Abstract

In this article, we are interested in the standard finite element approximation method of linear additive Schwarz iterations for a class of semi-linear elliptic problems, for two subdomains, in the context of non-matching grids. More precisely, by means of a uniform convergence result from the study by Lui and a fundamental lemma consisting of estimating, at each iteration, the gap between the continuous and the finite element Schwarz iterates, we prove that the discrete Schwarz sequences converge, in the maximum norm, to the true solution. Moreover, we also give numerical results to support the theoretical findings.

1 Introduction

The Schwarz method can be used to solve elliptic boundary value problems on domains which consist of two or more overlapping subdomains. The solution is approximated by an infinite sequence of functions that result from solving a sequence of elliptic boundary value problems in each of the subdomains. The literature in this area is extensive and one can refer to the previous studies [1,2] and to proceedings of the annual International Symposium on Domain Decomposition for Partial Differential Equations, starting from the study by Glowinski et al. [3].

The mathematical analysis of the Schwarz alternating method for elliptic boundary value problems has been extensively studied in the last four decades (c.f., e.g., [1–7] and the references therein). However, the literature offers only a limited number of works that address convergence and error estimation analysis for discrete Schwarz algorithms, particularly with regards to non-matching discretizations in numerical analysis (c.f. [8–16]).

Non-matching discretizations have proven to be very advantageous for solving problems that cannot be handled by global discretizations. They are earning a great interest among engineers and computational experts as they enable the choice of different discretization techniques, order of approximating polynomials, and mesh sizes on different subdomains depending on the varying properties of the solution (e.g., sharp gradients or singularities) throughout the domain and the physics of the practical problem required to be captured.

In the present article, we are interested in the finite element convergence analysis of a monotone additive method for the semilinear Dirichlet problem

Here,

To be more specific, let

where

Note that the subproblems (1.2) are independent and, therefore, can be solved in parallel.

In this article, our aim is to approximate problem (1.2) by a finite element method on both subdomains

where

To that end, we develop a method that combines a uniform convergence result of linear monotone additive Schwarz iterations, and a key lemma that consists of estimating, at each iteration, the gap between the continuous Schwarz sequence and its finite element counterpart, respectively.

The additive Schwarz method is in general preferable to the multiplicative and alternating Schwarz methods because the Schwarz subproblems are independent and hence can be solved in parallel [4,7]. Consequently, the analysis and results of this article may constitute a good theoretical background for future computational work.

The layout of this article is as follows. In Section 2, we recall some standard results related to linear elliptic boundary problems, and the existence of a solution for nonlinear partial differential equations (PDEs). In Section 3, we define both the continuous and discrete variational formulations of subproblems (1.2). In Section 4, we discuss the

2 Preliminaries

The purpose of this section is to recall some definitions and classical results, which will be needed throughout the article.

2.1 Linear elliptic problems

Consider the second order linear elliptic problem: Find

where

where

and

Note that

2.1.1 Finite element discretization

Let

where

and

Discrete maximum principle (DMP) assumption: We assume that the stiffness matrix

In view of [18,20] under a

Lemma 1

[10] Let

Notation 1

Let

2.2 The semilinear problem

Let us consider again the nonlinear PDE: Find

Definition 1

[21] A function

Definition 2

[21] A function

Suppose that (2.9) has a subsolution

Furthermore, assume that there exists

Then, thanks to [21], problem (2.9) has a solution (not necessarily unique) in

Theorem 1

[7] (Convergence of Schwarz sequences)

Let

3 Approximation of linear additive Schwarz subproblem

This section is devoted to the finite element approximation of the subproblems (1.2).

3.1 Continuous variational Additive Schwarz subproblem

Let

where

and

3.2 Finite element discretization

Let

and

where

3.3 Discrete variational additive Schwarz subproblems

Let

where

and

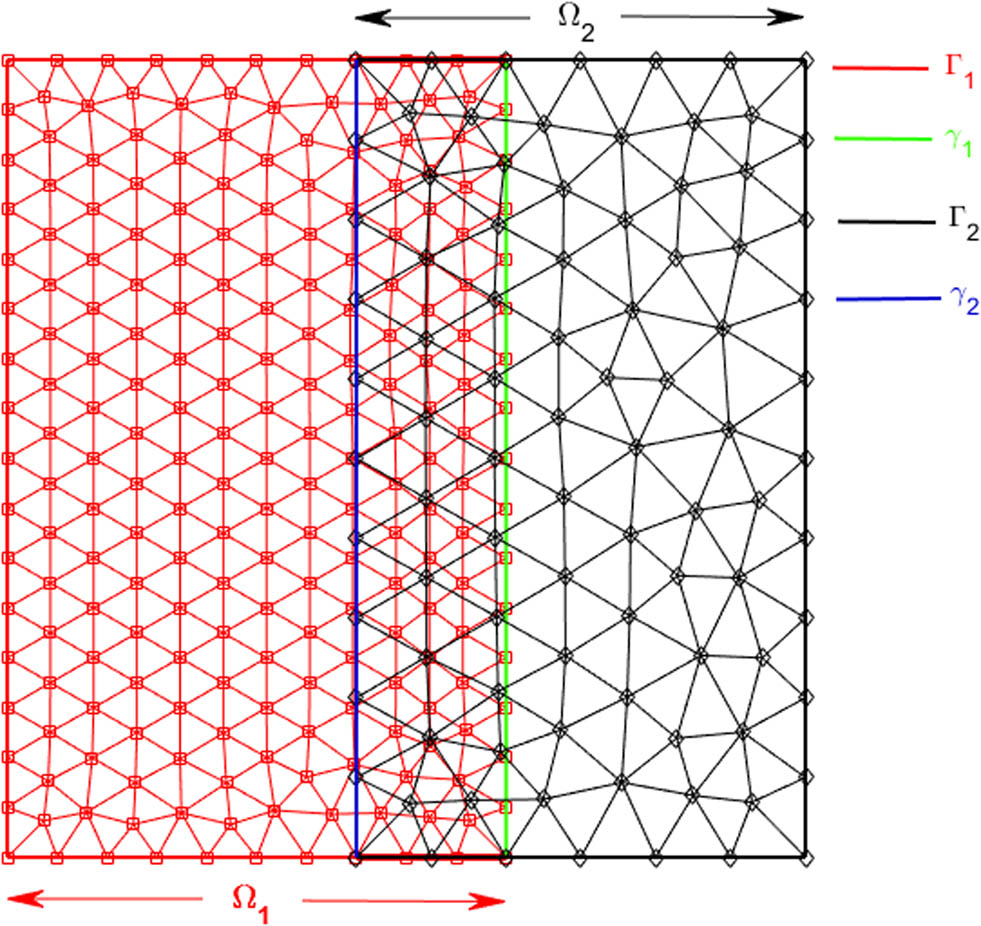

Example of quasi-uniform triangular non-matching meshes on two overlapping subdomains.

4

L

∞

-convergence analysis

This section is devoted to proving the main result of this article. For that, we first introduce the finite element counterparts of subproblems (3.1) and prove a key lemma.

4.1 Finite elements counterparts of subproblems (3.1)

For

where

and

Lemma 2

[20] Assume that

Then we have

Notation 2

For the sake of simplicity, we shall adopt the following notations in the proof of lemma 3:

and

4.2 The main result

The proof of the main result stands on the following crucial lemma whose proof can be found in Appendix A.

Lemma 3

Assume that

Then, we have

and

where

We are now in a position to prove the main result of this article.

Theorem 2

There exists

Proof

Let us give the proof for subdomain

Letting

On the other hand, since

and

where

where

Thus, (4.5) follows by choosing

5 Numerical experiments

In this section, we perform a series of numerical experiments to support the theoretical results. To solve the semi linear problem, we use the linear additive Schwarz algorithm. For this purpose, we adapt a finite element code using the software “FreeFEM++” [22].

We consider the problem: find

where

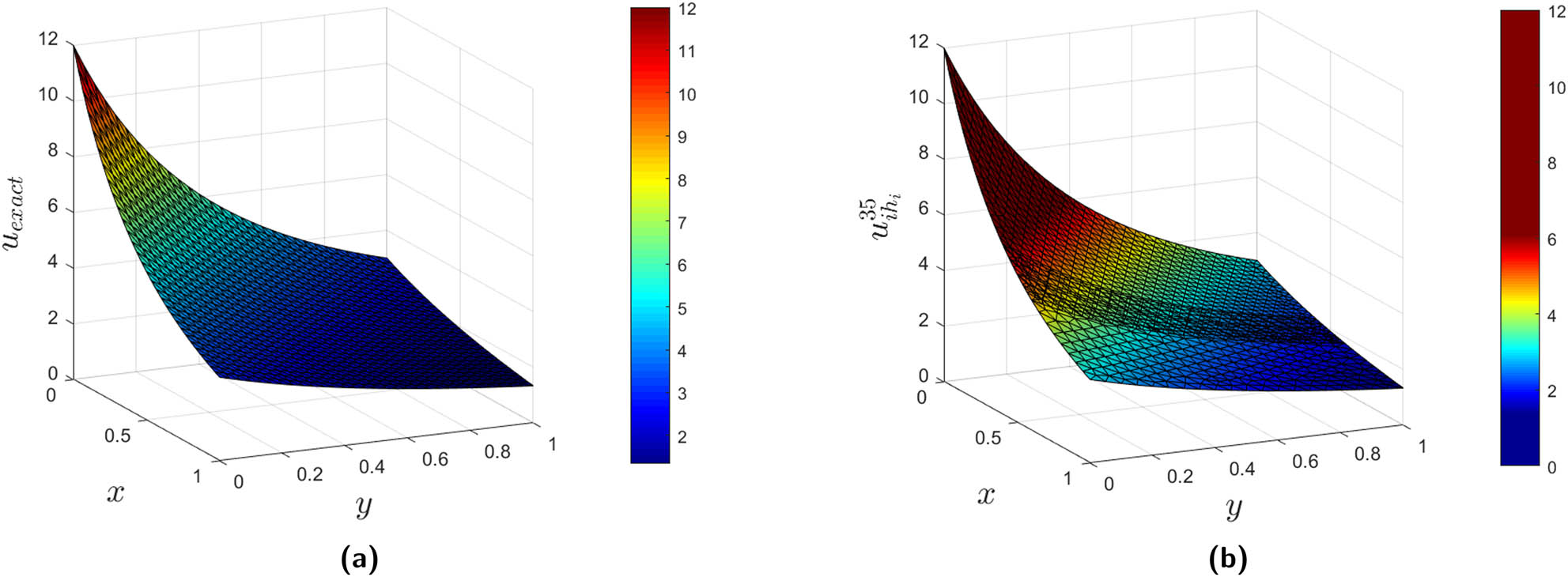

(a) The exact solution and (b) the numerical solution for

The coefficient

Each subdomain is independently discretized with a linear quasi-uniform mesh triangular elements and different mesh size. As a consequence, the resulting grid in the intersection region between the two subdomains is non-matching. To satisfy the DMP, FreeFEM++ uses a variable metric/Delaunay automatic meshing algorithm accounting for the maximum edge length for every element

Initial results show the overall behavior of the proposed Schwarz algorithm. The first experiment is done by splitting the domain

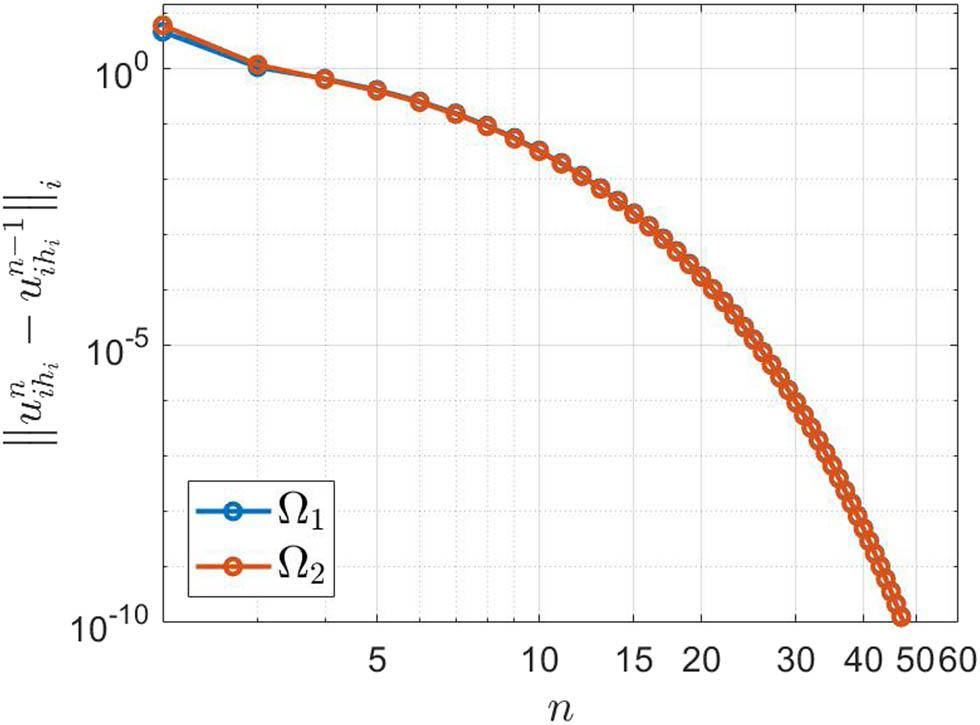

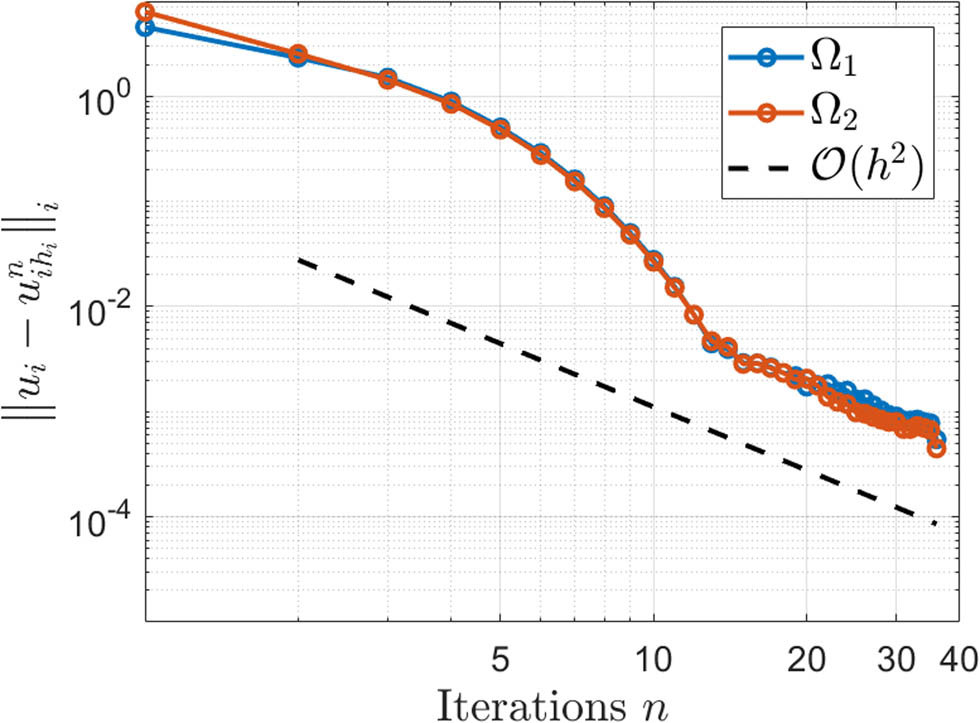

Furthermore, the monotone convergence of the discrete Schwarz sequences

Monotone convergence.

In the following numerical experiments, we investigate the effect of different parameters on the convergence of the discrete Schwarz sequences.

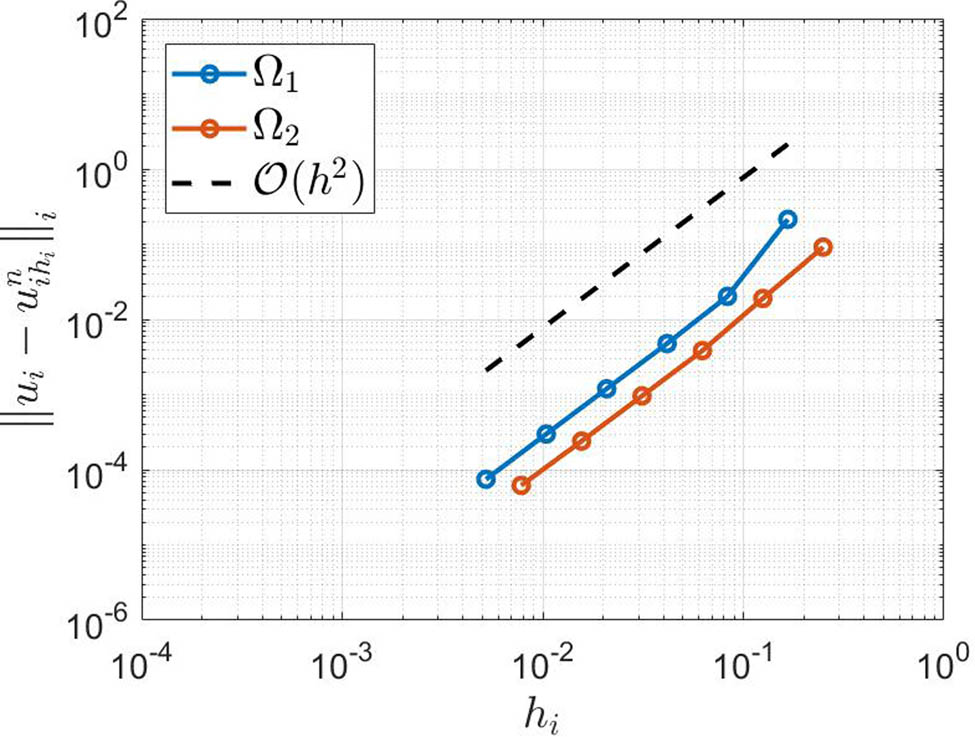

5.1 The effect of changing mesh size

h

i

as

n

increases

This experiment is devoted for numerically proving Theorem 2. As it states, the mesh size

|

Algorithm 1: Effect of simultaneously changing

|

|---|

|

|

|

while

|

|

|

| Re-mesh subdomains: |

| Mesh

|

| Define boundary conditions (BCs): |

| Impose the BC function g on

|

| Interpolate discrete sequences: |

| Interpolate the discrete sequence

|

| Interpolate the discrete sequence

|

| Solve subproblems: |

| Apply prolongation operators on the solutions

|

| Solve in parallel the linear systems corresponding to both subproblems to obtain

|

|

|

Here, we consider the domain

Numerical validation of Theorem 2.

5.2 The effect of mesh size

h

i

In this experiment, the overlapping subdomains setup here is similar to that employed in the previous subsection except the mesh sizes are chosen to be

Meshsizes versus maximum errors.

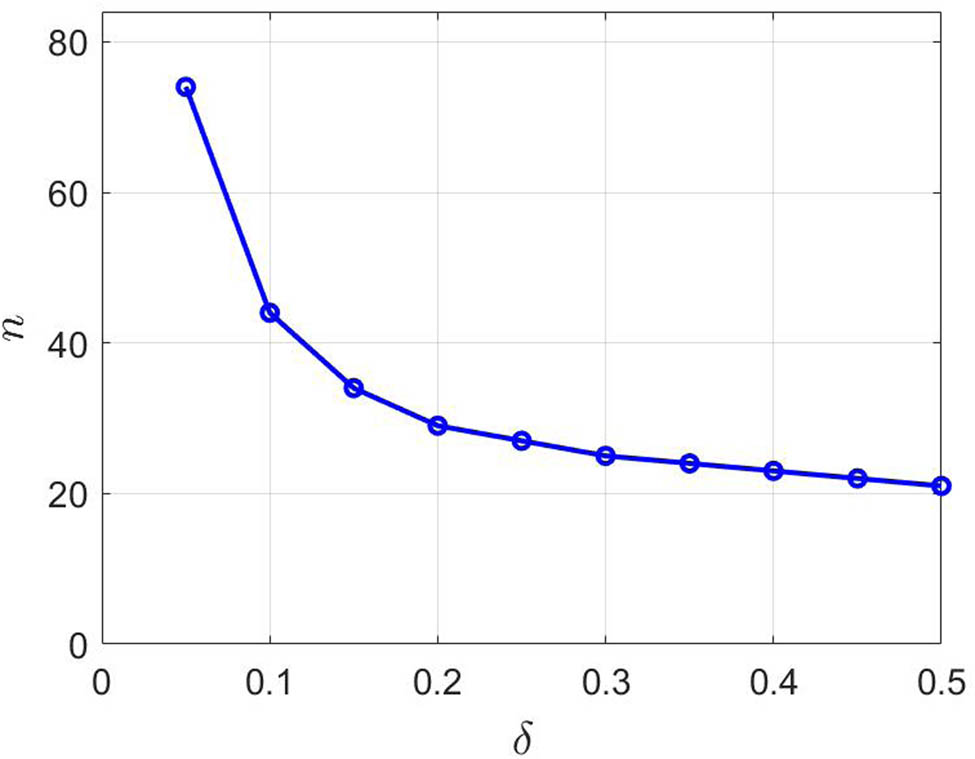

5.3 The effect of the overlap size

δ

The effect of the overlap size

Effect of the overlap size.

6 Conclusion

We have shown mathematically and numerically the convergence of the standard finite element approximation of linear monotone additive Schwarz procedure for semilinear scalar elliptic PDEs, in the context of nonmatching grids. To prove the main result, we estimated, at each iteration, the error between the continuous and discrete Schwarz additive sequences. Moreover, we conducted several numerical experiments to validate our theoretical findings. The numerical results proved the monotone convergence of the discrete additive Schwarz sequences by monitoring the maximum values of the difference between consecutive discrete Schwarz iterations. Some numerical experiments were extended to investigate the effect of some parameters on the error defined as the maximum norm between the exact solution and the discrete Schwarz sequences. The numerical experiments have also provided a second-order convergence.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their gratitude to Sultan Qaboos University for providing excellent research facilities and financial support for the publication fees.

-

Funding information: This work has not received any external funding.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Messaoud Boulbrachene handled the mathematical analysis part, while Qais Al Farei did the numerical analysis and numerical experimentation parts.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

-

Images: We confirm that all images contained in this manuscript are original.

Appendix A The proof of lemma 3

Proof

The proof will be carried out by induction. Also, we shall ignore the boundary condition on

Indeed, for

Here, we need to consider the following two cases:

or

Case 1 implies that

while case 2 implies that

because

Thus, both cases give

For [

Again, we need to consider the following two cases:

or

Case 1 implies that

while case 2 implies that

because

Thus, both cases give

For [

We then have to distinguish between two cases

or

Using (A1), case 1 implies that

while case 2 implies that

But

(a)

(b)

because

(c)

because

(d)

From all the previous subcases, we can say that

So, by using (A2), we obtain

Thus, both cases yield

For

As mentioned earlier, we have two possible cases

or

From (A2), case 1 implies that

whereas case 2 gives

But

(a)

(b)

because

(c)

because

(d)

From all the previous subcases, we have

So, by using (A1), we obtain

Thus, in both cases, we obtain

Now assume that both (4.3) and (4.4) hold. We need to prove the lemma for the (

As above, we need to distinguish between two cases.

Case 1:

By (4.3), this gives

Case 2:

which gives

But

(a)

(b)

since

(c)

since

(d)

From all previous subcases of

As a consequence of (4.4), we have

Hence, in both cases, we obtain

Likewise, we have in

Again here, we need to discuss two cases.

Case 1:

By (4.4), this gives

Case 2:

Similarly, after studying all subcases of

As a consequence of (4.3), this gives

Hence, both cases yield

which completes the proof.□

References

[1] Lions PL. On the Schwarz alternating method I. First international symposium on domain decomposition methods for partial differential equations. Philadelphia Pa, USA: SIAM; 1988. p. 1–40. Search in Google Scholar

[2] Lions PL. On the Schwarz alternating method II. Second international symposium on domain decomposition methods for partial differential equations. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: SIAM; 1989. p. 47–70. Search in Google Scholar

[3] Glowinski R, Golub GH, Meurant GA, Periaux J. Domain decomposition methods for partial differential equations. First international symposium on domain decomposition methods for partial differential equations. Philadelphia, PA, USA: SIAMl; 1988. Search in Google Scholar

[4] Dryja M, Widlund OB. An additive variant of the Schwarz alternating method for the case of many subregions. Technical report. Courant Institute technical report 339. 1987. Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lui SH. On Schwarz alternating methods for nonlinear elliptic PDEs. SISC. 1999;21(4):1506–23. 10.1137/S1064827597327553Search in Google Scholar

[6] Lui SH. On monotone and Schwarz alternating methods for nonlinear elliptic PDEs. ESAIM M2AN. 2001;35(1):1–15. 10.1051/m2an:2001104Search in Google Scholar

[7] Lui SH. On linear monotone iteration and Schwarz methods for nonlinear elliptic PDEs. Numer Math. 2002;93(1):109–29. 10.1007/BF02679439Search in Google Scholar

[8] Boulbrachene M, Cortey-Dumont Ph, Miellou JC. Mixing finite elements and finite differences in a subdomain method. First international symposium on domain decomposition methods for partial differential equations. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: SIAM; 1988. p. 198–216. Search in Google Scholar

[9] Boulbrachene M, Saadi S. Maximum norm analysis of an overlapping nonmatching grids method for the obstacle problem. Adv Differ Equations. 2006;2006:85807. 10.1155/ADE/2006/85807Search in Google Scholar

[10] Harbi A, Boulbrachene M. Maximum norm analysis of a non-matching grids method for nonlinear elliptic PDEs. J Appl Math. 2011;2011:605140.10.1155/2011/605140Search in Google Scholar

[11] Harbi A. Maximum norm analysis of an arbitrary number of non-matching grids method for nonlinear elliptic PDEs. J Appl Math. 2013;2013:893182.10.1155/2013/893182Search in Google Scholar

[12] Boulbrachene M, Al Farei Q. Maximum norm error analysis of a non-matching grids finite element method for linear PDEs. Appl Math Comput. 2014;238:21–9. 10.1016/j.amc.2014.03.146Search in Google Scholar

[13] Harbi A. Maximum norm analysis of a non-matching grids method for a class of variational inequalities with nonlinear source terms, J Inequal Appl. 2016;181:27. 10.1186/s13660-016-1110-4Search in Google Scholar

[14] Boulbrachene M. Finite element convergence analysis of Schwarz alternating method for nonlinear elliptic PDEs. SQUJS. 2019;24(2):109–21. 10.24200/squjs.vol24iss2pp109-121Search in Google Scholar

[15] Al Farei Q, Boulbrachene M. Mixing finite elements and finite differences in nonlinear Schwarz iterations for nonlinear elliptic PDEs. Comput Math Model. 2022;33(1):77–94. 10.1007/s10598-022-09558-xSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Al Farei Q, Boulbrachene M. L∞-Convergence analysis of a finite element linear Schwarz alternating method for a class of semi-linear elliptic PDEs. Int J Anal Appl. January 2023;21(71):1–28. 10.28924/2291-8639-21-2023-71Search in Google Scholar

[17] Ciarlet PG. Discrete maximum principle for finite-difference operators. Aequ Math. 1970;4(3):338–52. 10.1007/BF01844166Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ciarlet PG, Raviart PA. Maximum principle and uniform convergence for the finite element method. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 1973;2(1):17–31. 10.1016/0045-7825(73)90019-4Search in Google Scholar

[19] Lu C, Huang W, Qiu J. Maximum principle in linear finite element approximations of anisotropic diffusion-convection-reaction problems. Numer Math. 2014;127:515–37. 10.1007/s00211-013-0595-8Search in Google Scholar

[20] Nitsche J. L∞-convergence of finite element approximations. In Proceedings of the symposium on mathematical aspects of finite element methods. Lectures notes in mathematics. Springer; Vol. 606; 1977. pp. 261–74. 10.1007/BFb0064468Search in Google Scholar

[21] Pao CV. Nonlinear parabolic and elliptic equations. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. 10.1007/978-1-4615-3034-3Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hecht F. New development in freefem++. J Numer Math. 2012;20(3–4):251–65. 10.1515/jnum-2012-0013Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Focus on NLENG 2023 Volume 12 Issue 1

- Research Articles

- Seismic vulnerability signal analysis of low tower cable-stayed bridges method based on convolutional attention network

- Robust passivity-based nonlinear controller design for bilateral teleoperation system under variable time delay and variable load disturbance

- A physically consistent AI-based SPH emulator for computational fluid dynamics

- Asymmetrical novel hyperchaotic system with two exponential functions and an application to image encryption

- A novel framework for effective structural vulnerability assessment of tubular structures using machine learning algorithms (GA and ANN) for hybrid simulations

- Flow and irreversible mechanism of pure and hybridized non-Newtonian nanofluids through elastic surfaces with melting effects

- Stability analysis of the corruption dynamics under fractional-order interventions

- Solutions of certain initial-boundary value problems via a new extended Laplace transform

- Numerical solution of two-dimensional fractional differential equations using Laplace transform with residual power series method

- Fractional-order lead networks to avoid limit cycle in control loops with dead zone and plant servo system

- Modeling anomalous transport in fractal porous media: A study of fractional diffusion PDEs using numerical method

- Analysis of nonlinear dynamics of RC slabs under blast loads: A hybrid machine learning approach

- On theoretical and numerical analysis of fractal--fractional non-linear hybrid differential equations

- Traveling wave solutions, numerical solutions, and stability analysis of the (2+1) conformal time-fractional generalized q-deformed sinh-Gordon equation

- Influence of damage on large displacement buckling analysis of beams

- Approximate numerical procedures for the Navier–Stokes system through the generalized method of lines

- Mathematical analysis of a combustible viscoelastic material in a cylindrical channel taking into account induced electric field: A spectral approach

- A new operational matrix method to solve nonlinear fractional differential equations

- New solutions for the generalized q-deformed wave equation with q-translation symmetry

- Optimize the corrosion behaviour and mechanical properties of AISI 316 stainless steel under heat treatment and previous cold working

- Soliton dynamics of the KdV–mKdV equation using three distinct exact methods in nonlinear phenomena

- Investigation of the lubrication performance of a marine diesel engine crankshaft using a thermo-electrohydrodynamic model

- Modeling credit risk with mixed fractional Brownian motion: An application to barrier options

- Method of feature extraction of abnormal communication signal in network based on nonlinear technology

- An innovative binocular vision-based method for displacement measurement in membrane structures

- An analysis of exponential kernel fractional difference operator for delta positivity

- Novel analytic solutions of strain wave model in micro-structured solids

- Conditions for the existence of soliton solutions: An analysis of coefficients in the generalized Wu–Zhang system and generalized Sawada–Kotera model

- Scale-3 Haar wavelet-based method of fractal-fractional differential equations with power law kernel and exponential decay kernel

- Non-linear influences of track dynamic irregularities on vertical levelling loss of heavy-haul railway track geometry under cyclic loadings

- Fast analysis approach for instability problems of thin shells utilizing ANNs and a Bayesian regularization back-propagation algorithm

- Validity and error analysis of calculating matrix exponential function and vector product

- Optimizing execution time and cost while scheduling scientific workflow in edge data center with fault tolerance awareness

- Estimating the dynamics of the drinking epidemic model with control interventions: A sensitivity analysis

- Online and offline physical education quality assessment based on mobile edge computing

- Discovering optical solutions to a nonlinear Schrödinger equation and its bifurcation and chaos analysis

- New convolved Fibonacci collocation procedure for the Fitzhugh–Nagumo non-linear equation

- Study of weakly nonlinear double-diffusive magneto-convection with throughflow under concentration modulation

- Variable sampling time discrete sliding mode control for a flapping wing micro air vehicle using flapping frequency as the control input

- Error analysis of arbitrarily high-order stepping schemes for fractional integro-differential equations with weakly singular kernels

- Solitary and periodic pattern solutions for time-fractional generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation

- An unconditionally stable numerical scheme for solving nonlinear Fisher equation

- Effect of modulated boundary on heat and mass transport of Walter-B viscoelastic fluid saturated in porous medium

- Analysis of heat mass transfer in a squeezed Carreau nanofluid flow due to a sensor surface with variable thermal conductivity

- Navigating waves: Advancing ocean dynamics through the nonlinear Schrödinger equation

- Experimental and numerical investigations into torsional-flexural behaviours of railway composite sleepers and bearers

- Novel dynamics of the fractional KFG equation through the unified and unified solver schemes with stability and multistability analysis

- Analysis of the magnetohydrodynamic effects on non-Newtonian fluid flow in an inclined non-uniform channel under long-wavelength, low-Reynolds number conditions

- Convergence analysis of non-matching finite elements for a linear monotone additive Schwarz scheme for semi-linear elliptic problems

- Global well-posedness and exponential decay estimates for semilinear Newell–Whitehead–Segel equation

- Petrov-Galerkin method for small deflections in fourth-order beam equations in civil engineering

- Solution of third-order nonlinear integro-differential equations with parallel computing for intelligent IoT and wireless networks using the Haar wavelet method

- Mathematical modeling and computational analysis of hepatitis B virus transmission using the higher-order Galerkin scheme

- Mathematical model based on nonlinear differential equations and its control algorithm

- Bifurcation and chaos: Unraveling soliton solutions in a couple fractional-order nonlinear evolution equation

- Space–time variable-order carbon nanotube model using modified Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo derivative

- Minimal universal laser network model: Synchronization, extreme events, and multistability

- Valuation of forward start option with mean reverting stock model for uncertain markets

- Geometric nonlinear analysis based on the generalized displacement control method and orthogonal iteration

- Fuzzy neural network with backpropagation for fuzzy quadratic programming problems and portfolio optimization problems

- B-spline curve theory: An overview and applications in real life

- Nonlinearity modeling for online estimation of industrial cooling fan speed subject to model uncertainties and state-dependent measurement noise

- Quantitative analysis and modeling of ride sharing behavior based on internet of vehicles

- Review Article

- Bond performance of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with rebar under freeze–thaw environment: A review

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Convolutional neural network for UAV image processing and navigation in tree plantations based on deep learning”

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Improved nonlinear model predictive control with inequality constraints using particle filtering for nonlinear and highly coupled dynamical systems

- Anti-control of Hopf bifurcation for a chaotic system

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part I

- Addressing target loss and actuator saturation in visual servoing of multirotors: A nonrecursive augmented dynamics control approach

- Collaborative control of multi-manipulator systems in intelligent manufacturing based on event-triggered and adaptive strategy

- Greenhouse monitoring system integrating NB-IOT technology and a cloud service framework

- Special Issue: Unleashing the Power of AI and ML in Dynamical System Research

- Computational analysis of the Covid-19 model using the continuous Galerkin–Petrov scheme

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part I

- Research on the role of multi-sensor system information fusion in improving hardware control accuracy of intelligent system

- Advanced integration of IoT and AI algorithms for comprehensive smart meter data analysis in smart grids

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Focus on NLENG 2023 Volume 12 Issue 1

- Research Articles

- Seismic vulnerability signal analysis of low tower cable-stayed bridges method based on convolutional attention network

- Robust passivity-based nonlinear controller design for bilateral teleoperation system under variable time delay and variable load disturbance

- A physically consistent AI-based SPH emulator for computational fluid dynamics

- Asymmetrical novel hyperchaotic system with two exponential functions and an application to image encryption

- A novel framework for effective structural vulnerability assessment of tubular structures using machine learning algorithms (GA and ANN) for hybrid simulations

- Flow and irreversible mechanism of pure and hybridized non-Newtonian nanofluids through elastic surfaces with melting effects

- Stability analysis of the corruption dynamics under fractional-order interventions

- Solutions of certain initial-boundary value problems via a new extended Laplace transform

- Numerical solution of two-dimensional fractional differential equations using Laplace transform with residual power series method

- Fractional-order lead networks to avoid limit cycle in control loops with dead zone and plant servo system

- Modeling anomalous transport in fractal porous media: A study of fractional diffusion PDEs using numerical method

- Analysis of nonlinear dynamics of RC slabs under blast loads: A hybrid machine learning approach

- On theoretical and numerical analysis of fractal--fractional non-linear hybrid differential equations

- Traveling wave solutions, numerical solutions, and stability analysis of the (2+1) conformal time-fractional generalized q-deformed sinh-Gordon equation

- Influence of damage on large displacement buckling analysis of beams

- Approximate numerical procedures for the Navier–Stokes system through the generalized method of lines

- Mathematical analysis of a combustible viscoelastic material in a cylindrical channel taking into account induced electric field: A spectral approach

- A new operational matrix method to solve nonlinear fractional differential equations

- New solutions for the generalized q-deformed wave equation with q-translation symmetry

- Optimize the corrosion behaviour and mechanical properties of AISI 316 stainless steel under heat treatment and previous cold working

- Soliton dynamics of the KdV–mKdV equation using three distinct exact methods in nonlinear phenomena

- Investigation of the lubrication performance of a marine diesel engine crankshaft using a thermo-electrohydrodynamic model

- Modeling credit risk with mixed fractional Brownian motion: An application to barrier options

- Method of feature extraction of abnormal communication signal in network based on nonlinear technology

- An innovative binocular vision-based method for displacement measurement in membrane structures

- An analysis of exponential kernel fractional difference operator for delta positivity

- Novel analytic solutions of strain wave model in micro-structured solids

- Conditions for the existence of soliton solutions: An analysis of coefficients in the generalized Wu–Zhang system and generalized Sawada–Kotera model

- Scale-3 Haar wavelet-based method of fractal-fractional differential equations with power law kernel and exponential decay kernel

- Non-linear influences of track dynamic irregularities on vertical levelling loss of heavy-haul railway track geometry under cyclic loadings

- Fast analysis approach for instability problems of thin shells utilizing ANNs and a Bayesian regularization back-propagation algorithm

- Validity and error analysis of calculating matrix exponential function and vector product

- Optimizing execution time and cost while scheduling scientific workflow in edge data center with fault tolerance awareness

- Estimating the dynamics of the drinking epidemic model with control interventions: A sensitivity analysis

- Online and offline physical education quality assessment based on mobile edge computing

- Discovering optical solutions to a nonlinear Schrödinger equation and its bifurcation and chaos analysis

- New convolved Fibonacci collocation procedure for the Fitzhugh–Nagumo non-linear equation

- Study of weakly nonlinear double-diffusive magneto-convection with throughflow under concentration modulation

- Variable sampling time discrete sliding mode control for a flapping wing micro air vehicle using flapping frequency as the control input

- Error analysis of arbitrarily high-order stepping schemes for fractional integro-differential equations with weakly singular kernels

- Solitary and periodic pattern solutions for time-fractional generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation

- An unconditionally stable numerical scheme for solving nonlinear Fisher equation

- Effect of modulated boundary on heat and mass transport of Walter-B viscoelastic fluid saturated in porous medium

- Analysis of heat mass transfer in a squeezed Carreau nanofluid flow due to a sensor surface with variable thermal conductivity

- Navigating waves: Advancing ocean dynamics through the nonlinear Schrödinger equation

- Experimental and numerical investigations into torsional-flexural behaviours of railway composite sleepers and bearers

- Novel dynamics of the fractional KFG equation through the unified and unified solver schemes with stability and multistability analysis

- Analysis of the magnetohydrodynamic effects on non-Newtonian fluid flow in an inclined non-uniform channel under long-wavelength, low-Reynolds number conditions

- Convergence analysis of non-matching finite elements for a linear monotone additive Schwarz scheme for semi-linear elliptic problems

- Global well-posedness and exponential decay estimates for semilinear Newell–Whitehead–Segel equation

- Petrov-Galerkin method for small deflections in fourth-order beam equations in civil engineering

- Solution of third-order nonlinear integro-differential equations with parallel computing for intelligent IoT and wireless networks using the Haar wavelet method

- Mathematical modeling and computational analysis of hepatitis B virus transmission using the higher-order Galerkin scheme

- Mathematical model based on nonlinear differential equations and its control algorithm

- Bifurcation and chaos: Unraveling soliton solutions in a couple fractional-order nonlinear evolution equation

- Space–time variable-order carbon nanotube model using modified Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo derivative

- Minimal universal laser network model: Synchronization, extreme events, and multistability

- Valuation of forward start option with mean reverting stock model for uncertain markets

- Geometric nonlinear analysis based on the generalized displacement control method and orthogonal iteration

- Fuzzy neural network with backpropagation for fuzzy quadratic programming problems and portfolio optimization problems

- B-spline curve theory: An overview and applications in real life

- Nonlinearity modeling for online estimation of industrial cooling fan speed subject to model uncertainties and state-dependent measurement noise

- Quantitative analysis and modeling of ride sharing behavior based on internet of vehicles

- Review Article

- Bond performance of recycled coarse aggregate concrete with rebar under freeze–thaw environment: A review

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Convolutional neural network for UAV image processing and navigation in tree plantations based on deep learning”

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part II

- Improved nonlinear model predictive control with inequality constraints using particle filtering for nonlinear and highly coupled dynamical systems

- Anti-control of Hopf bifurcation for a chaotic system

- Special Issue: Decision and Control in Nonlinear Systems - Part I

- Addressing target loss and actuator saturation in visual servoing of multirotors: A nonrecursive augmented dynamics control approach

- Collaborative control of multi-manipulator systems in intelligent manufacturing based on event-triggered and adaptive strategy

- Greenhouse monitoring system integrating NB-IOT technology and a cloud service framework

- Special Issue: Unleashing the Power of AI and ML in Dynamical System Research

- Computational analysis of the Covid-19 model using the continuous Galerkin–Petrov scheme

- Special Issue: Nonlinear Analysis and Design of Communication Networks for IoT Applications - Part I

- Research on the role of multi-sensor system information fusion in improving hardware control accuracy of intelligent system

- Advanced integration of IoT and AI algorithms for comprehensive smart meter data analysis in smart grids