Abstract

Credit accessibility is crucial for sustainable agricultural development. However, the difficulty in accessing credit has caused farmers to take many considerations when taking a loan. This research aims to determine the factors determining access and credit sources for cassava farmers in Lampung Province, Indonesia. Central Lampung was chosen as the research location because it had a total cassava production share of 36%. This study used Isaac’s and Michael’s formulae to determine the total samples. The data were collected by interviewing 263 respondents. Of 263 farmers, only 109 (41.4%) had access to loans. Data were analysed using the Multinomial Logit Regression Model to examine the factors determining access and credit sources for cassava farmers. Marginal effect analysis was also used to determine the probability of changes in independent variables. Regression results showed that the type of credit sources chosen by the farmers was determined by age, income, agribusiness experience, land size, education, organisation membership, and credit experience (R 2 = 89.1%). Partially, age, income, land size, education, credit experience, and business experience significantly influence the funding source. The results indicate that age, agribusiness experience, and land size are the main factors in choosing the types of credit. Land size has the biggest positive influence on farmers’ access to formal banks (11.49%).

1 Introduction

The agricultural sector is essential in the economic development of most developing countries, and smallholder farmers have an important role. However, minimum access to financing sources is one of the factors hindering farmers’ businesses’ growth and productivity [1]. Agricultural credit provision is the foundation of agricultural development in developing countries and thus should be the basic consideration for having the right agricultural development policies. The agricultural transformation from subsistence to commercial and climate change cause the agricultural industry to need bigger credit than other economic sectors. Agricultural credit becomes a crucial factor for sustainable agricultural development [2]. Access to agricultural credit helps develop the economy of rural areas, improves the socioeconomic condition of the farmers, and enables the sustainability of agricultural development [3,4]. Through better credit access, the farmers can improve agricultural technology, which sequentially increases productivity so that farmers’ income and marketing efficiency can also improve. Besides, through credit access, farmers can easily purchase what they need, employ workers, have the equipment, and develop seeds to improve productivity and food supply security [5]. One of the food crops in some countries, including Indonesia, is cassava. It is mostly planted today because of its adaptability to grow in various soil conditions and climates [6]. Cassava is now one of the important food crops commodities in Indonesia after rice, corn, soy peanut, and mung bean [7].

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is a tuber that can grow in tropical areas and is planted by more than 800 people [8]. Cassava is the main ingredient in some industries [9], so it has high economic value [10]. Cassava is traditionally processed by boiling it before being consumed. However, the development of cassava processing has varied in many countries and communities [11,12]. Cassava is a tuber food crop with high carbohydrates, an important resource for the industries of tapioca, biopolymer, farm feed, and ethanol [13]. Cassava essence can also be used in textile, paper, and other industries producing wood glue, veneer, glucose, and dextrin syrup [14,15]. Cassava essence is processed for flour and used as a substitute for wheat and rice-flour-based food, which inspired research on the economic feasibility of tapioca flour [16]. Its ability to be made into various products causes cassava to be increasingly planted by farmers. In the African Sub-Sahara, cassava is essential for the food security of millions of people and contributes to the development and potential income rise for smallholder farmers in Africa [17]. The sustainable agricultural product is paramount to avoiding food shortage and reducing poverty, impacting the income of smallholder farmers [18,19].

Based on the data on cassava area in 2014–2018, Indonesia was in the eighth position, with an average harvest area of 849,30 thousand hectares (3.79%) of the world’s total area of cassava harvest, making Indonesia the fifth biggest cassava producer globally after Nigeria, Kongo, Thailand, and Brazil. Indonesia’s average cassava is 20,13 million tons, with a market share of 7.04% [7]. Based on the data from Indonesia’s Ministry of Agriculture, Lampung Province is the biggest national cassava producer, with a harvest area of 208.000 hectares and a total product of 5.4 million tons. In 2020, Lampung Province contributed 25% of the total national cassava product, reaching 19 million tons [20]. Product increase can be done by choosing suitable quality varieties, such as those with longer growing times, roots lasting longer in the soil, and disease resistance [21]. Besides, product increases can also be done through capital or funding. Better loan access can improve farmers’ productivity [5].

As part of the ASEAN region, Indonesia has experienced a large economic expansion, but the paradigm of unsustainable growth can cause severe environmental damage. The sustainable development of Southeast Asia in the twenty-first century depends on creating a green economy in the region [22,23,24]. Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia are among the worst countries at the level of green economic development [25]. Meanwhile, Tasri [26] found that capital and economic openness positively influence green economic growth. So that with high capital, it will increase green economic growth, while Indonesia is the worst country in the level of green economic development; this shows that the available capital is low.

The World Bank reported a few aspects that threaten the development of the agri-food sector and food security, namely the accelerating pace of climate change, population growth and changes in dietary preferences, global pandemics, and conflict [27]. Fahad et al. [28] revealed that relying entirely on capital is one form of adaptation to climate change. Credit is an essential factor in agriculture and an effective way to develop rural areas [29]. Fahad et al. [30] reported the three most deficient sources of capital, one of which is financial capital, causing poverty. To smallholder farmers with limited capital and asset, access to external financing becomes a challenge and a problem in many developing countries [31]. Besides, the agricultural financing market and good institutional policies are integrated into the agricultural product supply chain. Government interference is crucial in guaranteeing a value chain that is efficient, fair, beneficial, and sustainable [32,33]. The program realisation is low compared to the financing commitment. The result of research [34] showed that the low realisation was caused by (1) high risk both to the banks and the debtors, (2) banks’ lack of understanding of the characteristics of business in the agricultural sector, and (3) financing pattern (instalment), which is not suitable to the pattern of business in the agricultural sector. Other factors influencing microcredit are collateral value, the need for capital, monthly income, and credit history [35]. The realisation of business credit is significantly influenced by the business turnover, the net income, the type of business, the amount of credit proposed, and the value of the collateral [36].

The agricultural market is unstable because of price fluctuation, which can vary up to 100% or more in the same season. The risk of soaring prices is when the market information is limited or when the market in a certain place is not connected to markets in other places. On the other hand, when the supply is bigger than the demand, the price will be lower, and the farmers will not be able to sell their products, declining their income. Therefore, bridging the financing gap for agribusiness runners should be a priority. Otherwise, the farmers will depend on an informal instrument that is easy to access and flexible but is inefficient and expensive with short timing; it also does not help transform subsistent farming into a profitable business [37]. Unfortunately, due to the challenges related to rural financing, most financial institutions are not interested in financing the farmers and other clients in rural areas because they represent an unfriendly, risky, and less beneficial market compared to urban clients [38].

Many researchers considered the lack of capital leading to other problems in agriculture, such as low technology adoption, lack of innovation, and the inability of business actors in this sector to increase their productivity and develop their businesses. Agribusiness financing remains a severe problem in the agricultural sector in developing countries. An institution in the financial sector in developing countries provides loans with a smaller portion than their credit portfolio to the agricultural sector compared to other sectors. Therefore, government interference is needed to help farmers and agribusiness actors to have better access to external financing sources, both monetary and non-monetary. In Indonesia, for instance, KUR (People’s Business Credit – Kredit Usaha Rakyat) financing through commercial banks has many requirements. KUR can only be given to prospective debtors who have never received financing from the bank, as proven by SID (Debtor information system). It becomes one of the hindrances of KUR realisation for the people and reduces the effect of the KUR distribution [39].

Farmers often struggle to get financing, so they find a way to fulfil it themselves. Farmers in northern Ghana use internal sources like savings, reinvestment of their previous harvest benefits, and income from selling other products as the dominant traditional financing sources. Besides, smallholder farmers also do daily labour in agriculture and non-agriculture sectors to increase their income. They are involved in the village saving and loan association to improve the chance of having credit access [40]. In the case of the Sidama coffee value chain in Ethiopia, the most used financing instrument is the informal model because it tends to be based on trust and mutual agreement [41].

The difficult access to financing causes farmers to have many considerations in choosing a financial institution when they want a loan for their cassava business. Many factors influence farmers in taking a loan and selecting financing institutions. The empirical analysis is necessary to identify the factors affecting access to financial services and how access to these services affects farmer productivity [42]. The result of the Chinwuba research showed that the factors influencing the choice of financing sources are gender, age, education, and experience in agribusiness. The research recommended that the government reduces the credit interest rate, especially in agribusiness [43]. Research in Indonesia proved that experience in agribusiness, credit history/track, and land size influence access to external financing sources [44].

Several studies have examined the factors influencing access to credit for farmers [29,43,44]. However, studies examining the factors influencing access to credit for cassava commodity farmers using multinomial logit analysis and margin effects are limited, especially for a province in a developing country, like Lampung, Indonesia. Thus, it is necessary to investigate factors influencing farmers in determining access to credit, how they influence, and to what extent they influence farmers in selecting the type of credit. This research analysed the factors influencing cassava agribusiness actors in selecting sources of business financing. It also analysed the extent these main determinants influenced farmers in selecting the type of credit.

2 Literature review

Financing agribusiness companies is a micro-study of how to provide capital, how it is used, and finally, how to control its use in agribusiness companies [45]. The primary reason agribusiness actors increase their financial resources is generally to increase revenue and profits by expanding their business [46]. There are two types of financing in the value chain: external and internal financing [47].

The Indonesian government has launched farmer credit/financing schemes to develop the economic sector. Bank Indonesia, through the implementing banks, has distributed capital credit to farmers, known as Food and Energy Security Credit (Kredit Ketahanan Pangan dan Energi – KKPE), Energy Development and Plantation Revitalization Credit (Kredit Pengembangan Energi dan Revitalisasi Perkebunan – KPEN-RP), Cattle Breeding Business Credit (Kredit Usaha Pembibitan Sapi – KUPS) and People’s Business Credit (Kredit Usaha Rakyat – KUR). These loans/loans are given to farmers and farmer groups and are channelled through savings and loan cooperatives or Credit Unions [48]. The perceptions of Indonesian farmers regarding agricultural credit/financing, especially KUR, are simple requirements, straightforward procedures, timely process, no additional collateral required, low interest, sufficient socialisation, no additional costs, and a funding ceiling as needed [49].

Access to credit affects farmers’ participation in cooperatives, but cooperatives can help them reduce production and marketing risks [50]. A study in northeastern Nigeria on watermelon farmers using multinomial logit analysis showed that they get loans based on their total revenue; the higher the revenue, the better the access to loans [51]. Farmers’ access to credit has a moderate positive relationship with better agricultural technology [52]. Furthermore, the binary logit model results showed that farmers with large farms, high agricultural income, better access to information, and ownership of large physical assets have a positive relationship with access to credit.

A previous study recommended that more credit should be given to older respondents with smaller family sizes and that credit institutions should reduce the lengthy process of obtaining loans from their institutions [29]. Credit provision can affect productivity. Access to credit positively increases cassava productivity [53]. Firms’ access to cost-effective credit facilities positively influences their productivity [54]. Another study assessing the impact of access to credit from Rural and Community Banks revealed that, on average, farmers who accessed credit had much higher technical efficiency than those who did not, indicating that access to credit has a positive impact on the technical efficiency of small-scale cassava farmers [55].

In practice, many factors influence access to credit, including farming experience, loan experience, and farming land area [44]. Access to credit for cassava farmers is influenced by several factors, namely educational status, years of farming experience, land area, net income of land, and previous loan payments [56]. Empirical findings [1] showed that marital status, land area, and interest rates all positively and significantly affect farmers’ choice of loan sources. In addition, annual farm income and interest rates significantly and positively impact access to credit. Household size, interest rates, farm size, asset value, and age are the main significant determinants of credit sources [29]. Another study found that the borrower’s age, household income, interest rates, and loan duration are the main determining factors affecting the accessibility of microcredit [57].

3 Material and method

3.1 Research location

The research location was determined using a multistage purposive method [58]. The first stage was purposively choosing Lampung Province as the research location, considering that Lampung is the biggest cassava producer in Indonesia. The second stage was determining a central cassava producer regency in Lampung Province, particularly the Central Lampung Regency. Based on the data from the Lampung Centre Bureau of Statistics (BPS) in 2020, Central Lampung produced 2.2 million tons of cassava, with a total production share of 36% [59]. Besides, cassava is a basic featured plant in Central Lampung with comparative advantages [60]. The next step was determining two districts in Central Lampung to represent the condition of the cassava agribusiness value chain in Lampung. The two chosen districts had the biggest cassava produce in Lampung, involving the flow of the value chain of the tapioca flour processing industry and cassava processing. The district representing the flow of cassava agribusiness value chain to be tapioca flour was Terbanggi Besar. Besides being the biggest cassava supplier in Central Lampung (524,000 tons), Terbanggi Besar district had four big tapioca factories. Meanwhile, the district representing the flow of the cassava value chain into a processed product other than tapioca was Seputih Banyak. This district had various cassava processing industries besides tapioca, for example, tapioca crisps, tiwul (traditional food made of cassava), tapioca chips, dry cassava milling, and concentrate milling. Seputih Banyak District produced more than 50,000 tons of cassava [61]. A map of the research location is presented in Figure 1.

Map of research location.

3.2 Data and sampling

The respondents were 263 farmers, randomly chosen from the list of farmers obtained from the agricultural extension worker. Primary data were collected through a face-to-face interview with a list of questions on the questionnaire. The questionnaire developed was previously piloted on 50 farmers who were not involved in the final survey. The final questionnaire was modified based on the pre-test survey. The questionnaires contained questions about farmers’ credit sources, information access to credit sources, social and economic conditions, and institutional factors. The total sample size for this research was calculated using Isaac and Michael’s formula in equation (1). This formula is used to calculate the sample when the number of the population is known [62].

where S is the number of samples;

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: This research has been granted ethics approval from the ethics committee at Universitas Gadjah Mada (approval number 6492/UN1/PN1.1/PN/PT.01.04/2022).

3.3 Research variables and theoretical framework

The statistical analysis used more than one independent variable to show a farmer’s access to credit. Credit sources were classified into banks, cooperatives, microfinancing institutions, middlemen, and other sources. The predictor variables for statistical analysis in this research were taken based on the previous research. Our empiric model includes farmers’ social and economic attributes and some technical factors and institutions which might influence the farmers’ access to agricultural credit and sources of credit. For instance, previous research showed that age, education, land size, information access, farmers, and asset status influence their access to credit [63]. Chinwuba et al. [43] reported that some determining variables are relevant to the access and choice of agribusiness financing, namely age, education, income, and organisation membership. Other factors are agribusiness experience, credit experience, land size [44], and value of asset ownership [64]. Another research revealed that the creditor’s age, family income, interest rate, and credit period are the determining factors influencing microcredit accessibility [57]. In addition, Dang et al. [65] showed that collateral, land size, income, procedure, literate, and all risk variables become dominant factors in deciding credit schemes. Farmers with big-scale agribusiness, high income, better information access, and high physical asset ownership have better access to credit [52].

Researchers try to combine those factors in one analysis model. This study focuses on the factors influencing the farmers’ access, credit sources, and their influence on agricultural technology adoption by farmers. The factors influencing the farmers’ access to financing in this research were age, education, income, organisation membership, agribusiness experience, credit experience, and land size, as presented in Table 1. Those factors were selected based on previous research [1,66,67,68,69], which also used an independent variable (Y) and an Independent variable (X) in their research.

Description of the research variables

| Variable | Label | Code | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | Kinds of financing sources | 1 | Formal Bank | |

| 2 | Cooperative | |||

| 3 | Microfinancing Institution | |||

| 4 | Middleman | |||

| 5 | Other sources | |||

| 6 | No sources | |||

| X1 | Age | Cassava farmers’ age | Year | |

| X2 | Education | 1 | No education | |

| 2 | Elementary school | |||

| 3 | Junior high | |||

| 4 | Senior high | |||

| 5 | Diploma | |||

| 6 | Undergraduate | |||

| X3 | Income | Cassava farmers’ income | Rp/Production | |

| X4 | Organisation Membership | 0 | No membership | |

| 1 | Cooperative | |||

| 2 | Farmers’ group | |||

| 3 | Farmer groups union | |||

| 4 | Arisan (rotating saving and credit group) | |||

| 5 | Others | |||

| X5 | Agribusiness experience | Length in Cassava Business | Year | |

| X6 | Credit experience | 0 | No credit | |

| 1 | Have credit | |||

| X7 | Land size | Cassava area size | Hectar |

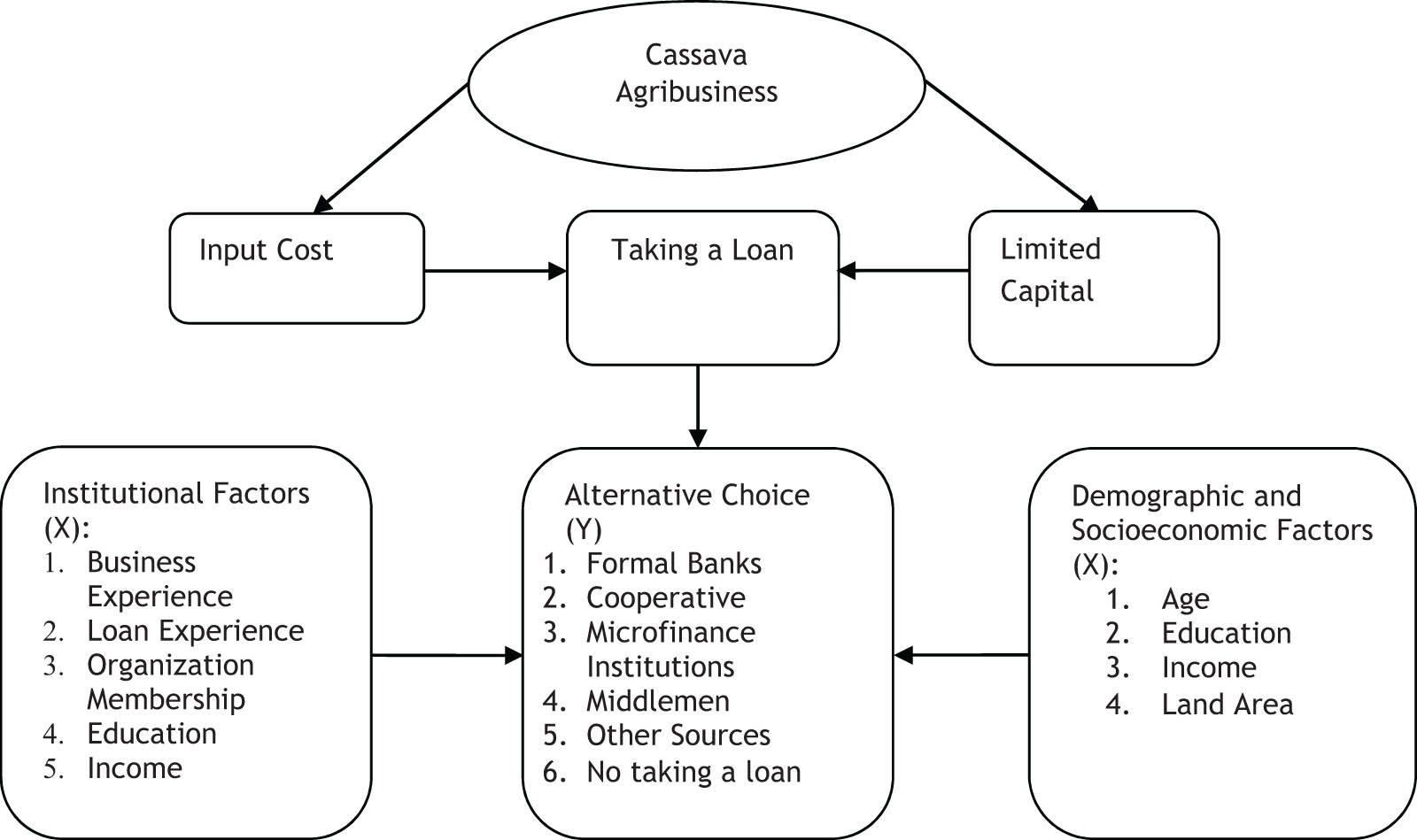

Based on the research variables determined and also the research background described earlier, a research framework was developed (Figure 2). The framework was adapted from previous research [70]. Figure 2 explains that cassava farming requires production costs incurred to purchase inputs. Due to the limited capital owned by farmers, farmers need to get a loan to buy inputs for cassava farming and to increase cassava productivity. There are several alternative sources of financing (Y): formal banks, cooperatives, microfinance institutions, middlemen, and other sources and not get loans. In choosing a source of financing, farmers are also influenced by several factors (X), such as age, education, income, membership in organisations, business experience, loan experience, and land area.

Theoretical framework.

3.4 Multinomial logit

The multicollinearity test was done before data testing using the multinomial logit model (MNL). Multilinearity cases are a case when there is a correlation between independent variables. For example, there is a correlation between X 1, X 2, …. and X n . The exact linear relationship between regressors is a serious failure from the model’s assumption, not from the data. Multicollinearity causes inaccuracy in inferring. Although there is no systematic bias in multicollinearity, checking estimation is done by VIF (Variance Inflation Factor), which is related to X h [71,72]:

Here, R h 2 is a square correlation from X h with other independent variables. So, the first step was finding the correlation coefficients between X 1 and X 2. The next step was to examine the VIF value. If the VIF value is greater than or equal to 10, multicollinearity is detected [73]. Multicollinearity is detected in the model if the VIF is greater than l0 and the tolerance is approaching 0 [74]. The provision of multicollinearity through VIF value is as follows:

If the value of VIF ≤ 10, then there is no multicollinearity.

If the value of VIF ≥ 10, then there is multicollinearity.

The multinomial logit model (MNL) is used to model the correlation between polytomous dependent variables (multiple choices) and a group of independent variables [43]. Some previous studies used binary logistic regression [52,56,57]. This research employed multinomial logistic regression. This model is broader than binary logistic regression, which includes dependent variables with two or more categories. MNL regression is used when the dependent variable has three or more categories [75]. Farmers could use various credit sources like banks, cooperatives, microfinance institutions, middlemen, and other sources, so the multinomial logit model was used to identify various credit sources used by the respondents. In the multinomial logit model, various credit sources were considered dependent variables. The independent variables included age, education, income, organisation membership, agribusiness experience, credit experience, and land size. The basic mathematical equation is presented in equation (3).

where j is the Financing alternative choice (1,2,3,…,j); i is the respondent no-i until n; Y is the dependent variable of possible financing choice by cassava farmers; X is the independent variable; β is the coefficient parameter. The independent variables are as follows:

X 1 is the age of cassava farmers

X 2 is the education of cassava farmers

X 3 is the income

X 4 is the organisation membership

X 5 is the business experience

X 6 is the credit experience

X 7 is the land size

MNL model was used to identify the determinants of farmers’ credit source because the dependent variable had more than two results. This study analysed multicollinearity and multinomial logit tests using SPSS 26.

3.5 Marginal effect

Marginal or probability effect is a function from the probability to measure the changes expected in certain category probability in relation to a unit change in an independent variable [76]. This Marginal effect counts the probability changes if there is a change in the independent variable [77]. The equation of the marginal effect is as follows:

STATA 14.2 was used to analyse the marginal effect. STATA 14.2 is an integrated complete statistic software with various features for data analysis, data management, and graphics [78].

4 Result and discussion

4.1 Sample’s general description

Table 2 presents the summary of the respondents in this study. Respondents were categorised into two groups: Farmers with access to loans and farmers who do not have access to loans. On average, the age of the farmers who do not have access to loans is older than the other group. Older farmers tend not to bother having credit compared to younger farmers, who are more open-minded. Previous research [79] showed that age has a significant negative influence. The educational level of the farmers with access to loans is also higher than that of those without. Most of the respondents’ education for those with access to loans is Senior High school. They tend to have a broader horizon compared to the other group with elementary school education.

General description of the sample and statistical summary

| Variable | Having credit | Not having credit | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ Social Economic Attribute | Mean | Mean | Percentage |

| Age | 46 | 47 | — |

| Education | SMA | SD | — |

| Business experience | 24 | 22 | — |

| Family members | 3 | 3 | — |

| Length of organisation experience | 13 | 12 | — |

| Land size | 2 | 1 | — |

| Reasons for not having credit | Total | Total | Percentage |

| Having own capital | — | 110 | 71.4 |

| Afraid to be involved in debt | — | 34 | 22.1 |

| Fear of Riba | — | 5 | 3.2 |

| Unable to pay | — | 5 | 3.2 |

| Credit source | Total | Total | Percentage |

| Bank | 55 | — | 20.9 |

| Cooperative | 14 | — | 5.3 |

| Micro Finance Institution | 18 | — | 6.8 |

| Middleman | 2 | — | 0.8 |

| Other sources | 20 | — | 7.6 |

| No credit | — | 154 | 58.6 |

Education influences agribusiness development; education contributes to the development by allowing farmers access to loans to develop their businesses [80]. Higher education positively influences their participation in agribusiness cooperatives [50]; it is also in line with their organisational experience, which has a positive influence. Respondents’ business experience is also longer for farmers with access to loans than those without. There is a positive correlation, the longer they run agribusiness, the more experience they have, and the better they know how to overcome problems, including finance. This finding aligns with previous research [81], revealing that running agribusiness experience positively influences farmers’ knowledge. With the same number of family members (three people), farmers with longer organisation experience tend to take a loan compared to those without organisational experience. It is because the longer they join an organisation, the more people they meet with whom they can share opinions. Ultimately, they become more open-minded and have a broader horizon. The respondents who take a loan also have larger farms than those without. The larger the farm they have, the more they need, so they need external financing. The large land they cultivate is a positive signal and has a significant influence on becoming commercial farmers [82].

Of the total respondents, 154 (58.6%) do not take a loan for various reasons. More than 70% of respondents said they do not take a loan because they have their capital prepared before becoming cassava farmers. Less than a quarter of the respondents said they are afraid of having debt as they were never in debt before. The rest said they fear riba (usury) and cannot pay the loan (3.2% for each category).

Respondents’ credit sources vary, including banks, cooperatives, microfinance institutions, middlemen, and others. Of 263 total respondents, 20.9% take a loan from a bank. They choose to get a loan from a bank because they can get the money fast. Besides, people’s business credit has a relatively low-interest rate. Cooperative is another financing source they choose, chosen by a small proportion of the respondents (5.3%) due to the low-interest rate. Microfinance institution is the third source the respondents choose. A small proportion of the respondents (6.8%) take a loan from a microfinance institution. Another alternative credit source after the bank is from Pura (the temple) or religious institution and individual, chosen by 7.6% of the respondents. Respondents choose this credit source because it does not have an interest rate, for example, if they borrow from a neighbour. A minority of the respondents choose middlemen as a source of credit (0.8%), the smallest compared to other sources because it is not easy to access. The rest of the respondents (58.6%) do not take a loan because they are afraid to have debt, fear of riba (usury), and fear of being unable to pay. Some of them have their capital, saved from their previous harvest, to finance the next planting season. This research found that the percentage of farmers who take a loan is lower than those without. This percentage can be increased to boost their productivity. Previous research showed that non-financial policies, like data recording and land ownership confirmation, have improved farmers’ financing access to formal credit [83].

4.2 Result of multicollinearity test

A multicollinearity test was done to determine whether independent variables influence one another. If there is a correlation between independent variables, the correlation between dependent and independent variables is questionable. The results of the multicollinearity test using SPSS 26 are presented in Table 3.

Results of the multicollinearity test

| Model | Sig. | Collinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||

| (Constant) | 0.000 | ||

| Age | 0.363 | 0.589 | 1.698 |

| Education | 0.232 | 0.985 | 1.015 |

| Income | 0.203 | 0.256 | 3.908 |

| Organisation Membership | 0.447 | 0.975 | 1.026 |

| Working experience | 0.287 | 0.591 | 1.692 |

| Loan experience | 0.000 | 0.933 | 1.072 |

| Land size | 0.014 | 0.247 | 4.054 |

Table 3 presents the result of the multicollinearity test using SPSS 26. The VIF value indicates that the data have no multicollinearity. If there is no variable in the data with a VIF value bigger than 10, the data do not have multicollinearity [1,74] and [73]. So, the data distribute normally, and there is no correlation between X 1, X 2, …. X n . Previous research on the factors influencing Credit at National Public Private Bank (BUSN) Foreign exchange also conducted a multicollinearity test and found that the data did not have multicollinearity [84].

4.3 Factors that determine Cassava Farmers’ access and credit source in Lampung

The multinomial logit model (MNL) is used to model the relationship between the dependent variables with multi choices and a group of Independent variables [43]. Mathematically, in multinomial logit, if there are m categories of dependent variables, one is assumed as the referential category. It needs a calculation of equation m-1 for every relative category toward the referential category to describe the influence of independent variables on the dependent variable. Many previous studies used Multinomial Logit Analysis to determine the influence of independent variables towards dependent variables with more than one category [50,51,65,79,82,85,86,87,88,89]. The results of the MNL test using SPSS 26 are presented in Table 4.

Model fitting information

| Model | Model fitting criteria | Likelihood ratio tests | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2Log Likelihood | Chi-square | df | Sig. | |

| Intercept Only | 638.216 | |||

| Final | 197.966 | 440.250 | 75 | 0.0001 |

Table 4 shows a declining value of −2Log Likelihood from 638.216 to 197.996 (p = 0.001), indicating that independent variables can better predict farmers’ decisions. The Goodness Fit of the model is presented in Table 5.

Goodness of Fit

| Chi-square | Df | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | 386.707 | 1,235 | 1.000 |

| Deviance | 197.966 | 1,235 | 1.000 |

The goodness of fit is used to examine the suitability of the predicted logistic regression. It means that the model consists of variables (the main effect and the interaction) that are supposed to be in the model, and the variables have the right function [90]. The goodness of fit test is necessary to determine whether the model is appropriate. The goodness of fit test results in Table 4 show that the Multinomial Logistic Regression Model model is in line with the observation data, and there is a real difference between the observation result and the predicted model (p = 1.000). Furthermore, the results of the determination coefficient test (R 2) can be seen in Table 6.

Pseudo R square

| Cox and Snell | 0.812 |

| Nagelkerke | 0.891 |

| McFadden | 0.690 |

The model parameter test examines the role of independent variables in the model [90]. The determination coefficient (R 2) refers to the ability of independent variables to describe their dependent variables. The determination coefficient examines how much independent variables influence the value of the dependent variable. A model is considered good if its Nagelkerke coefficient is greater than 70%, meaning that the independent variables made for the model influence 70% of the dependent variable. Table 5 shows three models: Mc Fadden, Coxan and Snell, and Nagelkerke R-Square. Among the three models, the value of Nagelkerke R-Square is the biggest (0.891), so the value of Nagelkerke R-Square was used. The independent variables (age, income, business experience, land size, education, membership, and credit experience) account for 89.1% of the dependent variable (types of credit). The remaining (10.9%) is explained by variables not included in the model. This finding aligns with those of Chandio et al. and Santoso and Gan [57,91] reporting that creditors’ age and family income are the main determining factors influencing credit access. Simultaneously, another study found a simultaneous influence from land size, business experience, and education of the respondents [88]. Cooperative membership also has a positive influence [79]. The results of the partial test are presented in Table 7.

Likelihood ratio test

| Effect | Model fitting criteria | Likelihood ratio tests | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2Log likelihood of reduced model | Chi-square | Df | Sig. | |

| Intercept | 197.966 | 0.000 | 0 | . |

| Age | 229.767*** | 31.801 | 5 | 0.0001 |

| Income | 216.556*** | 18.589 | 5 | 0.002 |

| Agribusiness experience | 212.831** | 14.864 | 5 | 0.011 |

| Land size | 240.091*** | 42.125 | 5 | 0.0001 |

| Education | 273.348*** | 75.381 | 25 | 0.0001 |

| Organisation Membership | 218.090 | 20.124 | 25 | 0.740 |

| Credit Experience | 544.011*** | 346.045 | 5 | 0.0001 |

***Significant at 1%, **Significant at 5%.

The model parameter is tested to examine the role of independent variables towards the model [90]. This statistical testing is the ratio of the probability of parameter value, which is hypothesised with maximum data probability [92]. Table 7 shows that age, income, business experience, land size, education, and credit experience significantly influence the types of credit, while membership does not. It is in line with previous research [29,57,51,93,94], revealing that age influences farmers’ access to loans. The study results show that age has a positive relationship with access to credit, meaning that if age increases, access to credit also increases. This can happen because as the age of the head of the household increases, the head of the household becomes more experienced and aware of access to and use of credit income also significantly influences access to loans [52,57,65,93]. Income has a positive effect on access to farmer credit, meaning that if farmers have a high income, access to credit for farmers is also higher; this is because when farmers as debtors have a high income, creditors who will provide loans will also have more trust. Agribusiness experience also partially influences loans; it aligns with the studies by Chinwuba et al. and Wulandari et al. [43,44], revealing that business experience influences access to external financing sources. Farming experience with farmers’ access to credit has a positive relationship, meaning that when farming experience increases, access to credit also increases; this can happen because experienced farmers have dealt with banks several times to access loans, so they have a better understanding of the terms, provisions, and procedures [95]. Land size influences the types of loans, similar to the finding of previous research [44]. Land size is also important when deciding on a credit scheme [65]. Education also influences cassava farmers in choosing the types of loans [43,91]. Higher education will increase farmers’ technical knowledge. In addition, a good understanding of markets and credit facilities will also increase. Saqib et al. [95] showed that farmers with middle and high school educational levels have greater access to credit than their counterparts with lower education levels. Next, this study found that membership does not significantly influence cassava farmers; it contrasts with previous research [96], showing that cooperative membership individually has a negative correlation with credit access. Lastly, credit experience partially has a significant influence on the types of loans, which is in line with a study stating that credit experience influences access to the external financing source [44]. Increasing access to smallholder agricultural credit can be done through access to information and extension services [97].

4.4 Determining factors of cassava farmers’ credit participation

After identifying the factors determining access and credit sources of cassava farmers in Lampung using the multinomial logit method, the influence of dependent variables towards independent variables was estimated through marginal effect using STATA. Marginal effect measures the changes expected in the probability of certain choices made in relation to the change in describing variable [98]. The Independent variables influence dependent variables X1 (age), X2 (education), X3 (income), X4 (membership), X5 (business experience), X6 (credit experience), and X7 (land size). Dependent variables are classified into five categories: formal bank, and cooperative. Microfinance institutions, middlemen, and other sources. Table 8 shows that age, business experience, and land size are the determining factors in accessing financial credit through microfinance institutions, formal banks, and other sources.

Marginal effect of independent variables from multinomial logit model

| Variable | Formal bank | Cooperative | Microfinance institution | Middleman | Others | No credit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | ME | Coefficient | ME | Coefficient | ME | Coefficient | ME | Coefficient | ME | Coefficient | ME | |

| X1 | −0.0036021 | 0.0011912 | −0.0040465 | −0.0007168 | 0.001897 | 0.0047133*** | −0.0015897 | 0.0000594 | −0.009593 | −0.0052471 | −6.39 × 10−7 | −1.51 × 10−11 |

| X2 | −0.0544921 | −0.024208 | −0.0105273 | 0.0095606 | −0.005959 | 0.0128277 | −0.0132201 | −0.0031785 | −0.0189921 | 0.0049983 | −4.98 × 10−6 | −1.99 × 10−10 |

| X3 | −4.04 × 10−9 | −1.79 × 10−9 | −8.11 × 10−10 | 4.80 × 10−10 | −1.41 × 10−9 | 8.10 × 10−10 | −4.77 × 10−10 | 1.51 × 10−10 | −1.25 × 10−9 | 3.53 × 10−10 | −2.41 × 10−13 | −8.49 × 10−19 |

| X4 | −0.0546962 | −0.0030897 | −0.0075881 | 0.0247151 | −0.0538696 | −0.0157139 | −0.0164826 | 0.003188 | −0.0511241 | −0.0090994 | −7.28 × 10−6 | 2.90 × 10−11 |

| X5 | −0.0075123 | −0.0021174 | −0.0033763 | 0.0004894 | −0.007079 | −0.0042207*** | −0.0008231 | 0.001594 | −0.0004076 | 0.0042547* | −9.23 × 10−7 | −6.33 × 10−12 |

| X6 | −7.149.607 | 0.0106249 | −4.938.652 | −0.0170227 | −3.291.656 | 0.0256947 | −8.923.725 | −0.0106744 | −5.992.053 | −0.0086224 | −0.0001912 | −6.65 × 10−8 |

| X7 | 0.0483256 | 0.1149537*** | −0.0259371 | 0.0071997 | −0.2073647 | −0.1201009*** | −0.0198405 | −0.0018879 | −0.0452397 | −0.0001646 | −9.77 × 10−6 | 8.09 × 10−10 |

***Significant at 1%, *Significant at 10%.

Age is a determining factor for cassava farmers in accessing and choosing microfinance institutions. Table 8 shows that age will improve the choice of access in a microfinance institution. The Marginal effect value is 0.0047. It means if the age is one year older, it will increase the choice of credit access to microfinance institutions by 0.47%. This research is in line with [93,99,100], whose research result showed that age has a significant influence on farmers’ credit access choices. As farmers get older, they have more experience in agribusiness and know better how to overcome problems, including the problem of agribusiness financing. Hence, they will be better aware of credit access and credit effect.

Business experience negatively influences credit access chosen by the farmers (with a significance level of 1 and 10%). The influence of business experience towards access choice of microfinance institution is 0.42% and negative. If business experience is one year longer, it will reduce cassava farmers’ credit access to microfinance institutions. With one year of business experience extension, the probability of access to other sources will lower by 0.42%. The result of this research is in line with that of Ullah et al. [52], showing that agribusiness experience negatively influences their access to agribusiness credit. Land size becomes the next determining factor for farmers’ access to credit sources. Land size positively influences farmers’ access to formal banks, with a marginal effect of 0.1149. If the land is one hectare larger, it will increase their credit access to formal banks by 11.49. This finding aligns with the study by Tiku et al. [51] reporting that land size most influences the farmers in getting a bank loan. Land size negatively influences farmers’ access to microfinance institutions, with a marginal effect of 0.1201. If the land is one hectare larger, the access to microfinance institutions will lower by 12.01%. It agrees with the study by Dang et al. [65], whose marginal effect shows land size negatively influences informal credit absorption. Larger farming areas need more funding, and informal financial institutions cannot provide it, so the farmers have to choose other options, as revealed in a previous study [101]. Informal finance institutions cannot provide big loans; thus, farmers’ interest in non-formal credit access is reduced when they need a big loan, increasing their access to formal credit.

It is also related to collateral, which is part of the 5 C principles (Character, Capacity, Capital, Collateral, and Condition) in approving credit. Previous research [102] revealed that practically 5 C principles are only applied at the point of having big collateral. Collateral is a common finance instrument adopted by public banks to control credit from the failure of payment by the clients [103]. In this research, the land or farming area functions as collateral in line with Agrarian Law, which stipulates that Land ownership can be made as collateral of debt with the charge. The creditor has a strong position related to the collateral [104]. Access to formal credit probably will be better by having collateral [63,105]. On the other hand, collateral is the main difficulty in facilitating the provision of informal credit [56,106]. Collateral offered by informal credit is relatively higher. Microbusinesses consider more credit procedures and collateral than interest rates [107]. On the other hand, the interest rate of formal financing sources is lower. This is the plus point of formal financing and the minus of informal one. However, the administrative procedure of formal financing is considered complicated.

5 Conclusions and suggestions

Agricultural business is essential in most countries, including developing countries like Indonesia. Sustainable agribusiness has a great role in supporting a country’s development. However, smallholder farmers often have limited access to loans, hindering them from expanding their business and productivity. This research was conducted in Central Lampung Regency, Indonesia investigating the factors affecting farmers’ access to financing sources by interviewing 263 cassava farmers. The results reveal that simultaneously, the independent variables (age, income, business experience, land area, education, membership, and loan experience) can affect the dependent variable (type of loan). Partially, age, income, business experience, education, land size, and loan experience significantly affect the dependent variable (type of loan). On the other hand, organisation membership has no significant effect on the type of loan. In short, the main factors influencing farmers in selecting loan types are age, agribusiness experience, and land size.

In addition, the small proportion of farmers with credit access proves that the farmers have low interest in taking a loan. Therefore, easy and informative access to loans to farmers and government regulations to facilitate smallholders’ access to agricultural credit at affordable interest rates are necessary. In addition, it is also necessary to conduct counselling concerning the procedures and advantages of taking loans at the related institutions so that farmers can be well-informed and have no hesitation in taking loans. Training on optimising productivity through good financing for cassava farming also needs to be conducted to attract farmers to take loans. Further research should analyse the impact of loans for cassava farmers in Lampung Province, Indonesia. In addition, we also suggest researching the factors affecting credit from the demand and supply sides.

-

Funding information: This work has been financed with sources of the Ministry of Education, Research and Technology (Kementerian Pendidikan, Riset dan Teknologi).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Ameh M, Lee SH. Determinants of loan acquisition and utilisation among smallholder rice producers in Lagos state, Nigeria. Sustainability. 25 March 2022;14(3900):1–15.10.3390/su14073900Search in Google Scholar

[2] Akinbode SO. Access to credit: Implication for sustainable rice production in Nigeria. J Sustain Dev. 2013;15:13–30.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Attah AW. Food security in Nigeria: The role of peasant farmers in Nigeria. Int J Ethiopia. 2012;6:173–90.10.4314/afrrev.v6i4.12Search in Google Scholar

[4] Nwagboso, Christopher I. Rural development as strategy for food security and global peace in the 21st century mediterranean. J Soc. 2012;3:337–90.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ijioma J, Osondu C. Agricultural credit sources and determinants of credit acquisition by farmers in idemili local government area of Anambra state, Nigeria. J Agric Sci Technol. 2015;5:34–43.10.17265/2161-6264/2015.01B.004Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mtunguja MK, Beckles DM, Laswai HS, Ndunguru JC, Sinha NJ. Opportunities to commercialise cassava production for poverty alleviation and improved food security in Tanzania. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2019;19(1):13928–46.10.18697/ajfand.84.BLFB1037Search in Google Scholar

[7] Musyafak A, Susanti AA, Supriyatna A, Suryani R, Suyati, Tarmat. Outlook Ubi Kayu Komoditas Pertanian Subsektor Tanaman Pangan. Jakarta: Pusat Data dan Sistem Informasi Pertanian Sekretariat Jendral Kementrian Pertanian; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Nassar N, Ortiz R. Breeding cassava to feed the poor. Sci Am. 2010;302(5):78–85.10.1038/scientificamerican0510-78Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Li S, Cui Y, Zhou Y, Luo Z, Liu J, Zhao M. The industrial applications of cassava: current status, opportunities and prospects. J Sci Food Agric. 2017;97(8):2282–90.10.1002/jsfa.8287Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Alene AD, Abdoulaye T, Rusike J, Labarta R, Creamer B, Del Río M, et al. Identifying crop research priorities based on potential economic and poverty reduction impacts: the case of cassava in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):1–9.10.1371/journal.pone.0201803Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Arief RW, Asnawi R, Utomo JS. Pengembangan pemanfaatan ubikayu di provinsi Lampung melalui pengolahan tepung ubikayu dan tepung ubikayu modifikasi. Bul Palawija. 2012;91(24):82–91.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Omolara GM, Adunni AA, Omotayo AO. Cost and return analysis of cassava flour (Lafun) production among the omen of Osun state, Nigeria. Sci Res. 2017;5(5):55–60.10.11648/j.sr.20170505.12Search in Google Scholar

[13] Njoku DN, Mbah EU. Assessment of yield components of some cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) genotypes using multivariate analysis such as path coefficients. Open Agric. 2020;5(1):516–28.10.1515/opag-2020-0051Search in Google Scholar

[14] Spencer DSC, Ezedinma C. Cassava cultivation in sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge: Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing; 2017. p. 123–48.10.19103/AS.2016.0014.06Search in Google Scholar

[15] Tonukari NJ, Tonukari NJ, Ezedom T, Enuma CC, Sakpa SO, Avwioroko OJ, et al. White gold: Cassava as an industrial base. J Plant Sci. 2015;6:972–9.10.4236/ajps.2015.67103Search in Google Scholar

[16] Elisabeth DAA, Utomo JS, Byju G, Ginting E. Cassava flour production by small scale processors, its quality and economic feasibility. Food Sci Technol Camp. 2022;42:1–9.10.1590/fst.41522Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mbanjo EG, Rabbi IY, Ferguson ME, Kayondo SI, Eng NH, Tripathi L, et al. Technological innovations for improving cassava production in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front Genet. 2021;11:1–21.10.3389/fgene.2020.623736Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Donkor E, Onakuse S, Bogue J, Carmenado IDLR. The impact of the presidential cassava initiative on cassava productivity in Nigeria: Implication for sustainable food supply and food security. Cogent Food Agric. 2017;3:1–14.10.1080/23311932.2017.1368857Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ojijo N, Franzel S, Simtowe F, Madakadze R, Nkwake A, Moleko L. The role for agricultural Research Systems, Advisory services and capacity developement and knowledge transfer. In Africa agriculture status report 2016: Progress towards agricultural transformation (AGRA). Uttar Pradesh: AGRA: s.n.; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Kementan RI. Basis data statistik pertanian. Jakarta: Pusat Data dan Sistem Informasi Kementerian Pertanian; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Acheampong P, Owusu V, Nurah G. How does farmer preference matter in crop variety adoption? The case of improved cassava varieties’ adoption in Ghana. Open Agriculture. 2018;3(1):466–77.10.1515/opag-2018-0052Search in Google Scholar

[22] Ngo Q, Doan P, Vo L, Tran H. The influence of green finance on economic growth: A COVID-19 pandemic effects on Vietnam Economy. Cogent Bus Manag. 2021a;8(1):1–19.10.1080/23311975.2021.2003008Search in Google Scholar

[23] Ngo Q, Tran H, Tran H. The impact of green finance and Covid-19 on economic development: Capital formation and educational expenditure of ASEAN economies. China Finance Rev Int. 2021b;12(2):261–79.10.1108/CFRI-05-2021-0087Search in Google Scholar

[24] OECD. Towards green growth in Southeast Asia solutions for policy. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Han MS, Yua Q, Fahad S, Ma T. Dynamic evaluation of green development level of ASEAN region and its spatio-temporal patterns. J Clean Prod. 2022;362:132402.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132402Search in Google Scholar

[26] Tasri E. Analysis of green economic growth concept in the ASEAN countries. J Manag Appl Sci. 2016;2(10):13–7.10.5937/ejae13-11311Search in Google Scholar

[27] The World Bank, 2022. Agriculture finance & agriculture insurance. [Online] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialsector/brief/agriculture-finance [Diakses 15 maret 2023].Search in Google Scholar

[28] Fahad S, Su F, Wei K. Quantifying households’ vulnerability, regional environmental indicators, and climate change mitigation by using a combination of vulnerability frameworks. Land Degrad & Devlopment. 2023;34(3):859–72.10.1002/ldr.4501Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ben-Chendo GN, Oshaji I, Iweanya G. Determinants Of credit sources utilised by small scale arable crop farmers in Imo state, Nigeria. Adv Soc Sci Res J. 2018;5(6):232–44.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Fahad S, Nguyen-Thi-Lan H, Nguyen-Manh D, Tran-Duc H, To-The N. Analysing the status of multidimensional poverty of rural households by using sustainable livelihood framework: Policy implications for economic growth. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30:16106–19.10.1007/s11356-022-23143-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] FAO, 2020. Part one: Smallholders and their characteristics. [Online]. http://www.fao.org[Diakses 2 October 2020].Search in Google Scholar

[32] Even B, Donovan J. Value chain development in Vietnam: a look at approaches used and options for improved impact. Enterp Dev Microfinance. 2017;28(1):28–43.10.3362/1755-1986.16-00034Search in Google Scholar

[33] Vighneswara SDM. Analysing the agricultural value chain financing: approaches and tools in India. Agric Financ Rev. 2016;76(2):1–28.10.1108/AFR-11-2015-0051Search in Google Scholar

[34] Bank Indonesia. Skema pembiayaan dengan pendekatan konsep rantai nilai (value chain financing). Jakarta: Bank Indonesia; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Sitinjak PH, Ruzikna. Analisis faktor-faktor yang mempengaruhi realisasi kredit mikro pada bank CIMB Niaga Unit Subrantas. J Online Mahasiswa (JOM) Bidang Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik. 2014;1(1):1–8.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Lubis AM, Rachmina D. Faktor-Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Realisasi dan Pengembalian Kredit Usaha Rakyat. Forum Agribisnis. 2011;1(2):112–31.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Okonjo-Iwela N, Keller JM. Shine a light on the gaps. [Online]. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/ft/shine-light-gaps. [22 July 2023].Search in Google Scholar

[38] WOCCU. Integrated financing for value chains-credit unions fills the agricultural; s.n. s.l. 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Mudassir A, Saleh D, Nasrulhaq N. Efektivitas Penyaluran KUR (Kredit Usaha Rakyat) Pada PT. Bank Rakyat Indonesia (Persero) Tbk. Unit Tanah Lemo Kecamatan Bonto Bahari Kabupaten Bulukumba. Kajian Ilmiah Mahasiswa Administrasi Publik. 2020;1(2):381–93.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Appiah-Twumasi M, Donkoh SA, Ansah IGK. Farmer Innovations in financing smallholder maise production in Northern Ghana. Agric Financ Rev. 2020;80(3):421–36.10.1108/AFR-05-2019-0059Search in Google Scholar

[41] Gessesse M. Value chain financing instruments in Sidama coffee value chain, Ethiopia. Eur J Bus Manag. 2017;9(1):10–9.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Vitor DA. Theoretical and conceptual framework of access to financial services by farmers in emerging economies: implication for empirical analysis. Acta Univ Sapientiae Econ Bus. 2018;6:43–59.10.1515/auseb-2018-0003Search in Google Scholar

[43] Chinwuba IP, Davina AO, Lucky AA. Analysis of agricultural value chain finance in smallholder palm oil processing in Delta State. Niger Ind Eng Lett. 2016;6(7):1–7.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Wulandari E, Meuwissen MPM, Karmana MH, Lansink AGJMO. Access to finance from different finance provider types: Farmer knowledge of the requirements. PLoS ONE. 2017;6(9):1–15.10.1371/journal.pone.0179285Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Kadarsan HW. Keuangan pertanian dan pembiayaan perusahaan agribisnis. Jakarta: Gramedia; 1992.Search in Google Scholar

[46] World Bank. Vietnam agriculture finance diagnostic report: Financial inclusion support framework - Vietnam country support program. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Miller C, Jones L. Agricultural value chain finance: Tools and Lessons. Warwickshire, UK: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Practical Action Publishing; 2010.10.3362/9781780440514.001Search in Google Scholar

[48] Salmiah, Sebayang T, Khaliqi M, Muda I. Farmer preference to access agricultural credit in Indonesia. Jr Sci Res. 2019;5(1):16–23.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Gunawan E, Ilham N, Syukur M, Pasaribu SM, Suhartini SH. Farmers’ perceptions and issue of Kredit Usaha Rakyat in Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 892; 2021. p. 1–7.10.1088/1755-1315/892/1/012017Search in Google Scholar

[50] Dung LT. A multinomial logit model analysis of farmers’ participation in agricultural cooperatives: Evidence from Vietnam. Appl Econ J. 2020;27(1):1–22.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Tiku NE, Saleh P, Waziri-Ugwu PR, Ibrahim U, Nafisat N. Multinomial logit estimation of income sources by watermelon farmers in Northeastern Nigeria. Int J Environ Agric Biotechnol. 2018;3(4):1441–9.10.22161/ijeab/3.4.40Search in Google Scholar

[52] Ullah A, Mahmood N, Zeb A, Kachele H. Factors determining farmers’ access to and sources of credit: Evidence from the rain-fed zone of Pakistan. Agriculture. 2020;10:586.10.3390/agriculture10120586Search in Google Scholar

[53] Awotide B, Abdoulaye T, Alene A, Manyong V. Impact of access to credit on agricultural productivity: Evidence from smallholder cassava farmers in Nigeria. IAAE International Conference Of Agricultural Economic; 2015. Issue 1008-2016-80242.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Bokpin G, Ackah C, Kunawotor M. Financial access and firm productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Afr Bus. 2018;19(2):210–26.10.1080/15228916.2018.1392837Search in Google Scholar

[55] Missiame A, Nyikal RA, Irung P. What is the impact of rural bank credit access on the technical efficiency of smallholder cassava farmers in Ghana? An endogenous switching regression analysis. Heliyon. 2021;7:e07102.10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07102Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Akintunde O, Olanrewaju K, Jimoh L, Bamiwuye OA. Determinants Of cassava farmers credit accessibility in irewole local government area of Osun state, Nigeria. Nigerian J Agric Food Environ. 2021;17(3):8–18.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Santoso DB, Gan C. Microcredit accessibility in rural households: Evidence from Indonesia. Econ Financ Indones. 2019;65(1):67–88.10.47291/efi.v65i1.635Search in Google Scholar

[58] Gumanti TA, Moeljadi, Utami ES. Metode penelitian keuangan. Pertama penyunt. Jakarta: Mitra Wacana Media; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[59] BPS Provinsi Lampung. Angka Tetap Tahun 2020 Produksi Ubi Kayu. Bandar Lampung: BPS Provinsi Lampung; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Zulkarnain Z, Zakaria WA, Haryono D, Murniati K. Daya saing komoditas ubi kayu dengan internalisasi biaya transaksi di Kabupaten Lampung Tengah, Lampung, Indonesia. Agro Bali: Agric J. 2021;4(2):230–45.10.37637/ab.v4i2.712Search in Google Scholar

[61] BPS Kabupaten Lampung Tengah. Kabupaten Lampung Tengah Dalam Angka. Gunung Sugih: BPS Kabupaten Lampung Tengah; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Sugiyono. Metode penelitian kuantitatif, kualitatif, dan R&D. Yogyakarta: Alfabeta; 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Barslund M, Tarp F. Formal and informal rural credit in four provinces of Vietnam. J Dev Stud. 2008;44:485–503.10.1080/00220380801980798Search in Google Scholar

[64] Isaga N. Access to bank credit by smallholder farmers in Tanzania: A case study. Afr Focus. 2018;31(1):241–56.10.1163/2031356X-03101013Search in Google Scholar

[65] Dang HD, Dam AHT, Pham TT, Nguyen TMT. Determinants of credit demand of farmers in Lam Dong, Vietnam A comparison of machine learning and multinomial logit. Agric Finance Rev. 2020;80(2):255–74.10.1108/AFR-06-2019-0061Search in Google Scholar

[66] Chiu LJV, Khantachavana SV, Turvey CG. Risk rationing and the demand for agricultural credit: A comparative investigation of Mexico and China. Agric Finance Rev. 2014;74(2):248–70.10.1108/AFR-05-2014-0011Search in Google Scholar

[67] Debesai M. Factors affecting vulnerability level of farming households to climate change in developing countries: Evidence from Eritrea. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; 2020. p. 1001.10.1088/1757-899X/1001/1/012093Search in Google Scholar

[68] Kong R, Turvey C, Xu X, Liu F. Borrower attitudes, lender attitudes and agricultural lending in rural China. Int J Bank Mark. 2014;32(2):104–29.10.1108/IJBM-08-2013-0087Search in Google Scholar

[69] Ojonta OI, Ogbuabor JE. Access to Credit and Physical Capital Stock; a Study of Non-Farm Household Enterprises in Nigeria. Bull Monetary Econ Bank. 2021;24(4):632–40.10.21098/bemp.v24i4.1515Search in Google Scholar

[70] Hossain MS, Alam GM, Fahad S, Sarker T, Moniruzzaman M, Rabbany MG. Smallholder farmers’ willingness to pay for flood insurance as climate change adaptation strategy in northern Bangladesh. J Clean Prod. 2022;338:1–11.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130584Search in Google Scholar

[71] Greene W. Econometric analysis. 8th edn penyunt. New York: Pearson; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Suharjo B. Analisis regresi terapan dengan SPSS. Yogyakarta: Graha Ilmu; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Wasiaturrahma D, Rohmawati H. Multicollinearity in tourism demand model: Evidence from Indonesia. Econ Dev Anal J. 2021;10(1):54–69.10.15294/edaj.v10i1.42078Search in Google Scholar

[74] Maddala GS. Introduction to econometrics. 2nd edn penyunt. New York: Macmillan Publisihing Company; 1992.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Garson GD. Logistic regression: Binary & multinomial. USA: Statistical Publishing Associates; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. England: Press Cambridge; 2002.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Widarjono A. Ekonometrika pengantar dan aplikasinya. Edisi Ketiga penyunt. Yogyakarta: Ekonoisia; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Lastiati A, Rachmawati N. Stata for beginners, modeul pelatihan. Jakarta: Universitas Trilogi; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Gebru GW, Ichoku HE, Phil-Eze PO. Determinants of smallholder farmers’ adoption of adaptation strategies to climate change in Eastern Tigray National Regional State of Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2020;6:1–9.10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04356Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[80] Siswadi B, Rosyidah A. Factors affecting the farmer’s response to the development of soybean farming in East Java Indonesia. Int J Environ Agric Biotechnol. 2017;2(6):3045–9.10.22161/ijeab/2.6.34Search in Google Scholar

[81] Ebewore SO, Isiorhovaja RA. Knowledge status and disease control practices of cassava farmers in Delta state, Nigeria: Implications for extension delivery. Open Agric. 2019;4(1):173–86.10.1515/opag-2019-0017Search in Google Scholar

[82] Demeke L, Haji J. Econometric analysis of factors market participation of smallholder farming in Central Ethiopia. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. 2017;77024.Search in Google Scholar

[83] Li X, Huo X. Impacts of land market policies on formal credit accessibility and agricultural net income: Evidence from China’s apple growers. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;173(9):1–10.10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121132Search in Google Scholar

[84] Rai IAA, Purnawati NT. Faktor-faktor yang mempengaruhi kredit pada bank umum swasta nasional (BUSN) devisa. E-J Manaj UNUD. 2017;6(11):5941–69.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Islam DI, Rahman A, Sarker MS, Luo J, Liang H. Factors affecting farmers’ willingness to adopt crop insurance to manage disaster risk: evidence from Bangladesh. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev. 2021;20(31):463–79.10.22434/IFAMR2019.0190Search in Google Scholar

[86] Marie M, Yirga F, Haile M, Tquabo F. Farmers’ choices and factors affecting adoption of climate change adaptation strategies: Evidence from nortwestern ethiopia. Heliyon. 2020;6:e03867.10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03867Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[87] Ojo MA, Nmadu JN, Tanko L, Olaleye RS. Multinomial logit analysis of factors affecting the choice of enterprise among smallholder yam and cassava farmers in Niger state, Nigeria. J Agric Sci. 2013;4(1):7–12.10.1080/09766898.2013.11884695Search in Google Scholar

[88] Priyadi U. The role of institutional innovation in madukismo sugar industry toward the sugarcane farming production in the Province Jogjakarta. Econ J Emerg Mark. 2008;13(2):1–24.Search in Google Scholar

[89] Sadiq MS, Singh IP, Ahmad MM, Garba A. Factors determining choice of conventional labour among yam producers in Benue state of Nigeria. Indones J Agric Res. 2021;4(1):1–12.10.32734/injar.v4i1.5138Search in Google Scholar

[90] Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Saturdivant RX. Applied Logistic regression. Wiley Series In Probability and Statistics. 3rd edn penyunt. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2013.10.1002/9781118548387Search in Google Scholar

[91] Chandio AA, Jiang Y, Rehman A, Twumasi MA, Pathan AG, Mohsin M. Determinants of demand for credit by smallholder farmers’: A farm level analysis based on survey in Sindh, Pakistan. J Asian Bus Econ Stud. 2021;28(3):225–40.10.1108/JABES-01-2020-0004Search in Google Scholar

[92] Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2015.10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7Search in Google Scholar

[93] Kiros S, Meshesha GB. Factors affecting farmers’ access to formal financial credit in Basona Worana District, North Showa Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Cogent Econ Finance. 2022;10:1–22.10.1080/23322039.2022.2035043Search in Google Scholar

[94] Mhlanga D, Hassan A. Financial participation among smallholder - farmers in Zimbabwe: What are the driving factors? Acad J Interdiscip Stud. 2022;11(4):300–10.10.36941/ajis-2022-0117Search in Google Scholar

[95] Saqib SE, Kuwornu JK, Panezia S, Ali U. Factors determining subsistence farmers’ access to agricultural credit in flood-prone areas of Pakistan. Kasetsart J Soc Sci. 2018;39:262–8.10.1016/j.kjss.2017.06.001Search in Google Scholar

[96] Ukwuaba IC, Owutuamor ZB, Ogbu CC. Assessment of agricultural credit sources and accessibility in Nigeria. Rev Agric Appl Econ. 2020;18(2):3–11.10.15414/raae.2020.23.02.03-11Search in Google Scholar

[97] Balana BB, Oyeyemi MA. Agricultural credit constraints in smallholder farming in developing countries: Evidence from Nigeria. World Dev Sustainability. 2022;1:100012.10.1016/j.wds.2022.100012Search in Google Scholar

[98] Greene W. Econometric analysis. 7th edn penyunt. NJ: Person Prentice; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[99] Baiyegunhi LJS, Fraser GCG. Smallholder farmers’ access to credit in the amathole district municipality, Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J Agric Rural Dev Trop Subtrop. 2014;115(2):79–89.Search in Google Scholar

[100] Samuel S. Determinants of access to formal credit in rural areas of Ethiopia: Case study of smallholder households in Boloso Bombbe district, Wolaita zone, Ethiopia. J Econ. 2020;9(2):40–8.10.11648/j.eco.20200902.13Search in Google Scholar

[101] Pratiwi DE, Ambayoen MA, Hardana AE. Studi pembiayaan mikro petani dalam pengambilan keputusan untuk kredit formal dan kredit nonformal. Habitat. 2019;30(1):35–43.10.21776/ub.habitat.2019.030.1.5Search in Google Scholar

[102] Lailiyah A. Urgensi Analisis 5C pada Pemberian Kredit Perbankan untuk Meminimalisir Resiko. Yuridika. 2014;29(2):217–32.10.20473/ydk.v29i2.368Search in Google Scholar

[103] Lemessa A, Gemechu A. Analysis of factors affecting smallholder farmers’ access to formal credit in jibat district, West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. Int J Afr Asian Stud. 2016;25:43–53.Search in Google Scholar

[104] Putra BSH. Kedudukan sertifikat hak atas tanah sebagai jaminan kebendaan berdasarkan undang-undang hak tanggungan atas tanah beserta benda-benda yang berkaitan dengan tanah. J Priv Law. 2020;8(1):57–62.10.20961/privat.v8i1.40367Search in Google Scholar

[105] Pham TTT, Lensink R. Lending policies of informal, formal and semiformal lenders: Evidence from Vietnam. Econ Transit. 2007;15(2):181–209.10.1111/j.1468-0351.2007.00283.xSearch in Google Scholar

[106] Tang S, Guo S. Formal and informal credit markets and rural credit demand in China. Kyoto, 2017 4th International Conference on Industrial Economics System and Industrial Security Engineering (IEIS); 2017.10.1109/IEIS.2017.8078663Search in Google Scholar

[107] Setiawan AH. Analisis komparasi lembaga keuangan mikro (LKM) dalam penyaluran kredit mikro menurut preferensi usaha mikro di kota semarang. J Dinamika Ekonomi dan Bisnis. 2017;14(1):1–16.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on business risks and potato commercial model

- Effects of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.)–Mucuna pruriens intercropping pattern on the agronomic performances of potato and the soil physicochemical properties of the western highlands of Cameroon

- Machine learning-based prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid in horticultural products

- Revamping agricultural sector and its implications on output and employment generation: Evidence from Nigeria

- Does product certification matter? A review of mechanism to influence customer loyalty in the poultry feed industry

- Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia

- Lablab purpureus: Analysis of landraces cultivation and distribution, farming systems, and some climatic trends in production areas in Tanzania

- The effects of carrot (Daucus carota L.) waste juice on the performances of native chicken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate and its effects on plants and soil

- Factors influencing the role and performance of independent agricultural extension workers in supporting agricultural extension

- The fate of probiotic species applied in intensive grow-out ponds in rearing water and intestinal tracts of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei

- Yield stability and agronomic performances of provitamin A maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in South-East of DR Congo

- Diallel analysis of length and shape of rice using Hayman and Griffing method

- Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of various stem bark extracts of Hopea beccariana Burck potential as natural preservatives of coconut sap

- Correlation between descriptive and group type traits in the system of cow’s linear classification of Ukrainian Brown dairy breed

- Meta-analysis of the influence of the substitution of maize with cassava on performance indices of broiler chickens

- Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance (BLIS) produced by Enterococcus faecium MA115 and its potential use as a seafood biopreservative

- Meta-analysis of the benefits of dietary Saccharomyces cerevisiae intervention on milk yield and component characteristics in lactating small ruminants

- Growth promotion potential of Bacillus spp. isolates on two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) varieties in the West region of Cameroon

- Prioritizing IoT adoption strategies in millennial farming: An analytical network process approach

- Soil fertility and pomelo yield influenced by soil conservation practices

- Soil macrofauna under laying hens’ grazed fields in two different agroecosystems in Portugal

- Factors affecting household carbohydrate food consumption in Central Java: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Properties of paper coated with Prunus serotina (Ehrh.) extract formulation

- Fertiliser cost prediction in European Union farms: Machine-learning approaches through artificial neural networks

- Molecular and phenotypic markers for pyramiding multiple traits in rice

- Natural product nanofibers derived from Trichoderma hamatum K01 to control citrus anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

- Role of actors in promoting sustainable peatland management in Kubu Raya Regency, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Small-scale coffee farmers’ perception of climate-adapted attributes in participatory coffee breeding: A case study of Gayo Highland, Aceh, Indonesia

- Optimization of extraction using surface response methodology and quantification of cannabinoids in female inflorescences of marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) at three altitudinal floors of Peru

- Production factors, technical, and economic efficiency of soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) farming in Indonesia

- Economic performance of smallholder soya bean production in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Indonesian rice farmers’ perceptions of different sources of information and their effect on farmer capability

- Feed preference, body condition scoring, and growth performance of Dohne Merino ram fed varying levels of fossil shell flour

- Assessing the determinant factors of risk strategy adoption to mitigate various risks: An experience from smallholder rubber farmers in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

- Analysis of trade potential and factors influencing chili export in Indonesia

- Grade-C kenaf fiber (poor quality) as an alternative material for textile crafts

- Technical efficiency changes of rice farming in the favorable irrigated areas of Indonesia

- Palm oil cluster resilience to enhance indigenous welfare by innovative ability to address land conflicts: Evidence of disaster hierarchy

- Factors determining cassava farmers’ accessibility to loan sources: Evidence from Lampung, Indonesia

- Tailoring business models for small-medium food enterprises in Eastern Africa can drive the commercialization and utilization of vitamin A rich orange-fleshed sweet potato puree

- Revitalizing sub-optimal drylands: Exploring the role of biofertilizers

- Effects of salt stress on growth of Quercus ilex L. seedlings

- Design and fabrication of a fish feed mixing cum pelleting machine for small-medium scale aquaculture industry

- Indicators of swamp buffalo business sustainability using partial least squares structural equation modelling

- Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on early growth, root colonization, and chlorophyll content of North Maluku nutmeg cultivars

- How intergenerational farmers negotiate their identity in the era of Agriculture 4.0: A multiple-case study in Indonesia

- Responses of broiler chickens to incremental levels of water deprivation: Growth performance, carcass characteristics, and relative organ weights

- The improvement of horticultural villages sustainability in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Effect of short-term grazing exclusion on herbage species composition, dry matter productivity, and chemical composition of subtropical grasslands

- Analysis of beef market integration between consumer and producer regions in Indonesia

- Analysing the sustainability of swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) farming as a protein source and germplasm

- Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda

- Consumption profile of organic fruits and vegetables by a Portuguese consumer’s sample

- Phenotypic characterisation of indigenous chicken in the central zone of Tanzania

- Diversity and structure of bacterial communities in saline and non-saline rice fields in Cilacap Regency, Indonesia

- Isolation and screening of lactic acid bacteria producing anti-Edwardsiella from the gastrointestinal tract of wild catfish (Clarias gariepinus) for probiotic candidates

- Effects of land use and slope position on selected soil physicochemical properties in Tekorsh Sub-Watershed, East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia

- Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js

- Assessment of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed quality accessed through different seed sources in northwest Ethiopia

- Estimation of water consumption and productivity for wheat using remote sensing and SEBAL model: A case study from central clay plain Ecosystem in Sudan