Abstract

Chemical admixtures enhance concrete’s properties and performance, addressing diverse construction needs. This study investigates the effects of polyacrylamide (PAM) in combination with the accelerators calcium chloride (CaCl2) and triethanolamine (TEA) on the early hydration of cement, with a particular focus on static yield stress. To assess the impact of these admixtures on hydration kinetics and material properties, we employed various analytical methods, including calorimetric tests, thermogravimetric analysis, X-ray diffraction, inductively coupled plasma experiments, and the penetration method. The results indicate that CaCl2 accelerates the early hydration of C3S, promoting the formation of C–S–H and CH while facilitating the conversion of AFt to Friedel’s salt. PAM helps to regulate AFt behavior, reinforcing the beneficial effects of CaCl2. Additionally, TEA influences the hydration of C4AF, enhancing AFt precipitation, while higher dosages modify early hydration dynamics by delaying C3S hydration. The interaction between PAM and TEA enhances clinker dissolution, significantly increasing static yield stress through complexation reactions mediated by iron ions. These findings highlight the potential for tailored admixture formulations that combine PAM with traditional accelerators to optimize cement hydration and improve material performance.

1 Introduction

Cement-based materials (CBMs) undergo significant transformations from fresh to hardened states, driven by a series of chemical and physical changes [1,2,3,4,5,6]. These transformations critically impact the material’s performance characteristics. In the context of 3D concrete printing, one particularly vital transformation is the development of static yield stress [4,7,8]. This parameter determines the capacity of the material to support subsequent layers effectively without undergoing deformation. Given its crucial role in successfully applying 3D printing technologies in construction, static yield stress has attracted substantial interest from industry and academia.

The evolution of static yield stress over time is primarily influenced by the hydration process of cement and the micro-level interactions among colloidal particles [8,9]. Various admixtures, such as thickening agents, have been utilized to modify and control CBM properties by conducting numerous studies [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Polyacrylamide (PAM) is a synthetic polymer derived from acrylamide monomers, notable for its high molecular weight and efficacy as a flocculant in applications like water treatment, enhanced oil recovery, and soil conditioning [10]. Specifically, PAM is often employed as a flocculant in sand-washing processes to bind fine particles together into larger aggregates. This can lead to some PAM remaining within the sand, subsequently influencing the properties of cement concrete [16,17]. The effect of PAM as a thickening agent on the development of the microstructure and the rheological properties of concrete has been extensively studied. Research by Sun and Xu [18] demonstrates that PAM not only enhances the mechanical strength of concrete but also affects the workability of CBMs at various dosages during the early stages of hydration, forming gel-like ionic compounds with cations such as calcium ions. Experiments by Yao et al. [19] indicate that PAM dosages <0.25 wt% decrease setting times, while higher dosages retard cement hydration, suggesting a dosage-dependent effect on static yield stress. Bessaies-Bey et al. [10] found that PAM forms microgels and adsorbs onto cement particles, with Ca-ions facilitating the shrinkage and cross-linking of these gels. It can be inferred that using PAM can change the structural integrity and workability of CBMs, making it a practical component for tailoring material characteristics to meet specific construction needs.

The research on the combined use of PAM and accelerators (e.g., TEA or CaCl2) in CBMs is crucial for enhancing construction processes and improving material properties. Accelerators play a key role in shortening setting times and boosting early strength, enabling faster construction and supporting advanced techniques like 3D concrete printing, where rapid execution and precision are essential [8,20,21,22]. Understanding the interrelations between PAM and accelerators could unlock significant optimizations, allowing for a reduction in accelerator usage while maintaining or improving performance. This lowers material costs and minimizes potential issues linked to excessive accelerator use, such as reduced durability. Such advancements would make 3D printing processes more cost-effective and sustainable, tailored for specific environmental conditions and usage demands.

In this study, we aim to investigate the effects of combining PAM with accelerators, specifically calcium chloride (CaCl2) and triethanolamine (TEA), on the evolution of the static yield stress of cement paste during early hydration. Utilizing a comprehensive set of experimental techniques, including calorimetric tests, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and ICP-OES, we analyze the interplay between these admixtures and their influence on hydration kinetics and rheological properties. This work provides a detailed exploration of how PAM moderates the effects of accelerators, such as enhancing hydration product formation and modifying the dissolution dynamics of cement phases. By understanding these mechanisms, the study offers insights into optimizing admixture formulations to achieve desired material properties, with implications for reducing accelerator usage and improving the cost-efficiency of advanced construction techniques like 3D concrete printing.

2 Materials and experiments

2.1 Materials

Ordinary Portland cement (OPC, CEM I 42.5R) provided by HeidelbergCement (Germany) was used, and its composition is listed in Table 1. The cement has a Blaine-specific surface area of 3,500 cm2/g and a density of 3.14 g/cm3, respectively. Further information, including the particle size, can be found in the previous publication [23]. The PAM used is an anionic type with an anionicity of 30% and a molecular weight of 4 million Da (see Figure 1 for chemical structure) and was purchased from Meiyu Chemical Industry (Jinan, China). The accelerators, CaCl2·2H2O from VWR (Germany) and analytical grade TEA (TEA) from J&K Chemical Technology (China), were also used, and the purity of both is >98 wt%.

Chemical and mineralogical composition of cement (data taken from the study of Pott et al. [23])

| Oxide | wt% | Oxide | wt% | Phase | wt% | Phase | wt% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | 61.79 | SO3 | 2.84 | Alite (C3S) | 54.45 | Gypsum | 4.82 |

| SiO2 | 21.14 | K2O | 0.77 | Belite (C2S) | 18.07 | Calcite | 4.08 |

| Al2O3 | 5.53 | Na2O | 0.21 | C3Acubic | 3.28 | Quartz | 0.42 |

| Fe2O3 | 2.27 | TiO2 | 0.32 | C3Aorth. | 7.55 | Periclase | 0.75 |

| MgO | 1.39 | P2O5 | 0.14 | C4AF | 5.17 | Other phase | 1.41 |

![Figure 1

Chemical structure of poly(acrylamide-co-[Na] acrylate).](/document/doi/10.1515/arh-2025-0037/asset/graphic/j_arh-2025-0037_fig_001.jpg)

Chemical structure of poly(acrylamide-co-[Na] acrylate).

The water/cement ratio of samples was kept at 0.36. Samples were prepared using deionized water and mixed with a vertical mixer (Kitchen Aid, Type 5K45, Benton Harbor, MI, USA). The mix proportion of the pastes is shown in Table 2. The mixing protocol is as follows: Aqueous solution containing different admixtures was prepared by adding 30 wt% of the total water, homogenized with a glass rod, and mixed for 5 min. The other 70 wt% of the total water was introduced into the cement in the mixer. With the mixer, the paste was mixed at level 1 (58 rpm) for 60 s, and then the edges of the bowl of cement paste were scraped for 30 s. After that, the paste was mixed again at level 3 (103 rpm) for 60 s. The pre-prepared aqueous solution containing different admixtures was added to the cement paste, and then the sample was mixed at level 3 (103 rpm) for 60 s. The preparation and related experiments were conducted in an air-conditioned laboratory at 20 ± 1°C.

Mix design of the studied cement paste

| No. | Specimen | PAM (wt%) | CaCl2 (wt%) | TEA (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | REF | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | P48 | 0.048 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | P0-C1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | P48-C1 | 0.048 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | P0-C2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | P48-C2 | 0.048 | 2 | 0 |

| 7 | P0-T15 | 0 | 0 | 0.15 |

| 8 | P48-T15 | 0.048 | 0 | 0.15 |

| 9 | P0-T25 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 |

| 10 | P48-T25 | 0.048 | 0 | 0.25 |

2.2 Experiments

2.2.1 Slow penetrating sphere (SPS) test

The SPS test was performed using the Toni SET Force (ToniTechnik GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The instrument has been described and validated for SPS experiments in previous studies [7,8]. In this study, samples were prepared through the procedure described in Section 2.1 and poured into a cylindrical plastic container (radius 30 mm, height 80 mm) for continuous measurement. The cement on the surface of the containers was leveled using a scraper, and an anti-evaporation device was placed on top of the sample containers during the measurements. The sphere descent speed was fixed at 0.05 mm/min. The measurement was stopped when the measurement time reached 5 h, or the force reached 400 N. Based on the equation from the study of Lootens et al. [9], the static yield stress can be calculated as follows:

where R (=7.5 mm) is the sphere radius, F is the penetration force, and τ is the static yield stress as a function of time.

2.2.2 Setting time with the Vicat needle penetration

The setting time of samples was measured using an automatic Vicat needle device ToniSET Compact (Toni Technik Baustoffprüfsysteme GmbH, Berlin, Germany). According to EN 196-3 [24], the initial setting (IS) time is defined as the time when the needle penetration depth reaches 34 mm, while the final setting (FS) time is defined as the time when the needle penetration depth reaches 0.5 mm.

2.2.3 XRD

XRD experiments were performed using the XRD EMPYREAN (Malvern Panalytical Ltd, UK) on powder samples for 1 h. The steps to obtaining the required sample powders for the experiment are as follows: After 1 h of hydration, isopropanol was added to the sample and stirred for 5 min. After decanting the isopropanol, the sample was placed in an oven at 40°C to dry to a constant weight. Then, the dried samples were manually ground to powder for measurements.

2.2.4 TGA

TGA was performed using the TG209 F3 Tarsus (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Sleb, Germany). Samples were the same powder used in the XRD experiments. Approx. 10 mg of the powder was tested in a nitrogen atmosphere from 25 to 850°C with a heating rate of 10°C/min.

2.2.5 Isothermal calorimetric test

Isothermal calorimetric tests were performed using a TAM Air calorimeter (TA Instruments, New Castle, PA, USA) to record the heat flow of the cement paste for 72 h. Since the calorimetry was not equilibrated and mixed in the calorimeter, measurements of samples initially hydrated for 1 h were not considered for calculating the cumulative heat.

2.2.6 Ultrasonic P-wave velocity measurement

Ultrasonic P-wave velocity measurements were performed using the Ultrasonic Measuring Test System IP-8 (UltraTest GmbH, Achim, Germany). This equipment measures the velocity of ultrasonic P-waves through a 40 mm cement paste. The ultrasonic velocity was measured every 60 s during 24 h of cement hydration in an air-conditioned laboratory at 20 ± 1°C.

2.2.7 Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) experiment

The concentration of various elements, including [K], [Na], [Ca], [S], [Fe], [Al], and [Si], of the pore solution at a hydration time of 15 min was detected by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, IRIS Intrepid II XSP, Thermo Fisher, USA). At 15 min of hydration, fresh cement paste was first placed into the centrifugation tubes and then immediately centrifuged at about 3,317 g for 15 min. The supernatant solution was collected by using a syringe filter with a pore diameter of 0.45 μm. The filtered pore solution was immediately diluted three times by mass with 1.0 wt% nitric acid (HNO3) and kept sealed in ampoules.

3 Results

3.1 Evolution of static yield stress

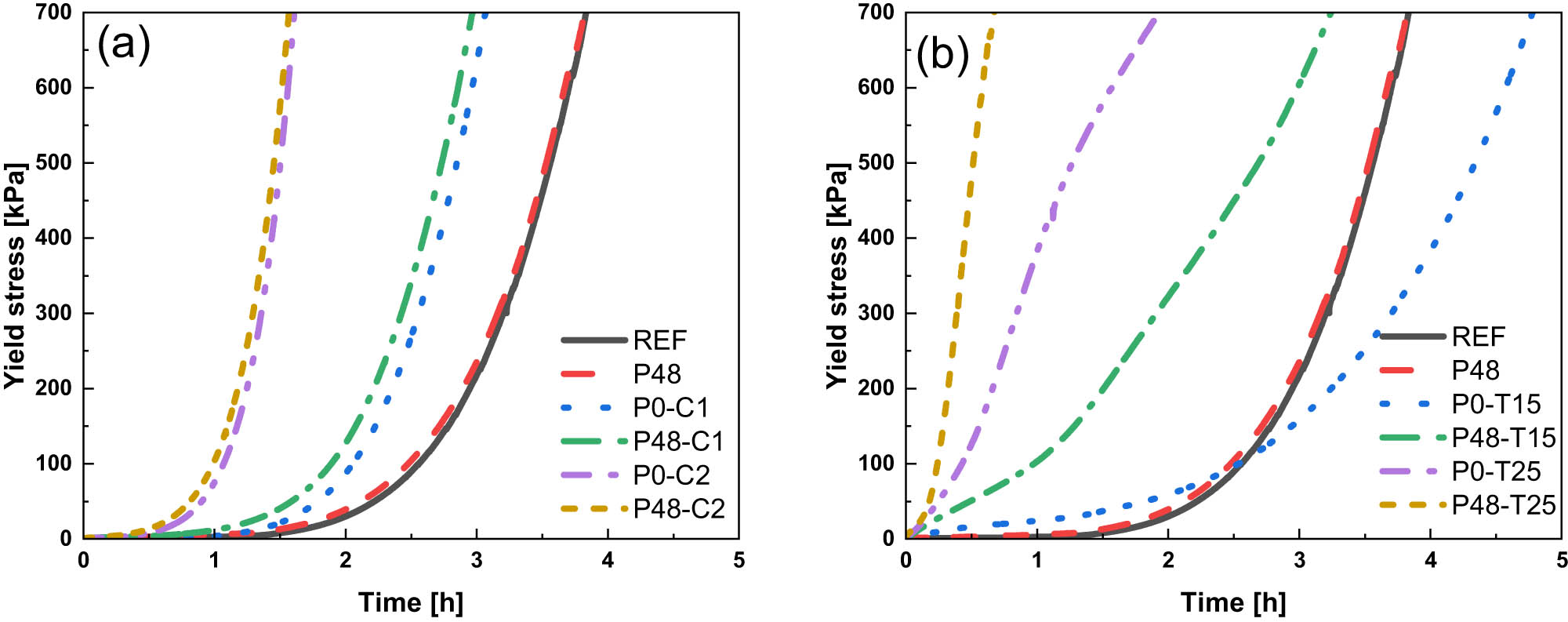

The evolution of static yield stress in early cement hydration, as determined by the SPS test, is shown in Figure 2. When used individually, 1.0 wt% CaCl2, 2.0 wt% CaCl2, 0.15 wt% TEA, 0.25 wt% TEA, and 0.048 wt% PAM accelerate the increase in the static yield stress of cement, as described, respectively, in the literature related to TEA [25,26], CaCl2 [27,28,29], and PAM [19].

Static yield stress of samples with different admixtures in the early stage of cement hydration: (a) PAM and CaCl2 and (b) PAM and TEA.

As shown in Figure 2a, the yield stress of the sample with PAM increases marginally faster than the reference sample, and at approx. 4 h, when the yield stress of P48 reaches around 700 kPa, it is nearly the same as that of REF. CaCl2 addition has an obvious acceleration on yield stress, specifically by reducing the time required to reach 700 kPa. Compared to the REF sample, using 1.0 wt% CaCl2 reduces the time from about 4 to 3 h, while 2.0 wt% CaCl2 (P0-C2) reduces it to about 1.5 h. The combined use of CaCl2 and PAM exhibits a slightly enhanced acceleration effect than the individual use of CaCl2 in both cases of 1.0 and 2.0 wt%. The time required for PAM with 2.0 wt% CaCl2 (P48-C2) to reach 700 kPa is almost the same as that for P0-C2.

Figure 2b shows that both 0.15 and 0.25 wt% TEA can accelerate the increase in static yield stress in the very early stage (within approx. 2 h). After about 2.5 h of hydration, the increase in static yield stress for using 0.15 wt% TEA sample slows down and falls below that of REF. Unlike the sample with PAM and CaCl2, the combined use of PAM and TEA significantly accelerates the static yield stress. The time to reach 700 kPa is reduced by over 1 h when PAM and TEA are combined. Additionally, it can be found that the static yield stress for samples containing 0.25 wt% TEA increases steeply first and then slows down, which differs from the exponential increase observed in other samples.

3.2 Setting times

The initial and FS times of the cement samples are shown in Figure 3. It can be observed that the use of PAM and accelerators (CaCl2 and TEA) leads to a decrease in the setting time. With the increased dosage of CaCl2 and TEA, the initial and FSs decrease, and the most dramatic decrease is observed when 0.25 wt% TEA was used, indicating a rapid set of cement, similar to previous studies [25,26].

IS and FS time of samples with different admixtures.

The IS time of samples containing CaCl2 and PAM (e.g., P48-C1) or TEA and PAM (e.g., P48-T15) decreases more than that of samples with the corresponding dosage of corresponding admixture added individually (e.g., P0-C1 or P0-T15), which indicates that the combined use of these two types of accelerators and PAM has a better set accelerating effect. It is also clear that the set accelerating effect of the combination of PAM and TEA is better than that of the combination of PAM and CaCl2. Compared to P0-T15, the IS time of P48-T15 decreased by 44%. Similarly, P48-T25 decreased by 31% compared to P0-T25, P48-C1 decreased by 13% compared to P0-C1, and P48-C2 decreased by 11% compared to P0-C2.

3.3 Heat of hydration

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the heat flow and cumulative heat of hydration, measured over the first 24 h of hydration. It is generally accepted that the first peak of the calorimetric curve, occurring within the first hour, is due to the initial dissolution of clinker phases and the initial chemical reactions [30,31]. The second peak results from the main hydration of C3S and is considered the main exothermic peak during the early hydration of cement. The shoulder peak of the second peak is associated with the sulfate depletion point caused by reactions between C3A and AFt [29,30]. The calorimetric curve of REF is consistent with that of typical OPC, showing a noticeable second peak (main peak) and its shoulder peak.

Calorimetric curves of cement pastes containing different admixtures during 24 h. Heat flow (a) and cumulative heat (b) of samples with PAM and CaCl2, and heat flow (c) and cumulative heat (d) of samples with PAM and TEA.

Figure 4a shows that the heat flow curve of the sample containing only 0.048 wt% of PAM (P48) is similar to that of REF, and the 0.048 wt% PAM slightly extends the induction period of cement hydration and delays the second peak before 10 h. From the curve of cumulative heat, it can be observed that using 0.048 wt% PAM slightly reduced the heat released from cement. The curves for samples containing 1.0 wt% (P0-C1) and 2.0 wt% (P0-C2) CaCl2 show a significant shift in the appearance of the main peak, occurring earlier at approx. 6 h for P0-C1 and 4 h for P0-C2, compared to 10 h for REF. For samples containing 0.048 wt% PAM and CaCl2 (P48-C1), the calorimetric curve is generally identical to P0-C1. In the zoom-in graph of Figure 4a, the PAM used in this study slightly reduced the heat flow within the hydration time of 4 h in both cases of 1.0 and 2.0 wt%.

For samples containing only 0.15 wt% TEA (P0-T15), the shape of the calorimetric curves for P0-T15 is similar to REF, featuring a second exothermic peak. However, the shoulder peak of the second peak is missing, and the heat flow at the minimum heat flow point is higher than REF. On the other hand, the calorimetric curve of P0-T25 differs from REF, showing multiple peaks within the first 24 h of hydration, occurring at approx. 2, 6, and 21 h.

In Figure 4b and d, for the sample containing 0.048 wt% of PAM and 0.15 wt% of TEA (P48-T15), its calorimetric curve is similar to P0-T15. After the end of the induction period, the heat flow of P48-T15 is significantly lower than P0-T15, suggesting PAM reduces heat released from cement hydration in the presence of TEA. For the sample containing 0.048 wt% PAM and 0.25 wt% TEA (P48-T25), the exothermic peak around 2 h in P0-T25 is absent in P48-T25, and during the first 4 h hydration, the heat flow of P48-T25 is significantly higher than other samples. In addition, the heat flow peak around 6 h observed in P0-T25 is also present in P48-T25 but with a substantially lower value. Unlike the third exothermic peak in the calorimetric curve of P0-T25 within 24 h, no such peak is observed in P48-T25.

All these observations suggest that the combined use of CaCl2 and low-dosage PAM does not effectively promote early cement hydration, while the combined use of TEA and low-dosage PAM changes the early hydration process of cement. Notably, if the TEA dosage is relatively high, significant changes in the very early hydration process of cement may occur.

3.4 Ultrasonic velocity

Figure 5 shows the evolution of ultrasonic P-wave velocity (hereafter referred to as “velocity”) during the first 24 h of cement hydration. The velocity related to PAM and CaCl2 is shown in Figure 5a, and the velocity associated with PAM and TEA is shown in Figure 5b. All P-wave velocities increased immediately after the onset of the measurements. However, the subsequent evolutions were not all the same.

Evolution of the ultrasonic P-wave velocity of cement pastes with (a) PAM and CaCl2 and (b) PAM and TEA.

The velocity profiles during hydration for different cement samples show varied patterns depending on their composition. For REF and samples containing 0.048 wt% of PAM (P48), velocities were generally lower than REF throughout the initial 24 h of hydration. Both REF and P48 demonstrated a decrease in velocity after about 30 min.

In samples with 1.0 wt% of CaCl2 (P0-C1), velocity trends were akin to REF and P48, showing a decline, but P0-C1 maintained higher velocities than both REF and P48 throughout, especially before 45 min of hydration. In contrast, samples with both 0.048 wt% PAM and varying concentrations of CaCl2 did not exhibit this initial decrease but displayed a phased velocity increase: an initial slow increase within 1 h, followed by a rapid rise, and then another slow rise. Notably, P0-C2 initially showed lower velocities than P48-C2 but surpassed it between 1 and 2 h, only to fall below again thereafter.

Samples containing TEA, with or without PAM, exhibited a distinct rapid velocity increase in the early hydration stages. For instance, P0-T15 and P0-T25 showed multiple phases of rapid and slow velocity increases. In the first 2 h, P0-T15 had lower velocities than P0-T25 but subsequently maintained higher rates. Similarly, the velocities of P48-T15 and P48-T25 surged but then transitioned into slower increase phases after about 30 and 90 min of hydration, respectively. Differences were also observed in the relative velocities between samples with TEA, highlighting varied hydration kinetics based on their chemical additives.

3.5 TGA

Figure 6 illustrates the TGA and differential thermogravimetric results for cement samples containing various admixtures hydrated for 1 and 2 h. The identification of the thermal decomposition temperature of hydration products was based on previous studies [32,33,34]. The results highlight distinct thermal decomposition behaviors influenced by admixture type and hydration duration. For samples with calcium chloride (CaCl2) and PAM, there is a notable shift in the thermal mass loss peaks as hydration progresses. In the first 1 h, we observe peaks corresponding to the dehydration of hydration products such as Ettringite/AFt, Friedel’s salt/Fs, portlandite/CH, and gypsum at specific temperatures. These temperatures shift slightly in the samples at 2 h, when the dehydration range for calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) becomes apparent. These observations underscore the dynamic chemical transformations occurring within these cement systems.

Thermogravimetric mass loss of samples with different admixtures at 1 and 2 h of hydration. Subfigures (a) and (b) correspond to mixtures with PAM and CaCl2, while (c) and (d) show the results for mixtures with PAM and TEA.

The thermal decomposition of TEA-containing samples, as depicted in Figure 6c and d, indicates a rapid dehydration of ettringite (AFt) and a slower reaction rate for aluminate ferrite monosulfate (AFm). This suggests that TEA significantly influences early-stage hydration reactions, particularly enhancing the formation of AFt. Interestingly, the presence of TEA also appears to retard the hydration of the silicate phase, a finding consistent with previous studies [25,26], as evidenced by the slightly low intensity and stable CH content across the hydration period. This retardation might be attributed to TEA’s interaction with calcium ions, which are crucial for the hydration process.

The TGA data specifically highlight the interactions between PAM and chemical accelerators like CaCl2 and TEA on the hydration kinetics of cement. The presence of PAM appears to modify the hydration behavior significantly when used in conjunction with these accelerators. In CaCl2-containing samples, the interaction between PAM and CaCl2 leads to pronounced variations in the hydration process, evident from shifting thermal mass loss peaks over time, indicating accelerated reactions in the aluminate and silicate phases. Similarly, in the TEA-enhanced samples, PAM seems to stabilize the hydration reactions, as evidenced by the consistently low intensity of CH peaks despite the overall accelerated formation of AFt. This suggests a nuanced role of PAM in moderating the effects of accelerators on cement hydration kinetics.

3.6 XRD

Figure 7 shows the XRD patterns of cement samples containing different admixtures. The identification of different solid phases, including clinkers and hydration products, was based on PDF-2 [35] and literature [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. The peak intensities corresponding to the individual solid phases after the addition of admixtures varied after 1 and 2 h of cement hydration. Calcite is not considered here due to the overlap of its characteristic peaks with C3S and C2S. In addition, the presence of Friedel’s salt (Fs, 3CaO·Al2O3·CaCl2·10H2O) is detected in the CaCl2-containing samples and monosulfoaluminate with 12 moles of water (Ms12) is detected in the TEA-containing samples, as shown in Figure 8 (a zoom-in graph from Figure 7), where P0-C2 and P0-T25 stand for the CaCl2-containing samples and the TEA-containing samples, respectively. The other AFm phases, as well as hydrogarnet (C3AH6), are not detected.

XRD patterns of samples with different admixtures: (a) samples with PAM and CaCl2 hydrated for 1 h, (b) samples with PAM and CaCl2 hydrated for 2 h, (c) samples with PAM and TEA hydrated for 1 h, and (d) samples with PAM and TEA hydrated for 2 h.

Zoom-in graph on XRD patterns of samples with PAM and TEA hydrated for 1 and 2 h.

The analysis of XRD data, presented in Figures 7 and 8, delves into the effects of PAM when combined with accelerators such as CaCl2 and TEA on the hydration phases of cement. The presence of PAM distinctly alters the hydration dynamics by affecting the intensities of the sulfate and aluminate phases, suggesting changes in their solubility and reaction kinetics.

In the case of samples containing both CaCl2 and PAM, there is a noticeable modification in the hydration product phases within the first hour of hydration. The intensity of the sulfate phases (i.e., CaSO4·2H2O) decreases in the presence of PAM, indicating that PAM modifies the availability of sulfate ions necessary for phase formation. In addition, the presence of PAM may reduce sulfate diffusion. Thus, the retardation of the aluminate phase is not as pronounced as it is with readily available sulfate. Concurrently, the aluminate phase reacts more promptly, indicating PAM’s role in accelerating this specific phase without significantly impacting the silicate phase, as evidenced by the stable CH phase intensity.

At the hydration time of 2 h, as indicated in Figure 7b, the influence of CaCl2 predominates, overshadowing the effects of PAM. The diminished CH content in samples containing both CaCl2 and PAM, compared to those with CaCl2 alone, may reflect PAM’s influence on the crystallization and aggregation processes of CH. This underscores the complex role of chemical admixtures in shaping the kinetics of cement hydration. In samples containing TEA and PAM, the subtle enhancements in the intensities of AFt and Ms12 indicate a stabilizing effect of PAM on these phases. Despite this, the CH phase remains largely unaffected over time. The interplay between TEA and PAM illustrates a nuanced impact on cement chemistry, emphasizing the subtle yet significant changes in crystallization orientation and phase intensity relationships due to the admixtures.

3.7 ICP-OES

To determine the ion composition of pore solutions, samples containing 1.0 wt% CaCl2 and 0.15 wt% TEA, with or without PAM, were mainly considered. In our experiment, the use of 0.25 wt% TEA and 2.0 wt% CaCl2 led to the rapid setting of cement, making it difficult to obtain enough pore solution through the centrifugal device. The elemental composition of the pore solutions of cement samples hydrated for 15 min, including the background for each element from the ICP device, is shown in Table 3.

Composition of the cement pore solutions from samples with different admixtures

| Sample | K (mmol/L) | Na (mmol/L) | Ca (mmol/L) | S (mmol/L) | Al (mmol/L) | Fe (mmol/L) | Si (mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.0007 | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | 0.00001 | 0.0003 |

| REF | 323 | 49.9 | 23.0 | 149.3 | 0.547 | 0.201 | 2.251 |

| P48 | 348 | 54.4 | 12.4 | 161.6 | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.037 |

| P0-C1 | 342 | 52.2 | 85.3 | 22.2 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.012 |

| P48-C1 | 341 | 53.5 | 81.5 | 21.1 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.021 |

| P0-T15 | 373 | 60.4 | 14.3 | 163.4 | 0.093 | 1.465 | 0.337 |

| P48-T15 | 365 | 61.4 | 13.5 | 174.1 | 0.277 | 2.011 | 1.073 |

The study evaluates the impact of PAM when combined with CaCl2 and TEA on the elemental concentration changes during the initial hydration phases of cement. Initial findings indicate that alkali elements [K] and [Na] remain relatively unaffected by these admixtures, maintaining high dissolution rates. In contrast, the concentrations of [Ca], [S], [Al], [Fe], and [Si] exhibit significant changes, reflecting the complex interactions between these admixtures and the cement matrix. Notably, the addition of 0.048 wt% PAM slightly increases [S] concentration while decreasing [Ca], [Al], [Fe], and [Si], suggesting a nuanced effect of PAM on the hydration environment.

Adding 1.0 wt% CaCl2 predominantly increases [Ca] levels, demonstrating its expected influence on enhancing calcium availability in the system, which is crucial for the formation of calcium hydroxide and other calcium-rich hydration products. However, this addition also leads to a decrease in [S], [Al], [Fe], and [Si], highlighting CaCl2’s role in potentially driving these elements into less soluble phases or complexes. When both 0.048 wt% PAM and 1.0 wt% CaCl2 are used, the interaction modifies the concentrations of [Ca] and [S] slightly, while [Al], [Fe], and [Si] exhibit a relative increase compared to samples with only CaCl2, indicating a shift in the dissolution and precipitation dynamics influenced by PAM.

The introduction of 0.15 wt% TEA affects the elemental dynamics differently: it slightly increases [S] and [Fe] while reducing [Ca], [Al], and [Si], suggesting TEA’s influence on promoting the hydration of certain phases at the expense of others. The combination of TEA and PAM further alters these dynamics, reducing [Ca] concentration and increasing [S], [Al], [Fe], and [Si] compared to the addition of TEA alone. This pattern implies a synergistic effect of PAM and TEA on the dissolution and reaction processes within the cement matrix, affecting the availability and reactivity of these key elements.

Overall, the study illustrates the complex interplay between PAM, CaCl2, and TEA in the early hydration phases of cement, highlighting how these admixtures can selectively enhance or inhibit the dissolution of specific elemental constituents. The interactions between PAM and these accelerators not only modify the elemental concentrations but also suggest alterations in the microstructure and phase development of the hydrating cement, potentially leading to varied physical properties in the resulting material. This nuanced understanding of admixture interactions provides valuable insights into optimizing cement formulations for enhanced performance characteristics.

4 Discussion

The discussion of the above experimental results is divided into the following three parts. First, the evolution of static yield stress of cement paste is analyzed based on the formation of hydration products with ultrasonic experiments and hardening experiments. Then, the effect of admixtures on the dissolution of the clinker phase of the cement, as well as on the formation of hydration products in the very early stages of hydration, is discussed based on the heat of hydration/TG/XRD results. Finally, the effect of admixtures on the static yield stress of cement during the very early stage of hydration is discussed through pore solution data obtained from the ICP experiment.

4.1 Interrelationship between the measured rheological properties

Figure 9 illustrates the effect of PAM and the accelerators CaCl2 and TEA on the IS times of cement paste. When these admixtures are introduced individually, a reduction in the IS time is observed, indicating their influence on accelerating cement setting and hardening. The Vicat needle penetration test reveals this acceleration effect; however, due to the differing dimensions and pressures applied by the testing apparatus (a thin stick versus a larger ball in the SPS test), the data may not perfectly represent the static yield stress evolution across different admixture compositions. Despite these experimental discrepancies, the early-stage hydration aligns with increases in static yield stress observed within about 2.5 h of hydration.

Comparison between SPS, setting time (shown as a triangle), and ultrasonic velocity: (a) PAM and CaCl2 and (b) PAM and TEA.

The ultrasonic P-wave velocity measurements further demonstrate the impact of hydration products on the physical properties of the cement matrix. For some samples, such as REF, P48, and P0-C1, a decrease in ultrasonic velocity before the 2-h mark is noted, attributed to the increased tortuosity in the pore space due to insufficient hydration product quantities to fully connect cement particles [44,45,46]. As hydration progresses, the velocity increases, reflecting the consumption of water, the continued accumulation of hydration products, and the eventual hardening of the cement paste [44,45], which collectively contribute to the evolving static yield stress of the cement.

The introduction of PAM notably decreases the IS time across all samples, with corresponding ultrasonic P-wave velocities being lower in PAM-containing samples in a certain period of time compared to those without PAM (e.g., P48 < REF, P48-C1 < P0-C1). This suggests that the increased static yield stress in samples with both TEA and PAM or CaCl2 and PAM is not solely due to the precipitation of the hydration product. Early hydration stages show PAM’s bridging effect significantly enhances static yield stress, surpassing the impact of hydration product formation alone. Notably, TEA accelerates aluminate phase dissolution and hydration, promoting PAM’s cross-linking and bridging – a unique interaction not observed with CaCl2, demonstrating the specific roles and synergies between PAM and these chemical accelerators in cement hydration.

4.2 Relationship between the hydration process and static yield stress

PAM with a dosage of 0.048 wt% slightly extended the cement induction period and retarded cement hydration, as evidenced by isothermal calorimetry (Figure 3a and b). The heat flow from PAM-modified samples (P48) was initially higher than the reference (REF) until reaching the lowest heat flow point, after which it dropped below REF, indicating a delayed main hydration stage of C3S. This effect of PAM was corroborated by XRD and TG experiments, which showed a decrease in AFt content and no change in CH content compared to REF, suggesting PAM’s inhibition of chemical hydration.

In contrast, adding CaCl2 significantly reduced the induction period and enhanced the heat flow during the acceleration period (Figure 3a and b). XRD results highlighted increased CH content despite lower initial AFt intensity than samples without CaCl2, indicating a dynamic shift in hydration phases. The TG data supported these findings, showing increased C–S–H, CH, and Fs contents in CaCl2-enriched samples, affirming that the hydration of C3S and the transformation from AFt to Fs are pivotal in the early static yield stress increase.

Samples containing only TEA showed unique hydration behaviors, with significant early exothermic calorimetry peaks, reflecting accelerated aluminate phase reactions (Figure 3c). XRD and TGA confirmed higher AFt content and consistent CH content across hydration stages. The increased AFt content and stable Ms12 intensity suggest that TEA predominantly promotes early aluminate phase reactions, leading to a distinct hydration profile compared to other admixtures.

The interaction between PAM and the accelerators reveals complex hydration dynamics. When PAM is combined with CaCl2, it moderates the effects of CaCl2, slightly extending the induction period and altering the hydration process, as shown by the comparative analysis of AFt and Fs contents via XRD and TG. The results imply that while PAM may delay some reactions, it does not significantly hinder the hydration promoted by CaCl2, highlighting the nuanced role of PAM in cement chemistry. Similarly, the combination of TEA and PAM modifies the hydration timeline and dynamics, with PAM enhancing the effects of TEA on the hydration process. Despite a higher AFt content observed with lower TEA dosages, increasing TEA concentration changes the hydration sequence, evidenced by the differing hydration peaks and product formation in calorimetry and TG results. This suggests that while PAM and TEA together increase the complexity of the hydration process, their impact on static yield stress is nuanced, reflecting the intricate interplay of chemical interactions and admixture effects on cement properties.

4.3 Influencing mechanism of the combined use of PAM and accelerators

Based on pore solution analyses of cement paste conducted for samples, schematic drawings of dissolution and hydration in a very early stage of hydration are shown in Figure 10 for a better understanding of the effects of single or combined use of PAM and accelerators on the dissolution of clinker phases and precipitation of hydration products at the very early stage of hydration.

Schematic drawings of dissolution and hydration in a very early stage of hydration. (a) REF, (b) P0-C1, (c) P0-T15, (d) P48, (e) P48-C1, and (f) P48-T15.

Figure 10 illustrates the early stages of clinker hydration, showing the release of various cations. Compared to REF (Figure 10a), the addition of calcium chloride delays the release of aluminum and iron ions (Figure 10b), while TEA actually enhances their release (Figure 10c) (promoted release of aluminum ions is converted into the earlier precipitation of AFt based on XRD and TGA). When PAM is added, cation release is initially inhibited (Figure 10d). However, this effect is weakened by the simultaneous presence of calcium chloride, slightly increasing cation release (Figure 10e). The combined addition of PAM and TEA markedly promotes this process, leading to increased adsorption of PAM on clinkers and complexation with iron ions, correlating with a significant rise in static yield stress observed in SPS tests (Figure 10f).

Specifically, CaCl2 and PAM are added simultaneously, and PAM is adsorbed onto the surface of the particles. Due to its complexation and cross-linking with calcium ions [10], PAM facilitates the connection between cement particles, albeit with a comparatively fixed and not very attractive inter-particle force. The complexation and cross-linking with calcium ions induced by CaCl2 also diminish the retarding effect of PAM on cement hydration, potentially blocking the smooth diffusion of water and ions, thereby inhibiting the precipitation of hydration products [10,18,19]. This effect is observed in the TGA and XRD results for samples with CaCl2 and PAM at 1 and 2 h of hydration, where the 1-h samples show higher hydration product content than those containing only CaCl2, but this advantage disappears in the 2-h samples.

The interaction between PAM and calcium ions from CaCl2 imparts an attractive inter-particle force not found in samples with only CaCl2, resulting in consistently higher static yield stress in the CaCl2 and PAM samples at the very early stages of hydration (Figure 2a). This interplay is depicted in Figure 10e. Furthermore, when higher dosages of CaCl2 and PAM are used together, the complexation with PAM is relatively diminished due to the earlier hydration of C3S and the resulting higher content of C–S–H and CH, suggesting a reduced impact of PAM on static yield stress as the CaCl2 dosage increases.

TEA reacts preferentially with C4AF, not C3A [26], but also accelerates the dissolution and reaction of C3A while inhibiting the major hydration of C3S [47,48], indicating a reaction preference of Fe > Al > Ca for TEA. This affects the release of calcium ions from the cement particle surface, as Al and Fe may still interact with TEA. PAM, attracted to the higher concentration of calcium ions, is adsorbed onto the cement particle surfaces, influencing TEA’s reaction with C4AF and facilitating the release of more aluminum and iron ions into the pore solution. With an increased presence of ions (i.e., Fe and Al), the bridging effect of PAM is enhanced, along with the slightly increased precipitation of Aft. This may contribute to a faster increase in static yield stress from the onset of hydration, as observed in the SPS test. The results underscore the complex interplay between PAM and TEA in modifying cement hydration dynamics, which could inform the intelligent design of 3D printing concrete or shotcrete in practical engineering with reduced CO2 emissions.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the effects of combining PAM with the accelerators calcium chloride (CaCl2) and TEA on the static yield stress of cement paste during its early hydration stages. We employed a variety of methods, including the SPS test, Vicat needle penetration, ultrasonic P-wave velocity measurements, calorimetric tests, TGA, XRD, and ICP experiments. The findings from these diverse methodologies led to the following conclusions:

CaCl2 enhances early C3S hydration, promoting C–S–H and CH formation and the conversion of AFt to Friedel’s salt. PAM, while retarding the peak hydration of C3S by affecting AFt and its conversion, does not detract from the overall positive impact of CaCl2 on C3S hydration, as evidenced by calorimetric tests, XRD, and TGA.

Initially, CaCl2 inhibits the release of Al, Fe, and Si ions, but PAM offsets this effect, likely through complexation with calcium ions derived from CaCl2. This interaction promotes further precipitation of AFt and Friedel’s salt, contributing to early hydration and increased static yield stress via PAM’s bridging effect, as demonstrated by ICP and XRD findings.

TEA significantly enhances the dissolution and hydration of C4AF, leading to increased AFt precipitation. Higher TEA dosages (0.25 wt%) substantially alter early cement hydration dynamics by delaying C3S hydration. The formation of Ms12 alongside AFt contributes to increased static yield stress, as confirmed by calorimetric testing and XRD.

PAM synergistically enhances the initial clinker phase dissolution promoted by TEA, contributing substantially to the increase in static yield stress. This synergy involves TEA-driven cation release, which attracts PAM to the cement particles, enhancing cross-linking reactions facilitated by cations (i.e., iron ions) and promoting the concurrent precipitation of hydration products, as shown in ICP and TG experiments.

These results show how PAM, when used with common accelerators like CaCl2 and TEA, greatly influences how cement hydrates and its strength. The interaction between PAM and the ions affected by TEA particularly highlights the potential for creating dual accelerators that can both dissolve clinker faster and improve cement strength. Designing these mixtures requires careful consideration of how each component impacts cement hydration and final strength to achieve the desired outcomes. For future study, further research into the synergistic effects of these chemical admixtures could lead to more efficient and sustainable cement formulations, enhancing the performance and durability of concrete in construction.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin. Financial support for this study was provided by the German Research Foundation (DFG), which funded the Priority Program DFG SPP 2005, “Opus Fluidum Futurum – Rheology of Reactive, Multi-Scale, Multiphase Construction Materials” (project number 387092747), and the project “Tailored Yield Stress for 3D Printing Using Low Clinker Cement” (project number 386869775). We want to thank Jessica Conrad at Technische Universität Berlin for conducting the ICP experiments essential to this research.

-

Funding information: Financial support for this study was provided by the German Research Foundation (DFG), which funded the Priority Program DFG SPP 2005, “Opus Fluidum Futurum – Rheology of Reactive, Multi-Scale, Multiphase Construction Materials” (project number 387092747), and the project “Tailored Yield Stress for 3D Printing Using Low Clinker Cement” (project number 386869775).

-

Author contributions: Yanliang Ji: conceptualization, writing, supervision, funding, methodology, simulation and calculation, measurement, reviewing, and editing. Yujiong Cen: writing, measurement, reviewing, and editing. Dietmar Stephan: supervision, funding, writing, reviewing, and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: Data will be made available on request.

References

[1] Hirsch T, Matschei T, Stephan D. The hydration of tricalcium aluminate (Ca3Al2O6) in Portland cement-related systems: A review. Cem Concr Res. 2023;168:107150.10.1016/j.cemconres.2023.107150Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zhang Z, Scherer GW, Bauer A. Morphology of cementitious material during early hydration. Cem Concr Res. 2018;107:85–100.10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.02.004Search in Google Scholar

[3] Aranda* MAG, De la Torre AG, Leon-Reina L. Rietveld quantitative phase analysis of OPC clinkers, cements and hydration products. Rev Miner Geochem. 2012;74(1):169–209.10.2138/rmg.2012.74.5Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wang L, Zhang P, Golewski G, Guan J. Fabrication and properties of concrete containing industrial waste. Front Mater. 2023;10:1169715.10.3389/fmats.2023.1169715Search in Google Scholar

[5] Golewski GL. Examination of water absorption of low volume fly ash concrete (LVFAC) under water immersion conditions. Mater Res Express. 2023;10(8):085505.10.1088/2053-1591/acedefSearch in Google Scholar

[6] Ji Y, Sun Z, Chen C, Pel L, Barakat A. Setting characteristics, mechanical properties and microstructure of cement pastes containing accelerators mixed with superabsorbent polymers (SAPs): an NMR study combined with additional methods. Materials. 2019;12(2):315.10.3390/ma12020315Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Pott U, Stephan D. Penetration test as a fast method to determine yield stress and structural build-up for 3D printing of cementitious materials. Cem Concr Compos. 2021;121:104066.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104066Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ji Y, Pott U, Mezhov A, Rößler C, Stephan D. Modelling and experimental study on static yield stress evolution and structural build-up of cement paste in early stage of cement hydration. Cem Concr Res. 2025;187:107710.10.1016/j.cemconres.2024.107710Search in Google Scholar

[9] Lootens D, Jousset P, Martinie L, Roussel N, Flatt RJ. Yield stress during setting of cement pastes from penetration tests. Cem Concr Res. 2009;39(5):401–8.10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.01.012Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bessaies-Bey H, Baumann R, Schmitz M, Radler M, Roussel N. Effect of polyacrylamide on rheology of fresh cement pastes. Cem Concr Res. 2015;76:98–106.10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.05.012Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhao D, Williams JM, Park AHA, Kawashima S. Rheology of cement pastes with calcium carbonate polymorphs. Cem Concr Res. 2023;172:107214.10.1016/j.cemconres.2023.107214Search in Google Scholar

[12] Huang H, Ruckenstein E. The bridging force between colloidal particles in a polyelectrolyte solution. Langmuir. 2012;28(47):16300–5.10.1021/la303918pSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Ghio VA, Monteiro PJM, Demsetz LA. The rheology of fresh cement paste containing polysaccharide gums. Cem Concr Res. 1994;24(2):243–9.10.1016/0008-8846(94)90049-3Search in Google Scholar

[14] Adjou N, Yahia A, Oudjit MN, Dupuis M. Influence of HRWR molecular weight and polydispersity on rheology and compressive strength of high-performance cement paste. Constr Build Mater. 2022;327:126980.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126980Search in Google Scholar

[15] Schmidt W, Brouwers HJH, Kühne HC, Meng B. Interactions of polysaccharide stabilising agents with early cement hydration without and in the presence of superplasticizers. Constr Build Mater. 2017;139:584–93.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.11.022Search in Google Scholar

[16] Guezennec AG, Michel C, Ozturk S, Togola A, Guzzo J, Desroche N. Microbial aerobic and anaerobic degradation of acrylamide in sludge and water under environmental conditions – case study in a sand and gravel quarry. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(9):6440–51.10.1007/s11356-014-3767-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Xiong B, Loss RD, Shields D, Pawlik T, Hochreiter R, Zydney AL, et al. Polyacrylamide degradation and its implications in environmental systems. NPJ Clean Water. 2018;1(1):17.10.1038/s41545-018-0016-8Search in Google Scholar

[18] Sun Z, Xu Q. Micromechanical analysis of polyacrylamide-modified concrete for improving strengths. Mater Sci Eng: A. 2008 Aug;490(1–2):181–92.10.1016/j.msea.2008.01.026Search in Google Scholar

[19] Yao H, Fan M, Huang T, Yuan Q, Xie Z, Chen Z, et al. Retardation and bridging effect of anionic polyacrylamide in cement paste and its relationship with early properties. Constr Build Mater. 2021;306:124822.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124822Search in Google Scholar

[20] Yuan Q, Zhou D, Huang H, Peng J, Yao H. Structural build-up, hydration and strength development of cement-based materials with accelerators. Constr Build Mater. 2020;259:119775.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119775Search in Google Scholar

[21] Leinitz S, Lu Z, Becker S, Stephan D, von Klitzing R, Schmidt W. Influence of different accelerators on the rheology and early hydration of cement paste. In Rheology and Processing of Construction Materials: RheoCon2 & SCC9 2; 2020. p. 106–15.10.1007/978-3-030-22566-7_13Search in Google Scholar

[22] Pott U, Jakob C, Dorn T, Stephan D. Investigation of a shotcrete accelerator for targeted control of material properties for 3D concrete printing injection method. Cem Concr Res. 2023;173:107264.10.1016/j.cemconres.2023.107264Search in Google Scholar

[23] Pott U, Crasselt C, Fobbe N, Haist M, Heinemann M, Hellmann S, et al. Characterization data of reference materials used for phase II of the priority program DFG SPP 2005 “Opus Fluidum Futurum – Rheology of reactive, multiscale, multiphase construction materials. Data Brief. 2023;47:108902.10.1016/j.dib.2023.108902Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] EN 196-3:2016. Methods of testing cement. Part 3: determination of setting times and soundness; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Lu Z, Kong X, Jansen D, Zhang C, Wang J, Pang X, et al. Towards a further understanding of cement hydration in the presence of triethanolamine. Cem Concr Res. 2020;132:106041.10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106041Search in Google Scholar

[26] Lu Z, Peng X, Dorn T, Hirsch T, Stephan D. Early performances of cement paste in the presence of triethanolamine: Rheology, setting and microstructural development. J Appl Polym Sci. 2021;138(31):50753.10.1002/app.50753Search in Google Scholar

[27] Rapp P. Effect of calcium chloride on portland cements and concretes. J Res Natl Bur Stand. 1935;14:499.10.6028/jres.014.026Search in Google Scholar

[28] Ramachandran VS. Calcium chloride in concrete – applications and ambiguities. Can J Civ Eng. 1978;5(2):213–21.10.1139/l78-025Search in Google Scholar

[29] Dorn T, Blask O, Stephan D. Acceleration of cement hydration – A review of the working mechanisms, effects on setting time, and compressive strength development of accelerating admixtures. Constr Build Mater. 2022;323:126554.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126554Search in Google Scholar

[30] Pierre-Claude Aïtcin RJF. Science and technology of concrete admixtures. In Chapter 3 Portland cement. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Woodhead Publishing; 2016. p. 27–51.10.1016/B978-0-08-100693-1.00003-5Search in Google Scholar

[31] Xi X, Zheng Y, Zhuo J, Zhang P, Golewski GL, Du C. Mechanical properties and hydration mechanism of nano-silica modified alkali-activated thermally activated recycled cement. J Build Eng. 2024;98:110998.10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110998Search in Google Scholar

[32] Shi Z, Geiker MR, Lothenbach B, De Weerdt K, Garzón SF, Enemark-Rasmussen K, et al. Friedel’s salt profiles from thermogravimetric analysis and thermodynamic modelling of Portland cement-based mortars exposed to sodium chloride solution. Cem Concr Compos. 2017;78:73–83.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[33] Song H, Jeong Y, Bae S, Jun Y, Yoon S, Eun Oh J. A study of thermal decomposition of phases in cementitious systems using HT-XRD and TG. Constr Build Mater. 2018;169:648–61.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.001Search in Google Scholar

[34] Collier NC. Transition and decomposition temperatures of cement phases - a collection of thermal analysis data. Ceram - Silikaty. 2016;338–43.10.13168/cs.2016.0050Search in Google Scholar

[35] Powder Diffraction File 2, The International Centre for Diffraction Data. 2025.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Talero R, Trusilewicz L. Morphological differentiation and crystal growth form of Friedel’s salt originated from Pozzolan and Portland cement. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2012;51(38):120917084615009.10.1021/ie301671zSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Ma J, Li Z, Jiang Y, Yang X. Synthesis, characterization and formation mechanism of friedel’s salt (FS: 3CaO·Al2O3·CaCl2·10H2O) by the reaction of calcium chloride with sodium aluminate. J Wuhan Univ Technol-Mater Sci Ed. 2015;30(1):76–83.10.1007/s11595-015-1104-ySearch in Google Scholar

[38] Balonis M, Lothenbach B, Le Saout G, Glasser FP. Impact of chloride on the mineralogy of hydrated Portland cement systems. Cem Concr Res. 2010;40(7):1009–22.10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.03.002Search in Google Scholar

[39] Mesbah A, François M, Cau-dit-Coumes C, Frizon F, Filinchuk Y, Leroux F, et al. Crystal structure of Kuzel’s salt 3CaO·Al2O3·1/2CaSO4·1/2CaCl2·11H2O determined by synchrotron powder diffraction. Cem Concr Res. 2011;41(5):504–9.10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.01.015Search in Google Scholar

[40] Baquerizo LG, Matschei T, Scrivener KL, Saeidpour M, Wadsö L. Hydration states of AFm cement phases. Cem Concr Res. 2015;73:143–57.10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.02.011Search in Google Scholar

[41] Baquerizo LG, Matschei T, Scrivener KL, Saeidpour M, Thorell A, Wadsö L. Methods to determine hydration states of minerals and cement hydrates. Cem Concr Res. 2014;65:85–95.10.1016/j.cemconres.2014.07.009Search in Google Scholar

[42] Matschei T, Lothenbach B, Glasser FP. The AFm phase in Portland cement. Cem Concr Res. 2007;37(2):118–30.10.1016/j.cemconres.2006.10.010Search in Google Scholar

[43] Zhang T, Lu Z, Sun Z, Yang H, Yan Z, Ji Y. Modification of glass powder and its effect on the compressive strength of hardened alkali-activated slag-glass powder paste. J Build Eng. 2022;58:105030.10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105030Search in Google Scholar

[44] Sayers CM, Grenfell RL. Ultrasonic propagation through hydrating cements. Ultrasonics. 1993;31(3):147–53.10.1016/0041-624X(93)90001-GSearch in Google Scholar

[45] Sayers CM, Dahlin A. Propagation of ultrasound through hydrating cement pastes at early times. Adv Cem Based Mater. 1993;1(1):12–21.10.1016/1065-7355(93)90004-8Search in Google Scholar

[46] Voigt T, Grosse CU, Sun Z, Shah SP, Reinhardt HW. Comparison of ultrasonic wave transmission and reflection measurements with P- and S-waves on early age mortar and concrete. Mater Struct. 2005;38(8):729–38.10.1007/BF02479285Search in Google Scholar

[47] Yan-Rong Z, Xiang-Ming K, Zi-Chen L, Zhen-Bao L, Qing Z, Bi-Qin D, et al. Influence of triethanolamine on the hydration product of portlandite in cement paste and the mechanism. Cem Concr Res. 2016 Sep;87:64–76.10.1016/j.cemconres.2016.05.009Search in Google Scholar

[48] Yaphary YL, Yu Z, Lam RHW, Lau D. Effect of triethanolamine on cement hydration toward initial setting time. Constr Build Mater. 2017 Jun;141:94–103.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.02.072Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory