Abstract

The analysis of radio emission of three new pulsars discovered at the Pushchino Radio Astronomy Observatory is presented. The detailed observations were carried out at a frequency of 111 MHz using the large phase array and the standard digital receiver with a total bandwidth of 2.245 MHz and a time resolution of 2.46 or 5.12 ms. All pulsars exhibit features of their radiation, the subpulse drift is observed in J0220+3622, the flare activity is exhibited in J0303+2248, and the nulling phenomenon has been detected in J0810+3725.

1 Introduction

For many years, the interest of the neutron star observers fueled by the discovery of new pulsars in different wavelengths, as well as by a wide variety of observational features of these sources. Radio pulsars are generally known as highly variable objects. Fluctuations in the flux densities vary over a wide time range from fractions of a microsecond to several years. They can be caused by various factors: both external (e.g., scintillation in the interstellar medium) and internal (flare activity, nulling, mode switching, etc., (see, e.g., the monographs of Manchester and Taylor 1977, Lorimer and Kramer 2004)). Despite a half-century of pulsar research, the mechanism of pulsar emission remains unknown. Therefore, the study of some peculiarities in their radiation, detected in new pulsars, can help to clarify some fundamental points of the emission mechanism and the structure of the magnetosphere of these sources.

Since 2014, a pulsar search program is carried out by the upgraded Large Phased Array (LPA) radio telescope in Pushchino Radio Astronomy Observatory, thereby the discovery of more than 70 new pulsars and rotating radio transients (RRATs) (Tyul’bashev and Tyul’bashev 2015, Tyul’bashev and Tyul’bashev 2015, Tyul’bashev et al. 2016, Tyul’bashev et al. 2017, Tyul’bashev et al. 2018, Tyul’bashev et al. 2018, Tyul’bashev et al. 2020) has been made. The Pushchino pulsar search program is based on daily round-the-clock monitoring of a large area of the sky (

2 Observations

The observations were carried out in the Pushchino Radio Astronomy Observatory at a frequency of 111 MHz using the meridian radio telescope LPA. Its antenna is the phased array composed of 16,384 dipoles. The geometric area of this antenna is about

3 Results

3.1 J0220+3622, pulsar with the subpulse drift

Subpulse drift is a sequence of individual pulse/subpulse shifting in phase from one edge of the mean pulse profile to the opposite, forming characteristic drift bands on the longitude-time diagram (Drake and Craft 1968). This phenomenon is characterized by two periods: second (

The pulsar J0220+36 with the period

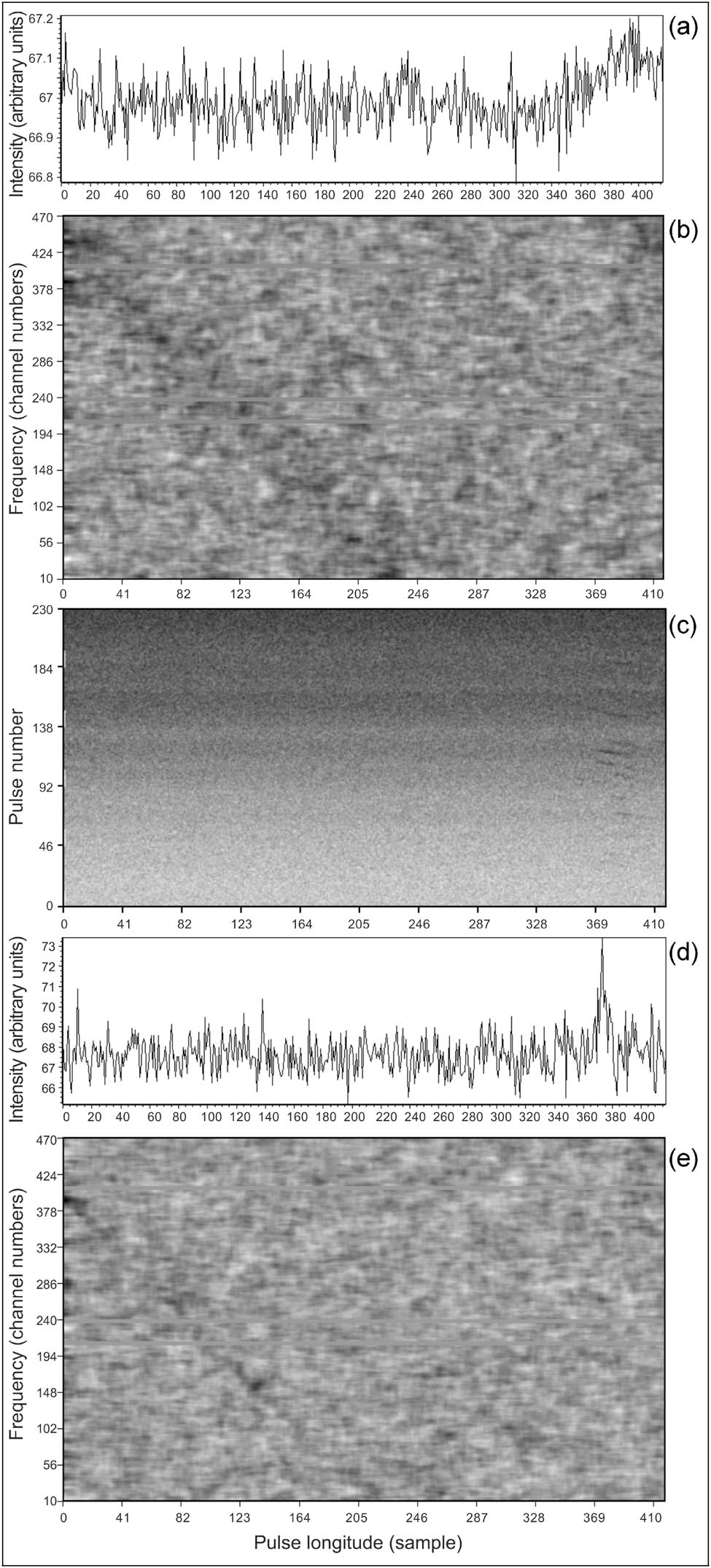

The example of observations for pulsar J0220+36 (2 January 2018). From top to bottom: (a) integrated pulse profile, (b) dynamic spectrum, (c) variations of pulse intensity during one observation session (230 pulses), (d) example of individual pulse profile, and (e) dynamic spectrum for individual pulse. The abscissa axis for all graphs shows pulse period (one sample is equal to 2.46 ms).

(a) The integrated profile of the observed pulsar; (b) the pulse intensity dependence for the 100 periods, drift of the strong pulses is visible; (c) pulse profile of one of three strong individual pulses.

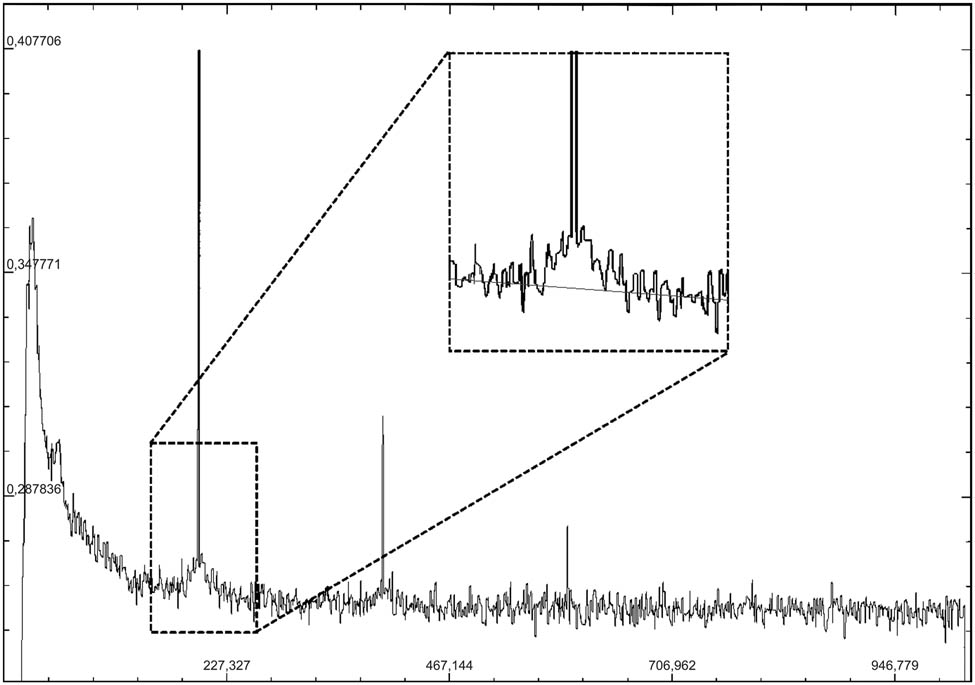

The summed Fourier spectrum of J0220+36 obtained by accumulation of more than 500 daily Fourier spectra.

The examples of the drift for J0220+36 on different observation days.

3.2 J0303+2248 pulsar with flare activity

The pulsar J0303+2248 (Tyul’bashev and Tyul’bashev 2015) discovered with

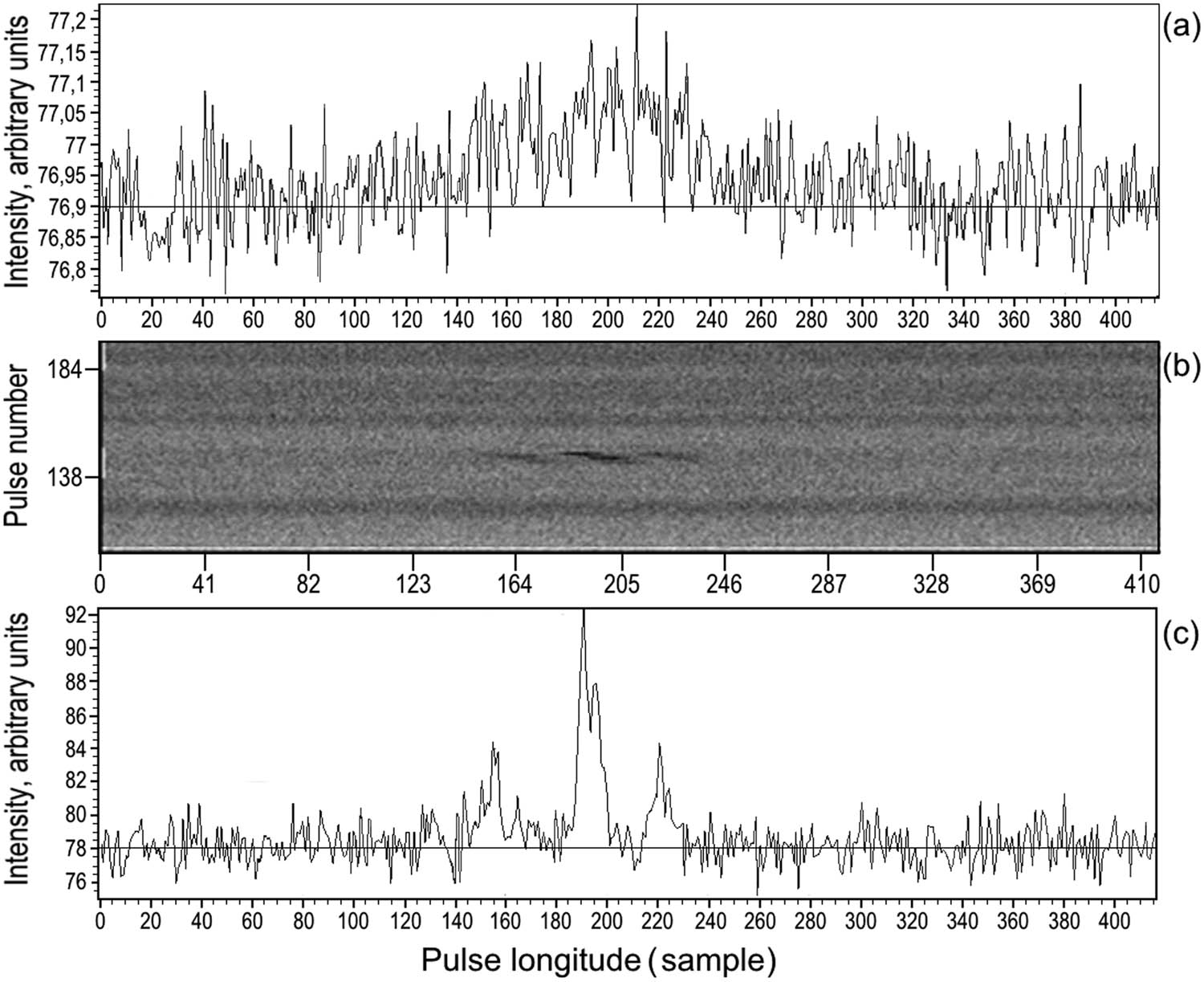

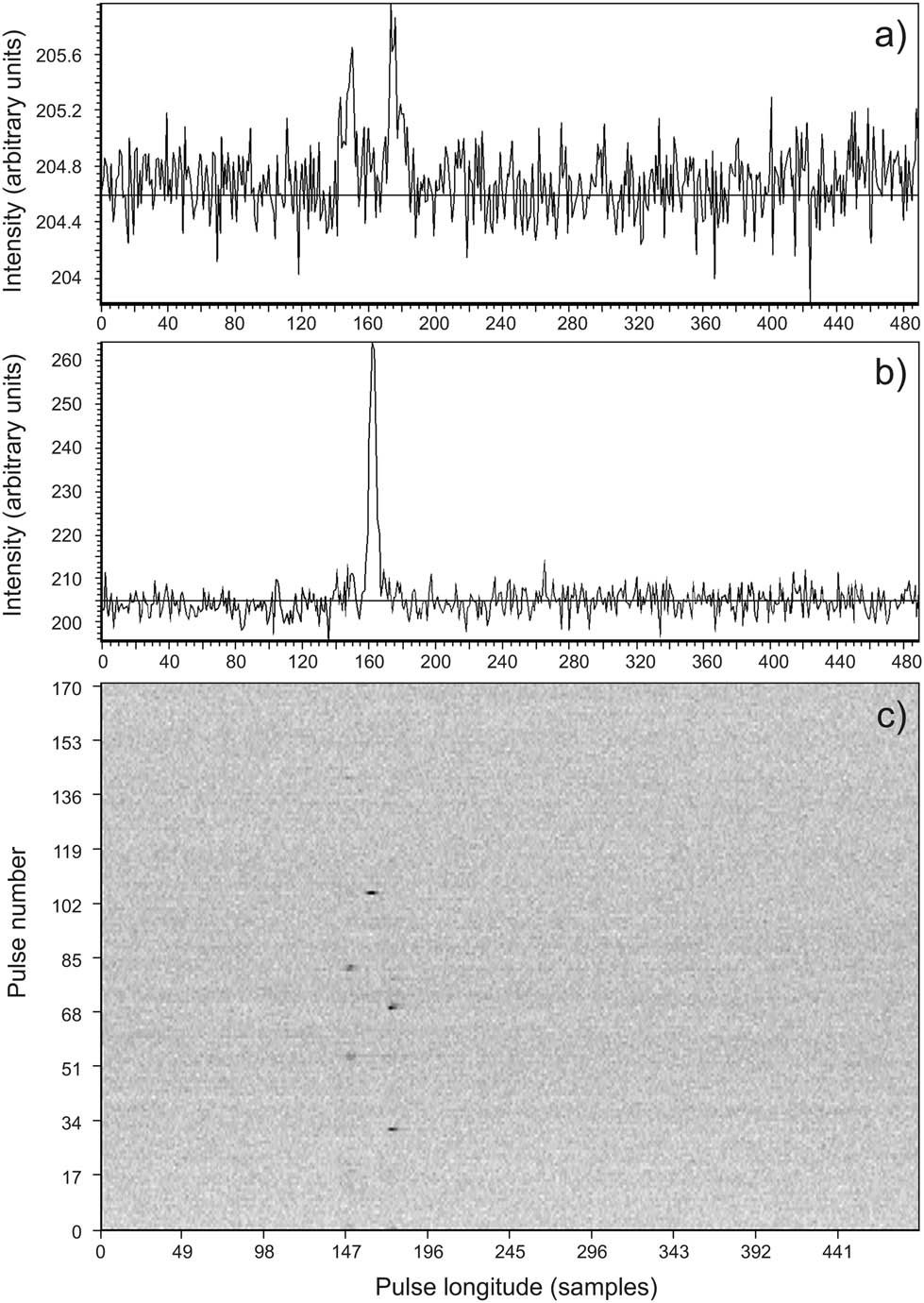

A more detailed study showed that the pulsar J0303+2248 exhibits powerful single pulses, and its emission is more similar to radiation from transient sources (RRATs), but with more frequent pulses. This pulsar has a two-component pulse structure with rare and weak inter-component emission. There is practically no radiation outside strong pulses. Figure 5 shows the sum of the eight strongest individual pulses. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of this summed pulse is five times more than the S/N for sum of other 160 pulses. Some individual pulses are ten times stronger than the integrated pulse. The annual variations of the radio emission show that the signal has been recorded at the level S/N = 3–7 in most of the observation sessions. But we can see the increase in signal on some days. Also, this object shows a very rare phenomenon (one event during 146 days of observations). It is a flare in the inter-component space (Figure 6). A similar behavior was found earlier for the pulsar J0653 + 8041 (Malofeev et al. 2016), where the central component flares were observed very rarely in the three-component profile. We obtained more precise value of the DM for J0303+2248, it was

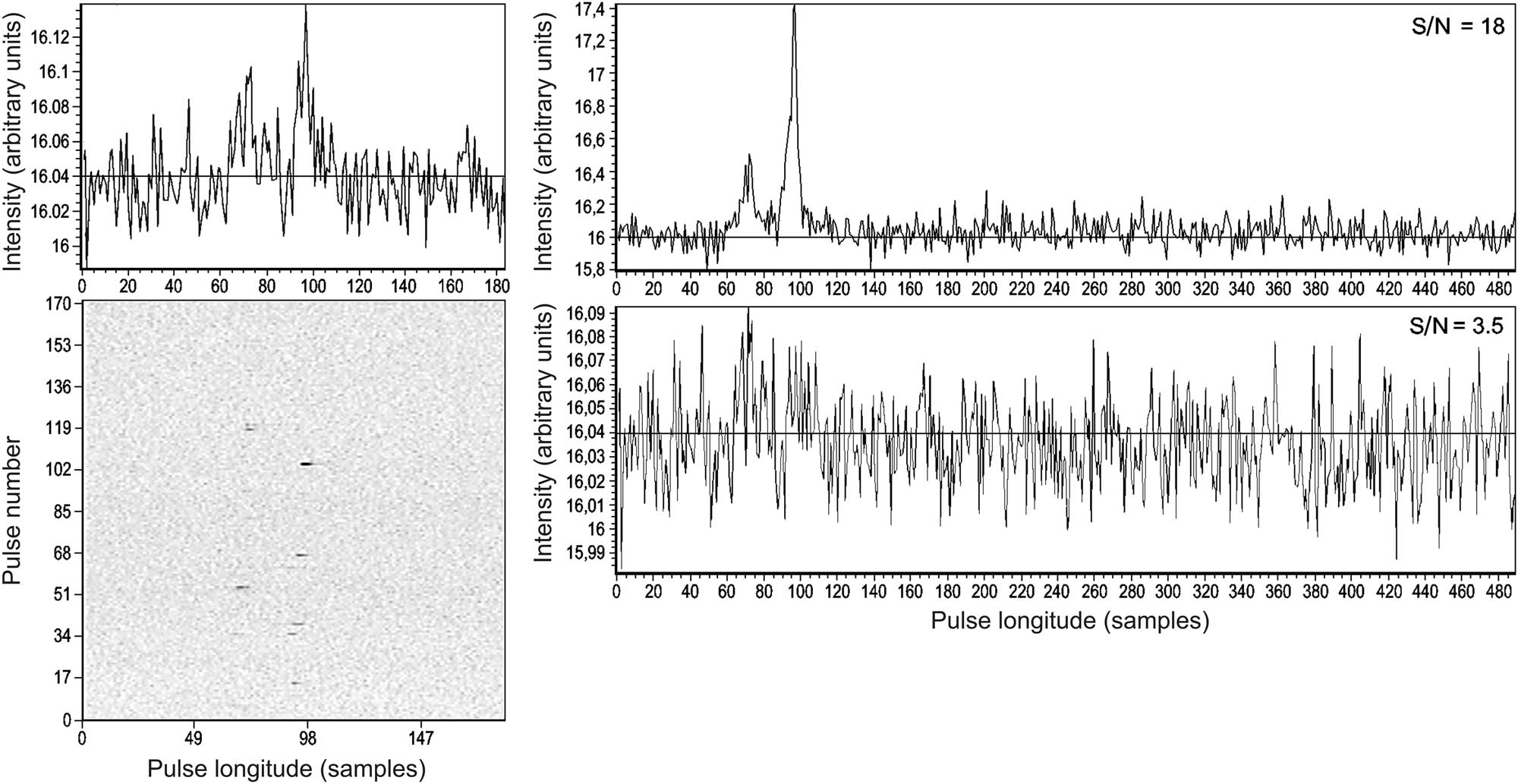

The example of observations of J0303+22 (25 January 2019). The integrated pulse profile (top left) and intensity changes of the pulsar pulses during one observation session (bottom left). The pulse profiles of a pulsar obtained by summing eight strong pulses with

The inter-component emission detection from J0330+2248 (13 January 2018). (a) The integral pulse profile, (b) profile of the individual pulse (number 105) with S/N = 20.5 corresponding to inter-component emission, and (c) the intensity changes of the pulses during the observation session.

3.3 J0810+3725 – nulling pulsar

The nulling is a phenomenon when we can observe a temporary absence of pulsed emission from a neutron star (Backer 1970). Long-term studies of this phenomenon have shown that the percentage of nulling fraction (NF) can vary in range 1–90% (Wang et al. 2007, Gajjar et al. 2014, Burgay et al. 2019). Intermittent pulsars belong to the separate class of objects switching off their emission for a longer time (from several days to several years) (Kramer et al. 2006, Camilo et al. 2012).

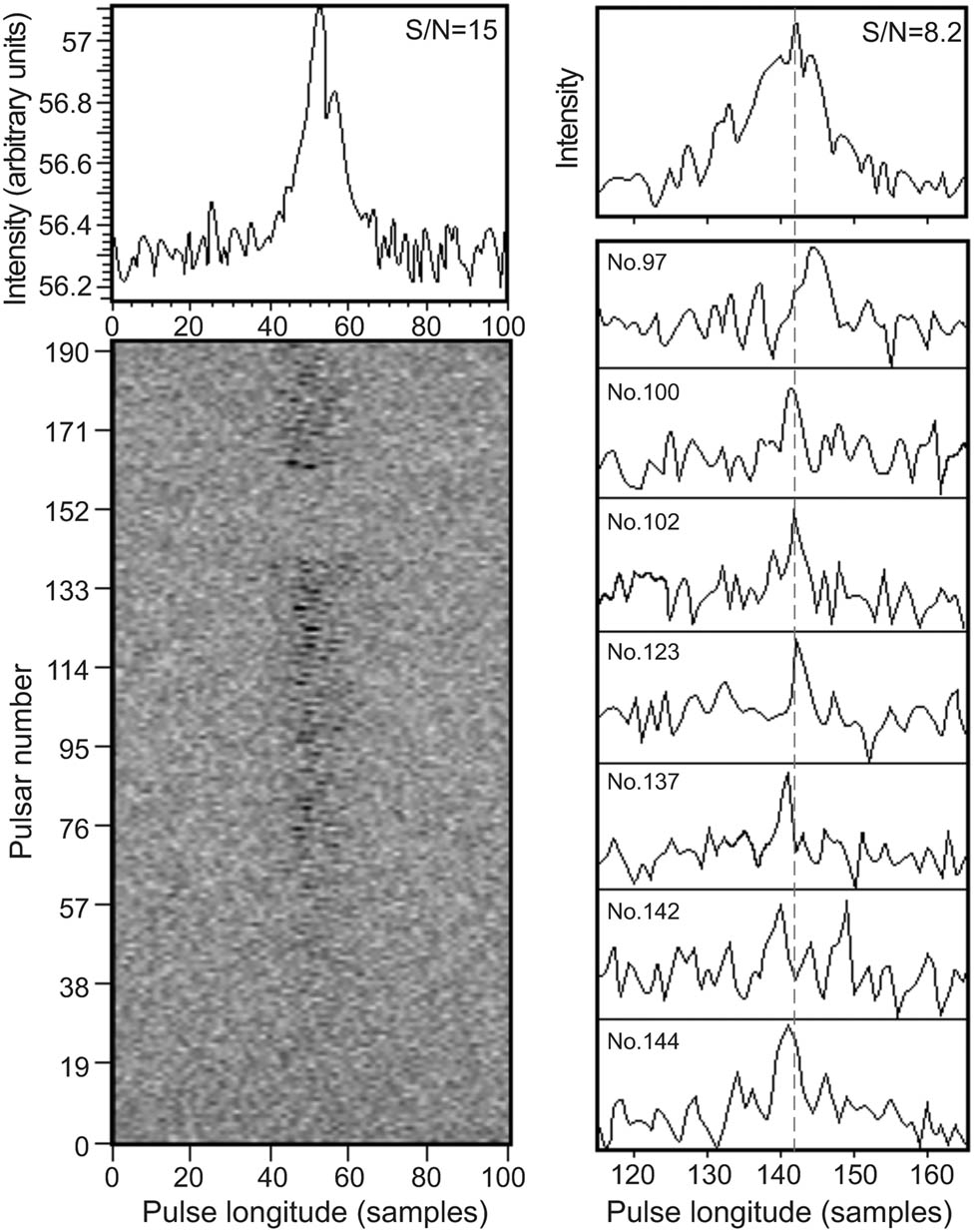

The preliminary results of the J0810+3725 study were presented in previous study (Teplykh and Malofeev 2019). The pulsar with

The example of the pulse profile of J0810+37 and the intensity of individual pulses during one observation session (left), and examples of individual pulse profiles (right).

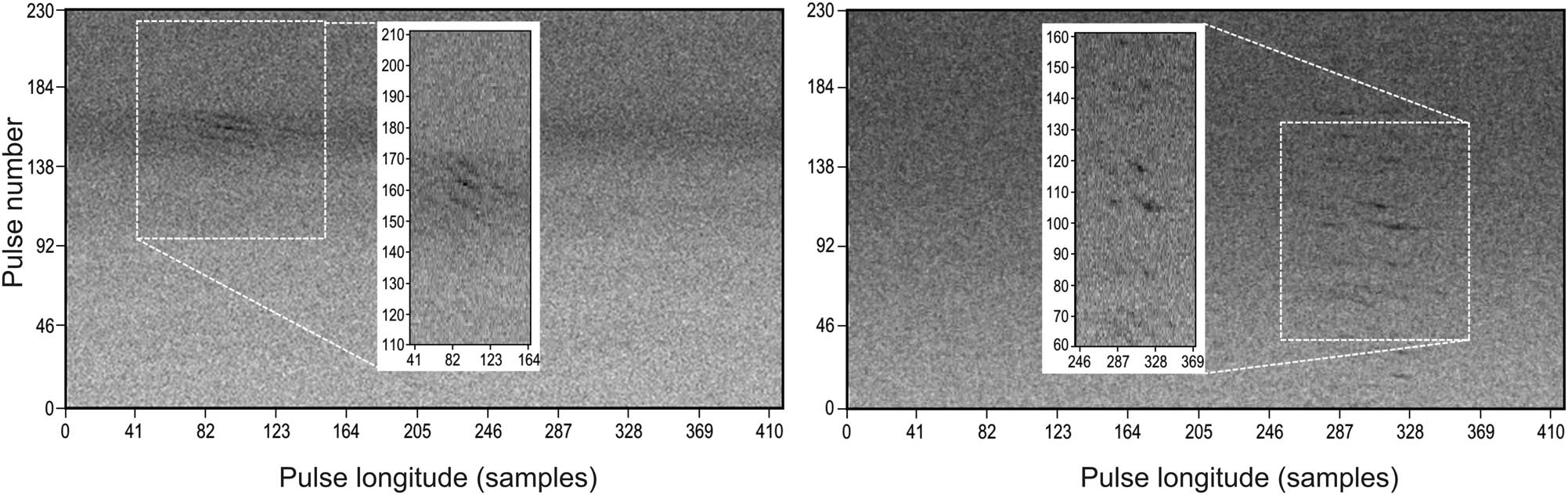

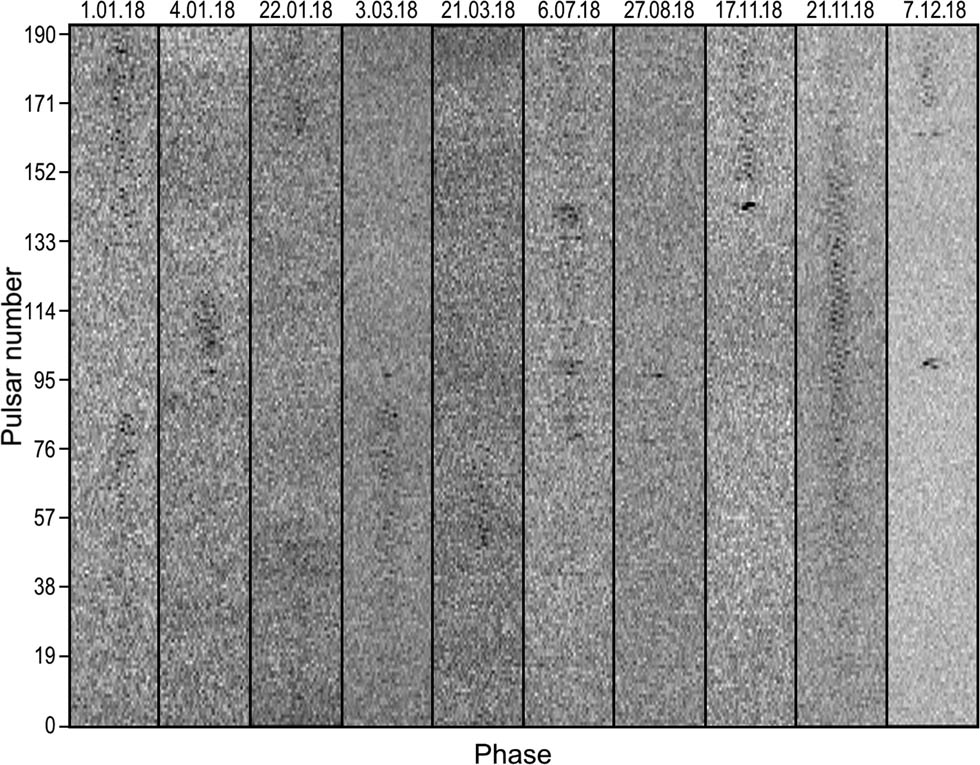

Examples of nulling for the pulsar J0810+3725 are shown in Figure 8. In active state (during periods of “switch on”) the pulsar demonstrates a wide spread of nulling durations (10–90% of the observation session time) and in average is 40% (Teplykh and Malofeev 2019). During some days (Figures 7 and 8) we can see the allusion that this pulsar has a subpulse drift. We shall try to estimate

The examples of nulling for the pulsar J0810+37 on different observation days.

4 Conclusion

The detailed analysis of the study of radio emission from new pulsars is carried out. As expected, the Pushchino search program is sensitive to sources with peculiar emissions. Some of the new objects have interesting radio emission features such as nulling, subpulse drift, and flare activity.

Pulsar J0220+3622 demonstrates the subpulse drift with a variable drift rate. Pulsar J0303+2248 has the flare activity and very rare case of the flare in the inter-component space.

Pulsar J0810+3725 shows the intermediate nulling phenomenon with the visible subpulse drift.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Backer DC. 1970. Pulsar nulling phenomena. Nature. 228:42–43. 10.1038/228042a0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Burgay M, Stappers B, Bailes M, Barr ED, Bates S, Bhat ND, et al. 2019. The high time resolution universe pulsar survey-XV. Completion of the intermediate-latitude survey with the discovery and timing of 25 further pulsars. MNRAS. 484:5791–5801. 10.1093/mnras/stz401Suche in Google Scholar

Deshpande AA, Rankin JM. 1999. Pulsar magnetospheric emission mapping: Images and implications of polar cap weather. ApJ. 524:1008. 10.1086/307862Suche in Google Scholar

Drake FD, Craft HD. 1968. Second periodic pulsation in pulsars. Nature. 220:231–235. 10.1038/220231a0Suche in Google Scholar

Gajjar V, Joshi BC, Wright G. 2014. On the long nulls of PSRs J1738âĹŠ 2330 and J1752. 2359. MNRAS. 439:221–233. 10.1093/mnras/stt2389Suche in Google Scholar

Camilo F, Ransom SM, Chatterjee S, Johnston S, Demorest P. 2012. PSR J1841-0500: a radio pulsar that mostly is not there. ApJ. 746:63. 10.1088/0004-637X/746/1/63Suche in Google Scholar

Filippenko AV, Radhakrishnan V. 1982. Pulsar nulling and drifting subpulse phase memory. ApJ. 263:828. 10.1086/160553Suche in Google Scholar

Gil J, Melikidze, GI, Geppert U. 2003. Drifting subpulses and inner acceleration regions in radio pulsars. A&A. 407:315–324. 10.1051/0004-6361:20030854Suche in Google Scholar

Huguenin GR, Taylor JH, Troland TH. 1970. The radio emission from pulsar MP 0031-07. ApJ. 162:727. 10.1086/150704Suche in Google Scholar

Kramer M, Lyne AG, O’Brien JT, Jordan CA, Lorimer DR. 2006. A periodically active pulsar giving insight into magnetospheric physics. Science. 312:549–551. 10.1126/science.1124060Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lorimer DR, Kramer M. 2004. Handbook of pulsar astronomy, Cambridge observing handbooks for research astronomers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Suche in Google Scholar

Malofeev VM, Teplykh DA, Logvinenko SV. 2012. New observations of anomalous X-ray pulsars at low frequencies. Astron Rep. 56:35–44. 10.1134/S1063772912010052Suche in Google Scholar

Malofeev VM, Teplykh DA, Malov OI, Logvinenko SV. 2016. Flare activity of PSR J0653. 8051. MNRAS. 457:538–541. 10.1093/mnras/stv2477Suche in Google Scholar

Malofeev VM, Tyul’bashev SA. 2018. Investigation of radio pulsar emission features using power spectra. RAA. 18:096. 10.1088/1674-4527/18/8/96Suche in Google Scholar

Manchester RN, Taylor JH. 1977. Pulsars, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. Suche in Google Scholar

McLaughlin MA, Lyne AG, Lorimer DR, Kramer M, Faulkner AJ, Manchester RN. 2006. Transient radio bursts from rotating neutron stars. Nature. 439:817–820. 10.1038/nature04440Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Rankin JM. 1986. Toward an empirical theory of pulsar emission. III-Mode changing, drifting subpulses, and pulse nulling. ApJ. 301:901–922. 10.1086/163955Suche in Google Scholar

Ruderman MA, Sutherland PG. 1975. Theory of pulsars-polar caps, sparks, and coherent microwave radiation. ApJ. 196:51–72. 10.1086/153393Suche in Google Scholar

Sutton JM, Staelin DH, Price RM. 1971. Individual Radio Pulses from NP 0531. In: Davies RD, Smith FG, Editors. The Crab Nebula. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 97–102. 10.1007/978-94-010-3087-8_13Suche in Google Scholar

Teplykh DA, Malofeev VM. 2019. Nulling phenomenon of the new radio pulsar J0810. 37 at a frequency of 111MHz. Bull Lebedev Phys Inst. 46:380–382. 10.3103/S1068335619120030Suche in Google Scholar

Teplykh D, Malofeev V, Malov O. 2020. The features of PSR J0220. 3622 radio emission. In: Ground-Based Astronomy in Russia. 21st Century. p. 446–450. 10.26119/978-5-6045062-0-2_2020_446Suche in Google Scholar

Tyul’bashev SA, Tyul’bashev VS. 2015. The discovery of new pulsars on the BSA LPI radio telescope. I. Astronomicheskij Tsirkulyar. 1624:1–4. Suche in Google Scholar

Tyul’bashev SA, Tyul’bashev VS. 2015. The discovery of new pulsars on the BSA LPI radio telescope. II. Astronomicheskij Tsirkulyar. 1625:1–4. Suche in Google Scholar

Tyul’bashev SA, Tyul’bashev VS, Oreshko VV, Logvinenko SV. 2016. Detection of new pulsars at 111 MHz. Astron Rep. 60:220–232. 10.1134/S1063772916020128Suche in Google Scholar

Tyul’bashev SA, Tyul’bashev VS, Kitaeva MA, Chernyshova AI, Malofeev VM, Chashei IV, et al. 2017. Search for and detection of pulsars in monitoring observations at 111 MHz. Astron Rep. 61:848–858. 10.1134/S1063772917100109Suche in Google Scholar

Tyul’bashev SA, Tyul’bashev VS, Malofeev VM, Logvinenko SV, Oreshko VV, Dagkesamanskii RD, et al. 2018. Detection of five new RRATs at 111 MHz. Astron Rep. 62:63–71. 10.1134/S1063772918010079Suche in Google Scholar

Tyul’bashev SA, Tyul’bashev VS, Malofeev VM. 2018. Detection of 25 new rotating radio transients at 111 MHz. A&A. 618:A70. 10.1051/0004-6361/201833102Suche in Google Scholar

Tyul’bashev SA, Kitaeva MA, Tyul’bashev VS, Malofeev VM, Tyul’basheva GE. 2020. Detection of five new pulsars with the BSA LPI radio telescope. Astron Rep. 64:526–532. 10.1134/S1063772920060074Suche in Google Scholar

Wang N, Manchester RN, Johnston S. 2007. Pulsar nulling and mode changing. MNRAS. 377:1383–1392. 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11703.xSuche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Daria Teplykh et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm