Abstract

This study focuses on the comprehensive exploration of Swat soapstone, employing a range of analytical techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy. XRD was used to identify the phase and lattice parameters of the soapstone. SEM further scrutinizes the dispersed soapstone particles, revealing different structural characteristics such as a slightly elongated, cubic-like structure, a straight rod-like formation, and a rough, textured surface. EDX spectroscopy was utilized for studying the elemental composition of the soapstone. The analysis identifies talc as the primary mineral in Swat soapstone, with iron, an element, also contributing notably to its composition. This underscores the complexity of Swat soapstone’s internal structure. XRF analysis further contributes to the elemental characterization, revealing a dominant composition of silicon (Si) at 48.567 wt% and a notable contribution from iron (Fe) at 16.108 wt%. FTIR analysis confirmed the absorption of infrared radiation at the non-bridging oxygen (Si–O–) within the silicate network and the Si–O–Si bending vibration. This work investigates the chemical and morphological details of the Swat soapstone.

1 Introduction

Soapstone is the common name for the mineral steatite or soaprock. It is a relatively soft, magnesium-rich metamorphic rock largely composed of talc [1]. It is widely utilized for architectural features, countertops, carvings, and sculptures [2]. This is a metamorphic, impure rock where calcite, dolomite, and serpentine are closely blended with talc, a hydrous silicate of magnesium. It is usually variegated and has a gray, bluish, green, or brown tint. Its “soapy” feel and softness are the source of its name. It also contains various amounts of other minerals, such as micas, chlorite, amphiboles, quartz, magnesite, and carbonates, depending on the quarry from which it is sourced [3].

Talc is composed of 31.7% MgO, 63.5% SiO2, and 4.8% H2O, forming Mg3(Si4O10) (OH)2. In terms of trade and industry, talc is the most significant mineral found in soapstone. In the ceramics sector, talc finds application in a wide range of ceramic materials, including but not limited to tiles, technical ceramics, industrial ceramics, dinnerware, bathroom fixtures, inserts, and thermal and electric insulation. Bricks, blocks, tiles, pipes, roof slabs, ornamental vases, light-expanded clay aggregates, and other items are the primary outputs of the structural ceramics class. Common clay is used in the structural ceramics industry. In order to create this substance, “heavy” clay – which is generally made up of clay minerals with high plasticity, tiny particle size, and composition – is typically combined with “light” clay – which is less plastic and contains a lot of quartz, which is categorized as a plasticity-reducing ingredient – to create this mixture [4].

There are three main kinds of talc in its natural state, depending on the location: granular, acicular, and lamellar. The lamellar form is the most suitable for commercial standards. Soapstone comes in a variety of textures, including powder, huge, and compact rock. Talc is an industrial filler material that needs to have specific qualities and attributes depending on the use. These qualities and attributes include size distribution, morphology, mineralogy, purity, and other aspects. Talc is used in the textile and cosmetics industries, for example, because of its high melting point, chemical inertia, low electrical conductivity, low hygroscopy, and ability to absorb oils. Talc is used in the rubber industry’s vulcanization process and the creation of wiring insulating ducts. When its pure form (above 90%) is employed in the pharmaceutic business and, in the event of variable purity, it works as feedstock for electric ceramics. Other uses for talc include the construction, agricultural, and ceramic industries, where it is used as a magnesium source to manage thermal expansion.

The composition of soapstone varies by location, but in order for a rock to be called soapstone, it must have fewer than 35% hard silicates (such as olivine, pyroxene, serpentine, and amphibole) and between 35 and 75% talc mineral [5]. While soapstone has many qualities, such as being soft and easy to carve, having a high specific heat capacity, being insoluble in water, and low electrical conductivity, its three main advantages are its resistance to heat, acids, and absorption (non-porosity). Soapstone’s advantageous qualities contributed to its historical prominence. Because of its low hardness (Mohs scale 1–3, depending on the talc content of the rock), soapstone is quite workable, even when using tools for woodcarving. The English term “soapstone” refers to the stone’s “soapy” surface because of its high talc concentration. It was most likely also adopted because the stone is relatively simple to cut and carve [6].

The porosity of soapstone is incredibly low, usually less than 1%, frequently less than 0.5%, or even less [7]. Because of its mineralogical composition, it also exhibits a high density of approx. 2,800–2,900 kg·m−3 [8]. Favorable heat capacity, within the range of 0.9–1.1 kJ·kg−1·K−1, is crucial for refractory materials. Because soapstone has a high heat capacity, it is also used as a material for stoves and fireplaces where thermal conductivity between 2 and 5.5 W·K−1·m−1 is preferred. This allows for rapid and even heating of the structure [9]. The properties of soapstone enable it to be used in ceramics, paper, paints, cosmetics, plastic, insecticides, etc.

Physically, soapstone is resistant to both acidic and basic chemicals. It also has exceptional temperature tolerance, withstanding variations in temperature from well below zero to well over 1,000°C without experiencing significant deterioration. Soapstone is frequently used as a dimension stone and building stone. Because it is easily carved into gigantic forms, cooking pots, vessels, small tools, and food containers, the talc-rich, non-porous, soft rock is highly prized; in addition, soapstone is softer than marble and granite, it makes an ideal medium for carving soft stone objects, sculptures, decorative architecture, single-wick lamps, fireplaces, and stoves [10].

Soapstone is made of talc with varying amounts of chlorite and amphiboles (usually tremolite, anthophyllite, and cummingtonite) and traces of tiny iron-chromium oxide. It could be enormous or schistose. Metasomatism of siliceous dolomites and metamorphism of ultramafic protoliths (such as dunite or serpentinite) combine to generate soapstone. Roughly 63.37% silica, 31.88% magnesia, and 4.74% water make up “pure” steatite by mass. It frequently has trace amounts of other oxides, like CaO or Al2O3 [11]. Soapstone deposits occur in the Parachinar area; in Kuram Agency the estimated amount of soapstone is 3.2 million tons; Jamrud, Khyber Agency; Swat District; Sherwan (20,000 tons), Abbottabad District. Soapstone is found everywhere in the world. Soapstone nowadays is primarily imported from China, India, and Brazil. Significant deposits can also be found in the United States, Austria, France, Italy, Switzerland, Australia, and Canada. Objects carved from soapstone have a very long lifespan because soapstone is a geologically stable, solid stone, which is not influenced by dampness, but stones from different places have varying qualities [12].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in studying the phase, microstructure, and mineralogical characterization of soapstone to better understand its properties and potential applications. Olsen et al. [9] found that the soapstone samples contained mainly talc and chlorite minerals, with small amounts of other minerals such as magnesite and dolomite. The microstructure of the samples showed a compact and homogeneous texture with a fine-grained structure, which is favorable for industrial applications. Winkler [12] found that the soapstone samples had a high degree of purity, with a talc content of over 95%. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy showed the presence of various functional groups such as Si–O, Mg–O, and OH, which are characteristic of soapstone. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis revealed a crystalline structure with a high degree of ordering in the talc layers [13]. Malkani et al. [14] found that the soapstone-derived MgO nanoparticles had a high degree of purity and small particle size, which is desirable for various industrial applications such as catalysis and biomedical applications. Finally, Malkani et al. [15] studied the effect of sintering temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Swat soapstone-based ceramics and found that increasing the sintering temperature resulted in a denser microstructure and improved mechanical properties of the ceramics. Swat soapstone can be used as a raw material for the production of high-quality ceramics with excellent mechanical and thermal properties [16]. Karampelas et al. [16] also found that increasing the sintering temperature resulted in a denser microstructure and improved mechanical and thermal properties of the ceramics.

Swat soapstone is generally a versatile material with potential applications in various fields, such as ceramics, catalysis, refractory materials, and carved objects. The studies reviewed here provide a solid foundation for further research into the properties and potential applications of this remarkable rock. The findings of these studies demonstrate that Swat soapstone has a bright future in the world of industrial materials and design.

2 Materials and methods

The representative sample was collected from active mines of the swat region, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The sample was washed, dried, and ground at the Materials Research Laboratory (MRL), University of Peshawar. Following US standards, the powdered sample was sieved through 100 (149 mm) and 200 mesh (74 mm) sizes at MRL. Phase analysis was performed using a JEOL 3532 X-ray diffractometer with Cu Ka (l–1.54 Å) radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA in the Centralized Resource Laboratory, University of Peshawar. For microstructural analysis, a ∼4 × 4 × 4 mm³ piece was cut from a soapstone sample using a TeckCut 4TM precision low-speed diamond saw. The sample was meticulously polished using a TwinPrep 3TM grinding/polishing machine, employing various grades of sandpaper (silicon carbide) and diamond paste on imperial adhesive back polishing cloth with water as a lubricant at MRL. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)analysis involved mounting the polished sample onto an aluminum stub with silver paint, followed by gold coating to prevent charging. The JEOL JSM 5910 SEM was utilized to examine the surface morphology, approximate grain sizes, and micro-regions. Elemental analysis was conducted using energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy coupled with SEM. We utilized a spectrum-two FTIR instrument (PerkinElmer) to analyze the specific functional groups present in soapstone. This involved employing universal ATR pellet techniques within the wavenumber range of 500–4,000 cm−1. The FTIR spectrometer (model Cary 630, Agilent Technologies, USA) was used in this study. For analytical purposes, the machine requires that samples be presented either in a solid state (powder/bulk) or as a liquid.

To conduct chemical analysis, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry was carried out using a Shimadzu EDX-7000 unit (Japan), with a detection limit spanning from Al to U. The XRF spectrometer used in the study was a Shimadzu EDX-7000, with the capability to analyze elements from aluminum (Al) to uranium (U). It offers analysis modes for elemental percentage, elemental parts per million (ppm), and oxide percentage. The machine accommodates various sample types, including powders, solid materials, and liquids, requiring solid samples to be either more than 1 cm in diameter or 1 cm² and less than 0.5 cm in thickness.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XRD study of soapstone

Figure 1 shows the X-ray diffractogram of the interplanar d-spacing and relative intensity of the soapstone sample. The major phase identified in the sample was Enstatite (aluminum calcium iron magnesium silicate) marked as D, along with the minor phase of Datolite, marked as C. The minor phase present in the sample was Laumontite marked as A. The major phase (D) peak matched with PDF card # 96-900-6443 for Enstatite (Al0.14Ca0.012Fe0.24Mg1.66O6Si1.94), and the minor phase (A) peak matched with PDF card # 96-900-7283 for Laumontite (Al2CaH12O16.5Si4). The third peak (C) matched with the PDF card # 96-901-4572 for Datolite (BCaHO5Si). The peak labeled (B) did not match any PDF card, which is an unidentified peak. XRD studies of soapstone performed by Mota et al. [17] showed that the corresponding spectra is a characteristic of Monoclinic Talc.

X-ray diffractogram of soapstone sample obtained from Swat – major phase enstatite (D) with minor phases datolite (C) and laumontite (A), along with an unidentified peak (B).

Table 1 displays the average crystallite size (D in nm) determined using the Scherrer formula (Eq. (1)) [18]. The calculated values indicate an average crystallite size of 55.06 nm for the synthesized nanoparticles. Pulivarti and Birru [18] also investigated the crystallite size and found that the broadening in XRD peaks is caused by the small values of crystallite size. The small values of the crystallite size in Table 1 showed the agglomerated behavior of the samples [18].

where D is the crystallite size (nm), K is the Scherrer constant (=0.9), λ is the wavelength of the X-ray source (=0.15406 nm), β represents FWHM (rad), and θ is the peak position (rad).

Average crystalline size of the XRD peak in the soapstone

| Peak position (2θ) | FWHM | Crystallite size D (nm) | D (nm) (average) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.6 | 0.141 | 56.54 | 55.06 |

| 19.1 | 0.112 | 71.97 | |

| 25.9 | 0.171 | 47.68 | |

| 28.7 | 0.156 | 52.38 | |

| 31 | 0.276 | 29.80 | |

| 48.7 | 0.121 | 71.95 |

Table 2 presents interplanar spacing values derived from XRD data using Eq. (2) [19]. These values offer crucial insights into the crystallographic structure of the soapstone material:

where λ (= 1.5406 Å) is the wavelength of the incident X-ray, θ is the peak position (in rad), n = 1 is the order of diffraction, and d is the interplanar spacing (in Å).

Detailed interplanar spacing values from XRD analysis

| Peak position (2θ) | Theta (θ) | d-spacing |

|---|---|---|

| 9.56 | 4.78 | 9.24 |

| 19.10 | 9.55 | 4.64 |

| 25.90 | 12.95 | 3.44 |

| 28.74 | 14.37 | 3.10 |

| 31.03 | 15.51 | 2.88 |

| 48.75 | 24.37 | 1.86 |

3.2 Functional group analysis (FTIR)

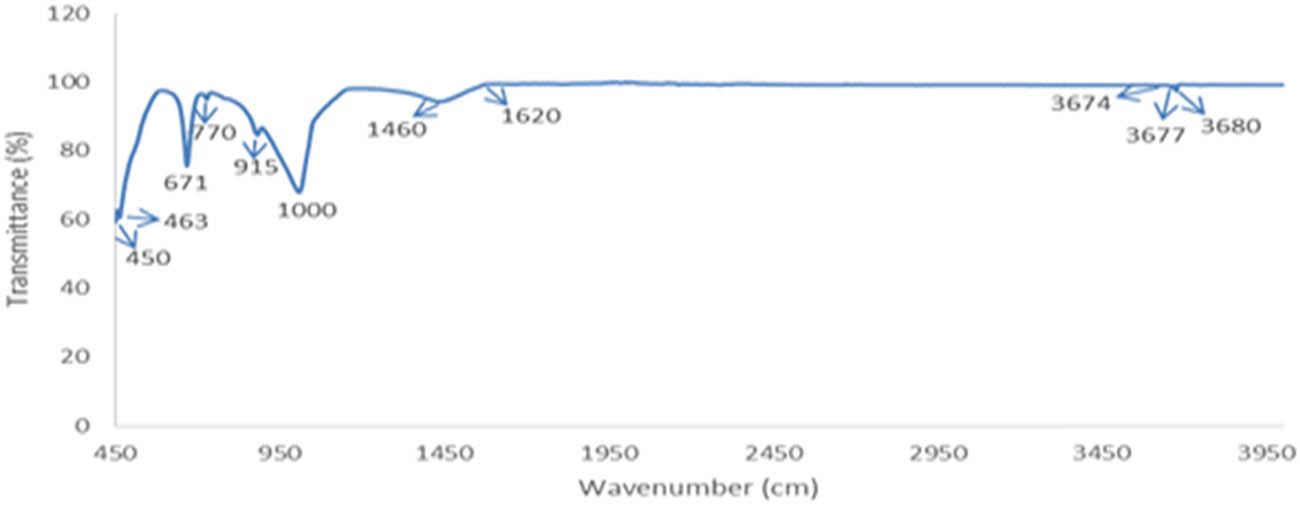

Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectrum of the soapstone sample. Notably, within this spectrum, the peak at 3,680 cm−1, corresponding to the O–H symmetric stretching band is a common feature of talc [20]. This particular band exhibits a secondary weaker peak at 3,677 cm−1, which may arise due to the presence of impurities such as iron (Fe) or an alteration in the orientation of the molecules. Moreover, the characteristic peaks at 3,674, 3,677, and 3,680 cm−1 belong to O–H stretching vibrations, indicating the presence of hydroxyl groups within the sample [21,22].

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic graph of the soapstone obtained from the swat region representing different peak.

The bending vibrations of metal-oxygen bonds are observed in the region 450–1,000 cm−1, which corresponds to silicate minerals [23]. A distinctive feature of the spectrum is the pronounced peak at 463 cm−1, indicative of a strong absorption and lower transmittance. The band spanning the range of 450–463 cm−1 is assigned to the Si–O–Si bending vibration. Talc, a layered silicate resulting from the inter-twining of pyroxene chains, exhibits a prominent peak at 671 cm−1, denoting decreased transmittance. This peak is distinctive for the symmetric stretching mode of silicon-bridging oxygen–silicon (Si–O–Si) within the pyroxene chains. The strong peak at 1,000 cm−1, indicative of talc’s Si–O symmetric stretching mode, appeared weaker and slightly shifted. This could be attributed to the overlap of symmetric and asymmetric Si–O stretching peaks. The soapstone spectrum displayed closely situated peaks at 915 and 1,000 cm−1, distinguishable primarily by their intensities, as depicted in Figure 2.

The region between 1,000 and 1,450 cm−1 indicates stretching vibration related to silicate groups [24]. The peak at 1,000 cm−1 is associated with the symmetric stretching mode of non-bridging oxygen (Si–O–) in the silicate network. The peak at 1,460 cm−1 represents the bending vibrations of C–H bonds, which suggests the presence of carbonate groups [25]. Furthermore, the vibrational band positions in the range 1,620–3,674 cm−1 correspond to SiO and other interlayer bonds, which remain consistent and unchanged throughout the spectrum. The peak at 1,620 cm−1 is attributed to the presence of hydroxyl groups and is common for O–H bending vibrations [26].

3.3 XRF analysis of the sample

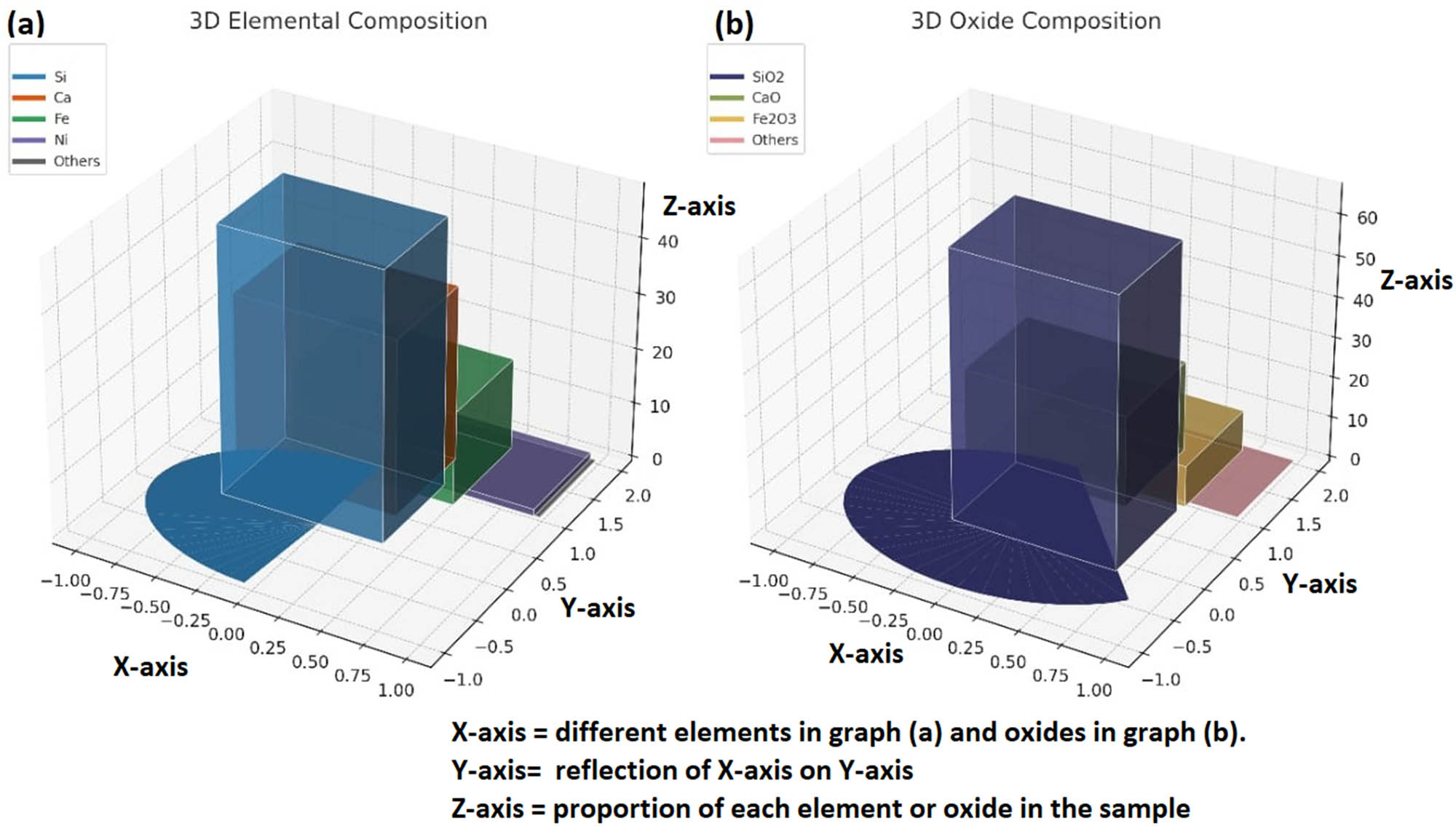

Table 3 displays the XRF quantitative results of the soapstone sample with elemental and oxide compositions. It was observed that Swat soapstone prominently consists of silicon (Si), constituting a significant 48.567 wt% of its composition. Calcium (Ca) constitutes up to 31.933 wt%, indicating its substantial presence, while iron (Fe) contributes 16.708 wt%. Nickel (Ni) is also found, albeit in a minor proportion of 1.22 wt%. The presence of other minerals in the soapstone is minimal (<0.1%). The large amount of Si signifies a stable structure, contributing to the rock’s overall resilience [26]. The presence of calcium suggests involvement in metamorphic processes, contributing strength and structure to the soapstone [27]. Iron imparts color to the soapstone, revealing the rock’s metamorphic history [28]. Nickel is often associated with specific geological conditions, and its presence provides clues about the geological processes that influenced the formation of the rock [29].

XRF analysis of swat soapstone, showing the weight percentages of key elements and the oxide composition, emphasizing the significant presence of silicon dioxide, calcium oxide, and ferric oxide, along with trace oxides

| Elemental composition of swat soapstone | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Si | Ca | Fe | Ni | Cr, Mn, Sr, Cu, Bi, Ag, Zn, Th |

| Result | 48.567% | 31.933% | 16.708% | 1.220% | <0.1% |

| Oxide composition of swat soapstone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | SiO2 | CaO | Fe2O3 | NiO, Cr2O3, MnO, SrO, CuO, Bi2O3, ZnO, ThO2 |

| Result | 65.963% | 22.506% | 10.063% | <0.1% |

Table 3 clearly reveals the substantial presence of 65.963 wt% silicon dioxide (SiO2), 22.506 wt% of calcium oxide (CaO), and 10.063 wt% iron(iii) oxide or ferric oxide (Fe2O3). Trace amounts (<0.1 wt%) of other elements such as nickel(ii) oxide, chromium(iii) oxide, manganese(ii) oxide, strontium oxide, copper(ii) oxide, or cupric oxide, bismuth(iii) oxide, zinc oxide, and thorium dioxide were also determined. The large amount of silicon dioxide in the sample shows that the rock is mainly composed of silicon dioxide. Calcium oxide reinforces the mineralogical strength and stability imparted by calcium. The presence of iron oxides can contribute to the rock’s coloration and reveal oxidative geological processes. Figure 3 shows the elemental and oxide composition of the soapstone in a 3D graph.

(a) and (b) Elemental and oxide composition of the soapstone, respectively.

3.4 SEM and EDX analysis

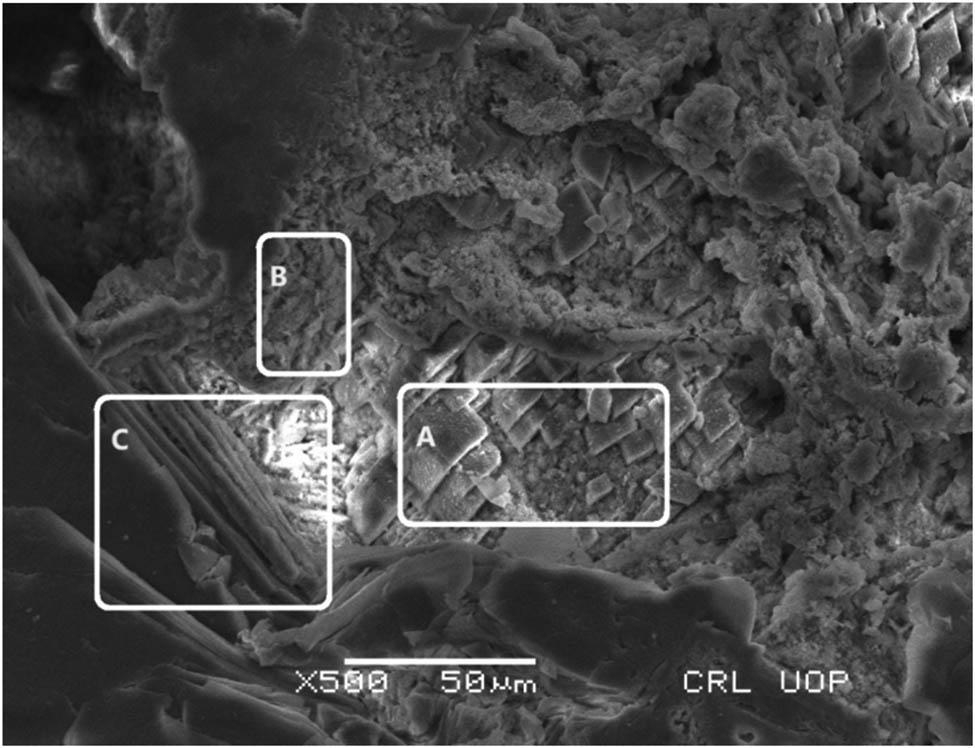

The SEM image in Figure 4 shows the microstructure of the soapstone at a magnification of 500×. This image reveals the presence of three different micro-regions. A crystalline region A has a cuboidal structure, which is a particular feature of the soapstone. A rough region marked as B represents the mineral layers or foliation in the soapstone. Region C represents thin sheets stacked upon each other, which indicates the matrix in which the more defined structures are embedded and is the most prominent property of talc.

Scanning electron micrograph of the soapstone with three different micro-regions marked as A–C, representing crystalline, rough spongy, and homogenous laminar morphologies, respectively.

Elemental analysis of different regions in Figure 4 is presented in Table 4. In region A, the high concentrations of calcium (43.48 wt%) and oxygen (34.63 wt%) indicate a significant presence of calcium and oxygen. This composition suggests a material rich in calcium and oxygen compounds. Moving to region B, the remarkably elevated concentration of iron (92.61 wt%) implies that this region is predominantly composed of pure iron. The overwhelming dominance of iron points to a distinct metallic character in this area. The presence of iron-rich regions may be related to the soapstone’s metamorphic history [30,31]. In region C, the coexistence of iron (33.07 wt%) and silica (41.18 wt%) signifies a composition featuring both iron and silica. This could suggest a mixed mineral composition, potentially indicating the presence of iron and silicates. The mixed composition of iron and silicate minerals was reported in the XRD analysis to be enstatite, represented by the high-intensity peak labeled as “D” in Figure 1.

Elemental composition (wt%) of regions A–C in Figure 4

| Elemental composition (wt%) of soapstone | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-region | EDX data | ||

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | |

| A | O | 34.63 | 53.62 |

| Mg | 16.99 | 17.31 | |

| Ca | 43.48 | 26.94 | |

| Fe | 4.81 | 2.13 | |

| B | O | 2.15 | 6.84 |

| Mg | 1.18 | 2.48 | |

| Si | 2.12 | 3.84 | |

| Ca | 1.94 | 2.47 | |

| Fe | 92.61 | 84.31 | |

| C | O | 8.60 | 16.28 |

| Mg | 17.16 | 21.37 | |

| Si | 41.18 | 44.41 | |

| Fe | 33.07 | 17.94 | |

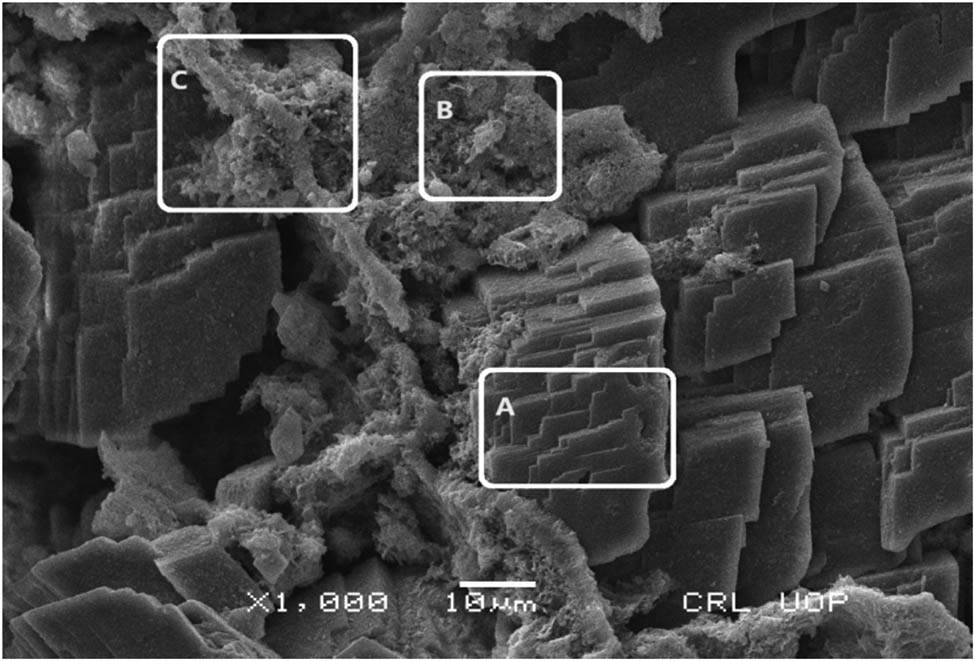

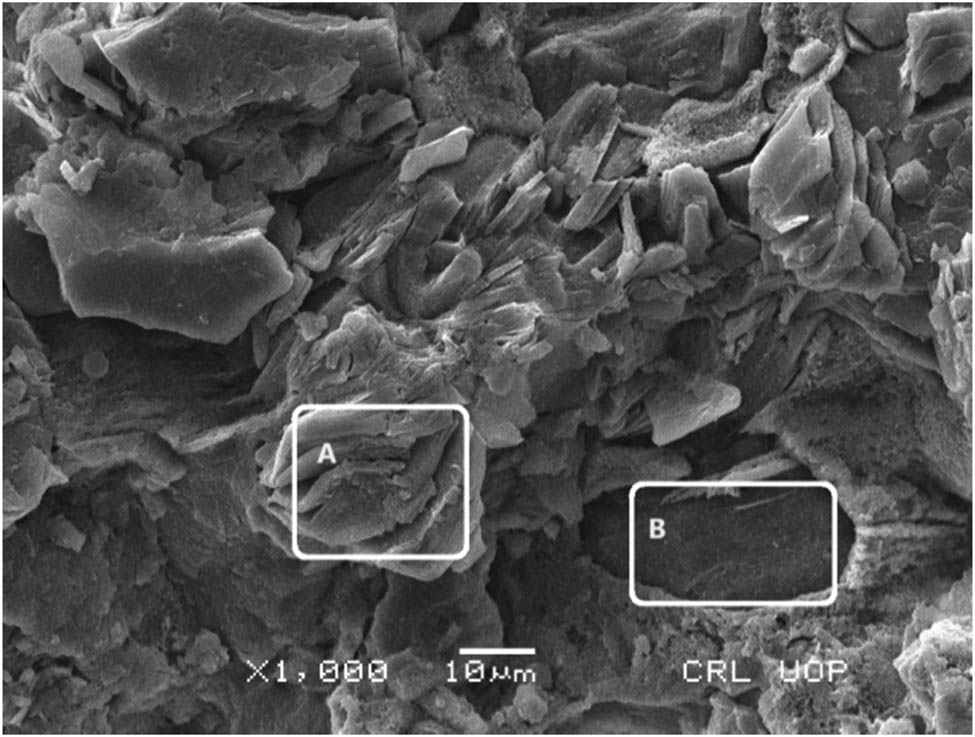

Figure 5 represents the microstructural image of the soapstone at a magnification of 1,000×. Region A in Figure 5 reveals a cubic-like structure, which is the talc and contains high concentrations of Ca and O, as presented in Table 5. Regions B and C exhibit rough and intricate regions containing a high concentration of Fe. It is worth mentioning that regions B and C are located in the same area and share similar compositions, i.e., both have a significant iron content. The elemental composition of these regions is further depicted in Table 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of the soapstone with three different micro-regions marked as A–C. Region A represents a crystalline morphology, which belongs to the talc, while regions B and C represent rough morphology containing a high concentration of iron.

Elemental composition of regions A–C in Figure 5

| Elemental composition (wt%) of soapstone | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-region | EDX data | ||

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | |

| A | C | 11.37 | 22.45 |

| O | 21.85 | 32.38 | |

| Mg | 15.78 | 15.39 | |

| Ca | 48.66 | 28.79 | |

| Fe | 2.34 | 0.99 | |

| B | O | 6.69 | 18.80 |

| Mg | 2.04 | 3.77 | |

| Si | 3.32 | 5.30 | |

| Ca | 3.92 | 4.40 | |

| Mn | 1.09 | 0.89 | |

| Fe | 82.96 | 66.84 | |

| C | O | 9.35 | 24.24 |

| Mg | 4.43 | 7.56 | |

| Si | 4.11 | 6.07 | |

| Ca | 3.89 | 4.02 | |

| Mn | 2.18 | 1.64 | |

| Fe | 76.04 | 56.48 | |

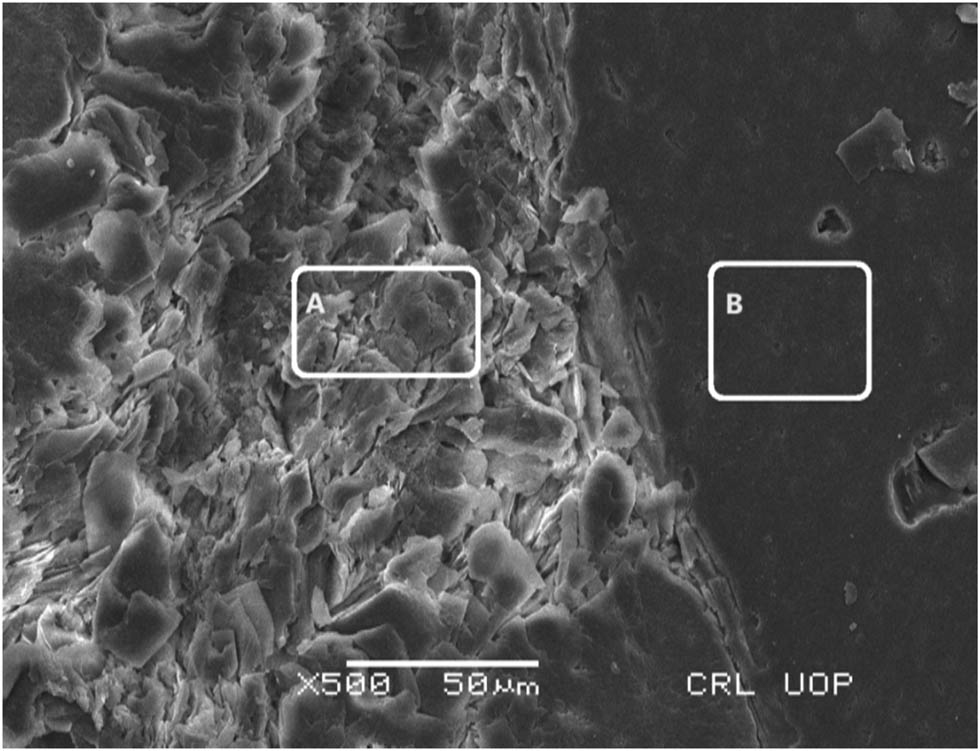

Region A in Figure 6 displays a texture-like structure, which suggests variations in grain size [32]. Region B appears to be more smooth, indicating a homogeneous distribution of talk minerals. Elemental analysis of Figure 6, regions A and B, is shown in Table 6, which indicates that both regions contain identical elements with no discernible variations in their composition or quantity. Being rough, region A scatters more electrons and, therefore, appears bright as compared to region B, although both have the same compositions [33].

Scanning electron micrograph of the soapstone with two micro-regions marked as A and B. Region A represents a texture morphology while region B represents a smooth surface containing a high concentration of iron.

Elemental composition of regions A and B in Figure 6

| Elemental composition (wt%) of soapstone | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-region | EDX data | ||

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | |

| A | O | 11.41 | 20.26 |

| Mg | 22.83 | 26.66 | |

| Al | 12.37 | 13.02 | |

| Si | 24.93 | 25.20 | |

| Ca | 0.82 | 0.58 | |

| Cr | 6.26 | 3.42 | |

| Fe | 21.38 | 10.87 | |

| B | C | 8.91 | 19.30 |

| O | 8.73 | 14.20 | |

| Mg | 19.78 | 21.17 | |

| Al | 11.04 | 10.65 | |

| Si | 22.12 | 20.50 | |

| Ca | 1.17 | 0.76 | |

| Cr | 7.42 | 3.71 | |

| Fe | 20.84 | 9.71 | |

The micro-region depicted in Figure 7, region A, shows a distinct surface texture characterized by its rough and uneven appearance. Notably, silicon (Si) is present in substantial quantities within this textured region given by EDX analysis (Table 7). This suggests that silicon plays a significant role in shaping the texture and structure of this area. Region A, containing Si, is more susceptible to weathering and leads to a rough texture. Secondary mineralization in the silicate minerals in region A is also responsible for its rough texture [34]. Region B in Figure 7 represents a smooth region. In this region, calcium (Ca) is found in abundance, as shown in Table 7. This high concentration of calcium is a defining characteristic of this particular area, setting it apart from other regions observed. Elemental analysis (Table 7) shows that region B in Figure 7 contains no Si content, which indicates the presence of non-silicate phases having different cleavage and fracture properties, resulting in a smoother surface.

Scanning electron micrograph of the soapstone with two micro-regions, marked as A and B. Region A represents a rough morphology with Si content, while region B represents a smooth surface containing Si content.

Elemental composition of regions A and B in Figure 6

| Elemental composition (wt%) of soapstone | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-region | EDX data | ||

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | |

| A | O | 22.65 | 34.40 |

| Mg | 19.27 | 19.26 | |

| Si | 46.56 | 40.30 | |

| Ca | 6.01 | 3.46 | |

| Fe | 5.51 | 2.40 | |

| B | C | 9.00 | 19.01 |

| O | 18.89 | 29.96 | |

| Mg | 16.49 | 17.21 | |

| Ca | 47.85 | 30.29 | |

| Fe | 7.77 | 3.53 | |

4 Conclusion

The study aimed to understand Swat soapstone by conducting experiments to determine its structure, characteristics, and different forms. To do this, we used various tools like XRF analysis, XRD, FTIR, SEM, and EDX spectroscopy to examine the soapstone. From SEM analysis, we found that the nanoparticles possess distinct shapes – some were slightly long with a cubic-like appearance, some formed straight rods, and others had a rough, textured surface. This helped us in determining the physical features of the soapstone. Through XRD and EDX spectra, we identified talc and iron as the main minerals in the soapstone, indicating that it is mostly made up of talc and iron. We also found small amounts of calcium and manganese in certain areas, while the concentrations of other potential minerals were very low. XRF analysis confirmed silicon as the most abundant element (48.567 wt%), followed by significant amounts of calcium (31.933 wt%) and iron (16.108 wt%). This breakdown gave us a precise look at the soapstone’s elemental content. From FTIR spectroscopy, it has been found that the sample absorbed infrared radiation at the non-bridging oxygen (Si–O–) within the silicate network and exhibited the Si–O–Si bending vibration. It has been found that all characterization techniques are in line with each other.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through a Large Research Project (grant number RGP2/525/45).

-

Funding information: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through a Large Research Project (grant number RGP2/525/45).

-

Author contributions: Sajjad Ali contributed to writing the paper, Salar Ahmad performed the experimental work and helped in writing the paper, Asif Iqbal helped in the experimental work, Rizwan Ullah contributed to drawing the graphs and organizing the tables, Ikram Ullah performed the mathematical analysis while Muhammad Mehtab Alam and Ali Hasan Ali helped in the review and calculations. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Edwards, H.G.M. Porcelain and its composition. 18th and 19th Century Porcelain Analysis, 2020, pp. 1–35.10.1007/978-3-030-42192-2_1Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Davies, N. and E. Jokiniemi. Dictionary of architecture and building construction, Routledge, London, 2008.10.4324/9780080878744Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Malkani, M.S. and Z. Mahmood. Mineral resources of Pakistan: a review, Geological Survey of Pakistan, Record, 2016. Vol. 128, pp. 1–90.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Kumari, N. and C. Mohan. Basics of clay minerals and their characteristic properties. Clay and Clay Minerals, Vol. 24, 2021, pp. 1–29.10.5772/intechopen.97672Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Huhta, A. and A. Kärki. A proposal for the definition, nomenclature, and classification of soapstones. GFF, Vol. 140, No. 1, 2018, pp. 38–43.10.1080/11035897.2018.1432681Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Vavro, M., J. Gajda, R. Přikryl, and P. Siegl. Soapstone as a locally used and limited sculptural material in remote area of Northern Moravia (Czech Republic). Environmental Earth Sciences, Vol. 73, 2015, pp. 4557–4571.10.1007/s12665-014-3742-3Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Kakoko, L. D., Y. A. C. Jande, and T. Kivevele. Experimental investigation of soapstone and granite rocks as energy-storage materials for concentrated solar power generation and solar drying technology. ACS Omega, Vol. 8, 2023, pp. 18554–18565.10.1021/acsomega.3c00314Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Chisenga, C., J. Yan, J. Zhao, E. A. Atekwana, and R. Steffen. Density structure of the Rümker region in the northern oceanus procellarum: Implications for lunar volcanism and landing site selection for the Chang’E‐5 mission. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, Vol. 125, No. 1, 2020, id. e2019JE005978.10.1029/2019JE005978Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Olsen, Y., J. K. Nøjgaard, H. R. Olesen, J. Brandt, T. Sigsgaard, S. C. Pryor, et al. Emissions and source allocation of carbonaceous air pollutants from wood stoves in developed countries: A review. Atmospheric Pollution Research, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2020, pp. 234–251.10.1016/j.apr.2019.10.007Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Kora, A. J. Traditional soapstone storage, serving, and cookware used in the Southern states of India and its culinary importance. Bulletin of the National Research Centre, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2020, pp. 1–9.10.1186/s42269-020-00340-wSuche in Google Scholar

[11] Shahraki, A., S. Ghasemi-Kahrizsangi, and A. Nemati. Performance improvement of MgO-CaO refractories by the addition of nano-sized Al2O3. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 198, 2017, pp. 354–359.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.06.026Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Winkler, E. M. Stone: properties, durability in man’s environment, Vol. 4, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Olivieri, L. M. and A. Filigenzi. On Gandhāran sculptural production from Swat: recent archaeological and chronological data, Academia, London, 2018, pp. 71–92.10.2307/jj.15135994.10Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Malkani, M. S., Z. Mahmood, M. I. Alyani, and M. Siraj. Mineral Resources of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, Pakistan. Geological Survey of Pakistan, Vol. 996, 2017, pp. 1–61.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Malkani, M. S., M. H. Khosa, M. I. Alyani, K. Khan, N. Somro, T. Zafar, et al. Mineral Deposits of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, Pakistan. Lasbela University Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 6, 2017, pp. 23–46.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Karampelas, S., L. Kiefert, D. Bersani, and P. Vandenabeele. Gems and Gemmology, Springer, Cham, 2020.10.1007/978-3-030-35449-7Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Mota, L. M., D. N. Nicomedes, A. P. Barboza, S. L. de Moraes Ramos, R. Vasconcellos, N. V. Medrado, et al. Soapstone reinforced hydroxyapatite coatings for biomedical applications. Surface and Coatings Technology, Vol. 397, 2020, id. 126005.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.126005Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Pulivarti, S. R. and A. K. Birru. Effect of mould coatings and pouring temperature on the fluidity of different thin cross-sections of A206 alloy by sand casting. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals, Vol. 71, No. 7, 2018, pp. 1735–1745.10.1007/s12666-018-1311-2Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Borralleras, P., I. Segura, M. A. Aranda, and A. Aguado. Influence of experimental procedure on d-spacing measurement by XRD of montmorillonite clay pastes containing PCE-based superplasticizer. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 116, 2019, pp. 266–272.10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.11.015Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Balan, E., L. Paulatto, Q. Deng, K. Béneut, M. Guillaumet, and B. Baptiste. Molecular overtones and two-phonon combination bands in the near-infrared spectra of talc, brucite and lizardite. European Journal of Mineralogy, Vol. 34, No. 6, 2022, pp. 627–643.10.5194/ejm-34-627-2022Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Halasz, I., B. Moden, A. Petushkov, J. J. Liang, and M. Agarwal. Delicate distinction between OH groups on proton-exchanged H-chabazite and H-SAPO-34 molecular sieves. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, Vol. 119, No. 42, 2015, pp. 24046–24055.10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b09247Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Madejová, J., W. P. Gates, and S. Petit. IR spectra of clay minerals. In Developments in clay science, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 107–149.10.1016/B978-0-08-100355-8.00005-9Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Zhu, J., W. Xu, Y. Yang, R. Kong, and J. Wang. Vibrational and structural insight into silicate minerals by mid-infrared absorption and emission spectroscopies. Physics and Chemistry of Minerals, Vol. 49, No. 3, 2022, id. 6.10.1007/s00269-022-01180-ySuche in Google Scholar

[24] Frost, R. L., R. Scholz, and A. López. Infrared and Raman spectroscopic characterization of the carbonate bearing silicate mineral aerinite–Implications for the molecular structure. Journal of Molecular Structure, Vol. 1097, 2015, pp. 1–5.10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.05.008Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Vayssilov, G. N., M. Mihaylov, P. S. Petkov, K. I. Hadjiivanov, and K. M. Neyman. Reassignment of the vibrational spectra of carbonates, formates, and related surface species on ceria: a combined density functional and infrared spectroscopy investigation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, Vol. 115, No. 47, 2011, pp. 23435–23454.10.1021/jp208050aSuche in Google Scholar

[26] Burneau, A., O. Barres, J. P. Gallas, and J. C. Lavalley. Comparative study of the surface hydroxyl groups of fumed and precipitated silicas. 2. Characterization by infrared spectroscopy of the interactions with water. Langmuir, Vol. 6, No. 8, 1990, pp. 1364–1372.10.1021/la00098a008Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Jamtveit, B., H. Austrheim, and A. Putnis. Disequilibrium metamorphism of stressed lithosphere. Earth-Science Reviews, Vol. 154, 2016, pp. 1–13.10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.12.002Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Storemyr, P. and T. Heldal. Soapstone production through Norwegian history: Geology, properties, quarrying and use, Herz Jr. J. J. and R. Newman, eds., 2002, Vol. 5, pp. 359–369.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Hoatson, D. M., S. Jaireth, and A. L. Jaques. Nickel sulfide deposits in Australia: Characteristics, resources, and potential. Ore Geology Reviews, Vol. 29, No. 3–4, 2006, pp. 177–241.10.1016/j.oregeorev.2006.05.002Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Wall, S., N. Eby, E. Winter, G. Mairo, C. White, and L. I. Ranger. Geoarchaeological Traverse: Soapstone, Clay And Bog Iron In Andover, Middleton, Danvers And Saugus, Conference work, New England Intercollegiate Geological Conference, Salem, MA, pp. 257–276.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Alia, S., S. Ahmad, S. A. Ali, L. Khalid, and I. Ullah. Synthesis and Characterization of Lithium Manganese Oxide (LiMn2O4) from Manganese Ore via Solid State Reaction Route, Pakistan Journal of Scientific & Industrial Research Series A: Physical Sciences, Vol. 66, No. 3, 2023, pp. 221–226.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Ahmad, S., S. Ali, I. Ullah, M. S. Zobaer, A. Albakri, and T. Muhammad. Synthesis and characterization of manganese ferrite from low grade manganese ore through solid state reaction route. Scientific reports, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2021, id. 16190.10.1038/s41598-021-95625-zSuche in Google Scholar

[33] Akhtar, K., S. A. Khan, S. B. Khan, and A. M. Asiri. Scanning electron microscopy: Principle and applications in nanomaterials characterization. In Handbook of materials characterization, 2018, pp. 113–145.10.1007/978-3-319-92955-2_4Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Alexandrowicz, Z., M. Marszałek, and G. Rzepa. Distribution of secondary minerals in crusts developed on sandstone exposures. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2014, pp. 320–335.10.1002/esp.3449Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete