Abstract

Alginate–protein composite gels are widely used in food and biomedical applications, including 3D bioprinting, where, for example, alginate–gelatin bioinks serve as scaffolds for cultured meat and organ models. While gelatin offers unique thermo-responsive and elastic properties, its animal origin motivates the search for plant-based alternatives. Plant proteins like pea protein lack thermo-reversible gelation but provide cell adhesion motifs that support cell proliferation, making them promising components for bioink development. Therefore, this study aims to characterise the effect of varying pea protein contents (0–0.8 wt%) on alginate gelation behaviour in different solvents (0 mM, 100 mM NaCl, and DMEM cell culture medium). Alginate gelation was facilitated using a model mixing system with a two-component cartridge and static mixer, maintaining constant alginate (2 wt%) and calcium concentrations (∼30 mM). Rheological assessments revealed that pea protein decreased gel strength (G′) and delayed gelation, likely due to steric hindrance from protein entrapment during phase separation. However, protein addition improved water holding capacity and gel elasticity, indicated by a reduction in water loss, loss factor and dissipation ratio. Higher ionic strength mitigated the gelation delay by screening negative electrostatic repulsion. These findings provide insights for the formulation of plant-based bioinks with tailored techno-functional properties.

1 Introduction

Alginate–protein composite gels are used in various applications in foods or biomedicine. In 3D printing of foods, alginate-based inks have been shown to be suitable to create specific textures for personalised foods with improved nutritional profiles, plant-based meat alternatives or for the encapsulation of functional ingredients like antioxidants [1,2,3]. In 3D bioprinting, alginate–protein gels serve as scaffolds for cultured meat, tissue engineering and organ models [4,5,6]. A common bioink combination is the addition of gelatin to alginate, which improves the printability while providing cell adhesion motifs essential for cell growth and proliferation [7,8]. Replacing animal-derived gelatin with plant-based proteins such as pea protein is increasingly important for sustainability and animal welfare reasons.

Alginate is an anionic polysaccharide derived from algae or bacteria that forms strong but brittle gels in the presence of divalent cations [9]. Gelatin is a collagen-derived protein forming temperature-sensitive elastic gels [10]. In 3D bioprinting, the addition of gelatin to the alginate-based bioinks not only improves cell adhesion [11] but reduces the viscosity, resulting in improved printability and reduced shear stress on the cells during printing. Under cell culture conditions (approximately pH 7), alginate and gelatin are compatible in their ungelled state [12]. However, in biopolymer mixtures, gelation of one biopolymer can induce phase separation due to the excluded volume effect [13,14,15].

Pea protein offers a promising plant-based alternative due to its availability and ability to provide essential cell adhesion motifs that alginate lacks [16,17,18]. However, unlike gelatin, pea protein forms gels through heat-induced denaturation and aggregation [19]. Additionally, commercially available pea protein is often largely denatured due to intensive processing, leading to lower solubility and poor gelation properties [20]. While alginate and gelatin are compatible in their ungelled state and phase separation typically occurs upon gelation, alginate and pea protein behave differently under cell culture conditions (pH ∼7). Under these conditions, both alginate and pea protein carry negative charges [19], resulting in electrostatic repulsion and segregative phase separation even in the ungelled state [21]. This inherent incompatibility could be advantageous for increasing scaffold porosity but poses challenges for maintaining macroscale stability during printing, where homogeneity is required for high printing accuracy.

Phase separation in biopolymer mixtures can influence the gel strength in different ways [22,23]. It may enhance gel strength and accelerate the gelation by water redistribution and concentrating the polymers into distinct phases [24]. However, when the volume fractions are similar, the formation of a bicontinuous network can weaken the gel strength, as neither polymer network can be fully developed across the system [22,24]. When gelation and phase separation occur simultaneously, the outcome depends on the relative rates of these processes. If gelation is faster than phase separation, the system can reach an arrested state, in which macroscale homogeneity is maintained despite underlying microscopic phase separation [14,23,25].

A common method to prepare alginate-based bioinks involves blending the biopolymer mixture with a calcium sulphate solution containing the cells, using two syringes connected with a luer lock. The syringes are pushed back and forth to mix the two fluids [7,26,27]. As alginate rapidly gels upon contact with calcium [28], gelation and shear occur simultaneously during mixing, resulting in partial disruption of the network as it forms. Characterising the evolution of the gel structure immediately after mixing is essential to understand the early-stage properties of the bioink, which influence its printability [26]. This rapid gelation likely causes the system to reach an arrested state shortly after mixing, limiting large-scale phase separation. As a result, even mixtures such as alginate and pea protein, which are incompatible in their ungelled state, could form macroscopically homogeneous gels suitable for 3D bioprinting.

The solvent conditions, particularly ionic strength, can additionally affect the structure formation in alginate–protein bioinks. Higher concentrations of monovalent ions can reduce the repulsive interactions between biopolymers by screening their negative charges, potentially increasing their compatibility. Further, cell culture media which contain salts, glucose, amino acids and vitamins may influence the alginate gelation. However, little is known about how plant-based proteins like pea protein affect alginate gelation behaviour under conditions relevant to bioink preparation. A better understanding of the structure formation could help adjust the polymer content and solvent conditions for optimised techno-functional properties of the resulting composite gels.

Therefore, this study investigates the influences of varying pea protein content on the gelation behaviour of alginate in diverse solvent environments, including low ionic strength (distilled water, 0 mM NaCl), high ionic strength (100 mM NaCl) and cell culture medium DMEM (Dulbeccos Modified Eagle Medium). To better understand differences in gel microstructure, analyses were performed in the linear and non-linear viscoelastic regimes. The alginate gelation of pure alginate gels, as well as alginate–pea protein composite gels, was characterised using a model mixing system consisting of a two-component cartridge and an attached static mixer. This mixing system enables a rapid blending of the biopolymers and the calcium sulphate solution. Consequently, the alginate gelation starts during the mixing process, similar to the bioink preparation in bioprinting. In this context, we hypothesised the following:

The addition of pea protein results in antagonistic effects on gel strength. Due to the rapid gelation, phase separation cannot progress, leading to an arrested state where the protein is homogenously distributed throughout the alginate network. The repulsive interactions between alginate and pea protein disturb gel formation, leading to weaker gels.

The addition of pea protein slows alginate gelation. While the high viscosity of the ungelled biopolymer mixture helps to maintain macroscopic homogeneity, the evenly dispersed protein aggregates may sterically interfere with alginate–calcium crosslinking. Additionally, the protein may interact with the calcium ions, causing a buffering effect on the gelation.

A higher ionic strength could compensate for the effects of the protein by reducing the electrostatic repulsion between alginate molecules, as well as between alginate and pea protein. This charge screening could lead to faster gelation, despite the protein interfering with alginate gelation.

To test these hypotheses, we conducted oscillatory rheology measurements to characterise the potential antagonistic or synergistic effects on the gel strength, as well as gelation velocity. Additionally, we analysed non-linear rheological behaviour using Lissajous plots to gain more detailed information about the microstructure at a specific low large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS) strain amplitude, resembling the behaviour of the gels under cell culturing conditions and storage, where small movements of the gels, such as those caused by cell proliferation or cell culture medium exchange, impact the gel structure. Finally, we characterised the water loss of the gels.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

Sodium alginate (W201502, lot #SHBM2247) and biowest cell culture medium DMEM high glucose (L0101) w/o l-glutamine, w/o sodium pyruvate were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and VWR International GmbH (Dresden, Germany), respectively. The complete composition of the cell culture medium can be found in Table S1. Pea protein concentrate (ProFamTM Pea Protein 580, lot #E2028107A1) with a protein content of 78% and a solubility of approximately 30% was kindly provided by ADM Germany GmbH (Hamburg, Germany).

2.2 Alginate sample preparation

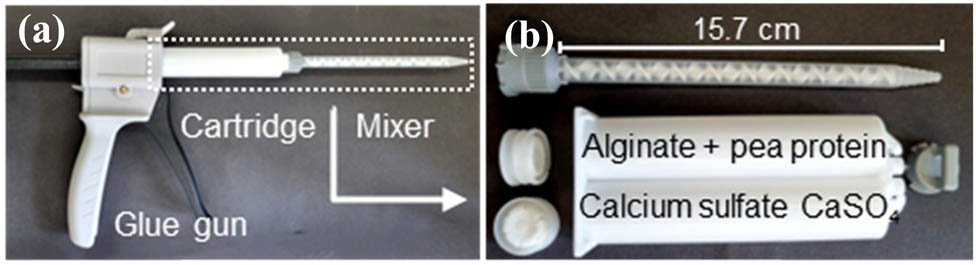

Alginate solutions with 4.0 wt% were prepared in distilled water, 200 mM NaCl or DMEM cell culture medium and stirred for 2 h at 60°C, followed by 4 h at 40°C. The solutions were stored in the fridge overnight, and the pH was adjusted to 7 the next day. The alginate gelation was conducted by rapid mixing of the alginate solution and 60 mM calcium sulphate (CaSO4) using a two-component cartridge (MIXPACTM 2 K 50 mL 1:1 B-system) with an attached static mixer (MBH-06-20T), commonly used for the preparation of two-component glue (Figure 1). Prior to the measurement, the cartridge was shaken for at least 30 s to ensure even distribution of the insoluble CaSO4 salt before mixing with alginate in a 1:1 weight ratio. The mixing is conducted by pushing the glue gun several times. To ensure reproducibility, the same number of pushes was used for each measurement. The first and last pushes were discarded, and the sample was directly applied to the rheometer plate. The resulting concentrations of the pure alginate gel were 2 wt% alginate and ∼30 mM CaSO4.

Mixing system for alginate gelation: (a) glue gun with attached two-component cartridge and static mixer and (b) disassembled two-component cartridge and static mixer.

2.3 Preparation of biopolymer mixtures

For the preparation of the composite gels, alginate stock solutions at 4.5 wt% were prepared as described before. Pea protein suspensions with 15 wt% were prepared in distilled water, stirred for 2 h and homogenised at 17,500 rpm for 90 s using Ultra-Turrax® (IKA-Werke, Germany). Afterwards, the pH was adjusted, and the protein suspension was autoclaved for 15 min at 121°C. This step was added since sterilisation of the protein is necessary for its use in bioinks for 3D bioprinting. After autoclaving, the protein suspension was thoroughly mixed by shaking, then cooled in an ice bath for 10 min and stored in the fridge overnight. DSC analysis of the untreated protein showed no detectable thermal transition (Figure S2), suggesting that the protein was largely denatured prior to autoclaving. Solubility was approximately 30%, which may be attributed to the presence of large aggregates, as indicated by high-molecular-weight bands and non-migrating material in SDS-PAGE. After autoclaving, the molecular weight distribution shifted to higher molecular weights with a broad band above 250 kDa, indicating further aggregation (Figure S3). Although no firm gel was visually apparent, autoclaving resulted in a noticeable increase in viscosity and the formation of a weak gel-like structure, as indicated by rheological measurements (G′ ∼10 Pa, G′ ∼4 Pa, Figure S4). The biopolymer mixtures were prepared by mixing the stock solutions. The resulting concentrations of the composite gels were 2 wt% alginate + 0.1, 0.4 or 0.8 wt% pea protein and ∼30 mM CaSO4. At these low protein contents, the autoclaved protein is expected to be present as dispersed aggregates rather than forming a continuous protein network. The alginate content was selected based on the typical range used in 3D bioprinting. A concentration of 2 wt% alginate combined with 30 mM CaSO4 was identified as suitable for bioinks in previous studies [11]. Additionally, our pretrial experiments confirmed that these concentrations facilitated the most homogeneous mixing when using the static mixer system. Higher alginate and/or calcium concentrations adversely affected mixing efficiency and resulted in inhomogeneous samples. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.4 Small and large-amplitude oscillatory rheology

Rheological measurements were carried out using an MCR 102e rheometer (Anton Paar GmbH, Austria) equipped with a plate-plate geometry (PP50 with 50 mm diameter, Anton Paar GmbH, Austria). Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were conducted at 21°C, with a strain amplitude of 0.5% and a frequency of 1 Hz. Initially, a time sweep was performed for 30 min, corresponding to the typical duration required for preparing the bioink and initiating the 3D bioprinting process. Subsequently, a frequency sweep from 0.01 to 100 Hz was conducted (Figures S7 and S8), followed by an amplitude sweep ranging from 0.01 to 100%. The gelation velocity within the 30 min time sweep was calculated as the first derivative of G′ as a function of time (dG′/dt). To ensure the comparability of the samples, the gelation velocity was normalised against the maximum value

To further analyse the non-linear deformation behaviour beyond the linear viscoelastic (LVE) region (LAOS), elastic and viscous Lissajous plots were generated. In an elastic Lissajous plot (stress

where

Here,

Here,

2.5 Water loss

The water loss of the gels was characterised by weighing them before and after centrifugation at 20,000 g and 21°C for 30 min (Avanti J-E, Beckmann Coulter GmbH, Germany). Prior to centrifugation, the gels (approximately 20 g) were placed in 50 mL centrifuge tubes and stored at room temperature for 1 h. The water lost, collected as the supernatant, was carefully extracted using a pipette. The total water loss was calculated as follows:

2.6 Zeta potential measurements

Zeta potential measurements of pure alginate and pea protein in distilled water and in 100 mM NaCl were conducted using a ZetaSizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd, UK) at 21°C and a polymer concentration of 0.1 wt%. Prior to the measurement, the samples were filtered with glass fibre syringe filters with a pore size of 1–2 µm (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The samples were then equilibrated for 4 min, and the measurement duration was restricted to 40 runs.

3 Results and discussion

To better understand the gelation behaviour of alginate–pea protein systems under conditions relevant to bioink preparation, we used a model mixing system consisting of a two-component cartridge and a static mixer. This setup mimics the mixing conditions of extrusion-based 3D bioprinting while enabling rheological analysis during the early stages of alginate gelation. First, we analysed the mechanical properties of the resulting gels, focusing on gel strength and water retention. Second, we assessed gelation kinetics by tracking the time-dependent evolution of the storage modulus. Finally, we examined the microstructural characteristics of the gels under non-linear deformation using LAOS analysis.

3.1 Gel strength

The gelation behaviour of the alginate–pea protein composite gels was first characterised by time sweep measurements, which are provided in the Figure S5. All samples exhibited typical gelation curves, with both storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) increasing rapidly in the initial phase before reaching a plateau-like region. Notably, all samples had already reached a gel state (G′ > G″) at the beginning of the measurement, consistent with the rapid gelation induced by calcium addition. Since the gelation profiles of the samples were similar, three parameters were chosen to better quantify differences in gel strength: The storage modulus G′ (Figure 2a) and the loss factor tan δ (Figure 2b) at the end of the 30 min time sweep, as well as the total water loss of the gels after centrifugation (Figure 2c). First, a higher storage modulus indicates a higher ability of the gel to store and recover energy and therefore it is often used to describe the gel strength [30]. Second, the loss factor is a useful parameter to analyse the gel strength since it represents the ratio of energy lost (loss modulus G″) to energy stored (storage modulus G′) during deformation tan δ = G″/G′ [30]. Consequently, low values of the loss factor (tan δ < 1) indicate a higher proportion of energy stored, which correlates with higher elasticity and therefore higher resistance against deformation, indicating a stronger gel. Third, the water loss after centrifugation is indirectly related to the gel strength as a low water loss indicates a high capacity of the gel network to withstand the deformation by centrifugation and retain the water immobilised within the gel network. Figure 2 shows the gel strength of alginate–pea protein composite gels indicated by the chosen parameters as a function of the added protein content in various solvents.

Gel strength represented by: (a) storage modulus G′ and (b) loss factor tan δ measured after 30 min time sweep at 0.5% deformation and 1 Hz. (c) Total water loss (%) after centrifugation of 2 wt% alginate gels as a function of added protein content in various solvents. Lines are added as guides to the eye.

The addition of protein resulted in a strong decrease of G′, indicating weaker gels (Figure 2a). Lower values in G′ indicate an antagonistic effect on the overall gel strength, which confirms the first hypothesis. In biopolymer mixtures such as alginate and pea protein, phase separation is thermodynamically driven by repulsive electrostatic interactions, as both biopolymers carry negative charges under the conditions used (zeta potential, Figure 3). However, phase separation is likely limited by the high viscosity of the biopolymer mixture prior to gelation and by the rapid formation of the alginate network upon mixing with calcium sulphate. The resulting increase in viscosity and the formation of a crosslinked network likely reduced molecular mobility, leading the system into an arrested state where phase separation is kinetically hindered. Consequently, while electrostatic incompatibility exists, the rapid gelation of alginate restricts the extent to which phase separation can develop. It should be noted that the pea protein stock solution (15 wt%) exhibited weak gel-like behaviour (G′ ∼10 Pa, G′ ∼4 Pa, at 0.5% deformation and 1 Hz, Figure S4), likely due to aggregation and weak network formation induced by the autoclaving treatment. However, this stock solution was subsequently diluted when mixed with alginate and calcium sulphate, resulting in a maximum final protein concentration of 0.8 wt%. At this low concentration, it is highly unlikely that the protein retains or forms an independent gel network. Instead, the dilution and shear during mixing are expected to disrupt any weak protein aggregates, resulting in dispersed particles within the continuous alginate matrix. These protein aggregates may interfere with alginate gelation and reduce gel strength through steric effects rather than by forming an independent protein network. The resulting gel could either exhibit partial phase separation, with the protein aggregates dispersed within the continuous alginate network or form a swollen gel where the protein is more evenly distributed but may still interfere with gelation through steric hindrance. However, based on rheological data alone, no definitive conclusion can be drawn regarding the microstructure.

Zeta potential of alginate and pea protein at pH 7 in distilled water (0 mM NaCl) and in 100 mM NaCl. Measurements were performed as duplicates. Error bars account for the standard error within one measurement.

At the same time, the loss factor of the gels decreased (Figure 2b), indicating a more pronounced elastic behaviour with increasing protein content. This behaviour is contradictory to the decrease of the storage modulus (indicating weaker gels) since lower values of the loss factor are attributed to more elastic and therefore stronger gels. A simultaneous decrease of the storage modulus and the loss factor indicates that the relative contribution of the viscous component (loss modulus G″) is decreasing even more than the elastic component (storage modulus). The changes in gel elasticity with protein addition will be further discussed in Section 3.3, using dissipation ratio data. Moreover, the total water loss of the gels decreased with increasing protein content (Figure 2c), which could be attributed to the higher total polymer content of the gels. Water loss, especially endogenous water loss due to syneresis occurring without external force, is more pronounced in gels with high permeability, since polymer chain rearrangements tend to lead to water redistribution [32]. The increased total polymer content in alginate–pea protein gels could, therefore, reduce the mobility of the molecules, leading to a lower total water loss. However, it cannot be excluded that changes in the gel structure, as indicated by the lower G′ or a lower loss factor, also influence the water loss of the gels.

Leelapunnawut et al. analysed alginate–pea protein gels for 3D printing with a similar composition used in this study. However, they employed a different gelation method, incorporating phosphate to slow down the alginate gelation. Compared to our results, they observed higher values of G′ and the loss factor, indicating a stronger yet less elastic gel [33]. The slower alginate gelation in the presence of phosphate may allow the phase separation rate to exceed the gelation rate, potentially leading to more distinct phase separation before reaching an arrested state.

Interestingly, other authors reported synergistic effects of heat-treated pea protein on calcium-induced gelation in alginate–pea protein gels [34,35]. However, these studies used low-denatured pea protein produced at lab scale, which formed soluble aggregates. Compared to the commercial protein used in this study, the gelation properties of these soluble aggregates should be improved [20], resulting in the pea protein contributing to the gel strength. Furthermore, these studies used slower gelation approaches through the addition of phosphate [35] or slowly releasing calcium from insoluble salts by a gradual pH decrease with d-glucono-δ-lactone [34]. In this context, the slower alginate gelation rate enables the formation of different network types depending on the extent of phase separation at the given composition of the gels.

Moreover, to create a model system that resembles the 3D bioprinting process, we chose a gelation time of 30 min, as this is a typical duration for the bioprinting process. However, within these 30 min, most samples had not reached a steady state of gelation. Notably, samples containing protein exhibited a slower gelation, which will be discussed in the next section. This slower gelation implies that the G′ values shown in Figure 2a may not represent the maximum gel strength that these slower-gelling samples would achieve at the steady state. Nevertheless, extending the gelation time is not feasible for 3D bioprinting processes, as prolonged exposure could damage the cells [36].

A higher ionic strength of 100 mM NaCl did not affect G′ (Figure 2a). In contrast, the loss factor (Figure 2b) and the total water loss (Figure 2c) increased with the higher ionic strength, which could be caused by the competition between the biopolymer molecules and salt ions for water. The higher affinity of the salt ions to water reduces the water bound by the biopolymer network, decreasing the water holding capacity and increasing viscous behaviour (higher loss factor). Previous studies have described the effect of higher ionic strength on alginate gel layers and found that increasing ionic strength leads to an increased layer thickness, i.e. swelling of the gel. On the one hand, the reduction of electrostatic repulsions leads to the formation of intramolecular bonds, which reduce the stretching length of the molecules, leading to less elastic gels [37]. On the other hand, an ion exchange between calcium and sodium ions could lead to a reduction in the gel strength [38]. The addition of DMEM led to a slight decrease in G′ while the loss factor remained unchanged. The lower G′ could be attributed to components in the cell culture media that might interfere with the alginate gelation, especially charged molecules like amino acids and salt ions [39,40]. The total water loss of the gels was higher than in water but lower than in 100 mM NaCl gels.

Another factor influencing the resulting gel strength is the shear stress applied to the gels during the mixing process. As previously described, the alginate gelation occurs immediately upon contact with calcium sulphate, meaning the gel is formed during the residence time in the static mixer. Consequently, the applied stress during mixing partially breaks the gel structure, which subsequently recovers due to further diffusion of the calcium ions after mixing. The efficiency of the mixing process is influenced by viscosity. The addition of pea protein to the alginate solution had only a minor effect on the viscosity of the ungelled mixtures (data not shown). However, depending on the rate and extent of gelation, the shear stress during mixing likely varies between samples, potentially influencing the resulting gel strength. The impact of different mixing systems and mixing durations on the viscosity and gelation of alginate–pea protein gels for bioinks will be explored in future studies and is beyond the scope of the present work.

3.2 Gelation velocity

Figure 4a shows the normalised gelation velocity dG′/dt as a function of time for pure alginate gels and alginate–pea protein gels containing 0.8 wt% pea protein. The progression of alginate gelation typically exhibits a rapid increase in G′, followed by a plateau where G′ remains relatively stable until reaching a steady state, during which a further increase of the modulus is neglectable. The initial increase of G′ results in a maximum of the gelation velocity (dG′/dt). As the gelation continues towards the steady state, dG′/dt approaches zero [13,41]. The stages of alginate gelation have been extensively described in the literature. Fang et al. characterised alginate gelation as occurring in three sequential steps. The first step involves the formation of alginate–calcium mono-complexes. In the second step, dimers are formed in an egg-box-like structure, where two alginate molecules are crosslinked by a single calcium ion. The third step involves the lateral association of these dimers to form multimers [42]. Besiri et al., who studied in situ alginate gelation using a custom-made rheological setup, were able to measure and identify two distinct stages. The first stage is characterised by a rapid increase in G′ (high dG′/dt), corresponding to the initial fast crosslinking within the first 30 s. The second stage shows a slower increase in G′ (lower dG′/dt), starting around 13 min, which reflects a reduction in the diffusion rate caused by the increase in viscosity and slower formation of multimers [43]. However, in this study, the rapid gelation method involving direct mixing of alginate with calcium sulphate is carried out outside of the rheometer. Therefore, the first stage of gelation, which occurs within the first few seconds and involves the reaching of the maximum gelation velocity, happens before rheological measurements can begin. As a result, measurements start during the second stage of gelation, as described by Besiri et al. [43], when the sample has already reached the gel state (G′ > G″). This approach captures only the latter part of the gelation velocity curve. This latter stage is characterised by a slow decrease in gelation velocity due to the further formation of multimers and completion of the network, which reduces the diffusion rate of calcium ions.

Normalised gelation velocity dG′/dt during time sweep at 0.5% deformation and 1 Hz: (a) alginate 2 wt% + pea protein 0–0.8 wt% in various solvents, (b) gelation velocity at 10 min of the time sweep as a function of the added protein content in various solvents. In (b), the lines are added as guides to the eye. Arrows (Δ) indicate the deceleration of gelation velocity from pure alginate to alginate–pea protein gels.

The faster the gelation progresses, the more rapidly the viscosity increases, inhibiting further diffusion. This causes G′ to reach its plateau and dG′/dt to approach zero more quickly.

At 100 mM NaCl, alginate gelation was slightly accelerated compared to 0 mM NaCl (blue solid curve compared to black solid curve in Figure 4a), likely due to electrostatic screening of the negative charges of alginate by sodium ions. With the addition of NaCl, the zeta potential increased from −65 ± 10 to −27 ± 2 mV for alginate and −30 ± 1 to −12 ± 1 mV for pea protein (Figure 3). The reduced repulsion between alginate molecules leads to a faster network formation, as previously hypothesised. In the cell culture medium DMEM (red solid curve in Figure 4a), alginate gelation was slightly slower compared to the gelation in water (black solid curve). This could be attributed to two effects: First, attractive electrostatic interactions between the medium’s components, such as positively charged amino acids, and alginate may occupy calcium binding sites. Second, components of the medium may have an affinity for calcium, causing calcium ions to bind to these components instead of alginate. Both scenarios result in a buffering effect on the formation of alginate–calcium bonds, thus hindering gelation. Although zeta potential measurements in DMEM were technically challenging and are not discussed in detail here, both alginate and pea protein can be assumed to remain negatively charged in DMEM, as the medium’s ionic strength (∼150 mM) falls within the same range as the 100–200 mM NaCl conditions where negative surface charges were confirmed. This assumption is further supported by previous findings showing that alginate maintains a negative zeta potential even at ionic strengths of 200 mM NaCl [12]. The zeta potential values in DMEM and a discussion of the difficulties in measurement are included in Figure S1.

The addition of protein led to a slower gelation in all solvents (dashed curves in Figure 4a). As discussed in Section 3.1, the low pea protein contents used in this study are unlikely to form an independent protein network. Instead, the protein is expected to be present as dispersed aggregates within the alginate matrix. One possible explanation for the reduced gelation velocity is that these protein aggregates sterically hinder the mobility of alginate chains, slowing the formation of the crosslinked network. Additionally, the protein may interact with free calcium ions, temporarily reducing their availability for alginate crosslinking, causing a similar buffering mechanism as described for DMEM. In alginate–gelatin mixtures, such buffering effects have been demonstrated when using slow calcium release from Ca–EDTA complexes via a d-glucono-δ-lactone induced pH decrease. In this study, the slower gelation was attributed to gelatin either interacting attractively with the alginate or, more likely, buffering the pH and therefore the calcium release from Ca–EDTA complexes [13]. Moreover, previous studies have shown that attractive interactions between negatively charged polysaccharides and positive residual charges of overall negatively charged proteins can occur [12,44,45]. However, this effect may be minor due to the relatively high negative charges of alginate −65 ± 10 mV and pea protein −30 ± 1 mV at pH 7 (Figure 3). While increased viscosity of the biopolymer mixture could theoretically contribute to slower gelation, viscosity measurements of the stock solutions before gelation showed comparable values across all formulations, particularly at higher shear rates relevant for mixing (data not shown). This observation is further supported by recent findings in a separate study (Woelken et al., manuscript in preparation), where even at higher total polymer contents, the addition of pea protein to alginate solutions had only a minor effect on viscosity under shear. This suggests that viscosity differences are unlikely to explain the reduced gelation velocity. Nevertheless, the rheological measurements alone cannot fully resolve the underlying mechanism, and a potential contribution of residual protein aggregation cannot be fully excluded.

To further quantify and visualise the differences in gelation velocity arising from protein addition, Figure 4b shows dG′/dt at a selected time of 10 min as a function of the added protein content. The trends shown at 10 min (Figure 4b) are similar for later time points during the experiment. Additional figures showing the differences between pure alginate gels and alginate–pea protein gels as ΔdG′/dt over time can be found in Figure S6. At the highest pea protein content (0.8 wt%), the difference between the pure alginate gel and the pea protein gel expressed as ΔdG′/dt was 0.42, 0.23 and 0.35 in 0 mM, 100 mM NaCl and DMEM, respectively. In Figure 4b these differences in ΔdG′/dt are visualised by the arrows. The effect of protein addition on the gelation velocity was less pronounced in 100 mM NaCl compared to water as can be seen from the lower ΔdG′/dt. This suggests that the accelerated gelation due to charge screening by NaCl and the decelerated gelation due to the steric hindrances caused by the protein may counterbalance each other, as previously hypothesised. Conversely, this counterbalancing effect was not observed in DMEM despite its high ionic strength. This observation could be attributed to the presence of additional components, such as amino acids, which might exert a similar effect as the pea protein. Consequently, the combined decelerating effect of the protein and the constituents of the DMEM either cannot be counterbalanced at all or would require higher salt concentrations.

3.3 Small and large-amplitude oscillatory shear rheology

In the final part of this study, we analysed the deformation behaviour of the gels within and beyond the LVE regime. Understanding the behaviour of the gels under low and high deformation is essential to gain a detailed understanding of the microstructure and the impact of the pea protein on the alginate gelation. We will focus our discussion mainly on non-linearities at low strain amplitudes as these provide additional insights under conditions relevant to cell culturing and storage. Figure 5 illustrates the results of the amplitude sweep, with the storage and loss moduli in Figure 5a, the quantification on the non-linearities using the S- and T-factor in Figure 5b and c, respectively, as well as the dissipation ratio in Figure 5d. All parameters are depicted as functions of the applied deformation strain.

Amplitude sweeps (0.1–100%) of pure alginate gels 2 wt% and alginate–pea protein gels 2 wt% + 0.8 wt% in various solvents at 1 Hz: (a) Storage and loss moduli, (b) intracycle strain stiffening coefficient (S-factor), (c) intracycle shear thickening coefficient (T-factor), and (d) dissipation ratio as functions of deformation. The dashed line indicates the measurement limit at 21.1% deformation. The dotted line indicates the deformation (15.4%) used for the quantification of the data.

The amplitude sweeps in Figure 5a illustrate the intercycle strain behaviour over the entire strain range applied. As described previously, the moduli of alginate–pea protein gels are lower than those of pure alginate gels. Additionally, the shape of the curves differs: Pure alginate shows more gradual softening beginning at lower strain levels, whereas alginate–pea protein gels exhibit a sharper decrease in G′ at higher strains. This difference becomes especially apparent at 100 mM NaCl. Moreover, only the gels containing pea protein show a distinct maximum in G″, which is characteristic of the brittle breaking behaviour often observed in alginate gels [13]. Both the abrupt decrease in G′ and the peak in G″ are associated with the onset of non-linear deformation. Above 21% deformation, all gels showed a significant increase in higher-order Fourier coefficients, revealing the emergence of intracycle non-linearities (Figure S9b). In particular, the second Fourier coefficient also began to increase slightly. According to the literature, only odd harmonics should be present, and even harmonics might indicate measurement irregularities such as wall-slip or transient flows [29]. Since some of the gels exhibited syneresis during the measurement, wall slippage likely caused these irregularities. This could explain why the maximum in G″ is absent in the pure alginate gels. Due to the increase in higher-order and especially even harmonics, we focus on the data up to a deformation of 21%, as indicated by the dashed lines in Figure 5. Data above 21% deformation is only mentioned in qualitative terms.

Within the LVE regime, the elastic Lissajous plots exhibited narrow elliptical shapes for all samples, while the viscous Lissajous plots displayed wide, nearly circular shapes, indicating viscoelastic behaviour with a significant elastic contribution. Beyond the LVE regime, the Lissajous plots became distorted. These non-linearities were quantified by the S- and T-factor, as shown in Figure 5b and c, respectively. Within the LVE regime, the S- and T-factor both had values of zero (Figure 5b and c). However, at deformations above 3%, the Lissajous plots became distorted and both factors increased above zero, indicating intracycle strain stiffening for the S-factor and intracycle shear thickening behaviour for the T-factor. Using the S-factor, no differences were observed between pure alginate and alginate–pea protein gels. In contrast, distinct differences in the T-factor trend were observed with protein addition. In pure alginate gels, the increase of the T-factor started at a lower deformation, indicating non-linear behaviour, possibly due to earlier yielding compared to alginate–pea protein gels. At deformations below 20%, the T-factor exhibited higher absolute values than the S-factor, indicating that the sample’s behaviour is dominated by intracycle shear thickening [46]. At around 20% deformation, a maximum in the T-factor was observed, which can either be attributed to the formation of microcracks in the sample, or as mentioned before wall-slip. At deformations exceeding 50%, the T-factor dropped drastically in all samples. In pure alginate gels, values below zero were reached, indicating the presence of intracycle shear thinning. In contrast, the S-factor increased further and showed higher absolute values than the T-factor, especially for the alginate–pea protein mixture, suggesting that intracycle strain stiffening becomes the dominant behaviour of the samples at high deformations [46]. This relatively contradictory behaviour of the S- and T-factor could also be attributed to inertia effects [46] like secondary flows arising at high deformations [47]. Additionally, the maximum in the T-factor correlates with the maximum of the third Fourier coefficient (Figures S9b and d and S10), suggesting that the measuring accuracy above this deformation (∼21%) might be negatively impacted, most likely by wall-slip phenomena, as previously described.

The dissipation ratio ϕ (equation (3)) shown in Figure 5d quantifies the area enclosed in the elastic Lissajous plots. Values close to zero indicate elastic behaviour, while values of ∼1 indicate plastic behaviour [31]. Within the LVE regime, the narrow elliptical shape of the Lissajous plots results in dissipation ratios close to zero in all samples, indicating highly elastic gels. Up to the chosen deformation limit of 21%, the dissipation ratio shows only a slight increase with rising deformation. Above 21%, the dissipation ratio showed a steep increase, revealing the change from elastic to plastic behaviour when the sample undergoes partial structural breakdown and transitions into a flowing state. This is in agreement with the other parameters discussed.

In contrast to the analysis of the gel strength, the differences in non-linear behaviour between the solvents are not clearly visible in Figure 5. To better quantify the differences, we selected an amplitude of 15.4% to compare the elastic and viscous Lissajous plots (Figure 6a), the S- and T-factor (Figure 6b), as well as the dissipation ratio (Figure 6c) for pure alginate gels and alginate–pea protein gels with 0.8 wt% pea protein. The chosen amplitude is well above the LVE regime, but below the deformation where the higher-order Fourier coefficients might indicate impaired measurement accuracy. Furthermore, the behaviour of the gels under relatively low strain deformation is particularly relevant for evaluating their performance under cell culturing conditions. Small movements of the gels, such as those caused by cell proliferation or during the exchange of cell culture medium, could impact the scaffolds.

LAOS analysis at 15.4% deformation (non-linear region) and 1 Hz: (a) normalised elastic and viscous Lissajous plots, (b) S- and T-factor, and (c) dissipation ratios for pure alginate gels 2 wt% and alginate–pea protein gels 2 wt% + 0.8 wt% in various solvents.

From Figure 6a, it is evident that the protein addition impacted the viscoelastic deformation behaviour of the gels. The shape of the elastic Lissajous plots changes slightly: the curves become narrower for alginate–pea protein gels than for pure alginate, suggesting a modest increase in elastic stiffness. In the viscous Lissajous plots, the changes are more pronounced, shifting from a more rectangular shape in pure alginate gels to a rounder shape in protein-containing gels. This suggests a change in the nature of the viscous response – from nonlinear in pure alginate to more linear and homogeneous when pea protein is present. Similarly, Figure 6b shows that the differences in the S-factor among all samples are relatively small compared to the differences in the T-factors. In most of the gels, the T-factor is higher than the S-factor, indicating that the shear thickening response of the sample dominates [46]. With the addition of pea protein, both factors decrease, resulting in similar values of S- and T-factor in composite gels at 0 mM and in DMEM. These samples also had the lowest loss factors, showing a reduced viscous behaviour, which might explain why the T-factor, describing the viscous contribution to the viscoelastic behaviour of the gel, is not dominant in those samples.

Although the elastic Lissajous plots displayed similar elliptical shapes across all samples, differences in the enclosed area of the elastic Lissajous plots were evident. Figure 6c highlights these variations in the dissipation ratio between the solvents. The pure alginate gels in 100 mM NaCl had a higher dissipation ratio, indicating less elastic and more plastic behaviour. Conversely, the addition of pea protein led to lower dissipation ratios in all solvents, implying that these gels have a higher elasticity. These results are consistent with the discussion of the loss factor (in Section 3.1). Interestingly, the reduction in dissipation ratio and loss factor correlates with the water loss of the gels (Figures 2b and c and 6c), since greater water loss was associated with a higher dissipation ratio, and vice versa. This relationship was previously described for soy protein gels by Urbonaite et al., who further correlated the water holding capacity and dissipated energy to the coarseness of the gels. Coarser gels exhibited a higher water loss and greater energy dissipation. Therefore, it seems likely that the addition of protein, while increasing the elasticity of the gels, may also reduce their coarseness by acting as an inert filler within the alginate network [48]. Further, the gelation velocity might impact the elasticity of the gels. Kastner et al. showed that the elasticity of pectin gels increased with a slower cooling rate/slower gelation. The slow gelation allows an optimum arrangement of the molecules, leading to longer junction zones. Conversely, a fast gelation leads to the formation of shorter junctions and less arrangement of the molecules, resulting in a lower elasticity [49]. These explanations are in line with the results of this work.

Usually, a higher elasticity presents itself as a higher resistance against deformation, which leads to a larger LVE region and a crossover point (G′ = G″) at higher amplitudes. Because the crossover in the analysed gels occurs way above the amplitude where wall-slippage and measurement inaccuracies are likely (Figure 6a), this parameter led to non-reproducible results (data not shown). Furthermore, the limit of the LVE is usually defined as the amplitude at which G′ deviates more than 3–5% from

As illustrated in Figure 5c, the T-factor in particular shows an increase to values above zero at higher deformation in alginate–pea protein gels compared to pure alginate gels. Figure 7 depicts the linearity limit, i.e. start of non-linear behaviour, as the amplitude at which the S-factor and T-factor rise to values above 0.03 (3% deviation from zero).

LAOS analysis: Linearity limit, i.e. beginning of non-linear behaviour, indicated as strain amplitude at 3% deviation of S- and T-factor from zero.

As described previously, the T-factor predominated in most samples, leading to its values increasing at lower deformation compared to the S-factor. Nonetheless, a similar trend is observed for both the S- and T-factor: the addition of protein caused deviations from zero occurring at higher deformations. This behaviour can be attributed to a higher linearity limit of the alginate-pea protein gels and is consistent with the results discussed earlier. A similar trend can be seen in the FT rheology. In samples containing protein, higher order harmonics (third harmonic in particular) occur at higher deformations, further indicating an increased linearity limit (Figure S11).

To conclude, the addition of pea protein negatively affected the alginate gelation, as evident by the lower G′ and the slower gelation velocity. Phase separation in incompatible biopolymer mixtures often leads to synergistic effects on the gel strength by concentrating the biopolymers in their respective phases [23]. However, in the case of alginate–pea protein systems, where alginate is rapidly gelled by the addition of calcium sulphate, antagonistic effects were observed. These effects can likely be attributed to the gelation rate surpassing the phase separation rate, forcing the system into an arrested state where the protein is evenly distributed throughout the alginate network [23,50]. Since both biopolymers are negatively charged, repulsive interactions and steric hindrances interfere with the alginate gelation. This effect could be partially mitigated by adding NaCl, which accelerated the alginate gelation through charge screening. In the cell culture medium DMEM, similar buffering effects on the gelation velocity as seen for the protein addition were observed, indicating that the slower gelation could also be due to attractive interactions between calcium ions and amino acids in DMEM or with the pea protein. However, the effect of DMEM was small compared to the addition of protein. Despite the antagonistic effects on the storage modulus, the protein addition led to a lower water loss and more elastic gels, as indicated by the lower loss factor and lower dissipation ratio.

4 Conclusion

This study analysed the effect of the pea protein addition on the alginate gelation in various solvents. It was demonstrated that pea protein delays the alginate gelation and exerts antagonistic effects on the gel strength. Similar effects could be seen for the alginate gelation in DMEM cell culture medium. Conversely, in a 100 mM NaCl solvent, the effects of pea protein were counterbalanced, as the electrostatic screening of repulsive forces accelerated gelation. Although the alginate–pea protein systems formed overall weaker gels, the elasticity of the composite gels increased in all solvents.

With slower alginate gelation, the bioink mixing process – where the biopolymer solution is directly combined with calcium sulphate – could be facilitated with less shear stress on the cells, as the mixture’s viscosity would increase more gradually. Furthermore, the higher elasticity of the gels could enhance the stability of the construct during cell incubation. However, higher alginate contents may be necessary to counteract the antagonistic effects of pea protein on the gel strength.

This study contributes to a better understanding of the impact of pea protein addition on the alginate gelation behaviour. A detailed grasp of this structure–process–function relationship is crucial for substituting gelatin with more sustainable plant-based proteins and developing plant-based bioinks in 3D bioprinting. To deepen this understanding, direct microstructural imaging, such as confocal microscopy, would be valuable to clarify the gel structure and extent of phase separation in these composite gels. Building on these insights, future studies should focus on implementing these findings in 3D bioprinting applications. Besides printability, two additional parameters are of great interest. As previously described, the alginate gelation is influenced by the mixing of the biopolymer solution with the calcium sulphate. In this study, we employed a model mixing system consisting of a two-component cartridge and a static mixer. Although the relatively long static mixer ensures macroscopically homogeneous mixing, it would require a large number of cells, which would not only significantly increase costs but also subject the cells to excessive shear stress. Therefore, analysing different mixing strategies could provide insights into how the formulation and mixing influence the printability and cell viability. Cell viability is also affected by the porosity and permeability of the gels. Alginate–pea protein gels could differ significantly from alginate–gelatin gels, as the pea protein does not dissolve during the cell cultivation at 37°C. Thus, cell viability studies are needed to determine whether pea protein is a suitable substitute for gelatin in 3D bioprinting. These aspects extend from the present work and will be explored in future studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank the Department of Food Technology and Food Material Science, led by Prof. Stephan Drusch at the Technical University of Berlin, for generously providing laboratory space and engaging in valuable scientific discussions.

-

Funding information: This IGF project (01IF22232N) of the FEI is supported within the programme for promoting the Industrial Collective Research (IGF) of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWE) on the basis of a decision by the German Bundestag.

-

Author contributions: Sabrina Bäther: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualisation. Lisa Wölken: Writing – Review & Editing. Kerstin Risse: Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. Christoph Simon Hundschell: Writing – Review & Editing. Anja Maria Wagemans: Conceptualisation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval statement: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Dankar I, Haddarah A, Omar FE, Sepulcre F, Pujolà M. 3D printing technology: The new era for food customization and elaboration. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;75:231–42.10.1016/j.tifs.2018.03.018Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zhu S, Wang W, Stieger M, van der Goot AJ, Schutyser MA. Shear-induced structuring of phase-separated sodium caseinate - sodium alginate blends using extrusion-based 3D printing: Creation of anisotropic aligned micron-size fibrous structures and macroscale filament bundles. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2022;81:103146.10.1016/j.ifset.2022.103146Search in Google Scholar

[3] Mallakpour S, Azadi E, Hussain CM. State-of-the-art of 3D printing technology of alginate-based hydrogels-An emerging technique for industrial applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;293:102436. PubMed PMID: 34023568.10.1016/j.cis.2021.102436Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Cui H, Nowicki M, Fisher JP, Zhang LG. 3D bioprinting for organ regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6(1):1601118.10.1002/adhm.201601118Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Duan B, Hockaday LA, Kang KH, Butcher JT. 3D bioprinting of heterogeneous aortic valve conduits with alginate/gelatin hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101(5):1255–64. PubMed PMID: 23015540; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3694360.10.1002/jbm.a.34420Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Varaprasad K, Karthikeyan C, Yallapu MM, Sadiku R. The significance of biomacromolecule alginate for the 3D printing of hydrogels for biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;212:561–78. PubMed PMID: 35643157.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.05.157Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Hiller T, Berg J, Elomaa L, Röhrs V, Ullah I, Schaar K, et al. Generation of a 3D liver model comprising human extracellular matrix in an alginate/gelatin-based bioink by extrusion bioprinting for infection and transduction studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3129.10.3390/ijms19103129Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Axpe E, Oyen ML. Applications of alginate-based bioinks in 3D bioprinting. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12):1976. PubMed PMID: 27898010; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5187776 .10.3390/ijms17121976Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Draget KI. Alginates. In: Phillips GO, Williams PA, editors. Handbook of hydrocolloids. 2nd edn. Boca Raton: CRC Press; Woodhead Publishing; 2009. p. 807–28.10.1533/9781845695873.807Search in Google Scholar

[10] Haug IJ, Draget KI. Gelatin. In: Phillips GO, Williams PA, editors. Handbook of hydrocolloids. 2nd edn. Boca Raton: CRC Press; Woodhead Publishing; 2009. p. 142–63.10.1533/9781845695873.142Search in Google Scholar

[11] Berg J, Hiller T, Kissner MS, Qazi TH, Duda GN, Hocke AC, et al. Optimization of cell-laden bioinks for 3D bioprinting and efficient infection with influenza A virus. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13877.10.1038/s41598-018-31880-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Bäther S, Hundschell CS, Kieserling H, Wagemans AM. Impact of the solvent properties on molecular interactions and phase behaviour of alginate-gelatin systems. Colloids Surf A Eng. 2023;656:130455.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.130455Search in Google Scholar

[13] Bäther S, Seibt JH, Hundschell CS, Bonilla JC, Clausen MP, Wagemans AM. Phase behaviour and structure formation of alginate-gelatin composite gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;149:109538.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109538Search in Google Scholar

[14] Panouillé M, Larreta-Garde V. Gelation behaviour of gelatin and alginate mixtures. Food Hydrocoll. 2009;23(4):1074–80.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2008.06.011Search in Google Scholar

[15] Nooeaid P, Chuysinuan P, Techasakul S. Alginate/gelatine hydrogels: Characterisation and application of antioxidant release. Green Mater. 2017;5(4):153–64.10.1680/jgrma.16.00020Search in Google Scholar

[16] Kim DH, Han SG, Lim SJ, Hong SJ, Kwon HC, Jung HS. Comparison of soy and pea protein for cultured meat scaffolds: Evaluating gelation, physical properties, and cell adhesion. Food Sci Anim Resour. 2024;44(5):1108–25. PubMed PMID: 39246534; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC11377198.10.5851/kosfa.2024.e46Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] David S, Ianovici I, Guterman Ram G, Shaulov Dvir Y, Lavon N, Levenberg S. Pea protein‐rich scaffolds support 3D bovine skeletal muscle formation for cultivated meat application. Adv Sustain Syst. 2024;8(6):2300499.10.1002/adsu.202300499Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kong Y, Jing L, Huang D. Plant proteins as the functional building block of edible microcarriers for cell-based meat culture application. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;64(15):4966–76. PubMed PMID: 36384368.10.1080/10408398.2022.2147144Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Lam ACY, Can Karaca A, Tyler RT, Nickerson MT. Pea protein isolates: Structure, extraction, and functionality. Food Rev Int. 2018;34(2):126–47.10.1080/87559129.2016.1242135Search in Google Scholar

[20] Shand PJ, Ya H, Pietrasik Z, Wanasundara P. Physicochemical and textural properties of heat-induced pea protein isolate gels. Food Chem. 2007;102(4):1119–30.10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.060Search in Google Scholar

[21] Mession J-L, Assifaoui A, Lafarge C, Saurel R, Cayot P. Protein aggregation induced by phase separation in a pea proteins–sodium alginate–water ternary system. Food Hydrocoll. 2012;28(2):333–43.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.12.022Search in Google Scholar

[22] Morris ER. Functional interactions in gelling biopolymer mixtures. In: Kasapis S, Norton IT, Ubbink JB, editors. Modern biopolymer science. 1st edn. London: Academic Press; Elsevier; 2009. p. 167–98.10.1016/B978-0-12-374195-0.00005-7Search in Google Scholar

[23] Zasypkin DV, Braudo EE, Tolstoguzov VB. Multicomponent biopolymer gels. Food Hydrocoll. 1997;11(2):159–70.10.1016/S0268-005X(97)80023-9Search in Google Scholar

[24] Tolstoguzov VB. Some physico-chemical aspects of protein processing in foods. Multicomponent gels. Food Hydrocoll. 1995;9(4):317–32.10.1016/S0268-005X(09)80262-2Search in Google Scholar

[25] Brownsey GJ, Morris VJ. Mixed and filled gels-models for foods. In: Blanshard JMV, Mitchell JR, editors. Food structure - Its creation and evaluation. London: Butterworths; 1988. p. 7–23.10.1016/B978-0-408-02950-6.50007-8Search in Google Scholar

[26] Wu D, Pang S, Berg J, Mei Y, Ali ASM, Röhrs V, et al. Bioprinting of perfusable vascularized organ models for drug development via sacrificial‐free direct ink writing. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(30):2314171.10.1002/adfm.202314171Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kim JH, Iyer S, Tessman C, Lakshman SV, Kang H, Gu L. Calcium sulfate microparticle size modification for improved alginate hydrogel fabrication and its application in 3D cell culture. Front Mater Sci. 2025;19(1):250713.10.1007/s11706-025-0713-4Search in Google Scholar

[28] Gwon SH, Yoon J, Seok HK, Oh KH, Sun J-Y. Gelation dynamics of ionically crosslinked alginate gel with various cations. Macromol Res. 2015;23(12):1112–6.10.1007/s13233-015-3151-9Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ewoldt RH, Hosoi AE, McKinley GH. New measures for characterizing nonlinear viscoelasticity in large amplitude oscillatory shear. J Rheol. 2008;52(6):1427–58.10.1122/1.2970095Search in Google Scholar

[30] Mezger TG. The rheology handbook. European Coatings Tech Files. 4th edn. Hannover: Vincentz Network; 2014. p. 434.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Ewoldt RH, Winter P, Maxey J, McKinley GH. Large amplitude oscillatory shear of pseudoplastic and elastoviscoplastic materials. Rheol Acta. 2010;49(2):191–212.10.1007/s00397-009-0403-7Search in Google Scholar

[32] van Vliet T, van Dijk HJM, Zoon P, Walstra P. Relation between syneresis and rheological properties of particle gels. Colloid Polym Sci. 1991;269(6):620–7.10.1007/BF00659917Search in Google Scholar

[33] Leelapunnawut S, Ngamwonglumlert L, Devahastin S, Derossi A, Caporizzi R, Chiewchan N. Effects of texture modifiers on physicochemical properties of 3D-printed meat mimics from pea protein isolate-alginate gel mixture. Foods. 2022;11(24):3947. PubMed PMID: 36553689; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9778299.10.3390/foods11243947Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Mession J-L, Blanchard C, Mint-Dah F-V, Lafarge C, Assifaoui A, Saurel R. The effects of sodium alginate and calcium levels on pea proteins cold-set gelation. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;31(2):446–57.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.11.004Search in Google Scholar

[35] Oyinloye TM, Yoon WB. Stability of 3D printing using a mixture of pea protein and alginate: Precision and application of additive layer manufacturing simulation approach for stress distribution. J Food Eng. 2021;288:110127.10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2020.110127Search in Google Scholar

[36] Zhao Y, Li Y, Mao S, Sun W, Yao R. The influence of printing parameters on cell survival rate and printability in microextrusion-based 3D cell printing technology. Biofabrication. 2015;7(4):45002. PubMed PMID: 26523399.10.1088/1758-5090/7/4/045002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Kerchove AJ, de, Elimelech M. Formation of polysaccharide gel layers in the presence of Ca2+ and K+ ions: measurements and mechanisms. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(1):113–21. PubMed PMID: 17206796.10.1021/bm060670iSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Draget KI, Steinsvåg K, Onsøyen E, Smidsrød O. Na- and K-alginate; effect on Ca2+ -gelation. Carbohydr Polym. 1998;35(1–2):1–6.10.1016/S0144-8617(97)00237-3Search in Google Scholar

[39] Di Cocco ME, Bianchetti C, Chiellini F. 1H NMR studies of alginate interactions with amino acids. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2003;18(4):283–96.10.1177/088391103037015Search in Google Scholar

[40] Maciel B, Oelschlaeger C, Willenbacher N. Chain flexibility and dynamics of alginate solutions in different solvents. Colloid Polym Sci. 2020;298(7):791–801.10.1007/s00396-020-04612-9Search in Google Scholar

[41] Gonçalves MP, Sittikijyothin W, Da Silva MV, Lefebvre J. A study of the effect of locust bean gum on the rheological behaviour and microstructure of a β-lactoglobulin gel at pH 7. Rheol Acta. 2004;43(5):472–81.10.1007/s00397-004-0408-1Search in Google Scholar

[42] Fang Y, Al-Assaf S, Phillips GO, Nishinari K, Funami T, Williams PA, et al. Multiple steps and critical behaviors of the binding of calcium to alginate. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(10):2456–62. PubMed PMID: 17305390.10.1021/jp0689870Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Besiri IN, Goudoulas TB, Germann N. Custom-made rheological setup for in situ real-time fast alginate-Ca2+ gelation. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;246:116615. PubMed PMID: 32747255.10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116615Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Sabet S, Rashidinejad A, Melton LD, Zujovic Z, Akbarinejad A, Nieuwoudt M, et al. The interactions between the two negatively charged polysaccharides: Gum Arabic and alginate. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;112:106343.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106343Search in Google Scholar

[45] Sabet S, Seal CK, Swedlund PJ, McGillivray DJ. Depositing alginate on the surface of bilayer emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;100:105385.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105385Search in Google Scholar

[46] Precha-Atsawanan S, Uttapap D, Sagis LM. Linear and nonlinear rheological behavior of native and debranched waxy rice starch gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;85:1–9.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.06.050Search in Google Scholar

[47] Risse K, Drusch S. (Non)linear Interfacial Rheology of Tween, Brij and Span Stabilized Oil-Water Interfaces: Impact of the Molecular Structure of the Surfactant on the Interfacial Layer Stability. Langmuir. 2024;40(34):18283–96. PubMed PMID: 39126646.10.1021/acs.langmuir.4c02210Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Urbonaite V, Jongh H, de, van der Linden E, Pouvreau L. Water holding of soy protein gels is set by coarseness, modulated by calcium binding, rather than gel stiffness. Food Hydrocoll. 2015;46:103–11.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.12.010Search in Google Scholar

[49] Kastner H, Kern K, Wilde R, Berthold A, Einhorn-Stoll U, Drusch S. Structure formation in sugar containing pectin gels - influence of tartaric acid content (pH) and cooling rate on the gelation of high-methoxylated pectin. Food Chem. 2014;144:44–9. PubMed PMID: 24099540.10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.127Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Pacek AW, Ding P, Norton IT. Effect of temperature and hydrodynamic conditions on structure and drop size in a phase-separated gelatin + dextran system. In: Dickinson E, van Vliet T, editors. Food colloids, Biopolymers and Materials. Special publication/Royal Society of Chemistry. Vol 284. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2003. p. 309–18.10.1039/9781847550835-00309Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory