Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

-

Saud Bawazeer

, Abdur Rauf

, Syed Uzair Ali Shah

Abstract

The green biosynthesis of metal nanoparticles of already explored phytomedicines has many advantages such as enhanced biological action, increased bioavailability, etc. In this direction, keeping in view the peculiar medicinal value of Tropaeolum majus L., we synthesized its silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by adopting eco-friendly and cost-effective protocol by using methanolic and aqueous extract of T. majus. The synthesized AgNPs were characterized by using several techniques including UV spectroscopic analysis, FTIR analysis, and atomic force microscopy. The methanolic/aqueous extracts of T. majus and synthesized AgNPs were assessed for antioxidant potential and antimicrobial effect. The preliminary screening showed that the T. majus extracts have variety of reducing phytochemicals including tannins, terpenoids, flavonoids, and cardiac glycosides. The green synthesis of AgNPs was confirmed by the appearance of sharp peak at 430–450 nm in the UV-Visible spectra. The FTIR spectral analysis of extract and AgNPs exhibited that peaks at 2947.23, 2831.50, 2592.33, 2522.89, and 1,411 cm−1 disappeared in the spectra of FTIR spectra of the AgNPs, indicating carboxyl and hydroxyl groups are mainly accountable for reduction and stabilization of AgNPs. Atomic force microscopic scan of the synthesized AgNPs confirmed its cylindrical shape with size of 25 µm. The extracts and AgNPs were investigated for antioxidant potential by DPPH-free radical essay, which showed that aqueous extract has significant and dose-independent antioxidant activity; however, the synthesized AgNPs showed decline in antioxidant activity. The extracts and synthesized AgNPs were also evaluated for antibacterial activity against Klebsiella pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus subtilis. Neither extract nor AgNPs were active against Klebsiella pneumonia. The aqueous and methanolic extract exhibited inhibition against Bacillus subtilis and their synthesized AgNPs were active against Staphylococcus aureus. Our data concluded that the extracts of T. majus have necessary capping and reducing agents which make it capable to develop stable AgNPs. The aqueous extract of T. majus has potential antioxidant effect; however, the AgNPs did not enhance its free radical scavenging effect. The bacterial strains’ susceptibility of the extract and AgNPs was changed from Bacillus subtilis to Staphylococcus aureus, respectively. The biological action of AgNPs is changed in case of antibacterial activity which means that AgNPs might change the specificity of T. majus and likewise other drugs.

1 Introduction

The medicinal plants provided the ailments and cure throughout human history. Plants are capable of producing diverse range of chemical compounds that are responsible for various biological actions [1]. Even at the dawn of twenty-first century, about 90% of potential drug molecules have been isolated directly or indirectly [2]. WHO estimated that 80% population of Africo-Asian countries utilize herbal medicine in their primary health care system [3]. The clinical application of herbal drugs faces the same challenges as allopathic medicines like selectivity, drug delivery, solubility, safety, toxicity, efficacy, and frequent dosing [4,5]. The modern pharmaceutical research could overcome the above-mentioned challenges by developing novel drug distribution systems of herbal medicines, including, micro emulsion, nanoparticles’ solid dispersion, liposomes, matrix system as well as solid lipid nanoparticles [6,7].

Nanotechnology is emerging as interdisciplinary science for resolving various problems in the fields of biomedical sciences, pharmacology, and food processing [8,9,10]. It deals with matter at the scale of one billionth of a metre, so the nanoparticle is the most fundamental component in the fabrication of a nanostructure. The nanometre-sized particles exhibit interesting and surprising capabilities [11,12]. There are various methods reported for fabrication of nanoparticles, but metal nanoparticles like gold and silver are extensively studied due to their unique electrical and optical properties.

The study of techniques for the synthesis of AgNPs of various morphologies and sizes is widely accepted recently [13,14]. Currently, various chemical and physical methods are applied for the green synthesis of AgNPs, but most of them have limitation for being expensive and inclusion of hazardous solvents [15]. The technique of green biosynthesis of eco-friendly metal NPs processes is studied widely, where the bio-extracts are fabricated as NPs [16,17]. It involves the reduction of metal ions by phytochemicals of extracts to fabricate them as NPs [18]. Various reducing phytochemicals are involved in this process including phenol, tannins, terpenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids, quinines, etc. The above-mentioned technique leads to formation of crystalline NPs ranging in size between 1 and 100 nm and has several advantages including low cost and easy availability. The extracts’ capability to be fabricated as stable NPs depends on the phytochemical profile of the plant extract.

Tropaeolum majus L. (T. elatum Salisb., Tropaeolaceae) is a fast-growing annual plant native to Peru and Bolivia, found in South and Central America and subcontinent. The plant is commonly identified with the name of nasturtium or nasturtiums. The genus roughly includes 80 species. The explored constituents of T. majus included carotenoids (zeaxanthin, lutein, and carotene), anthocyanins (delphinidin, cyaniding, delphinidin, and pelargonidin derivatives), flavonoids (quercetin and kaempferol glycosides), sulfur compounds (glucotropaeolin), phenolic acids (chlorogenic acid), cucur-bitacines, and vitamin C [19,20,21,22,23]. Nasturtium plant has been reported for various ailments including upper respiratory tract (bronchitis, tonsillitis) as well as urinary tract diseases [19,22,24], cardiovascular disorders, and constipation [25,26,27]. It is reported as disinfectant, wound-healing, antibiotic [28,29], antiascorbutic [29], and anticancer activity [30]. Moreover, in the fields of cosmetology and dermatology, its external use for treatment of diseases of the hair, nails, and skin (itchy dandruff), superficial/moderate burns, and rashes has been reported [19]. The leaves and flowers contain glucosinolates resulting in its peppery flavour and are commonly used in salads [31].

In the present study, we aimed to synthesize the AgNPs of T. majus, keeping in view its extensive medical applications. The preliminary investigation of T. majus has led us to the presence of high number of flavonoids, phenolics, and tannins components which might play role in antioxidant effect. Thus, we aimed to synthesize the stable AgNPs of T. majus’ methanolic and aqueous extract by adopting easy, reliable, and simple method and evaluate their antioxidant and antibacterial activities.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

Silver nitrate (BDH laboratory, BH.15-1TD) was purchased from local market of Peshawar. De-ionized water, potassium bromide, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), methanol, sulphuric acid, sodium hydroxide, ammonia, ammonium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, and trichloro methane were purchased from Merck.

2.2 Plant collection and extraction

The plant is obtained from the ground of Botany Department, University of Peshawar, Peshawar. The plant specimen was recognized by taxonomist Ghulam Jillani from Department of Botany, University of Peshawar. The plant material was collected and dried under shade for about 15 days. The dried plant material (leaves) of Tropaeolum majus was crushed to make well powder. The powder materials were soaked in methanol for 3 days and assessed for normal cold extraction until exhaustion of plant materials. The obtained extract was then concentrated under reduced pressure at low temperature using rotary evaporator. The same procedure was done for aqueous extract by soaking the powder material with water [32].

2.3 Phytochemical screening

Chemical tests for phytochemicals like anthraquinones, tannins, alkaloids, glycosides, saponins flavonoids, steroids, reducing sugars, terpenoids, phlobatanins, anthocyanins, soluble starch, and free reducing sugars were carried out on the methanol extract of the leaves of Tropaeolum majus using standard procedure to identify the constituents as described by Sofowora, Trease, and Evans [32,33,34].

2.4 Synthesis of nanoparticles

The fresh plant materials were cleaned by washing with water to remove dust and other impurities. The derided plant sample was cut into small pieces. Small pieces of fresh plants materials were put in a conical flask separately followed by the introduction of methanol. The flasks were kept for three days, after that the solutions were filtered and filtrates were concentrated and stored in the refrigerator at 4°C [35].

2.4.1 Preparation of stock and salt solutions

Crude extract (0.1 g) of plant Tropaeolum majus was dissolved in 50 mL of methanol, to prepare stock solution of extract. For the synthesis of metallic nanoparticles, 17 mg of silver nitrate (AgNO3) was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water to prepare 1 mM salt stock solution. The salt solutions were stored in refrigerator in reagents bottle which was coated by aluminium foil for further use [35].

2.4.2 Processing for synthesis of AgNPs

The prepared stock solutions of extract and salt were combined in different ratios, i.e. 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4, by making the extract solution diluted in each successive reaction mixture. The reaction mixture 1:1 was first heated at 70°C for 1 h; the colour was observed before heating and after some time. The modification in colour exhibited the reduction process and the synthesis of nanoparticles. The above-mentioned ratios were then heated same as for 1:1. The UV spectra were taken for each and every step to check and confirm the synthesis of metallic nanoparticles [35].

2.4.3 Time and temperature effect on synthesis of AgNPs

The time and temperature effect of synthesized nanoparticles was performed for confirming the stability of nanoparticles. The nanoparticles showed maximum absorbance was first heated at 70°C for 30 min, and then time was extended to 60, 90, and 120 min. The temperature effect was assessed by heating the same ratio of stock and salt solution at 30°C, 50°C, 70°C, 80°C, and 100°C. The stability of nanoparticles was then confirmed by taking UV spectra [36].

2.5 Characterization

2.5.1 UV-Vis spectroscopy

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry assay is considered easy and less time-consuming assay for confirmation of the synthesis of nanoparticle [37,38]. The UV-Vis analysis was done by using a double beam spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV spectrophotometer). Simply, 4 mL of the diluted newly synthesized AgNPs solution was placed in a cuvette and inserted in the UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The UV-Vis spectrum was obtained for the sample using wavelength range of 300–800 nm.

2.5.2 FT-IR analysis

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) is one of the preferentially implemented methods of infrared spectroscopy. The IR method involves the principle of allowing the IR radiation to pass through a sample. During the process, the sample absorbs some of the radiations, while some of it will be transmitted through sample. The resultant IR spectrum represented as the molecular absorption and transmission spectrum, producing a clear idea regarding the molecular composition or fingerprints of the sample. They are referred fingerprints because of uniqueness of the IR spectrum, i.e. each molecular structure has its unique infrared spectrum. The FTIR spectrum of Tropaeolum majus, AgNPs were recorded using a FTIR prestige-21 Shimadzu FTIR spectrophotometer [39]. FT-IR measurement was performed and analysed for identification of the chemical ratios of the plant crude extracts and synthesized AgNPs. Both (plants crude extracts and synthesized AgNPs) were analysed in the range from 400 to 4,000. The analysis was done by following potassium bromide (KBr) pellets method. Both the spectra of crude and AgNPs were compared to each other for the confirmation of nanoparticles synthesis.

2.5.3 Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

The atomic force microscopy (AFM) for characterization of nanoparticles is the most suited technique [40]. It has the capability of 3D visualization and is effective in gathering both qualitative and quantitative information on many physical parameters of nanoparticles. The physical parameters that could be analysed with AFM included size, surface texture (roughness or smoothness), and morphology. It could also provide statistical information regarding size, surface area, and volume distributions. AFM is capable of analysing wide range of particle sizes in the same scan, ranging from 1 nm to 8 µm. Furthermore, the characterization of nanoparticle with AFM is possible in multiple mediums, for example, controlled environments, ambient air, and even liquid dispersions.

2.6 Biological activities

2.6.1 Antioxidant activity (DPPH radical scavenging assay)

The antioxidant potential was measured by DPPH radical scavenging assay [41]. The principle of the assay is bleaching of the purple-coloured methanol solution of 2,2-diphenyl-1-pierylhydrazyl (DPPH) correspondent to the measurement of the hydrogen atom or electron donation anilities in the sample. All the samples were performed in triplicate. Simply, 3 mL of samples (extracts/AgNPs) solutions in methanol (containing 10–100 μg) and control (without sample) were mixed with 1 mL solution of DPPH radical solution (1 mM) in methanol. The solution was allowed to stand for 30 min, then the absorbance was measured in dark at wavelength ʎ = 517 nm. The decline of the absorbance of DPPH solution is represented as an increase of the DPPH radical scavenging activity. The following formula was used for calculation of percent radical scavenging activities (%RSA):

where control OD is the absorbance of the blank sample and OD sample is the absorbance of samples or standard sample.

2.6.2 Antibacterial activity

Three strains of bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Bacillus subtilis) were used to analyse antibacterial activity of T. majus extract and AgNPs. The above-mentioned bacterial strains were kept at 4°C in Muller-Hinton agar. Modified agar well diffusion method was implemented for analysis of antibacterial activity of crude extract and AgNPs. The cultures were cultivated in triplicates at temperature of 37°C for 1–3 days. Then the broth cultures were transferred to sterilized Petri-dish following addition of 20 mL of the sterilized molten MHA. The amount of 0.2 mL of the extracts and derived AgNPs solution were added in corresponding wells through a bore into the medium. The streptomycin (2 mg/mL) was used as reference antimicrobial agent. To ensure complete diffusion of the antimicrobial agent into the medium, inoculation was extended for 1 h. The inoculated plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and the diameter of the zone of inhibition of bacterial growth was measured in the plate in millimetres [42,43].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phytochemical screening of plant T. majus

Selected plant (Tropaeolum majus) was subjected to extraction to get methanolic and aqueous extract. Keeping in view the objectives of this research project, the resultant extracts were analysed for presence or absence of important reducing phytochemicals. The data from preliminary screening of extracts have been shown in Table 1. Both the methanolic and aqueous extracts indicated the presence of tannins, alkaloids terpenoids, flavonoids, and cardiac glycosides. These compounds may be actively involved in the reduction of silver and gold ions to nanoparticles.

Phytochemical analysis of aqueous and methanolic extracts of Tropaeolum majus

| Chemical components | Methanolic extract | Aqueous extract |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | + | + |

| Tannins | + | + |

| Anthraquinone | − | − |

| Glycosides | − | − |

| Reducing sugar | − | − |

| Saponins | − | − |

| Flavonoids | + | + |

| Phlobatanins | − | − |

| Steroids | − | − |

| Terpenoids | + | + |

| Cardiac glycoside | + | + |

| Coumarin | − | − |

| Emodins | − | − |

| Betacyanin | − | − |

| Carbohydrates | − | − |

| Monosaccharide’s | − | − |

| Free reducing sugar | − | − |

| Combined reducing sugars | − | − |

| Soluble starch | − | − |

3.2 Characterization of AgNPs

The newly synthesized AgNPs were characterized by using UV-Vis spectroscopy, FTIR, and AFM.

3.2.1 UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis

The UV-Vis spectroscopy is mostly used for confirmation of newly synthesized metal NPs. It measures surface plasmon resonance peaks of the metals. The property of surface plasmon resonance of the metals makes them capable of exhibiting distinctive optical properties. The addition of T. majus extract to salt solution at room temperature caused the solutions to change from dark green to orange brown, the apparent indication of the formation of AgNPs. This colour change is reported due to the reduction of Ag+ to Ag0 by using the active phytochemicals present in the extract of T. majus [38]. The variety of phytochemicals that act as reducing and capping agents for the synthesis of NPs are already reported. The diverse range of molecules present in the plant extracts is responsible for the synthesis of symmetrical NPs [27]. Experiment was carried out with varying stock solutions of T. majus extract and salt solution ratio. For monitoring of the formation and stability of silver nanoparticles, the absorption spectra of the synthesized silver AgNPs were recorded against methanol. The peak absorbance of AgNPs was observed in wavelength (ʎ) range of 400–600 nm in methanol solutions which exhibited the successful formation of AgNPs.

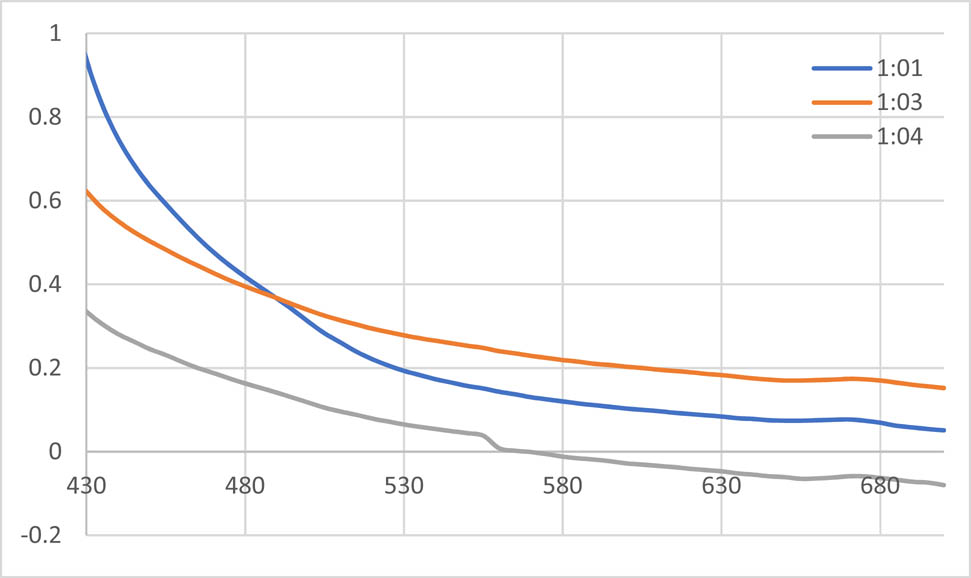

3.2.1.1 UV spectrum of AgNPs synthesized with methanolic extract of T. majus

The absorption spectra of synthesized AgNPs were recorded against methanol. The given spectrum shows the UV-Vis spectra of AgNPs formation using constant silver nitrate ratio with successive increasing ratios of extract at room temperature. The colour of the solution changed from dark green to orange brown. The different ratios of the nanoparticles (AgNPs) are shown in the Figure 1. The efficient synthesis was observed in reaction mixture (1:1) at ʎ = 430 nm.

UV spectra of the AgNPs solution with methanolic extract of Tropaeolum majus.

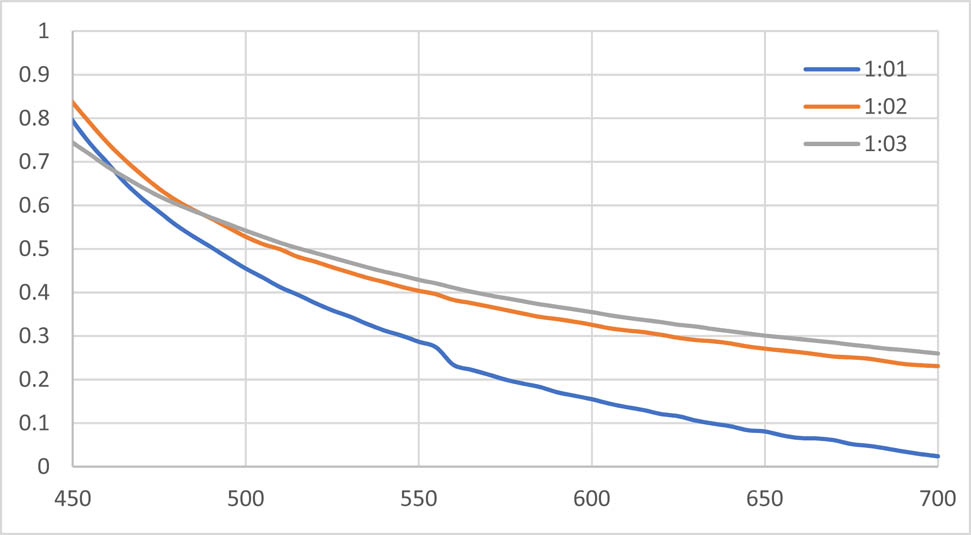

3.2.1.2 UV spectrum of AgNPs synthesized with aqueous extract of T. majus

The absorption spectra of synthesized AgNPs were recorded against water. The given spectrum shows the UV-Vis spectra of AgNPs’ formation using constant silver nitrate concentration with different aqueous extract concentrations at room temperature. The different ratios of the nanoparticles are shown in the Figure 2. The efficient synthesis was observed by 1:1 AgNPs at 450 nm absorbance.

UV spectra of AgNPs solution with the aqueous extract of Tropaeolum majus.

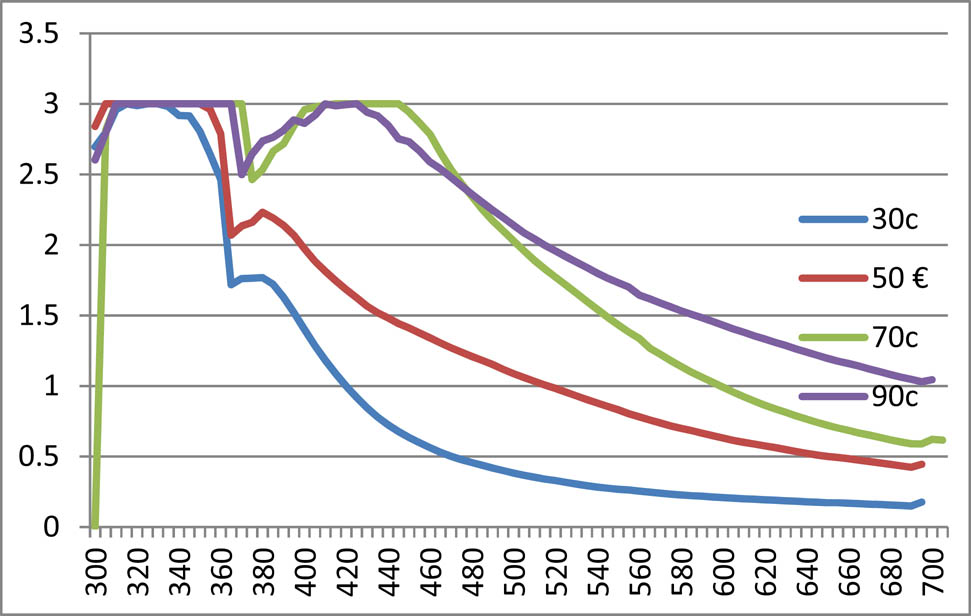

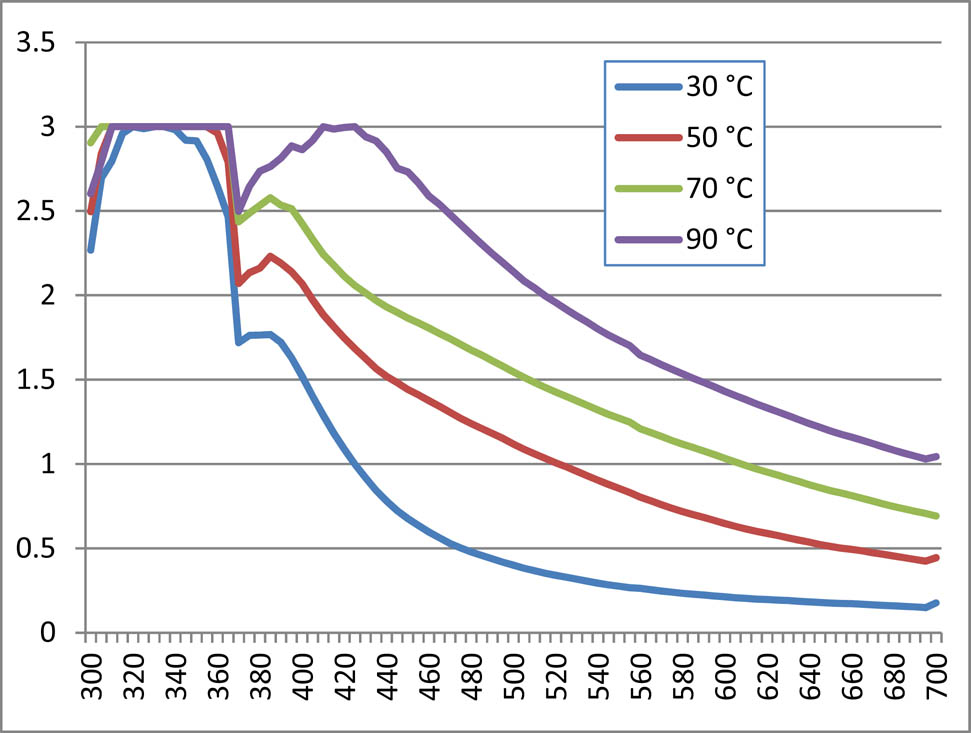

3.2.1.3 Temperature effect on AgNPs synthesis with methanolic and aqueous extract of T. majus

In the present set of experiment, the concentration of silver salt and extract solution was kept constant, i.e. 1:1 under variable temperature range to observe any possible effect of temperature on AgNPs synthesis. Temperature effects of the methanolic and aqueous extract are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Data exhibited that increasing temperature increased synthesis of nanoparticles, both of methanolic and aqueous extracts. The maximum absorbance was observed under temperature of 70°C and 90°C.

Temperature effect of methanolic nanoparticles of Tropaeolum majus.

Temperature effect of aqueous nanoparticles of Tropaeolum majus.

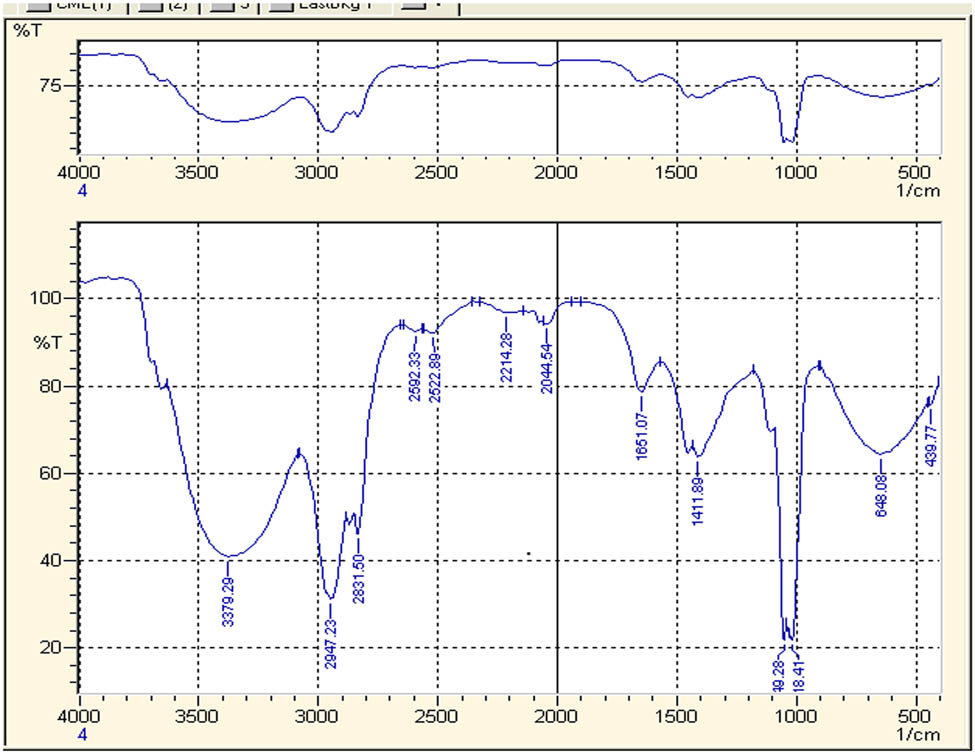

3.2.2 FTIR spectra analysis of extracts and synthesized AgNPs of T. majus

The FTIR spectra acquired from the methanolic extract of T. majus and synthesized AgNPs are demonstrated in Figures 5 and 6. In Figure 5, a broader peak observed at 3,379 cm−1 is attributed to the O–H bonds stretching, indicating presence of aromatic alcoholic and phenolic compounds. The peaks such as 2947.23, 2831.50, 2592.33, and 2522.89 cm−1 reflect carboxylic acid bond stretching. The peak of 1635.78 cm−1 shows carbonyl group C═O and peak at 1411.89 cm−1 shows C–C stretching. The peak at 2,947 indicates the presence of ant symmetric CH2 stretching. The peak at 2,214 is due to the C–H unsaturated stretching. The peak at 1,661 is due to C═O stretching. The peak at 1,411 is due to OH diff and the peak at 643 indicates the presence of C–H diff.

FTIR spectrum of crude water extract of Tropaoelum majus.

FTIR spectrum of methanolic nanoparticles of Tropaeolum majus.

When FTIR spectra were compared with those of AgNPs, the spectra exhibited different IR absorption. FTIR analysis of the AgNPs obtained after 60 min of reaction was performed to detect involvement of different functional groups present in T. majus extract (Figure 6). The peaks at 2947.23, 2831.50, 2592.33, 2522.89, and 1,411 cm−1 disappear in the spectra of FTIR spectra of the AgNPs. Thus, it means that carboxyl and hydroxyl groups are considered mainly accountable for reduction and stabilization of AgNPs [44]. Broad bands observed in spectra of AgNPs, 544.92 and 541.31 cm−1, validated the formation of AgNPs which were not observed in the crude FTIR spectrum [45]. The formation of AgNPs is in agreement with already existing studies on AgNPs synthesis by using various plant extracts [46].

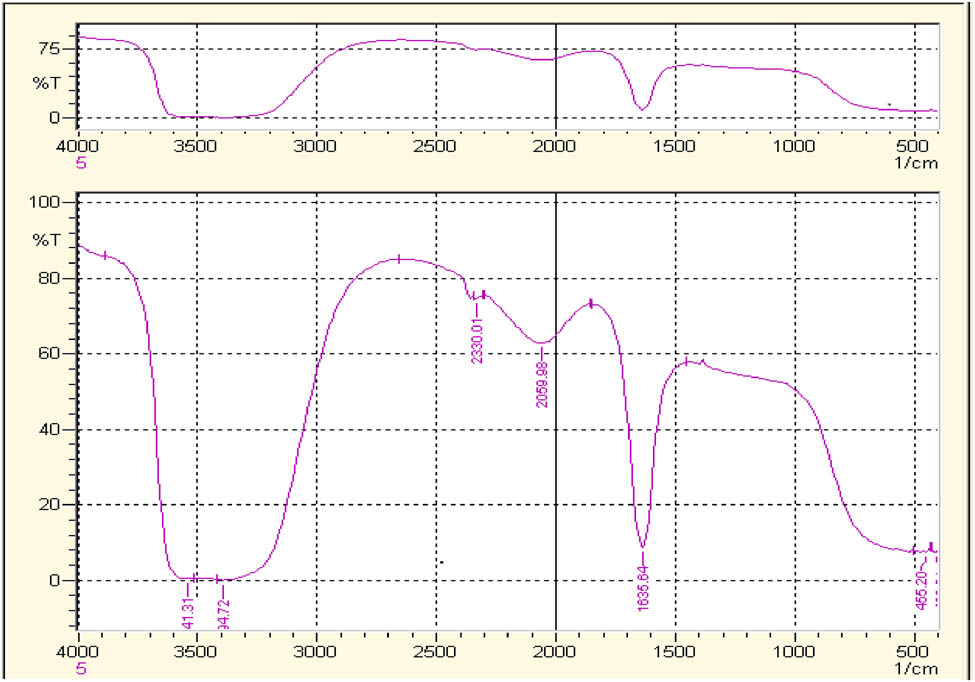

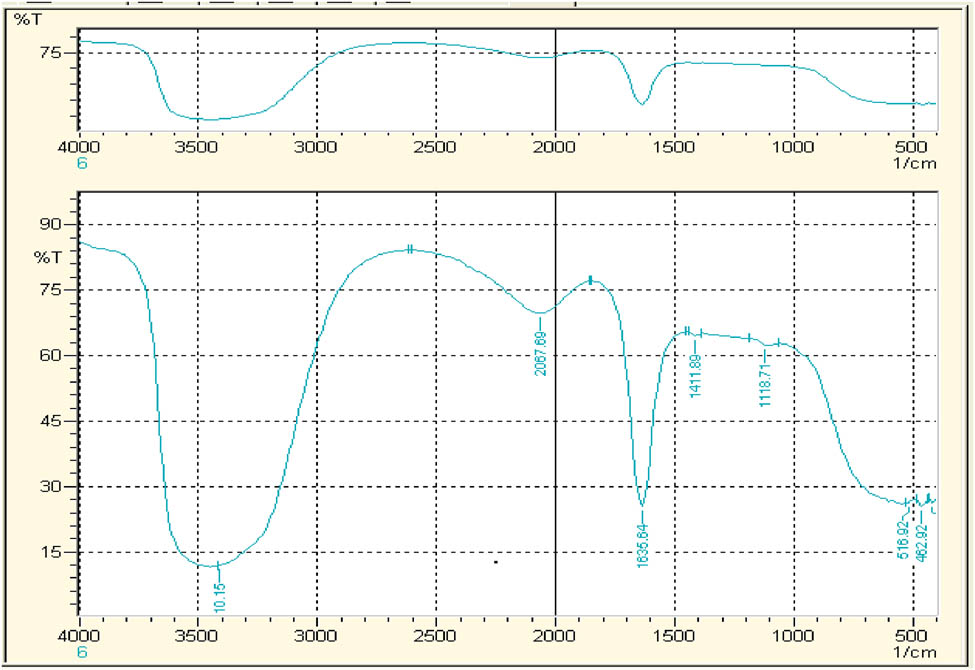

The FTIR spectra acquired from the aqueous extract of T. majus and synthesized AgNPs are demonstrated in Figures 7 and 8, respectively. In Figure 7, the peak of 1635.78 cm−1 shows carbonyl group C═O and peak at 1411.89 cm−1 shows C–C stretching. The peak 1,118 cm−1 exhibits C–N stretching. While comparing the FTIR spectra of synthesized AgNPs (Figure 8), only peak 1,118 cm−1 is missing which attributes to C–N stretching and seems to be mainly responsible for aqueous AgNPs synthesis.

FTIR spectrum crude water extract of Tropaeolum majus.

FTIR spectrum water nanoparticles of Tropaeolum majus.

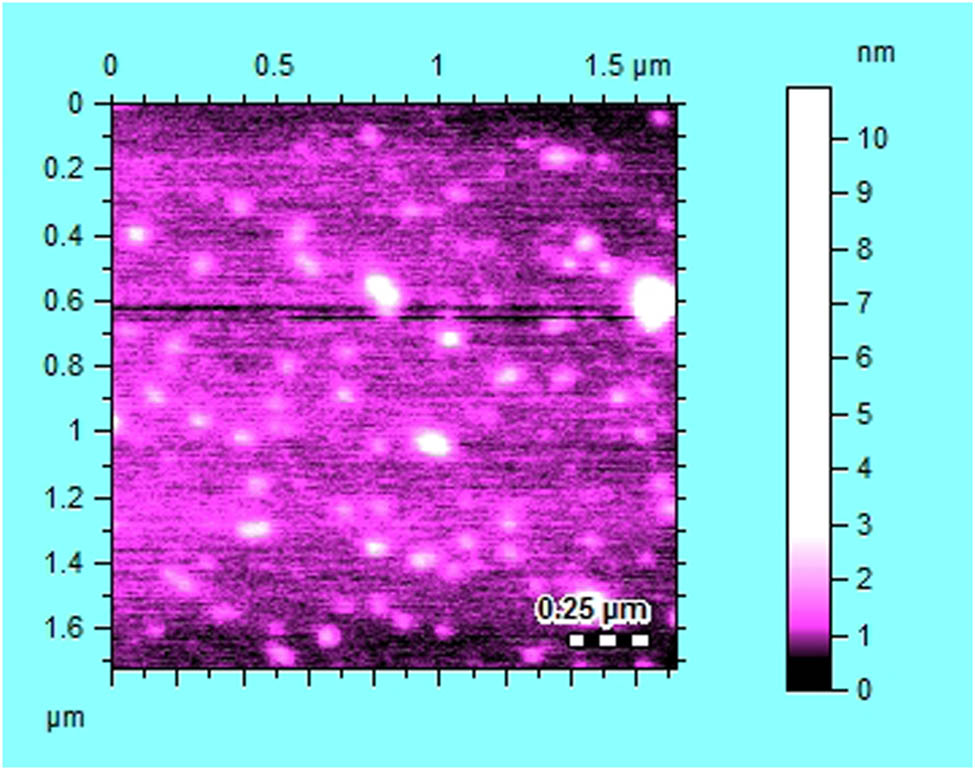

3.2.3 Atomic force microscopic analysis

The AFM for characterization of nanoparticles is the most suited technique [40]. It has the capability of 3D visualization and is effective in gathering both qualitative and quantitative information on many physical parameters of nanoparticles. The physical parameters that could be analysed with AFM included size, surface texture (roughness or smoothness), and morphology. It could also provide statistical information regarding size, surface area, and volume distributions. AFM is capable of analysing wide range of particle sizes in the same scan, ranging from 1 nm to 8 µm. Furthermore, the characterization of nanoparticle with AFM is possible in multiple mediums, for example, controlled environments, ambient air, and even liquid dispersions. The AFM scan of the AgNPs synthesized from methanolic extract of T. majus is shown in Figure 9. The shape of synthesized AgNPs was observed to be cylindrical and its size was 25 μm.

AFM scan of AgNPs synthesized from methanolic extract of Tropaeolum majus.

3.3 Biological activities

3.3.1 Antioxidant activity of AgNPs vs respective extract of T. majus

The free radical scavenging potential of the methanolic and aqueous extracts of T. majus versus their synthesized AgNPs is presented in Table 2. The maximum percent antioxidant potential was exhibited by aqueous extract of T. majus at all applied doses. This was found to be dose-independent, i.e. the scavenging ability was almost same at 20 µg/mL (minimum dose) to 150 µg/mL (maximum dose). The scavenging ability of AgNPs synthesized with aqueous extract was markedly reduced, but it has shown dose-dependent effect, i.e. 23.4% at 20 µg/mL (minimum dose) to 45% at 150 µg/mL (maximum dose). Similarly, methanolic extract has shown dose-dependent effect and is reduced in case of AgNPs. Our data exhibited that antioxidant potential of T. majus reduced when fabricated as AgNPs, probably the reducing phytochemicals would be consumed during metal reduction.

Antioxidant activity of T. majus extract and its synthesized AgNPs

| Conc. (µg/mL) | Percent DPPH (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous extract (%) | Aqueous AgNPs (%) | Methanolic extract (%) | Methanolic AgNPs (%) | |

| 20 | 96.5 | 23.4 | 7.7 | 42 |

| 40 | 94.9 | 23.9 | 10 | 12.2 |

| 60 | 93.7 | 26.6 | 24 | 11.7 |

| 80 | 93.6 | 34.7 | 31.6 | 9.5 |

| 100 | 92.2 | 40.6 | 45.1 | 5.4 |

| 150 | 90 | 45.7 | 49 | 4 |

3.3.2 Antibacterial activity

The synthesized AgNPs of various plants, such as Acalypha wilkesiana and Tithonia diversifolia, has been documented for antimicrobial potential [47,48,49]. To analyse the antibacterial effect of T. majus, crude and aqueous extracts and their AgNPs were screened against three strains of bacteria shown in Table 3. The antibacterial effect was compared to standard drug of Streptomycin. The aqueous and methanolic extract exhibited inhibition against Bacillus subtilis and their synthesized AgNPs were active against Staphylococcus aureus. Both the above-mentioned bacterial strains are gram-positive; however, the effect is far less than standard drug.

Antibacterial activity of T. majus extract and its synthesized AgNPs

| Microorganism strain | Gram stanning | Aqueous extract | Aqueous AgNPs | Methanolic extract | Methanolic AgNPs | Streptomycin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumonia | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | + | 0 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 28 |

| Bacillus subtilis | + | 10 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 28 |

4 Conclusion

Our data concluded that the extracts of T. majus have necessary capping and reducing agents which make it capable to develop stable AgNPs. The aqueous extract of T. majus has potential antioxidant effect; however, the AgNPs did not enhance its free radical scavenging effect. The bacterial strains’ susceptibility of the extract and AgNPs was changed from Bacillus subtilis to Staphylococcus aureus, respectively. The biological action of AgNPs is changed in case of antibacterial activity which means that AgNPs might change the specificity of T. majus and likewise other drugs.

-

Research funding: The work is funded by grand number 14-MED333-10 from the National Science, Technology and Innovation Plan (MAARIFAH), the King Abdul-Aziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. We thank the Science and Technology Unit at Umm Al-Qura University for their continued logistic support.

-

Author contributions: Saud Bawazeer: writing-original draft; Abdur Rauf: writing-review editing, methodology; Syed Uzair Ali Shah: formal analysis; Ahmed M. Shawky: visualization; Yahya S. Al-Awthan and Omar Salem Bahattab: English corrections of the manuscript; Ghias Uddin and Javeria Sabir: project administration; Mohamed A. El-Esawi: resources and proofreading of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

-

Conflict of interest: One of the authors (Abdur Rauf) is a member of the Editorial Board of Green Processing and Synthesis.

References

[1] Daniel AD, Sylvia U, Ute R. A historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Metabolites. 2012;2(2):303–36.10.3390/metabo2020303Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Veeresham C. Natural products derived from plants as a source of drugs. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2012;3(4):200–1.10.4103/2231-4040.104709Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Fabricant DS, Farnsworth NR. The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery. Env Health Persp. 2001;109(1):69.10.1289/ehp.01109s169Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Yadev D, Suri S, Choudhary AA, Sikender M, Hemant BMN. Novel approach, herbal remedies and natural products in pharmaceutical science as nano drug delivery systems. Int J Pharm Tech Res. 2011;3(3):3092–116.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Ratnam DV, Ankola DD, Bhardwaj V, Sahana DK, Kumar MN. Role of antioxidants in prophylaxis and therapy: a pharmaceutical prospective. J Control Rel. 2006;113:189–207.10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.04.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Kumar K, Rai AK. Miraculous therapeutic effects of herbal drugs using novel drug delivery systems. Int Res J Pharm. 2012;3:27–33.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Sharma AT, Mitkare SS, Moon RS. Multicomponent herbal therapy: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2011;6:185–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Saini R, Saini S, Sharma S. Nanotechnology: the future medicine. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(12):32–33.10.4103/0974-2077.63301Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Bionanotechnology. In: Ramsden JJ, Ed. Nanotechnology: an introduction. 2nd edn. United states of America: Elsevier; 2016. p. 358.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Rajiv S, Santosh S. Nanotechnology: the future medicine. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(1):32–3.10.4103/0974-2077.63301Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Raffaele C, Luca ID, Luise AD, Petillo O, Calarco A, Peluso G. New therapeutic potential of nanosized phytomedicine. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2016;16(8):8176–87.10.1166/jnn.2016.12809Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Chakraborty K, Shivakumar A, Ramachandran S. Nano-technology in herbal medicines: a review. Int J Herb Med. 2016;4(3):21–7.10.22271/flora.2016.v4.i3.05Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Mohan YM, Premkumar T, Geckeler KE. Fabrication of silver nanoparticles in hydrogel networks. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2006;2(27):1346–54.10.1002/marc.200600297Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Mazzocut A, Coutino-Gonzalez E, Baekelant W, Sels BF, Hofkens J, Vosch TJ. Fabrication of silver nanoparticles with limited size distribution on TiO2 containing zeolites. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:18690–3.10.1039/C4CP02238FSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Beer C, Foldbjerg R, Hayashi Y, Sutherland DS, Autrup H. Toxicity of silver nanoparticlesnanoparticle or silver ion? Toxicol Lett. 2012;208:286–92.10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Iravani S. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chem. 2011;13:2638–42.10.1039/c1gc15386bSuche in Google Scholar

[17] Makarov VV, Love AJ, Sinitsyna OV, Makarova SS, Yaminsky IV, Kalinina NO. Green nanotechnologies: synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Acta Naturae. 2014;6:35–44.10.32607/20758251-2014-6-1-35-44Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Seddik K, Smain A, Arrar L, Baghiani A. Effect of some phenolic compounds and quercus tannin on lipid peroxidation. World Appl Sci J. 2010;21(8):1144–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Bruneton J. Pharmacognosy, phytochemistry, medicinal plants. 2nd edn. Paris, Hampshire: Inter-cept Ltd., TecDoc, Lavoisier Publishing Inc.; 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Garzón GA, Wrolstad RE. Major anthocyanins antioxidant activity of Nas-turtium flowers, Tropaeolum majus. Food Chem. 2009;114:44–49.10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.09.013Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Niizu PY, Rodriguez-Amaya DB. Flowers leaves of Tropaeolum majus L. richsources of lutein. J Food Sci. 2005;70:S605–9.10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb08336.xSuche in Google Scholar

[22] Strzelecka H, Kowalski J, (Eds.). Encyklopedia zielarstwa i ziołolecznictwa. 1st edn. Warsaw: PWN; 2000. p. 365–6 (in Polish).Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Wojciechowska B, Wizner L. Cucurbitacines in Tropaeolum majus L. fruits. Herba Pol. 1983;29:97–101.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Fournie P, (Ed.). Le livre des plantes médicinales et vénéneuses de France. 1st edn. Paris: Paul Lechevalier; 1947 (in French).Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Corrêa MP. Dicionário das plantas úteis do Brasil e das exóticas cultivadas, vol. 2. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional; 1978. p. 67.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Ferreira RBG, Vieira MC, Zárete NAH. Análise de crescimento de Tropaeolum majus ‘jewel’ em func¸ ão de espac¸ amentos entre plantas. Rev Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais. 2004;7:57–66.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Ferro D. Fitoterapia: conceitos clínicos. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2006. p. 410.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Chevallier A. The encyclopedia of medicinal plants. London: Dorling Kindersley; 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Torres-Jimenez IB, Quintana-Cardenes IJ. Comparative analysis on the use of medicinal plants in traditional medicine in Cuba and The Canary Islands. Revista Cuba de Plantas Medicinales. 2004;9(1):lil-394333.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Duke JA, Ayensu ES. Medicinal plants of China. Michigan: Reference Publications Algonac; 1985.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Jens L, Birger LM. Synthesis of benzylglucosinolate in Tropaeolum Majus L. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:609–13.10.1104/pp.102.2.609Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Taylor RA, Otanicar TP, Herukerrupu Y, Bremond F, Rosengarten G, Hawkes ER, et al. Feasibility of nanofluid-based optical filters. Appl Opt. 2013;52(7):1413–22.10.1364/AO.52.001413Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Reiss Gunter, Hutten Andreas. Magnetic nanoparticles. In: Sattler KD, (Ed.). Handbook of nanophysics: nanoparticles and quantum dots. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2010. p. 1–2.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Khan FirdosAlam. Biotechnology fundamentals. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012. p. 328.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Belloni J, Mostafavi M, Remita H, Marignier JL, Delcourt AMO. Radiation-induced synthesis of mono- and multi-metallic clusters and nanocolloids. N J Chem. 1998;22(11):1239.10.1039/a801445kSuche in Google Scholar

[36] Pang YX, Xujin B. Influence of temperature, ripening time and calcination on the morphology and crystallinity of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2003;23(10):1697–704.10.1016/S0955-2219(02)00413-2Suche in Google Scholar

[37] NanoComposix. UV/Vis/IR spectroscopy analysis of nanoparticles. NanoComposix. 2012;1(1):1–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Khattak A, Ahmad B, Rauf A, Bawazeer S, Farooq U, Patel S, et al. Green synthesis, characterisation and biological evaluation of plant-based silver nanoparticles using Quercus semecarpifolia Smith aqueous leaf extract. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018;13(1):36–41. 10.1049/iet-nbt.2018.5063.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Islam NU, Jalil K, Shahid M, Rauf A, Muhammad N, Khan A, et al. Green synthesis and biological activities of gold nanoparticles functionalized with Willow Salix Alba. Arab J Chem. 2019;12(8):2914–25.10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.06.025Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Islam NU, Jalil K, Shahid M, Muhammad N, Rauf A. Pistacia integerrima gall extract mediated green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their biological activities. Arab J Chem. 2015;12(8):2310–19.10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.02.014Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Ahmad B, Hafeez N, Bashir S, Azam S, Khan I, Nigar S. Comparative analysis of the biological activities of bio-inspired gold nano-particles of Phyllantus emblica fruit and Beta vulgaris bagasse with their crude extracts. Pak J Bot. 2015;2(47):139–46.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phospomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic. 1965;16:144–58.10.5344/ajev.1965.16.3.144Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Barandozi NF. Antibacterial activities and antioxidant capacity of Aloe vera. Org Med Chem Lett. 2013;3:5. 10.1186/2191-2858-3-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Mistry B. A handbook of spectroscopic data chemistry: UV, IR, PMR, CNMR and mass spectroscopy. Gujrat: Oxford Book Company; 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Alfredo VNR, Victor SM, Marco CLA, Rosa GEM, Miguel CLA, Jesus AAA. Solventless synthesis and optical properties of Au and Ag nanoparticles using Camellia sinensis extract. Mater Lett. 2008;62:3103–5.10.1016/j.matlet.2008.01.138Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Abbasi Z, Feizi S, Taghipour E, Ghadam P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of dried Juglans regia green husk and examination of its biological properties. Green Process Synth. 2017;26:477–85.10.1515/gps-2016-0108Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Dada AO, Adekola FA, Dada FE, Adelani-Akande AT, Bello MO, Okonkwo CR, et al. Silver nanoparticle synthesis by Acalypha wilkesiana extract: phytochemical screening, characterization, influence of operational parameters, and preliminary antibacterial testing. Heliyon. 2019;5:10.10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02517Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Dada AO, Inyinbor AA, Idu EI, Bello OB, Oluyori AP, Adelani-Akande TA, et al. Effect of operational parameters, characterization and antibacterial studies of green synthesis of silver nanoparticles, using Tithonia diversifolia. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5865. 10.7717/peerj.5865.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Zaman K, Bakht J, Malikovna BK, Elsharkawy ER, Khalil AH, Bawazeer S, et al. Trillium govanianum wall. ex. Royle rhizomes extract medicated silver nanoparticles and their anti-microbial activity. Green Process Synth. 2020;9:503–14.10.1515/gps-2020-0054Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Saud Bawazeer et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis