Abstract

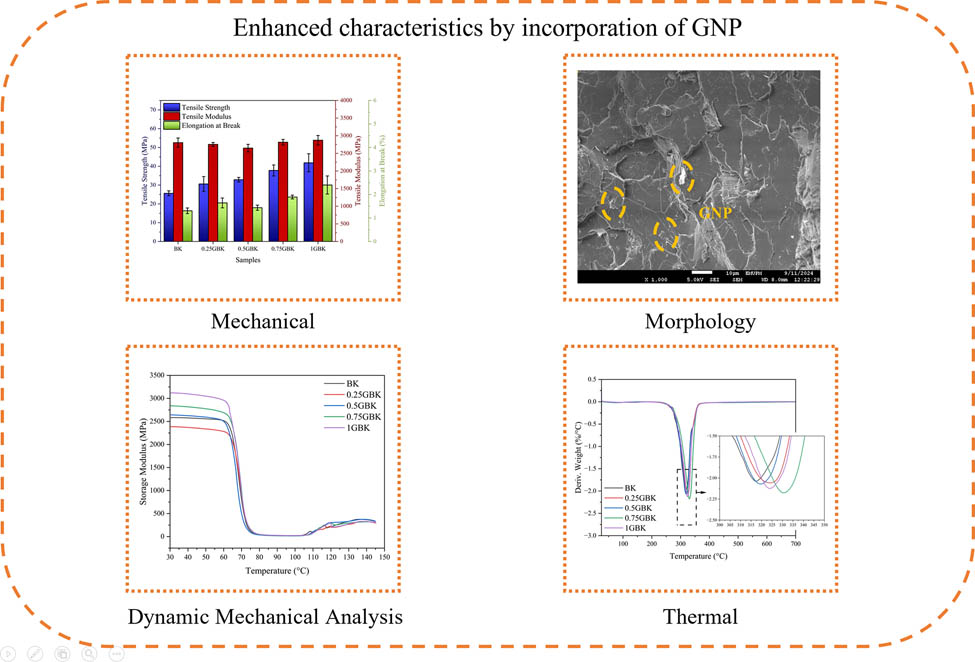

Many researchers have focused on developing eco-sustainable materials in response to the environmental concerns associated with the use of synthetic polymers, such as natural fiber-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) composites. In this study, short bamboo and kenaf fibers were employed to reinforce PLA composites. However, using these short natural fibers resulted in composites with inadequate characteristics. Therefore, this research examined the effects of incorporating a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelets into bamboo/kenaf fibers-reinforced PLA hybrid composites enhanced their poor characteristics. The research revealed that incorporating a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelets into composites enhanced their strength, with tensile strength of 41.86 MPa (1 GBK), flexural strength of 71.6712 MPa (0.25 GBK), impact strength of 3.63 kJ/m2 (1 GBK), and hardness of 86.80 HD. Furthermore, the morphology demonstrates that graphene nanoplatelets are successfully dispersed in composites. Also, the dynamic mechanical investigation of the composites demonstrates that the use of graphene nanoplatelets resulted in a significant rise in the composites’ storage modulus. Additionally, incorporating a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelets to the composites improves thermal stability, as seen by the highest degradation temperature of 330°C for 0.75GBK. The study aims to discover simple, low-cost ways to overcome the composite’s inadequate properties, enabling them to be used in a wider variety of applications.

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The development of eco-sustainable materials has become the focus of many researchers due to the environmental problems associated with the use of synthetic polymers [1]. In 2015, over 6,300 million metric tons of plastic trash were produced around the world. Approximately 9% was recycled, 12% was burned, and the rest was disposed of in landfills or spread across the environment. One of the eco-sustainable materials is biocomposites, which are composed of bioreinforcements such as natural fibers and biopolymers. According to Shebaz Ahmed et al. [2], the global biocomposites market is expected to develop at 9.59% per year, reaching USD 41 billion by 2025. Among biodegradable polymers, polylactic acid (PLA) has been known as the most promising biopolymer with the potential to change the common plastics in different applications and has remarkable qualities compared to synthetic polymers such as polystyrene and poly(ethylene terephthalate) [3,4,5,6]. PLA’s use is promising because of its numerous advantages, including its biocompatibility, transparency, biodegradability, high elastic modulus, and strength [7]. However, PLA has a major disadvantage, namely its price, which can be overcome by reinforcing it with natural fiber [8]. These fibers could be utilized to lower costs due to their low price [9].

Natural fiber offers several benefits, including being abundant, low density, high performance, recyclable, strong mechanical qualities, renewable, adaptability, low specific mass, non-toxic, and biodegradability [10,11,12,13,14]. However, employing natural fiber has a significant disadvantage: the hydrophilic behavior of natural fibers leads to fibers to expand and form voids at the matrix-fiber interface, resulting in poor mechanical properties of composites [15]. These fibers are made of lignocellulose, which includes hydroxyl groups, causing them to be hydrophilic and unsuitable for usage in a hydrophobic polymer [16]. Consequently, this problem must be overcome with chemical treatments that enhance the compatibility of natural fiber and matrix [17]. Alkali treatment is an easy and cost-effective process for fiber modification. Alkali treatment roughens the fiber surface by removing lignin, contaminants, and hemicellulose, which improves fiber and matrix adherence and mechanical characteristics [18]. Hence, this research employs alkaline treatment on the fibers.

Short natural fibers are chosen in this study, owing to the mixing process in the internal mixer between PLA and fiber. The use of short fibers enables a more uniform distribution within the polymer, but their mechanical characteristics tend to be lower compared to long fiber composites [19]. Furthermore, bamboo and kenaf fibers were used in this study; these two fibers were used because of their plentiful availability in Malaysia [20,21]. Also, bamboo and kenaf fibers represent another eco-friendly and biodegradable fiber source, showing promise in composites and wide industry applications [22,23]. However, the previous study by Khan et al. [24] found that using bamboo and kenaf fibers in reinforced PLA composites made them less strong, with a tensile strength of 17.82 MPa and a flexural strength of 33.18 MPa. This meant that the composites were not as strong as plain PLA. As a result of these concerns, the utilization of nanofiller material is being investigated. Nanofillers such as nanoplatelets, nanotubes, nanorods, and nanospheres are increasingly being added to polymers to enhance their mechanical characteristics and thermal stability [25].

In this study, graphene nanoplatelets are used. Graphene nanoplatelets represent a category of graphene materials, which consist of multiple layers of graphene that exhibit a platelet-like form and generally range from 5 to 50 nm in thickness [26]. Graphene nanoplatelets are chosen as nanofillers in this study due to their remarkable properties, which are high aspect ratio, light weight, thermal conductivity and electrical, enhanced mechanical performance, and low cost [27,28]. According to Gao et al. [29], using graphene nanoplatelets as fillers in PLA can rise the mechanical characteristics of the composites; however, a higher amount of graphene nanoplatelets can lead to a fall in the composites’ mechanical strength. Furthermore, Hussain et al. [30] also observed the same phenomenon: the use of graphene nanoplatelets in PLA improves tensile strength, but a higher amount results in a decline in mechanical strength. However, there are fewer studies conducted to analyze the influence of the incorporation of graphene nanoplatelets in the natural fiber-reinforced PLA composites.

Therefore, this research proposes a cost-effective and simple solution to the inadequate characteristics of bamboo/kenaf-reinforced PLA hybrid composites (BK composites) for industrial applications. Hence, this work comprehensively investigates the utilization of small amounts of graphene nanoplatelets as nanofillers in BK composites, a subject that has not received much attention in earlier studies. This research investigates several features of composites, including mechanical characteristics (tensile, flexural, impact, and hardness tests), dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), morphology, and thermal properties (thermogravimetric analysis [TGA] and differential scanning calorimeter [DSC]). The study aims to provide solutions to overcome the inadequate properties of the composites, thereby expanding their application in many areas, specifically for industrial applications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

PLA, Nature Works USA, Ingeo 2003D, with a density of 1.24 g/cm3, a 190°C of melting point, and 6 g/10 min of melt flow rate, was procured from Mecha Solve Engineering, Malaysia. The graphene nanoplatelets, supplied by GO Advanced Solutions Sdn. Bhd., Selangor, Malaysia, had a diameter of 2–7 m, an 0.06–0.09 g/mL of apparent density, a thickness of 2–10 nm, a 107–102 S/m of electrical conductivity, a carbon content of >99%, a 120–150 m2/g of surface area, and less than 2% water content. The analytical reagent NaOH (R&M Chemicals, Malaysia) was provided by Evergreen Engineering & Resources, Selangor, Malaysia. Bamboo culms (Schizostachyum brachycladum) were sourced from Kelantan, Malaysia, while kenaf fibers (Hibiscus cannabinus) were procured from the National Kenaf and Tobacco Board in Kelantan, Malaysia.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Bamboo and kenaf fibers preparation

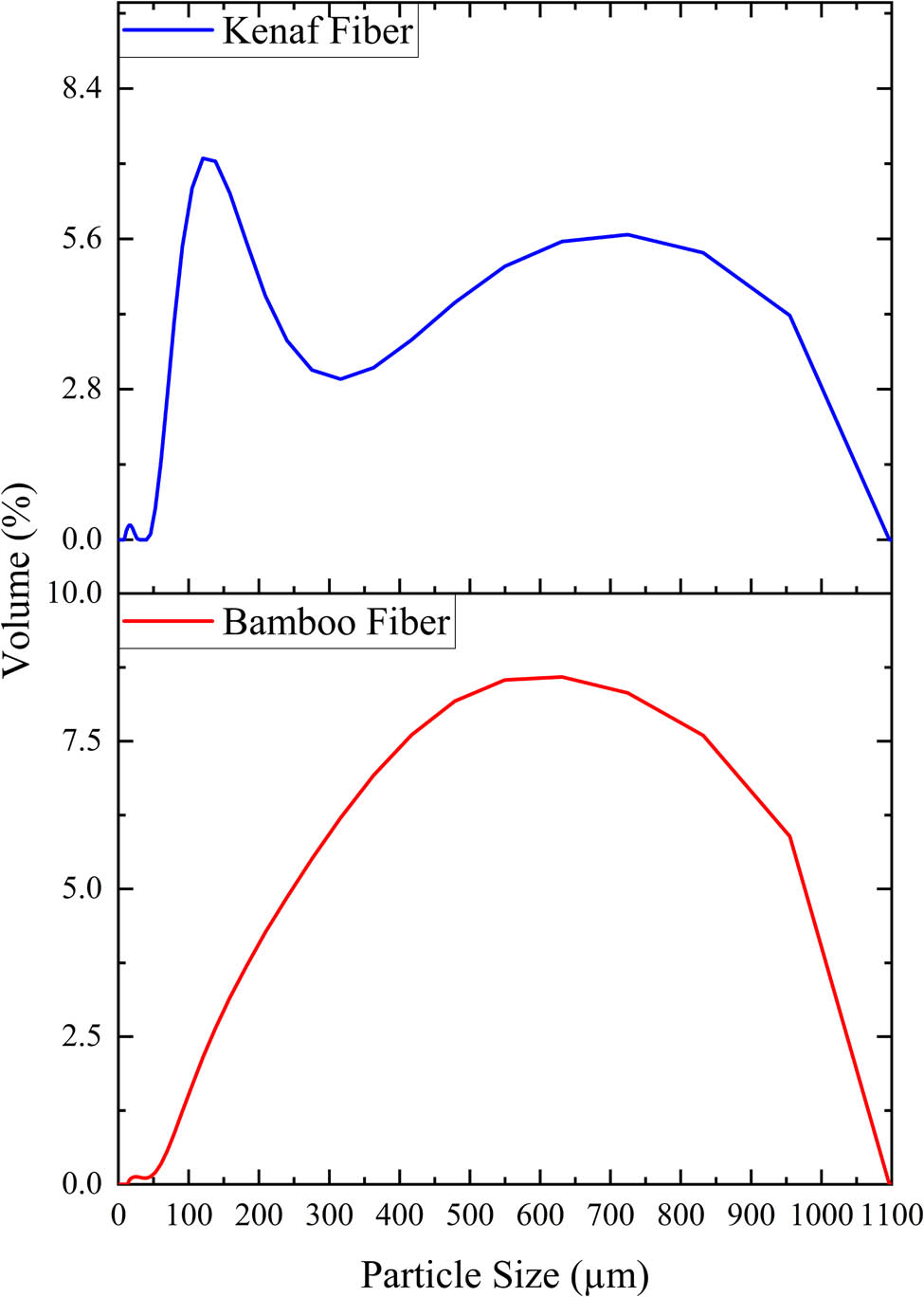

The preparation of bamboo and kenaf fibers, along with the alkali treatment, was conducted in accordance with established methodologies from prior research [31]. The bamboo culms were processed by being cut into strips using a knife, subsequently cleaned, and then subjected to sun drying. Following the drying process, the bamboo strips were cut into tiny pieces utilizing an electric bench saw (LB1200F, Makita Corp, Japan). Then, the tiny pieces underwent crushing utilizing a crusher (9FQ-350, Zhengzhou Shenwu New Mechanical and Electrical Co., Ltd., China). Initially, the kenaf fiber was processed by cutting it into shorter lengths with scissors to facilitate the subsequent pulverization process. Next, both of the fibers underwent a crushing process with a pulverizer fitted with a sieve cassette of 0.5 mm (Pulverisette 19 universal cutting mill, FRITSCH GmbH, Germany). Both fibers underwent an alkaline treatment by being soaked in a 5% w/w sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution for a duration of 48 h. After the treatment, the fibers underwent a washing process with distilled water until a pH of 7 was reached, followed by oven drying at 50°C for a duration of 30 h. The particle size of both fibers was recorded using a particle size analyzer (Metasizer 2000, Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK) to ascertain their precise particle size. Figure 1 illustrates the dimensions of fiber particles.

Particle size of bamboo and kenaf fibers.

2.2.2 Fabrication of composite samples

PLA matrix, bamboo and kenaf fibers, and graphene nanoplatelets filler were mixed with an internal mixer (50 EHT, Brabender GmbH, Germany) for 10 min at 190°C and 50 rpm. The materials were blended with dissimilar ratios of graphene nanoplatelet filler, specifically 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 phr (per hundred resin) and were labeled BK, 0.25 GBK, 0.5 GBK, 0.75 GBK, and 1 GBK, respectively. The composite sheets were created by compression molding the blended materials using a Technopress-40HC-B from Technovation, Malaysia. The procedure used a 150 mm × 150 mm × 3 mm mold, 170°C temperature, 60 bar pressure, a 10 min preheating, a 3-vent cycle, 13 min of full press, and 10 min of cooling.

3 Characterizations

3.1 Tensile test

The composite samples underwent tensile testing utilizing the Universal Testing Machine (UTM) INSTRON 3366 to determine tensile behavior, in accordance with ASTM D638-14 [32]. The testing procedure involved applying a cell load weight of 10 kN, conducted at room temperature. The crosshead speed was set to 2 mm/min, and each sample underwent five repetitions. Prior to testing, the dimensions of all composites were determined with digital calipers (CD-8 C, Mitutoyo Corporation, Japan). The samples were subsequently oven-dried for a duration of 12 h at 50°C.

3.2 Flexural test

The samples underwent a three-point flexural test utilizing the UTM INSTRON 3366 to determine flexural characteristics, in accordance with ASTM D790-17 [33]. The testing procedure involved applying a load weight of 10 kN at room temperature, with a 48 mm span length (maintaining a 16:1 ratio relative to the thickness of the sample), utilizing a 1 mm/min speed of crosshead, and conducting five duplications for each sample. Prior to testing, the dimensions of all composites were recorded with digital calipers (CD-8 C, Mitutoyo Corporation, Japan). Subsequently, the samples were subjected to drying at 50°C for a duration of 12 h in an oven.

3.3 Impact test

The composite samples underwent an Izod Pendulum Impact test using the INSTRON CEAST 9050 in order to evaluate their impact properties, as per ASTM D256 [34]. The experiment was conducted using a 0.5 J hammer under ambient temperature conditions, with five repetitions performed for each sample. Prior to conducting the tests, the samples were notched using an INSTRON CEAST manual notching machine with a depth and angle according to the standard. The thickness and width of all composites were recorded with a digital micrometer. Also, the composites were kept at 50°C in an oven for 12 h before test.

3.4 Hardness test

The hardness of the composites was measured with a digital shore type D durometer with a measuring range of 0–100 HD, according to ASTM D2240-15 [35]. The samples were placed on a flat surface before testing, then the instrument was pressed onto the samples for 1 s, and the instrument reading was recorded. The sample measurements were repeated at five points on the surface. The sample hardness is calculated as the average of the instrument readings.

3.5 Morphological of the composites

The sample’s morphology was observed using a JSM-7600F FESEM (JEOL Ltd., Japan) at 5 kV at magnifications of 200×, 500×, and 1,000×. Before being examined, the composites were coated to lower the electron charge with platinum for 2 min with a coater (JEC-3000FC, JEOL Ltd., Japan).

3.6 DMA

DMA was utilized using the DMA Q800 V20.24 Build 43 (TA Instruments Co., USA). The test was carried out with a sample measuring 17.5 mm × 13 mm × 2.5 mm with a single cantilever clamp at 1 Hz frequency, a temperature range of 30–145°C, and a 5°C/min heating rate.

3.7 TGA and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG)

TGA and DTG were utilized using TGA Q500 V20.13 Build 39 (TA Instruments Co., USA). The measurement was carried out with about 6 mg composite samples and heated from 25 to 700°C with 50 mL/min of nitrogen flow rate and 10°C/min of heating rate.

3.8 DSC

DSC was carried out using DSC Q20 V24.11 Build 124 (TA Instruments Co., USA). About 11 mg of composite samples was heated using a temperature range of 25–200°C, a 50 mL/min nitrogen flow rate, and a heating rate of 10°C/min.

3.9 Statistical analysis

The data from experimental results were subjected to an analysis of variance with SPSS software. The Tukey test was implemented to compare means at a significance level of 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05). Statistically significant differences are represented by the use of different letters in the figures.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Tensile properties

The tensile strength of BK composites improved as the graphene nanoplatelets loading increased, with 1 GBK exhibiting the highest tensile strength at 41.86 MPa, a significant increase of 63.39% compared to BK (25.62 MPa), as depicted in Figure 2(a). From Figure 3(a), it can be noticed that, in BK samples, the bamboo and kenaf fibers were agglomerated, making the lower mechanical strength compared to the neat PLA, in which, according to Nazrin et al. [36], the tensile strength of PLA is 49.08 MPa. Furthermore, Figure 3(a) shows not only agglomerated fiber, but the poor interfacial bonding between fibers and PLA also found resulting small gap between fibers and matrix, which also the reason of the low tensile characteristics of the composites because of the hydrophilic characteristic of the fibers and hydrophobic PLA matrix [37,38]. However, the increase in tensile strength of the graphene nanoplatelet-filled composites was due to the very high intrinsic mechanical behavior and high aspect ratio of graphene nanoplatelets [39]. The increases in tensile characteristics were also confirmed by the Scaffaro et al. [40] study, which stated that the use of graphene nanoplatelet filler rises the tensile strength of the Posidonia flour-reinforced PLA composites. The graphene nanoplatelets’ well dispersion in the composites also becomes the reason for the increase in the mechanical characteristics, as shown in Figure 3. Additionally, the rise in samples’ elongation at break as the graphene nanoplatelets’ amount rose, from 1.31% (BK) to 2.40% (1 GBK), can be explained by the rougher surface of the composites along with the rise in the graphene nanoplatelet filler, as shown in Figure 3(b)–(e). The rougher surface occurred due to the crack growth barriers of the composites since the strong adhesion between graphene nanoplatelets and PLA matrix led to a tortuous crack, which is evaluated in Section 4.5, and led to the increase in elongation at break. On the other hand, incorporating a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelet filler into the composites had no significant impact on the samples’ tensile modulus, resulting in a slight difference in the composite sample stiffness.

(a) Tensile characteristics; (b) flexural strength and modulus; (c) impact strength; and (d) hardness of the composite’s samples.

Tensile fracture image of (a) BK, (b) 0.25 GBK, (c) 0.5 GBK, (d) 0.75 GBK, and (e) 1 GBK.

4.2 Flexural properties

Flexural testing is a destructive test that evaluates the force required to bend a beam under three-point loading settings [41]. The incorporation of graphene nanoplatelets into the composites results in a slight rise in flexural strength, with values 71.67 MPa (0.25 GBK), 70.77 MPa (0.5 GBK), 71.12 MPa (0.75 GBK), and 68.84 MPa (1 GBK) compared to 63.48 MPa (BK), as depicted in Figure 2(b). The increased flexural strength is due to the high stiffness of graphene nanoplatelets, which have a high aspect ratio, as well as improved bending between components in the composites [42]. However, the flexural strength of the 1 GBK sample is slightly lower than that of other graphene nanoplatelet-filled composites. This was expected because the graphene nanoplatelets in the composite sample are agglomerated. This discussion is confirmed by Giner-Grau et al. [43], who stated that carbon particles agglomerated due to van der Waals interactions, which contact with other carbon-based entities rather than polymer chains and reduce reinforcing potential in the composites. On the other hand, the flexural modulus of the composites slightly declines with the incorporation of graphene nanoplatelets in the composites, which shows that the stiffness of the material reduces. This phenomenon was expected due to the fact that after rotary relaxation, graphene nanoplatelets can interact by direct contact or by bridging through polymer chains [44].

4.3 Impact properties

Impact testing was conducted on the composite samples to evaluate their capacity for absorbing immediate force [41]. The effect of graphene nanoplatelets addition on the BK composites’ impact strength is depicted in Figure 2(c). It was noticed that after filling the composites with graphene nanoplatelets, the impact strength was increased compared to BK samples, representing 3.32 kJ/m2 (0.25 GBK), 3.06 kJ/m2 (0.5 GBK), 3.33 kJ/m2 (0.75 GBK), and 3.63 kJ/m2 (1 GBK). As previously discussed in the section on tensile properties (see Section 4.1) and explained in Section 4.5, the tortuous crack that occurred in the graphene nanoplatelets-filled composites was due to the toughening effect of the graphene nanoplatelets present in the composites [45]. This phenomenon led to an increase in impact strength for the composites. Furthermore, according to Al-Maqdasi et al. [46], the increases in impact strength are due to the relatively good dispersion of the graphene nanoplatelet filler.

4.4 Hardness properties

The impact of the addition of graphene nanoplatelets to BK composites on their hardness is depicted in Figure 2(d). By testing the hardness of the composites, it was found that adding graphene nanoplatelet filler to the BK composites made them harder. The hardest composites had a value of 86.80 HD, which is 3.70% higher than the BK samples. However, it is worth noting that these increments in graphene nanoplatelets loading have no significant effect on the composites’ hardness values, which are 86.50 HD (0.25 GBK), 86.20 HD (0.5 GBK), 86.20 HD (0.75 GBK), and 86.80 HD (1 GBK). The increases in the hardness of the composites are due to the enhanced interfacial bonding on the graphene nanoplatelets-filled composites, which also increases other mechanical properties, including flexural, tensile, and impact strength. It is supported by the Batakliev et al. [47] study, who reported that using graphene nanoplatelets on PLA composites improves their hardness owing to the greater degree of interfacial bonding, resulting in improved load transmission between graphene nanoplatelets and PLA. Furthermore, the toughening effects of graphene nanoplatelets in composites, which are explained in the impact properties, also account for the increased hardness.

4.5 Dispersion of graphene nanoplatelet filler in bamboo/kenaf fiber PLA hybrid composites

The dispersion analyses of graphene nanoplatelet-filled BK composites were analyzed using field emission scanning electron microscope, using the tensile fracture of the composites, as depicted in Figure 3(a)–(e). The dispersion of the graphene nanoplatelets and bamboo/kenaf fiber in the composites is important due to the dispersion of this filler can influence the properties of the composites. In the Figures 3(b)–(e), it can be noticed clearly that the graphene nanoplatelets presence in the composites, which due to the graphene nanoplatelets filler in the composites have survived the high shearing during melt mixing, as confirmed by Kashi et al. [48] study. The graphene nanoplatelet filler is also well dispersed in all the samples, which can occur due to the hydrophobic graphene nanoplatelets having good adhesion with the hydrophobic PLA matrix. The increases in the graphene nanoplatelets filler also make the fracture surface rougher, which confirms that the graphene nanoplatelets and PLA matrix have strong bonding. This statement is confirmed by the Ab Ghani et al. [44] study, which stated that because of the good graphene nanoplatelet dispersion, the PLA matrix surface condition became rougher with the rise in graphene nanoplatelet loading. However, in the 1 GBK sample, graphene nanoplatelet agglomeration begins to develop, as predicted, because of the van der Waals contact between the graphene nanoplatelets, which results in graphene nanoplatelet agglomeration in the composites, as explained in the flexural section.

4.6 DMA

The effect of the addition of graphene nanoplatelets to BK composites on their storage modulus and tan delta is depicted in Figure 4. The DMA provides reliable information on the relaxation behavior of materials under varied temperature and frequency limitations [49].

(a) Storage modulus and (b) Tan delta of the samples.

Table 1 shows that the storage modulus among the graphene nanoplatelets-filled composites rises along with the increase in the graphene nanoplatelets loading, showing 2385.89 MPa (0.25 GBK), 2642.87 MPa (0.5 GBK), 2842.58 MPa (0.75 GBK), and 3119.76 MPa (1 GBK). This rise in storage modulus was attributed to the improved interfacial bonding, which resulted in better adhesion strength of the composites [50]. Additionally, these graphene nanoplatelet layers allow efficient stress transfer in the composites [49]. This phenomenon supported the increases in mechanical strength, which was explained in the previous section. Furthermore, according to a study by Liu et al. [51], the increases in storage modulus also occurred due to the higher modulus of graphene in the composites. On the other hand, in terms of glass transition temperature (T g), the temperature showed very few differences between all samples, which is in line with the Gao et al. [29] study, who stated that the use of graphene nanoplatelets did not significantly affect the mobility of the PLA matrix. Furthermore, this phenomenon was also confirmed by the Valapa et al. [52] study, who stated that the reinforcement of graphene did not lead to the formation of short-chain PLA molecules. However, in the lowest loading of GNP (0.25 GBK), samples exhibit a decrease in storage modulus compared to the BK samples. This decrease is anticipated as a result of the weak chemical bond between graphene and the polymer matrix, along with the stress concentration within the composites [53,54].

DMA data of the samples

| Sample code | Storage modulus at 30°C (MPa) | T g (°C)/storage modulus | T g (°C)/tan delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| BK | 2580.42 | 65.54 | 74.08 |

| 0.25 GBK | 2385.89 | 66.36 | 74.42 |

| 0.5 GBK | 2642.87 | 65.18 | 72.80 |

| 0.75 GBK | 2842.58 | 66.21 | 74.43 |

| 1 GBK | 3119.76 | 65.23 | 74.59 |

4.7 TGA and derivative (DTG)

The thermal stability studies through TGA and DTG are represented in Figure 5. It is evident that the composites underwent two stages of degradation. The first stage of degradation happens at 25–200°C and is linked to the bamboo/kenaf fiber in the composites. This is because water evaporates along with OH groups contained in the cellulose structure [55]. However, the moisture content in the first stage of degradation is reduced along with increases in graphene nanoplatelets loading in the composites, as can be seen in Table 2. This phenomenon occurs because the presence of graphene nanoplatelets creates a tortuous patch that allows water to absorb in the composites [42]. The second-stage thermal degradation process began at a temperature slightly above 225°C. Table 2 represents the temperatures corresponding to 10, 20, and 50% weight reductions (T 10%, T 20%, and T 50%), as well as the onset temperature (T onset) and the peak temperature of the maximum weight loss (T max) for the composites. It is noticeable that the temperature rose with the incorporation of graphene nanoplatelets compared to BK samples, which led to a rise in the thermal stability of the composites. The shape of graphene nanoplatelets creates a shielding effect that stops volatile decomposition products within the composites, which makes them more thermally stable [39]. Additionally, Cai et al. [50] stated that the added graphene nanoplatelets could act as weight transfer barriers against the volatile pyrolyzed products in the PLA matrix, thereby delaying the thermal degradation of the composites. However, in the 1 GBK samples, a slight decrease in the temperature is noticed. This phenomenon occurred as expected due to the agglomeration formation of graphene nanoplatelets in 1 GBK samples, which is shown in Figure 3(e).

(a) TGA and (b) DTG curve of the samples.

TGA and DSC data of the samples

| Sample code | TGA | DTG | DSC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T 10 (°C) | T 20 (°C) | T 50 (°C) | T onset (°C) | Moisture content (%) | T max (°C) | T g (°C) | T c (°C) | T m (°C) | |

| BK | 286.62 | 299.87 | 318.11 | 294.16 | 1.474 | 317.39 | 60.64 | 100.64 | 150.85 |

| 0.25 GBK | 287.71 | 301.11 | 320.56 | 296.87 | 1.294 | 324.23 | 60.83 | 102.91 | 151.59 |

| 0.5 GBK | 288.69 | 301.22 | 319.46 | 295.68 | 1.156 | 319.46 | 61.33 | 105.45 | 150.03 |

| 0.75 GBK | 293.27 | 307.05 | 326.69 | 303.98 | 1.093 | 330.54 | 61.22 | 106.97 | 151.69 |

| 1 GBK | 290.38 | 303.30 | 322.44 | 299.10 | 0.983 | 323.91 | 60.89 | 104.59 | 151.17 |

4.8 DSC

The utilization of a low quantity of graphene nanoplatelets in the BK composites changed their thermal characteristic, including their glass transition temperature (T g), crystallization temperature (T c), and melting temperature (T m). These properties were found using DSC analyses, as shown in Figure 6.

DSC curve of the samples.

Table 2 shows that adding graphene nanoplatelets did not significantly affect the T m and T g for all the composite samples. These temperatures stayed the same at about 151 and 61°C, respectively. This was also confirmed by Gao et al. [29], who stated that adding graphene nanoplatelets did not have a big effect on the T m and T g. Furthermore, the phenomenon of a small difference in T g between all the samples in the DSC analysis is consistent with the T g obtained by DMA, which exhibits the same behavior. On the other hand, it is noticeable that in the melting region there are two peaks, which can be attributed to the lamellar thickness and crystal morphology of PLA [56]. However, the addition of graphene nanoplatelets to the composites leads to a rise in T c, but in the 1 GBK sample, it decreased, which is attributed to the nucleating effect of graphene nanoplatelets [57]. In addition, the T c of 1 GBK samples behaved similarly, with the slight loss of thermal stability, which was expected because of the graphene nanoplatelet agglomeration on the composites.

5 Conclusions

This study looked into the utilization of a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelets in BK composites to improve their poor characteristics. This study found that incorporating a low quantity of graphene nanoplatelets into the composites enhanced their strength. The composites had a tensile strength of 41.86 MPa (1 GBK), flexural strength of 71.67 MPa (0.25 GBK), impact strength of 3.63 kJ/m2 (1 GBK), and hardness of 86.80 HD (1 GBK). Furthermore, the morphology indicates that graphene nanoplatelets are well dispersed in the composites. Additionally, the DMA of the composites reveals that the addition of graphene nanoplatelets solely influences the storage modulus, leading to a significant rise in the composites’ storage modulus, while the change in T g is negligible. The utilization of a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelets did not affect the composites’ T g or T m. However, incorporating a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelets into the composites improves their thermal stability, as evidenced by the highest degradation temperature of 330°C for 1 GBK. Additionally, the incorporation of graphene nanoplatelets raises the T c in the composite materials. The utilization of a small quantity of graphene nanoplatelets can enhance composites’ insufficient qualities, allowing them to be utilized in a wide range of industrial applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia for the financial support received via the Higher Institution Centre of Excellence (HICoE grant, vote number: 5210003) at the Institute of Tropical Forestry and Forest Products (INTROP), Universiti Putra Malaysia.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia via the Higher Institution Centre of Excellence (HICoE grant, vote number: 5210003) at the Institute of Tropical Forestry and Forest Products (INTROP), Universiti Putra Malaysia.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Salwa HN, Sapuan SM, Mastura MT, Zuhri MY. Green bio composites for food packaging. Int J Recent Technol Eng. 2019;8:450–9. 10.35940/ijrte.B1088.0782S419.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Shebaz Ahmed JP, Satyasree K, Rohith Kumar R, Meenakshisundaram O, Shanmugavel S. A comprehensive review on recent developments of natural fiber composites synthesis, processing, properties, and characterization. Eng Res Express. 2023;5:032001. 10.1088/2631-8695/aceb2d.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kadea S, Kittikorn T, Hedthong R. Sustainable laminate biocomposite of wood pulp/PLA with modified PVA-MFC compatibilizer: weathering resistance and biodegradation in soil. Ind Crop Prod. 2024;218:118913. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118913.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Czajka A, Plichta A, Bulski R, Pomilovskis R, Iuliano A, Cygan T, et al. PLA reinforced with modified chokeberry pomace and beetroot pulp fillers effect of oligomeric chain extender on the properties of biocomposites. Polymer (Guildf). 2023;289:126472. 10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126472.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Chaitanya S, Singh I, Il Song J. Recyclability analysis of PLA/sisal fiber biocomposites. Compos Part B Eng. 2019;173:106895. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.05.106.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Azka MA, Sapuan SM, Abral H, Zainudin ES, Aziz FA. An examination of recent research of water absorption behavior of natural fiber reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) composites: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;268:131845. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131845.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Ruz-Cruz MA, Herrera-Franco PJ, Flores-Johnson EA, Moreno-Chulim MV, Galera-Manzano LM, Valadez-González A. Thermal and mechanical properties of PLA-based multiscale cellulosic biocomposites. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;18:485–95. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.02.072.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Komal UK, Lila MK, Singh I. PLA/banana fiber based sustainable biocomposites: A manufacturing perspective. Compos Part B Eng. 2020;180:107535. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107535.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chen K, Li P, Li X, Liao C, Li X, Zuo Y. Effect of silane coupling agent on compatibility interface and properties of wheat straw/polylactic acid composites. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;182:2108–16. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.207.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Reddy BM, Mohana Reddy YV, Mohan Reddy BC, Reddy RM. Mechanical, morphological, and thermogravimetric analysis of alkali-treated cordia-dichotoma natural fiber composites. J Nat Fibers. 2020;17:759–68. 10.1080/15440478.2018.1534183.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kumar R, Ul Haq MI, Raina A, Anand A. Industrial applications of natural fibre-reinforced polymer composites – challenges and opportunities. Int J Sustain Eng. 2019;12:212–20. 10.1080/19397038.2018.1538267.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kareem A, Venkat Reddy P, Snehith Kumar V, Buddi T. Influence of the stacking on mechanical and physical properties of jute/banana natural fiber reinforced polymer matrix composite. Mater Today Proc. 2023. 10.1016/j.matpr.2023.11.017.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Nurnadia A, Roshafima RA, Shazwani ALN, Hafizah A, Yunus WMZW, Fatehah R. Effect of silane treatment on rise straw/high density polyethylene biocomposites. J Nat Fibre Polym Compos. 2023;2:3.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Asim M, Paridah MT, Chandrasekar M, Shahroze RM, Jawaid M, Nasir M, et al. Thermal stability of natural fibers and their polymer composites. Iran Polym J. 2020;29:625–48. 10.1007/s13726-020-00824-6.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Gholampour A, Ozbakkaloglu T. A review of natural fiber composites: properties, modification and processing techniques, characterization, applications. J Mater Sci. 2020;55:829–92. 10.1007/s10853-019-03990-y.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Elfaleh I, Abbassi F, Habibi M, Ahmad F, Guedri M, Nasri M, et al. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: An eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results Eng. 2023;19:101271. 10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101271.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Nurazzi NM, Asyraf MRM, Rayung M, Norrrahim MNF, Shazleen SS, Rani MSA, et al. Thermogravimetric analysis properties of cellulosic natural fiber polymer composites: a review on influence of chemical treatments. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13:2710. 10.3390/polym13162710.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Olonisakin K, Fan M, Xin-Xiang Z, Ran L, Lin W, Zhang W, et al. Key improvements in interfacial adhesion and dispersion of fibers/fillers in polymer matrix composites; Focus on PLA matrix composites. Compos Interfaces. 2022;29:1071–120. 10.1080/09276440.2021.1878441.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Akhyar, Gani A, Ibrahim M, Ulmi F, Farhan A. The influence of different fiber sizes on the flexural strength of natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Results Mater. 2024;21:100534. 10.1016/j.rinma.2024.100534.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Yusof FM, Wahab NA, Abdul Rahman NL, Kalam A, Jumahat A, Mat Taib CF. Properties of treated bamboo fiber reinforced tapioca starch biodegradable composite. Mater Today Proc. 2019;16:2367–73. 10.1016/j.matpr.2019.06.140.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Asyraf MRM, Rafidah M, Azrina A, Razman MR. Dynamic mechanical behaviour of kenaf cellulosic fibre biocomposites: A comprehensive review on chemical treatments. Cellulose. 2021;28:2675–95. 10.1007/s10570-021-03710-3.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hiremath VS, Reddy DM, Reddy Mutra R, Sanjeev A, Dhilipkumar T, Naveen J. Thermal degradation and fire retardant behaviour of natural fibre reinforced polymeric composites- A comprehensive review. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;30:4053–63. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.04.085.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Xu D, He S, Leng W, Chen Y, Wu Z. Replacing plastic with bamboo: a review of the properties and green applications of bamboo-fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Polym (Basel). 2023;15:4276. 10.3390/polym15214276.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Khan A, Sapuan SM, Zainudin ES, Zuhri MYM. Physical, mechanical and thermal properties of novel bamboo/kenaf fiber-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) hybrid composites. Compos Commun. 2024;51:102103. 10.1016/j.coco.2024.102103.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Siddiqui VU, Sapuan SM, Hassan MR. Innovative dispersion techniques of graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) through mechanical stirring and ultrasonication: impact on morphological, mechanical, and thermal properties of epoxy nanocomposites. Def Technol. 2025;43:13–25. 10.1016/j.dt.2024.04.018.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Yusuf J, Sapuan SM, Rashid U, Ilyas RA, Hassan MR. Thermal, mechanical, thermo‐mechanical and morphological properties of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced green epoxy nanocomposites. Polym Compos. 2024;45:1998–2011. 10.1002/pc.27900.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Cataldi P, Athanassiou A, Bayer IS. Graphene nanoplatelets-based advanced materials and recent progress in sustainable applications. Appl Sci. 2018;8:1438. 10.3390/app8091438.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Saberi M, Ansari R, Hassanzadeh-Aghdam MK. Predicting the electrical conductivity of short carbon fiber/graphene nanoplatelet/polymer composites. Mater Chem Phys. 2023;309:128324. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.128324.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Gao Y, Picot OT, Bilotti E, Peijs T. Influence of filler size on the properties of poly(lactic acid) (PLA)/graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) nanocomposites. Eur Polym J. 2017;86:117–31. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.10.045.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Hussain M, Khan SM, Shafiq M, Al-Dossari M, Alqsair UF, Khan SU, et al. Comparative study of PLA composites reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets, graphene oxides, and carbon nanotubes: Mechanical and degradation evaluation. Energy. 2024;308:132917. 10.1016/j.energy.2024.132917.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Azka MA, Sapuan SM, Zainudin ES. Water absorption properties of graphene nanoplatelets filled bamboo/kenaf reinforced polylactic acid hybrid composites. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;285:138411. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.138411.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D638-14, standard test method for tensile properties of plastics. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2022. p. 1–17. 10.1520/D0638-14.Search in Google Scholar

[33] American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D790-17, standard test methods for flexural properties of unreinforced and reinforced plastics and electrical insulating materials. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2017. p. 1–12. 10.1520/D0790-17.Search in Google Scholar

[34] American Society for Testing And Materials. ASTM D256, standard test methods for determining the izod pendulum impact resistance of plastics. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2023. p. 1–20. 10.1520/D0256-23E01.Search in Google Scholar

[35] American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D2240-15, standard test method for rubber property durometer hardness. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2015. p. 1–13. 10.1520/D2240-15.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Nazrin A, Sapuan SM, Zuhri MYM. Mechanical, physical and thermal properties of sugar palm nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic starch (TPS)/poly (lactic acid) (PLA) blend bionanocomposites. Polymers (Basel). 2020;12:2216. 10.3390/polym12102216.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Fang X, Li Y, Zhao J, Xu J, Li C, Liu J, et al. Improved interfacial performance of bamboo fibers/polylactic acid composites enabled by a self-supplied bio-coupling agent strategy. J Clean Prod. 2022;380:134719. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134719.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Chung T-J, Park J-W, Lee H-J, Kwon H-J, Kim H-J, Lee Y-K, et al. The improvement of mechanical properties, thermal stability, and water absorption resistance of an eco-friendly PLA/kenaf biocomposite using acetylation. Appl Sci. 2018;8:376. 10.3390/app8030376.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Kashi S, Gupta RK, Kao N, Hadigheh SA, Bhattacharya SN. Influence of graphene nanoplatelet incorporation and dispersion state on thermal, mechanical and electrical properties of biodegradable matrices. J Mater Sci Technol. 2018;34:1026–34. 10.1016/j.jmst.2017.10.013.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Scaffaro R, Maio A, Gulino EF, Pitarresi G. Lignocellulosic fillers and graphene nanoplatelets as hybrid reinforcement for polylactic acid: effect on mechanical properties and degradability. Compos Sci Technol. 2020;190:108008. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.108008.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Prabhudass JM, Palanikumar K, Natarajan E, Markandan K. Enhanced thermal stability, mechanical properties and structural integrity of MWCNT filled bamboo/kenaf hybrid polymer nanocomposites. Materials (Basel). 2022;15:506. 10.3390/ma15020506.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Sheshmani S, Ashori A, Arab Fashapoyeh M. Wood plastic composite using graphene nanoplatelets. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;58:1–6. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.03.047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Giner-Grau S, Lazaro-Hdez C, Pascual J, Fenollar O, Boronat T. Enhancing polylactic acid properties with graphene nanoplatelets and carbon black nanoparticles: A study of the electrical and mechanical characterization of 3D-printed and injection-molded samples. Polymers (Basel). 2024;16:2449. 10.3390/polym16172449.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Ab Ghani NF, Mat Desa MSZ, Bijarimi M. The evaluation of mechanical properties graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polylactic acid nanocomposites. Mater Today Proc. 2021;42:283–7. 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.01.501.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Dlouhy I, Tatarko P, Bertolla L, Chlup Z. Nano-fillers (nanotubes, nanosheets): do they toughen brittle matrices? Procedia Struct Integr. 2019;23:431–8. 10.1016/j.prostr.2020.01.125.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Al-Maqdasi Z, Gong G, Nyström B, Emami N, Joffe R. Characterization of wood and graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) reinforced polymer composites. Materials (Basel). 2020;13:2089. 10.3390/ma13092089.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Batakliev T, Georgiev V, Angelov V, Ivanov E, Kalupgian C, Muñoz PAR, et al. Synergistic effect of graphene nanoplatelets and multiwall carbon nanotubes incorporated in PLA matrix: nanoindentation of composites with improved mechanical properties. J Mater Eng Perform. 2021;30:3822–30. 10.1007/s11665-021-05679-3.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Kashi S, Gupta RK, Baum T, Kao N, Bhattacharya SN. Morphology, electromagnetic properties and electromagnetic interference shielding performance of poly lactide/graphene nanoplatelet nanocomposites. Mater Des. 2016;95:119–26. 10.1016/j.matdes.2016.01.086.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Adesina OT, Sadiku ER, Jamiru T, Ogunbiyi OF, Adesina OS. Thermal properties of spark plasma -sintered polylactide/graphene composites. Mater Chem Phys. 2020;242:122545. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122545.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Cai C, Liu L, Fu Y. Processable conductive and mechanically reinforced polylactide/graphene bionanocomposites through interfacial compatibilizer. Polym Compos. 2019;40:389–400. 10.1002/pc.24663.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Liu W, Zhang S, Yang K, Yu W, Shi J, Zheng Q. Preparation of graphene-modified PLA/PBAT composite monofilaments and its degradation behavior. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;20:3784–95. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.08.125.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Valapa RB, Pugazhenthi G, Katiyar V. Effect of graphene content on the properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2015;5:28410–23. 10.1039/C4RA15669B.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Ahmed RM, Atta MM, Taha EO. Optical spectroscopy, thermal analysis, and dynamic mechanical properties of graphene nano-platelets reinforced polyvinylchloride. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2021;32:22699–717. 10.1007/s10854-021-06756-y.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Jesuarockiam N, Jawaid M, Zainudin ES, Thariq Hameed Sultan M, Yahaya R. Enhanced thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of synthetic/natural hybrid composites with graphene nanoplateletes. Polymers (Basel). 2019;11:1085. 10.3390/polym11071085.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Wang F, Zhou S, Yang M, Chen Z, Ran S. Thermo-mechanical performance of polylactide composites reinforced with alkali-treated bamboo fibers. Polymers (Basel). 2018;10:401. 10.3390/polym10040401.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Gonçalves C, Pinto A, Machado AV, Moreira J, Gonçalves IC, Magalhães F. Biocompatible reinforcement of poly(lactic acid) with graphene nanoplatelets. Polym Compos. 2018;39:E308–20. 10.1002/pc.24050.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Rogovina S, Lomakin S, Usachev S, Gasymov M, Kuznetsova O, Shilkina N, et al. The study of properties and structure of polylactide–graphite nanoplates compositions. Polym Cryst. 2022;2022:4367582. 10.1155/2022/4367582.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”