration in three states: Karnataka, Rajasthan, and Jharkhand, collectively accounting for 59% of national resources, each contributing approximately 20, 20, and 19%, respectively [5]. This concentration of resources correlates with areas facing substantial waste management challenges, particularly regarding dust pollution and environmental impact. The industry’s approach to waste management has evolved toward sustainable solutions, with increasing focus on utilizing granite waste as a replacement material in concrete production. This strategy serves dual purposes: addressing waste disposal challenges while conserving natural resources such as fluvial sand [16].

Total resources of granite by grades (in cubic meters).

The viability of incorporating granite waste in concrete applications depends critically on its physical and chemical characteristics, which significantly influence concrete’s fresh state properties, mechanical performance, and durability. Understanding these characteristics, which will be examined in detail in subsequent sections, provides the foundation for optimizing granite waste utilization in sustainable concrete development. This systematic characterization of granite waste sources and types establishes the context for exploring its potential as a valuable resource in construction applications, rather than merely a waste product requiring disposal.

3.2 Granite waste properties

3.2.1 Properties and application framework

Building upon the research trends identified in Section 2, this section examines the fundamental characteristics of granite waste that influence its performance in concrete applications. This analysis bridges theoretical understanding with practical implementation strategies, addressing the critical need for standardization and quality control in sustainable construction practices. The systematic evaluation of physical and chemical properties provides essential insights for optimizing granite waste utilization in concrete mixtures.

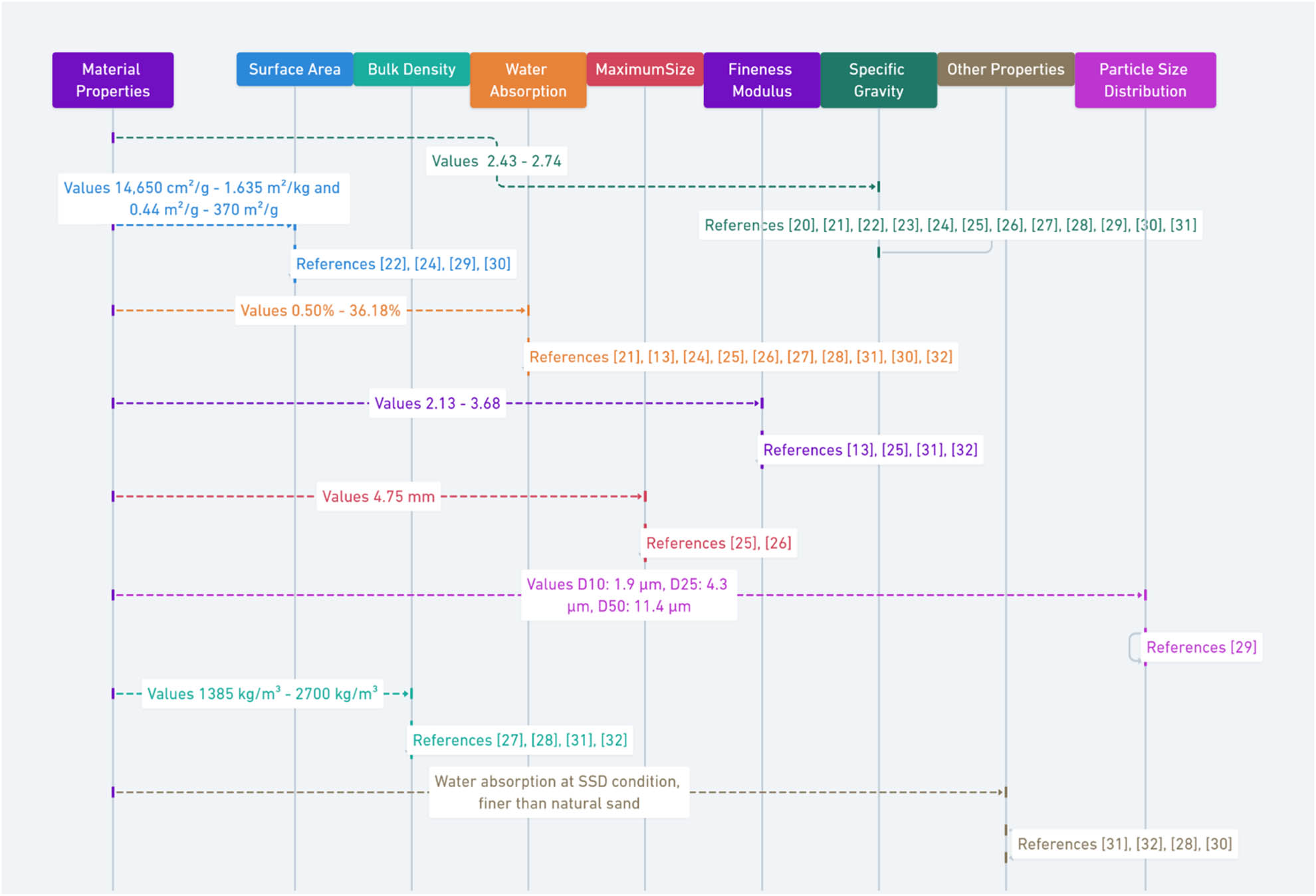

3.2.2 Physical properties

The systematic characterization of granite waste’s physical attributes reveals critical parameters for concrete mix design optimization. As illustrated in Figure 7, comprehensive testing between 2020 and 2024 has established key property ranges essential for quality control and performance prediction. The material exhibits specific gravity values between 2.43 and 2.74, indicating consistency suitable for concrete applications. Surface area measurements demonstrate two distinct ranges: 1,465–1,635 m²·kg−1 in primary studies, and 440–370 m²·kg−1 in complementary research, reflecting the material’s variable fineness and its potential impact on water demand. Water absorption capacity varies significantly from 0.50 to 30.18%, necessitating careful moisture correction in mix designs. The fineness modulus range of 2.13–3.68, combined with a maximum particle size of 4.75 mm, aligns well with conventional concrete aggregate requirements. Bulk density measurements spanning 1,385–2,700 kg·m−³ provide essential data for mix proportioning calculations.

Flowchart depicting the physical properties of granite waste.

3.2.3 Chemical properties

Table 1 presents novel insights into granite waste’s chemical composition variability from 2013 to 2024. Silicon dioxide (SiO2) dominates the composition, typically ranging from 60 to 75%, closely matching the composition levels found in fine aggregates, which suggests its potential as a partial sand replacement in concrete mixtures. This compositional similarity, coupled with the material’s physical characteristics, provides a strong foundation for sand substitution. Additionally, the presence of reactive silica and alumina compounds indicates potential pozzolanic activity, supporting its use as a partial cement replacement to reduce CO₂ emissions. The aluminum oxide (Al2O3) content generally falls between 10 and 17%, as documented by Abouelnour et al. [26] and Nega et al. [28], while iron oxide (Fe2O3) levels show remarkable variation, from 0.83% [3] to 13.35% [14]. Loss on ignition values range from 0.29 to 30.81%, indicating varying organic content levels that influence concrete properties.

Chemical composition of granite waste from various sources (2013–2024)

| Ref. | Material | Chemical composition (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | Na2O | K2O | SO3 | TiO2 | P2O5 | MnO | LOI | |||

| [26] | GP | 68.6 | 13.7 | 3.22 | 2.64 | 0.6 | 2.93 | 6.01 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.2 | 1.18 | ||

| [27] | GP | 52.48 | 10.62 | 3.03 | 26.17 | 0.37 | 5.54 | 1.12 | 0.31 | |||||

| [28] | Granite waste powder (GWP) | 70.1 | 14.02 | 1.84 | 3.96 | 0.66 | 3.32 | 1.72 | ||||||

| [29] | GWP | 72.04 | 14.42 | 1.68 | 1.82 | 0.71 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 0.29 | |||||

| [30] | GP | 72.11 | 14.15 | 1.88 | 1.47 | 0.4 | 3.47 | 5.03 | 0.26 | 1.23 | ||||

| [14] | Fine granite waste powder (FGWP) | 20.45 | 1.47 | 6.02 | 24.89 | 13.92 | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 30.81 | ||

| [31] | GWP | 69.77 | 10.74 | 1.8 | 0.89 | 0.54 | 3.13 | 4.84 | 0.05 | 0.03 | ||||

| [32] | GWP | 69.77 | 10.74 | 1.8 | 0.89 | 0.54 | 3.13 | 4.84 | 0.05 | 0.03 | ||||

| [33] | GWP | 91.18 | 0.22 | 1.9 | 0.53 | 1.82 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 2.72 | |

| [34] | GWP | 70.57 | 12.47 | 6.09 | 1.48 | 0.27 | 4.21 | 4.12 | 0.12 | 1.4 | ||||

| [22] | Granite sludge (GS) | 59.59 | 13.86 | 10.45 | 5.82 | 2.36 | 3.86 | 1.92 | 2.14 | |||||

| [35] | Granite waste | 63.35 | 11.88 | 3.73 | 9.68 | 1 | 2.98 | 3.98 | 0.1 | 0.23 | 0.1 | 2.02 | ||

| [20] | GWD | 70.2 | 15.8 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 0.6 | 1.6 | ||||

| [36] | GS | 72.67 | 16.78 | 2.49 | 1.4 | 3.17 | 2.32 | 0.05 | 0.97 | |||||

| [27] | GWP | 72.9 | 14.65 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 0.37 | 3.85 | 3.98 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.41 | ||

| [21] | GS | 58.17 | 11.96 | 13.35 | 3.27 | 0.36 | 4.69 | 3.84 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 2.58 | ||

| [37] | GP | 74.39 | 13.5 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 4.16 | 4.79 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| [3] | GP | 72.57 | 15.63 | 0.83 | 4.21 | 6.76 | ||||||||

| [38] | GP | 53.2 | 14.1 | 12.3 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 1.2 | |||||||

| [18] | GP | 69.6 | 14.99 | 2.52 | 2.36 | 1.6 | 3.59 | 4.04 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.52 | ||

| [39] | GP | 62.1 | 12.4 | 9.8 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 2.71 | ||||

| [40] | Granite saw dust | 82.04 | 14.42 | 1.22 | 1.82 | 0.81 | 4.12 | |||||||

| [23] | GP | 63.22 | 15.66 | 4.47 | 3.26 | 1.82 | 2.68 | 5.02 | 2.04 | |||||

3.2.4 Influence of granite waste on concrete: Comparative analysis of mechanical properties and sustainable applications

Researchers have explored GP’s potential as both sand and cement replacement in concrete mixtures. To systematically analyze these applications, we compiled comprehensive data in Tables 2 and 3, supplemented by trend analysis, moving averages, and quadratic fit calculations to determine optimal replacement thresholds in Section 4. Table 2 presents a systematic analysis of granite waste utilization as fine aggregate replacement, and Table 3 examines granite waste as a cement replacement material. This dual potential for replacement offers flexibility in sustainable concrete design while addressing both resource conservation and emission reduction.

Utilization of GW as partial replacement (PR) of fine aggregate (FA) in concrete: A comparative analysis of recent studies

| Ref. | Material used | Material replaced | Mix Id description | Granite waste replacement (%) | Suggested optimum replacement (%) | Influence on mechanical property | Limitation | Sustainability aspect | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | FGWP | Natural fine sand (Nfs) | Geopolymer concrete with varying FGWP contents | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 | 15 | Improved compressive strength, flexural strength, and static modulus of elasticity up to 15% replacement | Reduced workability with increased FGWP content | Utilizes industrial waste, reduces landfill disposal | Optimize alkaline activator content for different FGWP percentages |

| [31] | GWP | Fine aggregate | Fly ash blended self-compacting concrete with varying granite waste content | 0, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 50, 60 | 40 | Improved compressive and tensile strengths up to 40% replacement | Reduced workability at higher replacement levels | Utilizes waste material, reduces natural sand consumption | Optimize mix design for higher replacement levels |

| [32] | GWP | Nfs | Geopolymer concrete with varying granite waste content and moisture conditions | 0, 25, 50 | 50 | Improved early-age strength, decreased flexural strength at saturated surface dry (SSD) condition | Reduced workability at higher replacement levels | Utilizes waste material, reduces natural sand consumption | Optimize mix design for higher replacement levels |

| [41] | GWP | Natural river sand | Low-strength (L) and high-strength (H) concrete with varying granite waste content | 0, 20, 30, 50 | Not specified | Decreased tensile and flexural strengths, no significant effect on compressive strength | Reduced workability, weaker interfacial transition zone | Utilizes waste material, reduces natural sand consumption | Optimize mix design, use superplasticizer for workability |

| [33] | GWP | Silica sand | Reactive powder concrete with varying w/b, silica fume-to-binder ratio (sf/b), binder content, and granite waste | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 | 30 | Improved compressive and flexural strengths up to 30% replacement | Increased superplasticizer demand | Utilizes waste material, reduces natural resource consumption | Optimize mix design for higher replacement levels |

| [42] | GP | Fine aggregate | Concrete with varying GP content | 0, 20, 30, 40 | Not specified | Follows conventional strength trend when properly moisture corrected | Requires careful moisture correction | Utilizes waste material, reduces aggregate consumption | Proper moisture correction method |

| [43] | GP | Sand | GrP10, GrP20, GrP30, GrP40, GrP50 | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 | 30 | Increase up to 30%, decrease beyond | Max 30% | Reduces landfill waste | Particle size optimization |

| [35] | Granite waste + fly ash | Sand | GW/FA blend | 10 | 10 | Increase in compressive strength, reduced chloride ion penetration | Max 10% tested | Reduces landfill waste, uses industrial byproducts | Optimize particle size distribution |

| [36] | GS | Sand | Series I, II, III | 0, 30, 60 | 60 | Increase | Up to 60% tested | Utilizes waste, reduces sand use | Optimize particle size |

| [37] | Waste GP | Fine aggregate (Sand) | 4CS30, 4CS40, 6CS30, 6CS40 | 30, 40 | 30–40 | Increased compressive strength, tensile bond strength, and adhesive strength | Increased drying shrinkage | Utilization of waste GP, reduction in natural sand usage | Further studies on durability aspects |

| [3] | Granite industry by-product (GIB) | Fine aggregate (sand) | GIB0, GIB10, GIB25, GIB40, GIB55, GIB70 | 0, 10, 25, 40, 55, 70 | 25 | Improved compressive strength, flexural strength, and durability up to 25% replacement | Decreased workability at higher replacement levels | Utilization of waste GP, reduction in natural sand usage | Further studies on optimizing workability at higher replacement levels |

| [38] | GP | Fine aggregate | EGG0, EGG1, EGG2, EGG3 | 0, 5, 10, 15 | 10 | Improved erosion resistance up to 10% replacement | Decreased workability at higher replacement | Utilization of granite waste | Optimize workability at higher replacement levels |

| [44] | Granite cutting waste (GCW) | River sand | D0-D70, E0-E70, F0-F70 | 0, 10, 25, 40, 55, 70 | 25–40 | Improved strength up to 25–40% replacement | Reduced workability at higher replacement | Utilization of waste, reduced sand mining | Improve workability at higher replacement levels |

| [16] | GCW | Fine aggregate (sand) | G0, G10, G20, G30, G50 | 0, 10, 20, 30, 50 | 30 | Improved strength up to 30% replacement | Reduced workability at higher replacement | Utilization of waste, reduced sand mining | Improve workability at higher replacement levels |

| [12] | GCW | Natural sand | G0, G10, G20, G30, G50 | 0–50% | 30 | Improved up to 30% | Decreased workability | Utilizes waste material | Use of superplasticizers |

| [45] | GCW | River sand | 0–40% replacement | 0–40 | 25 | Improved up to 25% | Decreased workability | Utilizes waste material reducing environmental impact | Use of superplasticizers to improve workability |

| [46] | GCW | River Sand | A0-F70 (0.30–0.55 water-cement [w/c] ratio) | 0–70 | 25–40 | Improved up to 40% | Decreased workability | Utilizes waste material reducing environmental impact | Use of superplasticizers to improve workability |

| [47] | GP | Fine aggregate | M20 mix with 0–100% replacement | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 100 | 40 | Improved strength up to 40% replacement | Decreased workability | Utilizes waste material | Use of superplasticizers |

| [48] | GP | Sand | MG0, MG5, MG10, MG15, MG20 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 | 10 | Improved strength up to 10% replacement | Decreased workability | Utilizes waste material | Use of superplasticizers |

| [49] | GCW | River sand | G0, G10, G25, G40, G55, G70 | 0, 10, 25, 40, 55, 70 | 40 | Improved strength up to 40% replacement | Decreased workability | Utilizes waste material | Use of superplasticizers |

| [50] | GP | Fine aggregate | GP0, GP5, GP10, GP15, GP20, GP25 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 | 15–20 | Improved compressive strength up to 15–20% replacement | Decreased workability | Utilizes waste material | Use of superplasticizers |

| [51] | Granite fines | Sand | M20 grade concrete with w/c ratio of 0.55 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 | 15 | Improved compressive, split tensile, and flexural strength | Increased water absorption | Utilization of waste granite fines | — |

| [52] | GP | Sand | M30 grade concrete with admixtures | 0, 25, 50 | 25 | Improved compressive and split tensile strength | Not specified | Utilization of waste GP | — |

| [53] | GP | Fine aggregate | M30 grade concrete | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 | 15 | Improved early-age strength up to 15% replacement | Workability decreases with increasing GP | Utilization of waste GP | Chemical bleaching to remove oil traces |

| [40] | Granite saw dust | Fine aggregate | Geopolymer concrete with varying NaOH molarities | 15 | 15 | Improved strength up to 14M NaOH | Workability may decrease | Utilization of waste granite saw dust | Chemical treatment to remove impurities |

| [54] | GP | Sand | M60 grade concrete with admixtures | 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 | 25 | Improved compressive, split tensile, flexural strength, and modulus of elasticity | Workability may decrease at higher replacements | Utilizes waste GP | Further optimization of admixture proportions |

| [55] | Crushed granite fine (CGF) | Sand | 1:1:2 and 1:1.5:3 nominal mixes | 0, 12.5, 25, 37.5, 50, 62.5, 75, 87.5, 100 | 25–37.5 | Improved compressive strength up to 37.5% replacement | Increased water demand | Utilizes waste GD | Optimize w/c ratio |

| [56] | GP | Sand | M60 grade concrete with admixtures | 25 | 25 | Improved compressive, split tensile, and flexural strength | Increased plastic and drying shrinkage | Utilizes waste GP | Optimize shrinkage reduction methods |

| [57] | GFs | Sand | 1:6 cement:sand mix for sandcrete blocks | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 100 | 15 | Improved compressive strength up to 15% replacement | Reduced strength at 5% replacement | Utilizes waste granite fines | Optimize mix ratios and curing conditions |

| [58] | GFs | Fine aggregate | M20 grade concrete (1:1.5:3) | 0, 5, 15, 25, 35, 50 | 35 | Improved compressive and flexural strength up to 35% replacement | Reduced workability at higher replacement levels | Utilizes waste granite fines | Optimize w/c, use plasticizers |

| [59] | GP | Sand | M30 grade concrete with admixtures | 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 | 25 | Improved compressive and split tensile strengths up to 25% replacement | Higher plastic and drying shrinkage | Utilizes waste GP | Optimize particle size distribution |

| [60] | CGF | River sand | Various mixes with 0–100% CGF | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100 | 20 | Improved up to 20% replacement | Higher water demand | Conservation of river sand, waste utilization | Not specified |

| [61] | GP | River sand | GP0, GP25, GP50, GP75, GP100 | 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 | 25 | Improved up to 25% replacement | Higher drying shrinkage | Utilization of waste GP | Not specified |

Utilization of GW as PR of cement in concrete: A comparative analysis of recent studies

| Ref. | Material used | Material replaced | Mix Id description | Granite waste replacement (%) | Suggested replacement (%) | Influence on mechanical property | Limitation | Sustainability aspect | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | GD | Cement | GD2%, GD4%, GD6%, GD8%, GD10% | 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 10% | 6 | Improved up to 6%, then decreased | Workability decreased as the GD content increased due to its high surface area | Reduces cement consumption | Using GD with superplasticizers to mitigate workability issues at higher replacement percentages |

| [28] | GWP and Marble waste powder (MWP) blend (1:1 ratio) | Cement | MGWP-0, MGWP-5, MGWP-10, MGWP-15, MGWP-20, MGWP-25, MGWP-30 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 | 10 | Improved up to 15%, then decreased | Workability reduction at higher % due to its high surface area | Reduces cement consumption, utilizes waste materials | Use with superplasticizer to improve workability at higher replacement percentages. |

| [34] | Granite waste sludge | Cement | Concrete with varying granite waste content | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 | 20 | Slight improvement up to 10% replacement, then decline | Reduced workability at higher replacement levels | Utilizes waste material, reduces cement consumption | Optimize mix design for higher replacement levels |

| [20] | GWD | Cement | 0, 5, 10, 20% GWD | 0, 5, 10, 20 | 10 | Increase up to 10%, decrease beyond | Max 20% tested | Reduces cement use, utilizes waste | Optimize particle size |

| [26] | GWP | Cement | W0-W40, PT0-PT40, PF0-PF40 | 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 | 5–10 | Slight decrease beyond 10% | Up to 40% tested | Reduces cement use | Use with superplasticizer |

| [21] | GS | Cement | C, GC10, GC20, GC30, GC40 | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 | 20 | Slight decrease up to 20%, significant decrease beyond | Up to 40% tested | Reduces cement use | Optimize particle size distribution |

| [62] | GD | Cement paste | PR-0.40–0 to PR-0.55–15 | 0, 5, 10, 15 | 15 | Increase | Up to 15% tested | Reduces cement content by up to 25% | Optimize particle size distribution |

| [63] | GWD | Cement | Mix 4 and Mix 7 | 10, 20% | 20 | Slight decrease in compressive strength, improved corrosion resistance | Slight strength reduction at higher replacement levels | Reduces cement usage, utilizes waste material | Further study on durability aspects |

| [18] | GS | Cement | OPC, 90OPC+ 10AF, 80OPC+ 20AF | 0, 10, 20 | 10–20 | Decreased strength, increased porosity | Reduced early-age strength | Utilization of waste, reduced clinker content | Optimize particle size distribution |

| [39] | GS (GS45 and GS25) | Cement | CM, GS45-10, GS45-20, GS25-10, GS25-20 | 10, 20 | 10–20 | Slight decrease in strength at normal temperature, comparable strength at high temperatures | Reduced early-age strength | Utilization of waste material | Achieve greater fineness of GS |

| [64] | GP | Cement | Nominal mix, Mix-1, Mix-2, Mix-3, Mix-4 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 | 10 | Improved strength up to 10% replacement | Decreased strength beyond 10% | Utilizes waste material | Use of superplasticizers |

| [65] | GP | Cement | M25 grade concrete | 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 | 7.5 | Improved compressive, split tensile, and flexural strength | Workability decreased with increased GP | Utilization of waste GP | Not specified |

| [23] | Granite quarry sludge (processed granite [PG] and processed granite sludge [PGS]) | Cement | Mortar with PG and PGS | 0, 5, 10 | 10 (PGS) | Marginal strength loss for PGS | Workability may decrease for higher replacements | Utilizes waste material | Further grinding to improve performance |

| [66] | GD | Cement | M60 grade concrete with w/c ratio 0.45 | 0, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 | 5 | Improved strength at 5% replacement, decreased at higher levels | Reduced strength at >5% replacement | Utilizes waste GD | Reduce w/c ratio to compensate for strength loss |

| [67] | Marble and granite residues (MGR) | Cement | w/c 0.5 and 0.65, 450 and 346 kg·m−3 cement | 0, 5, 10, 20 | 5 | Decreased strength with increasing MGR content | Reduced mechanical properties at higher replacement levels | Utilizes waste material, reduces cement consumption | Optimize particle size distribution |

| [13] | Red granite dust (RGD) | Cement | Natural aggregate concrete (NAC) and recycled aggregate concrete with w/c 0.4, 0.34 | 0, 20, 30, 40, 50 | 30 | Comparable or improved strength up to 30% replacement | Reduced workability at higher replacement levels | Utilizes waste GD | Optimize particle size distribution |

| [68] | GS | Cement and limestone filler | A: Control; B: 5% cement replaced; C: 10% cement replaced; D: 20% cement replaced; E: 20% filler replaced; F: 40% filler replaced; G: 100% filler replaced | 0, 5, 10, 20 (cement replacement) 20, 40, 100 (filler replacement) | 100 (for filler replacement) | Improved compressive strength when used as filler replacement | Higher drying shrinkage | Utilization of waste material | Optimizing particle size distribution |

These tables collectively illustrate the potential of granite waste to enhance concrete properties while promoting sustainability. They serve as a valuable reference for researchers and engineers seeking to optimize concrete mixes for improved mechanical properties and environmental benefits, emphasizing the necessity for further studies to address identified limitations and enhance the practical application of granite waste in construction.

3.3 Recent advances in constitutive modeling and engineering applications

Recent research demonstrates significant enhancement in concrete properties through optimized granite waste incorporation. Jain et al. [31] reported substantial improvements with combined glass powder (20%) and GP (30%) as cement replacements, achieving 24.8 and 12.72% strength increases, respectively. Durability aspects show notable progress, with Ghorbani et al. [20] documenting enhanced resistance to chloride penetration and carbonation in concrete containing up to 20% GWD. Microstructural investigations by Saxena et al. [14] revealed a denser, more compact structure in geopolymer concrete incorporating up to 15% GWP, supported by findings from Jain et al. [31] regarding reduced porosity in optimally blended mixes.

3.4 Implications for sustainable construction

The granite industry’s waste generation, comprising 50–60% of total production [16], presents significant opportunities for sustainable construction practices. Utilizing granite waste in concrete applications addresses both waste management challenges and reduces environmental impact through decreased cement consumption. Kim et al. [27] highlighted the potential for reducing cement-related CO₂ emissions, while Lieberman et al. [35] demonstrated enhanced performance through optimal blends of granite waste and supplementary materials. Current implementation challenges include the need for standardized mix design procedures to ensure consistent performance across applications, comprehensive long-term durability assessment protocols to validate material performance over time, and refined quality control measures for industrial-scale production, particularly regarding moisture content management and particle size distribution optimization. These aspects require continued research attention while establishing a framework for practical implementation in sustainable construction. This systematic analysis provides clear guidelines for granite waste utilization in concrete while identifying specific areas requiring further investigation, ultimately contributing to the advancement of sustainable construction practices through waste material valorization.

4 Influence of granite waste on concrete properties

Building upon the scientometric analysis presented in Section 2, which revealed significant research interest in granite waste utilization across engineering and materials science domains, further examines how granite waste influences concrete properties when used as partial replacement for either sand or cement. This analysis aims to establish clear relationships between replacement percentages and concrete performance while providing evidence-based guidance for practical applications.

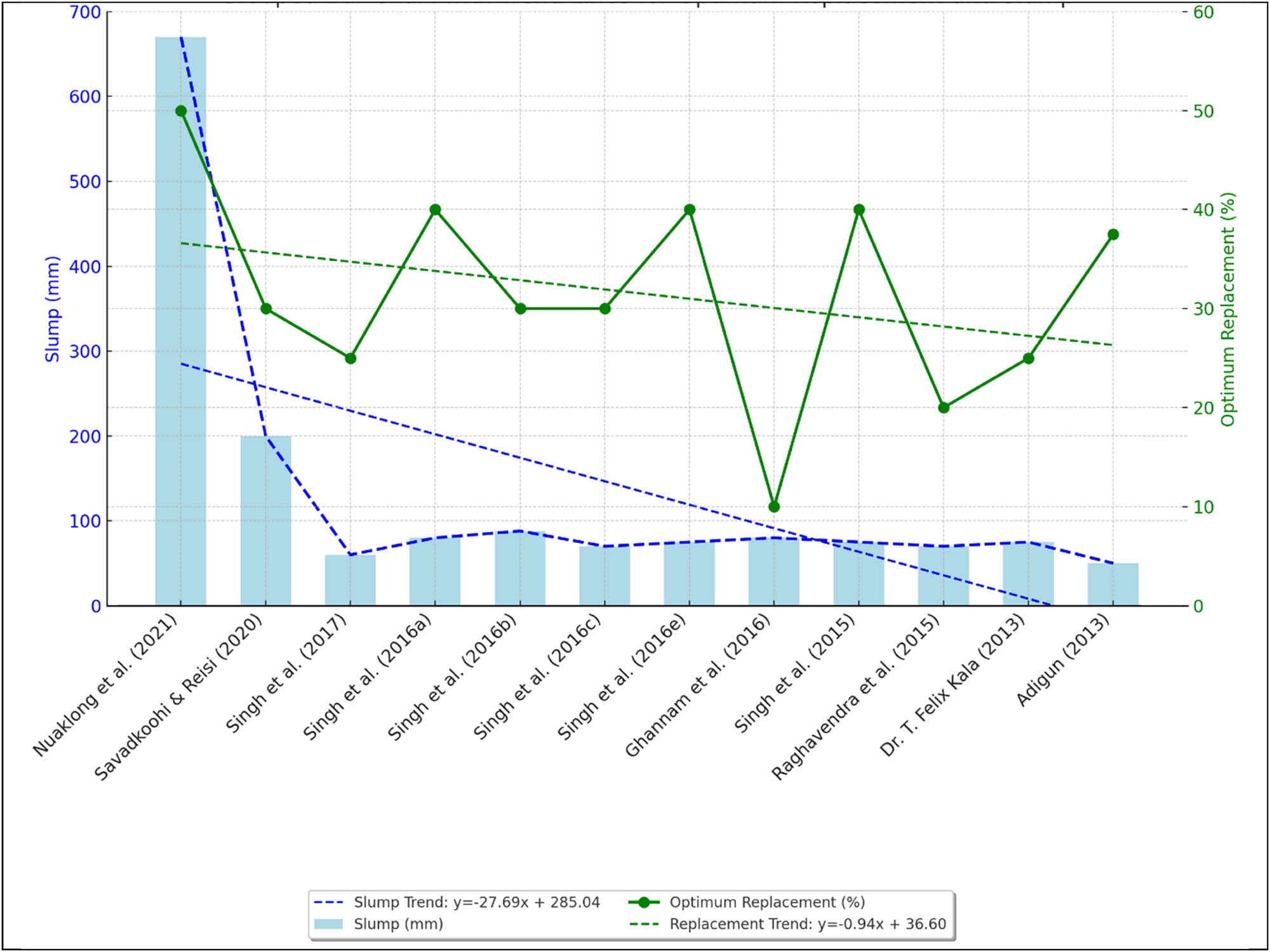

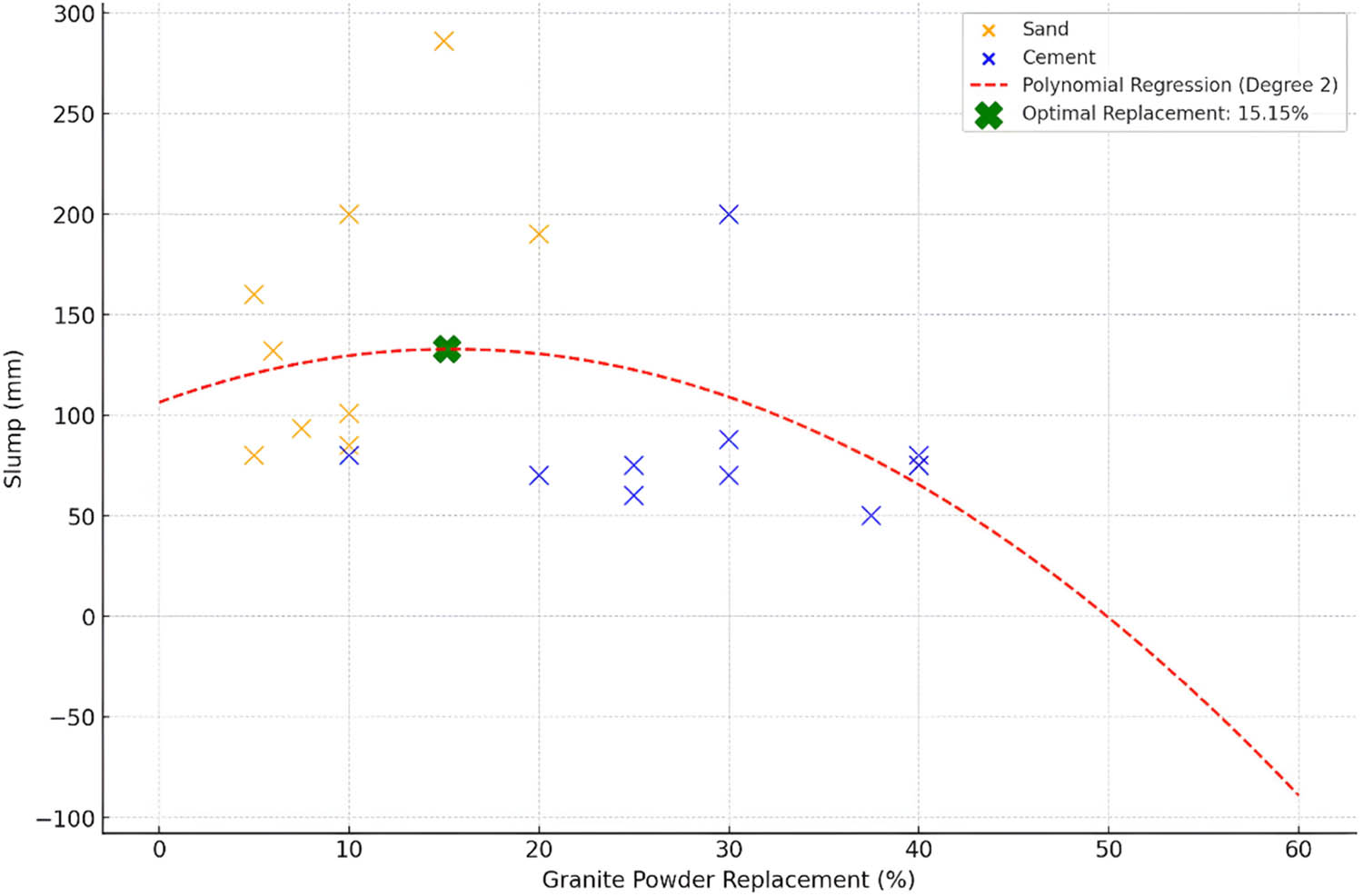

4.1 Fresh concrete property

The workability of concrete containing granite waste exhibits distinct patterns depending on whether the waste replaces sand or cement, as evidenced by comprehensive data analysis presented in Tables 4 and 5 and illustrated in Figures 8 and 9. For cement replacement (Table 4), slump values generally ranged from 77 to 286 mm, with the trend analysis showing an average of 110.25 mm. This moderate slump range suggests that granite waste can effectively maintain concrete workability when replacing cement at optimal levels. Studies have demonstrated that for M25 grade concrete (w/c ratio 0.45, cement content 380 kg·m−³), 10% GP replacement achieved slump values of 125–132 mm [28]. Higher-grade M60 concrete with w/c ratio 0.45 showed slump of 160 ± 20 mm at 5–7.5% GD replacement when tested at 27 ± 2°C with superplasticizer dosage of 0.8% [66]. For M30 grade concrete (w/c 0.50), slump values of 203–286 mm were recorded at 15% replacement under controlled lab conditions of 25 ± 2°C [62]. Also, the trend analysis of slump values, though showing natural variation due to diverse testing conditions across studies, demonstrates consistent patterns when analyzed through polynomial regression. For cement replacement applications (Figure 8), the analysis reveals a clear trend with optimal workability maintained at 10–15% replacement levels, despite variations in mix parameters. Similarly, for sand replacement (Figure 9), the data show systematic behavior with peak performance around 20–25% replacement. The comparative analysis of Figure 10 further validates these trends through statistical correlation, showing how proper moisture correction leads to predictable workability patterns across different replacement levels.

Studies on partial replacement of cement with granite waste in concrete mixtures

| Ref. | Material used | Material replaced | Slump (mm) | Mix Id description | Granite waste replacement (%) | Suggested optimum replacement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | GD | Cement | 143, 138, 132, 125, 118 | GD2%, GD4%, GD6%, GD8%, GD10% | 2, 4, 6, 8, 10% | 6% |

| [28] | GWP and MWP blend (1:1 ratio) | Cement | 116, 109, 101, 94, 88, 82, 77 | MGWP-0, MGWP-5, MGWP-10, MGWP-15, MGWP-20, MGWP-25, MGWP-30 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 | 10% |

| [34] | Granite waste sludge | Cement | Initial: Control: 175; GRC-10: 185; GRC-20: 190; GRC-30: 240; GRC-40: 255 | Concrete with varying granite waste contents | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 | 20% |

| [69] | GWP | Cement | 75–90 | W0-W40, PT0-PT40, PF0-PF40 | 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 | 5–10% |

| [62] | GD | Cement paste | 203–286 | PR-0.40-0 to PR-0.55-15 | 0, 5, 10, 15 | 15% |

| [65] | GP | Cement | 93.5 (at 7.5%) | M25 grade concrete | 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 | 7.50% |

| [23] | Granite quarry sludge (PG and PGS) | Cement | 200 ± 2 for all mixes | Mortar with PG and PGS | 0, 5, 10 | 10% (PGS) |

| [66] | GD | Cement | 160 ± 20 | M60 grade concrete with w/c ratio 0.45 | 0, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 | 5% |

| [67] | MGR | Cement | 68 ± 5.2 (w/c 0.5), 80 ± 8.4 (w/c 0.65) | W/c 0.5 and 0.65, 450 and 346 kg·m−3 cement | 0, 5, 10, 20 | 5% |

| [13] | RGD | Cement | 20–30 for 30% RGD | NAC and RAC with w/c 0.4, 0.34 | 0, 20, 30, 40, 50 | 30% |

Studies on partial replacement of sand with granite waste in concrete mixtures

| Ref. | Material used | Material replaced | Slump (mm) | Mix Id description | Granite waste replacement (%) | Suggested optimum replacement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32] | GWP | Nfs | 0 GW: 608–625; 25 GW: 628–640; 50 GW: 639–678 | Geopolymer concrete with varying granite waste content and moisture conditions | 0, 25, 50 | 50% |

| [41] | GWP | Natural river sand | l-0: ∼140; l-50: ∼40; h-0: ∼170; h-50: ∼90 | Low-strength (l) and high-strength (h) concrete with varying granite waste content | 0, 20, 30, 50 | Not specified |

| [33] | GWP | Silica sand | Maintained at 200 ± 10 mm | Reactive powder concrete with varying w/b, sf/b, binder content, and granite waste | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 | 30% |

| [42] | GP | Fine aggregate | 100–150 | Concrete with varying GP content | 0, 20, 30, 40 | Not specified |

| [3] | GIB | Fine aggregate (sand) | 110 (0% GIB) to 60 (70% GIB) | GIB0, GIB10, GIB25, GIB40, GIB55, GIB70 | 0, 10, 25, 40, 55, 70 | 25% |

| [44] | GCW | River sand | 90 (0%), 41 (70%) at 0.30 w/c ratio | D0-D70, E0-E70, F0-F70 | 0, 10, 25, 40, 55, 70 | 25–40% |

| [16] | GCW | Fine aggregate (sand) | 107 (0%), 88 (30%), 80 (50%) | G0, G10, G20, G30, G50 | 0, 10, 20, 30, 50 | 30% |

| [12] | GCW | Natural sand | 85–50 | G0, G10, G20, G30, G50 | 0–50% | 30% |

| [46] | GCW | River sand | 120–41 | A0-F70 (0.30-0.55 w/c) | 0–70 | 25–40% |

| [48] | GP | Sand | 80 | MG0, MG5, MG10, MG15, MG20 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 | 10% |

| [49] | GCW | River sand | 100, 95, 85, 75, 65, 55 | G0, G10, G25, G40, G55, G70 | 0, 10, 25, 40, 55, 70 | 40% |

| [50] | GP | Fine aggregate | 85, 80, 75, 70, 65, 60 | GP0, GP5, GP10, GP15, GP20, GP25 | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 | 15–20% |

| [53] | GP | Fine aggregate | Decreases with increasing GP | M30 grade concrete | 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 | 15% |

| [54] | GP | Sand | GP0 (72), GP25 (75), GP50 (78), GP75 (80), GP100 (80), CC (70) | M60 grade concrete with admixtures | 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 | 25% |

| [55] | Crushed granite fine (CGF) | Sand | 45–51 | 1:1:2 and 1:1.5:3 nominal mixes | 0, 12.5, 25, 37.5, 50, 62.5, 75, 87.5, 100 | 25–37.5% |

| [60] | CGF | River sand | 33–38 | Various mixes with 0–100% CGF | 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100 | 20% |

Trends in slump values and optimum granite waste replacement percentages in cement across various studies (2013–2024).

Evolution of slump values and optimal granite waste substitution for sand in concrete mixtures (2013–2021).

Optimized GP incorporation: Comparative slump analysis for sand and cement substitution in concrete mixtures.

In contrast, sand replacement applications (Table 5) exhibited wider variability, with slump values ranging from 33 to 678 mm and an average of 458.67 mm. This broader range reflects the significant influence of granite waste’s physical properties, particularly its fineness and surface area, on concrete consistency. For M25 grade concrete, slump values of 100–150 mm were achieved at 25% granite waste replacement, with cement content of 350 kg·m−³ and w/c ratio of 0.48 [3]. High-strength M60 grade concrete with admixtures demonstrated slump values of 72–80 mm at 25% replacement under controlled temperature of 27 ± 2°C [54]. Notably, reactive powder concrete maintained slump of 200 ± 10 mm at 30% replacement with w/b ratio of 0.22 and silica fume content of 25% [33].

Based on the comprehensive data analysis from Tables 4 and 5, and trends illustrated in Figures 8 and 9, the polynomial regression analysis of slump value data from multiple studies reveals statistically significant trends despite natural experimental variations. The analysis presented in Figure 10 identifies an optimal granite waste threshold of 15.15%, specifically for M25-M30 grade concrete mixes. At this optimum range, M25 grade concrete (w/c ratio 0.45, cement content 380 kg·m−³) with polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer dosage of 0.8–1.2% exhibited consistent workability, showing slump values of 125–132 mm. The analysis reveals a critical convergence zone between 10 and 20% replacement where sand and cement substitution maintained desirable workability characteristics across M25-M30 grade concrete mixes. These findings were validated under standardized testing conditions (IS:1199) at a temperature of 27 ± 2°C and a relative humidity of 65 ± 5%, with consistent mixing duration of 3–5 min. The convergence zone demonstrates particular significance for practical field applications, suggesting an optimal incorporation range for granite waste in conventional strength concrete grades while maintaining desired workability parameters.

4.2 Mechanical attributes of concrete incorporating granite waste particle

The mechanical performance of concrete containing granite waste reflects the complex transition from fresh to hardened properties. Building upon workability findings, where optimal ranges were established at 10–20% for cement and sand replacement, this section examines how these proportions influence strength development. This analysis is crucial for understanding practical implementation parameters while considering the environmental benefits highlighted in scientometric analysis in Section 2.

4.2.1 Compressive strength

The statistical analysis of GP utilization in concrete, comprehensively presented in Table 6, demonstrates significant variations across different replacement levels. This statistical evaluation was conducted systematically through multiple analysis stages to establish reliable optimization thresholds. First, descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation) provided the baseline understanding of strength variations. This was followed by trend smoothing using moving averages to reduce data noise and identify consistent patterns. Finally, polynomial regression analysis enabled precise identification of optimal replacement thresholds while accounting for mix design parameters.

Statistical analysis of optimal GP replacement and compressive strengths for sand and cement

| Statistic | Sand | Cement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimum granite waste replacement (%) (PR with sand) | Maximum compressive strength (Mpa) at 28 days | Optimum granite waste replacement (%) (PR with cement) | Maximum compressive strength (Mpa) at 28 days | |

| Count | 29 | 29 | 17 | 17 |

| Mean | 23.62 | 40.78 | 14.32 | 46.58 |

| Median | 25 | 40.1 | 10 | 46 |

| Standard deviation | 8.44 | 9.37 | 7.92 | 10.77 |

| Variance | 71.24 | 87.81 | 62.77 | 116.15 |

| Minimum | 10 | 27.3 | 5 | 28.5 |

| Maximum | 40 | 66 | 30 | 72 |

| 25th percentile (Q1) | 20 | 33.95 | 10 | 39.32 |

| 75th percentile (Q3) | 30 | 47.76 | 20 | 51.4 |

| Range | 30 | 38.7 | 25 | 43.5 |

| Interquartile range (IQR) | 15.07 | 15.07 | 35.72 | 35.72 |

The observed data distribution across studies reflects real-world variations in experimental conditions including w/c ratios (0.35–0.55), curing temperatures (21–27°C), and testing ages (28–90 days). The statistical analysis in Table 6 quantifies this variation through standard deviation (8.44% for sand replacement, 7.92% for cement replacement) and IQRs, validating the reliability of identified optimal replacement ranges despite apparent data dispersion. For sand replacement, the mean optimal GP content is 23.62% with median 25%, showing substantial variability (standard deviation 8.44%, variance 71.24). The IQR of 15.07 suggests moderate dispersion in the middle 50% of the data. For cement replacement, lower mean optimal GP content of 14.32% (median 10%) indicates preference for conservative replacement, with range extending from 5 to 30%. Notably, despite lower optimal replacement levels, the mean compressive strength for cement replacement (46.58 MPa) exceeds that of sand replacement (40.78 MPa), suggesting potential efficiency advantages in cement substitution applications.

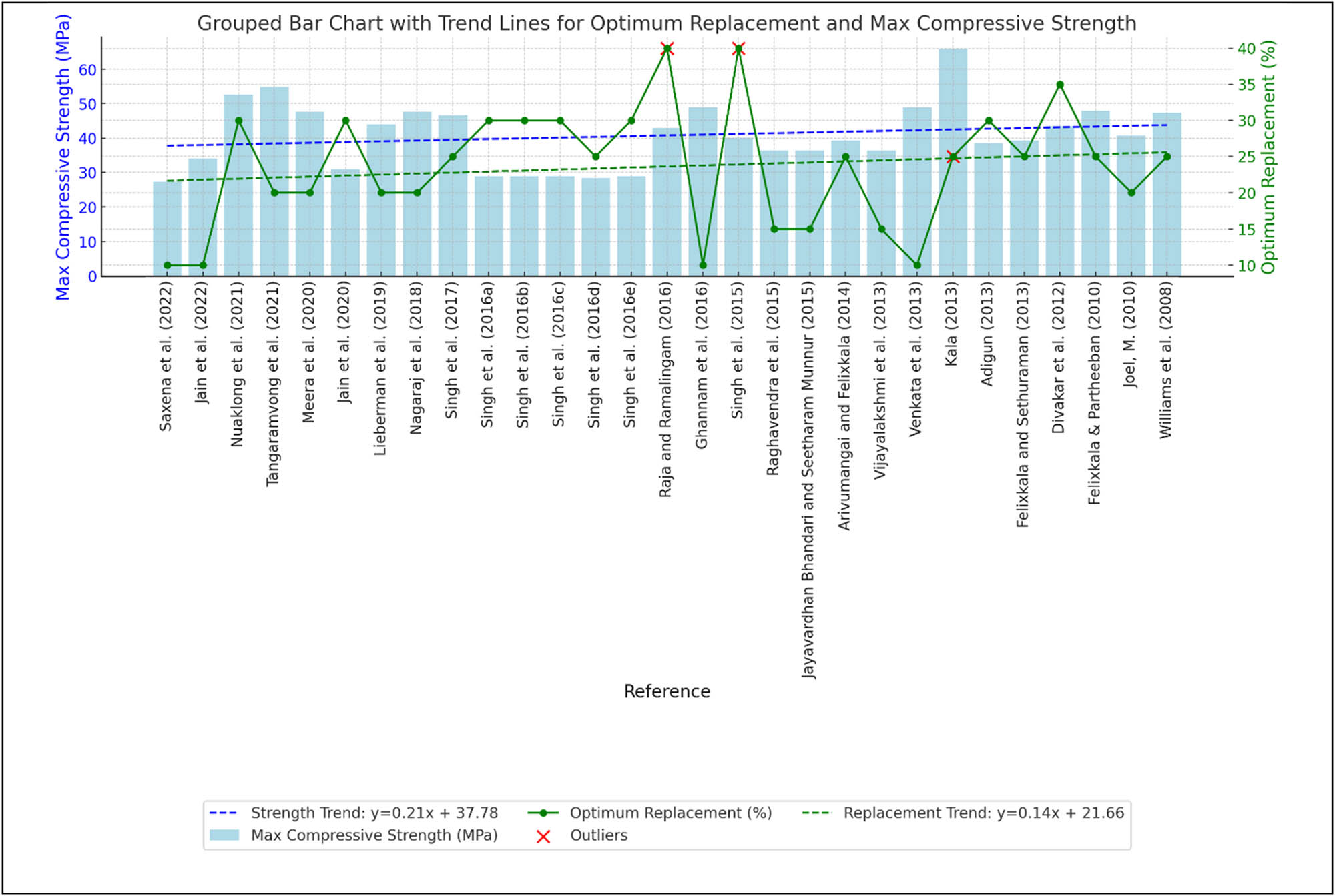

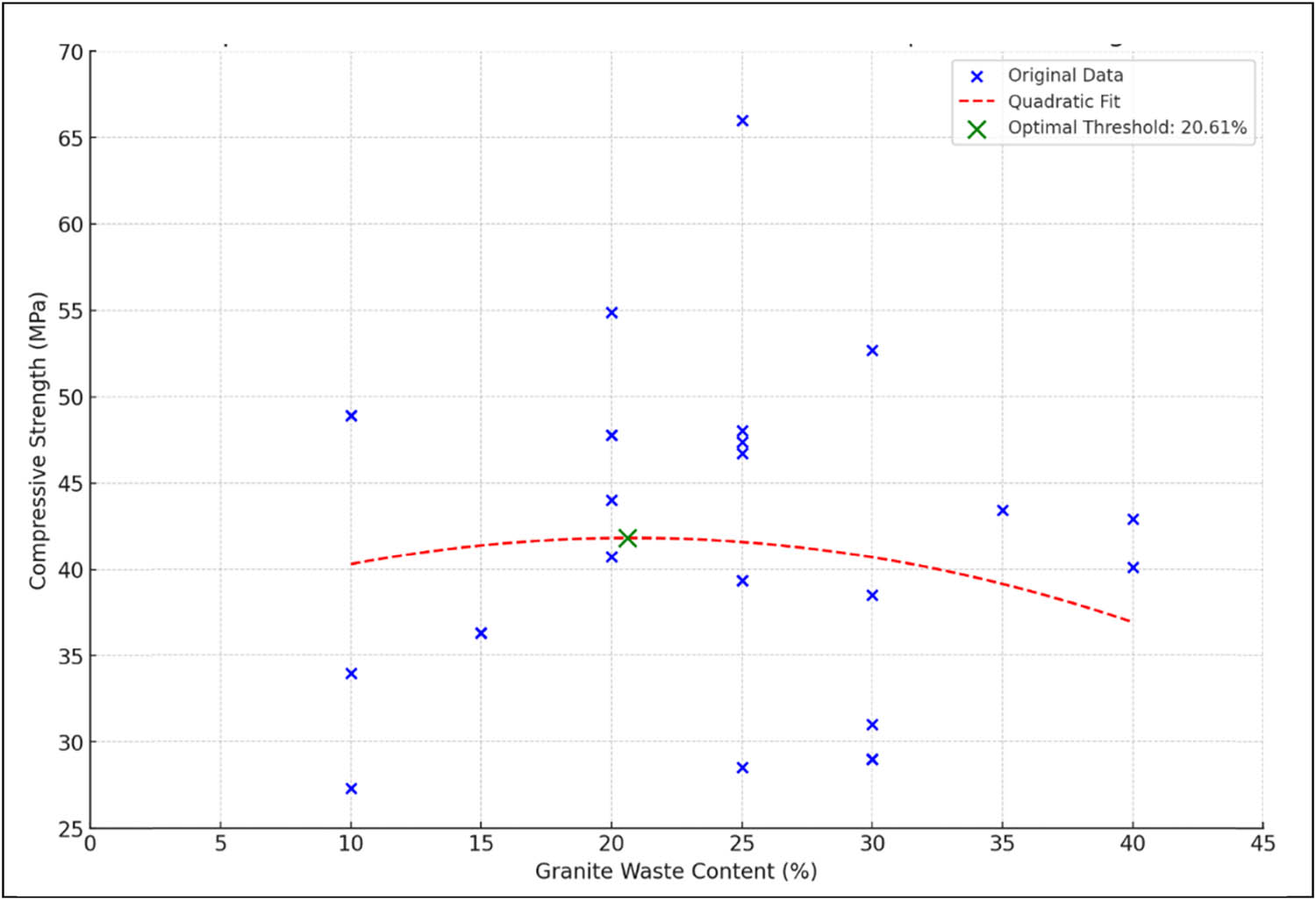

The incorporation of GP as a partial replacement for either sand or cement demonstrates distinct behavioral patterns in compressive strength development, as evidenced by the comprehensive statistical analysis in Table 6. For sand replacement applications, trend analysis through grouped bar charts (Figure 11) and comprehensive strength assessment (Figure 12) reveal optimal performance in M25-M60 grade concretes. Peak compressive strength of 66 MPa was achieved in M60 grade concrete at 25% replacement, using w/c ratio of 0.40, cement content of 425 kg·m−³, and superplasticizer dosage of 0.8–1.2%. This enhanced strength can be attributed to improved particle packing density, as GP’s physical properties (fineness modulus 2.13–3.68) and chemical composition (60–75% SiO2) enable better void filling while maintaining matrix integrity. The polynomial regression analysis (Figure 13) establishes 20.61% as optimal threshold, where the material’s compatible size distribution maximizes strength without compromising workability.

Grouped bar chart with trend lines for optimum replacement and max compressive strength of GP as PR of sand in concrete across studies (2008–2022).

![Figure 12

Comprehensive analysis GP as PR of sand (GP content vs compressive strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs compressive strength; [top-right] average compressive strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed compressive strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0084/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0084_fig_012.jpg)

Comprehensive analysis GP as PR of sand (GP content vs compressive strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs compressive strength; [top-right] average compressive strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed compressive strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).

Optimal granite waste content for maximum compressive strength in concrete with GP as partial replacement for sand.

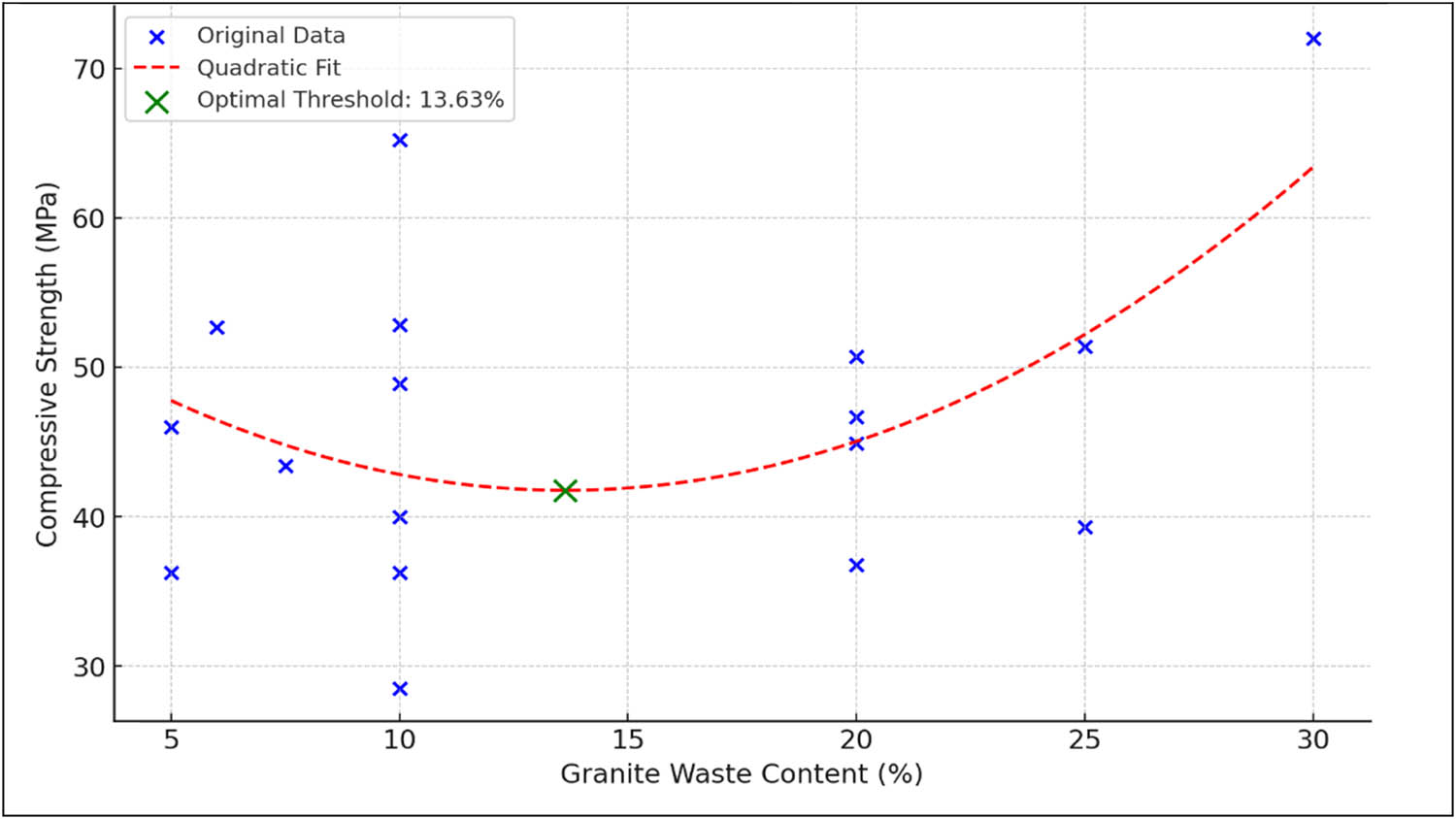

In cement replacement studies, performance trends (Figure 14) and strength correlations (Figure 15) demonstrate superior results at lower substitution levels, particularly in M30-M60 grades. Maximum strength of 72 MPa was recorded with 30% replacement in M60 grade concrete (w/c ratio of 0.34, cement content of 380 kg·m−³), with superplasticizer dosage 1.0–1.5%. The polynomial fit analysis (Figure 16) identifies 13.63% as optimal threshold, reflecting the balance between GP’s partial pozzolanic activity and filler effect in the cementitious matrix. This optimization correlates with GP’s high silica content enabling limited pozzolanic reactions while maintaining adequate cement content for proper hydration.

Grouped bar chart with trend lines for optimum replacement and max compressive strength of GP as PR of cement in concrete across studies (2010–2024).

![Figure 15

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of cement (GP content vs compressive strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs compressive strength; [top-right] average compressive strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed compressive strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0084/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0084_fig_015.jpg)

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of cement (GP content vs compressive strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs compressive strength; [top-right] average compressive strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed compressive strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).

Optimal granite waste content for maximum compressive strength in concrete with GP as partial replacement for cement.

This systematic optimization study validates GP’s potential for enhancing concrete performance while promoting sustainability. The regression models and extensive testing protocols establish optimal ranges of 20–25% for sand replacement and 10–15% for cement replacement across various concrete grades. These ranges consistently demonstrated superior strength development when following standardized mixing protocols (3–5 min), proper compaction, and curing conditions (temperature of 27 ± 2°C, relative humidity of 65 ± 5%). The findings provide practical implementation guidelines while highlighting GP’s effectiveness in sustainable concrete production.

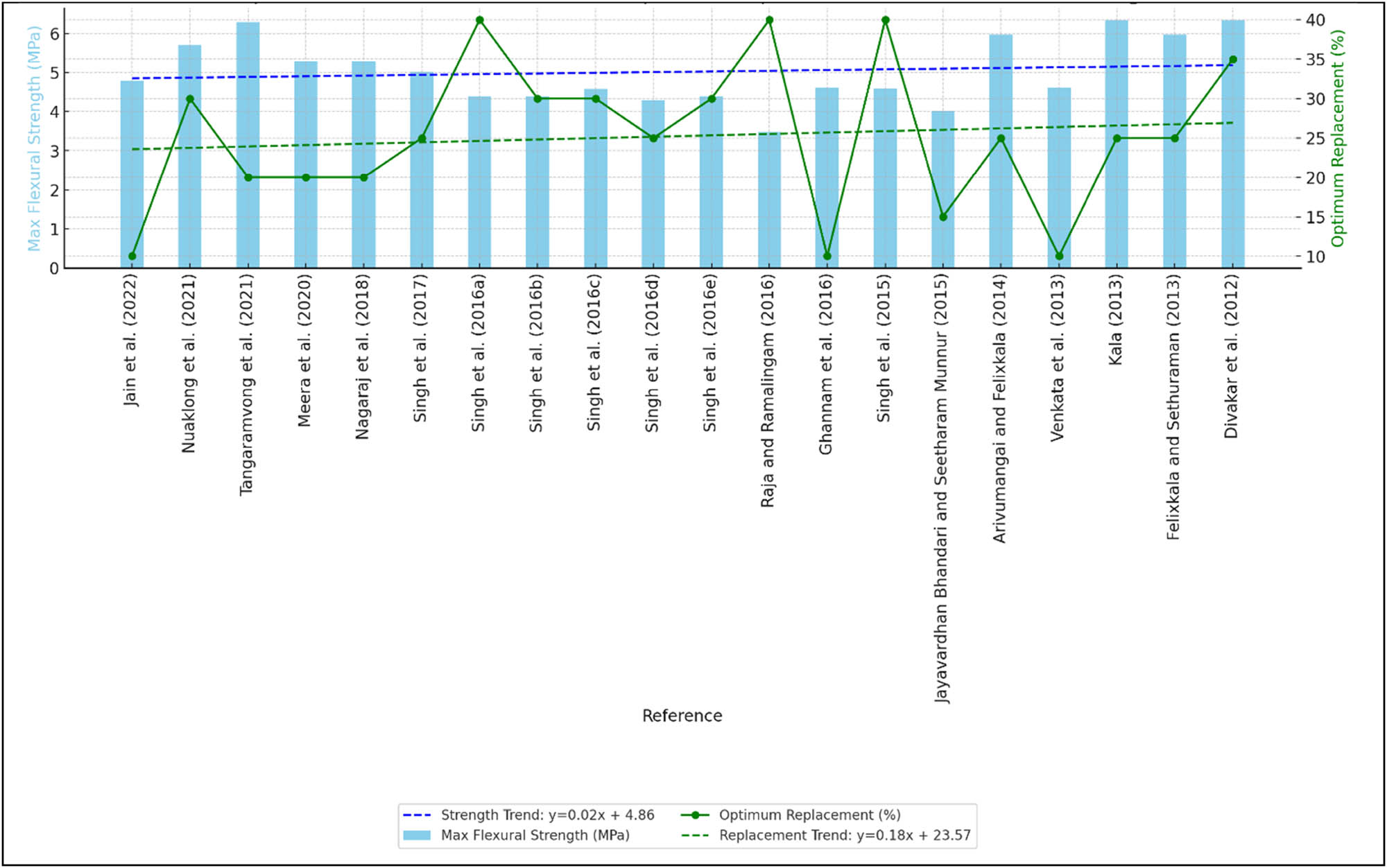

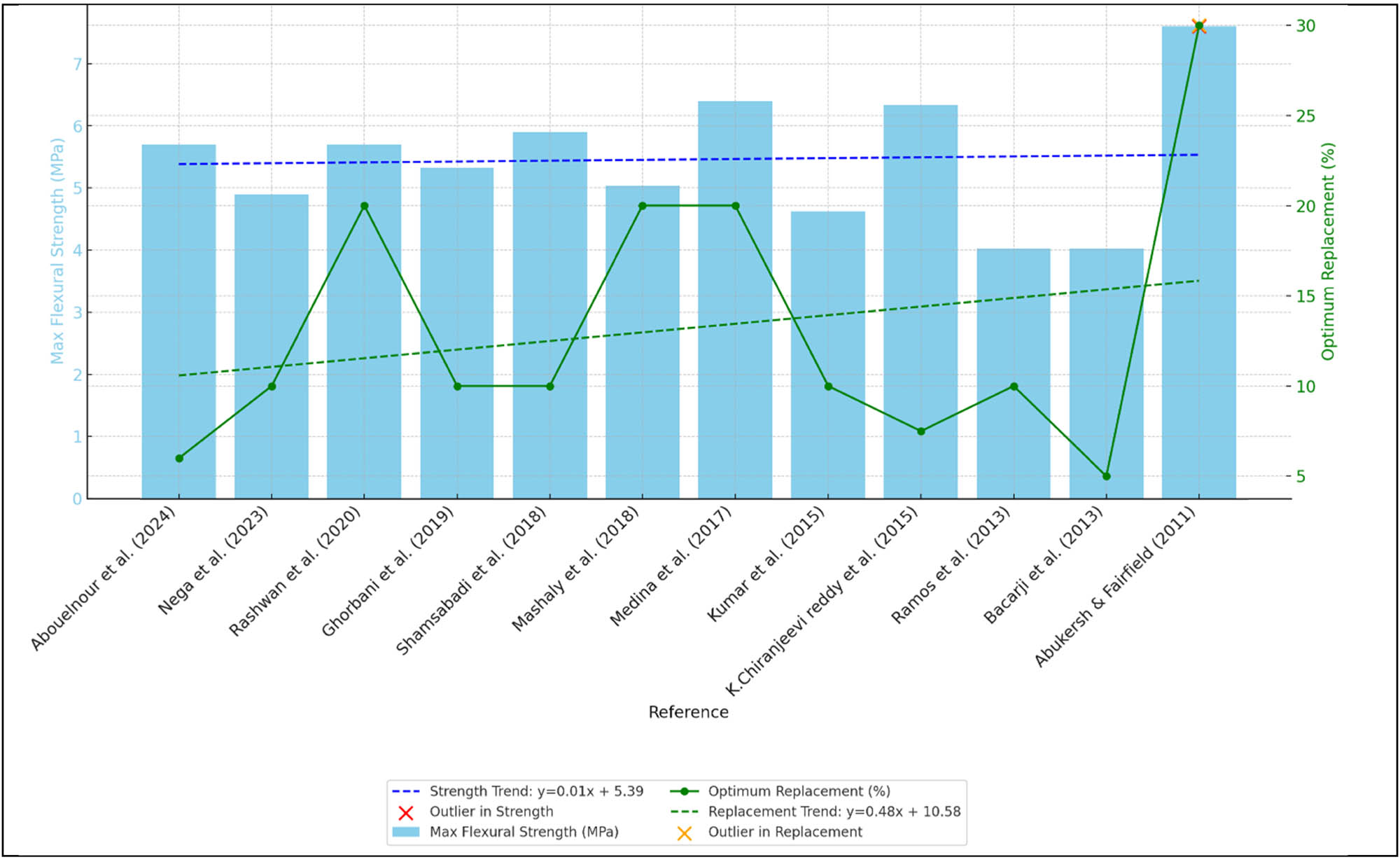

4.2.2 Flexural strength

The statistical analysis of GP utilization in concrete, presented in Table 7, demonstrates distinct performance patterns for sand and cement replacement applications. For sand replacement, mean optimal GP content of 25.25% (median 25%) shows consistent behavior across M25-M60 grade concretes, with standard deviation of 9.52% reflecting experimental variability. The range of optimal replacement spans from 10 to 40%, suggesting significant variability in research findings. This variability is further reflected in the standard deviation of 9.52% and variance of 90.72. The IQR of 10 indicates moderate dispersion in the middle 50% of the data. Notably, Kala [54] and Divakar et al. [58] reported the highest flexural strength of 6.34 MPa at 25 and 35% replacement, respectively, while Raja and Ramalingam [47] observed the lowest at 3.49 MPa with 40% replacement. For cement replacement, lower mean optimal content of 13.2% (median 10%) indicates more conservative replacement levels, with range 5–30% demonstrating potential across different concrete grades. The standard deviation of 7.53% and variance of 56.69 suggest slightly less variability than in sand replacement. Interestingly, despite lower optimal replacement levels, the mean flexural strength for cement replacement (5.46 MPa) is higher than that for sand replacement (5.02 MPa). Abukersh and Fairfield [13] achieved the maximum strength of 7.6 MPa at 30% replacement, while Ramos et al. [23] and Bacarji et al. [67] reported a minimum of 4.02 MPa at 10 and 5% replacement, respectively. The data distribution, as indicated by the 25th and 75th percentiles, shows that the middle 50% of optimal replacement levels for sand lie between 20 and 30%, while for cement, they range from 9.37 to 20%. This narrower range for cement replacement suggests more consensus among researchers on optimal levels for enhancing flexural strength.

Statistical analysis of optimal GP replacement and flexural strengths for sand and cement

| Statistic | Sand | Cement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimum granite waste replacement (%) | Maximum flexural strength (MPa) at 28 days | Optimum granite waste replacement (%) | Maximum flexural strength (MPa) at 28 days | |

| Count | 20 | 20 | 12 | 12 |

| Mean | 25.25 | 5.02 | 13.2 | 5.46 |

| Median | 25 | 4.7 | 10 | 5.51 |

| Standard deviation | 9.52 | 0.83 | 7.53 | 1.04 |

| Variance | 90.72 | 0.7 | 56.69 | 1.08 |

| Minimum | 10 | 3.49 | 5 | 4.02 |

| Maximum | 40 | 6.34 | 30 | 7.6 |

| 25th percentile (Q1) | 20 | 4.4 | 9.37 | 4.82 |

| 75th percentile (Q3) | 30 | 5.76 | 20 | 6.01 |

| Range | 30 | 2.85 | 25 | 3.58 |

| IQR | 10 | 1.36 | 10.62 | 1.18 |

These statistical findings underscore lower optimal percentages for cement replacement, coupled with higher mean strength, suggest that GP may be more efficient as a cement substitute for improving flexural properties, potentially offering both environmental and performance benefits.

Flexural strength development in GP-modified concrete reveals distinctive patterns that both complement and extend beyond compressive strength behaviors. Analysis of extensive experimental data, summarized in Table 7, demonstrates how replacement strategies significantly influence concrete’s flexural performance through complex material interactions.

For sand replacement, trend analysis through grouped bar charts (Figure 17) and comprehensive flexural assessment (Figure 18) reveals peak performance at specific mix designs. Maximum flexural strength of 6.34 MPa was achieved with M40 grade concrete at 25% replacement under controlled conditions: w/c ratio of 0.38, cement content of 425 kg·m−³, and superplasticizer dosage of 0.8–1.2% [54]. Similar performance (6.30 MPa) was observed at 35% replacement in M35 grade concrete with w/c ratio of 0.42 [58]. These enhancements stem from optimized particle distribution and interfacial bond strength. The polynomial regression analysis (Figure 19) identifies 23.95% as optimal threshold, reflecting GP’s ability to enhance matrix density without compromising flexural capacity. These exceptional results required precise parameter control, curing temperature regulated at 22 ± 2°C, and extended curing periods of 56 days under 100% relative humidity. Such conditions proved essential for maximizing GP’s contribution to flexural strength development, particularly through enhanced interfacial transition zone characteristics and optimized stress distribution patterns within the modified concrete matrix. Cement replacement studies demonstrate distinct behavior, as evidenced through performance trends (Figure 20) and strength correlations (Figure 21). Notable achievement of 7.6 MPa flexural strength occurred with 30% replacement in M60 grade concrete using specialized mix design: water-binder (w/b) ratio 0.35, extended 90-day curing at 21 ± 1°C, and polycarboxylate superplasticizer at 1.5% [13]. The quadratic fit analysis (Figure 22) establishes 13.63% as optimal threshold, showcasing consistent alignment with compressive strength optimization patterns. Recent studies (2020–2024) emphasize conservative replacement levels (10–15%), particularly for higher concrete grades (M40-M60) where flexural performance is crucial.

Grouped bar chart with trend lines for optimum replacement and max flexural strength of GP partially replaced with sand in concrete across studies (2012–2022).

![Figure 18

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of sand (GP content vs flexural strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs flexural strength; [top-right] average flexural strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed flexural strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0084/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0084_fig_018.jpg)

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of sand (GP content vs flexural strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs flexural strength; [top-right] average flexural strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed flexural strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).

Optimal granite waste content for maximum flexural strength in concrete with GP as PR for sand.

Grouped bar chart with trend lines for optimum replacement and max flexural strength of GP partially replaced with cement in concrete across studies (2011–2024).

![Figure 21

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of cement (GP content vs flexural strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs flexural strength; [top-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range; [bottom-left] smoothed flexural strength trend; [bottom-right] average flexural strength in each granite waste content segment).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0084/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0084_fig_021.jpg)

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of cement (GP content vs flexural strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs flexural strength; [top-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range; [bottom-left] smoothed flexural strength trend; [bottom-right] average flexural strength in each granite waste content segment).

Optimal granite waste content for maximum flexural strength in concrete with GP as PR for cement.

Recent studies (2020–2024) show an increasing preference for conservative replacement levels, particularly in cement substitution applications. This shift reflects a growing appreciation for long-term durability considerations and practical implementation challenges in field conditions. The convergence of optimal ranges across mechanical properties suggests inherent relationships between GP content and concrete performance. For field implementation, mix designs should carefully consider: temperature control (21–27°C), extended curing periods (56–90 days), proper moisture conditioning, and appropriate superplasticizer dosage (0.8–1.5%) These parameters prove especially critical for high-performance applications where consistent flexural strength achievement is essential.

These findings support the broader objective of developing sustainable concrete solutions while maintaining or enhancing mechanical properties, as indicated by the scientometric analysis in Section 2. The demonstrated ability to achieve significant strength improvements while incorporating substantial GP content validates the material’s potential for reducing environmental impact in concrete production. Furthermore, the quadratic fit analysis reveals a critical relationship between replacement percentage and strength development, suggesting optimal ranges that balance performance enhancement with practical implementation considerations. This understanding enables more precise mix design optimization for specific application requirements while maintaining focus on sustainability objectives.

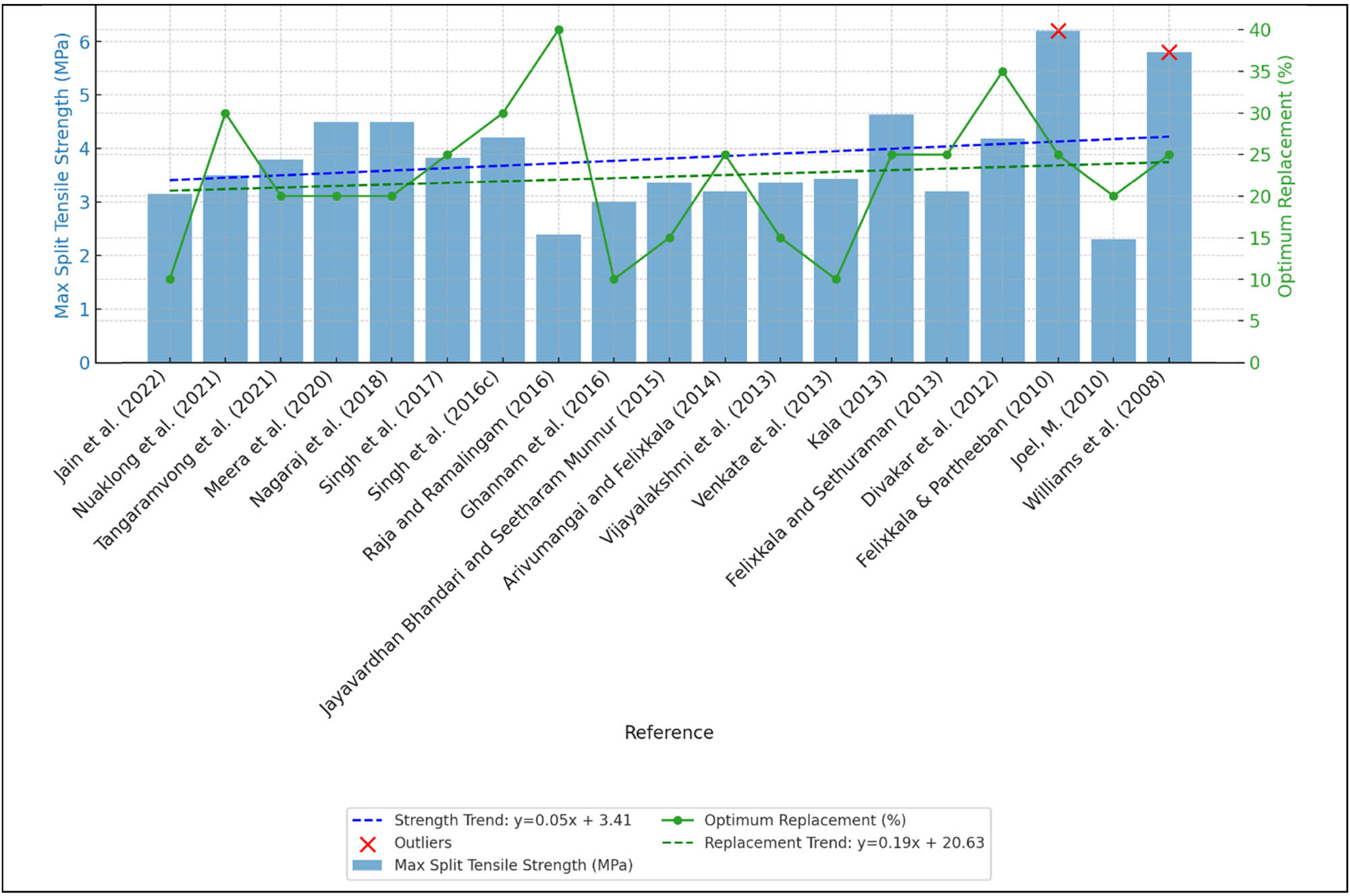

4.2.3 Split-tensile strength

The statistical characterization of GP replacement effects on split tensile strength, detailed in Table 8, reveals distinct patterns for sand and cement substitutions. For sand replacement, mean optimal GP content of 22.37% (median 25%) shows consistent performance, with standard deviation of 8.23% reflecting experimental variation across different concrete grades. The range spans from 10 to 40%, suggesting significant variability in research findings. This variability is reflected in the standard deviation of 8.23% and variance of 67.69. The IQR of 7.5 indicates moderate dispersion in the middle 50% of the data. Notably, Felixkala and Partheeban [59] reported the highest split tensile strength of 6.2 MPa at 25% replacement, while Joel [60] observed the lowest at 2.3 MPa with 20% replacement. Cement replacement exhibits lower mean optimal content of 12.96% (median 10%), with range 5–30% indicating viable application across various mix designs. The standard deviation of 8.08% and variance of 65.27 suggest similar variability to sand replacement. Interestingly, the mean flexural strength for cement replacement (3.79 MPa) is slightly lower than the mean split tensile strength for sand replacement (3.82 MPa). Shamsabadi et al. [69] achieved the maximum flexural strength of 5.4 MPa at 10% replacement, while Abd Elmoaty [66] reported the minimum of 3.1 MPa at 5% replacement. The data distribution, as indicated by the 25th and 75th percentiles, shows that the middle 50% of optimal replacement levels for sand lie between 17.5 and 25%, while for cement, they range from 7.5 to 20%. This narrower range for cement replacement suggests more consensus among researchers on optimal levels for enhancing flexural strength.

Statistical analysis of optimal GP replacement and split tensile strengths for sand and cement

| Sand | Cement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Optimum granite waste replacement (%) | Maximum split tensile strength (Mpa) at 28 days | Optimum granite waste replacement (%) | Maximum flexural strength (Mpa) at 28 days |

| Count | 19 | 19 | 13 | 13 |

| Mean | 22.37 | 3.82 | 12.96 | 3.79 |

| Median | 25 | 3.5 | 10 | 3.43 |

| Standard deviation | 8.23 | 1.01 | 8.08 | 0.75 |

| Variance | 67.69 | 1.02 | 65.27 | 0.56 |

| Minimum | 10 | 2.3 | 5 | 3.1 |

| Maximum | 40 | 6.2 | 30 | 5.4 |

| 25th percentile (Q1) | 17.5 | 3.2 | 7.5 | 3.275 |

| 75th percentile (Q3) | 25 | 4.36 | 20 | 3.83 |

| Range | 30 | 3.9 | 25 | 2.3 |

| IQR | 7.5 | 1.16 | 12.5 | 0.55 |

The analysis of split tensile strength in GP-modified concrete reveals intricate relationships between material composition and performance characteristics. Statistical evaluation presented in Table 8 demonstrates distinct behavioral patterns when GP functions as either sand or cement replacement. Analysis through grouped bar charts (Figure 23) and comprehensive strength mapping (Figure 24) demonstrates peak split tensile performance in M25-M60 grade concretes. Maximum strength of 6.2 MPa was achieved with M40 grade concrete at 25% sand replacement, utilizing w/c ratio of 0.42 under controlled conditions (temperature of 27 ± 2°C, relative humidity > 90%, 28-day strength development) [59]. The enhanced tensile capacity correlates with GP’s physical properties, as finer particles (fineness modulus of 2.13–3.68) improved interfacial bonding mechanisms. The polynomial regression analysis (Figure 25) establishes 24.64% as optimal threshold, where particle packing density maximizes without compromising matrix integrity. Cement replacement studies reveal optimized performance at more conservative levels, shown through trend analysis (Figure 26) and strength correlations (Figure 27). Notable achievement of 5.4 MPa tensile strength occurred with 10% replacement in M60 grade concrete using precise mix parameters: w/b ratio of 0.38, extended curing duration (56 days), and controlled temperature of 25 ± 2°C [69]. The quadratic fit analysis (Figure 28) identifies 12.00% as optimal threshold, demonstrating remarkable consistency with other mechanical property optimizations. M30-M40 grade applications showed particular sensitivity to curing conditions, requiring stringent quality control for consistent strength development.

Grouped bar chart with trend lines for optimum replacement and maximum split tensile strength of GP partially replaced with sand in concrete across studies (2008–2022).

![Figure 24

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of sand (GP content vs split tensile strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs split tensile strength; [top-right] average split tensile strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed split tensile strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0084/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0084_fig_024.jpg)

Comprehensive analysis of GP as PR of sand (GP content vs split tensile strength: [top-left] scatter plot of granite waste content vs split tensile strength; [top-right] average split tensile strength in each granite waste content segment; [bottom-left] smoothed split tensile strength trend; [bottom-right] highlighting optimal granite waste content range).

Optimal granite waste content for maximum split tensile strength in concrete with GP as partial replacement for sand.

Grouped bar chart with trend lines for optimum replacement and maximum split tensile strength of GP partially replaced with cement in concrete across studies (2010–2024).

![Figure 27