Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a serious damage to the spinal cord that can lead to life-long disability. It is classified by initial trauma and subsequent neuronal degeneration, marked by permanent impairment of brain function across the whole brain. This condition results in a progressive deterioration of cognitive function in patients and is frequently associated with psychological symptoms such as body’s movement (paralysis and autonomic dysreflexia), imposing a significant burden on both patients and their families. Nanomaterials such as antioxidant quantum dots (QDs) are an innovative approach, providing dual functionality in theranostics – concurrent therapeutic and diagnostic capacities in the biomedical domain, which can be utilized for disease prevention and therapy. This review thoroughly examines the potential of QDs to transform SCI care due to their inherent antioxidant characteristics, nanoscale accuracy, and capacity to reduce damage caused by reactive oxygen species. It underscores their function in safeguarding brain tissue, augmenting the viability and development of transplanted stem cells, and facilitating axonal regeneration. Moreover, their versatile use in imaging and real-time assessment of treatment results highlights their transformational potential. This study is significant as it connects developing nanotechnology with regenerative medicine for SCI, providing a comprehensive overview of present advances, problems, and future prospects. It examines pivotal concerns such QD toxicity, biocompatibility, and regulatory challenges, while investigating methods for enhancing formulations and incorporating QDs with combination medicines. This review offers a pathway for enhancing QD applications in neuroprotection and regeneration, with the intention of fostering multidisciplinary research and expediting clinical translation, so facilitating new therapies for SCI that enhance patient outcomes and quality of life.

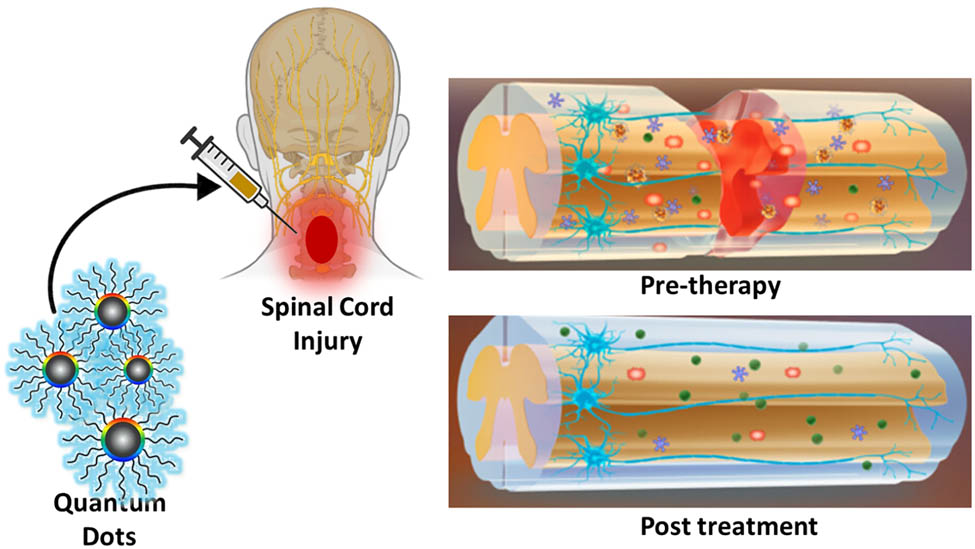

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a serious damage to the spinal cord that can lead to lifelong disability. The spinal cord is an intricate system of connections that transmits information and directives between the brain and the body. Numerous, different physiological routes inside the spinal cord facilitate the transfer of specialized information [1]. The corticospinal tract transmits motor function information, whereas the spinothalamic tract and posterior columns serve as the principal corporeal routes [2]. The posterior columns convey vibration, fine touch, and proprioception, while the spinothalamic tracts convey pain, warmth, and harsh trace. From the medulla oblongata, the spinal cord narrows to produce the conus medullaris, usually at vertebral level L2 [3,4,5]. The spinal cord is safeguarded by the meninges and the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebrae [6]. The spinal cord has one anterior and two posterior spinal arteries, as well as radicular arteries located throughout the cord, including the artery of Adamkiewicz, which supplies the inferior two-thirds [7]. The venous drainage of the spinal cord occurs through a complicated system of valveless venous plexuses [8]. SCIs are classified into two categories: traumatic SCI (TSCI) and nontraumatic SCI. TSCIs result from a quick impact on the spine that causes cracks and dislocation of vertebrae. Traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) affects normal sensory, motor, and autonomic functioning, impacting a patient’s physical, psychological, and social wellbeing [9,10]. The management of SCI necessitates considerable healthcare resources and can impose a huge financial strain on patients, their families, and the society [11]. These costs are largely due to short-term intensive care and long-term subaltern concerns [12]. To enhance injury management, it is essential to measure the incidence and preponderance of SCIs to better comprehend occurrence rates and identify prevention strategies [13]. A growing concern is the cost-effective effects of SCI on healthcare workers and the system. Krueger et al. estimated that the lifetime economic load of SCI in Canada ranges from CAD$1.47 million for inadequate disability to CAD$3.03 million for total tetraplegia. Wound contaminations, displaced equipment, alternative readmissions, and long-term complications such as pressure ulcers, bladder and bowel dysfunction, neuropathic pain, and respirational disorders are included in these estimates. SCI costs Canada $2.67 billion annually, $1.57 billion directly and $1.10 billion indirectly. Hospitalizations ($0.17 billion, 6.5% of total costs), health care professional visits ($0.18 billion, 6.7%), equipment and home improvements ($0.31 billion, 11.6%), and assistant care ($0.87 billion, 32.7%) make up this total [13]. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has one of the highest rates of SCIs worldwide [14,15]. According to the Global Burden of Disease report, traumatic injuries represent 22.6% of years of potential either in terms of disability or life lost in KSA [16]. Recent reports on Saudi male SCI patients reported 43.9% with cervical injury followed by 40.4% with thoracic injury and 3.5% with lumbar injury suffering with disability [15].

Modern neuroprotection and regeneration therapies for SCI focus on limiting tissue damage, preventing downstream injury cascades, and promoting neuronal regeneration. To control inflammation and prevent cellular damage, acute SCI treatments include corticosteroids, anti-inflammatory drugs, and surgical decompression [17]. Anti-inflammatory methylprednisolone is sometimes given within hours of injury to reduce inflammation and neuronal death. These medicines help manage initial damage, but their neuroprotective effects are often limited and come with serious adverse effects such as immunosuppression and metabolic issues [18,19]. Cell-based therapies have gained prominence, especially with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), neural progenitor cells, and Schwann cells (SCs). These cells can enhance neuronal viability, regulate immunological response, and facilitate axonal regeneration [20]. However, cell growth, host tissue integration, and immunological rejection can reduce their efficacy. Stem cell treatment may cause cancer or fibrosis [21]. In addition to cellular methods, biomaterial scaffolds are employed to offer structural support and directional cues for axonal regeneration [22]. These scaffolds, often composed of hydrogels or polymers, are engineered to replicate the extracellular matrix and can be infused with growth factors or pharmaceuticals to promote regeneration [23,24,25,26]. Despite promising in vitro results, material biocompatibility, degradation, and regulated release in the body’s complex milieu hamper clinical use of these scaffolds. Pharmaceutical treatments like neurotrophic factors and neuroprotective compounds have potential, but the blood-spinal cord barrier, targeted specificity, and short half-lives limit their usefulness [27]. The limits require new SCI treatment, with recent studies focusing on multifunctional, customized medications with neuroprotection and regeneration capabilities [28,29,30].

Through the development of more precise diagnostic tools, more targeted medication delivery systems, and innovative therapies, nanotechnology has revolutionized the medical field. Materials with unique properties at the nanoscale have great potential in the medical field, particularly in the fields of imaging, medication delivery, and regenerative medicine [31]. In the nanomaterial world, quantum dots (QDs) are promising due to their adaptable optical characteristics, photostability, broad absorption spectra, and emission patterns that vary with particle size [32]. The unique characteristics of QDs allow them to exceed traditional fluorescent dyes in bioimaging, providing vibrant and persistent images for cellular and molecular diagnostics [33]. QDs provide significant advantages in cancer diagnostics due to their unique optical properties and tunable surface chemistry. These nanoscale semiconductors can be engineered to specifically bind to tumor-associated biomarkers through surface modification with targeting ligands such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers. Upon binding, QDs emit bright and stable fluorescence, allowing for highly sensitive and specific imaging of cancerous tissues. This targeted illumination facilitates early-stage detection, enables real-time tracking of tumor progression, and improves differentiation between malignant and healthy cells, ultimately contributing to more accurate diagnostics and personalized treatment strategies.

Furthermore, QDs are being engineered as multifunctional agents, integrating imaging and therapeutic capabilities in theranostic applications [34,35,36]. QDs continue to enhance nanomedicine, offering fascinating new potential for non-invasive, precisely focused medical interventions. Glioblastoma (GBM), a malignant central nervous system (CNS) tumor, is generally poorly excised after surgery due to its invasive proliferation and imprecise neuronal cell demarcation [37]. To overcome this limitation, a fluorescent 5-aminolevulinic acid was integrated with a spectroscopic probe utilized for GBM resection [38]. ZnCdSe/ZnS QDs were utilized in ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction technology-assisted surgery [39]. Strong reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity, aggregation prevention, and toxicity reduction characterize SeQDS. Their small size allows them to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) quickly, and their accumulation in the brain reduces Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and improves cognitive and memory abilities [40]. A reduction in cell survival was observed when doxorubicin (DOX) was delivered using RGD-coupled graphene QDs, which are advantageous for fluorescence imaging and monitoring drug delivery [41]. Likewise, chlorotoxin-modified nanorods delivered DOX to cerebral tumors through the bloodstream, leading to significant inhibition of tumor proliferation [42]. Oxidative stress (OS) exacerbates SCI by facilitating free radical-induced cellular damage, hence impeding regeneration [43]. Effective neuroprotective techniques necessitate potent antioxidant molecules to mitigate this damage [44]. QDs, characterized by their significant tunability and robust antioxidant characteristics, emerge as viable options for SCI treatment [45,46,47]. Surface engineered QDs, particularly those with intrinsic antioxidant properties or those functionalized with ROS-scavenging ligands, can mitigate oxidative damage by neutralizing free radicals and restoring redox balance within the injured spinal cord microenvironment. Furthermore, their high surface area and adjustable surface chemistry enable the simultaneous delivery of antioxidant agents or genes that enhance endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms. By mitigating OS, QDs may enhance neuronal and glial survival, impede apoptotic pathways, and foster a more conducive biochemical environment for axonal regeneration and functional recovery following SCI. Selenium-doped carbon quantum dots (Se‑CQDs) have demonstrated significant protective effects on astrocytes and PC12 cells against oxidative damage caused by H2O2 in vitro [48]. Additionally, the neuroprotective potential of Se-CQDs was examined in a model of contusion-induced TSCI. The findings indicated that Se-CQDs provided protection to the injured spinal cord by reducing inflammation, preventing the demyelination of nerve fibers, and inhibiting the apoptosis of neuronal cells. Ren et al. reported in comparison to large graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets, GO quantum dots (GOQDs) function as nanozymes that effectively reduce ROS and H2O2 in PC12 cells induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridinium ion (MPP+) [45]. Furthermore, GOQDs demonstrate neuroprotective properties in a neuronal cell model by reducing apoptosis and α-synuclein levels. GOQDs effectively reduce ROS, apoptosis, and mitochondrial damage in zebrafish exposed to MPP+. Further, zebrafish pretreated with GOQDs exhibit enhanced locomotive activity and an increase in Nissl bodies within the brain, indicating that GOQDs effectively mitigate MPP+-induced neurotoxicity, unlike GO nanosheets. GOQDs play a role in mitigating neurotoxicity by enhancing amino acid metabolism, lowering tricarboxylic acid cycle activity, and reducing the activities of steroid biosynthesis, fatty acid biosynthesis, and galactose metabolic pathways, all of which are associated with antioxidation and neurotransmission. Furthermore, QDs can be used as therapeutic antioxidants and bioimaging agents, allowing real-time damage progression monitoring [49,50,51,52].

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) in the field of radiology where many promising tools are focused on the spine and spinal cord represents a paradigm shift in the diagnostic and prognosticating SCI, nevertheless their clinical utility remains uncertain [53]. The application of AI-enabled algorithms using machine learning (ML), deep learning, and convolutional neural networks approaches, which quickly determine and respond to SCI, have been created based on radiographs, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging scans. Therefore, AI systems and research on spinal cord neural injury and restoration can mutually reinforce each other and drive medical innovation to analyze potential solutions [54]. More recently, Dietz et al., studied the potential for clinical integration of ML data in the patient population to improve diagnosis and prognostication of SCI [55]. Arslan and co-workers have recognized enhanced diagnosis of SCI on unconscious and uncooperative patients using dermatomal skin impendence analysis through artificial neural network [56]. In this study, classification methods of support vector machines and hierarchical cluster tree analysis showed improved diagnostic rates in injury and recovery. Interestingly, Tay et al. used ML to evaluate patients with SCI via diffusion tensor imaging [57]. Hence, we conclude that medical imaging will continue to garner significant application of ML for diagnosis and prognosis, and may offer particular benefit to management of SCI given its acuity, complexity variability, and multimodal treatment paradigms.

This multidisciplinary approach, combining advances in neuroscience, technology, and treatment, offers new perspectives and hopes for addressing SCI, a complex and challenging problem leading to a wide range of neurological illness. The aim of this review merges QDs antioxidant discoveries with SCI applications, a fresh approach that current research lacks. Our research on QDs provides a holistic view of SCI care and lays the groundwork for innovative, multifunctional therapeutics that exceed current therapy limitations. QDs’ therapeutic and diagnostic potential in spinal cord damage makes our review a significant, progressive neuroprotective scientific contribution.

1.1 QDs: Synthesis and properties

QDs are semiconductor nanocrystals exhibiting distinctive optical and electrical characteristics attributable to quantum confinement processes. These nanomaterials often measure between 2 and 10 nm in diameter, positioning them within a size range where their physical and chemical characteristics markedly diverge from those of bulk materials. The size tunability of QDs serves as a significant advantage in controlling their light-emission properties. This enables simultaneous excitation of various-sized QDs using a single light source, along with component-tunable broad spectral windows as shown in Figure 1 [58]. The elevated molar extinction coefficients of QDs contribute to the enhanced brightness of their fluorescence, in conjunction with a high quantum yield (QY) [59]. The elevated stability against photobleaching of QDs facilitates prolonged dynamic imaging [60]. The observed blinking of QDs is categorized into states of “dimmed” or “grey” (intermediate) intensities, ensuring the detection of a single dot event, such as the observation of an individual protein [61]. The distinctive size-dependent characteristics of QDs render them indispensable in domains such as optoelectronics, bioimaging, photovoltaics, and sensing technologies.

![Figure 1

The photophysical features of QDs made in biological or biomimetic systems. (a) Size-tunable fluorescence output and multiple QDs being excited by the same light source at the same time. (b) The QDs made up of various components have wide spectrum ranges that go from ultraviolet to infrared [58].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_001.jpg)

The photophysical features of QDs made in biological or biomimetic systems. (a) Size-tunable fluorescence output and multiple QDs being excited by the same light source at the same time. (b) The QDs made up of various components have wide spectrum ranges that go from ultraviolet to infrared [58].

Regarding the properties mentioned, QDs have established an excellent track record in the fields of medical and biological sciences. QDs are presently utilized as luminescent tools and labels in drug delivery and targeting, as well as in the sensing of DNA and oligonucleotides. They play a significant role in various scientific imaging methods, including molecular histopathology, flow cytometry-based identifications, disease identification, and biomedical imaging. Numerous studies have demonstrated the utility of QDs in clinical applications, such as sentinel lymph node visualization, micrometastasis detection, and photodynamic therapy (PDT) [62]. Furthermore, several applications have been suggested for QDs, such as carriers for drug delivery and light indicators for biological coding. Like other nanomaterials, there are concerns regarding the potential toxicity of QDs that need to be addressed prior to their clinical application [63].

Significant advancements have been achieved in novel synthesis pathways for QDs. The formation of QDs is primarily classified into top-down and bottom-up techniques, each utilizing different methodologies to attain the nanoscale size and specific features [64,65]. Top-down synthesis methods entail the disintegration of bulk materials into nanoscale particles via physical or mechanical procedures. These techniques are very effective for attaining accurate morphologies and structural configurations. Electron beam lithography (EBL) is a prevalent top-down method that employs a highly focused electron beam to intricately shape nanoscale objects with remarkable accuracy [66]. Despite its great efficacy, EBL is costly and time-consuming, constraining its scalability. A prevalent technique is mechanical milling, which reduces bulk materials to nanoparticles via high-energy grinding. This approach is economical and appropriate for large-scale manufacturing; nevertheless, it frequently yields particles with broad size dispersion and possible surface imperfections. Alternative top-down approaches, such as laser ablation and ion implantation, are utilized but frequently need advanced equipment and specialized knowledge. Conversely, bottom-up synthesis techniques entail the chemical or physical construction of QDs from atomic or molecule precursors. These approaches are preferred for their capacity to regulate the dimensions, shape, and surface characteristics of the QDs. Colloidal synthesis is the predominant method employed owing to its flexibility and accuracy. This technique entails high-temperature reactions utilizing surfactants or stabilizing chemicals to regulate particle development and inhibit aggregation. Colloidal synthesis is highly efficient for generating monodisperse QDs with adjustable optical and electrical characteristics. Additional notable bottom-up techniques encompass hydrothermal and solvothermal methods, which entail high-pressure, high-temperature reactions in either aqueous or organic solvents [67,68]. The methods employed are environmentally sustainable, scalable, and produce QDs with outstanding crystallinity. Table 1 represents a comprehensive classification of the synthesis methodologies for QDs, including their respective benefits and drawbacks. Bottom-up techniques, including hydrothermal, microwave-assisted, soft-template, and stepwise organic synthesis, provide benefits such as scalability, controllable particle dimensions, and doping potential. But they may be tedious, expensive, and occasionally susceptible to aggregation or need extensive purification. Top-down methods, such as oxidative/reductive cutting, electrochemical cutting, and pulsed laser ablation (PLA), are frequently more appropriate for large-scale production and expedited synthesis. Nonetheless, these methods may lead to inconsistent particle sizes, necessitate the use of aggressive chemicals or costly instruments, and are less favorable for doping methods. The synthesis of nanomaterials by microwave methods, a bottom-up approach offers benefits such as reduced reaction time, swift and uniform heating, and enhanced yield and purity. Phytic acid, which is rich in phosphorus, was combined with ethylenediamine in water and subjected to treatment in a domestic microwave oven for a duration of 8 min by Wang et al. [69]. Figure 2(a) illustrates the synthesis method employed for the phosphorus-containing carbon dots (CDs). The products acquired were subsequently purified through acetone extraction, resulting in green fluorescent CDs (as shown in Figure 2b) with a QY of 21.65%. Lower excitations showed two distinct peak emissions, whereas at higher excitations, a single peak emission was observed for these CDs. The authors demonstrated that a covalent linkage of the phosphorus functional groups to the graphite-like structure was evident in the CDs. Tang and coworkers demonstrated a microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis (Figure 2c) of graphene quantum dots (GQDs) derived from glucose, aiming to produce GQDs with diameters spanning from 2.9 to 3.9 nm. This study illustrated that the size of GQDs can be controlled within the range of 1.65–21 nm by adjusting the reaction time from 1 to 9 min. The GQDs exhibited excitation-dependent emission characteristics, with QYs calculated to range from 7 to 11%. The GQDs demonstrated the ability to convert blue light into white light, which was further confirmed by applying GQDs onto a blue-light emitting diode. The application of these GQDs enables the conversion of blue light into white light when they are applied to a blue-light-emitting diode.

Synthesis methods of QDs and their advantages and disadvantages

| Method | Synthesis route | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom-up | Hydrothermal | Simple and effective method; supports heteroatom doping and surface passivation | Time-consuming and costly; requires extensive purification; may produce minor aggregation; non-uniform sizes |

| Microwave assisted | Rapid reaction time; produces uniform particle sizes; enables doping with ease | Suitable for small-scale synthesis; requires intensive purification; limited industrial scalability | |

| Soft-template | Produces uniform particle sizes; straightforward purification; scalable for large production | Prone to particle aggregation | |

| Stepwise organic synthesis | Offers excellent control over structure, size, and photoluminescence (PL) properties | Complex and tedious processes; often stable only in organic solvents; limited scalability potential | |

| Top-down | Oxidative/reductive cutting | Utilizes readily available precursors; ideal for large-scale production | Non-uniform particle sizes; requires harsh chemicals and purification; less favorable for doping |

| Electrochemical Cutting | Rapid synthesis; produces uniform particle sizes with good crystallinity | Difficult to scale; costly raw materials; limited doping flexibility unless precursors are pre-doped | |

| PLA | Environmentally friendly; requires no harsh chemicals; straightforward purification | Requires costly equipment; less suited for heteroatom doping |

![Figure 2

(a) Schematic representation of the production of phosphorus-containing CDs. (b) Emission in the presence of natural light (on the left) and 365 nm UV radiation (on the right) [69]. (c) Synthesis of glucose-derived GQDs using microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis method.](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_002.jpg)

(a) Schematic representation of the production of phosphorus-containing CDs. (b) Emission in the presence of natural light (on the left) and 365 nm UV radiation (on the right) [69]. (c) Synthesis of glucose-derived GQDs using microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis method.

Non-metal QDs have gained significant attention as environmentally friendly and biocompatible alternatives to traditional metal-based QDs. Among these, CDs, GQDs, and polymer dots (PDs) have emerged as promising materials due to their unique optical, chemical, and structural properties [70,71,72]. CDs are zero-dimensional nanomaterials composed primarily of carbon, typically synthesized via hydrothermal, solvothermal, or microwave-assisted methods. These methods involve the carbonization of organic precursors such as citric acid, glucose, or chitosan [73,74,75,76]. CDs exhibit strong PL, high photostability, low toxicity, and excellent water dispersibility, making them suitable for biomedical imaging, sensing, and photocatalysis. The emission properties of CDs can be tuned by controlling the precursor composition, synthesis temperature, and surface functionalization. Notably, surface passivation with polymers or organic ligands can significantly enhance their QY and improve their stability. GQDs are small fragments of graphene sheets with lateral dimensions below 10 nm, often synthesized via top-down (e.g., oxidative cutting of GO) or bottom-up (e.g., carbonization of organic molecules) approaches [36,65]. GQDs possess unique sp2 carbon structures that provide excellent PL, superior chemical stability, and strong antioxidant properties [77]. Their tunable bandgap enables broad absorption across the visible to near-infrared spectrum. GQDs also demonstrate high biocompatibility, making them ideal candidates for bioimaging, drug delivery, and PDT [78]. Their fluorescence behavior is strongly influenced by surface functional groups, edge states, and quantum confinement effects. PDs are fluorescent polymeric nanoparticles that combine the advantages of organic dyes and QDs [79]. Typically synthesized through emulsion polymerization, nanoprecipitation, or self-assembly methods, PDs offer tunable fluorescence, high photostability, and low cytotoxicity. Their structure allows precise engineering of size, shape, and surface properties, making them versatile platforms for biosensing, imaging, and optoelectronic applications [80,81]. The emission properties of PDs can be tailored by modifying their polymer backbone or incorporating fluorophores with distinct electronic structures [82].

Their application in biological systems largely depends on their biocompatibility and colloidal stability, both of which are significantly influenced by the synthesis route employed [83]. The method of synthesis governs not only the size and surface chemistry of the QDs but also the presence of impurities, surface defects, and the nature of surface ligands all of which determine how QDs interact with biological environments.

Hydrothermal synthesis is a widely used method that involves the synthesis of QDs under high pressure and temperature in aqueous or non-aqueous solvents [84]. This technique often results in QDs with high crystallinity and fewer surface defects, which improves photostability and reduces the generation of ROS under illumination which is an important factor for biocompatibility. However, if not properly capped or functionalized, QDs synthesized via this route may aggregate in physiological media due to limited water dispersibility [85]. To improve biological stability, hydrophilic surface coatings such as polyethylene glycol, carboxylic acids, or zwitterionic ligands are often introduced.

Microwave-assisted techniques allow for rapid and uniform heating, resulting in highly monodisperse QDs with controlled sizes. The rapid reaction kinetics can limit the formation of impurities and reduce batch-to-batch variability. When paired with suitable precursors and stabilizing agents, QDs produced by this method exhibit enhanced colloidal stability and lower toxicity due to reduced defect densities [86]. Moreover, the ability to perform synthesis in aqueous media makes this approach more environmentally friendly and compatible with biological systems. Green or biosynthesis methods utilize natural reducing agents such as plant extracts, amino acids, or polysaccharides to produce QDs under mild conditions. These routes avoid toxic reagents and heavy metals, thereby enhancing the inherent biocompatibility of the resulting nanomaterials [58]. Furthermore, biomolecules used in synthesis often remain on the QDs surface as capping agents, improving water solubility and enabling interactions with biological targets. However, green synthesis may offer limited control over particle size and uniformity unless carefully optimized [87]. Traditional organometallic synthesis involves high-temperature reactions in organic solvents and typically produces high-quality QDs with excellent optical properties. However, these QDs are often capped with hydrophobic ligands like trioctylphosphine oxide, making them poorly dispersible in aqueous environments [88,89,90]. To render them biologically compatible, additional ligand exchange or encapsulation in amphiphilic polymers or liposomes is required [91]. These post-synthesis modifications are crucial to reduce cytotoxicity and improve in vivo stability [92]. Regardless of the initial synthesis method, surface functionalization plays a vital role in governing QD behavior in biological systems. Functionalization with biocompatible ligands not only enhances solubility and colloidal stability but also reduces protein adsorption and immune recognition [89].

1.2 Properties of QDs

Quantum confinement effects provide distinctive optical and electrical characteristics in QDs, providing them with several benefits over existing fluorophores, including organic dyes, fluorescent proteins, and lanthanide chelates [93]. Factors that significantly affect fluorophore behavior, and consequently their suitability for various applications, encompass the breadth of the excitation spectrum, the width of the emission spectrum, photostability, and the decay lifespan. Conventional dyes exhibit limited excitation spectra, necessitating illumination by light of a specific wavelength, which differs among individual dyes. QDs exhibit broad absorption spectra, enabling excitation across a wide range of wavelengths. This characteristic can be utilized to simultaneously excite multiple differently colored QDs using a single wavelength [94]. Traditional dyes exhibit broad emission spectra, indicating that the spectra of various dyes may significantly overlap. This restricts the quantity of fluorescent probes that can be utilized to label various biological molecules and be spectrally distinguished at the same time. Conversely, QDs have narrow emission spectra, which may be manipulated relatively easily by altering core size and composition, as well as by modifying surface coatings. They can be designed to emit light throughout a range of specific wavelengths, from ultraviolet (UV) to infrared (IR). The narrow emission and broad absorption spectra of QDs render them highly suitable for multiplexed imaging, where various colors and intensities are integrated to encode genes, proteins, and small-molecule libraries [95]. Due to their excellent photostability, they may facilitate the monitoring of prolonged interactions among multiple-labeled biological molecules within cells.

Photostability is an essential characteristic in several fluorescence applications, in which QDs provide a distinct advantage. In contrast to organic fluorophores that degrade after few minutes of light exposure, QDs exhibit remarkable stability, allowing for prolonged cycles of excitation and fluorescence for hours while maintaining high brightness and resistance to photobleaching. QDs have demonstrated greater photostability compared to several organic dyes [96,97], including Alexa488, which is noted as the most stable organic dye [98]. Chan and Nie reported semiconductor QDs with bright luminescence (zinc sulfide-capped cadmium selenide) that have been covalently attached to biomolecules for highly sensitive biological identification. In comparison to organic dyes such as rhodamine, these QDs demonstrate a 20 times greater brightness, a stability against photobleaching that is 100 times higher, and a spectral line width that is one-third narrower [97].

The characteristics of the PL of QDs are their size and excitation-dependent emission features. The study by Liu et al. stated the properties of polyethylenimine (PEI)-passivated carbon quantum dots, which exhibited stable multicolor luminescence dependent on the excitation wavelength [99]. The aqueous solution of these CDs exhibited blue, green, and red fluorescence when subjected to UV light excitation, blue, and green, respectively. The PL spectra of CD solution demonstrated a red-shifted emission characteristic, transitioning from 450 to 550 nm as the excitation wavelengths varied from 340 to 500 nm. This notable behavior was attributed to the size and surface state non-uniformity of the CDs passivated by PEI. Moreover, various studies have also indicated the presence of excitation wavelength independent CDs. Dong et al. documented the synthesis of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped CDs derived from citric acid and l-cysteine as precursors, which exhibited emission characteristics independent of excitation [100]. The authors elucidated that the PL of the CDs is dependent on surface states rather than shape, and that these surface states are homogeneous. In a prior study, similar excitation-independent emissions were achieved for nitrogen and zinc co-doped CDs [101].

The PL property has been observed to exhibit pH dependence. Pan et al. proposed hydrothermally prepared GQDs that exhibited strong emission under alkaline conditions, while in acidic environments, the PL emission was substantially quenched [102]. The PL intensity exhibited reversibility; specifically, when the pH of the GQD solution alternated between 12 and 1, the PL demonstrated a reversible change as shown in Figure 3a. It is crucial to observe that the pH of the solution affected only the PL intensity of GQDs, while the PL emission wavelength remained unchanged. Furthermore, the concentrations of the CDs or GQDs also affected their PL intensity or wavelength. The CDs synthesized from banana juice, as published by De and Karak, exhibited concentration-dependent photoluminescent characteristics [103]. The spectra presented in Figure 3b revealed that the PL intensity diminishes with rising concentrations of the CDs. The author elucidated that at low concentrations, the interaction among polar groups reduces, and at large concentrations, the abundance of polar functional groups tends to create agglomerates. Das et al. have observed a similar phenomenon for the nitrogen and sulfur co-doped CDs produced from kappa carrageenan and urea [104].

QDs are nanoscale semiconductor particles, often measuring 2–10 nm, exhibiting distinctive optical and electrical characteristics due to quantum confinement phenomena. Their dimensions directly affect their emission wavelength, with smaller QDs generating blue light and bigger ones emitting red [105]. QDs are composed of a crystalline semiconductor core, often fabricated from materials such as CdSe, PbS, or InP [106]. They may be categorized as core-only, core–shell (including a protective shell like ZnS to improve stability and efficiency), or alloyed QDs (incorporating mixed elements for customized features). QDs are typically spherical in morphology; however, they may also adopt morphologies such as rods or tetrapods, depending upon the synthesis conditions [107]. Surface functionalization with organic or inorganic ligands enhances solubility, stability, and versatility for applications in optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and biomedicine. On the other hand, CDs and GQDs are carbon-derived nanomaterials exhibiting exceptional optical, electrical, and structural characteristics, positioning them as sustainable substitutes for conventional semiconductor QDs. CDs are generally spherical nanoparticles, measuring less than 10 nm, characterized by amorphous or partially crystallized structures [108]. Their outstanding PL, minimal toxicity, and remarkable biocompatibility facilitate their use in bioimaging, sensors, and photocatalysis [109,110]. GQDs have significant quantum confinement and edge effects, providing adjustable fluorescence, elevated conductivity, and exceptional chemical stability [77]. Both CDs and GQDs are economical, eco-friendly, and exceptionally adaptable, with applications in energy storage, optoelectronics, antimicrobial agents, bioimaging, and environmental monitoring [111,112]. Table 2 summarizes recent advancements in CDs utilized as fluorescent probes for detecting neurological biomarkers in biological fluids. The table highlights key features such as synthesis methods, surface functionalization, target biomarkers, and detection limits, emphasizing the versatility and sensitivity of CDs in neurodiagnostic applications.

CDs utilized as fluorescent probes for the identification of neurological biomarkers in biological fluids

| Type of QD | Precursors | Excitation/emission wavelength (nm) | LOD | Neurological biofluids | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDs-COOH functionalized | Tris (hydroxymethyl)aminomethane | 365/460 | 50 nM | Cerebral | [113] |

| N-doped CDs | Sodium citrate and tripolycyanamide | 345/440 | 5 nM | Human serum and rat brain microdialysate | [114] |

| Fe(+3)-doped CDs | Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane | 365/445 | 9.1 nM | Rat brain microdialysate | [115] |

| CDs-antibody conjugate | Citric acid | 360/447 | 25 pg/mL | Human serum | [116] |

| N-doped GQDs | Citric acid and ammonia | 355/440 | 1.22 µM | Detection of tacrine | [117] |

| MIPs-CDs | Citric acid | 360/465 | 3 µM | — | [118] |

| Curcumin-GQDs | Citric acid | 370/500 | 12.4 pg/mL | Blood plasma (human) | [119] |

| Te-doped CDs | 2,7-Bis(phenylselanyl)-9H-fluoren-9-one | 380/440 | 8 pM | Brain of mild depression mice | [120] |

| S-doped CDs/AuNPs | Phenylamine-4-sulfonic acid | 365/465 | 0.23 µM | Ampoule, urine and serum human | [121] |

| CDs | Corn extract | 353/446 | 6.46 µM | Human cerebrospinal fluid and serum | [122] |

2 OS in SCI

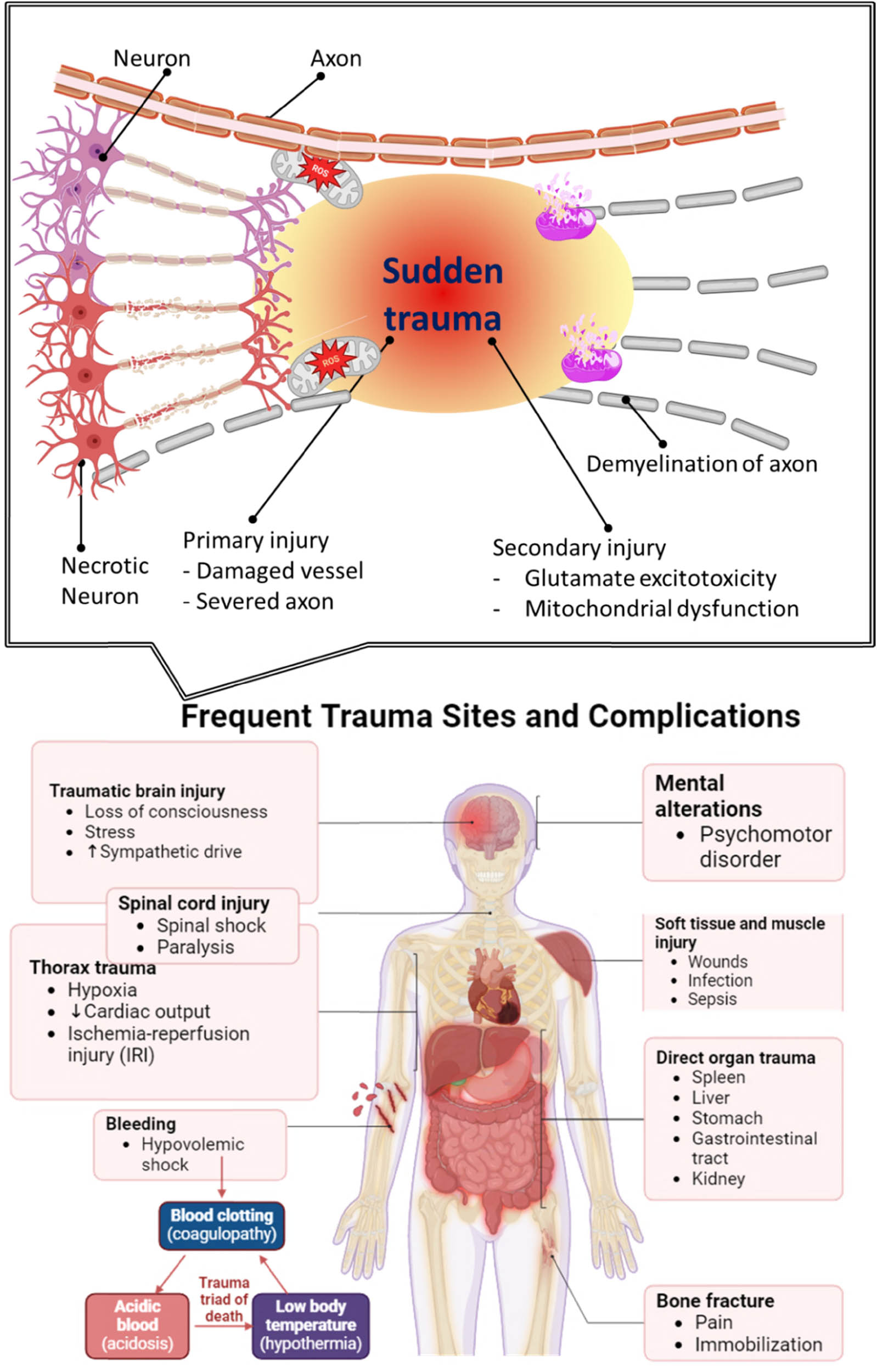

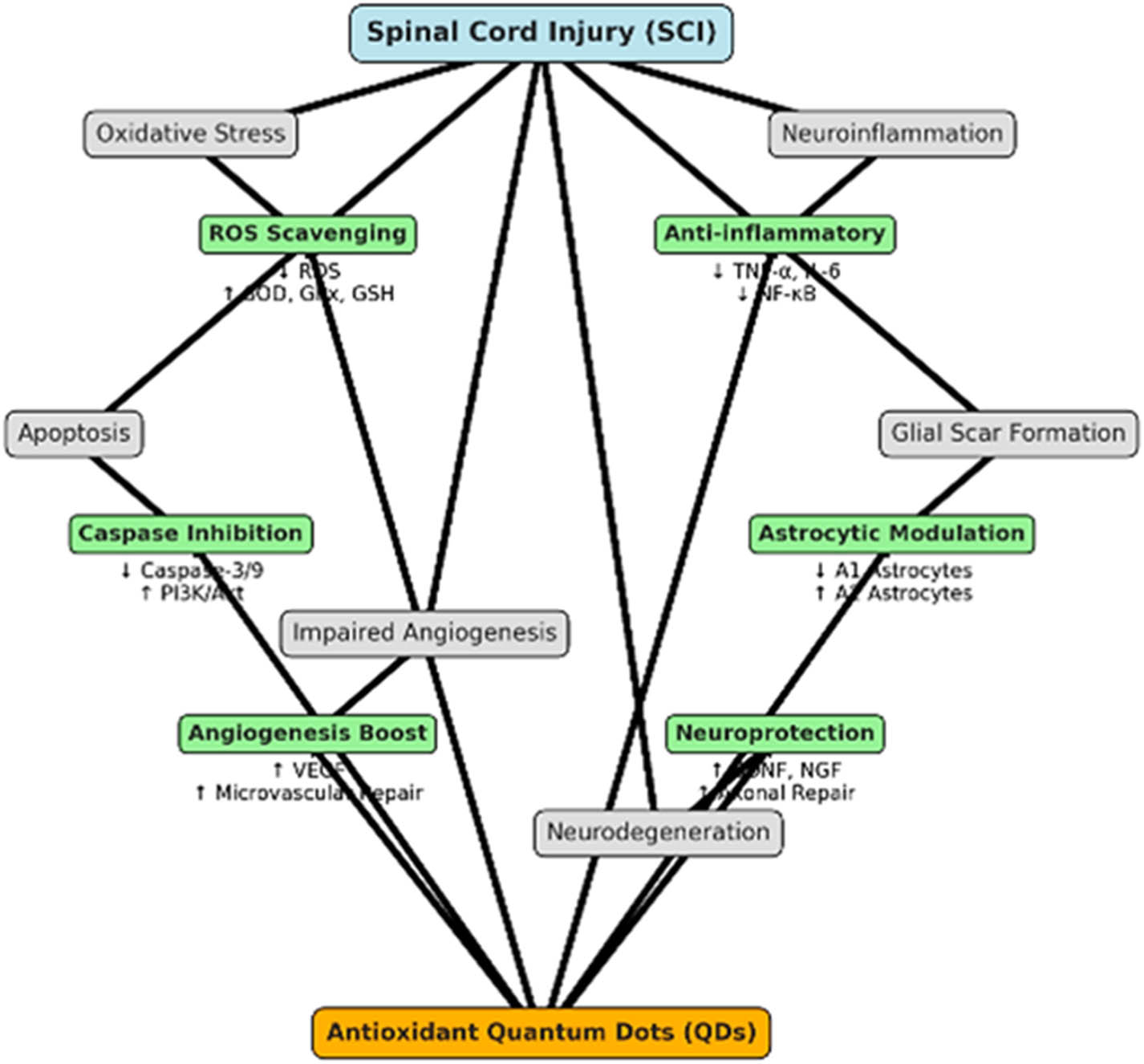

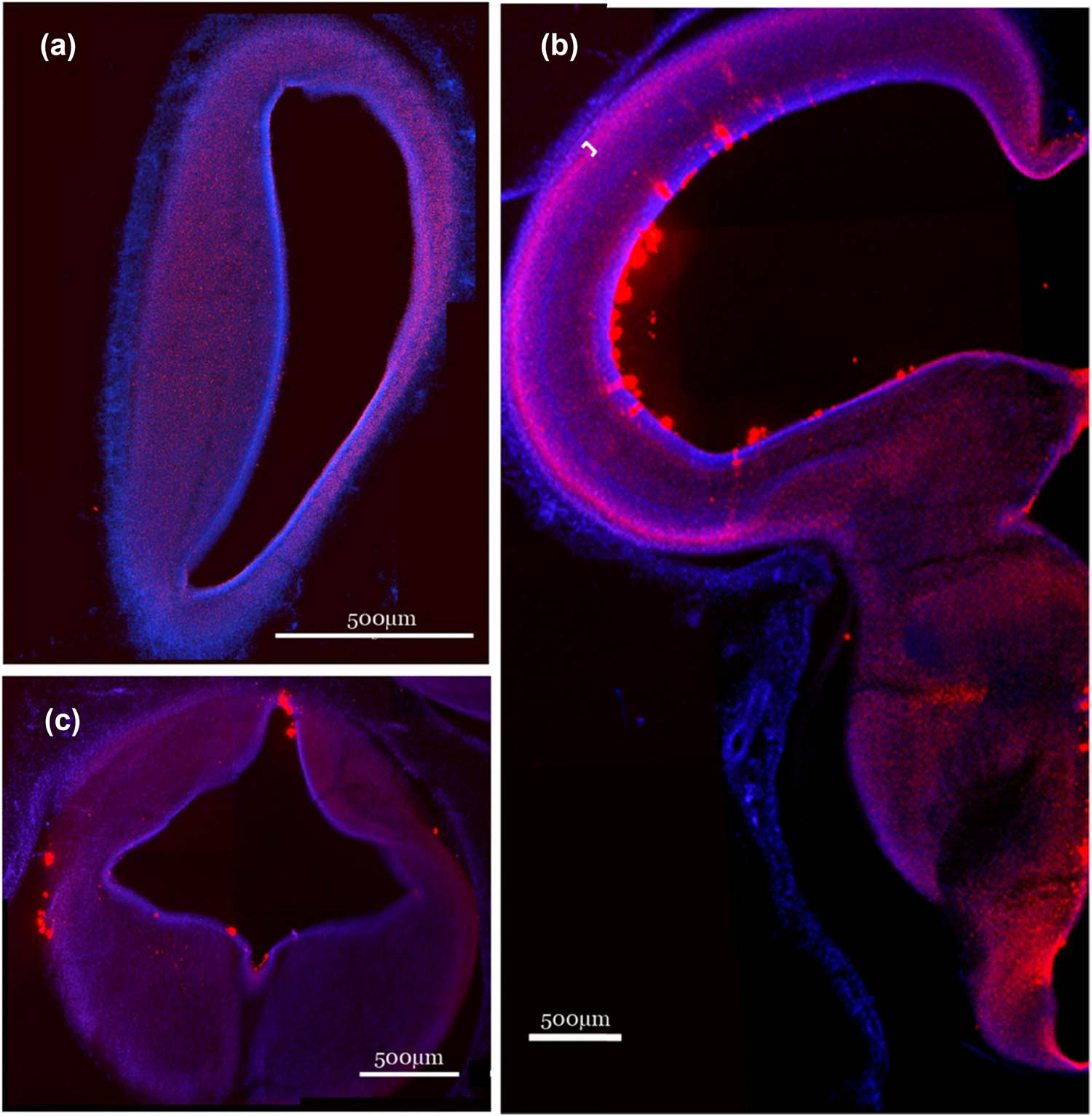

Figure 4 offers a detailed examination of trauma-induced damage across multiple physiological systems, emphasizing SCI and associated OS processes [123,124,125]. The figure comprises two sections: the upper illustration presents a close-up of spinal cord trauma, illustrating the cellular origins of ROS following abrupt mechanical injury, whereas the lower section emphasizes the systemic complications and injury sites linked to severe bodily trauma [126]. The upper section depicts the key steps initiated by acute spinal injury, encompassing the compromise of cellular integrity and the ensuing production of ROS [127]. Mitochondria, depicted with indicators for ROS buildup, exhibit malfunction post-trauma and serve as significant sources of OS. Alongside mitochondrial ROS, immune cells, including neutrophils and macrophages, are attracted to the site of injury, where they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS as components of the inflammatory response [128]. The ROS produced by mitochondrial failure and immune cell activity intensify cellular damage by mechanisms such as lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA breakage, leading to neuronal cell death and scar tissue development that further impede recovery [129,130,131]. The lower section of the picture elaborates on the systemic consequences and prevalent trauma locations that often follow SCI. Traumatic brain injury and spinal cord damage frequently co-occur, resulting in various neurological consequences, including loss of consciousness, tension, and heightened sympathetic drive, which can exacerbate the total injury response [124,132,133,134,135]. Thoracic trauma, encompassing hypoxia and ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) [136], diminishes cardiac output and oxygen transport [137,138], hence impairing the tissue’s capacity to handle OS and aggravating neuronal injury [139]. Additional significant systemic effects encompass cognitive changes, psychomotor dysfunctions, infections resulting from soft tissue and muscular injuries [140], direct harm to organs like the spleen and liver, bone fractures, and hemorrhaging that may result in hypovolemic shock [141]. The trauma-induced “triad of death” (acidosis, coagulopathy, and hypothermia) is prominently featured, highlighting how these interrelated variables hinder recovery by impairing the body’s innate defense mechanisms.

The impact of OS on neuronal cells and tissue in SCI.

Figure 5 delineates the intricate pathways of OS injury subsequent to SCI, showcasing a cascade of cellular and molecular disturbances that exacerbate secondary injury. Following SCI, the first trauma induces a microenvironmental disruption, initiating many metabolic processes that intensify OS and inflammation, all of which significantly contribute to the exacerbation of neuronal damage [142]. The illustration depicts many principal sources of ROS formation subsequent to SCI [143]. Neutrophil enzymatic processes are among the initial contributors, as neutrophils are swiftly drawn to the site of injury and emit ROS to eradicate injured cells and pathogens. Furthermore, hemoglobin and ferrous iron (Fe2⁺) are liberated during cellular lysis, engaging in Fenton reactions that generate extremely reactive hydroxyl radicals. Mitochondrial failure, a characteristic of SCI, concurrently results in excess calcium (Ca2⁺), disruption of the respiratory chain, and increased production of ROS [144]. This mitochondrial dysfunction not only produces ROS directly but also diminishes the cell’s capacity to regulate OS, hence intensifying ROS buildup. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) experiences stress, leading to impaired protein folding and contributing to cellular malfunction, hence increasing OS [145]. The elevation of ROS triggers a detrimental cycle, illustrated by the positive feedback loop [146]. Increased ROS levels stimulate an inflammatory response, which then attracts more inflammatory cells, each contributing to increased ROS generation. This feedback loop exacerbates OS, sustaining cellular and tissue damage. The image illustrates that OS produces multiple detrimental effects downstream. ROS trigger lipid peroxidation, compromising cell membranes and enhancing their permeability, ultimately resulting in cell death [147]. ROS interact with proteins and nucleic acids, creating adducts that disrupt cellular function and facilitate neurodegeneration. Ultimately, these mechanisms lead to extensive neuronal apoptosis and autophagy, both of which undermine neural tissue integrity and impede recovery [148].

SCI-related OS damage mechanisms. Neutrophils, phagocytes, mitochondria, ER, and lysed red blood cells (Fe2+) generate excessive ROS after SCI. ROS emission beyond scavenging capacity causes OS. ROS promote lipid peroxidation, protein and DNA damage, and inflammatory response crosstalk, deteriorating SCI.

2.1 SCI OS hypothesis: Excess ROS generation

The production of excessive ROS is crucial in the secondary injury processes after SCI, greatly contributing to cellular and tissue damage. ROS are byproducts of normal cellular metabolism, mostly generated in mitochondria via oxidative phosphorylation [149]. Under physiological conditions, ROS levels are meticulously managed by antioxidant defense mechanisms [150]. Following SCI, there is a significant increase in ROS generation due to mitochondrial malfunction, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and the degradation of cellular structures, which surpasses the cellular antioxidant defenses. This ROS overload initiates a series of harmful events, resulting in neuronal death, tissue necrosis, and inflammation, which worsen the initial injury. In the context of SCI, ROS formation is predominantly heightened by OS processes, wherein excessive ROS compromise cellular membranes and organelles [151]. The mitochondria, due to their heightened sensitivity to stress, are a principal generator of ROS following injury. Spinal cord trauma disrupts mitochondrial activity, decreasing the electron transport chain (ETC) and increasing electron leakage, resulting in the formation of superoxide anions through reactions with oxygen [152]. Superoxide is then transformed into more reactive ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals, which target cellular lipids, proteins, and DNA. This oxidative damage undermines cellular integrity and facilitates apoptotic and necrotic cell death in neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes, resulting in additional functional and structural deterioration in the damaged spinal cord [153]. Moreover, ROS overload induces neuroinflammation by activating immune cells, including microglia and invading macrophages, which secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and exacerbate ROS generation. The inflammatory response to SCI can be advantageous in many respects, as it eliminates debris and fosters a regenerative milieu; however, the overproduction of ROS by activated microglia and macrophages perpetuates a chronic inflammatory cycle that obstructs tissue regeneration. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-1β, intensify the inflammatory response, establishing a detrimental milieu that obstructs axonal regeneration and remyelination [154]. This chronic inflammatory condition sustains a cycle of ROS production and oxidative harm, resulting in enduring functional impairments and ongoing pain in SCI patients [155].

The degradation of cellular and extracellular components caused by ROS overload further intensifies excitotoxicity, a phenomenon in which impaired neurons release excessive amounts of glutamate [156]. The increased glutamate concentration excessively activates N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors on neighboring neurons, resulting in intracellular calcium overload that subsequently enhances ROS generation and mitochondrial impairment [157]. The interaction between calcium and ROS intensifies cellular toxicity, leading to extensive neuronal death. Therapeutic approaches aimed at ROS and OS possesses considerable potential for alleviating SCI damage [158]. Antioxidants, including N-acetylcysteine (NAC), edaravone, and resveratrol, have demonstrated potential in experimental models by neutralizing ROS and diminishing lipid peroxidation. These drugs seek to restore the redox equilibrium, safeguard cellular integrity, and mitigate inflammation, thus maintaining neural functionality [159]. The intricacy of SCI pathology and the constraints of systemic antioxidant administration highlight the necessity for focused therapeutics that precisely regulates ROS levels within the spinal cord. Advancements in nanotechnology, including antioxidant-loaded nanoparticles, present exciting opportunities for precise control of ROS, thereby enhancing therapeutic outcomes in SCI patients [160]. The overproduction of ROS after SCI greatly contributes to subsequent damage mechanisms, such as neuronal death, inflammation, and excitotoxicity [161]. Mitigating excess ROS using specific antioxidant therapy and novel delivery mechanisms may enhance functional recovery and diminish long-term damage in SCI patients [162]. Nonetheless, additional study is required to comprehensively comprehend ROS dynamics and formulate effective, tailored therapies that may be used in clinical practice.

Liu et al. synthesized aldehyde-scavenging polypeptides (PAH)-curcumin conjugate nanoassemblies (PFCN) for neuroprotection in SCI by a straightforward in situ reaction-induced self-assembly method. Oxidative and acidic microenvironments in SCI may generate PAH and curcumin from synthesized PFCN [163]. PFCN mitigated neuroinflammation by eliminating harmful aldehydes and reactive nitrogen and oxygen species in neurons (Figure 6), controlling microglial M1/M2 polarization, and decreasing inflammation-related cytokines. In the contusive SCI rat model, intravenous PFCN was able to mitigate the detrimental spinal cord microenvironment, safeguard neurons, and enhance motor performance.

![Figure 6

Schematic representation of the preparation of PFCN for integrated treatment of SCI [163].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_006.jpg)

Schematic representation of the preparation of PFCN for integrated treatment of SCI [163].

Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) is a polar derivative of bile acid that has shown neuroprotective properties in various nervous illness models. Nonetheless, the impact and fundamental pathway of TUDCA on SCI remain inadequately clarified. This study seeks to examine the defensive benefits of TUDCA in the SCI mice model and the associated mechanisms involved [164]. TUDCA treatment may mitigate secondary injury and enhance functional recovery by diminishing OS, seditious reaction, and apoptosis resulting from primary injury, while also facilitating axon regeneration and remyelination, presenting a possible therapeutic option for human SCI recovery. From a molecular perspective, OS and inflammatory pathways are primary orchestrators of interconnected dysregulated pathways subsequent to SCI. It emphasizes the necessity of developing multitarget therapy for SCI sequelae. Polyphenols, as secondary metabolites generated from plants, possess the potential to serve as alternative physiological factors for the therapy of SCI. These secondary metabolites exhibited intonation consequences on neuronal OS, neuroinflammation, and aberrant extrinsic axonal tracts in the development and course of SCI. This review elucidates the significant significance of phenolic compounds as essential phytochemicals in modulating dysregulated OS and inflammatory signaling mediators, as well as extrinsic processes of axonal regeneration following SCI, based on preclinical and clinical investigations [165]. The activation of OS and apoptosis-induced cell death considerably contributes to the advancement of SCI. Current data indicate that maltol has natural antioxidative effects via inhibiting OS and apoptosis. Nonetheless, the substantial impact of maltol on SCI therapy is yet to be assessed. This work investigated maltol administration, which may induce Nrf2 expression and facilitate the retranslocation of Nrf2 from the cytosol to the nucleus, thereby inhibiting OS signaling and apoptosis-related neuronal cell death after SCI. Moreover, maltol administration augments PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in PC12 cells, promoting the restoration of mitochondrial functions [166]. The transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) has surfaced as a prospective therapy for SCI. The poor survival and differentiation rates of BMSCs in the spinal cord milieu considerably restrict their therapeutic efficacy. TUDCA, an active compound derived from bear bile, has shown neuroprotective, antioxidant, and antiapoptotic properties in SCI. The current work aims to investigate the potential advantages of merging TUDCA with BMSC transplantation in an animal model of SCI. The findings indicated that TUDCA markedly improved BMSC survivability while decreasing apoptosis and OS in both in vitro and in vivo settings. TUDCA expedited tissue regeneration and enhanced functional recovery post-BMSC implantation in SCI. The effects were mediated via the Nrf-2 signaling tract, as shown by the increase in Nrf-2, NQO-1, and HO-1 expression levels [167]. A thioketal-based, ROS-scavenging hydrogel was synthesized for the encapsulation of BMSCs, facilitating neurogenesis and axon re-formation by mitigating excessive ROS and reconstructing a regenerative milieu [168]. The hydrogel effectively encapsulated BMSCs and exhibited significant neuroprotection in vivo by diminishing endogenous ROS production, mitigating ROS-induced oxidative impairment, and downregulating inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and TNF-α, thereby reducing cell apoptosis in spinal cord tissue. The BMSC-conjugated ROS-scavenging hydrogel decreased scar formation and promoted neurogenesis in spinal cord tissue, therefore significantly improving motor efficient regaining in SCI mice. To investigate the impact of photobiomodulation (PBM) on axon renewal and alterations in secretion from dorsal root ganglion (DRG) under OS after SCI, and to further examine how PBM-induced changes in DRG secretion influence macrophage polarization [169]. The PBM-DRG model was developed to conduct PBM on neurons subjected to OS in vitro. The outcome yielded energy of 4 J. Approximately 100 μM H2O2 was introduced to the culture medium to induce OS after SCI. A ROS test kit was applied to quantify ROS levels in the DRG. The neuronal survival rate was assessed by the CCK-8 assay, and axonal regeneration was examined via immunofluorescence techniques.

2.2 How QDs act as antioxidants?

QDs serve as effective antioxidants owing to their distinctive electrical configuration and adjustable surface characteristics, allowing them to neutralize ROS and avert oxidative harm. The antioxidant efficacy of QDs is mostly contingent upon their composition and surface changes, often accomplished by doping with elements such as sulfur, nitrogen, or cerium, which augment ROS scavenging capabilities [170]. These alterations allow QDs to emulate natural antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), facilitating the conversion of superoxide radicals (

GQDs seem to be among the brightest antioxidants due to their suitable antioxidant properties, distinctive structure, superior cytocompatibility, and little toxicity. Nonetheless, the comparatively diminished antioxidant activity compared to inorganic semiconductor materials and the ambiguous antioxidant mechanism restricted their cellular applications. This article investigates the antioxidant process by examining the correlation between antioxidant behavior and oxygenated surface groups. The overall oxygen fraction was regulated by post-preparation reduction with NaBH4, while the specific types of oxygen functional groups were modified by free radicals during the synthesis of GQDs [171]. Hemmateenejad et al. developed a novel QD-based test to assess antioxidant and polyphenolic activity [172]. This experiment measures the inhibitory impact of antioxidant/polyphenolic substances on the UV-induced bleaching of l-cysteine-capped CdTe QDs. QDs demonstrated remarkable photostability in the absence of UV exposure, although they underwent fast bleaching when subjected to UV irradiation. The production of ROS during UV irradiation is likely the primary factor contributing to the photobleaching of QDs. The comparison of the photostability of QDs in buffer solution, both with and without sodium azide, a recognized quencher of singlet oxygen, corroborated the role of singlet oxygen in the photobleaching of QDs. The photobleaching impact caused by ROS may be mitigated by the presence of antioxidant or polyphenolic substances. We evaluated several antioxidant and polyphenolic substances, in addition to established antioxidants like trolox and four distinct varieties of tea. Chong et al. showed that GQDs may effectively scavenge various free radicals, therefore protecting cells from oxidative injury. Upon exposure to blue light, GQDs demonstrate considerable phototoxicity by elevating intracellular ROS levels and diminishing cell viability, due to the production of free radicals under light stimulation [173]. They also affirmed that the light-induced generation of ROS arises from the electron-hole pair and, crucially, demonstrate that singlet oxygen is produced by photoexcited GQDs via both energy-transfer and electron-transfer mechanisms (Figure 7). Furthermore, following light stimulation, GQDs enhance the oxidation of non-enzymatic antioxidants and facilitate lipid peroxidation, hence adding to the light induced-toxicity of GQDs. Our findings indicate that GQDs exhibit antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties, contingent upon light exposure, which will inform the protective application and advancement of significant anticancer and bactericidal uses for GQDs.

![Figure 7

GQDs scavenging various free radicals. ESR spectra of DMPO/˙OH adducts were acquired using 20 μM Fe2+, 50 mM DMPO, 20 μM H2O2, 10 mM PBS buffer (pH 7.27), and various GQD doses after 1 min of incubation. GQD concentration affects ˙OH-scavenging activity. After 1 min incubation, 25 mM BMPO, 10% DMSO, 2.5 mM KO2, 0.35 mM 18-crown-6, 10 mM PBS buffer (pH 7.27), and varied GQD doses yielded ESR spectra of BMPO/˙OOH adducts. GQD concentration affects

O

2

⋅

−

{\text{O}}_{2}^{\cdot -}

scavenging. (e) Samples with 0.1 mM DPPH˙, 10 mM PBS buffer (pH 7.27), and varied GQD doses were used to generate ESR spectra. Data were taken 5 min after incubation. (f) GQD concentration affects DPPH˙-scavenging [173].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_007.jpg)

GQDs scavenging various free radicals. ESR spectra of DMPO/˙OH adducts were acquired using 20 μM Fe2+, 50 mM DMPO, 20 μM H2O2, 10 mM PBS buffer (pH 7.27), and various GQD doses after 1 min of incubation. GQD concentration affects ˙OH-scavenging activity. After 1 min incubation, 25 mM BMPO, 10% DMSO, 2.5 mM KO2, 0.35 mM 18-crown-6, 10 mM PBS buffer (pH 7.27), and varied GQD doses yielded ESR spectra of BMPO/˙OOH adducts. GQD concentration affects

Recent investigations have shown that GQDs are anti- and pro-oxidant. Their efficiency is poor. We present chlorine-doped GQDs (Cl-GQDs) with variable Cl doping and enhanced anti- and pro-oxidant activity. Cl-GQDs had 7-fold and 3-fold greater scavenging and free radical-produced efficiency than undoped GQDs [174]. The production of ROS from GQDs under light irradiation was validated by ESR spectroscopy. TEMP was chosen as a spin trap for singlet oxygen, capable of selectively reacting with 1O2. Upon the entrapment of 1O2, a stable compound, 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl, was generated, resulting in a distinctive ESR signal. Figure 8a demonstrates a pronounced ESR signal of TEMP in the Cl-GQDs-7.5V solution during irradiation. Furthermore, no ESR signal was seen in the control sample under dark conditions. The findings indicated that 1O2 might be produced by Cl-GQDs-7.5V under irradiation, consistent with prior studies. Upon photoexcitation, 1O2 was generated by energy transfer from the excited triplet state of the Cl-GQDs to the ground-state oxygen (Figure 8b). Furthermore, no

![Figure 8

(a) ESR spectra from Cl-GQDs-7.5V and TEMP samples with (black) or without (red) light. (b) 1O2 generating schematic [174].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_008.jpg)

(a) ESR spectra from Cl-GQDs-7.5V and TEMP samples with (black) or without (red) light. (b) 1O2 generating schematic [174].

Composite nanoparticles of naringenin-loaded β-cyclodextrin and CQDs were effectively synthesized. The findings indicated that the integration of CQDs not only augmented the antioxidant activities of nanoparticles but also boosted the encapsulation efficiency of naringenin. The creation of composite nanoparticles was validated by several characterization techniques. The zeta potential and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy results demonstrated that electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding are the predominant factors in nanoparticle formation. The X-ray diffraction experiment indicated that the naringenin-β-CD-CQDs nanoparticles are in an amorphous state, contrasting with the crystalline states of naringenin, β-CD, and the naringenin-β-CD inclusion complex. Ultimately, tests of antioxidant activity against DPPH, ABTS+, and Fe2+ chelating demonstrated that the resultant composite nanoparticles exhibited superior antioxidant activity relative to their individual components [175].

Leveraging the antioxidant properties of QDs, their use in neuroprotection seems particularly advantageous, especially regarding neurodegenerative illnesses driven by OS and acute traumas like SCI. By neutralizing ROS and modifying cellular antioxidant pathways, QDs mitigate oxidative damage and contribute to the stabilization of neuronal cell settings. This decrease in OS inhibits subsequent consequences such as apoptosis, inflammation, and mitochondrial malfunction, all of which are essential for neuronal survival and function. Moreover, the capacity of QDs to selectively target and concentrate in brain tissues has further benefits, as they may provide localized antioxidant effects exactly where required. The inherent antioxidant characteristics of QDs provide neuroprotective advantages, indicating their potential as therapeutic agents in SCI, traumatic brain traumas, and chronic neurodegenerative disorders.

3 Role of antioxidant QDs in neuroprotection

Antioxidant QDs have emerged as viable options for neuroprotection in SCI owing to their distinctive features that mitigate OS, a significant factor in cellular damage associated with SCI [49]. OS, characterized by excessive ROS and inadequate antioxidant defense, induces lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA damage, hence aggravating neuronal cell death, inflammation, and subsequent secondary injury [176]. Antioxidant QDs provide a precise method to reduce oxidative damage, perhaps interrupting this cycle and facilitating cellular healing and regeneration [177]. Doping QDs with sulfur, nitrogen, or cerium boosts their antioxidant ability, enabling these doped QDs to emulate natural enzymes like SOD and CAT, which neutralize superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide, respectively [178]. The capacity to precisely adjust these characteristics via controlled synthesis is a notable benefit of QDs compared to conventional antioxidants, enabling the creation of highly targeted therapeutic agents for SCI therapy.

Upon arrival at the injury site, antioxidant QDs demonstrate ROS-scavenging capabilities that mitigate OS in neuronal and adjacent glial cells [177]. The decrease in ROS levels may safeguard mitochondrial function, inhibit apoptosis, and diminish inflammation. Research indicates that by mitigating oxidative damage, QDs may preserve cellular homeostasis and promote the survival of neuronal and glial cells, essential for functional recovery after SCI [179]. Furthermore, the antioxidant activities of QDs are augmented by their photostability, allowing for prolonged protective effects without the rapid destruction characteristic of most small-molecule antioxidants [180]. In addition to directly neutralizing ROS, antioxidant QDs affect cellular signaling pathways, especially those associated with inflammation and apoptosis, including the NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways [181]. NF-κB, a principal modulator of inflammation, is often increased after SCI and facilitates the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, hence intensifying tissue damage. Antioxidant QDs may impede NF-κB activation, hence diminishing cytokine production and attenuating the inflammatory response [182]. Simultaneously, QDs stimulate the Nrf2 pathway, a principal regulator of antioxidant defenses, therefore enhancing cellular resistance to OS via the upregulation of endogenous antioxidant enzymes [183]. The combined mechanism of reducing inflammatory signals and enhancing antioxidant defenses makes QDs a versatile instrument in SCI treatment. Besides biochemical benefits, the diminutive size and extensive surface area of QDs enhance cellular absorption efficiency and enable possible conjugation with targeting ligands, hence facilitating targeted delivery to damage locations. Functionalizing QDs with chemicals that identify SCI-specific markers might provide a focused strategy, reducing off-target effects and enhancing neuroprotective effectiveness [184]. This trait is especially advantageous in neurodegenerative disorders such as SCI, when accuracy is essential to prevent damage to healthy, unaffected tissue [185]. The use of antioxidant QDs in neuroprotection remains nascent, with current research focusing on their biocompatibility and long-term safety. Although concerns about the toxicity of some classic QDs persist, new advancements in the production of non-toxic, biocompatible QDs have alleviated these dangers, facilitating their therapeutic use [186]. Future research aims to optimize QD formulations, enhance targeting mechanisms, and guarantee safe in vivo degradation. Due to their adaptability and diverse effects on OS and inflammation, antioxidant QDs provide substantial promise for improving neuroprotective techniques in SCI, providing optimism for increased recovery and functional restoration.

To discover new neuroprotective drugs, the pathophysiology and underlying molecular pathways must be examined. Numerous hypotheses have been proposed regarding the etiology of AD, including, but not limited to, the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) neurotoxic plaques, hyper-phosphorylated tau protein, OS, overactive microglial cells leading to inflammation, and downregulation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) [187]. AD is characterized by the activation of the amyloidogenic pathway, whereby the intracellular amyloid precursor protein is sequentially cleaved by β- and γ-secretases, resulting in the release of insoluble Aβ that accumulates and forms neurotoxic plaques. The deposition of Aβ activates microglial cells, triggers an inflammatory response, promotes the production of inflammatory mediators, and ultimately results in neuronal cell death [188]. Aβ has been shown to penetrate the mitochondrion, instigate OS, and generate ROS, resulting in mitochondrial malfunction, impaired ETC, dysregulated calcium homeostasis, and permanent cellular damage [189]. Aβ may also disrupt the production of CREB, a crucial protein for neural plasticity and memory formation and consolidation. CREB signaling also mitigates synapse loss induced by Aβ aggregation [190]. A different study sought to examine the molecular processes and neuroprotective properties of hyaluronic acid modified verapamil-loaded CQDs (VRH-loaded HA-CQDs) in an in vitro AD model caused by amyloid beta (Aβ) in SH-SY5Y and Neuro 2 a neuroblastoma cells [191]. Exposure to N-GQDs triggered ferroptosis in microglia via eliciting mitochondrial OS, but the ferroptotic effects elicited by A-GQDs were less pronounced under identical exposure conditions. This research will elucidate the mechanisms of GQDs-induced cellular damage across various forms of cell death and examine the impact of chemical modifications on GQDs’ toxicity [50]. The powerful environmental pesticide and weedicide paraquat is associated with neuromotor impairments and Parkinson’s disease (PD). We have assessed the neuroprotective function of citric acid-derived CQDs (Cit-CQDs) on paraquat-damaged human neuroblastoma-derived SH-SY5Y cell lines and on paraquat-exposed nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans). Our observations indicate that Cit-CQDs may scavenge free radicals in vitro and reduce paraquat-induced ROS levels in SH-SY5Y cells. Moreover, Cit-CQDs safeguard the cell line against paraquat, which would otherwise induce cell death. Nematodes challenged with Cit-CQDs exhibit improved survival rates 72 h after paraquat exposure in comparison to controls (Figure 9). Paraquat destroys dopamine (DA) neurons, leading to impaired locomotor activity in worms [192].

![Figure 9

CQDs reduce paraquat-induced neuronal damage in vitro and in vivo [192].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_009.jpg)

CQDs reduce paraquat-induced neuronal damage in vitro and in vivo [192].

Prion-like amyloids self-template to generate toxic oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils from their soluble monomers, a process associated with the initiation and progression of neurodegenerative diseases including AD, PD, Huntington’s, and systemic lysozyme amyloidosis. CQDs, derived from sodium citrate as a carbon precursor, were synthesized and described prior to evaluating their capacity to modulate amyloidogenic (fibril-forming) pathways. Hen-egg white lysozyme (HEWL) functioned as a model amyloidogenic protein [193]. A pulse-chase lysozyme fibril-forming experiment was established to investigate the influence of CQDs on the HEWL amyloid fibril formation, using ThT fluorescence as an indicator of mature fibril presence (Figure 10). The findings indicated that the Na–citrate-derived CQDs might interfere at various stages of the fibril-forming process by inhibiting the transformation of both monomeric and oligomeric HEWL intermediates into mature fibrils. Furthermore, the carbon nano material successfully dissolved oligomeric HEWL into monomeric HEWL and induced the disaggregation of mature HEWL fibrils.

![Figure 10

CQDs for the treatment of amyloid disorders [193].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_010.jpg)

CQDs for the treatment of amyloid disorders [193].

Another team of researchers presented a neuroprotective approach by encapsulating verapamil (VRH) into hyaluronic acid-modified CQDs and evaluating its efficacy against the free form in a rat model of AD generated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The experimental rats were categorized into seven groups: control, LPS, CQDs, early free VRH (FVRH), late FVRH, early verapamil CQDs (VCQDs), and late VCQDs [194]. The characterizations of VCQDs, the behavioral performance of the rats, histological and immunohistochemical alterations, certain AD hallmarks, OS biomarkers, neuro-affecting genes, and DNA fragmentation were assessed. VRH was effectively included into CQDs, as shown by the observed metrics. VRH demonstrated improvements in cognitive skills, alterations to brain architecture, reduced levels of Aβ and pTau, heightened antioxidant capacity, adjustable gene expression, and a reduction in DNA fragmentation. The administered treatment was more effective than the unbound medication. Furthermore, early intervention was superior than late intervention, corroborating the significance of the identified molecular targets in the progression of AD. VRH demonstrated several pathways in countering LPS-induced neurotoxicity via its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant attributes, therefore alleviating the characteristics of AD. GQDs and their nitrogen-doped counterparts exhibit excellent biocompatibility, as well as favorable optical and physicochemical features. GQDs have been thoroughly investigated due to several aspects, including their dimensions, surface charge, and interactions with other molecules present in biological environments [195]. This study succinctly clarifies the potential of electroactive GQDs and N-GQDs as neurotrophic agents. In vitro studies using the N2A cell line assessed the efficacy of GQDs and N-GQDs as neurotrophic agents, including fundamental assays such as the SRB test and neurite outgrowth assay. The findings derived from immunohistochemistry, confocal imaging investigations, and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses confirmed those obtained from the neurite outgrowth experiment. TuJ1 serves as a neuritogenic marker in both the central and peripheral nervous systems during the first phases of neural development. Mature, post-mitotic neurons arise from neuronal differentiation, necessitating certain molecular and morphological changes in progenitors (Figure 11). The monoclonal antibody TuJ1 indicates that neuron-specific β-tubulin expression starts during neurogenesis.

![Figure 11

Representative confocal pictures of N2A cells after G1 and G2 treatments. TuJ1, stained in green and blue, indicates DAPI, which has marked the nucleus; all photos are at 60× magnification with a scale bar of 10 μm [195].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_011.jpg)

Representative confocal pictures of N2A cells after G1 and G2 treatments. TuJ1, stained in green and blue, indicates DAPI, which has marked the nucleus; all photos are at 60× magnification with a scale bar of 10 μm [195].

A separate research demonstrated the neuroprotective properties of CQDs in a human microglial cell model generated by LPS. LPS was observed to elicit cytotoxicity, generate ROS, and promote pro-inflammatory cytokines, specifically interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α, while concurrently downregulating enzymatic antioxidants, including nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), SOD, CAT, heme oxygenase (HO)-1, HO-2, and glutathione peroxidase. In contrast, CQDs treatment mitigated LPS-induced cytotoxicity, stimulated anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, and transforming growth factor β), and enhanced enzymatic antioxidants at both transcriptional and translational levels [196]. Jia et al. documented N-doped carbon dot nanozyme (CDzyme) exhibiting remarkable antioxidant properties for the treatment of depression via the modulation of redox homeostasis and gut flora [197]. The CDzymes synthesized using microwave-assisted rapid polymerization of histidine and glucose demonstrate enhanced biocompatibility. Leveraging their distinctive structure, CDzymes may provide enough electrons, hydrogen atoms, and protons for reduction processes, in addition to catalytic sites that emulate redox enzymes. These collaborative processes confer upon CDzymes a wide-ranging antioxidant capability to neutralize ROS and reactive nitrogen species (˙OH,

![Figure 12

(a) Study of community barplots, (b) study of community heatmaps at the genus level, and (c) pathways at KEGG Path Level 2. (d) Rank sum test for amino acid metabolic pathways; (e and f) KEGG module abundance analysis of amino acid metabolism across four groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 denotes a statistically significant difference) [197].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2025-0211/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2025-0211_fig_012.jpg)

(a) Study of community barplots, (b) study of community heatmaps at the genus level, and (c) pathways at KEGG Path Level 2. (d) Rank sum test for amino acid metabolic pathways; (e and f) KEGG module abundance analysis of amino acid metabolism across four groups. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 denotes a statistically significant difference) [197].

Quercetin (Que) and p-phenylenediamine (p-PD) generated red-emitting CDs were manufactured using a one-step hydrothermal technique and intended as a new theranostic nano-agent for the multi-target therapy of AD. R-CD-75, with an improved formulation, demonstrated substantial suppression of Aβ aggregation and expedited depolymerization of mature Aβ fibrils (<4 h) at micromolar doses (2 and 5 μg/mL, respectively). Furthermore, R-CD-75 effectively scavenged ROS and exhibited enhanced red fluorescence imaging of Aβ plaques both in vitro and in vivo [199]. AD is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder marked by advancing cognitive and physical decline. Neuroinflammation is associated with AD, and the misfolding and aggregation of amyloid protein in the brain induces an inflammatory milieu. Microglia is the primary agents of neuroinflammation, and their aberrant activation triggers the release of several inflammatory chemicals, facilitates neuronal death, and results in cognitive deficits [200]. This work used microglial membranes with caffeic acid-coupled CQDs to create an innovative biomimetic nanocapsule (CDs-CA-MGs) for AD therapy. The nasal delivery of CDs-CA-MGs may circumvent the BBB and directly address the location of inflammation. Following therapy with CDs-CA-MGs, AD mice exhibited less brain inflammation, reduced neuronal death, and markedly enhanced learning and memory capabilities. The aggregation of Aβ peptides and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the brain is a pivotal mechanism contributing to AD, which disrupts neuronal signaling and induces neurodegeneration. According to current knowledge, preventing the buildup of Aβ peptides and NFTs is essential in the therapy of ADs [201]. Recent study indicates that nanoparticles may enhance medicine delivery across the BBB effectively. GQDs have been shown to be excellent inhibitors of Aβ peptide aggregation. The diminutive dimensions of GQDs facilitate their effortless traversal of the BBB. Additionally, GQDs have fluorescent features that may facilitate the in vivo detection of Aβ content. In recent years, the low cytotoxicity and good biocompatibility of GQDs, in comparison to other carbon materials, provide an advantage in their eligibility for clinical research on AD.

3.1 QD-based modulation of inflammatory responses

The control of inflammatory responses by QDs and CDs is a potential approach for addressing SCI, where excessive inflammation aggravates tissue damage and hinders healing [202]. In SCI, initial mechanical damage triggers a series of subsequent injury processes, with inflammation being a pivotal factor [203]. This inflammatory response, although initially helpful, often turns harmful as it extends tissue damage, disturbs cellular homeostasis, and triggers apoptotic pathways, resulting in neuronal death. Nanomaterials, including QDs and CDs, provide distinct benefits as they may be tailored to target and modulate certain inflammatory pathways, providing targeted and regulated anti-inflammatory actions that may alleviate secondary harm [204].

QDs, particularly those doped or functionalized with heteroatoms, such as nitrogen, sulfur, or cerium, have demonstrated significant antioxidant potential in biological settings, including in vivo models. For example, Yang et al. synthesized cerium-doped CQDs that exhibited strong ROS-scavenging ability in a rat model of SCI. The treatment reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and increased SOD activity, resulting in improved neuronal survival and reduced lesion volume [205]. In a separate study, Guo et al. reported that GQDs effectively attenuated OS in a transgenic mouse model of AD [51]. These QDs restored mitochondrial membrane potential, decreased intracellular ROS, and upregulated antioxidant enzymes such as CAT and glutathione peroxidase, ultimately improving cognitive function. Similarly, Luo et al. demonstrated that sulfur-doped carbon dots reduced ROS accumulation and inflammation in a murine model of IRI, contributing to decreased tissue necrosis and enhanced functional recovery [206].