Abstract

Currently, there is a lack of research comparing the efficacy of machine learning and response surface methods in predicting flexural strength of Concrete with Eggshell and Glass Powders. This research aims to predict and simulate the flexural strengths of concrete that replaces cement and fine aggregate with waste materials such as eggshell powder (ESP) and waste glass powder (WGP). The response surface methodology (RSM) and artificial neural network (ANN) techniques are used. A dataset comprising previously published research was used to assess predictive and generalization abilities of the ANN and RSM. A total of 225 research article samples were collected and split into three subsets for model development: 70% for training (157 samples), 15% for validation (34 samples), and 15% for testing (34 samples). ANN used seven independent variables to model and improve the model, whereas RSM used three variables (cement, WGP, and ESP) to improve the model. The k-fold cross-validation validated the generalizability of the model, and the statistical metrics demonstrated favorable outcomes. Both ANN and RSM techniques are effective instruments for predicting flexural strength, according to the statistical results, which include the mean squared error, determination coefficient (R 2), and adjusted coefficient (R 2 adj). RSM was able to achieve an R 2 of 0.7532 for flexural strength, whereas the accuracy of the results for ANN was 0.956 for flexural strength. Moreover, the correlation between the ANN and RSM models and the experimental data was high. However, the ANN model exhibited superior accuracy.

Abbreviations

- ANFIS

-

neuro-fuzzy inference systems

- ANN

-

artificial neural network

- ANN-ICA

-

combination of ANN and imperialist competitive algorithm

- ANN-LM

-

Levenberg−Marquardt artificial neural network

- ANN-PSO

-

combination of ANN and particle swarm optimization

- APSO

-

adaptive particle swarm optimization

- BBO

-

biogeography-based optimization

- CaCO3

-

calcium carbonate

- CaO

-

calcium oxide

- CCD

-

central composite design

- CMNNs

-

constrained monotonic neural networks

- C–S–H

-

calcium–silicate–hydrate

- DOE

-

design of experiment

- ESP

-

eggshell powder

- FF

-

firefly algorithm

- FQ

-

full quadratic

- GA

-

genetic algorithm

- GA

-

genetic algorithms

- HPC

-

high-performance concrete

- HSC

-

high-strength concrete

- IA

-

interaction

- IPSO

-

improved particle swarm optimization

- LR

-

linear regression

- LWC

-

lightweight concrete

- MLR

-

multilinear regression

- MNHPSO

-

modified new self-organizing hierarchical PSO

- MSE

-

mean squared error

- NAC

-

natural aggregate concrete

- NHPSO

-

new self-organizing hierarchical PSO

- NLR

-

nonlinear regression

- POFA

-

palm oil fuel ash

- PQ

-

pure quadratic

- PSO

-

particle swarm optimization

- R 2 adj

-

adjusted coefficient

- R 2

-

determination coefficient

- RAC

-

recycled aggregate concrete

- RHA

-

rice husk ash

- RSM

-

response surface methodology

- SCC

-

self-compacting concrete

- SCM

-

supplementary cementing materials

- WGP

-

waste glass powder

1 Introduction

Modern academics are interested in recycling waste materials because of the rising demand for aggregates and cement in concrete and the need to responsibly protect natural resources [1]. The processes of cement manufacturing and extraction of natural aggregates require a significant amount of energy and contribute to the release of CO2 emissions [2,3,4]. The utilization of cementitious materials leads to the depletion of natural resources and environmental degradation. Researchers are currently prioritizing substituting cement and natural aggregates with alternative materials to advance the concept of environment-friendly construction [5]. Previous studies have examined alternative aggregates and cement materials [6]. The reuse of aggregates and cement can reduce the environmental impact of open trash disposal [7]. Substituting cement with mineral additives and waste materials is a viable solution to these issues [8]. Industrial wastes such as recycled glass [9], rubber tires [10], slag [11], plastic waste [12], foundry sand [13], fly ash [14,15], desulphurized gypsum [16], red mud [17], and eggshell powder (ESP) [18] significantly increased with serious environmental problems. Therefore, some previous studies resorted to including waste instead of cement or aggregates to reduce the environmental impact [19].

Eggshells, the tough outer layer of eggs, can be considered a type of agricultural waste. The yearly production of eggshells is expected to surpass 8 million tons owing to a consistent increase in egg production worldwide [20]. The formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel in cementitious composites requires calcium carbonate (CaCO3), a chemical component that is crucial to the composition of eggshells [18]. ESP has been used as an SCM in concrete and has improved its strength and durability owing to its high CaCO3 content and balanced mono-carbonates and ettringite [21]. Therefore, waste eggshell powder (WEP) can be used in place of cement and fine aggregates in building materials [22]. Recycling ESP and rice husk ash (RHA) as concrete additives improves the mechanical and microstructural characteristics of geopolymers [23]. The pozzolanic reaction between palm oil fuel ash and cement is improved by using ESP to raise the necessary calcium oxide level [24,25]. Hakeem et al. [26] improved ultra high-performance concrete (UHPC) mechanical characteristics and durability by blending rice straw ash as supplementary cementing materials (SCM) with nano ESP as an adjuvant. However, it is important to consider another type of SCM, waste glass powder (WGP), because of its high silica content and the significant volume that needs to be disposed of. The global amount of solid waste discarded in 2004 was predicted to be 200 million tons, with glass products accounting for 7% of this total [27]. Finely powdered glass powder below 38

The RSM is a comprehensive mathematical and statistical method for modeling and analyzing experimental issues [33]. Despite being widely used for experimental design and optimization, this method has limited use in the concrete industry [34]. For concrete technological optimization and modeling, neuro-fuzzy inference systems [35], ANN [36], genetic algorithms (GP) [37], and other methods have been used. An approach based on statistics called the design of experiment (DOE) is used to evaluate the outcomes of studies. DOE can minimize experiments, evaluate variable relationships, provide a mathematical model, and optimize experimental outputs. Furthermore, the utilization of the derived mathematical model allows the prediction of outcomes based on various parameters [38]. The slump flow, filling capacity, V-funnel flow time, and compressive strength were examined using the response surface to determine how the self-compacting concrete (SCC) mixing parameter affects the fresh and hardened attributes [39]. The combined effect of the water-to-cement ratio, steel fiber tensile strength, and volume fraction of fiber on the mechanical behavior of steel fiber-reinforced concrete was determined, and the RSM was used to find the best design parameters to maximize the concrete fracture energy [40]. The response surface approach was used to study the effects of the aspect ratio and steel fiber volume fraction on the steel fiber-reinforced concrete fracture parameters [41]. An RSM-based statistical model was created to predict self-compacting UHPC with hybrid steel fibers [42]. The response surface method optimized the typical ready-mixed concrete proportions for the slump flow [43].

ANNs are widely used and highly effective because they can classify data and acquire knowledge of input–output relationships for intricate situations [44]. An ANN is composed of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer [45]. The mechanical properties of high-performance concrete (HPC) [46], high-strength concrete (HSC) [47], FRP-confined concrete [48], self-compacting concrete (SCC) [49], lightweight concrete (LWC) [50], sulfate-resistant concrete [51], and concrete exposed to high temperatures [52] have been estimated using ANN in recent studies. An ANN analysis was used to predict the compressive strengths of cement mortar based on the microstructural characteristics extracted by digital image processing [53]. The experimental results for 179 specimens made with 46 combination proportions were used to train and test the ANN to predict the strength of MK-containing mortars at 3, 7, 28, 60, and 90 days [54]. Traditional correlation equations may not obtain results as good as the established ANN model for estimating the elastic modulus of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) [55]. According to recent study findings, ANN may be effectively utilized to forecast the carbonation depth of natural aggregate concrete (NAC) and to design NAC for durability [56]. ANN may predict better than other statistical models; however, like other classical optimization methods, its parameters are prone to local optimization rather than global optimization [57]. The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of granite was predicted using three non-destructive test indicators (pulse velocity, Schmidt hammer rebound number, and effective porosity) using three ANN-based models: Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm (ANN-LM), a combination of ANN and particle swarm optimization, and a combination of ANN and imperialist competitive algorithm (ANN-ICA)[58]. According to the recent research [59], improving the ANN model parameters using the swarm intelligence algorithm can increase its generalization ability for predicting the mechanical performance of conventional concrete. The application of ANN to predict the mechanical strength of recycled aggregate concrete revealed that certain networks did not yield accurate results. These significant inaccuracies may be attributed to the omission of cement type as an input parameter [60]. The accuracies of eight novel hybrid metaheuristic-based models, such as particle swarm optimization (PSO) improved particle swarm optimization, adaptive particle swarm optimization, new self-organizing hierarchical PSO, modified new self-organizing hierarchical PSO (MNHPSO), genetic algorithm, biogeography-based optimization, and firefly algorithm) were used to predict soil thermal conductivity [61]. The effect of SiO2 on the mechanical properties of concrete was examined using several models including linear regression, multilinear regression, nonlinear regression, pure quadratic, interaction, and full quadratic [62]. The bond strength of corroded reinforced concrete was estimated using convolution-based ensemble learning algorithms, which are becoming increasingly prominent in the field [63]. A unique data-driven machine learning strategy using constrained monotonic neural networks (CMNNs) to forecast the shear strength of FRP-strengthened reinforced concrete beams has advanced structural engineering [64]. Comparisons were made between several machine learning methods and the prediction of the mechanical properties of concrete [65], but one of the future studies of many researchers was to compare ANN and RSM [65,66,67,68]. A mathematical equation for the WEP and WGP blended in concrete validation and prediction has not been found. No research has predicted the flexural strength of concrete integrating eggshell and glass debris or provided mathematical calculations to save time and material. Past research has rarely examined the parametric effects of constituents.

To date, there has been a lack of research on the exploration of comparisons between the machine learning method and response surface method for the prediction of flexural strength. Researchers have recently shown a growing interest in examining how well-suited RSM and ANN modeling techniques are to find realistic solutions to issues. In this study, recycled waste glass and ESP were used as partial replacements for cement and fine aggregate to investigate their effects on concrete flexural strength using RSM and ANN, and their results were compared. A database of 225 literature specimens was used to build the ANN and RSM algorithms. This study used experimental data to build Levenberg-Marquardt and central composite design (CCD)-RSM models. We assessed and compared the accuracy of the built models using statistical measures of the mean square error (MSE), coefficient of determination (R 2), and correlation coefficient (R). To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare RSM with ANN to predict flexural strength, including waste materials, such as recycled waste glass and ESP.

2 Methodology

The study included dataset selection from previous research, ANN and RSM models, and essential parameters. Artificial neural fitting in MATLAB and CCD in design expert were used to build the prediction model by constructing input–target variable relationships. Literature datasets were used to ensure model reliability. Engineering judgment was used to improve the dataset quality and eliminate confusing human-error-related entries. R, R 2, and MSE assess the performance of the prediction model. These measures comprehensively assess model correctness and prediction capacity. A thorough parametric analysis examined how the key input elements affect concrete flexural strength prediction. This approach seeks to illuminate the relative importance of concrete strength elements.

2.1 Materials and selection of dataset

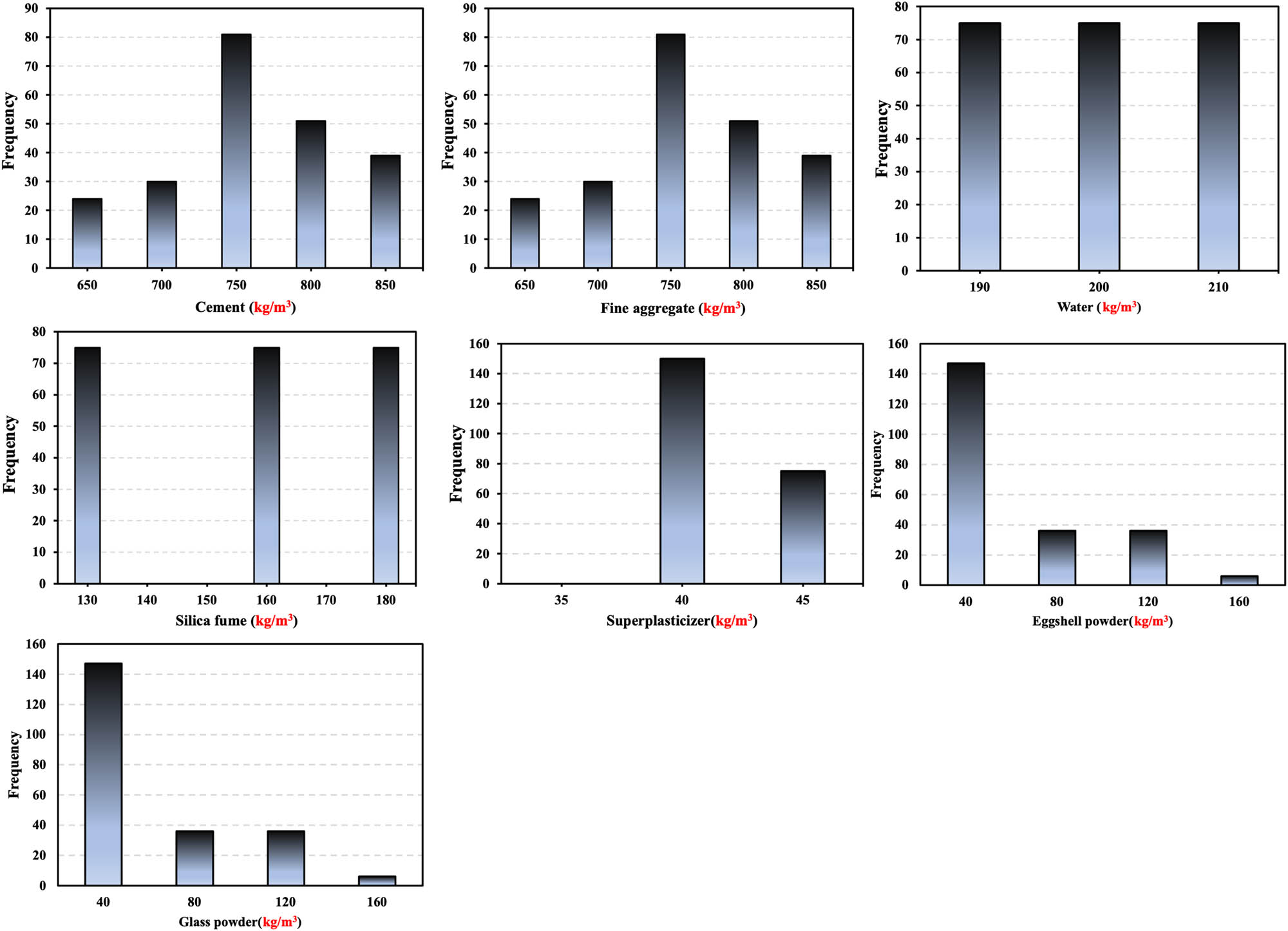

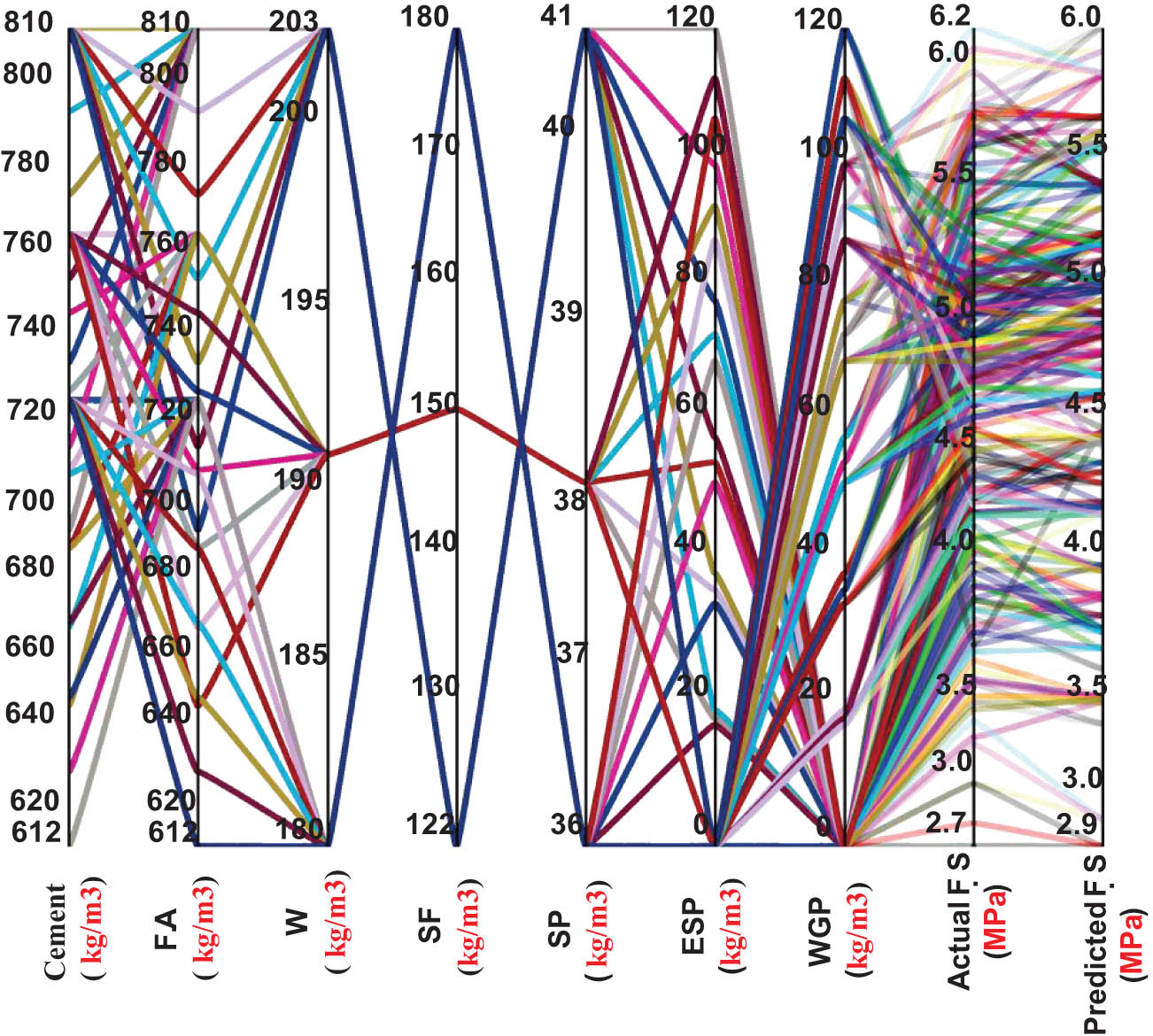

The production assessed normal concrete with a compressive strength of up to 40 MPa includes many components such as cement, fine aggregate, water, silica fume, superplasticizer, ESP, and WGP. The physical and chemical properties of waste materials, such as ESP and WGP, have been explained in literature [69,70]. Also, the mixing procedures are explained in literature [71,72]. Creating accurate predictive models requires a dependable and complete dataset. This study used a complete literature review to collect data from the previous studies. Dataset acquisition was complicated by concrete flexural strength modeling. This analysis included data from 225 concrete mixtures obtained from previous research. Cement (kg·m−3), fine aggregate (kg·m−3), water (kg·m−3), silica fume (kg·m−3), superplasticizer (kg·m−3), ESP (kg·m−3), WGP (kg·m−3), and flexural strength (MPa) were the inputs and outputs of the model. Table S1 presents the results of various experiments from the literature. A histogram of the input and target variables is shown in Figure 1. Using Pearson’s linear correlation, we also examined the linear correlation coefficients and their significance levels among the data factors [73]. A simple comparison was made in Table 1 between the amount of data and inputs used in this study and other studies.

Seven independent factors histograms.

Comparison of the amount of data and inputs between this study and other studies

| Machine learning algorithm | No. sample | Variable concrete content | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANN | 150 | Cement, silica fume, fly ash, waste marble powder, water, superplasticizer | [74] |

| ANN | 103 | External diameter of CFST composite column filled with recycled concrete, the thickness of the steel tube, length of specimen, the proportion of replaced recycled coarse aggregates, compressive strength of recycled concrete, yield stress of the steel tube | [75] |

| ANN | 13 | w/c, cement, water, coarse, fine aggregate, condensed milk can (tin) fibers | [76] |

| ANN | 40 | Beam dimensions, compressive strength of SCGC under ambient and marine exposure conditions, time of exposure, the tensile strength of the BFRP bar, tensile strength of steel reinforcement bar, and shear span-depth ratio | [77] |

| ANN | 50 | Cement, water, sand, aggregate, w/b, and ESP | [78] |

| ANN | 17 | Cement, w/c, coarse, fine aggregate, and foam volume | [79] |

| ANN | 55 | Cement, admixtures, water, coarse, fine aggregate, and superplasticizer | [80] |

| ANN | 17 | Cement, water, natural coarse aggregates, recycled coarse aggregates, and natural sand | [1] |

| ANN | 60 | Cement, admixtures, water, coarse, fine aggregate, and waste | [81] |

| ANN | 220 | Dry density (D), water/cement ratio (W/C), and sand/cement ratio (S/C) | [82] |

| ANN | 224 | Cement, fine aggregate, water, silica fume, superplasticizer, ESP, and WGP | The current study |

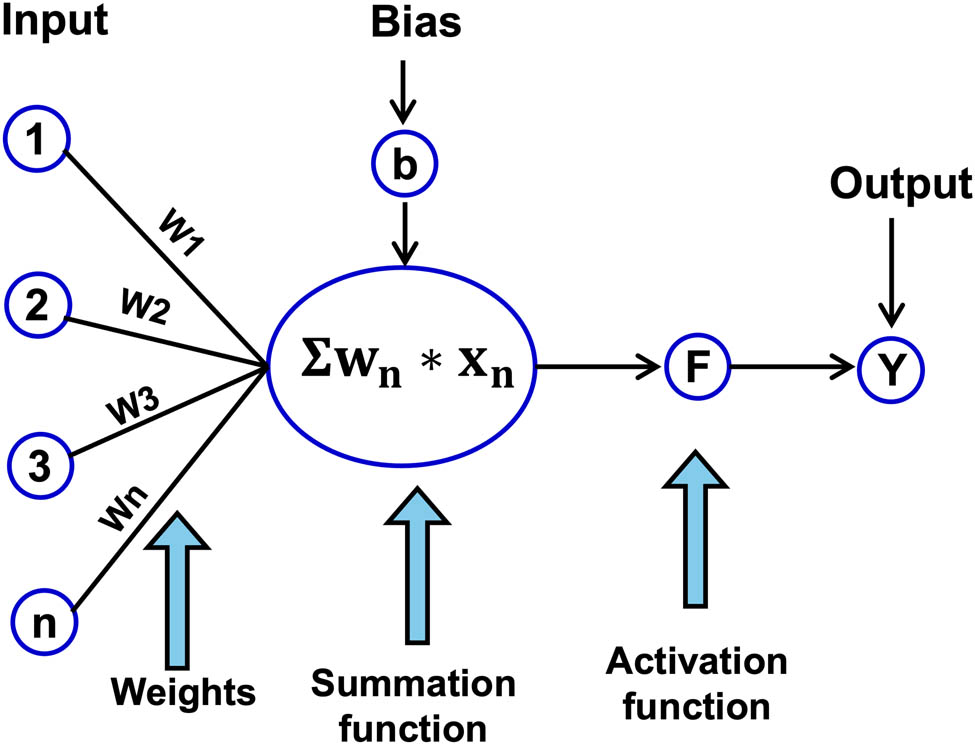

2.2 ANN

ANNs were built based on the concept of biological neural networks. ANNs are highly efficient methods for forecasting, grouping, identifying, and organizing data [83,84]. Their learning capabilities from training data are excellent and serve as black boxes. A fundamental neural network consists of an input layer that receives input variables and an output layer that generates output signals, as shown in Figure 2. The layers that connect the input and output layers in between are frequently referred to as the hidden layers. The choice of hidden layer is crucial because an excessive number of hidden layers leads to model overfitting, whereas a limited number of hidden layers leads to model underfitting [85]. In addition, the presence of additional hidden layers in the model increases estimation time [86]. The hidden layers consist of hidden neurons that are responsible for performing intermediate calculations that determine the output value of the neural network. Table 2 presents the statistical features of the data. The synaptic weight (w i ) is multiplied by the input (x i ). During the learning process, weights were adjusted to obtain a certain level of accuracy. Hidden layer neurons calculate the weighted total of the received signals and apply a bias (b). The lack of relevant input data eliminates bias, allowing the neuron to adjust the output, regardless of the input values. After the total is transmitted through activation function (f), y is the output.

Designer of single-layer neural network.

Input and output layer ranges, average values, and standard divisions

| Input | Output | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | Fine aggregate | Water | Silica fume | Superplasticizer | ESP | WGP | Flexural strength | |

| Min | 612.00 | 612.00 | 180.00 | 122.00 | 36.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.68 |

| Mean | 731.27 | 731.27 | 191.33 | 151.67 | 38.17 | 32.06 | 32.06 | 4.70 |

| Max | 810.00 | 810.00 | 203.00 | 180.00 | 40.50 | 121.50 | 121.50 | 6.21 |

| SD | 53.70 | 53.70 | 9.41 | 23.75 | 1.84 | 40.46 | 40.46 | 0.76 |

The learning algorithm was used in the ANN model because it is the fastest way to train small feedforward neural networks [44,87]. It is also the primary response to supervised learning situations such as those in this study. The sigmoid activation function is often used in research [88]. The variance between the actual and anticipated values was calculated using the algorithm. Adjusting the weights and bias using the learning process sends an error back to the network [89]. Normalize the subject parameter values between a suitable upper and lower limit value to avoid ANN low-learning-rate concerns. Eqs. (2) and (3) standardize the min–max normalization procedure for upper and lower limit values between [0, 1] [90].

Each ANN configuration was assessed using cross-validation. This approach was used to account for the limited size of the dataset, ensuring that the overall performance of the model was not affected and minimizing the possibility of overfitting. This method reduces the unpredictability of choosing a single test set and improves the dependability of the performance of the model [31]. This study implemented a 5-fold cross-validation technique, with the maximum value of k set at 5. The training set consisted of 80% of the available data, whereas the remaining 20% was used to test the ANN models. This particular k-max value was selected to strike a compromise between computational efficiency and the accuracy of the performance assessment, as advised for conducting a strong statistical analysis [82].

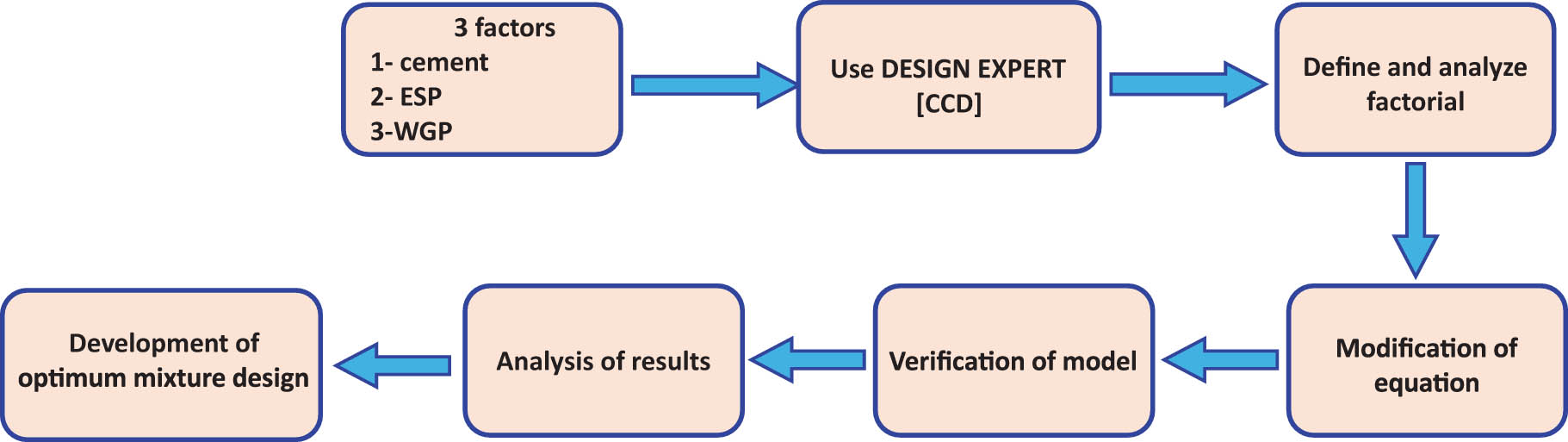

2.3 RSM

In RSM, independent variables (input parameters) interact with one or more responses (output parameters). It can estimate the output parameters and produce a precise model with less experimental data [91]. ANOVA divides the observed variance data into components for further testing [34]. The purpose of ANOVA in RSM is to determine the Sum of Squares, Mean Square, F-value, and p-value of the variables [92]. This strategy is used when multiple variables affect the responses. For each response, this study generated a CCD model and an RSM experimental design for second-order (quadratic) model prediction. The complete methodology employed in this study is shown in Figure 3. Table 3 presents these factors and their respective ranges of variation.

The schematic of RSM model.

Factors and factor levels for RSM

| Factor (kg·m−3) | Code | Factors level of code | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low level −1 | Intermediate level 0 | High level +1 | ||||

| Flexural strength | Response 1 | Cement | A | 646 | 728 | 810 |

| ESP | B | 0 | 60.75 | 121.5 | ||

| Response 2 | Cement | A | 612 | 686 | 760 | |

| ESP | B | 0 | 57 | 114 | ||

| Response 3 | Cement | A | 729 | 769.5 | 810 | |

| WGP | B | 20.25 | 70.88 | 121.5 | ||

| Response 4 | Cement | A | 612 | 686 | 760 | |

| WGP | B | 19 | 66.5 | 114 | ||

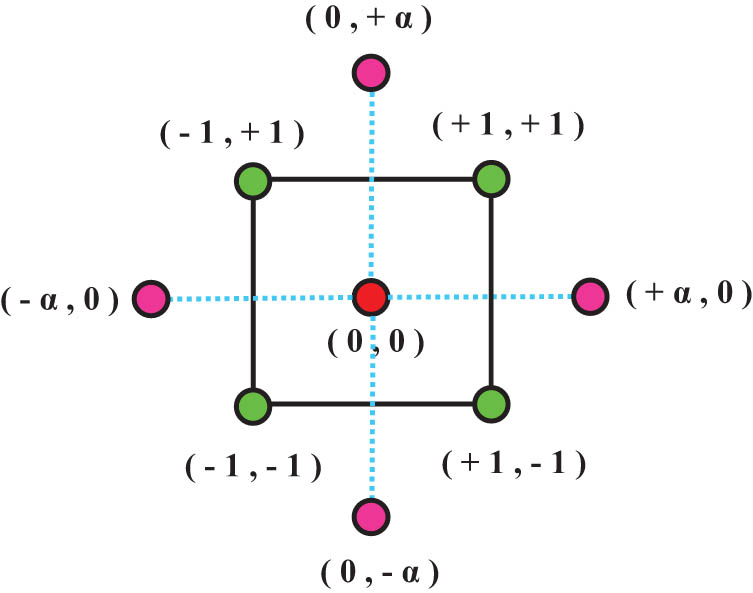

Design Expert software was utilized to perform CCD data analysis and accomplish multivariable optimization. The number of experiments was determined using Eq. (4).

where k, 2k, and C are explained in ref. [93]. The factorial, axial, and center points are schematically represented by the CCD in Figure 4. Based on Eq. (4), a total of 13 experimental points were recommended for the study. These points consisted of five factorial points without replication (2k), four axial points without replication (2k), and one center point with four replications (c).

Schematic representation of factorial, axial, and center points in CCD.

The best response was ascertained by applying a quadratic model or a second-order polynomial, Eq. (5).

where y is the anticipated response value, β 0 is the intercept of the model, β i represents the linear coefficients, β ii refers to the quadratic coefficients, and β ii is the coefficient of the variables’ interaction. x i and x j are the independent variables [94].

2.4 Indexes of performance

In addition, the output of the model was examined using several performance indices including MAE, MSE, RMSE, R, and R 2, as shown in Eqs. (6)–(10). Higher R 2 values imply a better fit between the analytical and predicted values, while lower RMSE values suggest more accurate prediction findings (a null value represents a perfect fit). The following equations determine the statistical parameters.

The equation represents the relationship between the observed value (O i ), expected value (P i ), total number of observed samples (N), and average forecasted value (P i ).

A20-index, a novel performance metric proposed by the authors, was also calculated to aid classification [95].

where M is the dataset sample number, and m 20 is the number of samples with an experimental-predicted ratio between 0.80 and 1.20. In a perfect predictive model, the a20-index value should be a unit value. The proposed a20-index offers a physical engineering benefit by indicating the percentage of samples that satisfy the expected values within ±20% of the experimental values.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Predicting flexural strength using RSM

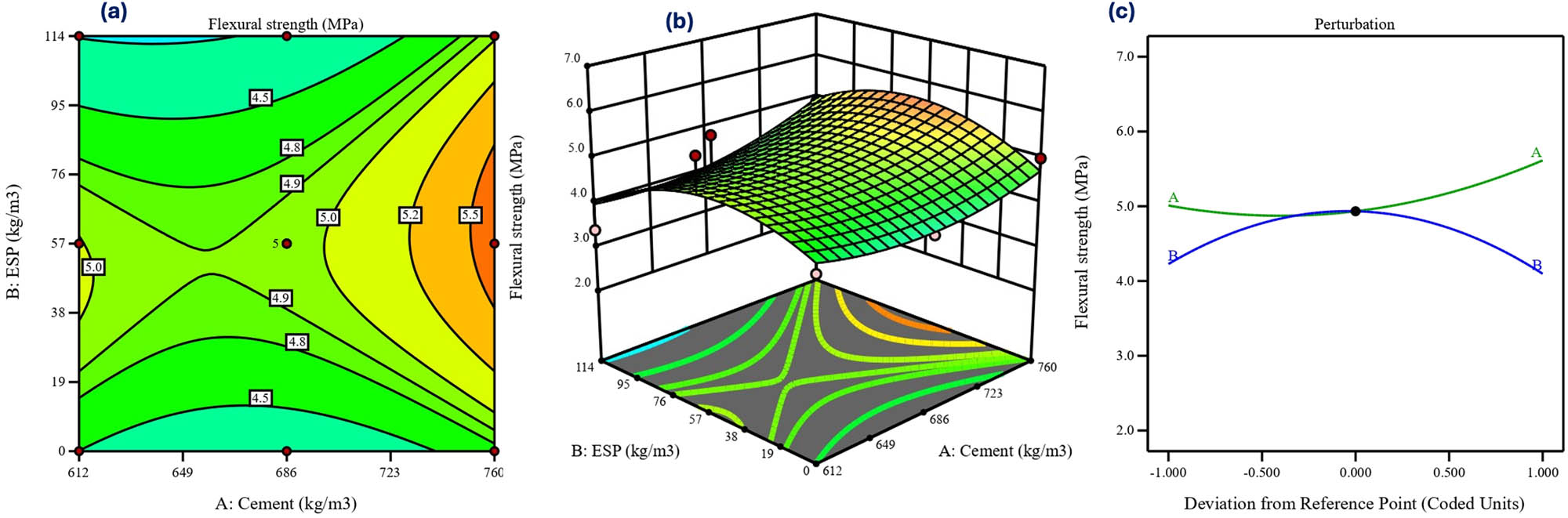

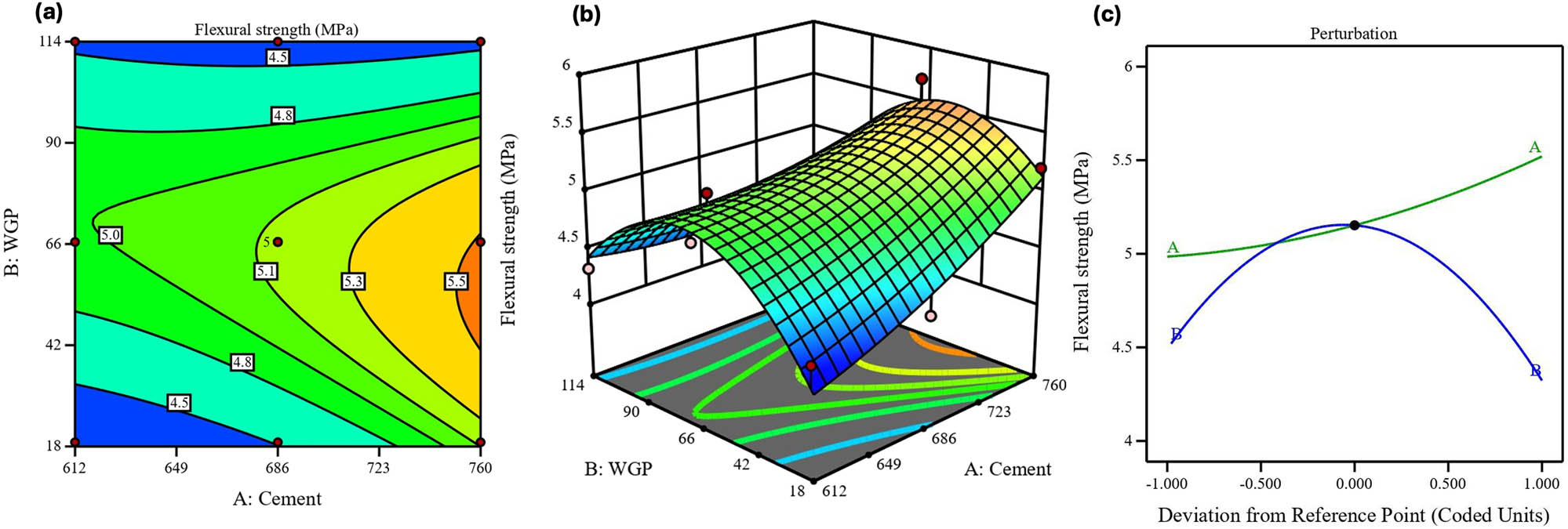

The RSM results for the flexural strength are shown in Figures 5–8. Figure 5 displays the flexural strength for response 1 as a 3D view, contour graph, and perturbation. Figure 5(a) shows that the contour lines along the ESP axis are more closely spaced than those along the cement axis, suggesting a substantial impact of the ESP on the flexural strength. Table 4 shows the ANOVA results for the parameters of the quadratic model of flexural strength. The predicted values of the flexural strength were 4.6, 4, 3.6, 3.6, and 3.8 MPa at cement contents of 646, 687, 728, 769, and 810 kg·m−3 ESP content of 24.3 kg·m−3. The equations generated from Eq. (12) were used to calculate the mathematical prediction of the flexural strength for response 1.

where A and B represent the variables (cement and ESP).

Flexural strength for response 1: (a) contour graph, (b) 3D view, and (c) perturbation plot.

Flexural strength for response 2: (a) contour graph, (b) 3D view, and (c) perturbation plot.

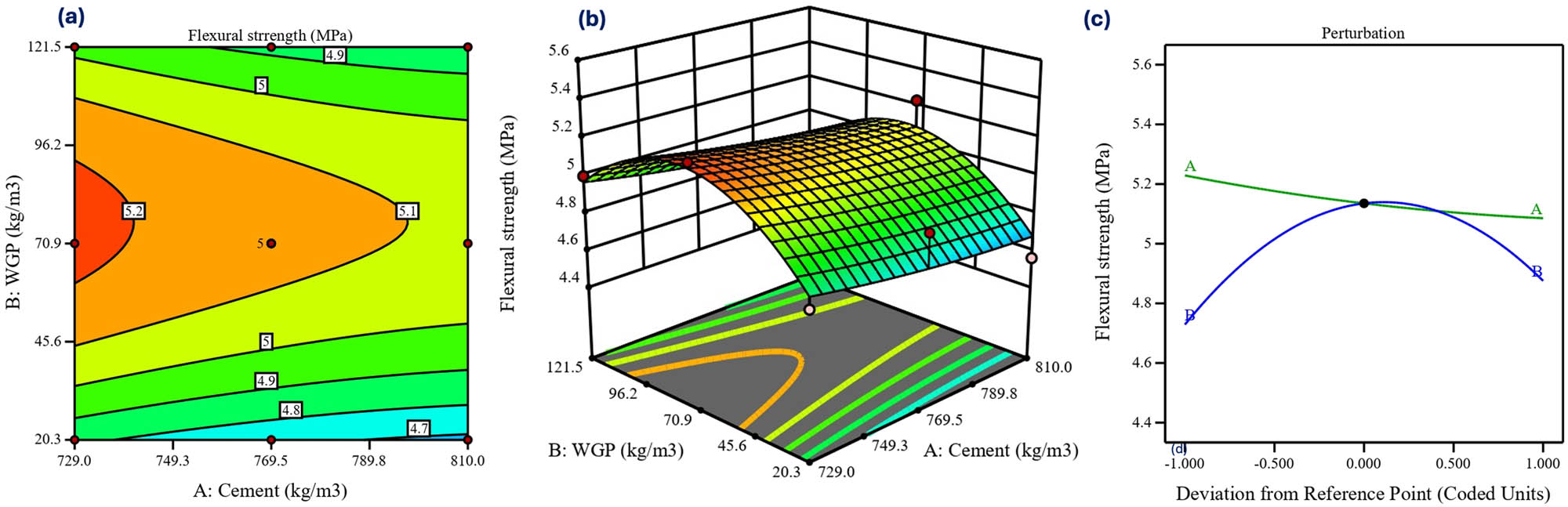

Flexural strength for response 3: (a) contour graph, (b) 3D view, and (c) perturbation plot.

Flexural strength for response 4: (a) contour graph, (b) 3D view, and (c) perturbation plot.

ANOVA results for the parameters of the quadratic model for flexural strength

| Source | Sum of squares | Mean square | F-value | p-value | Source | Sum of squares | Mean square | F-value | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response 1 | Response 2 | ||||||||||

| Model | 2.64 | 0.5284 | 3.63 | 0.0415 | Significant | Model | 2.38 | 0.4769 | 6.93 | 0.02071 | Significant |

| A-cement | 0.0888 | 0.0888 | 0.6095 | 0.4606 | A-Cement | 0.546 | 0.546 | 2.21 | 0.1806 | ||

| B-ESP | 1.27 | 1.27 | 8.71 | 0.0214 | B-ESP | 0.0253 | 0.0253 | 0.1027 | 0.758 | ||

| AB | 0.5112 | 0.5112 | 3.51 | 0.1032 | AB | 0.1482 | 0.1482 | 0.6004 | 0.4638 | ||

| A² | 0.6929 | 0.6929 | 4.75 | 0.0656 | A² | 0.397 | 0.397 | 1.61 | 0.2453 | ||

| B² | 0.0032 | 0.0032 | 0.0221 | 0.886 | B² | 1.64 | 1.64 | 6.65 | 0.0366 | ||

| Residual | 1.02 | 0.1457 | Residual | 1.73 | 0.2469 | ||||||

| Lack of fit | 1.02 | 0.34 | Lack of fit | 1.73 | 0.5754 | 1150.82 | <0.0001 | significant | |||

| Std. Dev. | 0.3817 | R² | 0.7214 | Std. Dev. | 0.4969 | R² | 0.7798 | ||||

| Mean | 3.61 | Adjusted R² | 0.6922 | Mean | 4.75 | Adjusted R² | 0.7156 | ||||

| C.V.% | 10.57 | Predicted R² | 0.6526 | C.V.% | 10.46 | Predicted R² | 0.6923 | ||||

| Adeq Pre. | 7.3265 | Adeq precision | 4.8337 | ||||||||

| Response 3 | Response 4 | ||||||||||

| Model | 0.4052 | 0.081 | 7.04 | 0.0117 | Significant | Model | 2.33 | 0.4667 | 9.8 | 0.0046 | Significant |

| A-cement | 0.0308 | 0.0308 | 2.68 | 0.1459 | A-Cement | 0.4302 | 0.4302 | 9.03 | 0.0198 | ||

| B-WGP | 0.0323 | 0.0323 | 2.8 | 0.1381 | B-WGP | 0.0413 | 0.0413 | 0.8661 | 0.383 | ||

| AB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | AB | 0.2809 | 0.2809 | 5.9 | 0.0455 | ||

| A 2 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.115 | 0.7445 | A 2 | 0.0277 | 0.0277 | 0.5817 | 0.4706 | ||

| B 2 | 0.3065 | 0.3065 | 26.61 | 0.0013 | B 2 | 1.47 | 1.47 | 30.88 | 0.0009 | ||

| Residual | 0.0806 | 0.0115 | Residual | 0.3335 | 0.0476 | ||||||

| Lack of fit | 0.0806 | 0.0269 | Lack of fit | 0.3335 | 0.1112 | ||||||

| Std. dev. | 0.1073 | R² | 0.8341 | Std. Dev. | 0.2183 | R 2 | 0.875 | ||||

| Mean | 4.99 | Adjusted R² | 0.7155 | Mean | 4.86 | Adjusted R 2 | 0.7856 | ||||

| C.V.% | 2.15 | Predicted R² | 0.6953 | C.V.% | 4.49 | Predicted R 2 | 0.7532 | ||||

| Adeq precision | 7.541 | Adeq precision | 9.6198 | ||||||||

As shown in Figure 5(b), the highest flexural strength predicted was 4.5 MPa at a cement content of 646 kg·m−3 and ESP 0 kg·m−3, while the lowest flexural strength predicted was 2.7 MPa at a cement content of 728 kg·m−3 and ESP 121.5 kg·m−3. The perturbation plots in Figures 5 and 6(c) illustrate the effect of the cement and ESP content on the flexural strength at a certain position. The high slope created by the parameters (cement and ESP concentrations) indicates that both elements are susceptible to flexural strength. A minimal change in the gradient was observed for component B (ESP), indicating its low sensitivity.

The mathematical prediction of the flexural strength of response 2 was calculated using the equations resulting from Eq. (13).

where A and B represent the variables (cement and ESP).

The F-value of 6.93 implies that the model is significant relative to the noise. There is a 20.71% chance that an F-value of this large could occur due to noise, as shown in Table 4. At a cement content of 686 kg·m−3, the flexural strength increases by 11.91, 16.67, 16.67, and 14.28% when the ESP content reaches 19, 38, 57, 76, and 95 kg·m−3, respectively. A decrease of 2.38% in the flexural strength was not observed with EPS content of 114 kg·m−3 as shown in Figure 6(a). As shown in Figures 5–8(b), the process order was quadratic. As shown in Figure 6(b), the highest predicted flexural strength was 5.8 MPa at 760 kg·m−3 of cement content and 57 kg·m−3 of ESP, while the lowest predicted flexural strength was 3.4 MP at 649 kg·m−3 of cement content and 114 kg·m−3 of ESP.

Figure 7 shows the flexural strength for response 3 as a 3D view, contour graph, predicted versus actual results, and perturbation. The mathematical estimate of the flexural strength for response 3 was computed using the equations derived from Eq. (14).

where A and B are the variables (cement and WGP, respectively).

The predicted flexural strength was 4.68, 4.99, 5.09, 5.03, and 4.84 MPa at WGP content 20.3., 45.6, 70.9, 96.2, and 121.5 kg·m−3, respectively, as shown in Figure 7(a). The model F-value of 7.04 implies the model is significant. There is only a 1.17% chance that an F-value this large could occur owing to noise, as shown in Table 3. As shown in Figure 7(a), the contour lines following the WGP axis were denser than those following the cement axis, indicating that the WGP had a greater influence on the flexural strength. As shown in Figure 7(b), the highest flexural strength predicted was 5.26 MPa at a cement content of 810 kg·m−3 and ESP 20.3 kg·m−3, while the lowest flexural strength predicted was 4.56 MPa at a cement content of 729 kg·m−3 and ESP 70.9 kg·m−3.

The flexural strength for response 4 was mathematically predicted using the formulae derived from Eq. (15).

where A and B represent the variables (cement and WGP).

Figure 8 displays the flexural strength of response 4 in 3D, contour graph, predicted vs actual, and perturbation. The model F-value of 9.80 implies the model is significant. There is only a 0.46% chance that an F-value this large could occur owing to noise, as shown in Table 3. Based on WGP contents of 18, 42, 66, 90, and 114 kg·m−3, the predicted flexural strengths were 4.8, 5.2, 5.3, 5, and 4.4 MPa (Figure 8(a)). As shown in Figure 8(b), the maximum predicted flexural strength was 5.7 MPa at 760 kg·m−3 of cement content and 60 kg·m−3 of ESP, while the minimum predicted flexural strength was 4.2 MP at 612 kg·m−3 of cement content and 18 kg·m−3 of ESP. P-values for response 4 of less than 0.0500 indicate that the model terms are significant. In this case, A, AB, and B² are the significant model terms, as shown in Table 4. The most significant factors were ranked by F-value or P-value with 95% confidence. Greater F-value and smaller “P” value (Prob. > F) indicate a more significant coefficient [96]. Model significance was indicated by the 30.88 F value. In addition, the model term is significant only when “Prob. > F” is less than 0.05.

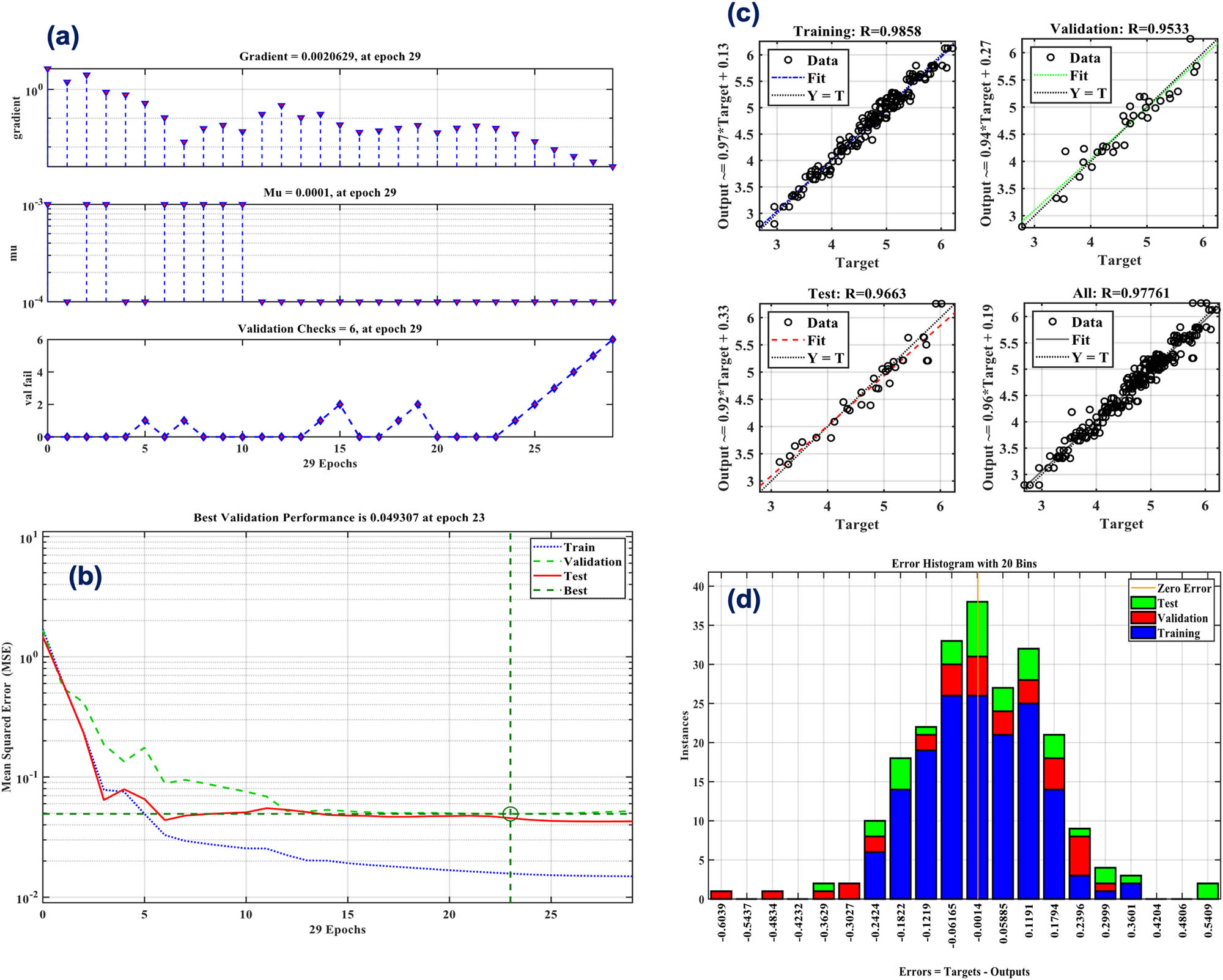

3.2 Predicting flexural strength using ANN

The training state of the ANN model is shown in Figure 9(a), which also indicates that the test terminated at epoch 29 and that the errors were repeated six times after epoch 0. The weights from the first epoch, 0, were used as the final weights and point of reference. As the errors occurred six times before the operation ended, the validation check was 6. As demonstrated in Figure 9(b), the MSE for the tested scenario in the training and validation datasets saturated with increasing epochs. The training process was completed at the 29th iteration, but it is important to remember that at this time, the error was larger than that in the 22nd iteration for both the validation and testing data as demonstrated in Figure 10. Table 5 displays R and MSE values for the flexural strength.

(a) Training state, (b) MSE, (c) R, (d) error histogram of the network for flexural strength.

R and MSE for training, validation, testing, and cumulative of ANN model

| Correlation coefficient (R) | MSE | |

|---|---|---|

| Training | 0.9857 | 0.01572 |

| Validation | 0.9530 | 0.04931 |

| Testing | 0.9667 | 0.04551 |

| All | 0.9776 | — |

Distribution of experimental and ANN predicted values with error percentage (%).

During the validation of the ANN model, epoch 23 achieved the highest performance. This is evident from the data presented in Figure 9(b), which shows an MSE of 0.049307. The nonlinear correlation between the input variables in Figure 9(c) indicates that the model can predict the flexural strength with an R 2 value of 0.956. The correlation coefficients (R) of training, validation, testing, and cumulative data were 0.9857, 0.9530, 0.9667, and 0.9776, respectively. Figure 9(d) displays the distribution of error bins, providing additional clarification of the distinction between the actual and expected values. The model’s predictions for concrete flexural strength demonstrated high accuracy, as seen by the significant proportion of the dataset falling into reduced error ranges. This is the absolute error distribution of the exp which is expected and reported in the experimental data. The ANN inputs and outputs are displayed as parallel coordinate plots in Figure 11. Table 6 presents the error evaluation results from the MAE, MSE, RMSE, R, R 2, and a20-index statistical analyses.

Parallel coordinates plot of variables of ANN for flexural strength.

Statistical checks were performed for all models

| MAE | MSE | RMSE | R 2 | R | a20 index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN model | 0.0102 | 0.0233 | 34.34 | 0.956 | 0.9776 | 0.996 |

The coefficients MAE, MSE, RMSE, R, and R 2 were evaluated, and it was found that R and R 2 achieved a high prediction rate, while MSE and MAE were small, which proved the success of the model in prediction [97]. Table 7 shows good agreement between the main network results and the k-fold cross-validation networks. This demonstrates the generalization ability of the network. The average R-value of the k-fold cross-validation network was 0.92303, demonstrating correctness.

K-fold cross-validation results

| K folds | K1 | K2 | K3 | K4 | K5 | Ava. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 0.8765 | 0.8942 | 0.97761 | 0.9432 | 0.9236 | 0.92303 |

3.3 Validation of RSM and ANN in mechanical properties

RSM and ANN approaches were used in this study to forecast flexural strength. Recently, RSM and ANN-based degrees of experimentation have become the most popular model and process optimization methods [98]. To gauge the precision of the mathematical models, we examined the correlation between observed and projected values. This significant correlation confirmed that the mathematical models accurately predicted the outcomes. Table S2 displays the statistical evaluation and performance of the RSM and ANN models. The results showed that for both methods, the projected values of the flexural strength model agreed well with the corresponding experimental values. Nevertheless, it has been observed that RSM models for pre-designed mixes have limitations in their ability to accurately anticipate reactions compared to ANN. To validate the adequacy of the final models, a determination coefficient (R 2) was used to evaluate the relationship between the actual and anticipated results of the RSM and ANN models. Using the statistical characteristics listed in Tables 5 and 6, the created RSM and ANN models were assessed. The results were substantially closer to 1, and the ANN-estimated R 2 was more accurate than that of the RSM approach. The ANN-generated models demonstrated increased predictive power and accuracy. As indicated by the lower MSE values that the ANN obtained in contrast to the RSM, the ANN performed better than the RSM.

4 Discussion

This study utilized an ensemble learning approach, specifically the Levenberg−Marquardt algorithm, in combination with CCD, to predict the flexural strength of concrete materials.

The results mentioned above demonstrate the ability of an ANN to predict actual results, and the accuracy of the predicted results was higher than that of the RSM to predict actual results [1]. The R coefficient is a statistical measure used to ensure the accuracy of the results. From the above results, it became clear that the R coefficient from ANN for flexural strength exceeded 0.9, which is accurate, as shown in many previous studies [86,87,89,99,100], whereas the R coefficient from RSM for flexural strength exceeded 0.8. Given the input data, the Levenberg algorithm model can effectively and accurately predict the flexural strength of concrete. The actual method is not necessary for users to understand, which simplifies and facilitates application [101]. Table 8 reveals that most researchers have used comparable input parameters. Data availability and variable significance have led researchers to employ fewer input variables. Literature R 2-values range from 0.67 to 0.956 in Table 8. The ANN model of this analysis showed a good R 2-value of 0.956, close to literature. This shows that the developed model is more accurate than the previous models. One difference between this study and others is the sample size [1].

Comparison of predictions of ANN model with current research

| Machine learning algorithm | R 2-value | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| ANN | 0.85 | [102] |

| ANN | 0.933 | [103] |

| ANN | 0.825 | [78] |

| ANN | 0.929 | [80] |

| ANN | 0.67 | [81] |

| ANN | 0.956 | The current study |

Sometimes, the RSM model is unable to achieve high accuracy in prediction, and this is due to the failure of the values of the variables to match the values of the RSM model, which results in low prediction accuracy [33]. A decrease in prediction accuracy was observed. For example, the accuracy of Response 4 for flexural strength was higher than that of the other responses, which proves that the mismatch of values between the laboratory variables and model variables resulted in a decrease in prediction accuracy. To verify the efficiency of the ANN model, the model used in this study was compared with those used in previous studies. The accuracy of prediction has been mentioned in many literatures [104,105,106]. To verify the validity of the RSM results, R 2 and P values are looked at. If R 2 is greater than 0.8 and P-value is less than 0.05, this proves the accuracy of the model in prediction. The greater the R 2 than 0.8 and the lower the P value than 0.05, the greater the accuracy of the predicted results [93,107,108].

ESP has many advantages of using in concrete. These features can be summarized as follows: eggshells are abundant in calcium carbonate. Calcium carbonate accounts for 95% of eggshells. This chemical molecule is identical to limestone and a cement ingredient, making it a feasible replacement for concrete cement [109]. Eggshells reduce concrete workability. According to previous studies, increasing eggshell content decreases workability. This is because eggshells absorb a large amount of water early in the casting process. The eggshell absorbs water to achieve good workability [110]. Eggshells increased the compressive strength of concrete by 6–35%. The ideal eggshell content varied between studies; however, most studies agreed on 10–15% for mechanical performance. The same range applies to concrete below M30, which uses eggshells and another substitute material [111].

5 Limitations and future studies

Note that the proposed optimum ANN and RSM system application field is defined by its design and training parameter settings. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the suggested ANN and RSM systems reliably predicted the parameter values between the lowest and maximum input parameters. ANN and RSM systems are limited for parameters exceeding these limits. Despite the promising results, the proposed ANN and RSM models should be used cautiously. The database is the largest in the relevant literature; however, it requires more experimental data. In particular, the limitations are related to the following:

Regarding RSM, the experimental data are missing some data related to −1, +1, 0, −α, and +α, which leads to a decrease in R 2.

ANN needs to collect more data with more variables to check the effect of these variables on prediction.

Future work can be summarized as follows:

Support vector machines, back-propagation neural networks, genetic programming, multilayer perceptron neural networks, and ANN with genetic algorithms are suggested to be used for predicting experimental data in future studies.

Using a 3D approach in future studies for the factors, axis, and center points in the CCD and making a comparison with the 2D approach could provide additional insights.

6 Conclusion

This research will significantly contribute to the field of sustainable construction by demonstrating the feasibility of using ESP and WGP as partial replacements for concrete. The predictive models developed will aid in optimizing mix proportions for enhanced performance, promoting sustainable practices in the built environment, and reducing the environmental impact of concrete production. Utilizing ANN and RSM, this study created a model that predicted flexural strength based on previous mixes that included waste components such as eggshells and WGP. The investigation yielded the following findings:

The lack-of-fit test results and high coefficients of multiple determinations (R 2) of the polynomial regression model showed that it could predict the concrete performance for the RSM model. The extraordinarily low P-value of the ANOVA data statistically supported all model parameters.

Data-based ANN and RSM models have shown promise for properly replicating concrete characteristics.

Based on the RSM analysis, the two most influential elements in predicting the flexural strength of concrete were cement (WSP), with R 2 = 0.7532.

A comparison of the comparative findings of the two approaches reveals that the ANN model outperforms the RSM, with a strong correlation coefficient (R 2) that is nearly equal to 1 (0.956) for flexural strength.

The maximum and minimum flexural strength predicted by ANN is 6 and 2.29 MPa, while the maximum and minimum predicted results in RSM are 5.03 and 2.86 MPa.

ANN can predict numerous previous results simultaneously, unlike RSM, which needs to group previous results to increase accuracy.

The development of reliable predictive models (RSM and ANN) for concrete flexural strength using ESP and WGP promotes sustainable buildings. It also encourages the use of waste materials in construction, lowering the environmental impact of concrete production.

This study could help develop a consistent ANN approach and RSM to predict concrete flexural strength quickly and reliably. The prediction method reduces lab time and cost.

Acknowledgments:

Shanxi Province Education Science “Fourteenth Five-Year Plan” 2024, the annual topic (GH-240751) 2024 Higher Science and Technology Innovation Project in Shanxi Province (2024L579).

-

Funding information: Shanxi Province Education Science “Fourteenth Five-Year Plan” 2024, the annual topic (GH-240751) 2024 Higher Science and Technology Innovation Project in Shanxi Province (2024L579).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

[1] Hammoudi, A., K. Moussaceb, C. Belebchouche, and F. Dahmoune. Comparison of artificial neural network (ANN) and response surface methodology (RSM) prediction in compressive strength of recycled concrete aggregates. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 209, 2019, pp. 425–436.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.119Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Sandanayake, M., Y. Bouras, R. Haigh, and Z. Vrcelj. Current sustainable trends of using waste materials in concrete – a decade review. Sustainability, Vol. 12, 2020, id. 9622.10.3390/su12229622Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Khan, M., A. Rehman, and M. Ali. Efficiency of silica-fume content in plain and natural fiber reinforced concrete for concrete road. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 244, 2020, id. 118382.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118382Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Khan, M. and M. Ali. Improvement in concrete behavior with fly ash, silica-fume and coconut fibres. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 203, 2019, pp. 174–187.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.103Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Dawood, A. O., H. Al-khazraji, and R. S. Falih. Physical and mechanical properties of concrete containing PET wastes as a partial replacement for fine aggregates. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 14, 2021, id. e00482.10.1016/j.cscm.2020.e00482Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Ahmad, S., O. S. B. Al-amoudi, S. M. S. Khan, and M. Maslehuddin. Effect of silica fume inclusion on the strength, shrinkage and durability characteristics of natural pozzolan-based cement concrete. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 17, 2022, id. e01255.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01255Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Pachideh, G., M. Gholhaki, and H. Ketabdari. Effect of pozzolanic wastes on mechanical properties, durability and microstructure of the cementitious mortars. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 29, Sep 2019, id. 101178.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101178Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Yang, R., R. Yu, Z. Shui, X. Gao, X. Xiao, X. Zhang, et al. Low carbon design of an Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) incorporating phosphorous slag. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 240, 2019, id. 118157.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118157Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Yin, W., X. Li, Y. Chen, Y. Wang, M. Xu, and C. Pei. Mechanical and rheological properties of High-Performance concrete (HPC) incorporating waste glass as cementitious material and fine aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 387, No. Dec 2022, 2023, id. 131656.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131656Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Li, Y., J. Chai, R. Wang, Y. Zhou, and X. Tong. A review of the durability-related features of waste tyre rubber as a partial substitute for natural aggregate in concrete. Buildings, Vol. 12, 2022, id. 1975.10.3390/buildings12111975Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Shen, D., Y. Jiao, Y. Gao, S. Zhu, and G. Jiang. Influence of ground granulated blast furnace slag on cracking potential of high performance concrete at early age. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 241, 2020, id. 117839.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117839Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Hashem, F. S., T. A. Razek, and H. A. Mashout. Rubber and plastic wastes as alternative refused fuel in cement industry. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 212, 2019, pp. 275–282.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.316Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Reza, A., A. Tavana, and S. Dessouky. A novel hybrid adaptive boosting approach for evaluating properties of sustainable materials: A case of concrete containing waste foundry sand. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 72, 2023, id. 106595.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106595Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Tosti, L., A. Van Zomeren, J. R. Pels, and R. N. J. Comans. Resources, conservation & recycling technical and environmental performance of lower carbon footprint cement mortars containing biomass fl y ash as a secondary cementitious material. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 134, 2018, pp. 25–33.10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.03.004Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Rafieizonooz, M., J. Mirza, M. Razman, M. Warid, and E. Khankhaje. Investigation of coal bottom ash and fly ash in concrete as replacement for sand and cement. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 116, 2016, pp. 15–24.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.04.080Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Gu, K. and B. Chen. Research on the incorporation of untreated fl ue gas desulfurization gypsum into magnesium oxysulfate cement. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 271, 2020, id. 122497.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122497Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Dodoo-arhin, D., R. A. Nuamah, B. Agyei-tu, D. O. Obada, and A. Yaya. Awaso bauxite red mud-cement based composites: Characterisation for pavement applications. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 7, 2017, pp. 45–55.10.1016/j.cscm.2017.05.003Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Mehta, A. and D. K. Ashish. Silica fume and waste glass in cement concrete production: A review. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 29, No. July 2019, 2020, id. 100888.10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100888Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Jahami, A. and C. A. Issa. Exploring the use of mixed waste materials ( MWM) in concrete for sustainable Construction: A review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 398, 2023, id. 132476.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132476Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Sathiparan, N. Utilization prospects of eggshell powder in sustainable construction material – A review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 293, 2021, id. 123465.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123465Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Zaid, O., S. R. Zamir Hashmi, M. H. El Ouni, R. Martínez-García, J. de Prado-Gil, and S. Yousef. Experimental and analytical study of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete modified with egg shell powder and nano-silica. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 24, 2023, pp. 7162–7188.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.04.240Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Amin, M. N., W. Ahmad, K. Khan, A. Ahmad, S. Nazar, and A. A. Alabdullah. Use of artificial intelligence for predicting parameters of sustainable concrete and raw ingredient effects and interactions. Materials, Vol. 15, No. 15, 2022, id. 5207.10.3390/ma15155207Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Tchinda, D. E., H. K. Tchakouté, C. H. Rüscher, E. Kamseu, A. Elimbi, and C. Leonelli. Design of low cost semi-crystalline calcium silicate from biomass for the improvement of the mechanical and microstructural properties of metakaolin-based geopolymer cements. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 223, No. Oct 2018, 2019, pp. 98–108.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.10.061Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Ahmed, A., W. Inn, N. Mohamad, and S. Sohu. Utilization of palm oil fuel ash and eggshell powder as partial cement replacement - a review. Civil Engineering Journal, Vol. 4, No. 8, 2018, pp. 1977–1984.10.28991/cej-03091131Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Nasir, M., W. Ahmad, K. Khan, M. N. Al-hashem, A. Farouk, and A. Ahmad. Case Studies in Construction Materials Testing and modeling methods to experiment the flexural performance of cement mortar modified with eggshell powder. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 18, No. Oct 2022, 2023, id. e01759.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Hakeem, I. Y., M. Amin, I. S. Agwa, M. H. Abd-Elrahman, O. Ibrahim, and M. Samy. Ultra-high-performance concrete properties containing rice straw ash and nano eggshell powder. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 19, 2023, id. e02291.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02291Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Canbaz, M. Properties of concrete containing waste glass. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 34, 2004, pp. 267–274.10.1016/j.cemconres.2003.07.003Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Shao, Y., T. Lefort, S. Moras, and D. Rodriguez. Studies on concrete containing ground waste glass. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 30, 2000, pp. 91–100.10.1016/S0008-8846(99)00213-6Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Mirzahosseini, M. and K. A. Riding. Effect of curing temperature and glass type on the pozzolanic reactivity of glass powder. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 58, 2014, pp. 103–111.10.1016/j.cemconres.2014.01.015Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Sun, J., Y. Ma, J. Li, J. Zhang, Z. Ren, and X. Wang. Machine learning-aided design and prediction of cementitious composites containing graphite and slag powder. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 43, 2021, id. 102544.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102544Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Qayyum, A., H. Ahmad, M. Rasul, and Z. Ahmad. Optimized artificial neural network model for accurate prediction of compressive strength of normal and high strength concrete. Cleaner Materials, Vol. 10, 2023, id. 100211.10.1016/j.clema.2023.100211Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Ofuyatan, O. M., O. B. Agbawhe, D. O. Omole, C. A. Igwegbe, and J. O. Ighalo. RSM and ANN modelling of the mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with silica fume and plastic waste as partial constituent replacement. Cleaner Materials, Vol. 4, Dec 2021, id. 100065.10.1016/j.clema.2022.100065Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Ferdosian, I. and A. Cam. Eco-ef fi cient ultra-high performance concrete development by means of response surface methodology ∼ es. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 84, 2017, pp. 146–156.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Ali, M., A. Kumar, A. Yvaz, and B. Salah. Central composite design application in the optimization of the effect of pumice stone on lightweight concrete properties using RSM. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 18, 2023, id. e01958.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e01958Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Mehrinejad, M., B. Mehdizadeh, F. Naseri, T. Ozbakkaloglu, F. Jafari, and E. Mohseni. Effect of SnO 2, ZrO 2, and CaCO 3 nanoparticles on water transport and durability properties of self-compacting mortar containing fly ash: Experimental observations and ANFIS predictions. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 158, 2018, pp. 823–834.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.10.067Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Yaman, M. A., M. A. Elaty, and M. Taman. Predicting the ingredients of self compacting concrete using artificial neural network. Alexandria Engineering Journal, Vol. 56, No. 4, 2017, pp. 523–532.10.1016/j.aej.2017.04.007Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Yan, F., Z. Lin, X. Wang, F. Azarmi, and K. Sobolev. Evaluation and prediction of bond strength of GFRP-bar reinforced concrete using artificial neural network optimized with genetic algorithm. Composite Structures, Vol. 161, 2017, pp. 441–452.10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.11.068Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Romagnoli, M., C. Leonelli, E. Kamse, and M. L. Gualtieri. Rheology of geopolymer by DOE approach. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 36, 2012, pp. 251–258.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.122Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Khayat, K. H., J. Assaad, and J. Daczko. Comparison of field-oriented test methods to assess dynamic stability of self- comparison of field-oriented test methods to assess dynamic stability of self-consolidating concrete. ACI Materials Journal, Vol. 101, No. 2, 2004, pp. 168–176.10.14359/13066Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Gencel, O. Fracture energy-based optimisation of steel fibre reinforced concretes. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 107, 2013, pp. 29–37.10.1016/j.engfracmech.2013.04.018Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Bayramov, F., C. Tas, and M. A. Tas. Optimisation of steel fibre reinforced concretes by means of statistical response surface method. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 26, 2004, pp. 665–675.10.1016/S0958-9465(03)00161-6Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Montgomery, S. H. Divergence in brain composition during the early stages of ecological specialisation in Heliconius butterflies. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2017, pp. 1–26.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Habibi, A., A. Mohammad, and M. Mahdikhani. RSM-based optimized mix design of recycled aggregate concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials based on waste generation and global warming potential. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 167, 2021, id. 105420.10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105420Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Khandelwal, M. and T. N. Singh. Prediction of macerals contents of Indian coals from proximate and ultimate analyses using artificial neural networks. Fuel, Vol. 89, No. 5, 2010, pp. 1101–1109.10.1016/j.fuel.2009.11.028Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Adhikary, B. B. and H. Mutsuyoshi. Prediction of shear strength of steel fiber RC beams using neural networks. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 20, 2006, pp. 801–811.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2005.01.047Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Khan, M. I. Predicting properties of High Performance Concrete containing composite cementitious materials using Artificial Neural Networks. Automation in Construction, Vol. 22, 2012, pp. 516–524.10.1016/j.autcon.2011.11.011Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Bhatti, M. A. Predicting the compressive strength and slump of high strength concrete using neural network. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 20, 2006, pp. 769–775.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2005.01.054Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Lee, S. and C. Lee. Prediction of shear strength of FRP-reinforced concrete flexural members without stirrups using artificial neural networks. Engineering Structures, Vol. 61, 2014, pp. 99–112.10.1016/j.engstruct.2014.01.001Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Uysal, M. and H. Tanyildizi. Estimation of compressive strength of self compacting concrete containing polypropylene fiber and mineral additives exposed to high temperature using artificial neural network. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2012, pp. 404–414.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.07.028Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Alshihri, M. M., A. M. Azmy, and M. S. El-bisy. Neural networks for predicting compressive strength of structural light weight concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 23, No. 6, 2009, pp. 2214–2219.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.12.003Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Hodhod, O. A. and G. Salama. Developing an ANN model to simulate ASTM C1012-95 test considering different cement types and different pozzolanic additives. HBRC Journal, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2013, pp. 1–14.10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.02.003Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Mukherjee, A. and S. N. Biswas. Artificial neural networks in prediction of mechanical behavior of concrete at high temperature. Nuclear Engineering and Design, Vol. 178, 1997, pp. 1–11.10.1016/S0029-5493(97)00152-0Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Onal, O. and A. U. Ozturk. Advances in engineering software artificial neural network application on microstructure – compressive strength relationship of cement mortar. Advances in Engineering Software, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2010, pp. 165–169.10.1016/j.advengsoft.2009.09.004Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Sarıdemir, M. Predicting the compressive strength of mortars containing metakaolin by artificial neural networks and fuzzy logic. Advances in Engineering Software, Vol. 40, No. 9, 2009, pp. 920–927.10.1016/j.advengsoft.2008.12.008Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Duan, Z. H., S. C. Kou, and C. S. Poon. Using artificial neural networks for predicting the elastic modulus of recycled aggregate concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 44, 2013, pp. 524–532.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.02.064Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Kellouche, Y., B. Boukhatem, and M. G. A. Tagnit-hamou. Exploring the major factors affecting fly-ash concrete carbonation using artificial neural network. Neural Computing and Applications, Vol. 31, No. s2, 2019, pp. 969–988.10.1007/s00521-017-3052-2Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Cook, R., J. Lapeyre, and A. Kumar. Prediction of compressive strength of concrete: critical comparison of performance of a hybrid machine learning model with standalone models. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 11, 2020, pp. 1–15.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002902Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Skentou, A. D., A. Bardhan, A. Mamou, M. E. Lemonis, G. Kumar, and Samui. Closed ‑ form equation for estimating unconfined compressive strength of granite from three non – destructive tests using soft computing models. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, Vol. 56, No. 1, 2023, pp. 487–514.10.1007/s00603-022-03046-9Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Mohammadi, E., A. Behnood, and M. Arashpour. Predicting the compressive strength of normal and High-Performance Concretes using ANN and ANFIS hybridized with Grey Wolf Optimizer. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 232, 2020, id. 117266.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117266Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Duan, Z. H., S. C. Kou, and C. S. Poon. Prediction of compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete using artificial neural networks. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 40, 2013, pp. 1200–1206.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.063Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Asteris, P. G., M. Karoglou, A. D. Skentou, G. Vasconcelos, M. He, A. Bakolas, et al. Predicting uniaxial compressive strength of rocks using ANN models: Incorporating porosity, compressional wave velocity, and schmidt hammer data Symmetric Saturating Linear transfer function. Ultrasonics, Vol. 141, 2024, id. 107347.10.1016/j.ultras.2024.107347Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Ali, R., M. Muayad, and G. Asteris. Analysis and prediction of the effect of Nanosilica on the compressive strength of concrete with different mix proportions and specimen sizes using various numerical approaches. Structural Concrete, Vol. 24, 2022, pp. 1–24.10.1002/suco.202200718Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Cavaleri, L., M. Sadegh, C. C. Repapis, D. Jahed, D. Vladimirovich, and G. Asteris. Convolution-based ensemble learning algorithms to estimate the bond strength of the corroded reinforced concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 359, 2022, id. 129504.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129504Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Benzaamia, A., M. Ghrici, R. Rebouh, N. Zygouris, and G. Asteris. Predicting the shear strength of rectangular RC beams strengthened with externally-bonded FRP composites using constrained monotonic neural networks. Engineering structures, Vol. 313, 2024, id. 118192.10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118192Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Pal, A., K. Sakil, F. M. Zahid, and M. S. Alam. Machine learning models for predicting compressive strength of fiber-reinforced concrete containing waste rubber and recycled aggregate. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 423, 2023, id. 138673.10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138673Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Meesaraganda, L. P., P. Saha, and N. Tarafder. Artificial neural network for strength prediction of fibers self-compacting concrete. In: Soft Computing for Problem Solving: SocProS 2017, Springer, Singapore, 2019, pp. 15–24.10.1007/978-981-13-1592-3_2Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Asteris, G. and K. G. Kolovos. Self-compacting concrete strength prediction using surrogate models. Neural Computing and Applications, Vol. 31, 2019, pp. 409–424.10.1007/s00521-017-3007-7Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Asadi, E., N. Roshan, S. A. Hadigheh, M. L. Nehdi, A. Khodabakhshian, and M. Ghalehnovi. Machine learning-based compressive strength modelling of concrete incorporating waste marble powder. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 324, 2022, id. 126592.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126592Suche in Google Scholar

[69] Amin, M. N., H. A. Alkadhim, W. Ahmad, K. Khan, H. Alabduljabbar, and A. Mohamed. Experimental and machine learning approaches to investigate the effect of waste glass powder on the flexural strength of cement mortar. PLoS One, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2023, id. e0280761.10.1371/journal.pone.0280761Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[70] Amin, M. N., W. Ahmad, K. Khan, M. N. Al-Hashem, A. F. Deifalla, and A. Ahmad. Testing and modeling methods to experiment the flexural performance of cement mortar modified with eggshell powder. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 18, 2023, id. e01759.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01759Suche in Google Scholar

[71] Study, L. M. Strength reduction due to acid attack in cement mortar containing waste eggshell and glass: a machine. Buildings, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2024, id. 225.10.3390/buildings14010225Suche in Google Scholar

[72] Khan, K., W. Ahmad, M. N. Amin, and A. F. Deifalla. Investigating the feasibility of using waste eggshells in cement-based materials for sustainable construction. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 23, 2023, pp. 4059–4074.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.02.057Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Schober, P., C. Boer, and L. A. Schwarte. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia & analgesia, Vol. 126, 2018, pp. 1–6.10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[74] Essam, A., S. A. Mostafa, M. Khan, and A. M. Tahwia. Modified particle packing approach for optimizing waste marble powder as a cement substitute in high-performance concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 409, 2023, id. 133845.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133845Suche in Google Scholar

[75] Chen, L., P. Fakharian, D. Rezazadeh, and M. Haji. Axial compressive strength predictive models for recycled aggregate concrete filled circular steel tube columns using ANN. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 77, 2023, id. 107439.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107439Suche in Google Scholar

[76] Ray, S., M. Haque, T. Ahmed, and T. T. Nahin. Comparison of artificial neural network ( ANN) and response surface methodology ( RSM) in predicting the compressive and splitting tensile strength of concrete prepared with glass waste and tin ( Sn) can fiber. Journal of king saud university-engineering sciences, Vol. 35, No. 3, 2023, pp. 185–199.10.1016/j.jksues.2021.03.006Suche in Google Scholar

[77] Rahman, S. K. and R. Al-ameri. Structural assessment of Basalt FRP reinforced self-compacting geopolymer concrete using artificial neural network ( ANN) modelling. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 397, 2023, id. 132464.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132464Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Paruthi, S., A. H. Khan, A. Kumar, F. Kumar, M. A. Hasan, H. M. Magbool, et al. Sustainable cement replacement using waste eggshells: A review on mechanical properties of eggshell concrete and strength prediction using artificial neural network. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 18, 2023, id. e02160.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02160Suche in Google Scholar

[79] Reddy, Y. S., A. Sekar, and S. S. Nachiar. A validation study on mechanical properties of foam concrete with coarse aggregate using ANN model. Buildings, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2023, id. 218.10.3390/buildings13010218Suche in Google Scholar

[80] Martínez-garcía, R., Jagadesh, and G. María-inmaculada. To determine the compressive strength of self-compacting recycled aggregate concrete using artificial neural network (ANN). Ain Shams Engineering Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2023, id. 102548.10.1016/j.asej.2023.102548Suche in Google Scholar

[81] Approach, A. N. N., H. Song, A. Ahmad, and K. A. Ostrowski. Analyzing the compressive strength of ceramic waste-based concrete using experiment and artificial neural network. Materials, Vol. 14, No. 16, 2021, id. 4518.10.3390/ma14164518Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[82] Van Dao, D., H. Ly, H. T. Vu, and T. Le. Investigation and optimization of the C-ANN structure in predicting the compressive strength of foamed concrete. Materials, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2020, pp. 1–17.10.3390/ma13051072Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[83] Gallo, C. Artificial neural networks tutorial. In: Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, Third Edition, IGI Global, pp. 6369–6378.10.4018/978-1-4666-5888-2.ch626Suche in Google Scholar

[84] Alsharari, F., K. Khan, M. N. Amin, W. Ahmad, U. Khan, M. Mutnbak, et al. Case studies in construction materials sustainable use of waste eggshells in cementitious materials: an experimental and modeling-based study. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 17, 2022, id. e01620.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01620Suche in Google Scholar

[85] Schilling, A., A. Maier, R. Gerum, and C. Metzner. Quantifying the separability of data classes in neural networks. Neural Networks, Vol. 139, 2021, pp. 278–293.10.1016/j.neunet.2021.03.035Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Güçlüer, K., A. Ozbeyaz, and G. Samet. A comparative investigation using machine learning methods for concrete compressive strength estimation. Materials Today Communications, Vol. 27, 2021, id. 102278.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102278Suche in Google Scholar

[87] Singh, T. N., R. Kanchan, A. K. Verma, and K. Saigal. A comparative study of ANN and Neuro-fuzzy for the prediction of dynamic constant of rockmass. Journal of Earth System Science, Vol. 1, 2005, pp. 75–86.10.1007/BF02702010Suche in Google Scholar

[88] Lippmann, R. P. An introduction to computing with neural nets. IEEE ASSP Ma gazine, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1987, pp. 4–22.10.1109/MASSP.1987.1165576Suche in Google Scholar

[89] Kewalramani, M. A. and R. Gupta. Concrete compressive strength prediction using ultrasonic pulse velocity through artificial neural networks. Automation in Construction, Vol. 15, 2006, pp. 374–379.10.1016/j.autcon.2005.07.003Suche in Google Scholar

[90] Jagadesh, P., A. H. Khan, B. S. Priya, A. Asheeka, Z. Zoubir, and H. M. Magbool. Artificial neural network, machine learning modelling of compressive strength of recycled coarse aggregate based self-compacting concrete. PloS one, Vol. 19, 2024, id. 0303101.10.1371/journal.pone.0303101Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[91] Habibi, A., A. Mohammad, M. Mahdikhani, and O. Bamshad. RSM-based evaluation of mechanical and durability properties of recycled aggregate concrete containing GGBFS and silica fume. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 270, 2021, id. 121431.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121431Suche in Google Scholar

[92] Adamu, M., M. Louay, Y. E. Ibrahim, O. Shabbir, H. Alanazi, and A. Louay. Modeling and optimization of the mechanical properties of date fiber reinforced concrete containing silica fume using response surface methodology. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 17, 2022, id. e01633.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01633Suche in Google Scholar

[93] Ghafari, E., H. Costa, and E. Júlio. RSM-based model to predict the performance of self-compacting UHPC reinforced with hybrid steel micro-fibers. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 66, 2014, pp. 375–383.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.05.064Suche in Google Scholar

[94] Ferdosian, I. and A. Cam. Eco-ef fi cient ultra-high performance concrete development by means of response surface methodology ∼ es. Cement and Concrete Composites Journal, Vol. 84, 2017, pp. 146–156.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.08.019Suche in Google Scholar

[95] Apostolopoulou, M., D. J. Armaghani, A. Bakolas, M. G. Douvika, A. Moropoulou, and G. Asteris. Compressive strength strength of of natural natural hydraulic hydraulic lime lime mortars mortars using using soft soft computing techniques computing techniques. Procedia Structural Integrity, Vol. 17, 2019, pp. 914–923.10.1016/j.prostr.2019.08.122Suche in Google Scholar

[96] Kumar, S., H. Meena, S. Chakraborty, and B. C. Meikap. Application of response surface methodology ( RSM) for optimization of leaching parameters for ash reduction from low-grade coal. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2018, pp. 621–629.10.1016/j.ijmst.2018.04.014Suche in Google Scholar

[97] Prado-gil, D., N. Silva-monteiro, and R. Martı. Assessing the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete with recycled aggregates from mix ratio using machine learning approach. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 24, 2023, pp. 1483–1498.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.03.037Suche in Google Scholar

[98] Dahmoune, F., H. Remini, S. Dairi, O. Aoun, K. Moussi, N. Bouaoudia-Madi, et al. Ultrasound assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from lentiscus L. leaves: Comparative study of artificial neural network (ANN) versus degree of experiment for prediction ability of phenolic compounds recovery. Industrial Crops and Products, Vol. 77, 2015, pp. 251–261.10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.08.062Suche in Google Scholar

[99] Bilim, C., C. D. Atis, H. Tanyildizi, and O. Karahan. Predicting the compressive strength of ground granulated blast furnace slag concrete using artificial neural network. Advances in Engineering Software, Vol. 40, 2009, pp. 334–340.10.1016/j.advengsoft.2008.05.005Suche in Google Scholar

[100] Hong-guang, N. and W. Ji-zong. Prediction of compressive strength of concrete by neural networks. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 30, 2000, pp. 1245–1250.10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00345-8Suche in Google Scholar

[101] Feng, D. C., Z. T. Liu, X. D. Wang, Y. Chen, J. Q. Chang, D. F. Wei, et al. Machine learning-based compressive strength prediction for concrete: An adaptive boosting approach. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 230, 2020, id. 117000.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117000Suche in Google Scholar

[102] Hoang, N., A. Pham, Q. Nguyen, and Q. Pham. Estimating Compressive Strength of High Performance Concrete with Gaussian Process Regression Model. Hindawi Publication CorAdvance, Vol. 2016, 2016, pp. 1–8.10.1155/2016/2861380Suche in Google Scholar

[103] Biswas, R., M. Kumar, R. Kumar, M. Alzara, S. Eldeen, and A. S. Yousef. A novel integrated approach of RUNge Kutta optimizer and ANN for estimating compressive strength of self-compacting concrete. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 18, 2023, id. e02163.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02163Suche in Google Scholar

[104] Amiri, M. and F. Hatami. Prediction of mechanical and durability characteristics of concrete including slag and recycled aggregate concrete with artificial neural networks (ANNs). Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 325, 2022, id. 126839.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126839Suche in Google Scholar

[105] Meenakshi, B. S., P. Indradevi, A. Dhilp, T. H. Natarajan, S. Sathyasheelan, and V. Kathirvel. Materials Today: Proceedings ANN model using MATLAB in CFS -concrete. Material Today, 2024.10.1016/j.matpr.2023.05.103Suche in Google Scholar

[106] Bonagura, M. and L. Nobile. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) approach for predicting concrete compressive strength by SonReb. Structural Durability Health Monitoring, Vol. 15, 2021, pp. 125–137.10.32604/sdhm.2021.015644Suche in Google Scholar

[107] Li, Q., L. Cai, Y. Fu, H. Wang, and Y. Zou. Fracture properties and response surface methodology model of alkali-slag concrete under freeze – thaw cycles. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 93, 2015, pp. 620–626.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.06.037Suche in Google Scholar

[108] Esat, K., E. Ghafari, and R. Ince. Development of eco-ef fi cient self-compacting concrete with waste marble powder using the response surface method. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 144, 2017, pp. 192–202.10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.156Suche in Google Scholar

[109] Ngayakamo, B. and A. Onwualu. Heliyon recent advances in green processing technologies for valorisation of eggshell waste for sustainable construction materials. Heliyon, Vol. 8, No. Sept 2021, 2022, id. e09649.10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09649Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[110] Wang, N., Z. Xia, M. N. Amin, W. Ahmad, K. Khan, F. Althoey, et al. Sustainable strategy of eggshell waste usage in cementitious composites: An integral testing and computational study for compressive behavior in aggressive environment. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 386, 2023, id. 131536.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131536Suche in Google Scholar

[111] Chong, B. W., R. Othman, P. J. Ramadhansyah S. I. Doh, and X. Li. Properties of concrete with eggshell powder: A review. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, Vol. 120, 2020, id. 102951.10.1016/j.pce.2020.102951Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review