Abstract

Multiphase astrochemical modeling presents a numerical challenge especially for the simulation of objects with the wide range of physical parameters such as protoplanetary disks. We demonstrate an implementation of the analytical Jacobian for the numerical integration of the system of differential rate equations that govern chemical evolution in star-forming regions. The analytical Jacobian allowed us to greatly improve the stability of the code in protoplanetary disk conditions. We utilize the MONACO code to study the evolution of abundances of chemical species in protoplanetary disks. The chemical model includes 670 species and 6,015 reactions in the gas phase and on interstellar grains. The specific feature of the utilized chemical model is the inclusion of low-temperature chemical processes leading to the formation of complex organic molecules (COMs), included previously in the models of chemistry of COMs in prestellar clouds. To test the impact of analytical Jacobian on the stability of numerical simulations of chemical evolution in protoplanetary disks, we calculated the chemical composition of the disk using a two-phase model and four variants of the chemical reaction network, three values of the surface diffusion rates, and two types of the initial chemical composition. We also show a preliminary implementation of the analytical Jacobian to a three-phase model.

1 Introduction

Studies of the chemical composition of objects in the interstellar medium, especially for the content of complex organic molecules (COM), is an important prerequisite for understanding the origin of life in the Universe. Protoplanetary disks are dust- and gas-rich objects that could possibly form planetary systems. They are ubiquitous around young low-mass stars (e.g., Manara et al. 2016, Kim et al. 2017). A study of the chemical composition in the disks around Sun-like stars will provide an idea of the origin of organic molecules in the early Solar System, which in turn can serve as a key to understanding the early chemical composition of the Earth and other planets.

To date, complex organic molecules (which are defined to have six or more atoms, including carbon, Herbst and van Dishoeck 2009) such as methanol (

Aikawa et al. (1997) were among the first to study the evolution of the molecular composition of protoplanetary disks. They considered stationary minimum mass solar nebula (MMSN) without radial mixing; density and temperature did not change over time. Their chemical model included gas-phase reactions, adsorption onto dust grains, and thermal desorption from dust particles. Ionization and dissociation by interstellar and stellar ultraviolet radiation were neglected. The chemical network of reactions was based on the UMIST94 database (Millar et al. 1991).

Over the next 20 years, protoplanetary disk models became more sophisticated (e.g., see review by Henning and Semenov 2013). However, the applied chemical models remained mostly two phase, that is, only gas–grain interactions were considered. Ruaud and Gorti (2019) were able to apply the three-phase chemical model to protoplanetary disks for the first time.

In this article, for the first time, we apply a scenario of the formation of complex organic molecules in cold gas of prestellar cores proposed by Vasyunin and Herbst (2013) and further developed by Vasyunin et al. (2017) to a protoplanetary disk around a Sun-like star. The evolution of the chemical composition was calculated for 1 Myr assuming that the disk structure is in a quasi-stationary mode for a given time period (Akimkin et al. 2013).

To numerically solve the system of differential equations that determine chemical evolution, the three-phase MONACO code uses the DVODE integrator (Brown et al. 1989). In the current state, the application of the MONACO code to protoplanetary disks is challenging due to a wide range of physical conditions typical for disks. Numerical integration of a system of ordinary differential equations requires the calculation of the Jacoian matrix of the system. The DVODE can work in two regimes: with internally generated numerical Jacobian and with user-supplied analytical Jacobian. The latter option typically results in much higher numerical stability of integration. On the other hand, it requires additional efforts from researcher aimed at derivation and implementation of the analytical expressions for the Jacobian matrix into the numerical code. To solve this problem, we added to the code the implementation of specifying the analytical Jacobian of the system of differential equations.

In this study, we set the following goals: by supplying the analytical Jacobian, to increase the stability of the MONACO code for efficiently calculating the evolution of the chemical composition of the protoplanetary disk under the wide range of physical parameters and conditions typical of protoplanetary disks. Also, we aim to study the formation of COMs in the disk, especially midplane, using the model suggested by Vasyunin and Herbst (2013) tested on prestellar cores, the conditions that are close to the conditions in midplane.

2 Models

2.1 Physical model of the protoplanetary disk

As a physical model of a protoplanetary disk (PPD), we used the model presented by Molyarova et al. (2017). This model is the PPD model around a T Tauri type star with the mass of

Parameters of the protoplanetary disk model

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of points of the radial grid | 55 |

| Number of points of the vertical grid | 80 |

| Inner grid boundary | 0.5 au |

| Outer grid boundary | 1000.0 au |

| Inner characteristic radius | 0.5 au |

| Outer characteristic radius | 100.0 au |

| Total mass of gas in the disk |

|

| Mass of the central star |

|

| Dust solid density |

|

|

|

0.01 |

| Dust-to-gas ratio |

|

Dust temperature in the upper disk is calculated using multifrequency ray tracing (RT) procedure for the stellar and background radiation similar to the study by Molyarova et al. (2018). RT is done in 2D in

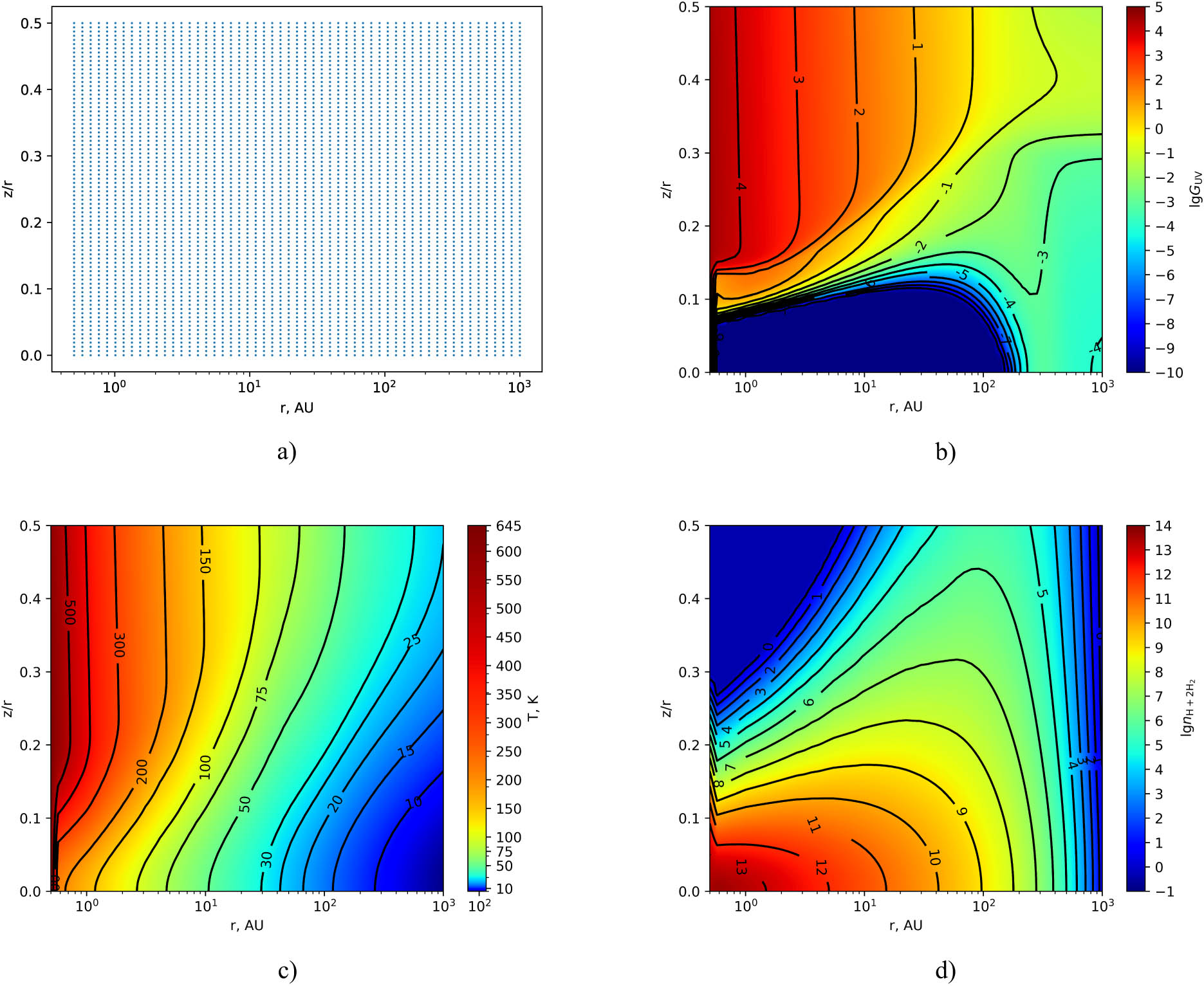

In Figure 1, the distributions of disk grid points (top left), the strength of UV radiation (top right), gas temperature (bottom left), and gas density (bottom right) in the disk (at each grid point) are also presented as a function of radial distance from the central star (

(a) Uniform distribution of disk grid points in coordinates of “radius–height” of the disk

2.2 Chemical model

In this study, we utilized a chemical model with the network of gas phase and surface chemical reactions, which was used in the study by Vasyunin and Herbst (2013) with an addition of a set of new gas-phase chemical reactions important for the formation of COMs presented in Vasyunin et al. (2017).

The chemical reaction network used in this model contains 670 species and 6,015 gas-phase and surface reactions, as well as 198 species and 880 reactions in the ice mantle of dust particles depending on the simulation mode (see details in Section 2.2.2). Following Vasyunin et al. (2017), we utilize five types of desorptions in the model: thermal evaporation, photodesorption, desorption by cosmic ray particles (CRP), CRP-driven photodesorption, and reactive desorption. We do not consider CRP attenuation inside the disk. Cosmic-ray ionization rate in our model is

In Table 2, the atomic initial fractional abundances of elements with respect to the total number of hydrogen nuclei used in the model are presented (according to Wakelam and Herbst 2008). The molecular initial composition is calculated as a result of the chemical evolution of a cold dark cloud at

The initial fractional abundances of reactants

| Reactants | Abundance |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| H |

|

| He |

|

| N |

|

| O |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The fractional abundances are given with respect to the total number of hydrogen nuclei.

We modified the chemical model to take into account the radiation fields from the central star and interstellar radiation according to the protoplanetary disk model. The rate constants of photoionization reactions

where

The grid points of the protoplanetary disk model are not independent in terms of calculating the evolution of the chemical composition because the self-shielding of the molecules

For the top points in each radial column (points with a maximum height above the disk midplane), the column densities

where

In the case of a three-phase model, the evolution of the molecular composition is determined by the following system of differential equations (Vasyunin et al. 2017):

Here,

For the numerical integration of the system of differential rate Eq. (3), the Adams method is used, implemented in the DVODE integrator. The integration time is 1 Myr.

2.2.1 Supplying the analytical Jacobian

When using a two-phase model (gas–grain) and a chemical network containing

The two-phase Jacobian is well described analytically with the exception of reactive desorption (

To obtain the symbolic Jacobian of such a system of ordinary differential equations, the SymPy symbolic computation package for the Python language was chosen. The process of numerically solving the system of equations is as follows. On the basis of the chemical reaction network, a system of differential equations in Fortran is formed, since the numerical solution is performed by means of this language. A system of differential equations in Python is also formed, but in a symbolic form. Then symbolic partial derivatives are calculated using SymPy. Then symbolic expressions are simplified. After that, the Python code forms the Fortran source code, and the system of differential equations is solved numerically.

2.2.2 Simulation setups

So far we have applied the following simulation setups:

Two phase (gas–grain) with reactive desorption taken into account, without specifying the Jacobian;

Two phase with reactive desorption taken into account, with specifying the Jacobian;

Three phase (gas–surface–mantle) with reactive desorption taken into account, without specifying the Jacobian;

“Incomplete” three phase with reactive desorption taken into account, with specifying the Jacobian.

In all setups, we used the type of reactive desorption according to Minissale et al. (2016). Each simulation approach we tested using four different chemical network options: network used in the study by Vasyunin and Herbst (2013); network with refined binding energies for some species; network that additionally includes reactant

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Two-phase setups

In total, in each two-phase approach (with and without Jacobian), we calculated 24 models of protoplanetary disks (4 variants of chemical networks, 3 different values of the surface chemistry parameter, and 2 variants of the initial chemical composition). Thus, 105,600 runs of the numerical integration of the differential equations system were performed in each of the two-phase modes under different physical conditions and different parameters of chemistry.

When using the Jacobian, the calculation speed increased by four to five times on average. The number of unsuccessfully completed calculations has decreased significantly, namely, by 150 times. Now that number is eight unsuccessful calculations out of 105,600 runs. Thus, we consider it reasonable to use the symbolic Jacobian in two-phase models with reactive desorption.

3.1.1 Distribution of organic molecules in the disk

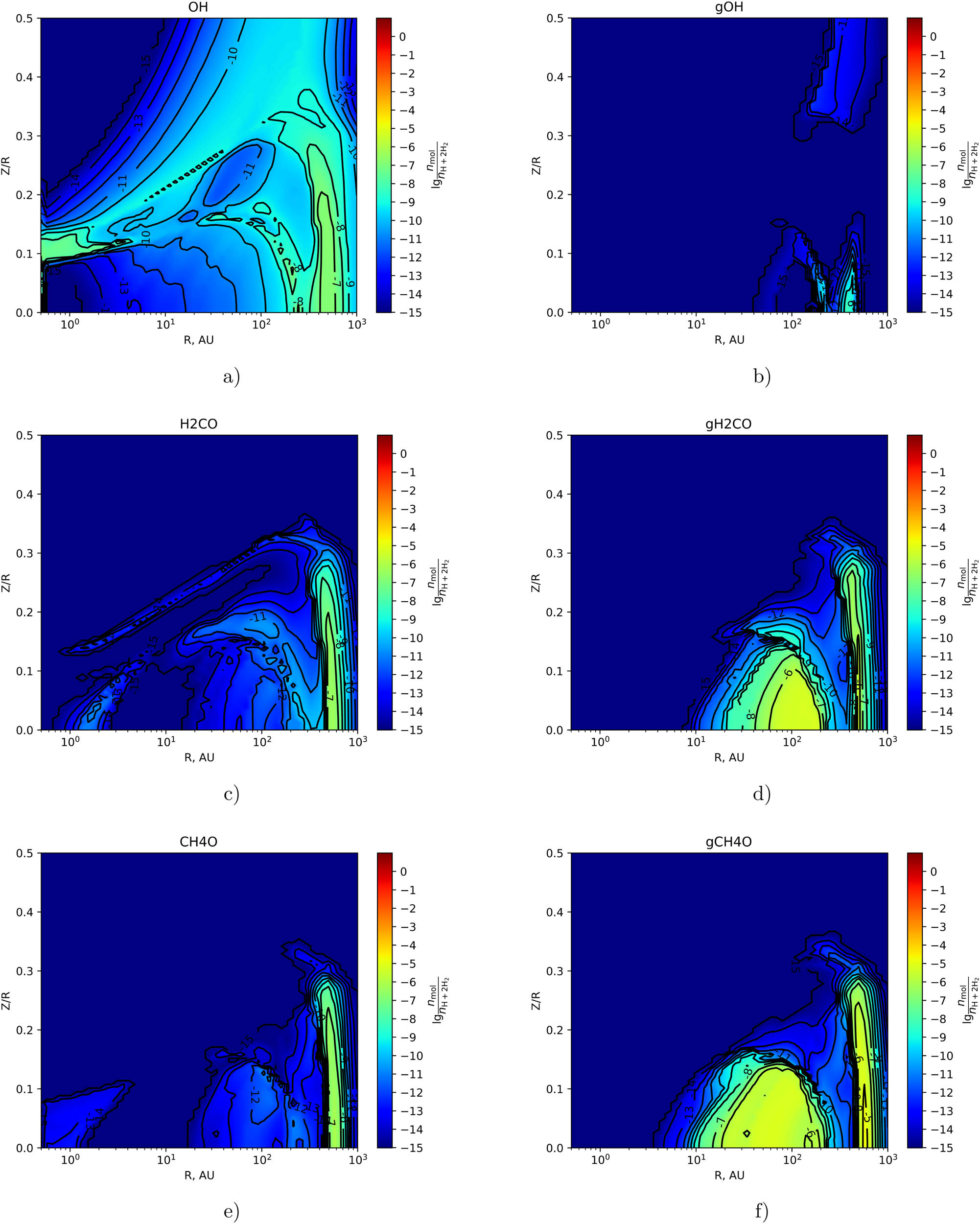

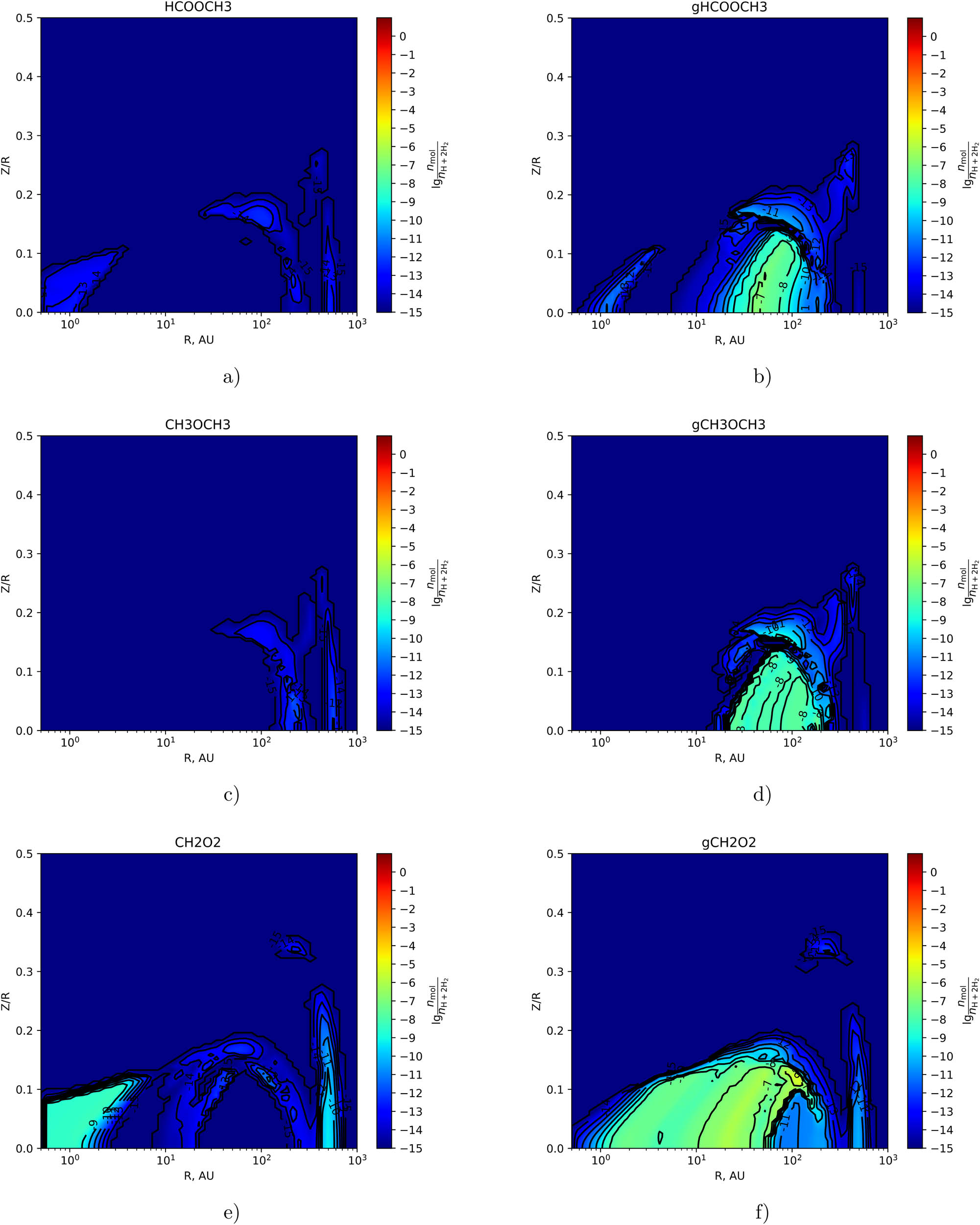

In this section, we present two-dimensional distributions of the fractional abundances of selected organic molecules and some chemically related species with respect to the total number of hydrogen nuclei in the disk in the gas phase and on the surface of dust particles at time

As shown in Figure 2(a) and (b), the relative hydrogen abundance of the hydroxyl group OH reaches

The two-dimensional distribution of the fractional abundance of OH (top row),

The maximum fractional abundance on the grain surfaces of

The two-dimensional distribution of the fractional abundance of

As follows from Figures 2(c)–3(f), the values of the maximum fractional abundances on the grain surfaces of

The main channel for the formation of COMs, in particular methanol, in this model consists of the sequential hydrogenation of CO on grains:

In our model, COMs are more efficiently formed in the midplane on grains. At 5–30 K and weak UV field, due to attenuation in the depth of the disk, CO in sufficiently large quantities can freeze out to grains. At high altitudes, CO is destroyed under the stronger UV field (

3.1.2 Total column densities of organic molecules

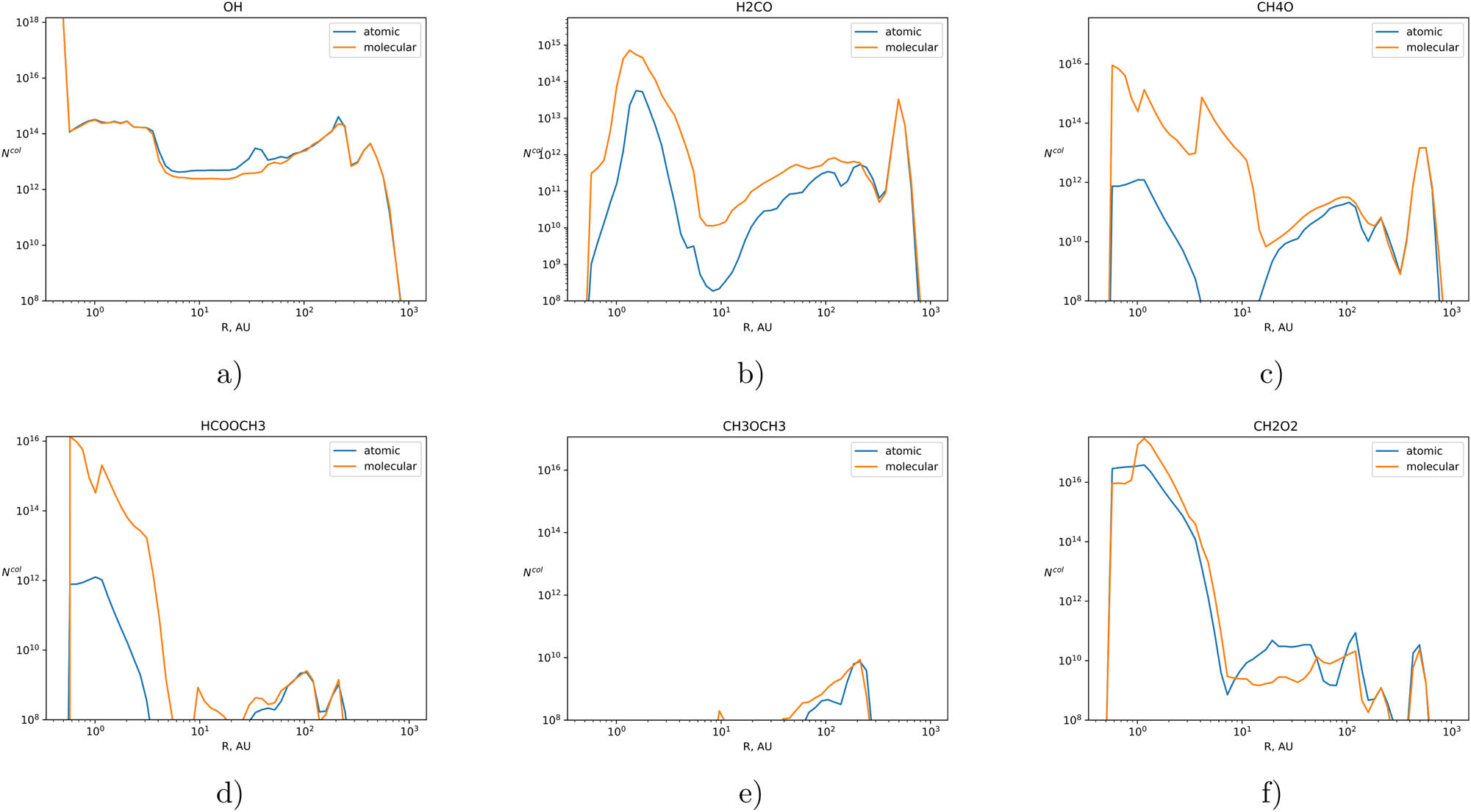

We also present the column densities profiles for selected molecules as a function of the disk radius (total number of molecules in the column) in

Total column densities in

In the work by Podio et al. (2019), estimates of the column densities for formaldehyde

In the work by Walsh et al. (2014), the model column densities of

As shown in Figure 4, the use of different variants of the initial chemical compositions has a significant impact on the simulation results, especially with regard to complex organic molecules. The approach in which the protoplanetary disk inherits its initial composition from the previous evolutionary stages of the protostar is more fair.

3.2 Three-phase setups

Work on adding the Jacobian to the three-phase model is ongoing. Currently, we have implemented the supplying of analytical Jacobian for the processes of instantaneous surface redefinition due to the adsorption/desorption of molecules from/to the gas phase from the surface. This added another 230,104 (31%) non-zero Jacobian elements. Such Jacobian obviously ceases to be sparse.

The use of the Jacobian of the differential equations system significantly affected the operation of the three-phase mode. In the three-phase mode without the Jacobian, the calculations for most of the grid points of the protoplanetary disk physical model do not complete successfully in a reasonable CPU time. The addition of the Jacobian to the “incomplete” three-phase regime significantly improved the stability and speed of calculations, but still does not allow us to calculate the chemical evolution in the inner disk. At the current moment in this mode, we were able to calculate the chemical composition for the outer regions of the disk with the radial distance from the central star of more than 25 au.

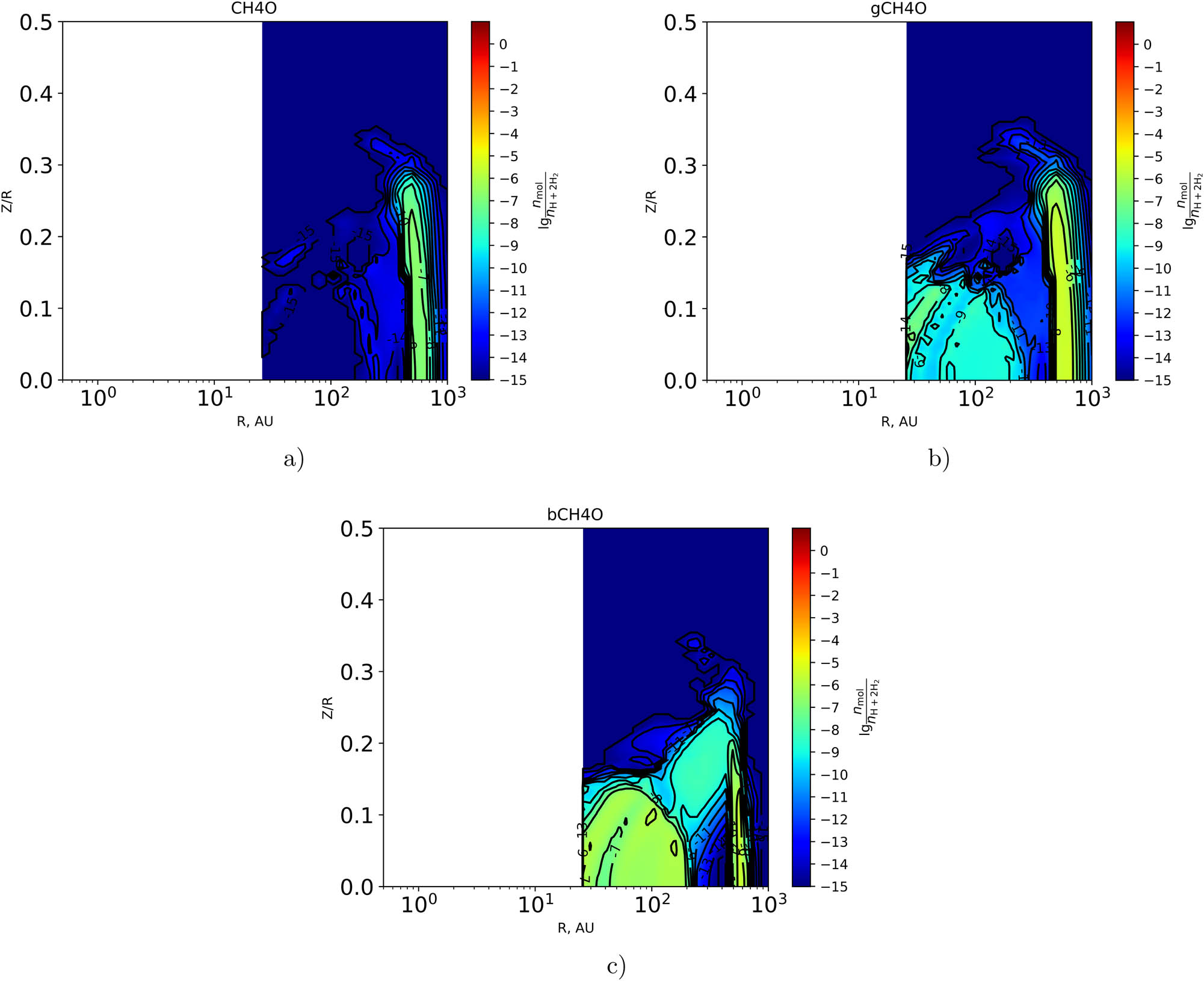

In the three-phase model, the molecules from the deep of ice mantle cannot be directly desorbed into the gas phase. “Incomplete” three-phase mode is an intermediate step toward “full” three-phase mode. In the “incomplete” mode, there is no physical transfer of molecules between the mantle and the surface. Mantle molecules can become surface molecules only by emptying the upper layers of the surface. Therefore, the results obtained in this mode must be treated with caution. Nevertheless, using the example of methanol (Figure 5), it can be seen that the abundances in the gas phase and on the grain surfaces in the area accessible to us (especially in midplane) have become several orders of magnitude lower compared to the two-phase regime (Figure 2(e) and (f)). Obviously, this is achieved due to the settling of species deep into the bulk. Hence, the presence of the third solid phase in the chemical model has a significant effect on the abundance of molecules in the gas phase.

The two-dimensional distribution of the fractional abundance of

4 Summary

We have implemented an option to supply the analytical Jacobian in the MONACO code for the chemical evolution of interstellar objects, which was previously applied to cold dark clouds and applied it for the first time to the physical model of the protoplanetary disk around a Sun-like star. Specifying the Jacobian for the two-phase (gas–grain) model made it possible to reduce the time of numerical integration of the differential equations system, as well as to increase the stability and accuracy of calculations as applied to the protoplanetary disk.

We also present preliminary results on adding the Jacobian to the three-phase (gas-surface-bulk) model, the intermediate results of which also demonstrated the justification and the necessity of using the Jacobian in modeling the formation of complex organic molecules in protoplanetary disks using the MONACO code. This update is crucial to allow numerically effective modeling of three-phase chemistry in protoplanetary disk conditions.

-

Funding information: MYK and AIV acknowledge the support Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation via the State Assignment contract FEUZ-2020-0038. VVA is grateful to the Foundation for the Advancement of Theoretical Physics and Mathematics “BASIS” for financial support (20-1-2-20-1).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aikawa Y, Umebayashi T, Nakano T, Miyama SM. 1997. Evolution of molecular abundance in protoplanetary disks. ApJ. 486(1):L51–L54. 10.1086/310837. Suche in Google Scholar

Akimkin V, Zhukovska S, Wiebe D, Semenov D, Pavlyuchenkov Y, Vasyunin A, et al. 2013. Protoplanetary disk structure with grain evolution: The ANDES model. ApJ. 766(1):8. 10.1088/0004-637X/766/1/8. Suche in Google Scholar

Baraffe I, Homeier D, Allard F, Chabrier G. 2015. New evolutionary models for pre-main sequence and main sequence low-mass stars down to the hydrogen-burning limit. Astron Astrophys. 577:A42. 10.1051/0004-6361/201425481. Suche in Google Scholar

Bergner JB, Guzmán VG, Öberg KI, Loomis RA, Pegues J. 2018. A survey of CH3CN and HC3N in protoplanetary disks. ApJ. 857:69. 10.3847/1538-4357/aab664. Suche in Google Scholar

Brown PN, Byrne GD, Hindmarsh AC. 1989. VODE: A variable-coefficient ODE solver. SIAM J Sci Stat Comput. 10(5):1038–1051. 10.1137/0910062. Suche in Google Scholar

Draine BT. 1978. Photoelectric heating of interstellar gas. ApJ Suppl Ser. 36:595–619. 10.1086/190513. Suche in Google Scholar

Favre C, Fedele D, Semenov D, Parfenov S, Codella C, Ceccarelli C, et al. 2018. First detection of the simplest organic acid in a protoplanetary disk. ApJ Lett. 862:L2. 10.3847/2041-8213/aad046. Suche in Google Scholar

Garrod RT, Wakelam V, Herbst E. 2007. Non-thermal desorption from interstellar dust grains via exothermic surface reactions. Astron Astrophys. 467(3):1103–1115. 10.1051/0004-6361:20066704. Suche in Google Scholar

Glassgold AE, Langer WD. 1974. Model calculations for diffuse molecular clouds. ApJ. 193:73–91. 10.1086/153130. Suche in Google Scholar

Henning T, Semenov D. 2013. Chemistry in protoplanetary disks. Chem Rev. 113(12):9016–9042. 10.1021/cr400128p. Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Herbst E, van Dishoeck EF. 2009. Complex organic interstellar molecules. Annu Rev Astron Astr. 47:427–480. 10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101654. Suche in Google Scholar

Jiménez-Serra I, Vasyunin AI, Caselli P, Marcelino N, Billot N, Viti S, et al. 2016. The spatial distribution of complex organic molecules in the L1544 pre-stellar core. ApJ Lett. 830(1):L6. 10.3847/2041-8205/830/1/L6. Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Jorgensen JK, PILS Team. 2020. The ALMA-PILS Survey: New insights into the complex chemistry of young stars. Proc Int Astron Union. 345:132–136. 10.1017/S1743921319002849. Suche in Google Scholar

Kama M, Bruderer S, van Dishoeck EF, Hogerheijde M, Folsom CP, Miotello A, et al. 2016. Volatile-carbon locking and release in protoplanetary disks-A study of TW Hya and HD 100546. Astron Astrophys. 592:A83. 10.1051/0004-6361/201526991. Suche in Google Scholar

Kim JS, Fang M, Clarke CJ, Facchini S, Pascucci I, Apai D, et al. 2017. Young stellar objects & photoevaporating protoplanetary disks in the Orionas sibling NGC 1977. Mem S.A.It. 88:790. Suche in Google Scholar

Lee JE, Lee S, Baek G, Aikawa Y, Cieza L, Yoon SY, et al. 2019. The ice composition in the disk around V883 Ori revealed by its stellar outburst. Nat Astron. 3(4):314–319. 10.1038/s41550-018-0680-0. Suche in Google Scholar

Manara CF, Rosotti G, Testi L, Natta A, Alcalá JM, Williams JP, et al. 2016. Evidence for a correlation between mass accretion rates onto young stars and the mass of their protoplanetary disks. Astron Astrophys. 591:L3. 10.1051/0004-6361/201628549. Suche in Google Scholar

Manigand S, Jørgensen JK, Calcutt H, Müller HSP, Ligterink NFW, Coutens A, et al. 2020. The ALMA-PILS survey: inventory of complex organic molecules towards IRAS 16293-2422 A. Astron Astrophys. 635:A48. 10.1051/0004-6361/201936299. Suche in Google Scholar

McElroy D, Walsh C, Markwick AJ, Cordiner MA, Smith K, Millar TJ. 2013. The UMIST database for astrochemistry 2012. Astron Astrophys. 550:A36. 10.1051/0004-6361/201220465. Suche in Google Scholar

Millar TJ, Bennett A, Rawlings JMC, Brown PD, Charnley SB. 1991. Gas phase reactions and rate coefficients for use in astrochemistry-The UMIST ratefile. ApJ Suppl Ser. 87:585–619. Suche in Google Scholar

Minissale M, Dulieu F, Cazaux S, Hocuk S. 2016. Dust as interstellar catalyst-I. Quantifying the chemical desorption process. Astron Astrophys. 585:A24. 10.1051/0004-6361/201525981. Suche in Google Scholar

Molyarova T, Akimkin V, Semenov D, Henning T, Vasyunin A, Wiebe D. 2017. Gas mass tracers in protoplanetary disks: CO is still the best. ApJ. 849(2):130. 10.3847/1538-4357/aa9227. Suche in Google Scholar

Molyarova T, Akimkin V, Semenov D, Ábrahám P, Henning T, Kóspál Á, et al. 2018. Chemical signatures of the FU Ori outbursts. ApJ. 866(1):46. 10.3847/1538-4357/aadfd9. Suche in Google Scholar

Öberg KI, Guzmán VV, Furuya K, Qi C, Aikawa Y, Andrews SM, et al. 2015. The comet-like composition of a protoplanetary disk as revealed by complex cyanides. Nature. 520(7546):198–201. 10.1038/nature14276. Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Öberg KI, Guzmán VV, Merchantz CJ, Qi C, Andrews SM, Cleeves LI, et al. H2CO distribution and formation in the TW HYA disk. 2017. ApJ. 839(1):43. 10.3847/1538-4357/aa689a. Suche in Google Scholar

Podio L, Bacciotti F, Fedele D, Favre C, Codella C, Rygl KLJ, et al. 2019. Organic molecules in the protoplanetary disk of DG Tauri revealed by ALMA. Astron Astrophys. 623:L6. 10.1051/0004-6361/201834475. Suche in Google Scholar

Ruaud M, Gorti U. 2019. A three-phase approach to grain surface chemistry in protoplanetary disks: Gas, ice surfaces, and ice mantles of dust grains. ApJ. 885(2):146. 10.3847/1538-4357/ab4996. Suche in Google Scholar

Umebayashi T, Nakano T. 2009. Effects of radionuclides on the ionization state of protoplanetary disks and dense cloud cores. ApJ. 690(1):69–81. 10.1088/0004-637X/690/1/69. Suche in Google Scholar

Vasyunin AI, Herbst E. 2013. Reactive desorption and radiative association as possible drivers of complex molecule formation in the cold interstellar medium. ApJ. 769(1):34. 10.1088/0004-637X/769/1/34. Suche in Google Scholar

Vasyunin AI, Caselli P, Dulieu F, Jiménez-Serra I. 2017. Formation of complex molecules in prestellar cores: a multilayer approach. ApJ. 842(1):33. 10.3847/1538-4357/aa72ec. Suche in Google Scholar

Visser R, van Dishoeck EF, Black JH. 2009. The photodissociation and chemistry of CO isotopologues: applications to interstellar clouds and circumstellar disks. Astron Astrophys. 503(2):323–343. 10.1051/0004-6361/200912129. Suche in Google Scholar

Wakelam V, Herbst E. 2008. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in dense cloud chemistry. ApJ. 680(1):371. 10.1086/587734. Suche in Google Scholar

Walsh C, Millar TJ, Nomura H, Herbst E, Weaver SW, Aikawa Y, et al. 2014. Complex organic molecules in protoplanetary disks. Astron Astrophys. 563:A33. 10.1051/0004-6361/201322446. Suche in Google Scholar

Walsh C, Loomis RA, Öberg KI, Kama M, vanat Hoff MLR, Millar TJ, et al. 2016. First detection of gas-phase methanol in a protoplanetary disk. ApJ Lett. 823(1):L10. 10.3847/2041-8205/823/1/L10. Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Mikhail Yu. Kiskin et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Deep learning application for stellar parameters determination: I-constraining the hyperparameters

- Explaining the cuspy dark matter halos by the Landau–Ginzburg theory

- The evolution of time-dependent Λ and G in multi-fluid Bianchi type-I cosmological models

- Observational data and orbits of the comets discovered at the Vilnius Observatory in 1980–2006 and the case of the comet 322P

- Special Issue: Modern Stellar Astronomy

- Determination of the degree of star concentration in globular clusters based on space observation data

- Can local inhomogeneity of the Universe explain the accelerating expansion?

- Processing and visualisation of a series of monochromatic images of regions of the Sun

- 11-year dynamics of coronal hole and sunspot areas

- Investigation of the mechanism of a solar flare by means of MHD simulations above the active region in real scale of time: The choice of parameters and the appearance of a flare situation

- Comparing results of real-scale time MHD modeling with observational data for first flare M 1.9 in AR 10365

- Modeling of large-scale disk perturbation eclipses of UX Ori stars with the puffed-up inner disks

- A numerical approach to model chemistry of complex organic molecules in a protoplanetary disk

- Small-scale sectorial perturbation modes against the background of a pulsating model of disk-like self-gravitating systems

- Hα emission from gaseous structures above galactic discs

- Parameterization of long-period eclipsing binaries

- Chemical composition and ages of four globular clusters in M31 from the analysis of their integrated-light spectra

- Dynamics of magnetic flux tubes in accretion disks of Herbig Ae/Be stars

- Checking the possibility of determining the relative orbits of stars rotating around the center body of the Galaxy

- Photometry and kinematics of extragalactic star-forming complexes

- New triple-mode high-amplitude Delta Scuti variables

- Bubbles and OB associations

- Peculiarities of radio emission from new pulsars at 111 MHz

- Influence of the magnetic field on the formation of protostellar disks

- The specifics of pulsar radio emission

- Wide binary stars with non-coeval components

- Special Issue: The Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) 2021

- ANALOG-1 ISS – The first part of an analogue mission to guide ESA’s robotic moon exploration efforts

- Lunar PNT system concept and simulation results

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part I

- Message from the Guest Editor of the Special Issue on New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications

- Research on real-time reachability evaluation for reentry vehicles based on fuzzy learning

- Application of cloud computing key technology in aerospace TT&C

- Improvement of orbit prediction accuracy using extreme gradient boosting and principal component analysis

- End-of-discharge prediction for satellite lithium-ion battery based on evidential reasoning rule

- High-altitude satellites range scheduling for urgent request utilizing reinforcement learning

- Performance of dual one-way measurements and precise orbit determination for BDS via inter-satellite link

- Angular acceleration compensation guidance law for passive homing missiles

- Research progress on the effects of microgravity and space radiation on astronauts’ health and nursing measures

- A micro/nano joint satellite design of high maneuverability for space debris removal

- Optimization of satellite resource scheduling under regional target coverage conditions

- Research on fault detection and principal component analysis for spacecraft feature extraction based on kernel methods

- On-board BDS dynamic filtering ballistic determination and precision evaluation

- High-speed inter-satellite link construction technology for navigation constellation oriented to engineering practice

- Integrated design of ranging and DOR signal for China's deep space navigation

- Close-range leader–follower flight control technology for near-circular low-orbit satellites

- Analysis of the equilibrium points and orbits stability for the asteroid 93 Minerva

- Access once encountered TT&C mode based on space–air–ground integration network

- Cooperative capture trajectory optimization of multi-space robots using an improved multi-objective fruit fly algorithm