Abstract

Bauxite reaction residue (BRR) produced from the poly-aluminum chloride (PAC) coagulant industry is a solid acidic waste that is harmful to environment. A low temperature synthesis route to convert the waste into water glass was reported. Silica dissolution process was systematically studied, including the thermodynamic analysis and the influence of calcium and aluminum on the leaching of amorphous silica. Simulation studies have shown that calcium and aluminum combine with silicon to form hydrated calcium silicate, silica–alumina gel, and zeolite, respectively, thereby hindering the leaching of silica. Maximizing the removal of calcium, aluminum, and chlorine can effectively improve the leaching of silicon in the subsequent process, and corresponding element removal rates are 42.81%, 44.15%, and 96.94%, respectively. The removed material is not randomly discarded and is reused to prepare PAC. The silica extraction rate reached 81.45% under optimal conditions (NaOH; 3 mol L−1, L S−1; 5/1, 75°C, 2 h), and sodium silicate modulus (nSiO2:nNa2O) is 1.11. The results indicated that a large amount of silica was existed in amorphous form. Precipitated silica was obtained by acidifying sodium silicate solution at optimal pH 7.0. Moreover, sodium silicate (1.11) further synthesizes sodium silicate (modulus 3.27) by adding precipitated silica at 75°C.

1 Introduction

Poly-aluminum chloride (PAC) is the most widely used inorganic polymer coagulant for water treatment because of its high adsorption activity, wider pH working range (pH 5–9), no need to add auxiliary agent, and a lower sensitivity to low water temperature [1,2,3]. Well known, some technologies for preparing PAC have been developed, such as electrolysis, thermal decomposition, and acid/alkaline dissolution method [4,5]. In general, an acceptable national synthesis method involves a two-step method where the bauxite, hydrochloric acid, and calcium aluminate were used as raw materials to prepare liquid PAC [6,7]. In China, PAC was also produced based on this process. However, this method results in the production of a large number of acid residues, known as “bauxite reaction residues (BRRs)” [8]. Annual output of PAC from bauxite is 982,100 tons. Approximately 150 kg of BRR are produced per ton liquid PAC produced [9]. BRR is growing at a rate of approximately 147,300 tons per year.

BRR is a viscous substance with strong acidity and corrosiveness. This feature will lead to high processing costs and even difficult to handle. Long time, those solid wastes were disposed by stacking in many enterprises. For a long time, many enterprises treat the solid waste through stacking. A considerable amount of waste has not only restricted the development of the PAC industry, but also caused serious environmental problems [10]. However, from another perspective, BRR is also a potential raw material for some industries such as ceramic materials, adsorbent, sodium silicate, valuable metal recovery, and building materials [11,12,13]. Among of them, sodium silicate (its aqueous solution is commonly known as water glass) is an important chemical product and also the main raw material for other silica-containing products [14]. Well known, sodium silicate is widely used as anti-corrosion materials, binders, refractory materials, white carbon black, acid-resistant cement, impregnants, fixing agents and molecular sieve catalysts, and other fields, covering almost all aspects of human life [15,16,17,18]. Therefore, sodium silicate is the most extensively used industrial raw material after acids and bases [19].

However, the current industrial production method of sodium silicate requires a huge energy input, that is, fusing sodium carbonate and high quality quartz sand at temperatures 1,300°C or 1,600°C [20]. Therefore, the synthesis of sodium silicate and precipitated silica from rich silica residue (or slag, industrial solid waste) is being intensively explored. In the literature, the recovery of silica from different wastes such as coal combustion ashes, biomass bottom ash, and rice husk ash has been reported [21,22,23]. Moreover, Shim et al. reported that waste corn stalks are used as raw materials, roasted at 700°C, and then leached with sodium hydroxide to prepare liquid sodium silicate [24]. Alam et al. reported that municipal waste incineration bottom ash was studied to synthesize sodium silicate and ordered mesoporous silica at low temperature [25]. Above studies have all achieved the alkali leaching silica extraction from silica-rich slag, but the modulus and concentration of liquid sodium silicate obtained are far lower than the industry standard, which is extremely unfavorable for subsequent utilization. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is only one report on the hydrothermal preparation of high modulus liquid sodium silicate (3.0–3.8) using precipitated silica from silica sand, which produced in the titanium dioxide pigment manufacturing process [26]. However, there are few reports on the preparation of high-modulus sodium silicate by extracting silica from BRR. However, there is limited number of studies on the preparation of high modulus sodium silicate by extracting silica from BRR. The mineral composition that accompanies the changes in this process is not well understood. In addition, from an economic and environmental point of view, if silica can be extracted from BRR and further synthesized high modulus sodium silicate at low temperature, it will greatly promote the utilization of BRR.

Based on the previous work [9], the aim of the present study was to extract precipitated silica from BRR and further synthesize high-modulus sodium silicate at low temperature. First, the acid leaching pretreatment of BRR was carried out to reduce the influence of other elements on the extraction of silica. Usually, most reports only focus on the extraction of valuable metals from waste and rarely care about the reuse of leachate (pre-treat solution). However, in this study the extract solution was reused to prepare PAC. The obtained acid leaching residue (acid leaching BRR, ALBRR) is a potential raw material for preparing silicon-containing products. The silica dissolution from ALBRR was studied by varying the liquid-to-solid ratio, leaching time, temperature, and sodium hydroxide concentration to ascertain the optimal conditions and understand dissolution process. Meanwhile, the corresponding reaction thermodynamics are calculated. Finally, sodium silicate solution (the liquid obtained by the above alkaline leaching process) is used to prepare precipitated silicon and further synthesize high-modulus liquid sodium silicate at normal pressure. The process has the advantages of low reaction temperature, low energy consumption, simple equipment, and no waste liquid discharge. The whole process can minimize the residue, that is, reduce the residue amount of BRR to below 35%.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Material and analysis

BRR used as the feedstock was collected from the bauxite manufacturing process of PAC in Gongyi City, Henan Province. The collected BRR has approximately 32.89 wt% moisture content. 37 vol% hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide pellets, and concentrated sulfuric acid (98 wt%) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, The Netherlands. All the chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and used as received without any further purification.

Table 1 presents the overall bulk chemical composition of BRR, indicating that silica and aluminum are the main components of the solid waste. In addition, BRR contains a series of potentially leachable elements: Ti, Fe, and Ca. The high content Cl− is the main reason for BRR becoming acidic waste [27], and its content is as high as 11.75 wt%.

Chemical composition of bauxite reaction residue

| Element | O | Si | Al | Ti | Ca | Fe | Cl | Mg | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | 35.11 | 18.13 | 15.13 | 4.39 | 6.35 | 5.47 | 11.75 | 0.63 | 3.02 |

2.2 Experimental procedure

2.2.1 Aluminum recycling to prepare PAC

An acid leaching treatment of BRR was performed to extract valuable metals while reducing the influence of other substances on the extraction of silica. BRR leaching experiment was carried out in a 2.5 L three-necked flask with electric heating mantle [27]. First, RR was mixed with 8 mol L−1 hydrochloric acid solution to form a mixture with a liquid–solid ratio of 5:1 (mL g−1). After stirring the mixture for 3 h at 85°C, it was filtered to obtain leachate and acid-leached BRRs, respectively. The ALBRR was washed once with tap water as a liquid–solid ratio of 2:1 and dried at 110°C for 6 h.

Washing liquid and leachate can be used to prepare PAC so that no waste liquid was discharged. 500 mL of the liquor was added into a 1,000 mL three-necked flask and heated to 100°C. Then, 56.13 g of aluminum hydroxide was added to the above solution to react for 3 h with a stirring rate of 200 rpm. The purpose of adding aluminum hydroxide was to neutralize acid, that is, the amount of hydroxide ions consumed by hydrogen ions (n(A1(OH)3/n(HCl) = 1/3). At this time, the Al2O3 content in the aluminum chloride solution was 8.22%. At the stirring rate of 200 rpm, 75 g of calcium aluminate was added into aluminum chloride solution to prepare PAC with different basicity.

2.2.2 Alkaline leaching

The silica extraction from the ALBRR was studied by varying the liquid-to-solid ratio (L S−1: 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 mL g−1), leaching time (0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 5 h), temperature (25°C, 45°C, 60°C, 75°C, and 90°C), and sodium hydroxide concentration (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mol L−1) to ascertain the optimal conditions. Typical process was described as follows: 100 g of ALBRR and 3 mol L−1 NaOH solution with a liquid-to-solid ratio of 5:1 are mixed in 1,000 mL three-necked round bottom flask, and then the above suspension is heated at 75°C for 2 h to extract silica.

2.2.3 Preparation of silica powder

Silica powder was prepared using the modified method as Trabzuni et al. reported [26]. 100 mL of water was introduced into an indirectly heated 1 L precipitation vessel and heated to 85°C. The pH was initially adjusted to 8.5 while maintaining this temperature by adding a little sodium silicate solution (or alkaline leaching solution). Then, a certain amount of sodium silicate is continuously added to the above aqueous solution at a rate of 20 mL min−1 and a sufficient quantity of 25% sulfuric acid to ensure that the pH was held constant value. The solution was allowed to age for 30 min. Precipitated silica was gained by washing with deionized water several times and dried.

2.2.4 Preparation of high modulus sodium silicate

According to the theoretical (nSiO2/nNa2O) ratio of 4:1, as-synthesized amorphous silica and sodium silicate were prepared under optimal alkaline leaching conditions to synthesize high-modulus ones. The synthesis temperature ranges from 75°C to 220°C. The reaction was carried out for 4 h and then filtered, and the final clear liquid obtained was high modulus sodium silicate products.

2.3 Characterization methods or analytical techniques

The mineral compositions of the original BRR and the residues collected after the extraction experiments were determined with X-ray diffraction (XRD; Shimadzu ZU, Japan). X-ray powder diffraction patterns were obtained using a Rigaku D/max-TTR III X-ray diffractometer, at 40 kV and 250 mA, and using Cu Kα filtered radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm). The samples were subjected to full-element analysis using XRF-1800 wavelength dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF; Test equipment comes from Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). The morphology of solid samples was observed using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-IT300, JEOL), and the equipment is produced by Japan JEO LTD. The concentrations of major elements (Al, Fe, Ti, and Ca) were obtained by hydrochloric acid (8 mol L−1) digestion followed by inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometry (ICAP7400 Radial, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) analysis. FT-IR spectra were recorded in the region 4,000–400 cm−1 in a WQF-200 model infrared Fourier transform spectrometer made by Beijing Optical Instrument Factory (China), using the KBr pellet technique (about 1 mg of sample and 300 mg of KBr were used in the preparation of the pellets).

2.4 Determination of sodium silicate modulus

The determination of sodium oxide and silica content in sodium silicate is carried out according to Chinese standard GB/T 4209-2008. The modulus of sodium silicate is calculated as the molar ratio (Mod) of silica and sodium oxide, and calculated according to Eq. 1:

where w 1 and w 2 are the mass fraction of silica and sodium oxide in the water glass, respectively, and 1.032 is the relative molecular mass ratio.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 BRR analysis

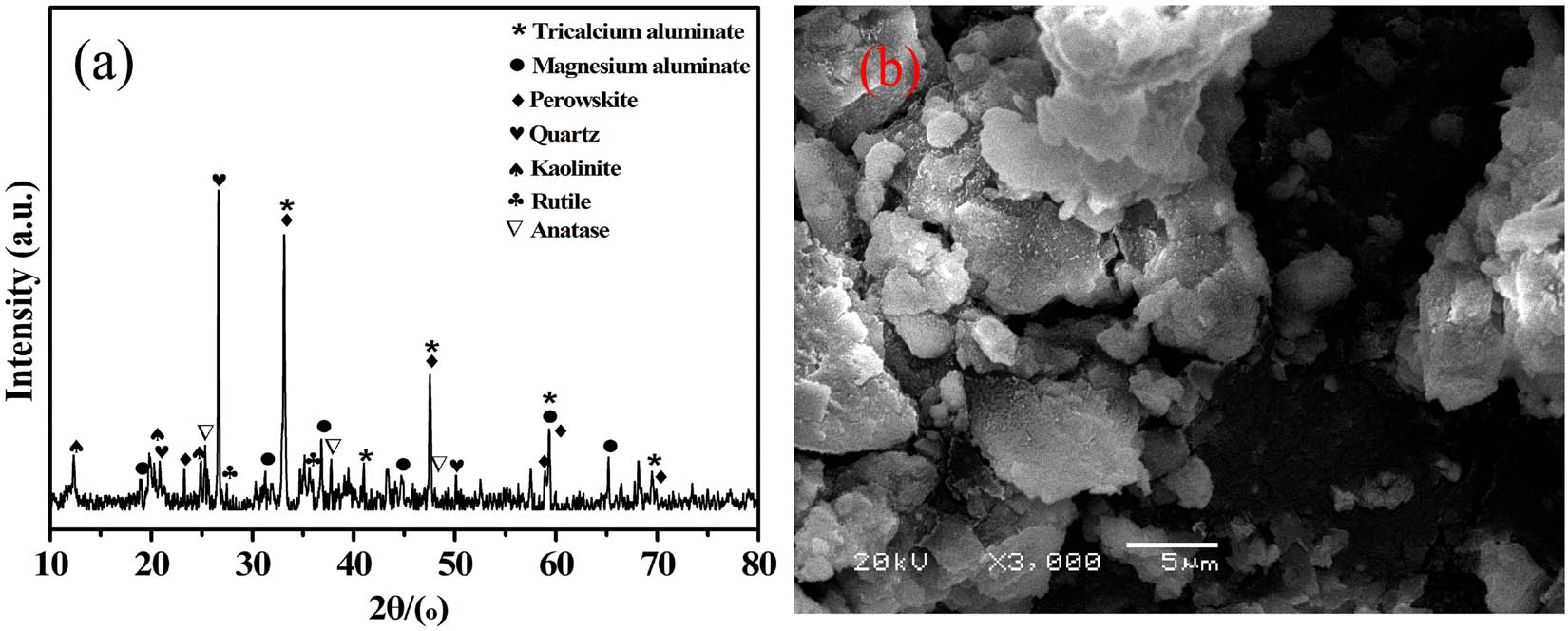

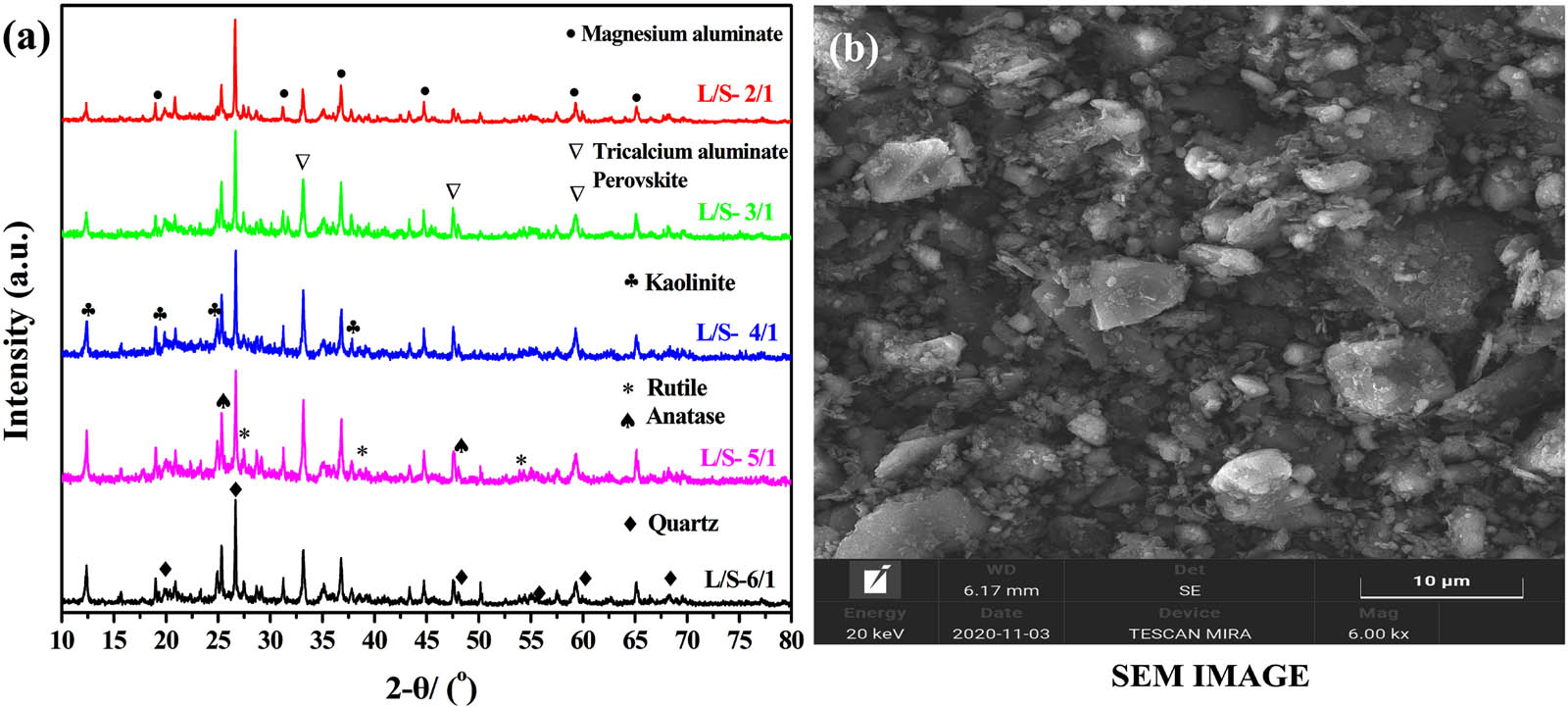

The XRD pattern of BRR is shown in Figure 1a. It contains minerals such as quartz, tri-calcium aluminate, perovskite, anatase, rutile, kaolinite, goethite, and magnesium aluminate spinel. This result is consistent with the literature report [28,29,30,31].

Bauxite reaction residue: (a) XRD pattern and (b) SEM micrographs.

Figure 1b clearly shows the surface morphology of the original residue, which is composed of irregular blocks with dense particles and poor dispersion. The result is caused by the residual PAC wrapping on unreacted bauxite ore and aluminum calcium powder surface. Because the residual product is a high-basicity PAC, it is easy to cause block adhesion. Moreover, there is a large amount of amorphous silica in the BRR. Before the production of PAC from bauxite, the bauxite has been calcined and activated at high temperature, and the reaction of hydrochloric acid and activated silicate minerals will form amorphous silica. Relevant studies have shown that when silicate minerals (such as kaolinite) are leached, silica enters the residue in an amorphous from ref. [32]. The dissolution of kaolinite and the formation of precipitated silicon are carried out according to Eqs 2 and 3:

3.2 Acid leaching and aluminum recovery

According to the analysis results of raw materials, BRR is an acidic solid waste containing PAC. The presence of PAC causes BRR particles to adhere to each other and poor dispersibility. Under normal cleaning conditions, it is difficult for BRR to achieve the purpose of dumping and reuse, and a large amount of washing wastewater is generated to pollute environment. However, hydrochloric acid can not only effectively destroy the structure of PAC, but also convert it into aluminum chloride solution. When BRR is treated with hydrochloric acid, it can completely remove chloride ions because of the absence of PAC. Meanwhile, PAC decomposition is illustrated in Eq. 4. At the same time, the obtained leachate can be reused to prepare PAC. The ALBRR produced in this process is a low-priced raw material for preparing industrial-grade sodium silicate.

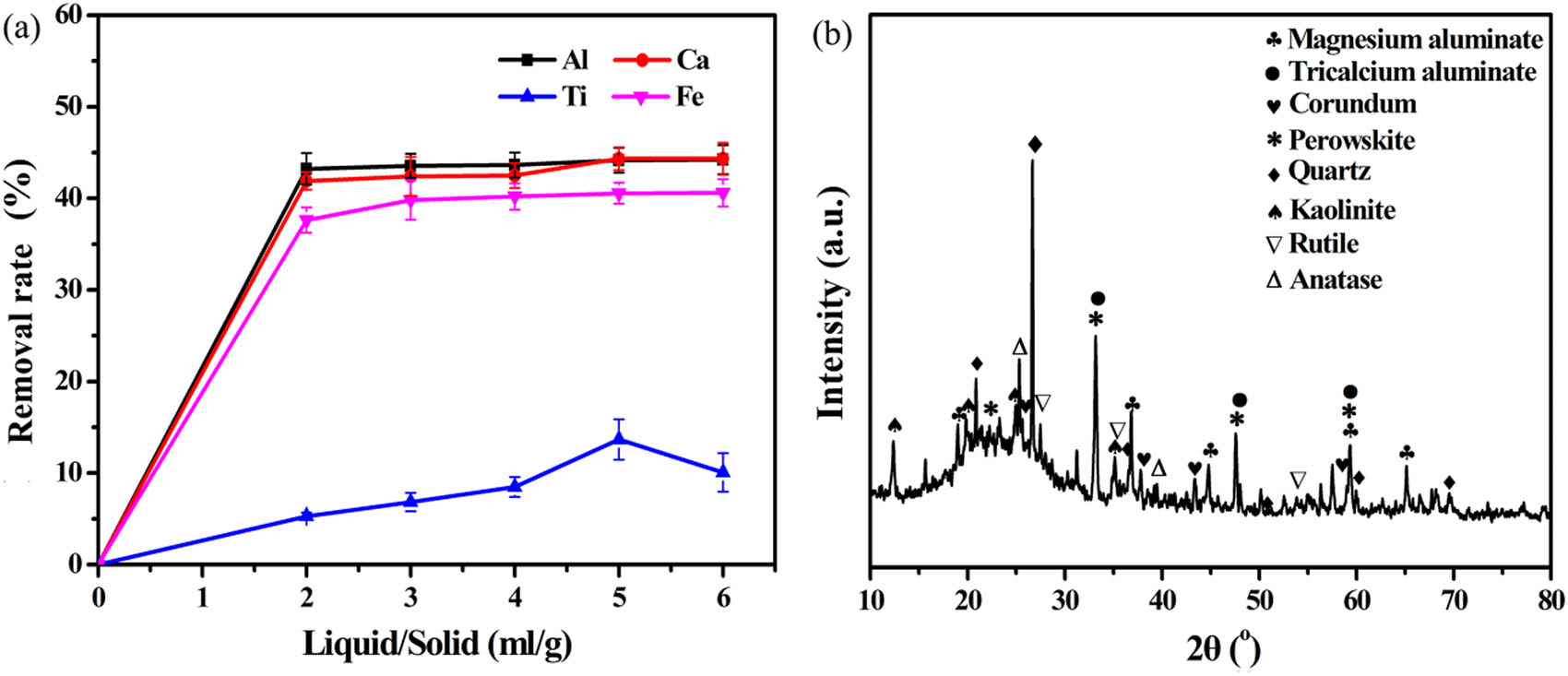

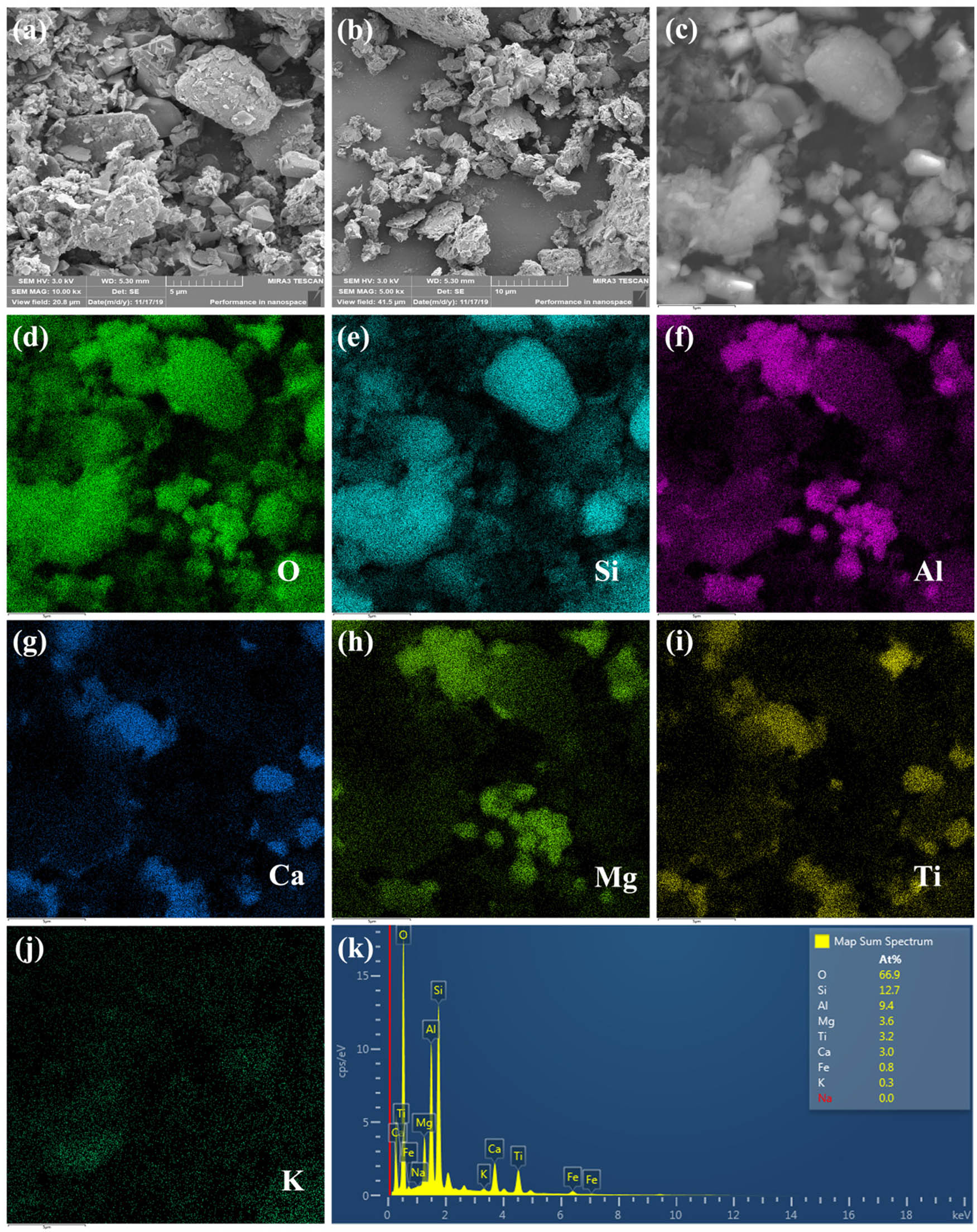

Acid experiment of BRR was carried out by leaching with 8 mol L−1 hydrochloric acid solution at 85°C for 3 h. From the perspective of liquid–solid ratio, when the liquid–solid increases to 2:1, the removal rate of aluminum, calcium, iron, and titanium increases from 0 to 43.22%, 41.89%, 37.62%, and 5.29%, respectively. The liquid-to-solid ratio was continued to increase to 6:1, and the extraction rate (Al: 44.24%, Ca: 44.33%, Fe: 40.60%, and Ti: 10.08%) of the corresponding metal only changed slightly except for titanium. Figure 2a clearly shows that the trend of titanium extraction first increases and then decreases. This is because after the titanium is dissolved from the titanate mineral, it is precipitated again in the form of rutile [33,34]. The result shows that the removal effect of aluminum, calcium, and iron are better than that of titanium. The reason is that titanium mainly exists in BRR in the form of rutile and anatase. It is difficult to achieve titanium leaching at low temperature. To reduce the influence of other elements on the subsequent silica extraction, BRR was leached with excess hydrochloric acid solution. Therefore, the best liquid–solid ratio is set as 5:1. Meanwhile, the chemical composition of the ALBRR is provided in Table 2. Compared with Table 1, the chloride ions after acid leaching can be easily washed and removed by deionized water. The removal effect is remarkable, and the removal rate reaches 96.94%. View of thermodynamic, silicate minerals such as tricalcium aluminate, perovskite, kaolinite, and spinel magnesium aluminate can react with hydrochloric acid at room temperature. However, the solubility of minerals is significantly affected by the combination of minerals, particle density, and size [27,35]. The elemental mapping in Figure 3 shows that the minerals are intertwined. This is the main reason why it is difficult to completely remove aluminum, calcium, and iron [36]. Most reports only focus on the extraction of valuable metals or non-metal from waste, and rarely care about the reuse of leachate [37]. In this article, the extract solution is used to prepare PAC to realize the reuse of the extract. The reaction of preparation liquid PAC is shown in Eq. 5 [38]:

(a) Removal of harmful elements by acid leaching pretreatment; (b) XRD diffractogram of ALBRR (HCl concentration: 8 mol L−1, time: 3 h, temperature: 85°C).

Element composition of acid leaching residue

| Element | Si | O | Al | Ti | Ca | Fe | Cl | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | 26.19 | 37.55 | 11.98 | 5.23 | 5.12 | 4.55 | 0.51 | 8.87 |

Acid leaching residue SEM images (HCl concentration: 8 mol−1, L S−1: 5/1, temperature: 85°C, leaching time: 3 h); (a–c) SEM images of acid leaching residue; (d–j) elements mapping O, Si, Al, Ca, Mg, Ti, and K; (k) energy spectrum.

PAC was determined according to the drinking water standard of China GB-15892-2009 [38]. The content of Al2O3 in the liquid PAC was 11.24%, the basicity was 86.6%, and the heavy metal content was lower than the standards required (in Table 3). It can be seen from Table 3 that the quality of PAC can reach the drinking water standard of China GB-15892-2009. This process achieves efficient leaching of aluminum in BRR and reuse of leaching solution.

Detection of heavy metals in liquid PAC according to drinking water standard of China GB-15892-2009

| LPAC | As (%) | Cd (%) | Cr (%) | Hg (%) | Pb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard (wt) | ≤0.0002 | ≤0.0002 | ≤0.0005 | ≤0.00001 | ≤0.001 |

| Content (wt) | 0.000064 | 0.000043 | 0.00018 | 0.0000066 | 0.00072 |

3.3 The effect of alkaline leaching on the silica extraction

3.3.1 The effect of calcium and aluminum on silica extraction

Generally, aluminum, calcium, and chlorine in BRR are the primary elements that affect the silica extraction [39]. The acid leaching treatment has a significant effect on the removal of chloride ions. Therefore, this section of the experiment only discusses the hindering effect of aluminum and calcium on the extraction of silica. Before the start of the ALBRR silica extraction experiment, calcium oxide and sodium aluminate simulation experiments were used to study the effect of aluminum and calcium on the silica extraction process. 500 mL of sodium hydroxide (3 mol L−1) was used to dissolve 56 g of pure amorphous silica (the amount of this amorphous silica is equivalent to the total amount of silica in 100 g of ALBRR). The effect of alkaline solution dissolving different calcium oxide and sodium aluminate alone on silica extraction was investigated.

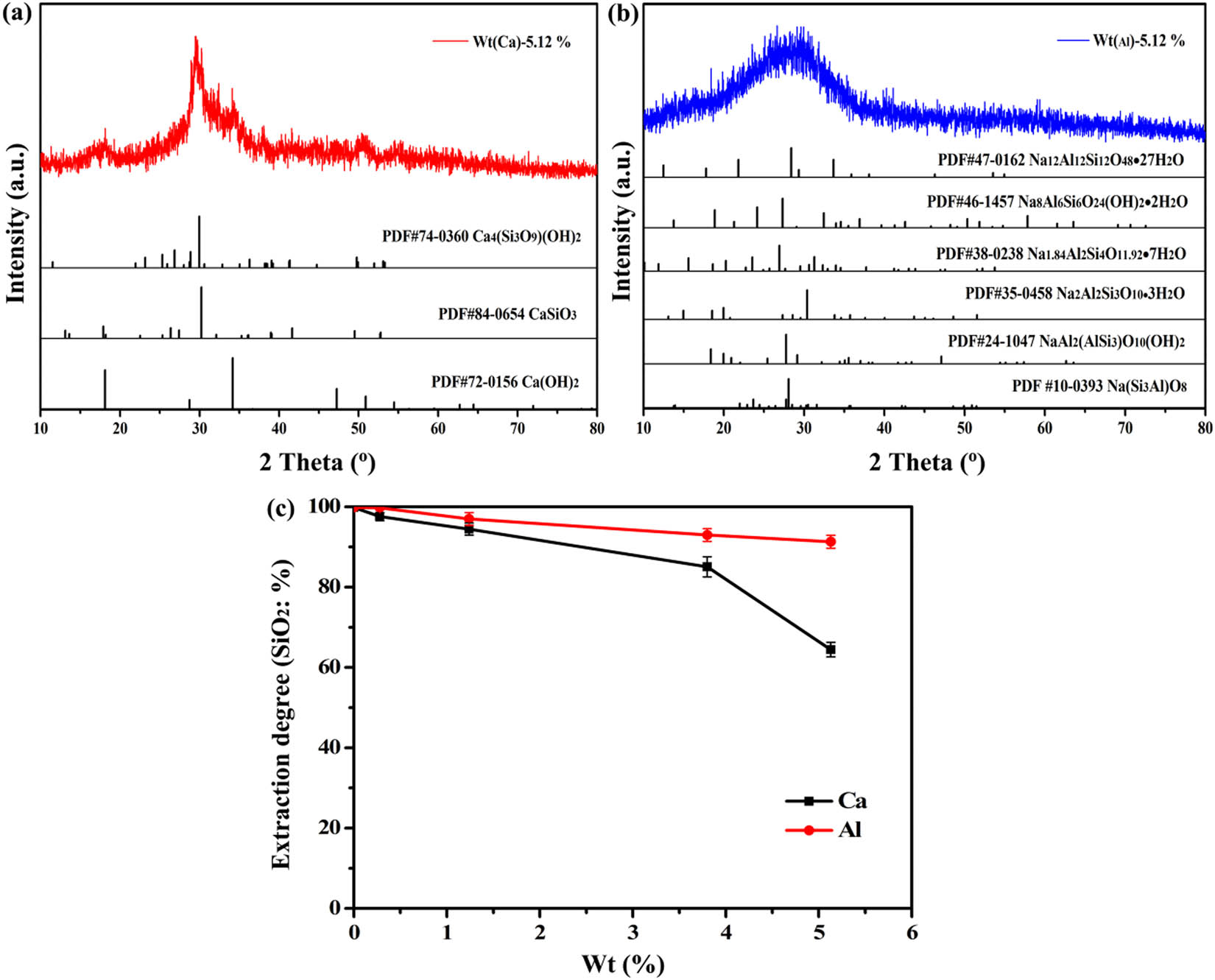

Figure 4c shows that both aluminum and calcium affect the dissolution of silica, and the dissolution rate of silica decreases with the addition of calcium oxide and sodium aluminate. First, the silicate mineral reacts chemically with the alkali during the reaction, and then the silica enters the solution in the form of SiO3 2−. The silicate ion reacts with sodium aluminate and calcium hydroxide respectively, and then silicon precipitates out in the form of hydrated sodium aluminosilicate and hydrated calcium silicate [40]. These precipitates cover the surface of the ALBRR and further hinder the extraction of silica. The dissolution of amorphous silica and the formation of silicon residue in the process silica extraction happen according to Eqs. 6–9.

(a) Calcium-silicon residue (Wt Ca: 5.12%); (b) aluminum-silicon residue (Wt Al: 5.12%); (c) the effect of alkaline dissolving different calcium and aluminum on silica extraction.

Dissolution reaction:

Precipitation reaction:

Figure 4a indicates that calcium silicate and its hydrated precipitate are formed when calcium oxide is added alone. The process hardly consumes sodium hydroxide, and the utilization rate of alkali is hardly affected. However, after the soluble silica is dissolved, the silicon precipitates out in the form of calcium silicate, which significantly reduces the dissolution of silica. Compared with calcium, aluminum has less influence on the extraction of silica, but the utilization rate of sodium hydroxide and the dissolution rate of silica are affected to varying degrees.

XRD of sodium aluminum silicate residue shows that different hydrated sodium aluminum silicates are coexisting in the filter residue (Figure 4b). Kaolinite dissolves in alkaline media, giving rise to silica [SiO2(OH)2]2− and [SiO(OH)3]− as well as aluminum [Al(OH)4]− monomers. These monomers can inter-react to yield aluminosilicate that precipitates in the form of a Na2O–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O gel or zeolite [25,41]. Therefore, the hydrochloric acid pretreatment is necessary to effectively remove calcium and aluminum in the BRR.

3.3.2 The influence of liquid–solid ratio on silica extraction

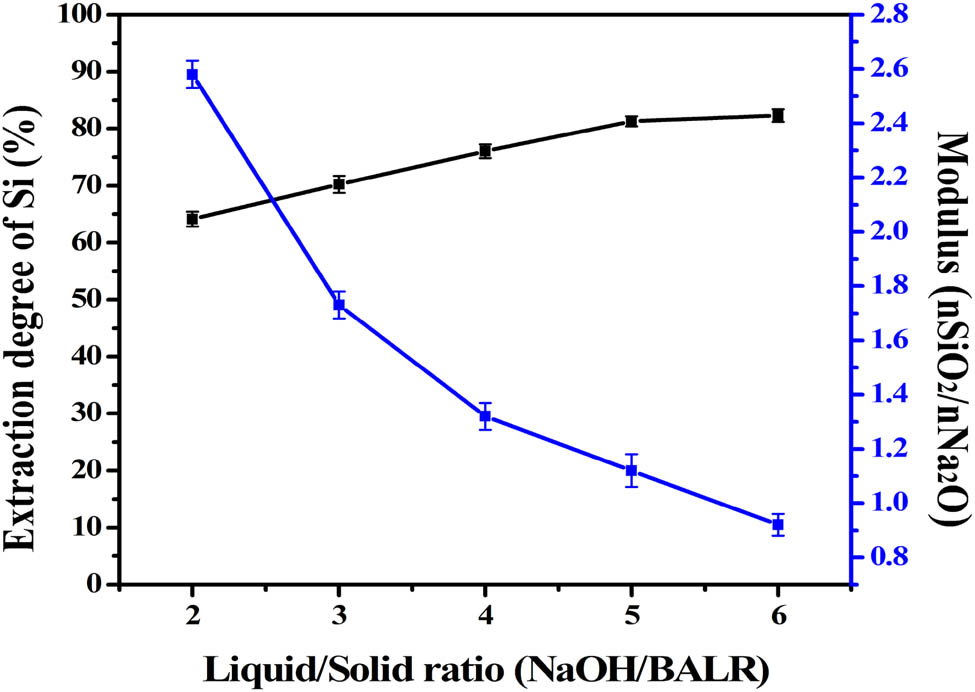

The silica extraction from ALBRR was performed to understand the dissolution behavior of silica and the formation of secondary silicate species. Sodium silicate was prepared using ALBRR with 3 mol L−1 NaOH solution at 75°C for 2 h. The effect of liquid–solid ratio was investigated to find the optimum conditions to achieve maximum recovery of silica, and the results are provided in Figure 5.

The influence of liquid–solid ratio on sodium silicate modulus and silica extraction rate (NaOH concentration: 3 mol L−1, time: 2 h, temperature: 75°C).

Approximately, 64.15% of the available silica was dissolved during the first liquid–solid ratio of 2:1. The dissolution of silica increased 81.45% when the liquid–solid ratio was reached to 5. Moreover, when the ratio was increased to 6 under the same conditions, it resulted in only a minor increase for the extraction rate. However, the modulus of liquid sodium silicate showed the opposite result, decreasing from 2.58 to 0.92, which is an inevitable result. As the liquid-solid ratio increases, the amount of silica in the solution increased is much lower than that of sodium hydroxide.

Table 4 shows that a small amount of iron and titanium is dissolved into the alkaline leaching solution. However, iron and titanium have almost no effect on silica extraction, compared with aluminum and calcium. In this process, the aluminum dissolution rate is relatively high, and the dissolution rate of Al tends to slow down with the increase in the liquid-to-solid ratio, which is 7.65% when the liquid-to-solid ratio is 6:1. Owing to the diverse combinations of Al and Si in BRR, its silicate minerals have both island and layered structures, and part of Al exists in the crystal lattice of kaolinite and magnesium aluminate.

The influence of liquid–solid ratio on the dissolution of impurity elements

| L S−1 (%) | 2/1 | 3/1 | 4/1 | 5/1 | 6/1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 3.27 | 4.64 | 5.06 | 7.01 | 7.64 |

| Fe | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Ti | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| Ca | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

Under ideal conditions and without considering the side reactions, the reactions occurring in the alkaline leaching process of ALBRR are shown in Eqs. 10–14 [42,43]. Corresponding thermodynamic calculation results are presented in Table 5. Thermodynamic data show that rutile, anatase, and quartz can react with sodium hydroxide at room temperature. However, as the Gibbs free energy of the reaction is close to zero, it can be considered that there is almost no reaction at room temperature. Total dissolution rate of aluminum is about 7% when the liquid–solid ratio is 6. The dissolution of aluminum can be attributed to the following two minerals: kaolinite and alumina. This means that less sodium silicate is obtained from decomposition of kaolinite. Almost all of the silicon dissolved in the sodium hydroxide solution comes from the amorphous silica in ALBERR.

Thermodynamic data for the reaction process taken place in sodium hydroxide leaching process (

| Equation | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

10.31 | −1949.33 | 1.12 | 8.27 |

|

|

42.23 | 323.91 | −168.52 | 44.05 |

|

|

158.02 | −1845.62 | 51.39 | −5.18 |

|

|

−4.39 | −2062.10 | 59.81 | −7.06 |

Comparing Figures 6a and 2a, when the residue recovered after silica extraction experiments with varying L S−1, the “bread-like” peak (2θ from 18° to 28°) disappears [44]. It is generally considered that the disappeared peak is the diffraction peak of amorphous silica. With the increase in the liquid–solid ratio, the diffraction peaks of other mineral phases are relatively strengthened. As the liquid–solid ratio increases, the diffraction peaks of other mineral phases are relatively enhanced in alkali leaching residue. This is caused by the dissolution of the soluble silica covering the surface of the mineral. Therefore, considering the extraction rate of silica and cost, the optimal liquid-to-solid ratio is 5:1. Meanwhile, the concentrations of SiO2 and Na2O in as-prepared sodium silicate are 76.03 and 72.70 g L−1, respectively. The morphology of alkali leaching residue recovered after the silica extraction with liquid–solid ratio of 5 is shown in Figure 6b. SEM images of alkaline leaching residue show that the residue is composed of nonuniform blocks. Some blocks have sharp edges and corners. The substance may be quartz and insoluble silicate minerals. In addition, the surface of the bulk alkali leaching slag is composed of many fine particles, which are usually calcium silicate, sodium aluminum silicate slag, and zeolite [25].

(a) XRD diffractogram mineral phases present in the ALBRR recovered after the extraction experiments with varying L S−1 for the duration of 2 h at 75°C; (b) ALBRR SEM image (L S−1 of 5, time: 2 h, temperature: 75°C).

3.3.3 Effect of reaction time on silica extraction

According to the above results, when the liquid–solid ratio reaches a fixed value, it is worth noting that the unilateral increase in the liquid-to-solid ratio no longer affects the dissolution of silica. However, it is not clear whether this is affected by reaction time and temperature. Therefore, when the liquid-to-solid ratio is 5:1 and other conditions remain unchanged, the effect of the reaction time on the silica extraction rate was investigated (Figure 7).

Effect of reaction time on silica extraction (NaOH concentration: 3 mol L−1, L S−1: 5/1, temperature: 75°C).

Figure 5 illustrated the effect of the reaction time on the silica extraction rate. The results show that the dissolution of silica in ALBRR is very rapid, and the silica extraction rate has reached 76.46% in a relatively short period of 0.5 h. When the reaction was carried out for 5 h, it resulted in only a minor increase (5.82%) for the extraction rate of silica. The initial source of dissolved silica can be attributed to the amorphous phases. This shows that the effect of reaction time on silica extraction does not seem to be important. It can be deduced that most of the silicate minerals generate silicic acid and amorphous silica precipitates and remain in the BRR when aluminum is extracted by hydrochloric acid in the process of producing PAC from bauxite. Most of the silica in the BRR is not wrapped with other minerals, so that the vast majority of the silica are easily recovered by sodium hydroxide, as we expect.

3.3.4 Effect of reaction temperature on silica extraction

In view of energy consumption, the influence of reaction temperature on silica extraction is also a crucial factor. When the reaction time is 2 h, the effect of reaction temperature on the extraction rate of silica in ALBRR is studied under normal pressure (Figure 8). Silica extraction rate increases from 72.13% to 81.84% when leaching temperature is increased from 25°C to 90°C, and the corresponding modulus of liquid sodium silicate was between 1.01 and 1.12. Leaching was completed in a relatively low temperature because of the high dissolving amorphous silica.

Effect of leaching temperature on silica extraction (NaOH concentration: 3 mol L−1, L S−1: 5/1, time 2 h).

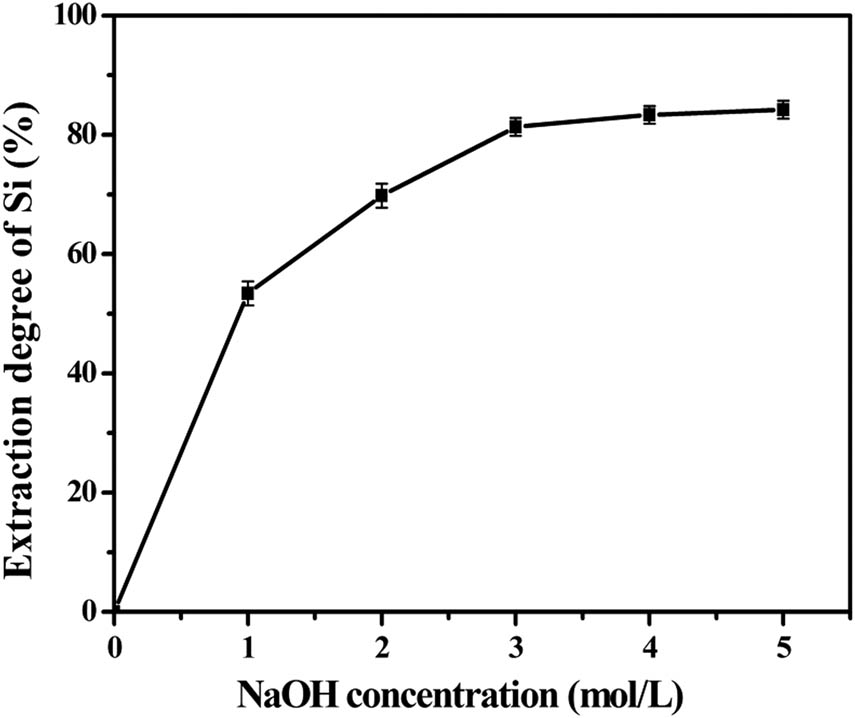

3.3.5 Effect of sodium hydroxide concentration on silica extraction

Whether the increase in the concentration of sodium hydroxide improves the dissolution of other silicate minerals to increase the extraction rate of silica, then the concentration is considered. Other reaction conditions remain unchanged, and the silica extraction results under the varying NaOH concentrations are shown in Figure 9.

Effect of sodium hydroxide concentrations on silica extraction (L S−1: 5/1, time 2 h, temperature: 75°C).

When the concentration of sodium hydroxide increases from 0 to 5 mol L−1, the silica extraction rate of in ALBRR increases from 0% to 85.66%. The silica extraction is significantly affected by the concentration of NaOH. The chemical compositions of ALBRR after alkaline leaching with liquid–solid ratio of 5:1 for 2 h are presented in Table 6. Comparing Tables 6 and 2, it can be seen that the silica in the BRR mainly exists in the form of amorphous silica. The residue contains silicate minerals such as quartz and kaolin (Figure 6a), resulting in the silica extraction rate of only 85.66%. However, alkaline leaching of ALBRR can effectively reduce the amount of residue. The residue rate recovered after silicon extraction was reduced by 50% on the basis of ALBRR.

Element composition of alkaline leaching residue

| Element | Si | O | Al | Ti | Ca | Fe | Cl | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | 9.72 | 32.35 | 22.28 | 10.44 | 10.21 | 9.08 | 0.51 | 5.92 |

Figure 10 shows a plan view of the molecular structure of liquid sodium silicate prepared from quartz and amorphous silica, respectively. As shown in Figure 10, considering the bond energy alone, the simplest amorphous silica only needs to disconnect two Si–O bonds to form the intermediate monomer structure [45]. However, quartz of needed to break four Si–O bonds and a single Si–O bond is 460 kJ mol–1. Therefore, quartz usually adopts high pressure hydrothermal method to prepare liquid sodium silicate. However, the modulus of liquid sodium silicate produced by this method is difficult to reach 2.5 or more [26]. Most literature reports that raw materials with amorphous silica as the main component, such as micro-silica fume and white carbon black, can be used to prepare high-modulus liquid sodium silicate by high-pressure hydrothermal reaction.

Schematic diagram of the molecular structure of sodium silicate prepared from quartz and amorphous silica.

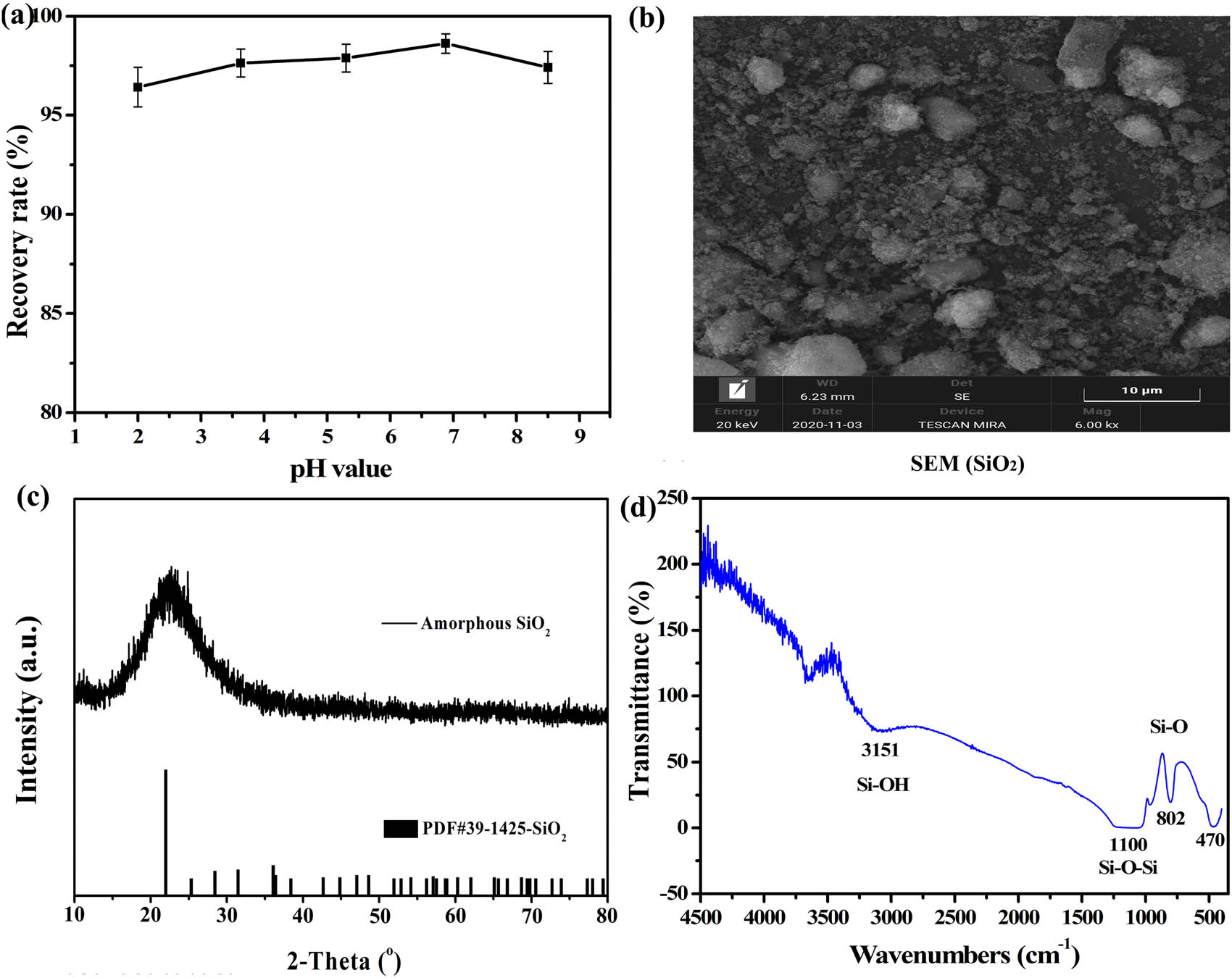

3.4 Preparation of amorphous silica by sodium silicate solution

The pH value of the solution is approximately 9 or below, and the solubility of amorphous SiO2 is constant. It has been reported by various investigators to be 100–150 mg of SiO2 per liter (1.67–2.5 mmol L−1) at 25°C, the soluble species being in the form of Si(OH)4 [10]. Therefore, precipitated silica can be prepared using acid to acidulate alkaline leaching solution obtained (leaching conditions: 3 mol L−1 sodium hydroxide, 75°C and 2 h). Add here, 30 wt% of sulfuric acid was used. The effect of pH on the recovery of precipitated silica was studied in Figure 11a.

(a) Recovery rate of silica in sodium silicate; (b) SEM spectrum of amorphous silica at pH = 7; (c) XRD spectrum of amorphous silica; (d) FTIR spectral for amorphous silica.

As can be seen from Figure 11a, under different pH conditions, the recovery rate of silica has reached more than 96%, and it is more conducive to recovery under neutral conditions pH value of 7 [46]. The silica has a higher recovery rate of 98.62%, and there is less sulfuric acid consumption, and finally only a neutral liquid sodium sulfate solution is produced. The XRD pattern of amorphous silica obtained under neutral conditions is shown in Figure 11c. Because amorphous silica lacks crystalline phase and display disordered structure, it usually shows broad diffraction peaks (2θ from 15° to 30°) [26]. In addition, no obvious impurity peaks can be observed. The result shows that liquid sodium silicate can be acidified using H2SO4 to prepare pure amorphous silica.

Figure 11b shows the SEM images of amorphous silica. The microstructure of amorphous silica presents flocculent and crushed solids; meanwhile, some particles present compact solids. When the pH of the sodium silicate solution drops below 9, multi-nuclear silicon and mononuclear silicon in the solution polymerize to form polysilicic acid, and then the polysilicic acid colloid is dehydrated to form precipitated silicon.

The polymerization rate of silicic acid in this process can significantly affect the particles size of precipitated silica. The precipitation of amorphous silica apparently proceeds in a series of step; mono or oligonuclear silica species will condense by formation of Si–O–Si bonds to polysilicates (polymerization). Further polymerization accompanied by cross-linking reactions and aggregations (by van der Waal forces) leads to negatively charged silica “sols.” Further aggregation may eventually lead to the formation of gels [47].

The IR spectra for amorphous silica prepared with pH value of 7 is shown in Figure 11d. The characteristics bonds at 1,100, 811, and 470 cm−1 are characteristic absorption positions of silica, where the absorption peaks at 470 and 811 cm−1 are commensurate with the antisymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the Si–O bond, respectively. The absorption peaks at 1,100 cm−1 be attributed to the bending vibration of the Si–O–Si bond [44]. The absorption peaks at 1,630 and 3,221 cm−1 are the absorption peaks of water molecular structure (capillary water, surface adsorption water, and structured water). The former is the bending vibration peak of H–O–H, and it is related by free water (capillary water and surface adsorbed water). The latter is the antisymmetric stretching vibration peak of O–H, which is related to structured water [24,48,49]. The infrared results show that the prepared silica contains a small amount of water, and there is no absorption peak of other substances except amorphous silica. In this article, our work on the silica extraction was compared with similar documents, as shown in Table 7. Comparative results show that the process is simple in process conditions. Furthermore, the acidic liquid produced in the pretreatment process can be recycled.

Comparing the extraction of silica from different raw materials in similar literature

| Raw material | Pretreatment | Leaching conditions | SiO2 extraction rate (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incineration bottom ash | HNO3: 4 mol L−1, time: 24 h, 20°C | NaOH: 0.4 mol L−1, L S−1 of 50/1, 90°C and 72 h | 56 | [25] |

| Rice husk ashes | HCl: 3 mol L−1, time: 24 h, then calcined at 700°C, 2 h | 1–8 mol L−1 NaOH and 1–4 h | 80–99 | [42] |

| Waste container glasses | Wet milling 48 h, dried for 72 h | NaOH: 3 mol L−1, L S−1 of 8/1, 200°C and 3 h | 100 | [46] |

| Palygorskite powder | Calcined at 560°C for 1 h: H2SO4: 0.5 mol L−1, time: 12 h | Without alkali leaching treatment | 92 | [47] |

| Bauxite reaction residue | HCl: 8 mol L−1, time: 3 h, 85°C | NaOH: 3 mol L−1, L S−1 of 5/1, 75°C and 2 h | 81.45 | This work |

3.5 Preparation of high modulus liquid sodium silicate

High modulus sodium silicate is usually hydrothermally synthesized, but this article can be synthesized at low temperature. The use of amorphous silica as silicon feedstock is a key point for the synthesis of high modulus sodium silicate. The specific operation was described as follows: amorphous silica and alkaline leaching solution (sodium silicate modulus 1.11) were mixed according to sodium silicate theoretical modulus of 4 to prepare high modulus liquid sodium silicate. After 4 h of reaction at different temperature, it was filtered to obtain high-modulus sodium silicate.

Observed in Figure 12, liquid sodium silicate in combination with amorphous silica is used to prepare high-modulus liquid sodium silicate at different temperatures. It can be seen from the experimental results that amorphous silica is easily soluble in alkaline solutions and has a high solubility. Liquid sodium silicate with a modulus of 3.27 can be prepared at 75°C under normal pressure. Meanwhile, the modulus of the product increases with the increasing reaction temperature, with reaching 3.72 at 220°C. At different synthesis temperatures, those process can prepare industrial grade sodium silicate using BRR, which meets China’s Class 2 premium product standards (GB/T 4209-2008). The success of the above experiment is based on the following principles. According to related literature reports [47], there are three important areas in the amorphous silicon concentration-pH diagram: (1) the insoluble domain is the precipitation zone of amorphous silicon; (2) the multimeric domain where silicon polyanions are stable; and (3) the monomeric domain where mononuclear Si species [Si(OH)4, SiO(OH)3 −, and SiO2(OH)2 2−] prevail thermodynamically. The pH value of the sodium silicate prepared in this experiment is about 12, and the relationship between its concentration and pH satisfies the second region, indicating that high modulus sodium silicate is a stable polymer.

Effect of reaction temperature on the preparation of high-modulus sodium silicate.

Scheme 1 depicts a process of comprehensive treatment of BRR. First, hydrochloric acid was adopted to leach the BRR. After that, the leached residue was washed using water to remove the water soluble component. Acid leaching solution was recycled to prepare PAC. Finally, the ALBRR was used as a silicon source to prepare high modulus liquid sodium silicate. The process is not discharged from wastewater and has a simple operation. The total residue rate can be lowered below 35%. This process provides reliable experimental data and theoretical basis for the utilization of BRR.

The process flow chart of comprehensive treatment of BRR.

4 Conclusions

Low temperature synthesis route to convert environmentally harmful acid solid waste BRR into precipitated silica and further synthesis of high-modulus sodium silicate was investigated.

96.94% of the chlorine in BRR can be removed by pre-treatment, which mainly exists in the form of PAC. The obtained liquid was also reused to prepare PAC (Al2O3 content and basicity were 11.24% and 86.6%, respectively).

Influence of alkaline solution dissolving different calciumoxide and sodium aluminate on silica extraction shown they form hydrated calcium silicate, sodium aluminum silica residue and zeolite with silicon, respectively. Those hinder the extraction of varying degrees of amorphous silica.

The silica extraction rate from ALBRR reached 81.45% and modulus of liquid sodium silicate obtained (nSiO2:nNa2O) was 1.11 with liquid–solid ratio of 5:1 at the 3 mol L−1 NaOH heating to 75°C for 2 h. The total residue rate of BRR via the whole treatment process is reduced to 35%.

Recovery rate of amorphous silica from alkaline leachate reached 98.62% using sulfuric acid at pH of 7. Then liquid sodium silicate in combination with amorphous silica is used to prepare liquid sodium silicate with a modulus of 3.27 at 75°C for 4 h. The results of this study show that transforming the environmentally harmful BRR into the high-modulus sodium silicate is a viable technical route.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Gongyi produces poly-aluminum chloride solid waste silicon of Central South University (738010217).

-

Author contributions: Yunlong Zhao completed the experiment and paper writing; Yajie Zheng mainly guided the paper direction and paper revision; Hanbin He completed XRD and SEM data analysis; Zhaoming Sun completed ICP detection and part of the data analysis; An Li participated in part of the experimental research and discuss.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Amano M, Lohwacharin J, Dubechot A, Takizawa S. Performance of integrated ferrate-polyaluminum chloride coagulation as a treatment technology for removing freshwater humic substances. J Environ Manag. 2018;212(APR 15):323–31. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.02.022.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Ghafari S, Aziz HA, Bashir MJK. The use of poly-aluminum chloride and alum for the treatment of partially stabilized leachate: a comparative study. Desalination. 2010;257(1–3):110–6. 10.1016/j.desal.2010.02.037.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Matsui Y, Shirasaki N, Yamaguchi T, Kondo K, Mschida K, Fukuura T, et al. Characteristics and components of poly-aluminum chloride coagulants that enhance arsenate removal by coagulation: detailed analysis of aluminum species. Water Res. 2017;118:177–86. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.04.037.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Benschoten JEV, Edzwald JK. Chemical aspects of coagulation using aluminum salts-I. Hydrolytic reactions of alum and polyaluminum chloride. Water Res. 1990;24(12):1519–26. 10.1016/0043-1354(90)90086-l.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Wang XM, Wang X, Yang MH, Zhang SJ. Sludge conditioning performance of polyaluminum, polyferric, and titanium xerogel coagulants. Environ Sci. 2018;39(5):2274–82. 10.13227/j.hjkx.201710205.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Zhang M, Xiao F, Wang DS, Xu XZ, Zhou Q. Comparison of novel magnetic polyaluminum chlorides involved coagulation with traditional magnetic seeding coagulation: coagulant characteristics, treating effects, magnetic sedimentation efficiency and floc properties. Sep Purif Technol. 2017;182:118–27. 10.1016/j.seppur.2017.03.028.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang ZG, Wang JL, Li D, Wang JY, Song XL, Yue BY, et al. Hydrolysis of polyaluminum chloride prior to coagulation: effects on coagulation behavior and implications for improving coagulation performance. J Environ Sci. 2017;57:162–9. 10.1016/j.jes.2016.10.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Lu GL, Yu HY, Bi SW. Preparing and application of polymerized aluminum-ferrum chloride. Adv Mater Res. 2011;183–185:1956–60. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.183-185.1956.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Li A, Zheng YJ, Peng YL, Zhai XK, Long H. Activation of aluminum-calcium leaching residue and its application in zinc smelting wastewater treatment. Chin J Nonferrous Met. 2019;5:1073–82. 10.19476/j.ysxb.1004.0609.2019.05.21.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Tang HX. Inorganic polymer flocculation theory and coagulant C. Chapter 4. Baiwanzhuang, Xijiao, Beijin: China Building Industry Press; 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Gao JY, Gao FZ, Zhu F, Luo XH, Jiang J, Feng L, et al. Synergistic coagulation of bauxite residue-based poly-aluminum ferric chloride for dyeing wastewater treatment. J Cent South Univ. 2019;26(2):449–57. 10.1007/s11771-019-4017-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Liu WC, Yang JK, Xiao B. Review on treatment and utilization of bauxite residues in China. Int J Min Process. 2009;93(3–4):220–31. 10.1016/j.minpro.2009.08.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Borra CR, Pontikes Y, Binnemans K, Gerven TV. Leaching of rare earths from bauxite residue (red mud). Min Eng. 2015;76:20–7. 10.1016/j.mineng.2015.01.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Nematollahi B, Sanjayan J, Shaik FUA. Synthesis of heat and ambient cured one-part geopolymer mixes with different grades of sodium silicate. Ceram Int. 2015;41(4):5696–5704. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.12.154.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Witoon T, Tatan N, Rattanavichian P, Chareonpanich M. Preparation of silica xerogel with high silanol content from sodium silicate and its application as CO2 adsorbent. Ceram Int. 2011;37(7):2297–2303. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2011.03.020.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Shan WJ, Zhang D, Wang X, Wang DD, Xing ZQ, Xiong Y, et al. One-pot synthesis of mesoporous chitosan-silica composite from sodium silicate for application in Rhenium(VII) adsorption. Micropor Mesopor Mat. 2019;278:44–53. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.10.030.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Coradin T, Durupthy O, Livage J. Interactions of amino-containing peptides with sodium silicate and colloidal silica: a biomimetic approach of silicification. Langmuir. 2002;18(6):2331–6. 10.1021/la011106q.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Zhang WC, Honaker RQ. Flotation of monazite in the presence of calcite part II: Enhanced separation performance using sodium silicate and EDTA. Min Eng. 2018;127(11):318–28. 10.1016/j.mineng.2018.01.042.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Dokkum HPV, Hulskotte JHJ, Kramer KJM, Wlimot J. Emission, fate and effects of soluble silicates (water glass) in the aquatic environment. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38(2):515–21. 10.1021/es0264697.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Lazaro A, Quercia G, Brouwers HJH, Geus JW. Synthesis of a green nano-silica material using beneficiated waste dunites and its application in concrete. World J Nano Sci Eng. 2013;3(3):41–51. 10.4236/wjnse.2013.33006.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Li CC, Qiao XC. A new approach to prepare mesoporous silica using coal fly ash. Chem Eng J. 2016;302:388–94. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.05.029.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Dodson JR, Cooper EC, Hunt AJ, Matharu A, Cole J, Clark JH, et al. Alkali silicates and structured mesoporous silicas from biomass power station wastes: the emergence of bio-MCMs. Green Chem. 2013;15(5):1203–10. 10.1039/c3gc40324f.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Tong KT, Vinai R, Soutsos MN. Use of Vietnamese rice husk ash for the production of sodium silicate as the activator for alkali-activated binders. J Clean Prod. 2018;201(PT1–1166):272–86. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.025.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Shim J, Velmurugan P, Oh BT. Extraction and physical characterization of amorphous silica made from corn cob ash at variable pH conditions via sol gel processing. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;30:249–53. 10.1016/j.jiec.2015.05.029.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Alam Q, Hendrix Y, Luuk T, Lazaro A, Schollbach K, Brouwers HJH. Novel low temperature synthesis of sodium silicate and ordered mesoporous silica from incineration bottom ash. J Clean Prod. 2019;211:874–83. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.173.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Trabzuni FMS, Dekki HM, Gopalkrishnan CC. Sodium silicate solutions. Google U.S. Patents 8287822B2; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Zhao YL, Zheng YJ, He HB, Sun ZM, Li A. Effective aluminum extraction using pressure leaching of bauxite reaction residue from coagulant industry and leaching kinetics study. J Enviorn Chem Eng. 2021;9:104770. 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104770.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Liu YJ, Ravi ND. Hidden values in bauxite residue (red mud): recovery of metals. Waste Manag. 2014;34:2662–73. 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.003.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Davris P, Balomenos E, Panias D, Paspaliars I. Selective leaching of rare earth elements from bauxite residue (red mud), using a functionalized hydrophobic ionic liquid. Hydrometallurgy. 2016;164:125–35. 10.1016/j.hydromet.2016.06.012.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Avdibegovic D, Regadio M, Binnemans K. Efficient separation of rare earths recovered by a supported ionic liquid from bauxite residue leachate. RSC Adv. 2018;8:11886–93. 10.1039/c7ra13402a.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Deng BN, Li GH, Luo J, Ye Q, Liu MX, Peng ZW, et al. Enrichment of Sc2O3 and TiO2 from bauxite ore residues. J Hazard Mater. 2017;331:71–80. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.02.022.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Okada K, Shimai A, Takei T. Preparation of microporous silica from metakaolinite by selective leaching method. Micropor Mesopor Mat. 1998;21(4):289–96. 10.1016/S1387-1811(98)00015-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Ujaczki É, Courtney R, Cusack PB. Recovery of gallium from bauxite residue using combined oxalic acid leaching with adsorption onto zeolite HY. J Sustain Metall. 2019;5(2):262–74. 10.1007/s40831-019-00226-w.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Mo W, Deng GZ, Luo FC. Titanium metallurgy. 2nd ed. China: Metallurgical Industry Press; 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Valeev DV, Lainer YA, Pak VI. Autoclave leaching of boehmite-kaolinite bauxites by hydrochloric acid. Inorg Mater Appl Res. 2016;7(2):272–7. 10.1134/S207511331602026X.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Reddy BR, Mishra SK, Banerjee GN. Kinetics of leaching of a gibbsitic bauxite with hydrochloric acid. Hydrometallurgy. 1999;51(1):131–8. 10.1016/S0304-386X(98)00075-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Brahmi D, Merabet D, Belkacemi H, Mostefaoui TA, Ouakli NA. Preparation of amorphous silica gel from Algerian siliceous by-product of kaolin and its physico chemical properties. Ceram Int. 2014;40(7):10499–10503. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.03.021.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Li FT, Jiang JQ, Wu SJ, Zhang BR. Preparation and performance of a high purity poly-aluminum chloride. Chem Eng J. 2010;156:64–9. 10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.034.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Peng H, Peters S, Vaughan J. Leaching kinetics of thermally-activated, high silica bauxite. Light Met. 2019;11–7. 10.1007/978-3-030-05864-7-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Strachan DM, Croak TL. Compositional effects on long-term dissolution of borosilicate glass. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2000;272(1):22–33. 10.1016/S0022-3093(00)00154-X.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Wang H, Feng QM, Liu K. The dissolution behavior and mechanism of kaolinite in alkali-acid leaching process. Appl Clay Sci. 2016;132–133:273–80. 10.1016/j.clay.2016.06.013.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] John DA. Lang’s handbook of chemistry. Beijing: Science Press; 2003. ISBN: 7-03-010409-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] KaußEn FM, Riedrich BF. Methods for alkaline recovery of aluminum from bauxite residue. J Sustain Metall. 2016;2(4):353–64. 10.1007/s40831-016-0059-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Costa JAS, Paranhos CM. Systematic evaluation of amorphous silica production from rice husk ashes. J Clean Prod. 2018;192:688–97. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.028.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Zhang S, Liu Y. Molecular-level mechanisms of quartz dissolution under neutral and alkaline conditions in the presence of electrolytes. Geochem J. 2014;48(2):189–205. 10.2343/geochemj.2.0298.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Gorrepati EA, Wongthahan P, Raha S. Silica precipitation in acidic solutions: mechanism, pH effect, and salt effect. Langmuir. 2010;26(13):10467–74. 10.1021/la904685x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Stumm W, Huper H, Champlin RL. Formulation of polysilicates as determined by coagulation effects. Enviorn Sci Technol. 1967;1(3):221–7. 10.1021/es60003a004.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Owoeye SS, Jegede FI, Borisade SG. Preparation and characterization of nano-sized silica xerogel particles using sodium silicate solution extracted from waste container glasses. Mater Chem Phys. 2020;248:122915. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.122915.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Lai S, Yue L, Zhao X. Preparation of silica powder with high whiteness from palygorskite. Appl Clay Sci. 2010;50(3):432–7. 10.1016/j.clay.2010.08.019.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Yunlong Zhao et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis