Abstract

Water scarcity is a critical global challenge, underscoring the urgent need for efficient and sustainable desalination technologies with minimal brine disposal. This study introduces a novel solar water desalination approach using photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. The magnetic filler in the membranes serves three main functions: it maintains buoyancy at the air/water interface, captures particles to reduce contamination risks, and alters salt deposition on the membrane. A comprehensive analysis was conducted, including water contact angle measurements, light absorbance testing, and evaporation rates under natural sunlight. Additional characterization techniques, such as atomic force microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, thermogravimetric analysis, differential scanning calorimeter, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy-attenuated total reflection, were applied to both blank and photothermal membranes. Properties like mechanical strength, thickness, porosity, and surface roughness were systematically analyzed. The photothermal membranes were evaluated using a floating solar-driven desalination prototype, thermally analyzed via thermal imaging. The results showed that the iron–nickel alloy filler achieved over 90% light absorption and enhanced evaporation rates by up to 170% compared to blank membranes. Thermal imaging confirmed significant heat retention at the water surface, leading to higher evaporation rates. These findings highlight the potential of photothermal magnetic Janus membranes as a promising solution for sustainable desalination to combat global water scarcity.

1 Introduction

The availability of a sustainable and clean water supply is vital for life and plays a crucial role in the advancement of modern society. With 96.5% of the Earth’s water being salt water, the reliance on desalination technology has grown significantly. However, this technology has led to the generation of substantial waste brine as a byproduct, posing significant concerns regarding its environmental and ecological impact. The direct discharge of brine into the environment is particularly worrisome, especially considering the increasingly stringent environmental regulations and the increasing production of waste brine. Consequently, effective brine disposal faces significant challenges today [1]. The prevailing desalination technologies in the current market, such as reverse osmosis and multiple-effect evaporators, are unable to achieve Zero Liquid Discharge desalination directly due to inherent technological limitations or prohibitively high costs [2].

Solar water evaporation presents a promising alternative to desalination as it relies solely on renewable and eco-friendly solar energy, utilizing the vast resources of seawater to produce fresh water [3]. Unlike traditional desalination methods, solar evaporation eliminates the need for brine disposal concerns. However, conventional solar evaporation suffers from low evaporation efficiencies due to the placement of the solar absorber at the bottom of the water body [4]. In recent years, a promising advancement known as solar-driven interfacial evaporation has emerged as an alternative to bulk heating-based evaporation. This approach focuses on localizing the conversion of solar-thermal energy to the air/liquid interface, resulting in reduced thermal losses and improved energy conversion efficiency [5]. By optimizing the utilization of solar energy in this manner, the interfacial evaporation method holds great potential for enhancing the effectiveness of solar water evaporation for desalination purposes.

Solar-absorbing materials can be categorized as carbon-based [6], plasmonic-based [7,8] absorbers, or non-carbon-based materials, including (conjugated) polymers, such as perovskites and quantum dots [9,10], bio-inspired nanostructures [11,12], mushrooms [13,14,15], aerogels [16,17,18], hydrogels [19,20], and magnetic particles [6,21,22], that exhibit excellent solar absorption characteristics and find applications in solar energy technologies. To enhance light-to-heat conversion efficiency and facilitate interfacial evaporation, three-dimensional hierarchical structures such as membranes or foams incorporating photothermal materials have been developed. However, it is important to consider the impact of airflow, particularly in the presence of air blasts. The rate of solar interfacial evaporation is influenced by factors such as water temperature, evaporation area, and airflow rate. Previous research has predominantly focused on increasing the water temperature and expanding the evaporation area to enhance the solar interfacial evaporation process [23]. However, effectively managing the airflow rate has proven to be challenging, particularly concerning the interfacial floatability problem encountered with absorber membranes or foams under air blasts. From a practical perspective, maintaining stable floatability is crucial, given the presence of waves and winds in marine environments, especially when considering large-scale seawater evaporation and the utilization of numerous photothermal membranes over a significant area.

Janus membranes are an emerging class of materials having opposing properties at an interface. The Janus systems show great potential in many fields. For example, laser-induced graphene (LIG) film was treated unilaterally by oxygen plasma, forming a LIG/oxidized LIG (LIG-O) Janus membrane with distinct wettability on two sides that show a water evaporation rate of 1.512 kg m−2 h−1 by air flowing enhancement at 1 kW m−2 [24]. Also, photothermal evaporation devices based on the PVA/C/sponge composite were presented, and the evaporation rate highly increased from 1.56 to 5.90 kg m−2 h−1 for pure water evaporation and 1.43 to 4.47 kg m−2 h−1 for seawater evaporation under 1 sun illumination [25].

Janus photothermal desalination membranes are specialized materials designed for applications such as solar water evaporation and desalination. They feature two distinct surfaces with opposing properties: a hydrophilic surface in which one side attracts and absorbs water, facilitating its transfer to the evaporative area. It enhances the membrane’s efficiency in drawing water from a source. The opposite surface is hydrophobic, in which this side repels water and prevents the accumulation of salts or other impurities, reducing scaling and enhancing the membrane’s longevity. The unique dual surface design allows these membranes to effectively convert solar energy into heat, promoting water evaporation while minimizing the passage of salts. This makes them particularly useful for sustainable water purification and desalination processes. Li et al. applied a coat of poly(vinylidene fluoride)-co-hexafluoropropylene (PVDF-HFP or PcH) nanofibrous mat with photothermal and hydrophobic graphitic carbon spheres to the top surface. On the other hand, the bottom surface was coated with a hydrophilic polydopamine layer. This process created a novel Janus photothermal membrane (JPTM) with a distillation flux of 1.29 kg m² h⁻¹. This flux is ten times higher than that of the conventional unmodified PVDF-HFP or PcH membrane. The JPTM requires only 1 kW m² of solar illumination as the energy input [26].

Iron–nickel alloys, commonly known as ferro-nickel alloys, can indeed be used as absorbing materials in various solar thermal applications, including solar collectors and solar absorbers. In solar collector systems, the alloys are used to absorb solar radiation and convert it into heat, which can then be used for space heating, water heating, or other thermal processes [27,28]. The high thermal conductivity of iron–nickel alloys also facilitates efficient heat transfer within the collector system. It is important to note that the specific performance and suitability of iron–nickel alloys as solar-absorbing materials can vary depending on the specific application and operating conditions. Therefore, careful consideration of the alloy composition, surface treatment, and system design is necessary to achieve optimal solar absorption and overall performance in solar energy applications.

In recent years, solar-driven interfacial evaporation by localization of solar-thermal energy conversion to the air/liquid interface by using photothermal membranes/foams has been a promising alternative to conventional bulk heating-based evaporation, potentially reducing thermal losses and improving energy conversion efficiency. From the practical point of view, stable floatability of the used photothermal membrane/foam is very important because of the effect of waves and winds in the sea, especially for large-area sea water evaporation, and a large number/area of membranes would be employed.

In this work, the fabrication, characterization, and application of novel JPTMs for the solar desalination process are presented. The produced membranes exhibited high performance through their magnetic properties and their ability to surface evaporation driven by natural solar energy without generating salt water as a byproduct. The role of the magnetic filler in this study is threefold. First, it facilitates the buoyancy of the membrane on the air/water interface by incorporating a magnet within the desalination unit, which is engineered to function under airflow conditions. Second, it acts to capture any particles that may inadvertently escape into water, thereby mitigating the risk of contamination of the surface water. Furthermore, magnetization plays a pivotal role in inhibiting salt deposition on membrane surfaces by altering ionic interactions, enhancing particle mobility, and influencing crystallization dynamics. Collectively, these effects contribute to improved fouling resistance, which is crucial for sustaining the efficiency and longevity of membranes across various applications. The third aspect will be explored in greater detail in future work. In this study, iron–nickel alloys with different compositions were coated on the membrane surface by using a double casting of two layers: one layer is a blend of PcH and poly(ethersulfone) (PES) polymer dope, and the second layer is the iron–nickel alloy suspended in a solvent mixture, which was used in the polymer dope. The fabricated JPTMs show good absorbing frontside/surface and hydrophobic backside/surface. The fabricated alloys and JPTMs were characterized using different analysis techniques, including static water contact angle, light reflectometer, and evaporation rate under real sunlight. Moreover, the membrane tensile strength, thickness, porosity, and roughness were measured. Also, atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), differential scanning calorimeter (DSC), and Fourier transform infrared attenuated total reflection (FTIR-ATR) spectroscopy analyses, as well as water vapor transmission rate was determined for the fabricated blank and JPTMs. To achieve optimum performance and minimize heat transfer losses, the membranes should be in constant contact with the water surface. Therefore, the membrane was kept attached to the water surface throughout the experiments. The fabricated photothermal M1090 was tested using the fabricated solar-driven prototype under real solar radiation as an initial step for further modifications on the fabricated prototype and the obtained results as well as photothermal imaging of the prototype are presented.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The chemicals used for alloy synthesis include nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2·6H2O, 98%) and ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O, 99.99%) as sources of metal ions and were purchased from Sigma (Germany). Hydrazine hydrate (N2H4·H2O, 99%), a reducing agent, was obtained from Fisher (UK). The sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%) catalyst was purchased from Trading Dynamic Co. (TDC, Egypt). PES Ultrason E 6020P (glass transition temperature T g = 225°C and a molecular weight [M w] of 58,000 g mol−1) was obtained from BASF Chemical Company (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PcH) copolymer pellets (T m = ∼135–140°C according to ASTM D3418, Mw 214.06 g mol−1), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) (HPLC, 99.8%) and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) (>99% purity) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Distilled water was used as a solvent.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Iron–nickel alloy synthesis

Nanocrystalline filler samples of iron–nickel alloys were previously synthesized [29] as follows: aqueous solutions of iron and nickel salts of molar ratios 1:9, 2:8, 3:7, 4:6, and 5:5 were prepared in distilled water. The prepared solution was vigorously stirred on a magnetic stirrer equipped with a heating unit at 1,400–1,600 rpm and 95–98°C. The second solution of warm aqueous hydrazine, N2H4·H2O (99 wt%), and aqueous NaOH (0.1 M) with pH 12.8 was added to the first solution. The final fabricated black particles were separated magnetically, washed repeatedly with distilled water until neutral pH, and dried in a vacuum oven at 35°C for 24 h.

2.2.2 Preparation of alloy discs

The powders of alloys were compressed to a disc shape using compression tolls under a 9 ton load for 2 min compression time between two dyes made of stainless steel with a 1.3 cm diameter. Specac-U61904 equipment was used.

2.2.3 Fabrication of Janus membranes

The blend of PES and PcH polymer dope was prepared as described in previous work [30] by combining 18 wt% polymers, including less than 4 wt% PcH, dissolved in a solvent mixture of 1 NMP and 9 DMF. A homogeneous and viscous solution was obtained after 24 h of mixing at room temperature, and then 1 wt% lithium chloride was incorporated into the dope. The PcH/PES blend membranes were prepared by double casting method using a doctor casting knife adjusted at 350 µm. In a separate glass tube with a cap, 0.4 g of the magnetic alloys were initially dispersed in 5 mL of a mixture of solvents used in the polymer dope. Ultrasonication was employed at room temperature for 30 min to ensure proper dispersion. The dispersed alloys were dropped onto the surface of the cast PES/PcH film. The casting knife was then slid again, without changing its thickness, to coat the polymer film with a layer of the alloy. This casting process was completed within 1 min. Next, the coated membrane was immersed in 2.5 L of distilled water with 5 mL of ethanol/methanol at room temperature for 2 h. Finally, the prepared photothermal magnetic Janus membranes were dried at room temperature. Table 1 presents the composition and coded names of the fabricated membranes.

Coded name and the alloy composition used for the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

| Membrane code | Used alloy |

|---|---|

| Blank | Without alloy |

| M1090 | Fe10Ni90 |

| M2080 | Fe20Ni80 |

| M3070 | Fe30Ni70 |

| M4060 | Fe40Ni60 |

| M5050 | Fe50Ni50 |

2.2.4 Alloy and membrane characterization

2.2.4.1 Light reflectometer (absorbance %)

The spectral absorbance (A) was calculated as follows: Absorbance = 1 − (Reflectance + Transmittance). Opaque materials do not allow the transmission of light waves. Therefore, transmittance can be considered as zero, and the equation can be rewritten as Absorbance = 1 − (Reflectance). The reflectance of both the front and the back of the membrane samples was measured using three different incident angles (20°, 60°, and 85°) using a DR Lange REFO3 Reflectometer (Dr. Bruno Lange, GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany). The measurements of the six samples from two different membranes fabricated using independent membrane dopes for each iron–nickel alloy were averaged.

2.2.4.2 Temperature, humidity, solar power, and wind speed measurements

Digital thermohygrometers with LCD (humidity range: 25–95%, temperature range: 0–50.0°C, response time: 30 s; VWR, Dubai, United Arab Emirates), solar power meter (Tenmars TM-207, Taiwan), and Digital Anemometer (Benetech, GM8909, China) were used for measurements during the experiments. The solar power was measured at a horizontal position identical to the position of membrane samples.

2.2.4.3 Evaporation rate using real solar radiation

To determine the evaporation rate, both alloy discs and the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes were used. For the alloy discs, discs with a diameter of 1.3 cm were placed on the opening of graduated 10 mL glass cylinders (height 14.6 cm and diameter 1.3 cm), which were fully covered by insulating foam. When utilizing the membranes, circular membranes with a diameter of 3.8 cm were positioned on the opening of 25 mL glass beakers (height 4.9 cm and diameter 3.7 cm), also covered by insulating foam. To measure the evaporation rate, the cylinders or beakers were weighed before and after 3 h of exposure to the sunlight in Borg El Arab City, Alexandria, Egypt. To achieve the highest possible performance and minimize losses, the membrane should be floating over the water surface throughout the experiments. Hence, during the performance experiments, the water level was kept at a constant level to ensure that the membrane was fixed at a position in which it always had good contact with the water surface. The average of four evaporation values was measured on four different days within 2 weeks, and the standard deviation was calculated. Both 1,000 ppm water and simulated seawater (35,000 ppm) were used.

2.2.4.4 Membrane thickness

To determine the membrane thickness, ten measurements were taken at various points on three different membranes. A micrometer with a measurement range of 0–25 mm and a precision of 2 µm (manufactured by HDT, China) was used for the measurements. The average thickness was calculated, and the standard deviation was calculated.

2.2.4.5 Membrane surface roughness

The surface roughness of the membranes was measured using a surface roughness tester (SJ-201 P, Mitutoyo, Kanagawa, Japan). Prior to measuring the membrane roughness, the instrument was calibrated using a glass plate with known roughness. This calibration ensured accurate and consistent measurements. To assess the membrane roughness, nine measurements were taken on three different membrane samples. These samples were prepared from separate membrane dopes, each representing the same membrane composition. By taking multiple measurements on each sample, variations in roughness across different areas of the membrane could be accounted for.

2.2.4.6 Membrane tensile strength

Both the blank PES membranes and the Janus membranes were cut into a dumbbell shape for tensile testing. The length of each membrane was 37 mm, while the gauge length (the distance between the two narrow sections where the fracture occurs) was approximately 16 mm. The width of the membranes was 13 mm at the top and 7.2 mm at the middle, which served to induce fracture in the middle of the sample during testing. Tensile testing of the films was conducted using a Texture Analyzer T2 (Stable Micro Systems, Ltd., Surrey, UK). The testing was carried out at a constant crosshead speed of 0.1 mm s−1. Load–elongation curves were measured for five samples taken from two membranes prepared from two separate dopes for each membrane composition.

2.2.4.7 Static water contact angle

A Goniometer (model 500-F1), in conjunction with a video camera and image analysis software, was employed to measure the static water contact angle of the alloy discs and membrane samples. A 7 µL water droplet was placed on various locations of the alloy disc/membrane surface. The captured images were subsequently analyzed at successive time intervals, enabling estimation of the right and left contact angles using the image analysis software. The resulting values were averaged to determine the mean static water contact angle. For each alloy disc, eight readings were taken on three different samples (on both sides), whereas 20 readings were taken on three different membrane samples, and the reported value represents the average of these measurements.

2.2.4.8 Membrane porosity

The porosity (ε) of the membranes that were created was determined by measuring the weights of the membrane samples when wet and dry. To measure the wet weight, the membrane sample was immersed in absolute ethanol for 15 min and then weighed. After that, the sample was dried in an oven at 60°C for 24 h, and the dry weight was measured. The membrane porosity was calculated using the following equation:

where m w is the wet weight of the membrane (g), m d is the dry weight of the membrane (g), ρ e is the density of ethanol (g cm−3), and ρ p is the density of the polymer or polymer blend (g cm−3).

2.2.4.9 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging

The morphology of the fabricated membranes was analyzed by SEM (JEOL, Model JSM 6360 LA, Japan). SEM membrane samples were coated with Au before imaging. A voltage of 20 kV and a resolution of 1,280 × 960 pixels were used. Both the top and bottom, as well as the sample cross-section, were imaged.

2.2.4.10 Atomic force microscope (AFM) imaging

The membrane surface imaging was done using AFM (Model FlexAFM3). The scan area is 10 × 10 µm2, and the number of data points is 256 × 256 of 1 Hz scan rate. The AFM operated in contact mode using nonconductive silicon probes of Nanosurf (C3000; version 3.5.0.31 software, Liestal, Switzerland).

2.2.4.11 Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

TGA was conducted to study the thermal properties of both the blank PES/PcH and coated (Janus) membranes. The analysis was performed using a thermal gravimetric analyzer (Shimadzu TGA-50, Nishinokyo Kuwabara-Cho, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan). The samples were subjected to a temperature scan ranging from 25 to 900°C, with a heating rate of 10°C min−1. The analysis was carried out under a flow of nitrogen gas to prevent any oxidation or combustion of the samples.

2.2.4.12 Differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) analysis

The fabricated membranes were analyzed using a DSC(model DSC-200PC, NETZSCH, Gebrüder-Netzsch-Straße 19). The measurements were carried out at a heating rate of 10°C min−1. The samples were subjected to a temperature range from 25 to 900°C under a nitrogen flow rate of 30 mL min−1. The glass transition temperature (T g) was determined as the temperature at which a change in the heat capacity during the heating cycle was observed.

2.2.4.13 Fourier transfer infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) analysis

The FTIR-ATR analysis was performed on the fabricated membranes using a platinum ART sampling holder (Alfa II-Bruker spectrophotometer, Germany). The analysis was conducted in the wavelength range of 400–1,800 cm−1.

2.2.4.14 Water vapor transmission rate

A GBI W303 (B) Water Vapor Permeability Analyzer (China) was used for the evaluation of the water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) via the cup method. The water vapor transmission rate was calculated by measuring the amounts of water vapor transferred through a unit area of the film in a unit time below the exact conditions of temperature (38°C) and humidity (4%) as stated by the subsequent standards (ASTM E96). WVTR is the water vapor transmission rate through a film (g water · m−2 day−1).

2.2.4.15 Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) analysis

A VSM (Lake Shore 7410, USA) was used to measure the room-temperature magnetic properties of the nanostructured iron–nickel alloys and the fabricated blank PES and magnetic Janus membranes. The applied field was −20 ≤ H ≤ 20 kOe. For magnetization measurements, the membranes were tied and fixed in a small cylindrical plastic holder between the magnetic pools.

2.2.4.16 Solar-driven floating prototype evaluation under real solar radiation

The fabricated photothermal membrane was tested using a prototype that was designed and manufactured to achieve sustainable water desalination by efficiently harnessing solar energy. The design features a double-sided solar still with an internal chamber made of acrylic, providing both strength and lightweight characteristics, as shown in Figure 1a. It also includes an efficient sliding mechanism for collecting condensed water. The assembly incorporates a locally manufactured photothermal membrane installed at the bottom of the chamber, which concentrates solar radiation on the water surface. The effective membrane area is 0.053 m2. Additionally, as shown in Figure 1b, the prototype is notable for its ability to maintain buoyancy on the water’s surface due to its floating design. Once the operation and optimization of the prototype commenced, the productivity was determined as an average from three separate experiments, each lasting 3 days (for a total of 9 days per membrane). In each experiment, two prototypes were utilized: one with a non-thermal blank membrane and the other with the photothermal membrane, in addition to testing the prototype without a membrane. The used salinity was averaged 600 ± 50 ppm.

(a) Schematic diagram for the designed solar-driven floating prototype, and (b) the prototype testing using the blank and the photothermal M1090 membrane under real solar radiation.

3 Results and discussion

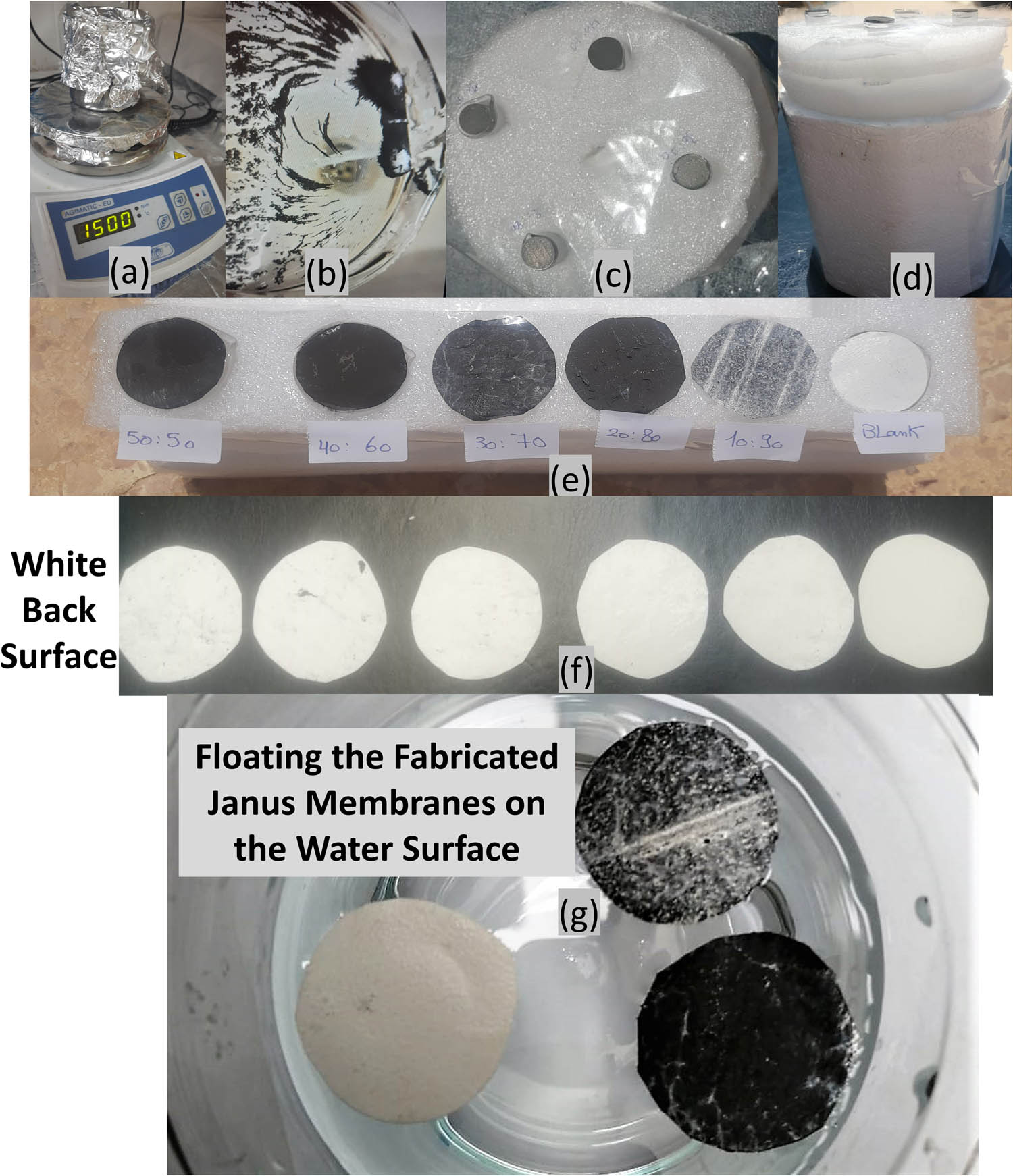

Several factors can influence the specific heat capacity of iron and nickel, including the crystal structure, impurities, and environmental temperature. In this study, nanostructured iron–nickel alloys were synthesized using a straightforward reduction method, as described previously [30] and shown in Figure 2(a). During the washing process, the resulting alloys/solar absorbents were collected by taking advantage of their magnetic affinity, as shown in Figure 2(b). To assess the capacity of the synthesized iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents for harnessing solar energy and utilizing it to generate heat for water evaporation. For that, the alloy powder was compressed into discs with a diameter of 1.3 cm with an approximate thickness of 0.6 ± 0.1 mm for alloys/solar absorbents up to 20% iron and 1.3 ± 0.3 mm for alloys/solar absorbents from 30 to 50% iron for using the same amount and same pressure for compressing. As illustrated in Figure 2(c) (plain view) and Figure 2(d) (side view) of compressed alloys/solar absorbents used in the determination of the evaporation rate under real sunlight. Figure 2(e) depicts the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes that were fabricated and placed under direct sunlight during the evaporation experiment, along with their white back surfaces shown in Figure 2(f). The ability of the fabricated membranes to float on the water surface (Figure 2(g)) and their attraction toward the magnet were also confirmed.

Photographs of the (a) synthesis of the iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents, (b) alloys/solar absorbents in washing steps, (c) and (d) solar absorbents’ discs during the evaporation experiment under direct sunlight, (e) the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes under direct sunlight during the evaporation experiment and their white back surfaces (f), and the floating test of the fabricated membrane on the membrane surface (g).

Table 2 presents the specific heat capacity of iron, which is lower than that of nickel, especially at high temperatures. Therefore, when selecting materials for their absorbing properties, it is crucial to consider a combination of factors, including the absorption coefficient, optical properties, and specific heat capacity, rather than relying solely on specific heat capacity.

| Specific heat capacity at | Iron | Nickel |

|---|---|---|

| 25°C [J g−1 °C−1 or (cal g−1 °C−1)] | 0.45 (0.105) | 0.44 (0.105) |

| 100°C | 0.55 (0.107) | 0.49 (0.117) |

| 500°C | 0.55 (0.131) | 0.62 (0.148) |

| 1,000°C | 0.61 (0.146) | 0.66 (0.158) |

The prepared discs exhibited two distinct surfaces that were discernible to the naked eye: a shiny surface and a matte surface. It is noteworthy that the contrast between the shiny and matte surfaces diminished as the nickel content in the alloy decreased. During the evaporation experiment, the matte surfaces of the alloy discs were exposed to direct sunlight.

To determine the change in temperature of the alloys/solar absorbents when exposed to sunlight, measurements were conducted on three different days, and the data obtained were averaged and presented in supplementary information files (Figure S1). The real solar radiation measurements of 975, 1,082, 952, and 808 W m² after 30, 60, 120, and 300 min of testing were conducted from 10 AM to 3 PM. Overall, all the alloys demonstrated the ability to convert sunlight into heat, as evidenced by the observed temperature increase over time at an ambient temperature of 28 ± 5°C. Upon closer analysis of the temperature changes, it was noted that alloys containing up to 30% iron exhibited a slightly slower rate of temperature increase, with fewer fluctuations when subjected to airflow. Conversely, alloys with an iron content exceeding 30% experienced a faster temperature increase but also demonstrated more rapid heat dissipation to the surrounding environment, particularly when exposed to airflow at approximately 1.2 ± 0.6 m s−1.

3.1 Evaporation rate: Alloy/solar absorbent disc vs photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

It is important to consider alloy/solar absorbent discs. However, they demonstrate the ability to convert sun radiation into heat and facilitate evaporation; the evaporated water will escape into the atmosphere through the pores in the used cylinders. Additionally, the presence of the polymer material in the membranes can contribute to reducing the transfer of heat from the front black surface to the back white surface. This is because the thermal conductivity of plastic materials such as PES and PcH can vary depending on different factors such as thickness and specific formulation. However, as a general guideline, the thermal conductivity values of PES and PcH membranes are typically in the range of 0.1–0.3 and 0.13–0.19 W m−1 K−1 [33], respectively. For that, the membrane materials act as an insulator that will reduce the heat transfer from the membrane surface to the membrane back (i.e., the water surface).

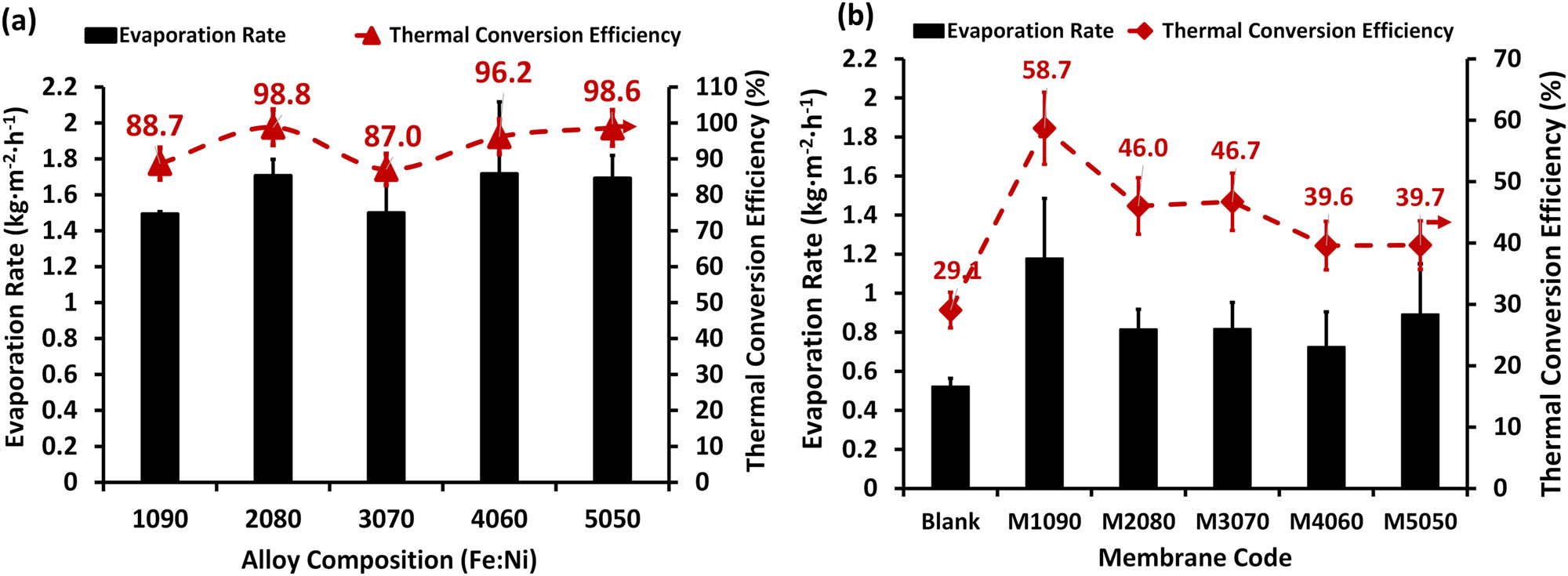

As shown in Figure 3, the water evaporation rates using alloys/solar absorbent discs are relatively higher (around 1.8 ± 0.2 kg m2 h−1) compared to the water evaporation rates using photothermal magnetic Janus membranes (around 1.0 ± 0.2 kg m2 h−1). Also, the thermal conversion efficiency is very high (up to 98%) for the alloys/solar-absorbent discs compared to about 58% for the Janus membranes. Adding iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents on the membrane surface increased the evaporation rate up to 170% using the M1090 membrane more than the blank polymeric membrane. However, it is not the darkest membrane. In other words, this configuration had the least ability to impede or obstruct heat flow through the membrane cross-section. Many factors affect the evaporation rates, as discussed in the following sections.

Evaporation rates and thermal conversion efficiency using 1,000 ppm saline water for (a) alloy/solar-absorbent discs and (b) the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. The standard deviation was computed and included in the columns.

3.2 Thickness and tensile strength of the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

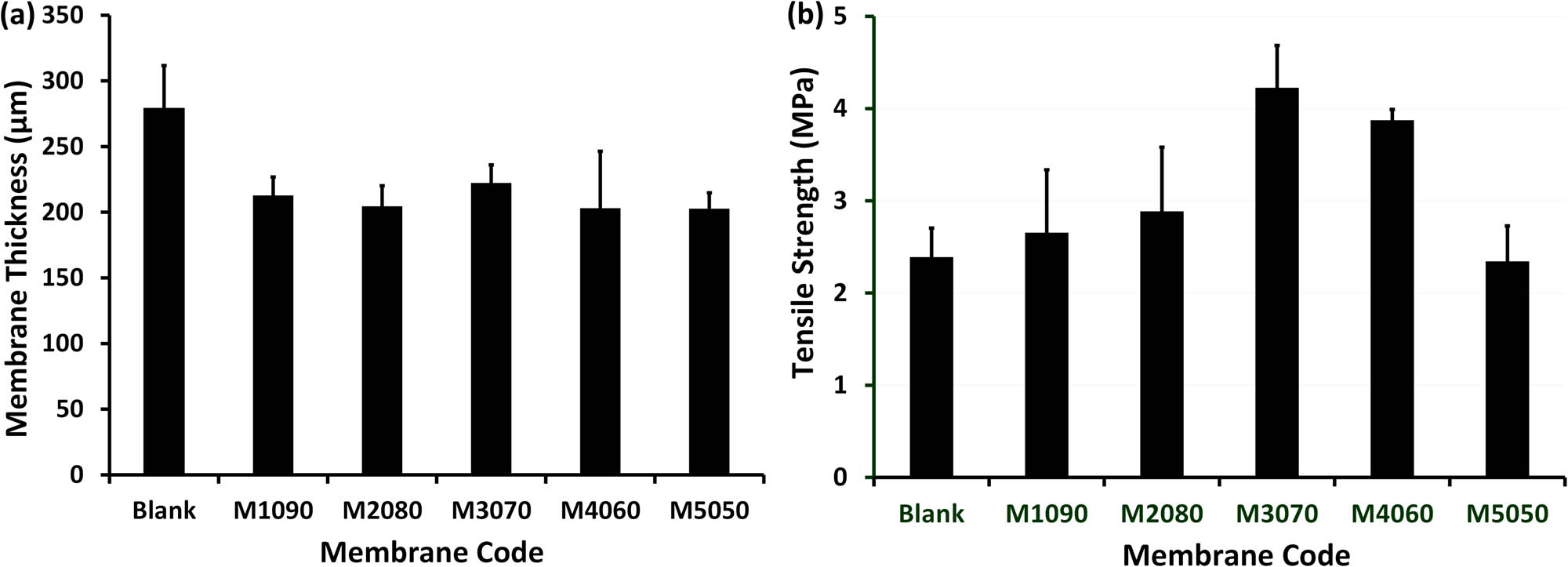

The initial as-casting thickness of all the produced membranes was set to 350 µm, and after the coagulation process, a reduction in thickness of approximately 28% ± 2 was observed in the photothermal membranes compared to the blank ones (Figure 4a). The application of iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents on the membrane surface resulted in the compression of the membrane thickness, as depicted in Figure 4a, potentially contributing to an enhanced evaporation rate compared to the blank membrane. The observed variations in the effects of the iron–nickel/solar absorbents used are likely attributed to their microstructure and shape, which in turn influence their position and distribution on and within the membrane pores. For instance, the starfish-like iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents with protruding tips exhibited diffusion across the membrane cross-section, while numerous necklace-like-shaped iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents were predominantly located on the upper surface of the membrane; see the SEM in membrane microstructures section. Additionally, the presence of iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents with shapes that penetrated deep into the membrane pores contributed to enhancing the membrane strength, as depicted in Figure 4b, albeit showing a reduced effect in the case of significant aggregation in the M5050 photothermal membrane.

The thickness (a) and tensile strength (b) of the fabricated membranes. The standard deviation was computed and included in the columns.

3.3 Surface hydrophilicity of the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

Figure 5 depicts the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes that exhibit a hydrophobic front surface, which is black, while the back surface displays relatively lower hydrophobicity. The disparity in hydrophobicity arises due to the roughness of the membrane, which will be elaborated on in subsequent sections. It is important to highlight that the M1090 membrane demonstrates the highest static contact angle, even though the alloy discs shown in Figure 5a are not the most hydrophobic. This can be attributed to the influence of membrane roughness on hydrophobicity. The roughness of a membrane can modify the available surface area for water interaction and affect the ability of water molecules to wet the surface. A rough surface with irregularities can enhance the hydrophobic properties of the membrane by minimizing the contact between water droplets and the surface. This leads to higher contact angles and increased hydrophobicity. Moreover, this observation suggests a synergistic effect between the addition of the alloy/solar absorbents and the membrane material used. This indicates that a significant portion of the alloy/solar absorbents, located beneath the front surface of the membrane, possesses tips on its front surface.

The static water contact angle changes on (a) both matt and shiny surfaces of the alloy/solar absorbent discs, and (b) the front black and white back surfaces of the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes, the slandered deviation was computed and included in the columns.

3.4 Surface roughness of the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

The uneven texture of the membrane surface can serve as a useful method to enhance the rate of evaporation from the treated surface. This is illustrated in Figure 6, where it can be observed that the M1090 membrane exhibits the greatest roughness on its front surface, which progressively diminishes as the iron content in the alloy increases. The pronounced roughness can be attributed to the starfish-shaped tips of the Fe10Ni90 alloy [29]. Remarkably, this finding aligns perfectly with the observation that the M1090 membrane displays the highest evaporation rate despite its comparatively less intense black coloration in comparison to the other prepared membranes.

Surface roughness of different fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. The black block is the front black surface and the empty block is the back white surface. The average of ten measurements from three membranes was calculated, and a standard deviation bar was added to each block.

As depicted in Figure 7, the tips of the alloy are observed on the surface of the membrane, and a significant portion of the alloy is obstructed across the cross-section of the membrane. Consequently, this leads to a decrease in the darkness of the surface and the lowest peak height, referred to as S p. However, the average roughness (S a), which quantifies the average deviation of the surface profile from the mean line within a given sampling length, does not exhibit substantial variations among the different alloys. In contrast, a considerable amount of alloy covers the surface, and the alloys range from 20 to 50% iron content. This results in the highest value of S y (10 µm), which represents the vertical distance between the highest peak and the lowest valley within the sampling length.

AFM imaging of the front black surface of different fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. S a is the average roughness, S p is the peak height, and S y is the peak-to-valley height; the scale is 10 µm × 10 µm.

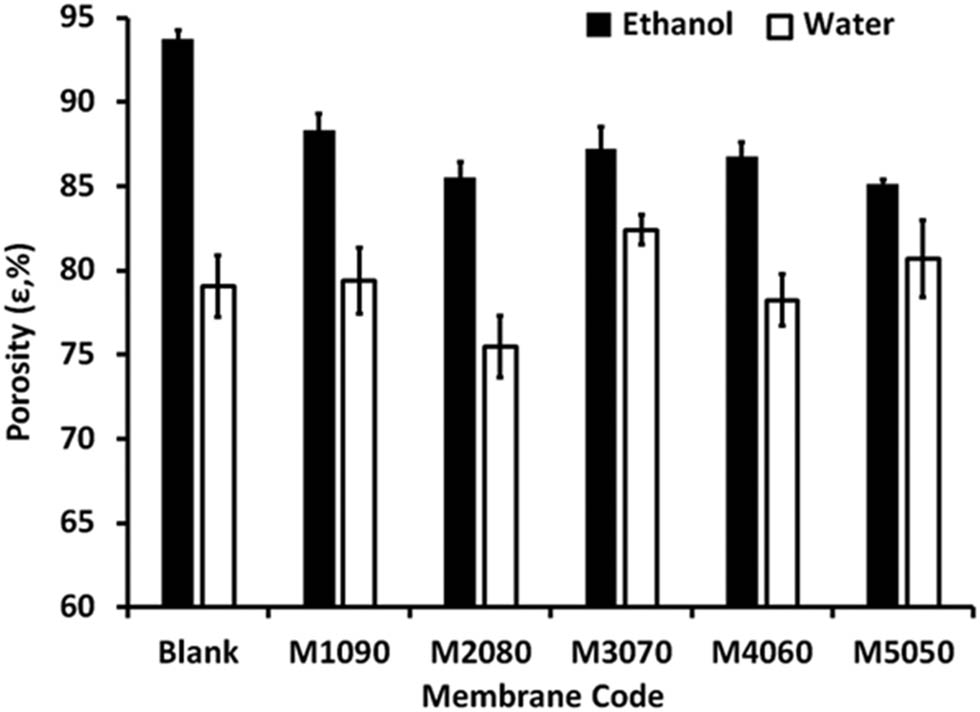

3.5 Membrane porosity

The presence of iron–nickel alloy/solar absorbent on the membrane surface has a detrimental effect on membrane porosity, which is influenced by the thickness and shape of the alloy/solar-absorbent layer. When ethanol was used to determine the bulk porosity, it was observed that all the membranes had lower total bulk porosity than the blank one, as shown in Figure 8. However, the different shapes of the alloys/solar absorbents used had varying effects. The fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes exhibited a slightly lower bulk porosity than the blank, likely due to the arrangement of the iron–nickel alloy/solar adsorbent predominantly located on the membrane surface. In addition, the aggregation of the used alloys/solar absorbents inside the membrane pores.

Membrane porosity of different fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes using ethanol and water (black and white blocks, respectively). The standard deviation was computed and included in the columns.

3.6 Photothermal magnetic Janus membrane microstructures

The SEM images presented in Figure 9 provide insights into the structure of the fabricated membranes. The images reveal that the alloy exhibits a starfish-like iron–nickel alloy/solar-absorbent shape, with its tips appearing to be embedded within the cross-section of the membrane, while a portion of it is situated on the membrane surface. This unique configuration contributes to the formation of more open pores on the membrane surface. The presence of these tips on the membrane surface creates additional openings through which water can evaporate, as shown in Figure 9 (M1090 (b)). The open pores act as conduits for the evaporation process, potentially enhancing the efficiency of water evaporation. In contrast, the other particles, namely M3070, M4060, and M5050, which also have an iron–nickel alloy/solar-absorbent shape, primarily concentrate their weight on the membrane surface and fill the mouth of membrane pores. This configuration results in less coverage of the photothermal membrane surface by the polymer, making it darker and more capable of absorbing light. However, the closed membrane pores in these particles restrict the rate of water evaporation, as depicted in Figure 9b (M3070 to M5050). Overall, the starfish-like iron–nickel alloy/solar-absorbent shape observed in the SEM images promotes the formation of open pores on the membrane surface, potentially facilitating water evaporation. In contrast, the other configurations of the particles concentrate weight on the membrane surface and block the membrane pores, thereby reducing the rate of water evaporation. Closed membrane pores create a barrier that hinders the escape of water molecules in the form of vapor. Water evaporation typically occurs when water molecules at the surface gain enough energy to break free from the liquid phase and enter the gas phase. However, when membrane pores are closed, the water vapor generated within the membrane is trapped, limiting its ability to escape into the surrounding environment.

SEM imaging of the front black surface of different fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. (a) and (b) front black surfaces at 1,000× and 10,000×, respectively, (c) membrane cross-section at 200×, and (d) back white surface at 10,000×.

Moreover, Figure 9c for M1090 reveals a sponge-like porosity that exhibits a greater degree of homogeneity and continuity across both the front and back surfaces, particularly in comparison to other photothermal membranes. This architectural feature is indicative of an alloy/solar absorbent resembling alloy/solar absorbent distributed throughout the cross-section, with a significant concentration located beneath the membrane, as shown in Figure 9d depicting the back surface. The interplay between filler distribution throughout the membrane thickness and its aggregation on the surface is paramount in determining water evaporation efficiency. A uniform distribution of alloy/solar absorbent within the membrane thickness not only augments the overall structural integrity but also expands the surface area available for water interaction. This uniformity enhances thermal conduction, thereby promoting more effective heat transfer to water molecules and accelerating evaporation rates. Conversely, when alloy/solar-absorbent aggregates on the membrane surface, they may introduce localized hotspots or barriers that disrupt the thermal profile’s uniformity. Although such surface aggregation can enhance specific surface properties, it may concurrently obstruct the evaporation process by diminishing the effective area for water contact and restricting the membrane’s uniform heating. Ultimately, a well-distributed alloy/solar absorbent within the membrane significantly boosts water evaporation efficiency by maximizing heat transfer and minimizing thermal gradients. In contrast, aggregated fillers at the surface can impede this process. Consequently, the observed high evaporation rate of M1090, despite its comparatively low blackness, aligns with its distinctive microstructure, characterized by high magnetization and attraction throughout the membrane cross-section, notwithstanding the aggregation present on the surface.

3.7 Light absorbance (%) of photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

When the membrane is positioned on the water surface, an interesting phenomenon occurs: sunlight undergoes a 180° rotation in relation to the membrane. As a result, the angle at which sunlight is absorbed by the membrane varies, as shown in Figure 10. This variability in absorption angles has a significant impact on the amount of sunlight captured. For example, when sunlight strikes the membrane at a 20° angle, a large proportion of the light (approximately 90%) is absorbed. This high absorption is due to the cosine of 20°, which equals 0.9. On the other hand, the lowest absorption occurs when sunlight hits the membrane at an 85° angle, with a cosine value of 0.09. The variations in light absorption by the blank white membrane are depicted in Figure 10. However, the specially designed photothermal magnetic Janus membranes exhibit consistently high light absorption rates (over 95%) regardless of the incident angle. Unlike the blank white membrane, these fabricated membranes have been engineered to possess superior light absorption properties. The resulting high absorption levels ensure efficient utilization of sunlight for various applications. The placement of the membrane on the water surface causes sunlight to rotate 180° relative to the membrane, leading to varying angles of light absorption. While the absorption of the blank white membrane fluctuates depending on the incident angle, the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes consistently exhibit exceptional light absorption rates (over 95%) across all angles.

Light absorption (%) on the two membrane surfaces of the blank and photothermal magnetic Janus membranes: (a) front and (b) back surfaces using three different light incident angles: 20°, 60°, and 85°.

3.8 Water vapor transmission rates of photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

Table 3 provides information on the WVTR from the white surface at the back of the membrane to the black photothermal surface at the front. This transmission rate indicates the ability of the relevant materials to allow the transfer of hot water vapor from underneath the membrane to the top surface. In essence, it measures the permeability of the membrane from the water surface on the back. The measurements were taken at a relative humidity of 4% and a temperature of 38°C under atmospheric pressure. The results in Table 3 demonstrate that when the membrane is coated with iron–nickel alloys/absorbents, there is a slight reduction (up to 15% when using M2080) in the membrane’s ability to transmit water vapor from the back surface. However, this reduction is minimal. Additionally, there is almost no change observed when using other membranes with particles of different shapes (such as M3070, M4060, and M5050). This finding aligns well with the evaporation rate of the membrane when exposed to real solar radiation, as discussed in the previous section. Table 3 shows that the addition of iron–nickel alloy/solar absorbents on the membrane surface has a minimal impact on the water vapor transmission rate from the back surface of the photothermal membrane. This result is consistent with the evaporation rate observed when the membrane is exposed to real solar radiation, reinforcing the agreement between experimental findings.

Water vapor transmission rates from the back to black photothermal membrane

| Membrane code | WVTR (g m2 day−1) |

|---|---|

| Blank | 1574.3 |

| M1090 | 1426.0 |

| M2080 | 1331.7 |

| M3070 | 1589.9 |

| M4060 | 1587.7 |

| M5050 | 1599.1 |

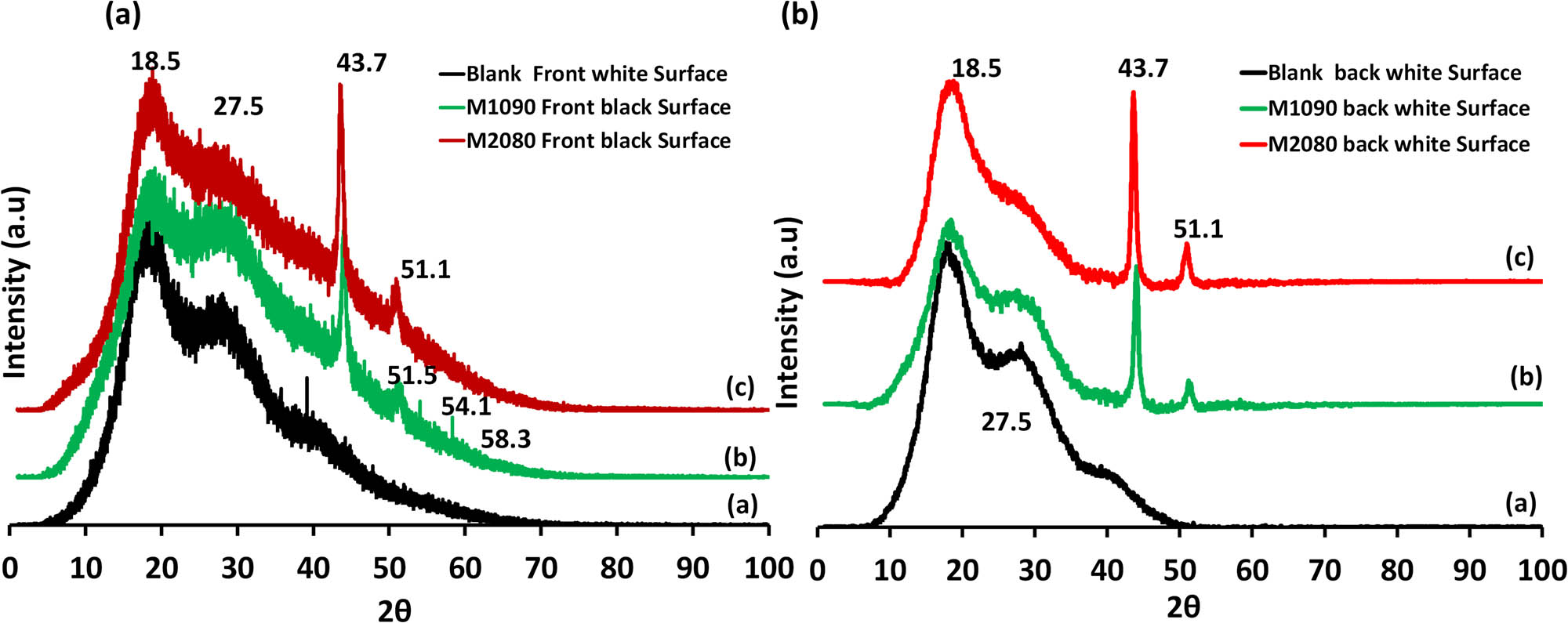

3.9 X‑ray diffraction (XRD) of photothermal magnetic Janus membranes

Figure 11 illustrates the results of XRD, revealing several distinct peaks. The presence of a broad peak at approximately 18.5° indicates the characteristic of the PES polymer, while another peak at 27.5° signifies the presence of the PcH polymer. Additionally, sharp peaks at 43.7°, 51.1°, 54.1°, and 58.1° correspond to the crystalline face-centered cubic (fcc) structure of the iron–nickel alloys [37,38]. The front surface, coated with the iron–nickel alloy (Fe10Ni90), exhibits prominent alloy peaks with high intensity, while the back surface is primarily dominated by polymeric peaks.

XRD patterns of the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes: (a) front black surface and (b) back white surface.

3.10 Membrane thermal analyses

Figure 12 shows the thermal analyses of the blank and the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. The initial weight loss below 200°C was determined to be caused by the removal of moisture and/or solvent, which accounted for less than 2–8% of the total weight. The polymer blend exhibited the onset of initial decomposition at approximately 400°C, followed by a second thermal degradation step at around 480°C. This could be attributed to sulfur dioxide cleavage and ether bond cleavage. At higher temperatures, the second thermal degradation stage initiated at around 510°C, leading to the decomposition of the backbone (benzene ring) [34,35,36]. At 900°C, approximately 28 wt% of the material remained, as shown in Figure 12a, line a. The melting point of iron–nickel alloy is approximately 1,420°C; consequently, the coated fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes remained undecomposed, as shown in Figure 12a (lines b and c), with approximately 44.5 and 71.3 wt% of the initial weight remaining for M1090 and M2080, respectively. The difference in the wt% remaining after 900°C is related to the average iron–nickel alloy loaded on the membrane per cm in which most of the alloys is loaded on the membrane surface for M2080 (3.23 mg cm2), whereas part of Fe10Ni90 impeded inside the membrane cross-section by the effect of its high magnetization and dragging with the casting knife (2.54 mg cm2) although in both membrane 0.4 g alloy/solar absorbents was used.

TGA of (a) the blank (black line a) and the photothermal-magnetic Janus membranes; M1090 and M2080 (red line b and blue line c), respectively, and (b) DSC of the blank and M1090.

Figure 12b illustrates the DSC heating scans of the blank and the fabricated photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. The PcH and PES polymers display glass transition temperatures (T g: onset temperature) at 133 and 237°C, respectively [30,36], indicating the melting of its crystalline phase. In full agreement between TGA and DSC, the variations observed in the peak shapes of the prepared membranes can be attributed to the presence of defective crystals in different crystalline phases within the blank blend polymeric membrane. The degradation temperature starts at around 480–600°C. For lithium chloride, the residual in the blend polymer showed peaks that may be attributed to the melting point being relatively high, at around 613°C. Iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents can undergo various phase transformations, such as martensitic transformation or austenitic transformation. These transformations may be accompanied by peaks in the DSC curve, indicating the energy associated with the phase change as shown in lines a and c.

The FTIR-ATR analysis of the front black surface and back white surface of both the blank and photothermal magnetic Janus membranes are shown in Figure 13. The PVDF polymer, which is the backbone of the PcH co-polymer, consists of five different polymorphs: α (phase II), β (phase I), γ (phase III), δ, and ε [36]. Figure 13a shows that the characteristics observed at 1,480–1,579 cm−1 can be attributed to the stretching of the –C–F– bond. Additionally, peaks at 873 and 1,150 cm−1 indicate the presence of the –CF2– group. Similarly, the peaks around 1,108 cm−1, 837–870 cm−1, and 719 cm−1 correspond to the skeletal vibration of –C–C–, the vinylidene group, and the –CH2– bonding, respectively. Therefore, all the peaks, including those at 719, 870, and 1,150 cm−1, can be associated with the stretching of the –CF3– group. Peaks at 555, 719, 870, 1,012, and approximately 1,298 cm−1 are assigned to the non-polar α crystals (phase II). The β crystal (phase I) is linked to absorptions at 837, 1,241, and 1,483 cm−1, while the peak at 1,239 cm−1 is characteristic of the γ crystal (phase III) of the PVDF backbone of the PcH co-polymer. The distinctive peaks of the PES polymer observed in the FTIR spectrum are aromatic C–H stretching at 3,071 and 3,104 cm−1, benzene ring stretching at 1,577 and 1,485 cm−1, and the S═O bands at 1,298 and 1,149 cm−1. Common vibrational bands were noticed in both charts (Figure 13a and b) that depicted the polymeric membranes. Figure 13b shows that a new band appears at 1,186 cm−1, and the band at 674 cm−1 nearly disappeared with the addition of iron–nickel alloys on the Janus membrane’s front surface. Also, there is a noticeable decrease in the intensities of all bands with the addition of iron–nickel alloy/solar absorbents.

FTIR-ATR analysis of (a) front black surface and (b) back white surface of the photothermal-magnetic Janus membranes. The blank membrane (black line a) and photothermal-magnetic Janus membranes, M1090 and M2080 (red line b and blue line c), respectively.

The magnetization–magnetic field (M-H) hysteresis loops of the blank PES membrane and the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes are shown in Figure 14a. The photothermal magnetic Janus membranes exhibit an S-shaped hysteresis curve, which indicates their magnetic properties. In contrast, the blank PES membranes do not form a clear S-shaped hysteresis loop. Figure 14b demonstrates that the coercivity of the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes is significantly higher than that of the blank PES membrane, showing almost a 100% improvement. This property suggests that the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes maintain a strong affinity to magnets, which may help ensure the stability of the membrane when subjected to high airflow.

(a) The M-H hysteresis loops and (b) coerceivity (Hc; emu g−1) of the bank PES/PcH and the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes.

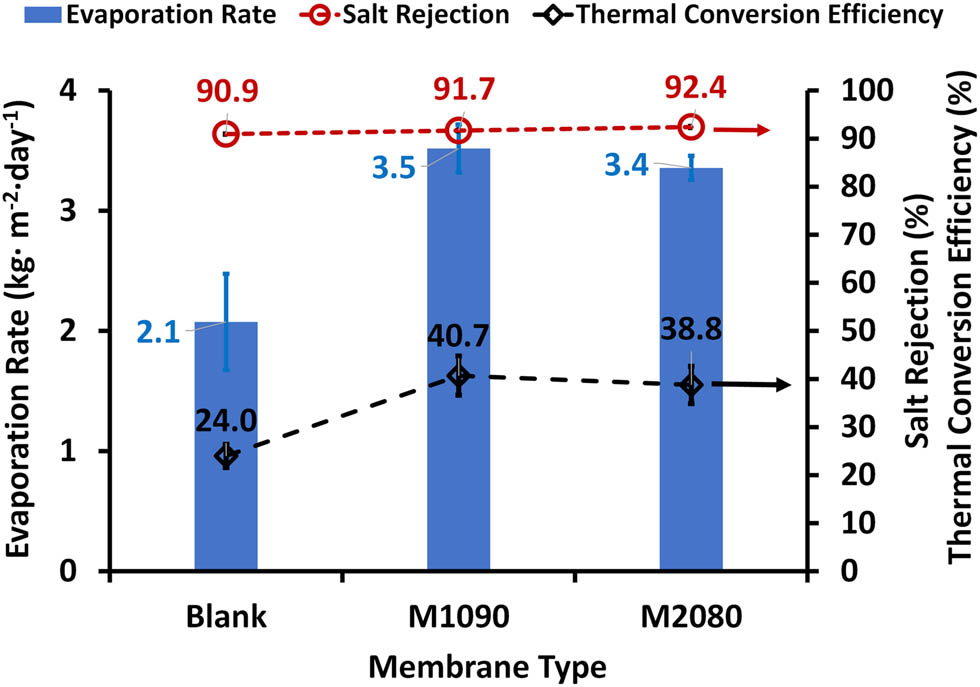

3.11 Membrane evaluation under real solar radiation and using simulated seawater

Based on the preceding characterization, photothermal membranes, in addition to the control membrane, were evaluated using insulated beakers and simulated seawater (35,000 ppm). Testing was conducted on three separate days in August 2024 (average solar radiation is 1,000 W m−1 and average temperature 35°C), and the results were averaged. The evaporation rate increased from an average of 2.1 ± 0.4 kg m² day⁻¹ for the blank membrane to 3.5 ± 0.2 kg m² day⁻¹ for M1090 and 3.4 ± 0.1 kg m² day⁻¹ for M080, respectively. The rejection rate remained approximately 91%, which can be attributed to the employed beaker with limited volume capacity. Also, it can be noticed that the thermal conversion efficiency increased from about 24% for the blank membrane to about 40% for the M1090, which means that the efficiency values decreased compared to those when using 1,000 ppm salt water. This is expected due to the fact that the presence of salt decreases the water flux through the membrane.

Furthermore, upon completion of the prototype construction, both the control and M1090 membranes were utilized to assess the productivity of the prototype. The productivity levels achieved by the solar-driven floating prototype are depicted in Figure 16a. Notably, the productivity observed without the use of a membrane closely approximated that of a blank membrane, falling within the range of 1.15 ± 0.2 kg m² day⁻1. In stark contrast, the incorporation of photothermal elements significantly enhanced productivity, yielding an impressive increase of up to threefold. This enhancement allowed the average productivity to increase to approximately 3.6 ± 0.38 kg m² day⁻¹ during the testing conducted in September and October 2024 (the average solar radiation is 800 W m−1 and the average temperature 26°C), which is further corroborated by the approximately 95% rejection. The results clearly illustrate the critical role of photothermal technology in amplifying the efficiency of the solar-driven floating prototype. This research will be continued using simulated seawater with an average of 44,000 ppm salinity.

Figure 16b illustrates a comparative thermal analysis of two solar-driven prototypes. The first prototype lacks a membrane, while the second incorporates photothermal magnetic Janus membranes. Both prototypes were subjected to thermal imaging using an FLIR C5 camera to evaluate temperature distribution and assess the membrane’s influence on heat retention and water productivity. The prototype without a membrane exhibited a maximum temperature of 38.8°C and a minimum of 15.1°C, revealing a broader thermal gradient. The infrared imagery indicates substantial heat loss to the surrounding air and the water basin, resulting in a lower surface water temperature. This reduced temperature correlates with a moderate evaporation rate and, consequently, diminished distillate productivity. In contrast, the prototype featuring the photothermal membrane recorded a maximum temperature of 43.2°C and a minimum of 23.6°C, suggesting enhanced heat retention. The infrared image reveals a more concentrated heat zone around the water surface, highlighting the membrane’s effectiveness in capturing thermal energy. The elevated water temperature accelerates the evaporation process, thereby increasing the water production rate. The membrane functions as a thermal insulator, mitigating heat loss to the ambient air and augmenting the prototype’s heat retention capacity. By maintaining a higher concentration of heat at the water surface, the membrane significantly enhances the evaporation rate, resulting in greater freshwater production compared to conventional designs. Additionally, the membrane contributes to a more uniform thermal distribution, thereby minimizing convective cooling effects at the surface (Tables 4 and 5).

Performance comparison between the thermal analysis of the prototype without and with photothermal membranes

| Parameter | Without membrane | With membrane |

|---|---|---|

| Max temperature (°C) | 38.8 | 43.2 |

| Min temperature (°C) | 15.1 | 23.6 |

| Heat retention | Lower | Higher |

| Evaporation rate | Moderate | Higher |

| Water productivity | Lower | Increased |

Comparison between the previously published work and this work

| Item | Membrane description | Steam generation (kg m−2 h−1) | Ref. | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3D cylindrical cup-shaped structures of mixed metal oxides | 2.04 | [38] | 2018 |

| 2 | Bilayer Janus film by assembling gold nanorods onto the interconnected single-walled carbon nanotube porous film | 1.85 | [39] | 2018 |

| 3 | Laser synthesis of the Janus membrane on commercial polyimide to obtain floating graphene membranes | 1.37 | [40] | 2018 |

| 4 | Vertically oriented porous membranes within the PVDF membrane through a well-designed bidirectional freezing process | 1.58 | [41] | 2020 |

| 5 | rGO/PS@PSf; photothermal composite membrane; polysulfone (PSf) reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and polystyrene (PS) microspheres and CB/rGO/PS@PSf membranes | 1.06 | [42] | 2021 |

| Carbon black (CB) | 1.86 | |||

| 6 | Janus membrane composed of graphene fibers (GFs) on cellulose acetate layer and GF-filter paper | 1.40 | [43] | 2021 |

| 7 | Electrospinning polypropylene glycol-based polyurethane (PPG@PU) and polydimethylsiloxane-based polyurethane-CNTs (PDMS@PU-CNTs) | 1.34 | [44] | 2022 |

| 8 | AgNPs were incorporated into carbon composites derived from organosilicon; the AgNPs/C composite was then embedded in melamine foam (MF) using PDMS for improved adhesion and hydrophobicity, resulting in the AgNPs/C/MF (SCF) solar absorber AgNPs@C/MF | 1.62 | [45] | 2024 |

| 9 | Fe3O4/CNT nanomaterials and hydrophobic PVDF were introduced to delignified wood with a man-made-cutting structure (D-Wood)-(Fe3O4/CNT/PVDF@D-Wood evaporator) | 1.92 | [46] | 2024 |

| 10 | Janus hydrogel evaporator was constructed by incorporating the top layer containing light-absorbing core–shell magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4@PDA NPs), and the bottom layer composed of self-floating foam gel due to the addition of foaming agent | 2.89 | [47] | 2024 |

| 11 | Photothermal magnetic Janus membranes using iron–nickel alloys coated on PES/PcH membrane and real solar radiation | 3.5 | This study | 2025 |

These findings highlight the pivotal role of photothermal membranes in optimizing the efficiency of solar-driven prototypes, thereby advancing our understanding of their potential applications. The ongoing nature of this research promises further insights into enhancing membrane performance and prototype productivity.

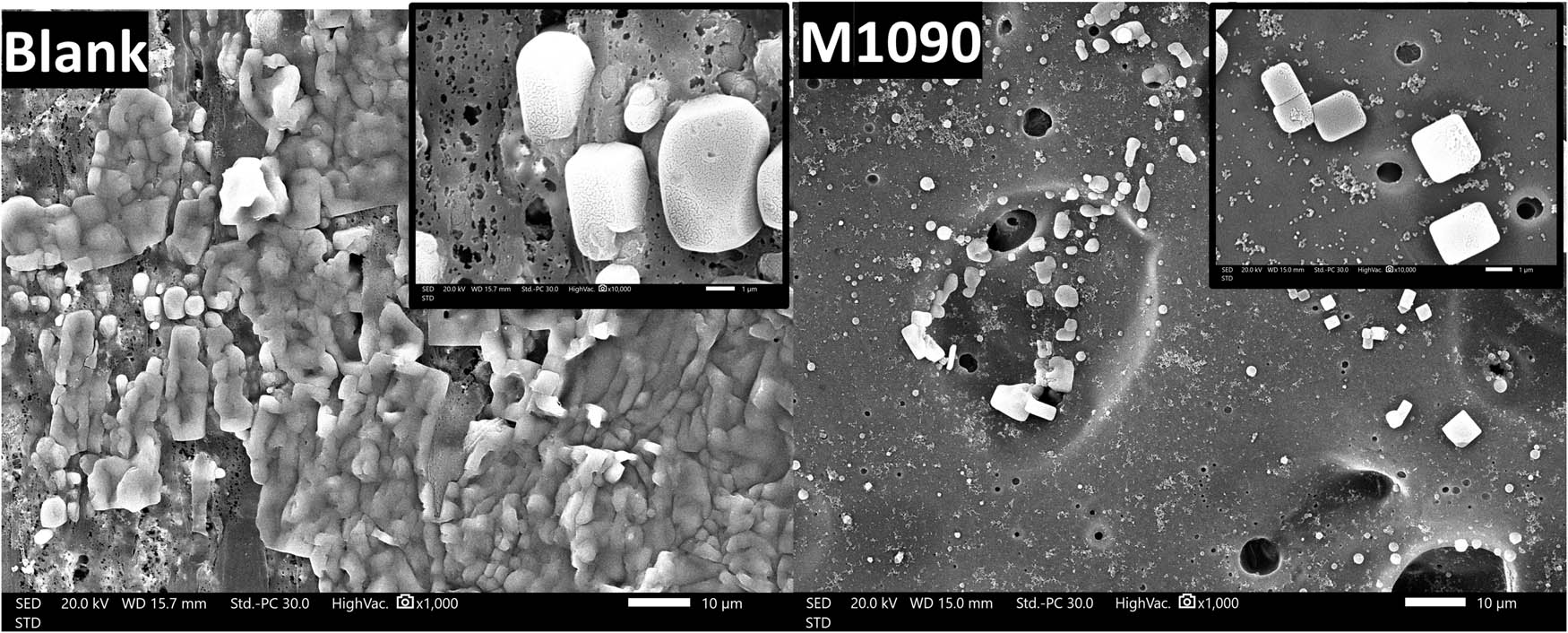

3.12 Scaling of the magnetic photothermal membrane

The salt tolerance and magnetic properties of the membrane are pivotal determinants of its efficacy across a range of applications. As illustrated in Figure 17, the photothermal membrane exhibited significantly reduced salt deposition compared to the control sample, suggesting that the membrane’s magnetization may play a beneficial role in mitigating scaling and enhancing performance over time. Furthermore, it appears that scaling obstructed the membrane’s pores, adversely affecting its tolerance to high salinity. This aspect warrants thorough investigation in future research endeavors.

4 General discussion

Materials with high absorption coefficients and wide absorption spectra across the desired wavelength range are preferred for light absorption applications. Therefore, the choice of alloy/filler/solar absorbents is crucial for photothermal membranes/foams/surfaces. Regarding iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents, the composition, particularly regarding the iron content, involves a trade-off between the rate of temperature increase and the rate of heat dissipation. Alloys with higher iron content can achieve a faster temperature increase but may also lose heat more quickly, while alloys with lower iron content may have a more gradual temperature increase but with relatively better heat retention properties. In general, alloy/solar absorbents with high thermal conductivity, such as metals or certain ceramics, can enhance the overall thermal conductivity of the membrane by providing additional pathways for heat transfer. When the alloy/solar absorbent is dispersed within the membrane material, it creates a network of conductive paths that facilitate the transfer of heat. This can increase the overall thermal conductivity of the composite material. The thermal conductivity enhancement is more pronounced when the alloy/solar-absorbent concentration is high and when the alloy/solar absorbent particles are well dispersed and in close contact with each other. It is worth noting that the distribution and orientation of the alloy/solar absorbents within the membrane also play a role in determining the effective thermal conductivity. If the alloy/solar absorbents are preferentially aligned in a particular direction, such as in anisotropic materials, the thermal conductivity can vary depending on the direction of heat flow. For that, the fused fabricated alloy/solar absorbents with an iron content exceeding 30% experienced a faster temperature increase but also demonstrated more rapid heat dissipation to the surrounding environment, particularly when exposed to airflow.

The relation between the membrane thickness and evaporation rate under sunlight can vary depending on the membrane material and environment, such as temperature, humidity, and air movement, which can significantly impact evaporation rates, regardless of the membrane thickness. In general, a thicker membrane tends to reduce the evaporation rate compared to a thinner membrane. Thicker membranes provide a greater barrier to water molecules, reducing their ability to escape through evaporation. This is because the thicker the membrane, the longer the diffusion path that water molecules must travel to reach the surface and evaporate. As a result, a thicker membrane can impede the movement of water molecules, slowing down the evaporation process. Additionally, thicker membranes can also provide an insulator, reducing the amount of heat transferred to the water surface. All the fabricated photothermal-magnetic Janus membranes showed lower membrane thickness than the blank membrane (Figure 4a), which may assist in higher values of the water evaporation rate, as shown in Figure 3b.

In general, there can be a correlation between the membrane thickness and tensile strength, but it is not a direct or linear relationship. However, thicker membranes tend to have higher tensile strength compared to thinner membranes; this is because the thickness of the material contributes to its structural integrity and ability to withstand mechanical stress, and consequently, a thicker membrane can distribute load and forces over a larger area, reducing the likelihood of tearing or failure. In this work, the coating of iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents on the membrane surface introduces a positive effect on the mechanical strength of the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes, although they have thinner thickness relative to the blank, as shown in Figure 4b.

The relationship between membrane evaporation rate and membrane hydrophilicity is generally inverse. In other words, as the hydrophilicity of a membrane increases, the evaporation rate tends to decrease. Hydrophilicity refers to the affinity of a material to attract and interact with water molecules. A hydrophilic membrane has a higher tendency to absorb or retain water on its surface. This characteristic can inhibit or slow down the evaporation of water through the membrane. When a membrane is hydrophilic, it can form a thin layer of water on its surface due to water’s strong interaction with the membrane material. This layer of water acts as a barrier to further water evaporation. It reduces the exposure of underlying water molecules to the surrounding environment, thereby decreasing the evaporation rate. On the other hand, hydrophobic membranes repel water and have a lower affinity for water molecules. Such membranes tend to facilitate faster evaporation since water does not readily adhere to their surface. Water droplets on a hydrophobic membrane will tend to bead up and roll off, allowing for more efficient evaporation. However, it is important to note that the relationship between membrane hydrophilicity and evaporation rate can be influenced by other factors as well. These factors include temperature, humidity, and airflow of the surrounding environment. As shown in Figure 5b, all the fabricated membranes demonstrated higher static water contact angles compared to the fabricated blank membrane. This indicates the positive effect of the hydrophobicity of the front black photothermal surface of the membrane on the evaporation rate.

The relationship between surface roughness and evaporation rate can be complex and dependent on various factors. In general, surface roughness can influence the evaporation rate through the following mechanisms: (1) rough surfaces typically have a larger surface area compared to smooth surfaces and consequently an increase in the surface area that provides more space for evaporation to occur, leading to higher water evaporation rates; (2) surface roughness can disrupt the laminar flow of air (or liquid) over a smooth surface and generate turbulence; (3) turbulent flow enhances the exchange of heat and mass between the surface and the surrounding medium, promoting faster evaporation; (4) surface roughness can create capillary structures, such as grooves or pores, that can trap and hold liquid and these capillary structures can increase the effective surface area available for evaporation and facilitate the transport of liquid to the surface, thus potentially increasing the evaporation rate; and (5) rough surfaces can impede the diffusion of vapor away from the surface due to irregularities and barriers. This hindrance can result in a slightly lower evaporation rate compared to a smooth surface under the same environmental conditions. In this work, two different techniques were used to determine the membrane surface roughness (Figures 6 and 7). A larger membrane area for measuring surface roughness can provide a more comprehensive assessment of the overall roughness characteristics. It allows for the inclusion of a larger number of surface features and variations, resulting in a more representative measurement of the surface roughness. This approach is useful when analyzing surfaces with significant variations or when a global assessment of the roughness is required. M1090 showed the largest roughness using a larger surface area for determination; however, it shows the lowest roughness on the micrometer scale of determination.

The specific relationship between the surface roughness and evaporation rate can vary depending on the system and the characteristics of the roughness. Factors such as temperature, humidity, air or liquid flow, and the properties of the evaporating substance play significant roles in determining the evaporation rate. The presence of surface roughness can affect the contact angle and, consequently, the evaporation rate. On a rough surface, the liquid droplet may not spread uniformly, resulting in a higher contact angle, as shown in Figures 3b and 5b.

The membrane bulk porosity and surface porosity can both have an impact on the evaporation rate. Membrane bulk porosity refers to the volume fraction of void spaces within the bulk of the membrane material itself. It represents the overall porosity of the membrane structure, including both interconnected and isolated pores. Membranes with higher bulk porosity generally have a larger number of interconnected pores, which can enhance liquid transport through the membrane. In the context of evaporation, a higher bulk porosity can facilitate the movement of liquid from one side of the membrane to the other, potentially increasing the evaporation rate. Surface porosity, on the other hand, refers to the presence of pores or cavities on the surface of the membrane. These surface features can affect the transport of liquid and vapor at the membrane interface. In the case of evaporation, back surface porosity can influence the access of the liquid to the membrane surface and the escape of vapor from the surface. Membranes with higher front surface porosity, as shown in Figure 8 (M1090), may provide more sites for liquid evaporation, leading to an increased evaporation rate. The closed membrane pores by thick, dense alloys/solar absorbents, as in the case of M4060 and M5050, prevent the free movement of water vapor, limiting the rate of water evaporation and potentially affecting the performance of the system or process in which the membrane is employed.

Absorbance refers to the ability of a material to absorb light at a specific wavelength. When light passes through a material, it can be transmitted (passes through), reflected (bounces off), or absorbed (energy is taken in by the material). The absorbance of a material can vary depending on various factors, including the angle at which the light is incident on the material. When light hits a material at different angles, the interaction between the light and the material can change. Some materials exhibit anisotropic properties, meaning that their physical properties, including absorbance, depend on the direction of measurement. This can be due to the material’s crystal structure and molecular alignment. However, iron–nickel alloys/solar absorbents are known as isotropic materials that have the same physical properties. When sun rays are perpendicular to an absorbing surface, the irradiance incident on that surface has the highest possible power density. As the angle between the sun and the absorbing surface changes, the intensity of light on the surface is reduced. For intermediate angles, the relative power density is cos(θ), where θ is the angle between the sun rays and direct normal (or perpendicular) to the surface. The irradiance absorbed by the surface can be determined by multiplying the total irradiance by cos(θ). I i = I t cos(θ), where I i is the irradiance absorbed by the surface, I t is the total irradiance, and θ is the incident angle [37]. While the absorption of the blank white membrane fluctuates depending on the incident angle, the photothermal magnetic Janus membranes consistently exhibit exceptional light absorption rates (over 95%) across all angles, as shown in Figure 10.

The unique starfish-like iron–nickel alloy/solar absorbent penetration into the membrane cross-section by the effect of their tips [30,38], in addition to the surface, allows for an increase in the ability to conduct heat from the upper surface of the membrane to the lower surface adjacent to the water surface, which improves the membrane’s ability to heat. It also allows water vapor to pass through the spaces formed between the polymer and the alloy/solar-absorbent particles, and thus increases the thermal conversion efficiency and consequently the water evaporation, as shown in Figures 15 and 16.

Evaporation rate, salt rejection, and thermal conversion efficiency of photothermal magnetic Janus membranes using simulated seawater (35,000 ppm) using insulated beakers under real solar radiation.

(a) Productivity (kg m−2 day−1) using 1,000 ppm, and (b) thermal imaging of the solar-driven floating desalination prototype using blank and photothermal M1090 membranes under real solar radiation.

Salt tolerance determines the membrane’s ability to withstand saline environments, which is essential for processes such as desalination and wastewater treatment. Meanwhile, the magnetic properties can enhance the membrane’s functionality, enabling applications in separation technologies and environmental remediation. Investigating these characteristics is vital for optimizing membrane design and improving efficiency in real-world applications (Figure 17).

SEM imaging of the front surface of both the blank and photothermal magnetic Janus membrane (M1090) after 9 days of operation under real solar radiation and a salinity of 35,000 ppm, displayed at magnifications of 1,000× and 10,000×.

The key distinction between the previously published studies and this research lies in the evaluation method of the fabricated membranes. Earlier works assessed the membranes using simulated sunlight at high temperatures (up to 80°C) and very low humidity, without any insulation around the glass beakers or containers. This setup aimed to confine evaporation heat to the membrane alone. In contrast, this study measures water evaporation rates under actual solar radiation and real environmental conditions, incorporating varying temperatures, humidity, and airflow. Table 1 shows the difference between the previous work using artificial 1 sun radiation and this study under real solar radiation and simulated seawater (35,000 ppm).

5 Conclusions

The development of novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes marks a significant advancement in solar water desalination technology. These membranes possess unique capabilities, including efficient light absorption, photothermal conversion, and selective separation. By leveraging these properties, solar-driven desalination systems can achieve enhanced energy efficiency, increased freshwater production, and improved sustainability by eliminating the need for brine disposal. This study sets itself apart from previous research by evaluating membrane performance under realistic environmental conditions, including variations in temperature, humidity, and airflow, rather than relying solely on simulated high-temperature scenarios. This comprehensive assessment provides a more accurate evaluation of the membranes’ effectiveness in practical applications. Further research and development in this field hold the potential to revolutionize the desalination industry and address the pressing global challenge of water scarcity.

6 Future work recommendations

The evaporation rate experiments detailed in this study primarily aimed to validate the effectiveness of the newly developed JPTMs for water desalination. However, further exploration into practical applications is crucial for advancing this technology.

The interactions among alloy composition, membrane thickness, and surface roughness are complex and multifaceted. Understanding these relationships is essential for optimizing material performance in various applications. The design of a membrane as a 3D block with substantial thickness introduces unique challenges and opportunities. A thicker 3D structure can enhance structural stability and potentially support complex geometries that maximize surface area. However, if the thickness is excessive, it may lead to thermal inefficiencies and reduced productivity due to increased thermal resistance. Future research should focus on the experimental and computational modeling of these interactions to develop materials that meet specific performance criteria.

The influence of magnetization on the resistance to salt deposition on membrane surfaces represents a compelling field of investigation, especially regarding the optimization of membrane efficacy in applications such as desalination should be deeply investigated.

Conducting a full exergy analysis of the desalination system is also recommended to accurately assess its performance metrics, as this will provide a deeper understanding of energy efficiency and losses. Furthermore, incorporating a heat recovery system will help regulate the temperature within the evaporator, enhancing overall efficiency. Finally, a thorough economic study should be undertaken to evaluate the scalability, economic viability, and environmental impact of the system in comparison to similar technologies. This holistic approach will not only improve the understanding of the JPTMs’ capabilities but also facilitate their integration into practical desalination applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) under grant number 46917.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) under grant number 46917.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

[1] Chen C, Kuang Y, Hu L. Challenges and opportunities for solar evaporation. Joule. 2019;3(3):683–718.10.1016/j.joule.2018.12.023Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Tong T, Elimelech M. The global rise of zero liquid discharge for wastewater management: drivers, technologies, and future directions. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(13):6846–55.10.1021/acs.est.6b01000Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Qiblawey HM, Banat F. Solar thermal desalination technologies. Desalination. 2008;220(1):633–44.10.1016/j.desal.2007.01.059Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Kabeel AE, El-Agouz SA. Review of researches and developments on solar stills. Desalination. 2011;276(1):1–12.10.1016/j.desal.2011.03.042Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Ni G, Li G, Boriskina Svetlana V, Li H, Yang W, Zhang T, et al. Steam generation under one sun enabled by a floating structure with thermal concentration. Nat Energy. 2016;1(9):16126.10.1038/nenergy.2016.126Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Zeng Y, Yao J, Horri BA, Wang K, Wu Y, Li D, et al. Solar evaporation enhancement using floating light-absorbing magnetic particles. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4(10):4074–8.10.1039/c1ee01532jSuche in Google Scholar

[7] Wu D, Zhao C, Xu Y, Zhang X, Yang L, Zhang Y, et al. Modulating solar energy harvesting on TiO2 nanochannel membranes by plasmonic nanoparticle assembly for desalination of contaminated seawater. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2020;3(11):10895–904.10.1021/acsanm.0c02123Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Awad FS, Kiriarachchi HD, AbouZeid KM, Özgür Ü, El-Shall MS. Plasmonic graphene polyurethane nanocomposites for efficient solar water desalination. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2018;1(3):976–85.10.1021/acsaem.8b00109Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Loo SL, Vásquez L, Zahid M, Costantino F, Athanassiou A, Fragouli D. 3D photothermal cryogels for solar-driven desalination. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(26):30542–55.10.1021/acsami.1c05087Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Zhou J, Yang L, Cao X, Ma Y, Sun H, Li J, et al. MXene nanosheets coated conjugated microporous polymers hollow microspheres incorporating with phase change material for continuous desalination. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2024;654:819–29.10.1016/j.jcis.2023.10.091Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Ying P, Ai B, Hu W, Geng Y, Li L, Sun K, et al. A bio-inspired nanocomposite membrane with improved light-trapping and salt-rejecting performance for solar-driven interfacial evaporation applications. Nano Energy. 2021;89:106443.10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106443Suche in Google Scholar