Abstract

In order to solve the problems of depleting petroleum asphalt resources and deteriorating pollution of marine products, a systematic study was carried out on the application prospect of waste crab shell (WS) powder as asphalt modifier. In this study, the physical properties of WS powder modified asphalt (WSA) were tested by blending different contents of WS powder into matrix asphalt; the high and low temperature rheological properties of WS powder modified asphalt were characterized by using Dynamic shear rheometer, Bending beam rheometer, and Multiple stress creep recovery test. In addition, the microscopic chemical properties and modification mechanism were analyzed by Differential scanning calorimetry, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Atomic force microscopy, and Scanning electron microscope. It was shown that the WS powder enhanced the viscoelastic properties, temperature sensitivity properties, and permanent deformation resistance of asphalt. In addition, there was no obvious chemical reaction between the WS powder and the matrix asphalt, and no new chemical substances were generated; at the microscopic level, the WS powder and the matrix asphalt had good compatibility. In conclusion, the use of WS powder as a bio-based asphalt modifier to improve the resources and environmental issues have certain prospects.

1 Introduction

When marine invertebrates are processed for use as food, the majority of them produce large volumes of waste. Currently, the primary source of food waste among marine invertebrates is crabs. Worldwide, an estimated 6–8 million tons of crab waste are discarded each year, seriously polluting the ecosystem [1,2]. But landfilling or incineration continue to be the primary methods of handling these shell wastes. The environment and human health are negatively impacted by large amounts of accumulated shell wastes that serve as breeding grounds and homes for mosquitoes and flies [3]. Because of this, academics and policymakers are now compelled to explore other waste treatment solutions [4]. Global sustainability and waste reduction trends necessitate more effective recycling of waste biomaterials from the seafood sector and aquaculture development [5]. The circular economy can make effective use of waste crab shells (WS) by heat treating them or turning them into mechanical powders [6]. Large amounts of chitin and its derivatives are harvested from crab and shrimp shells in modern industry [7].

One method of converting trash into treasure is the extraction of chitin from leftover crab shells. Proteinase K and Bacillus coagulants LA204 can be used to remove chitin from discarded crab shell powder by eliminating Ca2+ and protein. After 48 h of fermentation at 50°C, the recovery of chitin, demineralization efficiency, and deproteinization efficiency were 94, 91, and 93%, respectively [8]. Chitin is utilized in adsorbent materials, biodegradation, biocompatibility, and tissue engineering because of its porous structure [9,10]. WSs can yield chitosan by the process of deacetylation of chitin [11], a crucial chemical raw material. WSs can yield chitosan, a crucial raw material for the chemical industry, through the process of deacetylating chitin. As novel europium ion biosorbents, crab shell powder and chitosan nanoparticles can effectively adsorb europium from aqueous solutions [12,13]. Moreover, chitosan microspheres and leftover crab shells may quickly absorb and remove organochlorine pesticides from aqueous solutions [14]. Some studies have demonstrated by comparing several adsorbents that the removal capacity and initial removal rate of heavy metals in aqueous solution are ranked as WSs > cation exchange resin > zeolite > powdered activated carbon granular activated carbon [15].

WSs have a plethora of medicinal uses. Through heat treatment, crab shells have been effectively recycled as seafood waste into biomaterials. These high-quality, super-crystalline apatite-based biomaterials have proven to be instrumental in the use of bone and dental implants [16]. Additionally, it has been established that hydroalcoholic crab shell extracts inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells by increasing apoptosis and decreasing NO production in breast cancer cell lines. Spent crab shells are traditional medicines for the treatment of cancer [17]. Shrimp and crab shell waste has substantial use as a particular culture media. WSs have the potential to be used in the production of functional foods because Bacillus licheniformis OPL-007 can biodeproteinize shrimp head waste (SHW) and increase its antioxidant activity. Bacillus licheniformis culture medium containing SHW as a carbon and nitrogen source has been shown to have antioxidant activity [18]. Furthermore, when Aspergillus erythropolis CRC31499 was cultivated in a medium containing wasted crab shell meal, it produced antimicrobial chitinase [19,20,21].

Crab shell waste can be used in a variety of various industries, including building and agriculture. Adding WS meal to the two-stage green waste composting process can quickly raise the quality of the compost products [22]. For non-structural uses, seashell trash can be utilized as a partial aggregate to match the ease of usage and strength of concrete [23]. Mangrove crab shells from Merako can serve as a basic bioceramic raw material [24]. Increased precision in the identification of sulfides in gas samples is obtained when powder traps made of porous crab shell is utilized [25]. In addition to Marine derived waste, some plant waste is also used to modify the properties of asphalt mixtures. Some scholars have used olive husk ash to modify asphalt and asphalt mixture, and found that olive shell ash can reduce the penetration of asphalt and increase the softening point, and improve the strength and water stability of asphalt mixture [26,27,28].

Scientists have created a variety of bio-based asphalt modifiers to address the issue of conventional petroleum-based asphalt that is not renewable. By adding poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate, which is naturally formed by microorganisms multiplying in wastewater treatment plants, to asphalt, some researchers have had positive results [29]. Furthermore, biobased asphalt modifiers increase asphalt’s service life. The aging period of base bitumen is prolonged by bio-based modified bitumen, which is produced by substituting 30% of bitumen with lignin [30]. By giving reactive H atoms to react with O2 and free radicals, catechins isolated from plants, such as tea, stop asphalt molecules from oxidizing and aging chemically [31]. It is evident that the aging process of asphalt is largely influenced by the adsorption of H atoms by oxygen or free radicals. Additionally, because phenolic hydroxyl groups are very effective at immobilizing H atoms, they attract oxidants and interact with them to stop oxidants from removing H atoms from asphalt. Quercetin exhibits superior anti-aging properties than lignin due to its greater phenolic hydroxyl concentration [32]. The low-temperature mechanical properties of asphalt mixes were enhanced by substituting rosin esters of maleic anhydride, which are produced from plant resins in the Pinaceae family, for alcohol curing agents, thereby resolving the environmental issues associated with polyurethane and epoxy resin curing agents [33]. The lignin that Dutch scientists are currently utilizing to manufacture lignin-based asphalt has been estimated to lower carbon emissions by 45% and environmental expenses by 60% for the same weight of asphalt produced [34]. When substituting traditional matrix asphalts with bio-based phenolic resins made from waste bio-oils, it has been discovered that higher construction temperatures are necessary; however, rutting resistance at high temperatures has been significantly enhanced [35]. Furthermore, some scholars have done research on the asphalt modifier of waste shrimp shell powder, and the results show that waste shrimp shell powder can improve the rutting resistance and creep recovery performance of asphalt mixture. Similarly, there are also attempts to use waste oyster powder as asphalt modifier [36]. The main component of waste oyster powder is calcium carbonate, which mainly acts similar to mineral powder in asphalt modification [37].

In conclusion, the creation of ecologically safe and sustainable asphalt modifiers has gained popularity in the pavement building industry. Nevertheless, the research works on Marine derived organic waste mainly focus on the modified asphalt of waste shrimp shell powder and waste oyster powder, and the research on waste shrimp shell powder and waste oyster powder have not conducted in-depth studies on the storage stability and microscopic morphology of modified asphalt. In this study, Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Atomic force microscopy (AFM) were specially added to address the above deficiencies, in order to reveal the modification mechanism of WS powder on asphalt from a microscopic perspective. Moreover, there is a lack of systematic research on the modification mechanism and effectiveness of WS powder modified asphalt, and there is a lack of published literature on the research of WS powder modified asphalt. Because of this, this study adopts the physical properties and softening point difference experiments to study the conventional properties and storage stability of different dosages of WS powder modified asphalt; the use of Dynamic shear rheometer (DSR), Bending beam rheometer (BBR), and Multiple stress creep recovery (MSCR) experiments to study the shear and high and low temperature rheological properties of different dosages of WS powder modified asphalt, as well as the creep recovery performance; through the Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to characterize different dosages of WS powder modified asphalt, the glass transition point, and chemical functional groups; finally, the micro-morphology and micro-structure of the modified asphalt with different dosages of WS powder were investigated from a microscopic point of view by using AFM and SEM; meanwhile, the effects of different dosages of WS powder on the modified asphalt modification were compared. In order to provide new ideas for the research and production of bio-based modified asphalt, to open up the situation for the promotion of WS powder as treasure, and to better protect the ecological environment around the Earth’s oceans and seas, this study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the performance of modified asphalt with WS powder, with a view to provide data support for the application of WS powder.

2 Materials and experiment methods

2.1 Materials

The asphalt that was chosen is 90# matrix asphalt, which is made in China at Panjin Asphalt Plant. The matrix asphalt’s characteristics are listed in Table 1 according to the Chinese technical specification (JTG E20-2011).

Technical index of base asphalt

| Technical index | Test results | Technical requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Penetration (25°C) (0.1 mm) | 85 | 80–100 |

| Solubility (%) | 99.63 | ≥99.5 |

| Kinetic viscos (60°C) (P·s) | 178 | ≥160 |

| Softening point (°C) | 46.8 | ≥45 |

| Ductility (15°C) (cm) | >100 | ≥100 |

| Flash point (°C) | 276 | ≥245 |

A selection of WS powder was made in Hohhot, China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. After being cleaned with tap water, it was dried for 12 h at 100°C in an oven. Following grinding with a grinder, particles larger than 0.15 mm were removed by sieving. Particles smaller than 0.15 mm in size were retained. The sample is shown in Figure 1(a).

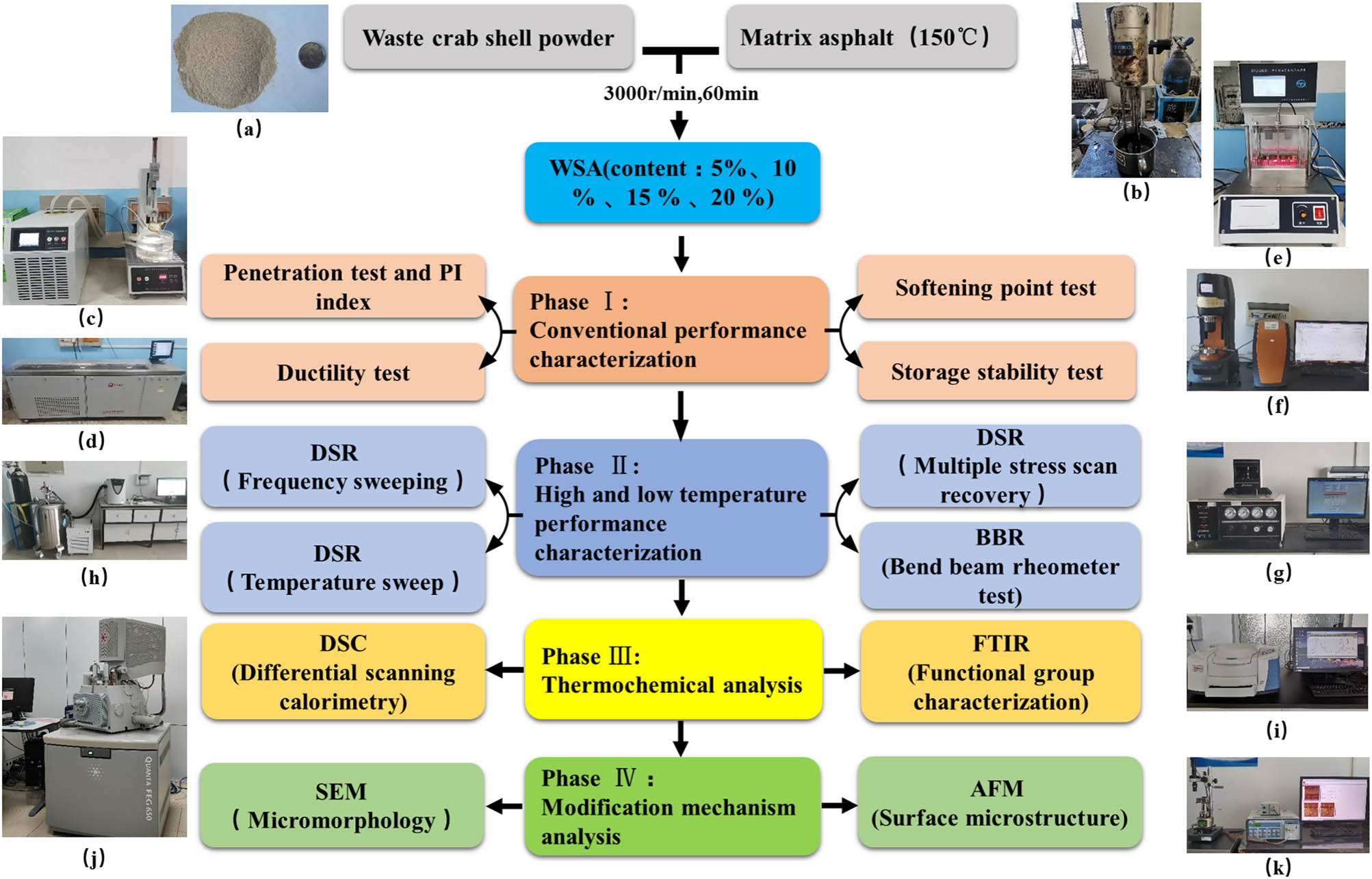

Research methodology flowchart. (a) Sample of WS powder, (b) asphalt high-speed shear machine, (c) penetrometer, (d) ductility machine, (e) softening point tester, (f) rotary shear rheometer, (g) low-temperature BBR, (h) differential scanner, (i) infrared spectrum scanner, (j) SEM, and (k) AFM.

2.2 Preparation of the modified asphalts

A high-speed shear shown in Figure 1(b) was used in the laboratory to make WS powder modified asphalt. The base asphalt was heated to 150°C in an oven, and then 5, 10, 15, and 20% (mass percentage) of WS powder modifier was added to the base asphalt. The mixture was then mixed at 150°C for 60 min at a speed of 3,000 rpm. This constituted the preparation procedure.

2.3 Test methods

The experimental flow chart of this study is shown in Figure 1. According to the national standard (JTG E20-2011), needle penetration, softening point, and ductility tests were performed on asphalt binders to assess the physical qualities of asphalt treated using WS powder. The above devices are respectively shown in Figure 1(c) and (e). Temperatures for the needle penetration test were 15, 25, and 30°C; for the ductility test, the temperature was 15°C. Take the logarithm of the penetration values tested under temperature conditions of 15, 25, and 30°C, with y = lg P and x = T. Perform a linear regression of the y = a + bx univariate equation to obtain the penetration temperature index A lgPen. Determine the penetration index (PI) of asphalt according to formula (1), and record as PI.

where lg P is the logarithm of penetration values measured under different temperature conditions; T is the test temperature (°C); K is a constant term of regression equation a; A lgPen is the coefficient b of the regression equation.

Under the AASHTO T315 standard shown in Figure 1(f), the high temperature rutting resistance of WS meal modified asphalt was investigated using a DSR (Gemini II ADS), which measured parameters including complex modulus, loss modulus, phase angle δ, and |G*|/sin δ. With temperature increments of 2°C per min, high temperature scanning tests were conducted in the 46–70°C range. We used samples that had a 1 mm gap and a diameter of 25 mm. Additionally, the frequency was consistently maintained at 10 rad·s−1.

In frequency scan tests, the mechanical response of temperature with loading frequency was measured at 46, 52, 58, 64, and 70°C. WS meal modified bitumen was subjected to dynamic shear loads at modest strain levels (1%), with loading frequencies ranging from 0.1 to 100 rad·s−1.

MSCR test evaluates the stress effects and elastic recovery of repetitive asphalt loading and unloading. As a result, the MSCR test offers a more thorough analysis of its deformation properties under dynamic loading. The evaluation index is unrecoverable creep compliance. For the MSCR test, the test temperature is 58°C.

BBR test was carried out in compliance with ASTM D6648-2008 (R2016) guidelines shown in Figure 1(g). The tests were carried out from −34 to −16°C in order to determine the low-temperature rheological properties of the bitumen treated with crab shell powder. To test the creep stiffness and creep rate of the beams throughout loading times ranging from 8 to 240 s, a continuous load of 980 mN was applied.

An apparatus from TA Instruments, USA, model Q20 shown in Figure 1(h) was used to conduct the DSC investigation. Since the samples’ precision did not exceed 51 mg, their weight was ascertained using a balance (1/10,000 g). The samples were first heated to room temperature in the DSC, then chilled to −20°C at a rate of 10°C·min−1 and held for 1 min, and finally heated to 225°C at a rate of 10°C·min−1 while being exposed to purge gas for 2 min. There was a last DSC curve. The glass transition temperature (T g) was calculated from the DSC test curve, and the glass transition process was examined using the DSC data.

The functional groups of modified bitumen can be characterized through the use of FTIR testing [38]. Using NEXUS 870FT FIRT shown in Figure 1(i), spectrums of modified bitumen made from WS meal at several doses were gathered. With a resolution of 4 cm−1, the test was conducted over a scanning region of 500–4,000 cm−1.

Tests using AFM with a 15 µm × 15 µm scanning area were conducted at 25°C. A Quanta 200 SEM shown in Figure 1(k) and made by FEI, USA was used to analyze the microstructural features of the bitumen affected by WSs. Using Gwyddion software, the AFM pictures were quantitatively analyzed, and the roughness value was chosen as a quantitative index.

The surface morphology of WS powder and the adhesion of crab shell to asphalt were tested by using the United States FEI QUANTA 650 FEG SEM, as shown in Figure 1(j). In order to observe the adhesion interface between the asphalt and the crab shell, a small amount of asphalt was dropped on the unground WS and the sample was placed in the oven at 135°C for 2 h, so that the asphalt and the WS were fully integrated.

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Conventional physical performance and softening point difference experiment

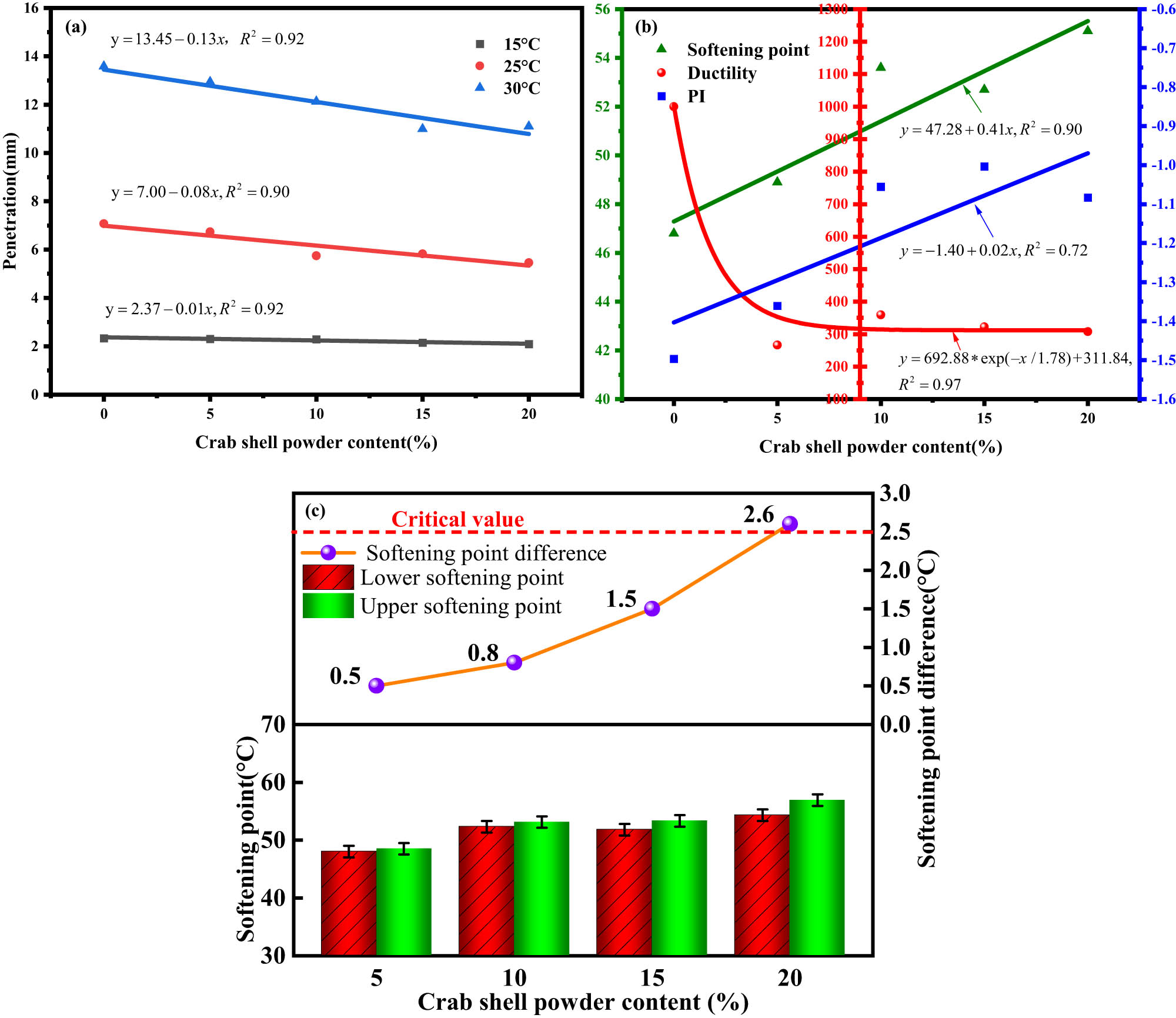

The three basic indexes of needle penetration, ductility, and softening point were used to evaluate the change rule of the performance of WSA with different doping amounts. The storage stability of crab shell powder modified asphalt was evaluated by referring to the softening point difference test in ASTM D5976. The heat storage time was 48 h. Softening point difference is negatively correlated with the uniformity of modified asphalt. The smaller the softening point difference is, the less easily the modified asphalt is separated. The basic indexes of WSA are shown in Figure 2.

Physical properties of WSA with different contents. (a) Penetration; (b) softening point, ductility, PI; and (c) softening point difference.

The needle penetration of WSA at 15, 25, and 30°C is shown in Figure 2(a). When doping is increased at 15°C, needle penetration decreases relatively slowly; when temperature rises, on the other hand, needle penetration decreases more quickly, with 30°C showing the quickest rate of reduction. The needle penetration of WSA fell by 13.03, 22.80, and 18.37% at 15, 25, and 30°C, respectively, when the WS content was 20%. As a result, WS powder enhanced 90# asphalt’s consistency. The softening point of WSA rises as the WS content does, as seen in Figure 2(b). When compared to 90# asphalt, the 20% content WSA has a 17.85% greater softening point at 55.12°C. The better the asphalt’s ability to sense temperature, the higher the PI value. The PI value increases linearly with the quantity of mixing, as shown in Figure 2(b), suggesting that WS benefits 90# asphalt. It should be noted that only the ductility data fit curve is curved, and that the rate of ductility decline is rather rapid in the early stages before tending to level off at 15% dosage. It is evident that WS decreases 90# asphalt’s low-temperature performance and has a larger impact on the ductility of the asphalt. This could be as a result of the WS particles influencing the way asphalt deforms during tensile contraction, which has a somewhat detrimental effect on asphalt viscosity. In conclusion, WS significantly enhanced 90# asphalt’s temperature-sensitive and high-temperature performance while reducing its low-temperature performance.

It can be seen from Figure 2(c) that the softening point difference of the modified asphalt with 5, 10, 15, and 20% crab shell powder is 0.5, 0.8, 1.6, and 2.6°C, respectively, and the softening point difference of the modified asphalt with crab shell powder increases with the addition amount. When the content of crab shell powder is 20%, the softening point difference reaches 2.6°C, which exceeds the specified standard of modified asphalt (2.5°C). This is because the more the amount of crab shell powder is added, the more serious the accumulation phenomenon of crab shell powder in asphalt, resulting in segregation. Therefore, the content of crab shell powder should not exceed 20% as far as possible.

3.2 Temperature sweep

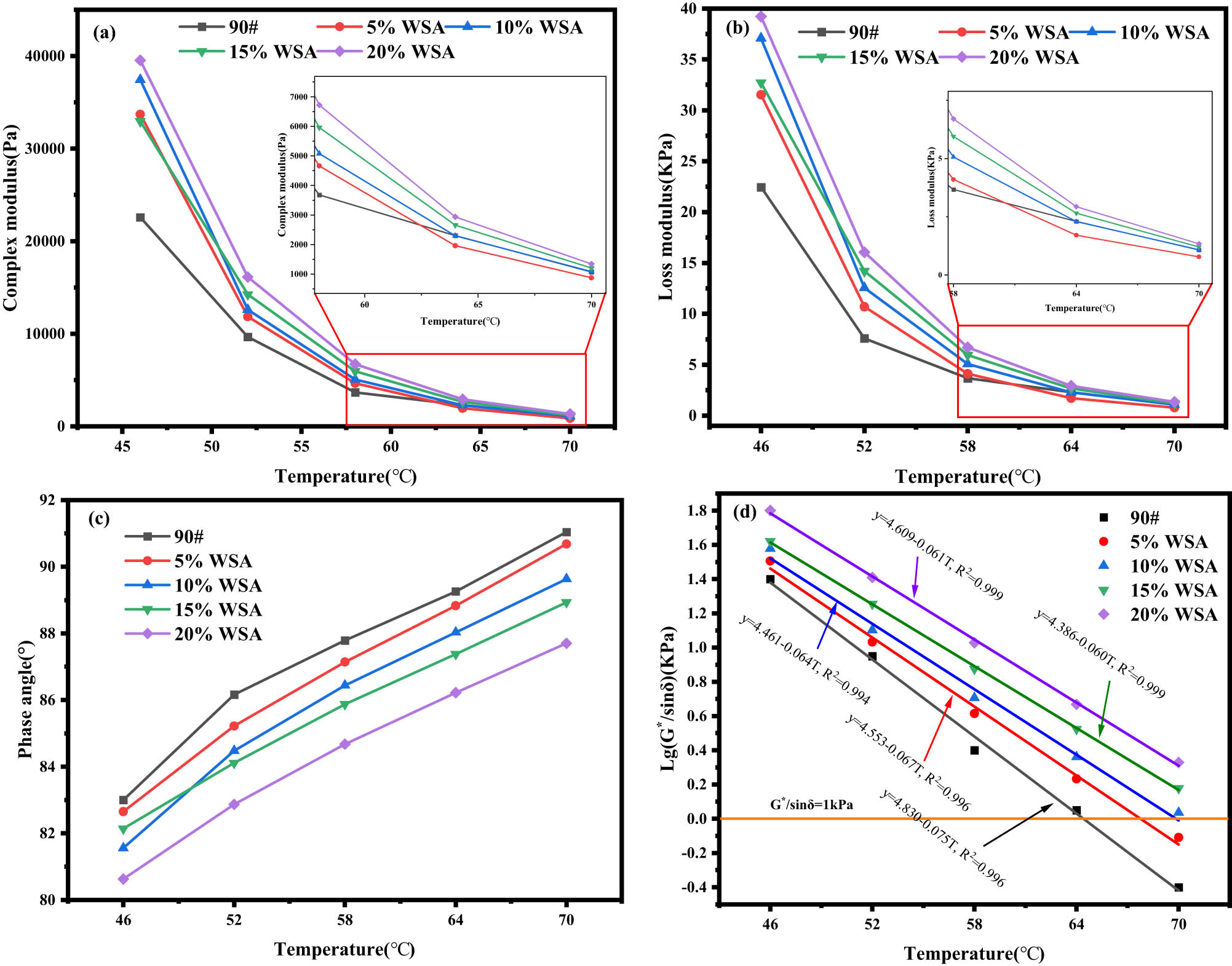

The Test Procedure for Asphalt and Bituminous Mixtures in Highway Engineering (JTG E20-2011) was adhered to for both sample preparation and testing. The goal of this experiment is to investigate the high-temperature performance of WSA. The angular frequency parameter is set to 10 rad·s−1, with a test applied strain of 1%, and a temperature scanning range of 46–70°C. Figure 3 illustrates how temperature affects WSA’s dynamic mechanical reaction.

Rheological properties of WSA at different temperatures; (a) Complex modulus; (b) loss modulus; (c) phase angle; and (d) rutting sensitivity.

In general, as temperature rises, matrix asphalt stiffness steadily decreases. Research has demonstrated that the complex modulus and loss modulus, respectively, are indicative of the stiffness and viscosity of matrix asphalt [39]. The viscoelasticity of the asphalt binder diminishes with increasing temperature, as observed in Figures 3(a) and (b), suggesting that the addition of WS does not alter the viscoelasticity law of the base bitumen. As the amount of WS incorporation grew, so did the base bitumen’s complex modulus and loss modulus.

The asphalt binder’s percentage of viscous and elastic components is characterized by the phase angle δ. This binder typically demonstrates coexisting viscous and elastic viscoelastic qualities [40]. Additionally, the asphalt binding material is more elastic when the phase angle δ is smaller. Figure 3(c) illustrates that δ increases with temperature in all asphalt binders. As the WS content increases at constant temperature, the phase angle δ decreases, making the modified bitumen more elastic.

The rutting factor (G*/sin δ) is a superior indicator of the asphalt binder’s resistance to permanent deformation, according to research from the strategic highway research program [41]. Furthermore, the researchers concluded that the binder’s temperature sensitivity is accurately characterized by the slope of the logarithm of the rutting factor vs the test temperature. WSA with 20% WS doping exhibited the highest rutting resistance across all temperature circumstances, as illustrated in Figure 3(d). Matrix bitumen exhibited the largest slope value, indicating the highest temperature sensitive. This suggests that the high-temperature rutting resistance of WSA is significantly enhanced by any addition of WS.

The physical characteristics and microstructure of WSA are likely intimately linked to the aforementioned observations. To put it another way, WS just serves as filler and spatial site resistance particles in WSA, which raises the asphalt’s viscosity by strengthening the molecules’ resistance to thermal movement. Because of WS’s strong mechanical strength, the asphalt binder’s elasticity ratio is improved, lowering the WSA loss factor.

3.3 Frequency sweep

Figure 4 displays the results of frequency scanning of WSA with varying quantities of blending in order to assess the fluctuation of matrix asphalt with loading frequency following WS blending.

Dynamic shear modulus of WSA based on frequency sweep. (a) 46°C; (b) 52°C; (c) 58°C; (d) 64°C; and (e) 70°C.

The primary indicator of traffic load duration on asphalt pavement is frequency; the higher the frequency, the shorter the loading time. When the frequency is low and the loading time is lengthy, the higher deformation of the asphalt binder owing to shear stress results in a reduced complex modulus. The complex modulus rises and the shear stress-induced deformation reduces with increasing frequency. According to Figure 4, the complex modulus of WSA with varying dose rises as loading frequency increases, suggesting that asphalt’s high temperature properties also rise as loading frequency increases. Each asphalt binder’s complex modulus value drops as temperature rises. When WS powder was added to the control asphalt binder at the same temperature, the asphalt binder’s complex modulus rose. This suggests that the deformation capacity of matrix asphalt to withstand traffic loads at high temperatures can be enhanced by addition of WS powder. Consequently, incorporating WS powder can enhance matrix asphalt’s performance at elevated temperatures.

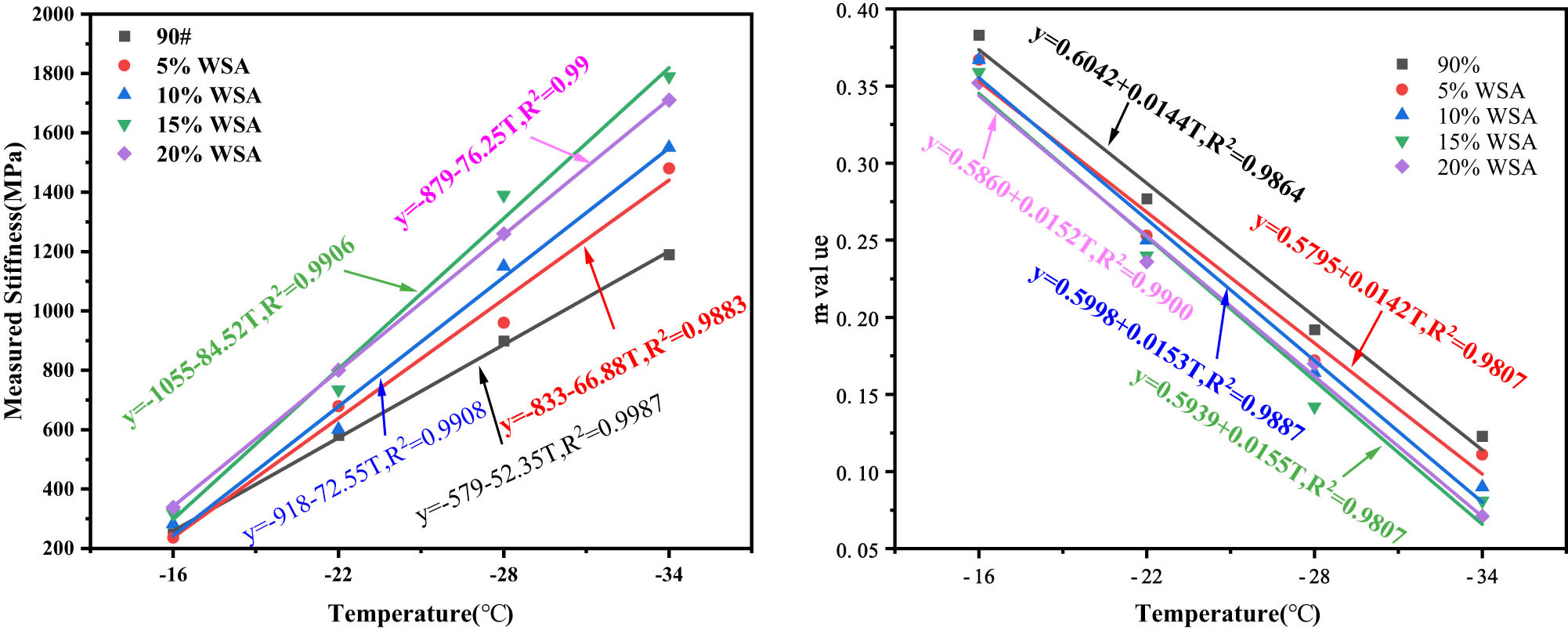

3.4 Results and analysis of the BBR test

The creep modulus S and creep rate m of asphalt treated with varying doses of crab shell powder were tested using the asphalt bending beam rheological test to assess the asphalt’s resilience to cracking at low temperatures. S stands for the asphalt binder’s constant load resistance measure, which indicates the material’s capacity to withstand long-term deformation. M represents the change in the asphalt binder’s stiffness as a function of load, which shows how the material’s stiffness changes over time and how well stress relaxation works. The smaller the value of S, the better the low-temperature flexibility of asphalt; the larger the value of m, the better the stress relaxation ability and crack resistance of asphalt. The creep modulus S and creep rate m of asphalt with different dosages of WSA are shown in Figure 5.

Morphology of WSA at different dosages.

The BBR test measures the extent to which the asphalt binder creeps at low temperatures under steady load conditions. As illustrated in Figure 5, the S and m values of various dosages of modified asphalt at −16, −22, −28, and −34°C show that creep strength increases with decreasing temperature, while creep rate decreases with decreasing temperature. This demonstrates that as the temperature drops, the resistance of asphalt with varying dosages to low-temperature deformation decreases as well. This occurs because, at low temperatures, asphalt is in a glassy state where its molecular chains are nearly fixed and cannot be readily reoriented or changed.

In comparison to matrix asphalt, WSA’s modulus of strength progressively increased and its m-value progressively decreased at the same temperature. At 15% dosage of WS powder, the lowest m-value and highest modulus of strength were observed. Additionally, it was discovered that the modulus of strength and m-value of WSA followed a linear trend after being linearly fitted. As the dose of WS powder increases, the slope of the modulus of strength gradually rises, reaching its maximum value at a 15% dosage. That is to say, as the dosage increases, the stiffness modulus and low-temperature performance of WSA decrease at an accelerated rate. It is evident that the WS meal somewhat reduces asphalt’s resistance to cracking at low temperatures. The extremely rough surface of the crushed WS meal may cause this effect by obstructing the interaction between asphalt molecules.

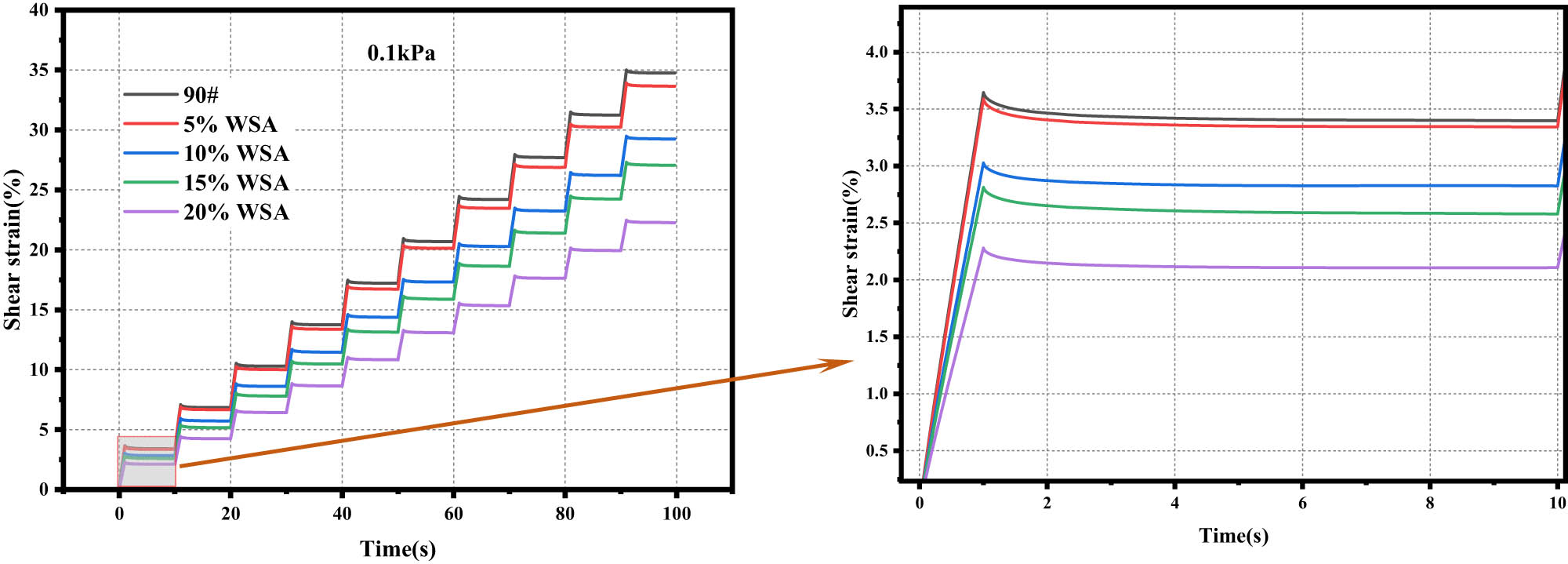

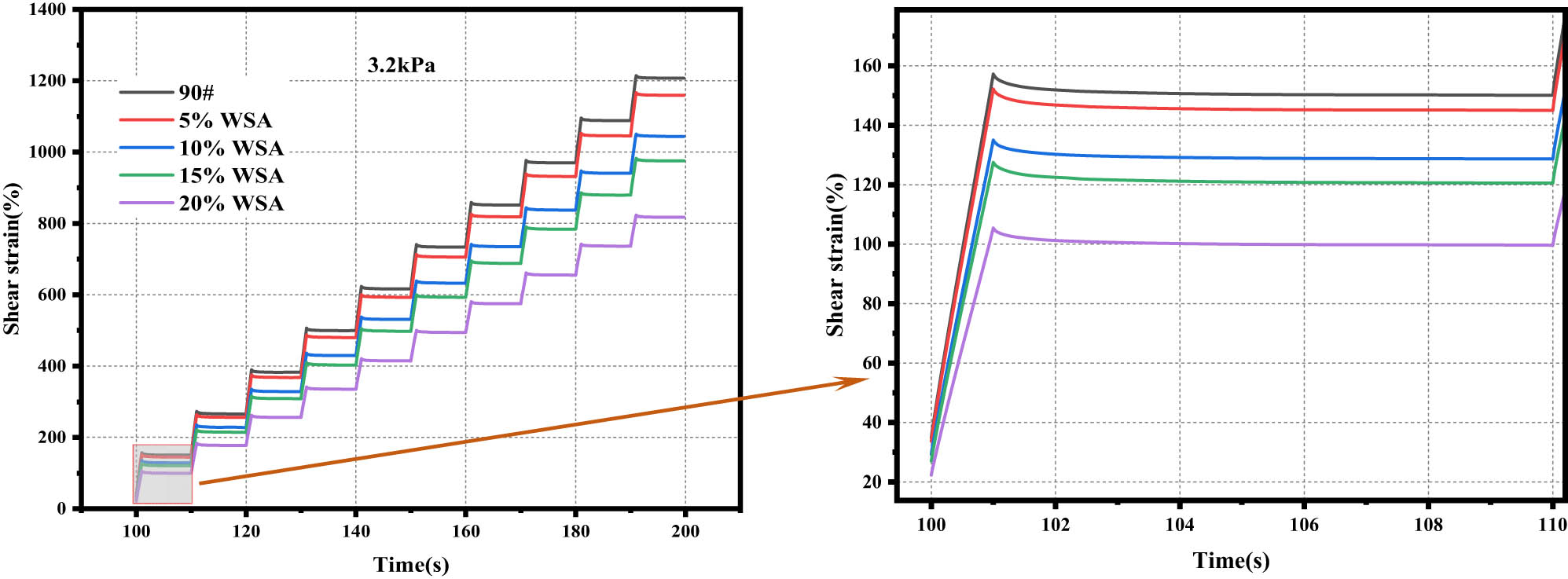

3.5 Results and analysis of the MSCR test

WS powder modified asphalt was subjected to MSCR tests, with a test temperature of 58°C, in order to examine the irrecoverable creep flexibility (J nr) and creep recovery (R) of WSA under high temperature conditions. While the high stress level (3.2 kPa) more closely approximates the behavior of asphalt under heavy traffic, the low stress level (0.1 kPa) better captures the elasticity and permanent deformation resistance of WSA. Figures 6 and 7 present the MSCR test results for WSA.

Creep recovery curves of WSA at 0.1 kPa stress level.

Creep recovery curves of WSA at 3.2 kPa stress level.

The creep and recovery findings for asphalt treated with varying amounts of discarded crab shell powder at 0.1 and 3.2 kPa are presented in Figures 6 and 7. The strain of all WSA specimens at 3.2 kPa is clearly more significant than the strain at 0.1 kPa, indicating that deeper rutting deformation in asphalt pavement corresponds to higher traffic loads. However, regardless of the shear stress level, the strain of virgin asphalt was higher than that of WSA, suggesting that WSA can considerably lower the strain of virgin binder.

Figure 8 displays the asphalt binder’s unrecoverable creep flexibility (J nr) and rate of return (R). R is able to describe the elastic content of the binder, while J nr is able to assess the rutting deformation. Better elasticity and resilience to rutting are found in binders with low J nr and high R. As the stress in Figure 8 is increased from 0.1 kPa to 3.2 kPa, J nr increases and R decreases, suggesting that the low stress levels contribute in the asphalt pavement’s permanent deformation resistance.

J nr and R of WSA.

Meanwhile, it was discovered that virgin asphalt’s R was increased by WS powder. Compared to the matrix asphalt, the R of the 5, 10, 15, and 20% dosages increased by 3.4, 7.1, 24.6, and 21.4%, respectively, under 0.1 kPa loading stress. The R of various WSA doses rose by 5.8, 5.3, 21.5, and 19.5%, respectively, at a loading stress of 3.2 kPa as compared to matrix asphalt. Stated differently, the creep recovery of WSA outperforms that of the virgin binder. The J nr of WSA is less than that of virgin asphalt, as Figure 8 illustrates. The J nr of various WSA doses at 0.1 kPa were 3.1, 15.8, 22.2, and 35.9% less than that of virgin asphalt, respectively. In the meantime, at 3.2 kPa, the J nr of various WSA doses was 4.0, 13.4, 19.1, and 32.2% lower than that of virgin binder. These findings demonstrate that, at high temperatures, discarded crab shell powder can improve matrix asphalt’s resistance to permanent deformation.

3.6 Results and analysis of the DSC test

DSC tests were conducted for various dosages of WSA in order to investigate the glass transition temperature (T g) of asphalt amended with WS powder. Figure 9 shows the DSC curves for matrix asphalt and modified asphalt with varying amounts of WS powder. The glass transition temperature is determined by taking the midpoint of the first-order heat flow temperature curve.

T g is recognized as the transition temperature at which the macromolecular segments of an amorphous polymer shift between highly elastic and glassy states. This temperature is the point at which the polymer shows elasticity; below it, brittleness and brittle fracture are observed [42]. Consequently, an asphalt’s performance at low temperatures improves with a lower T g value.

The glass transition temperatures of WS powder modified asphalt with a dose of 5, 10, 15, and 20% are −4.17, −4.56, −3.52, and −3.09°C, respectively, as can be seen from Figure 9. The glass transition temperature of matrix asphalt is −6.48°C. The glass transition temperatures of the asphalt modified by WS meal were found to be higher than those of the matrix asphalt. This suggests that adding WS meal to asphalt can raise its glass transition temperature and cause a reduction in its low-temperature performance.

DSC curves of WS modified asphalt. (a) 0%; (b) 5%; (c) 10%; (d) 15% and (e) 20%.

It is important to note that, similar to the DSC test results, the WSA ductility test results indicated a decline in ductility values relative to the matrix bitumen. The asphalt has higher molecular stability and cross-linking, which results in a decrease in T g. In conclusion, the WS meal marginally decreased the matrix asphalt’s performance at low temperatures.

3.7 Functional group characterization

An investigation into the modification method of WS powder modified bitumen was conducted using Fourier infrared spectroscopy test. The location of the distinctive peaks was used to analyze the WS powder’s chemical reaction mechanism and identify any alterations to its functional groups. Figure 10 displays the test results for modified asphalt with varying dosages of WS powder and matrix asphalt.

IR spectra of matrix asphalt and WSA.

The same peak types and positions are seen in the IR spectral test results of matrix asphalt and WSA without dosing, as shown in Figure 10. However, there is some fluctuation in the peak value, which is related to variations in the dosage of WS meal. The presence of hydroxyl groups and N–H bonds is linked to the transmittance drop at 3,475 m−1. The stretching vibrations of CH2 and CH3, which correlate to the alkyl functional groups of the bitumen, are responsible for the two significant absorption peaks at 2,928 and 2,856 cm−1, respectively. The C–H bonds in the bitumen matrix have an impact on the transmittance in the 2,900–2,400 cm−1 region. Furthermore, the C–N bond that the chitin created is linked to the decreased transmittance in the 1,462 cm−1 region. The most important characteristic of the C–H out-of-plane bending vibration in the 1,4-disubstituted aromatic ring is the ability to couple the backbone vibrations of CH3 in the aromatic ring at 2,928 and 2,856 cm−1 to the absorbance near 773 cm−1. This indicates that the bitumen CH3 is in the alkyl group in the asphalt. The WS powder and the matrix asphalt did not appear to undergo any discernible chemical reaction that produced new chemical components; instead, the transformation that occurred was primarily physical, as revealed by the results of IR spectroscopy.

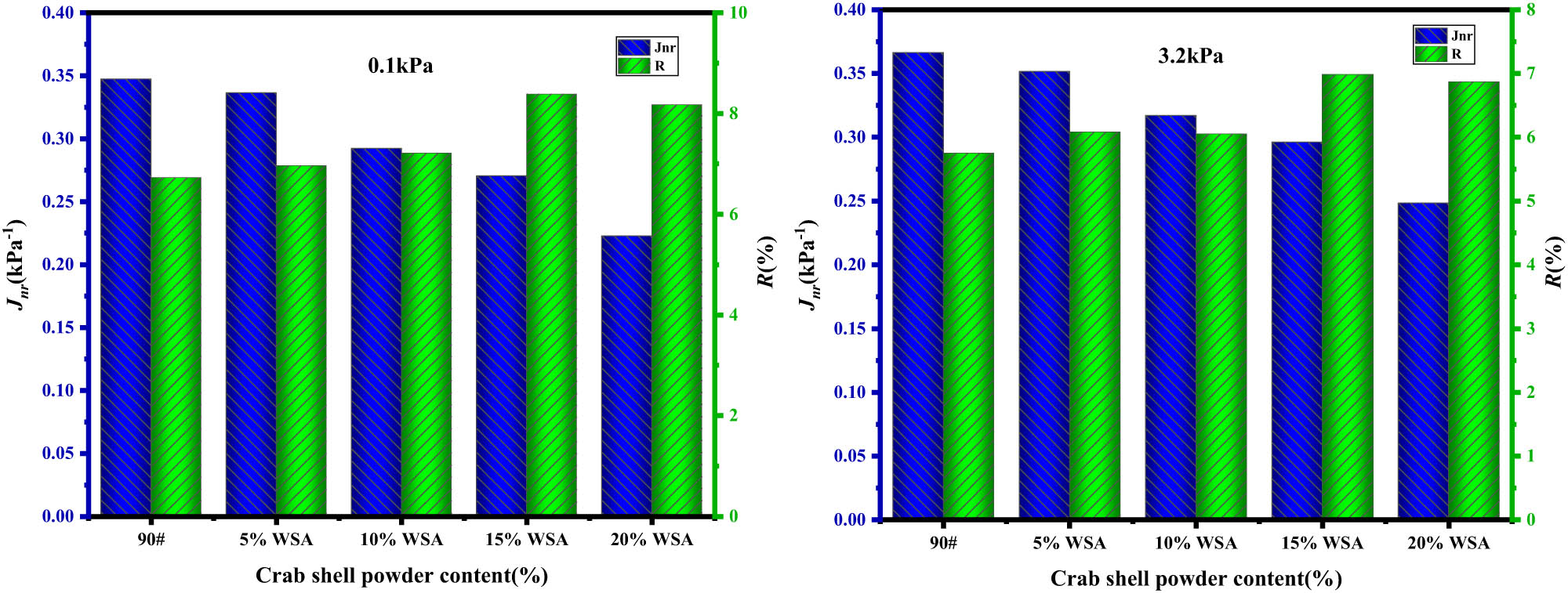

3.8 Microscopic morphology in WSA

The use of Atomic force microscopy to test and analyze the changes in the micro-morphology of different dosages of WS powder modified asphalt is necessary because the micro-morphological structure of asphalt is complex and changes in the microstructure will have a greater impact on the macroscopic properties of asphalt. Figure 11 displays the two- and three-dimensional atomic force diagrams of WS powder modified asphalt in different dosages.

Morphology of WSA with different dosages.

The term “honeycomb structure” refers to an oval-shaped stripe pattern that resembles a bee’s tail. The influence of the honeycomb structure is mostly related to the asphaltene in the asphalt since the polarity of asphalt is mostly caused by heterocyclic atoms in the asphalt. The “honeycomb structure” of asphalt modified with varying dosages of WS powder is evident from the two-dimensional atomic force diagram in Figure 11. As the dosage of WS powder is increased, the “honeycomb structure” per unit area exhibits a decreasing trend and becomes more evenly distributed on the asphalt’s surface, reflecting the asphalt’s homogeneous polarity, which is primarily due to the heterocyclic atoms in the asphalt. The asphalt surface exhibits improved compatibility, reflecting the WS powder and matrix asphalt without any exclusion features. Additionally, the microstructure of asphalt changed to varying degrees as WS powder doping increased, significantly impacting on the material’s surface roughness and related modulus. There is a good correlation between asphalt adhesion and roughness, and the greater the roughness, the worse the adhesion of asphalt [43]. The nanoscale spatial structure of the asphalt surface is more clearly depicted in Figure 11’s three-dimensional atomic force diagram. The asphalt surface is covered in many bumps and depressions, and its folds progressively increase as dosage increases. This could be the result of hydrogen bonding between the many hydroxyl groups in the chitin found in crab shell meal and the hydroxyl groups in the phenolic and carboxylic acids in the asphalt, which strengthens the bonds between the macromolecules in the asphalt and gives it a more wrinkled appearance. This would imply that the WS powder improves the high-temperature stability of the matrix asphalt. In summary, the AFM results demonstrate that the WS powder enhances the asphalt’s performance at high temperatures and exhibits good compatibility with the matrix asphalt. This is in line with the findings of the frequency and temperature scans.

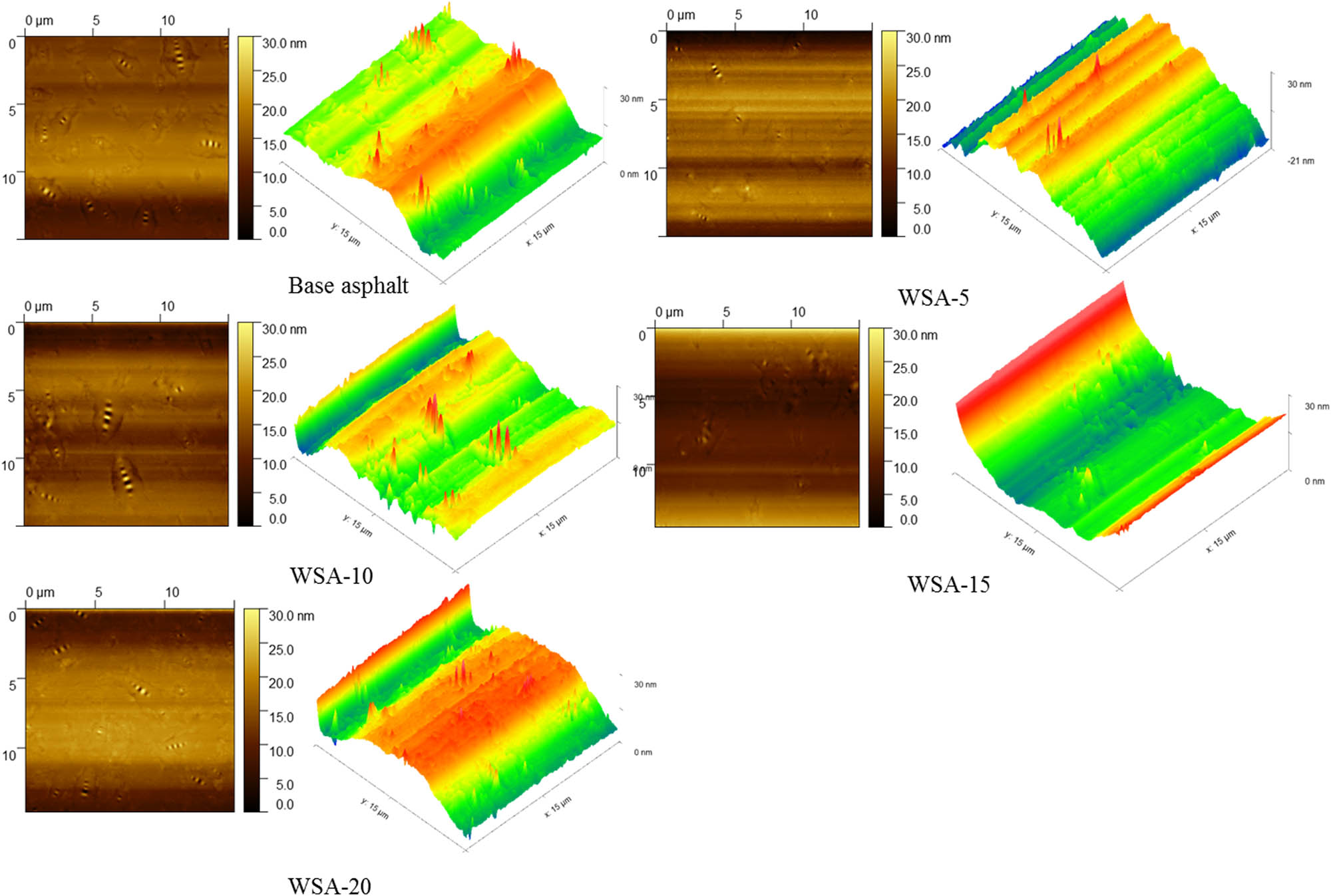

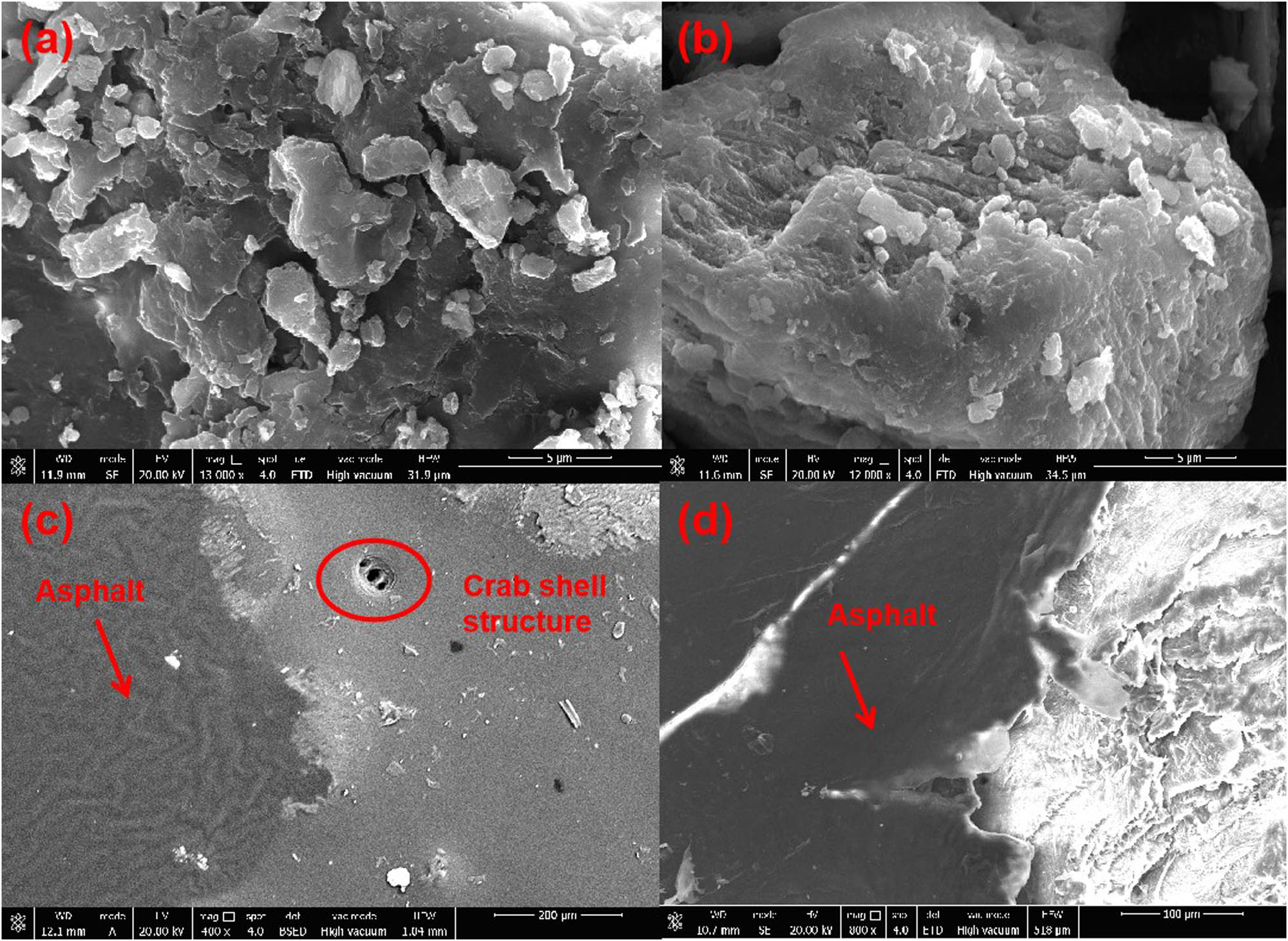

3.9 Adhesion of asphalt to WSs

In order to study the interaction between the asphalt and the crab shell, the surface morphology of the WS powder and the adhesion between the crab shell and the asphalt were tested by using the United States FEI QUANTA 650 FEG SEM. Figure 12 shows the SEM image of WS powder and the interaction interface between crab shell and asphalt.

SEM images of WS powder particles and adhesion of waste crab shell to asphalt. (a and b) WS microscopic morphology; (c) adhesion morphology of asphalt and crab shell surface; and (d) adhesion between asphalt and crab shell fracture surface.

Figure 12(a) and (b) are the SEM images of the WS powder after grinding, in which it can be seen that the surface of the WS powder is uneven and very rough, with an irregular layered structure in general, which is conducive to the adhesion between the asphalt and the WS powder. In order to observe the adhesion interface between the asphalt and the crab shell, a small amount of asphalt was dropped on the unground WS and the sample was placed in the oven at 135°C for 2 h, so that the asphalt and the WS were fully integrated. Figure 12(c) and (d) are SEM images of the interface between asphalt and WSs. In Figure 12(c), the irregular stripes on the left are the asphalt adhering to the WS, and the bare crab shell is on the right. It can be seen from the figure that the asphalt and the crab shell are closely fused, and the transition from the asphalt area to the crab shell area is smooth and natural. The difference between Figure 12(c) and (d) is that the crab shell fracture surface is on the right and the asphalt adhesion surface is on the left. The crab shell fracture surface is extremely rough, while the area on the left that is adhered by the asphalt is relatively smooth. Therefore, SEM shows that the surface of the crab shell powder after grinding is very rough, which is conducive to the adhesion of asphalt. At the same time, both the smooth area and the broken area of the WS adhere closely to the asphalt, thus changing the performance of asphalt.

4 Conclusion

There are few systematic studies on the modification of base asphalt by WS powder, while the studies on the modification of asphalt by marine-derived waste focus on waste shrimp shell powder and waste shell powder. In this study, the potential of WS powder as asphalt modifier is systematically evaluated, which provides data support for the promotion of WS powder as asphalt modifier, and can also reduce the increasingly serious environmental pollution caused by marine-derived waste. The effects of WSA on rheological properties, modification mechanism, and microscopic characteristics of asphalt at high and low temperatures were analyzed. It was found that the consistency and rutting resistance of asphalt modified by WS powder were improved, and the following preliminary conclusions could be drawn:

The addition of WS powder can raise the glass transition temperature of asphalt, which lowers the asphalt’s resistance to cracking at low temperatures. It also improves the high temperature viscoelasticity and temperature sensitivity of 90# asphalt.

The permanent deformation resistance of matrix asphalt against traffic loads at high temperatures is enhanced by WS meal modified asphalt. WS meal modified asphalt exhibits superior rutting resistance and elastic recovery as compared to virgin binder.

The waste powder from crab shells does not appear to undergo any discernible chemical reaction with the matrix asphalt, mostly resulting in a physical alteration. The WS powder enhances the asphalt’s performance at high temperatures and, at the microscopic level, is well suited to the matrix asphalt.

The high temperature performance of crab shell modified asphalt is outstanding, so it is suggested to apply crab shell modified asphalt to asphalt pavement projects in tropical areas. In addition, crab shell powder, as a low-cost kitchen waste or seafood waste, has a good application prospect for improving resources and environment.

In this study, the effect of WS powder on the properties of base asphalt was mainly studied. However, the research on the properties of WS powder on asphalt mixture has not been carried out, including the high and low temperature properties, water stability, anti-aging ability and fatigue properties of WS powder modified asphalt mixture will be the next research direction. From the perspective of research scale, the modification mechanism of WS powder on asphalt mixture should be revealed from the macro, fine, and micro levels. From the consideration of construction application, the response surface method should be used to optimize the mix ratio of WS powder modified asphalt mixture, so as to design asphalt pavement with excellent performance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the sponsorship from the Scientific research project of Inner Mongolia University of Technology (ZY202014).

-

Funding information: This work describes the research activities funded by the Scientific Research Project of Inner Mongolia University of Technology (ZY202014).

-

Author contributions: Material preparation, data collection, analysis, and the first draft were done by Han Biao, with Xing Zhang and Lingyu Zhang participating in part of the experiment, and the other authors all commenting and suggesting on the manuscript version. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Yan, N. and X. Chen. Sustainability: don’t waste seafood waste. Nature, Vol. 524, No. 7564, 2015, pp. 155–157.10.1038/524155aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Shi, W., B. Chang, H. Yin, S. Zhang, B. Yang, and X. Dong. Crab shell-derived honeycomb-like graphitized hierarchically porous carbons for satisfactory rate performance of all-solid-state supercapacitors. Sustainable Energy & Fuels, Vol. 3, No. 5, 2019, pp. 1201–1214.10.1039/C8SE00574ESuche in Google Scholar

[3] Li, H. Y., Y. Q. Tan, L. Zhang, Y. X. Zhang, Y. H. Song, Y. Ye, et al. Bio-filler from waste shellfish shell: preparation, characterization, and its effect on the mechanical properties on polypropylene composites. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 217–218, 2012, pp. 256–262.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.03.028Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Leng, Z., R. K. Padhan, and A. Sreeram. Production of a sustainable paving material through chemical recycling of waste PET into crumb rubber modified asphalt. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 180, 2018, pp. 682–688.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.171Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Ogresta, L., F. Nekvapil, T. Tamas, L. Barbu-Tudoran, M. Suciu, R. Hirian, et al. Rapid and application-tailored assessment tool for biogenic powders from crustacean shell waste: Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy complemented with X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. ACS Omega, Vol. 6, No. 42, 2021, pp. 27773–27780.10.1021/acsomega.1c03279Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Nekvapil, F., M. Aluas, L. Barbu-Tudoran, M. Suciu, R.-A. Bortnic, B. Glamuzina, et al. From blue bioeconomy toward circular economy through high-sensitivity analytical research on waste blue crab shells. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Vol. 7, No. 19, 2019, pp. 16820–16827.10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b04362Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Metin, C., Y. Alparslan, T. Baygar, and T. Baygar. Physicochemical, microstructural and thermal characterization of chitosan from blue crab shell waste and its bioactivity characteristics. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, Vol. 27, No. 11, 2019, pp. 2552–2561.10.1007/s10924-019-01539-3Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Dun, Y., Y. Li, J. Xu, Y. Hu, C. Zhang, Y. Liang, et al. Simultaneous fermentation and hydrolysis to extract chitin from crayfish shell waste. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Vol. 123, 2019, pp. 420–426.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.088Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Zhu, P., Z. Gu, S. Hong, and H. Lian. One-pot production of chitin with high purity from lobster shells using choline chloride-malonic acid deep eutectic solvent. Carbohydrate Polymers, Vol. 177, 2017, pp. 217–223.10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Samadi, F., A. Sarafraz-Yazdi, and Z. Es’haghi. An insight into the determination of trace levels of benzodiazepines in biometric systems: use of crab shell powder as an environmentally friendly biosorbent. Journal of Chromatography B: Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences, Vol. 1092, 2018, pp. 58–64.10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.05.046Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Kumari, S., S. H. Kumar Annamareddy, S. Abanti, and P. Kumar Rath. Physicochemical properties and characterization of chitosan synthesized from fish scales, crab and shrimp shells. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Vol. 104, 2017, pp. 1697–1705.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.119Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Cadogan, E. I., C.-H. Lee, S. R. Popuri, and H.-Y. Lin. Efficiencies of chitosan nanoparticles and crab shell particles in europium uptake from aqueous solutions through biosorption: Synthesis and characterization. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, Vol. 95, 2014, pp. 232–240.10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.06.003Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Vijayaraghavan, K. and R. Balasubramanian. Single and binary biosorption of cerium and europium onto crab shell particles. Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 163, No. 3, 2010, pp. 337–343.10.1016/j.cej.2010.08.012Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Lu, L. C., C. I. Wang, and W. F. Sye. Applications of chitosan beads and porous crab shell powder for the removal of 17 organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in water solution. Carbohydrate Polymers, Vol. 83, No. 4, 2011, pp. 1984–1989.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.11.003Suche in Google Scholar

[15] An, H. Crab shell for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solution. Water Research, Vol. 35, No. 15, 2001, pp. 3551–3556.10.1016/S0043-1354(01)00099-9Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Bhattacharjee, B. N., V. K. Mishra, S. B. Rai, O. Parkash, and D. Kumar. Structure of apatite nanoparticles derived from marine animal (Crab) shells: an environment-friendly and cost-effective novel approach to recycle seafood waste. ACS Omega, Vol. 4, No. 7, 2019, pp. 12753–12758.10.1021/acsomega.9b00134Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Rezakhani, L., Z. Rashidi, P. Mirzapur, and M. Khazaei. Antiproliferatory effects of crab shell extract on breast cancer cell line (MCF7). Journal of Breast Cancer, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2014, pp. 219–225.10.4048/jbc.2014.17.3.219Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Mao, X., P. Liu, S. He, J. Xie, F. Kan, C. Yu, et al. Antioxidant properties of bio-active substances from shrimp head fermented by Bacillus licheniformis OPL-007. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Vol. 171, No. 5, 2013, pp. 1240–1252.10.1007/s12010-013-0217-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Wang, S. L., W. J. Hsiao, and W. T. Chang. Purification and characterization of an antimicrobial chitinase extracellularly produced by Monascus purpureus CCRC31499 in a shrimp and crab shell powder medium. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 50, No. 8, 2002, pp. 2249–2255.10.1021/jf011076xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Wang, S. L., I. L. Shih, T. W. Liang, and C. H. Wang. Purification and characterization of two antifungal chitinases extracellularly produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens V656 in a shrimp and crab shell powder medium. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 50, No. 8, 2002, pp. 2241–2248.10.1021/jf010885dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Wang, S.-L., T.-C. Yieh, and I.-L. Shih. Production of antifungal compounds by pseudomonas aeruginosa K-187 using shrimp and crab shell powder as a carbon source. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, Vol. 25, No. 1–2, 1999, pp. 142–148.10.1016/S0141-0229(99)00024-1Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Zhang, L. and X. Sun. Effects of bean dregs and crab shell powder additives on the composting of green waste. Bioresource Technology, Vol. 260, 2018, pp. 283–293.10.1016/j.biortech.2018.03.126Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Mo, K. H., U. J. Alengaram, M. Z. Jumaat, S. C. Lee, W. I. Goh, and C. W. Yuen. Recycling of seashell waste in concrete: a review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 162, 2018, pp. 751–764.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.009Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Haryati, E., K. Dahlan, O. Togibasa, and K. Dahlan. Protein and minerals analyses of mangrove crab shells (scylla serrata) from Merauke as a foundation on bio-ceramic components. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 1204, 2019, id. 012031.10.1088/1742-6596/1204/1/012031Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Sye, W.-F., Y.-C. Chen, and S.-F. Wu. Evaluation of natural porous crab shell powder used for the enrichment of sulfur compounds from gaseous samples. Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society, Vol. 50, No. 1, 2003, pp. 73–79.10.1002/jccs.200300010Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Haddad, M. A. and T. S. Khedaywi. Moisture resistance of olive husk ash modified asphalt mixtures. Annales de Chimie Science des Matériaux, Vol. 47, No. 3, 2023, pp. 141–149.10.18280/acsm.470303Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Khedaywi, T. S., M. A. Haddad, A. N. S. Al Qadi, and O. A. Al-Rababa’ah. Investigating the effect of addition of olive husk ash on asphalt binder properties. Annales de Chimie Science des Matériaux, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2021, pp. 239–243.10.18280/acsm.450307Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Al Qadi, A. N. S., T. S. Khedaywi, M. A. Haddad, and O. A. Al-Rababa’ah. Investigating the effect of olive husk ash on the properties of asphalt concrete mixture. Annales de Chimie Science des Matériaux, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2021, pp. 11–15.10.18280/acsm.450102Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Tabaković, A., J. Lemmens, J. Tamis, D. van Vliet, S. Nahar, W. Suitela, et al. Bio-polymer modified bitumen. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 406, 2023, id. 133321.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133321Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Gaudenzi, E., L. P. Ingrassia, F. Cardone, X. Lu, and F. Canestrari. Investigation of unaged and long-term aged bio-based asphalt mixtures containing lignin according to the VECD theory. Materials and Structures, Vol. 56, No. 4, 2023, id. 82.10.1617/s11527-023-02160-6Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Yang, F., Z. Hu, H. Xi, and B. Guan. Comparative investigation on the properties and molecular mechanisms of natural phenolic compounds and rubber polymers to inhibit oxidative aging of asphalt binders. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 2022, 2022, pp. 1–14.10.1155/2022/5700516Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Hu, D., X. Gu, G. Wang, Z. Zhou, L. Sun, and J. Pei. Performance and mechanism of lignin and quercetin as bio-based anti-aging agents for asphalt binder: a combined experimental and ab initio study. Journal of Molecular Liquids, Vol. 359, 2022, id. 119310.10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119310Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Sun, J., Z. Zhang, J. Ye, H. Liu, Y. Wei, D. Zhang, et al. Preparation and properties of polyurethane/epoxy-resin modified asphalt binders and mixtures using a bio-based curing agent. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 380, 2022, id. 135030.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135030Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Moretti, C., R. Hoefnagels, M. van Veen, B. Corona, S. Obydenkova, S. Russell, et al. Using lignin from local biorefineries for asphalts: LCA case study for the Netherlands. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 343, 2022, id. 131063.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131063Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Jiang, X., P. Li, Z. Ding, L. Yue, H. Li, H. Bing, et al. Physical, chemical and rheological investigation and optimization design of asphalt binders partially replaced by bio-based resins. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 350, 2022, id. 128845.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128845Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Lv, S., C. Xia, Q. Yang, S. Guo, L. You, Y. Guo, et al. Improvements on high-temperature stability, rheology, and stiffness of asphalt binder modified with waste crayfish shell powder. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 264, 2020, id. 121745.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121745Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Wang, X., Y. Guo, G. Ji, Y. Zhang, J. Zhao, H. Su, et al. Effect of biowaste on the high- and low-temperature rheological properties of asphalt binders. Advances in Civil Engineering, Vol. 2021, 2021, pp. 1–14.10.1155/2021/5516546Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Yan, C., W. Huang, J. Xu, H. Yang, Y. Zhang, and H. U. Bahia. Quantification of re-refined engine oil bottoms (REOB) in asphalt binder using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy associated with partial least squares (PLS) regression. Road Materials and Pavement Design, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2020, pp. 958–972.10.1080/14680629.2020.1861969Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Liu, J., P. Hao, B. Sun, Y. Li, and Y. Wang. Rheological properties and mechanism of asphalt modified with polypropylene and graphene and carbon black composites. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 12, 2022, id. 04022343.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0004513Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Zhao, Y., X. Gong, and Q. Liu. Research on rheological properties and modification mechanism of waterborne polyurethane modified bitumen. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 371, 2023, id. 130775.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130775Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Moreno-Navarro, F., M. Sol-Sánchez, F. Gámiz, and M. C. Rubio-Gámez. Mechanical and thermal properties of graphene modified asphalt binders. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 180, 2018, pp. 265–274.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.259Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Liu, H., Z. Zhang, Y. Zhu, J. Sun, L. Wang, T. Huang, et al. Modification of asphalt using polyurethanes synthesized with different isocyanates. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 327, 2022, id. 126959.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126959Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Zhang, X. and H. Feng. Microscopic characterization of adhesion properties of warm mix asphalt under ultraviolet aging. Journal of Changan University (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 40, No. 2, 2020, pp. 38–46.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures