Abstract

In this work, cosmological solutions based on the time-dependent cosmological (

1 Introduction

Recent cosmological observations have shown that the universe in conformity with the cosmological principle, i.e., it is almost homogeneous and isotropic on large scales. Moreover, it is undergoing a recent epoch of accelerated expansion. Although it is not conclusively known what caused this recent cosmic acceleration, the prevailing argument is that dark energy caused it.

Among the most widely considered candidates of dark energy is the vacuum energy of the cosmological constant

Dirac’s hypothesis that the gravitational constant decreases with time has been a matter of scrutiny for some time (Canuto et al. 1979), but recent attempts to consider both

Since the isotropy assumption is only an approximation on large scales, and not something explained from first principles, there is the possibility that the spatially homogeneous and anisotropic cosmological modes play a significant role in explaining the evolution of the universe at its early stages. At these times, the universe was full of anisotropies with a highly irregular mechanism that isotropised later. In fact, several authors have shown over the years that there is some degree of anisotropy in the observed universe that necessitates the consideration of a non-FLRW geometry (see, e.g., Misner 1968, Pereira et al. 2007, Almeida et al. 2022). Hence, there is a need for a detailed study of cosmological models that describe an early-time anisotropy with a proper mechanism to produce [near] isotropy at late times on the one hand and an accelerated expansion at the present epoch on the other hand.

In view of the aforementioned motivation, various researchers have investigated the anisotropic Bianchi type cosmological models with variable forms of

The main purpose of this article, as a follow-up of the aforementioned work (Alfedeel 2020), is to reformulate the reduced system of differential equations (DEs) of the Einstein field equations for Bianchi type-I cosmology model with time-dependent

2 Bianchi type-I cosmology

The line-element of the spatially homogeneous and anisotropic Bianchi type-

where

where

The Einstein field equations with time-dependent

giving a solution for the energy density as follows:

where

where

In the multi-fluid setting,

and the expression for the metric variables

where

It is worth mentioning that solutions (9)–(11) were first obtained by Saha and Shikin (1997) and Saha (2001b). In this model, the physical and dynamical parameters, the deceleration parameter

where

2.1 Model from data

Throughout this section, the constrained density parameters (Farooq and Ratra 2013)

as the mass density of the universe components, where

2.2 The numerical solution

Having introduced the defining parameters for the Bianchi-I model, we can obtain the following set of non-linear first-order differential equations that describe the evolution of the background:

where we have used the following short hands:

These are numerical constants that totally depend on the value of

2.3 Equations in redshift space

To transform the background evolution equations, i.e., the underlying Bianchi type-I system of DEs, any time dependent quantity

where

Thus, using these definitions, Eqs. (18) and (19) can be transformed into redshift space as follows:

These two equations describe an equivalent dynamical system as the one described by Eqs. (17), (18), and (19). For the sake of computational suitability, let us now define the dimensionless parameters corresponding to the defining dimensional parameters of the model as follows:

In these parameters, our previous equations can be re-written in a fully dimensionless form as follows:

Once we have calculated

as well as the scale factor solutions of the model

where we have defined the new dimensionless parameters

3 Results and discussion

The observed and currently accepted values of

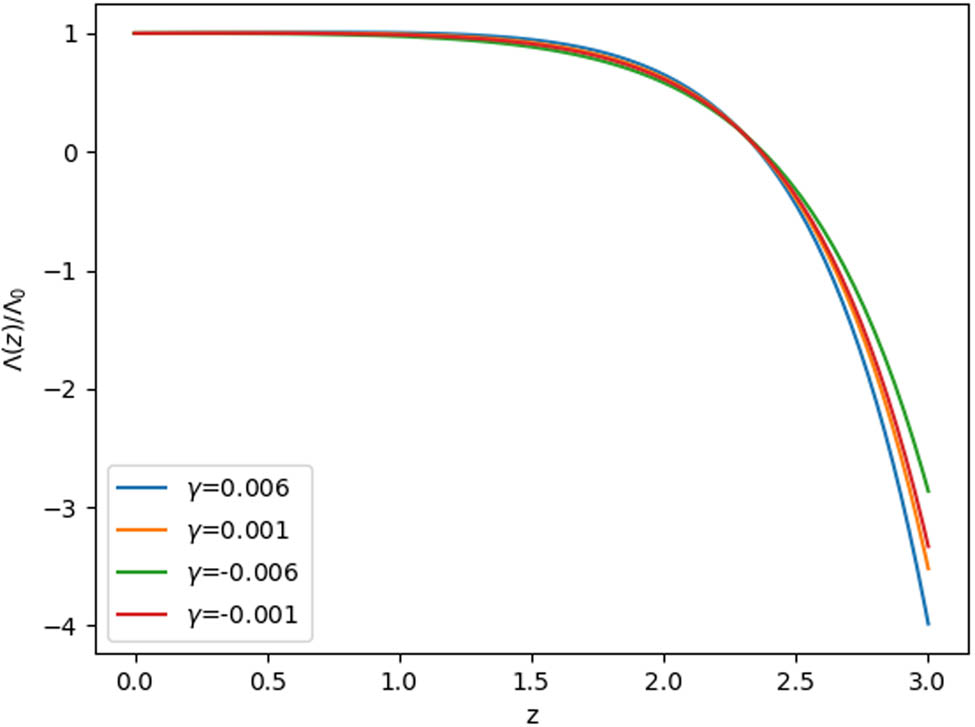

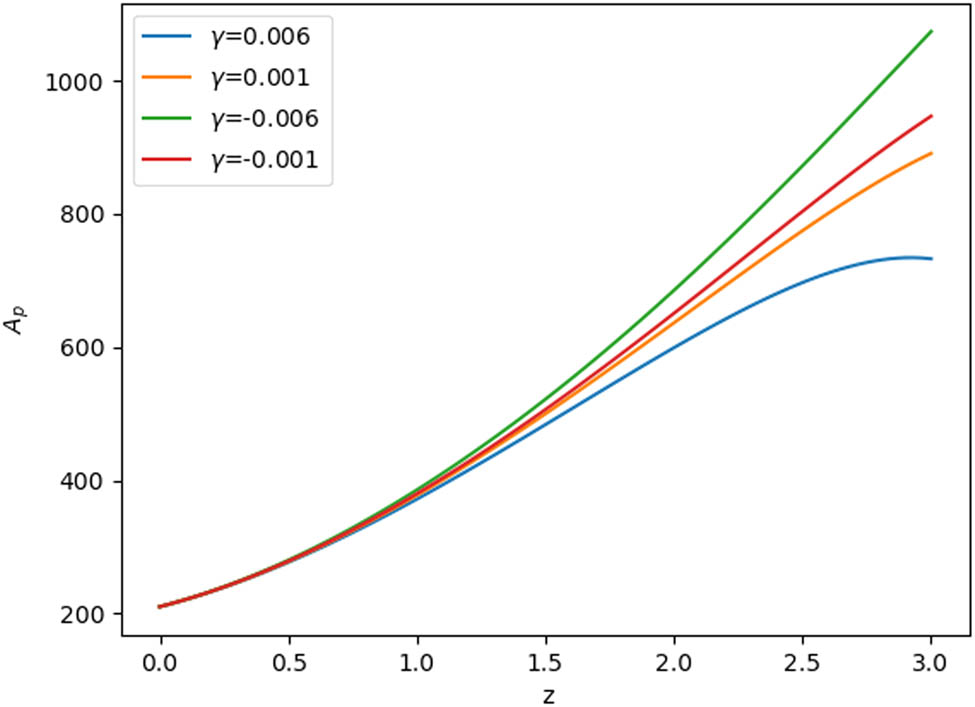

The variation of

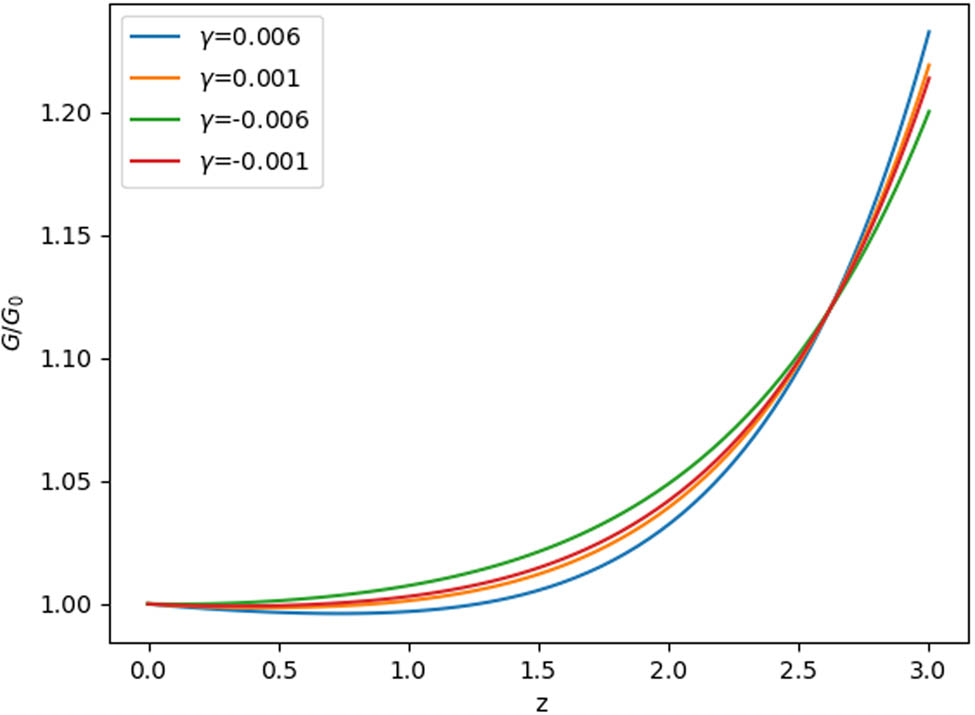

The variation

The variation

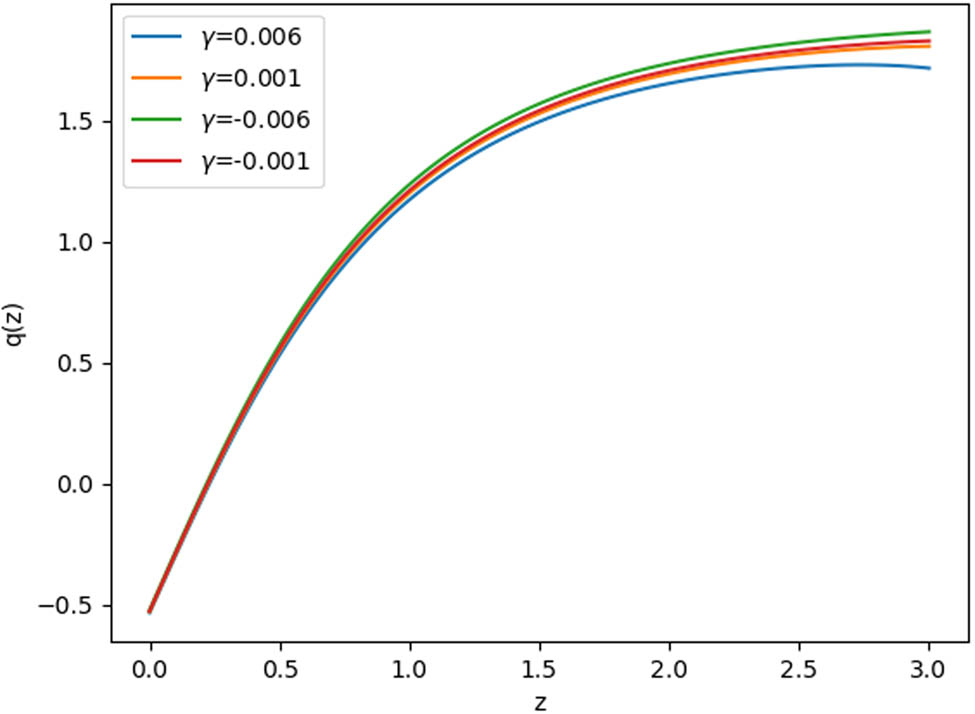

The variation of the deceleration parameter in redshift.

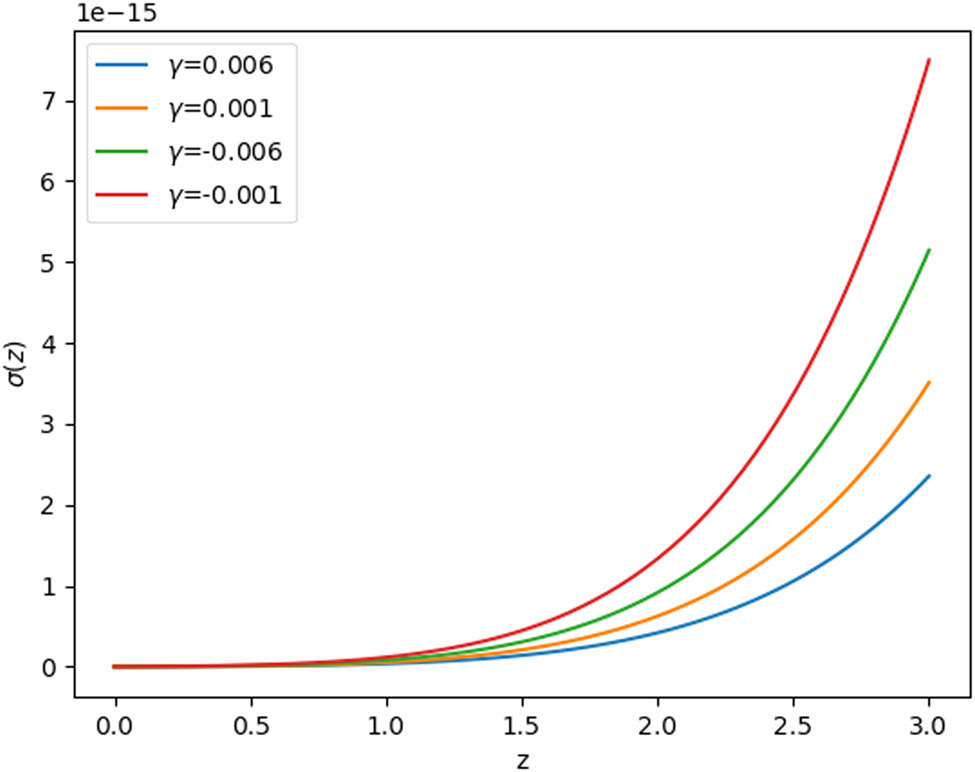

The evolution of the shear parameter in redshift.

The evolution of the anisotropy parameter in redshift.

From these figures, the plots for

The plots of the deceleration parameter

4 Conclusion

In this work, we have found generic solutions for the Bianchi type-I cosmological model with time-varying Newtonian and cosmological “constants” for realistic multi-component perfect-fluid scenarios. In the solution process, we rewrote the EFEs for the specific model of our interest as a closed system of two first-order differential equations involving normalised and dimensionless cosmological parameters

The predicted evolution of the different cosmological parameters for the Bianchi-

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University for funding this work through Research Group no. RG-21-09-18.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Aghanim N, Akrami Y, Ashdown M, Aumont J, Baccigalupi C, Ballardini M, et al. 2008. Planck 2018 results-VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron Astrophys. 641:A6. 10.1051/0004-6361/201833910Suche in Google Scholar

Alfedeel AHA, Abebe A, Gubara HM. 2018. A generalised solutions of Bianchi type-V cosmological models with time dependent G and Λ. Universe. 4(8):83. 10.3390/universe4080083Suche in Google Scholar

Alfedeel AHA. 2020. Bianchi type-I model with time varying Λ and G: The generalised solution. Open Astron. 29(1):89–93. 10.1515/astro-2020-0012Suche in Google Scholar

Almeida JPB, Motoa-Manzano J, Noreña J, Pereira TS, Valenzuela-Toledo CA. 2022. Structure formation in an anisotropic universe: Eulerian perturbation theory. J Cosmol Astroparticle Phys. 2022(02):018. 10.1088/1475-7516/2022/02/018Suche in Google Scholar

Arbab IA. 1998. Bianchi type-I viscous universe with variable G and Lambda. Gen Relativ Gravit. 30(9):1401–1405. 10.1023/A:1018856625508Suche in Google Scholar

Banerjee JP, Duttachoudhuryi SB, Sanyal AK. 1985. Bianchi type-I cosmological model with a viscous fluid. J Math Phys. 26(11):3010–3015. 10.1063/1.526676Suche in Google Scholar

Belinskii VA. 1975. On influence of viscosity on the character of cosmological evolution. Zh Eksp Teor Fiz. 69:401–413. Suche in Google Scholar

Canuto V, Hsieh SH, Owen JR. 1979. Varying G. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 188(4):829. 10.1093/mnras/188.4.829Suche in Google Scholar

Carvalho JC, Lima JAS, Waga I. 1992. Cosmological consequences of a time-dependent Λ term. Phys Rev D. 46(6):2404. 10.1103/PhysRevD.46.2404Suche in Google Scholar

Dwivedi UK. 2012. Bianchi type-V models with decaying cosmological term Λ. Int J Management IT Eng. 2(7):568–573. Suche in Google Scholar

Farooq O, Ratra B. 2013. Hubble parameter measurement constraints on the cosmological deceleration-acceleration transition redshift. Astrophys J Lett. 766(1):7. 10.1088/2041-8205/766/1/L7Suche in Google Scholar

Mak MK, Harko T. 2002. Bianchi type-I universes with causal bulk viscous cosmological fluid. Int J Mod Phys D. 11(03):447–462. 10.1142/S0218271802001743Suche in Google Scholar

Mazumder A. 1994. Solutions of LRS Bianchi I space-time filled with a perfect fluid. Gen Relativ Gravit. 26(3):307–310. 10.1007/BF02108011Suche in Google Scholar

Misner CW. 1968. The isotropy of the universe. Astrophys J. 151:431. 10.1086/149448Suche in Google Scholar

Pereira TS, Pitrou C, Uzan JP. 2007. Theory of cosmological perturbations in an anisotropic universe. J Cosmol Astroparticle Phys. 09:006. 10.1088/1475-7516/2007/09/006Suche in Google Scholar

Pradhan A, Kumar A. 2001. LRS Bianchi I cosmological universe models with varying cosmological term Λ. Int J Mod Phys D. 10(03):291–298. 10.1142/S0218271801000718Suche in Google Scholar

Pradhan A, Ostarod S. 2006. Universe with time dependent deceleration parameter and Λ term in general relativity. Astrophys Space Sci. 306(1):11–16. 10.1007/s10509-006-9178-9Suche in Google Scholar

Pradhan A, Yadav L, Yadav AK. 2004. Viscous fluid cosmological models in LRS Bianchi type-V universe with varying Λ. Czech J Phys. 54(4):487–498. 10.1023/B:CJOP.0000020586.43735.b5Suche in Google Scholar

Saha B, Shikin GN. 1997. Interacting spinor and scalar fields in Bianchi type-I universe filled with perfect fluid: exact self-consistent solutions. Gen Relativ Gravit. 29(9):1099–1113. 10.1023/A:1018887024268Suche in Google Scholar

Saha B. 2001a. Dirac spinor in Bianchi-I universe with time-dependent gravitational and cosmological constants. Modern Phys Lett A. 16(20):1287–1296. 10.1142/S0217732301004546Suche in Google Scholar

Saha B. 2001b. Spinor field in a Bianchi type-I universe: regular solutions. Phys Rev D. 64(12):123501. 10.1103/PhysRevD.64.123501Suche in Google Scholar

Singh CP, Kumar S. 2009. Bianchi-I space-time with variable gravitational and cosmological constants. Int J Theor Phys. 48(8):2401–2411. 10.1007/s10773-009-0030-1Suche in Google Scholar

Singh PS, Singh JP. 2012. Bianchi type-V universe with bulk Viscous matter and time varying gravitational and cosmological constant. Res Astron Astrophys. 12:1457–1466. 10.1088/1674-4527/12/11/001Suche in Google Scholar

Singh JP, Tiwari RK. 2008. Perfect fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models with time varying G and Λ. Pramana-J Phys. 70(4):565–574. 10.1007/s12043-008-0019-ySuche in Google Scholar

Singh CP, Ram S, Zeyauddin M. 2008. Bianchi type-V perfect fluid space-time models in general relativity. Astrophys Space Sci. 315(1):181–189. 10.1007/s10509-008-9811-xSuche in Google Scholar

Singh JP, Baghel PS, Singh A. 2014. Bianchi type-I cosmological models with viscous fluid and decaying vacuum. Prespacetime J. 5(8):785–803. Suche in Google Scholar

Tiwari RK. 2008. Bianchi type-I cosmological models with time dependent G and Λ. Astrophys Space Sci. 318(3):243–247. 10.1007/s10509-008-9924-2Suche in Google Scholar

Velten HE, Vom Marttens RF, Zimdahl W. 2014. Aspects of the cosmological coincidence problem. Eur Phys J C. 74(11):1–8. 10.1140/epjc/s10052-014-3160-4Suche in Google Scholar

Weinberg S. 1989. The cosmological constant problem. Rev Mod Phys. 61(1):1. 10.1007/978-3-662-04587-9_2Suche in Google Scholar

Yadav AK. 2013. Bianchi type-V matter filled universe with varying Lambda term in general relativity. Electron J Theor Phys. 28(10):169–182. Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Alnadhief H. A. Alfedeel and Amare Abebe, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm