Abstract

Self-compacting concrete (SCC), which can be placed and consolidated under its weight without any vibration effort, was first developed in 1988 to achieve durable concrete structures. Since then, a lot of research has been conducted in order to reduce the consumption of raw materials in SCC. Although coarse aggregate and design methods are known to influence concrete properties, there are still knowledge gaps that need to be filled. This study uses a new source of recycled coarse aggregate (RCA), namely the concrete panels of old large panel system buildings demolished in urban areas. The aim of the study is to verify the effect of this aggregate on the rheological and mechanical properties of SCC. To enhance the properties of SCC, the modified equivalent mortar volume (mEMV) method of designing a concrete mix was used. It has not been verified before for SCC, and a literature review suggests it has the potential to eliminate the drawbacks of ordinary equivalent mortar volume methods. The SCC that was used in the study is characterized by having a high viscosity and an average consistency. The hardened SCC used in the research was highly impacted by its mix design and RCA content. Both compressive strength and abrasion resistance decreased when the RCA content increased. However, using the mEMV method resulted in a 10 and 1% improvement in compressive strength and abrasion resistance, respectively.

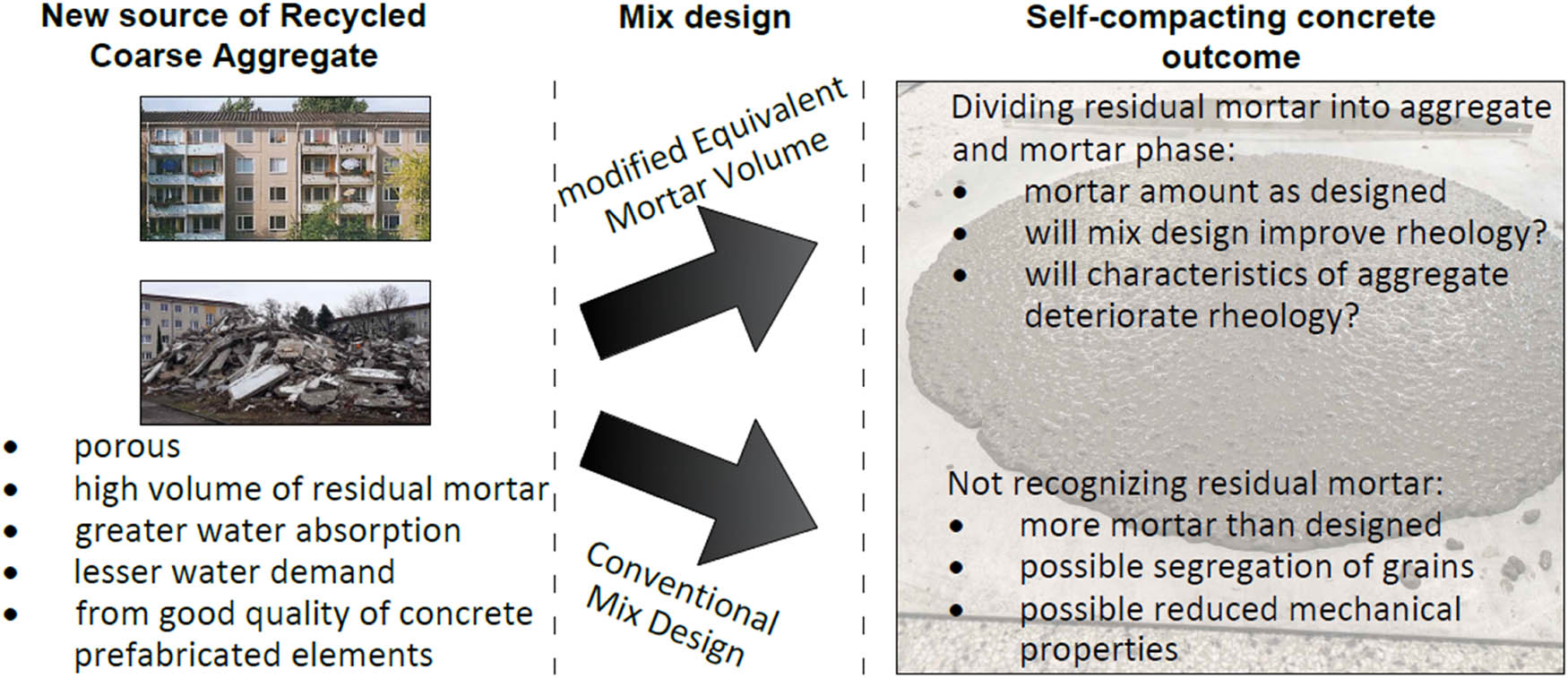

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Self-compacting concrete (SCC) is characterized by good fluidity (the balance between the plastic viscosity and flow limit), stability (a lack of sorting of components), and the ability to flow around reinforcements. Since its development in 1988, it has proven that the aggregate, packing density, water-to-binder ratio (W/B), composition of raw materials, the incorporation of chemical and mineral admixtures, and design methods can influence both hardened SCC and the rheological behaviour of SCC. This was described by Okamura and Ouchi [1]. Martínez-García et al. stated that an increase in the percentage of aggregate in mixes results in an increase in the amount of water required to achieve the same workability [2]. According to Benaicha et al., the fresh and hardened density of SCC and the values of its rheological behaviour (plastic viscosity and yield stress) decrease with an increase in the percentage of the air entraining admixture [3]. Klemczak et al. noticed that a large amount of supplementary cementitious materials, such as fly ash and/or slag, resulted in significantly reduced shrinkage strains when compared to SCC composed solely of ordinary Portland cement [4].

The worldwide trend to reduce the consumption of high-emission, non-renewable, and critical raw materials means that building structures must be optimized. Reducing the consumption of raw materials particularly applies to concrete, which is the most widely used building material in the world. Adesina described the production of concrete as the main factor contributing to global anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions [5]. Replacing natural coarse aggregate (NCA) with recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) is well-known in research and patent solutions. According to Mandal et al., the RCA in SCC enhances the value of the shear yield stress and plastic viscosity [6]. Sun et al. stated that “a brief review of the studies shows that single-scale waste concrete recycling materials can be used to produce SCC.” They also concluded that the flowability of SCC can meet SCC standards if the amounts of RCA are below 50% [7]. Alyaseen et al. suggested that when RCA is used to replace NCA completely, the resulting compressive strength is higher for higher grades of concrete [8]. However, in the case of RCA from waste concrete, Kim and Sadowski proved that the actual mortar content in the mix is higher than the amount that was previously designed. This is because a conventional mix design (CMD) does not take into account the residual mortar (RM) attached to the RCA [9].

Fathifazl et al. claimed that knowledge regarding RM in a concrete mix is essential in ensuring satisfactory properties of fresh and hardened mixes of concrete. RCA, because of RM, lowers the elastic modulus of RCA concrete due to the elastic modulus being a function of the volume fractions and the elastic moduli of the aggregate and the mortar. In turn, compressive strength depends on the strength of the mortar and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ). To overcome problems related to the RM content, the equivalent mortar volume (EMV) method of designing mixes was proposed. It allows the designed total mortar volume (RM and fresh mortar) to be kept by reducing the fresh mortar ingredients, e.g. cement and fine aggregate. Fathifazl et al. showed that EMV concrete has higher values of slump, and a higher fresh and hardened density. It was also shown that modulus and compressive strength values were close to CMD concrete [10]. However, Yang and Lee proved that a lack of cement causes poor performance in slump tests, and in turn, the resulting concrete has worse workability in some applications [11]. The main cause of this is that the RM in RCA is treated as fresh mortar, while in fact it is already a hardened mortar, which has different properties than fresh mortar. Following the idea of EMV, several modified versions of EMV have appeared (modified equivalent mortar volume [mEMV]). They attempt to divide RCA into a coarse aggregate phase and a mortar phase. The literature review (Table 1) shows that only one study on SCC with RCA designed using the EMV method has been conducted. To enhance the properties of SCC with RCA, there is a need for further analysis of SCC concrete design methods and the actual testing of the mEMV method.

Concrete mix design of SCC with examples of applications

| Mix design of SCC | RCA heterogeneity | Described influence on rheology | Exemplary application in SCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMD | RM adhered to aggregate is still a part of coarse aggregate | The reduction in the flowability of a concrete mix due to a too low content of free water, lowering the E-modulus | [13,14] |

| EMV | RM is part of the mortar phase. Coarse aggregate consists of the original VA | Poor performance in slump and workability | [15,16] |

| mEMV | The volume of RM is divided into total mortar and coarse aggregate parts | Not enough data | [17] No other data were found |

Moreover, the RCA used in the research is taken from the concrete panels of large panel system (LPS) buildings constructed in 1960 as part of the New Town neighbourhood in Hoyswerda, Eastern Germany. It differs from other known sources of RCA because it has a high RM content compared to aggregates taken from the demolition of other buildings. This particular source of RCA is still unexplored, and there is no research on recycling concrete panels from LPS buildings [12]. LPS neighbourhoods built between 1945 and 1990 are a common sight in Eastern Europe in dense urban areas, and in the future, some of them will have to be demolished. This study aims to verify the influence of RCA (from specific LPSs) on selected properties of SCC.

2 Research significance

A new source of RCA from the concrete panels of old LPS buildings from urban area is proposed. For the optimal design of SCC, the mEMV method of mix design was used. A detailed literature review shows that designing a concrete mix with the use of this method has the potential to strengthen properties such as compressive strength and abrasion resistance, as well as eliminate the drawbacks of the ordinary EMV method. However, the mEMV method has not previously been verified for SCC. Thus, this study analyses the properties of a fresh and hardened mix of SCC made with RCA in order to confirm that the mEMV mix design has the potential to enhance the properties of the obtained SCC.

3 Materials

SCC, compared to ordinary concrete, consists of additional components and has different material ratios. The most important recommendations for the composition of the SCC mix are shown in Table 2.

Recommendations for the composition of SCC

| Recommendation | Effect on rheological properties | Effect on hardened properties |

|---|---|---|

| Limiting the amount of coarse aggregate | Ensuring an appropriate grain size distribution (which is associated with a higher content of fine fractions – including sand) and ensuring the flow of the mixture | The mechanical properties of SCC mixes containing coarse aggregate of a smaller size have increased values [18] |

| Low water/binder ratio (W/B) | High ratios can cause blocking or segregation of the mixture | Rapid strength growth by reducing the free water content and W/B [19] |

| Use of superplasticizers | Increasing the superplasticizer dosage causes an increase in the slump flow diameter and a decrease in the yield stress and the plastic viscosity values | The compressive strength decreases with an increase in the superplasticizer dosage [20] |

3.1 NCA

Pebble aggregate, due to its smooth surface, makes the preparation of SCC easier (the rougher surface texture of the particles can cause segregation). There is a lower risk of aggregate grains being blocked against each other. Dolomite has already been successfully applied in SCC mixes and was therefore chosen as the NCA for this study. Samples were acquired from a dolomite mine in Boleslaw, Poland. Langer and Knepper characterized dolomite as having high water absorption and porosity [21]. Shi et al. pointed out that it potentially has reactive components, which may cause alkaline reactivity [22].

3.2 RCA

The source of the RCA was pieces of concrete panels acquired from the demolition of a 4-story residential building constructed using LPS technology in around 1960. The building was located in a dense urban area (New Town neighbourhood in Hoyerswerda) in Germany (Figure 1). According to documentation, the panels were prepared with concrete class C 12/15. Old LPS buildings (executed before 1990) are a large part of the housing stock in Central and Eastern Europe. Nowadays, endless discourses take place on whether the residents should be concerned about their flats being demolished. Taking into account progressive collapse, planned demolitions, and sudden disasters like gas explosions, the trend can result in the creation of huge amounts of waste. As LPS buildings are usually located in city centres, the significant costs of transporting demolished concrete should also be taken into account. Instead of storing the material in landfills, there is the potential to use the concrete panels from LPS buildings as good-quality coarse aggregate. According to the authors’ previous study, they are prefabricated with good quality concrete and are still in satisfactory conditions [23]. However, the current state of knowledge does not yet provide any information on the use of RCA acquired from LPS buildings in SCC. Ongoing research will explore this possibility in detail.

RCA used in this study: (a) location of the obtained waste, (b) LPS before demolition, (c) exact location in the town – marked with a red circle, and (d) LPS building after demolition.

3.2.1 RM content

Comparing coarse aggregates using a scanning electron microscope, as can be seen in Figure 2, allows the pores, RM, and virgin aggregate in the RCA to be fully seen. Although several studies have focused on estimating the content of RM, Kim and Sadowski observed that there are no standard regulations [9]. Raman and Ramasamy suggested the following solutions: acid treatment, mechanical treatment, and thermal treatment [24]. The advantages of acid treatment (Figure 3) involve the shorter duration time when compared to other methods and the fact that no special equipment or intervention is needed during the test. Due to the fact that there is no European Union standard regarding RCA being treated using acid, the authors used the method of Kim [25]. The results of the study, shown in Table 3, are consistent with those presented by Pandurangan et al. [26]. The molarity of HCl was chosen to be 0.1 M. According to Ismail and Ramli, an increased molarity (of 0.8 M) resulted in a greater loss of recycled aggregate mortar [27]. Unfortunately, this led to both the erosion and increased surface porosity of the original aggregate. Determining adhered mortar volume is necessary for the mEMV mix design.

Coarse aggregate: (a) recycled and (b) natural.

Acid treatment of the aggregate (with visible detachments in red).

Results of the adhered mortar content

| Aggregate size (mm) | RM content (%) |

|---|---|

| 6.3–8 | 12.56 |

| 5–6.3 | 11.47 |

| 4–5 | 13.51 |

3.3 Comparison of the coarse aggregates

As shown in Table 4, it can be concluded that dolomite NCA is a high-quality aggregate with an oven-dried density of over 2.5 g/cm3 and water absorption of below 3.0%. RCA from the demolition of concrete LPS buildings can be qualified as medium-quality aggregate with an oven-dried density of <2.5 g/cm3 (but >2.3 g/cm3) and water absorption of >3.0% (but <5.0%). The water absorption of RCA is higher than NCA. This is because of the higher porosity of RCA due to the higher content of adhered mortar. Therefore, the percentage of replacement of NCA with RCA should be supported by the fulfilment of the assumed concrete strength requirements. This is why coarse aggregate replacement should not exceed 30% of the total coarse aggregate content. To precisely examine individual series, the replacement percentages were set to 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30% of the total coarse aggregate content.

Densities and water absorption of the coarse aggregates

| RCA (g/cm3) | NCA (g/cm3) | Quality based on Ref. [28] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apparent particle density

|

2.45 | 2.85 | For ≥2.5, high quality; for ≥2.3, medium quality |

| Oven-dried particle density

|

2.24 | 2.67 | For ≥2.5, high quality; for ≥2.3, medium quality |

| Saturated and surface-dried particle density

|

2.33 | 2.75 | For ≥2.5, high quality; for ≥2.3, medium quality |

| Water absorption (%) | 3.81 | 2.34 | For ≤3.0, high quality; for ≤5.0, medium quality |

Soni and Shukla stated that the water requirement for coarse aggregate can depend on the morphology of grains, surface roughness, size of grains, their proportion, and the required consistency of the concrete mix [29]. This study used a water requirement determined by Jamroży, who analysed methods of Soroka and Stern [30], studies concerning Bolomey’s water requirement such as [31] and proposed aggregate water demand indicators [32]. The water demand for cement and aggregate should be determined jointly, i.e. in a common relationship with the aggregate and cement. By knowing the apparent particle density, the water demand for aggregate can be obtained by dividing the standard density of 2.65 g/cm3 by the density of the given aggregate and then multiplying it by the water index. The results of water demand are shown in Table 5. In terms of particle size distribution, both aggregates have very similar grain sizes and were prepared using the same equipment (Figure 4).

Results of the water requirement of the coarse aggregates

| Coarse aggregate type | Grain size (mm) | Water index | Apparent particle density (g/cm3) | Water demand (kg/kg of aggregate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | 4–8 | 0.026 | 2.45 | 0.0281 |

| Recycled | 4–8 | 0.026 | 2.85 | 0.0242 |

Aggregate used in this study: (a) coarse natural, (b) coarse recycled, (c) particle size distribution for the fine aggregate, and (d) particle size distribution for the RCA and NCA.

3.4 Other ingredients

Quartz sand was chosen for the fine aggregate, with sieve analysis being performed to determine the particle size distribution. The grain sizes varied from 0.25 to 2 mm. The selected sieve was determined to be half of the maximum size of the particle of a certain fraction (d max/2). The particle size distribution is shown in Figure 4.

Wu et al. suggested that the type of coarse aggregate influences the strength of concrete more significantly in the case of high-strength concrete. In concrete with a target strength of 30 MPa, strength differences between concretes that were made with different coarse aggregates are reduced [33]. Therefore, Portland cement CEM I 32.5R Artcem was chosen for this study (Figure 5).

Cement composition.

Fly ash was added to every series. The fly ash was obtained from the power plant in Jaworzno, which is operated by Tauron – a Polish energy industry company.

The amount of superplasticizer was limited to a maximum of 5% of the cement mass.

3.5 Proportions of the ingredients

Based on the authors’ previous experience with the mix design of SCC mix, the following proportion of CMD concrete mix was proposed [34,35]. The ingredients were compared with the guidelines for SCC, which are shown in Table 6.

Proposed SCC mix, with a comparison to the guidelines for SCC

| Ingredient | Proposed amount of CMD mix (kg/m3) | General SCC design principles |

|---|---|---|

| CEM I 32.5R | 550 | 300–550 kg/m3 |

| Fine aggregate | 850 | 40–50% of the total aggregate |

| Coarse aggregate grain sizes of 4–8 mm | 950 | Maximum size of grains – 20 mm |

| Water | 173 | 160–200 kg/m3 |

| Fly ash | 66 | 15–40% of weight of cement |

4 Methods

4.1 Mix design method

Kim and Sadowski [9] conducted an extensive literature review on different EMV methods. An interesting mixture design that could theoretically be used in SCC was presented by Yang and Lee [11]. They introduced the S-factor, which helps to divide the RM content into aggregate and mortar phases. Their mEMV method resulted in increased compressive strength by 6.7–8.8% by day 7, with elastic modulus increasing by 2–8.7%. The main difference between the mEMV method and the EMV method is the modification of the NA input ratio (equation (1)), and the introduction of the S-factor in equation (2).

The NA input ratio (equation (1)),

where

S-factor 2 was applied for a 50% replacement rate, and 3 was applied to a 75% replacement rate.

The total volume of mortar in the RAC:

The total volume of NCA in the RAC:

The volume of RA and NCA in the RAC:

After applying the NCA input ratio (equation (2)) and the total volume of NCA in the RAC (equation (4)) into the volume of RA in the RAC (equation (5)), the following can be concluded:

where

The oven-dried weight of the RA in the RAC:

The oven-dried weight of the NCA in the RAC:

The new mortar volume in the RAC:

The weight of water in the RAC:

The weight of cement in the RAC:

The weight of the fine aggregate in the RAC:

The order of calculations

Proportioning the mix based on a chosen standard

Determining the weight of the water, cement, and oven-dry NA in the NAC

Applying the S-factor in the RMC calculations and the R ratio (equation (2))

Calculating the volume of the RA and NCA in the NAC from equation (7)

Calculating the oven-dry weight of the RA in the RAC mix from equation (8)

Calculating the oven-dry weight of the NCA in the RAC mix from equation (9)

Calculating the new mortar in the RAC mix from equation (10)

4.2 Preparation and testing of the samples

For every series, two mix designs were considered: CMD and mEMV. Every series of the single mix design included five samples. All the series differed with regards to the replacement of NCA by RCA (interval 5%), and also their mix design (mEMV and CMD). The samples were 10 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm for the compressive strength test and 7, 1 × 7, 1 × 4 cm for the abrasion resistance test. The fresh properties for every SCC series were verified using an Abrams cone and flow plate. The mixture was poured into moulds, from which samples were taken out after 24 h and placed in a water bath. After 28 days, the samples were dried and subjected to tests. The tests of the properties of the hardened samples included the verification of their compressive strength (the basic parameter of concrete) and abrasion resistance – as SCC is often used as a floor or base. For the compressive strength test, the samples were dried, measured, and weighed according to PN-EN 206+A1:2016-12. The tests were performed on a hydraulic press ZD100. For the abrasion resistance test, the samples were dried, measured, and weighed according to PN-EN 14157:2017-11. The tests were performed according to the Bohme disc method, and involved grinding the samples using 22 turns of the disc, turning the samples over, and then grinding them again for up to 16 cycles.

5 Results

5.1 Results of the rheological properties

Consistency, the ability of a mixture to flow, is defined by measuring the flow in two directions and by calculating the average value (Figure 6). Along with this method, the plastic viscosity of the concrete mixture was checked by determining the time t500, which was measured from the moment of lifting the cone to the mix, reaching a diameter of 500 mm. The results are shown in Figure 7 and were compared with the classes of consistency and viscosity.

Fresh mix without segregation and with a stable flow.

Results of the fresh mix: (a) flow time with marked viscosity class and (b) flow with marked consistency class.

For most of the mixes, the CMD mix design was characterized by having a longer flow time, which means an increased viscosity (Figure 7a). The difference between additional design methods that use the same aggregate replacement is less than 3 s for all the series. Both mix methods, for all the replacements, did not exceed 11 s in reaching the t500 marking. However, none of them can be defined as a VS1 class. Viscosity was not decreased by replacing the NCA with RCA. Up to 30% of replacement, the difference in the flow time between the series and reference mix was below 1 s. The SCC mixture in the study is characterized by a total flow time of between 8 and 10.5 s; therefore, the SCC requires some time to tightly fill the formwork. The VS2 class is characterized by the risk of bubbles appearing on the surface of an element. It is not recommended to use SCC of this class for architectural concrete or in areas of very dense reinforcement. It is recommended, however, when concreting high vertical elements. The results were compared with recent studies that used RCA (from concrete waste) in SCC. The comparison shows that the designed SCC has a high viscosity and is, therefore, more resistant to segregation. As was the case with Sun et al. and Guo et al., the use of RCA did not reduce the viscosity. Therefore, the proposed new RCA can be used in SCC [7,36]. During the consistency test, it was proven that the sedimentation of the aggregate grains or the separation of the cement paste did not occur, and therefore, the mix can be said to be resistant to segregation (Figure 7b). The series with a 10, 15, 20, and 30% replacement of aggregate (CMD method) are characterized by having a greater flow compared to mEMV. The series with a 10, 15, and 20% replacement of aggregate (CMD method) was determined to be in the SF3 class, while the mEMV series with the same replacements of aggregate remained in the SF2 class. Similar to viscosity, consistency was decreased by replacing the NCA with RCA. This is beneficial when compared with recent studies. Guo et al. [36] obtained much lower consistency. However, Sun et al. [7] observed a continuous decrease in consistency when increasing the amount of RCA. Consistency determines the flow of a mixture and, therefore, the possibility of proper implementation of the technological processes. The lower the consistency class, the smaller the height of the cone that causes the mix to flow, which in turn results in better levelling of the concrete in a formwork.

According to the recommendations [37], SCC in the SF2 class can be used to form horizontal and vertical elements (such as walls and columns) with normal reinforcement. Both rheological parameters were compared with the data from the literature. The use of the new type of RCA did not improve workability. The workability did not decrease, even when the RCA content was increased to 30%. The RCA in this study is a porous material with a higher water absorption than NCA. The results of rheology are surprising because the literature review suggests that there will be changes in rheology when replacing NCA with RCA. This is due to the aggregate’s water requirement, wettability, and differences in the grain geometry. The RCA from concrete waste was crushed in the laboratory, and the NCA was acquired from different industrial crushers. Due to its properties, the proposed RCA can prevent a negative influence of the aggregate on SCC, such as grain segregation or mix bleeding.

5.2 Results of the tests of properties of the hardened concrete samples

The mix methods and the replacement of the NCA with RCA affected the hardened properties. Figure 8a shows that for every replacement that was checked, mEMV always presented greater compressive strength. The superiority of mEMV over CMD increases after every larger replacement of NA with RCA. The graph presents the average values for five samples of each series. For 5% replacement, the difference favouring mEMV is equal to 0.5 MPa. It increases with every replacement, reaching 3 MPa for the 30% replacement. Although mEMV helped to reduce the decrease of compressive strength, the loss of values comparing the 30% replacement with the reference mix (0%) is undesirable (10.5 MPa for CMD and 7.5 for mEMV).

Results of (a) compressive strength, (b) abrasion resistance, and (c) the correlation matrix between the mechanical properties for the CMD and mEMV mix methods.

For abrasion resistance, which is shown in Figure 8b, the samples with 5 and 10% replacement for both mix methods had a similar mass loss. Starting from 15%, mEMV provided a lower mass loss by about 1% for each series compared to the CMD concrete. For an exemplary 1,000 kg element, this equates to an optimization of 10 kg. The big drop in abrasion resistance starts with a 15% replacement. The loss of abrasion resistance is consistent with the results of compressive strength, in which for a 10% replacement of NCA with RCA, a decrease in mechanical properties is visible. The total decrease in the mechanical property values between the reference mix and mix with 30% of NCA replaced with recycled aggregates amounted to a 2.46% mass loss for the CMD and 1.55% for the mEMV. According to PN-EN 13813:2003, all the samples fall within class A15 (from 22 to 15 cm3/50 cm2). Figure 8c presents the correlation matrix for both mechanical properties. A high correlation between compressive strength and mass loss in the case of abrasion can be observed.

6 Discussion

This study analysed the rheological and mechanical parameters of SCC based on the characteristics of the coarse aggregate and the mix design method. The results of the tests and the impacts of the components on each other are summarized in Figure 9a. Interestingly, the rheological parameters did not decrease to such an extent as the mechanical properties. New RCA from LPS buildings contributed to a stable viscosity and consistency. This is especially beneficial for SCC, where workability is more important than in the case of ordinary concrete. As can be seen in Figure 9b, there is no significant impact of the rheological properties on the mechanical properties. In fact, a strong correlation is only visible between the compressive strengths obtained by different mix design methods (CMD and mEMV). Although RCA did not deteriorate rheology, it cannot be said that there is no influence. A deeper analysis of the characteristics of RCA can provide answers to this inaccuracy. Based on the rheology results, the amount of RCA was chosen correctly, and the results are in accordance with the literature review. A greater replacement of NCA to RCA is associated with a further decrease in mechanical properties and is, therefore not suitable. RCA is characterized by having a 1.47% greater water absorption than NCA and by a 0.0039 kg/kg lesser water demand than NCA. The above properties and the maintaining of a constant W/B ratio resulted in a sufficient amount of free water (which enables the flow of the mixture) and an appropriate amount of cement paste (limiting the packing of large aggregate grains, thus resulting in a lack of segregation). All of this contributed to an acceptable rheology (Figure 10).

Correlation between elements: (a) impact based on the results and (b) matrix between rheological parameters and compressive strength.

Reasons for achieving a satisfactory rheology.

The obtained rheology and the state of the mixture allowed a theoretical model of the SCC cross-section to be proposed, as presented in Figure 11. No segregation was observed, and this allows for an assumption that SCC with RCA has the potential to be more homogenous than ordinary concrete. Enough free water allows the mix to flow, even though RCA has a greater water absorption. This may result in less bleeding (pushing free water upwards), and therefore, the area close to the surface would not be a weak point. This is especially important as, based on the results, SCC could be used for industrial floors. However, the porous characteristics of RCA and its medium quality caused a deterioration in mechanical properties. The reason for this could be due to the ITZ, which may lack cement grains. Moreover, it has a different microstructure than cement paste. These theories should be proved by scientific research and be the subject of future studies.

Theoretical model of the cross-section of the SCC, which needs to be confirmed in future studies.

7 Perspectives for future studies

The characteristics of the RCA contributed to the stable rheology of the SCC. This allowed a theoretical model of the cross-section of the SCC to be created. It needs to be confirmed in future studies by analysing the bleeding, heterogeneity of concrete, and the ITZ of aggregate. To incorporate waste in large doses in SCC, and therefore, to actually reduce possible landfills, the authors suggest conducting further studies that will focus on enhancing the mechanical properties of SCC. Possible solutions include a higher class of cement, the pre-treatment of RCA, or using ingredients that can improve concrete properties. The change of concrete from a suspension into a durable construction material will be verified by tests of setting time and changing modulus of elasticity. The above analyses will be supported by the model to confirm concrete behaviour.

8 Conclusions

The study analyses the properties of the fresh and hardened mix of SCC, which is made with RCA, using the CMD and mEMV methods. A new source of RCA from the demolition of old LPS buildings from 1960 (built in a dense urban area) is introduced. Old LPS buildings (constructed before 1990) are very common in urban areas in Central and Eastern European countries and may be subjected to demolition in the near future. This study is part of the first ever project to apply concrete panels from old LPS buildings as RCA in SCC. The replacement of NCA varies from 0 to 30% of the total coarse aggregate phase. When analysing the results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Rheology was not deteriorated by the RCA content. However, even small amounts of RCA decreased the properties of the hardened concrete.

New RCA from LPS buildings contributed to the stable viscosity and consistency, thus proving that it is especially beneficial for SCC, where workability is more important than in ordinary concrete.

One optimization method used is the mEMV mix design. This method allows us to improve SCC hardened properties compared to the CMD method. Although mEMV limited the deterioration of compressive strength and abrasion resistance, it did not enhance these properties compared to the reference mixture. However, the authors underline the importance of the mEMV method when preparing many series with the same RCA from a known source of concrete waste. This can be beneficial for low class concrete in which every difference in property counts.

An unknown source of RCA, different RCA sources in one mix, or small amounts of mixes can be a drawback when using mEMV optimization. The RM content, and therefore, the changing amounts of the mixture components, must be calculated, which requires time and equipment. Ideally, RCA should come from a known source.

Based on rheological parameters (relatively high viscosity, resistance to segregation, and middle class consistency), the proposed SCC could be used for horizontal elements and vertical ones such as walls and columns (with standard density of reinforcement). The authors suggest that in the case of possible demolition of LPS buildings, SCC with RCA could be applied for new investments. Structural elements (walls and columns) could contain RCA, which limits the logistical process of transporting demolition waste to landfills. Because SCC can contribute to easier concreting with fewer workers and less noise, it is suitable for dense urban areas where LPS buildings are located.

Acknowledgements

The team gratefully acknowledges the support from the Centre for Urban Innovation: Architecture, Engineering, Technology at the Wroclaw University of Science and Technology (https://cim.pwr.edu.pl/).

-

Funding information: This research was funded from a project supported by the National Centre of Science, Poland [Grant no. 2020/39/O/ST8/01217 “Experimental evaluation of the fundamental properties of self-compacting concrete made of recycled coarse aggregate sourced from the demolition of large panel system buildings (RECSCCUE)”].

-

Author contributions: Seweryn Malazdrewicz – conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data (specification of materials), contributed data or analysis tools (mix design analysis and proportion of ingredients), performed the analysis (preparing the concrete mix, analysing coarse aggregate properties, fresh and hardened properties of concrete), wrote the paper (initial draft). Krzysztof Adam Ostrowski – conceived and designed the analysis, performed the analysis (preparing the concrete mix and fresh properties of concrete), and made other contributions (revision, suggestions for analysis, and acceptance of the manuscript). Łukasz Sadowski – conceived and designed the analysis and other contributions (revision, suggestions for analysis, and acceptance of the manuscript).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript, and there is no financial interest to report. We certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Okamura H, Ouchi M. Self-compacting concrete. J Adv Concr Technol. 2003;1(1):5–15.10.3151/jact.1.5Search in Google Scholar

[2] Martínez-García R, Jagadesh P, Fraile-Fernández FJ, Morán-del Pozo JM, Juan-Valdés A. Influence of design parameters on fresh properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled aggregate – a review. Materials. 2020 Jan;13(24):5749.10.3390/ma13245749Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Benaicha M, Jalbaud O, Alaoui AH, Burtschell Y. Porosity effects on rheological and mechanical behavior of self-compacting concrete. J Build Eng. 2022 May;48:103964.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103964Search in Google Scholar

[4] Klemczak B, Gołaszewski J, Smolana A, Gołaszewska M, Cygan G. Shrinkage behaviour of self-compacting concrete with a high volume of fly ash and slag experimental tests and analytical assessment. Constr Build Mater. 2023 Oct;400:132608.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132608Search in Google Scholar

[5] Adesina A. Recent advances in the concrete industry to reduce its carbon dioxide emissions. Environ Chall. 2020 Dec;1:100004.10.1016/j.envc.2020.100004Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mandal R, Kumar Panda S, Nayak S. Rheology of self-compacting concrete: A critical review and future perspective. Mater Today: Proc. 2023;93:265–70.10.1016/j.matpr.2023.07.180Search in Google Scholar

[7] Sun C, Chen Q, Xiao J, Liu W. Utilization of waste concrete recycling materials in self-compacting concrete. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020 Oct;161:104930.10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104930Search in Google Scholar

[8] Alyaseen A, Poddar A, Alahmad H, Kumar N, Sihag P. High-performance self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate: comprehensive systematic review on mix design parameters. J Struct Integr Maint. 2023 May;8(3):161–78.10.1080/24705314.2023.2211850Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kim J, Sadowski Ł. The equivalent mortar volume method in the manufacturing of recycled aggregate concrete. Czas Tech. 2019;116(11):123–40.10.4467/2353737XCT.19.119.11335Search in Google Scholar

[10] Fathifazl G, Abbas A, Razaqpur AG, Isgor OB, Fournier B, Foo S. New mixture proportioning method for concrete made with coarse recycled concrete aggregate. J Mater Civ Eng. 2009 Oct;21(10):601–11.10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2009)21:10(601)Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yang S, Lee H. Mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete proportioned with modified equivalent mortar volume method for paving applications. Constr Build Mater. 2017 Apr;136:9–17.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.01.029Search in Google Scholar

[12] Malazdrewicz S, Adam Ostrowski K, Sadowski Ł. Self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregates from concrete construction and demolition waste – Current state-of-the art and perspectives. Constr Build Mater. 2023 Mar;370:130702.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130702Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yu F, Wang M, Yao D, Liu Y. Experimental research on flexural behavior of post-tensioned self-compacting concrete beams with recycled coarse aggregate. Constr Build Mater. 2023 May;377:131098.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131098Search in Google Scholar

[14] Nadour Y, Bouziadi F, Hamrat M, Boulekbache B, Amziane S, Haddi A, et al. Short- and long-term properties of self-compacting concrete containing recycled coarse aggregate under different curing temperatures: experimental and numerical study. Mater Struct. 2023 Apr;56(4):83.10.1617/s11527-023-02168-ySearch in Google Scholar

[15] Sallai HH, Bouhamou NE, Marouf H, Belghit A, Aydin AC. Influence of calcined dam mud on the thermal conductivity of binary and ternary self-compacting concrete mixtures using the equivalent mortar method. Stud Eng Exact Sci. 2024 Mar;5(1):501–24.10.54021/seesv5n1-029Search in Google Scholar

[16] Amara H, Arabi N. Resting time effects on flow properties of cementitious materials: a study on self-compacting concrete equivalent mortar made with recycled aggregates. Eur J Environ Civ Eng. 2024;28(16):1–27.10.1080/19648189.2024.2363453Search in Google Scholar

[17] Li P, Ran J, An X, Bai H, Nie D, Zhang J, et al. An enhanced mix-design method for self-compacting concrete based on paste rheological threshold theory and equivalent mortar film thickness theories. Constr Build Mater. 2022 Sep;347:128573.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128573Search in Google Scholar

[18] Tran-Duc T, Ho T, Thamwattana N. A smoothed particle hydrodynamics study on effect of coarse aggregate on self-compacting concrete flows. Int J Mech Sci. 2021 Jan;190:106046.10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.106046Search in Google Scholar

[19] Basu P, Chandra Gupta R, Agrawal V. Effects of sandstone slurry, the dosage of superplasticizer and water/binder ratio on the fresh properties and compressive strength of self-compacting concrete. Mater Today: Proc. 2020;21:1250–4.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.01.113Search in Google Scholar

[20] Benaicha M, Hafidi Alaoui A, Jalbaud O, Burtschell Y. Dosage effect of superplasticizer on self-compacting concrete: correlation between rheology and strength. J Mater Res Technol. 2019 Apr;8(2):2063–9.10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.01.015Search in Google Scholar

[21] Langer WH, Knepper DH. Geologic characterization of natural aggregate: a field geologist’s guide to natural aggregate resource assessment. Aggregate resources. London: CRC Press; 2022. p. 275–93.10.1201/9781003077954-18Search in Google Scholar

[22] Shi C, Shi Z, Hu X, Zhao R, Chong L. A review on alkali-aggregate reactions in alkali-activated mortars/concretes made with alkali-reactive aggregates. Mater Struct. 2015 Jan;48(3):621–8.10.1617/s11527-014-0505-2Search in Google Scholar

[23] Malazdrewicz S, Ostrowski KA, Sadowski Ł. Large panel system technology in the second half of the twentieth century – literature review, recycling possibilities and research gaps. Buildings. 2022 Oct;12(11):1822.10.3390/buildings12111822Search in Google Scholar

[24] Raman JVM, Ramasamy V. Various treatment techniques involved to enhance the recycled coarse aggregate in concrete: A review. Mater Today: Proc. 2021 Jan;45:6356–63.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.935Search in Google Scholar

[25] Kim J. Properties of recycled aggregate concrete designed with equivalent mortar volume mix design. Constr Build Mater. 2021 Sep;301:124091.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124091Search in Google Scholar

[26] Pandurangan K, Dayanithy A, Om Prakash S. Influence of treatment methods on the bond strength of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2016 Sep;120:212–21.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.05.093Search in Google Scholar

[27] Ismail S, Ramli M. Engineering properties of treated recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) for structural applications. Constr Build Mater. 2013 Jul;44:464–76.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[28] Kim J. Influence of quality of recycled aggregates on the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concretes: An overview. Constr Build Mater. 2022 Apr;328:127071.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127071Search in Google Scholar

[29] Soni N, Shukla DK. Analytical study on mechanical properties of concrete containing crushed recycled coarse aggregate as an alternative of natural sand. Constr Build Mater. 2021 Jan;266:120595.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120595Search in Google Scholar

[30] Soroka I, Stern N. Calcareous fillers and the compressive strength of portland cement. Cem Concr Res. 1976 May;6(3):367–76.10.1016/0008-8846(76)90099-5Search in Google Scholar

[31] Kubissa J, Koper M, Koper W, Kubissa W, Koper A. Water demand of concrete recycled aggregates. Procedia Eng. 2015;108:63–71.10.1016/j.proeng.2015.06.120Search in Google Scholar

[32] Jamroży Z. Beton i jego technologie/Concrete and its technology. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN (in Polish); 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Wu KR, Chen B, Yao W, Zhang D. Effect of coarse aggregate type on mechanical properties of high-performance concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2001 Oct;31(10):1421–5.10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00588-9Search in Google Scholar

[34] Ostrowski K, Sadowski Ł, Stefaniuk D, Wałach D, Gawenda T, Oleksik K, et al. The effect of the morphology of coarse aggregate on the properties of self-compacting high-performance fibre-reinforced concrete. Materials. 2018 Aug;11(8):1372.10.3390/ma11081372Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Ostrowski K. The influence of coarse aggregate shape on the properties of high-performance, self-compacting concrete. Tech Trans. 2017;114(5):25–33.10.4467/2353737XCT.17.066.6423Search in Google Scholar

[36] Guo Z, Zhang J, Jiang T, Jiang T, Chen C, Bo R, et al. Development of sustainable self-compacting concrete using recycled concrete aggregate and fly ash, slag, silica fume. Eur J Environ Civ Eng. 2020;26(4):1–22.10.1080/19648189.2020.1715847Search in Google Scholar

[37] Self-Compacting Concrete European Project Group. The European guidelines for self-compacting concrete: Specification, production and use. Brussels, Belgium: International Bureau for Precast Concrete (BIBM); 2005.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory