Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

-

Wenjuan Zhang

, Yuheng Li

, Yezhi Ding

Abstract

Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon (Fe0/OMC) was synthesized using triblock copolymers as templates and through solvent evaporation self-assembly, followed by a carbothermal reduction. Fe0/OMC had three microstructures of two-dimensional hexagonal (space group, p6mm, Fe0/OMC-1), body centered cubic (Im3̄m, Fe0/OMC-2), and face centered cubic (Fm3̄m, Fe0/OMC-3) which were controlled by simply adjusting the template. All Fe0/OMC displayed paramagnetic characteristics, with a maximum saturation magnetization of 50.1 emu·g−1. This high magnetization is advantageous for the swift extraction of the adsorbent from the solution following the adsorption process. Fe0/OMC was used as an adsorbent for the removal of silver ions (Ag(i)) from aqueous solutions, and the adsorption capacity of Fe0/OMC-1 was enhanced by the functionalization of Fe0. Adsorption property of Fe0/OMC-1 was significantly higher than that of Fe0/OMC-2 and Fe0/OMC-3, indicating that the long and straight ordered pore channels were more favorable for adsorption, and the adsorption capacity of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC-1 was 233 mg·g−1. The adsorption process exhibited conformity with both the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and the Freundlich model, suggesting that the dominant mechanism of adsorption involved multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces.

1 Introduction

As industrialization has progressed, the pollution resulting from heavy metal wastewater has become increasingly severe. The presence of heavy metals ions in the environment poses a threat to both the ecosystem and human health [1,2]. Nowadays, the problem of water pollution has been paid more and more attention by the researchers and the general public because of its potential threat to human existence. Particularly, heavy metal ions are considered as one of the biggest challenges for environmentalists due to its high toxic and non-biodegradable nature. Moreover, they may accumulate in the body through the food chain, which is harmful to the ecosystem and human health. Therefore, it is very important to find a suitable method for the removal of such toxic metal ions from the waste water [3]. Silver is recognized as one of the most significant heavy metals. Silver, with its exceptional electrical and thermal conductivity, outperforms other metals in these aspects. It also exhibits superior resistance to corrosion and oxidation, making it highly desirable for various applications. Due to these characteristics, silver found extensive application in various industrial sectors, including the manufacturing of mirrors, photographic films, batteries, and electronic devices [4]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that silver is also recognized as a potentially toxic substance, and high concentrations of silver can lead to adverse health effects, such as liver and kidney degeneration, as well as respiratory disorders [5]. The toxicity of silver, combined with its significant economic value, has created a demand for a treatment method that can effectively remove this metal from wastewater while also recovering the valuable material. This approach aims to prevent ecological destruction and promote sustainable practices. Many methods of removing heavy metal have been reported, including precipitation, oxidation, membrane filtration, reduction, ion exchange, and adsorption [6]. Among these different methods, adsorption method had proven to be an effective and economical treatment process [7].

Herman et al. prepared mercapto-functionalized porous silica particles using (3-mercaptopropyl)-trimethoxysilane co-gelation, and the resulting short-range ordered porous silica particles were particularly effective adsorbents for aqueous-phase silver ions (Ag(i)). The binding of Ag(i) in aqueous solution was almost stoichiometric over a wide range of pH 4.0–9.0, even at lower Ag(i) concentrations, until the limiting adsorption amount of 238 mg g−1 was reached. Furthermore, washing with 10 mM Na2S2O3 solution resulted in almost complete recovery of Ag(i) and regeneration of the adsorbent [8]. Al-Anber et al. successfully loaded (Ag(i)) onto a specially functionalized silica matrix, termed SG-Cys-Na+, by batch sorption technique utilizing cysteine-functionalized silica (SG-Cys-Na+) against fully loaded Ag(i). And under certain conditions, an impressive 98% loading efficiency was obtained. This chemisorption involves strong chemical bonding between the Ag(i) and the carboxylate groups (–COO–Na+) of functionalized silica gel. Valuable insights into the potential application of SG-Cys-Na+ matrix as a highly efficient filtration of Ag(i) from aqueous solutions were provided [9]. Fan et al. prepared passion fruit shell source s-doped porous carbon (SPC) by hydrothermal carbonization and KOH/(NH4)2SO4 activation. The optimized SPC-3 showed a maximum adsorption of Ag(i) up to 115 mg·g−1 in 0.5 mol·L−1 HNO3 solution. SPC-3 showed good selectivity for a variety of competing cations, Ag(i), which was mainly attributed to the formation of Ag2S nanoparticles due to the strong bonding between the Ag(i) ions and the sulfur-containing functional groups on the surface of SPC-3 [10].

Nanoscale zero valent iron (nZVI, Fe0) was an environmental-friendly nanomaterial with great magnetic properties and high specific surface area. Fe0 nanoparticles were highly beneficial for adsorptive removal of silver. Fe0 nanoparticles were a strong reductant due to the low standard redox potential (E ɵ = −0.44 V) of Fe2+/Fe0 couple [11,12]. Fe0 displayed great potential in the removal of environmental contaminants such as trichloroethylene, chlorinated methane, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, nitroaromatics, nitrate, and heavy metal ions. Fe0 nanoparticles have demonstrated a versatile ability to reduce heavy metals present in wastewater. The mechanisms of heavy metal removal by Fe0 nanoparticles involves reduction, adsorption, and co-precipitation [13]. These combined processes effectively facilitate the removal of heavy metals from wastewater. Consequently, the utilization of Fe0 as a reducing agent offers a simple and convenient method to mitigate heavy metal pollution in wastewater. However, the use of Fe0 nanoparticles alone to remove contaminants from water might not be very effective for the following reasons: 1) Fe0 nanoparticles show a high tendency to agglomerate because of the magnetic forces, gravitational forces, and high interfacial energies, resulting in reduced surface area and reactivity. 2) The environmental exposure of bare Fe0 nanoparticles was found to be unstable, posing significant challenges for the practical application of environmental remediation [14].

In order to overcome these problems, fixing the Fe0 nanoparticles in or on the supports could provide sufficient loading sites for the immobilization of Fe0 nanoparticles preventing them from being oxidized and agglomerated. Various supports, such as amorphous activated carbon, molecular sieves, polymers, etc., [15,16] had been reported as supports to protect Fe0 nanoparticles from agglomeration and oxidation. However, these approaches might inhibit the reaction of Fe0 nanoparticles with pollutants or endow Fe0 nanoparticles with undesirable properties for environmental remediation. Immobilization of Fe0 nanoparticles in porous carbon had been considered to improve their dispersibility and reactivity [17,18,19]. Mesoporous carbon materials were considered to be an available support due to their great physicochemical properties. Serving as the support for Fe0, mesoporous carbon had a large specific surface area and thermal stability, which could provide excellent adsorption properties. In addition, the mesoporous carbon could effectively control the size of Fe0 nanoparticles. Lin and Chen successfully synthesized mesoporous Fe/carbon aerogel and employed it for the adsorption of arsenic ions. The maximum adsorption capacity for arsenic ions was found to be 216.9 mg·g−1 [20]. Fixing Fe0 nanoparticles in mesoporous carbon effectively elevated the adsorption performance of Fe0 nanoparticles. But the mesoporous carbon was associated with certain drawbacks, such as the disordered and collapsed structure that might block the pore channels [21]. To begin with, porous carbon materials with a porous structure could effectively prevent the agglomeration of iron nanoparticles by confining and dispersing them. Furthermore, the distinctive surface properties and electronic properties of carbon materials contribute positively to charge transfer and accumulate Ag(i). Finally, carbon materials had the high stability in acid and alkali environments, which were very important for the regeneration of the adsorbent and the recovery of Ag(i) [22].

Recently, high-ordered mesoporous carbon materials (OMC) with large surface area and high porosity have been reported, as a kind of multifunctional nanomaterial, it has great potential in the fields of catalysis, adsorption and separation, hydrogen and methane storage, supercapacitor, and so on [23].

The Pt-OMC catalysts synthesized by Liu et al. exhibited superior electrocatalytic properties in the oxygen reduction reaction when compared to typical commercial electrocatalysts. This indicates that Pt-OMC holds great potential as an efficient and effective catalyst for electrochemical processes, offering improved performance and enhanced catalytic activity [24]. Li et al. successfully synthesized biomass derived ordered mesoporous carbon (BOMC) materials, which exhibited a high Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of 1,385 m2·g−1. In addition, they also prepared iron-impregnated BOMC (Fe/BOMC) materials with a slightly reduced BET surface area of 1,012 m2·g−1. These materials with their large surface areas offer a significant amount of active sites for adsorption and catalytic applications, making them promising candidates for various environmental and energy-related applications. These materials were employed for the adsorption of Pb(ii) and Cr(iii) [25]. The presence of a considerable number of mesopores within iron-impregnated BOMC (Fe/BOMC) enhances the diffusion of metal ions. This structural characteristic allows for efficient uptake of metal contaminants from solution. In the case of Fe/BOMC, the maximum adsorption capacity for Pb(ii) was determined to be 123 mg·g−1, while for Cr(iii), it was found to be 46 mg·g−1. These values indicate the high adsorption efficiency of Fe/BOMC in removing these heavy metal ions from wastewater, highlighting its potential for environmental remediation applications. Consequently, OMC has demonstrated significant potential as a support material for nanoparticles, primarily due to its numerous advantages in the adsorption and delivery of heavy metal ions. The BET surface areas of mesoporous carbon did not completely determine the adsorption and separation property of the materials, and their mesostructures had an excellent influence on the transfer and adsorption of pollutants. The various porous structures showed not only the different transport capacities but also the different load forms of metals, including dispersion on the surface of the material and filling into the inside of the pores. However, studies on the transport capacity and adsorption properties of the porous structure of Fe0/OMC for metal ions were lacking. OMC materials had been synthesized with various porous structures, which could be attributed to the use of different raw materials and synthetic methods. Depending on the specific combination of precursors and synthesis conditions, OMC could exhibit diverse porous structures, including two-dimensional hexagonal, three-dimensional cubic, lamellar, and more. These distinct structures contribute to the unique properties and applications of OMC materials, allowing for tailoring their characteristics to specific needs in various fields such as adsorption, catalysis, and energy storage [26].

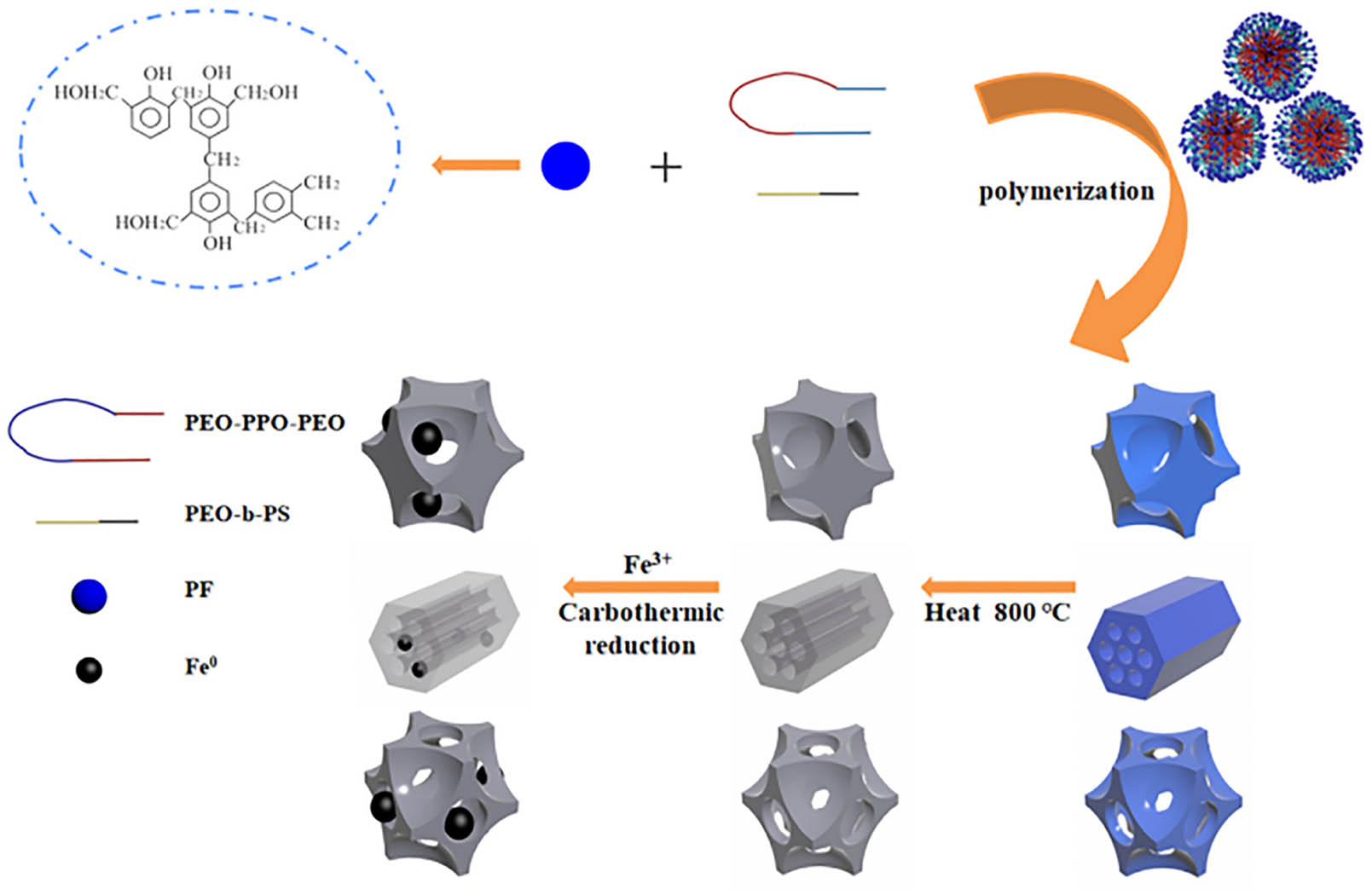

In this work, Fe0/OMC was prepared through a two-step synthesis that involved the formation of OMC by using triblock copolymers as templates and through a solvent evaporation self-assembly approach, followed by a carbothermal reduction of Fe3+ solutions at high temperatures under Ar atmosphere to form Fe0/OMC. The surface morphology, chemical composition, and magnetic properties of the Fe0/OMC were characterized and extensive investigation of the adsorption capacity of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC in aqueous solutions were performed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Triblock poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(propylene oxide)-b-poly(ethylene oxide) copolymer Pluronic F127 (PEO106PPO70PEO106) and diblock poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(styrene) copolymer (PEO100-PS114) were purchased from Aldrich. Phenol, formaldehyde, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), ethanol, silver nitrate, potassium periodate (KIO4), and potassium persulfate (K2S2O8) were obtained from Tianjin Chemical. All reagents were used as received without further purification.

2.2 Synthesis of OMC

OMC was prepared according to the method reported by Zhao et al. [27,28]. In a typical synthesis procedure, 6.1 g of phenol was melted at 40°C. Subsequently, 1.3 g of 20 wt% NaOH was slowly added to the melted phenol with continuous stirring. Following the dropwise addition of 10.5 g of 37 wt% formaldehyde solution, the reaction mixture was stirred at 70°C for 1 h. Once the mixture cooled to room temperature, the pH was adjusted to neutral using a 0.6 M HCl solution. The resulting mixture was then subjected to rotational evaporator for 2 h at 45°C to obtain a viscous liquid. The final sample was re-dissolved in ethanol to form a 20 wt% ethanol solution.

To obtain OMC-1 and OMC-2 the following steps were followed. First, 1.0 g of F127 was dissolved in ethanol to form a homogeneous solution. Then, solutions containing 5.0 or 10.0 g of ethanol was added dropwise to the mixture while stirring for 30 min. The resulting solution was transferred to an evaporating dish and left to evaporate at room temperature overnight, resulting in the formation of a transparent film. This film was then heated in an oven at 100°C for 24 h to thermopolymerize the phenolic resins in the film. Finally, the products were carbonized by heating them at a rate of 5 °C·min−1 under an Ar atmosphere, reaching a temperature of 800°C and maintaining it for 2 h. These samples were named OMC-1 and OMC-2, respectively.

0.1 g PEO100-PS114 was dissolved in 4.9 g of tetrahydrofuran solution and stirred well, and then 0.4 g phenolic resin was dissolved in 1.6 g tetrahydrofuran solution. The two solutions that had been mixed were stirred for 30 min to form a homogeneous solution. The following procedure was similar to that for the synthesis of OMC-1. The obtained sample was named OMC-3.

2.3 Synthesis of Fe0/OMC

Fe0/OMC was synthesized using the incipient wetness impregnation and carbothermic reduction. The synthesis procedure involved the following steps:

0.375 g FeCl3·6H2O was dissolved into a small amount of ultrapure water. Then, OMC was added to the previous FeCl3 solution and stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The obtained black precipitates were cleaned and dried in an oven at 50°C for 24 h. Finally, the black precipitates were carbonized in a tube furnace at 900°C for 2 h under an Ar atmosphere. This synthesis method allowed for the preparation of Fe0/OMC composites with different OMC, denoted by the sample names Fe0/OMC-1, Fe0/OMC-2, and Fe0/OMC-3.

2.4 Characterization

The phase composition and ordered intensity of Fe0/OMC were analyzed using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) with SAXSess mc2 mode. Additionally, wide-angle XRD (Rigaku D/max2600) was performed under the conditions of Cu Kα radiation, with a current of 100 mA and a voltage of 40 kV. The morphology and mesostructure of Fe0/OMC were investigated by TEM (FEI, Tecnai TF20). The specific surface area of the sample was determined by the BET (Micromeritics ASAP 2460) method, which involves analyzing the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm at a temperature of 77 K. The pore volume and pore size distribution were calculated using the BJH method. Additionally, the functional groups presenting on the surface of the sample were examined using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR, NICOLET iS10) spectroscopy. FTIR samples were mixed with dried KBr and pressed as pellets prior to the collection of spectra that covered wave numbers from 500 to 4,000 cm−1. The magnetic properties of Fe0/OMC were analyzed using a vibration sample magnetometer (VSM, Lakeshore, 7407-S). The magnetic field strength was measured within a range of −1.5 to 1.5 T to characterize the magnetization behavior of the Fe0/OMC sample.

2.5 Adsorption experiments of Ag(i)

The adsorption performance of Fe0/OMC on Ag(i) in an aqueous solution was investigated using the static adsorption method. A concentration of 1 g·L−1 of Ag(i) was prepared by dissolving a specific quantity of AgNO3 in ultrapure water. To prepare different concentrations of Ag(i), the stock solution was diluted accordingly. A 0.0625 mol·L−1 KIO4 solution and a 2 wt% K2S2O8 solution were utilized as chromogenic agents for Ag(i). The absorbance of the solution was measured at a wavelength of 365 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The concentration of Ag(i) was calculated from the standard curve of Ag(i).

The batch experiments for the adsorption of Ag(i) were conducted in a 250 mL sealed conical flask. In each experiment, 10 mg Fe0/OMC was added to the flask along with 50 mL of Ag(i) solution at different initial concentrations. The mixture was sonicated and dispersed for 30 min and then placed in a constant temperature oscillator at 298 K and 120 rpm for 24 h.

The aim of the experiments was to investigate the effects of the initial concentration of Ag(i) and the adsorption time on the adsorption capacity of Fe0/OMC. The initial concentration of Ag(i) solution ranged from 10 to 100 mg·L−1, and the adsorption time varied from 0 to 24 h.

The equilibrium adsorption capacity of Ag(i) and the removal rate were determined using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively. These equations provide quantitative measures of the amount of Ag(i) adsorbed onto Fe0/OMC and the efficiency of Ag(i) removal.

These equations allow for the calculation of the equilibrium adsorption capacity (Q e) and the removal rate (R) of Ag(i) by Fe0/OMC. The equilibrium adsorption capacity represents the amount of Ag(i) adsorbed per unit mass of Fe0/OMC at equilibrium. The removal rate indicates the percentage of Ag(i) removed from the initial concentration in the solution.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structures and morphologies of OMC

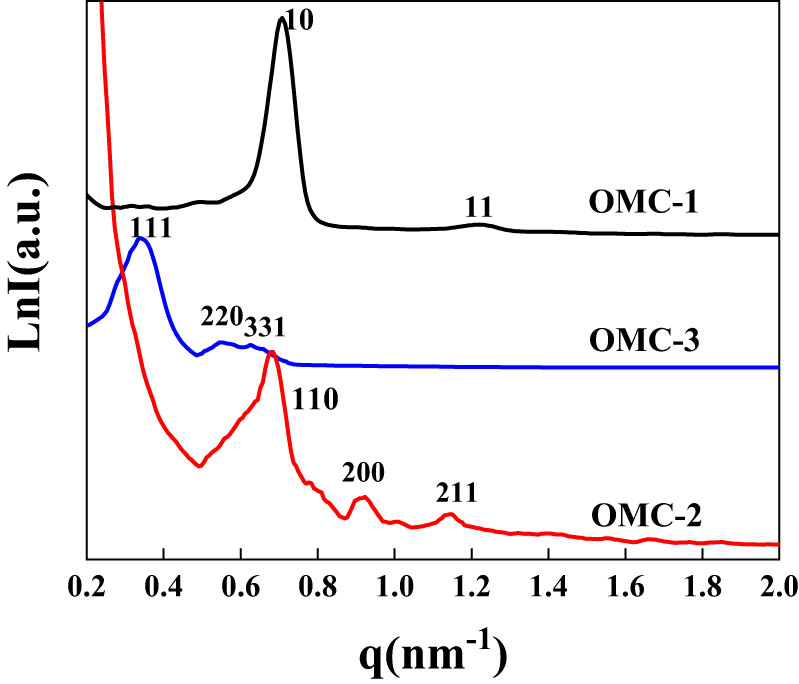

OMC was synthesized by a facile solvent evaporation induced self-assembly (EISA) strategy with resol as a carbon source (Scheme 1). SAXS patterns were investigated to verify the successful synthesis of OMC with tailored mesostructure as shown in Figure 1. OMC-1 showed two legible diffraction peaks that could correspond to the (10) and (11) planes of the the two-dimensional hexagonal (p6mm) structure. The three diffraction peaks in the SAXS patterns of OMC-2 could correspond to the (110), (200), and (211) planes, associated with the body-centered cubic (Im3̄m) structure. Three diffraction peaks in the SAXS patterns of OMC-3 could also be indexed as (111), (220), and (331) planes, indicating that OMC-3 had an face-centered cubic (Fm3̄m) structure. OMC possessed the highly ordered arrangements of mesopores.

Synthetic route of Fe nanoparticle-functionalized mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructure.

SAXS patterns of OMC.

Figure 2 shows TEM images of OMC-1 viewed along the [001] and [110] directions, OMC-2 viewed along the [111] and [110] directions, and OMC-3 viewed along the [111] and [110] directions. The regular arrangement of the pore channels show that the synthesized OMC-1, OMC-2, and OMC-3 had highly ordered and homogeneous pore channel structures. The observed structures of the samples, namely, the well-ordered two-dimensional hexagonal and body-centered cubic and face-centered cubic mesoporous structures, are consistent with the results obtained from the SAXS patterns. These further demonstrate that OMC with three mesoporous structures were successfully obtained.

![Figure 2

TEM images of OMC-1 viewed along the [001] (a) and [110] (b) directions, OMC-2 viewed along the [111] (c) and [110] (d) directions, and OMC-3 viewed along the [111] (e) and [110] (f) directions.](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0007/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0007_fig_002.jpg)

TEM images of OMC-1 viewed along the [001] (a) and [110] (b) directions, OMC-2 viewed along the [111] (c) and [110] (d) directions, and OMC-3 viewed along the [111] (e) and [110] (f) directions.

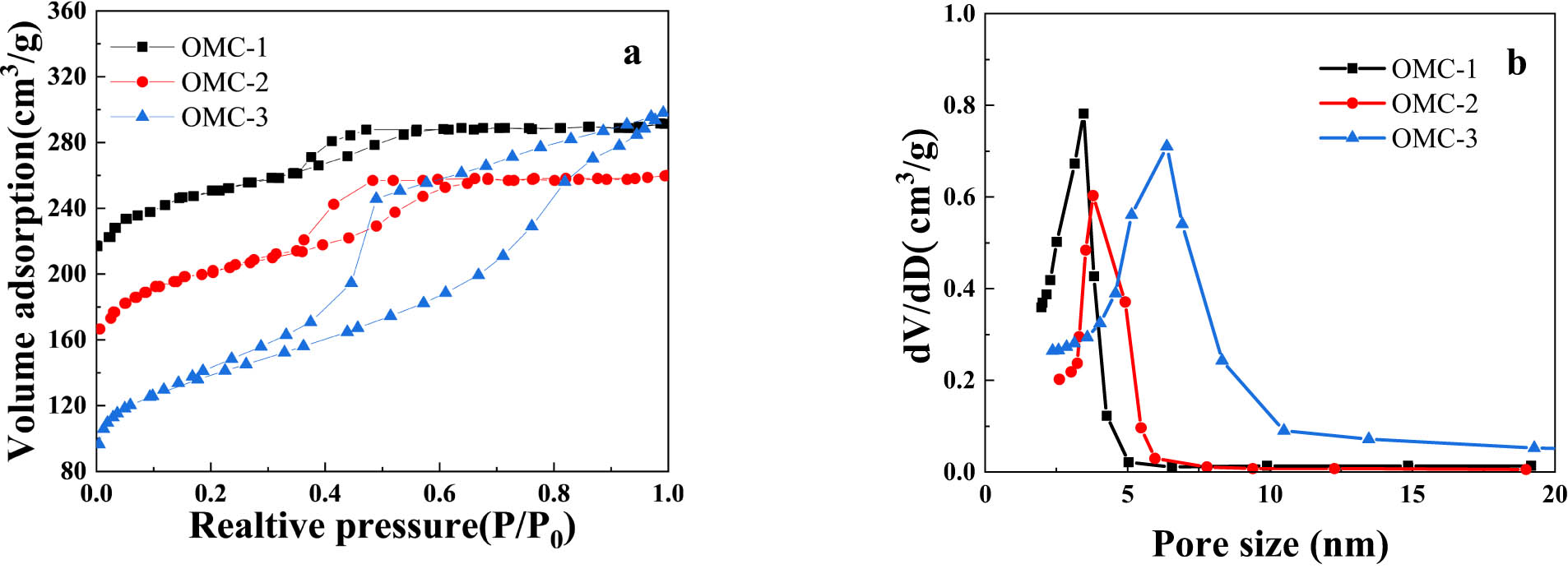

In order to analyze the pore structures of OMC, the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of N2 were conducted. Figure 3 shows the isotherms of OMC, which exhibit type IV adsorption isotherms according to the classification defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). These isotherms display an evident H1-type hysteresis loop, with a smooth increase in the medium pressure range (P/P 0 = 0.3–0.8), indicating the presence of regularly arranged mesopores.

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms (a) and pore size distribution (b) of OMC.

Table 1 presents the specific surface area and pore volume of OMC samples. OMC-1 exhibits relatively high specific surface area (649 m²·g−1) and pore volume (0.32 cm³·g−1); OMC-2 and OMC-3 show hysteresis rings in the same relative pressure range, suggesting similar pore structures, but their specific surface areas are lower than that of OMC-1.

Structure and pore properties of OMC

| Sample | BET surface area (m²·g−1) | Pore volume (cm³·g−1) | t-Plot micropore volume (cm³·g−1) | Pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMC-1 | 676 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 3.4 |

| OMC-2 | 481 | 0.40 | 0.12 | 3.7 |

| OMC-3 | 627 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 6.4 |

3.2 Structures and morphologies of Fe0/OMC

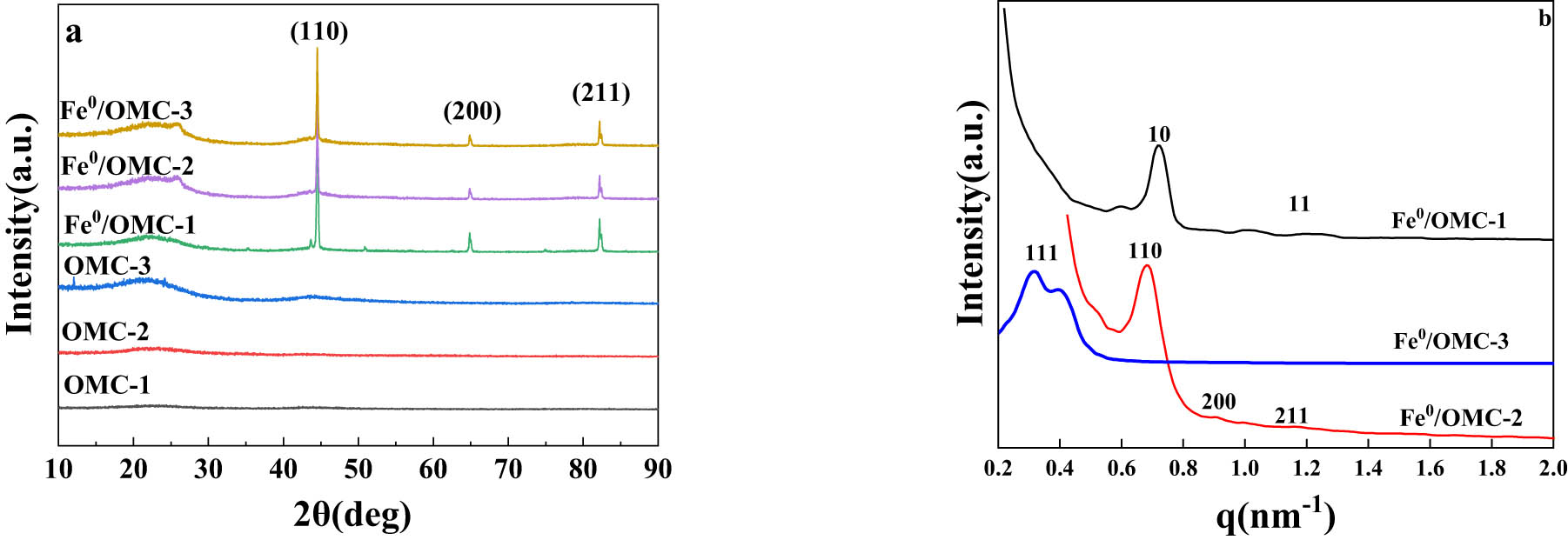

The WAXS patterns of OMC and Fe0/OMC are shown in Figure 4(a). In the case of Fe0/OMC, all three types of Fe0/OMC exhibited three distinct sharp peaks at 44.2°, 65.0°, and 82.3°, which corresponded to the (110), (200), and (211) crystallographic planes, respectively. These diffraction patterns are consistent with the body-centered cubic α-Fe structure (JCPDS No. 06-0696). Based on these findings, it is suggested that the presence of OMC acts as a protective agent, helping to prevent the oxidation of Fe0 and allowing for a greater amount of Fe0 to be preserved in the material. SAXS patterns of Fe0/OMC are shown in Figure 4(b). Similar to the SAXS patterns of Fe0/OMC, the intensity of diffraction peak of Fe0/OMC only decreased slightly, due to the impregnation of Fe0 nanoparticles. This suggested that the regularity of mesostructure of OMC is still maintained after the loading of Fe0 nanoparticles.

Wide angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) patterns (a) of OMC and Fe0/OMC; SAXS patterns of Fe0/OMC (b).

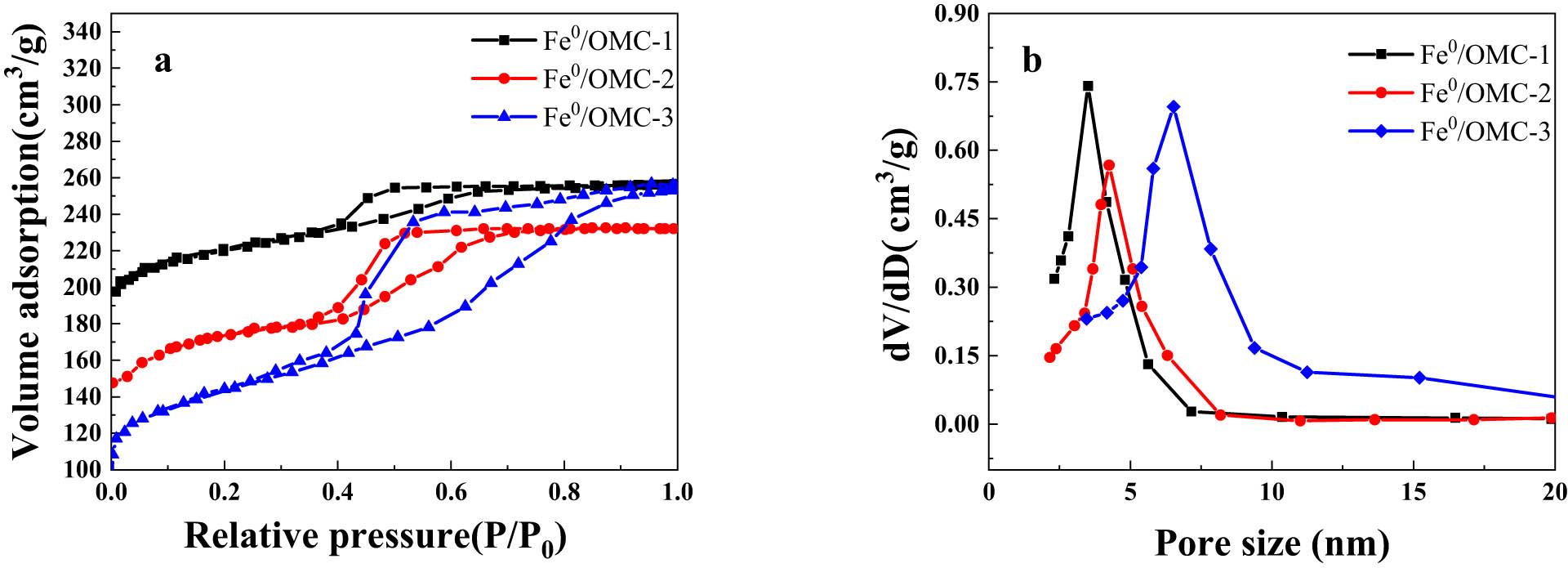

The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms were measured to elucidate the mesoporous structures of various Fe0/OMC. Figure 5 shows that Fe0/OMC has the type IV adsorption isotherms defined by the IUPAC, with an obvious H2-type hysteresis loop, and a smooth rise in the medium pressure region (P/P 0 = 0.4–0.7), which indicated the presence of regularly arranged mesopores. Comparing Table 2 with Table 1, the specific surface area and pore volume decreased after the loading of Fe0 nanoparticles. Notably, the pore size was basically unchanged because the pore structure was destroyed during the synthesis of Fe0 nanoparticles, rather than expanding the pore size.

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms (a) and pore size distribution (b) of Fe0/OMC.

Structure and pore properties of Fe0/OMC

| Sample | BET surface area (m²·g−1) | Pore volume (cm³·g−1) | t-Plot micropore volume (cm³·g−1) | Pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe0/OMC-1 | 583 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 3.5 |

| Fe0/OMC-2 | 397 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 4.2 |

| Fe0/OMC-3 | 542 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 6.5 |

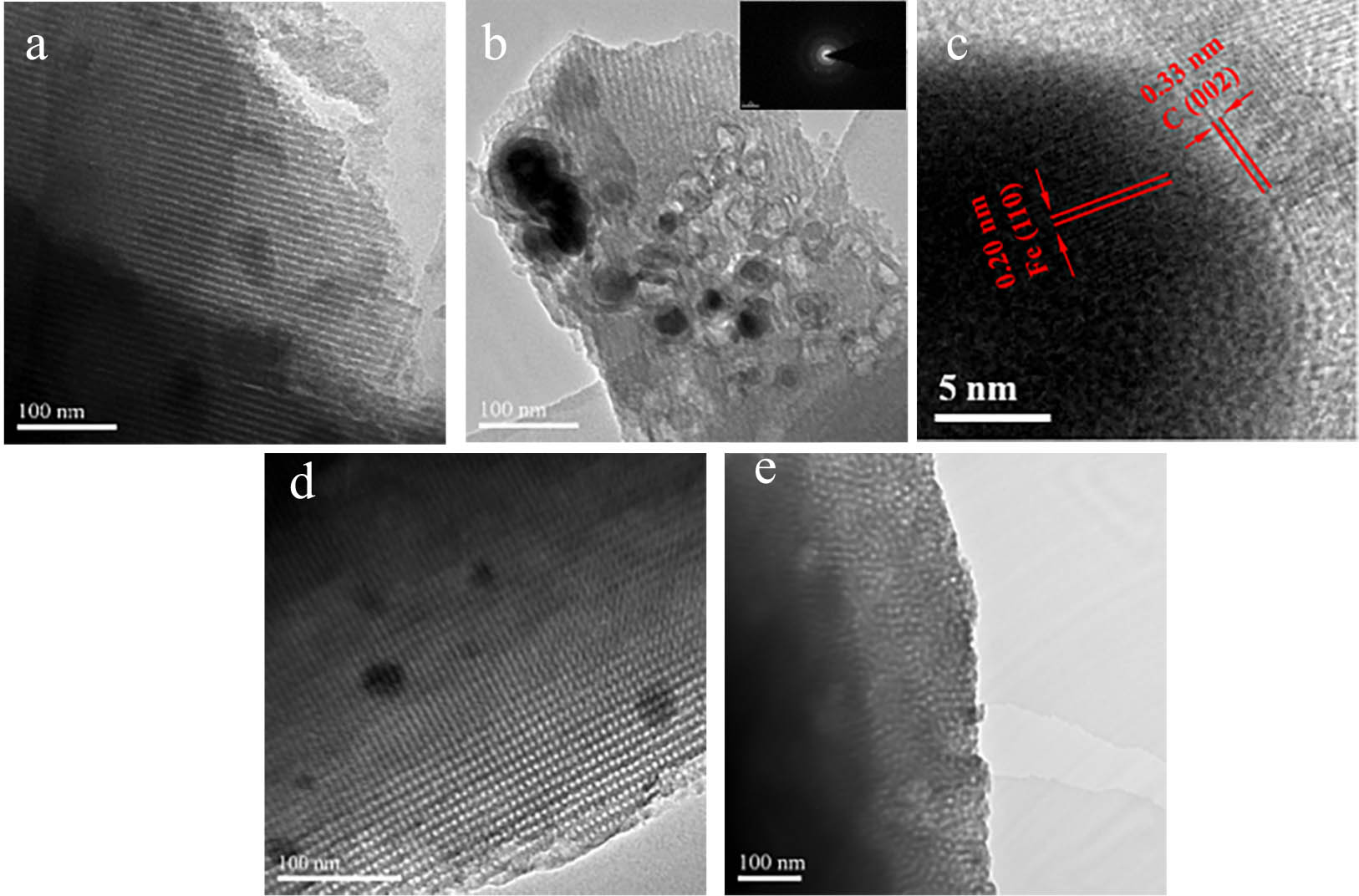

The TEM and HRTEM images of Fe0/OMC are shown in Figure 6. The pore structure of OMC-1 could be seen and the dark spots are uniformly embedded in the walls of the OMC (Figure 6(b)). Combining with the lattice stripes in Figure 6(c) and comparing the PDF cards, we could conclude that the black particles were Fe0. The HRTEM image of Fe0 nanoparticles embedded in the wall of OMC illustrated the perfect arrangements of atomic layers and lack of defects. And the lamellar structures on the surface were crystallized graphitic carbon. During the synthesis process, the pores of the ordered mesoporous carbon were partially destroyed, and the collapsed carbon skeleton was crystallized on the surface of the Fe0 to form a layer of graphitic carbon covering the surface of Fe0 nanoparticles.

TEM images of OMC-1 (a), Fe0/OMC-1 (b), and HRTEM images of Fe0/OMC-1 (c). TEM images of Fe0/OMC-2 (d) and Fe0/OMC-3 (e).

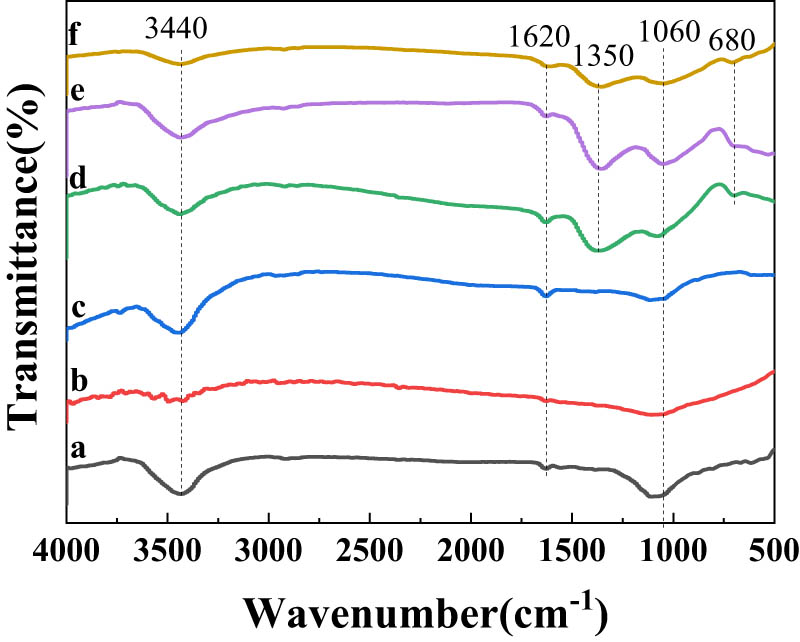

Fourier analyses of different OMC and Fe0/OMC were conducted, as depicted in Figure 7. The infrared spectra of the three OMC and Fe0/OMC exhibited comparable absorption peaks, indicating that the functional groups presented on their surfaces were similar. Furthermore, the presence of only a few functional groups on the surface can be attributed to the high-temperature calcination process carried out in an argon atmosphere. This suggests that Fe0/OMC exists as a pure carbon skeleton with the same composition as OMC, devoid of additional functional groups. The infrared spectra exhibited a prominent absorption peak between 3,300–3,600 cm−1, which corresponds to the stretching vibration of O–H bonds. This indicates the presence of a significant number of hydroxyl groups on the surface of the material [29]. Between 1,500 and 1,700 cm−1 was the stretching vibration peak of C═C. The peak near 1,350 cm−1 was Fe characteristic absorption peak [30]. The peak observed around 1,060 cm−1 can be attributed to the stretching vibration of the C–O bond. Additionally, the peak observed near 680 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of Fe–O bonds, indicating the presence of iron (Fe) in the Fe0/OMC material [31].

Fourier infrared spectrum of OMC-1 (a), OMC-2 (b), OMC-3 (c), Fe0/OMC-1 (d), Fe0/OMC-2 (e), and Fe0/OMC-3 (f).

3.3 Magnetic behavior of Fe0/OMC

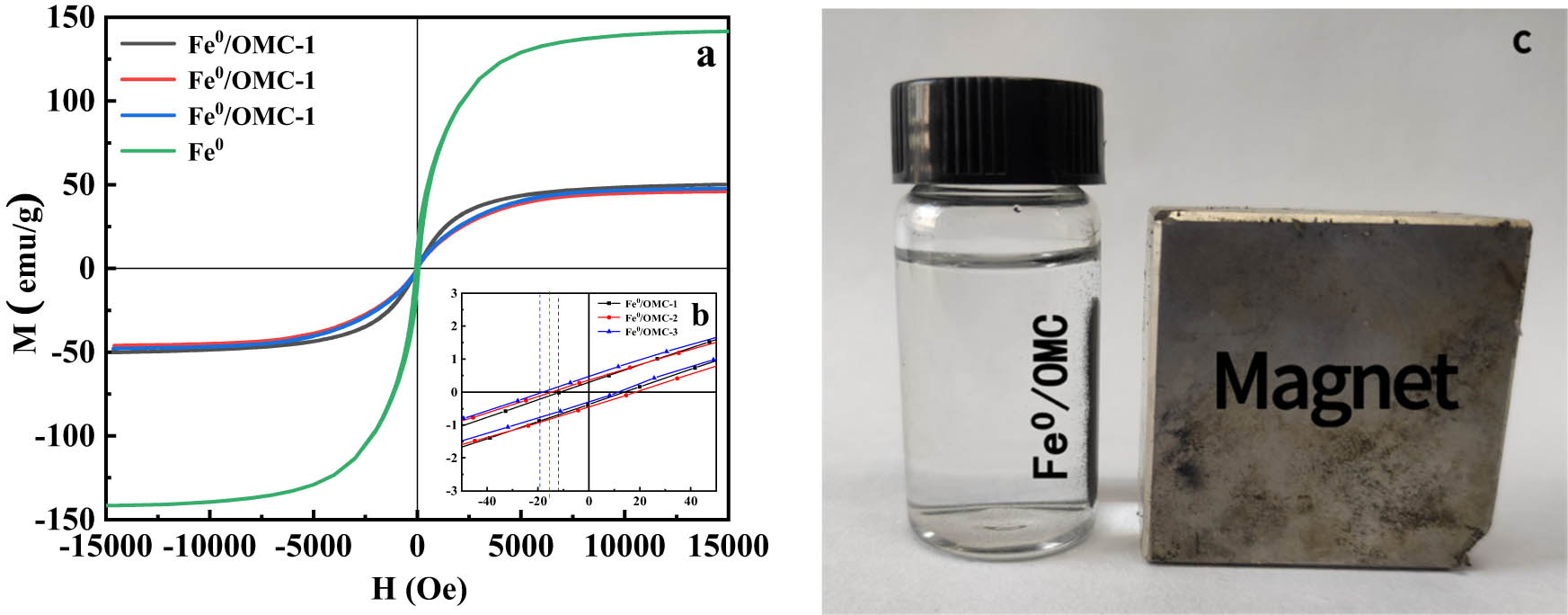

To study the magnetic properties of Fe0/OMC, a series of hysteresis lines were obtained by using the VSM to characterize the magnetic properties as shown in Figure 8, and the magnetic parameters are shown in Table 3. It was concluded that the hysteresis loops of all samples were S-shaped and the saturation magnetization of Fe0/OMC-1, Fe0/OMC-2, and Fe0/OMC-3 were 50.1, 45.8, and 47.7 emu·g−1, respectively, which were all significantly lower than that of Fe0 (142 emu·g−1). The presence of carbon and the smaller size of Fe0 nanoparticles can be attributed to the lower saturation magnetization observed in the Fe0/OMC material. The value of Mr/Ms was much less than 0.5, indicating the presence of uniaxial anisotropy in the growth of the magnetic particles. When Fe0/OMC particles were dispersed in a solution and exposed to a magnetic field, they exhibited complete separation from the solution, as depicted in the digital photograph of Fe0/OMC. This photograph serves as evidence that Fe0/OMC displays an excellent response to an external magnetic field.

Magnetic hysteresis loops of various Fe0/OMC and Fe0 (a) and local enlargement (b) and digital photographs of Fe0/OMC under external magnetic field (c).

Magnetic properties of Fe0/OMC and Fe0 composites

| Samples | Ms (emu·g−1) | Mr (emu·g−1) | Mr/Ms | Hc (Oe) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe0/OMC-1 | 50.1 | 0.35 | 0.007 | 15.0 |

| Fe0/OMC-2 | 45.8 | 0.29 | 0.006 | 11.1 |

| Fe0/OMC-3 | 47.7 | 0.33 | 0.007 | 12.2 |

| Fe0 | 143.3 | 9.66 | 0.067 | 70.06 |

3.4 Removal effects of Ag(i) upon Fe0/OMC

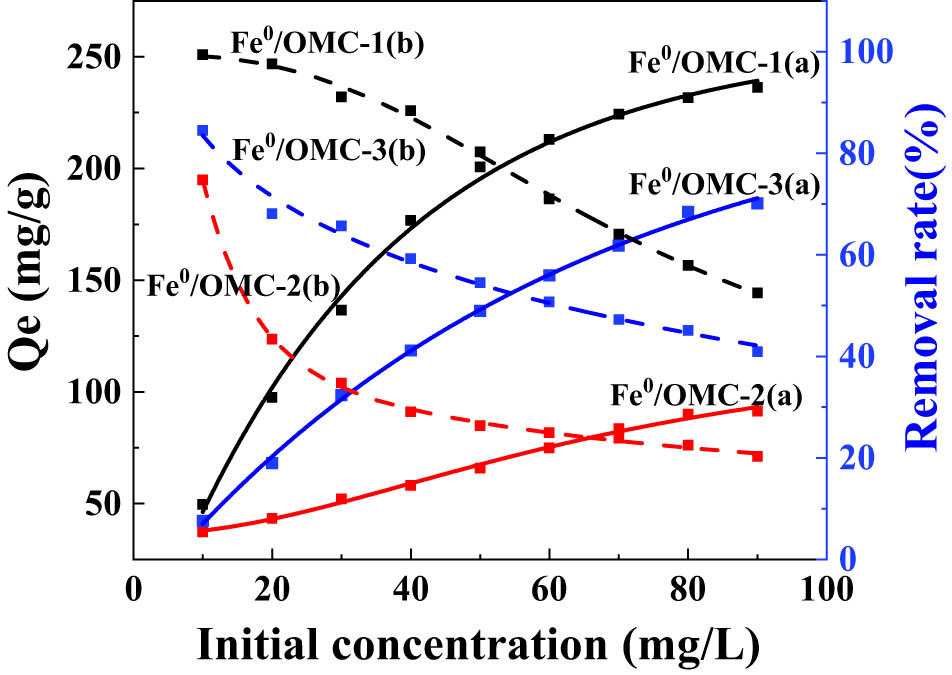

The impact of the initial concentration of Ag(i) on the adsorption performance of different Fe0/OMC materials was investigated, and the results are presented in Figure 9. It can be observed that the adsorption capacity of Fe0/OMC increased with the increase in the Ag(i) concentration and reached a nearly constant value at an initial Ag(i) concentration of 80 mg·L−1. Among the Fe0/OMC samples, Fe0/OMC-1 exhibited the highest adsorption capacity, reaching 233 mg·g−1. As the initial Ag(i) concentration increased, the adsorption process progressed, leading to the gradual occupation of active sites on the surface of Fe0/OMC. The superior adsorption capacity of Fe0/OMC-1 can be attributed to its larger specific surface area, which provides more adsorption active sites. Furthermore, the ordered p6mm pore structure of OMC-1 facilitates the entry of Ag(i) into the interior of the pores during the adsorption process, ensuring extensive contact between Ag(i) and the adsorption active sites on the pore surface.

Effect of initial concentrations on adsorption capacity of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC.

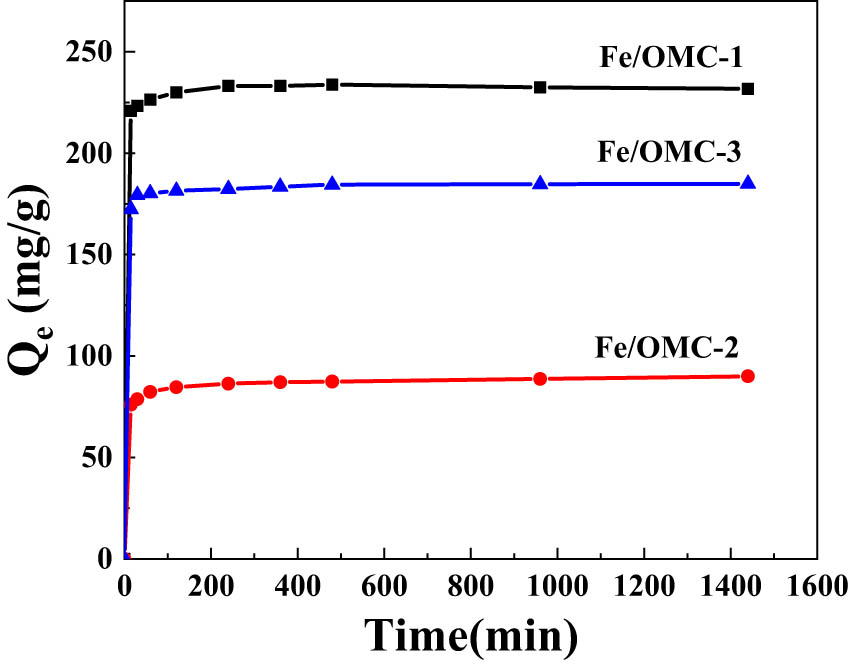

Figure 10 illustrates the impact of magnetic Fe0/OMC on the adsorption capacity of Ag(i) at different adsorption times, using an Ag(i) solution with an initial concentration of 80 mg·L−1. It can be observed that the removal rate of magnetic Fe0/OMC on Ag(i) is rapid within the first 30 min, with a sharp increase in adsorption capacity during this initial period. After 30 min, the adsorption rate gradually slows down. At an adsorption time of 2 h, the adsorption of magnetic Fe0/OMC on Ag(i) reaches a dynamic equilibrium, and the adsorption capacity also reaches its maximum.

Effects of adsorption times on adsorption capacity of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC.

Throughout the adsorption process, the adsorption rate is remarkably fast, and the adsorption capacity exhibits significant growth within the first 30 min. This can be attributed to the abundant adsorption active sites on the surface of the material and the high concentration of Ag(i) in the solution. As the adsorption experiment progresses, the adsorption active sites provided by Fe0/OMC gradually become saturated, leading to a decrease in the adsorption rate of Ag(i). The adsorption capacity tends to level off as the adsorption of Ag(i) reaches its maximum content, signifying the attainment of dynamic equilibrium in the entire adsorption process.

In addition, Table 4 shows the comparison of the adsorption capacity of different adsorbents for Ag(i), and it can be seen that Fe0/OMC-1 has better adsorption performance.

Comparison of adsorption capacity of different adsorbents for Ag(i)

| Adsorbents | Adsorption capacity (mg·g−1) | Initial concentration of Ag(i) (mg·L−1) | Time (min) | Ref. | Adsorbent content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe0/OMC-1 | 233 | 80 | 120 | [Our work] | 0.2 g·L−1 |

| MnO2 nanotubes@reduced graphene oxide hydrogel (MNGH) | 138.2 | 200 | 720 | [3] | 0.2 g·L−1 |

| TU-PVDF | 171 | 107 | 560 | [7] | 0.1 g |

| Fruit shell-derived (SPCs) | 115 | 100 | 480 | [10] | 0.2 g·L−1 |

| Recycled supercapacitor activated carbon | 104.2 | 2000 | 1440 | [22] | 2 g·L−1 |

| CNS/OH0.5 | 152 | 1,080 | 360 | [33] | 1 g·L−1 |

| TPCFMA | 124.3 | 400 | 720 | [43] | 2 g·L−1 |

3.5 Adsorption kinetics

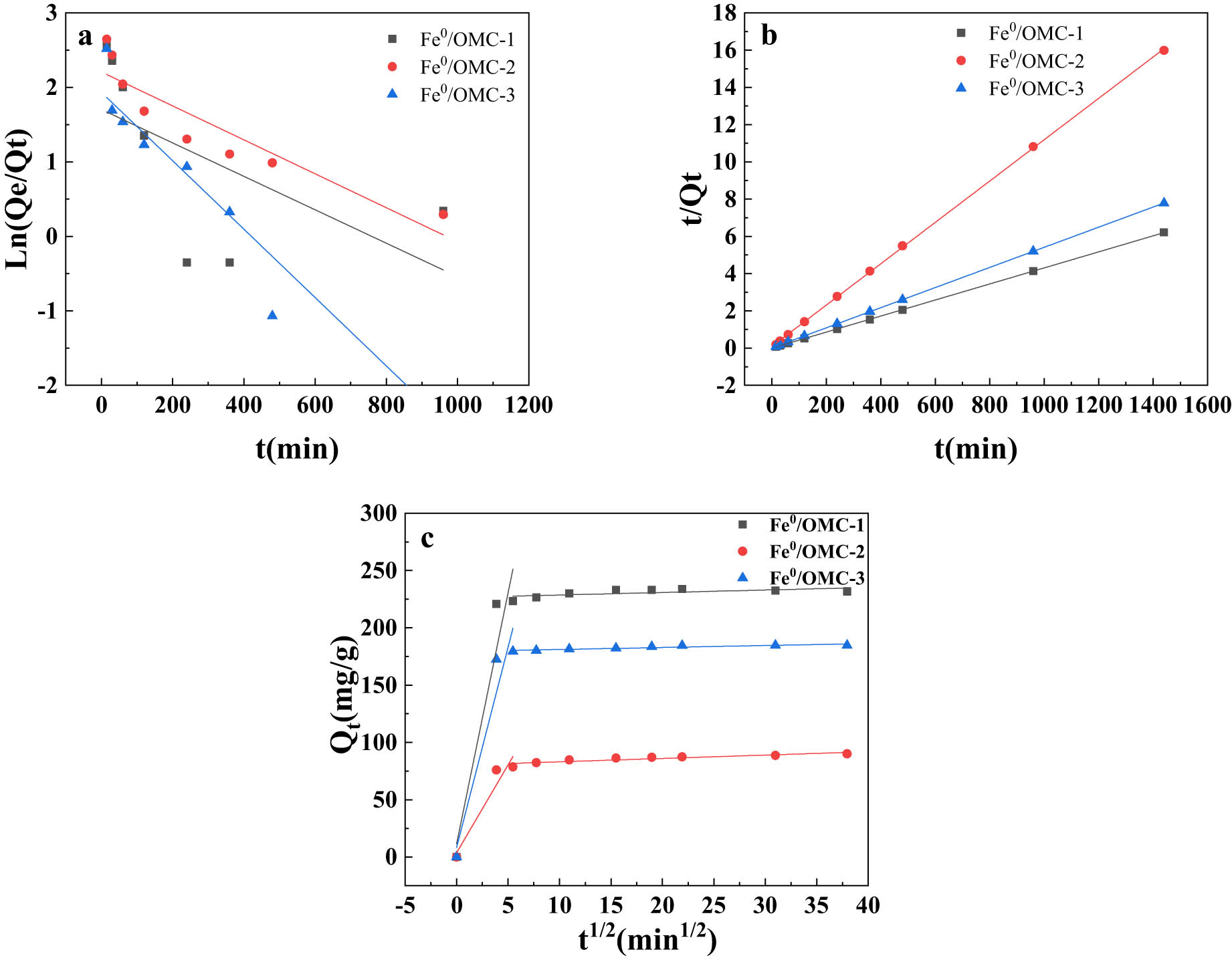

The adsorption kinetics of Ag(i) adsorption by Fe0/OMC was investigated to explore the adsorption behavior of Ag(i) in the adsorbent. The adsorption data were analyzed using three kinetic models: the pseudo-first-order model, the pseudo-second-order model, and the intraparticle diffusion model.

Pseudo-first-order model: assuming that the adsorption process was controlled by the diffusion step, the kinetic expression is shown in Eq. (3) [32].

The pseudo-second-order model is based on the assumption that the rate of adsorption is controlled by electron sharing and electron transfer between Fe0/OMC and Ag(i). This process involved the transfer and sharing of electrons between the adsorbent and the adsorbate. The kinetic expression for the pseudo-second-order model is shown in the Eq. (4) [33].

Based on the results of the kinetic analysis, an intraparticle diffusion model was employed to investigate the diffusion mechanism of Ag(i) and to identify the rate-limiting step in the adsorption process. The equation for the intraparticle diffusion model is expressed as follows [34]:

where k 1 (min−1), k 2 (g·(mg·min)−1), and k i (mg·(g−1·min−0.5)) represent the rate constants for the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intraparticle diffusion models, respectively. Q t (mg·g−1) refers to the adsorption capacity at time t, while Q e1 (mg·g−1) and Q e2 (mg·g−1) denote the adsorption capacities of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC; C (mg·g−1) represents the intercept obtained from the curve derived using the intraparticle diffusion model.

Figure 11 displays the kinetic curves obtained by fitting the data from the adsorption experiments. Figure 11(a) and (b) represent the simulations of the pseudo-first-order model and the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, respectively. The comparison presented in Table 4 indicates that the pseudo-second-order kinetic model exhibits a higher R2 value, suggesting that the adsorption of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC is in agreement with the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. These results suggest that the adsorption process involves electron sharing and electron transfer.

Experimental data fitted using (a) quasi-first order, (b) quasi-second order and (c) intraparticle diffusion models for adsorption of Ag(i) by Fe0/OMC.

The curves obtained by fitting the intraparticle diffusion model are shown in Figure 11(c), revealing two stages within the overall adsorption process: the surface diffusion stage and the intraparticle diffusion stage. The complete diffusion process of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC primarily involves physical and chemical adsorption, with intraparticle diffusion serving as the rate-controlling step.

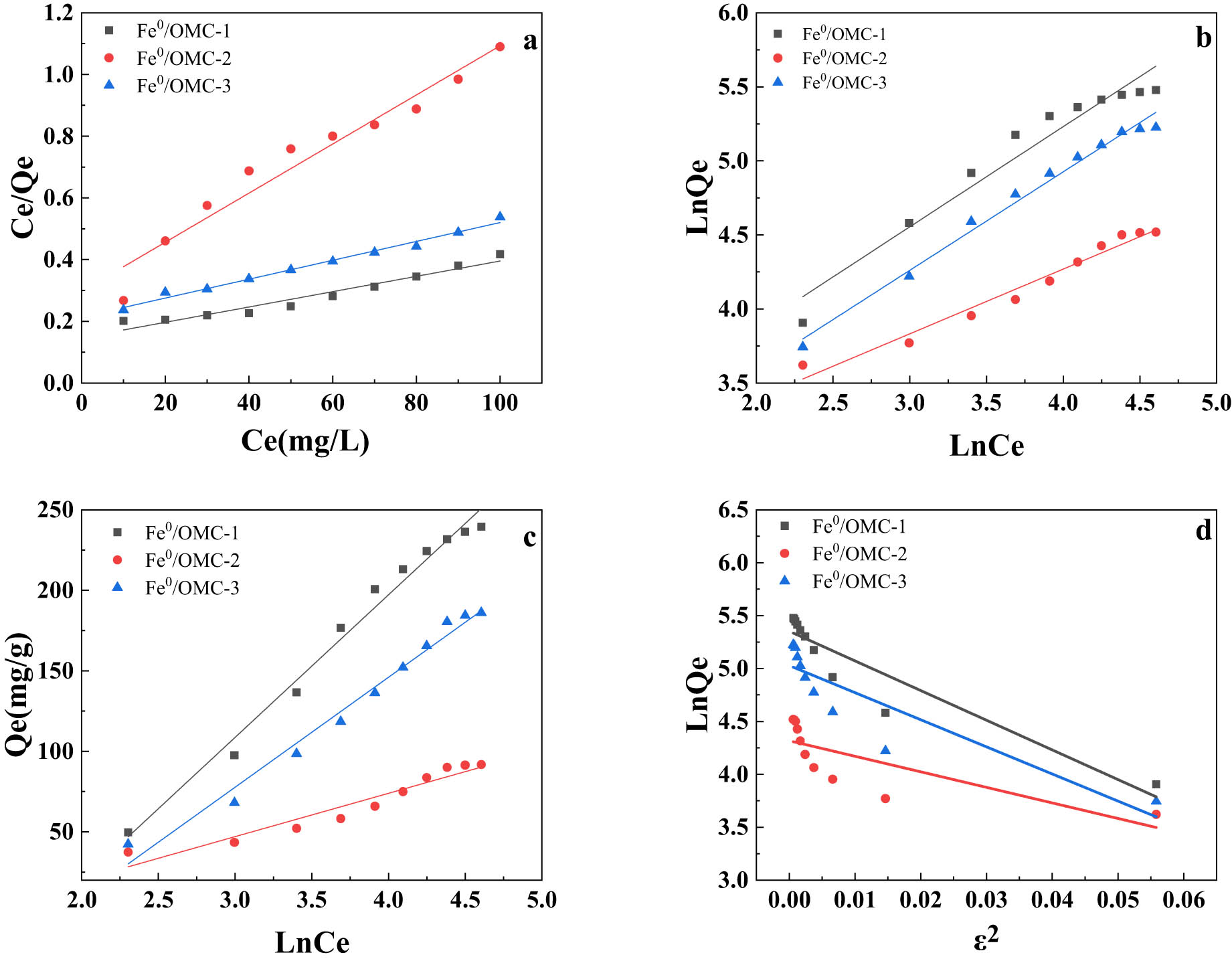

3.6 Adsorption isotherms

The isothermal adsorption process could describe the interaction between Fe0/OMC and Ag(i). Four isothermal adsorption models, Langmuir [35], Freundlich [36], Temkin [37], and Dubinin-Radushkevich [38], were used to fit the experimental results, respectively. The related expressions were as follows:

Langmuir:

Freundlich:

Temkin:

Dubinin-Radushkevich:

where C e (mg·L−1) represents the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate and Q e (mg·g−1) represents the equilibrium adsorption capacity; Q m (mg·g−1) refers to the maximum adsorption capacity of the adsorbent. K L, K F, and K T are equilibrium constants associated with the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models, respectively. The value of R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J·(mol·K)−1), and T represents the reaction temperature.

The experimental data obtained from the Ag(i) adsorption experiments on Fe0/OMC were fitted using four isothermal adsorption models: Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin-Radushkevich. The results of the fitting are presented in Figure 12, and the fitted parameters are listed in Table 5. Among the four models, the Freundlich isothermal adsorption model provides a better simulation of the adsorption data. This suggests that the adsorption process involves multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface (Table 6).

Adsorption of Ag(i) Fe0/OMC (a) Langmuir isotherm adsorption model, (b) Freundlich isotherm adsorption model, (c) Temkin isotherm adsorption model, and (d) Dubinin-Radushkevich isotherm adsorption model.

Parameters of adsorption kinetics model for adsorption of Ag(i) by Fe0/OMC

| Models | Parameters | Fe0/OMC-1 | Fe0/OMC-2 | Fe0/OMC-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order |

|

0.36093 | 0.84707 | 0.92245 |

| K 1 (min−1) | 0.0969 | 0.0740 | 0.0926 | |

| Q e (exp) (mg·g−1) | 233 | 90 | 185 | |

| Q e (cal) (mg·g−1) | 229 | 84 | 182 | |

| Equation | ln(Q e − Q t ) = 1.7037 – 0.00224t | ln(Q e − Q t ) = 2.2072 – 0.00228t | ln(Qe − Q t ) = 1.9333 – 0.00459t | |

| Pseudo-second-order |

|

0.9999 | 0.9998 | 1 |

| Q e (exp) (mg·g−1) | 233 | 90 | 185 | |

| Q e (cal) (mg·g−1) | 232 | 90 | 185 | |

| K 2 (g·(mg·min)−1) | 0.0478 | 0.00136 | 0.00272 | |

| Equation | t/Q t = 0.00431t + 0.000389 | t/Q t = 0.0111t + 0.09024 | t/Q t = 0.0054t + 0.0107 | |

| Intraparticle diffusion |

|

0.9993 | 0.9999 | 0.7415 |

|

|

0.2639 | 0.9008 | 0.8190 | |

| k i1 (mg·(g−1·min−0.5)) | 1.451 | 1.645 | 1.895 | |

| k i2 (mg·(g−1·min−0.5)) | 0.122 | 0.225 | 0.152 | |

| Equation i1 | Q t = 1.451t 1/2 + 215.277 | Q t = 1.645t 1/2 + 69.619 | Q t = 1.895t 1/2 + 166.564 | |

| Equation i2 | Q t = 0.122t 1/2 + 229.040 | Q t = 0.225t 1/2 + 82.043 | Q t = 0.152t 1/2 + 179.950 |

Adsorption isotherm model parameters for adsorption of Ag(i) on Fe0/OMC

| Models | Constants | Fe0/OMC-1 | Fe0/OMC-2 | Fe0/OMC-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | Q max (mg·g−1) | 403 | 125 | 326 |

| K L (L·mg−1) | 0.0000418 | 0.000213 | 0.0000438 | |

| R 2 | 0.94941 | 0.95148 | 0.98723 | |

| Equation | C e/Q e = 0.147 + 0.00248C e | C e/Q e = 0.297 + 0.00795C e | C e/Q e = 0.214 + 0.00306C e | |

| Freundlich | K F (mg·g−1) | 12.503 | 12.441 | 9.641 |

| N (mg·L−1) | 1.479 | 2.288 | 1.504 | |

| R 2 | 0.94653 | 0.96914 | 0.98727 | |

| Equation | ln Q e = 2.526 + 0.676 ln C e | ln Q e = 2.521 + 0.437 ln C e | ln Q e = 2.266 + 0.665 ln C e | |

| Temkin | K T (L·g−1) | 0.170 | 0.286 | 0.155 |

| B (J·mol−1) | 27.987 | 92.135 | 36.296 | |

| R 2 | 0.98453 | 0.9263 | 0.98136 | |

| Equation | Q e = 88.571 ln C e – 157.055 | Q e = 26.904 ln C e – 33.694 | Q e = 68.294 ln C e – 127.184 | |

| Dubinin-Radushkevich | Q max (mg·g−1) | 211 | 75 | 152 |

| B (mol2·kJ−2) | 28.486 | 14.698 | 25.626 | |

| E (kJ·mol−1) | 0.132 | 0.184 | 0.140 | |

| R 2 | 0.8812 | 0.59291 | 0.79348 | |

| Equation | ln Q e = 5.352 – 28.486ε 2 | ln Q e = 4.318 − 14.698ε 2 | ln Q e = 5.028 − 25.626ε 2 |

3.7 Adsorption mechanism

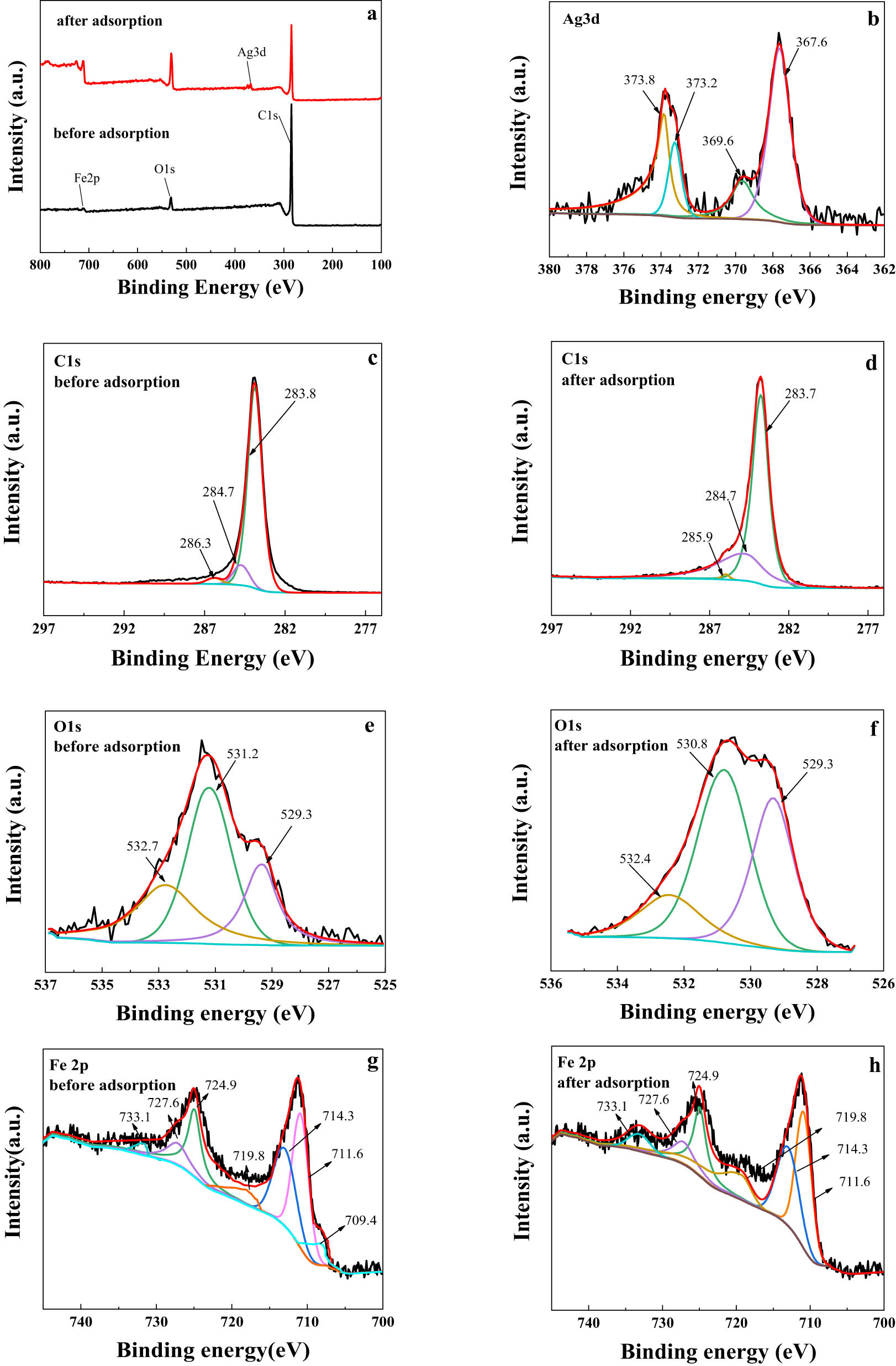

To further understand the adsorption mechanism of Ag(i) from solution by magnetic Fe0/OMC-1, the chemical compositions of the material before and after adsorption of Ag(i) by Fe0/OMC-1 were characterized by XPS. Figure 13(a) shows a full scan of Fe/OMC-1 before and after adsorption. The spectrum of the Ag(i)-adsorbed material (Figure 13(b)) reveals an additional Ag 3d peak, corroborating the existence of elemental Ag on Fe0/OMC. XPS spectrum of the regions for C 1s, O 1s, and Fe 2p of the Fe0/OMC before and after adsorption of Ag(I) are shown in Figure 13(c–h).

XPS spectra of (a) Fe0/OMC-1 before and after adsorption of Ag(i). High resolution spectra of (b) Ag 3d after adsorption of Ag(i). High resolution spectra of (c and d) C 1 s, (e and f) O 1s and (g and h) Fe 2p for Fe0/OMC-1 before and after adsorption of Ag(i).

A high-resolution scan of Ag(I) adsorbed Fe/OMC shows two large characteristic peaks of Ag 3d as shown in Figure 13(b). By splitting and fitting the characteristic peaks, two characteristic peaks of 369.6 and 373.2 eV representing Ag(i) and two characteristic peaks of 367.6 and 373.8 eV representing Ag singlet could finally be obtained. This result shows the co-existence of Ag(i) and Ag after adsorption. After adsorption, Ag(i) and Ag accounted for 38% and 62% of the Ag in Fe0/OMC-1, respectively, indicating that Ag(i) was partially reduced through redox adsorption of Fe0/OMC. The C 1s spectra (Figure 13(c) and (d)) for the material before and after adsorption of Ag(i) showed little change, indicating that the features of the skeleton of Fe/OMC are very stable. As shown in Figure 13(e), the O 1s peaks can be decomposed into four components originating from –OH (around 531.2 eV), O2‒ (around 529.3 eV), and O–O═C (around 532.7 eV). The O2‒ at 529.3 eV (Figure 13(f)) belonged to the Fe–O in the Fe0/OMC-1 that was oxidized to Fe3O4 characteristic peaks [39,40]. Figure 13(g) and (h) shows the high-resolution spectra of Fe 2p. Before adsorption, 709.4 eV corresponds to the characteristic peak of Fe0 [41]; 711.6, 724.9 and 727.6 eV can be attributed to the Fe2+; 714.3, 719.8, and 733.1 eV correspond to the characteristic peaks of Fe3+ [42]. After adsorption, the characteristic peak area of Fe0 decreased while the characteristic peak area of Fe3+ increased, which was due to the partial involvement of Fe0 in the redox reaction to generate iron oxides during the adsorption process, while reducing Ag(i) to Ag. The above results indicated that the magnetic Fe/OMC-1 has undergone not only physical adsorption but also redox reactions during the adsorption of Ag(i).

4 Conclusion

The successful synthesis of three OMC materials with different structures was achieved using a soft-template induction method. These materials were then loaded with Fe0 through impregnation and carbon thermal in situ reduction method. The specific surface area and pore volume of the Fe0/OMC decreased after Fe loading, but the presence of Fe resulted in increased Fe-containing chemical bonding adsorption active sites on the material surface. These functional groups were found to be beneficial for the adsorption capacity of the materials.

The adsorption process of Ag(i) by the Fe0/OMC-1 composite was well-described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and Freundlich isotherm adsorption model. This suggests that the adsorption of Ag(i) occurred through a multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface, and the presence of Fe0 exhibited a synergistic effect on the adsorption of Ag(i). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis supported this mechanism by revealing that the adsorption of Ag(i) by Fe0/OMC involved both physical adsorption through active sites on the material surface and a redox reaction facilitated by the loaded Fe0. Ultimately, Ag(i) was adsorbed onto the surface of Fe0/OMC in the form of Ag(i) and Ag species.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Major Science and Technology Project of Gansu Province (22ZD6GA008) for paying the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Major Science and Technology Project of Gansu Province (Grant No.22ZD6GA008); National Natural Science Foundation of China (51703088 and 52262013); Key laboratory of polymer materials opening fund project in 2018 (KF-18-03); Hongliu youth fund of Lanzhou university of technology (061805); Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (21JR7RA259); Gansu Province for young doctor (2021QB-048). We thank State Key Laboratory for Advanced Processing and Recycling of Non-ferrous Metals in Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, Gansu Province.

-

Author contributions: Wenjuan Zhang: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, and supervision. Yuheng Li: writing – original draft and formal analysis. Mengyu Ran: validation and data curation. Youliang Wang: supervision. Yezhi Ding: writing – review and editing. Bobo Zhang: data curation. Qiancheng Feng: validation. Qianqian Chu: funding acquisition. Yongqian Shen: supervision. Wang Sheng: supervision and data curation. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Simona, S., E. Abdelhamid, M. Rita, and J. R. Nicole. Aptamers functionalized metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: Recent advances in heavy metal monitoring. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 157, 2022, id. 116748.10.1016/j.trac.2022.116748Suche in Google Scholar

[2] El Bahgy, H. E. K., H. Elabd, and R. M. Elkorashey. Heavy metals bioaccumulation in marine cultured fish and its probabilistic health hazard. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, Vol. 28, 2021, pp. 41431–41438.10.1007/s11356-021-13645-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Zeng, T., Y. Yu, Z. Li, J. Zuo, Z. Kuai, Y. Jin, et al. 3D MnO2 nanotubes@reduced graphene oxide hydrogel as reusable adsorbent for the removal of heavy metal ions. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 231, 2019, pp. 105–108.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.04.019Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Zhuo, X., M. Henriksen-Lacey, D. Jimenez de Aberasturi, A. Sánchez-Iglesias, and L. M. Liz-Marzán. Shielded silver nanorods for bioapplications. Chemistry of Materials, Vol. 32, No. 13, 2020, pp. 5879–5889.10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c01995Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Tortella, G. R., O. Rubilar, N. Durán, M. C. Diez, M. Martínez, J. Parada, et al. Silver nanoparticles: Toxicity in model organisms as an overview of its hazard for human health and the environment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 390, 2020, id. 121974.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121974Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Liu, X. and Y. Wang. Activated carbon supported nanoscale zero-valent iron composite: Aspects of surface structure and composition. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 222, 2019, pp. 369–376.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.10.013Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Liu, P., X. Wang, L. Tian, B. He, X. Lv, X. Li, et al. Adsorption of silver ion from the aqueous solution using a polyvinylidene fluoride functional membrane bearing thiourea groups. Journal of Water Process Engineering, Vol. 34, 2020, id. 101184.10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101184Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Herman, P., D. Pércsi, T. Fodor, L. Juhász, Z. Dudás, Z. E. Horváth, et al. Selective and high capacity recovery of aqueous Ag(i) by thiol functionalized mesoporous silica sorbent. Journal of Molecular Liquids, Vol. 387, No. 1, 2023, id. 122598.10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122598Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Al-Anber, M. A., M. Al Ja’afreh, I. F. Al-Momani, A. K. Hijazi, D. Sobola, S. Sagadevan, et al. Loading of silver(i) ion in L-cysteine-functionalized silica gel material for aquatic purification. Gels, Vol. 9, No. 11, 2023, id. 865.10.3390/gels9110865Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Fan, J., L. Duan, X. Zhang, Z. Li, P. Qiu, Y. He, et al. Selective adsorption and recovery of silver from acidic solution using biomass-derived sulfur-doped porous carbon. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, Vol. 15, 2023, pp. 40088–40099.10.1021/acsami.3c07887Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Mu, Y., Z. Ai, and L. Zhang. Phosphate shifted oxygen reduction pathway on Fe@Fe2O3 core-shell nanowires for enhanced reactive oxygen species generation and aerobic 4-chlorophenol degradation. Environmental Science and Technology, Vol. 51, No. 14, 2017, pp. 8101–8109.10.1021/acs.est.7b01896Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Bae, S., R. N. Collins, T. D. Waite, and K. Hanna. Advances in surface passivation of nanoscale zerovalent iron (NZVI): A critical review. Environmental Science and Technology, Vol. 52, No. 21, 2018, pp. 12010–12025.10.1021/acs.est.8b01734Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Dai, Y., Y. Hu, B. Jiang, J. Zou, G. Tian, and H. Fu. Carbothermal synthesis of ordered mesoporous carbon-supported nano zero-valent iron with enhanced stability and activity for hexavalent chromium reduction. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 309, 2016, pp. 249–258.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.04.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Wang, J., G. Liu, C. Zhou, T. Li, and J. Liu. Synthesis, characterization and aging study of kaolinite-supported zero-valent iron nanoparticles and its application for Ni(ii) adsorption. Materials Research Bulletin, Vol. 60, 2014, pp. 421–432.10.1016/j.materresbull.2014.09.016Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Okonji, S. O., G. Achari, and D. Pernitsky. Removal of organoselenium from aqueous solution by nanoscale zerovalent iron supported on granular activated carbon. Water, Vol. 14, No. 6, 2022, id. 987.10.3390/w14060987Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Guo, Y., Y. Zhao, T. Yang, B. Gong, and B. Chen. Highly efficient nano-Fe/Cu bimetal-loaded mesoporous silica Fe/Cu-MCM-41 for the removal of Cr(VI): Kinetics, mechanism and performance. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 418, 2021, id. 126344.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126344Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Liu, Z., F. Zhang, S. K. Hoekman, T. Liu, C. Gai, and N. Peng. Homogeneously dispersed zerovalent iron nanoparticles supported on hydrochar-derived porous carbon: Simple, in situ synthesis and use for dechlorination of PCBs. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Vol. 4, No. 6, 2016, pp. 3261–3267.10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00306Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Teng, W., J. Fan, W. Wang, N. Bai, R. Liu, Y. Liu, et al. Nanoscale zero-valent iron in mesoporous carbon (nZVI@C): stable nanoparticles for metal extraction and catalysis. Journal of Materials Chemistry A: Materials for Energy and Sustainability, Vol. 5, 2017, pp. 4478–4485.10.1039/C6TA10007DSuche in Google Scholar

[19] Sun, X., J. Fang, R. Xu, M. Wang, H. Yang, Z. Han, et al. Nanoscale zero-valent iron immobilized inside the mesopores of ordered mesoporous carbon by the “two solvents” reduction technique for Cr(VI) and As(V) removal from aqueous solution. Journal of Molecular Liquids, Vol. 315, 2020, id. 113598.10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113598Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Lin, Y. and J. Chen. Magnetic mesoporous Fe/carbon aerogel structures with enhanced arsenic removal efficiency. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Vol. 420, 2014, pp. 74–79.10.1016/j.jcis.2014.01.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Yuan, P., J. Liu, Y. Li, Y. Fan, G. Shi, H. Liu, et al. Effect of pore diameter and structure of mesoporous sieve supported catalysts on hydrodesulfurization performance. Chemical Engineering Science, Vol. 111, 2014, pp. 381–389.10.1016/j.ces.2014.03.006Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Wu, F., T. Zhao, Y. Yao, T. Jiang, B. Wang, and M. Wang. Recycling supercapacitor activated carbons for adsorption of silver(i) and chromium (VI) ions from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere, Vol. 238, 2020, id. 124638.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124638Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Du, Y., T. Liu, B. Yu, H. Gao, P. Xu, J. Wang, et al. The electromagnetic properties and microwave absorption of mesoporous carbon. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Vol. 135, 2012, pp. 884–891.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.05.074Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Liu, S. and S. C. Chen. Stepwise synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical properties of ordered mesoporous carbons containing well-dispersed Pt nanoparticles using a functionalized template route. Journal of Solid State Chemistry, Vol. 184, No. 9, 2011, pp. 2420–2427.10.1016/j.jssc.2011.07.016Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Li, K., Y. Zhou, J. Li, and J. Liu. Soft-templating synthesis of partially graphitic Fe-embedded ordered mesoporous carbon with rich micropores from bayberry kernel and its adsorption for Pb(ii) and Cr(iii). Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, Vol. 82, 2018, pp. 312–321.10.1016/j.jtice.2017.10.036Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Wei, J., Z. Sun, W. Luo, Y. Li, A. A. Elzatahry, A. M. Al-Enizi, et al. New insight into the synthesis of large-pore ordered mesoporous materials. Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 139, No. 5, 2017, pp. 1706–1713.10.1021/jacs.6b11411Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Meng, Y., D. Gu, F. Zhang, Y. Shi, H. Yang, Z. Li, et al. Ordered mesoporous polymers and homologous carbon frameworks: Amphiphilic surfactant templating and direct transformation. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, Vol. 44, 2005, pp. 7053–7059.10.1002/anie.200501561Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Deng, Y., T. Yu, Y. Wan, Y. Shi, Y. Meng, D. Gu, et al. Ordered mesoporous silicas and carbons with large accessible pores templated from amphiphilic deblock copolymer poly(ethylene oxide)-b-polystyrene. Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 129, 2007, pp. 1690–1697.10.1021/ja067379vSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Kim, Y. J., M. I. Kim, C. H. Yun, J. Y. Chang, C. R. Park, and M. J. Inagaki. Comparative study of carbon dioxide and nitrogen atmospheric effects on the chemical structure changes during pyrolysis of phenol–formaldehyde spheres. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Vol. 274, No. 2, 2004, pp. 555–562.10.1016/j.jcis.2003.12.029Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Qian, L., X. Shang, B. Zhang, W. Zhang, A. Su, Y. Chen, et al. Enhanced removal of Cr(vi) by silicon rich biochar-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron. Chemosphere, Vol. 215, 2019, pp. 739–745.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.030Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Jiaman, L. I., D. A. I. Yexin, L. I. Yuwei, L. I. U. Fang, Z. H. A. O. Chaocheng, and W. A. N. G. Yongqiang. Adsorption of p-Nitrophenol from aqueous solution by mesoporous carbon and its Fe-modified materials. Acta Petrolei Sinica (Petroleum Processing Section), Vol. 35, No. 1, 2019, pp. 136–145.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Ho, Y. S. and G. McKay. The sorption of lead(ii) ions on peat. Water Research, Vol. 33, No. 2, 1999, pp. 580–584.10.1016/S0043-1354(98)00207-3Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Song, X., P. Gunawan, R. Jiang, S. S. J. Leong, K. Wang, and R. Xu. Surface activated carbon nanospheres for fast adsorption of silver ions from aqueous solutions. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 194, 2011, pp. 162–168.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.07.076Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Weber, W. J. Jr and J. C. Morris. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. Journal of the Sanitary Engineering Division, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1963, pp. 1–2.10.1061/JSEDAI.0000430Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Langmuir, I. Vapor pressures, evaporation, condensation and adsorption. Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 68, No. 6, 1932, pp. 370–373.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Freundlich, H. Over the adsorption in solution. Journal of Physical Chemistry, Vol. 57, 1906, pp. 385–471.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Roginsky, S. Z. and Y. B. Zeldovich. Die katalische oxidation von kohlenmonoxyd auf mangandioxyd. Acta Physiochimica URSS, Vol. 1, 1934, pp. 554–594.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Dubinin, M. M. and L. V. Radushkevich. Equation of the characteristic curve of the activated charcoal. Chemisches Zentralblatt, Vol. 1, 1947, pp. 875–890.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Zhang, Y. Preparation of polymer coated magnetic nanomaterials and their application for adsorption and separation. Dissertation. Ludong University, Shandong, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Blum, R., S. Reiche, and X. C. Zhao. Reactivity of mesoporous carbon against water – an in-situ XPS study. Carbon, Vol. 77, 2014, pp. 175–183.10.1016/j.carbon.2014.05.019Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Sun, Y. P., X. Q. Li, J. Cao, W. X. Zhang, and H. P. Wang. Characterization of zero-valent iron nanoparticles. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, Vol. 120, No. 1–3, 2006, pp. 47–56.10.1016/j.cis.2006.03.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Wang, X. Study on nanoscale zero-valent iron and its modified bimetallic Pd/Fe materials in nitrate reduction. Dissertation. Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing, 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Zhao, W., Y. Huang, R. Chen, H. Peng, Y. Liao, and Q. Wang. Facile preparation of thioether/hydroxyl functionalized polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes hybrid polymer for ultrahigh selective adsorption of silver(i) ions. Reactive & Functional Polymers, Vol. 163, 2021, id. 104899.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2021.104899Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension