Abstract

In the present study, we explored whether magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (MNPs-Fe3O4) can be used to alleviate the toxicity of 3-nitrophenol (3-NP) to rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings grown under hydroponic conditions. The results showed that 3-NP from 7 to 560 μM decreased the growth, photochemical activity of the photosystem II (PS II), and chlorophyll content of the seedlings in a concentration-dependent manner. In the presence of 3-NP, 2,000 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4 were added to the growth medium as the absorbents of 3-NP and then were separated with a magnet. The emergence of MNPs-Fe3O4 effectively alleviated the negative effects of 3-NP on rice seedlings. In addition, the long-term presence of MNPs-Fe3O4 (from 100 to 2,000 mg L−1) in the growth medium enhanced the growth, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), activities of antioxidant enzymes, photochemical activity of PS II, and chlorophyll content of the rice seedlings. These results suggest that MNPs-Fe3O4 could be used as potential additives to relieve the physiological toxicity of 3-NP to rice seedlings.

1 Introduction

Nitrophenols (NPs) are widely used as the raw materials or intermediates for manufacturers of explosives, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, pigments, dyes, wood preservatives, and rubber chemicals [1]. As a result, NPs are abundantly presented in aquatic environments, including river water, wastewater, and industrial effluents [2]. Even at ultralow concentrations, these NPs still have potential toxicity to human beings and animals. Thus, the US Protection Agency (UPA) has listed NPs on its “Priority Pollutant List” [3].

NPs are also highly toxic to plants [4]. Previous works have found that NPs can cause DNA damage, increase oxidative stress, and decrease the contents of chlorophyll and auxin in plants. In the last decades, the threat of NPs to agriculture has deserved special attention since it has been reported that NPs are found in the irrigation water [5], and 0.7 mM NPs in the irrigation water can cause a large number of plants to reduce production [6]. Compared with animals, plants have less mobility and thus have to face environmental pollutants frequently. In fact, before obvious and visual alterations of morphology are observed, many physiological responses of plants to toxic pollutants have occurred and ultimately determined the fate of plants [7]. Therefore, it is important to develop effective technology to reduce the physiological toxicity of NPs to crops.

Direct removal of pollutants from the contaminated environment by adsorbents is considered an effective method to limit the toxicity of pollutants to plants and other organisms [8]. For example, pesticides have undesirable impacts on human health and may appear as pollutants in water sources. A variety of activated carbon materials have been used as adsorbents to remove different varieties of pesticides from water sources [9]. Besides activated carbon, nanoparticles are applied as efficient adsorbents to remove the pollutants from the waterbody [10,11], because nanoparticles have well dispersion in water and can be easily obtained [12]. However, applying common nanoparticles in aquatic or semiaquatic environments would inevitably cause secondary pollution. The magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (MNPs-Fe3O4) are among the most widely applied nanomaterials in the industrial, biomedical, and biotechnological sectors [13]. MNPs-Fe3O4 have unique electric and magnetic properties based on the transfer of electrons between Fe2+ and Fe3+ in the octahedral sites [14]. Furthermore, compared to other nanomaterials, MNPs-Fe3O4 have exhibited better chemical stability, a large surface area, lower toxicity and price, and biocompatibility [15]. Thus, MNPs-Fe3O4 have been used as absorbents to remove contaminants from wastewater and can be easily separated from water by applying a magnetic field to avoid secondary pollution [15]. However, whether such properties of MNPs-Fe3O4 could be applied in limiting the toxicity of NPs to crops has not been extensively studied.

As one aquatic or semi-aquatic plant species, rice (Oryza sativa L.) has remarkable economic and alimentary importance [16]. In the present study, we develop a simple and novel method for alleviating the toxicity of 3-NP to rice seedlings. Briefly, MNPs-Fe3O4 as absorbents of 3-NP are added into the growth medium of rice seedlings. The emergence of MNPs-Fe3O4 can effectively alleviate the negative effects of NP on rice seedlings, and the MNPs-Fe3O4 can be separated from the growth medium by the magnetic field. We also further study the physiological responses of rice seedlings to the long-term presence of MNPs-Fe3O4 to evaluate the potential effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the plants. We believe that this research can provide some references on reducing the toxicity of NPs to crops and can further enrich current knowledge about the application of MNPs-Fe3O4 in the botany field.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

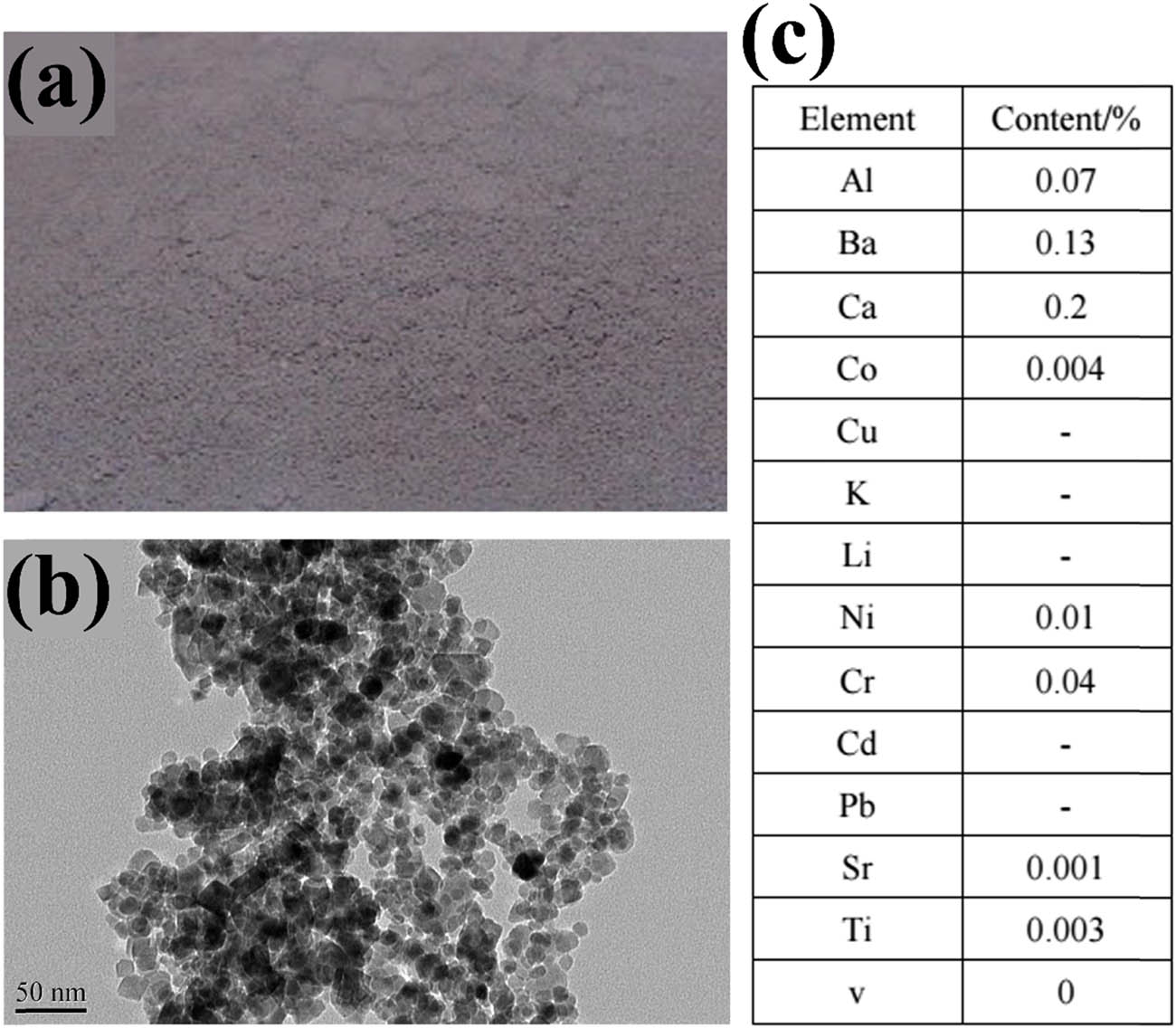

Seeds of rice (Jing-you No. 957) were obtained from China National Seed Group Company, and MNPs-Fe3O4 were obtained from China Nanjing Emperor Nano Material Company. The purity of MNPs-Fe3O4 is >99.5%, and the main impurity of the MNPs-Fe3O4 is barium. The diameter and surface of MNPs-Fe3O4 are 14.1 nm and 81.98 m2 g−1, respectively (Figure A1).

2.2 Treatments

Rice seeds were surface-sterilized for 2 min by sodium hypochlorite solution (2%, v/v). After then, the seeds were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water for 30 min and placed in Petri dishes for germination in the dark at 25°C. The germinated seeds with primary root (at least 0.5 mm) were sown in the beakers and were irrigated with 1/2 strength of Hoagland’s nutrient solution. The seedlings were grown in a climate room at 27/23°C day/night temperatures and a 12/12 h light/dark regime with 130 μmol (photon) m−2 s−1 photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). The nutrient solution in the beakers was replaced with freshly prepared 1/2 strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution every 7 days.

In the first set of experiments, 3-NP was dissolved with 3 mL of ethanol (95%, v/v) and was diluted with distilled water to the concentrations required. Twenty-one-day-old seedlings received a 70, 140, 280, and 560 μM NP solution and were cultivated under the above conditions for 5 days. The seedlings that received the solvent (an ethanol solution with a concentration equivalent to that in the NP solution) alone were set as the treatment with 0 μM NP (controls).

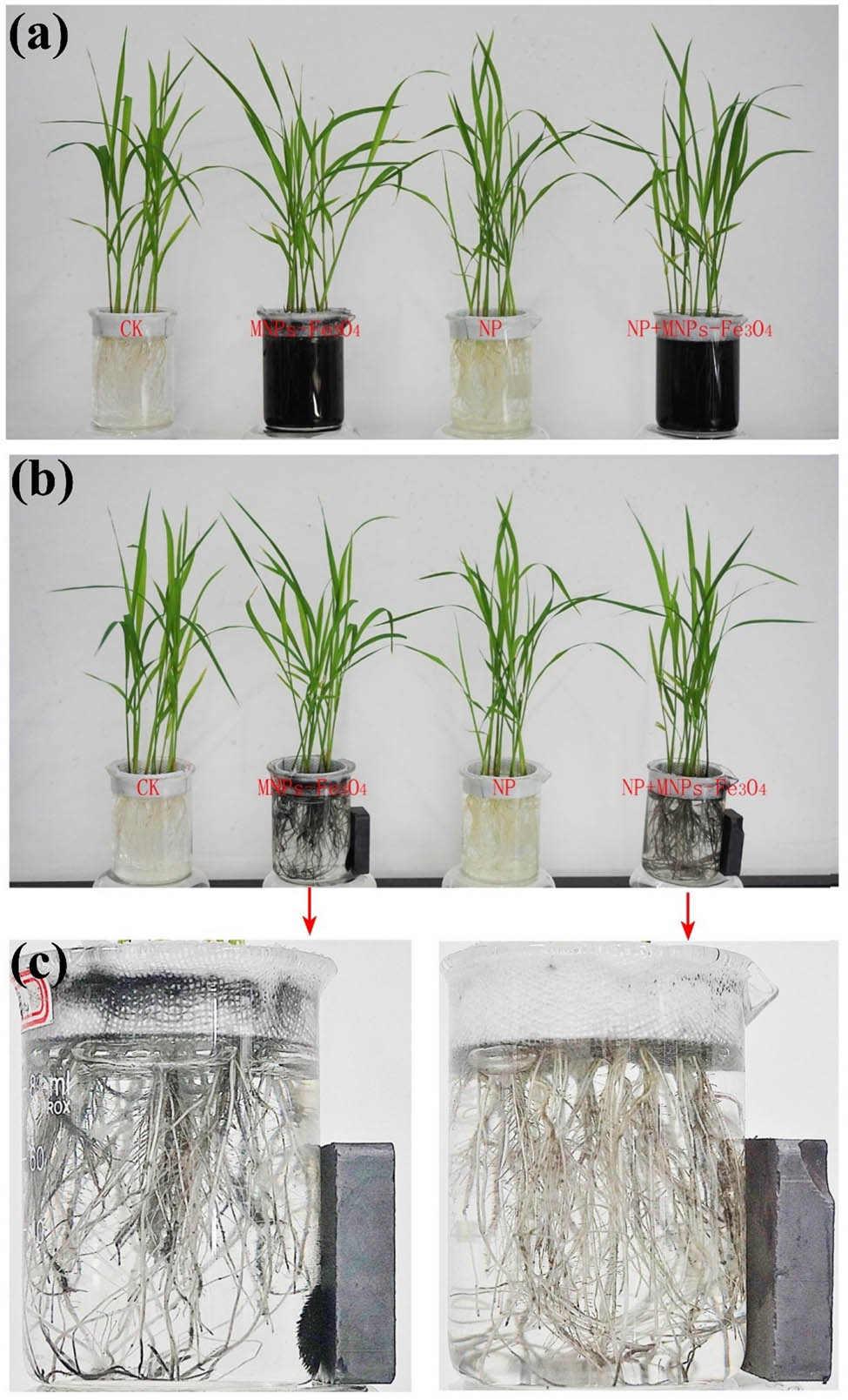

In the second set of experiments, 21-day-old seedlings were subjected to different treatments. In NP, the seedlings received 280 μM NP and were maintained under the above conditions for 5 days. In NP + MNPs-Fe3O4 or MNPs-Fe3O4, the seedlings received 280 μM NP or the solvent alone and were then maintained under the above conditions for 5 h. Afterward, MNPs-Fe3O4 with the final concentration of 2,000 mg L−1 were added to the beaker, and the culture suspension was ultrasonically dispersed (100 W, 40 Hz) for 30 min. After then, a magnet was placed aside for the magnetic separation of MNPs-Fe3O4 (Figure A2). After the separation, the magnet was removed, and the seedlings were cultivated for 5 days under the above conditions. In CK (controls), the seedlings received the solvent alone (i.e., 0 μM NP) and were maintained under the above conditions for 5 days.

In the last set of experiments, MNPs-Fe3O4 were added into the freshly prepared 1/2 strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution with the final concentrations of 100, 500, 1,000, and 2,000 mg L−1, respectively. The freshly prepared 1/2 strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution without MNPs-Fe3O4 was set as the CK (i.e., 0 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4). The MNPs-Fe3O4 suspensions and freshly prepared Hoagland’s nutrient solution above were ultrasonically dispersed (100 W, 40 Hz) for 1 h and were used to replace the Hoagland’s nutrient solution in the beakers, in which rice seedlings had grown for 5 days. The seedlings were grown in the MNPs-Fe3O4 suspension or 1/2 strength of Hoagland’s nutrient solution for 21 days.

2.3 Measurement of the growth of the seedlings

The height of the seedlings was measured as described by Lin et al. [17], and the length of roots of the seedlings was measured as described by Elise et al. [18] by using Image-J. To measure dry weight, the seedlings were washed with distilled water 5–6 times to remove any medium and particles attached to the plant surfaces and then wiped with a sterile filter paper to remove the excess liquid. Afterward, the samples were first dried for 30 min at 100°C and then oven-dried at 70°C until constant weights. After then, the dry weight of above-ground parts, dryweight of below-ground parts, and dry weight of the whole seedlings were determined [19].

2.4 Measurement of chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence

Chlorophyll content was measured according to the method described by Zhang et al. [20] with some modifications. The leaves were homogenized with 4 mL of 80% (v/v) acetone, and the homogenate was then centrifuged at 13,000×g for 20 min at 4°C. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 645 and 663 nm.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were measured according to the method of Zhang et al. [20] by using a portable fluorometer (PAM-2500, Walz, Germany). Y(II) (the effective photochemical quantum yield of PS II) was defined as (Fm′ − Fs)/Fm′, where Fm′ is the maximum fluorescence emission from the light-adapted state measured with a pulse of saturating light, and Fs is the steady-state level of fluorescence emission at the given irradiance. The photochemical quenching (qP) was defined as (Fm′ − Fs)/(Fm′ − Fo′), where Fo′ is the minimal fluorescence of the light-adapted state measured with a far-red pulse. The photosynthetic electron transport rate (ETR) through PS II was calculated as Y(II) × PAR × 0.5 × 0.84.

2.5 Measurement of the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content and the production rate of superoxide anion (

O

2

−

) of roots

The measurement of H2O2 content was performed according to the method of Li et al. [21]. Roots (40 mg) were ground with 0.1% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid, and the homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min. After then, 0.7 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.7 mL of 10 mM phosphate-buffered solution (PBS, pH 7.0) and 1.4 mL of 1 M KI. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 390 nm. H2O2 contents were calculated using a standard curve prepared with the known concentrations of H2O2.

For the measurement of the production rate of

2.6 Antioxidant enzyme activities

The roots (50 mg) were ground with 1 mL of chilled 50 mM PBS (pH 7.8) containing 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000×g for 30 min, and the supernatant (as enzyme extraction) was collected to determine the activities of antioxidant enzymes [21].

The superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured by the method of Dhindsa and Matowe [23] with some modifications. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM PBS (pH 7.6), 13 mM methionine, 75 mM NBT, 0.1 mM EDTA-Na2, and an appropriate amount of enzyme extraction. The reaction was started by the addition of 2 mM lactochrome. After illumination for 30 min at 25°C, the absorbance was recorded at 560 nm. The activity of SOD was expressed in unit mg−1 of fresh weight (Fw).

The peroxidase (POD) activity was measured following the method of Rao et al. [24] with some modifications. The enzyme extraction was mixed with 3 mL of the reaction medium containing 50 mM PBS (pH 7.0) and 20 mM guaiacol. After incubation at 25°C for 5 min, 6 mM H2O2 was added to initiate the reaction. The absorbance changes at 470 nm within 2 min were recorded to calculate the POD activity. The POD activity was expressed in ΔOD470 min−1 mg−1 Fw.

The catalase (CAT) activity was measured by the method of Zhang et al. [20] with some modifications. The enzyme extraction was added to 3 mL of 50 mM PBS (pH 7.0) and incubated at 25°C for 5 min. After that, the reaction was started by adding 6 mM H2O2, and the absorbance changes were recorded at 240 nm for 2 min. The CAT activity was expressed in ΔOD240 min−1mg−1 Fw.

For the measurement of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity, the roots (20 mg) were ground with 1 mL of 50 mM PBS (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM EDTA-Na2 and 1 mM ascorbate (ASA). After centrifugation for 20 min at 10,000×g, the supernatant was collected to measure the APX activity according to the method of Nakano and Asada [25] with some modifications. The assay was carried out in a reaction mixture consisting of 50 mM PBS (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM ASA, 3 mM H2O2, and the right amount of enzyme extraction. The changes in the absorbance at 290 nm were recorded at 25°C for 2 min after the addition of H2O2. The APX activity was expressed in ΔOD290 min−1 mg−1 Fw.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent replicates. Statistical analysis was evaluated with t-test methods. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 The effects of NP on the growth of the seedlings

The level of the growth of the seedlings was expressed by measuring the seedling height (SH), length of root (LR), dry weight of below-ground part (DWB), dry weight of above-ground part (DWA), and dry weight of whole seedlings (DWW). As shown in Table 1, the stress of NP decreased the values of SH, LR, DWB, DWA, and DWW. When the concentration of NP reached 280 µM, SH, LR, DWB, DWA, and DWW were significantly decreased by 37.4, 25.7, 27.3, 24.5, and 15.9%, respectively, compared to the controls. The decreases in these parameters were further aggravated after the seedlings were treated with 560 µM NP.

The effects of NP on SH, LR, DWB, DWA, and DWW

| NP concentrations (µM) | SH (mm) | LR (mm) | DWA (g) | DWB (g) | DWW (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 142.233 ± 9.899a | 88.181 ± 12.310a | 0.049 ± 0.0016a | 0.022 ± 0.0019a | 0.063 ± 0.0015a |

| 70 | 134.999 ± 11.833ab | 83.450 ± 11.707ab | 0.045 ± 0.0022ab | 0.021 ± 0.0015a | 0.061 ± 0.0021a |

| 140 | 122.705 ± 17.187b | 75.929 ± 8.557b | 0.042 ± 0.0010b | 0.018 ± 0.0011b | 0.059 ± 0.0017a |

| 280 | 89.086 ± 7.791c | 65.491 ± 4.629c | 0.037 ± 0.0017c | 0.016 ± 0.0005c | 0.053 ± 0.0011b |

| 560 | 54.839 ± 4.256d | 61.879 ± 6.268c | 0.021 ± 0.0014d | 0.012 ± 0.0016d | 0.035 ± 0.0044c |

Each value represents the mean ± SD of three individual replications at least.

Different small letters in superscript indicate a significant difference (at P < 0.05 levels) of the same parameter among the seedlings treated with different concentrations of NP.

3.2 Effect of NP on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and chlorophyll content of the seedlings

As shown in Table 2, the values of the effective quantum yield of PSII photochemistry (Y(II)), photochemical quenching (qP), electron transport rate (ETR), and chlorophyll content were decreased with the increase in NP concentrations. The chlorophyll content was also decreased with the increase in NP concentrations. Compared to the controls, the chlorophyll content was decreased by 15.97, 25.91, 39.29, and 48.69%, respectively, after treatment with 70, 140, 280, and 560 µM NP (Table 2).

Effect of NP stress on the Y(II), qP, ETR, and chlorophyll content of the rice seedlings

| NP concentrations (µM) | Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters | Chlorophyll content (mg g−1 Fw) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y(II) | qP | ETR | ||

| 0 | 0.361 ± 0.006a | 0.747 ± 0.037a | 24.012 ± 0.428a | 2.980 ± 0.114a |

| 70 | 0.365 ± 0.011a | 0.739 ± 0.033a | 24.308 ± 0.765a | 2.504 ± 0.129b |

| 140 | 0.317 ± 0.005b | 0.605 ± 0.036b | 18.679 ± 1.034b | 2.208 ± 0.158c |

| 280 | 0.251 ± 0.008c | 0.431 ± 0.045c | 16.619 ± 0.320c | 1.809 ± 0.053d |

| 560 | 0.156 ± 0.025d | 0.399 ± 0.028c | 11.527 ± 0.493d | 1.529 ± 0.111e |

Each value represents the mean ± SD of three individual replications at least. Different small letters in superscript indicate a significant difference (at P < 0.05) of the same parameter among the seedlings treated with different concentrations of NP.

3.3 Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the growth of the seedlings under NP stress

We further studied whether the MNPs-Fe3O4 in the growth medium can alleviate NP-induced physiological stresses to rice seedlings. We concentrated on the seedlings subjected to 280 μM NP, since NP at this concentration caused the significant changes in all parameters measured (Tables 1 and 2).

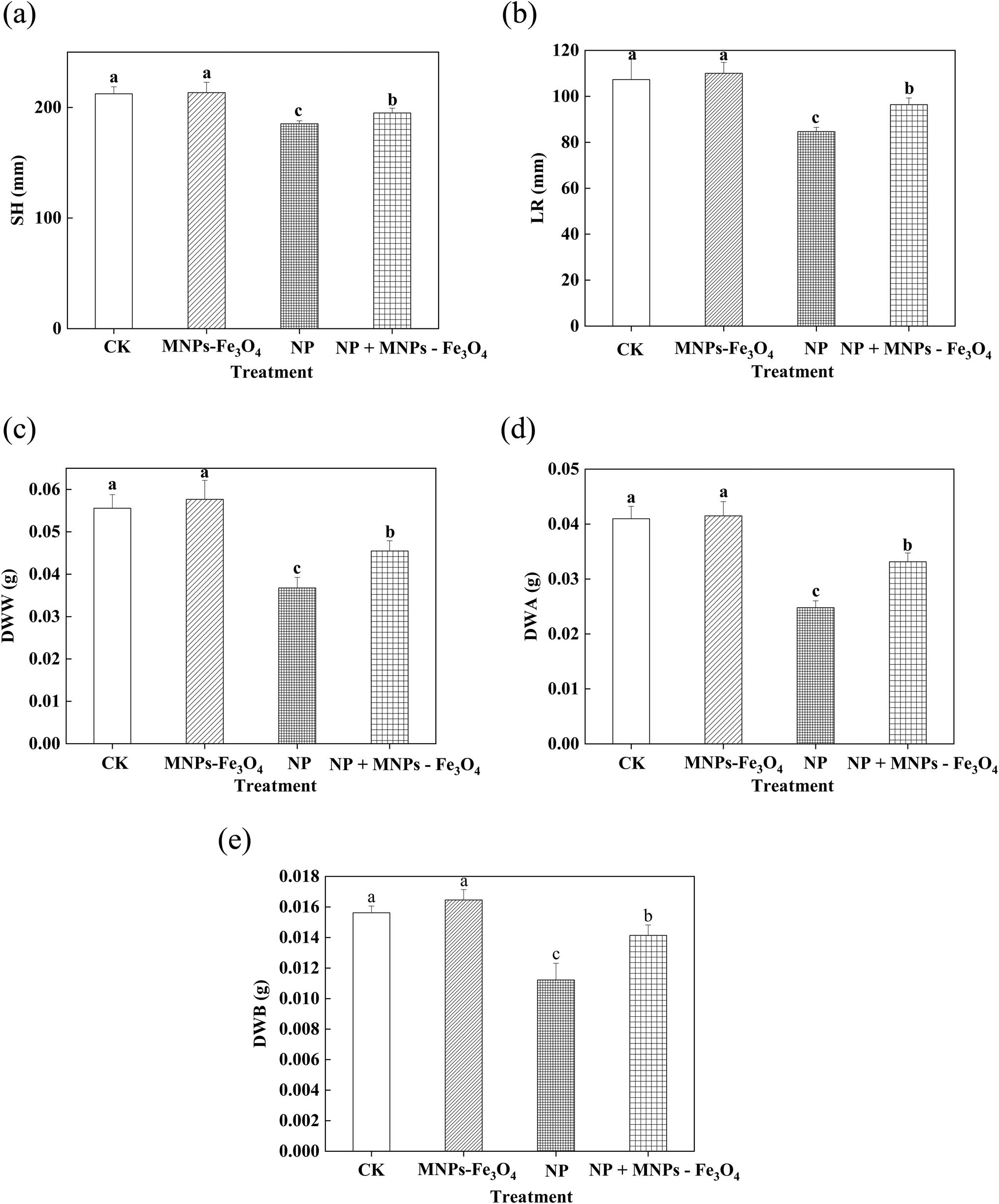

The growth of rice seedlings was significantly reduced after the treatment with 280 µM NP, whereas the presence of MNPs-Fe3O4 in the growth medium effectively alleviated the NP-induced reduction of growth of the seedlings. This was reflected by the observations that the value of SH, LR, DWW, DWA, and DWB of the seedlings exposed to NP + MNPs-Fe3O4 was significantly increased by 1.05-, 1.14-, 1.24-, 1.34-, and 1.26-fold, respectively, compared to the seedlings exposed to NP alone (Figure 1).

Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the SH (a), LR (b), DWW (c), DWA (d), and DWB (e) under NP stress. CK: treatment with received the solvent alone as the controls; MNPs-Fe3O4: treatment with magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (2,000 mg L−1); NP: treatment with NP (280 µM); and NP + MNPs-Fe3O4: treatment with a combination of NP (280 µM) and magnetic (Fe3O4) nanoparticles (2,000 mg L−1). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three individual replications at least. Different small letters indicate a significant difference (at P < 0.05) among the different treatments.

3.4 Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the photochemical activity of PS II and chlorophyll content of the seedlings under NP stress

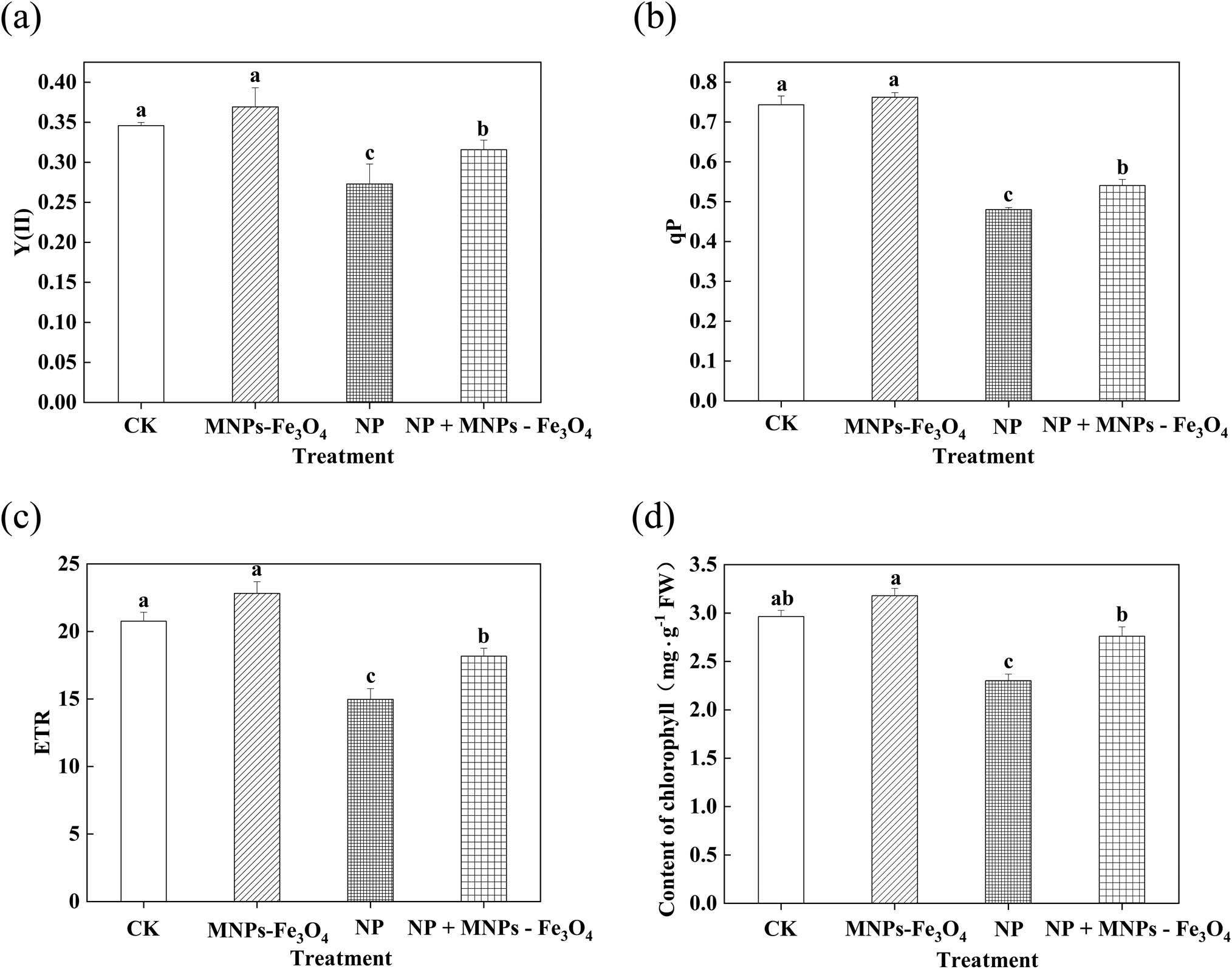

Compared with the controls, the values of Y(II), qP, ETR, and chlorophyll content were significantly decreased under NP stress. However, the values of Y(II), qP, ETR, and chlorophyll content of the seedlings were significantly increased by the treatment with NP + MNPs-Fe3O4, compared with the seedlings exposed to the NP treatment alone (Figure 2) (Y(II), qP, ETR, and chlorophyll content were increased by 1.16-, 1.13-, 1.21-, and 1.19-fold, respectively).

Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the Y(II) (a), qP (b), ETR (c), and chlorophyll content (d) of the rice seedlings under NP stress. CK: treatment with received the solvent alone as the controls; MNPs-Fe3O4: treatment with magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (2,000 mg L−1); NP: treatment with NP (280 µM); and NP + MNPs-Fe3O4: treatment with combination of NP (280 µM) and magnetic (Fe3O4) nanoparticles (2,000 mg L−1). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three individual replications at least. Different small letters indicate a significant difference (at P < 0.05) among the different treatments.

3.5 Effects of long-term presence of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the growth of the seedlings

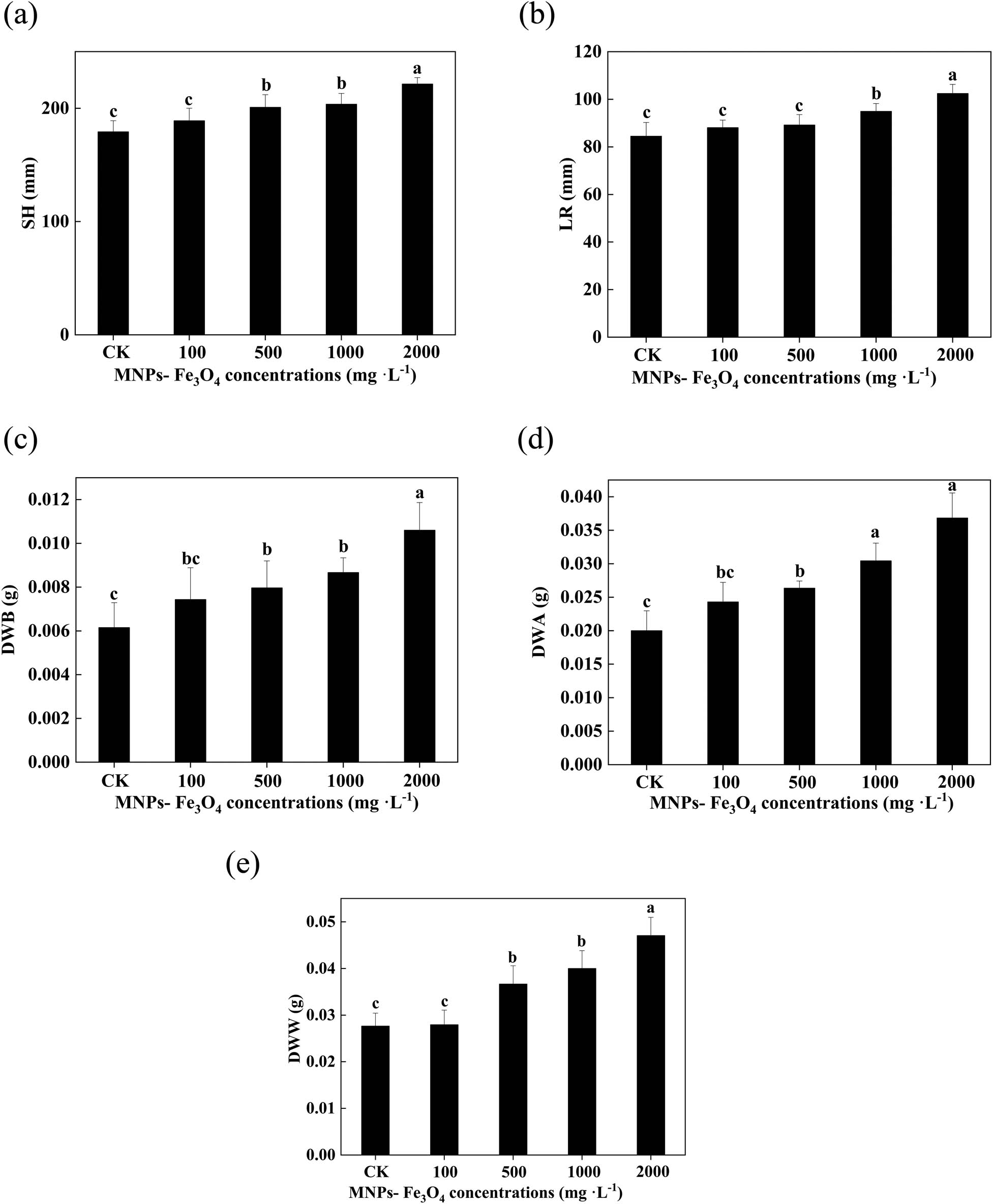

In comparison with the controls, treatment with 100 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4 did not significantly affect the growth of the seedlings. With the further increase in concentrations of MNPs-Fe3O4, the values of SH, LR, DWB, DWA, and DWW were gradually increased (Figure 3). Treatment with 2,000 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4 caused the most noticeable increase in seedling growth. Compared to the controls, the values of SH, LR, DWB, DWA, and DWW were increased by 1.24-, 1.21-, 1.84-, 1.72-, and 1.70-fold, respectively, after treatment with 2,000 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4.

Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the SH (a), LR (b), DWB (c), DWA (d), and DWW (e). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three individual replications at least. Different small letters indicate a significant difference (at P < 0.05) among the seedlings treated with different concentrations of MNPs-Fe3O4.

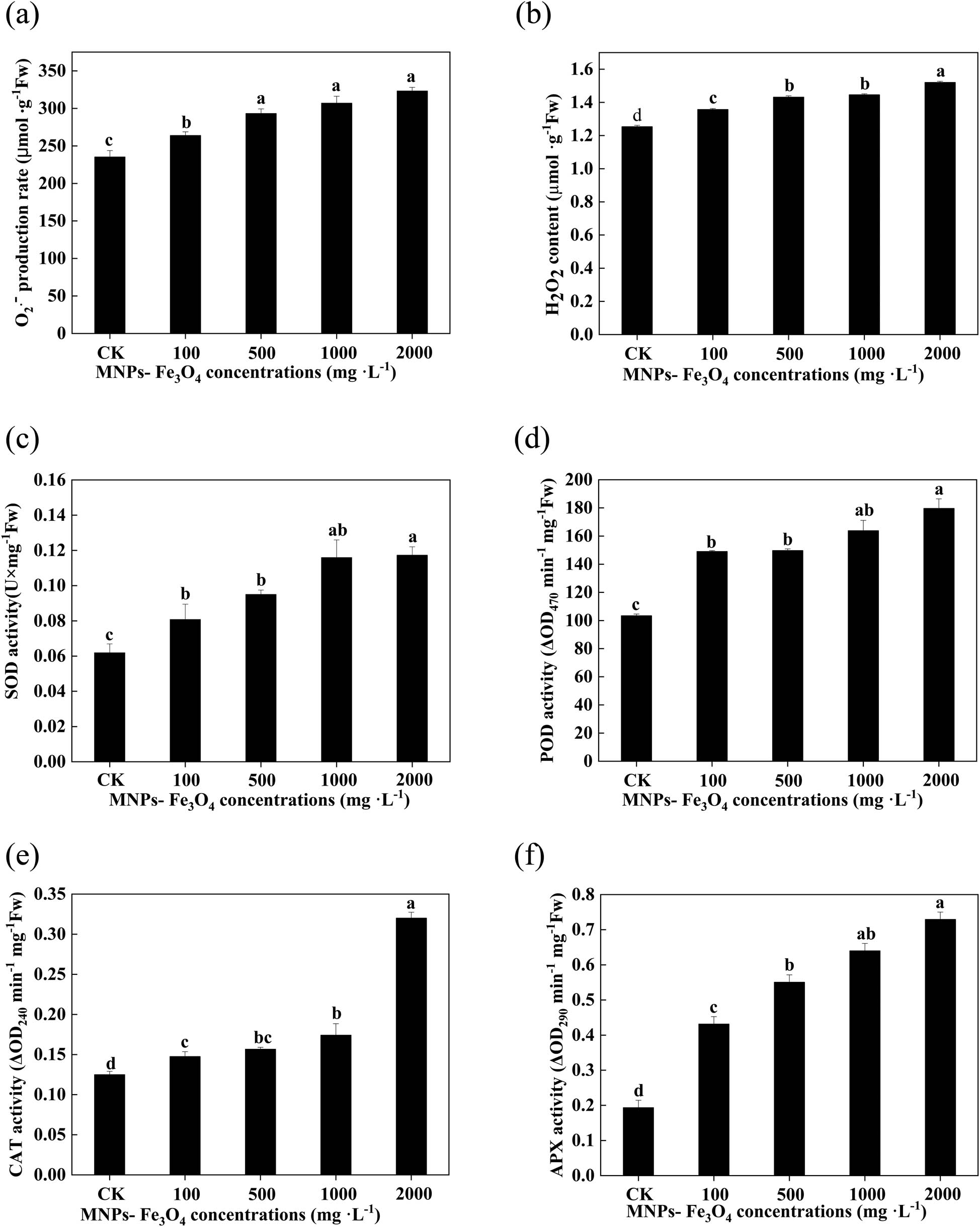

3.6 Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activities of antioxidant enzymes of the seedling roots.

The production rate of

Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the production rate of superoxide anion (

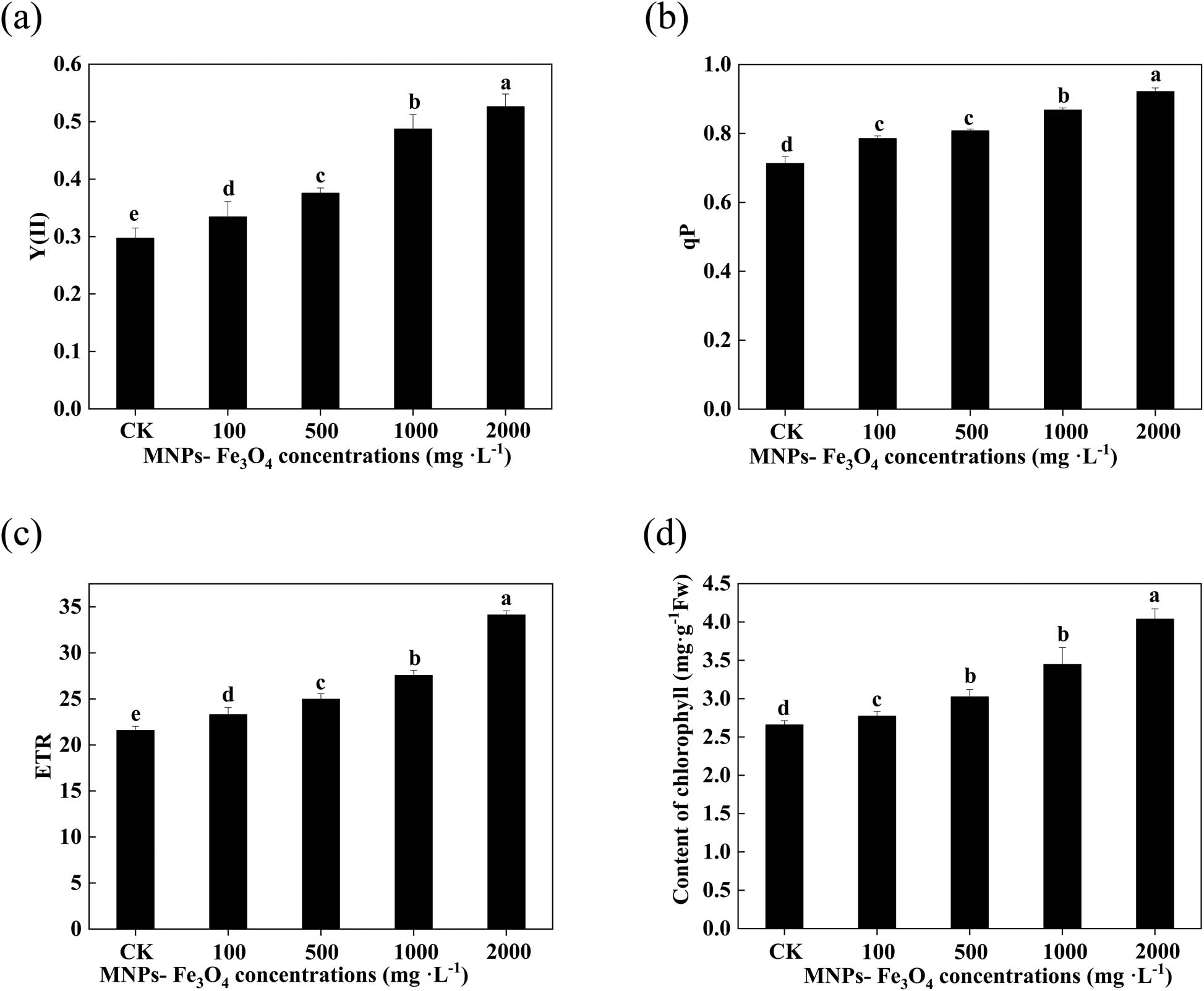

3.7 Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the photochemical activity of PS II and chlorophyll content of the seedlings

Treatment with 100–2,000 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4 significantly increased the values of Y(II), qP, and ETR of the leaves of the seedlings (Figure 5a–c). Simultaneously, the chlorophyll content was also increased with the increase in concentrations of MNPs-Fe3O4 (Figure 5d).

Effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on Y(II) (a), qP (b), ETR (c), and chlorophyll content (d) of the rice seedlings. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three individual replications at least. Different small letters indicate a significant difference (at P < 0.05) among the seedlings treated with different concentrations of NP.

4 Discussion

It is well known that organic contaminants can inhibit the plant growth [26]. In the present study, the growth of rice seedlings was significantly inhibited by NP stress (Table 1). Photosynthesis is one of the most important metabolic processes of plants. The primary step of photosynthesis is to absorb light and transfer excitation energy to the reaction centers of PSII to drive the primary photochemical reactions. Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence provides a rapid and sensitive mean for detecting the photochemical activity of PSII [27,28]. The inhibition of growth by NP stress was observed to be followed by decreases in Y(II), ETR, qP, and chlorophyll content (Table 2). These observations are in agreement with the findings of Zhang et al. [29] and Liu et al. [30], who revealed that NPs could reduce the growth, photosynthesis, and biosynthesis of chlorophyll in plants.

Although the application of nanoparticles as adsorbents provides a convenient method to remove the contaminants from the waterbody, the accumulation and remnants of the nanoparticles could lead to potential contamination [31]. Compared to common nanomaterials, the magnetic properties of MNPs-Fe3O4 allow easy separation of the nanoparticles from water in the presence of an external magnetic field [15]. Therefore, in the present work, MNPs-Fe3O4 were employed as the absorbents of NP and then were separated with magnet rice seedlings. Under NP stress, such application of MNPs-Fe3O4 significantly alleviated the NP-induced adverse effects on growth, photochemical reactions, and biosynthesis of chlorophyll of rice seedlings (Figures 1 and 2). Thus, it is suggested that MNPs-Fe3O4 may reduce the accumulation of NP in the seedlings by absorbing NP, thus effectively alleviating the toxicity of NP to the seedlings.

Although significant amounts of MNPs-Fe3O4 were separated from the growth medium through a magnet, small amounts of MNPs- Fe3O4 were still left in the growth medium (Figure A2). Thus, one can speculate that the residual MNPs-Fe3O4 could negatively affect the plants. Hence, to address such concern for environmental biosafety, we further evaluated the effects of long-term presence (during 21 days of growth of rice seedlings) of MNPs-Fe3O4 on the rice seedlings. The results showed that MNPs-Fe3O4 could enhance the growth, increase the ROS production and activities of antioxidant enzymes, and improve the photochemical activity of PS II and chlorophyll content (Figures 3–5). Such observations indicate that MNPs-Fe3O4 can limit the toxicity of NP to plants and improve the growth of plants.

Although the MNPs-Fe3O4 are not endogenous substances of plants, many reports available showed that MNPs-Fe3O4 could exert multiple positive effects on plants. It has been found that the dissolved iron ions from MNPs-Fe3O4 can increase the supply of Fe-ion, which is an advantageous component for plant growth and is required for many physiological processes of plants, such as chlorophyll biosynthesis [32,33,34]. Other works reported that the application of MNPs-Fe3O4 can enhance the absorption of other nutrients elements, such as calcium, potassium, and magnesium, in plants [35,36,37]. It is well known that ROS can act as important signal molecules in positively regulating plant growth, and antioxidant enzymes can protect the plant cell from damage from external environments [38]. In agreement with our results (Figure 4), many works revealed that MNPs-Fe3O4 could increase ROS production and stimulate the activities of antioxidant enzymes [39,40]. Thus, MNPs-Fe3O4 are thought to motivate the variations in plants’ defense mechanisms in response to environmental stresses by modulating ROS production and antioxidant status [41].

In theory, besides MNPs-Fe3O4, other types of magnetic nanoparticles can be used as additives to relieve the NP-induced stress on plants and can be separated by the magnetic field. However, it should be noted that different magnetic nanoparticles could have different effects on plants. For example, Tombuloglu et al. [42] found that manganese ferrite (MnFe2O4) nanoparticles at higher concentrations (250 or 1,000 mg L−1) remarkably decreased the dry weight of the leaf of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) seedlings. In comparison, our present work showed that MNPs-Fe3O4 at higher concentrations (500–2,000 mg L−1) enhanced the dry weight of the below-ground part of rice seedlings. Such discrepancy may be attributed to the presence of Mn in the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles that could exert additional effects on the plants when higher concentrations of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were applied since Mn is one of the heavy metals that can be harmful to plants at excessive levels [43]. Thus, the composition of elements in magnetic nanoparticles should be considered an important factor for more secure application, especially when a high dose of magnetic nanoparticles would be used.

In conclusion, the present result showed that the NP stress decreased the growth, photochemical activity of PS II, and chlorophyll content of the rice seedlings. Such toxicity of NP to the seedlings can be effectively alleviated by the addition of MNPs-Fe3O4 into the growth medium, followed by separation via the magnetic field. Furthermore, the long-term presence of MNPs-Fe3O4 in the growth medium positively affected the seedlings. These results indicate that MNPs-Fe3O4 could be used as a potential additive to relieve the NP-induced toxicity to plants. Future studies are expected to reveal whether MNPs-Fe3O4 could be used to cope with the simultaneous threat of inorganic and organic contaminants to plants. Moreover, research on biochemical and molecular levels is also needed for a deeper insight to understand the mechanism for the effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on plants.

-

Funding information: This study found by Special Fund for Guiding Scientific and Technological Innovation Development of Gansu Province (Grant Number 2019ZX‑05), Major project of science and technology plan of Gansu Province (No: 22ZD1NA001), the Open Fund of New Rural Development Institute of Northwest Normal University, National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31560070 and 31870246), the Key Research and Development Project of Gansu Province (No. 18YF1NA051), Fundamental Research Funds for the Gansu Universities of Gansu Provincial Department of Finance, and Youth Teacher Scientific Research Ability Promotion Plan Innovation Team Project of Northwest Normal University.

-

Author contributions: H.F. conceived the project and designed the experiments. W.S., Z.S., and H.P. performed the experiments and the data analysis. H.F. and W.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix

The characterization of MNPs-Fe3O4 used in this study. (a) Photo-images of MNPs-Fe3O4. (b) Transmission-electron micrographs of the MNPs-Fe3O4. (c) Elemental analysis of MNPs-Fe3O4.

The scheme of experimental processing for evaluating the alleviative effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 on toxicity of NP to rice seedlings. (a) The rice seedlings were subjected to different treatments. CK: controls (the seedlings that received the solvent of NP solution only); MNPs-Fe3O4: the seedlings that received 2,000 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4; NP: the seedlings that received 280 µM NP; NP + MNPs-Fe3O4: the seedlings that received 280 µM NP plus 2,000 mg L−1 MNPs-Fe3O4. (b) After the rice seedlings were treated as described above, MNPs-Fe3O4 were separated with magnet. (c) The enlarged image of magnetic separation of MNPs-Fe3O4 by magnet.

The scheme of experimental processing for evaluating the effects of MNPs-Fe3O4 at different concentrations on rice seedlings. Red letters indicate that the final concentration that was received by the rice seedlings. CK: the seedlings without treatment with MNPs-Fe3O4 were used as the controls).

References

[1] Wu Z, Yuan X, Zhong H, Wang H, Zeng G, Chen X, et al. Enhanced adsorptive removal of p-nitrophenol from water by aluminum metal–organic framework/reduced graphene oxide composite. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–13.10.1038/srep25638Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Boehncke A, Koennecker G, Mangelsdorf I, Wibbertmann A. Mononitrophenols, concise international chemical assessment document 20. Geneva: WHO; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[3] She Z, Gao M, Jin C, Chen Y, Yu J. Toxicity and biodegradation of 2, 4-dinitrophenol and 3-nitrophenol in anaerobic systems. Process Biochem. 2005;40(9):3017–24.10.1016/j.procbio.2005.02.007Search in Google Scholar

[4] Assi N, Mohammadi A, Sadr Manuchehri Q, Walker RB. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticle synthesized by a microwave-assisted combustion method and catalytic activity for the removal of ortho-nitrophenol. Desalin Water Treat. 2015;54(7):1939–48.10.1080/19443994.2014.891083Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lesser LE, Mora A, Moreau C, Mahlknecht J, Hernández-Antonio A, Ramírez AI, et al. Survey of 218 organic contaminants in groundwater derived from the world’s largest untreated wastewater irrigation system: Mezquital Valley, Mexico. Chemosphere. 2018;198:510–21.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.01.154Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Li C, Wu Z, Yang H, Deng L, Chen X. Reduced graphene oxide-cyclodextrin-chitosan electrochemical sensor: Effective and simultaneous determination of o-and p-nitrophenols. Sensors Actuat B Chem. 2017;251:446–54.10.1016/j.snb.2017.05.059Search in Google Scholar

[7] Adrees M, Ali S, Rizwan M, Ibrahim M, Abbas F, Farid M, et al. The effect of excess copper on growth and physiology of important food crops: a review. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2015;22(11):8148–62.10.1007/s11356-015-4496-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Devi P, Saroha AK. Utilization of sludge based adsorbents for the removal of various pollutants: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2017;578:16–33.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.220Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ahmad T, Rafatullah M, Ghazali A, Sulaiman O, Hashim R, Ahmad A. Removal of pesticides from water and wastewater by different adsorbents: a review. J Environ Sci Health C. 2010;28(4):231–71.10.1080/10590501.2010.525782Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Nowack B, Bucheli TD. Occurrence, behavior and effects of nanoparticles in the environment. Environ Pollut. 2007;150(1):5–22.10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Roco MC. Broader societal issues of nanotechnology. J Nanopart Res. 2003;5(3):181–9.10.1023/A:1025548512438Search in Google Scholar

[12] Roco MC. International perspective on government nanotechnology funding in 2005. J Nanopart Res. 2005;7(6):707–12.10.1007/s11051-005-3141-5Search in Google Scholar

[13] Seenuvasan M, Vinodhini G, Malar CG, Balaji N, Kumar KS. Magnetic nanoparticles: a versatile carrier for enzymes in bio-processing sectors. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018;12(5):535–48.10.1049/iet-nbt.2017.0041Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Chen X, Zhang Z, Li X, Shi C. Hollow magnetite spheres: synthesis, characterization, and magnetic properties. Chem Phys Lett. 2006;422(1–3):294–8.10.1016/j.cplett.2006.02.082Search in Google Scholar

[15] Chen D, Awut T, Liu B, Ma Y, Wang T, Nurulla I. Functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions. e-Polymers. 2016;16(4):313–22.10.1515/epoly-2016-0043Search in Google Scholar

[16] Rico CM, Morales MI, Barrios AC, McCreary R, Hong J, Lee WY, et al. Effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the quality of rice (Oryza sativa L.) grains. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(47):11278–85.10.1021/jf404046vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Lin Y-R, Schertz KF, Paterson AH. Comparative analysis of QTLs affecting plant height and maturity across the Poaceae, in reference to an interspecific sorghum population. Genetics. 1995;141(1):391–411.10.1093/genetics/141.1.391Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Elise S, Etienne-Pascal J, Fernanda dC-N, Gérard D, Julia F. The Medicago truncatula SUNN gene encodes a CLV1-like leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase that regulates nodule number and root length. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;58(6):809–22.10.1007/s11103-005-8102-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Demiral T, Türkan I. Comparative lipid peroxidation, antioxidant defense systems and proline content in roots of two rice cultivars differing in salt tolerance. Environ Exp Bot. 2005;53(3):247–57.10.1016/j.envexpbot.2004.03.017Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zhang M, Ran R, Nao WS, Feng Y, Jia L, Sun K, et al. Physiological effects of short-term copper stress on rape (Brassica napus L.) seedlings and the alleviation of copper stress by attapulgite clay in growth medium. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;171(30):878–86.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.01.014Search in Google Scholar

[21] Li X, Yang Y, Jia L, Chen H, Wei X. Zinc-induced oxidative damage, antioxidant enzyme response and proline metabolism in roots and leaves of wheat plants. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2013;89(11):150–7.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.11.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Achary VMM, Jena S, Panda KK, Panda BB. Aluminium induced oxidative stress and DNA damage in root cells of Allium cepa L. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2008;70(2):300–10.10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.10.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Dhindsa RS, Matowe W. Drought tolerance in two mosses: correlated with enzymatic defence against lipid peroxidation. J Exp Bot. 1981;32(1):79–91.10.1093/jxb/32.1.79Search in Google Scholar

[24] Rao MV, Paliyath G, Ormrod DP. Ultraviolet-B-and ozone-induced biochemical changes in antioxidant enzymes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1996;110(1):125–36.10.1104/pp.110.1.125Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22(5):867–80.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Kummerová M, Zezulka Š, Váňová L, Fišerová H. Effect of organic pollutant treatment on the growth of pea and maize seedlings. Open Life Sci. 2012;7(1):159–66.10.2478/s11535-011-0081-1Search in Google Scholar

[27] Baker NR, Rosenqvist E. Applications of chlorophyll fluorescence can improve crop production strategies: an examination of future possibilities. J Exp Bot. 2004;55(403):1607–21.10.1093/jxb/erh196Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Calatayud A, Roca D, Martínez PF. Spatial-temporal variations in rose leaves under water stress conditions studied by chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006;44(10):564–73.10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.09.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Zhang B, Chu G, Wei C, Ye J, Lei B, Li Z, et al. Physiological and biochemical response of wheat seedlings to organic pollutant 1, 2, 4-trichlorobenzene. N Z J Crop Hortic Sci. 2012;40(2):73–85.10.1080/01140671.2011.610324Search in Google Scholar

[30] Liu H, Weisman D, Ye Y-B, Cui B, Huang Y-H, Colón-Carmona A, et al. An oxidative stress response to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure is rapid and complex in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 2009;176(3):375–82.10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.12.002Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zadeh RJ, Sayadi MH, Rezaei MR. Removal of 2, 4‐dichlorophenoxyacetic acid from aqueous solutions by modified magnetic nanoparticles with amino functional groups. J Water Environ Nanotechnol. 2020;5:147.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ghafariyan MH, Malakouti MJ, Dadpour MR, Stroeve P, Mahmoudi M. Effects of magnetite nanoparticles on soybean chlorophyll. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(18):10645–52.10.1021/es402249bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Ren HX, Liu L, Liu C, He S, Huang J, Li J, et al. Physiological investigation of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles towards Chinese mung bean. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7(5):677–84.10.1166/jbn.2011.1338Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Wang H, Kou X, Pei Z, Xiao JQ, Shan X, Xing B. Physiological effects of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles on perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) and pumpkin (Cucurbita mixta) plants. Nanotoxicology. 2011;5(1):30–42.10.3109/17435390.2010.489206Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Askary M, Talebi SM, Amini F, Bangan ADB. Effects of iron nanoparticles on Mentha piperita L. under salinity stress. Biologija. 2017;63(1):65–75.10.6001/biologija.v63i1.3476Search in Google Scholar

[36] Jalali M, Ghanati F, Modarres-Sanavi AM. Effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles and iron chelate on the antioxidant capacity and nutritional value of soil-cultivated maize (Zea mays) plants. Crop Pasture Sci. 2016;67(6):621–8.10.1071/CP15271Search in Google Scholar

[37] Li J, Hu J, Ma C, Wang Y, Wu C, Huang J, et al. Uptake, translocation and physiological effects of magnetic iron oxide (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles in corn (Zea mays L.). Chemosphere. 2016;159:326–34.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.05.083Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Swanson S, Gilroy S. ROS in plant development. Physiol Plant. 2010;138(4):384–92.10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01313.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Arruda SCC, Silva ALD, Galazzi RM, Azevedo RA, Arruda MAZ. Nanoparticles applied to plant science: a review. Talanta. 2015;131:693–705.10.1016/j.talanta.2014.08.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Ma C, White JC, Dhankher OP, Xing B. Metal-based nanotoxicity and detoxification pathways in higher plants. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(12):7109–22.10.1021/acs.est.5b00685Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Yan L, Li P, Zhao X, Ji R, Zhao L. Physiological and metabolic responses of maize (Zea mays) plants to Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Sci Total Environ. 2020;718:137400.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137400Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Tombuloglu H, Tombuloglu G, Slimani Y, Ercan I, Sozeri H, Baykal A. Impact of manganese ferrite (MnFe2O4) nanoparticles on growth and magnetic character of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Environ Pollut. 2018;243:872–81.10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.096Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Asati A, Pichhode M, Nikhil K. Effect of heavy metals on plants: an overview. IJAIEM. 2016;5(3):56–66.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Wangqing Sainao et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Effects of direct oral anticoagulants dabigatran and rivaroxaban on the blood coagulation function in rabbits

- The mother of all battles: Viruses vs humans. Can humans avoid extinction in 50–100 years?

- Knockdown of G1P3 inhibits cell proliferation and enhances the cytotoxicity of dexamethasone in acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- LINC00665 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating mRNA via the m6A enzyme

- Association study of CLDN14 variations in patients with kidney stones

- Concanavalin A-induced autoimmune hepatitis model in mice: Mechanisms and future outlook

- Regulation of miR-30b in cancer development, apoptosis, and drug resistance

- Informatic analysis of the pulmonary microecology in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis at three different stages

- Swimming attenuates tumor growth in CT-26 tumor-bearing mice and suppresses angiogenesis by mediating the HIF-1α/VEGFA pathway

- Characterization of intestinal microbiota and serum metabolites in patients with mild hepatic encephalopathy

- Functional conservation and divergence in plant-specific GRF gene family revealed by sequences and expression analysis

- Application of the FLP/LoxP-FRT recombination system to switch the eGFP expression in a model prokaryote

- Biomedical evaluation of antioxidant properties of lamb meat enriched with iodine and selenium

- Intravenous infusion of the exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells enhance neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury via suppressing the NF-κB pathway

- Effect of dietary pattern on pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus and its clinical significance

- Potential regulatory mechanism of TNF-α/TNFR1/ANXA1 in glioma cells and its role in glioma cell proliferation

- Effect of the genetic mutant G71R in uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 on the conjugation of bilirubin

- Quercetin inhibits cytotoxicity of PC12 cells induced by amyloid-beta 25–35 via stimulating estrogen receptor α, activating ERK1/2, and inhibiting apoptosis

- Nutrition intervention in the management of novel coronavirus pneumonia patients

- circ-CFH promotes the development of HCC by regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, and glycolysis through the miR-377-3p/RNF38 axis

- Bmi-1 directly upregulates glucose transporter 1 in human gastric adenocarcinoma

- Lacunar infarction aggravates the cognitive deficit in the elderly with white matter lesion

- Hydroxysafflor yellow A improved retinopathy via Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in rats

- Comparison of axon extension: PTFE versus PLA formed by a 3D printer

- Elevated IL-35 level and iTr35 subset increase the bacterial burden and lung lesions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice

- A case report of CAT gene and HNF1β gene variations in a patient with early-onset diabetes

- Study on the mechanism of inhibiting patulin production by fengycin

- SOX4 promotes high-glucose-induced inflammation and angiogenesis of retinal endothelial cells by activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Relationship between blood clots and COVID-19 vaccines: A literature review

- Analysis of genetic characteristics of 436 children with dysplasia and detailed analysis of rare karyotype

- Bioinformatics network analyses of growth differentiation factor 11

- NR4A1 inhibits the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells: Involvement of TGF-β–Smad2/3/4–ZEB signaling

- Expression of Zeb1 in the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cell

- Study on the genetic damage caused by cadmium sulfide quantum dots in human lymphocytes

- Association between single-nucleotide polymorphisms of NKX2.5 and congenital heart disease in Chinese population: A meta-analysis

- Assessment of the anesthetic effect of modified pentothal sodium solution on Sprague-Dawley rats

- Genetic susceptibility to high myopia in Han Chinese population

- Potential biomarkers and molecular mechanisms in preeclampsia progression

- Silencing circular RNA-friend leukemia virus integration 1 restrained malignancy of CC cells and oxaliplatin resistance by disturbing dyskeratosis congenita 1

- Endostar plus pembrolizumab combined with a platinum-based dual chemotherapy regime for advanced pulmonary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma as a first-line treatment: A case report

- The significance of PAK4 in signaling and clinicopathology: A review

- Sorafenib inhibits ovarian cancer cell proliferation and mobility and induces radiosensitivity by targeting the tumor cell epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- Characterization of rabbit polyclonal antibody against camel recombinant nanobodies

- Active legumain promotes invasion and migration of neuroblastoma by regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- Effect of cell receptors in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Current insights

- MT-12 inhibits the proliferation of bladder cells in vitro and in vivo by enhancing autophagy through mitochondrial dysfunction

- Study of hsa_circRNA_000121 and hsa_circRNA_004183 in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma

- BuyangHuanwu Decoction attenuates cerebral vasospasm caused by subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats via PI3K/AKT/eNOS axis

- Effects of the interaction of Notch and TLR4 pathways on inflammation and heart function in septic heart

- Monosodium iodoacetate-induced subchondral bone microstructure and inflammatory changes in an animal model of osteoarthritis

- A rare presentation of type II Abernethy malformation and nephrotic syndrome: Case report and review

- Rapid death due to pulmonary epithelioid haemangioendothelioma in several weeks: A case report

- Hepatoprotective role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α in non-cancerous hepatic tissues following transcatheter arterial embolization

- Correlation between peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations and primary systemic lupus erythematosus

- A novel SLC8A1-ALK fusion in lung adenocarcinoma confers sensitivity to alectinib: A case report

- β-Hydroxybutyrate upregulates FGF21 expression through inhibition of histone deacetylases in hepatocytes

- Identification of metabolic genes for the prediction of prognosis and tumor microenvironment infiltration in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer

- BTBD10 inhibits glioma tumorigenesis by downregulating cyclin D1 and p-Akt

- Mucormycosis co-infection in COVID-19 patients: An update

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing in diagnosing Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: A case report

- Long non-coding RNA HOXB-AS1 is a prognostic marker and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cells’ proliferation and invasion

- Preparation and evaluation of LA-PEG-SPION, a targeted MRI contrast agent for liver cancer

- Proteomic analysis of the liver regulating lipid metabolism in Chaohu ducks using two-dimensional electrophoresis

- Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis: A case report

- Characterization and evaluation of anti-Salmonella enteritidis activity of indigenous probiotic lactobacilli in mice

- Aberrant pulmonary immune response of obese mice to periodontal infection

- Bacteriospermia – A formidable player in male subfertility

- In silico and in vivo analysis of TIPE1 expression in diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- Effects of KCa channels on biological behavior of trophoblasts

- Interleukin-17A influences the vulnerability rather than the size of established atherosclerotic plaques in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice

- Multiple organ failure and death caused by Staphylococcus aureus hip infection: A case report

- Prognostic signature related to the immune environment of oral squamous cell carcinoma

- Primary and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the thyroid gland: Two case reports

- Neuroprotective effects of crocin and crocin-loaded niosomes against the paraquat-induced oxidative brain damage in rats

- Role of MMP-2 and CD147 in kidney fibrosis

- Geometric basis of action potential of skeletal muscle cells and neurons

- Babesia microti-induced fulminant sepsis in an immunocompromised host: A case report and the case-specific literature review

- Role of cerebellar cortex in associative learning and memory in guinea pigs

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing technique for diagnosing a specific case of necrotizing meningoencephalitis caused by human herpesvirus 2

- Case report: Quadruple primary malignant neoplasms including esophageal, ureteral, and lung in an elderly male

- Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 promotes angiogenesis in hepatoma carcinoma via the miR-125a-5p/VEGF pathway

- Osteogenic differentiation of periodontal membrane stem cells in inflammatory environments

- Knockdown of SHMT2 enhances the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to radiotherapy through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Continuous renal replacement therapy combined with double filtration plasmapheresis in the treatment of severe lupus complicated by serious bacterial infections in children: A case report

- Simultaneous triple primary malignancies, including bladder cancer, lymphoma, and lung cancer, in an elderly male: A case report

- Preclinical immunogenicity assessment of a cell-based inactivated whole-virion H5N1 influenza vaccine

- One case of iodine-125 therapy – A new minimally invasive treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- S1P promotes corneal trigeminal neuron differentiation and corneal nerve repair via upregulating nerve growth factor expression in a mouse model

- Early cancer detection by a targeted methylation assay of circulating tumor DNA in plasma

- Calcifying nanoparticles initiate the calcification process of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro through the activation of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway and promote the decay of echinococcosis

- Evaluation of prognostic markers in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2

- N6-Methyladenosine-related alternative splicing events play a role in bladder cancer

- Characterization of the structural, oxidative, and immunological features of testis tissue from Zucker diabetic fatty rats

- Effects of glucose and osmotic pressure on the proliferation and cell cycle of human chorionic trophoblast cells

- Investigation of genotype diversity of 7,804 norovirus sequences in humans and animals of China

- Characteristics and karyotype analysis of a patient with turner syndrome complicated with multiple-site tumors: A case report

- Aggravated renal fibrosis is positively associated with the activation of HMGB1-TLR2/4 signaling in STZ-induced diabetic mice

- Distribution characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG in false-positive results detected by chemiluminescent immunoassay

- SRPX2 attenuated oxygen–glucose deprivation and reperfusion-induced injury in cardiomyocytes via alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis through targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis

- Aquaporin-8 overexpression is involved in vascular structure and function changes in placentas of gestational diabetes mellitus patients

- Relationship between CRP gene polymorphisms and ischemic stroke risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Effects of growth hormone on lipid metabolism and sexual development in pubertal obese male rats

- Cloning and identification of the CTLA-4IgV gene and functional application of vaccine in Xinjiang sheep

- Antitumor activity of RUNX3: Upregulation of E-cadherin and downregulation of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma

- PHF8 promotes osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in old rat with osteoporosis by regulating Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- A review of the current state of the computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems for breast cancer diagnosis

- Bilateral dacryoadenitis in adult-onset Still’s disease: A case report

- A novel association between Bmi-1 protein expression and the SUVmax obtained by 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma

- The role of erythrocytes and erythroid progenitor cells in tumors

- Relationship between platelet activation markers and spontaneous abortion: A meta-analysis

- Abnormal methylation caused by folic acid deficiency in neural tube defects

- Silencing TLR4 using an ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction-based shRNA system reduces ischemia-induced seizures in hyperglycemic rats

- Plant Sciences

- Seasonal succession of bacterial communities in cultured Caulerpa lentillifera detected by high-throughput sequencing

- Cloning and prokaryotic expression of WRKY48 from Caragana intermedia

- Novel Brassica hybrids with different resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans reveal unbalanced rDNA signal patterns

- Application of exogenous auxin and gibberellin regulates the bolting of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Phytoremediation of pollutants from wastewater: A concise review

- Genome-wide identification and characterization of NBS-encoding genes in the sweet potato wild ancestor Ipomoea trifida (H.B.K.)

- Alleviative effects of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the physiological toxicity of 3-nitrophenol to rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings

- Selection and functional identification of Dof genes expressed in response to nitrogen in Populus simonii × Populus nigra

- Study on pecan seed germination influenced by seed endocarp

- Identification of active compounds in Ophiopogonis Radix from different geographical origins by UPLC-Q/TOF-MS combined with GC-MS approaches

- The entire chloroplast genome sequence of Asparagus cochinchinensis and genetic comparison to Asparagus species

- Genome-wide identification of MAPK family genes and their response to abiotic stresses in tea plant (Camellia sinensis)

- Selection and validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis of different organs at various development stages in Caragana intermedia

- Cloning and expression analysis of SERK1 gene in Diospyros lotus

- Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic profiling revealed coping mechanisms of the edible and medicinal homologous plant Plantago asiatica L. cadmium resistance

- A missense variant in NCF1 is associated with susceptibility to unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion

- Assessment of drought tolerance indices in faba bean genotypes under different irrigation regimes

- The entire chloroplast genome sequence of Asparagus setaceus (Kunth) Jessop: Genome structure, gene composition, and phylogenetic analysis in Asparagaceae

- Food Science

- Dietary food additive monosodium glutamate with or without high-lipid diet induces spleen anomaly: A mechanistic approach on rat model

- Binge eating disorder during COVID-19

- Potential of honey against the onset of autoimmune diabetes and its associated nephropathy, pancreatitis, and retinopathy in type 1 diabetic animal model

- FTO gene expression in diet-induced obesity is downregulated by Solanum fruit supplementation

- Physical activity enhances fecal lactobacilli in rats chronically drinking sweetened cola beverage

- Supercritical CO2 extraction, chemical composition, and antioxidant effects of Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt. oleoresin

- Functional constituents of plant-based foods boost immunity against acute and chronic disorders

- Effect of selenium and methods of protein extraction on the proteomic profile of Saccharomyces yeast

- Microbial diversity of milk ghee in southern Gansu and its effect on the formation of ghee flavor compounds

- Ecology and Environmental Sciences

- Effects of heavy metals on bacterial community surrounding Bijiashan mining area located in northwest China

- Microorganism community composition analysis coupling with 15N tracer experiments reveals the nitrification rate and N2O emissions in low pH soils in Southern China

- Genetic diversity and population structure of Cinnamomum balansae Lecomte inferred by microsatellites

- Preliminary screening of microplastic contamination in different marine fish species of Taif market, Saudi Arabia

- Plant volatile organic compounds attractive to Lygus pratensis

- Effects of organic materials on soil bacterial community structure in long-term continuous cropping of tomato in greenhouse

- Effects of soil treated fungicide fluopimomide on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) disease control and plant growth

- Prevalence of Yersinia pestis among rodents captured in a semi-arid tropical ecosystem of south-western Zimbabwe

- Effects of irrigation and nitrogen fertilization on mitigating salt-induced Na+ toxicity and sustaining sea rice growth

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Poly-l-lysine-caused cell adhesion induces pyroptosis in THP-1 monocytes

- Development of alkaline phosphatase-scFv and its use for one-step enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for His-tagged protein detection

- Development and validation of a predictive model for immune-related genes in patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma

- Agriculture

- Effects of chemical-based fertilizer replacement with biochar-based fertilizer on albic soil nutrient content and maize yield

- Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of CPP-like gene family in Triticum aestivum L. under different hormone and stress conditions

- Agronomic and economic performance of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) varieties in response to rates of blended NPS fertilizer in Kindo Koysha district, Southern Ethiopia

- Influence of furrow irrigation regime on the yield and water consumption indicators of winter wheat based on a multi-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation

- Discovery of exercise-related genes and pathway analysis based on comparative genomes of Mongolian originated Abaga and Wushen horse

- Lessons from integrated seasonal forecast-crop modelling in Africa: A systematic review

- Evolution trend of soil fertility in tobacco-planting area of Chenzhou, Hunan Province, China

- Animal Sciences

- Morphological and molecular characterization of Tatera indica Hardwicke 1807 (Rodentia: Muridae) from Pothwar, Pakistan

- Research on meat quality of Qianhua Mutton Merino sheep and Small-tail Han sheep

- SI: A Scientific Memoir

- Suggestions on leading an academic research laboratory group

- My scientific genealogy and the Toronto ACDC Laboratory, 1988–2022

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Changes of immune cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by radiofrequency ablation and hepatectomy, a pilot study”

- Erratum to “A two-microRNA signature predicts the progression of male thyroid cancer”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Lidocaine has antitumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma via the circ_DYNC1H1/miR-520a-3p/USP14 axis”

Articles in the same Issue

- Biomedical Sciences

- Effects of direct oral anticoagulants dabigatran and rivaroxaban on the blood coagulation function in rabbits

- The mother of all battles: Viruses vs humans. Can humans avoid extinction in 50–100 years?

- Knockdown of G1P3 inhibits cell proliferation and enhances the cytotoxicity of dexamethasone in acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- LINC00665 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating mRNA via the m6A enzyme

- Association study of CLDN14 variations in patients with kidney stones

- Concanavalin A-induced autoimmune hepatitis model in mice: Mechanisms and future outlook

- Regulation of miR-30b in cancer development, apoptosis, and drug resistance

- Informatic analysis of the pulmonary microecology in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis at three different stages

- Swimming attenuates tumor growth in CT-26 tumor-bearing mice and suppresses angiogenesis by mediating the HIF-1α/VEGFA pathway

- Characterization of intestinal microbiota and serum metabolites in patients with mild hepatic encephalopathy

- Functional conservation and divergence in plant-specific GRF gene family revealed by sequences and expression analysis

- Application of the FLP/LoxP-FRT recombination system to switch the eGFP expression in a model prokaryote

- Biomedical evaluation of antioxidant properties of lamb meat enriched with iodine and selenium

- Intravenous infusion of the exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells enhance neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury via suppressing the NF-κB pathway

- Effect of dietary pattern on pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus and its clinical significance

- Potential regulatory mechanism of TNF-α/TNFR1/ANXA1 in glioma cells and its role in glioma cell proliferation

- Effect of the genetic mutant G71R in uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 on the conjugation of bilirubin

- Quercetin inhibits cytotoxicity of PC12 cells induced by amyloid-beta 25–35 via stimulating estrogen receptor α, activating ERK1/2, and inhibiting apoptosis

- Nutrition intervention in the management of novel coronavirus pneumonia patients

- circ-CFH promotes the development of HCC by regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, and glycolysis through the miR-377-3p/RNF38 axis

- Bmi-1 directly upregulates glucose transporter 1 in human gastric adenocarcinoma

- Lacunar infarction aggravates the cognitive deficit in the elderly with white matter lesion

- Hydroxysafflor yellow A improved retinopathy via Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in rats

- Comparison of axon extension: PTFE versus PLA formed by a 3D printer

- Elevated IL-35 level and iTr35 subset increase the bacterial burden and lung lesions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice

- A case report of CAT gene and HNF1β gene variations in a patient with early-onset diabetes

- Study on the mechanism of inhibiting patulin production by fengycin

- SOX4 promotes high-glucose-induced inflammation and angiogenesis of retinal endothelial cells by activating NF-κB signaling pathway

- Relationship between blood clots and COVID-19 vaccines: A literature review

- Analysis of genetic characteristics of 436 children with dysplasia and detailed analysis of rare karyotype

- Bioinformatics network analyses of growth differentiation factor 11

- NR4A1 inhibits the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells: Involvement of TGF-β–Smad2/3/4–ZEB signaling

- Expression of Zeb1 in the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cell

- Study on the genetic damage caused by cadmium sulfide quantum dots in human lymphocytes

- Association between single-nucleotide polymorphisms of NKX2.5 and congenital heart disease in Chinese population: A meta-analysis

- Assessment of the anesthetic effect of modified pentothal sodium solution on Sprague-Dawley rats

- Genetic susceptibility to high myopia in Han Chinese population

- Potential biomarkers and molecular mechanisms in preeclampsia progression

- Silencing circular RNA-friend leukemia virus integration 1 restrained malignancy of CC cells and oxaliplatin resistance by disturbing dyskeratosis congenita 1

- Endostar plus pembrolizumab combined with a platinum-based dual chemotherapy regime for advanced pulmonary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma as a first-line treatment: A case report

- The significance of PAK4 in signaling and clinicopathology: A review

- Sorafenib inhibits ovarian cancer cell proliferation and mobility and induces radiosensitivity by targeting the tumor cell epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- Characterization of rabbit polyclonal antibody against camel recombinant nanobodies

- Active legumain promotes invasion and migration of neuroblastoma by regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- Effect of cell receptors in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Current insights

- MT-12 inhibits the proliferation of bladder cells in vitro and in vivo by enhancing autophagy through mitochondrial dysfunction

- Study of hsa_circRNA_000121 and hsa_circRNA_004183 in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma

- BuyangHuanwu Decoction attenuates cerebral vasospasm caused by subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats via PI3K/AKT/eNOS axis

- Effects of the interaction of Notch and TLR4 pathways on inflammation and heart function in septic heart

- Monosodium iodoacetate-induced subchondral bone microstructure and inflammatory changes in an animal model of osteoarthritis

- A rare presentation of type II Abernethy malformation and nephrotic syndrome: Case report and review

- Rapid death due to pulmonary epithelioid haemangioendothelioma in several weeks: A case report

- Hepatoprotective role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α in non-cancerous hepatic tissues following transcatheter arterial embolization

- Correlation between peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations and primary systemic lupus erythematosus

- A novel SLC8A1-ALK fusion in lung adenocarcinoma confers sensitivity to alectinib: A case report

- β-Hydroxybutyrate upregulates FGF21 expression through inhibition of histone deacetylases in hepatocytes

- Identification of metabolic genes for the prediction of prognosis and tumor microenvironment infiltration in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer

- BTBD10 inhibits glioma tumorigenesis by downregulating cyclin D1 and p-Akt

- Mucormycosis co-infection in COVID-19 patients: An update

- Metagenomic next-generation sequencing in diagnosing Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: A case report

- Long non-coding RNA HOXB-AS1 is a prognostic marker and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cells’ proliferation and invasion

- Preparation and evaluation of LA-PEG-SPION, a targeted MRI contrast agent for liver cancer

- Proteomic analysis of the liver regulating lipid metabolism in Chaohu ducks using two-dimensional electrophoresis

- Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis: A case report

- Characterization and evaluation of anti-Salmonella enteritidis activity of indigenous probiotic lactobacilli in mice

- Aberrant pulmonary immune response of obese mice to periodontal infection

- Bacteriospermia – A formidable player in male subfertility

- In silico and in vivo analysis of TIPE1 expression in diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- Effects of KCa channels on biological behavior of trophoblasts

- Interleukin-17A influences the vulnerability rather than the size of established atherosclerotic plaques in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice

- Multiple organ failure and death caused by Staphylococcus aureus hip infection: A case report

- Prognostic signature related to the immune environment of oral squamous cell carcinoma

- Primary and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the thyroid gland: Two case reports

- Neuroprotective effects of crocin and crocin-loaded niosomes against the paraquat-induced oxidative brain damage in rats

- Role of MMP-2 and CD147 in kidney fibrosis

- Geometric basis of action potential of skeletal muscle cells and neurons

- Babesia microti-induced fulminant sepsis in an immunocompromised host: A case report and the case-specific literature review

- Role of cerebellar cortex in associative learning and memory in guinea pigs

- Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing technique for diagnosing a specific case of necrotizing meningoencephalitis caused by human herpesvirus 2

- Case report: Quadruple primary malignant neoplasms including esophageal, ureteral, and lung in an elderly male

- Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 promotes angiogenesis in hepatoma carcinoma via the miR-125a-5p/VEGF pathway

- Osteogenic differentiation of periodontal membrane stem cells in inflammatory environments

- Knockdown of SHMT2 enhances the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to radiotherapy through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Continuous renal replacement therapy combined with double filtration plasmapheresis in the treatment of severe lupus complicated by serious bacterial infections in children: A case report

- Simultaneous triple primary malignancies, including bladder cancer, lymphoma, and lung cancer, in an elderly male: A case report

- Preclinical immunogenicity assessment of a cell-based inactivated whole-virion H5N1 influenza vaccine

- One case of iodine-125 therapy – A new minimally invasive treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- S1P promotes corneal trigeminal neuron differentiation and corneal nerve repair via upregulating nerve growth factor expression in a mouse model

- Early cancer detection by a targeted methylation assay of circulating tumor DNA in plasma

- Calcifying nanoparticles initiate the calcification process of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro through the activation of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway and promote the decay of echinococcosis

- Evaluation of prognostic markers in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2

- N6-Methyladenosine-related alternative splicing events play a role in bladder cancer

- Characterization of the structural, oxidative, and immunological features of testis tissue from Zucker diabetic fatty rats

- Effects of glucose and osmotic pressure on the proliferation and cell cycle of human chorionic trophoblast cells

- Investigation of genotype diversity of 7,804 norovirus sequences in humans and animals of China

- Characteristics and karyotype analysis of a patient with turner syndrome complicated with multiple-site tumors: A case report

- Aggravated renal fibrosis is positively associated with the activation of HMGB1-TLR2/4 signaling in STZ-induced diabetic mice

- Distribution characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG in false-positive results detected by chemiluminescent immunoassay

- SRPX2 attenuated oxygen–glucose deprivation and reperfusion-induced injury in cardiomyocytes via alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis through targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis

- Aquaporin-8 overexpression is involved in vascular structure and function changes in placentas of gestational diabetes mellitus patients

- Relationship between CRP gene polymorphisms and ischemic stroke risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Effects of growth hormone on lipid metabolism and sexual development in pubertal obese male rats

- Cloning and identification of the CTLA-4IgV gene and functional application of vaccine in Xinjiang sheep

- Antitumor activity of RUNX3: Upregulation of E-cadherin and downregulation of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma

- PHF8 promotes osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in old rat with osteoporosis by regulating Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- A review of the current state of the computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems for breast cancer diagnosis

- Bilateral dacryoadenitis in adult-onset Still’s disease: A case report

- A novel association between Bmi-1 protein expression and the SUVmax obtained by 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma

- The role of erythrocytes and erythroid progenitor cells in tumors

- Relationship between platelet activation markers and spontaneous abortion: A meta-analysis

- Abnormal methylation caused by folic acid deficiency in neural tube defects

- Silencing TLR4 using an ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction-based shRNA system reduces ischemia-induced seizures in hyperglycemic rats

- Plant Sciences

- Seasonal succession of bacterial communities in cultured Caulerpa lentillifera detected by high-throughput sequencing

- Cloning and prokaryotic expression of WRKY48 from Caragana intermedia

- Novel Brassica hybrids with different resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans reveal unbalanced rDNA signal patterns

- Application of exogenous auxin and gibberellin regulates the bolting of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Phytoremediation of pollutants from wastewater: A concise review

- Genome-wide identification and characterization of NBS-encoding genes in the sweet potato wild ancestor Ipomoea trifida (H.B.K.)

- Alleviative effects of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the physiological toxicity of 3-nitrophenol to rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings

- Selection and functional identification of Dof genes expressed in response to nitrogen in Populus simonii × Populus nigra

- Study on pecan seed germination influenced by seed endocarp

- Identification of active compounds in Ophiopogonis Radix from different geographical origins by UPLC-Q/TOF-MS combined with GC-MS approaches

- The entire chloroplast genome sequence of Asparagus cochinchinensis and genetic comparison to Asparagus species

- Genome-wide identification of MAPK family genes and their response to abiotic stresses in tea plant (Camellia sinensis)

- Selection and validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis of different organs at various development stages in Caragana intermedia

- Cloning and expression analysis of SERK1 gene in Diospyros lotus

- Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic profiling revealed coping mechanisms of the edible and medicinal homologous plant Plantago asiatica L. cadmium resistance

- A missense variant in NCF1 is associated with susceptibility to unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion

- Assessment of drought tolerance indices in faba bean genotypes under different irrigation regimes

- The entire chloroplast genome sequence of Asparagus setaceus (Kunth) Jessop: Genome structure, gene composition, and phylogenetic analysis in Asparagaceae

- Food Science

- Dietary food additive monosodium glutamate with or without high-lipid diet induces spleen anomaly: A mechanistic approach on rat model

- Binge eating disorder during COVID-19

- Potential of honey against the onset of autoimmune diabetes and its associated nephropathy, pancreatitis, and retinopathy in type 1 diabetic animal model

- FTO gene expression in diet-induced obesity is downregulated by Solanum fruit supplementation

- Physical activity enhances fecal lactobacilli in rats chronically drinking sweetened cola beverage

- Supercritical CO2 extraction, chemical composition, and antioxidant effects of Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt. oleoresin

- Functional constituents of plant-based foods boost immunity against acute and chronic disorders

- Effect of selenium and methods of protein extraction on the proteomic profile of Saccharomyces yeast

- Microbial diversity of milk ghee in southern Gansu and its effect on the formation of ghee flavor compounds

- Ecology and Environmental Sciences

- Effects of heavy metals on bacterial community surrounding Bijiashan mining area located in northwest China

- Microorganism community composition analysis coupling with 15N tracer experiments reveals the nitrification rate and N2O emissions in low pH soils in Southern China

- Genetic diversity and population structure of Cinnamomum balansae Lecomte inferred by microsatellites

- Preliminary screening of microplastic contamination in different marine fish species of Taif market, Saudi Arabia

- Plant volatile organic compounds attractive to Lygus pratensis

- Effects of organic materials on soil bacterial community structure in long-term continuous cropping of tomato in greenhouse

- Effects of soil treated fungicide fluopimomide on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) disease control and plant growth

- Prevalence of Yersinia pestis among rodents captured in a semi-arid tropical ecosystem of south-western Zimbabwe

- Effects of irrigation and nitrogen fertilization on mitigating salt-induced Na+ toxicity and sustaining sea rice growth

- Bioengineering and Biotechnology

- Poly-l-lysine-caused cell adhesion induces pyroptosis in THP-1 monocytes

- Development of alkaline phosphatase-scFv and its use for one-step enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for His-tagged protein detection

- Development and validation of a predictive model for immune-related genes in patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma

- Agriculture

- Effects of chemical-based fertilizer replacement with biochar-based fertilizer on albic soil nutrient content and maize yield

- Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of CPP-like gene family in Triticum aestivum L. under different hormone and stress conditions

- Agronomic and economic performance of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) varieties in response to rates of blended NPS fertilizer in Kindo Koysha district, Southern Ethiopia

- Influence of furrow irrigation regime on the yield and water consumption indicators of winter wheat based on a multi-level fuzzy comprehensive evaluation

- Discovery of exercise-related genes and pathway analysis based on comparative genomes of Mongolian originated Abaga and Wushen horse

- Lessons from integrated seasonal forecast-crop modelling in Africa: A systematic review

- Evolution trend of soil fertility in tobacco-planting area of Chenzhou, Hunan Province, China

- Animal Sciences

- Morphological and molecular characterization of Tatera indica Hardwicke 1807 (Rodentia: Muridae) from Pothwar, Pakistan

- Research on meat quality of Qianhua Mutton Merino sheep and Small-tail Han sheep

- SI: A Scientific Memoir

- Suggestions on leading an academic research laboratory group

- My scientific genealogy and the Toronto ACDC Laboratory, 1988–2022

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Changes of immune cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by radiofrequency ablation and hepatectomy, a pilot study”

- Erratum to “A two-microRNA signature predicts the progression of male thyroid cancer”

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Lidocaine has antitumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma via the circ_DYNC1H1/miR-520a-3p/USP14 axis”