Abstract

This research focuses on implementing a robust passivity-based nonlinear control method for bilateral/teleoperation systems. The key challenge is addressing communication pathways between the master and slave, control delays, and load disturbances, which can lead to instability and reduced transparency. To tackle these issues, the proposed controller incorporates a second-order super-twisting sliding-mode observer to counteract communication and control delays. A sliding mode assist disturbance observer compensates for load torque variations. The approach aims to ensure stability and transparency by handling time-varying delays. The system model comprises two interconnected direct-drive motors, simulating robotic configurations without a physical robot. The nonlinear controller framework simplifies the complex bilateral control problem, significantly improving stability and transparency performance. Computer simulations with step and sinusoidal inputs demonstrate the effectiveness of the approach, providing a satisfactory level of accuracy and transparency between estimated and actual slave positions, even with varying delays and load variations. The research contributes to control engineering by offering a robust method to enhance bilateral system performance, ensuring stable and transparent communication between the master and slave, particularly suitable for real-time internet-based bilateral control systems.

1 Introduction

Teleoperation and bilateral control systems have garnered significant attention in various domains, such as telesurgery and telerobotics, due to their potential to enhance human life. However, communication delays play a crucial role in determining the performance of these systems. These delays occur when transmitting control commands to the slave side and relaying feedback signals from the slave to the master through the communication channel. Overcoming the effects of these delays is imperative for the success of internet-based teleoperation or bilateral control as they can lead to instability and a loss of transparency.

Bilateral control, which extends a person’s sensing capabilities to a remote environment, has recently become a focal point for advancements in robotics, control theory, micro-parts handling, and virtual reality systems. Teleoperation finds applications in network robotics, telesurgery, space, and seabed telemanipulation, micro-nano parts handling, inspection, and assembly [1–3].

In the current systems, real-time feedback to the remote operator is often lacking. To improve operator performance, transparent transfer of contact force information from the slave to the master is desirable, enabling a kinesthetic coupling between the operator and the environment. Communication delays are inevitable in networked systems and can lead to system instability and a loss of transparency in force reflection mechanisms.

In certain cases, robotic systems are operated using a haptic user interface in a semi-autonomous or manual manner. These systems consist of a master device as the operator interface and a slave device that replicates the master’s trajectory on various scales. Bilateral control is employed to control this unique structure. In bilateral control, the master-slave coupled interactive system ensures that the slave device tracks the position of the master device while transmitting the forces exerted on the slave device from the environment to the master device. A master device reproduces and scales the interaction forces occurring in the remote environment, providing the operator with a kinesthetic and tactile sense of the remote location. The force signals measured from the slave device in the environment drive the motors on the master device, allowing the production of the same forces and torques applied by the slave device to the environment. These forces and torques are fed back to the operator’s hand, completing the information transfer loop. Bilateral control systems involve the exchange of signals between the master and slave sides. One approach sends velocity reference information from the master to the slave, while force information from the slave is sent to the master. Another approach calculates the control input on the master side using feedback from the slave [4–6]. In bilateral control systems, two types of delays exist, namely, control delay, the delay in commands sent by the master and received by the slave, and measurement delay, referring to the delay in feedback signals from the slave to the master. The presence of time delays compromises transparency, defined as the master and slave’s ability to perceive and interact with the same environment simultaneously. Furthermore, communication delays can destabilize the system and limit the operational capabilities of the slave. If the slave encounters an unknown disturbance, the successive commands may prove ineffective, further destabilizing the system. Overcoming the detrimental effects of communication delay is crucial for enhancing the performance of internet-based teleoperation or bilateral control systems. The bilateral control problem encompasses multiple dimensions, including performance, stability, and robustness. Each application imposes specific constraints, such as time delay, the number of degrees of freedom (DOF), and environmental and safety requirements. Nonlinearities within the system pose additional challenges by potentially causing instability, limit cycles, and configuration or load perturbations. Moreover, fixed model parameters may become inaccurate due to these nonlinearities, necessitating confinement or compensation for uncertainties in the model parameters. Consequently, there is no universally optimal controller for teleoperation [7–9].

The transparency objective in bilateral systems, as measured by performance indices of force and position control, is affected by unpredictable communication delays. In classical bilateral control, force control and position control are independently designed. Hence, a comprehensive bilateral control scheme is established to integrate the master and slave devices. Bilateral-integrated systems with communication delays or variable time delays require real-time data transfer. Achieving a match between the operator’s perceived impedance and the environment’s exerted impedance on the slave side is critical.

The primary challenge lies in the fact that bilateral controllers struggle to simultaneously achieve transparency and stability due to uncertainties in the system and environment. The control problem can be formulated as follows: ensuring the position trajectories of the master and slave devices are identical while ensuring that the sum of forces acting on the slave and master is zero. However, most current systems fail to provide real-time feedback to the remote operator. Transparent transfer of contact force from the slave device to the master device is essential to bind the operator’s performance kinesthetically. Time delays heavily influence the system’s performance, destabilizing it and degrading its overall performance. Addressing time-varying or fluctuating time delays poses a significant challenge. To reproduce tactile sensations, bilateral control requires highly accurate and fast information flow. Numerous approaches have been proposed in the literature to address the issue of time delay [10,11]. Communication delays, especially in internet-based systems, pose challenges in bilateral control. Various methods have been studied to compensate for network delays, including wave variable transformation [12–14], impedance shaping [15,16], fuzzy logic [17], µ-synthesis [18], H∞-optimal control [19], and the Smith-predictor technique [20–23].

In recent years, various aspects of bilateral control have been explored in studies. These include PD controllers [24,25], L2 stability [26], multi-rate sampling [27,28], force control [29,30], transparency, and contact stability [31,32].

Time delay compensation also encompasses various techniques considering communication delay as a disturbance and utilizing a communication delay observer [33,34]. This approach outperforms the Smith-predictor method and is capable of handling variable delays. It employs a first-order observer with a cutoff frequency that determines system behavior. Moreover, it is independent of modeling errors. However, challenges remain, necessitating solutions for practical applications involving variable time delays, nonlinearities, and uncertainties [35,36].

The focus has been on single-master, multiple-slave telemanipulation, as well as master-slave control of multi-fingered humanoids based on finger-tip force feedback. Each of these approaches has distinct advantages and considerations based on specific control system requirements [37–39].

Sliding mode control (SMC) approaches consider time delays as disturbances and strive to achieve robustness in control systems. Various applications of SMC, including adaptive fuzzy control and equivalent control, have been successfully implemented. Disturbance observer methods, such as the sliding mode observer (SMO), effectively reduce constant delay and model mismatch issues. The advantages of SMCs in bilateral control systems are highlighted, including their robustness against uncertainties and disturbances, simplified control solutions, and stability improvement. However, a major concern arises from the chattering phenomenon, which can lead to undesirable control actions and mechanical wear. The chattering-free SMC techniques have been proposed to address this issue, but instability under time-delay conditions remains a critical concern, especially for short-time delays. Sensitivity to a model mismatch between the control model and the actual system is also an important consideration, which can limit the overall control performance. In the realm of SMOs, their ability to compensate for communication delays and model mismatch is a significant advantage. By estimating and compensating for delayed information, SMOs enable accurate state estimation and control action generation. However, instability issues can arise under specific time-delay conditions, particularly for short delays, which poses challenges in ensuring stable and reliable control performance. Additionally, the sensitivity to measurement noise is an important consideration that affects the accuracy of state estimation and, consequently, the control actions derived from the observer’s outputs. Designing and tuning the parameters of these techniques, selecting appropriate switching surfaces, and ensuring stability require expertise and meticulous analysis [40–51].

While model-based approaches, such as scattering variables and wave variables, have been utilized for time delay compensation in bilateral control systems, they have certain limitations: Scattering variables approach: Although this method ensures passivity, a notable drawback is the lack of transparency analysis. This lack of transparency makes it challenging to understand the relationships between the control inputs and outputs, hindering system analysis and design. Wave variables approach: Introducing damping for stability is a positive aspect of this method. However, conflicts between transparency and stability arise, requiring adaptive damping tuning to strike a balance. This tuning process adds complexity to the control system design and implementation [52–55].

The adoption of FPGA technology in bilateral control systems offers several advantages, including high-speed computation, parallel processing, accurate sampling periods, low power consumption, and compact size. However, it is crucial to consider the following aspects: Implementation complexity: Despite the benefits of FPGA technology, implementing FPGA-based solutions in bilateral control systems can be complex. It requires specialized expertise and knowledge of FPGA programming, which may pose challenges for researchers and practitioners. Hardware constraints: FPGA-based implementations are subject to hardware limitations, such as limited resources and computational capacity. These constraints may restrict the scalability and flexibility of the control system, potentially affecting its performance. Development and maintenance: Developing and maintaining FPGA-based bilateral control systems can be time-consuming and resource-intensive. The need for specialized hardware and software tools, as well as ongoing support and updates, can present logistical challenges [56,57].

The utilization of optimal control methods to achieve stability and meet performance requirements is a positive aspect of bilateral control systems. However, it is essential to consider the following factors: Computational complexity: Optimal control algorithms often involve complex mathematical computations and optimization techniques. Implementing these algorithms in real-time control systems may introduce computational overhead, potentially impacting the system’s response time and efficiency. Sensitivity to model accuracy: Optimal control methods heavily rely on accurate system models. Any discrepancies between the actual system and the model can significantly affect the control performance. Obtaining accurate system models can be challenging in practice, especially for complex systems with uncertainties and time-varying dynamics. Comparative quantitative and analytical evaluations of these methods can be found along with a comprehensive survey in refs [58–61].

Disturbance-observer-based methods effectively address measurement delays in motion control systems [62–66]. Nevertheless, despite achieving stabilization objectives, all the mentioned methods fall short of achieving full motion synchronization between separated systems due to the existing input channel delay.

Variable structure systems have been extensively explored [67,68], and an SMC was proposed by Leeraphan et al. [69] to achieve robust stabilization of uncertain input delay systems with nonlinear perturbations. However, this method may suffer from a loss of precision due to the direct use of past data for predicting future motion. A teleoperation system structure is based on Bayesian predictions [70], but their scheme only focuses on enhancing the current estimate of a system using posterior probabilities from past data, without considering the expected future motion.

In most cases, force is measured on both the master and slave sides. The utilization of a force observer is a challenging yet more suitable solution for our application. Modal decomposition [71] and advancements in acceleration control [72] have demonstrated the feasibility of transmitting environmental information.

This study delves into the challenges of dealing with internal uncertainties and external disturbances, specifically in internet-based robotic teleoperation systems that face time-varying delays. It highlights modeling uncertainties as a primary challenge in designing controls for robotic systems, especially when interacting with unknown remote environments. The study introduces a robust adaptive control methodology to enhance stability and performance, considering both model uncertainties and external disturbances. A comprehensive dynamic model of a teleoperation system is presented, and adaptive control is employed based on the maximum magnitude of disturbances. A smoothing filter is used to handle communication latencies and provide continuous approximations of delayed signals. It discusses challenges in multilateral teleoperation systems due to communication delays, particularly in systems with multiple communication channels. The research designs a control method based on synchronization errors for a system where two slave robots are commanded by a master system to work cooperatively. The stability and effectiveness of the proposed controller are validated through both theoretical Lyapunov analysis and real-world experiments on an internet-based double-slave teleoperation system [73–75].

This study presents significant advancements in position control performance by introducing two innovative master-slave system configurations. The primary focus is on compensating for communication and control delays within bilateral control systems. The first configuration incorporates a second-order super-twisting SMO on the master side to compensate for measurement and control delay, along with a model tracking controller (MTC) on the slave side to mitigate load uncertainties. A sliding-mode assist load torque estimation approach, which greatly contributes to the disturbance rejection performance of the controller, is validated through simulation results having various scenarios. On the master side, the primary control and feedback assessment takes place, whereas, on the slave side, load compensation is carried out.

The communication delay is treated as a control delay for delivering the control input to the slave and as a measurement delay for delivering the feedback signal to the master.

The study introduces a novel combination of methodologies to tackle the challenges faced by previous studies on network delay compensation.

The objective is to enhance communication and address load torque disturbance issues in the slave. Specifically, this study builds upon the combination of SMOs and a nonlinear controller approach to address variable delay and variable load issues encountered in previous studies.

Simulations were conducted to evaluate the proposed methodologies under various scenarios, including step and sinusoidal load and reference trajectories, considering random measurement and control input delays. The results demonstrate significant improvements in performance despite random delays and load variations.

The aim of this study is to satisfy two essential criteria: simplicity for intuitive understanding without extensive theoretical background and affordability and ease of integration into existing systems. Additionally, it addresses crucial teleoperation issues such as transparency and operationality. The utilization of force estimation proves advantageous.

Our proposed solution for this study combines the SMO theory and passivity-based nonlinear control theory. These concepts have demonstrated effectiveness in teleoperated systems and can be readily comprehended at an intuitive level, aligning with our objectives.

For future studies, the experimental setup can vary, ranging from simple linear motors with a single DOF to more complex mechanical structures. The choice of setup depends on the complexity of the specific problem targeted for investigation in a remote location.

The structure of the study is as follows: Section 2 formulates the bilateral teleoperation control problem. Section 3 presents the design of a second-order SMO to compensate for communication and control delays on the master side. Section 4 is based on the sliding mode assist disturbance observer (SMADO) to compensate for the load torque variations.

Section 5 constructs design principles and stability proof of a robust passivity-based bilateral teleoperation controller. Section 6 provides simulation results for different scenarios and parameter configurations. Finally, Section 7 concludes the study with a constructive discussion.

2 Conceptualization of the bilateral teleoperation control problem

When analyzing dynamical systems, it is crucial to account for the presence of unknown errors in the measurement channel. These errors can manifest as time delays, dynamical disturbances, and nonlinear gains, which may occur in different combinations. To address this, we can treat this combination as a block connected in series with the system’s output. Considering a basic second-order system, we observe the presence of nonlinearity and delays in both the input and output channels. Through the study of this system, we can establish a theoretical framework that can be extended to tackle control challenges in diverse types of nonlinear systems.

Our approach initiates by examining a simple second-order system to illustrate the underlying concepts. Subsequently, we explore how these ideas can be generalized to other scenarios. Furthermore, we investigate situations where nonlinearity and delay exist in the system’s input channel.

In this study, we analyze a system configuration that incorporates communication delays in both the control and feedback paths. Specifically, we consider a direct-drive robotic arm with one DOF, functioning as the slave component. To compensate for the load, we employ a SMADO. Additionally, we utilize a second-order SMO as a feedback block to address measurement delays. In the context of active exploration, tactile feedback, which involves mechanical interaction forces, holds significant importance. However, moderately complex robotic systems encounter challenges related to touch-based active exploration, including contact stability, force acquisition, and teleoperation of a remote robot [76–80].

The EOM of the master and slave dynamical systems are given in Eq. (1).

where

The equations of motion (EOM) of the measurement system are represented in Eq. (2).

where

The operator moves a master device and its angular velocity

The teleoperator dynamics defined in Eq. (1) can be reshaped in a compact form as shown in Eq. (3).

where

The master-slave coordinates are defined in a new position and force coordinates by utilizing modal decomposition [61,71].

The modified Hadamard of second-order

where

The new coordinate systems are accompanied by position and force errors and also indicate the virtual modal space of the bilateral teleoperation system [82–85].

The teleoperator dynamics are now constituted by the new coordinates as given in Eq. (5).

where

In systems with multi-DOFs, force control, and position tracking can be implemented using both common and differential modes. By evaluating these modes, valuable insights can be obtained regarding the performance of the control laws. This analysis allows us to gain a better understanding of how the control strategies perform in multi-DOF systems [86,87].

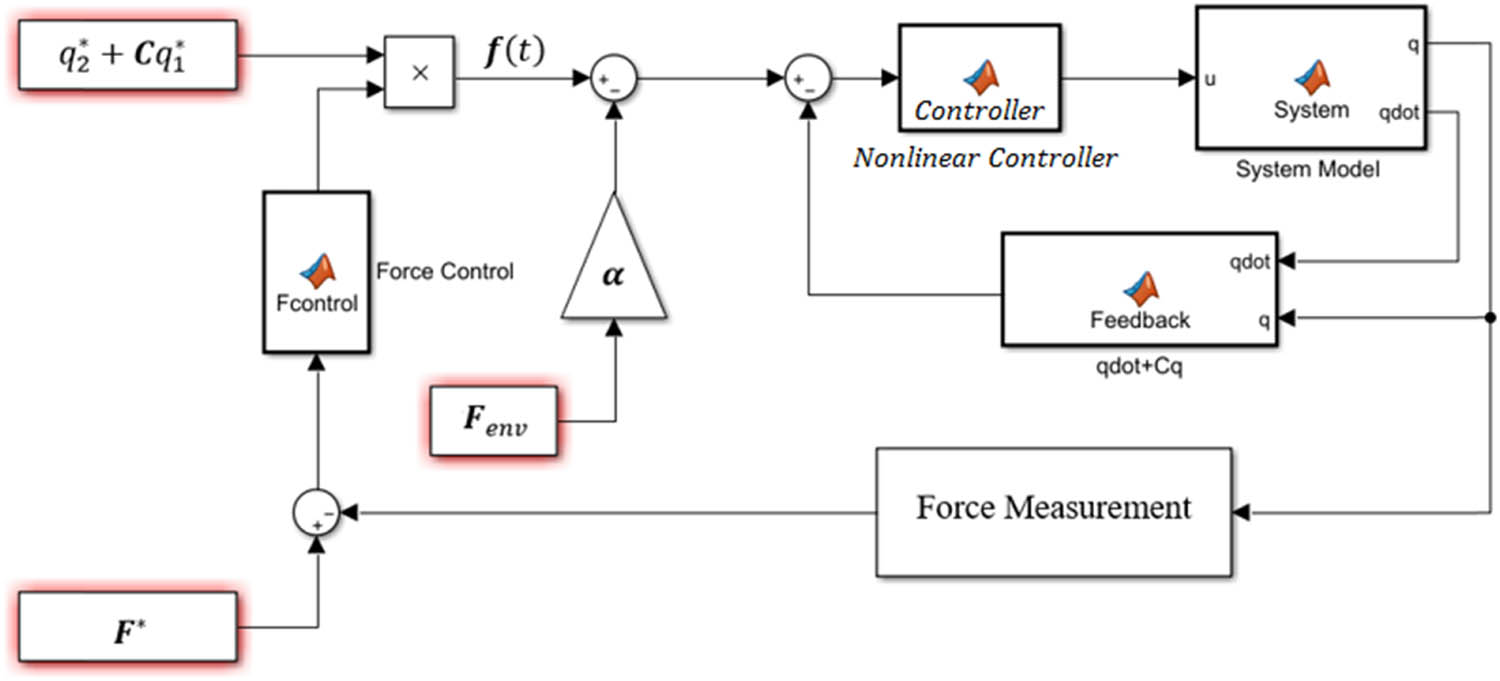

The structure of the scaled bilateral teleoperation system is depicted in Figure 1.

The structure of the scaled bilateral system.

The environmental force is formulated as in Eq. (6).

The information related to the task at the environment site is needed to assist a human operator in perception as they are a physical presence in the environment. The slave and master devices are dynamically decoupled.

The force, which is the reaction of the environment, is defined as a spring-damper effect. The expression of the

The motion of the master device is not constrained as long as the slave device is out of touch with an obstacle. Otherwise, the master side controls its torque to resist the motion.

The reference torque of the master device

Bilateral control is a control approach utilized in mechanical systems that require fully actuated motion control. In this setup, an operator operates a master device, and the velocity commands from the master device are transmitted in a scalable manner to the slave devices. Simultaneously, the reaction forces experienced by the slave devices in the environment are reflected by the human operator by applying a scaling factor. This bidirectional information exchange allows for synchronized and coordinated control between the operator and the slave devices, enabling tasks to be performed accurately and effectively [88–90].

In this study, position control and force control are realized in the robust passivity-based nonlinear controller framework. A fully actuated mechanical system, whose number of actuators is equal to the number of the primary masses can be modeled in compact form using the Euler-Lagrange formulation given in Eq. (7).

where

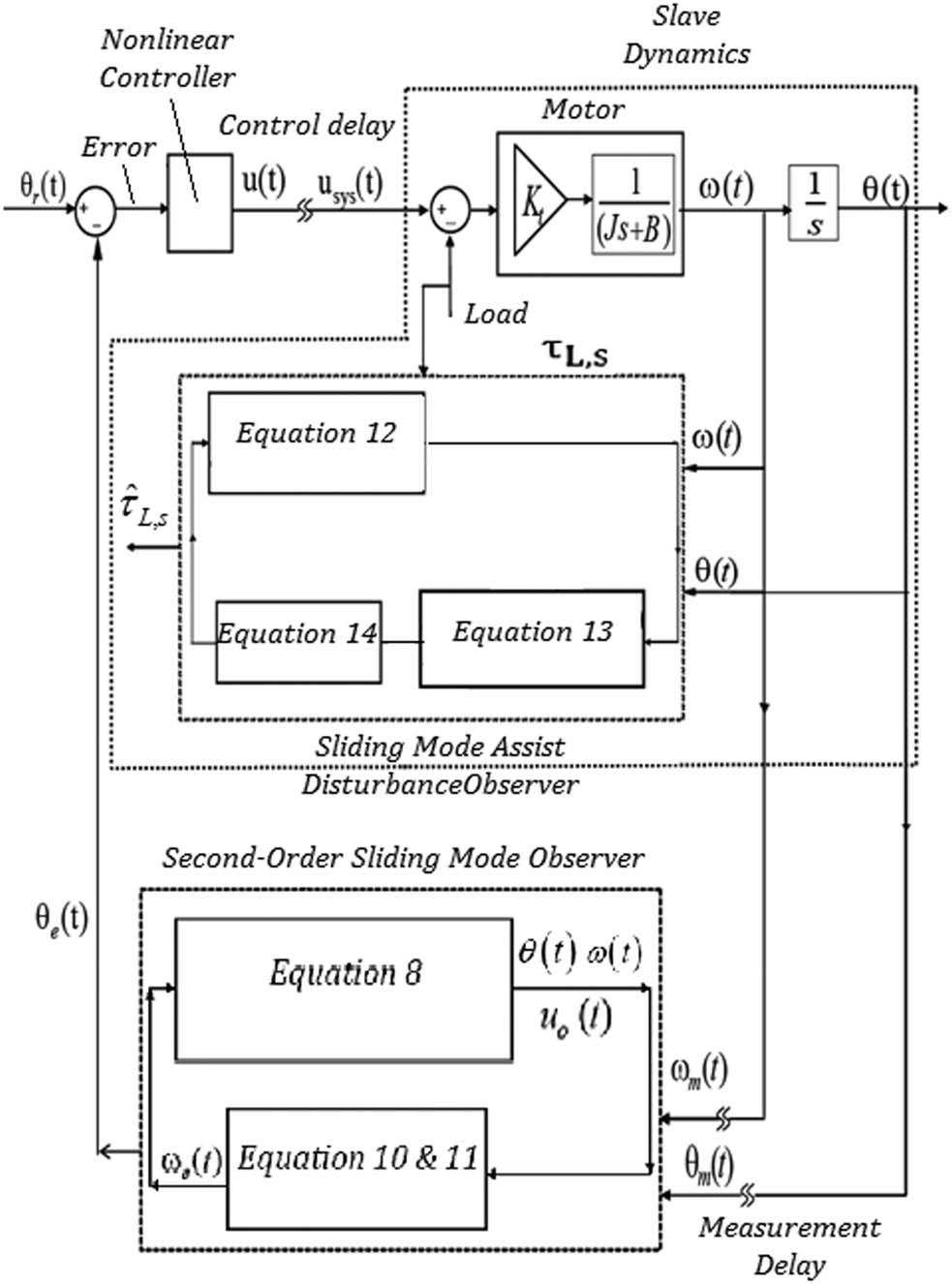

The structure of the motion control system is depicted in Figure 2.

The block diagram of the bilateral control system.

3 Design of second-order SMO

The measurement error can comprise various factors, such as time delay, dynamic disturbance, and nonlinear gain, possibly occurring together. As it occurs within the measurement channel, it can be considered as a block connected in series with the system output.

SMO is designed to estimate the precise position and velocity of the slave system, even in the presence of network delay within the feedback loop. By utilizing a delay regulator, the network delay is effectively treated as a constant value, contributing to the improved performance of the SMO compared to previous studies [93–96].

Furthermore, the proposed model integrated with the controller enhances the observer’s accuracy. The SMO employs a specific model that captures the dynamics of the system under observation. The SMO is a well-established control technique employed to estimate the state variables of a dynamic system. Its primary application lies in designing observers for systems characterized by uncertainties, disturbances, or unmeasured states.

The issue of the time delay will first be examined for a simple single DOF motion control system with nonlinearity and delay in the output channel described previously in Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively. System parameters are assumed known, and

The problem is to design a control input for the system that will ensure tracking of the reference position

The structure of the observer is chosen similar to that of the master-slave configuration as in Eq. (8).

where

The observer errors could be represented as in Eq. (9).

A second-order super-twisting SMO is designed as stated in Eq. (10) [97].

The efficiency of this strategy depends on the selection of the coefficients

For the second-order system, the convergence of estimated variables

Conditions on

By observing Eq. (11), we can deduce that the system eventually achieves convergence, meaning that the estimated position and velocity reach the actual position and velocity of the slave. However, as indicated in Eq. (10), the asymptotic convergence relies on having precise knowledge of

Figure 3 shows the block diagram of the observer system implemented in the bilateral control.

Block diagram of a slave system with a super twisting SMO compensating measurement delay.

4 SMADO-based load compensation

In this section, we present the design of the SMADO for the slave side to make up for the insufficiency of the disturbance estimation

The system model can be re-organized as in Eq. (12).

with state-space representation:

Here

Notice the dynamics, i.e.,

The error is defined as

The theoretical background of designing a disturbance observer is given in previous studies [100–103].

The design process of the SMADO is inspired by the papers [104–106].

First, define a sliding mode

Then,

where

For the system given in Eq. (12), if the condition

Proof

Define a positive-definite Lyapunov candidate as in Eq. (15).

Then, the time derivative of V(z) is evaluated as in Eq. (16).

If,

The switching gain

Using this function, the control law given in Eq. (14) is transformed into Eq. (18).

The small positive constant denoted as

This book offers an in-depth understanding of SMC, assisting in the exploration of convergence patterns and speeds. Additionally, it lays a foundational understanding of nonlinear controller behaviors, which is valuable for conversations about convergence speeds [107]. This book gives a detailed account of systems with time delays and can help in discussing the impact of these delays on controller performance [108]. The stability properties of time-delay systems were explored for the system’s performance under time-varying delays [109]. The convergence and behavior of controllers in the presence of time-varying delays are examined by Ryu et al. [110].

The block diagram of the system including the disturbance observer is shown in Figure 4.

Block diagram of the full control system with SM-based position and disturbance observers.

5 Robust passivity-based bilateral teleoperation controller design

The primary objective of the control problem is to develop a control input that guarantees the slave system’s output (

To tackle this problem, an estimation process is employed to determine the actual variables of the slave system, enabling the design of a control input based on these estimated values. This estimation process involves the design of an observer, which estimates the true position and velocity of the slave system despite the feedback loop delay. The observer’s output should accurately follow the measured values (

The proposed approach involves the application of MTC in the slave control system. By forcing the slave system to track a desired slave model, the MTC-based control system achieves disturbance rejection in the presence of uncertainties related to parameters and loads [111,112].

It is important to note that the feedback used in the master system originates from the output of the slave “model,” not the actual slave system. This integrated master-slave system employs the model’s output. This approach significantly enhances the tracking performance of the master-slave system and allows for the separate design of the master and slave controllers [113–116].

The primary goal of the super-twisting SMO design is to accurately estimate the slave position, which experiences a delay before being transmitted to the master. The SMAO is employed to estimate load changes. The proposed controller scheme is based on robust passivity-based control theory, where the estimated states are fed back to the RPB controller.

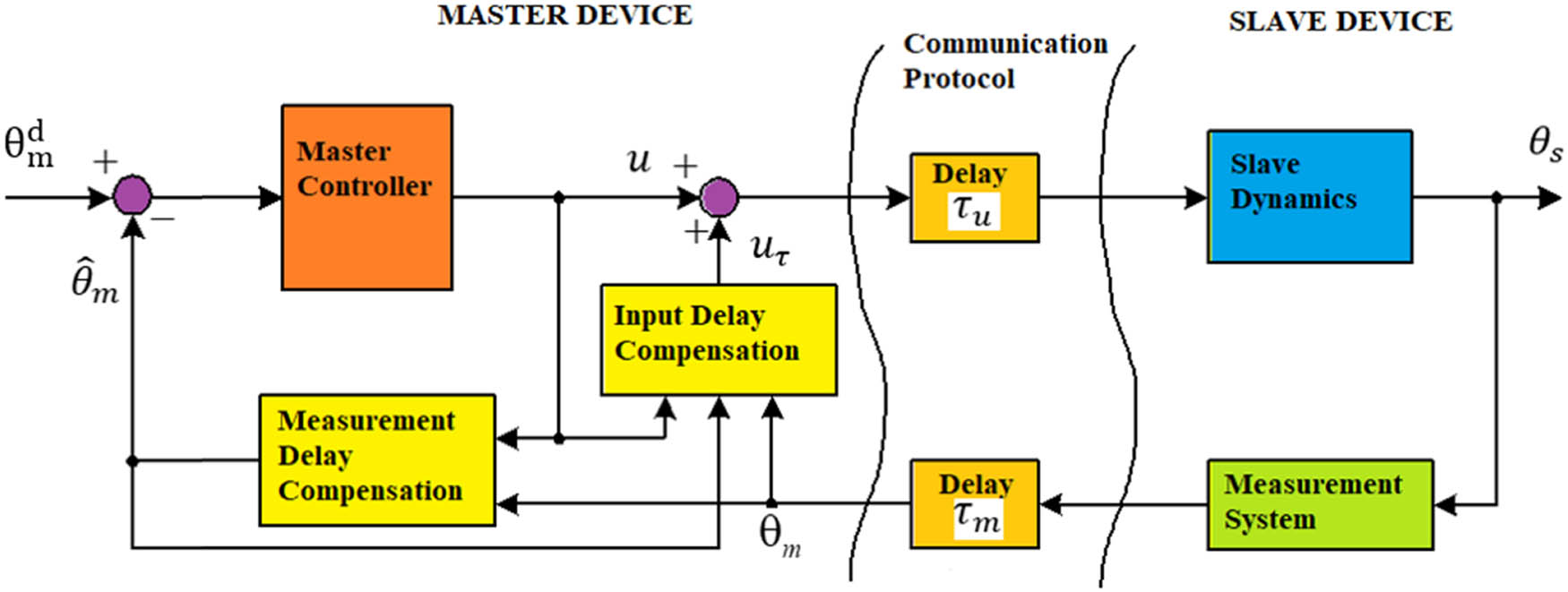

The general block diagram of the observer and controller developed for the compensation of the measurement and control input delay is demonstrated in Figure 5.

Block diagram of the observer and controller for the compensation of the measurement and control input communication delay.

The estimated position and velocity of the slave ultimately converge to their actual values. However, achieving asymptotic convergence is contingent upon having precise knowledge of the system parameters [117,118]. For the theoretical background of the passivity-based control, it can be consulted in previous literature [119–122].

The tracking errors for the position and velocity are defined in Eq. (19).

where

The dynamic model for the generalized robot slave manipulator is considered as in Eq. (20).

where

To construct the control law, it is assumed that only the structure of the model is known, but that the parameters are uncertain, and that the parametric uncertainties are bounded.

The control input is chosen as in Eq. (21) [123,124].

where the variables

where

The control law is rewritten in terms of linear parameterization of the robot dynamics and it becomes as in Eq. (22) [125].

The term

The combination of Eqs. (21) and (22) results in Eq. (23).

where

The system becomes as in Eq. (24).

where

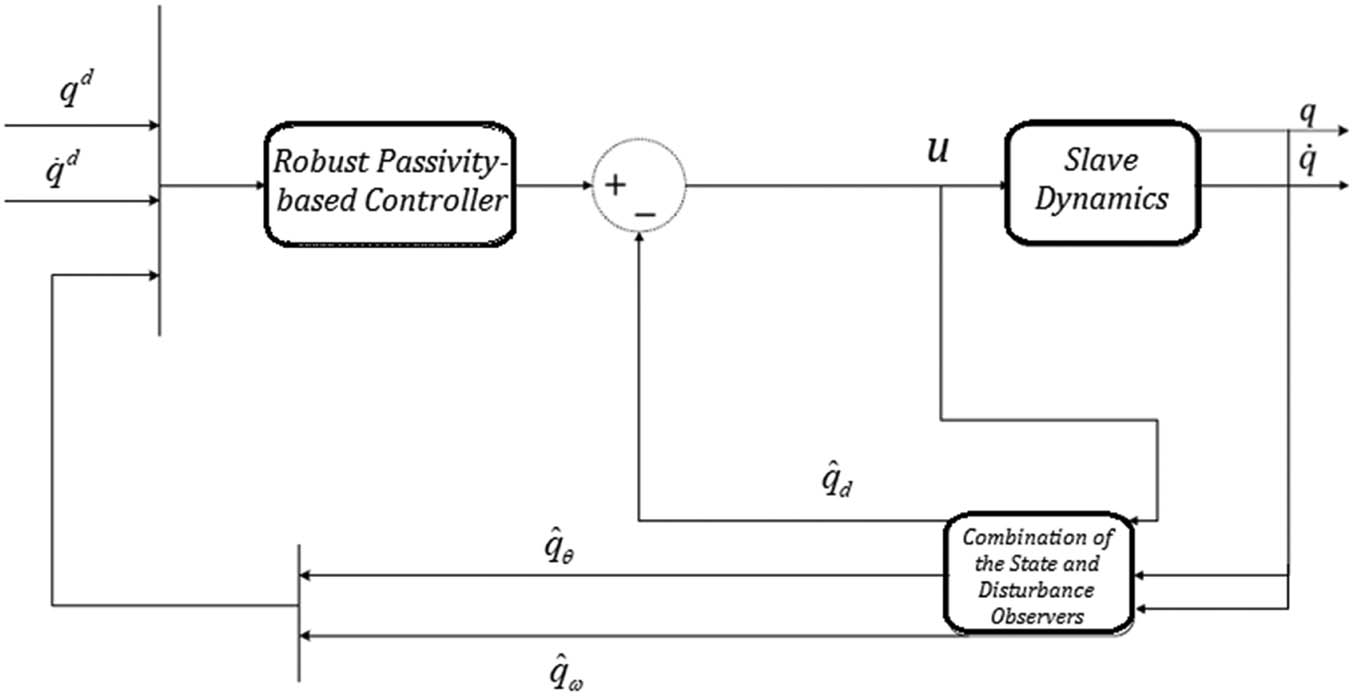

Figure 6 demonstrates the block diagram of the proposed control scheme for a 1-DOF model.

Robust passivity-based control scheme.

Stability proof: Assume that the following Lyapunov function candidate is chosen as in Eq. (25).

Evaluating the derivative of the

Using the skew-symmetry property and the definition of

where

When we design a robust passivity-based controller, its ability to handle changes in parameters and disturbances depends on the uncertainty bounds. If we set higher uncertainty bounds, the controller may exhibit better robustness in dealing with variations; however, it can lead to a phenomenon called “chattering,” which refers to rapid and excessive oscillations in the control signal.

To address chattering, we can introduce dead zones in the parameter perturbation term. Dead zones are ranges of values where no control action is taken, allowing for a smoother response. By increasing the dead-zone values, we can minimize chattering, but this comes at the cost of reduced tracking accuracy, meaning the controller may not precisely follow the desired reference signal.

In practical implementation, we can initially set the dead-zone values to high levels. We then progressively decrease these values until we achieve the desired tracking performance while continuing chattering within an acceptable range. This iterative process allows us to strike a balance between control accuracy and the presence of chattering, ensuring satisfactory performance of the passivity-based controller [126–128].

6 Simulation results

In this section, we present the outcomes of simulations that were conducted to study the effects of different combinations of control and communication delay, parameter variations, and load variations.

The term “constant delay” refers to a fixed delay of 1 s, while “random delay” represents a delay that fluctuates between 1 and 2 s. To emulate the time delay between France and the USA using the UDP/IP internet protocol [129], we have applied a random delay in our simulations.

The system under investigation is tested with two types of input signals: step and sinusoidal. We assess the system’s performance under conditions of constant load (step input) and varying load (sinusoidal input).

Additionally, a crucial factor affecting the system’s performance in real-world scenarios is parameter uncertainties. To simulate this realistic condition, we assume that certain values are unknown in some of our simulations.

All simulations are conducted using Matlab/Simulink as the software environment. We utilize the “ode23s” solver, which is specifically designed for solving stiff ordinary differential equations with the modified Rosenbrock method. Furthermore, we set the maximum step size to 1 × 10−5, indicating the maximum interval for numerical integration within the simulations.

Table 1 gives the values of the parameters used for the simulations.

List of the parameters used for simulations

| Parameter name | Parameter value | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

|

4,237 (

|

Torque constant |

|

|

0.23 (

|

Effective inertia |

|

|

0.0718 (

|

Effective viscous friction |

The parameters are selected based on the following information [130–133].

The torque constant for servo motors can range from 0.01 to 10 Nm/A, depending on the specific motor and its intended use. These ranges are approximate and can vary based on the motor’s design, size, and intended application. The effective inertia and effective viscous damping coefficient of servo motors can vary depending on the motor size, design, and intended application. Here are some general ranges for effective inertia and effective viscous damping coefficient in servo motors:

Effective inertia:

Small servo motors: 0.001–0.1 kg m2

Medium servo motors: 0.1–1 kg m2

Large servo motors: 1–10 kg m2

The effective inertia of a servo motor is influenced by factors such as rotor mass, mechanical components, and motor size. Lower inertia values indicate faster response times and better acceleration capabilities.

Effective viscous friction:

Small servo motors: 0.001–0.1 Nm s/rad

Medium servo motors: 0.1–1 Nm s/rad

Large servo motors: 1–10 Nm s/rad

The effective viscous friction represents the resistance to motion within the servo motor. Higher damping coefficients indicate more resistance to motion and can affect the motor’s response and stability.

6.1 Results for step reference input (under both control and measurement delay + load disturbance)

In this subsection, we explore different simulation scenarios with varying combinations of load and delay conditions.

The first scenario involves a constant load with a constant delay, where the communication and control delays between components remain fixed at 1 s.

Figure 7 depicts the system’s behavior when subjected to a constant measurement and control delay, with a constant load.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under constant load, a constant measurement, and control delay (1 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

In Figure 7a, we can observe the trajectories of various variables. The reference input for the angular position is the desired value the system aims to achieve; the controlled angular position output indicates the actual position of the system as influenced by the control algorithm; the estimated angular position represents the system’s internal estimate of its current position; measured angular position displays the actual position captured by the measurement device.

Moving on to Figure 7b, it illustrates the trajectories of the angular speed output. The controlled angular speed indicates the speed at which the system is rotating based on the control algorithm. The estimated angular speed represents the system’s internal estimation of its current rotational speed. The measured angular speed represents the actual rotational speed captured by the measurement device.

In Figure 7c, we focus on the control and estimation errors associated with the angular position. The plot shows the control error, which is the difference between the reference input and the controlled angular position output. This error indicates how well the system’s control algorithm is tracking the desired position.

The output of the slave and the estimated value of the output coincide with each other. This indicates that the system exhibits perfect transparency, even in the presence of time delay.

The second scenario considers a constant load but introduces a random delay. Here the disturbance signal remains constant, but the delay between components fluctuates between 1 and 2 s randomly.

Figure 8 depicts the system’s behavior when subjected to a random measurement and control delay, with a constant load. Figure 8a presents trajectories of various variables (desired angular position, actual controlled position, estimated angular position, and measured angular position). Figure 8b illustrates the trajectories of angular speed variables (controlled angular speed, estimated angular speed, and measured angular speed). In Figure 8c, the focus shifts to control and estimation errors associated with the angular position.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under constant load, random measurement, and control delay (1–2 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

The slave output and the estimated output mostly align with each other. The variations observed in both the slave and measured output are primarily attributed to random measurement delays.

In the third scenario, we introduce a variable load, which implies that the input signal to the system changes over time in Figure 9. The variable load is in sinusoidal waveform and has 1 rad/s angular frequency. Despite the varying load, the delay between components remains constant at 1 s. When we apply this variable load to the slave component of the system, there is a possibility that the system may become unstable. This instability arises due to the dynamic interaction between the load variations and the system’s response [134,135].

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under variable sinusoidal load, constant measurement, and control delay (1 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

To address this issue and maintain the desired second-order behavior of the system, adjustments are made to the parameters of the robust passivity-based controller. The goal is to compensate for the effects of the load variations and ensure stability in the system. However, it is important to note that this controller is effective only when the load is accurately known. Since it is often challenging to precisely estimate and compensate for an unknown and varying load, a disturbance observer is introduced on the load side. This observer helps in estimating and compensating for the effects of the load variations, even when the specific details of the load are unknown. By employing the disturbance observer, the system can better handle and mitigate the uncertainties and fluctuations associated with the varying load, thereby improving its stability and performance.

Finally, the fourth scenario combines both a variable load and a random delay in Figure 10. The load signal varies over time (sinusoidal), and the delay between components fluctuates randomly between 1 and 2 s.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under variable sinusoidal load, random measurement, and control delay (1–2 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

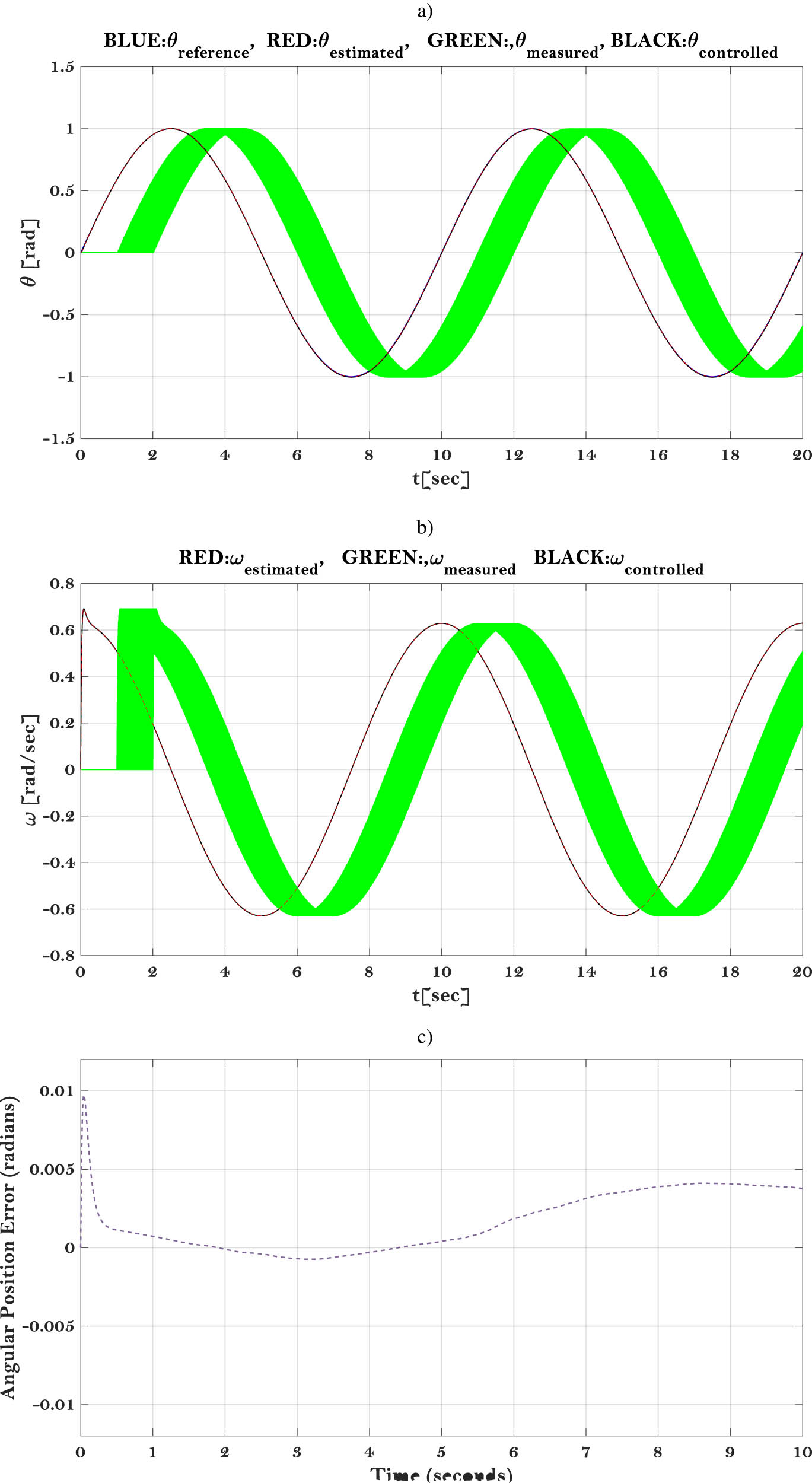

6.2 Results for sinusoidal reference input (under both control and measurement delay + load disturbance)

This analysis focuses on evaluating the system’s performance when subjected to a sinusoidal input signal. The sinusoidal input signal used in these scenarios has a frequency of 0.1 Hz, meaning it completes one full cycle every 10 s.

In the first scenario, a constant load is applied to the system, meaning the load signal remains steady over time in Figure 11. Additionally, the delay between components remains constant throughout the simulation.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under constant load, constant measurement, and control delay (1 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

The reference, the slave output, and the estimated output all overlap despite the constant load, as expected from a transparent system.

In the second scenario, a constant load is still applied to the system, but now the delay between components varies randomly in Figure 12. This means that the delay fluctuates between different values during the simulation.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under constant load, random measurement, and control delay (1–2 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

The third scenario given in Figure 13 introduces a variable load to the system. This means that the input signal, which is a sinusoidal wave, changes over time. The variable load is in sinusoidal waveform and has 1 rad/s angular frequency. However, the delay between components remains constant throughout the simulation.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under variable load, constant measurement, and control delay (1 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

Finally, in the fourth scenario depicted in Figure 14, both a variable load and random delay are introduced to the system. This means that the load signal, a sinusoidal wave, varies over time, while the delay between components fluctuates randomly.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, and (c) position error between the reference input and system output (under variable load, random measurement, and control delay (1–2 s) with robust passivity-based controller + super twisting SMO + SMAO).

Based on the plots presented above, we can observe that the computer simulations have yielded positive outcomes for both constant and random measurement delays when dealing with step-type and sinusoidal reference inputs.

Furthermore, utilizing the current controller-observer scheme, the simulations have demonstrated successful compensation for constant and random delays in the control input channel, even in the presence of constant and random measurement delays. Indeed, despite the presence of time delay, the system maintains perfect transparency. This is made possible because the observer accurately estimates the actual position of the slave, given that the slave model and load are precisely known in this particular scenario.

Drawing insights from the aforementioned results, it becomes evident that the system needs to possess the ability to reject local disturbances. This capability is essential for maintaining the system’s stability and performance, especially in real-world scenarios where disturbances can affect its operation.

By analyzing the system’s performance in these different scenarios, we can gain insights into how it responds to changes in the load, delay, and parameter variations when driven by a sinusoidal input signal. This information is valuable for evaluating the system’s stability, robustness, and overall performance.

6.3 Results under parameter changes (effective inertia and effective viscous friction)

In this section, we examine and discuss the performance of the system when subjected to parameter changes. It is important to note that achieving identical estimation and actual models is crucial for accurate estimation using the SMO. While this may be feasible in simulations, it is not expected to be easily attainable or possible in practical scenarios.

For instance, certain parameters of the plant or controlled system, such as inertia (J) and viscous friction (B), may not be known with high accuracy or could vary under different environmental and load conditions. To evaluate the system’s robustness against parameter changes, we modify the actual model parameters to values of 2.5*

While in simulations, it has been relatively straightforward to align the estimator model with the actual model, achieving this level of accuracy or alignment is challenging in practical applications. This is due to uncertainties in parameters like inertia and friction, which can vary in real-world scenarios based on environmental and load conditions.

To demonstrate the system’s robustness against parameter changes, we present the results in Figures 15 and 16. In Figure 15, the simulations are conducted under the following conditions: step reference input, random time delays in both measurement and control channels, and a variable sinusoidal load.

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, (c) angular position error, and (d) load torque estimation error. Step reference input, random control delay, measurement delay (1–2 s), variable sinusoidal load with 2.5 times effective viscous friction (B) and 2.5 times effective inertia (J).

(a) Angular position trajectories, (b) angular speed trajectories, (c) angular position error, and (d) load torque estimation error. Sinusoidal reference input, random control delay, measurement delay (1–2 s), variable sinusoidal load with 2.5 times effective viscous friction (B) and 2.5 times effective inertia (J).

Similarly, in Figure 16, the simulations are performed with a sinusoidal reference input, random time delays in both measurement and control channels, and a variable sinusoidal load.

The results demonstrate that the system effectively compensates for the load, allowing it to maintain its desired second-order behavior. The measured and estimated outputs closely track the slave output as the load is being compensated. The plots indicate that the SMAO provides accurate estimations of the applied load. Additionally, the disturbance observer successfully compensates for the variations in the load.

Upon analyzing the figures, it is evident that the system’s performance is satisfactory across most of the tested conditions. Notably, the estimation errors are negligible or even zero for each case, indicating the high accuracy of the observers in estimating the system’s behavior. Furthermore, the system can compensate for the load effectively, whether it remains constant or varies over time. These findings highlight the robustness of the designed observers and the overall system.

By gaining these insights into the system’s performance under varying conditions and parameter changes, we can conclude that the system demonstrates stability and satisfactory operation. This information is valuable for assessing the system’s reliability and its suitability for real-world control engineering applications.

7 Conclusion

We conducted computer simulations to assess the performance of a proposed approach, which includes a robust passivity-based controller, a sliding mode-based state observer, and a SMADO. The evaluation focused on a 1-DOF robotic arm operating through bilateral teleoperation.

The simulations revealed a satisfactory level of accuracy and transparency in estimating the position of the slave compared to its actual position. The nonlinear controller effectively maintained stability throughout the operation.

The approach demonstrated effectiveness in handling both constant and random delays in measurement and control, as well as step-type and sinusoidal-type variations on the slave side. These encouraging results encourage the adoption of this approach for internet-based bilateral control systems.

The developed observers successfully compensated for random delays in measurement and control, as well as unknown loads on the slave. However, when there were changes in parameters, such as variations in inertia and friction, the system’s performance deteriorated. This underscores the necessity for additional estimation methods in the observers, which will be addressed in future research endeavors. The high-performance tracking control achieved under significant uncertainties and disturbances contributes to the improvement of the SM-based state and disturbance observers and nonlinear controller combination.

This study offers a state-of-the-art solution to the time delay problem, contributing to the field of interactive dynamical systems and enhancing the functionality of bilateral control systems. The outcomes of this research can enable practical applications of bilateral control in various domains, including network robotics, telesurgery, space, and underwater telemanipulation, and micro-nano parts handling.

-

Funding information: The author states no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: The author accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Hashtrudi-Zaad K, Salcudean SE. Bilateral parallel force/position teleoperation control. International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; 1999 Nov 14–19; Nashvillee (TN), USA. ASME, 1999. p. 351–8. 10.1115/imece1999-0046.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Hokayem PF, Spong MW. Bilateral teleoperation: An historical survey. Automatica. 2006;42(12):2035–57. 10.1016/j.automatica.2006.06.027.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Varkonyi TA, Rudas IJ, Pausits P, Haidegger T. Survey on the control of time delay teleoperation systems. IEEE 18th International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems INES 2014. 2014 Jul 3–5; Tihany, Hungary. IEEE, 2014. p. 89–94. 10.1109/ines.2014.6909347.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Chen Z, Pan Y-J, Gu J. A novel adaptive robust control architecture for bilateral teleoperation systems under time-varying delays. Int J Robust Nonlinear Control. 2014;25(17):3349–66. 10.1002/rnc.3267.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Mahapatra S, Zefran M. Stable haptic interaction with switched virtual environments. 2003 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.03CH37422); 2003 Sep 14–19; Taipei, Taiwan. IEEE, 2003. p. 1241–6. 10.1109/robot.2003.1241762.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Niemeyer G, Slotine J-JE. Stable adaptive teleoperation. American Control Conference; 1990 May 23–25; San Diego (CA), USA. IEEE, 2009. p. 1186–91. 10.23919/acc.1990.4790931.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Niemeyer G, Slotine J-JE. Towards force-reflecting teleoperation over the internet. Proceedings. 1998 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.98CH36146); 1998 May 20; Leuven, Belgium. IEEE, 2002. p. 1909–15. 10.1109/robot.1998.680592.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Tsuji T, Natori K, Nishi H, Ohnishi K. A controller design method of bilateral control system. EPE J. 2006;16(2):22–8. 10.1080/09398368.2006.11463616.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Shen S, Song A. Bilateral motion prediction and tracking control for nonlinear teleoperation system with time-varying delays. 2019 19th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS); 2019 Oct 15–18; Jeju, South Korea. IEEE, 2020. p. 798–803. 10.23919/iccas47443.2019.8971489.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Speich JE, Shao L, Goldfarb M. An experimental hand/ARM model for human interaction with a Telemanipulation system. International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition; 2001 Nov 11–16; New York (NY), USA. ASME, 2001. p. 941–6. 10.1115/imece2001/dsc-24617.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yashiro D, Yakoh T, Ohnishi K. End-to-end flow control using Pi Controller for Force Control System over TCP/IP Network. 2009 7th IEEE International Conference on Industrial Informatics; 2009 Jun 23–26; Cardiff, UK. IEEE, 2009. p. 194–9. 10.1109/indin.2009.5195802.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Niemeyer G, Slotine J-JE. Using wave variables for system analysis and Robot Control. Proceedings of International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 1997 Apr 25; Albuquerque (NM), USA. IEEE, 2002. p. 1619–25. 10.1109/robot.1997.614372.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ching H, Book WJ. Human evaluation of internet-based bilateral teleoperation using wave variables with adaptive predictor and direct drift control. International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exhibition; 2006 Nov 5–10; Chicago (IL), USA. p. 1355–64. 10.1115/imece2006-14721.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Chen Z, Huang F, Song W, Zhu S. A novel wave-variable based time-delay compensated four-channel control design for multilateral teleoperation system. IEEE Access. 2018;6:25506–16. 10.1109/access.2018.2829601.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Colgate JE. Robust impedance shaping via bilateral manipulation. American Control Conference; 1991 Jun 26–28; Boston (MA), USA. IEEE, 2009. p. 3070–1. 10.23919/acc.1991.4791971.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Kaneko K, Tokashiki H, Tanie K, Komoriya K. Impedance shaping based on force feedback bilateral control in macro-micro teleoperation system. Proceedings of International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 1997 Apr 25; Albuquerque (NM), USA. IEEE, 2002. p. 710–7. 10.1109/robot.1997.620119.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Shao H, Nonami K. Bilateral control of Tele‐Hand System with neuro‐fuzzy scheme. Ind Robot: An Int J. 2006;33(3):216–27. 10.1108/01439910610659123.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Leung GMH, Francis BA, Apkarian J. Bilateral Controller for teleoperators with time delay via μ-synthesis. IEEE Trans Robot Autom. 1995;11(1):105–16. 10.1109/70.345941.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Sename O, Fattouh A, Robust H∞ control of bilateral teleoperation systems under communication time-delay. In: Chiasson J, Loiseau JJ, editors. Applications of Time Delay Systems, vol. 352. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2007. p. 99–116. 10.1007/978-3-540-49556-7_6.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Smith AC, van Hashtrudi-Zaad K. Neural network-based teleoperation using smith predictors. In: IEEE International Conference Mechatronics and Automation; 2005 Jul 29–Aug 1; Niagara Falls (ON), Canada. IEEE, 2006. 1654–9. 10.1109/icma.2005.1626803.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Du F, Du W. A novel smith predictor for wireless networked control systems with uncertainty. International Conference on Environmental Science and Information Application Technology; 2009 Jul 4–5; Wuhan, China. IEEE, 2009, p. 552–5. 10.1109/esiat.2009.526.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zennir Y, Larabi MS, Benzaroual H. New Smith Predictor Controller Design for time delay system. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics; 2017 Jul 26–28; Madrid, Spain. ICINCO, 2017. p. 598–605. 10.5220/0006426105980605.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Lai C-L, Hsu P-L, Wang B-C. Design of the Adaptive Smith predictor for the time-varying network control system. SICE Annual Conference; 2008 Aug 20–22; Chofu, Japan. IEEE, 2008. p. 2933–8. 10.1109/sice.2008.4655165.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Slawiński E, Mut V. Pd-like controller for delayed bilateral teleoperation of a manipulator robots. Int J Robust Nonlinear Control. 2014;25(12):1801–15. 10.1002/rnc.3177.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Cruz EE, Liu Y. Stable PD position/force control in bilateral teleoperation. 2018 15th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computing Science and Automatic Control (CCE); 2018 Sep 5–8; Mexico City, Mexico. IEEE, 2018. p. 1–6. 10.1109/iceee.2018.8533964.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Tumerdem U, Demir M. L2 stable transparency optimized two channel teleoperation under time delay. IECON 2015 – 41st Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2015 Nov 9–12; Yokohama, Japan. IEEE, 2016. 001313–20. 10.1109/iecon.2015.7392282.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Wang Z, Sun H. A bandwidth allocation strategy based on multirate sampling method in networked control system. In: Xing S, Chen S, Wei Z, Xia J, editors. Unifying Electrical Engineering and Electronics Engineering. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol. 238. New York (NY), USA: Springer; 2013. p. 1455–65. 10.1007/978-1-4614-4981-2_159.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Yashiro D, Ohnishi K. Multirate sampling method for bilateral control with communication bandwidth constraint. 2009 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology; 2009 Feb 10–13; Churchill (VIC), Australia. IEEE, 2009. p. 1–6. 10.1109/icit.2009.4939532.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Katsura S, Matsumoto Y, Ohnishi K. Analysis and experimental validation of force bandwidth for force control. IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology; 2003 Dec 10–12; Maribor, Slovenia. IEEE, 2004. p. 796–801. 10.1109/icit.2003.1290759.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Ruwanthika RM, Katsura S. Precise slave-side force control for security enhancement of bilateral motion control during application of excessive force by operator. Precision Eng. 2020;65:7–22. 10.1016/j.precisioneng.2020.04.015.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Lawrence DA. Stability and transparency in bilateral teleoperation. Proceedings of the 31st IEEE Conference on Decision and Control; 1992 Dec 16–18; Tucson (AZ), USA. IEEE, 2002. p. 2649–55. 10.1109/cdc.1992.371336.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ni L, Wang DWL. Contact transition stability analysis for a bilateral teleoperation system. Proceedings 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat No02CH37292). 2002 May 11–15; Washington DC, USA IEEE, 2002. p. 3272–7. 10.1109/robot.2002.1013731.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Arai S, Miyake K, Miyoshi T, Terashima K. Bilateral tele-control using multi-fingered humanoid robot with communication delay. 2008 SICE Annual Conference; 2008 Aug 20–22; Chofu, Japan. IEEE, 2008. p. 711–5. 10.1109/sice.2008.4654748.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Gadamsetty B, Bogosyan S, Gokasan M, Sabanovic A. Sliding mode and EKF observers for communication delay compensation in bilateral control systems. IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics; 2010 Jul 4–7; Bari, Italy. IEEE, 2010. p. 328–33. 10.1109/isie.2010.5637699.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Gadamsetty B, Bogosyan S, Gokasan M, Sabanovic A. Novel observers for compensation of communication delay in bilateral control systems. 2009 35th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics; 2009 Nov 3–5; Porto, Portugal. IEEE, 2010. p. 3019–26. 10.1109/iecon.2009.5415276.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Kawada H, Namerikawa T. Bilateral control of nonlinear teleoperation with time varying communication delays. 2008 American Control Conference; 2008 Jun 11–13; Seattle (WA), USA. IEEE, 2008. p. 189–94. 10.1109/acc.2008.4586489.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Sakaino S, Sato T, Ohnishi K. Precise position/force hybrid control with modal mass decoupling and bilateral communication between different structures. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2011;7(2):266–76. 10.1109/tii.2011.2121077.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Anderson RJ, Spong MW. Asymptotic stability for force reflecting teleoperators with time delays. Proceedings, 1989 International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 1989 May 14–19; Scottsdale (AZ), USA. IEEE, 2002. p. 1618–25. 10.1109/robot.1989.100209.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Zhang C, Wang H. Task-space adaptive control of bilateral teleoperators with time-varying delay. 2020 39th Chinese Control Conference (CCC); 2020 Jul 27–29; Shenyang, China. IEEE, 2020. p. 4586–91. 10.23919/ccc50068.2020.9188978.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Shen W, Gu J, Feng Z. A stable tele-robotic neurosurgical system based on SMC. 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO); 2007 Dec 15–18; Sanya, China. IEEE, 2008. p. 150–5. 10.1109/robio.2007.4522151.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Chiang C-C, Lan H-C. Model reference sliding mode control for uncertain underactuated systems with time delay. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE); 2018 Jul 8–13; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. IEEE, 2018. p. 1–8. 10.1109/fuzz-ieee.2018.8491468.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Roh Y-H, Oh J-H. Robust stabilization of uncertain input-delay systems by sliding mode control with delay compensation. Automatica. 1999;35(11):1861–5. 10.1016/s0005-1098(99)00106-5.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Priya PS, Bandyopadhyay B. Periodic output feedback based discrete-time sliding mode control of uncertain linear systems with input delay. 2013 International Mutli-Conference on Automation, Computing, Communication, Control and Compressed Sensing (iMac4s); 2013 Mar 22–23; Kottayam, India. IEEE, 2013. p. 111–6. 10.1109/imac4s.2013.6526392.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Yu X, Han Q, Li X, Wang C. Time-delay effect on equivalent control based single-input sliding mode control systems. 2008 International Workshop on Variable Structure Systems; 2008 Jun 8–10; Antalya, Turkey. IEEE, 2008. p. 13–7. 10.1109/vss.2008.4570675.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Hung L-C, Wang C-Y, Chung H-Y. Sliding mode control for uncertain time-delay systems with sector nonlinearities via Fuzzy Rule. 2005 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics; 2005 Oct 12; Waikoloa (HI), USA. IEEE, 2006. p. 251–6. 10.1109/icsmc.2005.1571154.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Lau JY, Liang W, Liaw HC, Tan KK. Sliding mode disturbance observer-based motion control for a piezoelectric actuator-based surgical device. Asian J Control. 2018;20(3):1194–203. 10.1002/asjc.1649.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Hace A, Jezernik K. Bilateral teleoperation by sliding mode control and reaction force observer. 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics; 2010 Jul 4–7; Bari, Italy. IEEE, 2010. p. 1809–16. 10.1109/isie.2010.5637717.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Hace A, Franc M. Sliding mode control for robotic teleoperation system with a haptic interface. ETFA2011; 2011 Sep 5–9; Toulouse, France. IEEE, 2011. p. 1–8. 10.1109/etfa.2011.6059087.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Sabanovic A, Elitas M. SMC based bilateral control. 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics; 2007 Jun 4–7; Vigo, Spain. IEEE, 2007. p. 2144–9. 10.1109/isie.2007.4374940.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Sabanovic A, Elitas M, Ohnishi K. Sliding modes in constrained systems control. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2008;55(9):3332–9. 10.1109/tie.2008.928112.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Garcia-Valdovinos LG, Parra-Vega V, Arteaga M. Observer-based higher-order sliding mode impedance control of bilateral teleoperation under constant unknown time delay. 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2006 Oct 9–15; Beijing, China. IEEE, 2007. p. 1692–9. 10.1109/iros.2006.282126.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Hatanaka T, Chopra N, Fujita M, Spong MW. Scattering variables-based control of bilateral teleoperators. In: Passivity-Based Control and Estimation in Networked Robotics. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 51–70. 10.1007/978-3-319-15171-7_3.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Chen Y, Xi N, Li H. Passive scattering transform bilateral teleoperation for an internet-based Mobile Robot. 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO); 2012 Dec 11–14; Guangzhou, China. IEEE, 2013. p. 643–8. 10.1109/robio.2012.6491039.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Munir S, Book WJ. Wave-based teleoperation with prediction. Proceedings of the 2001 American Control Conference(Cat. No.01CH37148); 2001 Jun 25–27; Arlington (VA), USA. IEEE, 2002. p. 4605–11. 10.1109/acc.2001.945706.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Ching H, Book WJ. Internet-based bilateral teleoperation based on wave variable with semi-adaptive predictor and direct drift control. International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition; 2005 Nov 5–11; Orlando (FL), USA. ASME, 2005. p. 1523–32. 10.1115/imece2005-81112.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Shao X, Sun D. Development of an FPGA-based motion control ASIC for robotic manipulators. 2006 6th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation; 2006 Jun 21–23; Dalian, China. IEEE, 2006. p. 8221–5. 10.1109/wcica.2006.1713577.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Galvan S, Botturi D, Fiorini P. FPGA-based controller for haptic devices. 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2006 Oct 9–15; Beijing, China. IEEE, 2007. p. 971–6. 10.1109/iros.2006.281776.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Lee S, Lee HS. Design of optimal time delayed teleoperator control system. Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 1994 May 8–13; San Diego (CA), USA. IEEE, 2002. p. 3252–8. 10.1109/robot.1994.351070.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Nam DP, Vu TA, Dinh Thiem T, Thiet NH. Optimal control for bilateral teleoperation system with variational method. 2016 International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (BME-HUST); 2016 Oct 5–6; Hanoi, Vietnam. IEEE, 2016. p. 130–6. 10.1109/bme-hust.2016.7782107.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Touzaline A. Optimal control of a bilateral contact with friction. Appl Math. 2022;49(1):21–34. 10.4064/am2405-4-2021.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Motoi N, Kubo R, Shimono T, Ohnishi K. Bilateral control with different inertia based on modal decomposition. 2010 11th IEEE International Workshop on Advanced Motion Control (AMC); 2010 Mar 21–24; Nagaoka, Japan. IEEE, 2010. p. 697–702. 10.1109/amc.2010.5464046.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Natori K, Tsuji T, Ohnishi K. Time delay compensation by communication disturbance observer in bilateral teleoperation systems. 9th IEEE International Workshop on Advanced Motion Control; 2006 Mar 27–29; Istanbul, Turkey. IEEE, 2006. p. 218–23. 10.1109/amc.2006.1631661.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Natori K, Ohnishi K. A design method of communication disturbance observer for time delay compensation. IECON 2006 - 32nd Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics; 2006 Nov 6–10; Paris, France. IEEE, 2007. p. 730–5. 10.1109/iecon.2006.347769.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Natori K, Oboe R, Ohnishi K. Stability Analysis and practical design procedure of time delayed control systems with Communication Disturbance Observer. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2008;4(3):185–97. 10.1109/tii.2008.2002705.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Tian D, Yashiro D, Ohnishi K. Channel characteristic and stability condition of communication disturbance observer based bilateral teleoperation with time delay. IECON 2010 - 36th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2010 Nov 7–10; Glendale (AZ), USA. IEEE 2010. p. 1246–51. 10.1109/iecon.2010.5675548.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Suzuki A, Ohnishi K. Performance conditioning of time delayed bilateral teleoperation system by scaling down compensation value of communication disturbance observer. 2010 11th IEEE International Workshop on Advanced Motion Control (AMC); 2010 Mar 21–24; Nagaoka, Japan. IEEE, 2010. p. 524–9. 10.1109/amc.2010.5464075.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Park JH, Cho HC. Sliding-mode controller for bilateral teleoperation with varying time delay. 1999 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (Cat. No.99TH8399); 1999 Sep 19–23; Atlanta (GA), USA. IEEE, 2002. p. 311–6. 10.1109/aim.1999.803184.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Zhang C, Lee Y, Chong KT. Passive teleoperation control with varying time delay. 9th IEEE International Workshop on Advanced Motion Control; 2006 Mar 27–29; Istanbul, Turkey. IEEE, 2006. p. 23–8. 10.1109/amc.2006.1631626.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Leeraphan S, Maneewarn T, Laowattana D. Stable adaptive bilateral control of transparent teleoperation through time-varying delay. IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and System; 2002 Sep 30–Oct 4; Lausanne, Switzerland. IEEE, 2002. p. 2979–84. 10.1109/irds.2002.1041725.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Lee JY, Payandeh S. Stability of internet-based teleoperation systems using Bayesian predictions. 2011 IEEE World Haptics Conference; 2011 Jun 21–24; Istanbul, Turkey. IEEE, 2011. p. 499–504. 10.1109/whc.2011.5945536.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Shimamoto K, Ohno Y, Nozaki T, Ohnishi K. Time delay compensation for tendon-driven bilateral control using modal decomposition and communication disturbance observer. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2014 Feb 26–Mar 1; Busan, South Korea. IEEE, 2014. p. 29–34. 10.1109/icit.2014.6894967.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Tanaka H, Ohnishi K, Nishi H. Implementation of multirate acceleration control based bilateral control system including mode transformation on FPGA. 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics; 2008 Nov 10–13; Orlando (FL), USA. IEEE 2009. p. 2465–70. 10.1109/iecon.2008.4758343.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Kebria PM, Khosravi A, Nahavandi S. Stable neural adaptive filters for teleoperations with uncertain delays. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2021;6(4):8663–70. 10.1109/lra.2021.3114965.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Kebria PM, Nahavandi D, Jafar Jalali SM, Khosravi A, Nahavandi S, Bello F, et al. Robust collaboration of a haptically-enabled double-slave teleoperation system under random communication delays. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC); 2020 Oct 11–14; Toronto (ON), Canada. IEEE, 2020. p. 2919–24. 10.1109/smc42975.2020.9283353.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Kebria PM, Khosravi A, Nahavandi S, Watters D, Guest G, Shi P. Robust adaptive control of internet-based bilateral teleoperation systems with time-varying delay and model uncertainties. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2019 Feb 13–15; Melbourne (VIC), Australia. IEEE, 2019. p. 187–92. 10.1109/icit.2019.8755182.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Natori K, Tsuji T, Ohnishi K, Hace A, Jezernik K. Robust bilateral control with internet communication. In: 30th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, 2004. IECON 2004; 2004 Nov 2–6; Busan, South Korea. IEEE, 2005. p. 2321–6.10.1109/iecon.2004.1432162.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Sano A, Fujimoto H, Tanaka M. Gain-scheduled compensation for time delay of bilateral teleoperation systems. Proceedings. 1998 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.98CH36146); 1998 May 20; Leuven, Belgium. IEEE, 2002. p. 1916–23. 10.1109/robot.1998.680593.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Natori K, Ohnishi K. Time delay compensation in bilateral teleoperation systems. 2006 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics; 2006 Jul 3–5; Budapest, Hungary. IEEE, 2006. p. 601–6. 10.1109/icmech.2006.252594.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Martins EC, Jota FG. Design of networked control systems with explicit compensation for time-delay variations. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part C (Applications and Reviews). 2010;40(3):308–18. 10.1109/tsmcc.2009.2036149.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Nuño E, Arteaga-Pérez M, Espinosa-Pérez G. Control of bilateral teleoperators with time delays using only position measurements. Int J Robust Nonlinear Control. 2017;28(3):808–24. 10.1002/rnc.3903.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Tsuji T, Ohnishi K. Position/force scaling of function-based bilateral control system. 2004 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology; 2004 Dec 8–10; Hammamet, Tunisia. IEEE, 2005. p. 96–101. IEEE ICIT ’04. 2004. 10.1109/icit.2004.1490264.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Tsumaki Y, Uchiyama M. A model-based space teleoperation system with robustness against modeling errors. Proceedings of International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 1997 Apr 25; Albuquerque (NM), USA. IEEE 2002. p. 1594–9. 10.1109/robot.1997.614368.Search in Google Scholar

[83] Slama T, De Rossi N, Trevisani A, Aubry D, Oboe R. Stability experiments of a scaled bilateral teleoperation system over internet using a model predictive controller. 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics; 2007 Jun 4–7; Vigo, Spain. IEEE, 2007. p. 3150–6. 10.1109/isie.2007.4375119.Search in Google Scholar

[84] Tsuji T, Nishi H, Ohnishi K. A controller design method of Decentralized Control System. IEEJ Trans Ind Appl. 2006;126(5):630–8. 10.1541/ieejias.126.630.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Yokokohji Y, Yoshikawa T. Bilateral control of master-slave manipulators for ideal kinesthetic coupling-formulation and experiment. Proceedings 1992 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 1992 May 12–14; Nice, France. IEEE, 2002. p. 849–58. 10.1109/robot.1992.220189.Search in Google Scholar

[86] Murakami T, Yu F, Ohnishi K. Torque sensorless control in multidegree-of-freedom manipulator. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 1993;40(2):259–65. 10.1109/41.222648.Search in Google Scholar

[87] Labrecque PD, Gosselin C. Performance optimization of a multi-DOF bilateral robot force amplification using complementary stability. 2015 IEEE Conference on Control Applications (CCA); 2015 Sep 21–23; Sydney (NSW), Australia. IEEE, 2015. p. 519–26. 10.1109/cca.2015.7320682.Search in Google Scholar

[88] Nguyen PTA, Arimoto S. Performance of pinching motions of two multi-DOF robotic fingers with soft-tips. Proceedings 2001 ICRA. IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.01CH37164); 2001 May 21–26; Seoul, South Korea. IEEE, 2003. p. 2344–9. 10.1109/robot.2001.932972.Search in Google Scholar

[89] Cho HC, Park JH. Stable bilateral teleoperation under a time delay using a robust impedance control. Mechatronics. 2005;15(5):611–25. 10.1016/j.mechatronics.2004.05.006.Search in Google Scholar

[90] Hua C, Yang Y, Liu XP. Adaptive position tracking control for bilateral teleoperation with constant time delay. Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation; 2012 Jul 6–8; Beijing, China. IEEE, 2012. p. 2324–8. 10.1109/wcica.2012.6358262.Search in Google Scholar

[91] Li PY, Wang M. Passivity based nonlinear control of hydraulic actuators based on an Euler-Lagrange formulation. ASME 2011 Dynamic Systems and Control Conference and Bath/ASME Symposium on Fluid Power and Motion Control; 2011 Oct 31-Nov 2; Arlington (VA), USA. ASME, 2011. p. 107–14. 10.1115/dscc2011-6197.Search in Google Scholar

[92] Yu H, Antsaklis PJ. Passivity-based output synchronization of networked Euler-Lagrange systems subject to nonholonomic constraints. Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference; 2010 Jun 30–Jul 2; Baltimore (MD), USA. IEEE, 2010. p. 208–13. 10.1109/acc.2010.5530541.Search in Google Scholar

[93] Garcia-Valdovinos LG, Parra-Vega V, Arteaga MA. Higher-order sliding mode impedance bilateral teleoperation with robust state estimation under constant unknown time delay. Proceedings, 2005 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics; 2005 Jul 24–28; Monterey (CA), USA. IEEE, 2005. p. 1293–8. 10.1109/aim.2005.1511189.Search in Google Scholar

[94] Saglam CO, Baran EA, Nergiz AO, Sabanovic A. Model following control with discrete time SMC for time-delayed bilateral control systems. 2011 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics; 2011 Apr 13–15; Istanbul, Turkey. IEEE, 2011. p. 997–1002. 10.1109/icmech.2011.5971262.Search in Google Scholar

[95] González N, Salas-Peña O, de León-Morales J, Rosales S, Parra-Vega V. Observer-based integral sliding mode approach for bilateral teleoperation with unknown time delay. Automatika. 2016;57(3):749–60. 10.7305/automatika.2017.02.1399.Search in Google Scholar

[96] Liu Q, Cai Z, Chen J, Jiang B. Observer-based integral sliding mode control of nonlinear systems with application to single-link flexible joint robotics. Complex Eng Syst. 2021;1:8. 10.20517/ces.2021.05.Search in Google Scholar

[97] Solvar S, Ghanes M, Amet L, Barbot J-P, Santome G. Industrial application of a second order sliding mode observer for speed and flux estimation in sensorless induction motor. In: Araújo RE, editor. Induction Motors – Modelling and Control. InTech; 2012. 10.5772/52910.Search in Google Scholar

[98] Zhao Y, Li K, Hua C. Adaptive sliding mode observer-based force feedback control for nonlinear bilateral teleoperators. 2018 IEEE 8th Annual International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER); 2018 Jul 19–23; Tianjin, China. IEEE, 2019. p. 158–63. 10.1109/cyber.2018.8688263.Search in Google Scholar

[99] Salgado I, Chairez I, Moreno J, Fridman L, Poznyak A. Generalized super-twisting observer for nonlinear systems. IFAC Proc Vol. 2011;44(1):14353–8. 10.3182/20110828-6-it-1002.03665.Search in Google Scholar

[100] Sariyildiz E, Oboe R, Ohnishi K. Disturbance observer-based robust control and its applications: 35th anniversary overview. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2020;67(3):2042–53. 10.1109/tie.2019.2903752.Search in Google Scholar

[101] Sariyildiz E. A guide to design disturbance observer-based motion control systems in discrete-time domain. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics (ICM); 2021 Mar 7–9; Kashiwa, Japan. IEEE, 2021. p. 1–6. 10.1109/icm46511.2021.9385674.Search in Google Scholar