Abstract

The equilibrium cold dark matter halos show the almost universal inner

1 Introduction

Cosmological simulations have revealed many almost universal properties of the “isolated” equilibrium cold dark matter halos (Navarro et al. 1997, 2010), and the most prominent one may be the NFW density profile, which shows the inner density slope

In this article, the almost universal

The structure of the content is as follows: in Section 2, we will briefly review the result of the LG theory by considering the fluctuations of the Helmholtz and Gibbs free energy; in Section 3, we will apply this theory for simulated dark matter halos; finally, we will conclude this study in Section 4.

2 Landau–Ginzburg theory

In the statistical physics, each thermodynamical equilibrium state corresponds to one statistical distribution of the mechanical states, and the value of the thermodynamical quantity is the ensemble-average of all the mechanical states in this statistical distribution. Therefore, there always exists the fluctuations from this average value. The LG theory just describes the long-range correlation of fluctuations from the equilibrium state at least in an approximate fashion (Plischike and Birgersen 2006). For the homogeneous and isotropic systems, the two-point correlation function is expressed as follows:

where

In this article, we do not consider the effects of fluctuating temperature. With fixed temperature and volume, the Landau–Ginzburg theory assumes that the fluctuation of Helmholtz free energy can be expanded to the even powers of the density fluctuation:

If the density fluctuation is not large enough,

where

is the correlation length. The aforementioned results indicate that the two-point correlation function

In fact, the LG theory can describe the more general cases if there exists other generalized forces and coordinates (Plischike and Birgersen 2006): the Gibbs free energy

where

By calculating the minimum of the Gibbs free energy, we yield

where the last term is obtained by integration by parts and demanding

where

where the other solution

3 Applications for cold dark matter halos

We first show the long-range nature of gravitating system indicated by the LG theory. Let us consider the self-gravitating gas contained in a box, whose virial theorem is (Padmanabhan 2002) (here, we do not consider the short-distance cutoff) expressed as follows:

where

where

where

The value of the pressure

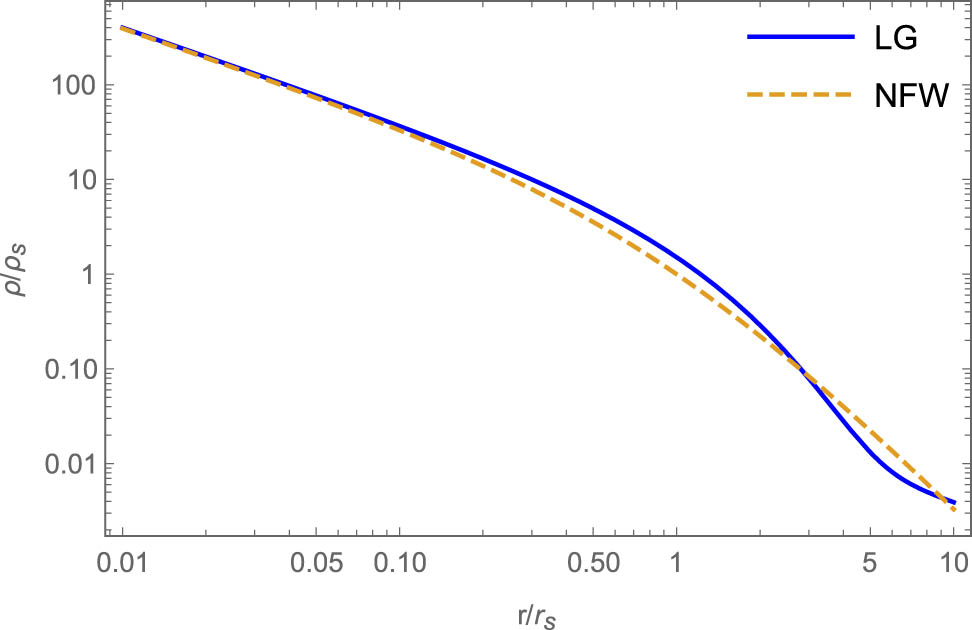

Then, we try to use the LG theory to study the structure of dark matter halos in simulations. The order parameter in the LG theory always corresponds to certain symmetries, while the density distribution also can reflect the symmetries of the system, such as that the homogeneous and isotropic systems have translational and rotational invariant symmetries. Like works in the vapor–liquid interface, the order parameter will be the density in this work to explain the cusps of dark matter halos in simulations.

In the background cosmology, the cosmological principle states that the Universe is homogeneous and isotropic at large scale, and the whole Universe can be described as the ideal fluid; the matter is modeled as the ideal gas with nonrelativistic particles, and its pressure is (p. 109 in the study by Mo et al. 2010) expressed as follows:

The pressure of the matter is commonly regarded as zero if

One problem is that someone may worry about whether the terms with high powers of

so we suggest that the perturbation

where

where

Eq. (9) is also close to the recent result of the study by Fielder et al. (2020) finding that the density profile of dark matter halos is better described by the generalized Einasto profile:

where

In the CDM scenario, the structure formation is bottom-up, and the larger halos is mainly from its progenitors’ mergers and accretions, and current simulations and theoretical analysis (El-Zant 2008, Syer and White 1998, Wang and White 2009) show that mergers and accretions will not change the inner

Besides, in the CDM scenario at time

4 Discussion and conclusion

The LG theory is used to describe the fluctuations from the equilibrium state and to study the long-range correlations of fluctuations near the critical point in an approximate fashion, and the modern method is the renormalization theory of Wilson. This article first introduced this method, and then studied the fluctuations from the background equilibrium state of the homogenous and isotropic Universe in the CDM scenario. The gravitational instability and density perturbation can contribute to the Gibbs free energy, they are modeled as one pair of the generalized force and coordinate, and we make some approximations for the form of the gravitation instability. For the density fluctuations with the smallest scale,

Our work indicates that the inner

Padmanabhan (2002) also studied the physics behind the almost universal NFW profile. He assumed that the density field can be expressed as a superposition of several halos with the same mass, core radius etc and the correlation function is power law. Compared with his work, this article does not need to consider these assumptions, and we still obtained the critical

Acknowledgments

DBK is very grateful for the suggestions from the anonymous referees.

-

Funding information: This work is supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 11929301) and National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0402600).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Eq. (3) can be obtained as shown in the textbooks such as Zhang (2005): making Fourier expansion of the density contrast,

where

so

Ensemble averaging both sides of it,

where

Then we will calculate

The probability distribution of the fluctuations of the Helmholtz free energy with fixed volume V (p. 294 of Zhang 2005) is

so

which shows that density perturbation field is Gaussian with power spectrum

Finally by (22)

where the last equality is just a mathematical problem, which can be solved by software such as Mathematica.

References

Binney JJ, Newman MEJ, Fisher AJ, Dowrick NJ. 1992. The Theory of Critical Phenomena: An Introduction to the Renormalization Group. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Inc. 10.1093/oso/9780198513940.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Campa A, Dauxois T, Fanelli D, Ruffo S. 2014. Physics of Long-range Interacting Systems. Bristol: IOP Publishing. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199581931.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Cannas SA, de Magalhaes ACN, Tamarit FA. 2000. Evidence of exactness of the mean-field theory in the nonextensive regime of long-range classical spin models. PRB. 61:11521. 10.1103/PhysRevB.61.11521Search in Google Scholar

Dalal N, Lithwick Y, Kuhlen M. 2010. The Origin of Dark Matter Halo Profiles. arXiv:1010.2539. Search in Google Scholar

Dekel A, Arad I, Devor J, Birnboim Y. 2003. Dark halo cusp: asymptotic convergence. ApJ. 588:680.10.1086/374328Search in Google Scholar

Destri C. 2018. Cored density profiles in the DARKexp model. JCAP. 5:010. 10.1088/1475-7516/2018/05/010Search in Google Scholar

Drrbeck S, Hollerer M, Thurner CW, Redinger J, Sterrer M, Bertel E. 2018. Correlation length and dimensional crossover in a quasi-one-dimensional surface system. PRB. 98:35436. 10.1103/PhysRevB.98.035436Search in Google Scholar

Eilersen A, Hansen SH, Zhang XY. 2017. Analytical derivation of the radial distribution function in spherical dark matter haloes. MNRAS. 467(2):2061–2065.10.1093/mnras/stx226Search in Google Scholar

El-Zant AA. 2008. The persistence of universal halo profiles. ApJ. 681:1058. 10.1086/587022Search in Google Scholar

Fielder CE, Mao Y-Y, Zentner AR, Newman JA, Wu H-Y, Wechsler R. 2020. Illuminating dark matter halo density profiles without subhaloes. MNRAS. 499(2):2426–2444. 10.1093/mnras/staa2851Search in Google Scholar

Francisco P, Klypin AA, Simonneau E, Betancort-Rijo J, Patiri S, Gottlöber S, et al. 2006. How far do they go? The outer structure of galactic dark matter halos. ApJ. 645:1001. 10.1086/504456Search in Google Scholar

Hansen SH, Sparre M. 2012. A derivation of (half) the dark matter distribution function. ApJ. 756:100. 10.1088/0004-637X/756/1/100Search in Google Scholar

Hjorth J, Williams LLR. 2010. Statistical mechanics of collisionless orbits. I. Origin of central cusps in dark-matter halos. ApJ. 722:851. 10.1088/0004-637X/722/1/851Search in Google Scholar

Kocsis B, Tremaine S. 2015. A numerical study of vector resonant relaxation. MNRAS. 448(4):3265–3296. 10.1093/mnras/stv057Search in Google Scholar

Mo HJ, van den Bosch F, White SDM. 2010. Galaxy Formation and Evolution. New York: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511807244Search in Google Scholar

Navarro JF, Frenk CS, White SDM. 1997. A universal density profile from hierarchical clustering. ApJ. 490:493–508. 10.1086/304888Search in Google Scholar

Navarro JF, Ludlow A, Springel V, Wang J, Vogelsberger M, White SDM, et al. 2010. The diversity and similarity of simulated cold dark matter haloes. MNRAS. 402(1):21–34. 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15878.xSearch in Google Scholar

Padmanabhan T. 2002. Statistical mechanics of gravitating systems in static and cosmological backgrounds. In: Dauxois T, Ruffo S, Arimondo E, Wilkens M, Editors. Dynamics and Thermodynamics of Systems with Long-Range Interactions. Lecture Notes in Physics, Vol. 602. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. 10.1007/3-540-45835-2_7. Search in Google Scholar

Paoluzzi M, Marconi U, Maggi C. 2018. Effective equilibrium picture in the xy model with exponentially correlated noise. PRE. 97:022605. 10.1103/PhysRevE.97.022605Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Plischike M, Birgersen B. 2006. Equilibrium Statistical Mechanics. 3rd ed. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. 10.1142/5660Search in Google Scholar

Pontzen A, Governato F. 2013. Conserved actions, maximum entropy and dark matter haloes. MNRAS. 430(1):121–133. 10.1093/mnras/sts529Search in Google Scholar

Roupas Z. 2020. Statistical mechanics of gravitational systems with regular orbits: rigid body model of vector resonant relaxation. JPA. 53:045002. 10.1088/1751-8121/ab5f7bSearch in Google Scholar

Roupas Z, Kocsis B, Tremaine S. 2017. Isotropic–Nematic Phase Transitions in Gravitational Systems. ApJ. 842:90. 10.3847/1538-4357/aa7141Search in Google Scholar

Syer D, White SDM. 1998. Dark halo mergers and the formation of a universal profile. MNRAS. 293(4):337–342. 10.1046/j.1365-8711.1998.01285.xSearch in Google Scholar

Tsuda J, Nishimori H. 2014. Mean-field theory is exact for the random-field model with long-range interactions. JPSJ. 83:074002. 10.7566/JPSJ.83.074002Search in Google Scholar

Wang J, White SDM. 2009. Are mergers responsible for universal halo properties? MNRAS. 396(2):709–717. 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14755.xSearch in Google Scholar

Wang J, Bose S, Frenk CS, Gao L, Jenkins A, Springel V, et al. 2020. Universal structure of dark matter haloes over a mass range of 20 orders of magnitude. Nature. 585:39–42. 10.1038/s41586-020-2642-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Zhang Q-R. 2005. Statistical Mechanics (in Chinese), 2nd ed. Beijing: China Science Publishing. Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Dong-Biao Kang and Tong-Jie Zhang, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm